Rockdale County, Georgia, is a quiet upper-middle-class suburb about twenty miles outside of Atlanta. The schools there are some of the best in the state, and the annual fair draws large crowds to its church-choir nights and beauty pageants. Some natives of Rockland County have even become quite famous, like actresses Dakota Fanning and Holly Hunter. According to the county’s website, this is a “ ‘family-friendly’ community that is appealing to parents who want a safe, wholesome, and progressive environment in which to raise their children.”1 In short, this is probably not the place you imagine when you think of a teenage syphilis epidemic.

But in 1996, very young teenagers started arriving at Rockdale County health facilities infected with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). When officials began hearing sordid tales from teenagers in middle school and high school who participated in group sex, it became obvious that something strange was afoot. As Georgia’s director of public health, Kathleen Toomey, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “What lit this up for us [was that] syphilis had occurred in a community where you never see syphilis…. It allowed us to be aware of the high-risk behaviors of these teens in Rockdale.”2 Syphilis is an extremely rare disease in the children of the upper-middle class, yet there were seventeen cases of this one sexual pathogen alone, and many more cases of other STDs.

Some of the students of Rockdale County had accumulated dozens of partners. The epidemic, when it was discovered, made a big impression on the adults: “By the time the investigation concluded, seasoned public health investigators trained not to be judgmental would be startled by what they found. There were fourteen-year-olds who had had up to fifty sex partners, sixth-graders competing for the sexual attention of high school students, girls in sexual scenes with three boys at once. In one case,… a girl at a party with thirty to forty teens volunteered to have sex with all the boys there—and did. ‘My heart dropped,’ [Peggy] Cooper [a counselor at one of the middle schools involved] said. ‘I felt nauseated. I wanted to cry.’ ”3

When this situation came to light, people began questioning what made the children in this wealthy community behave this way. It appeared that many of the young people suffered from not having much structure, supervision, or anything else to do. But really, the STDs were a reflection of a different network process: the spread of a norm among the teenagers that sex—and sex of a particular kind, involving multiple partners—was acceptable. The real epidemic, the one at the root of the STD epidemic, was an epidemic of attitudes. Syphilis was not the problem; it was a symptom of the problem.

The schism between the parents and the reality of their children’s sexual activity was clear in the reactions of parents and other adults to the outbreak. As Toomey told the Washington Post, parents were in “tremendous denial” that the local youth were sexually active at all.4 One nurse told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that they “found a lot of lack of communication between children and parents…. Some didn’t know their kids were sexually active. Some, even when presented with evidence, refused to believe it. One woman cussed me out and said she knew her child was a virgin, until I said no, her child was pregnant.”5

A formal investigation involving interviews with ninety-nine of the teenagers, including ten who had been diagnosed with syphilis, reconstructed the network of people connected to one another sexually.6 It found that those with syphilis were extensively connected in the middle of the web. Over time, the network expanded to include more people who were recruited into the sexual practices of the group, making it more likely that syphilis would be transferred to other kids. At the core of the sexual network was a collection of young white girls, most of whom were not yet sixteen. They would participate in group sex with various clusters of boys, connecting separate groups that might not have otherwise been linked. A year later, however, the network had splintered into many smaller networks, in part because of community efforts to address the problem. So while most of the kids remained sexually active, STDs were less likely to spread because the population was no longer interconnected. The epidemic stopped because the network changed.

A spate of research over the past decade has focused on the structure of social networks and their role in determining the spread of STDs. Because these studies involve the examination of traceable and easily detectable germs, and because sex is ipso facto proof of a connection between two people, such studies provide a useful vehicle for examining how pairs of people might come together to form more complex network structures and how this process in turn affects the social experience of individuals and the spread of things other than germs. Studies of STDs demonstrate the emergent quality of networks, that is, how phenomena of interest must be understood by studying the whole group rather than by studying individuals or even pairs of individuals. A person’s risk of illness depends not merely on his own behavior and actions but on the behavior and actions of others, some of whom may be quite distant in the network.

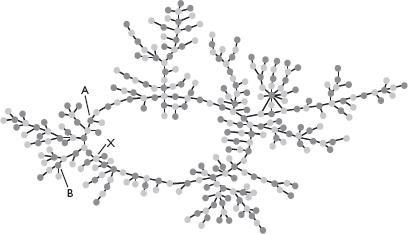

Drawing from the Add Health data, sociologists James Moody and Katherine Stovel teamed up with Peter Bearman to map the complete sexual network of a midsized, predominantly white midwestern high school using information on reported romantic partnerships over an eighteen-month period. This high school, to which they gave the pseudonym “Jefferson High,” was in a community that was superficially similar to Rockdale County. Moody and his colleagues found that a surprisingly sizable 52 percent of all romantically involved students were embedded in one very large network component that looked like “a long chain of interconnections that stretches across a population, like rural phone wires running from a long trunk line to individual houses.”7 This ring-shaped, hub-and-spoke network composed of 288 students was especially notable for its lack of redundant ties, meaning that most students were connected to the superstructure by just one pathway, as shown in the illustration. There was not a lot of transitivity in the network.

Network of 288 students involved in romantic relationships at “Jefferson High School” from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Gray nodes indicate girls, and black nodes boys. Nodes A, B, and X are discussed in the text.

Moody and his colleagues uncovered two particular rules regarding the social—in this case, specifically sexual—interaction in high schools that have a big effect on the structure of this network. First, there is a convention that people have partners that they resemble (our by-now handy homophily principle, here with regard to grade, race, and so on). Second, there seems to be a rule about sex in high school that says, Don’t date your old partner’s current partner’s old partner.

We are pretty sure you had to read that rule a couple of times to make sense of it. We are also pretty sure you did not write it in capital letters at the top of your little black book when you were in high school. Nonetheless, if you consider all the partners you have had, we think you will be hard-pressed to discover a time where you violated this rule. One easy way to check is to ask yourself, “Have I ever swapped partners with my best friend?” Chances are, you have not.

This no-partner-swapping rule is an example of how social processes can determine overall network structure in a way that individuals themselves may not be able to appreciate or influence. That is, people obey a seemingly simple rule (consciously or not) and then wind up being embedded in a network with a particular structure. They cannot meaningfully influence the overall shape of the network, even though it certainly influences them by affecting who they will have sex with and whether or not they will be at risk for acquiring an STD.

One very interesting implication of the rule is that it seems to contradict the patterns we discussed in the previous chapter. Many people date a person who is originally three degrees removed from them, but here we have a rule against getting involved with the friend of a friend of a friend. What is the difference? As it turns out, the gender and specific sequence of sexual relations among these social contacts matters a lot. Most close friendships are between people of the same gender, so the normal course of events is for a heterosexual couple to introduce two of their friends (the man’s male friend is introduced to the woman’s female friend), who can then have a relationship if they choose. However, if a woman leaves her boyfriend to date her best friend’s boyfriend, the jilted boyfriend and the (now probably ex-) best friend are not likely to form a new couple.

Aside from the swinger culture especially prominent in the 1970s, where people engaged in wife swapping or husband swapping, these four-way sexual relationships have always been rare in the United States. This might be because of what Moody and colleagues call the “seconds” problem. The two jilted lovers have both come in second in a competition to someone in the other couple. No one is interested in the battle for the bronze medal at the Olympics, and nobody wants to hook up with their ex-lover’s lover’s ex-lover.

Now that we’ve thought a bit about the structure of the network, let’s think about how that structure affects flow. Imagine person X in the network of romantic partners shown in the illustration on here gets an STD. Imagine that you are person A. You are five partners away from person X and have no real way to know what is happening in her life—who she is sleeping with, what she is thinking, whether she insists her partner use a condom, or what sexual practices she engages in. Yet, you are indirectly connected to this person, and the fact that she has acquired an STD has implications for your life that you will soon appreciate. The germ can spread from person to person and—in five hops—reach you.

Now, however, imagine that a tie two degrees away from you is cut, either because the connection between the two people dissolves (e.g., they no longer have sex with each other) or because they start using condoms (so contagion is interrupted even if a sexual relationship continues). Are you sure to avoid getting the STD? No, not really. Because this is a ring network, and you are on the ring. The structure (which you cannot appreciate unless you have the kind of bird’s-eye view that we have here) is such that the STD can go around the other path of the ring and still reach you. Admittedly, it would take many more hops. But you are not immune from what is happening to others in your network, in some cases even if they stop having sex or use protection.

Now imagine that you are person B. Like person A, you are connected to three sexual partners. You are also five partners away from person X. But now, if a tie two people away from you is cut or interrupted, you are isolated from the epidemic. Your position in the network is actually quite different from person A’s, but you do not have the perspective to see that. As far as you know, you have merely had sex with three partners, just like person A. Without such a complete view of the network, there really is no way for you to acquire that perspective. You are at the mercy of the network you reside in, with only a certain degree of control over who you are connected to directly—but with no control over who you are connected to indirectly.

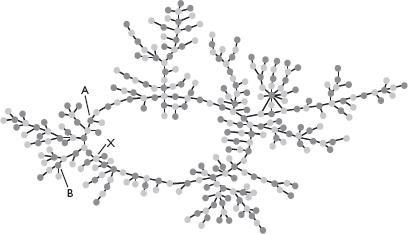

To see why network structure matters, let’s compare the Jefferson High network with another one that involves a similar number of people. The next illustration represents a network of 410 mostly adolescent men and women who were part of an epidemic of STDs occurring over a two-year period in Colorado Springs.8 Just like the Jefferson High network, the Colorado Springs network shows that people obey the no-partner-swapping rule. However, the larger patterns of contact are much more complex, so that cutting one tie is less likely to remove a person from contact with the rest of the network. For example, notice that in both networks person A has had three sexual partners, but in Colorado Springs each of those three partners themselves had many more partners. This increases the chance that one of person A’s partners’ partners will contract the disease and then possibly spread it to person A. So here is a simple rule: the more paths that connect you to other people in your network, the more susceptible you are to what flows within it.

Network of 410 mostly adolescent men and women who were part of an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases occurring over a two-year period in Colorado Springs. Node A is discussed in the text.

Most models of disease transmission assume the existence of highly sexually active “cores” of individuals who disseminate disease to less active individuals at the periphery, and they assume that these cores may sustain epidemics by functioning as reservoirs of infection. For example, network approaches have been used to understand the racial differences in rates of STDs in the United States. Sociologist Ed Laumann and his colleagues proposed that STD rates were higher among blacks than whites because of differences in the two groups’ sexual network patterns.9 A peripheral black person (where peripheral is defined as having only one sexual partner in the past year) is five times more likely to choose a partner in the core (defined as having four or more partners in the past year) than is a peripheral white person. No one has yet discovered why this is the case, but the result is that STDs would be more likely to be contained within the white core, whereas they are more likely to spill out into the black periphery.

In other words, whites with many partners tend to have sex with other whites with many partners, and whites with few partners tend to have sex with whites with few partners. This keeps STDs in the core of active white partners. On the other hand, blacks with many partners have sex with other blacks with many and few partners. Hence, STDs spread more widely through the black population.

A 2001 study used individuals’ reports about their number of sexual partners to make inferences about the “Swedish Sex Network” (which sounds more like an X-rated movie than an academic investigation). It similarly suggested that the network had highly active cores.10 Further, it concluded that safe-sex campaigns would be most effective if messages were directed at high-activity members (the cores, or hubs, of the networks) rather than targeted equally to all members of a community.

A network perspective also helps us get away from thinking that the main risk factors for STDs are individual attributes, such as race. In fact, a more effective approach to understanding risk is to focus on the architecture of a person’s social network, namely their structural position rather than their socioeconomic position. We should not assume that money, education, or skin color cause people to engage in more or fewer risky behaviors. Studies of social networks are showing that people are placed at risk not so much because of who they are but because of who they know—that is, where they are in the network and what is going on around them. This structural perspective sheds new light on many social processes.

The syphilis epidemic in suburban Rockland County demonstrates that specific information about social-network structure and behavior—beyond the simplistic core versus periphery dichotomy or the sexually active versus sexually inactive dichotomy—is highly relevant to the spread of STDs. It shows that if the only link between two groups is removed, the transmission of infection between those groups is effectively halted as the network breaks into disjointed components. Some sexual networks (such as the one at Jefferson High) are highly vulnerable to the removal of a few ties or changes in individual behavior. Under these circumstances, the best prevention strategy is thus a broad-based, “broadcast” STD control program that targets the entire population rather than specific activity groups. Any one person’s change in behavior can break the chain.

However, not all networks have the same shape, and therefore different strategies might work better for different groups. In studying the HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, another group of researchers collected information on recent sexual partners of the residents of seven villages located on an island in Lake Malawi.11 They found that, contrary to expectations, residents reported relatively few partners. There was no distinction to be made between core and periphery, and pretty much everyone had similar levels of sexual activity. The Malawi sex network did not have any high-activity hubs, that is, individuals or groups capable of sustaining the HIV/AIDS epidemic by having many sexual partners.

Despite these findings, however, on mapping the sexual network, the researchers discovered that a striking 65 percent of the population aged eighteen to thirty-five formed one large interconnected component, similar to the Colorado Springs network. Unlike Jefferson High or the Rockland County school networks, this network structure was strikingly robust against the removal of individual ties or nodes since there were numerous redundant paths (i.e., instances in which people directly or indirectly shared more than one sexual partner).

These findings call into question many assumptions about STD transmission in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. The current epidemic is not being driven by a high-activity core made up of sex workers and their patrons, or by other high-activity individuals transmitting disease to a low-activity periphery made up of individuals with one or few partners. Simple enumeration of the numbers of partners per person could not yield these insights without actually mapping the networks.

In short, when trying to understand the spread of STDs, how and even whether the disease spreads depends on the larger patterns of contact in the overall network. Without information on individuals’ partners’ partners and their interconnections to other individuals in the population, we cannot determine whether a person is at high or low risk of contracting an STD. In fact, the situation is even more complex since ideally, in addition to the structure of the network, the way the ties and the overall network structure changes across time should also be taken into account.12 Fortunately, scientists and doctors are becoming more serious about collecting network data, and they are developing techniques to visualize and analyze networks. This will help tremendously in the fight against HIV and other STDs. And it will allow us to study the spread of other health phenomena through social networks that are much less orthodox.

Germs are not the only things that spread from person to person. Behaviors also spread, and many of these behaviors have big effects on your health. For example, peers influence young people’s eating behaviors, particularly weight-control behaviors in adolescent girls. And strangers can have an effect too: people randomly assigned to be seated near strangers who eat a lot wind up doing the same, and the effect can be so subconscious that it has been called “mindless eating.”13 It seems that we just can’t help imitating others.

It turns out that we do not only imitate the people sitting next to us in a classroom or a dining room. We also imitate others who are much farther away. Similar to spreading germs, health-related phenomena can spread from person to person and from person to person to person, and beyond.

Our first effort to understand how this might work looked at obesity. We were drawn to the topic by the widespread claim that there is an obesity “epidemic” in the United States. This turn of phrase conjures up images of a plague out of control, and in fact, the word epidemic has two meanings. First, it means that there is a higher-than-usual prevalence of a condition. Second, it connotes contagion, suggesting that something is spreading rapidly.

It is readily apparent that the prevalence of obesity is rising. A standard measure of obesity is body mass index (BMI is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). A normal BMI is considered to be in the range from 20 to 24, overweight is a BMI of 25 to 29, and obese is a BMI of 30 or more. From 1990 to 2000, the percentage of obese people in the United States increased from 21 percent to 33 percent, and fully 66 percent of Americans are now overweight or obese. What is not obvious is whether obesity can be seen as an epidemic in the second sense of the word. Is the epidemic more than metaphoric? Does obesity spread from person to person? And if so, how?

In order to study this question, we needed a special kind of data. These data were very difficult to come by because we needed to know about whole groups of people and also about their interconnections. We needed to develop data that contained precise information about people’s positions in a large-scale network and about the architecture of their ties—who they knew, and who those people knew, and who those people knew, and so forth. We also needed to know people’s weight and height and a lot of other information about them. And we needed this data across time with repeated observations on all the people in the network. No data set with all these attributes existed at the time we became interested in the obesity problem.

Undeterred, we decided to start with an epidemiological study known as the Framingham Heart Study that has been ongoing in Framingham, Massachusetts, just west of Boston, since 1948. Physicians have learned much of what is known about the determinants of cardiovascular disease from this famous study. When it was initiated, about two-thirds of all adult residents of Framingham signed up to be examined by doctors every two years and, amazingly, those who are still alive continue to be examined. While all of the people in the study originally resided in Framingham, many have since moved throughout Massachusetts and the United States. Their children and grandchildren also signed up to participate in follow-up studies starting in 1971 and 2001, respectively, and they too continue to be followed at regular intervals.

Quite by chance, we discovered that the Framingham Heart Study kept meticulous, handwritten records so that staff can reach participants every two to four years to remind them to come back for examinations. We could not believe our luck because these records—which had not previously been used for research purposes—included detailed information about the friends, relatives, coworkers, and neighbors of each participant. And since Framingham is a close community, a lot of the people who were relatives or friends or coworkers or neighbors of the participants were also, coincidentally, participants in the study. We were thus able to use these records to painstakingly reconstruct the social networks of all the subjects. Ultimately, we were able to map more than fifty thousand ties (not counting connections to neighbors) by focusing on a key group of 5,124 people within a larger network composed of a total of 12,067 people. We could also study how the ties changed from 1971 to the present and link the new social-network data to preexisting information about people’s weight, height, and other important attributes.

To better understand these complex data, our first step was to map the network to see if we could visually discern any clusters of heavy and thin individuals, as shown in plate 3.14 While clustering of obese and nonobese individuals is apparent in this graph, the pattern is extremely complicated. Consequently, we used special mathematical techniques to confirm that there was in fact substantial clustering of obese and nonobese individuals and that the clustering was not merely due to chance. In a surprising regularity that, as we have discovered, appears in many network phenomena, the clustering obeyed our Three Degrees of Influence Rule: the average obese person was more likely to have friends, friends of friends, and friends of friends of friends who were obese than would be expected due to chance alone. The average nonobese person was, similarly, more likely to have nonobese contacts up to three degrees of separation. Beyond three degrees, the clustering stopped.

In fact, people seem to occupy niches within the network where weight gain or weight loss becomes a kind of local standard. These niches might typically involve one hundred to two hundred interconnected individuals. This finding illustrates a more general property of large social networks: they have communities within them, and these communities can be defined not only by their interconnections but also by ideas and behaviors that their members come to share. These ideas and behaviors arise and are sustained in adjoining individuals and depend somewhat on the particular pattern of ties within the region of the network a person inhabits.

Our next challenge was to show that the clusters of obese and nonobese people in the social network did not result solely because people of similar weight tended to hang out together (homophily) or because people shared common exposures to forces that caused them to gain weight simultaneously (confounding)—the familiar issues confronted in the studies of the widower effect and other interpersonal effects. We wanted to see if there was a causal effect, meaning that one person could actually cause weight gain in others, in a kind of social contagion. One way we addressed the impact of homophily was straightforward: we simply included information in the analysis about the kinds of friends people chose, thereby taking the tendency of people to befriend similar people into account. But to deal with confounding required a different approach.

Suppose that Nicholas and James are friends. We ask James who his best friend is, and he says, “Nicholas.” But then we ask Nicholas the same question, and he names someone else. This means that even though Nicholas and James are friends, James is probably more influenced by Nicholas than Nicholas is by James. And if Nicholas and James both name each other (they are mutual best friends), then they probably have a closer friendship than they would if just one of them named the other. So we should expect the strongest influence between mutual best friends.

Now suppose that confounding is the only source of similarity in weight between friends. If Nicholas and James start spending time in a new fast-food restaurant that just opened near them, they may both gain weight (a confounding effect), causing it to look like one of them is affecting the other. But they will gain weight regardless of who named whom as a friend. That means mutual friends, the friends we name, and the friends who name us will all appear to have equal influence. If, on the other hand, there are differences in the magnitude of the effects, then it suggests that confounding is not the only source of the similarity. A hamburger joint that is making both people gain weight does not care who named whom as a friend.

Variation by nature of the friendship tie is exactly what we found. If a mutual friend becomes obese, it nearly triples a person’s risk of becoming obese. Furthermore, mutual friends are twice as influential as the friends people name who do not name them back. And finally, people are not influenced at all by others who name them as friends if they do not name them back. In other words, if Nicholas does not consider James his friend, then James has no effect on Nicholas, even if James considers Nicholas his friend.

In addition to friends, we found that weight gain could spread through a variety of social ties from person to person, but they had to be close relationships. Spouses and siblings influence each other. Coworkers influence each other too, as long as they work in a small company where everyone knows one another. These effects can also spread between people who are not close as long as the effects travel through a series of close relationships in the network. You may not know him personally, but your friend’s husband’s coworker can make you fat. And your sister’s friend’s boyfriend can make you thin.

The final step in our study was to make a series of video animations that tracked the evolution of weight gain and social-network connections across thirty-two years. When we began this work, we thought we would be able to literally see the epidemic unfolding. We had thought we would see one person gain weight and then watch a wave of obesity spreading out from the affected person: first to those one degree away, then two degrees away, then three degrees away, across time and across social space. The image in our heads was based on the physics experiment many people are familiar with: a pebble is dropped in a still pool of water, and a concentric circle of waves moves away from it. If the waves hit a perimeter, they bounce back, and under proper circumstances, they can reinforce each other; peaks and valleys of “standing waves” form, like swells observed offshore that seem not to move. Similarly, we expected to see concentric regions of the social network with peaks and valleys of obese and nonobese people.

Yet when we looked at our video images, the picture was much more complicated. There seemed to be chaotic weight gain all over the place. And we then realized that the proper analogy was not a single pebble dropped in a pool, but rather a whole handful of rocks thrown in over a wide area, creating a choppy surface, obscuring the impact of a single pebble and its waves. Sure, obesity can spread, but it is not spreading from just one spot, and social contacts are not the only stimulus for weight gain. People take up eating, stop exercising, get divorced, lose a loved one, stop smoking, or start drinking, and each one of these changes can form the epicenter of another tiny obesity epidemic, like the thousands of overlapping earthquakes that shake our tectonic plates every year. The movie was telling us something very important: the obesity epidemic does not have a patient zero; it is not a unicentric epidemic but a multicentric epidemic.

When our findings that obesity is contagious were published in 2007, they elicited strong reactions. We received hundreds of e-mails and noted hundreds of blog posts about this work. Some people exclaimed indignantly, “Well, of course obesity can spread like a fad.” After all, body types come in and out of fashion, don’t they? One year the frail waif is in fashion, and the next year it’s the buxom Brazilian supermodel. Any casual observer of military history can see the huge change in male body type between World War II and the Iraq War just by looking at photographs of soldiers awaiting deployment. “And, by the way,” our critics noted, “what a colossal waste of money it is for social scientists to prove the obvious.” But others had quite a different response, equally outraged, to the suggestion that something so personal, so individual, so clinical, as weight gain could remotely be subject to the vagaries of popular tastes. “Weight can’t possibly be contagious!” they said, “Everyone knows that weight gain is a function of genes and hormone levels and all kinds of choices and opportunities that people face. There must be something wrong with your research. And, by the way, what a waste of money it was.”

But we now know that obesity is contagious. Since the publication of our study, we and three other independent teams have identified obesity contagion in other populations.15 And there is something both commonsensical and novel about this observation. But how is obesity contagious? What other health phenomena might spread in this way? And what are the implications of knowing that a key feature of our health depends on a key feature of the health of others near and far in our social networks?

Longshoreman and social critic Eric Hoffer once opined, “When people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate each other.” And imitation is one way obesity might spread from person to person. If you start a running program, then your friend might copy you and start running; or you might invite your friend to go running with you. Similarly, you might start eating fattening foods, and your friend might follow suit; or you might take your friend to restaurants where you eat fattening foods together.

Behavioral imitation can be either conscious or subconscious. In chapter 2 we noted that when we see someone eat or run, our mirror neurons fire in the same part of the brain that would be activated if we ourselves were eating or running. It is as if our brains practice doing something that we have merely been watching. And this practice in turn makes it easier for us to exhibit the same behavior in the future. There are still other physiological processes underlying imitation, such as those pertaining to contagious yawning or laughter.16 Imitation, in other words, can be cognitive (something we intentionally think about) and physiological (a natural biological process). It is deeply rooted in our biological capacity for empathy and even morality, and it is connected to our origins as a social species, as we will discuss in chapter 7.

But imitation is not the only way that obesity can spread. Human beings also share their ideas with one another, and these ideas can affect how much we eat and also how much we exercise. For example, we might look at those around us and see that they are gaining weight, and this might change our ideas about acceptable body size. When many people start gaining weight, it can reset our expectations about what it actually means to be overweight. What spreads from person to person is what social scientists call a norm, which is a shared expectation about what is appropriate.17 Just as the Rockdale County teenagers adjusted their sexual norms (to the dismay of the adults), people’s ideas about what is considered fat have changed rapidly. And niches within a social network can arise. In these niches, people can reinforce particular norms so that directly and indirectly connected people share an idea about something without realizing that they are being influenced by one another.

These two mechanisms—behavioral imitation and norms—can be found in some of the examples we gave in the previous chapter for how marriage affects health. But it can be difficult to tell them apart. When a man gives up his motorcycle after getting hitched, is he copying his wife’s behavior (she doesn’t have a motorcycle) or adopting a new norm (the infernal things are unsafe)? Moreover, having accepted the idea that weight gain is normative, a person might go on to exhibit either the same or entirely different weight-gain behaviors from those around him. People around you might eat poorly and consequently gain weight, but you might wind up exercising less rather than copying the bad eating habits. While the norm that spreads is the same in this scenario (weight gain is OK), the behavior is not. Thus, there can be a concordance of norms even if there is not a concordance of behaviors. The spread of obesity is not simply a matter of monkey see, monkey do.

In the case of obesity, there is evidence that normative influences are at work. First, the spread of obesity in social networks still occurs even after accounting for the interpersonal spread of particular behaviors that contribute to obesity. That is, even if we do statistical analyses that take into account the fact that two people might copy each other’s behaviors, we still find evidence that something more is going on, that weight gain and loss still spread.

Second, obesity can spread even between socially close people who are very far apart geographically. Remarkably, our evidence in the Framingham Heart Study suggested that social contacts a thousand miles from each other can influence each other’s weight. Since we only rarely see our friends and family who live so far away, it is unlikely that the effect results from simple imitation. Suppose, for example, that you see your brother once a year at Thanksgiving, and he has gained a lot of weight. Copying his eating behavior on that one day will not affect your long-run weight status. But seeing him in his new, bigger physique can reset your expectations about acceptable body size. “Wow,” you say, “Dimitri has put on some weight, but he is still Dimitri.” When you go home, you can still carry this idea with you (“Dimitri looks fine”), and it influences your behaviors; you might eat more, and you also might exercise less.

Norms can spread even if they do not affect a person’s behavior. Some people can be carriers of an idea without themselves exhibiting the behavior related to the idea. As a result, you might seem to affect your friend’s friend without affecting your friend. Think of it this way: Amy has a friend Maria, who has a friend Heather, and Amy and Heather do not know each other. Heather stops exercising and gains weight. Since Maria likes Heather, this influences Maria’s thinking about what it means to be overweight, and Maria comes to think that it is not so bad to be heavy. Maria does not change her own behavior. However, she might become more tolerant of people who eat a lot or who do not exercise much. So, when Amy stops her exercise regime (she used to go running every week with Maria), Maria is less likely to pressure Amy to continue. Given the shift in Maria’s ideas about weight gain, even if Maria’s own behaviors have not changed, this affects Amy. Hence, Heather’s actions can affect Amy even if Maria’s actions do not change.

How can people detect and imitate local network norms about the acceptability of weight gain when our society as a whole still appears to privilege thinness? Celebrities and models are thinner than ever, even if everyone else is gaining weight. This paradox illustrates the difference between ideology and norms. People see images of ideal body types in the media, but they are less influenced by such images—by this ideology—than they are by the actions and the appearance of the very real people to whom they are actually connected. As columnist Ellen Goodman put it: “Professional anorexics such as Kate Moss, Calista Flockhart, and Victoria Beckham may present an incredibly shrinking ideal. But in real life we measure ourselves against our friends. Inch for inch.”18 As we will see in chapter 6, the same sort of thing happens with political beliefs.

It is worth stressing that social-network effects are not the only explanation for the obesity epidemic. Over the past twenty years, there have been enormous changes that promote inactivity—such as labor-saving devices, sedentary entertainment, suburban design, and the general transition to a service economy. There have also been dramatic changes in food consumption, resulting from the decreased price of food, shifts in nutritional content and portion size, and increased marketing. Yet social networks also play an important role. As we have discussed, networks can magnify whatever they are seeded with, though other external factors are the initial drivers of the obesity epidemic. If something takes root in a networked population, whether a pathogen or a norm about body size, it can spread across social connections, striking ever larger numbers of people.

Connection is just as important when it comes to health phenomena beyond obesity. People copy the substance-use, drinking, and smoking behaviors of people they know directly and, more remarkably, of others who are farther away in the social network. Just as understanding social networks helps us understand the sharp rise in obesity in our society, it can also help us understand the sharp decline in smoking, the relative persistence of drinking, and a wide variety of other activities that affect our health.

Over the past forty years, smoking among adults has decreased from 45 percent to 21 percent of the population. Whereas forty years ago, offices, restaurants, and even airplanes were thick with cigarette smoke (the rule against smoking in airplanes was hailed as a great advance in 1987), nowadays smokers huddle together in small groups outside buildings.

But people have not been quitting by themselves. Instead, they have been quitting together, in droves. We used our social-network data from the Framingham Heart Study to analyze the decline of smoking over the past four decades, and we found patterns that looked like the obesity epidemic in reverse.19 When one person quits smoking, it has a ripple effect on his friends, his friends’ friends, and his friends’ friends’ friends. As in the case of obesity, smoking behavior extends out to three degrees of separation, consistent with our Three Degrees of Influence Rule. But the group effects are even stronger for smoking than obesity. There is a kind of synchrony in time and space when it comes to smoking cessation that resembles the flocking of birds or schooling of fish. Whole interconnected groups of smokers, who may not even know one another, quit together at roughly the same time, as if a wave of opposition to smoking were spreading through the population. A smoker may have as much control over quitting as a bird has to stop a flock from flying in a particular direction. Decisions to quit smoking are not solely made by isolated individuals; rather, they reflect the choices made by groups of individuals connected to one another both directly and indirectly.

Anthropologists have a word for local customs: culture. But the culture we are discussing here is local in the sense of being confined to groups of interconnected people in one region or niche of the social network rather than in one geographic place or among one group defined by a shared religion, language, or ethnicity. And the culture within regions of the social network can change. Interconnected groups of individuals may find smoking unacceptable and quit in a coordinated fashion, mutually influencing one another but without necessarily knowing each other personally or explicitly coordinating their behavior. What flows through the network is a norm about whether smoking is acceptable, which results in a coordinated belief and coordinated action by people who are not directly connected. This is an important way that individuals combine to form a superorganism.

Smoking behavior reflects the workings of a superorganism in still other ways. First, people who persist in smoking find themselves progressively marginalized in the network, as shown in plate 4. In 1971, smoking had no bearing on social position: smokers were just as likely to be central to their local networks as nonsmokers, to have as many friends as nonsmokers, and to be located in the middle of large extended groups. However, as more and more people quit smoking over time, the smokers were forced to the periphery of their networks, just as they are now forced outdoors to smoke, even in the freezing cold. And it’s not just that they became less popular; they also tended to be friends with people who were less popular, which helped to speed up the dramatic increase in their social isolation.

Second, although smokers and nonsmokers were well mixed in the early 1970s, over time they each formed their own cliques within the network, with progressively less interconnection by the early 2000s. As in the case of the polarization between Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. Congress (discussed in chapter 6), the separation between smokers and nonsmokers has increased over time, and the consequences extend far beyond the habit itself. When such deep divisions occur, they lead to the formation of identities within each group, which prevents further mixing and reinforces group behavior. More connections within groups (in what is known as a concentrated network) can reinforce a behavior in the groups, but more connections between groups (in what is known as an integrated network) can open up a group to new behaviors and to behavioral change—for better or for worse.

The spread of smoking cessation also illustrates the role of high-status individuals in the diffusion of innovations. In our Framingham data, education appears to amplify a person’s ability to influence others: a person is more likely to quit smoking when a well-educated social contact quits. In addition, education increases a person’s desire to innovate: a well-educated individual is more likely to imitate the smoking-cessation behavior of his peers than is a less-educated individual. Hence, ironically, in the case of smoking, the present wave of cessation mirrors in the obverse what happened sixty to one hundred years ago: when smoking first took root in our society, it did so among those with relatively high status. Ads from the 1930s and 1940s show smiling doctors enjoying and promoting tobacco.20

Just as the educational status of individuals in the network is related to the spread of smoking along paths through the network, gender is relevant to the spread of drinking. The Framingham social network reveals that drinking behavior clusters to three degrees of separation, as do smoking and obesity. But the flow of influence does not pass through everyone equally—instead, drinking appears to be greatly influenced by women. If a woman starts drinking heavily, both her male and her female friends are likely to follow suit. But when a man starts drinking more, he has much less effect on either his female friends or his male buddies down at the bar. It is not yet clear why this is so, but it suggests that women are the key to the spread throughout the network, and they may therefore be the key to successful interventions.

Drinking has been relatively steady in the United States, but the situation is not so stable in other countries. For example, in the United Kingdom, there is a new problem with public binge drinking. Increasing numbers of young men and women are rapidly consuming large amounts of alcohol (as many as ten drinks per sitting) and then engaging in public behaviors such as vomiting, collapsing, urinating, shouting, threatening, and fighting. Overall, 16 percent of eighteen- to twenty-four-years-olds in one British sample reported having engaged in binge drinking.21 Among binge drinkers, 54 percent reported that all or almost all of their friends are binge drinkers, compared to 15 percent of nonbinge drinkers. Analysis of these patterns suggests that there is indeed an interpersonal clustering and transmission of the behavior.

While gender and education have an effect on the spread of health behaviors, the type of relationship also matters a great deal. Not all social ties are equal. For example, we find that friends affect each other more than spouses do in the spread of obesity. When we first noted this, we were puzzled because spouses often eat together, exercise together, and spend more time with each other than friends do. However, when we looked more deeply, we found that friends and siblings are much more susceptible to influence by peers of the same sex than by peers of the opposite sex. Thus, although spouses are typically friends, they are also typically of the opposite sex, and the two effects can cancel each other out.

Other health-related behaviors that might spread within social networks include the tendency to get health screenings, visit doctors, comply with doctors’ recommendations, or even visit particular hospitals. One study found that Harvard students were 8.3 percent more likely to get a flu shot if an additional 10 percent of their friends got a flu shot.22 Moreover, symptoms can spread from person to person due to biological and social mechanisms. In chapter 2, we saw that anxiety and happiness can spread, but so can headaches, itches, and fatigue.

Back pain is yet another example of a condition that can spread via social networks. A group of German investigators studied the possible transmission of back pain by exploiting a natural experiment provided by the reunification of Germany. Before the Berlin Wall fell, East Germany had much lower rates of back pain than West Germany, but within ten years of reunification, rates had converged to be the same, with East Germany emulating West Germany’s higher rates. Exposure to new media messages among formerly insulated East Germans about how back pain was “frequent and unavoidable” and “a diagnostic and therapeutic enigma in need of careful medical attention” appeared to play a role. But these investigators also argued that back pain was a “communicable disease” and that a kind of “psychosocial decontamination” might be helpful to break the transmission.23 Thinking of back pain in this way can shed light on another mystery: it can help explain why prevalence rates vary widely among industrialized countries. The rate of lower back pain among working-age people is 10 percent in the United States, 36 percent in the United Kingdom, 62 percent in Germany, 45 percent in Denmark, and 22 percent in Hong Kong.24

In some ways, this varying prevalence, and the culturally specific ways in which back pain is experienced, suggest that back pain can be seen as a culture-bound syndrome—a disease recognized in one society but not others, such that people can experience the disease only if they inhabit a particular social milieu. The classic example of a culture-bound syndrome is Koro, a condition that is seen in some Asian countries and that involves intense anxiety arising from the conviction among afflicted men that their penises are receding into their bodies and might disappear, and that they might die as a result. The treatment consists of asking trusted family members to hold the penis twenty-four hours a day for some number of days to prevent it from receding. To the eyes of outsiders, this condition has no biomedical or clear etiological basis. Yet it is very real to those who suffer from it. Indeed, there have even been epidemics of Koro, as documented in Malaysia and southern China (where it goes by the name of suo yang). To Malaysians—who probably have a low prevalence of back pain—the fact that many Americans have a biomedically difficult-to-diagnose condition that requires those affected to miss work and that usually has no objective physical signs may strike them as equally inexplicable.

A similar argument can be made that anorexia and bulimia are culture-bound syndromes. These conditions are much more prevalent in wealthy industrialized countries, and, even within these countries, they tend to strike white, middle-class, adolescent girls with much greater frequency than other groups. Their prevalence has been increasing since 1935; roughly 0.5 to 3.7 percent of American women have suffered from anorexia and 1.1 to 4.2 percent from bulimia (rates in men are about a tenth of these).25 While these conditions are entirely real for their sufferers and their families, their origins are obscure. What triggers the eating behavior? In addition to being culturally specific, eating disorders resemble other culture-bound syndromes in that they can ripple through a social network in waves, reflecting the possibility of person-to-person transmission of (admittedly severe) weight-loss behavior. High-school girls may compete with one another to lose weight and college dormmates can copy one another’s binge eating. In fact, these behaviors may affect a person’s network location, and in one study of sororities, women who were binge eaters actually became more popular and moved to the center of the social network, just as nonsmokers did in our study.26 As such, epidemics of eating disorders are an extreme example of the transmission of weight behaviors we documented in the Framingham Heart Study population.

Suicide contagion is perhaps the most devastating illustration of the power of social networks. There are many causes of suicide, but the idea that people could kill themselves simply because others do seems to defy rational explanation. It certainly calls into question the whole notion that suicide is merely an individual act.

Suicide clusters have occurred throughout the world in communities of all types—rich and poor, big and small. Examples are even known from antiquity. While some clustering of suicides might be expected to occur due to chance, many of the clusters reflect contagious processes and are not due to chance, confounding factors, or homophily (among people who somehow have a prior inclination to kill themselves).27 These clusters are different, in other words, from ones that are organized by charismatic cult leaders like Jim Jones, who led more than nine hundred of his followers in mass suicide in 1978 (a particularly powerful example of both confounding and homophily).

The classic investigation of suicide contagion was published by sociologist David Phillips in 1974.28 He showed that during the period from 1947 to 1968, suicides increased nationally in the month after a front-page article appeared in the New York Times describing someone who had taken his own life. Phillips dubbed this “the Werther effect,” after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther published in 1774. The novel was read widely, and when some young men began committing suicide in a way that copied the protagonist, authorities in Italy, Germany, and Denmark banned the book.

There are two kinds of suicide cascades: those that work through media contagion, like Young Werther or the front page of the Times (these can involve either fictional or factual accounts), and those that work through direct contagion among people who are connected to a person who has killed himself.

Concerns about media contagion have been sufficiently serious that they have led the Centers for Disease Control to suggest alternative ways of publicizing the occurrence of suicide.29 The CDC has even promulgated sample obituaries for journalists. Here is the type of news report the CDC feels has “high potential for promoting suicide contagion”:

Hundreds turned out Monday for the funeral of John Doe Jr., 15, who shot himself in the head late Friday with his father’s hunting rifle. Town Moderator Brown, along with State Senator Smith and Selectmen’s Chairman Miller, were among the many well-known persons who offered their condolences to the City High School sophomore’s grieving parents, Mary and John Doe Sr. Although no one could say for sure why Doe killed himself, his classmates, who did not want to be quoted, said Doe and his girlfriend, Jane, also a sophomore at the high school, had been having difficulty. Doe was also known to have been a zealous player of fantasy video games. School closed at noon Monday, and buses were on hand to transport students who wished to attend Doe’s funeral. School officials said almost all the student body of twelve hundred attended. Flags in town were flown at half-staff in his honor. Members of the School Committee and the Board of Selectmen are planning to erect a memorial flagpole in front of the high school. Also, a group of Doe’s friends intend to plant a memorial tree in City Park during a ceremony this coming Sunday at 2:00 p.m.

Doe was born in Otherville and moved to this town 10 years ago with his parents and sister, Ann. He was an avid member of the high school swim team last spring, and he enjoyed collecting comic books. He had been active in local youth organizations, although he had not attended meetings in several months.

And here is a suggested news report that the CDC feels has “low potential for promoting suicide contagion”:

John Doe Jr., 15, of Maplewood Drive, died Friday from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. John, the son of Mary and John Doe Sr., was a sophomore at City High School.

John had lived in Anytown since moving here 10 years ago from Otherville, where he was born. His funeral was held Sunday. School counselors are available for any students who wish to talk about his death. In addition to his parents, John is survived by his sister, Ann.

Helpfully, the CDC notes that “the names of persons and places in these examples are fictitious and do not refer to an actual event.” Perhaps the CDC wants to avoid the possibility of inducing suicide even with fictitious reports. The point is that the second news report omits the personal and sympathy-inducing elements of the first. The CDC guidelines recommended that news reports not explain the method of suicide or mention how “wonderful” the deceased teenager was; they should also refrain from suggesting that the suicide helped solve the teenager’s problems, for example, by getting even with Jane (“When contacted, Jane sobbed as she reported how much she missed John”).

This works. When Vienna, Austria, finished its subway system in 1978, it was not long before people started using it for a purpose for which it was not intended: they flung themselves in front of the trains. Media reports were vivid, and suicide attempts (half of which were successful) numbered nearly forty per year. Viennese psychiatrists became concerned and started working with journalists. Changes in the reporting of suicides were implemented in 1987, and there was an immediate and enormous drop in suicide attempts to roughly six per year thereafter.30

Since Phillips’s 1974 paper, the sophistication of suicide analysis has risen tremendously, and the geographic scale has narrowed to focus on localized outbreaks and those that occur by direct contagion. As in the case of MPI, the burden seems to fall especially heavily on schools and on small communities that are, as the saying goes, “tightly knit.” Moreover, suicide contagion occurs almost exclusively among the young. Adults older than twenty-four show little, if any, excess likelihood of killing themselves if someone they know has done so or if they simply read about a suicide in the paper.31 But teenagers, who are especially impressionable and susceptible to peer effects in so many domains of their lives, are another matter. The link between the subject’s age and susceptibility is yet another illustration of how the attributes of the nodes on a network are crucial in determining the flow of the phenomenon at hand.

Here is how such outbreaks unfold. The average suicide rate in Manitoba, Canada, is 14.5 cases per 100,000, but in 1995, in a village of 1,500 people in the far north, the rate was 400 per 100,000. Six young people took their lives, mostly by hanging, in four months. A further nineteen attempted suicide. A sense of the epidemic, and how it spread through personal connections between the people in this small town, can be appreciated by the urgent report of one of the doctors who was flown in to help care for this community. This is his description of the events at the local health clinic during a three-day period that began two weeks after the last of the six successful suicides, when serious lingering effects were still observable:

A nineteen-year-old man presented to the health centre two weeks after the sixth suicide. The police were worried about him. “Three of my friends passed away, and I can’t take it anymore.” He had tried to hang himself in his bedroom two weeks earlier. His brother and a friend had discovered him and cut the rope. After a cousin died on the winter road the previous year, this man had tried to shoot himself and was prevented from doing so by his parents. He spent the night in jail, took to his room for a week, and “felt better.” At the time of assessment, he acknowledged hearing the voices of two of the victims beckoning him to come with them. This occurred mostly when he was alone and was frightening. Vegetative symptoms of depression were not present. He requested an opportunity to “talk and get things out.”

A thirteen-year-old boy was seen the same day because his father was worried about him. Collateral history revealed that the first suicide victim was the boy’s cousin; he had discovered the second victim still hanging. His brother-in-law was the third victim. He denied suicidal ideation and had not attempted self-harm. The patient did not want to go to school anymore. He felt lonely, and dreams about the deceased frightened him. Playing hockey with a brother and cutting wood with his father were his favorite activities.

The following day, a fifteen-year-old girl was assessed. She was silent for the first fifty minutes before disclosing that two of the victims were her cousins. She acknowledged having heard her cousins’ voices beckoning in the past but not for the last three weeks.

A twenty-three-year-old woman presented later that day. She had increased her alcohol consumption since the suicides. At one point she had written a suicide note, but the third victim, her uncle, “beat me to it and stole the show.” She burned the note…. The second suicide victim was the niece of her boyfriend. The patient heard someone calling her name….

A fourteen-year-old girl, who was a friend to four of the victims and a cousin of a fifth, was brought in by her mother. She had had a dream that her cousin was smiling at her while he was hanging from a rope. One month earlier, she had been sent out for assessment after a hanging attempt. She had had previous suicide attempts.

A fourteen-year-old boy was seen next. He had tried to hang himself four months previously. All six victims were known to him. One was a cousin. Prior to his attempt, he had a dream about “a woman with long hair, a little bit spiky on top, with a black face and a long coat.” He said, “Everyone here sees that woman at night.” This boy also experienced someone beckoning but could not say who it was.

Later that night, a fourteen-year-old girl was brought in by the… constables…. At 9:00 p.m. she had taken seven glyburide tablets [a medication for diabetes] and then told a friend. Both of the females who committed suicide were friends. One week earlier she had seen one of these girls in a dream telling her to kill herself.32

The foregoing record is overwhelmingly depressing just to read. One can readily imagine what it must have been like for the people in this village to be in the grip of the epidemic.

Another well-documented outbreak took place in a high school of 1,496 students in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Two students killed themselves within four days, apparently prompted by the suicide of a twenty-one-year-old former schoolmate; and during an eighteen-day period that included these two cases, an additional seven students attempted suicide, while another twenty-three reported thinking about killing themselves.33 It was possible to trace out transmission of suicide since the first high-school student was a friend of the ex-student and an acquaintance of the subsequent student who killed himself. Moreover, many of the kids who thought about killing themselves, or who tried to do so without success, had demonstrably close social ties to the kids who succeeded and to each other. Although many of the kids in this cluster had a prior history of depression, many did not. This brings up a key issue with respect to suicide cascades: does knowing someone who has taken her life merely encourage others who would eventually have attempted suicide to follow suit, or does knowing someone who has killed herself recruit new victims to the epidemic? This question is analogous to the one we considered in chapter 3 with respect to fertility cascades, and there we saw that a sibling having a baby did not just accelerate a person’s having a baby, it actually increased the total number of babies a person had.

Direct contagion can work the same way for suicide that it does for obesity, that is, via a spreading of ideas rather than by shared behaviors. Suicide in one person may lower the threshold for others to follow suit by changing attitudes and norms. It may increase the sense that it is something desirable to do (“look how all these people are so sad at the death of that person”). A case of suicide may make a person feel that the usual normative pressure to refrain from killing oneself is partially suspended. Suicide in a familiar person may also provide information about how to do it. Of course, in some cases, it may even involve collaboration (as in documented cases of Internet suicide clubs in Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and many other developed nations, which are formed by two or more strangers for the purpose of killing themselves together or simultaneously).34

The most recent examinations of suicide cascades have merged network methods and very large data sets to further investigate and confirm direct contagion. A study of 13,465 adolescents in Add Health confirmed that having a friend who committed suicide increased the likelihood of suicidal ideation. Boys with a friend who had killed himself in the previous year were nearly three times as likely to think about killing themselves than they otherwise would be and nearly twice as likely to actually attempt it. Girls with a friend who had killed herself were roughly two-and-a-half times more likely to think about killing themselves and also nearly twice as likely to actually attempt it. But, with the Add Health data, it was possible to examine a host of other features related to a person’s position in the social network. In addition to being stimulated by the suicide of a friend, other social-network structural risks of suicide include having fewer friends and being in a situation where your friends are not friends with one another (namely, having lower transitivity in your network). Adolescent girls (but not boys) whose friends are not friends with one another are subject to possibly conflicting norms about how to live their lives, and this may be stressful. It increases suicidal ideation more than twofold.35 It’s a sort of “If you two can’t get along, I am going to kill myself!” effect.

Suicide contagion is not entirely unknown in adults. One study of 1.2 million people living in Stockholm during the 1990s found that men (but not women) who had coworkers who killed themselves were 3.5 times more likely to commit suicide than they otherwise would have been.36 Interestingly, just as with obesity, which we found to be transmitted between coworkers only at relatively small firms, one person killing himself appeared to increase the risk of others doing so only in firms with fewer than one hundred employees. A person is more likely to have a real connection to the victim at a smaller firm than at a larger one.

There has actually been a smoldering but broad-based epidemic of suicide in the United States over the past few decades. A 1997 study found that 13 percent of American adolescents seriously considered suicide in the previous year, and 4 percent of adolescents actually attempted it.37 Moreover, 20 percent of adolescents reported having a friend who had attempted suicide in the previous year. From 1950 to 1990, the rate of successful suicide for people fifteen to twenty-four years of age increased from 4.5 to 13.5 per 100,000.38 Interestingly, there has also been an epidemic of fictional suicides over the same time frame. According to one analysis of movie plots drawn from an Internet movie database, IMDB.com, the percentage of total movies featuring a suicide rose from about 1 percent in the 1950s to over 8 percent in the 1990s.39 Whether these two increases are connected, and which came first, is hard to know for sure. But it is clear that connections that can make us happy can also make us suicidal.

“You make me sick” is a colloquialism, but it reflects a reality. Our health depends on more than our own biology or even our own choices and actions. Our health also depends quite literally on the biology, choices, and actions of those around us.

This claim may strike some as anathema. Particularly in the United States, we are accustomed to seeing our destinies as largely in our own hands: we “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps” and believe that “anyone can strike it rich.” We see our society as a meritocracy that rewards sound choices and creates opportunities for the well prepared. The radical individualist perspective is that we are masters of our destiny, and that by making changes in everything from what we eat to how we brush our teeth, we can improve our survival chances, our mental stability, or our reproductive prospects.

But the picture is much more complicated. Our unavoidable embeddedness in social networks means that events occurring in other people—whether we know them or not—can ripple through the network and affect us. A key factor in determining our health is the health of others. We are affected not only by the health and behavior of our partners and friends but also by the health and behavior of hundreds or thousands of people in our extended social network.

Most people know little about how the health of the public is protected. And what we do know, we think about in very self-oriented terms: the surgeon general’s warning on the side of a cigarette pack or the nutrition labels on foods are targeted at individual users, not at the community as a whole. We do not ordinarily appreciate the ways in which one person choosing certain behaviors affects the health of others and why this provides a basis for public health.

Yet, we know that smoking-and alcohol-cessation programs and weight-loss interventions that provide peer support are more successful than those aimed at solitary individuals. Programs like Weight Watchers and Alcoholics Anonymous work precisely in this way: they cultivate the formation of social ties and group solidarity. Experiments confirm the beneficial impact of such interventions. One study randomly enrolled subjects in a weight-loss intervention in one of three ways: subjects could enroll alone, they could be assigned to a team of four people, or they could enroll as part of a team of four people that they formed (a method similar to that used for microloans to the poor, as will be discussed in chapter 5). Weight loss was 33 percent greater and also more durable when people were part of a group.40

Other experiments have also confirmed the interpersonal flow of health phenomena. For example, one study randomly assigned 357 people to receive a weight-loss intervention or not, but—unusually—it followed the 357 spouses of the subjects. Not only did the subjects in the weight-loss intervention lose weight, so did the spouses.41 The primary mechanism for this was that the untreated spouse copied the eating behavior of the treated spouse, though a broader range of mechanisms was also likely.

A social-network perspective gives new credence to such group-level and family-level interventions, and it confirms that such interpersonal health phenomena might operate on a much larger scale. A network perspective demands a rethinking of the ways we as a society approach health and health care, and it suggests some novel approaches to public health.

Networks could possibly be manipulated in terms of the pattern of connections or the process of contagion so as to foster individual and collective health. If network ties could be discerned on a community-wide scale (for example, using some of the new telecommunications technologies and methods we will describe in chapter 8), we would be able to target influential individuals or those most at risk for being affected by interpersonal health processes. Moreover, if we knew people’s ties on a large scale, we could design interventions to target groups of interconnected people.

As we have seen, people are more influenced by the people to whom they are directly tied than by imaginary connections to celebrities. Network science offers better ways to identify influential individuals by identifying centrally located hubs within the network.42 In order to do this optimally, the entire network must first be drawn. For example, if we were trying to reduce smoking in a high school or workplace, the conventional approach might be to either broadcast a message to everyone or work with a small group that was felt to be especially at risk. In the latter case, these individuals might be identified because they were the poorest, say, or because they were known to be smokers already. But an alternative approach would be to identify the hubs in the social network (who might or might not be poor or smokers) and target them with smoking-cessation messages. Early results with such approaches have documented success in fostering better diets and safer sex.43

Yet, this approach shifts the focus of decades of public health work. It targets neither socioeconomic inequality nor socioeconomic or behavioral vulnerability per se, but rather structural inequality and structural vulnerability. People are placed at risk for bad or good health by virtue of their network position, and it is to this position that public health interventions might beneficially be oriented. In addition to focusing, for example, on whether people are poor or where they live, we might focus on who they know and what kinds of networks they inhabit.

Some recent work has clarified the specific circumstances whereby influential individuals are most apt to be able to exercise their influence. It turns out that influential people are not enough: the population must also contain influenceable people, and it may be that the speed of diffusion of an innovation is more dependent on the properties and number of the latter group than the former.44 The key point, however, is that networks with particular features and topologies are more prone to cascades, that both types of people are required for cascades to take place, and that understanding the shape of the network is crucial to understanding both naturally occurring and artificially induced cascades.

Whether influential people can exercise influence at all may depend entirely on the precise structure of the network in which they find themselves, something over which they have limited control. As we have seen, some networks permit wide-reaching cascades, and others do not. If we light a tree on fire, whether this turns into a conflagration or a campfire depends a lot on what is going on around the tree: how close it is to other trees, how dry the terrain, how large or dense the forest. When the right conditions for a huge fire exist, any spark will set it off, but when they do not, no spark will suffice.

Computer models of the obesity epidemic confirm that targeting central individuals in the network to encourage healthy weight can be an effective strategy, whether these central people are overweight or not.45 But these models suggest an even more unusual strategy: at both the individual and the population levels, it is more effective for you to lose weight with friends of friends than with friends. The problem is this: If you attempt to lose weight with your friends, you might succeed, but this tiny cluster of you and your friends is surrounded by a large group of people exerting pressure to gain weight again. In all likelihood, both you and your friends will thus regain weight.

A good strategy to lose weight, therefore, might be to invite your friends to dinner and ask them to nominate their friends, and then invite those people to join a running club. If you were able to do this, you would also create a social force pressuring your friends to lose weight (since they would be surrounded), and you would create a buffer around you of people who are improving their health behavior.

Understanding networks can lead to still other innovative, nonobvious strategies. Randomly immunizing a population to prevent the spread of infection typically requires that 80 to 100 percent of the population be immunized. To prevent measles epidemics, 95 percent of the population must be immunized. A more efficient alternative is to target the hubs of the network, namely, those people at the center of the network or those with the most contacts. However, it is often not possible to discern network ties in advance in a population when trying to figure out how best to immunize it. A creative alternative is to immunize the acquaintances of randomly selected individuals.46 This strategy allows us to exploit a property of networks even if we cannot see the whole structure. Acquaintances have more links and are more central to the network than are the randomly chosen people who named them. The reason is that people with many links are more likely to be nominated as acquaintances than are people with few. In fact, the same level of protection can be achieved by immunizing roughly 30 percent of the people identified by this method than would otherwise be obtained if we immunized 99 percent of the population at random! Similar ideas can be exploited for the opposite problem, namely, how best to conduct surveillance for a new behavior or a new pathogen (or bioterror attack): do we monitor people randomly or choose them according to their network position? A choice informed by network science could be seven hundred times more effective and efficient.47

Finally, network interventions increase the cost-effectiveness of interventions. For every dollar we spend on improving the health of an employee, we also improve the health of that employee’s relatives, coworkers, friends, and even their friends of friends. This substantially increases the return on the investment. And, in the case of employers or insurers, this can be especially important since roughly two-thirds of workplace health costs are related to health problems in spouses and other dependents of workers. Targeting a worker and improving the health of the worker’s family in the bargain is thus good business. As we will see in the next chapter, there are many ways networks can magnify economic benefits besides health care, and our understanding of economic behavior requires us to come to terms with the idea that no man or woman is an island. People are connected, and their health and well-being are connected.