6.11 Cerebellar Diseases and Other Conditions Causing Ataxia

Cerebellar disturbances present clinically with disequilibrium, truncal

and/or appendicular ataxia, impaired coordination, and diminished muscle

tone (see also section ▶ 5.5.6).

6.11.1 Overview

Classification The different clinical types of ataxia can be classified in

several ways:

Clinical features Ataxia is characterized by impaired coordination of

movement and a dysfunctional interplay of agonist and antagonist

muscles. Thus, it typically manifests itself as poorly

controlled movements that tend to overshoot their target. The

additional manifestations of the individual diseases causing ataxia depend

on their etiology and the particular neural structure involved.

Ataxia can be caused not only by cerebellar disease, but

also by disease of the afferent and efferent pathways leading to and

from the cerebellum, or of any afferent somatosensory or special sensory

pathways. The underlying lesion may be in the cerebellum, but it may

also be in the brainstem, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, sensory

cortex, or thalamus.

An initial, clinically based classification of ataxia distinguishes symmetric from focal,

asymmetric types ( ▶ Table 6.36). The table can serve as an overview and

guide to the differential diagnosis of ataxia.

Table 6.36 The differential diagnosis of symmetric

and focal asymmetric ataxias

|

Symmetric ataxia

|

Focal asymmetric ataxia

|

-

Acute or chronic intoxication

-

Electrolyte disturbance

-

Acute viral cerebellitis

-

Miller Fisher syndrome

-

Postinfectious, ADEM

-

Alcoholic-nutritional cerebellar damage

-

Vitamin B1 deficiency

-

Vitamin B12 deficiency

-

Paraneoplastic cerebellar disease

-

Antigliadin antibody syndrome

-

Hypothyroidism

-

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

-

Hereditary cerebellar degeneration

-

Familial episodic ataxia

-

Multisystem atrophy

-

Tabes dorsalis

-

Psychogenic ataxia

|

-

Ischemic stroke

-

Cerebellar hemorrhage

-

Subdural hematoma

-

Abscess

-

Neoplasia (primary brain tumor, metastasis)

-

Demyelinating plaque, multiple sclerosis

-

Arteriovenous malformation, arteriovenous

fistula

-

Arnold–Chiari or Dandy–Walker malformation

-

Psychogenic ataxia

|

Diagnostic evaluation When ataxia is suspected, the age at

onset and the family history are

diagnostically relevant:

-

If ataxia arises in childhood or adolescence in a

patient with a positive family history, the diagnosis is probably an

autosomal recessive ataxia. The most

common of these is Friedreich ataxia.

-

If a parent is similarly affected, then the diagnosis

is probably an autosomal dominant ataxia,

for example, spinocerebellar ataxia.

-

Ataxia arising after age 40 years is less likely to be

hereditary and may be an acquired ataxia,

for example, of toxic origin (such as alcohol-induced cerebellar

degeneration).

Individual types of ataxia can be diagnosed by

molecular-genetic testing, imaging studies, or laboratory analysis.

Treatment The symptom complex called “ataxia” has no specific treatment,

although coordination may be improved by physiotherapy. Certain types of ataxia of known cause can be

correspondingly treated: examples include vitamin E administration in ataxia

due to vitamin E deficiency and in Aβ-lipoproteinemia, a diet that is low in

phytanic acid in Refsum disease, and a low-copper diet combined with

chelators or zinc in Wilson disease.

6.11.2 Selected Types of Ataxia

Disturbances of the cerebellum, like those of the cerebral

hemispheres, are usually due either to vascular processes (ischemia,

hemorrhage) or to tumors. Multiple sclerosis is a further common cause.

In this section, we will also discuss other diseases that may present

primarily with cerebellar dysfunction, including infectious,

parainfectious, (heredo-)degenerative, toxic, and paraneoplastic

conditions, as well as cerebellar involvement in general medical

diseases.

A thorough description of each ataxia syndrome would be beyond the

scope of this textbook, and we therefore discuss only the more important

ones briefly. Friedreich ataxia is described in greater detail in a

later chapter (section ▶ 7.6.2) among the other hereditary diseases

of the spinal pathways.

Cerebellar Heredoataxias

Cerebellar heredoataxias are of genetic

origin. The enzymatic defects and pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying

each have not yet been determined, except in a few cases. The main types

are listed in ▶ Table 6.37. Spinocerebellar

ataxias involve both the cerebellum and the spinal cord and

are associated with cognitive deficits as well (see

sections ▶ 7.6.1 and

▶ 7.6.2).

Table 6.37 Types of cerebellar ataxia

|

Disease

|

Clinical features

|

Remarks

|

|

Autosomal

recessive hereditary ataxias

|

|

Friedreich ataxia

|

-

Lumbering, broad-based, unsteady gait,

progressive from the first or second decade

onward

-

Later, clumsiness of the hands, explosive

speech

-

Typical Friedreich foot (see ▶ Fig. 7.15)

-

Scoliosis, hypotonia

|

GAA triplet expansion on chromosome 9; impaired

synthesis of the protein frataxin

|

|

Refsum disease (heredopathia

atactica polyneuritiformis)

|

|

Lack of phytanic acid α-dehydrogenase

|

|

Aβ-lipoproteinemia

(Bassen–Kornzweig syndrome)

|

-

Progressive ataxia, nystagmus,

ophthalmoplegia, polyneuropathy

-

Acanthocytosis, low cholesterol and

triglyceride levels, vitamin E deficiency

|

Low serum lipoprotein, cholesterol, and triglyceride

levels

|

|

Ataxia telangiectasia

(Louis–Bar syndrome)

|

-

Onset in infancy with ataxia and

choreoathetosis

-

Frequent lung, ear, nose, and throat

infections

-

Slow eye movements

-

Telangiectases in conjunctiva and joint

creases

|

One of the chromosomal fragility syndromes

|

|

Spinocerebellar ataxia

(different varieties, e.g., deficiencies of

hexosaminidase, glutamate dehydrogenase, pyruvate

dehydrogenase, ornithine transcarbamylase, or vitamin

E)

|

-

Onset usually before age 10 y

-

Ataxia with variable accompanying deficits,

e.g., intellectual disability, visual or hearing

impairment, polyneuritis, myoclonus

-

Speech may be loud, deep, and harsh (“lion’s

voice”)

-

If hereditary, generally autosomal

recessive

|

|

|

Autosomal

dominant hereditary cerebellar ataxias

(ADCA)

|

|

Cerebellar cortical atrophy

(Holmes type = Harding type III)

|

|

Genetically heterogeneous, SCA 5 and SCA 6

|

|

Olivopontocerebellar atrophy

(Menzel type = Harding type I)

|

-

Onset at age 20 y or later

-

Cerebellar and noncerebellar signs including

optic nerve atrophy, basal ganglionic dysfunction,

pyramidal tract signs, muscle atrophy, sensory

deficits, and sometimes dementia

|

Genetically heterogeneous, SCA 1–SCA 4; SCA 3 =

Machado–Joseph disease

|

|

Cerebellar atrophy (Harding

type II)

|

|

Corresponds to SCA 7

|

|

Autosomal

dominant hereditary episodic

ataxias

|

|

Familial periodic paroxysmal

ataxia

|

|

|

|

Sporadic,

nonhereditary ataxias

|

|

“Atrophie cérébelleuse tardive à

prédominance corticale”

|

-

Onset in late adulthood with slowly

progressive gait and truncal ataxia, later arm

ataxia

-

Rarely, nystagmus, muscle hypotonia, and

pyramidal tract signs

|

Symmetric degeneration of Purkinje cells,

predominantly in the vermis; alcohol may be a

precipitating factor in persons with an underlying

genetic predisposition

|

The most common hereditary ataxia is Friedreich ataxia, an autosomal disorder with onset

usually in the first or second decade of life that generally leads

to death between the ages of 30 and 40 years. Its typical

manifestations are the following:

-

Unsteady gait, particularly with eyes closed; areflexia,

pyramidal tract signs.

-

Dysphagia, cerebellar dysarthria, oculomotor disturbances

(gaze-evoked nystagmus, square-wave jerks, abnormal

suppression of the vestibulo-ocular reflex,

▶ Fig. 12.6).

-

Optic nerve atrophy.

-

Early loss of proprioception and vibration sense.

-

Distal muscle atrophy, typical foot deformity (pes cavus),

kyphoscoliosis.

-

Cardiac manifestations (conduction abnormalities,

cardiomyopathy), diabetes mellitus.

-

Cognitive disturbances.

-

Dementia.

Symptomatic Types of Ataxia and Cerebellar

Degeneration

Aside from hereditary and idiopathic types of ataxia and cerebellar

degeneration, there are also types that reflect particular underlying

illnesses, including a wide variety of cerebellar and systemic diseases

( ▶ Table 6.38). The clinical manifestations vary

depending on the cause. Other systems and organs are often

involved.

Table 6.38 Causes of symptomatic ataxia and

cerebellar degeneration

|

Cause or precipitating factor

|

Examples and remarks

|

|

Local disease: mass lesion or

ischemia

|

Malformation, cerebellar tumor, infarct, hemorrhage,

inflammation, trauma or other physical causes

|

|

Infection

|

Often in the aftermath of an infectious disease, e.g.,

mononucleosis

Acute cerebellar ataxia in

childhood arises a few days or weeks after a

chickenpox infection, less commonly after another viral

illness. The patient is usually a preschool-aged child.

Unsteady gait, ataxia, tremor, and nystagmus are the

characteristic signs; they usually resolve spontaneously

in a few weeks.

Acute cerebellitis is similar

to the foregoing and affects both children and adults.

In older patients, the manifestations can persist

|

|

Systemic diseases

|

For example, multiple

sclerosis, macroglobulinemias

|

|

Toxic conditions

|

Tardive cerebellar atrophy

in chronic alcoholism,

other toxic causes (diphenylhydantoin, lithium, organic

mercury, piperazine, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil,

DDT)

|

|

Metabolic and hormone-associated

conditions

|

Familial AVED (an autosomal recessive condition that

clinically resembles Friedreich ataxia), vitamin B

deficiency

Hypothyroidism and myxedema

Malresorption syndrome, gluten intolerance

(gluten-induced ataxia with or without gastrointestinal

manifestations)

|

|

Paraneoplastic

conditions

|

Subacute cerebellar cortical atrophy

|

|

Further causes

|

-

Heatstroke

-

Miller Fisher syndrome (see

section ▶ 11.2.3)

-

Cranial polyradiculitis (see

section ▶ 11.2.3)

-

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (see

section ▶ 6.7.9): ataxia is

sometimes the first sign of this disease

|

Intermittent cerebellar manifestations

are found mainly in the following diseases:

The differential diagnosis of cerebellar ataxia must also include

disease processes that cause ataxia but do not involve the

cerebellum:

-

(Contralateral) frontal lobe

lesions.

-

Paresis of any cause.

-

Lesions of the afferent sensory

pathways (e.g., polyneuropathy or posterior column

lesion).

-

Lesions of the parietal sensory

cortex.

A prolonged beridden state (“bed ataxia”) and

psychogenic mechanisms are further possible

causes.

6.12 Dementia

Unlike the terms “intellectual disability” and “oligophrenia,”

which refer to congenital disturbances, the term “dementia” refers to an

acquired degeneration of intellectual and cognitive abilities that persists

for at least several months or takes a chronically worsening course, leading

to major impairment in the patient’s everyday life. The clinical picture is

dominated by personality changes as well as neuropsychological and

accompanying neurologic (particularly motor) deficits. Reactive changes,

including insomnia, agitation, and depression, are common.

In this chapter, we will first provide an overview of the general aspects of

the dementia syndrome and then describe the main types of degenerative brain

disease that cause dementia in greater detail.

6.12.1 Overview: The Dementia Syndrome

Etiology and classification

Unlike the various types of neuropsychological disturbance

caused by focal brain lesions, the dementia syndrome is caused by a

diffuse loss of functional brain tissue.

Neuroimaging usually discloses extensive brain

atrophy or multifocal brain

lesions.

Primary brain atrophy The loss of functional tissue is often due to primary

(degenerative) brain atrophy, which mainly affects the cerebral cortex,

progresses chronically, and causes irreversible cognitive impairment. In

such cases, dementia is the direct consequence and most obvious

expression of the causative pathologic process. Primary brain atrophy

characterizes dementing diseases in the narrow

sense of the term:

Symptomatic dementia In principle, however, any disease that damages the

structure or function of the brain can produce the dementia syndrome.

Dementia, in such cases, is often a possible but not

universal accompaniment of the main features of the disease

in question, and is generally not the only manifestation. It is

important to realize that nearly 10% of all cases of dementia are due to

diseases that can be reversed, or at least kept from progressing

further, by appropriate treatment. The timely diagnosis and treatment of

such patients is crucial for the prevention of further

deterioration.

Cortical and subcortical dementia In cortical types of dementia,

dementia is the main manifestation of the

disease (classic example: Alzheimer disease). In contrast, movement disorders are typically prominent in

patients with subcortical dementia.

Overview of causes ▶ Table 6.39

contains an overview of the causes of dementia, with an indication of

which among these conditions are irreversible and which are at least

partly treatable.

Table 6.39 Causes of dementia

|

Type

|

Treatability

|

Diseases

|

|

Degenerative diseases of the nervous

system

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

-

Frontotemporal dementia (Pick disease)

-

Frontal lobe degeneration

-

Pantothenate kinase–associated

neurodegeneration

-

Heredoataxias

-

Lewy body disease

-

Corticobasal degeneration

-

Fragile-X syndrome

|

|

Cerebrovascular

diseases

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

-

Amyloid angiopathy

-

CADASIL

|

|

Infectious dementias

|

Treatableb

|

|

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

-

Prion diseases:

-

Kuru

-

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

-

Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker

syndrome

-

Familial fatal insomnia

-

Familial progressive subcortical

gliosis

|

|

Metabolic disorders affecting the

brain

|

Treatableb

|

|

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

|

|

Neoplasia

|

Partly treatable

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

|

|

Autoimmune

encephalopathies

|

Treatableb

|

|

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Epilepsy

|

Treatableb

|

|

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Mental illnesses

|

Treatableb

|

-

Depression

-

Schizophrenia

-

Hysteria

|

|

Hydrocephalus

|

Treatableb

|

|

|

Trauma

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

|

Irreversible

|

|

|

Demyelination

|

Partly treatablea

|

|

All patients with dementia deserve a thorough diagnostic

evaluation, because a treatable cause may be discovered.

Epidemiology

One percent of persons aged 60 to 64, and more than 30% of

persons older than 85 years, suffer from dementia. The most common cause is

Alzheimer disease, which accounts for 40 to 50%

of all patients. The second most common cause, and the most common cause of

symptomatic dementia, is vascular (i.e., multi-infarct)

dementia (15%); the third most common cause is alcoholism.

General clinical features

The dementia syndrome is characterized by

neuropsychological deficits, personality changes, and behavioral

abnormalities. In particular, the following are seen:

-

Impairment of short-term and long-term memory:

-

Impairment of thinking,

particularly with respect to:

-

Judgment.

-

Problem-solving.

-

Symbol comprehension.

-

Impairment of visuospatial and spatial-constructive

functions.

-

Aphasia and apraxia.

-

Impairment of attention and concentration.

-

Reduced drive, initiative, and motivation; easy

fatigability.

-

Affect lability and impaired affect control.

-

Impairment of emotionality and social behavior.

-

In some patients, confusion and impairment of

consciousness.

General diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of the dementia syndrome is based on thorough

history-taking from the patient and family

members, a comprehensive general medical and

neurologic examination, and neuropsychological testing.

Screening tests The following can be used as screening tests for dementia,

although they are not very informative or specific:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

( ▶ Table 3.1).

-

Clock test (the patient is asked to draw a clock face

indicating a particular time).

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test: this test

simultaneously assesses various cognitive skills with a sequence

of simple tasks that can be scored on a point system. It takes

approximately 10 minutes to administer. See

www.mocatest.org.

Imaging studies and electrophysiology Neuroimaging (usually MRI) should

be performed in every case as part of the search for the underlying

etiology. PET, SPECT,

and EEG can be performed as well.

Laboratory tests Depending on the specific clinical situation and the

suspected causes, targeted laboratory testing

should be performed, including, for example, complete blood count,

electrolytes, hepatic and renal function tests, thyroid hormones,

vitamin B12, folic acid, TPHA test, HIV serology, and CSF

examination.

Differential Diagnosis at the Syndrome Level

The dementia syndrome may be hard to differentiate from certain other

psychopathologic states, especially the following:

-

Nonpathologic cognitive decline

in old age (can be diagnosed on the basis of history

obtained from family members and clinical testing).

-

Depression with severely reduced drive, so-called

depressive pseudodementia

(neuropsychological and psychiatric examination).

-

An isolated neuropsychological

disturbance, especially aphasia, apraxia, and/or

agnosia (clinical testing, neuropsychological

examination).

-

Congenital intellectual

disability, that is, oligophrenia (history).

-

Cognitive impairment by medications or drugs of abuse (history, general

physical examination, laboratory testing).

-

Status epilepticus with

partial complex seizures or absences (EEG).

-

Cognitive impairment due to endogenous psychosis (neuropsychological and

psychiatric examination).

General Aspects of Treatment

Cause-directed treatment If the dementia syndrome is found to be due to a treatable condition,

cause-directed treatment can be given,

leading to a cure or, at least, the prevention of further progression.

In all other cases, however, dementia responds poorly to treatment, if

at all. The current medications for Alzheimer disease provide only

modest clinical benefit, often at the cost of side effects.

Accompanying manifestations Various manifestations that accompany dementia can be treated symptomatically, with major benefit to the

patient and his or her family, including depression, delusions,

insomnia, and agitation. Training of (temporarily)

preserved cognitive abilities is also advisable to keep the

patient functionally independent for as long as possible.

Nursing care In advanced stages of disease, patients often require home nursing visits, or care in a suitable day clinic; removal from the home to a permanent

care facility should be deferred for as long as this is practically

achievable. The patient’s family is an important component of treatment.

Family members should receive early and thorough information about the

patient’s disease and, where appropriate, counseling in the ways they

can help care for the patient.

6.12.2 Alzheimer Disease (Senile Dementia of Alzheimer Type)

Alzheimer disease is the paradigmatic example of cortical

(as opposed to subcortical) dementia, with dementia itself as the main

clinical manifestation. It is the most common cause of dementia in the

elderly.

Synonyms

Senile dementia of Alzheimer type; Alzheimer dementia.

Epidemiology Women are more commonly affected than men, and the prevalence rises

with age. The mean age at the onset of Alzheimer disease is 78 years.

Persons under age 65 with the disease are said to have “presenile

dementia.”

Etiology and genetics

Genetic factors are clearly

contributory, as first-degree relatives of Alzheimer patients are much

more likely to develop the disease than persons with no family history

of it. Yet, as most affected persons have no such history, environmental factors must also play a role. It

seems that the likelihood of developing the disease is higher in persons

of low educational attainment and those whose intellectual abilities are

not regularly put to use; hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and

other brain diseases also increase the risk.

Genetics Hereditary cases of Alzheimer

disease (which are often early-onset cases) are associated with defects

in:

-

Chromosome 21q, which contains the amyloid precursor protein

(APP) gene.

-

Chromosome 14: mutation of the presenilin-1 gene.

-

Chromosome 1: mutation of the presenilin-2 gene.

Familial clustering of Alzheimer

disease is associated with defects in:

Persons with trisomy 21 (Down

syndrome) are generally demented after age 30 years.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

The neuropathologic lesion in Alzheimer disease

consists of neuronal loss in the cerebral

cortex, particularly in the basal

temporal lobe (hippocampus) and the temporoparietal region. Histologic examination reveals

cell necrosis and an accumulation of

neuritic (“senile”) plaques and Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles. Amyloid angiopathy is often present as

well.

Amyloid and tau protein deposition In Alzheimer disease, degradation of the membrane protein

APP (amyloid precursor protein) leads to the increased production of a

neurotoxic protein called β-amyloid (more

precisely, Aβ1–42, which is longer than the physiologic degradation

product). This pathologic protein forms perivascular

deposits and cortical amyloid

plaques. In addition, hyperphosphorylated tau protein also accumulates within neurons in Alzheimer fibrils and tangles. Amyloid and tau

protein deposition has multiple consequences:

-

Neuron degeneration, mainly

temporobasal (hippocampal) and temporoparietal.

-

Axon degeneration and loss of synapses.

-

A cholinergic deficit in the cerebral

cortex.

-

In the late stage of the disease, immune

reactions of glial cells to plaques, resulting in

further cell loss.

Cholinergic deficit Neuron degeneration is regularly seen in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, which sends a diffuse

cholinergic projection to the frontal cortex. This and the diminished amount of acetylcholine found in the

brain of persons with Alzheimer disease suggest that the cholinergic system plays a role in the

pathogenesis of the disease. These observations provide the motivation

for treatment with cholinergic drugs (as described later).

Clinical Features, Course, and Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical features and course The nonspecific early manifestations

can include depression, insomnia, agitation, anxiety, and excitability.

Early signs of dementia include impairments of memory, word-finding ability,

and spatial orientation.

Persons who have a demonstrable memory deficit that impairs their

performance of complex everyday tasks (but not of simpler ones) are said

to have “mild cognitive impairment.” This can be an early manifestation

of Alzheimer disease.

Within a year, patients manifest gradually

worsening forgetfulness,

fatigability, poor concentration, and

lack of initiative. Nonetheless, motor

functioning, including erect body posture, remains normal for a long time,

so that the superficial appearance of good health is preserved.

There are often also focal neuropsychological

deficits such as aphasia, apraxia, impaired temporal and spatial

orientation, and the applause sign (described in

section ▶ 5.5.1). The patient loses the ability to

think abstractly or grasp complex situations, and confusion, lack of

interest, and the progressive loss of language ultimately lead to the loss of functional independence and the need for nursing care.

Diagnostic evaluation Early recognition and interpretation of the psychopathologic

deficits described earlier is crucial for the diagnosis of the

disease.

Often, the diagnosis is further supported by typical neuroimaging findings (MRI: cortical brain atrophy, especially in the temporal lobe, and

ventriculomegaly; see ▶ Fig. 6.61).

Neuroimaging is also mandatory because it can rule out some of the other

causes of the dementia syndrome (cf. ▶ Table 6.39).

Further studies (hematologic biochemical, and serologic

blood tests, CSF examination, EEG) may be indicated, depending on

the specific differential diagnostic considerations in the individual

patient.

A differential diagnostic overview of the main clinical and radiologic

features of Alzheimer disease and other conditions resembling it is provided

in ▶ Table 6.40.

Table 6.40 Distinguishing features of different

types of dementia

|

Alzheimer dementia

|

Lewy body dementia

|

SAE (vascular dementia)

|

Frontotemporal dementia (Pick disease)

|

|

Type of dementia

|

Cortical

|

Both cortical and subcortical

|

Subcortical

|

Frontal

|

|

Main cognitive

manifestations

|

Disturbance of recent memory, visuospatial orientation,

word-finding

typical: normal “façade”

|

Combined manifestations of cortical and subcortical

dementia

|

Slowing, forgetfulness, impaired concentration and

drive

|

Personality change, loss of drive, sometimes

aphasia

|

|

Accompanying neurologic or other bodily

manifestations

|

Sometimes hyposmia, otherwise no particular bodily

manifestations at first

physical impairment, only in the late stage

|

Fluctuating attention and wakefulness, visual

hallucinations, parkinsonism

|

Increased muscle tone, hypokinesia, small-stepped and

broad-based gait (lower-body parkinsonism), dizziness,

falls, sometimes TIAs, urinary incontinence

|

Early urinary incontinence, sometimes parkinsonism

|

|

Mental disturbances

|

Depression, later restlessness, anxious agitation,

paranoia, insomnia

|

Insomnia, visual hallucinations, delusions

|

Sometimes depression, irritability, “lazy” speech

|

Variable; personality change, abnormal behavior,

progressively “lazy” speech

|

|

Neuroimaging

|

CT, MRI: cortical brain atrophy, ventriculomegaly

|

SPECT, PET: low dopaminergic activity in occipital

lobes

|

CT, MRI: marked SAE lesions and multiple lacunar

infarcts

|

CT, SPECT, PET: frontal hypoperfusion and

hypometabolism

|

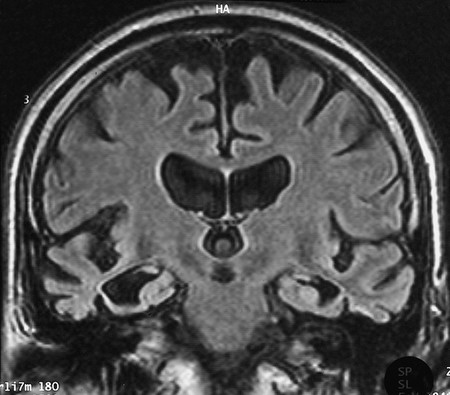

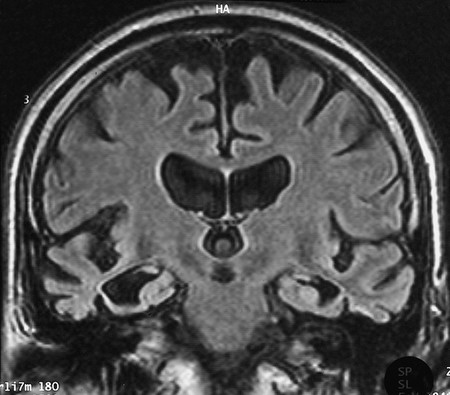

Fig. 6.61 Brain atrophy in

dementia. High-grade, symmetric, mainly frontal atrophy

of the cerebral hemispheres in a 64-year-old man. Note the marked

atrophy of the temporal lobes as well. The lateral ventricles,

including the temporal horns, are markedly dilated, as is the third

ventricle. Both external hydrocephalus and internal hydrocephalus

are present (“ex vacuo,” i.e., as a result of brain atrophy).

6.12.3 Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment Cholinomimetic drugs (acetylcholinesterase

inhibitors: donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and antiglutamatergic NMDA-receptor antagonists (memantine) improve

neuropsychological deficits symptomatically but do not halt the progression

of dementia.

A possible beneficial effect of acetylsalicylic acid is currently being

studied, as patients with Alzheimer disease often have concomitant

small-vessel disease as a contributory cause of dementia.

No clear benefit has been shown for high-dose vitamin E, Ginkgo biloba preparations, calcium antagonists, or

nootropic drugs (= drugs that putatively improve brain performance), such as

piracetam.

The most important aspect of treatment in all patients is the management

of the accompanying manifestations:

-

Depression (preferably with selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

-

Psychosis (preferably with clozapine or

olanzapine).

-

Insomnia, agitation, and aggressiveness

(preferably with low-potency neuroleptic agents such as pipamperone,

melperone, and clomethiazole).

Patients with advanced Alzheimer disease, and their families, can benefit

from referral to special outpatient and day care

facilities.

Prognosis Alzheimer disease always progresses.

The average life expectancy from the time of diagnosis is 8 to 9

years.

6.12.4 Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Epidemiology Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia after

Alzheimer disease, but the second most common neurodegenerative dementing

disease is Lewy body dementia.

Lewy body disease overlaps with Parkinson

disease (section ▶ 6.9) in

its neuropathologic and clinical features but differs in having dementia

as a prominent early manifestation, appearing at the same time as the

motor disturbances or even before them.

Pathology The neuropathologic hallmark of this disease is the presence of Lewy inclusion bodies (deposits of α-synuclein) in the neurons of the cerebral cortex and

brainstem.

Clinical features In these patients, progressive dementia (of a

combined cortical and subcortical type; cf. ▶ Table 6.38) is

accompanied by certain other characteristic findings: there are fluctuating deficits of attention and concentration,

as well as frequent, objective visual

hallucinations and motor parkinsonism

(particularly in patients with early disease onset). Patients often suffer

from repeated falls, syncope, brief episodes of unconsciousness, and

hallucinatory experiences.

Diagnosis and treatment

-

SPECT and PET reveal diminished perfusion and metabolism in the

occipital lobes.

-

An L-DOPA challenge test may alleviate motor parkinsonism in

patients with this disease (although it often does not), while

tending to intensify the hallucinations. Neuroleptic drugs make all

manifestations worse.

-

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can improve both dementia and

hallucinations.

6.12.5 Frontotemporal Dementia (Pick Disease)

Classification Frontotemporal dementia (Pick disease) is the

commonest type of focal cortical atrophy. The

dementing diseases belonging to this category, all of them much rarer than

Alzheimer disease, are characterized by localized atrophy

of circumscribed areas of the cerebral cortex. They are

classified among the system atrophies. Histopathologic examination reveals

gliosis and spongiform

changes.

Aside from frontotemporal dementia, focal cortical atrophy

can also be of the following kinds:

-

In primary progressive aphasia, the

language disturbance may precede the development of generalized

dementia by several years.

-

In posterior cortical atrophy,

dementia may be accompanied by the specific neuropsychological

deficits of Gerstmann syndrome (see

section ▶ 5.5.1,

▶ 5.5.1.4).

Frontotemporal dementia is also classified by some authors as a type of

frontal lobe degeneration.

Etiology and epidemiology Some cases are hereditary, with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

Most patients are less than 65 years old; in this age group, frontotemporal

dementia is, in fact, nearly as common as Alzheimer disease. Overall,

however, the focal cortical atrophies account for only approximately 5% of

all cases of dementia.

Clinical features See also ▶ Table 6.40. Patients with frontotemporal dementia often

manifest frontal personality changes and abnormal

social conduct (see section ▶ 5.5.1).

They may have reduced drive, aphasia, and

difficulty initiating speech, as well as an affect disturbance. The type of

cognitive deficit depends on the particular area of cerebral cortex that is

affected. Patients often develop urinary

incontinence early in the course of this disease.

6.12.6 Vascular Dementia: SAE-Associated Dementia and Multi-Infarct

Dementia

SAE stands for subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy. On this topic,

see also the discussion of lacunar infarction in

section ▶ 6.5.6.

Etiology and epidemiology Vascular dementia, the second most common etiologic category of dementia,

is caused either by multiple subcortical lacunar infarcts due to cerebral

microangiopathy (SAE) or, less commonly, by multiple cortical and

subcortical infarcts due to macroangiopathy or

recurrent embolic stroke (multi-infarct

dementia). These two mechanisms often operate in combination. The site and

extent of the infarcts determine the severity and rate of progression of the

dementia syndrome.

Clinical features See ▶ Table 6.38.

Vascular dementia often strikes patients with preexisting

arterial hypertension and/or other vascular

risk factors. There may be a history of transient neurologic deficits in the past, due to TIAs or minor

strokes. Dementia can arise suddenly or progress in

spurts. There may be accompanying neuropsychological deficits, such as

aphasia, as well as marked incontinence of affect: involuntary laughing and

crying are common. The neurologic findings include

enhanced perioral reflexes, signs of pseudobulbar palsy (e.g., dysarthria

and dysphagia), a tripping, small-stepped gait (old person’s gait, “marche à

petits pas”), and, sometimes, pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs. The psychopathology of subcortical vascular dementia

includes apathy, depression, and slowness. Patients can recall old

information more easily than they can store new information.

Diagnostic evaluation Neuroimaging reveals brain atrophy and evidence of multiple focal lesions, often old lacunar infarcts; these are

usually found in the subcortical white matter

( ▶ Fig. 6.62).

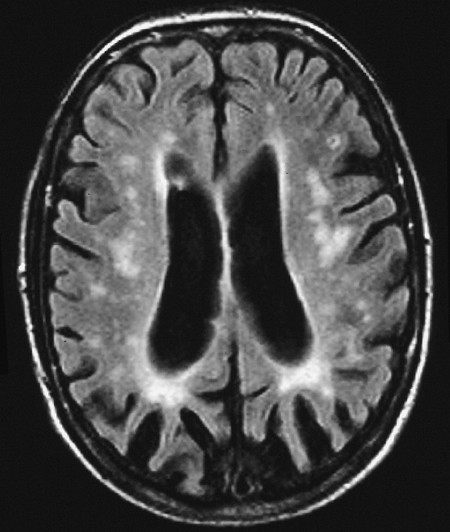

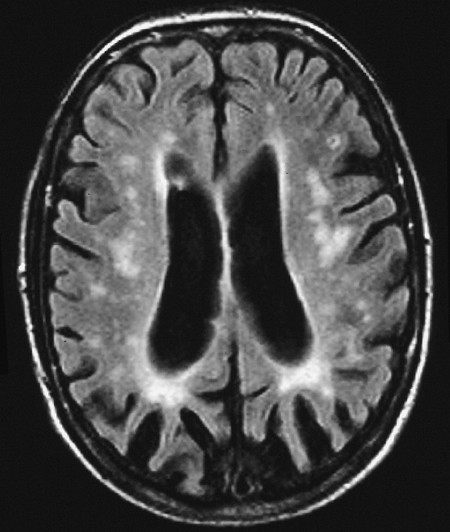

Fig. 6.62 Vascular

encephalopathy as seen by MRI. There are multiple focal

signal abnormalities in the deep white matter, the subcortical

region, and the cerebral cortex. The ventricles and subarachnoid

space are dilated (“hydrocephalus ex vacuo”).

Treatment The intermediate goal of treatment is vascular risk

reduction (treatment of arterial hypertension, cardiac

arrhythmias, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia, if present;

inhibition of platelet aggregation with aspirin and/or other to lower the

risk of thrombosis). Generally speaking, the treatment is the same as that

discussed earlier for the prevention of ischemic stroke

(section ▶ 6.5.9). The symptomatic and supportive

measures are the same as for Alzheimer disease: cholinomimetic drugs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and

the antiglutamatergic drug memantine alleviate the

cognitive disturbances.

Course and prognosis Vascular dementia is a progressive illness, typically with stepwise

progression. The rate of progression is variable, however, as it depends on

the type and extent of the underlying arteriopathy.

6.12.7 Dementia due to Malresorptive Hydrocephalus

Synonym This disorder is often incorrectly called (idiopathic or secondary) normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Epidemiology The peak incidence is between the ages of 50 and 70 years.

Etiology This disorder can arise in the aftermath of meningitis, aneurysmal or

traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, or venous sinus thrombosis; as a

consequence of elevated CSF protein concentration; or spontaneously, that

is, without any known risk factor. The common pathophysiologic mechanism is

impaired CSF outflow through the arachnoid

granulations and nerve root pouches, leading to a buildup of CSF

and ventricular dilatation (see ▶ Fig. 6.2).

Clinical features The classic clinical triad of malresorptive hydrocephalus includes a progressively severe gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and psycho-organic syndrome. Neurologic examination reveals

paraparesis, ataxia, impaired memory, and, in advanced stages, dementia. Some patients also have headache.

Diagnostic evaluation CT or MRI characteristically reveals enlarged lateral ventricles, while the subarachnoid

space appears tight ( ▶ Fig. 6.2c). The CSF pressure

measured via LP is normal or, at most, mildly

elevated (hence the alternative name of this condition, “normal pressure

hydrocephalus”).

The removal of CSF via LP can bring about prompt, but transient,

improvement of the patient’s gait and memory. The “sticky” and

small-stepped gait can suddenly become much more fluid. A good response

to CSF removal (the “CSF tap test”) supports the diagnosis of

malresorptive hydrocephalus and implies a likely benefit from treatment

with a shunt (see later).

Treatment If the patient responds well to the CSF tap test, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is neurosurgically implanted. This

generally leads to an improvement of the symptomatic triad.