![]()

How Big a Long Shot Will You Play?

IN THE EARLY 1970s, when I was an analyst, nothing was online. Nada. Zilch. Today, the analysts at major brokerage houses have immediate access to competitors’ reports, estimate changes, and volumes of other information. There is exponentially more information available now than back then. It’s like moving from a hand-cranked telephone to the latest iPhone. Yet in spite of the information revolution, there is every reason to believe, as we’ll soon see, that earnings estimate errors remain enormously high, much too high to be of any use in determining the intrinsic value of most stocks. It isn’t a matter of my colleagues in the industry not giving their all, either. Rather, as you undoubtedly know, iPhone-equipped or not, forecasting is far from an exact science. The weather forecaster who sends you out for a sunny day only to leave you drenched in an afternoon shower has more in common with a Wall Street security analyst than you might think.

If you’re like me, you’ll occasionally take a chance at winning a reasonable poker pot. But more generally, how big a long shot will people play? When analysts like an idea, it can be off the chart. As we saw in chapter 2, if players think they are going to win, they’ll readily pay the same price for a lottery ticket whether the odds are 10,000 to 1 or 10 million to 1 against winning. As we also saw, the possibility of winning, rather than the probability of doing so, can cause very low odds to carry great weight, even when the probabilities against the players are increased by 1,000 times.

Are those people daft? Maybe a little, but, as we have seen, many investors have played with the same odds in every bubble and mania that we’ve looked at. They also play with odds that are against them—certainly not as spectacular but still high—in far more tranquil markets. Why do they do it so consistently?

If you watch an early-morning market show on CNBC or Bloomberg or read The Wall Street Journal to start the day, you have undoubtedly noticed that the anchors or reporters attentively listen to or write about the advice of a collection of well-dressed men and women who seem to know everything about the markets. In this chapter, we’ll examine the reliability of the advice of this chic group who happen to be security analysts. Breaking news in the financial media is often an analyst’s raising or lowering his or her earnings estimates of a stock or industry. Upgrades or downgrades are listened to carefully, even when we don’t know a company’s name or industry. Changes in analysts’ estimates on major companies are showstoppers that freeze people in their tracks. If the downgrade or upgrade is major, it can move the stock and its industry noticeably.

The people whom the media cover so attentively consider themselves to be hardheaded realists, not pointy-headed theoreticians. They’re immersed in the reality of daily market action, not writing math equations and running computer simulations, and they are confident that they are offering analytically tried-and-true expert advice to investors. Fair enough. Let’s put them to the test and track their actual performance. Their estimates and recommendations are the crucial factor the majority of investors look at when deciding what stocks to buy, hold, or sell. It’s time for us to analyze if CNBC, Bloomberg, or other media are giving us any more consistently accurate information than the Weather Channel.

Although they don’t agree on many issues, Wall Streeters and financial academics concur that company earnings are the major determinants of stock prices. Modern security analysis centers on predicting stock movements from precise earnings estimates. As a result, major brokerage houses still have eight-figure research budgets and hire top analysts to provide accurate estimates. The largest bank trust departments, mutual funds, hedge funds, and money managers demand the “best” because of the hundreds of millions of dollars in commissions they command.

Several decades ago, Institutional Investor magazine formalized the process of determining the “best” analysts. Each year the magazine selects an “All-Star” team made up of the “top” analysts in all the important industries—biotech, computers, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals—after polling hundreds of financial institutions. There are first, second, and third teams, as well as runners-up for each industry. The magazine portrays the team on its cover each year, often dressed in football uniforms with the brokerage firm’s name on each star’s jersey. The competition to make the teams is fierce, as we’ll see later in this chapter.

If a brokerage firm can boast a number of All-Stars, its profitability ratchets up accordingly. Some years back, the managing partners and the director of research of a large brokerage house decided to let one of their analysts go. The office executioner was on his way to inform the analyst when the research director came running down the corridor, grabbed his arm, and, gasping for breath, said, “Wait . . . we can’t do it . . . he just made the second team.”

Salary scales, as you may guess, are in the stratosphere. Experienced analysts make between $700,000 and $800,000 a year; standouts receive more. Then there is the million-dollar-a-year club, which includes several dozen of the Street’s outstanding oracles. Incomewise, they are in a class with popular entertainers and professional athletes.

Some analysts earn in the eight figures, exceeding the pay of a number of CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. Jack Grubman, the once highly regarded telecommunications analyst, jumped ship from PaineWebber to Salomon Brothers in the mid-1990s. The price was a two-year contract with annual pay of $2.5 million. The salary was so high that his research colleagues jokingly referred to underwritings of the firm being offered to its clients in “Grubman units” of $2.5 million each. Needless to say, Wall Streeters often accord top analysts the same hero worship that teenagers reserve for rock stars and film heroes.

The hero worship diminished sometime after the dot-com collapse in 2002, when SEC and state investigations of major analysts produced disturbing results. In late April 2003, the SEC and New York State regulators released thousands of documents that showed that the traditional rules of the Street had been violated, and the “Chinese Walls” supposedly keeping bankers from influencing the work of security analysts came tumbling down. Although the investigations focused on two of Wall Street’s most highly paid and powerful analysts, Jack Grubman of Salomon Smith Barney*45 and Henry Blodget of Merrill Lynch, it rapidly expanded to many dozens of other analysts. E-mails and other documents showed that many analysts had been pressured into giving favorable ratings to weak companies, a good number of which were wobbly Internet firms with almost no business plans, revenues, or viable platforms. Because underwriting IPOs had become so profitable during the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s, the pressure to serve major corporate clients rather than retail clients was overwhelming. In the mad scramble to bring in billions of dollars of investment banking fees from IPOs, analysts spoke in double-talk. Publicly they heaped praise on shaky companies they followed, rating them as strong or even “screaming” buys. In e-mails to investment banking clients they mocked the same firms, calling them “pigs,” “junk,” “crap,” and much worse. A distinct pecking order existed. Retail clients were encouraged by the analyst to buy these poor-quality issues, often at a substantial premium from where they were issued, while institutional investors were sometimes tipped off to stay well clear. Henry Blodget had a buy recommendation out on GoTo, a dot-com stock. When an institutional heavy hitter asked him what he liked about the company, Blodget flippantly replied that there was “nuthin” interesting about the issue except for the large investment banking fees Merrill was getting.1 Bad as it was, this game was only penny ante for some of the more serious analysts.

Jack Grubman was among the masters. Grubman was always negative on AT&T, but Citigroup CEO Sandy Weill “asked” him to take a fresh look at his rating of the company, which he had previously never recommended. “Asked,” in this case, implied funneling millions of extra bonus dollars to Grubman if he went along. Rumor at the time had it that AT&T’s chairman would not let Citigroup participate in a major forthcoming underwriting unless Grubman, who carried enormous weight in the communications sector, upgraded the stock. Grubman, under Weill’s watchful eye, upgraded the stock to a buy near its peak in 1999. Shortly thereafter, Citigroup earned $63 million in underwriting fees when AT&T spun off its wireless unit.

By 2002, all this had changed. Mom-and-pop investors were being clobbered on WorldCom and other telecom stocks that Grubman insisted on rating highly as markets collapsed. Suspicion rose that he was aiding Citigroup’s investment banking efforts, particularly with the scandal-ridden WorldCom, which generated very large investment banking fees as it continued a major acquisition program. Citigroup was estimated to have made $1 billion in fees generated by Grubman from its investment banking subsidiaries, while shareholders lost $2 trillion in the telecom scandal alone.2

(Grubman resigned under suspicion in August 2002. He received $30 million in severance pay from Citigroup’s brokerage subsidiary, and by mutual agreement, Citi continued to pay his legal bills.)

In the ensuing settlement with Eliot Spitzer, the New York State attorney general, Citigroup and ten other banks settled charges of conflicts of interest for $1.4 billion. Four hundred million dollars of that amount came from Citigroup. In a separate settlement with Spitzer and the SEC, Grubman was banned from the securities business for life, as was Henry Blodget. Ironically—or perhaps not—almost all of the surviving brokerage and investment banking firms were bailed out by TARP in 2008 with taxpayer funds that came in part from retail investors including, by then, the struggling “moms and pops” who bought the bad analysts’ recommendations.

It’s amazing how quickly we forget. By the mid-2000s, our trust in analysts’ forecasting abilities had been completely restored. Needless to say, “the elite,” selected by Institutional Investor from over 15,000 analysts across the country, are sensational stock pickers.

Aren’t they?

Financial World measured the analysts’ results some years back.3 The article stated, “It was not an easy task. Most brokerage houses were reluctant to release the batting averages of their superstars.”4 In many cases, the results were obtained from outside sources, such as major clients, and then “only grudgingly.” After months of digging, the magazine came up with the recommendations of twenty superstars. The conclusion: “Heroes were few and far between—during the period in question, the market rose 14.1%. If you had purchased or sold 132 stocks they recommended when they told you to, your gain would have been only 9.3%,” some 34 percent worse than selecting stocks by flipping coins. The magazine added, “Of the hundred and thirty-two stocks the superstars recommended, only 42, or just 1/3, beat the S&P 500.” A large institutional buyer of research summed it up: “In hot markets the analysts . . . get brave at just the wrong time and cautious just at the wrong time. It’s uncanny when they say one thing and start doing the opposite.”5

In addition to superstars, professional investors rely on earnings forecasting services such as I/B/E/S, Zacks, Investment Research, and First Call, which have online features that give the pros instant revisions of estimates. First Call provides a service that also gives money managers, as well as competing analysts, all analysts’ reports immediately upon their release. Many of the reports deal with forecast changes. More than 1,000 companies are covered.

The requirement for precise earnings estimates has been increasing in recent years. Missing the analysts’ estimates by pennies can send a stock’s price down sharply. Better-than-expected earnings can send prices soaring. How good, then, are the estimates? We’ve already seen that the performance of the Institutional Investor’s “All-Stars” has been anything but inspiring. But that was for only a one-year period. Nobody’s perfect, after all. Was it just a onetime slip? A fluke? Or do we see a black swan gliding slowly across the waters toward us? This answer will be important to the investment strategies considered in the chapters ahead.

Updating the work in The New Contrarian Investment Strategy, as well as a number of articles in Forbes and elsewhere,6 I did a study in collaboration with Michael Berry of James Madison University on analysts’ surprises—how much their forecasts missed actual earnings forecasts—that was published in Financial Analysts Journal in May–June 1995.7 It examined brokerage analysts’ quarterly forecasts of earnings as compared with earnings actually reported between 1973 and 1991, which I subsequently updated to 2010. Estimates for the quarter were almost always made in the previous three months, and analysts could revise their estimates up to two weeks before the end of the quarter. In all, 216,576 consensus forecasts8 were used, and we required at least four separate analysts’ estimates before including a stock in the study.9 Larger companies, such as Microsoft or Apple, might have as many as thirty or forty estimates. More than 1,500 New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, and AMEX companies were included, and on average, there were about 1,000 companies in the sample. The study was, to my knowledge, the most comprehensive on analyst forecasting to date.10

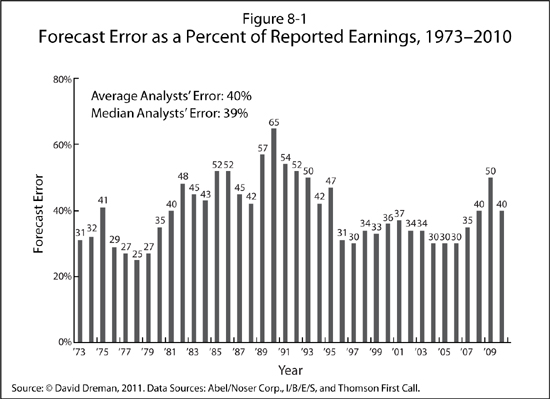

How do analysts do at this game, where even slight errors can result in instant wipeouts? A glance at Figure 8-1 tells all. The results are startling: analysts’ estimates were sharply and consistently off the mark, even though they were made less than three months before the end of the quarter for which actual earnings were reported. The average error for the sample was a whopping 40 percent annually. Again, this was no small sample; it included more than 800,000 individual analysts’ estimates.

Interestingly, these large errors are occurring in the midst of the information revolution. Yet in spite of this fact, estimated errors remain enormously high—much too high to be of any use in determining the real value of most stocks. Yes, the margin of error simply swamps any chance of accurately determining earnings!

Since many market professionals believe that a forecast error of even plus or minus 3 percent is large enough to trigger a major price movement, what did an average miss of 54 percent in 1991 or an average error of 40 percent over the past thirty-eight years do? When we look at sharp price drops on sizzling stocks after analysts’ misses of only a few percent, it becomes apparent that even small estimate errors can be dangerous to your investment health. Yet that is precisely how the game is played on the Street by analysts, large mutual funds, pension funds, and other institutional investors, and swallowed by average investors.

You might wonder whether the results are skewed by a few large errors. To check for that kind of skew, we measured earnings surprises four different ways.11 In all cases, errors were high. What about surprises from companies that report small or nominal earnings? A miss of the same amount would obviously result in a higher percentage error for companies reporting very small earnings per share compared to those reporting much higher earnings per share. If, for example, the estimate was $1.00 and the company actually reported 93 cents, the miss would be 7.5 percent. But if the estimate was 10 cents and the company reported only 3 cents, the miss would be 233 percent.*46

No matter how we analyzed it, the slightest error in the earnings forecast had a disproportionate effect on the fortunes of a company’s stock, irrespective of other measures of the company’s soundness or management performance.

I’m sure that many readers know only too well what happens when a stock misses the consensus forecast by much. E*Trade, a former dot-com favorite, tumbled 42 percent in late April 2009, when earnings came in a little more than 4 percent below estimates. Akomai Technologies dropped 19 percent in July 2009, when earnings came in 2 percent below forecast. Symantec fell 14 percent in July 2009, when reported earnings were 4 percent under estimates. But this was not a one-way street; Amazon.com rose 33 percent in October 2009, when earnings came in 36 percent above forecast. All this occurred in a market that went up over 20 percent that year.

Earnings surprises, as you would suspect, have had a major impact on stocks over time. During the Internet bubble, 3Com tumbled 45 percent when analysts’ forecasts missed reported earnings by a scant 1 percent in 1997. Sun Microsystems dropped 30 percent on a 6 percent shortfall. On May 30, 1997, Intel announced that its earnings for the June quarter would be sharply higher than in the corresponding 1996 quarter; however, they would be below the analysts’ consensus forecast by 3 percent. This caused a price drop of 26 points, or 16 percent, on the opening, which reverberated first through technology stocks and then through the market as a whole. The result was that the S&P 500 lost $87 billion in minutes. People who relied on the estimates got clobbered—to say the least.

Again, one must ask if there are exceptions. How good is this dedicated and hardworking group at its members’ vocation? As we just saw, earnings surprises of even a few percentage points can trigger major price reactions. Current investment practice demands estimates that are very close to—or dead-on—reported results. Normally, the higher the valuation of a stock, the more important the precision is. As noted, Street-smart pros normally expect reported earnings to be within a 3 percent range of the consensus estimate—and many demand better.

Is this doable? Look at Figure 8-2. We used our large database of 216,576 consensus estimates. To utilize a stock, we required at least four analysts’ estimates on it, bringing the total to 866,000 individual estimates at a minimum. Since a large number of stocks have more estimates—Apple, for example, has forty—I estimate that the total number of analysts participating in the estimates was well over one million for the thirty-eight years to the end of 2010.

Figure 8-2 summarizes our findings. We gave the analysts more leeway than most give themselves, widening the forecasting range from 3 percent to 5 percent to consider an estimate a miss. Even so, the results are devastating to believers in precise forecasts. The distribution of estimates clearly refutes their value to investors. Less than 30 percent of estimates were in the plus or minus 5 percent range of reported earnings that most pros deem absolutely essential. Using the plus or minus 10 percent error band, which many professional investors would argue is far too large, we found that only 47 percent of the consensus forecasts could be called accurate in the quarter. More than 53 percent missed this more lenient minimum range. Worse yet, only 58 percent of the consensus forecasts were within the plus or minus 15 percent band—a level that almost all Wall Streeters would call too high for any quarter.

Of what value are estimates that seriously miss the mark more than 50 percent or 70 percent of the time? After the horror stories precipitated when forecasts were off even minutely, the answer seems to be—not much. We have seen that estimates carefully prepared only three months in advance, by well-paid and diligent analysts, are notoriously inaccurate. To complicate matters, many stocks sell not on today’s earnings but on expected earnings years into the future. The analysts’ chances of being on the money with their forecasts are not much higher than the chance of winning a major trifecta. Current investment practices seem to demand a precision that is impossible to deliver. Putting your money on these estimates means you are making a bet with the odds heavily against you. A Psychological Guideline is in order here.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 11: The probability of achieving precise earnings estimates over time is minuscule. Do not use them as the major reason to buy or sell a stock.

“But maybe there’s a reason for this,” believers in their forecasting prowess might argue. “Analysts may not be able to hit the broad side of a barn overall, but that’s because there are a lot of volatile industries out there that are impossible to forecast accurately. You can make good estimates where it counts, in stable, growing industries where appreciation is almost inevitable.”

That’s a plausible statement. We fed it into our computer, which digested the database and spat out the answer a few minutes later. We divided the same analysts’ consensus estimates into twenty-four industry groups*47 and then measured the accuracy for each. The results are shown in Table 8-1. The industry error rates were smaller than those for forecasting individual companies but still almost six times as high as the 5 percent accuracy level most analysts consider too lenient. The average error was 28 percent and the median 26 percent. We also found that over the entire time period, almost 40 percent of all industries had analyst forecast errors larger than 30 percent annually, while almost 10 percent of industries showed surprises larger than 40 percent.

As the chart shows, analysts’ errors occurred indiscriminately across industries. Errors are almost as high for industries that are supposed to have clearly definable prospects, or “visibility,” years into the future, such as computers or pharmaceuticals, as they are for industries where the outlooks are considered murky, such as autos or materials. This result is so consistent that we should call it a Psychological Guideline.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 12: There are no highly predictable industries in which you can count on analysts’ forecasts. Relying on their estimates will lead to trouble.

The high-visibility, high-growth industries have as many errors as the others. The fact that analysts miss the mark consistently in supposedly high-visibility industries—and give much higher valuations—suggests that those industries are often overpriced.

Finally, let’s settle one remaining item of business regarding analysts’ forecasts. Are they less accurate in a boom period or a recession, when earnings are presumably more difficult to calculate? Could this difference be a possible reason why their forecasts are not any better?

Our 1973–2010 study covered seven periods of business expansion and six periods of recession. If you think about it, you might expect to see analysts’ forecasts too high in periods of recession, because earnings are dropping sharply, owing to economic factors that are impossible for analysts to predict. Conversely, in periods of expansion, estimates might be too low, as business is actually much better than economists and company managements anticipate. This certainly seems plausible and at first glance provides a partial explanation for the battered analysts’ records. Unfortunately, it just ain’t so, as Table 8-2 shows.

The table is broken into three columns: All Surprises, which is the average of all positive and negative surprises through the study; Positive Surprises; and Negative Surprises.12 The surprises are shown for each period of business expansion or recession. The bottom row shows the average of all consensus forecasts for periods of both expansion and recession. The average surprise for expansionary periods, 39.2 percent, is little different from the average surprise through the entire period, 39.3 percent, or the average surprise of 43.9 percent in recessionary periods. Moreover, the averages of positive surprises in expansions and recessions are also very similar, 23.3 percent versus 26.0 percent, as are negative surprises, –66.0 percent versus –70.0 percent.

The statistical analysis demonstrates that economic conditions do not seem to magnify analysts’ errors. They are about as frequent in periods of expansion or recession as they are at other times. What did come out clearly is that analysts are always optimistic; their forecasts are too optimistic in periods of recession, and this optimism doesn’t decrease in periods of economic recovery or in more normal times. This last finding is not new. A number of research papers have been devoted to the subject of analyst optimism, as chapter 7 showed, and, with the exception of one that used far too short a period of time, all have come up with the same conclusion.13 This is an important finding for the investor: if analysts are generally optimistic, there will be a large number of disappointments created not by events but by initially seeing the company or industry through rose-colored glasses, as we saw in chapter 7.

We have found that large analyst forecast errors have been unacceptably high for a very long time. An error rate of 40 percent is frightful—much too high to be used by money managers or individual investors for selecting stocks. Remember, stock pickers believe they can fine-tune estimates well within a 3 percent range. But the studies show that the average error is more than thirteen times this size. Error rates of 10 to 15 percent make it impossible to distinguish growth stocks (with earnings increasing at a 20 percent clip) from average companies (with earnings growth of 7 percent) or even from also-rans (with earnings expanding at 4 percent). What, then, do error rates approaching 40 percent do?

Dropping companies with small earnings per share to avoid large percentage errors does not eliminate the problem; the error rate is still over 20 percent. Worse yet, analysts often err. Figure 8-2 showed that only 30 percent of consensus analysts’ estimates fell within the 5 percent range of reported earnings. Remember, too, that many analysts think this range is too wide. Missing the 5 percent range would spell big trouble for stock pickers relying on precision estimates.

Unfortunately, the problems do not end here. Forecasting by industry was just as bad; the current studies to 2010 (and an earlier study between 1973 and 1996; see footnote, page 195) showed error rates almost indistinguishable between industries with supposedly excellent visibility, for which investors pay top dollar, and those considered to have dull prospects. If earnings estimates are not precise enough to weed out the also-rans from the real growth stocks, the question naturally arises why anyone would pay enormous premiums for “high-visibility” companies.

Finally, we have seen two additional problems with analysts’ forecasts. First, the error rates are not due to the business cycle. Analysts’ forecast errors are high in all stages of the cycle. Second, and more important, analysts have a strong optimistic bias in their forecasts. Not only are their errors high, but there is a consistent tendency to overestimate earnings. This is deadly when you pay a premium price for a stock. The towering forecast errors combined with analysts’ optimism result in a high probability of disaster. As we saw, even a slight “miss” for stocks with supposedly excellent visibility has unleashed waves of selling, taking the prices down five or even ten times the percentage miss of the forecasting error itself.

The size and frequency of the forecasting errors call into question many important methods of choosing stocks that rely on finely tuned estimates running years into the future. Yet accurate earnings estimates are essential to most of the stock valuation methods we looked at in chapter 2. The intrinsic value theory, formulated by John Burr Williams, is based on forecasting earnings, cash flow, or dividends, often two decades or more ahead. The growth and momentum schools of investing also require finely calibrated, precise estimates many years into the future to justify the prices they pay for stocks. The higher the multiple, the greater the visibility of earnings demanded.

If the average forecast error is 40 percent annually, the chance of hitting a bull’s-eye on an estimate ten years out seems extremely slim. Two important questions might be asked at this point. The first is whether efficient-market theorists and androidlike analysis keep prices where they should be by flawlessly processing key information accurately. The charts just presented indicate that the information input by analysts to make their estimates is anything but correctly processed. Given the results we’ve viewed, if serious errors are repeatedly made with the vital analytical inputs, what keeps markets efficient? Second, analysts do not learn from their errors, as we’ve seen for periods exceeding thirty years. Rational investors should adjust almost immediately to keep markets efficient. Why is this not done? Unfortunatley, a gaggle of black swans has landed in this chapter, detailing forecast errors that once again must be labeled “anomalies” to protect EMH. Which brings us to another Psychological Guideline.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 13: Most current security analysis requires a precision in analysts’ estimates that is impossible to provide. Avoid methods that demand this level of accuracy.

What can we make of these results? If the evidence is so strong, why aren’t more investors, particularly the pros, aware of it, and why don’t they incorporate it into their methods, rather than quick-marching into an ambush? Why do Wall Streeters blithely overlook these findings as mere curiosities—simple statistics that affect others but not them? Many pros believe that their own analysis is different—that they themselves will hit the mark time and again with pinpoint accuracy. If they happen to miss, why, it was a simple slip, or else the company misled them. More thorough research would have prevented the error. It won’t happen again.

Let’s examine why this mentality is prevalent in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It should be an interesting drama in several acts. The show has a terrific cast of experts from many fields, the action is compelling, and there’s a heartwarming (perhaps make that “portfolio-warming”) lesson for the audience.

As we just saw, investors either ignore or are not impressed by the statistical destruction of forecasting, even though the devastation has been thorough and spans decades. There are a number of reasons, some economic, some psychological, why investors who depend on finely calibrated forecasts are likely to end up with egg on their face. Two academics, John Cragg and Burton Malkiel (the latter of whom we met briefly in chapter 6), did an early analysis of long-term estimates, published in the Journal of Finance.14 They examined the earnings projections of groups of security analysts at four highly respected investment organizations, including two New York City banks’ trust departments, a mutual fund, and an investment advisory firm. These organizations made one- to five-year estimates for 185 companies. The researchers found that most analysts’ estimates were simply linear extrapolations of current trends with low correlations between actual and predicted earnings.

Despite the vast amount of additional information now available to analysts, say Cragg and Malkiel, and their frequent company visits, estimates are still projected as a continuation of past trends. “The remarkable conclusion of the present study is that the careful estimates of security analysts . . . performed little better than those of past company growth rates.”

The researchers found that analysts could have done better with their five-year estimates by simply assuming that earnings would continue to expand near the long-term rate of 4 percent annually.15

Yet another important research finding indicates the fallibility of relying on earnings forecasts. Oxford Professor Ian Little, in a 1962 paper appropriately titled “Higgledy Piggledy Growth,” revealed that the future of a large number of British companies could not be predicted from recent earnings trends.16 Little’s work proved uncomfortable to both EMH theoreticians and EMH practitioners, who promptly criticized its methodology. Little good-naturedly accepted the criticism and carefully redid the work, but the outcome was the same: earnings appeared to follow a random walk of their own, with past and future rates showing virtually no correlation, and recent trends (so important to security analysis in projecting earnings) provided no indication of the future course.17

A number of studies reach the same conclusion:18 changes in the earnings of U.S. companies fluctuate randomly over time.

Richard Brealey, for example, examined the percentage changes of earnings of 711 U.S. industrial companies between 1945 and 1964. He, too, found that trends were not sustained but actually demonstrated a slight tendency toward reversal. The only exception was companies with the steadiest rates of earnings growth, and even their correlations were only mildly positive.19

Juxtaposing the second set of studies with the first provides part of the explanation of why analysts’ forecasting errors are so high. If analysts extrapolate past earnings trends into the future, as Cragg and Malkiel have shown, and earnings do follow a random walk, as Little and Brealey demonstrated, one would expect sizable errors. And large forecast errors are what we have found consistently.

Thus, once again and from quite another tack, we see the precariousness of attempting to place major emphasis on earnings forecasts. Which calls for another Psychological Guideline:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 14: It is impossible, in a dynamic economy with continually changing political, economic, industrial, and competitive conditions, to use the past to estimate the future.

There are several other economic reasons that can cause earnings forecasts to be off base. One is what the Harvard economist Richard Zeckhauser calls “the big bath theory.” In a paper that he wrote with Jay Patel of Boston University and François Degeorge of the HEC School of Management in Paris, the researchers provided evidence that many companies try to manage earnings by attempting to show consistent, gradual improvements.20 Analysts have an appetite for steady growth, and that is what management tries to serve up. When the managers can’t do it, they take a “big bath,” writing off everything they can, perhaps even more than is necessary (accounting again), in order to produce a steady progression of earnings after the bath. The big bath could be another unpredictable effect that throws analysts’ forecasts off.

Reviewing the evidence makes it appear that forecasting is far more art than science and, like the creative fields, has few masters. Apart from highly talented exceptions, people simply cannot predict the future with any reliability, as the figures starkly tell us.

BEHAVIORAL FINANCE: CAREER PRESSURES ON ANALYSTS’ RECOMMENDATIONS

There are some substantive factors that affect analysts directly, the most important being career pressures (behavioral finance labels this as a part of agency theory*48). These can result in forecasts that stray markedly. After surveying the major brokerage houses some years back, John Dorfman, then editor of the market section of The Wall Street Journal, whom we met earlier, provided a list of what determines an analyst’s bonus, normally a substantial part of his or her salary.21 In Dorfman’s words, “Investors might be surprised by what doesn’t go into calculating analysts’ bonuses. Accuracy of profit estimates? That’s almost never a direct factor. . . . Performance of stocks that the analyst likes or hates? . . . It is rarely given major weight.” The ranking of seven factors determining an analyst’s compensation places “accuracy of forecasts” dead last.

What is most important is how the analyst is rated by the brokerage firm’s sales force. That was precisely the same pressure on analysts seen earlier during the Internet bubble, which led many into a serious conflict of interest with part of their clientele.

Many firms conduct a formal poll of the sales force, which ranks the analysts primarily on how much commission business they can drum up. At Raymond James, the sales force’s ratings accounted for 50 percent of the analysts’ bonuses. Top executives also review a printout of how much business is done in the analysts’ stocks. The report is called “stock done” for short. PaineWebber*49 kept careful records of what percentage of trades it handled in every stock, and its market share in stocks it provides research for compared with market share of competitors. Michael Culp, then the director of Prudential Securities,*50 instituted a rule requiring his analysts to make 110 contacts a month—but, he added quickly, most of his analysts were not affected, because they were already making 135. Another firm ranks analysts’ recommendations when calculating their bonuses. A buy recommendation is worth 130 points, a sell recommendation only 60, because sell recommendations don’t generate nearly as much business as buy recommendations; no points are added for accuracy.22 We also have seen where this road led in the earlier section on the marketing of dot-com stocks.

Making the Institutional Investor All-Star Team, according to The Wall Street Journal list, ranks second. Having an analyst on “the Team,” as we’ve seen, results in big commissions for the firm. Even as he denied the importance of the Institutional Investor poll, one research director said, “Most of the guys know they’ll be visiting for I-I in the spring.” That is, the analyst will be making the annual pilgrimage to visit institutional clients, implicitly lobbying for their vote to fame and fortune. “I’m a lonely guy in March and April, shortly before the balloting,” he continued.

Do you find these remarks disturbing? The analysts’ behavior is certainly better than it was during the dot-com bubble, but the temptations not to put out sell reports and the rewards for putting out as many buy recommendations as possible are high. Most investors directly or indirectly put their savings into the hands of research analysts whose forecasts are the cornerstones of their recommendations. But the forecasts are a trivial factor or even a nonevent in determining their compensation. Unfortunately, that’s always been the name of the game. The key question for the investor is whether an analyst is giving you his best recommendations or, given his compensation, which is based upon maximizing his commissions generated, recommending what is likely to sell the most. Obviously, this is impossible to pinpoint. But there is a good Psychological Guideline that will help:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 15: If you’re interested in an analyst’s recommendation, get all of his reports for at least the last three to five years and see how they’ve done. If they haven’t done well or he can’t provide them, move on.

There are yet other direct pressures on analysts. An important one, well known on the Street, is the fear of issuing sell recommendations. Sell recommendations are only a small fraction of the buys. A company that the analyst issues a sell recommendation on will often ban him from further contact. If he issues a sell recommendation on the entire industry, he may receive an industry blackball, which virtually excludes him from talking to any important executives. If the analyst is an expert in the industry and it represents the main part of his intellectual property, he is facing major career damage by pressing the sell button.

Recommending a sell, even when the analyst proves to be dead-on, can be costly. In the late 1980s, an analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott issued a sell recommendation on one of the Atlantic City casinos owned by Donald Trump. Trump went bananas and insisted that the analyst be fired for his lack of knowledge. Shortly thereafter, he was fired—but naturally, said the brokerage firm, “for other reasons.” The analyst proved right, and the casino went into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Out of a job, he won the equivalent of a few years’ salary from an arbitration panel. But he was never rewarded for his excellent call and, in fact, suffered because of it.

Another analyst was banned from an analysts’ meeting of the then high-flying Boston Chicken (later named Boston Market). His offense: he had issued a sell recommendation on the company. “We don’t want you here,” Boston Chicken’s CFO told him. “We don’t want you to confuse yourself with the facts.”23 The facts were that Boston Chicken filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy not long afterward. A number of studies indicate that analysts issue five or six times as many buy as sell recommendations.24 Obviously, career pressures have an impact on the buy-sell-hold rating.

Many companies retaliate when analysts write negative reports on them. The retribution can take many forms. One analyst at Prudential Securities wrote a number of negative reports about Citicorp in 1992. Frustrated that Prudential could not become the lead underwriter in some asset-backed bond deals, a Prudential investment banker went to Citicorp and was told that the reason was the analyst. The same analyst, a year later, criticized Banc One and its complex derivative holdings, which eventually cost it hundreds of millions of dollars in write-offs. Banc One stopped its bond trading with Prudential. By coincidence, the analyst left the firm shortly thereafter. At Kidder Peabody an analyst repeatedly recommended the sale of NationsBank (now Bank of America). The bank stopped all stock and bond trading for its trust accounts with Kidder.25

For analysts at brokerage firms that are also large underwriters, the pressure is even greater. Negative reports are a major no-no. Bell South officials were unhappy about the comments of a Salomon Brothers analyst who stated that its management was inefficient and ranked it sixth out of the seven regional Bells. Salomon, the bond powerhouse, was excluded from the lucrative lead-manager role in a large Bell South issue. In late 1994, Conseco fired Merrill Lynch as its lead underwriter in a big bond offering shortly after its analyst downgraded Conseco’s stock. Smith Barney, according to sources, believes it lost a chance to be part of the underwriting group of Owens-Corning Fiberglas after one of its analysts wrote a negative report on the company.26

Just how heavy career pressures can be for analysts working for major underwriting firms if they recommend a sale is shown in an academic study. The work examined 250 analyst reports from investment banking houses, matching them up with 250 from brokerage firms that did not conduct investment banking. The conclusion: investment banking house brokers issued 25 percent more buy recommendations and a remarkable 46 percent fewer sell recommendations.27

What is apparent from the above circumstances and those we saw earlier is that an analyst’s most important responsibility is to be a good marketer of the brokerage firm. The analyst must tell a good story, not one that is necessarily right. The bottom line is commissions. A good marketer and a good forecaster are different animals. We have already seen one example of the “All-Stars” significantly underperforming the market with their picks. Another example is that major money managers, to whom the All-Stars devote the bulk of their attention, consistently do worse than the averages.

Analysts of necessity use disingenuous gradations that actually mean sell, such as underweight, lighten up, fully valued, overvalued, source of funds, swap and hold, or even strong hold. Peter Siris, a former analyst at UBS Securities, summed it up well several decades ago: “There’s a game out there. Most people aren’t fooled by what analysts have to say . . . because they know in a lot of cases they’re shills. But those poor [small] investors—somebody ought to tell them.”28 You’ve been warned!

Even if brokerage firms don’t focus on accurate estimates, however, analysts are not punished for producing them. And although firms may be pressured by their underwriting clients not to make sell recommendations on their stocks, to my knowledge an analyst has never been reprimanded for writing a highly optimistic report on them.

In the preceding chapter, we saw that expert forecasts were sharply off the mark in many fields besides the stock market. Within the market, the analyst traveling with a laptop can run spreadsheets, check stock quotes, receive faxes, even tap into voluminous databases. At home base, his data input capabilities increase enormously. As one Morgan analyst stated, extracting useful information from the forty-nine databases the bank subscribes to is like finding a needle in a haystack. “The more data you get, the less information you have,” he groaned.29 His intuition coincides with the psychological findings. Increased information, as was demonstrated, does not lead to increased accuracy. A large number of studies in cognitive psychology indicate that human judgment is often predictably incorrect. Nor is overconfidence unique to analysts. People in situations of uncertainty are generally overconfident on the basis of the information available to them; they usually believe they are right much more often than they are.

These findings apply to many other fields. A classic analysis of cognitive psychologists found that it was impossible to predict which psychologists would be good diagnosticians. Further, there were no mechanical forecasting models that could be continuously used to improve judgment. The study concluded that the only way to resolve the problem was to look at the record of the diagnostician over a substantial period of time.

Researchers have also shown that people can maintain a high degree of confidence in their answers, even when they know the “hit rate” is not very high. The phenomenon has been called the “illusion of validity,” as noted before briefly.30 This also helps explain the belief that analysts can pinpoint their estimates despite the strong evidence to the contrary. People make confident predictions from incomplete and fallible data. There are excellent lessons here for the stock forecaster.

Daniel Kahneman, who for several decades was a coauthor of many important scholarly pieces with Amos Tversky, wrote on this subject in collaboration with Dan Lovallo.31

Forecasters are “excessively prone” to treating each problem as unique, paying no attention to history. Cognitive psychologists note that there are two distinct methods of forecasting. The first is called the “inside view.” This method is the one overwhelmingly used to forecast earnings estimates and stock prices. The analyst or stock forecaster focuses entirely on the stock and related aspects such as growth rates, market share, product development, the general market, the economic outlook, and a host of other variables.

The “outside view,” on the other hand, ignores the multitude of factors that go into making the individual forecast and focuses instead on the group of cases believed to be most similar. In the case of earnings estimates, for example, it would zero in on how accurate earnings forecasts have been overall or how accurate they have been for a specific industry or for the company itself in deciding how precisely the analyst can estimate and the reliance that can be placed on the forecast.

If stock market forecasters are to succeed using the inside view, they must capture the critical elements of the future. The outside view, in contrast, is essentially statistical and comparative and does not attempt to read the future in any detail.

Kahneman relates a story to demonstrate the difference. In the mid-1970s, he was involved with a group of experts in developing a curriculum on judgment and decision making under uncertainty for high schools in Israel. When the team had been in operation for a year and had made some significant progress, discussion turned to how long it would take to complete the project. Everyone in the group, including Kahneman, gave an estimate. The forecasts ranged from eighteen to thirty months. Kahneman then asked one of his colleagues, an expert in curriculum development, to think of similar projects he was familiar with at a parallel stage in time and development. “How long did it take them from that point to complete their projects?” he asked.

After a long pause the expert replied with obvious discomfort that, first of all, about 40 percent of the projects had never been completed. Of the balance, he said, “I cannot think of any that was completed in less than seven years, nor any that took more than ten.” Kahneman then asked if there were any factors that made this team superior in attempting the task. None, said the expert. “Indeed we are slightly below average in terms of our resources and our potential.” As experienced as he was with the outside view, the curriculum development expert was just as susceptible to the inside view.*51

As is now apparent, the inside and outside views draw on dramatically different sources of information, and the processes are poles apart. The outside view ignores the innumerable details of the project on hand (the cornerstone of analysis using the inside view) and makes no attempt to forecast the outcome of the project into the future. Instead, it focuses on the statistics of projects similar to the one being undertaken to determine the odds of success or failure. The basic difference is that with the outside view, the problem is treated not as unique but as an instance of a number of similar problems. The outside view could be applied to a large number of the problems we’ve seen, including curriculum building, medical and psychiatric or legal diagnosis, and forecasting earnings or future stock prices.

According to Kahneman, “It should be obvious that when both methods are applied with intelligence and skill the outside view is much more likely to yield a realistic estimate. In general, the future of long and complex undertakings is simply not foreseeable in detail.” The number of possible outcomes when dozens or hundreds of factors interact in the marketplace is, for all practical purposes, infinite. Even if one could foresee each of the possibilities, the probability of any particular scenario is negligible. Yet this is precisely what analysts are trying to accomplish with a single, precise prediction.

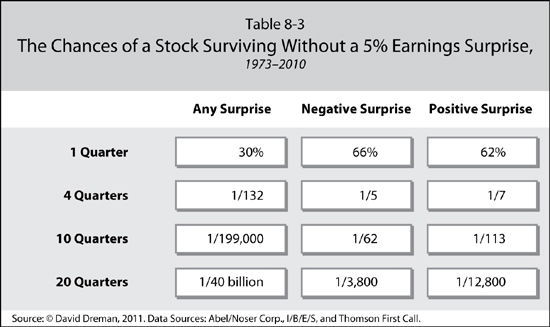

Let’s return to our analytical friends and look at their chances of success in terms of the inside view. As Table 8-3 makes clear, the probability of their being correct on their forecasts over any but the shortest periods of time is extremely low, and this means that the chances of making money consistently using precise forecasts are almost negligible.

As we saw earlier, the Street demands forecasts normally within a range of plus or minus 3 percent. Table 8-3, taken from our previous analysts’ forecasting study, shows how slim the probability of getting estimates within even the wider 5 percent range actually is. Remember, only 30 percent of forecasts made this target in any one quarter.

The table shows the chance of an analyst’s hitting the target for one quarter, four quarters, ten quarters, and twenty quarters; for all earnings surprises in column 1, negative surprises in column 2, and positive surprises in column 3. It is not reassuring. The odds against the investor who relies on fine-tuned earnings estimates are staggering. There is only a 1-in-132 chance that the analysts’ consensus forecast will be within 5 percent for any four consecutive quarters. Going longer makes the odds dramatically worse. For any ten consecutive quarters, the odds of fine-tuning the estimates for a company within this range fall to 1 in 199,000, and for twenty consecutive quarters, they fall to 1 in 40 billion. We stopped our calculation of estimates there, as the odds would have been likely to go up to the trillions twenty years out. Yet those are exactly the forecasting techniques most good investors on the Street use—and, oh yes, what the EMH theorists say keeps the market efficient. Both are guilty of significant error: For the practitioners it is not wanting to believe the odds are so high against forecasting. For the theorists it is not having an inkling of how badly one of the chief tools of security analysis performs. The bell tolls for both groups.

To put this all into perspective, your probability of being the big winner of the New York State Lottery is more than 777 times as great as your probability of pinpointing earnings every quarter for the next five years. Few people would put a couple of bucks into a lottery against odds like those, but millions of investors will play them in the marketplace for big stakes anytime.

Some folks will say, “Who cares if earnings come in above estimates? In fact, I’ll applaud.” Fair enough. So we asked: what are the chances that you will avoid a 5 percent negative surprise for ten to twenty consecutive quarters? The answer is “Very poor.” The investor has only a 1-in-5 chance of not getting a negative earnings surprise 5 percent below the consensus forecast after only four quarters. After ten quarters, the chance of not receiving at least one crippling earnings surprise goes down to 1 in 62, and after twenty quarters, it is 1 in 3,800.

Yet, as we have also seen, forecasts often have to go out a decade or more to justify the high prices at which many growth companies are trading. If the odds are staggeringly high against being precise for five years, what are they for ten or fifteen? Many extremely pricey growth stocks must make their forecasts for ten- or fifteen-year periods in order to justify their current prices.

Think about it: should anyone not on something want to play against these odds? Yet, as we know, relying on accurate estimates is the way most people play the investment game. Investors who understand these prohibitive odds will obviously want to go with them if there is a way to do it, which is exactly what we’ll look at in the next section.

What we see here is a classic case of using the inside rather than the outside view. Evidence such as the above strongly supports Kahneman’s statement that the outside view is much more likely to yield realistic results. Yet, as Kahneman states, “The inside view is overwhelmingly preferred in forecasting.”

In the marketplace, the outside view does not give the stock investor the same confidence that he is in control and can use his expertise to power through to above-average returns. Nor does it provide much excitement or good “war stories,” which most clients like. It is used far less frequently than the inside view, although we have seen in the previous chapter that index funds, which are structured entirely on the outside view, easily beat most mutual funds over time. The superior returns from contrarian strategies also come from the outside view, as we’ll see in the next section.

Another Psychological Guideline is appropriate here:

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 16: The outside view normally provides superior returns over time. To maximize your returns, purchase investments that provide you with this approach.

Looking at the figures above, someone might ask, “Why?” The answer is again psychological. The natural way a decision maker approaches a problem is to focus all of his or her knowledge on the task, concentrating particularly on its unique features. Kahneman noted that a general observation of overconfidence is that even when forecasters are aware of findings such as the foregoing, they will still use the inside approach, disregarding the outside view, regardless of how strong its statistical documentation is.

Often, the relevance of the outside view is explicitly denied. Analysts and money managers I have talked to about high error rates repeatedly shrug them off. In sum, they ignore the record of forecasting because they have been taught and believe that investment theory, when executed properly, will yield the precise results that they require. Analysts and money managers seem unable to recognize the problems inherent in forecasting.

This situation is not unique to Wall Street. Indeed, the relevance of the statistical calculations inherent in the outside view is usually explicitly denied. Doctors and lawyers often argue against allying statistical odds to particular cases. Sometimes their preference for the inside view is couched in almost moral terms. Thus, the professional will say, “My client [or patient] is not a statistic; his case is unique.” Many disciplines implicitly teach their practitioners that the inside view is the only professional way to come to grips with the unique problems they will meet. The outside view is rejected as a crude analogy from instances that are only superficially similar.

Not to pay enormous prices for the skyrocketing earnings estimates of a company such as Google, on the cutting edge of Internet technology, many analysts would argue, is vastly unfair to current shareholders and potential buyers. Ironically, rapid technology change, accompanied by rapierlike earnings growth, makes the forecasting process even more difficult than it is for more mundane companies.

The forecasting pond is getting crowded. Let’s conclude with some recent examples in case you think that in the 2000s we turned a corner to a better understanding of the problems.

Large optimistic errors appear to be a way of life with corporate capital spending, particularly when new technologies or other projects where the firm is in an unfamiliar situation are involved. A Rand Corporation study some years back examined the cost of new types of plants in the energy field.32 The norm was that actual construction costs were double the initial estimates, and 80 percent of the projects failed to gain their projected market share.

A psychological study examining the cause of this type of failure concluded that most companies demanded a worst-case scenario for a capital spending project. “But the worst case forecasts are almost always too optimistic. When managers look at the downside, they generally describe a mildly pessimistic future rather than the worst possible future.”33

Overoptimism often results from differences in estimates made from the inside rather than the outside view. A clear-cut example is demonstrated by the behavior of large banks, investment bankers, the Federal Reserve, and the Treasury throughout the financial crisis almost until the end. As the financial system began to unravel in late 2006 and early 2007, dozens of reassuring statements were made by these large institutions that they would emerge with little damage. Those utterances were supported by Fed Chairman Bernanke, Treasury Secretary Paulson, and dozens of other senior officials.

On the outside, thousands of stories on the housing bubble and many of its excesses appeared in the media, by many astute observers, including Paul Krugman, a Nobel laureate in economics, and Gretchen Morgenson, a Pulitzer Prize winner with The New York Times, up to two years before the bubble popped. They were ignored or shrugged off by both the Fed and senior government officials.

Through 2007 and 2008, as conditions worsened, the banks and investment banks continued to be inordinately optimistic about the value of their toxic mortgage portfolios. They were substantially underreserving their losses to the spring of 2008, even though the subprime mortgage origination industry and many hedge funds had already collapsed several months before, with many dozens wiped out entirely. Only when banks and investment bankers realized their survival was at stake did reality break through, and enormous write-downs of these holdings took place. By then, of course, it was far too late.

Here is a good Psychological Guideline to train yourself to follow.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GUIDELINE 17: Be realistic about the downside of an investment; expect the worst case to be much more severe than you anticipated.

In this chapter, we have looked at the striking errors in analysts’ forecasts, errors so large that they render the majority of current investment methods inoperable. We have also seen that even though high error rates have been recognized for decades, neither analysts nor the investors who religiously depend on them have altered their methods in any way.

The problem is not unique to analysts or market forecasters. We have also seen how pervasive it is in many professions where information is hard to analyze, as well as how difficult the problem is to recognize, let alone change. Finally, we have found overoptimism to be a strong component of expert forecasts, both within and outside the stock market.

Now the question is: what can we do about it? The answer is that we need to move on to a better investing paradigm that does not rely primarily or exclusively on the efficient-market hypothesis or on the forecasts and estimates of company earnings from securities analysts. On the contrary, there is a better way.