Manage iCloud Security and Privacy

Throughout this book I’ve mentioned security and privacy issues connected to iCloud. But because of high-profile incidents involving data theft from iCloud users and increasing privacy concerns overall, I want to end the book with some advice about protecting your data.

In the digital world, the words security and privacy are often used interchangeably, but even though they’re related, they’re not the same. Security is freedom from danger or harm, whereas privacy is freedom from observation or attention. Someone can harm you by impersonating you, taking over your account, stealing or deleting data, and so on; security makes such harm less likely to occur. On the other hand, if someone reads your email messages, sees your photos, or learns your location without your permission, you’ve lost your privacy.

It’s possible to have security without privacy and vice versa. But when it comes to a service like iCloud, it turns out that all the steps you might take to improve your security also protect your privacy. For example, choosing an excellent password reduces the likelihood that a stranger might log in to your account and thereby obtain access to your private data.

Start by enhancing your security with a good password and two-factor authentication, discussed just ahead. If you plan to buy a used iOS or iPadOS device, read Check Activation Lock first to make sure you aren’t buying a locked device—potentially one that was stolen. And you can take additional steps to Protect Your Privacy, such as turning off syncing for sensitive data and using a passcode on your iOS and iPadOS devices.

Choose a Good Password

The password associated with the Apple ID you use for iCloud is incredibly valuable. With your username and that password, someone can see all your email, contacts, calendar events, backed up photos—even your current location. And, using Find My Device, anyone with your password can remotely lock or wipe your Macs and iOS/iPadOS devices!

So, choosing a good password is a big deal. You don’t want a password that any other person can guess, or that an automated cracking tool could uncover by brute force. For complete details on what makes one password stronger than another, how an attacker might go about guessing your password, and techniques for increasing password strength while not overtaxing your memory, read my book Take Control of Your Passwords. If you don’t have time to read that whole book, at least follow these tips:

Make your iCloud password unique. Don’t use your iCloud password for any other site or service, because if your password for one site is compromised through a database breach or other leak, every account that uses the same password is at risk.

Choose a long, random password. Your iCloud password should be at least 12 characters long. It should include uppercase and lowercase letters, at least one digit, and at least one punctuation character. And it should be random—any sort of pattern weakens your password. (If you don’t already have a random password generator, a quick web search should turn up many options.)

Use a password manager. Apps such as 1Password, Dashlane, and LastPass can create random passwords for you, store them, sync them across your devices, and fill them in automatically. That takes most of the effort and pain out of using good passwords.

If you want to change your password now, go to appleid.apple.com, click Manage Your Apple ID, and follow the instructions.

Use Enhanced Security Features

Even the longest, strongest, most random password provides no security if someone else finds out what it is. Perhaps someone watches over your shoulder as you type your password at your local coffee shop. Or maybe a spam email message persuades you to enter your password on a phishing site that looks almost exactly like the Apple site. Or an as-yet-undiscovered security bug or exploit exposes your password to an attacker.

In fact, it gets worse—an attacker may not need your password at all! When you set up your Apple ID, you were likely prompted to choose a few security questions and enter their answers. These questions (like “What was the name of your first pet?” or “What is the name of your oldest niece?”) are supposed to be easy for you to remember but hard for an attacker to guess—so that if you forget your password, Apple can ask you these questions as a secondary means of verifying your identity. Answer correctly, and you can reset your password.

Trouble is, someone pretending to be you can claim to have forgotten your password—and if that person calls Apple and correctly answers your security questions, your account could be compromised. And (assuming you answer the security questions truthfully) it’s surprisingly easy for a skilled attacker to find or guess the answers.

Apple, like many other companies (including Dropbox, Facebook, and Google) offers an optional method to bolster your security by adding another authentication element: a dynamic code tied to a device you own. The idea is that you’ll need both your password and this special code to perform certain critical activities with your Apple ID, so that even if someone knew your password, that alone wouldn’t grant access.

Apple offers not one, but two versions of this enhanced security:

Two-factor authentication: The modern version of the process, two-factor authentication, prompts you to allow login attempts and then requires you to enter a code; any trusted Apple device can display both the prompt and the code. Two-factor authentication is the only method available on 10.13 High Sierra or later and iOS 11 or later, and therefore the only method I cover in this book. See Use Two-Factor Authentication, just ahead.

Two-step verification: Apple’s earlier implementation of this system, called two-step verification, supplies the secondary login code via the Find My iPhone app or SMS. It’s available only for those using 10.12 Sierra or earlier, or iOS 10 or earlier. See Apple’s article Two-step verification for Apple ID for details.

Two-factor authentication and two-step verification are optional, but apart from the enhanced security they offer, there are additional reasons to consider using one of them:

Setting up either system eliminates the security questions from your Apple ID—an attacker can no longer use them to break in to your account. So that’s a lovely bonus.

You’ll need to have one of these systems activated in order to Use App-Specific Passwords, and Apple requires app-specific passwords for third-party apps (such as Outlook and BusyCal) that connect to your iCloud account.

Use Two-Factor Authentication

Two-factor authentication for your Apple ID is both simpler and more secure than the older two-step verification method. It’s available to all iCloud subscribers who have at least one device running iOS 9 or later or 10.11 El Capitan or later (although you’ll have better results if all your devices are running compatible operating systems).

With this feature enabled, here’s what you’ll see:

The device you use initially to enable two-factor authentication becomes a trusted device. That means you’ll use this device (along with your password) to authenticate your next device, which then also becomes trusted. You can have several trusted devices.

When you sign in on a device that isn’t yet trusted, you enter your username and password as usual, but then two things happen:

You must click or tap an Allow button that appears automatically on all your existing trusted devices and shows the area from which the new device is trying to sign in. (Once you click or tap it on one device, the alert disappears on the rest.)

On the new device, you must enter a six-digit verification code that’s displayed automatically on the trusted device on which you just tapped Allow. (If you don’t have access to a trusted device, you can receive your verification code via SMS or an automated spoken voice phone call instead.)

Apps that access your iCloud account’s email, contacts, and calendars must Use App-Specific Passwords, just as with two-step verification.

If you try to sign in to your iCloud account using an older device that isn’t running at least iOS 9 or 10.11 El Capitan, or an older Apple TV model, you must get a verification code from a trusted device (or via SMS or phone call) and then append that to your password when you enter it. For example, if your ordinary iCloud password is

x?u3[iFirHKL6XTGand your verification code is295634, you would enterx?u3[iFirHKL6XTG295634as your password.

In practice, I find Apple’s two-factor authentication to be smoother and less cumbersome to use than the old two-step verification, but the setup process is not necessarily intuitive. It’s especially weird for people already using the older system and choosing to switch, because if you had previously turned on two-step verification, you must first turn it off and jump through the additional hoop of setting up security questions—which will become irrelevant a few minutes later, once you turn on two-factor authentication.

To turn off two-step verification, if it was previously enabled:

Go to appleid.apple.com in a browser, sign in, and in the Security section (where it should say “Two-Step Verification On”), click Edit.

Click Turn Off Two-Step Verification and follow the prompts; note that you must select and answer three new security questions (all of which must have different answers) and supply your date of birth.

To enable two-factor authentication:

On a Mac, go to System Preferences > Apple ID > Password & Security (Catalina or later) or System Preferences > iCloud > Account Details (Mojave). Click Security, enter your password, and click Continue. (In some cases, you may have to repeat some or all of this process.) Then click Turn On Two-Factor Authentication.

Or, on an iOS or iPadOS device, go to Settings > Your Name > Password & Security. Then tap Turn On Two-Factor Authentication.

Follow the prompts. These may include answering two of your three security questions and supplying your date of birth and a phone number; you can select either “Text message” (for SMS) or “Phone call” (for an automated voice call).

Once you complete these steps, two-factor authentication is on, which means that you may be prompted for your password and verification code (or, in some cases, an app-specific password) on devices already signed in to your iCloud account.

When you sign in on a new device (or in a browser—for example, if you later visit appleid.apple.com again), the process is as follows:

Enter your Apple ID and password as usual when prompted.

An alert (Figure 36) appears on every already-trusted device. If the presence and location of the sign-in attempt (which is based on the device’s IP address) is what you were expecting, click or tap Allow.

Figure 36: If the area shown on this Mac corresponds to the location where your new device is trying to sign in, click Allow. A six-digit verification code (Figure 37) appears on the device on which you clicked or tapped Allow.

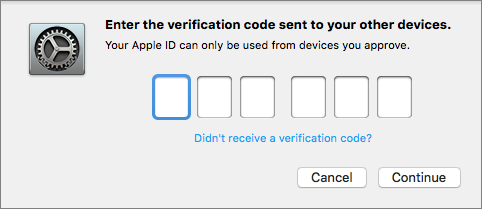

Figure 37: After you click or tap Allow, you see the verification code that you can enter on the device on which you’re signing in. On the device you’re using to sign in, enter the code (Figure 38).

After you complete this step, you’re signed in to your iCloud account; and, if the process took place outside a browser, your new device also becomes trusted.

To learn more about Apple’s two-factor authentication system, read:

Apple’s support articles Two-factor authentication for Apple ID and Availability of two-factor authentication for Apple ID.

Take Control of Your Apple ID, by Glenn Fleishman, which contains detailed, practical steps for setting up and using this feature, along with a look at what to do if you lose a device or forget your password

Use App-Specific Passwords

Enabling two-factor authentication or two-step verification also activates another security feature: app-specific passwords. This feature applies to all third-party apps that access your iCloud account’s email, contacts, and calendars, such as Outlook, Thunderbird, BusyCal, and BusyContacts. (No other kinds of data can be accessed by third-party apps or services.) It does not apply to Apple apps, like Mail, Safari, and Find My Friends, although it was once required for FaceTime, Game Center, and iMessage accounts in Messages.

Your ordinary iCloud password no longer works for these apps when two-step verification or two-factor authentication is active. Instead, you have to create unique passwords for each of them.

Apple makes you go through the two-factor authentication or two-step verification process before you can create app-specific passwords, so you’re still protected by both steps. And once you’ve created such a password for a given app on a given device, you’re never prompted to do so again for that app on that device—unless you change your security settings.

To generate an app-specific password:

Open a third-party app that connects to your iCloud account. (If you’re doing this for the first time after enabling two-step verification or two-factor authentication, you may see an error message stating that your password wasn’t accepted.)

Locate the app’s settings for username and password (often in the Preferences window). Leave the window open.

Visit appleid.apple.com in your browser, sign in, and verify your identity.

In the Security section, under “App-Specific Passwords,” click or tap Generate Password.

Label the entry with something descriptive, so you can later figure out which app it belongs to (such as

BusyCaliMac) and click Create.The new password appears on screen. Copy it and paste it (or type it) into the window you opened in step 2.

If a device is lost or stolen, you may later want to revoke an app’s password. Doing so prevents that app, on that device, from accessing your iCloud account. Follow the same steps, but when you get to step 4, instead click Edit and then click View History. You can then click the X ![]() icon to revoke a single password or Revoke All to revoke them all.

icon to revoke a single password or Revoke All to revoke them all.

Check Activation Lock

iOS and iPadOS devices, Macs with T2 chips (see list here), and Apple Watches can use a feature called Activation Lock, which means no one can turn off Find My Device, erase the device, or reactivate it under a different account without the owner’s iCloud username and password. The intention of Activation Lock is to make devices unattractive to thieves by preventing anyone but the rightful owner from setting it up for their own use.

You won’t see a separate switch for enabling Activation Lock on supported devices; rather, it’s a side-effect of having Find My Device turned on (see Activate Find My (Device)). (For Activation Lock to work on a Mac, the computer must also be running Catalina or later and have Secure Boot enabled, and you must have two-factor authentication set up. Full details on this Apple support page.)

If you’re thinking of selling or donating a device that may have Activation Lock enabled, be sure to turn off Find My Device first in order to disable Activation Lock. If you’re thinking of buying a used Apple device that supports Activation Lock, make absolutely sure you follow the instructions on these pages, or you may wind up with an expensive metal brick:

Protect Your Privacy

At the risk of stating the obvious, any data you sync or share via iCloud travels over the internet and (with a few exceptions) is stored on Apple’s servers. All your data is encrypted while in transit, and most of it is also encrypted while on Apple’s servers. (For complete details, read Apple’s article iCloud security overview.) However, that encryption is irrelevant if:

Someone guesses or discovers your password, and you don’t have two-step verification or two-factor authentication enabled

Your Mac or iOS/iPadOS device is stolen and you haven’t enabled FileVault (Mac) or a passcode (iOS/iPadOS)

Apple is legally obligated to provide your data to law enforcement or a government agency

You can and should take steps to avoid the first two problems, as I explain in a moment. But if you want to eliminate the possibility that your personal data might be handed over to the government, you should not use iCloud at all. I can’t make it any clearer than that.

If you read Apple’s Privacy page, and in particular the Transparency Report that’s linked from that article, you’ll see that the company is taking every possible measure to protect your privacy while complying with the law. Even so, in rare and exceptional circumstances, Apple could be forced to divulge personal data it stores on its servers and to which it has access to law enforcement or a government agency. If that’s a concern for you, to avoid this risk you’ll have to give up all the benefits of iCloud for photos, contacts, email, and anything you can access via the iCloud website when you log in. (All that data is encrypted at rest, but Apple has the keys to decrypt it in order to display it to you.)

Obviously, I use iCloud myself, and I think the average person’s risk of having personal information disclosed to the government is vanishingly small—but if you want an ironclad guarantee of privacy in every situation, iCloud can’t possibly provide that.

That disclaimer out of the way, you can take several concrete steps to protect the privacy of your iCloud data from everyone else—including hackers, thieves, and snoops. Here’s what I recommend:

Use a good password. I already counseled you to Choose a Good Password as a security measure, but I wanted to reiterate that point for the benefit of anyone not reading linearly.

Enable two-factor authentication. Likewise, if you Use Two-Factor Authentication, you’ll make it much harder for anyone to obtain your private data. They have to steal not just your password, but also either steal a device (and be able to unlock it) or hijack your phone number (to get an SMS or voice verification token).

Disable syncing of sensitive data. If you have extremely sensitive data that you want to keep entirely out of iCloud, turn off the relevant feature(s) in System Preferences > Apple ID > iCloud (Mac, Catalina or later), System Preferences > iCloud (Mac, Mojave), the iCloud app in Windows, and Settings > Your Name > iCloud on an iOS or iPadOS device. In particular, you might want to disable:

Contacts: This includes the personal contact information for the people in your address book, plus the VIPs and previous recipients from Mail.

iCloud Drive: Data in this category includes documents (including automatically saved new documents in iCloud-enabled apps), Mail settings (signatures, flag names, rules, smart mailboxes, blocked senders, and muted conversations), and text abbreviations (see Use In-App Data Syncing).

iCloud Keychain: Sensitive data stored under this heading includes scanned or written signatures from Preview or the Markup feature of Mail.

Photos: This includes iCloud Photos and My Photo Stream, as well as any shared albums.

Consider local backups for iOS and iPadOS devices. Although iCloud Backup is handy (see Back Up and Restore iOS/iPadOS Data), the downside is that if someone obtains your iCloud username and password, that person can restore your backed-up data to another device and thus obtain all your photos, email, contacts, and so on. (The risk is greatly decreased, of course, if you use two-factor authentication.) A government agency could also force Apple to deliver and decrypt your iCloud backups.

Especially if you use your iOS or iPadOS device to take racy or otherwise incriminating photos, also keep in mind that even though you may have turned off iCloud Photos and My Photo Stream, your backups will still have copies of photos you might prefer to keep out of the cloud. Anyone who needs to protect the privacy of their photos at all costs should consider turning off iCloud Backup and instead backing up to a Mac or PC using the Finder or iTunes. See How to back up your iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch for details.

Use a passcode on iOS/iPadOS devices. If your iOS or iPadOS device is locked with a passcode, anyone who steals or finds the device won’t be able to access its contents. You can even configure your iOS or iPadOS device to erase its contents after 10 unsuccessful passcode attempts. Turn on a passcode in Settings > Passcode, or in Settings > Touch ID & Passcode (or Face ID & Passcode).

Use FileVault on your Mac. The Mac’s built-in FileVault feature encrypts everything on your Mac’s hard disk or SSD to make it inaccessible without your password.