It is likely that many cuisines in all parts of the world originally depended on fermented fish and shellfish, cooked and cured meat, and seaweeds to add umami to a variety of dishes. In both Asia and Europe, preserved fish, together with the condiments made from them, have been used for at least two and a half millennia, and probably since long before then, as a simple, nutritious way to improve the taste of other foods. One might say that the history of using ingredients to prepare food that is rich in umami runs parallel to and reflects the overall evolution of the culinary arts. The heart of the matter is handling the ingredients in such a way that the proteins and nucleic acids are converted to free amino acids and free nucleotides by the skilful use of cooking, brewing, enzymatic fermentation, salting, drying, smoking, and curing, alone or in combination. In the past, these methods were also of great importance to prevent spoilage of the foodstuffs that come from the sea.

Before we come to fish and shellfish, let us start our exploration of marine sources of umami with the seaweed kelp, the raw ingredient that contains more free glutamate than any other, up to about three percent, and that was the key to Professor Ikeda’s identification of the fifth taste.

The spread of Buddhism from China and Korea to Japan in the sixth century brought with it a very specialized vegetarian cuisine, shōjin ryōri or ‘devotion cuisine,’ about which we will learn more later. It is thought that the idea of using kelp, the large brown alga known as konbu in Japan, to make and impart umami can be traced back to this religious movement.

With the spread in the 1300s of Zen Buddhism, whose monks practiced an even stricter, more ascetic form of vegetarianism that eschewed all animal products, konbu took on additional prominence. It was used to make shōjin dashi, the ultimate vegetarian soup stock described in the previous chapter, which is sometimes served with salted dried tofu. As tofu is rich in protein, this simple temple broth is both palatable and nutritious.

Harvesting konbu along the coast of Hokkaido in Japan.

The historical record concerning the commerce in seaweeds gives an indication of the way in which these culinary practices were evolving. Descriptions of the harvesting of wild kelp growing along the coasts of the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido can be found in sources going back to the eighth century. It would appear that the inhabitants of Hokkaido did not themselves have any tradition of using the seaweeds for making dashi, but the monks in the many temples in Kyoto had started to do so. By the fourteenth century, trading ships were carrying sun-dried seaweeds from Hokkaido to Osaka and Kyoto via a 1,200-kilometer, mostly maritime route known as the konbu road.

Given that konbu is the mother lode of umami in Japan, it is hardly surprising that there is an entire science, with deep historical roots, linked to the selection and handling of different types and qualities of the algae. More than 95 percent of all konbu harvested in Japan grows in the cold water along the northern coastlines around the island of Hokkaido. Here alone, more than forty varieties are collected.

Of the many available types, ma-konbu and Rishiri-konbu are considered to be the best choices for making dashi because the resulting stocks have a very light color and a complex taste. Ma-konbu is the konbu with the largest amount of free glutamate, 3,200 mg per 100 g, whereas Rausu-konbu has 2,200 mg per 100 g, and Rishiri-konbu has 2,000 mg per 100 g. The lower-quality Hidaka-konbu has 1,300 mg per 100 g. And, of course, if they have been aged for a few years, they are even more highly prized.

Two specialty products, tororo-konbu and oboro-konbu, are evidence of the serendipitous relationship between the city of Osaka and nearby Sakai, an important port on the konbu road. The former is well known for its use of konbu in its distinctive cuisine and Sakai has for centuries been famous for its exceptionally high-quality knives. Tororo-konbu is now generally prepared in factories. Dried konbu blades are first marinated for a short time in a rice vinegar mixture, allowed to dehydrate partially, compressed into bundles, and then cut across the fibers into paper-thin shavings by machines with razor-sharp knives. The shavings take on a matte white appearance, tinged with the palest green, and can be as thin as 0.01 mm, less than the diameter of an average human hair. Oboro-konbu is made by a similar, but exclusively artisanal, process. After the bundles of marinated seaweeds have been left for a day to become softer, skilled craftsmen scrape them by hand using a knife with a special blade, resulting in shavings that, amazingly, are only slightly thicker than those made by machine. Both types of shavings have a very unusual mouthfeel, not unlike the sensation one gets from eating cotton candy. They are among the softest foods on the planet, so light that they almost melt on the tongue, leaving an aftertaste of umami with a slightly acidic undertone from the rice vinegar. Tororo-konbu is often used to enhance the taste of a soup or a tofu dish, while oboro-konbu, being cut along the fibers of the seaweed, can be wrapped around cooked rice.

Like many culinary innovations, oboro-konbu and tororo-konbu may have been invented by chance. Although dried seaweeds can be preserved quite successfully, they are susceptible to mold if they accidentally become moist under transport or have not been dried sufficiently in the first place. It is thought that people came up with the idea of scraping off the resulting whitish layer and then marinating the seaweed in a little rice vinegar to enhance the taste, kill the mold, and preserve the konbu even longer.

Tororo-konbu (top) and oboro-konbu (bottom).

There are many different varieties of konbu, all belonging to the alga order Laminariales. By far the greatest proportion of the farmed konbu is made up of the species Saccharina japonica, which is related to the sugar kelp that is common along Atlantic coastlines. The blades of these seaweeds can grow to several meters in length and 10–30 centimeters in width. Most of the konbu sold on the world market is cultivated on ropes in the seas around China and Japan. After harvest, the algae are sun dried, and those of highest quality are put aside to undergo a carefully controlled process of aging in cellars (kuragakoi). While the algae can be cured for up to ten years, they are kept, on average, for two years. Curing the seaweeds, in a sense, ripens them so that they lose some of the flavor of the sea and develop a milder taste, allowing their inherent umami and subtler aromas to come to the forefront. In Japan, the best vintage konbu is the object of unabashed admiration, much in the way that wine connoisseurs appreciate the finest bottles from exceptional years.

Konbu contains large quantities of free amino acids, of which 80–90 percent is glutamic acid, but it lacks inosinate and guanylate, which interact synergistically with glutamate. The balance of the amino acid content is made up mostly of alanine and proline, which both impart a sweetish taste to the seaweed. Another substance that contributes to a rich umami taste is sometimes present in the form of a layer of whitish powder that is often exuded onto the surfaces of the blades when they are dried and cured. Under no circumstances should this be washed off, as it is made up of a combination of sea salt, glutamate, and mannitol. Mannitol, which is very abundant in sugar kelp, is what is known as a sugar alcohol and also has a sweetish taste.

Although the various types of konbu are the seaweeds with the most free glutamate, the red algae dulse (Palmaria palmata) and laver (Porphyra spp.) also contain reasonable quantities of glutamate. Laver, which is used to make nori, also has inosinate and guanylate, with the result that the nori itself is a source of both basal and synergistic umami in sushi.

A bundle of dried konbu.

What is special about konbu and quite a number of other seaweeds is that once they have been dehydrated, and sometimes also cured, the free glutamate is extracted very easily by soaking them in warm water, resulting in umami. Nevertheless, as a good dashi has only about 30 mg of glutamate per 100 g, this process draws out only a small proportion of the total available. With the exception of ripe tomatoes, konbu is probably the raw ingredient that yields the most glutamate with the least preparation.

Before we move on to the fermented fish products, we will have a quick look at some foods prepared from fresh fish. Fish and shellfish are unusually good sources both of basal umami derived from free glutamate and synergistic 5’-ribonucleotides. (See the tables at the back of the book.) At the top of the list of free glutamate, we find sardines, squid, scallops, sea urchins, oysters, and blue mussels. Shrimps and mackerel, which contain more glutamate than a variety of types of fish roe, are also near the top. Bony fish, especially those with darker meat, have significantly less free glutamate.

Anchovies, sardines, scallops, squid, mackerel, tuna, and shrimps are high on the list of foods with an abundance of nucleotides, and in particular, inosinate and adenylate. But as we will see later, there is a much lower concentration of the substances that impart umami in fresh fish than in their dried and fermented counterparts. Smoked fish normally also have a stronger umami taste than fresh fish.

Just because a fish or a shellfish is rich in umami substances, it does not follow that this will be the most prominent taste. For example, sea urchins contain the amino acid methionine, which has a bitter, characteristic sulfurous taste that is redolent of the sea. When that is taken away, sea urchins taste more like crab or shrimps. Another example is crab, which has a great deal of the amino acid arginine, which imparts a taste that is both bitter and salty like seawater.

Gentle cooking and steaming of fresh fish and shellfish produce umami by releasing their free glutamate and, more important, the nucleotides that interact synergistically with it.  Pearled spelt, beets, and lobster (page 70). This is why it is quite possible to make delicious soups using only these two ingredients. Even more umami can be achieved by adding vegetables and herbs to a simple shellfish bisque.

Pearled spelt, beets, and lobster (page 70). This is why it is quite possible to make delicious soups using only these two ingredients. Even more umami can be achieved by adding vegetables and herbs to a simple shellfish bisque.  Crab soup (page 76). A savory combination of fish, shellfish, vegetables, and seaweeds is to be found in the traditional clambake made on the beach and in a modified version prepared in a pot.

Crab soup (page 76). A savory combination of fish, shellfish, vegetables, and seaweeds is to be found in the traditional clambake made on the beach and in a modified version prepared in a pot.  Clambake in a pot (page 78). The traditional French bouillabaisse is a thick soup made with fresh fish, shellfish, and often vegetables and eggs. It is served with a dollop of rouille, a sauce that is thickened with an egg yolk. It is a felicitous combination of ingredients that are filled with umami substances.

Clambake in a pot (page 78). The traditional French bouillabaisse is a thick soup made with fresh fish, shellfish, and often vegetables and eggs. It is served with a dollop of rouille, a sauce that is thickened with an egg yolk. It is a felicitous combination of ingredients that are filled with umami substances.

Serves 4

2 live lobsters weighing about 300 g (⅔ lb) each

olive oil

assortment of coarsely chopped vegetables, such as leeks, carrots, celery, parsley stalks

tomato paste a little dry white wine 2–3 Tbsp butter

200 g (⅞ c) pearled spelt

8 small beets

1 shallot, finely chopped

pinch of cayenne pepper

3 dL (1¼ c) chicken bouillon

60 g (1⅔ oz) finely grated Parmesan

salt and freshly ground black pepper

fresh tarragon leaves

1. Pierce the lobsters through the head. Remove the heads and the claws. Split the tails into two pieces, leaving the shells on, and remove the innards.

2. Fry the claws and tail pieces in a pan in warm olive oil until a real shellfish aroma develops. The lobsters should only be browned—the meat should not be cooked through. Remove the meat from the claws and the tails.

3. Cut the heads into chunks, toast them in a skillet in a little warm olive oil together with the shells from the tails and claws. Add the assorted vegetables, tomato paste, and wine. Reduce the liquid.

4. Add water just to cover the shells, bring to a boil, and skim off the foam.

5. Add 2 or so tablespoonfuls of the butter, cover, and allow to simmer on low heat for about half an hour. Pass through a fine-mesh sieve and refrigerate.

6. The butter will solidify and rise to the surface. Remove a little of it and put in a pot. Reserve the rest of this lobster butter for sautéing the lobster meat. Keep the lobster bouillon for cooking the pearled spelt.

7. Rinse the spelt. Peel the beets very carefully, and if necessary, cut them into smaller pieces.

8. Warm the lobster butter in the pot, add the finely chopped shallot, and fry gently without allowing the shallot to brown. Add the drained spelt and cayenne. Add the chicken bouillon and lobster bouillon alternately, a little at a time. Place the beets in the spelt.

9. Cook the spelt, pricking the beets from time to time to test for done-ness. Remove the beets when they are soft but not overdone.

10. Allow the spelt to continue simmering. It is ready when it is still a little firm. Mix in the Parmesan cheese, season with salt and pepper, and return the beets to the pot. Add the tarragon.

11. To serve: Sauté the lobster meat in the remaining lobster butter in a skillet over medium heat just before serving. Arrange on plates with the spelt and beets. Drizzle with any lobster butter remaining in the sauté pan.

▶ Pearled spelt, beets, and lobster.

Ikijime, which means ‘to terminate while alive,’ is a 350-year-old Japanese technique for killing fish. It has the effect of delaying the onset of rigor mortis, thereby ensuring that the taste of the fish is of the highest quality and that there is least damage to, and discoloration of, the flesh. The fish dies humanely and unstressed, which preserves and releases more of the savory substances that bring out umami.

The traditional method is as follows. With a heavy knife, a cut is made in the head on the dorsal side of the live fish, slightly above and behind the eyes, severing the main artery and the elongated medulla, which is the lowest part of the brain stem. This is the part of the brain that controls movement. A second cut is made where the tail is attached to the body. Then the fish is plunged into an ice slurry in order to allow it to bleed out. The muscles of the fish relax in the ice-cold water while the heart continues to pump, but the fish has ceased to struggle for its life and is unstressed.

The final, definitive step is to shut down completely the autonomic nervous system, which continues to send messages to the muscles to contract. It is destroyed by inserting a long, very thin metal spike along the length of the fish through the neural canal of the spinal column. At this point, the fish relaxes totally and all movement ceases.

The blood that remains in the muscles retracts into the entrails of the fish, which are removed under running water so that blood and digestive fluids do not spill onto the flesh. The head, tail, gills, and fins are cut off and the fish is wrapped in paper or cloths to absorb any blood that might still seep out. At this point, the fish can be filleted for cooking, sliced for sashimi, or allowed to age for one or two days in the refrigerator.

Surprisingly, a really fresh fish is not always the one that tastes best. Allowing the fish to age generally brings out a greater range of taste impressions and more umami because taste substances are released into the muscles. At the same time, the ongoing enzymatic breakdown of the muscle fibers at low temperatures leads to a softer, more pleasing texture and a much better mouthfeel. In the case of flatfish, for example, this is partly due to the release of inosinate, which interacts synergistically with the glutamate content. Naturally, the determining factor is whether the fish has been killed by ikijime so that the fillet is perfect, with no traces of blood or digestive fluids. There should also be no signs of tissue damage caused by the trauma or rough handling that are characteristic of less skillful ways of slaughtering and bleeding out the fish. Fish that have been killed by ikijime and then allowed to age are known in Japanese by the term nojime.

At first sight it might appear that ikijime is a brutal technique, but there is no doubt that if it is carried out professionally it is a very humane way of killing a fish and causes it the least suffering. At the same time, it allows the fish to be used to the best advantage, with more taste and higher gastronomic value.

▶ Chef Toshio Suzuki demonstrates ikijime, the traditional Japanese technique for killing a fish, at the Gohan Society in New York.

What makes a traditional New England clambake so special? Of course, a festive occasion and the fresh sea air are part of the equation, but there is more to it. Clambake is a way of cooking fish, shellfish, and vegetables between layers of fresh seaweeds in a stone-lined hollow on the beach. This is a wonderful example of a recipe that has evolved into a simple way to maximize the intensity of the fifth taste. This is all due to the seaweeds. As they warm up, they release glutamate, which interacts synergistically with the ample quantities of nucleotides found in the fish and shellfish.

The appeal of trying to re-create a typical New England clambake using local Danish ingredients was not lost on a small group of our seafood-loving friends who joined us to do so. On a summer day in August, we headed for a quiet beach on the northern part of the island of Funen. Two days beforehand, some of us had slaved away to construct a stone oven in the sand. It consisted of an oval hollow, about 80 centimeters deep and 1 meter across at the widest part. The bottom and sides were lined with large stones, placed as close to each other as possible.

To start the process, a fire was lit in the hollow and for the next three hours we kept adding more wood to heat all the stones, both on the bottom and at the sides. In the meantime, we collected pieces of fresh bladder wrack, enough to fill the entire hollow. When the wood had almost burned completely and the stones were red-hot, we removed the largest of the embers and remaining bits of charred wood. The oven was now ready to be filled with all of the good things that we had on hand: mussels, lobsters, langoustines, a large catfish, pike-perch, ocean perch, mackerel, corn on the cob, and potatoes. As you might have noticed, the vegetables were chosen with an eye to their glutamate potential. The only thing missing was clams!

First we placed a thick layer of bladder wrack in the bottom and then added our ingredients in layers, with more seaweeds in between them. Those ingredients that needed the longest cooking time were placed at the bottom. A final layer of seaweeds was added to form a sort of flat lid, on which half a dozen fresh eggs were placed. They act like a thermometer to indicate when the clambake is ready to eat. More wet seaweeds were placed on the stones that formed the rim of the oven in order to prevent the canvas tarpaulin, which was placed on top to keep the steam in, from scorching or catching fire. Once everything was in place, what was required was patience. In the meantime we made a bisque from small live crabs that we found on the beach.  Crab soup (page 76). After about an hour and a half, we took one of the eggs out from under the canvas. It was not yet cooked through, which meant that the clambake was also not ready, and we had to resign ourselves to waiting a little longer. Half an hour later, we pulled out another egg. It was exactly the consistency of a soft-boiled egg, a sign that we could start to unpack the oven.

Crab soup (page 76). After about an hour and a half, we took one of the eggs out from under the canvas. It was not yet cooked through, which meant that the clambake was also not ready, and we had to resign ourselves to waiting a little longer. Half an hour later, we pulled out another egg. It was exactly the consistency of a soft-boiled egg, a sign that we could start to unpack the oven.

Once we had everything on the table and had poured glasses of dry white wine, we tucked in. The food tasted absolutely wonderful—it was as if the umami was rising out of it like a vapor. The clambake was a total success and turned out to be well worth both the effort and the long wait.

▶ Clambake at a Danish beach.

Serves 4

2 kg (4½ lb) small live crabs

100 g (3½ oz) celeriac

100 g (3½ oz) onion

100 g (3½ oz) leek tops

100 g (3½ oz) carrots

½ dL (⅕ c) olive oil

3 dL (1¼ c) dry white wine

1 dl (⅖ c) dry white vermouth, such as Noilly Prat

5 Tbsp tomato purée

2 bay leaves

1 sprig fresh thyme

1 head fresh dill

½ chile pepper, chopped

1 tsp light brown sugar

1 L (4¼ c) water

100 g (3½ oz) butter

salt and freshly ground black pepper

possibly a little Tabasco sauce

bread for making croutons

olive oil

1 large clove garlic, crushed

1. Sort the crabs carefully and discard dead ones, if any. Even one dead crab can spoil the soup. Cut the vegetables coarsely into cubes.

2. Lightly sauté the crabs in very hot oil in a pot with a thick bottom.

3. Add the vegetables and stir to coat with the oil, then add the wine and vermouth, together with the puréed tomato, bay leaves, thyme, dill, chile pepper, and brown sugar.

4. Cook until the liquid has reduced by two-thirds, then add the water and simmer for 30 minutes.

5. Strain off the bouillon, crush the crabs in the pot with a heavy spoon, and return the stock to the pot. Allow the soup to simmer for another 30 minutes, adding the butter halfway through.

6. Carefully skim off the butter and reserve to add color and taste to the soup at the end. Strain again to produce a clear bouillon to use as a base.

7. Season with salt, pepper, and possibly a little Tabasco sauce, and whisk in a little of the crab butter.

8. To make croutons, trim the crusts off the bread, cut into small cubes, and toast them in a pan with hot olive oil and the crushed garlic clove. Serve the soup garnished with the croutons.

THE FULL-BODIED VERSION

Mix together saltwater fish and langoustines cut into chunks, mussels, a little tomato paste, olive oil, parsley, garlic, finely chopped onion, and salt. Cook in the soup for 1–2 minutes, so that the fish is still a little raw in the middle. Served steaming hot and topped with bread, garlic mayonnaise, and a head of fresh dill, this makes a main course.

▶ Small crabs in the soup pot.

Clambake in a pot.

If you do not have access to a beach, or one with stones, or one where you are allowed to build a fire, you can still make a very successful clambake. You can cook juicy lobsters, clams, or a whole fish on a bed of seaweed in a huge pot on the top of the stove, where you can control the temperature. Here we give instructions for a version with lobsters.

First you need to gather fresh, living seaweeds, such as bladder wrack, from an area where you are sure that the water is clear and unpolluted. The seaweeds need to be rinsed thoroughly to remove any sand, small shells, or sand fleas that might be on them. Then place a layer that is 15–20 centimeters (6–8 inches) deep in the bottom of the pot. Place two live lobsters back to back on top of the seaweeds. Insert a thermometer attached to a cord in the middle between the lobsters and cover everything with another layer of seaweeds of the same size.

Cover the pot with a tight-fitting lid so that no steam can escape. Turn the stove element to the lowest possible heat setting and heat to a temperature of 65ºC (150ºF). This should take about an hour and a half. The lobsters are now cooked, already salted to perfection by the seaweeds. Serve with a small crisp salad, toasted bread, and a homemade mayonnaise to which a bit of Worcestershire sauce has been added. It is a meal fit for a king.

The liquid remaining in the pot can be reduced to make a sauce with strong tastes of lobster and umami. It can be used, for example, to nap the lobster meat or to season the mayonnaise.

Excavation of a Roman garum factory in Almuñécar, Spain.

Even though fresh fish and shellfish are good sources of umami, their effectiveness is greatly enhanced by drying or fermenting them. In fact, fermented fish contain more inosinate than any other foodstuff. From time immemorial, people in many parts of the world have been making them into sauces and pastes for use as taste enhancers. In Europe, the earliest known example is a traditional fish sauce that was greatly valued by the ancient Greeks and Romans as a universal condiment. It is indisputably the oldest additive used in the West to impart umami.

The Romans were very partial to this salty, fermented fish sauce, called garum, and later also liquamen, in Latin. It was used both as a salt seasoning and to add deliciousness—namely, what we know as umami. Classical Roman works on the culinary arts suggest that garum could be incorporated into just about any dish, even sweet soufflés. Probably, however, it was most often mixed with something else, for example, with wine vinegar (oxygarum), with honey (meligarum), with wine (oenogarum), or with spices.

The etymology of the word garum is a bit of a mystery. It is derived from a fish known to the ancient Greeks as garos; Pliny the Elder includes it in his list of the fish found in the oceans, but without any further description. The sauce was made on the Aegean islands at least as early as the fifth century BCE, and eventually its production spread to many of the fishing towns all around the Mediterranean. No sources describe exactly how it was made, only that it was made from fish and that it smelled horrible. While early writers sometimes characterize it as putrid, in other writings they express an enthusiastic fondness for the sauce, referring to its “very exquisite nature.”

It seems that the term garum applied only to the brownish liquid that seeped out when small fish and fish intestines, especially those from mackerel and tuna, were salted, crushed, and fermented. The most highly prized garum was made from the blood and salted innards of fresh mackerels, which were fermented for two months. It is said that the mackerels had to be so fresh that they were still breathing. A lower quality sauce, muria, was made from the briny liquid drawn out when tuna was preserved in salt.

Fermentation took place outside in the dry heat. The stench must have been awful, and that is probably why no ruins of garum factories have been found inside the walls of Pompeii. There were, in fact, regulations forbidding the erection of establishments for the production of garum within a distance of three stades (or a little more than half a kilometer) from a town. Nevertheless, garum production was so widespread and such a valuable source of income that the welfare of many coastal towns depended on it. The sauce acquired a status that put it on a par with olive oil and wine. It was stored in tall, slender pitchers or in jars, which can probably best be compared to contemporary bottles with ketchup or Worcestershire sauce. Garum may have been mixed with olive oil at the dinner table to make what we would now think of as a vinaigrette dressing.

Some of the Roman writers thought, erroneously, that garum is the liquid that is formed when fish rots, due to bacterial decomposition. Actually, it is the result of fermentation, in which salt and the enzymes of the fish itself cause it to break down. In this, the innards of the fish are very important, as the intestines contain large quantities of proteolytic enzymes, which work on the proteins in the fish. This process is accelerated by using salt, which draws out the liquid from the fish and, furthermore, inhibits the growth of bacteria.

The fermentation process undoubtedly released great quantities of free amino acids, among them glutamic acid. It involved some combination of the flesh, innards, and blood of fish, but other than that many of the details of how garum was made in antiquity have never been discovered. It seems that there were local variations as to which types of fish and what parts of them were used and in what proportions. The sauce could contain large amounts of fish, especially if it was made from small anchovies, which almost liquefy under fermentation. It is possible that garum was made with blood and liquamen with whole fish. Even though the paste-like dregs, called allec, that were left behind when the liquid was skimmed off were malodorous, the garum itself appears to have had a mild, pleasant taste.

The garum trade reached its peak from the second to the fourth centuries CE, but garum never lost its appeal in the Mediterranean region, where it was used throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. It has survived to this day in the form of salted anchovies and anchovy paste, both of which have a cleaner taste because the innards are removed from the fish before they are processed. The different varieties of fish sauces now made in Southeast Asia—for example, oyster sauce—all contain great quantities of glutamate and can be seen as counterparts to the Roman garum, just as Worcestershire sauce can be considered to be its modern Western offshoot.

The use of garum has been immortalized in the legendary work concerning the culinary arts, De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), the oldest book of recipes that has survived from European antiquity. It is popularly attributed to a Roman gourmet and lover of luxurious things, Marcus Gavius Apicius, who lived in the first century CE. As the text was probably compiled sometime around 400 CE, it is doubtful that the work is actually by a true historical figure. More than 80 percent of the approximately 500 recipes in the book incorporate garum, in many cases as a substitute for salt.  Patina de pisciculis (page 82)

Patina de pisciculis (page 82)

Even though we have documentary evidence that the ancient Greeks and Romans used garum as a fish sauce more than 2,500 years ago, we probably have to look to the cultures of the East, and especially to that of China, to find the origins of contemporary fish sauces. It was mostly the Chinese living in the coastal areas who made fish sauce, probably by combining small fish with the innards from larger cooking fish, causing fermentation. Once soybeans were added to the salted and fermented fish in order to stretch the ingredients further, the liquid started to evolve into what would later become soy sauce, which came to be used much more widely, particularly inland.

Fermented sauces and pastes made from fish, shellfish, and mollusks—possibly more than 300 different types, covering a broad spectrum of qualities and price levels—are common throughout most of Southeast Asia. They are known by a number of different names: yu-lu (China), nuoc mam tom cha (Vietnam), nam-pla (Thailand), teuk trei (Cambodia), nam-pa (Laos), patis (Philippines), bakasang (Indonesia), ngan-pya-ye (Myanmar), budu (Malaysia), and ishiri (Japan). Almost all fish sauces are made according to the same basic method. It involves the salting and fermenting of either whole fish and shellfish or parts thereof, including blood and innards. Fermentation takes place using the enzymes found in the animal products, releasing an abundance of free amino acids, especially alanine and glutamate. Some are made with fresh fish, others with ones that have been dried first; anchovies are included in most of the sauces. As an example, ishiri is made from fermented sardines, other small fish, and the innards from squid. When the sauces are fermented for a long period of time, they exhibit tastes similar to those of nuts and cheese. Modern Thai fish sauce is fermented for up to 18 months, much longer than the Roman garum of antiquity, and it also has a considerably higher salt content. Fish sauces have come to be associated with some very traditional dishes. In Korea, shiokara, made from fermented salted fish, is added to that country’s best known dish, kimchi, which is fermented cabbage sometimes mixed with other vegetables. Similarly, in Japan, ika no shiokara consists of small squid fermented using the enzymes from their own innards.

This recipe for a fish dish is based on the ancient Roman one by Apicius. The original version does not specify which type of fish was used. Here we have chosen small sprats, but you could also use small pieces of salmon, or small herring, sardines, or anchovies. It is actually unlikely that herring or salmon would have been available in Rome. Also, the original recipe called for twice as much oil as this version.

Serves 4

400 g (a little less than 1 lb) small fresh sprats (about 20 fish)

salt

½ tsp freshly ground black pepper

all-purpose flour, for dredging

1 dl (⅖ c) olive oil

2 onions, chopped

150 g (5¼ oz) raisins

2 sprigs fresh lovage

1 Tbsp fresh oregano leaves

½ dL (⅕ c) garum or fish sauce

1. Season the fish with the salt and the pepper and coat with the flour.

2. Panfry the fish in the oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Remove and keep them warm.

3. Add the onions to the oil and cook until they are translucent.

4. Add the raisins, lovage, oregano, and garum or fish sauce to the onions and season to taste.

5. Pour the oil mixture over the warm fish just before serving.

▶ Patina de pisciculis. Classical Roman fish dish with garum, based on the ancient culinary work On the Subject of Cooking. On the table are flasks with garum, olive oil, and wine, a feature of every meal in ancient Rome.

The most important contributor to umami in fish sauces is glutamate. The content of free glutamate can be very great, close to 1,400 mg per 100 g in Japanese ishiri and the Vietnamese nuoc mam tom cha, or a little more than in soy sauce. Usually, the salt content is also very high, all the way up to 25 percent, which is quite a bit more than the 14–18 percent found in soy sauce. The combination of umami and salt works synergistically to enhance the saltiness of fish sauce.

Commercially produced Asian fish sauce.

Interestingly, in contrast to such other taste additives as anchovy paste and certain original Asian fish extracts, fish sauce has no significant content of free 5’-ribonucleotides. In ancient Japan, a concentrated fish extract, irori or katsuo-irori, was produced by reducing to a paste the liquid in which bonito (katsuo) had been cooked, using the same techniques as those now used to make katsuobushi. Katsuobushi is the component of classical Japanese dashi that contributes the 5’-ribonucleotides that interact synergistically with the glutamate from konbu to impart a strong umami taste. As katsuobushi dates back only to the 1600s, it is a much newer arrival on the culinary scene than irori.

Although irori disappeared from Japanese cuisine during the Meiji era (1867–1912) and is no longer on the market, a similar product, senji, is still made on the island of Kyushu in the southern part of Japan. When produced according to the traditional recipe, senji contains 900 mg of glutamate per 100 g and no less than 786 mg of inosinate per 100 g. Comparably high levels of inosinate are found in another traditional fish extract, rikakuru, from the Maldives. Both of these sauces are much richer in inosinate than katsuobushi, which has only about 474 mg per 100 g.

In Asia, fish sauces are generally incorporated into cooked dishes or served as a condiment with, for example, rice. They are much more widely used as salt substitutes and taste enhancers than as true sauces to be poured over food when it is served. The fish sauces can be seasoned with other ingredients, such as chile and lime juice.

The quality, and with it the content of substances that impart umami, of all of these fish sauces and pastes is very dependent on the raw ingredients that go into them and the method of production. Many of the commercially available products contain a great deal of salt and added MSG, and they do not live up to the high standard that is the hallmark of traditionally made fish sauces.

Cooking fresh mackerel in salt for production of quick-and-easy garum.

There are a number of recipes for the classical Roman fish sauce garum. They are quite simple and can easily be made with raw ingredients that are widely available, but an authentic garum needs to ferment for several months in heat and sun, which can be a problem in some climates. Let us not even begin to talk about the stench! Mackerels are a good choice, because these fish contain very aggressive enzymes in their innards, leading to powerful fermentation and the production of a great deal of glutamate. Garum can also be made from just the fish entrails. Experiments using just mackerel innards have resulted in a sauce with 623 mg glutanate per 100 g.  Garum (page 86)

Garum (page 86)

As you can see, making a true garum is a slow process. But there is a shortcut, which survived from a Greek source about agriculture (Geoponica) compiled in the tenth century CE from even older works. In it we find a recipe for a sort of quick-and-easy garum for the benefit of “the busy Roman housewife.” This recipe calls for cooking salted fish and innards for about two hours. As it is made without any fermentation, it is milder than traditional garum and imparts much less umami.

2 kg (4½ lb) very fresh mackerels

400 g (1¾ c) salt

Cut the whole mackerels, innards and all, into smaller pieces and place them in a crock. Mix in the salt. Cover the crock with a loose-fitting lid and place it outside where it is warm, preferably in the sun. Allow the fish to ferment for a couple of months, turning the fish pieces in the salt once in a while. Then strain out the liquid, first in a sieve or colander to remove the large pieces and then through cheesecloth to ensure that the liquid is completely clear. Store the finished sauce in the refrigerator in a bottle with a stopper. If you wish, you can dilute it with a little leftover wine. For this recipe, you can also use just the entrails and blood from mackerels.

On account of the significant salt content, which is about 20 percent, both the fermented garum and the quick-and-easy garum can, in principle, be kept indefinitely in a closed container in the refrigerator.  Quick-and-easy garum

Quick-and-easy garum

If you want to make a quick-and-easy garum with more umami, you can add water from cooking potatoes, tomato juice, and smoked fish or fish skin. This boosts the glutamate content to 217 mg per 100 g.  Smoked quick-and-easy garum

Smoked quick-and-easy garum

2 kg (4½ lb) very fresh mackerels

1 L (4¼ c) water

400 g (1¾ c) salt

sprigs fresh oregano

Cut the whole mackerels, innards and all, into smaller pieces and put them in a pot together with the water, salt, and some oregano. Bring the water to a boil, turn the heat to low, and allow the fish to simmer for about 2 hours. Then strain out the liquid, first in a sieve or colander to remove the large pieces and then through cheesecloth to ensure that the liquid is completely clear. Store the finished sauce in the refrigerator in a bottle with a stopper.

Quick-and-easy garum.

4 large onions, unpeeled

2 kg (4½ lb) very fresh whole mackerels, cut in chunks with their entrails

1 piece skin from smoked mackerel or salmon

2 L (8½ c) water used to cook mature potatoes

1 L (4¼ c) juice from the pulp of tomatoes

½ L (ca. 2 c) fresh oregano leaves

300 g (1⅓ c) sea salt

1. Cut the onions in half. Scorch them in a hot pot over high heat without any fat or oil until the cut side is completely black.

2. Add the mackerel, fish skin, water, tomato juice, oregano, and salt, and simmer on low heat for about 2 hours.

3. Strain through a fine-mesh sieve or cheesecloth. Return the liquid to a (clean) pot and cook to reduce the volume to 1 L (4¼ c).

4. Pour the garum into a bottle with a stopper. Store it in the refrigerator.

Fermented shellfish sauces and pastes are made all over Southeast Asia, often from shrimps and oysters. Shrimp sauce and paste are used in the preparation of most meals, especially fish and vegetable dishes, in such countries as Thailand, Myanmar, China, and the Philippines. Both are made from tiny shrimps that are washed, mixed with salt, crushed, and then dried in the sun. After a while, the fermentation process converts the shrimps first to a runny liquid and then into a thicker dark purple or brownish paste with a pungent smell. In Myanmar, this is called ngapi. Because it needs no refrigeration, it is often sold in the shops or markets in solid blocks. Ngapi is a fantastic source of umami, as it has 1,647 mg free glutamate per 100 g.

Oyster sauce deserves a special mention, even though the most commonly available commercial products have a poor reputation because they are oversalted and full of added MSG. A true oyster sauce is made by a slow reduction of water in which oysters have been cooked. The result is a thick, caramelized brownish liquid, to which no salt is added, and consequently there is no fermentation. Nevertheless, oyster sauce has large quantities of free glutamate, typically 900 mg per 100 g, which is due to the large glutamate content of the fresh oysters themselves.

Sadly, many commercial oyster sauces are made with oyster essence in water, thickened with cornstarch. Caramel coloring, salt, and MSG are then added. A special variety for vegetarians is made with mushrooms instead of oysters.

It will probably come as a surprise to most sushi lovers that originally sushi was not made with fresh raw fish, but with fish that had been fermented for up to half a year. This was partly out of the necessity, in earlier times, to be able to preserve fish in such a way that it could be stored and transported. In all likelihood, sushi originated in several places in Southeast Asia, but the first known mention of it is in a Chinese dictionary dating from the third century BCE. It is thought that it was introduced to Japan about a millennium later.

This early form of sushi was made by cleaning and salting fresh fish, which were then placed in layers in barrels interspersed with layers of cooked rice. A stone was placed on top of the lid of the barrel to press it down. The fish started to ferment due to their own enzymes and the lactic acid bacteria that thrive in the salty, starchy cooked rice. After a few months, the rice was no longer edible, but the fish had kept their nutritional value, even though their taste was much different from that of fresh fish. This type of sushi is called nare-zushi, meaning sushi that has been cured. Over time, the Japanese refined the technique. One of the innovations, around the beginning of the seventeenth century, was to add rice vinegar, which tenderized the fish and allowed the fermentation period to be shortened.

Modern sushi, known as nama-zushi, which means ‘raw sushi,’ is really only symbolically related to its original precursor. The fish is now very fresh and usually raw, and the rice is seasoned with a marinade made from rice vinegar, sugar, and salt in order to take on the traditional taste. Nama-zushi has much less umami taste than nare-zushi, as it is due solely to the free glutamate and 5’-ribonucleotides found in the raw fish and shellfish that are placed on top of the freshly cooked rice. Sometimes the chef might impart umami to the rice by adding a piece of konbu or some katsuobushi to the cooking water. In addition, many types of sushi are prepared with nori, which contains a great deal of glutamate as well as 5’-ribonucleotides. Finally, the pieces of sushi are often dipped in soy sauce, which is really just umami in concentrated form.

▶ Gunkan-maki with nori and salmon roe.

The combination of katsuobushi and konbu are intimately associated with the concept of umami. Katsuobushi is rich in inosinate, about 474 mg per 100 g, which interacts synergistically with the glutamate in konbu. It is produced from bonito, called katsuo in Japanese, a fish related to mackerel and tuna. Bonito is preserved using no less than five different methods: it is cooked, dried, salted, smoked, and fermented. The great quantities of 5’-ribonucleotides contained in it are the result of this laborious and meticulous treatment. On the other hand, katsuobushi has only a little glutamate, about 23 mg per 100 g.

FUSHI: FISH PRESERVED FIVE DIFFERENT WAYS

Fushi is a term that denotes fish that are preserved as described for katsuobushi. What the different types of fish used to make fushi—for example, bonito (katsuobushi) and tuna (maguro-bushi)—have in common is that they must not be too fatty, because this makes it harder to dry the fish and it can end up with a less delicate taste. Mackerel, for example, which is very oily, is less well suited for making fushi. On the other hand, fushi made from tuna has a very mild taste and, when combined with high-quality konbu (e.g., Rishiri-konbu), yields the finest dashi.

A forerunner of katsuobushi was bonito that has only been dried, and in the eighth century CE this expression simply meant ‘solid dried fish.’ In 1675, Youchi Tosa figured out how to improve the taste by smoking the fish and allowing a mold to grow on it. Today, katsuobushi is manufactured in several coastal towns in Japan, including Yaizu, Tosa, and Makurazaki. In the latter, there are seventy small family businesses that make it from freshly caught bonito. A characteristic smell of smoke and fish hangs over the entire city.

There are two main types of katsuobushi. One, arabushi, is not fermented and has the milder taste, and the other, karebushi, is fermented and much harder. There are also two types of karebushi. One type still has its red bloodline on the side of the fillet, and on the other the bloodline is cut off (chinuki katsuobushi). The one without the red part has a milder, less bitter, and more delicate taste.

Two types of katsuobushi in different forms: whole arabushi fillet and arabushi powder shown together with Hon-dashi powder (top) and whole karebushi fillet and karebushi shavings (bottom).

In order to make the best tasting katsuobushi with a high inosinate content, it is important not to stress the fish. Otherwise, all the ATP (adenosine-5’-triphosphate) in its muscles are depleted by trashing around in a net.

In earlier times, katsuo were caught near the Japanese coast by fishers in small boats using poles and lines with a hook. It was a very gentle way, and it tired the fish as little as possible. Now the fish are caught on a large scale with the help of a particularly careful technique. A circular net is spread around and under a school of katsuo, the fish are brought on board, and they are immediately deep frozen in saltwater.

Niboshi: small cooked sun-dried fish.

Niboshi are another source of the 5’-ribonucleotides (in particular, inosinate) that enhance umami. This product is made from small fish, such as anchovies and sardines, or the young of larger fish, such as flying fish, some species of mackerel, and dorade. In contrast to bonito, these types of small fish are often quite oily, which results in a stronger fish taste than that in katsuobushi. Although they can be used to make dashi, the result is less delicate, but quite adequate for daily use or in a miso soup.

To make niboshi, the fish are first cooked for a short time in a mixture of salted water and seawater. In some cases the fish are also smoked or grilled and air dried (yakiboshi), which results in a stronger taste. The fish are then dried. Traditionally, this was done outdoors in the sun, but now industrial methods are employed. Apart from concentrating the taste of the fish and releasing amino acids and inosinate, this processing technique ensures that niboshi have a long shelf life, as long as they are kept dry or frozen.

The hunt for the hardest foodstuff in the world, katsuobushi, took me, Ole, on a trip to Yaizu, a coastal town in Shizoka Prefecture in Japan, only about an hour from Tokyo on the wonderful Japanese bullet train, Shinkansen. Yaizu calls itself “Japan’s fishing city,” and this is where I would see how katsuobushi is made. My guide was Dr. Kumiko Ninomiya, one of Japan’s most prominent umami researchers, and we were joined by Mio Kuriwaki and Dr. Ana San Gabriel from the Umami Information Center in Tokyo. Ana San Gabriel is also a well-known umami researcher. Among her discoveries are umami receptors in animal stomachs; more recently, she has been studying umami taste in breast milk substitutes.

Dr. Ninomiya is the director of the Umami Information Center. She has contacts among those people in Yaizu who can make it possible for a foreigner like myself to gain admission to the harbor area and to a factory, Yanagiya Honten, where katsuobushi is made. Tooru Tomimatsu, president of the organization Katsuo Gijutsu Kenkyujo, showed us around.

We were lucky to arrive on a day when the frozen raw ingredients, katsuo (bonito), were being unloaded from the large fishing vessels, which had been at sea for a month. They had sailed as far as the southern Pacific Ocean and the seas around Micronesia in order to catch this highly desirable fish.

The rock-hard fish, which are frozen to -30ºC, each weigh 1.8–4.5 kilograms. They are sorted right on the quay, at first automatically and then by an army of workers who take over and sort them again carefully by hand. The fish are then transported to the factory for processing.

Step one is to defrost the fish in water that is aerated with air bubbles. The temperature must not rise above 4.4ºC in order to prevent the important taste substance inosinate from breaking down. Inosinate is absolutely central to the umami taste of the finished katsuobushi. Once they have thawed, the heads of the fish are cut off and the entrails removed mechanically. These castoffs are ground into a mush and used to make fish sauce. The fish is now simmered at 98ºC for almost two hours in brine that is used over and over. This brine accumulates many of the substances that impart the desired taste to the finished product. As the fish simmer, their proteins are denatured, the flesh becomes firmer, and the amount of free inosinate increases approximately thirtyfold. The cooked fish are cut up into fillets, trimmed, deboned, and skinned by hand.

Now comes the most important part of the process: namely, dehydrating the fish and reducing the water content from 65 percent to 20 percent, first by drying and smoking and then, in some cases, by fermentation.

The real secret lies in how the fillets are smoked. Here our timing was also lucky. Just as we arrived at the area where the four-story-high smoking ovens are located, the ‘smokemaster’ was ready to start fires in the special places called hidoku that lie at the bottom of each oven. We eased ourselves through the little trapdoor in the floor and climbed down a steep ladder just in time to see him light the fires in an array of large circular smoke basins where the firewood had been piled up. By crouching down on the floor of the oven, we were able to escape the worst of the smoke and for a brief moment experience the tension in the air as the wood burst into flames and the process began. Then it was a question of scrambling quickly up the ladder and out of the oven before the large trapdoor shut.

Unloading frozen bonito (katsuo) for katsuobushi production.

Only two types of hard oak wood (konara and kunugi, a type of chestnut oak) are used, as they impart the exact smoky taste that the Japanese prefer in their katsuobushi. The firewood is replenished and the fires relit up to four times a day. The company guards its trade secrets very well, and the inside of the oven was the only place where I was not allowed to take photographs.

The fish are arranged on wire trays stacked in the bottom of the smoke oven to dry out for about a day, reducing their water content to 40 percent. Then the trays are moved up to the topmost stories of the oven and smoked for ten days, thus reducing their water content even further, to 20 percent. The finished fillets are arabushi, one of the several varieties of katsuobushi. This is the product that is referred to as the hardest foodstuff in the world. A piece of arabushi is as hard as a wooden chair leg, and one has to wonder to what use it can be put.

Arabushi is normally ground to a powder and much of it is used in the production of Hon-dashi, which is made by Ajinomoto. Hon-dashi is an important ingredient in many Japanese soup powders, prepared foods, and a variety of taste additives.

Arabushi can undergo yet more processing and be dehydrated further by fermenting it, resulting in a stronger taste. This is a time-consuming process and consequently the product, called karebushi, is more expensive and more sought after. There are actually two types of karebushi. One type uses the whole fillet and has a more bitter taste. The other type has a milder, more refined taste because the dark red bloodline of the fillet, which lies against the lateral side of the fish, is cut away.

Katsuobushi for sale at a Japanese market.

Unfortunately, we were not able to see how karebushi is made in the course of our visit to Yaizu. This is a description of the process. First the tarcovered outer layer of the arabushi is planed or scraped off and the fillets are sprayed with a mold culture (Aspergillus glaucus) at a temperature of 28ºC. In the course of the following weeks, the mold spores sprout on the fillet and the fungal mycelia bore into the fillet. Once it is covered with mold, the fillet is brought out into the sun to dry, and all the mold is scraped off. This alternation between taking the fillet into the mold chamber and bringing it outside to dry in the sun continues for one to two months. The quality of the fish is thought to improve with each successive cycle.

The longer and more meticulous process used to make karebushi leads to a dried product that has fewer cracks. As a result, it is possible to make shavings that stay together instead of crumbling. When it is to be used, the hard fillet is placed on top of special box, which is like an inverted plane, so that ultrathin shavings can be cut from it. The karebushi yields the best taste when it is freshly shaved. Because they are so thin, it is technically possible to get 98 percent of the taste substance inosinate to seep out into a dashi. One can buy ready-cut shavings in airtight packages containing nitrogen to prevent the shavings from oxidizing. The shavings come in several varieties, according to the thickness of the shavings. Naturally, the thinner the shavings, the more quickly one can extract umami to make dashi.

Katsuobushi flakes are also sprinkled on soups, vegetables, and rice. When the dried flakes encounter the steam from the hot food, they contract and move as if dancing. That is why the Japanese call them ‘dancing’ fish flakes.

How does katsuobushi taste? First and foremost, there is a mild smoky taste, then a little saltiness, and then umami. Apart from inosinate, katsuobushi has at least forty other substances that contribute to its complex and distinctive taste, which combines saltiness, bitterness, and umami. Bitterness from an amino acid, histidine, is particularly prominent. The umami taste really comes to the forefront when katsuobushi is combined with other ingredients that contain glutamate, such as konbu.

▶ Katsuobushi production in Japan. Here the fillets are simmering in a special kettle.

In Japanese, kusaya means ‘rotten fish’ or something that smells bad. Much like the Swedish surströmming and the Scandinavian lutefisk, however, kusaya is better than its name would have us believe. Even though it is truly malodorous, its taste is often mild. It is made from horse mackerel or flying fish, which are cleaned, deboned, and placed in brine. The brine is often reused time and again, and it is said that some families jealously guard their special brine for generations. The fish is kept in the solution for up to twenty-four hours, after which it is placed in the sun to ferment for several days to bring out its inherent umami. It should be possible to keep properly preserved kusaya for years.

Kusaya: small pieces of fermented, salted horse mackerel.

Curing fish, such as herring, the old-fashioned way takes a long time. Whole, scaled herring, with their innards, are placed in layers of salt and cured in barrels that are kept for at least a month at 5ºC. The enzymes from the stomachs and entrails of the fish help to break down the muscles and to release a reasonable amount of glutamate. This is why cured herring made by the traditional method have much more umami taste than those produced industrially. The factories employ a very rapid process in which the fish are placed for a couple of days in a strong vinegar solution, which tenderizes them by bursting their cells but releases only a little glutamate.

Just as in Asia, classical Nordic cuisines have their own varieties of fermented fish, which contribute umami to their diet. Particular examples are Swedish surströmming, Norwegian rakfisk, and Icelandic hákarl. All are notorious for giving off especially offensive odors, but many think them an essential, delicious feature of their national food culture.

Of these, surströmming is probably the one that should be considered the Nordic equivalent to nare-zushi and kusaya. It is made with small Baltic herring, which are caught in the spring, lightly salted, and placed in barrels to ferment for up to two months. They are then canned, but an anaerobic fermentation process continues due to the presence of lactic acid bacteria, which do not need oxygen. After a while, however, the carbon dioxide that is given off by the fermentation process causes the tins to bulge so that it looks as if they might explode. Although only a little salt is used, the fish do not rot because the fermentation is so robust. In addition, a series of sour substances, after which the dish is named, and free amino acids are formed.

Surströmming: fermented Baltic herring, a Swedish specialty.

Hákarl is an Icelandic specialty made from fermented shark.

Rakfisk, the Norwegian counterpart of surströmming, has been a national tradition for at least 700 years and possibly much longer. It is made from trout, whitefish, char, or, occasionally, perch that are caught in the early autumn. The entrails, blood, and gills are removed, and the fish are lightly salted and then placed in a vinegar solution for about half an hour. They are then placed in a barrel, with the open stomach turned upward and salted. A little sugar and some brine are added. The barrel is covered and the lid is weighed down lightly. The enzymes from the fish itself convert the proteins to free amino acids. Then lactic acid bacteria take over and a slow fermentation process proceeds at low temperatures, 4–8ºC, in the course of the next three months. Rakfisk is usually served on flatbread or with potatoes and onions.

The original Nordic form of gravlax, which was fermented, is related to rakfisk and surströmming. In the Middle Ages, the fish was covered in flour and wrapped in birch bark, then buried and allowed to ferment. Modern gravlax now consists simply of fresh fish that is marinated for a few days in a mixture of sugar, salt, and spices. For this reason, there is not much change in the umami content of the fish.

The most infamous of the Nordic fermented fish is the Icelandic hákarl, made from either basking or Greenland sharks. Because it contains a great deal of trimethylamine oxide and also high levels of uric acid, the meat from these shark species can be consumed only after it is treated. In Iceland, the traditional method is based on fermentation. The fish is cleaned, the entrails removed, and the head discarded. It is then buried in a hole filled with gravel and covered with sand and more gravel. Heavy stones are put on top to weigh down the fish, so that the liquid seeps out.

The fish undergoes a fermentation process, in the course of which trimethylamine oxide, which has no smell, is converted to trimethylamine, which stinks horribly. At the same time, great quantities of ammonia, which has a pungent smell, are formed. After eight to twelve weeks, the shark is dug up and cut into strips that are air dried for two to four months. Before being served, the outer crust of the dried strips is removed and the cured fish is cut into cubes. Hákarl has a cheese-like, spongy consistency and a very strong smell of ammonia.

DRIED TUNA

Fillets of salted air-dried tuna are quite similar to botargo. Called mojama, they are of Phoenician origin and are now very popular in the tapas bars of Madrid.

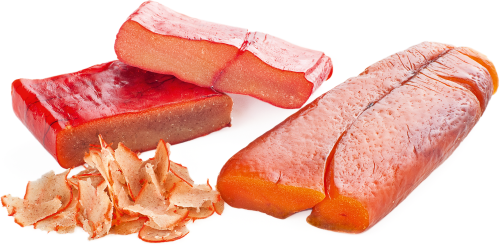

Botargo: salted and dried roe from hake, ling, and gray mullet, a Mediterranean specialty.

Roe contains a reasonable amount of glutamate, but how much it has does not always affect how strongly it tastes of umami. As evidence, we can cite the case of Russian caviar and salted salmon roe, which have 80 mg per 100 g and 20 mg per 100 g, respectively, of free glutamate. In theory, the caviar should have a much more pronounced umami taste than the salmon roe. But it is actually the reverse, because salmon roe also has inosinate, which is absent in caviar. The answer lies in the synergistic interaction between the inosinate and the glutamate.

BOTARGO IN THE DIARIES OF SAMUEL PEPYS, 1661

Botargo is mentioned in the diaries of the famous British author Samuel Pepys, written in London in the 1660s. On a very hot summer evening—June 5, 1661, to be precise—Samuel Pepys sat out in his garden with a friend, talking and singing, while drinking much wine and eating botargo. The salted roe had made him thirsty, and Pepys notes that when he finally went to bed at midnight, he was “very near fuddled.”

In Mediterranean cuisine, dried fish roe is a great delicacy, lending umami to such diverse dishes as tapas and pasta. The roe goes by a number of names: botargo in Spain, bottarga in Italy, butàriga in Sardinia, and avgotaraho in Greece. Roe sacs are extracted whole from tuna, swordfish, gray mullet, or a variety of fish from the cod family. They are put in sea salt for a few weeks and then hung up to air dry for about a month. The salt draws the liquid out of the roe, making it very firm and hard. A layer of beeswax, which is peeled off before eating, can protect the surface. Sometimes referred to as poor man’s caviar, the dried roe is highly prized in Sicily and Sardinia and frequently served in Spanish tapas bars, where it is eaten with a little lemon juice. In Italy, bottarga is often cut into thin slices and used as a pasta topping, to add salt and umami.

▶ Rakfisk: Norwegian specialty made with salted fermented trout.

The most famous book of all time concerning the art of catching fish is The Compleat Angler, written by the Englishman Izaak Walton (1593–1683). First published in 1653, it is written in the form of a dialogue between an avid angler and his traveling companions, a hunter and a fowler. Their conversation spans a journey of five days and gives a detailed account of how to catch and cook a variety of fish.

The pike fisher. Illustration in The Compleat Angler, Izaak Walton, 1653.

On the fourth day, the angler describes the pike, called by some “the Tyrant of the Rivers,” and gives instructions on how to catch one using a frog as bait. He also reveals a secret recipe for roasting the fish, one that is loaded with umami from both the oysters and the anchovies that are stuffed into the body cavity. The former contains up to 1,200 mg free glutamate per 100 g, and the latter contains inosinate and melt right into the roasting fish. Walton’s classic recipe is as follows:

First, open your Pike at the gills, and if need be, cut also a little slit towards the belly. Out of these, take his guts; and keep his liver, which you are to shred very small, with thyme, sweet marjoram, and a little winter savory; to these put some pickled oysters, and some anchovies, two or three; both these last whole, for the anchovies will melt, and the oysters should not; to these, you must add also a pound of sweet butter, which you are to mix with the herbs that are shred, and let them all be well salted. If the Pike be more than a yard long, then you may put into these herbs more than a pound, or if he be less, then less butter will suffice: These, being thus mixt, with a blade or two of mace, must be put into the Pike’s belly; and then his belly so sewed up as to keep all the butter in his belly if it be possible; if not, then as much of it as you possibly can. But take not off the scales. Then you are to thrust the spit through his mouth, out at his tail. And then take four or five or six split sticks, or very thin laths, and a convenient quantity of tape or filleting; these laths are to be tied round about the Pike’s body, from his head to his tail, and the tape tied somewhat thick, to prevent his breaking or falling off from the spit. Let him be roasted very leisurely; and often basted with claret wine, and anchovies, and butter, mixt together; and also with what moisture falls from him into the pan. When you have roasted him sufficiently, you are to hold under him, when you unwind or cut the tape that ties him, such a dish as you purpose to eat him out of; and let him fall into it with the sauce that is roasted in his belly; and by this means the Pike will be kept unbroken and complete. Then, to the sauce which was within, and also that sauce in the pan, you are to add a fit quantity of the best butter, and to squeeze the juice of three or four oranges. Lastly, you may either put it into the Pike, with the oysters, two cloves of garlick, and take it whole out, when the Pike is cut off the spit; or, to give the sauce a haut goût, let the dish into which you let the Pike fall be rubbed with it: The using or not using of this garlick is left to your discretion.

Walton concludes his tale by cautioning that “this dish of meat is too good for any but Anglers or very honest men; and I trust you will prove both, and therefore I have trusted you with this secret.”

Klavs and Ole are both members of a rather peculiar little club, The Funen Society of Serious Fisheaters, who are all very familiar with The Compleat Angler and, of course, the story about the pike and how to cook it. Together with the other members, we set out to re-create the experience exactly as Walton describes it. We had been biding our time, anxiously, for more than a year, hoping that a pike of the appropriate size would eventually turn up in the cooler of our favorite fish dealer in Kerteminde, a nearby fishing town. One of the members, who is an enthusiastic sports fisher and a decorator, had been practicing how to tie together willow branches to make a sort of cage to hold the pike together as it was being roasted. In 2009, as we neared the beginning of the pike fishing season in May, when the fish is at its best, we hoped that luck might be with us. It was, and we soon received word that a pike that was absolutely ideal had been caught in a Swedish lake.

Right after the fish arrived in Kerteminde, on the afternoon before the roast, our willow cage maker hurried to the fish dealer’s cooler to measure the fish. It was 120 centimeters long and weighed about 7 kilograms, a little bigger than the one yard recommended by Walton. He then set to work to prepare a cage that would fit the fish precisely. The willow twigs needed to be very green and thoroughly soaked in water so that they would not burn on the grill. The cage was tied together with wires and left open at both ends, which were closed up only after the pike was in place.

The next day, seven members of the club gathered at Klavs’ restaurant, The Cattle Market, on the day of the feast. The pike was hung from the ceiling, cut open at the gills, and the entrails removed. Walton’s recipe was followed to the letter. Fifty fresh oysters were stuffed into the cavity, together with a pound of butter, winter savory, and salted anchovies. Once it was completely full, a wooden skewer was poked through the fish to hold it together, and it was tied at the gills to prevent the stuffing from falling out. The “Tyrant of the Rivers” was placed ceremoniously in the willow cage and the ends were wired shut.

While this was going on, a charcoal fire was lit in the outdoor grill and, when it was ready, the fish was placed on it. The willow twigs and the fish were brushed with red wine to keep them moist. Walton specified that this should be claret, a red Bordeaux wine, which originally was a light rosé-like wine very popular in England in the 1600s.

After a little under an hour had elapsed, the pike was ready. The skin was still intact and none of the stuffing had escaped. The cage was cut apart and the fisheaters let the pike fall into a large platter, again as prescribed by Walton. The long-awaited moment arrived—the skin was peeled away and the pike cut into pieces. The flesh was almost translucent and easily slipped off the bones. We wondered how the stuffing would taste. There was no need to worry—it was wonderful. No liquid seeped out when the fish was cut up, as the butter had been absorbed right into the flesh and the oysters were cooked to perfection. The fish had a fantastic taste, with just the right degree of saltiness and so much umami that it seemed to fill the mouth completely. And, to our delight, the anchovies and the winter savory had drowned out some of the muddy taste that can be common in pike.

We ate every last morsel.

▶ An authentic pike roast, in accordance with Izaak Walton’s recipe.

I often think of my Alsatian grandmother.… When I was little I used to love spending time in the kitchen with her and watching her work. She would talk to me about what she was doing. She was forever trying to improve her recipes, to add a little more of this, a little less of that, so that everyone would he happy.

J’ai souvent pensé à ma grand-mère alsacienne.… Ce qu’elle me donnait, c’est surtout d’y avoir passé pour moi du temps en cuisine. Je la voyais faire; elle ne cessait de perfectionner les préparations, d’y ajouter ceci, d’éviter d’y mettre cela, de me dire ses idées, de tenir compte des goûts de tous.

Hervé This (1955–)

Pearled spelt, beets, and lobster (page 70). This is why it is quite possible to make delicious soups using only these two ingredients. Even more umami can be achieved by adding vegetables and herbs to a simple shellfish bisque.

Pearled spelt, beets, and lobster (page 70). This is why it is quite possible to make delicious soups using only these two ingredients. Even more umami can be achieved by adding vegetables and herbs to a simple shellfish bisque.  Crab soup (page 76). A savory combination of fish, shellfish, vegetables, and seaweeds is to be found in the traditional clambake made on the beach and in a modified version prepared in a pot.

Crab soup (page 76). A savory combination of fish, shellfish, vegetables, and seaweeds is to be found in the traditional clambake made on the beach and in a modified version prepared in a pot.  Clambake in a pot (page 78). The traditional French bouillabaisse is a thick soup made with fresh fish, shellfish, and often vegetables and eggs. It is served with a dollop of rouille, a sauce that is thickened with an egg yolk. It is a felicitous combination of ingredients that are filled with umami substances.

Clambake in a pot (page 78). The traditional French bouillabaisse is a thick soup made with fresh fish, shellfish, and often vegetables and eggs. It is served with a dollop of rouille, a sauce that is thickened with an egg yolk. It is a felicitous combination of ingredients that are filled with umami substances. Crab soup (page 76). After about an hour and a half, we took one of the eggs out from under the canvas. It was not yet cooked through, which meant that the clambake was also not ready, and we had to resign ourselves to waiting a little longer. Half an hour later, we pulled out another egg. It was exactly the consistency of a soft-boiled egg, a sign that we could start to unpack the oven.

Crab soup (page 76). After about an hour and a half, we took one of the eggs out from under the canvas. It was not yet cooked through, which meant that the clambake was also not ready, and we had to resign ourselves to waiting a little longer. Half an hour later, we pulled out another egg. It was exactly the consistency of a soft-boiled egg, a sign that we could start to unpack the oven. Patina de pisciculis (page 82)

Patina de pisciculis (page 82)

Garum (page 86)

Garum (page 86) Quick-and-easy garum

Quick-and-easy garum Smoked quick-and-easy garum

Smoked quick-and-easy garum