3.9 Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Examination

Many neurologic illnesses are associated with more or less severe

disturbances of cognitive and emotional function. The organic neurologic

clinical picture is only complete when any psychopathologic abnormalities

that may be present have been thoroughly assessed and documented. The goal

of the neuropsychological examination is to reveal cognitive deficits

(especially aphasia, agnosia, and apraxia) and processing disturbances that

imply the presence of a focal brain lesion.

3.9.1 Psychopathologic Findings

The examiner should first determine whether the patient is awake and

alert. If not, he or she will be unable to receive and process incoming

stimuli in the normal way. The patient may have an impairment of consciousness ranging in severity from drowsiness

to coma, as described in ▶ Table 3.10.

Table 3.10 Degrees of impairment of consciousness,

and other abnormal states of consciousness

|

Designation

|

Features

|

|

Normal consciousness

|

Oriented to place, time, and person (self), answers

questions promptly and appropriately, follows commands

correctly

|

|

Drowsiness

|

Mostly awake, responds to questions and commands slowly

but usually correctly (after repetition if necessary), moves

in response to a sufficiently intense stimulus, usually

oriented and coherent

|

|

Somnolence

|

Mostly asleep, arousable with a moderately intense

stimulus, generally requires repetition of questions or

commands but then responds correctly, reacts slowly and

after a delay but usually correctly

|

|

Stupor

|

Asleep unless awakened, can only be awakened with a strong

(auditory) stimulus or perhaps only with a mechanical

stimulus, cannot answer questions or follow commands or does

so only after intense repetition, and then only

incompletely

|

|

Coma

|

Unconscious, cannot be awakened, does not respond to a

verbal or auditory stimulus, may respond to painful stimuli

of graded intensities with specific (localizing)

self-defense, nonlocalizing withdrawal of a limb, or

abnormal flexion or extension responses

|

|

Confusion

|

Inappropriate spontaneous behavior and responses to

questions and commands, deficient orientation to place,

time, and/or person (self); the confused patient may be

fully conscious, less than fully conscious, or agitated (see

below)

|

|

Agitation

|

Motor unrest, inappropriate spontaneous behavior, cannot

be calmed by verbal persuasion, more or less disoriented,

does not follow commands appropriately

|

In addition to the patient’s level of consciousness and

attention, the examiner should assess his or her orientation, concentration, memory, drive, affective state, and cognitive

ability. The overall psychopathologic picture is composed of

these elements. If mental functioning is disturbed by an underlying

neurologic illness (so-called psycho-organic

syndrome or organic brain syndrome),

the manifestations often progress in a characteristic sequence, regardless

of the etiology. At first, short- and long-term memory, concentration, and

attention are impaired; the patient is easily fatigued and has difficulty

processing new information or performing complex tasks. Later, the patient

becomes progressively disoriented, first to time, then to place, and then to

person (self). Reactive depression is common at this stage. Ultimately, all

spontaneous activity ceases; the patient loses interest, lacks drive, and

becomes permanently confused. Disturbances of this type can often be

discerned in the patient’s behavior before the formal examination begins,

growing increasingly evident to the examiner during history-taking and

physical examination. Further details of the patient’s history from the

family can often help. The Mini-Mental State

Examination ( ▶ Table 3.11, ▶ Fig. 3.36) and the clock test

( ▶ Table 3.12)

are widely used to assess cognitive function; the MOCA test is a

well-validated alternative (see www.mocatest.org). For acquired dementia,

see section ▶ 6.12.

Table 3.11 Mini-Mental State Examination

|

Parameter

|

Questions

|

|

Name of patient:

Date of birth:

Date of examination:

1 point for each correct answer

|

|

Orientation in time

|

|

1.

|

|

|

2.

|

|

|

3.

|

|

|

4.

|

|

|

5.

|

|

|

Orientation to place

|

|

6.

|

|

|

7.

|

|

|

8.

|

|

|

9.

|

|

|

10.

|

|

|

Retentiveness

|

|

“Please repeat the following words” (to be spoken at one

word per second; to be performed only once)

|

|

11.

|

|

|

12.

|

|

|

13.

|

|

|

Attention and calculations

|

|

14.

|

“Please count from 100 backward by sevens” (serial-7

test). One point for each correct subtraction, maximum five

points

|

|

Recent memory

|

|

15.

|

“Which three words did you repeat earlier?” One point for

each word correctly recalled

|

|

Language, naming

|

|

16.

|

|

|

17.

|

|

|

18.

|

|

|

Language comprehension, motor

execution

|

|

19.

|

|

|

20.

|

|

|

21.

|

|

|

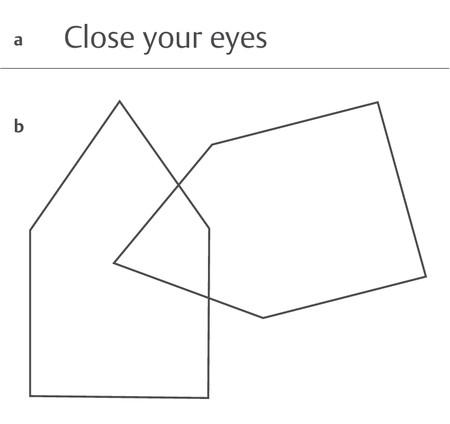

Reading

|

|

22.

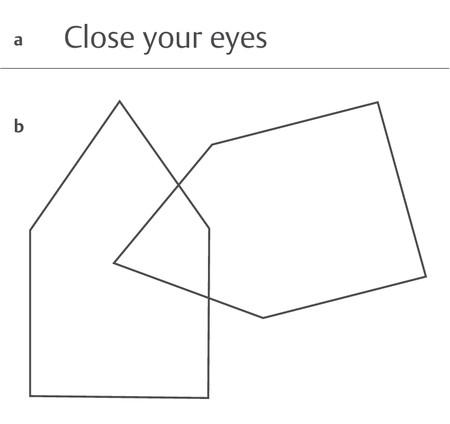

|

“Please do what it says on this card” (show card: “Close

your eyes”) ( ▶ Fig. 3.36a)

|

|

Writing

|

|

23.

|

“Write any sentence” (the patient is given a piece of

paper and something to write with)

|

|

Drawing

|

|

24.

|

“Please copy this drawing” (overlapping pentagons, ▶ Fig. 3.36b;

all 10 edges of the two pentagons must be drawn, and the

pentagons must overlap, for the patient to receive one point

for this task)

|

|

Level of wakefulness:

|

|

Total points achieved:

|

Table 3.12 The clock test

|

Task

The patient is given a piece of paper with an

empty circle drawn on it and is asked to complete the

drawing of a clock, including numbers and hands. The time

shown should be 10 minutes past 11 o’clock.

|

|

Interpretation

|

Points if correct

|

|

Are all 12 numbers present?

|

1

|

|

Is the number “12” at the top?

|

2

|

|

Are two hands of different lengths present?

|

2

|

|

Is the indicated time correct?

|

2

|

|

Note: A score of 5 or below raises the

suspicion of dementia.

|

Fig. 3.36 Forms for the

Mini-Mental State Examination. a A written command for

the patient to follow (Task 22 in ▶ Table 3.11). b Pentagons to be copied (Task 24 in ▶ Table 3.11). (Reproduced from Mattle H, Mumenthaler

M. Neurologie. 13th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2013.)

3.9.2 neuropsychological Examination

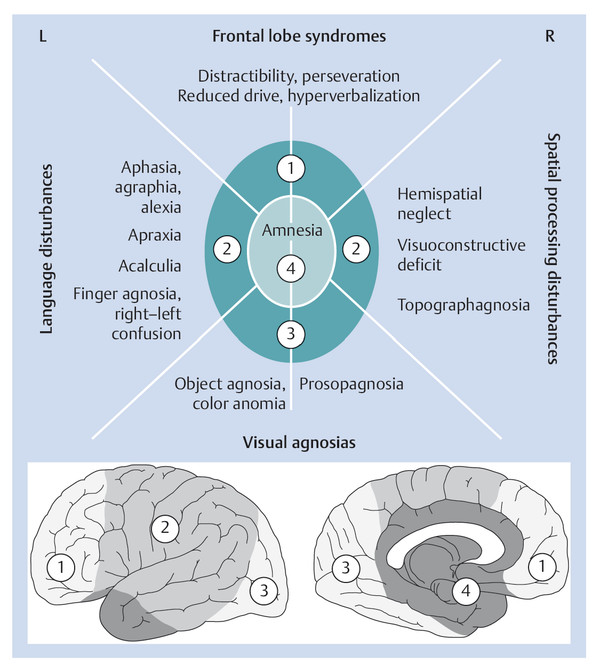

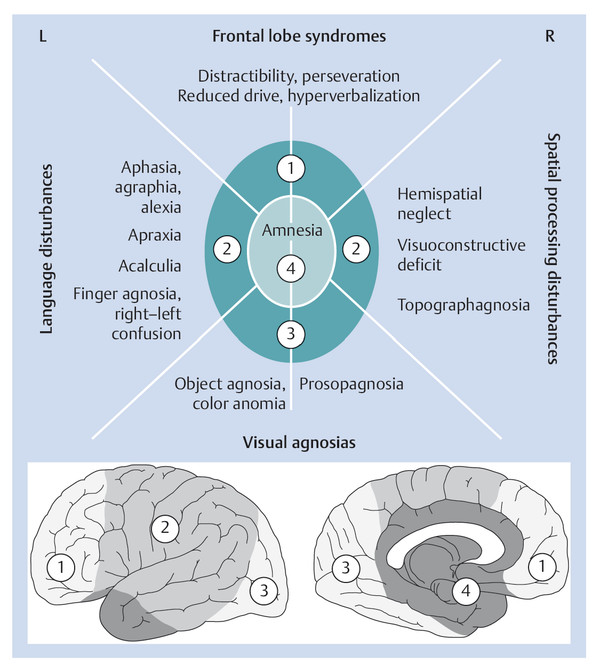

The localizing significance of various neuropsychological deficits is

shown in ▶ Fig. 3.37. An overview of important neuropsychological

terms and syndromes is provided in ▶ Table 3.13.

Table 3.13 Important neuropsychological terms and

syndromes

|

Aphasia

|

Cortical disturbance of language, usually due to a

left-hemispheric lesion

|

|

Spatial processing

disturbance

|

Difficulty drawing or copying three-dimensional figures

(cube, house, five-pointed star); neglect of the left side

of space or the left side of the body (so-called hemispatial

neglect); usually due to a right-hemispheric lesion

|

|

Apraxia

|

Disturbance of the goal-directed execution of complex

behaviors or behavioral sequences, or of the use of

tools:

More common with left-hemispheric than with

right-hemispheric lesions

|

|

Agnosia

|

Disturbance of the ability to recognize and correctly

interpret various kinds of sensory stimuli, despite intact

sensory function.

-

Visual agnosia: inability

to recognize objects visually despite intact vision.

Special types: color agnosia, prosopagnosia

(inability to recognize faces). The responsible

lesion is located in the occipital or

occipitotemporal visual cortex

-

Tactile agnosia: objects

cannot be recognized by touch with the eyes

closed

-

Anosognosia: deficit of

self-awareness, i.e., denial or trivialization of

one’s own pathologic deficits

|

Aphasia

Language is a complex process encompassing numerous individual

functions ( ▶ Table 3.14).

Table 3.14 Functions that are needed for normal

language

|

Function

|

Disturbance

|

|

Hearing

|

Hearing impairment, deafness

(section ▶ 12.6.1)

|

|

Comprehension

|

Sensory aphasia

|

|

Construction of words and thoughts

|

|

|

Construction of speech

|

Motor aphasia

|

|

Phonation and articulation

|

Hoarseness (section ▶ 12.7), dysarthria (see

sections ▶ 3.9.1, ▶ 5.5.5, and ▶ 12.9)

|

Fig. 3.37 Cognitive

deficits that typically result from various focal

brain lesions. (Adapted from Schnider A. Verhaltensneurologie.

2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2004.)

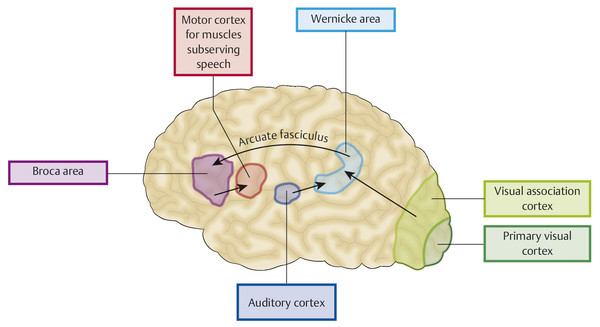

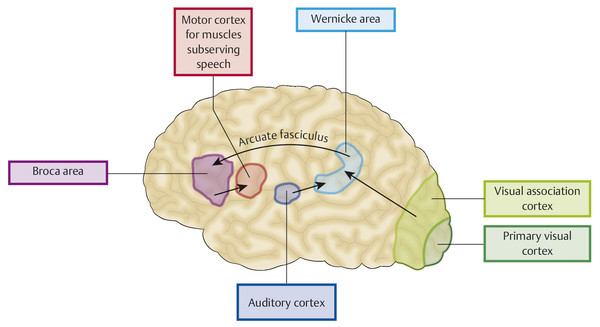

Cortical disturbances of language are called aphasia and are due to a lesion in the language-dominant

hemisphere. The left hemisphere is dominant for language in nearly all

right-handers and in most left-handers as well. The clinical varieties

of aphasia are:

-

Disturbances of language production (motor aphasia or Broca aphasia; ▶ Fig. 3.38 and

▶ Fig. 4.12): the

patient’s spontaneous speech is not fluent, even though the

“organic prerequisites” for speech production (phonation,

breathing, orofacial musculature) are all apparently

unimpaired.

-

Disturbances of language comprehension (sensory aphasia or Wernicke aphasia;

▶ Fig. 3.38 and

▶ Fig. 4.12): the

patient has trouble understanding speech despite intact hearing

and auditory processing. The patient’s spontaneous speech is

fluent.

-

Disturbances of speech repetition. The patient cannot

correctly repeat words or sentences spoken by the

examiner.

-

Nearly all patients with aphasia have difficulty with naming

and word-finding.

Fig. 3.38 Brain

structures that participate in language

function.

The examiner begins to assess the patient’s spontaneous

speech while taking the history; if necessary, the patient can be given

specific language tasks, for example, “Describe this picture.” Various

kinds of abnormality may be noted. The patient’s utterances may be found

to be unusually poor in meaning-bearing words and overloaded with

connectives and “function words.” Sentences may be faultily constructed

(paragrammatism). The flow of speech may be

either considerably greater than normal or slow and hesitant (telegraphic speech). Individual words may be

deformed in certain characteristic ways (e.g., sound substitutions or

phonemic paraphasias, such as “cog” for

“dog”), or words may be used in place of other words from the same

semantic category (semantic paraphasias, e.g.,

“table” for “chair”). Some words may be replaced by invented pseudowords

(neologisms). Impaired language

comprehension may be manifested by the patient’s inability to point out

various objects in the room, including parts of his or her own body,

when these are named by the examiner. Complex commands are an even more

sensitive functional test. The patient can be asked, for example, to

place a certain named object in between two other named objects, or to

interpret a complicated sentence, such as the following: “Not in the

closet, but on top of it, was where he had put his hat. Where was the

hat?” Aphasic patients often make mistakes when they repeat spoken

sentences or name objects (including parts of the body) that are pointed

out to them. Reading and writing may also be impaired, often to a

greater extent than spoken language.

The different types of aphasia are classified by the characteristics

of the patient’s spontaneous speech, comprehension and repetition of

speech, word-finding, and naming ( ▶ Table 3.15). An aphasic patient whose

spontaneous speech lacks fluency speaks slowly, with effort, in short

sentences containing many meaning-bearing words, with paraphasias and

altered melody of speech (dysprosody). An aphasic patient with fluent

spontaneous speech speaks at normal speed, effortlessly, and with the

normal melody of speech (prosody), but the sentences are of normal

length but contain relatively few meaning-bearing words in relation to

meaningless filler words and literal and semantic paraphasias.

Table 3.15 The classification and differential

diagnosis of aphasia

|

Type of aphasia

|

Spontaneous speech

|

Comprehension

|

Repetition

|

Naming, word-finding

|

|

Motor aphasia

(Broca)

|

Nonfluent

|

Normal

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

|

Sensory aphasia

(Wernicke)

|

Fluent

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

|

Conduction aphasia

|

Fluent

|

Normal

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

|

Global aphasia

|

Nonfluent

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

Impaired

|

|

Transcortical motor aphasia

|

Nonfluent

|

Normal

|

Normal

|

Impaired

|

|

Transcortical sensory aphasia

|

Fluent

|

Impaired

|

Normal

|

Impaired

|

|

Anomic aphasia

|

Fluent

|

Normal

|

Normal

|

Impaired

|

Dysarthria is not a disturbance of

language, but of the mechanical process of speech production

(articulation); the content of speech is normal. When the motor

apparatus of speech is affected by a central paresis or a muscular

coordination disorder, the patient’s speech becomes unclear or slurred,

perhaps even unintelligible.

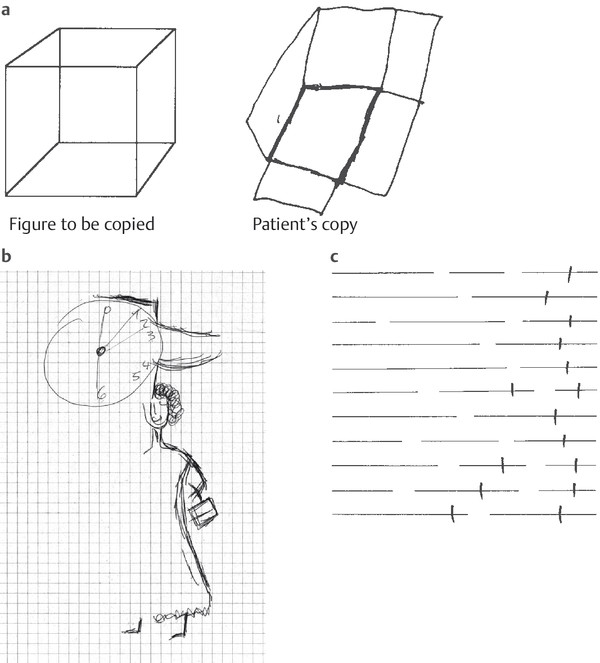

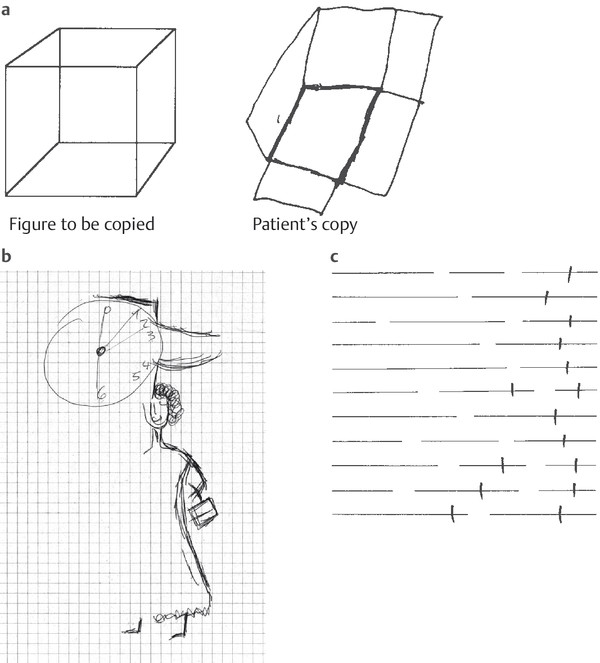

Disturbances of Spatial Processing

Disturbances of spatial processing are usually caused by

right-hemispheric lesions. They are manifested, for example, by unusual

difficulty in spontaneously drawing or copying three-dimensional figures

(cube, house, etc.) ( ▶ Fig. 3.39a). Deficits of

this kind are often accompanied by neglect of the left side of space and

the left half of the patient’s own body (hemispatial

neglect; ▶ Fig. 3.39b,c).

Fig. 3.39 Spatial

processing and neglect. a Cube-drawing as a test of spatial

processing. This drawing is by a patient with a right

parietal lesion. b Drawings of a clock and a

woman. The left half of each is missing, indicating

severe left hemineglect. The patient had sustained an acute

hemorrhage in the right parietal lobe. c

Line-dividing test. The patient was a university

professor with left-sided neglect due to a tumor (astrocytoma)

in the right hemisphere. (Reproduced from Mattle H, Mumenthaler

M. Neurologie. 13th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2013.)

Memory and Amnesia

Memory enables us to store and recall information; it makes

learning possible. There is a somewhat arbitrary distinction between

short- and long-term memory; the

latter, in turn, is divided into recent and old

memory.

Short-term memory, also called working

memory, is that which we are able to keep in mind at any one

moment. Its content is rapidly lost unless it is kept active by

repetition and transferred to long-term memory.

The examiner gains a first impression of the patient’s short- and

long-term memory while taking the history. To test short-term memory, one can ask the patient to repeat

sequences of numbers forward and backward or to take mental note of a

sequence of 3 to 10 words and repeat them, immediately and a few minutes later.

Old memory can be tested by asking

the patient to state autobiographic data that can be checked against

other sources, facts about his or her own family, or information about

historical dates, political events, or public figures. The findings

should be interpreted in the light of the patient’s premorbid level of

intelligence and education.

Short-term memory and verbal memory are mainly subserved by the limbic

system (section ▶ 5.5.4) and

hippocampus. Memory disturbances are called amnesia.

Amnesia is the inability to

store or recall conscious memories. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to lay down new

memories from the moment of a brain injury onward. Retrograde amnesia is the inability to recall

information that was acquired before the brain injury. Persistent

amnesia is the main clinical manifestation of dementia

(section ▶ 6.12).

Apraxia

Disturbances in the goal-directed execution of complex

actions or sequences of actions, or in the use of objects, are known as

apraxia. If the individual components of a

single action cannot be put together

correctly, the patient is suffering from ideomotor

apraxia. Different parts of the body can be affected

individually. In facial apraxia, for example, the patient may be unable

to follow commands to execute certain motor tasks with the face, e.g.,

drinking through a straw or clicking the tongue. A patient with

ideomotor apraxia of the upper limbs may be unable to salute or to mime

the action of slapping someone in the face; a patient with ideomotor

apraxia of the lower limbs may be unable to kick an imaginary football.

In ideational apraxia, individual actions can

be performed, but cannot be combined into more complex sequences. A

patient might thus be unable to ready a letter for mailing, as this

requires several steps: folding the letter, putting it in the envelope,

sealing the envelope, and putting a stamp on it. Cortical lesions

causing apraxia are usually on the left side.

Agnosia

Agnosia is an inability to recognize and correctly

interpret incoming stimuli in a particular sensory modality, even though

sensation as such is intact. A patient with visual

agnosia, for example, has no visual impairment but cannot

recognize objects on sight; the patient can name an object only after

feeling or hearing it (e.g., the jangling of a bunch of keys). Special

types of visual agnosia include an inability to recognize colors (color

agnosia) or faces (prosopagnosia). The responsible lesion is in the

visual association cortex, that is, in the occipital or occipitotemporal

region, in one or both hemispheres.

Stereognosis is tested by putting a familiar object (key,

pair of scissors) in the patient’s hand and asking him or her to palpate

and name it (with eyes closed). An inability to do this despite intact

sensation is called tactile agnosia. Further

special types of agnosia are finger agnosia and autotopagnosia

(difficulty recognizing parts of one’s own body).

Anosognosia is the denial or

trivialization of one’s own neurologic deficits, for example, hemiplegia

or even blindness.

Higher Cognitive Functions

For an individual to thrive in his or her social environment and cope

adequately with the demands of everyday life, more is needed than just a

properly functioning interaction of the basic neuropsychological

functions described earlier. A person’s fund of knowledge, memory,

intelligence (i.e., the capacity for abstract thought and

problem-solving), personality, and social behavior are all of vital

importance, as are his or her mood and motivation. The assessment of

these higher cognitive functions requires careful weighing of biographic

historical information (particularly useful when derived from persons in

the patient’s social environment: family, friends, colleagues), as well

as standardized neuropsychological testing. For example, there are

specific tests for the patient’s fund of knowledge, logical thinking,

and cognitive skills such as difference recognition, category formation,

and the interpretation of symbolic information, for example, proverbs.

These higher integrative functions are performed by the cerebral cortex

in collaboration with other, deeper regions of the brain.