CHAPTER 8

German Doctors Organize Data to Turn the Tables on Degeneration, 1857-1879

Most often, the disease that is transmitted is transformed.

—Henri Legrand du Saulle (1873)

A statistical refutation of the medico-cosmic theory of dégénérescence seems as promising as smashing a shadow with a sledgehammer. However, a decade after Morel’s articulation of this slippery, portentous doctrine, Wilhelm Tigges mobilized tabular data for just this purpose. Despite his statistics, a sense of intrinsic degeneration continued to develop as an international cultural movement widely appreciated by alienists, especially in France. Meanwhile, the data science of heredity gradually consolidated around methods for tracing the transmission of traits across generations. Insane heredity in France gradually separated from other parts of northern Europe and North America. Each version was, in a way, highly empirical, but the French theory of degeneration had almost no use for statistics.

In the new Germany, the great advantage of census cards was to ease the preparation of tables that could reveal causes by placing the relevant variables into a two-dimensional array. The new tabular system presumed that virtually every characteristic of asylum patients had a hereditary component. Neither Tigges, who spearheaded the effort to lighten the data demands on these institutions, nor F. W. Hagen, the most resolute skeptic of mass statistics and standardization, wanted to turn away from numbers. They struggled instead to sharpen the focus and in particular to advance from suggestive hereditary relationships to predictive calculations that could guide reproductive interventions. Such results should shed light on how the hereditary Anlage was transmitted, the role of dormancy, and what sorts of transformations were likely from one generation to the next.

The census reforms within newly unified Germany created the possibility for insanity statistics on a much larger scale. Already in the 1860s, by exploiting the growth of mental hospitals and extending reports over ever-longer periods, the tables were veering toward superabundance. Now, even without a census, uniform reporting from institutions all over Germany could turn figures in the thousands into hundreds of thousands. What was the value of so much data? Hagen held that the sacrifice of quality and of homogeneity must outweigh by far the advantages of copious records. While Tigges was more impressed by the potential advantages of large numbers, he too relied primarily on multiyear data from his own investigations. Massive new census reports on the insane tended to languish.

Institutional numbers, by contrast, had consequences. Three years before the Franco-Prussian War, just as the push for standardization was beginning to gain momentum, Tigges had ventured forth with tables from his institution to do battle with the theory of degeneration. As second physician at the Westphalian asylum in Marsberg, he prepared four hundred dense pages on its statistics, to appear beside the director’s historical essay. Heinrich Laehr had the volume sent to all AZP subscribers as a special supplement for 1867. Was it Tigges’s argument that impressed him, or the full half century of coverage, or the more than 3,000 patients, or the abundance of elaborate tables? Even true believers must have wilted in the face of so much statistical detail. Yet these tables were less conventional, and the diligence of the author still more remarkable, than at first appears. The labor of analysis was by far disproportionate to the number of pages, for Tigges almost always combined variables in order to clarify quantitative relationships. He folded results from other asylums into his tables as a basis for comparison, and he made use of new data technologies, as in his line graph of patients with and without hereditary antecedents according to age of onset.1

FIGURE 8.1. Line graph by Wilhelm Tigges comparing age distributions for first appearance of hereditary and nonhereditary insanity. A tendency toward earlier outbreak in hereditary cases could have been seen as evidence of family degeneration, but he drew no such conclusion. From Koster and Tigges, Geschichte und Statistik, 265.

Contesting Degeneration

The European preoccupation with degeneration from about 1860 to the First World War is well known to scholars.2 It is easy, however, to misunderstand the logic of its relationship to the science of heredity. Biological degeneration was already widely discussed in the eighteenth century. Much of the brouhaha of the late nineteenth century was focused on a version articulated by Morel in books he published in 1857 and 1860. His version made a great impression on alienists, especially in France, and inspired European artists, philosophers, and novelists for at least half a century. Cultural historians have found it irresistible. It did not dominate the field, however, but was challenged by medical and scientific writers on heredity right from the start. While Tigges articulated his critique in statistical terms, using new tabular arrangements, he had definite ideas about how heredity works. While he allowed for mutability, behind it lay an Anlage, whose passage from generation to generation should be traceable. Hereditary continuity was defined by similarities between ancestors and descendants.

For Morel and his followers, heredity was intrinsically a process of degenerative change within which nothing stood still. Pedigrees of degeneration—in contrast, for example, to Dahl’s—were not a tool to track the recurrences of a taint or Anlage but, as in Émile Zola’s novels, manifestations of a fateful narrative of decline. Hereditary insanity for Morel was a distinct form of illness with its own physical indications or stigmata, the “special physiognomy” of its victims.3 It played out according to a pattern across several generations, from superficial symptoms appearing intermittently or late in life to disabling, irreversible ones that often were present at birth. It combined bodily and mental decay, each reflecting a progressively deeper penetration of the disease, culminating in cretinism or idiocy and in sterility, hence extinction. However, bodily conditions and delusional thoughts were not easily reconciled in a single typology. Like so many physicians, Morel wrote and thought primarily in cases, and his were uncontrollably various. Although he stuck by his grand explanatory categories, he did not paper over the exceptions. Tigges held that so many exceptions reduced Morel’s argument to incoherence.4

Tigges and Morel shared a commitment to hereditary intervention but gave opposing rationales. Tigges thought in terms of the transmission of predispositions or Anlagen, whose presence should perhaps disqualify a victim of insanity from reproducing. Morel understood degeneration as irreducible process, a trajectory of decay that was set off by bad behavior of an ancestor, most often involving drink, and aggravated by ill-advised marriages. His advice on this topic, strangely, was utterly unoriginal. He copied it word for word from a treatise on inflammations by the pathologist and alienist Louis-Florentin Calmeil, the long-term assistant of the elder Royer-Collard at Charenton. Morel focused on marriage within families tainted by conditions such as epi.tify and idiocy, even calling for legislation to prevent them.5 Traits running in families over several generations did not figure in his analysis. In 1867, Baillarger initiated a discussion at the Medical-Psychological Society concerning what he called the most important question of heredity. What proportion of children in families with a predisposition will be affected by this taint? Some physicians in attendance dismissed the question as too vague to be meaningful. Morel’s answer pushed aside the language of predispositions and resemblances, focusing instead on the stigmata of heredity, which might be physical, moral, or intellectual.6

When, in 1876, Tigges articulated his understanding of hereditary mechanisms, he relied heavily on a German volume of commentary on Darwinian evolution. Its author, Oscar Schmidt, was a professor at the now-German university of Strassburg. Schmidt stressed that heredity by itself is neither a force for progress nor decay, but the ground of biological stability, passing on characters from parents to offspring. Biological change was the result of selection and adaptation. Tigges, welcoming this critique, accused Morel and his student Henri Legrand du Saulle of exaggerating the role of inheritance of acquired traits in a vain effort to establish a biological basis for degeneration. Heredity, he declared, can do no more than pass along Anlagen for the best-adapted traits to subsequent generations. His aims were entirely pragmatic, focusing on breeding as artificial selection with no mention of natural selection or of the origins of species. He thus reduced biological change to comparative statistics of survival and reproduction, on the assumption that like tends to reproduce like. Morel’s mechanism of degeneration might be found in a few families, he conceded, but not as a rule. Brown-Séquard’s recent experiments on guinea-pig neurology, showing medically induced epi.tify to be inherited in these creatures, must also be untypical. Darwinism, Tigges concluded, was more correct on these questions than were the theories of most alienists.7

These thoughts on heredity from 1876 appeared in a five-year report on the asylum Tigges then directed in Sachsenberg, an institution with a tradition of serious data collection going back to its first director, Carl Flemming.8 Schmidt’s Darwinian interpretations deepened his knowledge of heredity while supporting in the main what he already believed. His arguments against Morel’s degeneration were, in the first instance, statistical and, in terms of his own intellectual development, pre-Darwinian. Already in 1867, he viewed Morel’s “observations” as simultaneously slipshod and tendentious. They also were maddeningly heterogeneous, so much so that he found it hard to fix on a specific object of criticism. Why didn’t Morel mobilize his own abundant statistics as evidence for or against degeneration? One thing, however, was clear: the theory involved some inherent process of decline from generation to generation. In a nutshell, patients with hereditary mental illness must, on average, descend from ancestors with less severe conditions. These included epi.tify, mild nervous hysteria, and psychically dubious (psychisch zweifelhaft) states. This last phrase referred to odd or delusional thinking that fell short of insanity. His proud achievement was to have collected and configured data to put Morel’s doctrine to the test.

An inventory of relevant numbers appears on the four-page Table 6 of the Marsberg report, representing 532 patients whose insanity was known to be hereditary: 357 with at least one mentally ill parent, and 175 involving mental illness of a grandparent, aunt, or uncle. Tigges’s criterion for classifying a patient as hereditary was the identification of a close relative showing any mental disease, including relatively mild nerve disorders that did not require asylum treatment. Just 32 of his hereditary patients had even a single relative from the parental or grandparental generation with epi.tify. The corresponding number for relatives with nervous diseases, including imbecility and hysteria, was 107, and for psychically dubious states, 44. The great majority of his hereditary patients had relatives with full-blooded mental illness. In sum, most asylum patients were no sicker than their progenitors. He thus was entitled to doubt whether the lash of degeneration “really influences the descendants so devastatingly” as Morel claimed.9

Table 10 (see fig. 8.2), similarly, was not calculated to add luster to Morel’s theory. It involved elaborate processing of the basic patient data from Table 6 to reveal the relations of Abstammung, or descent, not to the diagnosed illness of the patients themselves, but rather to certain maladies detected in their brothers and sisters. These siblings are described individually in the Remarks column of Table 6. Did these less unhealthy persons tend to have insane children? No, the rule once again was, like parent like child, even for mild mental conditions. The columns of Table 10 identify four such conditions: Blödsinn, or imbecility; epi.tify; “psychically dubious, including drunkenness and suicide”; and other nervous complaints. None of these nervous conditions were strongly linked by heredity with true mental illness. The largest percentages appeared at the intersection of row and column for mental weakness, or Blödsinn, (12.5); the intersection for psychically dubious states (9.375); and the intersection for inherited epi.tify (7.3).10

FIGURE 8.2. Table in Koster and Tigges, Geschichte und Statistik (1867), 215, demonstrating the hereditary similarity of conditions suffered within families across generations. The main point was that hereditary patients with real mental illness only rarely came from families with less severe nerve conditions. Tigges offered the table as a refutation of Morel’s theory of degeneration.

These percentage figures were complicated, reflecting the effort required to procure data on inheritance of nerve conditions that the asylum did not treat, such as dullness and epi.tify. With a little effort, we can infer from Table 6 the actual numbers corresponding to these percentages. Just six individuals made up the 12.5% of imbecile siblings who had imbecility in their ancestry. The corresponding number for the psychically dubious was also six; and for the epileptics, just three. Since Tigges knew and even used Poisson’s formula for random error, he almost certainly realized that he was dealing with wide bands of uncertainty. Yet his calculation was not quite unprincipled. As he argued two years later in his first comment on the Lunier proposal: “The deeper we go into the study of causes, the more certain we become that consensus among statisticians and genuine advancement of knowledge will not be achieved by defining very wide groups, and still less as the groups become even larger, but instead through a precise apprehension of particular propensities and the most exact possible definition of particular groups.”11 The further advance of standardization should make it possible to achieve credible results even for highly specific conditions.

Troubling Imprecision

Although the high percentage of insanity cases involving hereditary causation was familiar to everyone, its measurement had never seemed satisfactory.12 In 1873, Legrand du Saulle cast doubt on all prior results with that most basic form of meta-analysis, a tabular list. It was headed “Numerical proportions for heredity in insanity. Per 100” and included 50 published values from almost as many institutions. The numbers ranged from 4% to 90%, and while most were below 50%, there was no discernible pattern. Legrand du Saulle, a physician at Bicêtre, believed firmly in the force of heredity, and he felt bound to explain why so many of the numbers were so low. Large public asylums are incapable of proper investigation, and too many institutions do not look beyond direct ancestors. Adultery, often unknowable, reduces these measures, and many people are unable or unwilling to identify family afflictions.13 There was also a more fundamental problem. “To understand hereditary transmission well, it is absolutely necessary to comprehend mental affections and major neuroses as varieties of a single species, taking this word ‘species’ in the sense of naturalists, that is, as a succession of organisms coming from similar parents and capable of reproducing together.” A former intern at Saint-Yon under Morel, he credited his teacher with revivifying this exhausted tradition of research by turning attention from the ancestors to the descendants and showing that insanity is a highly polymorphic dégénérescence. Without this basic fact, alienists lost all hope of reliable statistics. Earlier classifications missed the key point that words like mania and melancholia merely describe symptomatic states. “Most often, the disease that is transmitted is transformed.”14

In fact, Legrand du Saulle cared very little for statistics. Like Trélat, whom he admired, he multiplied instances of hereditary causation by always preferring it to rival explanations. The highest figure on his list, 90%, was based on an offhand remark in a book unencumbered by numerical data, La psychologie morbide by Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours, who simply had written: “As I understand it, and as I believe must generally be understood, heredity is the source of nine-tenths, perhaps, of mental diseases.”15 Following his teacher, Legrand du Saulle construed hereditary insanity as a distinct type of mental illness. His ally Gabriel Doutrebente, another veteran from Saint-Yon and the main source for his case material, had already drawn out the implications of inherited insanity for statistics. Their wild discordance, he explained, owed to a failure to include neuroses with mental illness in the ascending line as hereditary causes of mental disease in the descendants. A proper statistics of hereditary transmission would include epi.tify with insanity. Once we have understood degeneration, it becomes self-evident that heredity, though called a predisposing cause, is quite sufficient to produce insanity without the added stimulus of lost love or business failure. He, too, sounds rather like Trélat, though he allowed a modest secondary role for all the moral causes that showed up in asylum data.

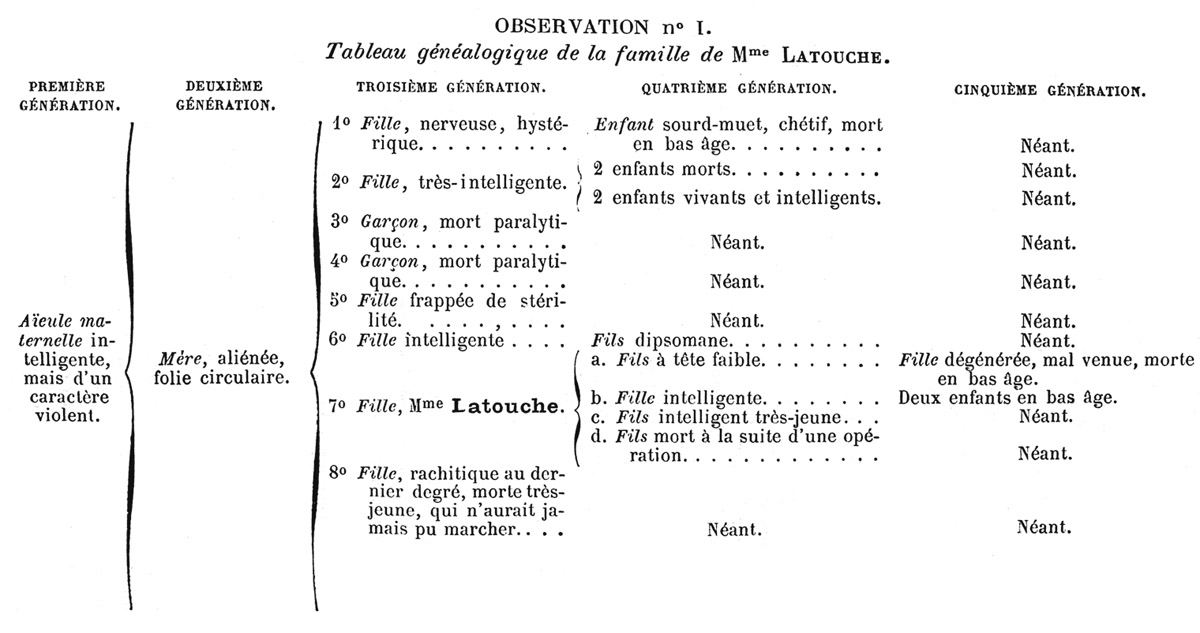

Both physical and mental indications, from strange ideas to an ill-shaped head, enabled the physician to identify a hereditary case. Doutrebente wrote admiringly of Morel’s insight in selecting Mme. Guérard for close family investigation. The master had discerned at a glance the hereditary nature of her delirium. The family, not the sick individual, was the proper unit of observation. Doutrebente composed his paper as a series of such observations, taking the form of tabular genealogies that captured Morel’s theory in a visual display. They provided a template for degeneration leading to extinction (néant). Some families survived for five generations, some only for three, but the pattern was clear enough. He received a Prix Esquirol for the work, which also was reviewed enthusiastically in the English JMS. However, the notoriety of his charts, especially in Germany, owed much to Legrand du Saulle’s use of two of them, redrawn, to illustrate his little book. Both of those families died out in exactly four generations.16

Although he provided some names, Doutrebente divulged nothing about his methods of gathering information. Opponents would claim that the theory depended on a shameless selection of families. That is probably too harsh. We may assume that he began with an institutionalized patient (here, Mme. Latouche) whose mother or father also manifested mental irregularities. In this chart, exceptionally, there is also a grandmother. Everything traces back, however, to the insane mother, located in the second generation, and the descent to extinction begins with her children. If the children of the third generation were healthy, the family would not be a candidate for inclusion. Yet the trajectory of degeneration was not quite a self-fulfilling prophecy, and in this uniquely large family, is not yet even conclusive. Several of the children here are in better shape than their diseased parent, and the progression through stages of degeneration flattens out or even turns back at some nodes. The table seems to leave open whether all grandchildren were old enough to warrant that the story has reached its end. Four grandchildren are entered on this table as intelligent, and one of these, in addition, as very young, and there are two very young children in the fifth generation. Yet a death drum of néant, the extinction of the line from failure to reproduce, distinguishes the last two generations from the third, and distinguishes, as well, these family trees of degeneration from Dahl’s pedigrees and Tigges’s multigenerational arrays.

FIGURE 8.3. Gabriel Doutrebente’s chart of degeneration and approaching extinction of the family of Madame Latouche, to be compared with the table by Tigges (fig. 8.2). The criteria of degeneration include earlier onset and greater severity of disease, implying that congenital mental weakness is more extreme than mental alienation (madness), which comes on later in life. The most decisive consequence of degeneration, however, is the failure to reproduce, which appears as a proliferation of descendants who died childless (néant). From Doutrebente, “Etude généalogique,” 213.

Legrand du Saulle’s book, which was taken very seriously, confronted German asylum doctors with a double challenge, first by alleging the incoherence of the customary measure of hereditary causation, and then by offering degeneration as the solution. For decades afterward, asylum statisticians cited this list of discrepant measures of “percent hereditary” with embarrassment. Carl Wilhelm Pelman, a Rhinelander by origin who was made head of the asylum of Stephansfeld after Alsace became German, reviewed the book for the AZP. He endorsed the French argument that hereditary insanity had been misunderstood, that it was really a distinctive form of mental illness with an unfavorable prognosis and could be recognized from certain stigmata. The book deserves many readers, he declared, and should be translated. Exploiting his binational situation, Pelman promptly commissioned an assistant to do the job.17 At the 1874 congress of German asylum doctors, he extolled the tradition of administrative statistics at Stephansfeld and commended it as a model for unified Germany.18

Data for Hereditary Prognosis

Tables of the extinction of families fit well with the loss of hope that pervaded asylum systems by the 1870s. Although Tigges did not credit Morel or his students with any useful insights, he may have been moved by Morel’s efforts to turn his attention to hereditary prediction, focusing, as Legrand du Saulle had put it, on the descendants instead of the ancestors. He probably noticed a paper in 1869 in the AZP by Richard von Krafft-Ebing, fresh from an apprenticeship with Christian Roller in Baden, lauding Morel’s disease category of degenerative insanity as a new basis for family prognoses.19 Asylum doctors often cited data on heredity to explain the irrepressible increase of insanity, an issue of great interest also to Tigges. The time had come to take on the task of quantitative prediction for potential offspring based on the characteristics of parents and other family members. Since very few children were already insane when information on their insane parent was being entered into an admission book, hereditary prognosis required a rethinking of numerical relationships and a long-term plan for collecting data.

In 1876, Tigges encountered a better model than French tables of degeneration in the form of a twenty-five-year report from Erlangen. This was F. W. Hagen’s masterwork, a collective achievement of his staff, based, he explained, on the wisdom gained through long experience at his own asylum. Hagen had been present for sixteen of these years, including a few as assistant physician when it was new. As we have seen, he believed deeply in the accumulation of experience over time at an institution he knew intimately. The book brushed aside many bureaucratic categories to focus on what really mattered. Occupations, he argued, were so numerous that the numbers meant nothing without an appropriate way to group them. Insanity rates by geographical location were losing their value in an age of railroad travel. Marital state is certainly associated with mental illness, but how to separate cause from effect? He even dared to challenge the first article in the alienist creed: that incurability is the result of delayed admission. The correspondence between favorable outcomes and early treatment remained inconclusive, since these were often the least severe cases and might have cleared up on their own.20

Hagen described statistics as “the artificial creation of masses for the purpose of investigation.” It is like looking backward through a microscope lens, enabling the observer to concentrate on an issue that matters and to abstract away the confusing details. He was, however, less willing even than Tigges to sacrifice the exactitude of each observation for the sake of a low coefficient of error. Problems of comparability, he said, arising from flawed data collection, create far more problems than mathematical shortcomings. He assigned paramount importance to systematic collection of the right kind of data. A tally of patients discharged in apparent good health provides no measure even of recoveries. It is necessary in addition to track their careers outside the institution.21 Determining the effectiveness of treatment is more difficult still. It would require genuine controls to determine how many, if any, so-called cures were more than mere recoveries, the work of nature and not of medicine. He meditated on the possibility of a “parallel statistics” on the mentally ill outside institutions, perhaps through a historical comparison with earlier times when the prejudice against asylums was stronger. How else could alienists demonstrate that society is getting something for all it invests in asylum care? Meanwhile, he shunned aggressive therapies in favor of Bible-reading, instruction, singing, concerts, theater, and dance. He recalled a moving performance by his patients of Méhul’s opera Joseph. Maybe that was recompense enough.22

Measures of heredity, to which Hagen assigned particular urgency, were as vulnerable to flawed reasoning and misleading data as cure rates. The declaration by a relative or health official of mental disturbance in a mother or uncle proved nothing, and even a systematic search for insane relatives was insufficient. Such inquiries merely provided data on ancestors or collateral relatives, where the Anlage had already worked its harm. The practical need was to anticipate the health of offspring based on disease characteristics of older relatives. This could serve as a guide to prophylaxis for those on the threshold of mental illness and, more crucially, measure “the intensity of the danger of taking ill for offspring of the mentally ill.” Such knowledge had a clear bearing on advisability of marriage. A genealogy extending backward in time, however interesting, “lacks the force of demonstration by which to establish norms of behavior.” To look forward required new techniques for compiling data on children of the insane. As usual, his investigations began with patients in the asylum. Since the children would be very young or even as yet unborn when their parent entered an asylum, their Anlage for mental illness might remain hidden for decades. The evidence would have to be statistical and sufficient to demonstrate collective tendencies, since cases can always be countered by other cases.23

Hagen’s main contribution to the book he edited concerned the goals and methods of asylum statistics, including techniques for assembling data on discharged patients and their offspring. His institution, he explained, had from the start been assiduous in its recordkeeping, insisting always on firsthand information. The staff presented a detailed questionnaire (Fragebogen) to the physician arriving with each new patient then solicited private reports on these patients and their families. Hagen’s rule was to exclude doubtful cases from the statistics. Having laid this groundwork, he entrusted the long chapter on heredity to second assistant physician Heinrich Ullrich. A few years later, when the AZP introduced semiannual reports on psychiatric literature, Ullrich was chosen as bibliographic specialist on statistics. His contribution to the Erlangen volume, which contained almost all its tables, conformed to the new Prussian standards. Since most of the data had been gathered years earlier, the analysis cannot have been straightforward. Ullrich recognized, however, that statistical harmonization in Germany was making it easier to achieve homogeneity. He also drew inspiration from the coding techniques, tables, and conclusions of Wilhelm Jung.24

Ullrich had definite ideas about studying the hereditary factor in insanity. The best way to understand its transmission would be to track the succession of organic structures, the diseased Anlagen, from generation to generation. Diagnosed conditions served as a proxy for these Anlagen. He found high rates of nervous conditions, including “peculiarities of character,” the urge for drink, and eccentric behavior in many sane members of hereditarily burdened families, suggesting that the Anlage for disease was not quite invisible during dormant periods. His interpretation of minor neuropathies as signs of a latent mental illness was perpetuated in Mendelian interpretations of heterozygosity. Heredity appears in Ullrich’s account as a wavering pattern of fluctuation, not as a fateful decline. The statistical tables from Erlangen had very different implications from Doutrebente’s family diagrams. Ullrich did not claim to be able to track an individual Anlage, but he could measure its average force. Using a form of analysis that Hagen had been trying to transcend, he calculated that one of every 2.68 cases of mental illness was hereditary. This was a satisfying result, he thought, in good agreement with studies by Damerow, Jung, and Julius Rüppell, the best authorities, whose numbers he gave as 1:3.25, 1:2.95, and 1:2.7. There seemed to be hope of escaping the chaos of numbers described by Legrand du Saulle.25

Ullrich also gave an estimate of Hagen’s most vital measure, the probability that children of parents with mental illness will themselves become insane. Like Tigges, Ullrich sometimes reported tiny differences as if they were meaningful, yet he recognized the inadequacy of his comparative figures. It would take decades to accumulate sufficient data on the second and third generations of hereditarily burdened families in order to test the theory of degeneration. On many points that mattered, the twenty-five-year Erlangen report had only qualitative results.26 Hagen expressed greater satisfaction with his methods of investigation than with their conclusions. The data, alas, came in slowly, and he needed time. He dreamed of initiating a long-term study at a single location. We discover in his chapter a reprinted circular sent to physicians all over Bavaria asking those with information on discharged Erlangen patients to fill out and return a data form. In big cities like Munich, where many of these former patients would be unknown to the district physicians, he also sent inquiries to church offices. In either case, he checked and corrected all such information. He described this kind of work as more valuable than mathematical calculation of probable errors. In time, the data required should come in.27

Pedigree Shortcuts for Long Generations

The problem of hereditary insanity, whether explained by degeneration or not, appeared even more urgent to German alienists than to French ones. Morel wrote in an 1870 asylum report that, apart from general paralysis, the increase of the insane since 1838 was an illusion, the result of sick persons now having better options than prisons and poorhouses.28 Others, to be sure, found Morel’s theory more alarming than he did. Although Tigges’s antidegenerationist arguments were endorsed by commentators in the AZP and in a leading medical reviewing journal, many German alienists, including Hagen, were less certain than Tigges of the incorrectness of Morel’s theory.29 And Tigges, like Hagen, was working urgently on alternative techniques to anticipate mental illness of the children based on the health status of their parents. He praised as exemplary Hagen’s meticulous efforts to maintain the flow of data on former Erlangen patients and their families, yet even Hagen, after all these years, could identify only a fraction of inherited mental illness that eventually would erupt among the descendants of patients. Tigges did not want to wait. The most vital contribution of asylums to public health was at stake.

“From a certain number of mentally ill parents come a certain number of children, healthy and mentally ill,” and we want to know what percentage will be sick. “The question is posed, whether there is a means and a way to press forward to the final goal of research,” to calculate what proportion of mental illness in the general population is owed to ongoing transmission from mentally ill parents. These empirical investigations, like those of Hagen and of Doutrebente, began with current asylum patients. Hagen looked to earlier generations to determine if the insanity was hereditary, and to the children to determine how often the disease was inherited. Was there a better way than waiting for data on the children of his patients? One element of the solutions would be to compensate for incomplete family data by matching the children to adults with a similar background of family illness.30

Tigges had already adumbrated a method of generational comparison in his 1867 Marsberg report, as a correction to Morel’s analysis of degeneration. Twelve years later, he laid out a specific proposal to orient research, not around the children of the insane, but the children of their parents. We might simply say, their siblings, but this glides by his innovative logic of investigation. The admission of a new patient should bring immediate attention to the parents, who assume a role in the study comparable to that of the patients themselves in prior studies, including Hagen’s. The health of their parents and siblings, the grandparents, aunts, and uncles of the institutionalized patient, would give an indication of the presence of a family Anlage for mental or nervous illness. Did Tigges reason in a circle by using the condition of parents and their siblings to identify hereditary cases? His finding that parents with insane heredity had more children might reduce to the near-tautology that families with more members are more likely to have at least one diagnosed as insane. Tigges, in fact, recognized the problem without quite knowing how to handle it, except by searching for the right kind of data. Three decades later, Wilhelm Weinberg made these issues central to the quantitative study of psychiatric heredity.31

Tigges presented this research in 1879 as his contribution to a symposium on the redesign of—what else?—asylum census cards. The space for entering information on each patient was very limited, and much of it, he charged, was wasted. He proposed to clear away enough bureaucratic trivia so that each card could include an entire family tree, which could then be used to calculate the probability of mental illness in children of asylum patients and to compare that number with the probability for offspring of healthy parents. Already, he explained, he was correcting for age distribution and calculating this probability for parents at his institution. Tigges reckoned that a child of a patient was 162.9 times more likely to become mentally ill than a child of healthy parents. He rounded his multiplier to 160 then rounded it again to 150 for the summary of his Sachsenberg report in the AZP. Still, the hereditary reproduction of insanity appeared in his work as an immensely powerful force.32

Although Hagen, Ullrich, and Tigges were also curious about the mechanisms of transmission of mental illness, they focused on the empirical experience of transmission across generations. Even if it was not possible to know with certainty which families possessed a diseased Anlage, they did not doubt its reality. Their ambitions recall Dahl’s: to track the transmission of the Anlage through the generations and to measure its contribution to the great social and medical problem of insanity in order, someday soon, to take action.