As the day was fast approaching when the release of the new FORTITUDE story would become imperative, we now thought that the time had arrived for GARBO to leave his prison cell, bearing in mind that it would take some time to restore him fully to life and action. On 12th July Madrid received the news from agent Three: ‘Widow just reported surprising news that GARBO was released on the 10th and is back at his hotel…. My instructions from him are to give agent 4 (1) ten days’ holiday and return immediately to Glasgow and await orders there.’1 On 4th July, as a result of a conversation which he had heard in a public house about some bombs which had fallen at Bethnal Green during the previous night, GARBO had gone to investigate. He had casually questioned a man in the crowd, who unluckily for him had turned out to be a plainclothes policeman. The latter’s suspicions had been further aroused by GARBO swallowing a piece of paper on which he had previously made some notes. In his zeal the police officer who had made the arrest had detained GARBO at the Police Station for a longer period than he was legally entitled to do without a warrant, a fact that was pointed out to GARBO by one of his fellow prisoners. On the latter’s advice he had written a letter to the Home Secretary stating his grievance to which reference has already been made. This action had resulted in a marked change in the attitude of the Police. In an interview with the Chief of the Station GARBO had explained that he had had a conversation several days before with J (3) in which he had questioned the efficacy of the defence measures used against the new weapon. In order to prove his point he had decided to make some personal observations and this had led to his ultimate arrest. J (3) was of course able to corroborate the conversation and so GARBO had been able to leave the prison without a stain on his character. In taking leave of the Chief of the Station, the latter admitted that the Police had been over-zealous in the fulfilment of their duties and GARBO ended his account of the interview with the remark: ‘As I did not understand half of what he was saying, I reacted to his amiability by thanking him for having had me in the prison, which, when I look back now, I see how ridiculous my words must have been.’2

The effect of GARBO’s arrest was precisely that hoped for. Nearly all the other agents had been asked to report bomb damage. On 12th July BRUTUS was told: ‘Discontinue from now on, all reports of damage caused by flying bombs and send us only information about location of troops, &c., &c., in accordance with instructions given.’3 As soon as the Germans had received details of GARBO’s arrest and subsequent release, they adjured him to ‘cease all investigation of the new weapon’.4 Similarly TATE was informed that messages about troops were of more interest than those about flying bombs.5

By the middle of the month the time had arrived when we could no longer with safety withhold the full story. Before 9th July, one division from each of the army corps6 in the fictitious FUSAG had sailed. Allowing one day for the sea passage we were bound to assume that all these divisions would be identified in France by 16th July. It had by now become very difficult to maintain the press stop on General Patton and the Ministry of Information thought it would be impossible to hold it beyond 20th July. The FORTITUDE SOUTH II wireless links were due to open on 21st July. Finally GARBO and BRUTUS had both come to life again, the latter having returned from Scotland on the 15th.

These points having been put to 21 Army Group, it was agreed that the release of FORTITUDE SOUTH II might begin on 18th July. It was arranged that BRUTUS should deliver the story in a series of messages sent between the 18th and 21st of the month, while GARBO, who was still out of touch with his transmitter, would meet his friend 4 (3) and give his own version in a letter which would reach the Germans at the end of the month and would corroborate what they had already heard from BRUTUS.

BRUTUS’s report ran as follows: ‘I learnt at Wentworth that FUSAG has undergone important changes owing to the necessity for sending immediate reinforcements to Normandy. So far as I know, the Supreme Commander, namely Eisenhower, decided that it was necessary to send urgently a part of the forces under FUSAG, who would pass under the command of a new army group. These forces will be replaced in FUSAG by new units arriving from America and by British reserves. No exact details but I can confirm that FUSAG will include the Ninth American Army, the Fourteenth American Army and the Fourth British Army. FUSAG, changes in the Command: I sup pose that Eisenhower and Patton were not in agreement over the change in the Order of Battle because Patton has been replaced by General McNair as Commander-in-Chief of FUSAG. I have discussed, with my colonel, the latest changes which have caused a good deal of bother at our headquarters. He tells me that Montgomery demanded immediate reinforcements in Normandy in such a fashion that it was necessary to send units from FUSAG which were already in the South of England, notably the First Canadian Army and a large part of the Third American Army. The fresh units in FUSAG will take up the duties of the units which have been despatched. The staff command of FUSAG remains unchanged. The Fourteenth American Army has already removed towards East Anglia, to the area formerly occupied by the Third Army. The headquarters are at Little Waltham. The Fourth British Army is also in the South. My colonel considers that the fresh units in FUSAG will be ready to take the offensive towards the beginning of August.’7 Before the transmission of BRUTUS’s message had been completed, the Pariser Zeitung, the German newspaper printed in Paris during the occupation, published the following article: ‘Patton’s Army in the Bridgehead. In the Normandy peninsula it is noteworthy that amongst the enemy reinforcements which have been employed in the last few days are divisions which apparently no longer form part of Montgomery’s Army Group but are already under Eisenhower’s other Army Group, which is under the command of the American Patton. Whereas the enemy army group which has so far been fighting in the bridgehead was called the “South-Western invasion army” because it was located in the South-West of England, these new divisions probably belong to the “South-Eastern invasion army” and their employment shows to what extent the German defence in Normandy is depleting the enemy forces.’ No higher tribute could have been paid to the success of FORTITUDE than that the Germans should have used Patton’s Army Group to support their own propaganda. But the passage also shows that BRUTUS’s message had not gone too soon. A clearer proof that the release of FORTITUDE SOUTH II was accurately timed is to be found in the OKH Intelligence Summary for 27th July, which states that ‘according to captured documents confirmed by credible Abwehr reports’ the American Third Army had now transferred to France.8

Jodl stated under interrogation on 11th December, 1945, that he considered the Pas de Calais (FUSAG) threat to be over by the middle of July when formations of Third US Army began to appear in Normandy. He admitted, reluctantly, as his loyalty to Hitler remained unshaken, that the continued retention of a large part of the Fifteenth Army in the Pas de Calais after that date was due to the Fuehrer’s own persistent belief in the imminence of a second landing. It would probably be unfair to put the whole blame on Hitler, for the Intelligence Summary of 27th July, after drawing attention to the large scale on which Normandy was now being reinforced, went on to say: ‘Patton’s Army Group is thus gradually losing its potential strength for large-scale operations and it is therefore unlikely that it will be committed against a strongly fortified and defended sector of the coast in the near future. More probably it will be subjected to further weakening in favour of the Normandy operations and will be held ready to attack a sector of the Channel coast when such a sector has definitely been laid bare. Patton’s Army Group represents therefore, in the opinion of this Department, no acute danger. It must, however, be remembered it can gradually be rehabilitated by shipments from America and made ready for large-scale operations. It will then probably consist of two armies, presumably the Fourth English in the South-East of England, and the Ninth or Fourteenth American in the area between the Thames and the Wash.’9 This is the first recorded reaction to BRUTUS’s report.10 Two days later we read that although ‘an early launching of FUSAG (still in the South-East of England) in a new landing operation is still held to be unlikely in view of the recent evidence … the presence which has recently been reported by several proven sources of two American armies (Ninth and Fourteenth) within the framework of this army group and the subordination to it of the English Fourth Army brought down from Scotland underline the significance which must be attached to FUSAG if the gaps made by its relinquishment of forces sent to Normandy have been made good.’11 The reference to ‘several proven sources’ would suggest that GARBO’s confirmatory letter, which was posted in Lisbon on 22nd July, had also reached Berlin.

In accordance with the new plan the wireless network of the reconstituted FUSAG opened in Kent, Sussex and the Eastern counties between 21st and 26th July, each formation being represented in its concentration area as shown in the chart on page 244. Simultaneously the CLH units embarked on their programme of assault training. Operational commitments prevented the Allied air forces from giving full effect to the bombing programme in support of FORTITUDE II to which they had agreed in June.12 By the time that the apparatus for physical deception was set in motion, the controlled agents had already acquainted the enemy with the main features of the new Order of Battle. During the last days of July, reports from BRUTUS and TATE disclosed the concentration of these forces in the East and South-East of England and these, in due course, found their way into the German Intelligence Summaries.

About this time there occurred an unexpected disaster, to which reference must now be made. A few days after his arrival in England General McNair decided to pay a short visit to France to observe the progress of operations. While there he was killed during an air attack. There was little chance of concealing his death from the enemy. It was therefore of the greatest importance that no time should be lost in providing the new army group with another commander. General McNair’s death was reported to the Germans on 26th July. ‘I have learnt that General McNair has been killed in Normandy where he had gone for a short visit to consult with General Montgomery and to inspect the coastal defences. This loss is considered here as very serious. It is thought that a successor will be appointed immediately to command the FUSAG operations.’13 Two days later the news was released to the press. As there seemed little chance of getting another general of McNair’s standing, but as something had to be done at once, it was decided to fall back once more on Simpson. At the same time the Supreme Commander felt that it would be worth asking General Marshall if he could help a second time. ‘As continuation of the threat to the Pas de Calais area depended to a considerable extent on the reputation of McNair, and particularly as his appointment as Commanding General First US Army Group has already been passed to the enemy, it would be desirable to assign another general officer from the United States with a reputation comparable to McNair’s to replace him as First US Army Group Commander. I appreciate that it may not be possible to make a suitable replacement available in time to be effective. Consequently, Simpson is being designated, for cover purposes, acting Commander of First United States Army Group, while at the same time retaining his present actual command of the Ninth US Army.’14 General Marshall very promptly rose to the occasion. General de Witt would be immediately available to take command of the First United States Army Group. General de Witt was at that time Director of the Army and Navy Staff College at Washington, an appointment which he had held for about two years. He had previously commanded 9th Service Command and Fourth Army at San Francisco, and while there had dealt with the Japanese problem in the Western United States after Pearl Harbor. It was therefore likely that the Germans would regard him as a suitable successor to McNair.

Meanwhile the first half of the story had reached its goal. ‘According to reliable reports Lieut.-General L. J. McNair, until recently Commander-in-Chief of the Land Forces in the United States, who has since been killed while on a visit to the front, was destined to succeed Lieut.-General Patton as Commander-in-Chief of the American First Army Group (England). It seems that Lieut.-General Patton has now assumed command of the Third American Army in Normandy. No information is available about the new commander of the American First Army Group in Great Britain.’15

General de Witt arrived on 6th August. So as not to put too much on to the controlled agents it was thought better on this occasion to allow the first announcement to appear in the press. On 9th August The Times printed the following short notice: ‘US Army Appointment–Lieut.-General John de Witt is now in the United Kingdom to fill the assignment previously held by General Lesley McNair. It was announced in The Times on 28th July that General McNair was killed in action in Normandy. Until recently he was in command of the US Army Ground Forces.’ Two days previously a similar announcement had been made in the United States, which the Germans had recorded in the following terms: ‘According to an official American announcement Lieut.-General John L. de Witt has been appointed successor to Lieut.-General L. J. McNair, killed in action. General de Witt was, until 1st September, 1943, Commander-in-Chief of the Fourth American Army in the United States and subsequently Commandant of the Academy for Higher Command in the Army and Navy (Army and Navy Staff College). He is said to be a particularly capable organiser. Lieut.-General de Witt has presumably assumed command of the First American Army Group (FUSAG) in Great Britain.’16

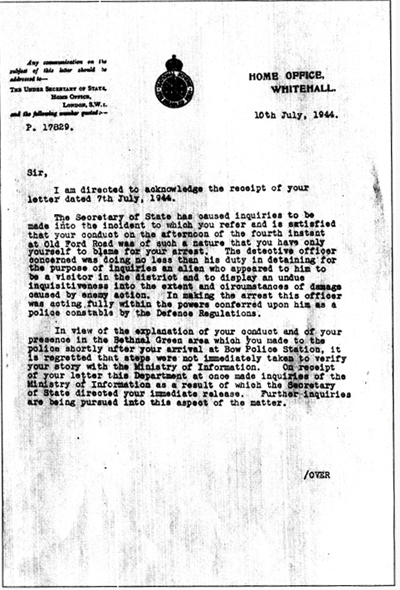

While these events were in progress, GARBO had been taking steps to extricate himself from the dangerous position in which his arrest had placed him. The rather grudging letter of apology which he succeeded in extracting from the Home Secretary he immediately sent to Madrid17 and on 23rd July received the following answer: ‘In my possession all your documents announced. Shocked by the story of your detention. We send cordial congratulations for your liberation. The security of yourself and of the Service requires a prolongation of the period of complete inactivity on your part, without any contact with collaborators…. For urgent and important military information Three should be able to take charge of communicating with us.’18 GARBO, however, was not one to remain idle for long. Before 20th July, as we have already seen, he had met 4 (3) and given a detailed report about the reorganisation of FUSAG. On 28th July he was able to tell Madrid that he had had a meeting with Three and Seven and had reorganised his entire network to suit the changed conditions.

Facsimile reproduction of forged letter purporting to have been written by the Home Secretary to GARBO and forwarded by him to Madrid, July 1944.

Before examining these new arrangements some reference must be made to an incident well calculated to restore the confidence of this agent after his recent unfortunate experiences. ‘With great happiness and satisfaction’, said Madrid on 29th July, ‘I am able to advise you today that the Fuehrer has conceded the Iron Cross to you for your extraordinary merits, a decoration which, without exception, is granted only to first-line combatants. For this reason we all send you our most sincere and cordial congratulations.’19 GARBO replied: ‘I cannot at this moment, when emotion overcomes me, express in words my gratitude for the decoration conceded by our Fuehrer, to whom humbly and with every respect I express my gratitude for the high distinction which he has bestowed on me, for which I feel myself unworthy as I have never done more than what I have considered to be the fulfilment of my duty. Furthermore I must state that this prize has been won not only by me but also by Carlos and the other comrades who, through their advice and directives, have made possible my work here and so the congratulations are mutual. My desire is to fight with greater ardour to be worthy of this medal which has only been conceded to those heroes, my companions in honour, who fight on the battle front.’20 Not unnaturally GARBO and his case officer were anxious to get possession of this interesting token of German esteem and on 12th August the agent wrote: ‘I want also today to amplify my message with regard to the Iron Cross which I have been conceded. From the time of knowing this, I have carried the series of reverses which I have suffered with greater resignation and, I can now say, with greater courage than previously. My fervent desire is to possess this and to hold it in my very hands. I know that this desire is difficult to fulfil as I cannot glorify myself with it when I have it. But for my personal satisfaction, I should certainly like to have it by me, even though it be hidden underground until I am able to wear it on my chest, the day when this plague which surrounds us is wiped off the face of the earth. Can you possibly send it camouflaged, via the courier?’21 It never came.

GARBO saw the wisdom of leaving the whole organisation in the hands of Three. As Three himself suggested, the Police might have set him free in order to keep a check on him and have him followed. It was therefore only prudent that for the time being at any rate he should sever all contact with his comrades. Agent Four had already dropped out as a result of his adventures at Hiltingbury Camp and had been in hiding in South Wales for nearly two months. GARBO described him as being in despair owing to his inactivity and afraid that sooner or later he would be found and tried as a deserter. Seven, too, was beginning to lose his nerve. He was worried by the detention both of 7 (5) and of GARBO within such a short space of time and he thought that the third arrest might be unlucky. He was thinking of returning to the Merchant Service. GARBO therefore asked him if he would at least help him to get Four out of the country and this he agreed to do. The proposal was to send him to Canada where Five could look after him. Of the rest, 7 (5) and 7 (6) had already been proved failures. GARBO therefore proposed to release them both. This, however, still left him with the best sub-agents, notably Donny, Dick and Dorick. Under the new scheme Three would be at the head, 7 (2) would be called in to act as a freelance, taking the place of Seven in that respect. The territory of 7 (4) would be enlarged to include Kent as well as Sussex, thus filling the gap caused by 7 (2)’s departure. 7 (7) and 3 (3) would continue as before, the former in the Eastern counties and the latter in Scotland.

During the three weeks that GARBO had been out of touch with his organisation the sub-agents had continued to make observations and compile reports. By now, of course, some of these were a little out of date. Nevertheless GARBO felt that it was worth sending them on if only to show that they had not been idle. From 7 (2) came full details of the departure of the First Canadian Army at the beginning of July, now indeed a matter of history but confirming the story of FORTITUDE and confirmed by identifications in the bridgehead. His later reports spoke of the arrival of the Fourth Army which had already been observed by BRUTUS. From agent Seven came another old report dating back nearly a month. It will be remembered that he had been sent by GARBO at that time to carry out investigations in Western Command. Here he had found all the newly arrived formations of the Fourteenth Army, again confirming and amplyfying what BRUTUS had already told the Germans. From 7 (7) came the news of the departing Third Army followed by the arrival of the American forces from Cheshire, the most notable feature of this change being the substitution of infantry for armour in the Eastern counties.22