6.9 Parkinson Disease and Other Hypertonic–Hypokinetic Syndromes

The common feature of diseases of the basal ganglia is a

movement disorder in which there is either too much or too little movement,

that is, an excess or deficiency of movement impulse, movement automaticity,

and/or muscle tone (see section ▶ 5.5.2).

In general, such diseases are characterized by the following:

-

Disturbances of the process or movement (always).

-

Abnormally increased or diminished muscle tone (usually).

-

Involuntary movements (often).

-

Associated neuropsychological manifestations (sometimes).

Increased muscle tone is often associated with paucity of

movement, and, conversely, diminished muscle tone with excessive movement. Thus, there are two main classes of

extrapyramidal syndrome:

-

Hypertonic–hypokinetic extrapyramidal

syndromes (above all, parkinsonian syndromes and related

neurodegenerative disorders, which will be discussed in this

section).

-

Hypotonic-hyperkinetic extrapyramidal

syndromes (e.g., chorea, athetosis, ballism, and dystonia,

which will be discussed in the next section).

6.9.1 Overview

In hypertonic–hyperkinetic syndromes, elevated muscle tone is

typically manifest as rigidity. Paucity of

movement, depending on its severity, is termed either hypokinesia (= diminished movement) or akinesia (= complete lack of movement). A third so-called

“cardinal manifestation,” tremor, is also

commonly present. This clinical triad, called the parkinsonian syndrome (or parkinsonism), is typically found

in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Often, postural instability (= tendency to fall) occur as a fourth cardinal

manifestation.

Parkinson disease, however, is only

one possible cause of parkinsonism; there are many others besides.

Parkinsonism may be due to an underlying illness or condition other than

idiopathic Parkinson disease (symptomatic parkinsonian

syndromes). In addition, several systemic

neurodegenerative diseases cause parkinsonism. These rare

diseases are marked by a loss of neurons not only in the basal ganglia, but

also in other areas of the CNS, and thus are clinically characterized not

only by extrapyramidal manifestations, but also by neurologic deficits

localizable to other regions of the brain. The most important diseases in

this category, multisystem atrophy (MSA) and corticobasal degeneration

(CBD), will be discussed further in this chapter. Lewy body dementia belongs

in this category as well but will be discussed later in the subsection on

dementia (section ▶ 6.12).

6.9.2 Parkinson Disease (Idiopathic Parkinson Syndrome)

Definition Parkinson disease is defined by its clinical manifestations

(characteristic body posture and gait, with hypokinesia, rigidity, and,

usually, rest tremor) and their pathologic correlates in the brain: Lewy

bodies containing α-synuclein and degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in

the pars compacta of the substantia nigra (a pigmented nucleus in the

midbrain).

Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

Epidemiology and etiology Parkinson disease has an overall prevalence of 0.15%. Its age-specific

prevalence rises with increasing age, to 1% in persons older than 60

years and 3% in persons older than 80 years. Most cases are idiopathic, that is, without

any identifiable cause.

Familial clustering of Parkinson

disease is seen in 5 to 15% of cases (so-called hereditary Parkinson disease); patients who develop

Parkinson disease at an unusually young age are

particularly likely to have a problem of this type. To date, 18 genetic

loci (PARK1 through PARK18) and at least 7 genes have been identified

whose mutations can cause a hereditary parkinsonian syndrome. The mode

of inheritance can be autosomal dominant with variable penetrance or

autosomal recessive. A special type is the familial Parkinson–dementia

complex seen on the island of Guam. The combination of parkinsonism and

dementia also sometimes exhibits familial clustering.

Pathogenesis The neuropathologic hallmark of idiopathic Parkinson

disease is degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons of

the substantia nigra and the locus

ceruleus. Hyaline inclusion bodies, called Lewy bodies, are found within the degenerated neurons. The

loss of dopaminergic neurons leads to a degeneration

of the (inhibitory) nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway and,

therefore, to dopamine deficiency in the

striatum. This, in turn, leads to enhanced activity of the

striatal glutamatergic neurons, which produces the clinical

manifestations of the disease.

In the Braak system of

Parkinson disease there are six neuropathologic

stages that trace the temporal progression of

intraneuronal Lewy body formation from lower to higher neural

centers in the brain. In stages 1 and 2, before any clinical

manifestations of the disease have arisen, Lewy bodies are present

only in certain areas of the brainstem and the olfactory system. The

first symptoms arise in stages 3 and 4 when Lewy bodies begin to

appear in the substantia nigra. Finally, in stages 5 and 6, Lewy

bodies are found in diffuse areas of the cerebral cortex.

Clinical Features

The clinical picture of idiopathic Parkinson disease and of hereditary

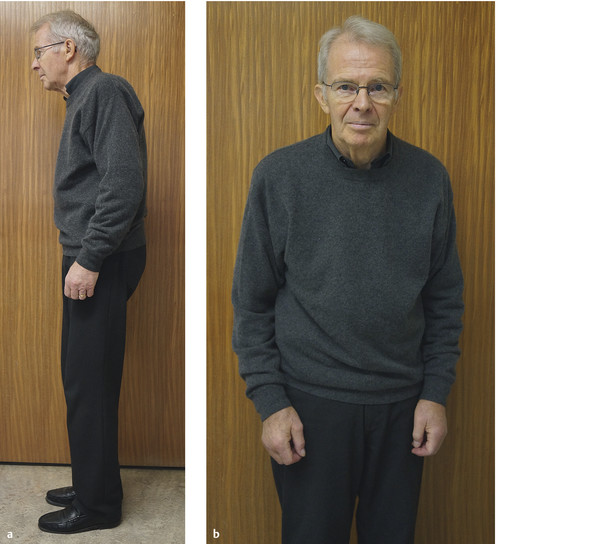

parkinsonian syndromes ( ▶ Fig. 6.55) is typically characterized by:

-

Hypokinesia, i.e., slowing of

movement.

-

Increased muscle tone

(rigidity).

-

Abnormal body posture (stooped head

and trunk, flexion at the knees).

-

Impaired postural reflexes, sometimes

leading to falls.

-

Often tremor.

-

Later, neuropsychological deficits

and certain vegetative/autonomic

disturbances such as oily (seborrheic) face and

bladder dysfunction.

The motor signs are often only unilateral, or more marked on one

side, when the disease first appears. They can be aggravated by

emotional stress.

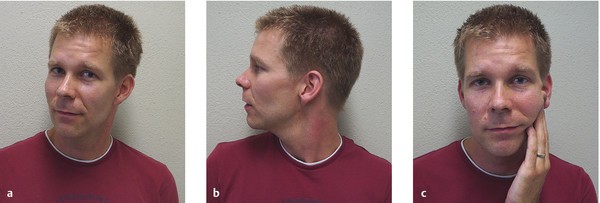

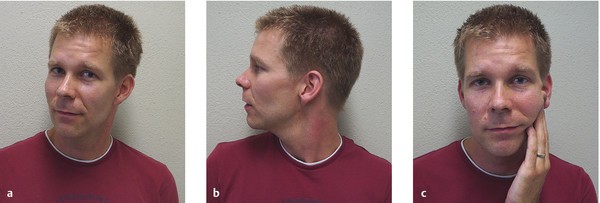

Fig. 6.55 Parkinson

disease. (a) Typical posture

with stooped head and upper body and lightly flexed elbows,

hips, and knees. (b) Hypomimia (paucity

of facial expression) and the asymmetry of manifestations that

is typical in idiopathic Parkinson disease (the right elbow is

somewhat more strongly flexed than the left).

Hypokinesia Hypokinesia manifests itself as paucity

of facial expression (mask-like facies), reduced frequency of blinking, and speech

disturbances (dysphonia, i.e., slow, monotonous, unmodulated

speech, and repetitions). There is little spontaneous movement, and the

normal accessory movements (e.g., arm swing during walking) are

diminished or absent. The patient’s handwriting becomes progressively

smaller (micrographia). Repeated or alternating

movements (e.g., finger-tapping) are performed slowly and with smaller

excursions (dysdiadochokinesia; cf. ▶ Fig. 3.19). Axial

movements, such as turning around while standing or turning over in bed,

are difficult to perform. Very severe hypokinesia is sometimes called

akinesia.

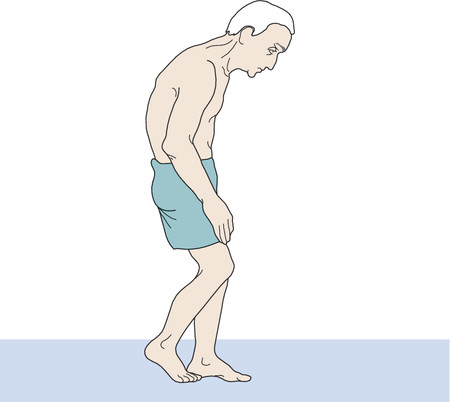

Gait A parkinsonian gait is characterized by a mildly stooped posture, with the head jutting forward,

and a small-stepped, often

shuffling gait, without accessory arm

movements ( ▶ Fig. 6.56). To turn around while standing, the

patient makes many small turning steps.

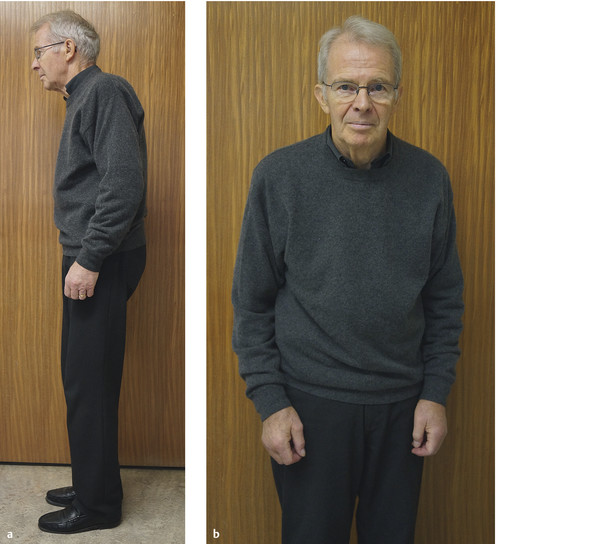

Fig. 6.56 Typical

parkinsonian posture while walking: inclined head,

slightly stooped upper body, flexed elbows, and lightly flexed

hips and knees.

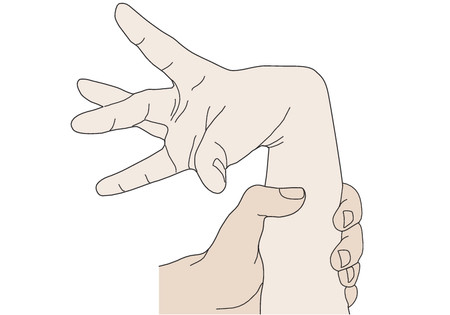

Increased muscle tone This is primarily evident as rigidity ( ▶ Fig. 3.24), felt by the

examiner during large-amplitude, passive flexion and extension of the

joints. Rigidity is sometimes easier to detect when the patient

voluntarily contracts the muscles on the opposite side of the body.

Often, during passive movement, the examiner may feel a small, brief,

periodically recurring diminution of muscle tone, known as the cogwheel phenomenon, which is usually most

evident at the wrist ( ▶ Fig. 3.25). The patient’s

postural tone, too, is elevated; if, for

example, the head is lifted off the bed and let go, it may remain

suspended in midair for some time (the Wartenberg sign; the classic

literature spoke of a “coussin psychique,”

i.e., a virtual pillow).

Another test for the objectification of rigidity is the

so-called swinging test: the examiner grasps and shakes the

patient’s forearm back and forth. Rigidity markedly diminishes the

swinging (pendular) motion of the wrist. The test can also be

performed at the elbow or knee joint.

Tremor Three-quarters of patients with Parkinson disease have

tremor sooner or later in the course of their disease, typically a distal rest tremor at a frequency of 5 Hz. A

pronation–supination (“pill-rolling”)

tremor is highly characteristic. The tremor is present at

rest and generally disappears on voluntary movement; it is sometimes

increased by mental exertion, deep concentration, or walking. Some

patients have postural and intention tremor in addition to rest tremor (see

▶ Fig. 3.22).

The risk of falling An impairment of postural

reflexes, combined with hypokinesia, has the consequence that

changes of body posture and orientation in space can no longer be

compensated for by reflexive, rapid corrective movements. The most

obvious manifestations of this problem are pro- and

retropulsion. If the patient is pushed while standing still,

or stumbles over an obstacle, the movements made to regain balance are

too small and too slow, and a fall may

result.

The patient’s postural reflexes and possible tendency

to fall can be tested with the pull test and the push-and-release

test. In the former, the examiner stands behind the patient and

pulls back on both shoulders; in the latter, the patient is propped

up in a standing position from behind by the examiner’s hands, which

are then suddenly released. (Obviously, when performing these tests,

the examiner must make sure that the patient can be caught in case

of a fall.)

Impaired olfaction An impaired sense of smell is almost universal in patients

with idiopathic Parkinson disease but rare in patients with symptomatic

parkinsonism.

neuropsychological deficits When the first symptoms of Parkinson disease arise, the

patient’s cognitive functions are generally normal or only mildly

impaired. As the disease progresses, however, neuropsychological

deficits almost always arise. Memory is impaired, cognitive processes

are slowed (bradyphrenia), and there is a tendency toward perseveration.

Rapid changes in thought content are difficult to achieve, and the

planning and execution of actions and behaviors is impaired (so-called

dysexecutive syndrome).

Psychiatric manifestations Depression affects one-third to one-half of all patients

over the course of the disease and is treatable. Isolated apathy

(without depression) can also arise. Impulse-control disorders, such as

compulsive shopping, gambling, or hypersexuality, are usually side

effects of dopaminergic drugs. The patient’s perceptions and thought

processes can become abnormal over the course of the disease, because of

either the disease itself or its dopaminergic treatment; hallucinations

and overt psychoses can result.

Disturbances of autonomic and vegetative function Such disturbances arise partly as a by-product of

hypokinesia and partly because of direct involvement of the autonomic

nervous system. These include seborrhea (an

oily face, caused by excessive fat production in the skin),

hypersalivation, cold intolerance, a tendency toward orthostatic hypotension and constipation, urinary urgency

(possibly causing incontinence), and sexual dysfunction (altered libido,

erectile dysfunction). Insomnia and

behavioral disturbances during REM sleep (see

section ▶ 10.4) are often seen

early on in the course of disease; the patient’s sleep can also be

disturbed by restless legs syndrome (see

section ▶ 10.2.2) or spontaneous

pain in the limbs.

The nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson disease are summarized in

▶ Table 6.30.

Table 6.30 Nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson

disease

|

Autonomic/vegetative

|

Cognitive

|

Psychiatric

|

-

Hyperhidrosis

-

Hypersalivation

-

Seborrhea

-

Obstipation

-

Cold intolerance

-

Circulatory dysregulation, orthostatic

hypotension

-

Sexual dysfunction (loss of libido, abnormally

increased libido, erectile dysfunction)

-

REM-sleep behavioral disorder

-

Insomnia

-

Daytime somnolence, sleep attacks

-

Pain, paresthesiae

-

Hyposmia, anosmia

|

-

Slowed thinking (bradyphrenia)

-

Perseveration

-

Impaired planning, strategy, and execution

(dysexecutive syndrome)

-

Cognitive impairment, ranging from mild to

severe frontal dementia in advanced disease

|

-

Depression

-

Apathy

-

Hallucinations, illusions

-

Psychosis (mainly as a drug effect)

-

Impulse-control disorder (compulsive shopping,

gambling, or sexual behavior; mainly as a drug

effect)

|

Classification and grading of manifestations The manifestations described are present to variable

extents in different patients with Parkinson disease. Generally

speaking, the disease has three main clinical variants:

-

The akinetic-rigid type (without

tremor).

-

The tremor-dominant type (with little

hypokinesia and rigidity).

-

The mixed or “equivalence” type (with

roughly equal severity of all three cardinal

manifestations—rigidity, hypokinesia, and tremor).

Individual clinical manifestations can be graded on

pseudoquantitative scales, if this is desired for long-term follow-up or

for research purposes, for example, with the Webster

Rating Scale ( ▶ Table 6.31) or the very detailed Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), which is

not reproduced here. Cognitive function can be assessed with the MOCA

test or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; see

▶ Table 3.11).

Table 6.31 Simplified scale for evaluating the

severity of individual signs of Parkinson disease

|

1. Bradykinesia of hands, including handwriting

|

0 = normal

1 = mild slowing

2 = moderate slowing, handwriting severely

impaired

3 = severe slowing

|

|

2. Rigidity

|

0 = none

1 = mild

2 = moderate

3 = severe, present despite medication

|

|

3. Posture

|

0 = normal

1 = mildly stooped

2 = arm flexion

3 = severely stooped; arm, hand, and knee

flexion

|

|

4. Arm swing

|

0 = good bilaterally

1 = unilaterally impaired

2 = unilaterally absent

3 = bilaterally absent

|

|

5. Gait

|

0 = normal, turns without difficulty

1 = short steps, slow turn

2 = markedly shortened steps, both heels slap on

floor

3 = shuffling steps, occasional freezing, very slow

turn

|

|

6. Tremor

|

0 = none

1 = amplitude < 2.5 cm

2 = amplitude > 10 cm

3 = amplitude > 10 cm, constant, eating and writing

impossible

|

|

7. Facial expression

|

0 = normal

1 = mild hypomimia

2 = marked hypomimia, lips open, marked

drooling

3 = mask-like facies, mouth open, marked

drooling

|

|

8. Seborrhea

|

0 = none

1 = increased sweating

2 = oily skin

3 = marked deposition on face

|

|

9. Speech

|

0 = normal

1 = reduced modulation, good volume

2 = monotonous, not modulated, incipient dysarthria,

difficulty being understood

3 = marked difficulty being understood

|

|

10. Independence

|

0 = not impaired

1 = mildly impaired (dressing)

2 = needs help in critical situations, all activities

markedly slowed

3 = cannot dress him- or herself, eat or walk

unaided

|

The Neurologic Examination and Other Diagnostic

Tests

The diagnosis of Parkinson disease is based on the typical

clinical manifestations and characteristic

findings on neurologic examination.

History Important points to be addressed in clinical history-taking include

the following:

-

Has the patient had difficulty with fine motor activities such

as writing, getting dressed, or eating?

-

Is the patient’s gait less steady than before, perhaps with

stumbling or falls?

-

Has the patient noticed any difference between the right and

left sides of the body?

-

Does the patient suffer from pain or disturbed sleep?

-

Has there been any impairment of the sense of smell or any

difficulty swallowing?

Neurologic examination In addition to hypokinesia, rigidity, tremor, and propulsion/retropulsion, the examination generally reveals

the following:

-

Weak convergence (movements to focus

the eyes are slowed).

-

A persistent glabellar reflex (i.e.,

lack of habituation of the reflex after repeated glabellar

tapping).

-

Saccadic ocular pursuit

movements.

-

Impaired olfaction.

The intrinsic muscle reflexes are normal, however, as are all

somatosensory modalities.

For numerical grading, see the preceding paragraphs and

▶ Table 6.31.

Imaging studies CT and MRI of the head reveal no abnormalities and are generally

performed only to rule out competing diagnoses, for example, symptomatic

parkinsonian syndromes. The loss of dopaminergic

afferent input to the striatum can be demonstrated with positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography

(SPECT) after the administration of 18fluorodopa

( ▶ Fig. 6.57). Cerebral

ultrasonography can reveal early changes in the substantia nigra.

Fig. 6.57 An

18F-DOPA-PET scan in a normal person (left,

top and bottom) and in a patient with incipient Parkinson

disease, worse on the left side of the body (right, top and

bottom). The basal ganglia are seen in axial and

coronal section (upper and lower rows of images, respectively).

The patient with Parkinson disease has a more than 20% reduction

in the activity of dopamine decarboxylase in the right putamen

(particularly in its dorsal aspect), with relatively normal

activity in the caudate nucleus. (Image provided courtesy of Dr.

F. Jüngling, PET/CT-Zentrum NW-Schweiz, St. Claraspital, Basel,

Switzerland.)

Idiopathic Parkinson disease is always a diagnosis of exclusion,

that is, all varieties of symptomatic parkinsonism must be ruled out before this diagnosis can be

made.

Testing of olfaction Impairment of the sense of smell early on in the course of

disease is supporting evidence for idiopathic or genetically triggered

Parkinson disease. Smell is tested with small samples of various

substances (coffee, etc.).

Genetic testing In young patients with a positive family history, genetic

testing can help secure the diagnosis and enable a more accurate

prognosis.

Treatment, complications, and prognosis Effective treatment alleviates the manifestations of the

disease, moving the symptomatic progression curve to the right by some 3

to 5 years, but does not affect the disease process as such. The

putative early neuroprotective effect of

certain antiparkinsonian drugs has not yet been confirmed.

Pharmacotherapy The goal of drug therapy is to replace

the missing dopamine in the striatum.

The most important antiparkinsonian drug is still levodopa (L-DOPA), which is metabolized to

dopamine in the CSF. At the beginning of treatment, only small doses

are needed to alleviate the clinical manifestations; later on,

however, higher doses are needed, and side effects such as

dyskinesia and on–off motor fluctuations commonly arise. Therefore,

efforts are often made to delay the administration of L-DOPA to

younger patients by giving alternative drugs first.

-

MAO-B inhibitors are

increasingly used as drugs of first choice because of their

putative neuroprotective effect. These include selegiline and

rasagiline (a long-acting selegiline derivative). They inhibit

the degradation of dopamine to homovanillic acid and thereby

ameliorate parkinsonian manifestations.

-

Amantadine, an

NMDA-receptor antagonist, is sometimes used very early in the

course of disease; it is thought to enhance dopamine release

from nerve terminals.

-

If these agents are no longer sufficiently

effective, nonergot dopamine agonists

(e.g., ropinirole, pramipexole, or rotigotine) can be used in

younger patients; their effectiveness, however, matches that of

L-DOPA only in the early stages of the disease.

-

In older patients, L-DOPA

is used from the outset. This agent, unlike dopamine itself,

crosses the blood–brain barrier; it is converted to dopamine in

the CSF.

-

L-DOPA is always given in combination with a decarboxylase inhibitor (e.g., benserazide [HCl] or carbidopa) to prevent its premature degradation in

the periphery.

-

The combination of L-DOPA with a COMT inhibitor, such as entacapone or tolcapone,

can further increase dopamine bioavailability. Tolcapone,

however, is occasionally hepatotoxic and is therefore reserved

for otherwise intractable cases. Entacapone is sold as a

combination drug together with L-DOPA and a decarboxylase

inhibitor.

-

Anticholinergic drugs,

such as biperiden, are mainly effective

against tremor. Note: their

anticholinergic effect can also induce or worsen confusion

and/or dementia.

The following should be borne in mind as rules of thumb

for the dosing of antiparkinsonian drugs, particularly

L-DOPA:

Drug side effects and complications Prolonged treatment with L-DOPA and other antiparkinsonian

drugs can cause several problems:

-

Fluctuations in drug effect (on–off

fluctuations, end-of-dose akinesia) can often be

improved by the use of sustained-release L-DOPA preparations,

division of the daily dose into smaller individual doses at more

frequent intervals (perhaps with the use of water-soluble L-DOPA

preparations), and/or the addition of dopamine agonists or COMT

inhibitors. Water-soluble L-DOPA takes effect very rapidly and

can shorten off-phases or prevent imminent off-phases. Deep

brain stimulation is another therapeutic possibility (see

later).

-

Drug-induced dyskinesias,

for example, peak-dose dyskinesia or

hyperkinesia (often involving

choreiform involuntary movements; see

section ▶ 6.10), are

seen in 40% of patients after 6 months of L-DOPA treatment, in

60% after 2 years, and in nearly all after 6 years. They are

usually more disturbing to patients’ families than to the

patients themselves, but they can be disabling if severe and may

be untreatable except by deep brain stimulation.

-

Painful foot dystonia can

be managed with the use of sustained-release preparations in the

evening and perhaps with apomorphine injections.

-

“Freezing,” that is,

sudden arrest of movement, is not directly related to the serum

concentration of L-DOPA. Various mental techniques can help

(carrying a briefcase, stepping over real or imagined obstacles,

etc.).

-

Psychosis and other

psychiatric disturbances (e.g., hypersexuality, illusions,

hallucinations, delusions, compulsive gambling, food cravings)

usually arise as side effects of drugs, especially dopamine agonists (ropinirole,

pramipexole). They may respond to a reduction of the dose or to

the addition of an atypical neuroleptic drug (clozapine,

risperidone).

-

An akinetic crisis is a

prolonged phase of extreme rigidity causing complete immobility and accompanied by hyperthermia,

hyperhidrosis, other autonomic disturbances, and dysphagia. Such

crises can be precipitated, for example, by abrupt

discontinuation of antiparkinsonian drugs, errors in drug-taking

or drug-prescribing, the use of neuroleptic drugs, surgical

procedures, or infection. They can be treated with water-soluble

L-DOPA (given by nasogastric tube), amantadine (by intravenous

infusion), or apomorphine (by subcutaneous injection).

-

Further side effects that can be induced by any

dopaminergic drug include nausea

(especially at the beginning of treatment; it can be

counteracted with an antiemetic dopamine antagonist that has a

purely peripheral effect, such as domperidone), fatigue, and

orthostatic hypotension.

Movement disorders that are caused by L-DOPA:

On-dyskinesia (also called peak-dose or

plateau hyperkinesia); choreatiform movements that arise as the

serum L-DOPA concentration increases (see

section ▶ 6.10).

Off-dystonia (also called early-morning

dystonia): painful dystonia, for example, in one or both feet, that

arises as the serum L-DOPA concentration falls.

Deep brain stimulation Neurosurgical treatment, consisting of the stereotactic implantation of stimulating

electrodes into the thalamus (nucleus ventrointermedius),

globus pallidus, or subthalamic nucleus for chronic electrical

stimulation, can markedly alleviate the manifestations of the disease;

its indication depends on their severity and intractability in the

individual patient. Each stimulating electrode has multiple metallic

contacts, at which the intensity, pulse width, and frequency of the

applied current can be independently controlled to optimize the clinical

effect. This method has now largely replaced earlier destructive methods

involving the creation of permanent lesions. It was once considered a

treatment of last resort but is now increasingly used for patients in

intermediate stages of the disease. An overview of the expected effects

of deep brain stimulation in each of the three currently used target

structures is provided in ▶ Table 6.32.

Table 6.32 Current target structures for deep

brain stimulation in the treatment of Parkinson disease, and the

expected effects of stimulation at each structure

|

Target structure

|

Best effect

|

Remarks

|

|

Subthalamic nucleus

|

Reduction of hypokinesia, less frequent and less

intense off-phases

|

The L-DOPA dose can be markedly reduced. Dyskinesia

and tremor improve as well

|

|

Globus pallidus internus

|

Reduction of dyskinesia during on-phases

|

Hypokinesia and rigidity improve as well, but less

than with stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus

|

|

Nucleus ventrointermedius of the thalamus

|

Reduction of tremor

|

Little effect on hypokinesia or dyskinesia

|

Further types of treatment Aside from drugs and surgery, physical

therapy and regular exercise (sports, walking, hiking) can

help improve and maintain mobility. Speech

therapy may be helpful as well.

Moreover, adequate psychological support for

patients and their families is important. Self-help

groups can be valuable in this regard.

Course and prognosis L-DOPA treatment can shift the

symptomatic progression curve to the right by 6 to 7 years. It is hard

to predict which patients will eventually become dependent on the help

of others or on around-the-clock nursing care. This tends to occur after

approximately 20 years of illness.

The tremor-dominant type has a

relatively favorable prognosis. The prognosis is worse for older

patients, men as opposed to women, and patients with severe disease (in

terms of both motor and nonmotor manifestations). Parkinson disease can

shorten the patient’s life span.

Parkinson disease is a progressive disease whose manifestations

can be alleviated by drugs, deep brain stimulation, and

physiotherapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Table 6.33 The differential diagnosis of

idiopathic Parkinson disease

|

Cause of parkinsonism

|

Examples

|

|

Arteriosclerotic

parkinsonism

|

|

|

Drug-induced

parkinsonism

|

-

Neuroleptic agents (most common cause)

-

Antiemetic drugs (mainly dopamine agonists

such as metoclopramide)

-

Lithium

-

Valproic acid

-

Reserpine

-

Calcium antagonists such as flunarizine

|

|

Parkinsonism of infectious

origin

|

|

|

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

(also called malresorptive hydrocephalus)

|

|

|

Toxic parkinsonism

|

-

Carbon monoxide poisoning

-

Manganese poisoning

-

MPTP

(1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, a

by-product of the synthesis of the designer drug

MPPP)

-

Cyanide

-

Methanol

|

|

Trauma

|

|

|

Metabolic diseases

|

-

Hypo- and pseudohypoparathyroidism with basal

ganglionic calcification

-

Idiopathic basal ganglionic calcification,

Fahr disease

|

|

Neurodegenerative diseases

(see also ▶ Table 1.1)

|

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy

-

Multisystem atrophy

-

Corticobasal degeneration

-

Lewy body disease

-

Frontotemporal dementia

-

Alzheimer disease with parkinsonian

manifestations

|

|

Hereditary diseases that can have

prominent parkinsonian manifestations

|

-

Wilson disease

-

Pantothenate kinase–associated

neurodegeneration

-

SCA3 spinocerebellar ataxia

-

Fragile-X-tremor-ataxia syndrome

(FXTAS)

-

Westphal variant of Huntingtonchorea

-

Prion diseases

|

|

Further causes

|

|

Tremor, hypokinesia, and rigidity can also be expressions of diseases

other than Parkinson disease, including symptomatic parkinsonian

syndromes.

The main differential diagnoses of idiopathic Parkinson

disease are: neuroleptic side effects and

other neurodegenerative systemic

diseases causing abnormal movements: Lewy body dementia,

MSA, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), malresorptive hydrocephalus, and subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy.

Neuroimaging now enables the recognition of some of these

entities by their typical MRI findings:

-

Ventricular enlargement in malresorptive hydrocephalus (also

called “normal pressure hydrocephalus”).

-

“Hot-cross-bun” sign in MSA.

-

Midbrain atrophy with the “Mickey Mouse” and/or “hummingbird”

signs, along with frontal atrophy, in PSP.

An overview of these and other differential diagnoses is provided in

▶ Table 6.33.

6.9.3 Symptomatic Parkinsonian Syndromes

There are several clinical conditions that resemble idiopathic

Parkinson disease but have a different underlying cause or pathophysiologic

mechanism. The clue to such a condition may be a history of a precipitating event (e.g.,

intoxication, drug use, trauma, or infection) or a structural abnormality of the basal ganglia or other

brain areas (e.g., multiple arteriosclerotic

changes, hydrocephalus) revealed by CT

or MRI. A further characteristic of symptomatic parkinsonism is its relative resistance to treatment with L-DOPA, in

contrast to idiopathic Parkinson disease, which usually responds very well

to L-DOPA, at least at first. Moreover, some forms of symptomatic

parkinsonism present with symmetric manifestations, while idiopathic

Parkinson disease generally presents asymmetrically.

6.9.4 Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

This disease is also known as Steele–Richardson–Olszewski syndrome.

Etiology and pathology A polymorphism in the tau protein gene (chromosome 17) causes deposition

of an abnormally phosphorylated tau protein in the cells of the basal

ganglia. This “tauopathy,” in turn, leads to cellular degeneration in the

substantia nigra, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, periaqueductal area

of the midbrain, and other brain nuclei.

Clinical features The clinical features of PSP include the following:

-

Paucity of movement.

-

Gait disturbance early in the course of

the disease.

-

Predominantly axial rigidity, often with

a permanently extended cervical spine (head

turned upward).

-

Frequent falls with a tendency to fall

backward.

-

Progressive dementia.

-

Impaired vertical gaze movements (particularly downward), with

nystagmus.

Diagnostic evaluation PSP is diagnosed from its typical clinical features. MRI reveals midbrain atrophy.

Treatment and course This disease presents between ages 50 and 70 years, mainly in men. Its

manifestations tend to respond only weakly to L-DOPA, or not at all. PSP

progresses rapidly and causes death within a few years.

6.9.5 Multisystem Atrophy

This term subsumes a collection of rare diseases

that were previously described as separate entities:

-

Olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA), now

also called MSA-C (cerebellar type).

-

Striatonigral degeneration (SND), now

also called MSA-P (parkinsonian

type).

-

Shy–Drager syndrome (SDS).

-

Mixed forms of these.

Pathology The neuropathologic lesion consists of intracellular inclusion bodies

(with α-synuclein; synucleinopathy) in glial cells as well as cellular

degeneration and gliosis in the substantia nigra, striatum, pons, inferior

olive, and cerebellum.

Clinical features The main clinical features of MSA are present to varying extents in its

different forms of MSA, each of which has its own characteristic initial

presentation:

-

Parkinsonism:

bradykinesia, akinesia, rigidity, and rest

tremor (seen early in the course of MSA-C and

MSA-P).

-

Autonomic dysfunction, including

orthostatic hypotension, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction in

men (seen early in the course of SDS).

-

Ataxia and other cerebellar signs (prominent in OPCA, i.e.,

MSA-C).

-

Pyramidal tract signs such as pathologic

reflexes and spasticity.

-

In some cases, dementia and/or frontal signs.

Diagnostic evaluation These conditions are diagnosed from their clinical

features. The diagnosis of MSA may be supported by an MRI finding of focal brain atrophy, for example,

cerebellar atrophy or a loss of fiber connections in the pons (the

“hot-cross-bun” sign with cross-shaped hypointensity in the pons).

Treatment MSA generally responds poorly to treatment; dopamine agonists tend to be

more effective than L-DOPA. The disease usually leads to severe disability

and death within a few years of onset.

6.9.6 Corticobasal Degeneration

Pathology The neuropathologic lesion in this disease consists of cellular

degeneration and gliosis in the substantia nigra and in the pre- and

postcentral gyri. The cerebral peduncles are correspondingly diminished in

size. Like PSP, CBD is a type of tauopathy.

Clinical features The manifestations of CBD, which are asymmetrically distributed,

include:

-

Impaired fine motor control of an arm

(early in the course of the disease).

-

Progressive rigidity and akinesia.

-

Weakness.

-

Central sensory disturbances.

-

(Sometimes) apraxia.

-

(Sometimes) dystonia.

Treatment and course L-DOPA is generally not very effective and patients usually become

severely disabled within a few years of the onset of the disease.

6.9.7 Lewy Body Dementia

This disease is described later in the section on dementia

(section ▶ 6.12.3).

6.10 Chorea, Athetosis, Ballism, Dystonia: Hyperkinetic Syndromes

These disturbances, unlike Parkinson disease, are characterized

by “too much” movement, often in combination with diminished muscle tone.

The different clinical types of hyperkinesia include chorea, athetosis,

ballism, and dystonia, and mixed forms. Each of these movement disturbances

may be due to a variety of underlying diseases. Thus, the hyperkinetic

extrapyramidal syndroms are a diverse group both in their clinical features

and in their causes.

An overview of the hyperkinetic extrapyramidal syndroms is provided in ▶ Table 6.34. The more

important ones are described in greater detail in the text that follows.

Table 6.34 The diagnostic evaluation of hyperkinetic

extrapyramidal syndromes

|

Syndrome

|

Etiology

|

Remarks

|

|

Chorea: sudden, usually

rapid, distal, brief, irregular involuntary movements;

hypotonia

|

|

Chorea minor

|

Autoimmune; streptococcal infection

|

Often a sequela of streptococcal pharyngitis, most commonly in

girls aged 6 to 13 y

|

|

Chorea mollis

|

Autoimmune; streptococcal infection

|

Hypotonia is prominent

|

|

Chorea gravidarum

|

Third to fifth month of pregnancy

|

Usually during first pregnancy, often with prior history of

chorea minor

|

|

Chorea due to antiovulatory drugs

|

Antiovulatory drugs

|

Rare, reversible with discontinuation of the drug

|

|

Huntington disease

|

Autosomal dominant

|

Onset usually at age 30 to 50 y; associated with progressive

dementia

|

|

Benign familial chorea

|

Autosomal dominant

|

Onset in childhood, no further progression, no dementia

|

|

Choreoacanthocytosis

|

Autosomal recessive

|

Mainly orofacial, tongue-biting, elevated CK, hyporeflexia,

acanthocytosis

|

|

Postapoplectic chorea

|

Vascular (prior stroke)

|

Sudden hemichorea and hemiparesis, often combined with

hemiballism

|

|

Senile chorea

|

Vascular and degenerative

|

Occasional presenile onset, often more severe on one side,

occasionally with dementia

|

|

Athetosis: slow,

exaggerated movements against resistance of antagonist

muscles, mainly distal; seem uncomfortable and

cramped

|

|

Status marmoratus

|

Perinatal asphyxia

|

Soon after birth, increasingly severe athetotic hyperkinesia,

often cognitive impairment, sometimes also spasticity

|

|

Status dysmyelinisatus

|

Kernicterus of the newborn

|

Onset immediately after birth, often with other signs of

perinatal brain damage; further progression

|

|

Pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration

|

autosomal recessive disorder of pigment metabolism

|

Choreoathetotic movements beginning at age 5 to 15 y,

rigidity, dementia, and retinitis pigmentosa in one-third of

cases; progressive, with characteristic joint

hyperflexion/hyperextension; death by age 30 y

|

|

Hemiathetosis

|

Focal lesion of pallidum and striatum

|

Unilateral, may come about some time after the causative

lesion

|

|

Ballism/hemiballism: unilateral,

lightning-like, high-amplitude flinging movements of multiple

limb segments

|

Ischemic or neoplastic lesion of the subthalamic

nucleus

|

Sudden onset, usually with hemiparesis as well

|

|

Dystonic syndromes

|

|

Torsion dystonia: slow, tonic contractions of muscles or

muscle groups, of shorter or longer duration, usually against

the resistance of antagonist muscles

|

Familial types

|

Often in Ashkenazi Jewish families, onset before age 20 y with

focal dystonia; later, rotatory movements of the head and trunk,

as well as limb movements and athetotic finger movements

|

|

Symptomatic types

|

For example, in Wilson disease, Huntington disease,

pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration

|

|

L-DOPA-sensitive dystonia: usually arises in childhood with

dystonia of variably localization and fluctuation over the

course of the day; progresses over the years

|

Sometimes due to familial tyrosine hydroxylase

deficiency

|

Responds well to L-DOPA; can be difficult to distinguish from

juvenile Parkinson disease with dystonia

|

|

Spasmodic torticollis: slow contraction of cervical and nuchal

musculature against antagonist resistance, with rotatory

movements of the head

|

Idiopathic, occasionally after cervical spine trauma and

various other causes

|

One-third spontaneous recovery, one-third no change, one-third

progression to torsion dystonia

|

|

Localized dystonia (see section

▶ 6.10.5)

|

|

For example, writer's cramp, faciobuccolingual dystonia,

oromandibular dystonia

|

6.10.1 HuntingtonChorea

Etiology Huntington disease (chorea major) is a genetic disorder of autosomal

dominant inheritance caused by an unstable CAG trinucleotide repeat

expansion on the short arm of chromosome 4.

Pathology The neuropathologic correlate of the disease is loss of small ganglion

cells, mainly in the putamen and the caudate nucleus.

Clinical features The disease generally becomes symptomatic between the ages of 30 and 50

years. As a rule, choreiform movements appear

first, followed by progressive dementia. Patients

who inherited the defective gene from their father

tend to develop overt disease at an earlier age, sometimes with rigidity and

pyramidal tract signs as the initial manifestations.

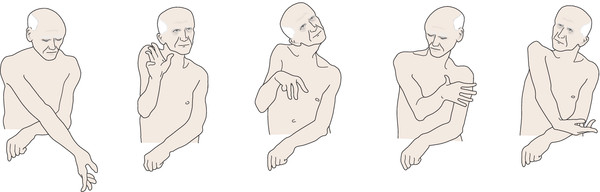

Chorea consists of irregular,

sudden, involuntary movements that are usually more

pronounced at the distal end of the limbs.

-

In some patients, these movements are of low amplitude and

look almost normal, resembling nonpathologic “fidgetiness;” in

others, they are massive and highly disturbing.

-

Chorea can be unilateral (“hemichorea,” ▶ Fig. 6.58) or bilateral.

-

Muscle tone is normal or diminished.

-

There is no weakness or sensory deficit, and pyramidal tract

signs are absent.

-

The intrinsic muscle reflexes are normal, except that they may

have a second extension phase (Gordon

phenomenon) if elicited at the same time as an

incipient choreiform movement.

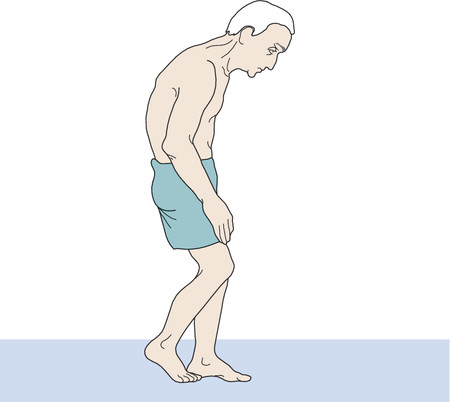

Fig. 6.58 Senile

hemichorea. Drawings from video stills.

Chorea, like other hyperkinesias (see later), is typically enhanced by

goal-directed movement, mental stress, or concentration, and subsides in

sleep and under general anesthesia.

Treatment, course, and prognosis Huntingtonchorea progresses chronically,

generally ending in death 10 to 15 years after the

onset of symptoms. There is no treatment other than palliative, symptomatic

management. The abnormal movements can be alleviated to some extent with

perphenazine,

tetrabenazine, tiapride, and other

neuroleptic drugs. Depression can be treated with an SSRI or sulpiride; anxiety, agitation,

and insomnia with benzodiazepines; and psychosis

with neuroleptic drugs, preferably atypical ones

such as olanzapine.

6.10.2 Chorea Minor (Sydenham Chorea)

Epidemiology Chorea minor is the most common disease

associated with choreiform movements. It mainly strikes school-aged girls.

Etiology and pathogenesis This disease arises after an infection with β-hemolytic

group A streptococci and is caused by an autoimmune reaction in

which antibodies are generated that cross-react with neurons.

Clinical features Within a few days or weeks after an attack of “strep throat,” or within a

few weeks or months of an attack of rheumatic fever, the patient develops

choreiform motor unrest (mainly in the face,

pharynx, and hands), combined with irritability and

other mental abnormalities.

Treatment, course, and prognosis The treatment is with high-dose penicillin for at

least 10 days. The manifestations resolve spontaneously in a few weeks or

months.

6.10.3 Athetosis

Pathology The neuropathologic basis of athetosis is loss of neurons in the striatum,

the globus pallidus, and, less commonly, the thalamus.

Etiology and types of athetosis Congenital and perinatally acquired lesions of the basal

ganglia (status marmoratus, status dysmyelinisatus, severe

neonatal jaundice = kernicterus) cause bilateral athetosis (athétose double), sometimes in conjunction with other

signs of brain damage. Choreoathetosis and dystonia are prominent

manifestations of iron deposition in the basal ganglia in pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration. Focal brain lesions, too, for example, an infarct,

can produce hemiathetosis.

Clinical features Athetosis generally consists of slow, irregular

movements mainly affecting the distal ends of the limbs, causing

extreme flexion and extension at the joints and correspondingly bizarre

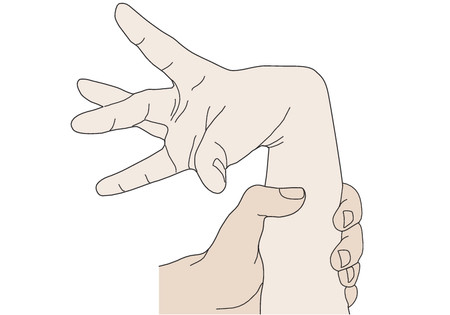

postures, particularly of the hands ( ▶ Fig. 6.59). The interphalangeal joints

may be hyperextended to the point of subluxation (“bayonet

finger”). Athetosis is often found in combination with chorea (“choreoathetosis”).

Fig. 6.59 Hand posture in

athetosis.

Athetosis can be hard to distinguish from dystonia and is often

designated as such. Athetosis can be considered a form of dystonia that

is most prominent at the distal end of the limbs.

6.10.4 Ballism

Pathology The neuropathologic substrate of ballism is a lesion of the contralateral

subthalamic nucleus (corpus Luysii) and/or its fiber connections to the

thalamus.

Etiology Ballism is usually due to focal ischemia, and

less commonly due to a space-occupying lesion. It

may also be the result of severe neonatal jaundice or of a hereditary

degenerative disease; it is typically bilateral in such patients.

Clinical features Rapid, propulsive, large-amplitude, unbraked flinging

movements of the limbs are seen on one side of the body

(hemiballism) or both. Unlike chorea, these movements occur mainly in the

proximal joints. The limbs may be hurled

against walls, etc., causing injury.

Treatment Haloperidol and chlorpromazine can alleviate ballism. Stereotactic neurosurgical

procedures are sometimes necessary.

6.10.5 Dystonic Syndromes

Pathology and etiology There are no characteristic neuropathologic abnormalities in dystonia. To

date, only a few of the disorders that cause dystonia have a known

pathophysiologic basis (e.g., L-DOPA-sensitive dystonia). Precipitating

factors of symptomatic dystonia are likewise only rarely identifiable.

Often, the etiology of dystonia remains unclear.

Clinical features Dystonia consists of slow, long-lasting contractions of

individual muscles or muscle groups. The trunk, head, and limbs

assume uncomfortable or even painful positions and maintain them for long

periods of time. The various clinical types of dystonia are classified as

either focal, that is, affecting isolated,

individual (small) muscle groups, or generalized.

Treatment In the treatment of generalized dystonia, baclofen, carbamazepine, and

trihexyphenidyl are used, either as monotherapy or in combination, often

with only limited success. For some types of dystonia, a trial of L-DOPA

treatment may be worthwhile. Focal dystonias can be successfully treated

with botulinum A toxin injections. In some cases of

dystonia, deep brain stimulation can be highly effective; the preferred

target structure is the globus pallidus internus.

Types of Generalized Dystonia

Torsion dystonia This category of dystonia is characterized by slow, forceful, mainly rotatory movements of the trunk

and head, usually accompanied by athetotic finger movements.

Muscle tone is diminished at the onset of the disease. In some cases,

hyperkinesia gradually ceases and gives way to hypertonia with a rigidly

maintained dystonic posture (myostatic type).

The various types of primary torsion dystonia are mostly of autosomal dominant inheritance, with low

penetrance, and have been localized to genes on various chromosomes. The

early-onset form is particularly common among Jews of Ashkenazi (Eastern

European) ancestry and is due to a genetic defect at the 9p34

locus.

L-DOPA-sensitive dystonia (Segawa disease) This is an autosomal recessive

disorder due to a genetic defect on chromosome 14q. It usually presents

in young girls as a gait

disturbance characterized by dystonic postures or movements

of the legs that fluctuate widely in severity over the course of the

day. It is liable to misdiagnosis as a psychogenic disorder. It

typically responds to low doses of L-DOPA (250 mg, or a little more, per

day). A therapeutic test of L-DOPA is worthwhile in any young patient

with dystonia, even if no other family members are affected.

Focal Dystonia

Focal dystonia is much more common than generalized dystonia. The

abnormal movements are restricted to individual parts of the body or

muscle groups. The main types of focal dystonia are the

following:

Spasmodic torticollis In this disorder, slow contraction of individual muscles of

the neck and shoulder girdle produce tonic rotation of

the head to one side or the other ( ▶ Fig. 6.60). It

is usually the contralateral sternocleidomastoid muscle that is most

strongly contracted. Only one-third of all patients with “wry neck” due

to spasmodic torticollis undergo spontaneous remission; a further third

go on to develop other dystonic manifestations. The etiology usually

remains unclear; there are probably multiple causes.

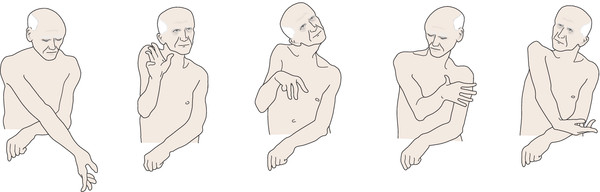

Fig. 6.60 Spasmodic

torticollis. (a) A

32-year-old man whose head is spontaneously lightly turned to

the right. (b) Torticollis with tonic,

involuntary head rotation to the right. Note the hypertrophic

left sternocleidomastoid muscle. (c)

The patient can bring his head back to the neutral position by

pressing gently on the lower jaw with a fingertip.

Blepharospasm This consists of bilateral tonic contraction of the

orbicularis oculi muscles, often with very

long-lasting involuntary eye closure, during which the

patient cannot voluntarily open his or her eyes. Blepharospasm tends to

affect older patients, mainly women. Eye closure may be forceful, with

visible contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle, or weak, with a

relatively normal external appearance. Cases of the latter type are

alternatively designated lid-opening apraxia.

Misdiagnosis as a psychogenic disturbance is, unfortunately,

common.

Dystonia affecting multiple muscles of the head The various types of focal dystonia that come under this

heading are not rare when taken together; they include facio-bucco-lingual dystonia,

oromandibular dystonia, and Brueghel

or Meige syndrome. There may also be a

relatively isolated dystonia of the mouth, pharynx,

and tongue, particularly in patients who have been treated

with neuroleptics. An acute form can appear as a complication of

antiemetic drugs such as metoclopramide.

Isolated dystonia Isolated dystonias have been described for practically

every muscle group in the body. Dystonia of this type may be idiopathic

or may arise in connection with occupational

overuse of the muscle group in question. Well-known examples

include writer’s cramp, hand

dystonia in musicians, and foot

dystonia in certain other occupations. Spastic dysphonia is a focal dystonia of the laryngeal

musculature.

6.10.6 Essential Tremor and Other Types of Tremor

Types of tremor The main phenomenological distinction is between

the following:

-

Rest tremor.

-

Action tremor.

Action tremor, in turn, is subdivided into the following:

-

Postural tremor.

-

Isometric tremor (appearing when a muscle is contracted against

constant resistance).

-

Kinetic tremor (appearing only during movement). Intention tremor

is a kinetic tremor that worsens as the limb nears its

target.

Tremor can also be classified etiologically as

shown in ▶ Table 6.35.

Table 6.35 Types of tremor

|

Designation

|

Characteristics

|

|

Physiologic tremor

|

Seen in normal individuals; intensified by pain, anxiety,

cold, caffeine ingestion, etc.

|

|

Thyrogenic tremor

|

Hyperthyroidism also intensifies physiologic tremor

through the mediation of catecholamines. The tremor appears

as a fine trembling of the hands

|

|

Essential tremor

|

See text. This hereditary condition is sometimes

misdiagnosed as Parkinson disease

|

|

Orthostatic tremor

|

Similar to essential tremor bur arises only when the

patient is standing, manifesting itself as shaking of the

legs; mainly seen in the elderly. Other muscle groups can be

similarly affected when under tonic stress

|

|

Parkinsonian tremor

|

See the discussion of Parkinson disease (see

section ▶ 6.9.2).

Usually consists of rest tremor, e.g., of the hand or

fingers when resting on a solid surface, or of the hand when

the arm is dependent

|

|

Psychogenic tremor

|

Sudden attacks of tremor, e.g., in acute stress disorder;

often highly variable in intensity; coarse; of demonstrative

quality

|

|

Holmes tremor

|

Unilateral, low-frequency rest, postural, and intention

tremor (becomes stronger as the movement nears its

target)

|

|

Cerebellar tremor

|

Intention tremor arising after cerebellar injury (becomes

stronger as the movement nears its target)

|

|

Dystonic tremor

|

Tremor and movement disturbance due to dystonia

(section ▶ 6.5.10)

|

|

Asterixis (“flapping tremor”)

|

Sudden loss of postural tone, mainly seen in hepatic

encephalopathy but also in other liver diseases, e.g.,

Wilson disease

|

|

Alcohol-related tremor

|

Fine rest and intention tremor, worse during alcohol

withdrawal, improves after consumption of alcohol (but note:

essential tremor often improves with alcohol as well)

|

|

Tremor induced by drugs, hormones, or toxic

substances

|

Resembling physiologic tremor, but more intense

|

Essential tremor This is the most common type of tremor

and often runs in families. Genetic defects causing

familial essential tremor have been found on chromosomes 2p22– p25 and 3q.

It usually arises between the ages of 35 and 45 years. It is a predominantly

postural and sometimes also kinetic tremor of the hands; a pure intention

tremor is seen in 15% of patients (see

▶ Fig. 3.22). It may also affect the head in isolation (nodding or shaking tremor of the

“yes” or “no” type), sometimes including the chin and/or vocal cords.

Essential tremor typically improves after the consumption of a small

amount of alcohol and worsens with nervousness or stress.

“Essential tremor plus” is a

combination of this entity with another neurologic disorder (e.g., Parkinson

disease, dystonia, myoclonus, polyneuropathy, restless legs

syndrome).

Diagnostic evaluation Thorough history-taking and a precise neurologic examination often yield

important clues to the etiology of tremor; further studies (e.g., imaging

studies) are only rarely necessary. In some cases, electrophysiologic testing is needed to pinpoint the correct

diagnosis (e.g., in suspected orthostatic tremor). Laboratory testing may

also be needed to exclude underlying disease.

Treatment If the tremor is severe enough to interfere with the patient’s

everyday activities, a β-blocker such as

propranolol can be tried; this drug is particularly effective against

essential tremor. Primidone,

benzodiazepines, and clozapine are

further alternatives. A tremor accompanied by dystonia may respond well to

botulinum toxin injections. Deep brain stimulation

through an electrode that has been stereotactically implanted in the nucleus

ventrointermedius of the thalamus is highly effective but is reserved for

severe, medically intractable cases.

Differential diagnosis Involuntary movements arising from diseases of the basal ganglia must be

differentiated from a variety of other movement disorders, which are listed

in ▶ Table 5.3.