CHAPTER 1

Northwest Yellowstone: Mammoth/Gallatin Country

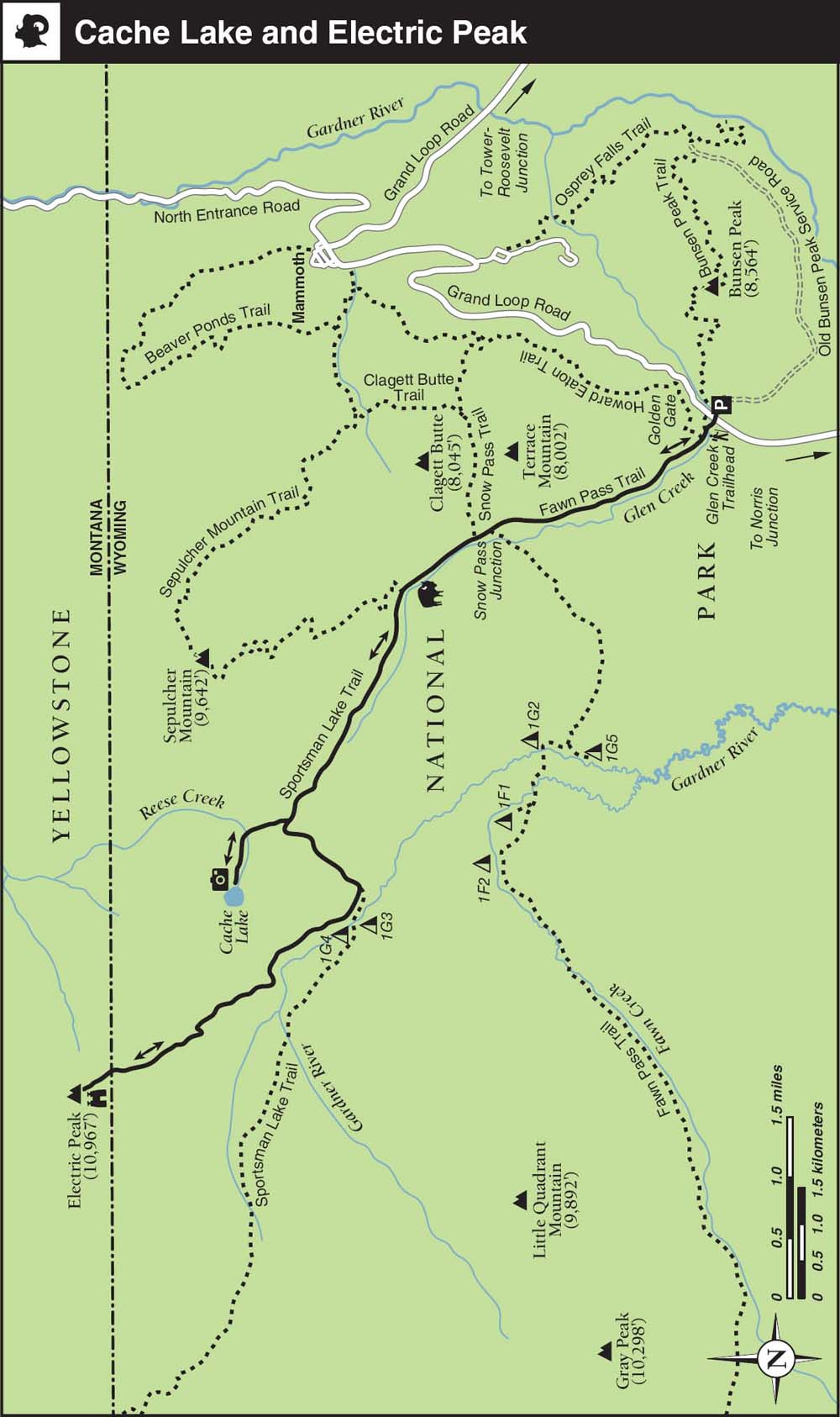

4. Cache Lake and Electric Peak

Overleaf and opposite:Andrew Dean Nystrom on Bunsen Peak (Trail 3)

Northwest Yellowstone: Mammoth/Gallatin Country

The northwestern quadrant of Yellowstone National Park includes the developed area around the park’s headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs and, to the west, the soaring peaks of the Gallatin Range. It is also the park’s lowest and driest region, which makes it a great place to visit in spring, fall, and winter.

The North Entrance, near the sociable gateway town of Gardiner, Montana, is the only park entrance that remains open year-round; the Grand Loop Road remains open year-round between Gardiner and Cooke City. Just before Mammoth Hot Springs, the first-come, first-served Mammoth Campground ($20) is the park’s only year-round campground. Eight miles south of Mammoth, the smaller, National Park Service–run Indian Creek Campground ($15) is in the thick of moose country and is often closed in the spring season because of bear activity.

The region’s diverse terrain includes some of the park’s topographic extremes, ranging from desertlike corridors between 5,300 and 6,000 feet near the park’s northern boundary to several peaks that top out at more than 10,000 feet. Yellowstone’s low-lying Northern Range, which straddles the Montana–Wyoming state line, is a vital overwintering area for migrating wildlife such as pronghorn, elk, bighorn sheep, mule deer, bison, and coyotes between November and May. Like the animals, early- and late-season hikers migrate here to seek refuge from the rest of the park’s extreme weather. These relatively mild conditions also make Mammoth a popular base camp for winter sports such as snowshoeing and cross-country skiing.

In Mammoth, the main visitor center and backcountry office (where permits are issued) are housed adjacent to the park headquarters in the Fort Yellowstone–Mammoth Hot Springs Historic District, in buildings constructed by the US Army during its tenure as park custodian (1886– 1918). Nearby, portions of the updated Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel date back to 1911. Nightly room rates run $150–$262, with cabins available from $98; call 307-344-7311 for information and reservations. The hotel will be closed for renovations during winter 2017.

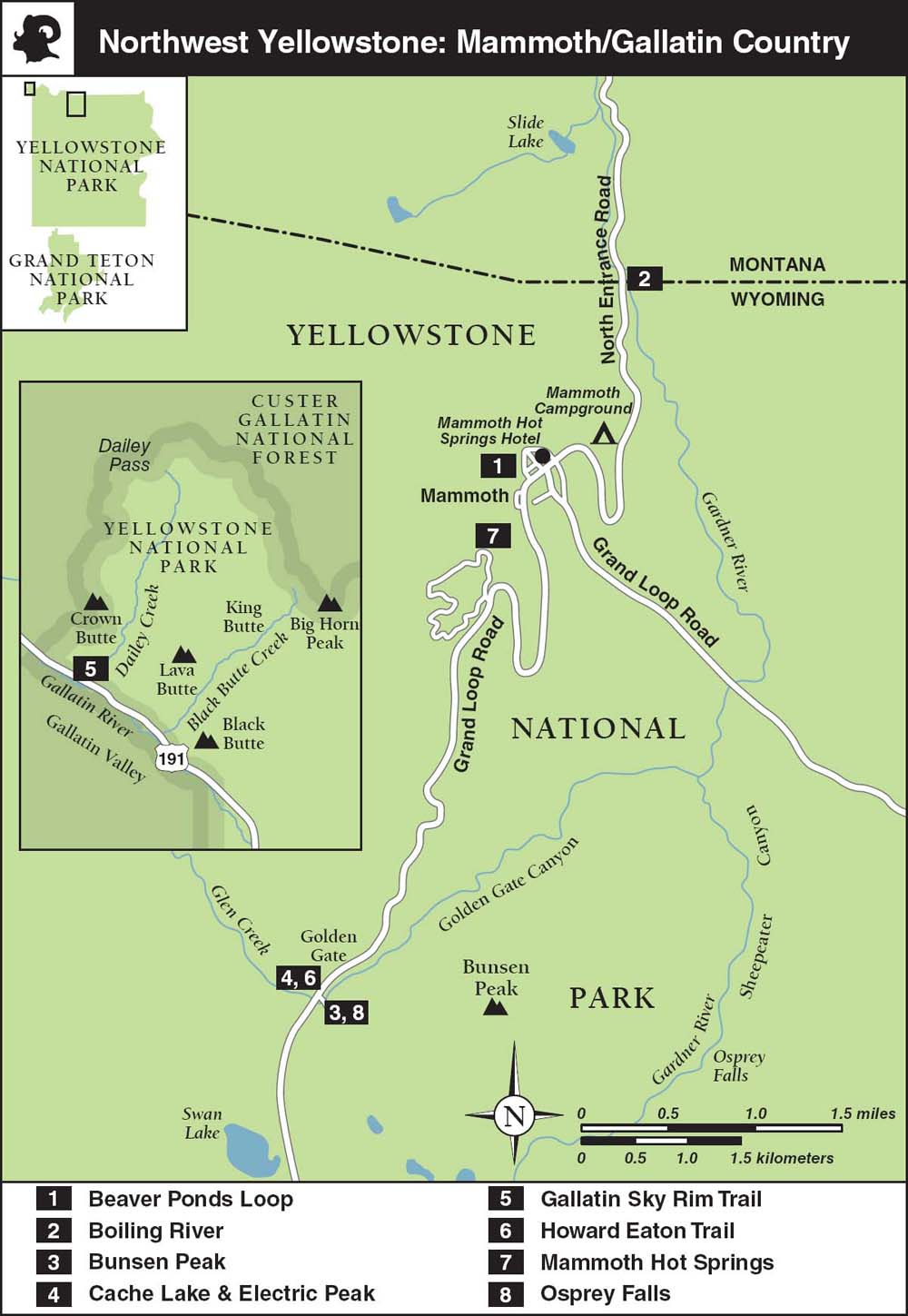

AREA MAP

TRAIL FEATURES TABLE

Just outside the North Entrance, which was the park’s first major gateway, the large stone Roosevelt Arch was designed by Old Faithful architect Robert Reamer in 1903 to commemorate the completion of the Northern Pacific railway spur line from Livingston to Gardiner, Montana, and the subsequent visit of President Theodore Roosevelt. The top of the arch is inscribed FOR THE BENEFIT AND ENJOYMENT OF THE PEOPLE, a quote from the Organic Act of 1872, the enabling legislation for what was then the world’s first national park. Inside the arch is a sealed time capsule that includes period postcards and a photo of Roosevelt. It was here that the park celebrated the centenary of the National Park Service in 2016.

The railroad’s plans to lay spur lines through the fragile geyser basins and monopolize public access to the park were countered by the lobbying efforts of President Roosevelt’s Boone & Crockett Club, a politically influential pro-hunting group. By 1905 the US Army Corps of Engineers had established the beginnings of today’s Grand Loop Road, and in 1915 the first private automobiles were admitted to the park. In 1916 the newly constituted National Park Service banned horse-drawn wagons from all park roads.

Today, you can still drive or cycle the original gravel stagecoach road (one-way only, except for bicycles and hikers) from Mammoth to Gardiner. It starts behind the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel and winds down 5 miles to the North Entrance gate.

Permits and Maps

The year-round Albright Visitor Center and Museum sells a good selection of maps and field guides and is the only place in Yellowstone Park to offer free Wi-Fi. A small museum focuses on history and has a good exhibit on predators and prey upstairs. Rangers also hand out free day-hiking brochures and are a good source of trail updates and general advice. Call 307-344-2263; open daily, 8 a.m.–7 p.m. in summer, 9 a.m.–5 p.m. in winter. For more detailed trail information, head downstairs to the summer-only backcountry office, which issues boating, fishing, and backcountry camping permits and is a wealth of hiking and backpacking information. Call 307-344-2160; the office is open 8 a.m.–noon and 1–4:30 p.m. In spring, fall, and winter, call the park’s operator at 307-344-7381 for advice about where to obtain permits.

National Geographic’s Trails Illustrated Mammoth Hot Springs (no. 303, scale 1:63,360) map depicts all of the trails, trailheads, and campsites mentioned in this chapter. The similar Trails Illustrated Yellowstone National Park (no. 201, scale 1:126,720) map, with trails and mileage way points, has sufficient detail for trip planning and frontcountry hiking but does not depict trailheads or backcountry campsites. A good compromise is Beartooth Publishing’s Yellowstone North (1:80,000).

Northwest Yellowstone: Mammoth/Gallatin Country

Beaver Ponds Loop

The most popular moderately strenuous day hike in the Mammoth area traverses forested gulches, aspen-dotted meadows, and open sagelands, providing the opportunity to see a wide variety of wildlife, including the occasional moose and black bear. Wildlife is at its most active in the late afternoon.

TRAIL 1

Hike

5.5 miles, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Boiling River

Yellowstone’s premier legal frontcountry soak is a dynamic series of five-star hot pots formed by the confluence of an impressive thermal stream and an icy river. It’s an easily accessible stroll through an attractive river canyon, popular with families, and—for hot-springs aficionados—definitely not to be missed.

TRAIL 2

Hike, Swim

1.0 mile, Out-and-back

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Bunsen Peak

This quick, scenic ascent above timberline is a popular early-season altitude acclimatization route and will give you a real cardio workout. On a clear day, it’s a relatively easy way to gain a panoramic overview of the Northern Range. Waterfall lovers will not want to miss the steep but rewarding side trip to Osprey Falls.

TRAIL 3

Hike

4.2 miles, Out-and-back, or 7 miles, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Cache Lake and Electric Peak

An ambitious and challenging summit hike that offers some of the park’s best views, along with a big sense of achievement and a side trip to a charming lake. It’s best done as an overnighter.

TRAIL 4

Hike, Backpack

21.5 miles, Out-and-back

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

A demanding but scenic ridgeline hike in the northwest corner of the park that promises rugged peaks, volcanic cliffs, and huge views.

TRAIL 5

Hike

16.3 or 18.4 miles, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Howard Eaton Trail

This short downhill section of Yellowstone’s longest trail traverses good wildlife habitat and a wide variety of picturesque terrain, including geothermal areas, boulder fields, and the scenic shoulder of Terrace Mountain. It’s most enjoyable if you can arrange a shuttle.

TRAIL 6

Hike

4 miles, Point-to-point, or 6.6 miles, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

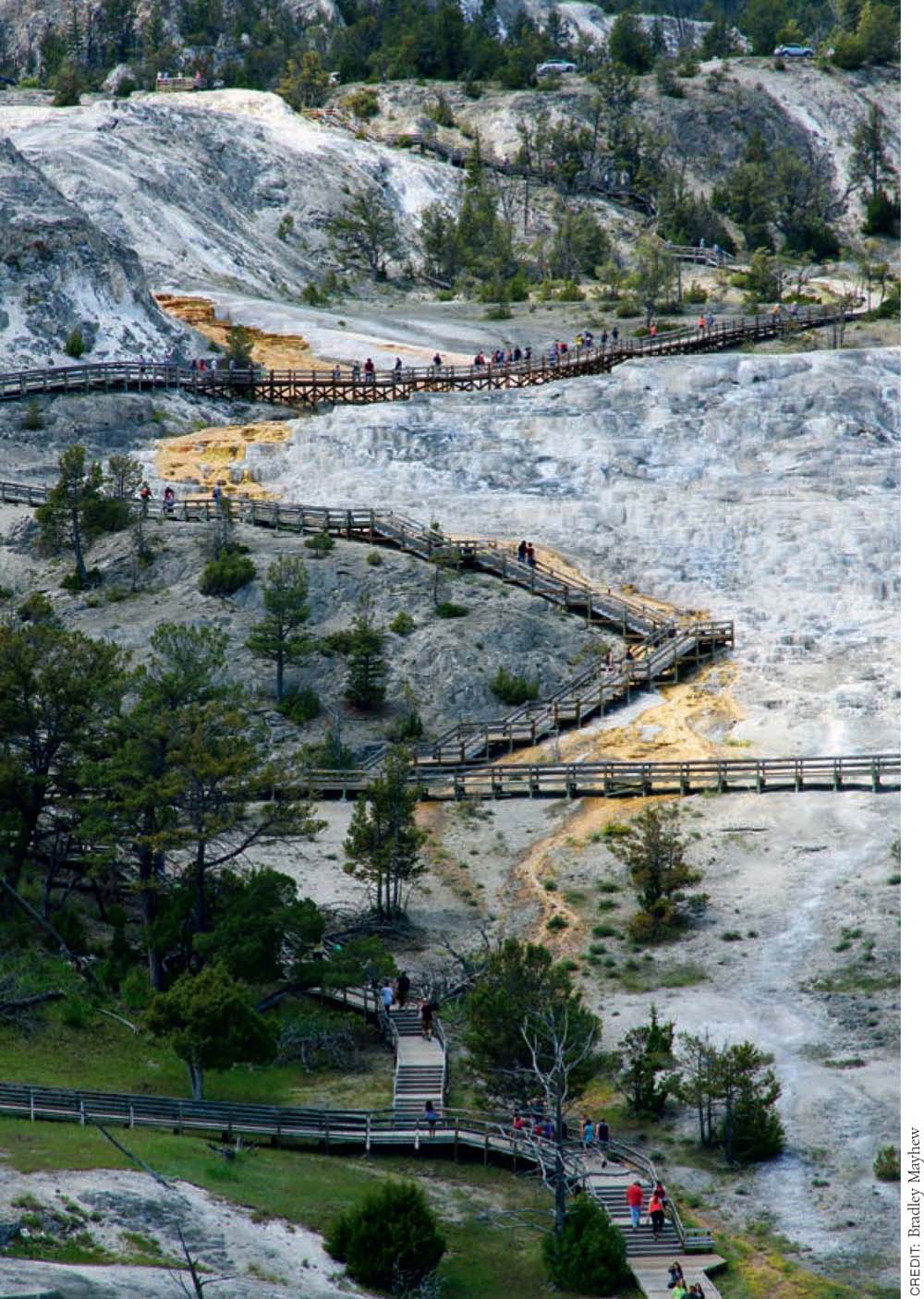

Mammoth Hot Springs

A network of wooden boardwalks offers a closeup look at the most accessible thermal area in the northern half of the park. While Yellowstone’s most famous geysers wow audiences with their predictable, instantly gratifying performances, Mammoth’s mercurial hot-spring terraces are impressive for both their human history and their drawn-out natural development.

TRAIL 7

Hike

1 mile, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Osprey Falls

A strenuous add-on to the Bunsen Peak Loop, this infrequently visited waterfall awaits at the head of the impressive Sheepeater Canyon. After a long, flat stretch along an abandoned service road through a regenerating burn area, you plunge 800 feet into the deep, narrow canyon.

TRAIL 8

Hike, Bike

10.0 miles, Out-and-back, or 10.2 miles, Loop

Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5

Beaver Ponds Loop

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

5.5 miles, 2.5–3 hours

VERTICAL FEET

±400

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt

FEATURES

Child Friendly

Stream

Autumn Colors

Wildflowers

Birds

Wildlife

Great Views

Historic Interest

Geologic Interest

Steep

FACILITIES

Visitor Center

Restrooms

Picnic Tables

Phone

Water

The most popular moderately difficult loop near Mammoth traverses a range of habitats and provides the opportunity to see a wide variety of wildlife, including the occasional black bear.

Best Time

The trail is hikable May–October. During summer, the exposed portions of the route are hot and dry. Wildflowers bloom early here, and aspen groves color the hillside starting in September. Wildlife is most abundant in spring, fall, and winter. The beavers are at their busiest in the late afternoon.

Finding the Trail

From the Grand Loop Road junction in front of the Albright Visitor Center, the Sepulcher Mountain/Beaver Ponds trailhead (1K1) parking area is 0.25 mile south toward Norris Junction. The signed trail-head is at the foot of Clematis Gulch, between an old stone park-employee residence and the dormant hot-spring cone known as Liberty Cap. There are parking lots on both sides of the road, but private vehicles are not allowed to park in the tour bus parking area next to the new restroom facilities.

Logistics

This day hike is one of the only short loop hikes in the northern half of the park and is frequently recommended by rangers at the Albright Visitor Center. It’s also a favorite with park employees early and late in the season. Given all this, it can get busy at times.

From the trailhead parking areas ▸1 near the northern base of the Mammoth Hot Springs terraces, look for a trailhead sign on the main road pointing the way up Clematis Gulch, between the dormant Liberty Cap hot-spring cone (to your left) and the old stone house next to the restroom facility and tour bus parking area (to your right).

Beyond the Sepulcher Mountain trailhead, ▸2 the path crosses Clematis Creek a couple of times on wooden footbridges as it climbs into shady mixed spruce–fir forest. Ignore the Howard Eaton Trail, which cuts uphill just before the second bridge, and continue to your right across the creek.

Steep

Beyond this bridge, the trail swings away from the north bank of the creek and switchbacks sharply around a juniper- and sagebrush-studded ridge to the Howard Eaton–Golden Gate Trail junction ▸3 after 0.3 mile. Keep right to finish the calf-stretching 350-foot climb up to the Beaver Ponds Loop Trail junction, ▸4 0.7 mile from the parking areas.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Starting from Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel

If you’d rather not start out with the steepest part of the hike, you can do the loop in reverse with no difference in elevation gain.

Map Room, Music, and Espresso at Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel

If you have a few minutes to spare, check out the Map Room off the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel lobby. Constructed in 1937, it features a unique map of the United States fashioned from 16 types of wood from nine countries. The map was designed by architect Robert Reamer, who also envisioned the Old Faithful Inn. If you’re staying in the area, check out the schedule of evening talks, slide shows, and live piano music. In the morning (6:30–10 a.m.), there’s an espresso cart in the lobby to get you going.

Old Gardiner Road

If you’re headed north out of the park after the hike, consider taking the scenic, 5-mile gravel stagecoach route down to the North Entrance station in Gardiner.

Male grouse court mates in spring with low-frequency drumming noises they create by rapidly vibrating their wings.

Viewpoint

Beyond this junction, views of Mammoth Hot Springs, Bunsen Peak, and the Lava Creek Bridge on the Mammoth–Tower road open up to the east, with Mount Everts (7,842 feet) tilting to your left in the north. Watch and listen here for strutting sage grouse alongside the trail, especially in early spring.

Birds

Wildlife

The slope eases up as it rolls through sagelands and bird-rich meadows accented by stands of aspen that exhibit the telltale blackened, head-high browsing marks on their trunks, left by sustenance-starved ungulates each winter. As the trail flattens out, it parallels, then passes under, some power lines. Ignore the numerous game trails that branch off the main route here. Where the trail swings east and the views really open up, watch for elk, mule deer, and prong-horn grazing in the sagelands below to your right.

Stream

After passing several mature stands of heavily browsed aspen and crossing a National Park Service service road (which leads up the hill to a radio tower), the trail descends gently through meadows and spruce–fir forest. You cross a seasonal stream via a bridge before reaching the first of several shallow, cattail-fringed beaver ponds ▸5 after 2.5 miles. Look for evidence of the amphibious, hydrological engineers in the form of gnawed-down logs around the shore. The paddle-tailed rodents lie low during the day and are busiest in the late afternoon. Moose are also occasionally spotted browsing nearby in the willow thickets.

Wildlife

The trail undulates and meanders past a couple of small, marshy ponds and crosses four seasonal streams on footbridges over 0.5 mile before arriving at the last and largest of the unnamed ponds. ▸6 Listen for birds as you approach through the trees. The edges of the mixed forest are also a favored haunt of black bears, so make plenty of noise to avoid unpleasant surprises. The trail loops around along the shore, passing a variety of idyllic spots to stop for a picnic lunch. At the outlet, you can admire some of the beavers’ handiwork before carefully crossing over the stream on a simple bridge.

Historic Interest

The trail climbs away from the ponds through open grassland and shady forest, back under more power lines, and past the ruins of an old log cabin before entering a wide-open plateau known as Elk Plaza and more rolling sagelands. Here you get an eye-level view of the geologic layers of the ridgelike Mount Everts across the Gardner River Valley to the north (left).

Geologic Interest

Beyond the Mammoth Area Trails notice board, a trailhead sign ▸7 announces your return to civilization. Continue straight ahead at the old service road intersection, ▸8 and drop down 100 yards on a narrow, rocky trail to the beginning of the gravel, one-way Old Gardiner Road, ▸9 an early stagecoach route that drops 1,000 feet in 5 miles to the park’s North Entrance station.

To return to the trailhead parking areas, ▸10 walk behind the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel and left out to the main road. Then turn right and head for Liberty Cap.

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Sepulcher Mountain/Beaver Ponds parking areas

▸2 0.1 Sepulcher Mountain/Beaver Ponds trailhead

▸3 0.3 Right at Howard Eaton–Golden Gate Trail junction

▸4 0.7 Right at Beaver Ponds Loop Trail junction

▸5 2.5 First of several beaver ponds

▸6 3.0 Last and largest beaver pond

▸7 5.0 Beaver Ponds/Clematis Creek trailhead

▸8 5.1 Straight through old service road intersection

▸9 5.25 Start of Old Gardiner Road

▸10 5.5 Return to trailhead parking areas

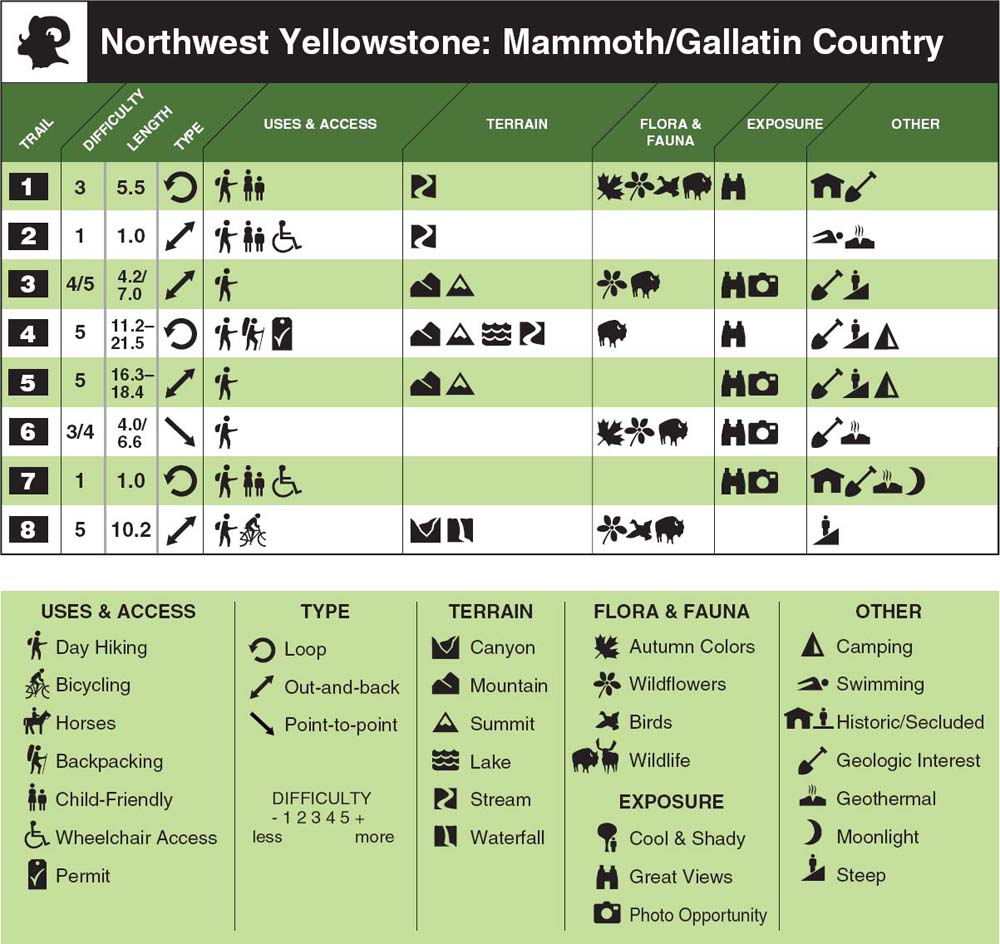

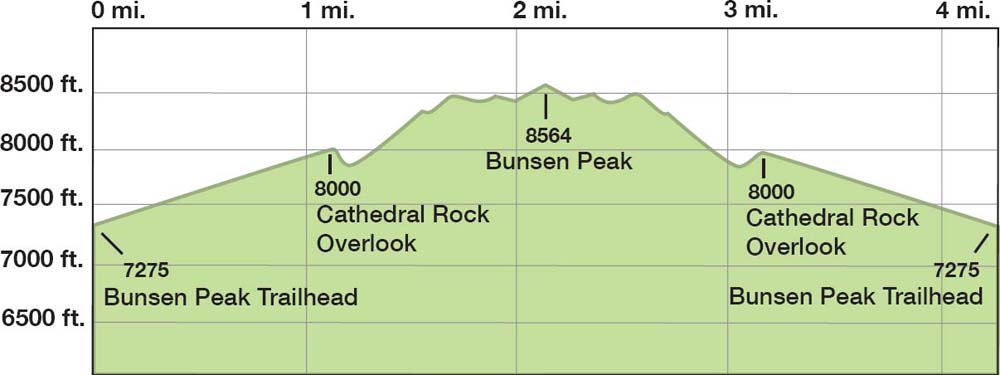

Boiling River

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

1.0 mile, 1–2 hours, including soaking

VERTICAL FEET

Negligible (±300)

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Out-and-back

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt

FEATURES

Child Friendly

Handicap Access

Stream

Swimming

Geothermal

FACILITIES

Restrooms

Picnic Tables

Yellowstone’s premier frontcountry soak is a dynamic series of five-star hot pots formed by the confluence of an icy river and an impressive thermal stream. It’s fun for the entire family and, as one of few remaining places to legally soak in the US national parks, it’s definitely not to be missed.

Best Time

Soaking in the mix of cool and near-boiling water is most enjoyable in early morning or late afternoon and best avoided in the midday summer sun. Visiting in the winter is a special treat. The area is normally open for soaking July–April, but access is restricted by the National Park Service (NPS) during periods of high spring runoff.

Finding the Trail

The springs do not appear on official NPS park maps and are not named on most other maps, but they are still easy to find. The unsigned turnoff for the parking areas is off the North Entrance Road, almost exactly halfway between the North Entrance gate and the Mammoth Hot Springs Junction, 2.3 miles from either point. Officially, these are the parking areas for the Lava Creek Trail, which leads to the bathing area. The only signs near the parking areas—the main one on the east side of the road and an overflow lot with shady picnic tables on the west side—announce the Wyoming–Montana state line (if headed south from Gardiner) and 45TH PAR ALLEL OF LATITUDE: HALFWAY BETW EEN EQUATOR AND NORTH POLE (if headed north from Mammoth). The signed Lava Creek trailhead (1N3) is on the northeast side of the road, behind the restrooms on the far east side of the gravel parking lot.

The 45th parallel also passes through Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Nova Scotia, Bordeaux, the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, Mongolia, and the northern tip of the Japanese islands.

Logistics

The Boiling River is generally open for soaking sunrise–sunset, or as late as 5 a.m.–9 p.m. in the high season. Check with the visitor center in Mammoth for the current status. Even though there are few signs, the area is one of the park’s worst-kept secrets and receives up to 200 visitors per day.

Bring drinking water, hiking sandals (flip-flops will fall off in the river), and a towel, plus a flashlight if visiting around sunset. The only changing area is inside the restroom at the trailhead.

Trail Description

Stream

From the far east side of the main parking area ▸1 on the east side of the North Entrance Road, a wide, flat gravel path heads upstream alongside the Gardner River (yes, the river and the town of Gardiner are spelled differently, for no good reason except that Montana is quirky) for about half a mile.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Mammoth Campground Trail

If you are staying at Mammoth Campground, it’s worth knowing that an alternative path, which is roughly as long as the trail from the parking lot but much steeper, descends 250 feet in elevation from the far northeastern corner of the camping area. The unsigned trailhead is across the North Entrance Road, to the left of the prominent Dude Hill, but there’s no parking here. It’s not uncommon to confuse this route with the signed Lava Creek Trail that starts at a turnout parking area just to the south. The campground office can point you in the right direction.

The steep, unnamed path from the Mammoth Campground ▸2 joins the Lava Creek Trail (also called the Boiling River Trail) just before the main trail winds around the thermal source that emanates from an off-limits cave, thought to be resurfacing runoff from distant Mammoth Hot Springs. The official Boiling River soaking area, ▸3 indicated by split-rail log fencing, is at the far end of the trail, 0.5 mile from the trailhead.

To keep the Boiling River family friendly, a couple of rules are strictly enforced: bathing suits are required, and alcohol is prohibited.

Geothermal

Signs warn of the possible presence of the pathogenic bacteria Naegleria fowleri, but no cases of the rare meningitis caused by the microscopic amoeba have ever been reported here. Just to be safe, do not submerge your head or nose below the water—the amoeba enters the brain via the nasal passages. Symptoms include a runny nose, a sore throat, a severe headache, and in the worst cases, possible death within a few days.

Swimming

Bathing in the near-scalding main thermal channel would be fatal and is prohibited. (See “Bathers Beware”). The actual composition of the dynamic bathing area changes daily and with the seasons. Seek out spots where other soakers are congregating, and beware of direct contact with undiluted thermal water. If you have trouble finding a calm spot where the current does not wash you downstream, try placing a big river stone in your lap.

Do not overdo the soaking, especially if you have to make the steep alternative hike back up to Mammoth Campground afterward. When finished, retrace your steps to the campground or parking areas. ▸4

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Boiling River/Lava Creek trailhead

▸2 0.4 Junction with trail from Mammoth Campground

▸3 0.5 Boiling River soaking area

▸4 1.0 Return to parking lots

Authors’ Favorite Legally Soakable Hot Springs in Greater Yellowstone

A soak in the natural Boiling River (Trail 2), is a nobrainer if you’re crossing the 45th parallel in the right season. It’s a brilliant hot pot in winter but is closed by spring runoff, often until midsummer. Soaking is most enjoyable here around sunrise or sunset.

North of Yellowstone, in the Paradise Valley, the family-friendly Chico Hot Springs Resort (chicohotsprings.com) is open year-round for swimming and soaking in open-air mineral spring– fed swimming pools.

South of Jackson and east of Hoback Junction, in the Bridger-Teton National Forest, two appealing year-round soaking options await (with U.S. Forest Service campgrounds nearby): the developed Granite Creek Hot Springs pools and the adjacent, undeveloped Granite Creek Falls Hot Springs. Both require a bit of driving (or snowmobiling or dogsledding in winter) to access, and the undeveloped option requires a sometimes-tricky and icy-cold creek ford, but the consensus is that the juice is well worth the squeeze.

For our money, the Bechler’s Dunanda Falls Creek Hot Springs (Trail 27) and the Ferris Fork natural whirlpool (aka Mr. Bubbles; Trail 25 for a photo) are the holy grail of primitive backcountry Wyoming soaking spots. Both require lengthy hikes to access, and there’s good camping nearby. Dunanda Falls can be visited in a day, but Ferris Fork requires a backpacking trip. En route to Union Falls (Trail 34), Ouzel Pool (aka Scout Pool) is a soothing warm-water swimming hole. Nearby, thermally fed Mountain Ash Creek is yet another swell option for refreshing weary bones.

If you’re still desperate for a hot soak but can’t find one, the hot public showers at Old Faithful Inn (see page 199) are passable surrogates, as I first discovered after bicycling through Yellowstone on a frosty July morning, when my hands were so frozen that I could no longer properly clamp down on the brakes!

Washburn Hot Springs, an optional destination for the Mount Washburn hike (Trail 18)

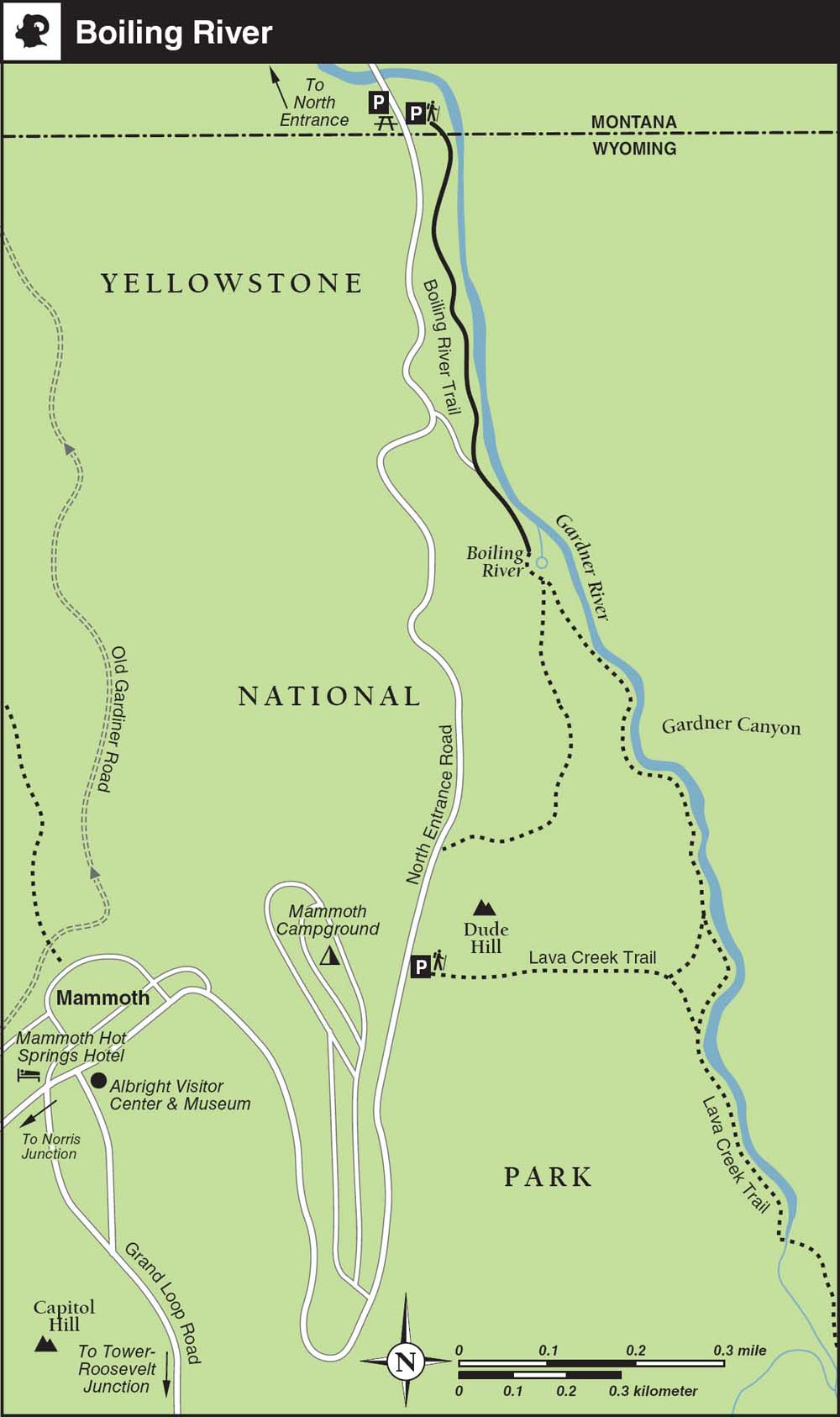

Bunsen Peak

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

4.2 miles, 3 hours, or

7.0 miles, 5.5 hours

VERTICAL FEET

±1300

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Out-and-back or Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt

FEATURES

Mountain

Summit

Wildflowers

Wildlife

Great Views

Photo Opportunity

Geologic Interest

Steep

FACILITIES

None

This scenic, heart-pumping ascent is a popular early-season altitude acclimatization route. Many folks hike in jeans and tennis shoes, but boots and trekking poles come in handy for the scree slopes, especially if you opt for the full loop or the steep side trip to Osprey Falls.

Best Time

The trail is hikable May–October: snow lingers on the trail near the summit as late as June, but the south-facing slope is free of heavy snow earlier than most peaks in the park. Other than snowmelt, there is no water along the entire route. There is precious little shade along the way, so it is best to hike early in the morning or late in the afternoon. Early afternoon thundershowers (locally known as rollers)—and lightning—are common. No matter what the weather is like at the trailhead, pack a jacket for the typically brisk weather up top.

Finding the Trail

From Mammoth, go 4.5 miles south on Grand Loop Road (US 89) and turn left into the gravel Bunsen Peak trailhead (1K4) parking area on the east side of the road (just past the Golden Gate). From Norris Canyon Road, go 16.5 miles north on Grand Loop Road and turn right into the parking area. Get here early to secure a space in this small and popular lot. If the parking area is full, try the smaller pullouts farther along the main road.

From beyond the service road barrier at the Bunsen Peak trailhead ▸1 parking area, the singletrack earthen trail splits off from Old Bunsen Peak Road at a signed junction ▸2 opposite a few waterfowl-rich ponds. Just up the hill through some sagebrush, a notice board ▸3 has a map of trails in the Mammoth region.

The patchwork “burn mosaic” pattern left by the 1988 fires, most evident from Grand Loop Road, demonstrates how supposedly catastrophic fires can actually open up new ecological niches.

The doubletrack gravel trail winds gently up through lodgepole pines in a regenerating burn mosaic created by the 1988 North Fork Fire. Thanks to the burn, in spring and summer this section is often festooned with wildflowers. The trail climbs scenically above Rustic Falls and the Golden Gate, with the Howard Eaton Trail sometimes visible off to the left above the rocky white jumble known as The Hoodoos.

Viewpoint

From here, you can also spot your destination atop Bunsen Peak, just to the right of the telecommunications equipment. Behind you are expansive views back over Gardner’s Hole, Swan Lake Flat, and beyond to the Gallatin Range. The trail flattens out through an area dotted with snags as it swings away from Grand Loop Road and heads for the summit.

Wildlife

Viewpoint

As you climb through remnants of a mature spruce–fir forest on the southwest-facing slope, heading toward the first switchbacks, watch for the stoic bighorn sheep (some with radio collars) that inhabit the scree slopes below the summit. In the fall, you can sometimes even hear rutting elk bugling as far away as Mammoth. A little bit more than halfway up, after a couple of gentle switch-backs, there is a good overlook of the Mammoth Hot Springs area; this is near the Cathedral Rock ▸4 outcropping after 1.2 miles.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Osprey Falls and Loop Trails

To make this trail into a loop, drop down the east side of Bunsen Peak after summiting, and return to the parking area via the Old Bunsen Peak Road, a wide, relatively flat, paved service road that is now unused. This abandoned road is also a popular cross-country ski route; the northern end is an alternative trailhead that is used by park employees but is largely inaccessible to park visitors. Plan on about five hours for the full loop, plus 2.8 miles and an extra couple of hours if you opt to take the steep detour down to Osprey Falls.

Steep

Beyond the overlook, the trail traverses several scree slopes. Avoid the temptation to shortcut switchbacks here as they get shorter, steeper, and more frequent. The trail tread remains good, but it is slow going—all the better for spotting ripe raspberries. As the trail wraps around the northwest slope of the summit, it passes under a power line that feeds the antennae on the first of three small summits, ▸5 at 2 miles from the trailhead.

Viewpoint

Summit

Expansive panoramic views of the Absaroka Range and Beartooth Wilderness open up to the north and northeast as you pass several precariously anchored antennae. The true summit, Bunsen Peak (8,564 feet), ▸6 is a few hundred yards farther along, down through a small, rocky saddle. At last check, the summit register consisted of a rusty metal box filled with dog-eared scraps of paper and tucked under some rocks in the middle of the remains of a lookout foundation.

Geologists theorize that Bunsen Peak, which dates back some 50 million years, is the eroded remains of a volcano. Evidence of the lava and volcanic rocks that once enclosed the peak is visible far below in the Gardner River Canyon.

Whoa! The unobstructed, 360-degree views here are superb: Electric Peak and the Gallatin Range to the northwest and west; Mount Holmes to the southwest; the Central Plateau to the south; Mount Washburn and the southern Absarokas to the southeast; and Sheep Mountain and the vast Custer Gallatin National Forest to the north. Far below to the northeast is the Yellowstone River drainage, with Swan Lake Flat and the upper Gardner River drainage to the south.

After absorbing the views, it is time to make your first and only real decision of the hike. Your options are to retrace your steps for an hour or so back to the trailhead parking area ▸7 or descend the rocky, marginally steeper northeast slope on an unsigned but well-blazed and well-maintained route through heavily burned elk habitat to join Old Bunsen Peak Road and complete a longer 8.4-mile loop. The latter option includes the detour to seldom-seen Osprey Falls (described in Trail 8).

HISTORY

HISTORY

Bunsen, Geysers, and Burners

The peak was named after German chemist and physicist Robert Wilhelm Bunsen—as was his invention, the burner (remember high school science lab?). Bunsen also did pioneering theoretical research about the inner workings of Iceland’s geysers, which his burner resembles.

Absaroka Range

The Absaroka (pronounced ab-SOR-ka) Range is named after one of the region’s numerous American Indian tribes, known today in English as the Crow.

Looking southwest from Bunsen Peak over Gardner’s Hole and Swan Lake Flat

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Bunsen Peak trailhead parking area

▸2 0.1 Left at Bunsen Peak–Osprey Falls trail junction

▸3 0.2 Straight past Mammoth Area Trails notice board

▸4 1.2 Cathedral Rock overlook

▸5 2.0 Telecommunications equipment; first of three summits

▸6 2.1 Bunsen Peak

▸7 4.2 Return to parking area

Cache Lake and Electric Peak

TRAIL USE

Hike, Backpack

LENGTH

11.2 miles, 6 hours, or

21.5 miles, 2 days

VERTICAL FEET

±3,670

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Out-and-back

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt, Rock

FEATURES

Backcountry Permit

Mountain

Summit

Lake

Stream

Great Views

Geologic Interest

Wildlife

Steep

Camping

FACILITIES

None

Superhumans can tackle Electric Peak (without Cache Lake) as a day hike, but even fit hikers will likely want to make this a moderate overnighter, combining some of the park’s best summit views with a lovely, forest-lined lake.

Best Time

Mid-July–September is the best time to climb Electric Peak. Before and after these months, you should be prepared to encounter snow on the peak. Check the weather forecast before attempting Electric Peak, and don’t consider the ascent if an afternoon storm is brewing. Lightning is a real possibility; there’s a reason it’s called Electric Peak.

Finding the Trail

From the north, go 4.5 miles south on Grand Loop Road from Mammoth (just past the Golden Gate) and turn left into the gravel Bunsen Peak trailhead parking area on the east side of the road. From the south, go 16.5 miles north from Norris Canyon Road on Grand Loop Road and turn right into the parking area. Get here early to secure a space in this small and popular lot. If the parking area is full, try the smaller turnouts farther south along the main road.

Logistics

The best way to tackle Electric Peak is to get a back-country permit for one of the two campsites (1G3 and 1G4) at the base of Electric Peak, allowing you to ascend the peak the next morning when skies are normally at their clearest.

Both Electric Peak and Cache Lake are in the Gallatin Bear Management Area, which means that from May 1 to November 10 hiking is allowed only on designated trails (this includes the trail up to Electric Peak). Groups of four or more are recommended. Bring bear spray and take all the normal precautions, including hanging your food on the provided food poles and sleeping 100 yards from where you cook.

Trail Description

Stream

The hike starts at the Glen Creek trailhead (1K3) ▸1, across the road from the busy Bunsen Peak parking area. The trail starts off as a doubletrack through the sagebrush valley of Swan Lake Flat, following the meandering Glen Creek. After about 100 yards you continue straight at the junction with the Howard Eaton Trail ▸2, beside the trailhead information board (see Trail 6). As the trail swings to the right you’ll follow the power lines and metal posts used to mark the winter cross-country skiing route. Pass underneath the power lines, and ignore the path to the right to meet the Snow Pass junction. ▸3 Trails branch left here to Fawn Pass and right to Mammoth, but our trail continues straight. Continue straight again a minute later as a second shortcut trail leads off to join the Mammoth Trail and then head into the forested gully ahead.

lake

The next section of trail climbs gently above a lush, green, meandering valley, where you might spot moose in the morning and afternoon. Cross a small stream to the junction with the Sepulcher Mountain Trail, ▸4 and take the left branch, continuing up the Glen Creek valley through patches of meadow and forest as Electric Peak looms on the horizon. After a short climb through forest, you meet the signed junction with Cache Lake. ▸5 Depending on the time, you could visit the lake now or detour to it on the way back from Electric Peak. The trail is signposted as 1.2 miles to Cache Lake, ▸6 but it’s more like 0.7 mile. Electric Peak towers above the calm waters, allowing you to reflect on tomorrow’s climb and maybe spot moose browsing the lake’s shores. If you decide not to tackle Electric Peak, the out-and-back walk to Cache Lake is a moderate, largely flat day hike of 11.2 miles.

Looking back toward Swan Lake from Electric Peak

Camping

Back at the junction ▸7 with Cache Lake, follow the signed trail toward Sportsman Lake, climbing a forested gully lined with fallen trees. You soon reach the top of a spur ridge where the signed junction to Electric Peak ▸8 leads off to the right. If camping, continue straight at this junction, and descend to the Gardner River. The river ford here isn’t difficult, but it helps to have hiking poles if you don’t want to get your feet wet. Look for an easier crossing just before the ford, at a small clearing with a sign that says NO CAMPING BUILD NO FIRES. Campsite 1G3 is signed just after the stream crossing, and site 1G4 is a couple of minutes farther to the right. ▸9 Both campsites are secluded and about a 15-minute walk from the turnoff to Electric Peak, a total of about three hours from the trailhead.

Steep

The next morning, return the 15 minutes up to the junction ▸10 with Electric Peak to start the ridge climb. Fill up with water at the Gardner River first because there’s no water once you start climbing the ridge. Figure on a three-hour climb, gaining some 2,800 feet, followed by a two-hour descent. The trail climbs above last night’s campsite, dipping briefly into a side valley and then curving around a cliff area; be sure to take the main trail to the right, not the game trails that stay lower on the hillside. As the views open up, you’ll see Gray Peak to the southwest, Electric Pass and the trail leading to Sportsman Lake to the west, and views of Swan Lake Flat to the southeast. As you pass the final clump of trees, the trail steepens and heads straight up a gully along the spine of the ridge, sometimes crossing the ridgeline to the left. Essentially you are headed straight up the ridgeline. To the right you can see Cache Lake below and Sepulcher Mountain beyond.

Viewpoint

Summit

Finally you reach a saddle just before the peak proper, which is a good place to take a breather. From here on, you need to be comfortable with basic route-finding skills and a bit of scrambling. The faint trail follows the west side of the final ridge, and you need to keep your eyes open to follow it; if you find yourself doing anything more than a scramble, then you are on the wrong path. Just before the rust-colored summit, you climb one last section on unstable talus, which requires some nerves but no technical skills. At the 10,969-foot summit ▸11 you’ll find a couple of memorials and some antlers, along with fabulous views down to Gardiner, the Absaroka Mountains, the Paradise Valley, and beyond—essentially the whole northwest quarter of the park. Keep your eyes peeled for bighorn sheep and pikas. Savor your achievement, for this is truly a mighty view.

Wildlife

From the summit you simply return to Glen Creek trailhead ▸12 the way you came, with the option of the 1.4-mile detour to Cache Lake if you didn’t visit it on the way up. Figure on a 4.5-hour walk from the summit back to the trailhead, longer if you detour to Cache Lake.

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Glen Creek trailhead

▸2 0.1 Junction with Howard Eaton Trail

▸3 2.1 Snow Pass/Fawn Pass junction

▸4 2.9 Junction with Sepulcher Mountain Trail

▸5 4.9 Junction with Cache Lake

▸6 5.6 Cache Lake (0.7-mile detour)

▸7 6.3 Junction with Cache Lake

▸8 7.2 Turnoff to SE Electric Peak Trail

▸9 7.3 Campsites

▸10 7.4 Turnoff to SE Electric Peak Trail

▸11 11.6 Electric Peak summit

▸12 21.5 Glen Creek trailhead

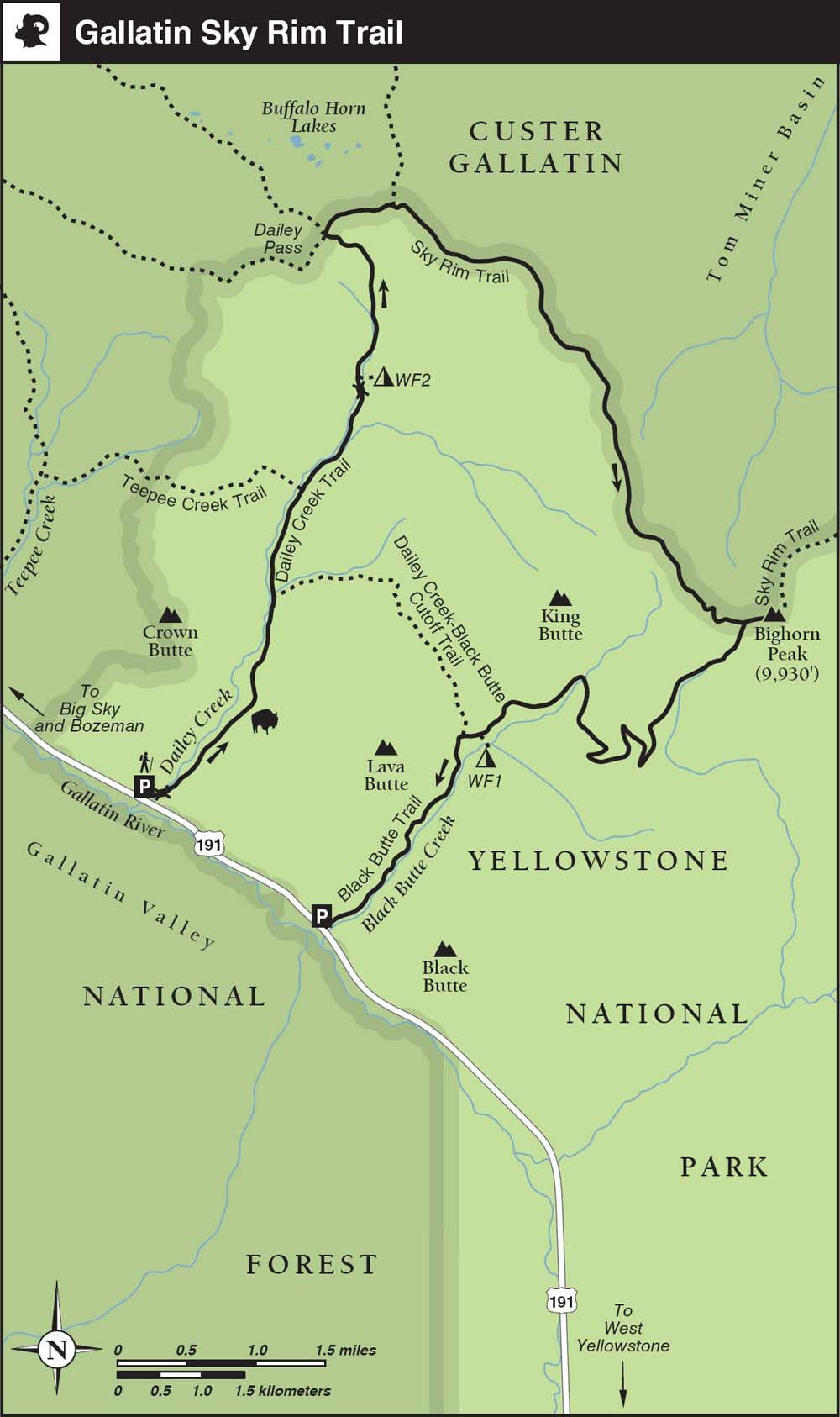

Gallatin Sky Rim Trail

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

16.3 or 18.4 miles, 9–11 hours

VERTICAL FEET

±3,835

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt

FEATURES

Mountain

Summit

Great Views

Photo Opportunity

Steep

Geologic Interest

Camping

FACILITIES

None

This spectacular trail on the edge of the park is a long day’s hike, but don’t be put off—the rewards are some of Yellowstone’s most rugged and impressive scenery, with mountain views spilling deep into Montana.

Best Time

The ridgeline is free from snow mid-July–September. It’s a good idea to get an early start as this is a long hike and afternoon clouds can obscure views. Check the weather forecast before setting off. Much of the hike is on an exposed ridgeline and is not a place to be caught in a thunderstorm.

Finding the Trail

To get to this far northwestern section of the park, you actually have to leave it, exiting the park at West Yellowstone and then driving 30 miles north on US 191 toward Big Sky and Bozeman. From the north, head south 18 miles from the Big Sky turnoff and park in the Dailey Creek Trailhead (WK1). It’s a great hike to slot in between the park and Bozeman.

Logistics

It’s a good idea to bring Beartooth Publishing’s Bozeman, Big Sky, West Yellowstone map, not to navigate this trail but to help identify the surrounding ranges and peaks. Note that the park’s mile markers are a bit suspect here—the total trail distance is anywhere from 16 to 19 miles, depending on which of the signs you believe. There is no water on the ridgeline, so pack an extra bottle. There is no entry fee for this section of the park.

This northwestern section of Yellowstone Park was added in 1927, making it the most recent section of the park.

Trail Description

From the parking lot ▸1 the trail heads up Dailey Creek, crossing the stream on a log bridge after a few minutes as Crown Butte rises to the left. After 40 minutes or so, you pass the junction with the Dailey Creek–Black Butte Cutoff Trail, ▸2 where you will rejoin the main trail at the end of the loop if you don’t want to arrange a shuttle or walk along the road. After another 20 minutes, a side trail branches left to Teepee Creek ▸3 and the Yellowstone National Park boundary. As you continue straight up the valley, the terrain starts to close in and you can see the ridgeline wall at the end of the valley. As you cross Dailey Creek on a log bridge, be sure to fill your spare water bottle as this is the last reliable water source, especially in late summer. Just 15 minutes farther is backcountry campsite WF2, ▸4 next to a trickle of a stream.

Camping

The trail arcs left through patches of forest and meadow before swinging left to make the gradual ascent to Dailey Pass. ▸5 At the top of the pass you’ll be faced with a red-and-white park boundary post and a four-way junction. Straight on takes you down to dispersed camping sites in the Buffalo Horn Lakes region, if you want to make this an overnighter. Our hike follows the right-hand trail climbing along the ridgeline.

Fine views start to open up on the dirt ridge toward the Taylor Peaks and Monument Mountain of the Madison range in the Lee Metcalf Wilderness, plus Sphinx Mountain, Lone Peak, and Ramshorn Peak to the north.

Viewpoint

A 30-minute uphill section with a couple of switchbacks takes you up past volcanic breccia bluffs to join the ridgetop Sky Rim Trail. ▸6 To the east is the Tom Miner Basin, with Ramshorn and the Twin Peaks to the left, and Paradise Valley and the Absaroka Mountains beyond. A park sign says you have walked 7 miles, one of several examples along this trail where the signed distances are unreliable.

Petrified tree, as seen from the ridgeline of the Sky Rim Trail

CREDIT: Bradley Mayhew

Dailey Creek (sometimes misspelled Daly Creek) was named for Andrew Dailey, an early homesteader who wintered in the Paradise Valley in 1866 and later returned to settle there.

You might assume that the uphill sections are behind you at this point, but the next 5 miles of ridgeline walk are almost all up and down. As you climb again through patchy forest, look for a faint trail to the right that opens up to views of a fabulous petrified tree, buried 50 million years ago by a volcanic lahar (mudflow) and part of the wide-ranging Gallatin Petrified Forest.

Photo Opportunity

The trail passes the first of many General Land Office metal survey posts, climbs to a crest, and then descends, only to climb again as it traverses several minor peaks and dips. The top of one peak offers 360-degree views and a pleasant ridgetop stroll before descending and climbing steeply again. As you descend again, look to the right to see two arches eroded in a breccia curtain, part of a wider bowl of volcanic rock outcrops.

Geologic Interest

Steep

As you climb onto a grassy plateau, the path becomes increasingly faint; if in doubt keep heading for the park boundary markers. It feels like you are on top of the world here, but the bad news is that from here you descend to a col, only to then make a very steep 600-foot climb—so steep in fact that there’s not even a trail; you just have to follow the orange markers straight up the hillside. Atop the plateau you’ll meet an important junction, ▸7 where the Sky Rim Trail and Black Butte Trail converge. Figure on six hours of hiking to this point.

Summit

From the junction it’s well worth making the 10-minute detour on the daunting-looking trail that winds around dramatic, crumbling cliffs to the summit of Bighorn Peak (9,889 feet). ▸8 From here you can see the Sky Rim Trail continuing along the ridgeline to Shelf Lake, 3 miles away, with Sheep Mountain (and its telecom tower) just beyond and Electric Peak visible to the right.

Viewpoint

Return to the junction and get ready to say goodbye to the high ground. The faint trail descends the grassy hill, dropping as it curves to the right to follow the ridge, but never dropping too steeply, traversing sagebrush hills interspersed with patches of forest. Keep your eyes open for bears on this section.

Camping

To the right King Butte towers like a giant melted candle. Around 1.25 hours from the plateau, you reach two streams, your first water source for six hours or more. The trail descends through pockets of aspen to backcountry campsite WF1 and then crosses a meadow to the junction ▸9 with the Dailey Creek–Black Butte Cutoff Trail. From here it’s 2 miles down the valley to Black Butte trailhead ▸10 and US 191, where you can meet your vehicle or hike along the highway 1.7 miles to reach the Dailey Creek Trailhead. Alternatively, hike 2.2 miles uphill via the Dailey Creek–Black Butte Cutoff Trail and its patrol cabin to rejoin the Dailey Creek Trail, and descend 1.8 miles down the valley to the Dailey Creek trailhead. Figure on a total of 2.5 hours of walking from the plateau to the trailheads.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Overnight Options

It’s possible to turn this hike into an overnighter by booking park backcountry campsites WF1 or WF2, in Black Butte Creek and Dailey Creek respectively, but both are only 2 miles from the highway, so it’s hard to justify carrying all the extra weight. A better option for an overnight backpacking trip is to detour to the Buffalo Horn Lakes region and its free, dispersed camping, just outside the park boundary in the Custer Gallatin National Forest. One other option is to continue from Bighorn Peak along the Sky Rim Trail 3 miles to Shelf Lake and its two backcountry campsites, WE7 and WE5. This adds 6 miles to this hike.

The Gallatin Sky Rim Trail winds along a series of ridgelines, offering fine views on either side.

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Trailhead parking lot

▸2 1.8 Junction with Dailey Creek–Black Butte Cutoff Trail

▸3 2.6 Junction with Teepee Creek Trail

▸4 3.5 Campsite WF2

▸5 4.9 Dailey Pass

▸6 5.7 Sky Rim Trail

▸7 10.0 Junction with Black Butte Trail

▸8 10.2 Bighorn Peak

▸9 14.4 Dailey Creek–Black Butte Cutoff

▸10 16.3 Black Butte trailhead, or 18.4 Dailey Creek trailhead

Howard Eaton Trail

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

4 miles, 2 hours, or

6.6 miles, 4 hours

VERTICAL FEET

+250/–850

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Point-to-point or Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt

FEATURES

Autumn Colors

Wildflowers

Wildlife

Great Views

Photo Opportunity

Geologic Interest

Geothermal

FACILITIES

None

Named after a pioneering Yellowstone outfitter and guide, this short downhill section of Yellowstone’s longest trail (much of which is no longer maintained because it parallels Grand Loop Road) traverses a wide variety of scenic terrain from the Golden Gate to Mammoth Hot Springs.

Best Time

The trail is hikable May–October; some exposed stretches make early morning and late afternoon the most pleasant times to hike here.

Finding the Trail

From the north, go 4.6 miles south on Grand Loop Road from Mammoth and turn right into the busy Glen Creek trailhead (1K3) parking turnout (just past the Golden Gate). From the south, go 16.4 miles north from Norris Canyon Road on Grand Loop Road and turn left into the parking turnout.

Logistics

Arranging a car shuttle is the first order of business to make this an easy hike; leave a car in one of the parking turnouts near the bottom of the Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces. Otherwise, you can try to arrange a ride from Mammoth uphill to the Glen Creek trailhead before you start hiking.

Snow Pass and Terrace Mountain Loop

If you are unable to arrange a car shuttle, you can loop around between Clagett Butte and Terrace Mountain on the Snow Pass Trail instead of finishing the hike in Mammoth. This option adds 2.6 miles and up to two hours because of the added elevation gain of more than 1,000 feet, which nearly doubles the difficulty of the hike.

The Hoodoos were named for their ghostly appearance but bear little resemblance to the park’s other natural rock pinnacles, which are more classical examples of the form.

Trail Description

From the Glen Creek trailhead, ▸1 head west through the sagelands of Swan Lake Flat toward Quadrant Mountain (10,216 feet) and the Gallatin Range.

After a few hundred yards, you reach a notice board and the Howard Eaton–Fawn Pass Trail junction. ▸2 Turn right and climb sharply several hundred feet into the forest. Bunsen Peak juts up to your right, with the lichen-encrusted Golden Gate and Rustic Falls gorge far below.

Geologic Interest

Stop to admire the expansive views of the Gallatins to the west, where the trail reaches its high point (7,500 feet) along the shoulder of Terrace Mountain (8,006 feet). After 1.3 miles, the trail drops down into the eerie rockscape known as The Hoodoos, ▸3 a massive jumble of ancient limestone hot-spring deposits that sheared off of Terrace Mountain during landslides. The travertine boulder field provides prime habitat for yellow-bellied marmots (also known as rock chucks) and is a favorite playground of rock climbers.

Wildlife

Beyond The Hoodoos, the trail jogs left, away from Grand Loop Road, and starts to descend gradually through a burn area and aspen groves to another notice board and the Snow Pass Trail junction, ▸4 2.8 miles from the trailhead. Watch for moose and, in late summer, black bears (and less frequently grizzlies) prowling this scenic stretch for buffalo berries. To be safe, make plenty of noise where sight lines are restricted.

If you are not completing the loop option, keep straight downhill 0.5 mile past the junction, through pine and juniper forest, to reach a short spur trail for the Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces. ▸5 You can take a detour here along Upper Terrace Drive, but the most interesting thermal features are more accessible at the end of the hike, near Liberty Cap. As the trail wraps around the Upper Terraces, you will enjoy views to the north of the historic Fort Yellowstone area.

Terrace Mountain was an active thermal area 65,000 years ago. Notice how the bright grayish-white travertine of The Hoodoos is similar to the dormant areas around the Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces.

Drop another 0.5 mile past the travertine Narrow Gauge Terrace through sagebrush and shady Douglas-fir forest to the Beaver Ponds Trail junction. ▸6 Turn right and continue 0.2 mile down Clematis Gulch to end up at the Sepulcher Mountain trailhead. ▸7

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Glen Creek trailhead parking turnout

▸2 0.3 Right at Howard Eaton–Fawn Pass Trail junction

▸3 1.3 The Hoodoos

▸4 2.8 Straight at Snow Pass Trail junction

▸5 3.3 Straight past Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces

▸6 3.8 Right at Beaver Ponds Trail junction

▸7 4.0 Arrive at Sepulcher Mountain trailhead

Mammoth Hot Springs

TRAIL USE

Hike

LENGTH

1.0 mile, 1–1.5 hours

VERTICAL FEET

±300

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Boardwalk

FEATURES

Child Friendly

Handicap Accessible

Great Views

Photo Opportunity

Historic Interest

Geologic Interest

Geothermal

Moonlight Hiking

FACILITIES

Visitor Center

Restrooms

Picnic Tables

Phone

Water

While many of Yellowstone’s most famous hydro-thermal areas wow audiences with their dramatic antics and predictable, instantly gratifying performances, Mammoth’s mercurial hot-spring terraces are impressive more for their important place in the history of the park and their long-term natural development. A network of boardwalks provides numerous options for exploring the most accessible thermal area in the northern half of the park.

Best Time

You can explore at least some portion of the terraces year-round. When boardwalks are iced over in winter, the fringes of the thermal area are fascinating to explore on skis or snowshoes. There is no shade on the boardwalks, so bring plenty of water and sun protection.

Finding the Trail

From Mammoth Junction, either walk 0.25 mile south to the Lower Terraces boardwalk or drive 2 miles south on Grand Loop Road toward Norris. Go past a paved overlook turnout, and turn right at the well-signed entrance gate to reach the main Upper Terrace Drive parking lot, where the route begins.

Logistics

All visitor facilities are located near the parking lots at the Upper and Lower Terraces. Rangers lead free, 90-minute walks (no reservations necessary) that depart from the Upper Terraces parking lot at 9 a.m. daily between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

Boardwalks crisscross the travertine terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs.

Before heading out, pick up a helpful Mammoth Hot Springs Trail Guide ($1 donation requested) from the visitor center or the metal box below the map on the east side of the main parking area.

After surveying the views of Fort Yellowstone and the Main Terrace from the overlook (6,590 feet) near the main parking area, ▸1 follow the boardwalk to the right, past the short boardwalk leading to the white and orange Cupid Spring, down to the first of three platforms overlooking the travertine terraces below the source of Canary Spring. ▸2 Note: there is a less steep, wheelchair-accessible boardwalk by the parking area at the junction with the main road.

Geothermal

Geologic Interest

Named for its bright yellow color, the huge mound of Canary Spring owes its brilliance to filamentous bacteria living around its vent. The rest of the impressive geothermally heated runoff channel exhibits more oranges, browns, and greens, indicating the presence of thermophiles that prefer cooler temperatures. Grey sinter remains in areas where water has stopped flowing. The lower overlook platform provides the best up-close look at how calcium carbonate, which dissolves from the sedimentary limestone layers, crystallizes on the plant matter that falls onto the terraces.

Geologists speculate that the hot water surfacing here in the small fissures may flow as far as 21 miles underground along a fault line from the Norris Geyser Basin. Some of the same water is thought to resurface farther downhill at the Boiling River.

It’s estimated that as many as 65 species of algae and bacteria live in Mammoth’s hot springs, and that up to 2 tons of travertine are deposited here daily.

Retrace your steps along the boardwalk back up to the parking area and main overlook, ▸3 where a different boardwalk ▸4 leads straight ahead to another overlook of the mostly dormant New Blue Spring. Follow the stairs down to the Lower Terraces and another junction, ▸5 where there is yet another trail map signboard. To your left is the multilayered Cleopatra Terrace; to your right is Minerva Terrace, definitely a highlight of the tour.

Named for the Roman goddess of artists and sculptors, many of Minerva’s ornately layered terraces took shape in the early 1990s. At last look, the spring was inactive, but a photo on the interpretive sign shows what the area looked like during a period of activity in 1977. Believe it or not, during one particularly active cycle, minerals deposited by Minerva buried the boardwalk you are now standing on. In the dry areas, look for elk tracks in the gravel and evidence of how fragile the crust is where bison hoofs have caused cave-ins.

Canary Spring: Family at the lower Canary Spring Overlook

From the junction, follow the paved path down to your right about 100 yards to Palette Spring, ▸6 a good example of how thermophiles (heat-tolerant bacteria) lend different colors to runoff channels.

Back at the trail map sign, detour to your right down the steep gravel path for a closeup look at the dormant, 37-foot-tall hot-spring cone that was named Liberty Cap ▸7 in 1871 for its resemblance to the peaked caps worn during the French Revolution. There are picnic tables across the road near the dormant Opal Terrace (a favorite springtime hangout of elk), and restrooms to the left past the bus parking area. The easiest way to do this hike is to get picked up here or get dropped at the beginning of the hike and walk all the way back to the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Lower Terraces from Mammoth

You can walk five minutes from the visitor center in Mammoth and join this hike halfway, at Liberty Cap. If you want to explore more, you can bicycle or drive around the 1.5-mile, one-way Upper Terrace Drive past several more active hot-spring terraces.

The bubbling visible at the surface of the hot springs is due to carbon dioxide gas expanding, not water boiling. Groundwater temperatures have been measured at around 170°F.

Retrace your steps back past Palette Spring, and turn left on the boardwalk at the junction ▸8 to loop around the lower side of Minerva Terrace. Even where all appears dry and dormant, watch closely for steam puffing out of small cracks in the hillside, hinting at future hydrothermal activity. At Jupiter Terrace, ▸9 interpretive signs display historical photos and explain the terrace’s varied cycles of activity.

Head right (uphill) on the boardwalk, and climb the stairs starting at the foot of the Main Terrace to return to the Upper Terrace overlook and parking area. ▸10

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Upper Terrace Drive parking area

▸2 0.1 Right on boardwalk to Canary Spring

▸3 0.2 Back at parking area and overlook

▸4 0.25 Straight on boardwalk to New Blue Spring overlook

▸5 0.4 Left on paved path at Cleopatra–Minerva Terrace junction

▸6 0.5 Right down gravel path at Palette Spring junction

▸7 0.6 North (right) on gravel path to Liberty Cap; return by retracing your steps

▸8 0.7 Left on boardwalk at Palette Spring junction

▸9 0.85 Right on boardwalk at Mound–Jupiter Terraces junction

▸10 1.0 Return to Upper Terrace Drive parking area

Osprey Falls

TRAIL USE

Hike, Bike

LENGTH

10.0 or 10.2 miles, 5–7 hours

VERTICAL FEET

±850

DIFFICULTY

– 1 2 3 4 5 +

TRAIL TYPE

Out-and-back or Loop

SURFACE TYPE

Dirt, Road

FEATURES

Canyon

Waterfall

Wildflowers

Birds

Wildlife

Steep

FACILITIES

None

This hike on an old service road ends with a steep out-and-back drop to the secluded base of a scenic falls at the head of an impressive canyon. The route can be extended to a slightly longer and more strenuous loop by combining it with Trail 3 to see both sides of Bunsen Peak.

Best Time

Old Bunsen Peak Road is open for travel whenever the park is open to visitors. The hiking and biking season runs roughly May–October. On hot days and for spotting wildlife, it’s best to hike in the early morning or late afternoon.

Finding the Trail

From the north, go 4.5 miles south on Grand Loop Road from Mammoth and turn left into the Bunsen Peak trailhead parking area on the east side of the road (just past the Golden Gate). From the south, go 16.5 miles north from Norris Canyon Road on Grand Loop Road and turn right into the parking area. If the parking area is full, try the smaller Glen Creek trail-head turnout on the opposite side of the road.

Logistics

There’s no water at the trailhead, and the only water along the trail is at the falls. If doing this hike as part of the full Bunsen Peak Loop (starting as described in Trail 3), watch carefully for orange blazes (metallic flags tacked to tree trunks) marking the way to the cutoff for Osprey Falls as you finish the descent off the back side of Bunsen Peak. Bicyclists are allowed on the gravel service road but must park their bikes before descending to Osprey Falls. The northeast end of Old Bunsen Peak Road is an alternative trailhead, used primarily by park employees.

OPTIONS

OPTIONS

Bunsen Peak Loop

Ambitious hikers looking for a full-day ramble can tack a detour to Osprey Falls onto the full Bunsen Peak Loop (a combination of this route and Trail 3. Plan on at least two extra hours for the steep 1,300-foot climb to Bunsen Peak.

Trail Description

Beyond the service road barrier at the Bunsen Peak trailhead parking area, ▸1 continue straight on Old Bunsen Peak Road at the signed Bunsen Peak Trail junction ▸2 across from some waterfowl-rich ponds.

Wildlife

The relatively level gravel service road heads east out across the rolling sagebrush meadows of Gardner’s Hole and passes through prime bison and elk habitat. Watch for scats and tracks along the road. This stretch of abandoned road is also a popular mountain bike and cross-country ski track, so you could easily combine hiking and biking on this trip.

Canyon

After skirting a couple of ponds, the road swings around the foothills and southern base of Bunsen Peak (8,564 feet). The regenerating forest is more than head-high here, obscuring the views in places. Eventually the road approaches an overlook that affords a glimpse of the Gardner River at the bottom of Sheepeater Canyon.

The canyon is named after the park’s only original year-round residents, a subgroup of the Shoshone Nation who referred to themselves as the Tukuarika but were called the Sheepeater by Western settlers. In 1871, the year before Yellowstone was declared a park, they were forcibly relocated to the Wind River Reservation.

Although osprey rarely nest near their namesake falls, if you’re lucky you might spot them circling over the river looking for prey, as well as bald eagles.

Besides bighorn sheep, the Tukuarika hunted bison, elk, and deer with bows fashioned from ram’s horns and ornamented with porcupine quills, using arrows tipped with obsidian. Evidence of chutes used to herd bighorn off cliffs has been uncovered near Rustic Falls.

At the signed Osprey Falls–Bunsen Peak Trail junction, ▸3 3.4 miles from the trailhead, turn right where the old road continues straight ahead and drops down into a National Park Service (NPS) maintenance area. The road dead-ends at an alternative trailhead that is used by NPS employees but that visitors are discouraged from using. The rim of Sheepeater Canyon ▸4 is several hundred yards beyond the bike parking rail. Bikes are not allowed past this point due to the extreme steepness of the trail to Osprey Falls.

Do not let the posted signs warning about treacherous conditions on the Osprey Falls Trail scare you. Yes, the steep trail’s tread is in poorer condition than most of the superbly maintained trails in the park, but with a reasonable dose of caution it is safely manageable under normal circumstances. It plunges nearly 800 feet in a little over 0.5 mile to the base of the impressive 150-foot Osprey Falls, ▸5 a total of 5 miles from the trailhead.

Waterfall

The misty area near the base of the falls makes a fine spot for a picnic as you ponder the stiff climb back out to the trailhead parking area. ▸6

MILESTONES

MILESTONES

▸1 0.0 Start at Bunsen Peak trailhead parking area

▸2 0.1 Straight on road at Bunsen Peak–Osprey Falls Trail junction

▸3 3.4 Right at Osprey Falls–Bunsen Peak Trail junction

▸4 3.8 Sheepeater Canyon rim

▸5 5.0 Osprey Falls

▸6 10.0 Return to trailhead parking area