3.1 Basic Principles of the Neurologic Examination

3.8 Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

3.1 Basic Principles of the Neurologic Examination

3.8 Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

A Fateful Diagnosis

A 62-year-old woman is referred by her family physician to a neurologist. She has been feeling exhausted for several months. Recently, she has also been suffering from muscle cramps, and she has noticed that food occasionally “goes down the wrong pipe.” The neurologist’s examination reveals the following:

Head and cranial nerves: Gag reflex not clearly elicitable, all findings otherwise normal.

Speech: Mildly slurred.

Upper and lower limbs: Asymmetric, marked atrophy of various muscles, no clear abnormality of muscle tone, surprisingly brisk reflexes even in the muscles that are markedly weak and atrophic, visible fasciculations.

Babinski reflex weakly elicitable bilaterally. Coordination normal. Sensation intact in all modalities.

Stance and gait: Marked difficulty standing on the toes and heels due to weakness.

Psychopathologic state: Patient worried and anxious, otherwise normal.

Neuropsychological state: No evident deficits.

General physical examination: Impaired nutritional state and mildly impaired general state of health, blood pressure mildly elevated, cardiovascular examination otherwise normal. Chest clear, abdomen soft, all peripheral pulses palpable.

Assessment: The patient is a 62-year-old woman with muscle atrophy and weakness but no accompanying sensory disturbance. This constellation of findings is present only in myopathy or a disease of the ventral horns of the spinal cord. The fasciculations point toward ventral horn dysfunction rather than myopathy. A disease affecting the nerve roots or peripheral nerves might cause muscle atrophy and weakness, but would also be expected to cause sensory deficits and hypo- or areflexia. This patient’s reflexes are brisker than normal, indicating that her condition affects the pyramidal tracts as well—an inference solidly confirmed by the Babinski sign. Combined dysfunction of the ventral horns and pyramidal tracts is the clinical hallmark of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and this diagnosis appears highly likely from the physical findings. The patient’s mildly slurred speech indicates bulbar involvement.

Although many highly informative ancillary tests are available, it would be an error to work up neurologically abnormal patients with only neuroimaging and other high-technology diagnostic procedures. Rather, the neurologist must take a thorough history, perform a full, meticulous clinical neurologic examination, and then document all findings in full. On the basis of these findings, the neurologist can decide what additional tests to order next, in case any are needed.

In this chapter, the components of a systematic neurologic examination (including a neuropsychological examination, if indicated) are described in detail, along with the main abnormal findings. The information provided here should enable the examining physician to localize the underlying lesion in the nervous system anatomically on the basis of the findings. Anatomic localization does not, in itself, reveal the etiology of the problem; further information from the history and additional tests will be needed for this.

Key Point

Neurologic diseases can often be diagnosed on the basis of a carefully elicited history in combination with the physical examination. To ensure completeness, the examining physician should examine all patients according to the same general scheme.

One may either examine the individual components of the nervous system in a particular sequence (cranial nerves, reflexes, and motor, sensory, and autonomic function) or conduct the examination along topographic lines (head, upper limbs, trunk, lower limbs). The presentation in this chapter is topographically organized.

Neurology stands by itself as an independent medical specialty and field of research. Most neurologic illnesses affect only the nervous system. Nonetheless, general medical illnesses often manifest themselves with neurologic symptoms and signs (cf. section ▶ 6.8). The clinical neurologic examination must therefore always include a general physical examination.

The practicing neurologist should emphasize the neurologic aspects of the physical examination without neglecting its general aspects.

Here are some basic principles of physical examination:

The examiner must talk to the patient, briefly explaining the purpose of individual steps in the examination where appropriate. This affords the examiner the opportunity to obtain more information on certain aspects of the clinical history, if necessary.

In principle, the neurologic examination should always be complete and should always be performed in the same sequence, though the examiner is free to use whatever sequence he or she prefers. The individual components of the examination are listed in ▶ Table 3.1. In certain exceptional situations, or on repeated follow-up, a highly experienced clinician may choose to perform only a partial examination. This is generally to be avoided, however, as even the best neurologist can miss something important in this way. A thorough, methodical examination also helps reassure the patient that the physician is competent and attentive.

|

Region |

Findings |

|

General |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cognition and behavior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Head and cranial nerves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Olfactory nerve (CN I) |

|

|

|

|

Optic nerve (CN II) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves (CN III, IV, and VI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trigeminal nerve (CN V) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Facial nerve (CN VII) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves (CN IX and X) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accessory nerve (CN XI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) |

|

|

|

|

Upper limbs |

|

|

Trunk |

|

|

Lower limbs |

|

|

Stance and gait |

|

|

Abbreviations: CN, cranial nerve; VOR, vestibulo-ocular reflex. Note: If this table, or one like it, is used in practice to document the findings of the clinical neurological examination, the examiner should note all abnormal findings in the appropriate place and place a check (✓) or plus sign (+) next to all examined items that are normal. The record will then show which (if any) elements of the examination have been omitted. Items in italics should, in principle, be examined in every patient. Only experienced examiners should perform a restricted neurologic examination. |

|

Patients should be examined unclothed, after being given clear instructions about which clothes to remove, usually everything but their underwear. The spine cannot be examined if the upper body is covered; if the patient is wearing socks, sensation cannot be tested in the feet, and the Babinski reflex cannot be elicited.

Although the examination should always be systematic and complete, the tentative diagnosis (or diagnoses) suggested by the history will direct the clinician to pay particular attention to certain aspects of the examination. There is no sense in the mechanical, unthinking performance of a rigidly identical examination on every patient.

Deviating from the usual order of examination may be advisable for psychological reasons. For example, if the patient mainly has symptoms in the lower limbs or the back, one can begin the examination with the spine.

As soon as possible after the examination is completed, the examiner should document the findings in writing. Global statements such as “Neuro OK” are worthless. The findings can be summarized in an outline such as the one provided in ▶ Table 3.1. The main purpose of precise documentation is to let the clinician follow the development of a disease process from one examination to the next. It is also obviously indispensable for medicolegal reasons.

Moreover, certain findings should be quantified or numerically graded, particularly muscle strength (see ▶ Table 3.5). Sensory disturbances should be documented precisely in terms of their topography and extent.

Key Point

Stance and gait should be tested systematically with the patient unclothed and barefoot. Inspection of the standing patient at rest may already reveal signs of disease. Next, the patient’s gait is examined, usually with special tests of walking and balance.

Though stance and gait are listed at the bottom of ▶ Table 3.1, we in fact recommend testing these functions as the first step in the examination of the unclothed patient.

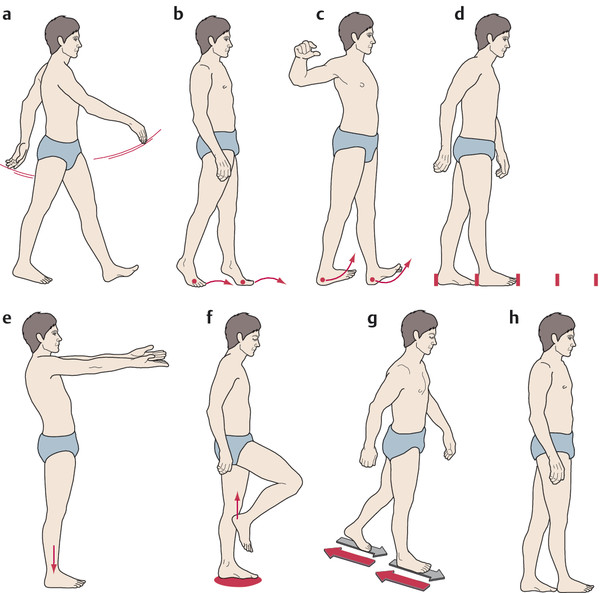

Inspection of the standing patient can already reveal evidence of a disease process, for example, muscle atrophy, spinal deformities, and winging of the scapula. The patient’s posture at rest may be abnormal, for example, the exaggerated lumbar lordosis of muscular dystrophy (cf. ▶ Fig. 15.3) or the stooped, rigid posture of the patient with Parkinson disease (cf. ▶ Fig. 6.55, ▶ Fig. 6.56). The testing of stance and gait often yields important clues to the disease process. The sequence of tests is shown in ▶ Fig. 3.1a–h.

Fig. 3.1 Tests of stance and gait. a Normal gait. Note normal step length and arm swing. b Walking on tiptoes. c Walking on heels. d Heel-to-toe (tandem) walking. One foot is placed precisely in front of the other. e Romberg test with eyes closed, combined with postural test of the upper limbs. f Unterberger step test: walking in place with eyes closed. g Babinski–Weil test with “star gait” (marche en étoile): the patient is asked to take two steps forward and two steps back, repeatedly, with eyes closed. h Tandem stance: standing with one foot precisely in front of the other. For interpretation, see text.

Note

In the assessment of stance and gait, attention should be paid to the following:

Does the patient walk fluidly, symmetrically, and without a limp? If the patient has a limp, then the side that bears weight for the shorter time is the abnormal side.

How long are the patient’s steps, and how are the feet placed on the ground and rolled off it?

How do the arms move while the patient walks?

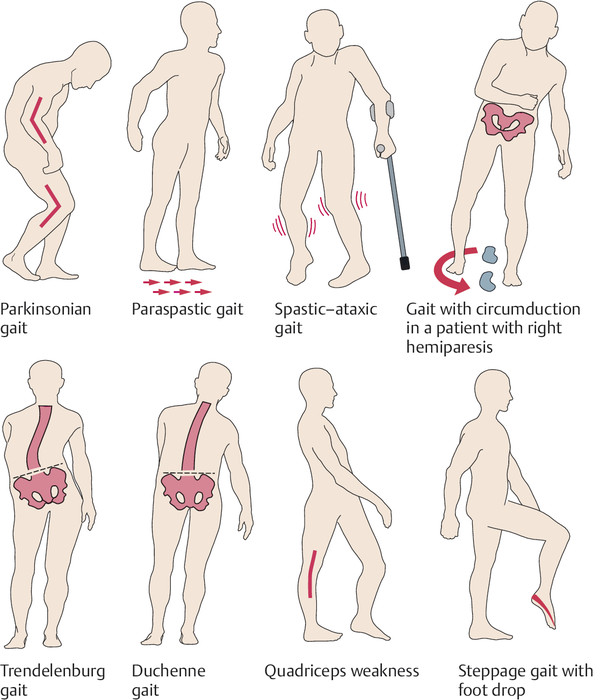

Some characteristic disturbances of gait are described in ▶ Table 3.2.

|

Designation |

Abnormalities of gait |

Causes/remarks |

|

Spastic gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

Slow, stiff, with audible dragging of the soles of the feet across the ground |

Bilateral pyramidal tract lesion |

|

Ataxic gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

Uncoordinated, stamping, unsteady, deviating irregularly from a straight line; heel-to-toe walking impossible |

Cerebellar dysfunction, posterior column dysfunction, polyneuropathy |

|

Spastic–ataxic gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

Combination of the two disturbances described above; jerky, stiff, inharmonious gait |

Most commonly seen in multiple sclerosis |

|

Dystonic gait |

Irregular additional movements interfering with the normal course of gait |

Basal ganglionic disease causing choreoathetosis or dystonia |

|

Hypokinetic gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2 and ▶ Fig. 6.56) |

Slow gait, stiff, bent posture, small steps, lack of accessory arm movements; turning requires multiple small steps |

Most commonly seen in Parkinson disease; similar picture in the lacunar state (cerebral microangiopathy, cf. section ▶ 6.5.6) |

|

Small-stepped gait (“marche à petits pas”) |

Small steps, unsteady, resembles hypokinetic gait but with more normal accessory arm movements |

“Old person’s gait” most commonly seen in the lacunar state, i.e., multiple small infarcts in the basal ganglia and along the corticospinal tracts; distinguishable from parkinsonian gait mainly by the different accompanying signs |

|

Circumduction ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

Increased tone in the extensors of the paretic leg, which comes forward in a gentle outward arc, with a strongly plantar-flexed foot; hardly any accompanying movement of the flexed and adducted ipsilateral arm |

Central (spastic) hemiparesis |

|

Steppage gait |

The advancing leg is raised high and then placed on the ground toe first, often with an audible slap |

Unilateral: foot drop, e.g., in peroneal nerve palsy; bilateral: e.g., polyneuropathy or Steinert myotonic dystrophy |

|

Hyperextended knee ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

With each step, the knee of the stationary leg is hyperextended |

Prevents buckling of the knee when the knee extensors are weak—unilaterally, e.g., in quadriceps weakness due to a lesion of the femoral nerve; bilaterally, e.g., in muscular dystrophy |

|

Hyperlordotic gait ( ▶ Fig. 15.3a) |

Exaggerated lumbar lordosis |

For example, in muscular dystrophy affecting the pelvic girdle, in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

|

Trendelenburg gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

With each step, the pelvis tilts downward on the side of the swinging leg |

Severe hip abductor weakness—unilaterally, e.g., in lesions of the superior gluteal nerve; bilaterally, e.g., in muscular dystrophy affecting the pelvic girdle and in bilateral hip dislocation |

|

Duchenne gait ( ▶ Fig. 3.2) |

With each step, the upper body tilts to the side of the stationary leg |

Mild or moderate weakness of the hip abductors (as in Trendelenburg gait, but less severe), or as an antalgic maneuver in disorders of the hip joint |

The clinician can judge the strength of the calf muscles and the foot and toe extensors by making the patient walk on tiptoe and on the heels ( ▶ Fig. 3.1b,c). If the plantar flexors are only mildly weak, the patient will still be able to walk on tiptoe, but will not be able to raise himself or herself on tiptoe while standing on one leg, or hop repeatedly on one foot (10 times in succession) (see ▶ Fig. 13.66).

The “tightrope walk” (heel-to-toe walk, tandem walk) ( ▶ Fig. 3.1d) is a very sensitive test of equilibrium and gait stability. The patient is instructed to place one foot firmly and directly in front of the other, at first while looking at the floor, then while looking straight ahead, and finally while looking at the ceiling. Heel-to-toe walking should be possible under all of these conditions. Heel-to-toe walking with the eyes closed is a more difficult task that many normal persons cannot perform.

The Romberg test ( ▶ Fig. 3.1e) is a further test of equilibrium. The patient is asked to stand with the feet together and parallel and with eyes closed, for at least 20 seconds. This should be accomplished calmly and easily, without any appreciable swaying. The test can be made more difficult by having the patient turn or incline the head to one side. It can also be performed in combination with postural testing of the arms (see later). Other demanding tests of equilibrium include standing with one foot precisely in front of the other (tandem stance, ▶ Fig. 3.1h) and standing on one foot. Normal persons can stand on one foot for at least 5 seconds and, for example, put their trousers on or take them off while standing freely; persons older than 70 years cannot always do this.

The functions of the vestibular system (section ▶ 12.6.2) and cerebellum (section ▶ 5.5.6) can be tested in several ways:

In the Unterberger step test ( ▶ Fig. 3.1f), the patient is made to walk with the eyes closed, raising the knee to (or above) the horizontal with each step. After 50 steps, the patient should have rotated no more than 45 degrees from his or her original position. Larger rotations suggest dysfunction of the vestibular apparatus on the side to which the patient has turned or of the cerebellar hemisphere on that side.

In the “star gait” test of Babinski and Weil ( ▶ Fig. 3.1g), the patient keeps the eyes closed and walks two steps forward and two steps back, repeatedly. Dysfunction of the vestibular system manifests itself as involuntary turning to the side of the lesion.

In blind walking, the patient first looks at the examiner, who is standing some distance away, then closes the eyes, and walks toward him or her. Vestibular lesions usually cause a deviation to the side of the lesion.

Several common gait abnormalities are illustrated in ▶ Fig. 3.2.

Fig. 3.2 Common gait disturbances.