IN THIS CHAPTER

Visualizing stock charts

Visualizing stock charts

Spotting simple patterns

Spotting simple patterns

Distinguishing between trends and trading ranges

Distinguishing between trends and trading ranges

Recognizing transitions from trading range to trend

Recognizing transitions from trading range to trend

Stock charts come in many flavors. Some prominent ones include candlestick charts, point‐and‐figure charts, and the ever‐popular bar charts, which are used throughout this book.

Bar charts are easy to create, interpret, and track over time. Furthermore, charting tools and analysis techniques for bar charts apply to stocks, bonds, exchange‐traded funds (ETFs), options, indexes, and futures, and they’re applicable across any time frame in which you may want to trade. In addition, most chart patterns work for both long trades (buy first, sell later) and short trades (sell first, buy later).

This chapter shows you how to draw price charts for a single stock, for an index such as the S&P 500 or NASDAQ Composite, or for an ETF, and how to recognize simple single‐day trading patterns. In addition, you find out how to identify trends and trading ranges and how to look for key transition points that often lead to good trading opportunities. Charting is a visual methodology, so you’ll find many example charts used throughout this chapter. Examine them carefully. You want to quickly identify the patterns we describe here when evaluating charts in your own trading.

Creating a Price Chart

In the decades before computers, traders followed and carefully documented stock prices to create their charts by hand. Today, however, powerful software has eliminated that need. In the modern, tech‐driven world, a seemingly endless supply of charting tools and analysis platforms is available. For instance, you’ll find a wide array of online charting services that can be quickly and easily accessed from any Internet‐enabled device. Many of those tools can even be securely connected to your brokerage, further streamlining your trading practices. Downloadable software is also available. These resources are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

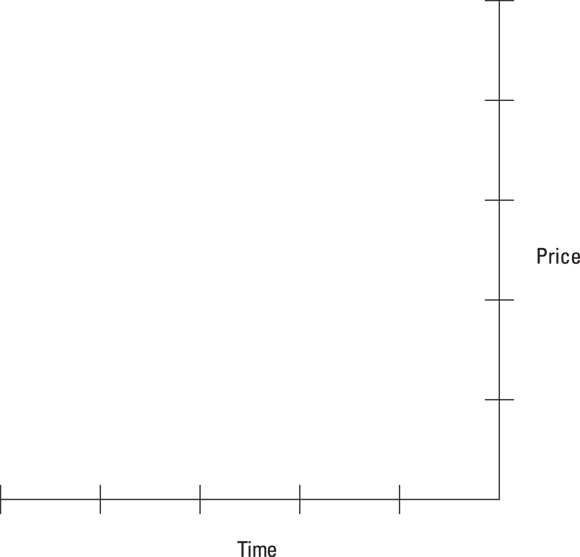

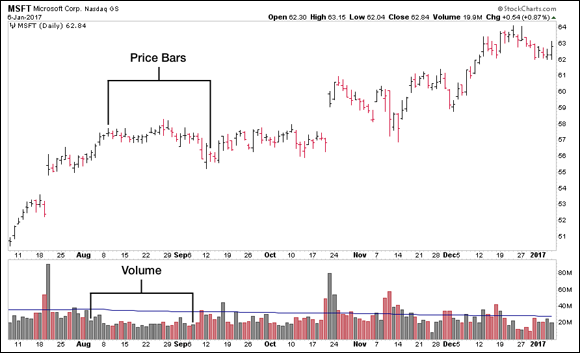

Even though you no longer need to create your own charts by hand, it’s still valuable to understand the basic elements of a stock chart. The basic characteristics of a chart of stock prices are the same as those of the common charts with which you’re probably familiar. Stock charts typically are made up of two axes; the horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis represents price. One unusual feature of a stock chart is that its vertical axis, the price axis, usually is shown on the right, as in Figure 9‐1. The most current prices are shown on the far right‐hand side of the chart, as are the newest trading signals. You always trade while those signals are on the right edge of a chart, so displaying the price axis closest to the most crucial part of the chart makes sense.

Looking at a single price bar

Regardless of whether your chart is an intraday chart (showing fluctuations throughout a single trading day) or a chart of daily or weekly prices, the format of the price bar is the same. Each bar represents the results for a single trading period. On a chart that provides daily information, for example, each bar represents the results for a single trading day. Alternatively, on a chart that provides intraday data, each bar could represent the results for as little as a single minute of trading activity.

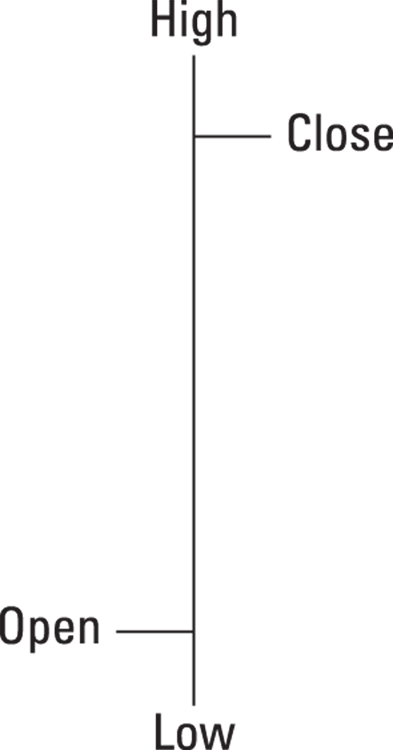

Most stock‐price bar charts show four crucial prices on each bar:

- Open: The price recorded for the first trade of the period

- High: The highest price trade at any point in the trading period

- Low: The lowest price trade at any point in the trading period

- Close: The price recorded for the last trade of the period

By convention, a daily bar chart shows trades for the standard New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) trading day — from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET — but some charting packages include optional after‐hours results (prices from trades that occur after the market closes) as part of each daily bar. Likewise, some charting packages omit the opening prices on intraday charts. The opening price on an intraday chart (almost) always is the same as the closing price for the previous bar, so omitting it is of little consequence. However, omitting the opening price on daily, weekly, and monthly charts diminishes a chart’s usefulness, so avoid charts that don’t provide all four prices.

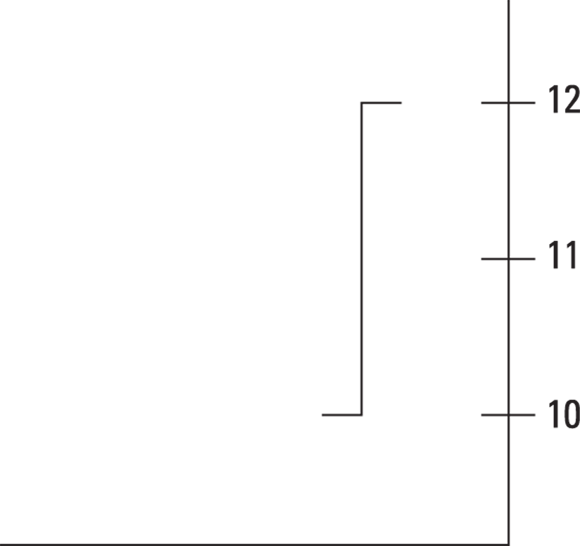

Figure 9‐2 shows a single OHLC price bar. The name OHLC price bar is derived from the four prices the bar represents: the open, the high, the low, and the close. The full range of prices traded throughout the period is shown by the vertical bar, with the bottom point representing the lowest price and the top point representing the highest price. The opening price is shown as a small line on the left‐hand side of the bar, and the closing price is shown by a similar line on the right‐hand side of the bar.

This identical format is used for all time periods. For example, an intraday chart may use 1‐minute bars, where each bar spans all the prices for your stock that occur during trades over a single minute. Common time frames for stock price charts are

- 1‐minute bars: Each bar represents 1 minute of trading.

- 5‐minute bars: Each bar represents 5 minutes of trading.

- 10‐minute bars: Each bar represents 10 minutes of trading.

- 15‐minute bars: Each bar represents 15 minutes of trading.

- 60‐minute bars: Each bar represents 60 minutes of trading.

- Daily bars: Each bar represents one full day of trading.

- Weekly bars: Each bar represents one full week of trading.

- Monthly bars: Each bar represents one full month of trading.

In our own trading, we typically monitor weekly charts, daily charts, and one or two intraday charts, generally 60‐minute and 1‐minute bars for stocks and ETFs. We cover our chart selection and methodology more fully in Chapter 13.

Measuring volume

In addition to prices, stock charts often show the volume (the number of shares traded) during the given time period represented by each bar. On a daily chart, trading volume shows the total number of shares traded throughout the day. By convention, the volume is shown as a separate bar graph and usually is shown directly underneath the price chart. Figure 9‐3 shows an example.

Volume is used as a confirming indicator. In other words, if a price bar shows bullish activity (which is discussed later in the section “Identifying Simple Single‐Day Patterns”), that bullishness is confirmed by a higher‐than‐average trading volume. However, that bullish indication may diminish if trading volume is lower than average.

Volume is used as a confirming indicator. In other words, if a price bar shows bullish activity (which is discussed later in the section “Identifying Simple Single‐Day Patterns”), that bullishness is confirmed by a higher‐than‐average trading volume. However, that bullish indication may diminish if trading volume is lower than average.

Volume also is used to gauge institutional participation in a stock. Significant trading volume often signals that large institutional investors — mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, and others — are placing orders to buy or sell a stock. When prices rise and volume is strong, you usually can infer that institutions are accumulating positions in the stock. The reverse is also true. When prices fall and trading volume is high, large institutions may be liquidating positions, which is considered a bearish development.

Because volume effectively signals demand, low‐volume price changes are less meaningful, from a technical perspective, than high‐volume changes. That’s why technicians say, “Volume confirms price.” Ask yourself this: Would you want to buy a stock that 10,000 traders are bullish about, or would you prefer a stock that 10 million traders are bullish about?

StockCharts.com makes it easy to start using OHLC bar charts like the one shown in Figure 9‐3. Click the tab for Free Charts at the top of the site, and then look for the SharpCharts box in the upper‐left portion of the page. Enter the symbol you want to view in the box labeled Create a SharpChart, and then click Go. You’ll be directed to a SharpChart of your symbol, and you can then customize its attributes using the interface below the chart. In the Chart Attributes panel, change the Type from Candlesticks to OHLC Bars (either thin or thick, whichever is your preference) and then click Update. You can also change the Volume from Overlay to Separate to match the look of the chart in Figure 9‐3. We use this same configuration for all the charts in this chapter.

StockCharts.com makes it easy to start using OHLC bar charts like the one shown in Figure 9‐3. Click the tab for Free Charts at the top of the site, and then look for the SharpCharts box in the upper‐left portion of the page. Enter the symbol you want to view in the box labeled Create a SharpChart, and then click Go. You’ll be directed to a SharpChart of your symbol, and you can then customize its attributes using the interface below the chart. In the Chart Attributes panel, change the Type from Candlesticks to OHLC Bars (either thin or thick, whichever is your preference) and then click Update. You can also change the Volume from Overlay to Separate to match the look of the chart in Figure 9‐3. We use this same configuration for all the charts in this chapter.

Coloring charts

Displaying price and volume bars in color is common on financial charts. Contrasting colors help distinguish up days from down days. StockCharts.com, for example, defaults to black for up days and red for down, but, like most charting services, you can customize these colors to your liking.

Identifying Simple Single‐Day Patterns

The goal of chart reading is to determine whether buyers or sellers are in control of the price. In a bull market, stockowners may be willing to sell, but only if they can coax higher prices from buyers. That cycle drives prices up. In a bear market, buyers are able to negotiate a better price when sellers are more eager to sell than buyers are to buy. That cycle drives prices down.

You’re trying to infer the market’s underlying psychology by looking at the history of price movements. You can fairly infer that as prices rise, buyers are more interested in buying than sellers are in selling. In a rising market, buyers must continue bidding prices higher to convince sellers to part with their shares. Rising prices attract additional buyers, who must continue to bid prices higher to convince even more reluctant sellers to part with their shares. Understanding the psychology behind these market movements is the first step to profiting from them.

You’re trying to infer the market’s underlying psychology by looking at the history of price movements. You can fairly infer that as prices rise, buyers are more interested in buying than sellers are in selling. In a rising market, buyers must continue bidding prices higher to convince sellers to part with their shares. Rising prices attract additional buyers, who must continue to bid prices higher to convince even more reluctant sellers to part with their shares. Understanding the psychology behind these market movements is the first step to profiting from them.

Single‐bar patterns

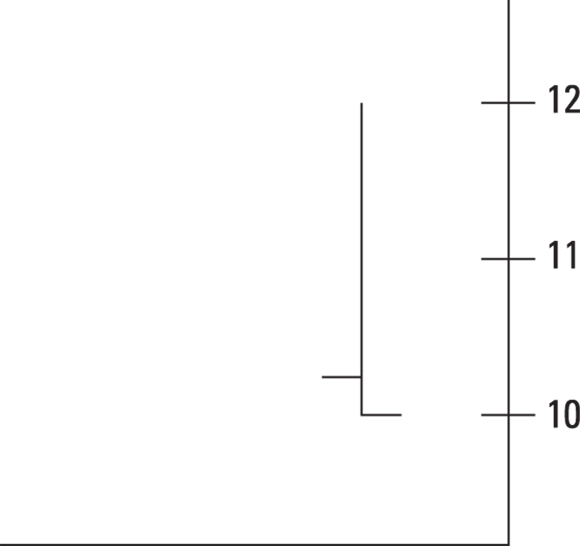

The most bullish thing that a market can do is go higher. Although technicians typically view each bar within the context of its neighboring bars, each individual bar has something to tell the careful observer. Figure 9‐4, for example, shows a bullish single‐bar pattern.

In the example in the figure, buyers bid prices higher throughout the day. The opening price of $10 also is the lowest trade for the day. The daily range shown on the bar is $2, and the stock closed at $12, the high for the day.

If you were to keep score, the bulls gained ground and clearly are ahead for the day. Bears holding short positions were hurt where it hurts the most — in their pocketbooks. A trader takes a short position by borrowing shares of stock and selling them in the hope of making money if the stock price falls. Short trades lose money if the stock’s price rises. The mechanics of selling short are described in Chapter 15. The example in Figure 9‐4 shows the stock opening at the absolute low and closing at its absolute high, but the pattern nevertheless is just as bullish when the stock opens near its low and then closes near its high.

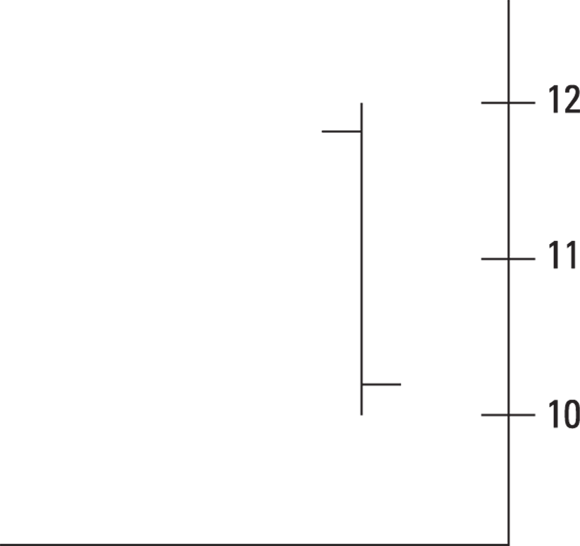

Figure 9‐5 shows a bearish single‐bar pattern. The stock opened at $11.75; traded to $12, the high for the day; fell to $10, the daily low; and then closed at $10.25. The stock doesn’t have to close at its absolute low for the day for it to be bearish. Closing near the low is close enough.

These single‐day patterns are helpful to the trader who’s trying to understand the market’s underpinnings. Whether these patterns present a trading opportunity depends on the stock’s recent history and whether its trading volume confirms the pattern (see the earlier section “Measuring volume”). For example, if a bullish bar like the one in Figure 9‐4 shows at a key technical level (perhaps breaking through a well‐tested resistance point) and is confirmed by high volume, its bullishness sends a very meaningful signal that prices are likely to continue rising. We give you several examples later in this chapter, in the section “Searching for Transitions,” where a bullish single‐bar pattern triggers a buy signal.

Reversal patterns

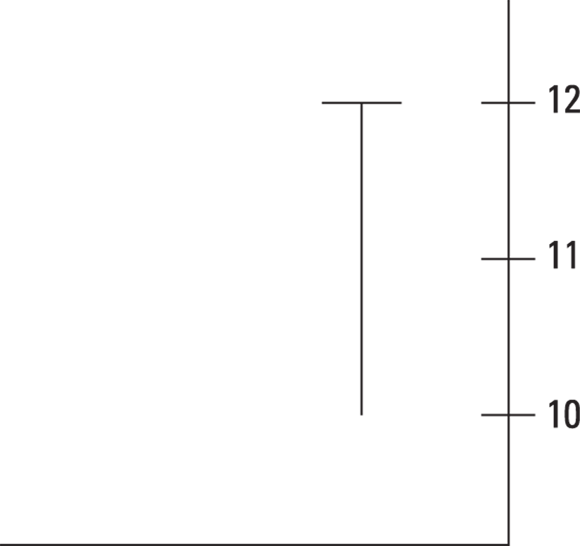

A reversal bar is another single‐bar pattern that shows a stock opening and closing at the same end of its trading range. Figure 9‐6 shows a bullish single‐bar reversal where the stock opens at the high, trades lower through part of the day, but by the close regains all its losses and closes at its highest intraday price.

During the early part of the trading sessions depicted in the bullish reversal pattern, buyers were willing to buy only if sellers lowered their offering (asking) prices. By the end of the day, the tide had turned and roles were reversed, with sellers willing to sell but only at higher prices. This situation is another win for the bulls because they were able to stop the price slide and recover all the intraday losses, finishing the day back near the stock’s opening price.

Figure 9‐7 shows a bearish reversal pattern. In this case, the stock opens at $10.25, rallies during the day to $12, but closes at the $10 low.

Reversal patterns often represent a powerful single‐bar trading pattern. Whenever a bullish reversal bar is preceded by several periods of falling prices, for example, its pattern can represent a promising buying opportunity. On the other hand, a bearish reversal bar preceded by a rising trend may be a signal to close a long trade or initiate a short position. Selling short is described in Chapter 15.

Reversal patterns often represent a powerful single‐bar trading pattern. Whenever a bullish reversal bar is preceded by several periods of falling prices, for example, its pattern can represent a promising buying opportunity. On the other hand, a bearish reversal bar preceded by a rising trend may be a signal to close a long trade or initiate a short position. Selling short is described in Chapter 15.

Not all price bars, however, present specific trading opportunities. Some bars are neutral by themselves but add to a stock’s history when viewed in context. It’s important to learn and recognize important single‐bar patterns and also crucial to be able to distinguish the neutral price bars from more significant ones. Through charts, you can use a stock’s visual historical record to develop your trading plan, as you see in the following sections.

Recognizing Trends and Trading Ranges

Technical analysis helps you identify trends, allowing you to determine when one begins and ends. Our style of trading, position trading, looks for the persistent trend, one that lasts for at least several weeks to several months, possibly even longer. Day traders and swing traders who buy and sell in the shortest of terms also look for trends to trade. Those trends simply play out over a shorter period, whether it’s a few minutes, a few hours, or a couple of days. In fact, the primary distinction between a day trader, a swing trader, and a position trader is the length of the trend that each is hoping to identify. Swing trading and day trading are discussed in Chapters 17 and 18, respectively. If you’re really interested, check out Swing Trading For Dummies, by Omar Bassal, CFA, and Day Trading For Dummies, by Ann C. Logue, MBA (both published by Wiley).

Following trends is an effective trading strategy, especially for new traders. To follow trends successfully, you first need to identify and distinguish between stocks, funds, and market indexes exhibiting trends and their counterparts, trading within specific price ranges. Stocks are either trending up or down or bouncing within a range. Your job is to determine which phase it’s currently in and recognize when it begins to transition from one phase to another.

Following trends is an effective trading strategy, especially for new traders. To follow trends successfully, you first need to identify and distinguish between stocks, funds, and market indexes exhibiting trends and their counterparts, trading within specific price ranges. Stocks are either trending up or down or bouncing within a range. Your job is to determine which phase it’s currently in and recognize when it begins to transition from one phase to another.

Discerning a trading range

Ultimately, a stock, fund, or index can do only one of three things: rise in an uptrend, fall in a downtrend, or move sideways as prices bounce up and down within a confined price range. A stock that fits the latter is said to be range bound or stuck in a trading range, never trading higher than the high nor lower than the low during a specific time frame. You also hear range‐bound stocks described as consolidating or building a base. Although some subtle distinctions may exist among these terms, we nevertheless use them interchangeably.

In general, we’re not interested in trading range‐bound stocks. Trading ranges can persist for long periods of time. Some may even last for years. For a position trader, having money in a range‐bound stock represents wasted opportunity. You won’t lose money, but you won’t make any either. Although they may not be great trading opportunities, range‐bound stocks do make fantastic watch list candidates. Traders are interested in identifying range‐bound stocks because they have the potential to begin trending in either direction, up or down. We patiently watch these stocks for a signal indicating the trading range may end and a trend may begin, whether it’s to the upside or the downside. Stocks that break out of a long‐lasting trading range often begin trends that can be traded profitably.

Trading ranges are easy to spot after the fact, but anticipating when a stock is about to enter or exit a trading range is nearly impossible. For this and other reasons, range‐bound stocks are difficult to trade, especially for new traders. Some short‐term traders are able to trade range‐bound stocks successfully, so it isn’t impossible, but we encourage you first to become a proficient trend trader before attempting to trade stocks stuck in trading ranges. Tools you can use in trading‐range situations are described in Chapter 11. In Chapter 10, we discuss what to do if a stock you own stops trending and becomes range bound.

Trading ranges are easy to spot after the fact, but anticipating when a stock is about to enter or exit a trading range is nearly impossible. For this and other reasons, range‐bound stocks are difficult to trade, especially for new traders. Some short‐term traders are able to trade range‐bound stocks successfully, so it isn’t impossible, but we encourage you first to become a proficient trend trader before attempting to trade stocks stuck in trading ranges. Tools you can use in trading‐range situations are described in Chapter 11. In Chapter 10, we discuss what to do if a stock you own stops trending and becomes range bound.

Identifying a trading range is best done visually. Figure 9‐8 shows a chart of Wynn Resorts Ltd. (WYNN) moving sideways in a range‐bound pattern after an initial run up.

Wynn Resorts spent more than nine months trading between $82.00 and $109.00. Notice how the price moves up and down but always between those levels, never making much progress one way or the other. The closing price for the final trading day on this chart is $92.43, right in the middle of the stock’s range. As we discuss more later in this chapter, the upper and lower bounds that define Wynn’s trading range represent support and resistance levels.

Spotting a trend

Now contrast the Wynn Resorts chart in Figure 9‐8 with the chart of Micron Technology, Inc. (MU), in Figure 9‐9. MU is clearly quite different from the range‐bound stock. Notice the steady stair‐step march upward as the stock rises higher and higher.

Even in a strong upward trend, stocks rarely go straight up. You often see some reversals and mini‐consolidations throughout the trend that cause the stair‐stepped look.

That stair‐stepped upward march is an identifying characteristic of an uptrend. Although defining it quantitatively is possible, spotting an uptrend on a chart is easy, and that’s the way it often is done. As long as a stock price continues to trade at higher highs and its new lows don’t fall below previous lows, the uptrend remains intact. Chapter 10 discusses trends and these stair‐step patterns in more detail.

That stair‐stepped upward march is an identifying characteristic of an uptrend. Although defining it quantitatively is possible, spotting an uptrend on a chart is easy, and that’s the way it often is done. As long as a stock price continues to trade at higher highs and its new lows don’t fall below previous lows, the uptrend remains intact. Chapter 10 discusses trends and these stair‐step patterns in more detail.

Stocks can also downtrend; a series of lower highs and lower lows is as much of a trend as its upward‐bound counterpart. See Figure 9‐10, a chart showing Valeant Pharmaceuticals (VRX) in a downtrend.

Paying attention to time frame

The time frame of your chart determines your trading perspective.

You may notice that the price history of a range‐bound stock is made up of many small trends. If you look at an intraday chart of Wynn Resorts stock (WYNN) that spanned the 25 days of trading from May 19, 2016, through June 23, 2016, WYNN appears to be in a strong uptrend. Then again later in the year, between November 15 and November 30, 2016, WYNN was on a tear in a seemingly unstoppable uptrend.

Yet, when you step back and observe a broader historical record of WYNN’s trading pattern on the daily and weekly charts, you can easily see that these multiday trends are actually confined within the prevailing trading range during the year.

Although short‐term swing traders and day traders make a living basing their trading on these mini‐ and/or microtrends, doing so isn’t our cup of tea. Consistently trading range‐bound stocks profitably by focusing on much shorter time frames is very difficult to do, and even more difficult to do consistently.

Although short‐term swing traders and day traders make a living basing their trading on these mini‐ and/or microtrends, doing so isn’t our cup of tea. Consistently trading range‐bound stocks profitably by focusing on much shorter time frames is very difficult to do, and even more difficult to do consistently.

Searching for Transitions

A stock can transition from a downtrend to an uptrend in a wide variety of fashions. It can, for example, fall precipitously, turn on a dime, and begin heading higher. In an alternate scenario, a stock can fall, bounce around in a trading range for a while, and begin a new trend — up or down — as it breaks out of the trading range.

It’s enticing when you see a stock turn on a dime from down trending to up trending, and this scenario can sometimes present profitable trading opportunities. However, this sort of V‐shaped chart pattern is also difficult to identify and even more difficult to base a trade on. Still, additional tools of technical analysis designed to unearth these transitions are explained in Chapters 10 and 11.

In our trading, we’re looking for promising opportunities based on proven patterns, seeking consistent, repeatable results instead of occasional jackpots. Rather than trying to score big on sharp transitions, we recommend searching for stocks that are developing strong new trends after a well‐defined period of range‐bound trading, preferably lasting at least six to eight weeks or more. This is simply a more reliable strategy with a higher probability of success.

Support and resistance: The keys to trend transitions

The transition from sideways, range‐bound trading to defined up or down trending is relatively easy to identify visually. It’s also the easiest to trade profitably. To find the transition, you must be familiar with the concept of support and resistance.

Support is always the lower trading‐range boundary. Think of support as the floor. Resistance is always the upper trading‐range boundary. Think of resistance as the ceiling. Once a resistance level has been broken, it often turns into a future support level. On the flip side, once a support level has been broken, it’s likely to turn into a future resistance level.

Support is always the lower trading‐range boundary. Think of support as the floor. Resistance is always the upper trading‐range boundary. Think of resistance as the ceiling. Once a resistance level has been broken, it often turns into a future support level. On the flip side, once a support level has been broken, it’s likely to turn into a future resistance level.

You’ll see support and resistance used in many contexts. For example, these levels are used to identify a trading range, as discussed in this section. They’re also used to help identify when a trend has reached its end, as we discuss in Chapter 10.

For an example of how support and resistance levels are shown on a chart, refer to Figure 9‐8, the chart showing WYNN stuck in a trading range. The support line shown on this chart is at roughly $86.00; the resistance line is shown near $104.00.

When technicians talk about support, they mean the price where buyers are willing to purchase enough stock to stop the price from falling. Framed another way, when sellers recognize enough buying interest at the support price, they grow less willing to sell and will do so only if they can coax buyers to raise their bids. Buyers are now more eager to buy than the sellers are to sell; thus, the buyers are willing to bid a little more to complete the transaction. The result: Prices end their descent and begin heading higher.

The reverse is true as the stock’s price approaches the resistance level. Buyers begin losing interest as the stock reaches elevated prices. Eager sellers must lower their offer (asking) price to complete the transaction, which causes prices to stop rising and begin falling.

Support levels and resistance levels often are determined visually by looking back at a stock’s price history. Knowing the specific price where levels of support and resistance need to be drawn is difficult, and traders may differ on exactly where to draw these lines. Some choose the extreme, plotting intraday highs and lows of a trading range during a specific time frame to establish those levels. Others prefer to use closing prices on a daily or weekly bar chart to define the upper and lower boundaries within the trading range. If you’re analyzing an intraday chart, use the last trade price on each bar when drawing the support and resistance levels. The choice is ultimately yours, but in our opinion, closing prices (or last prices) have more significance and better represent the consensus of traders and investors. The majority of the market’s trading volume occurs in the first and last hours of the trading day; therefore, opening and closing prices generally paint a truer picture of how the majority of buyers and sellers are pricing the stock.

Support levels and resistance levels often are determined visually by looking back at a stock’s price history. Knowing the specific price where levels of support and resistance need to be drawn is difficult, and traders may differ on exactly where to draw these lines. Some choose the extreme, plotting intraday highs and lows of a trading range during a specific time frame to establish those levels. Others prefer to use closing prices on a daily or weekly bar chart to define the upper and lower boundaries within the trading range. If you’re analyzing an intraday chart, use the last trade price on each bar when drawing the support and resistance levels. The choice is ultimately yours, but in our opinion, closing prices (or last prices) have more significance and better represent the consensus of traders and investors. The majority of the market’s trading volume occurs in the first and last hours of the trading day; therefore, opening and closing prices generally paint a truer picture of how the majority of buyers and sellers are pricing the stock.

Technical analysis should never be taken as an exact science. As such, it’s often better to think of support and resistance as areas rather than specific price points down to the penny. Many technicians actually define support and resistance zones on their charts as narrow ranges rather than single lines. It’s important to remember what support and resistance represent: key technical levels where buying and selling pressures have caused interesting things to happen in the past. When current prices approach those levels again, smart traders watch closely for new signals to appear once more.

Technical analysis should never be taken as an exact science. As such, it’s often better to think of support and resistance as areas rather than specific price points down to the penny. Many technicians actually define support and resistance zones on their charts as narrow ranges rather than single lines. It’s important to remember what support and resistance represent: key technical levels where buying and selling pressures have caused interesting things to happen in the past. When current prices approach those levels again, smart traders watch closely for new signals to appear once more.

Finding a breakout

A stock remains stuck in its trading range as long as it bounces between zones of support and resistance. Short‐term traders may be interested in these back‐and‐forth movements, but as a position trader, you’re looking for a more substantial trend. You must therefore wait for something to change the status quo and cause the stock to break out of its trading range.

A breakout signals the transition of a stock trading within a range to a new uptrend or downtrend. When breaking out to the upside, you want to see the stock trade above resistance at the top of its trading range by a significant amount, certainly more than 5 or 10 cents. More important, you want the resistance zone to be broken on substantially higher volume than the average. Ideally, volume needs to be at least 50 percent higher than average. The greater the volume of the breakout, the stronger the signal.

A breakout signals the transition of a stock trading within a range to a new uptrend or downtrend. When breaking out to the upside, you want to see the stock trade above resistance at the top of its trading range by a significant amount, certainly more than 5 or 10 cents. More important, you want the resistance zone to be broken on substantially higher volume than the average. Ideally, volume needs to be at least 50 percent higher than average. The greater the volume of the breakout, the stronger the signal.

Figure 9‐11 shows a chart of Northern Trust Corp. (NTRS) and is a textbook example of a stock breaking out of a trading range. NTRS had been trading within a range from early 2016 to the beginning of November. We drew the support line at roughly $62.00 and the resistance line near $73.00. The support and resistance levels were tested several times in 2016.

On November 9, 2016, NTRS opened above its previous close, traded through the zone of resistance, and closed near its high of the day at $76.79. Trading volume was almost 2.5 million shares, nearly double the average daily volume of 1.3 million shares. As the breakout continued, volume kept increasing, with as many as 3.6 million shares traded on the fourth day of the move.

Waiting patiently for winning patterns

We can hear the gears grinding from here. Yes, it’s a nice trade . . . but you’re probably saying to yourself, “Couldn’t I have bought NTRS for about $61.00 several times back in June or July? Why wait until the breakout drives my entry price up?”

The answer: Finding a good trading signal is important; avoiding bad trading signals is more important. A stock trader can endure two losses: capital and opportunity. If you fall for bad trading signals, let your losses build, and fail to protect your capital, there can be no opportunity. Without cash to invest, you have no options. However, if your first objective is to protect your capital, you’ll always have another opportunity.

The answer: Finding a good trading signal is important; avoiding bad trading signals is more important. A stock trader can endure two losses: capital and opportunity. If you fall for bad trading signals, let your losses build, and fail to protect your capital, there can be no opportunity. Without cash to invest, you have no options. However, if your first objective is to protect your capital, you’ll always have another opportunity.

Foretelling the future is hard. Of course hindsight tells you that buying NTRS at $61.00 would’ve earned you more money than buying it above $75. But when the price was $61.00, how could you know that NTRS wouldn’t stay in its trading range for many more months or years? Or how could you tell that NTRS wasn’t going to break out of its trading range to the downside and start trending lower?

It happens. In fact, if the stock had traded below its zone of support, technical analysis would’ve suggested a potential opportunity to sell NTRS short.

Fine‐tuning your trading‐range breakout strategy

No two trading ranges are created equal, and it’s important to respect the differences between stronger trading‐range breakouts and weaker ones. To help improve your breakout trading strategies, consider the following:

- Breakouts from long trading ranges tend to produce more profitable buying and selling than breakouts from shorter trading ranges.

- Breakouts from tight trading ranges, where price fluctuations are confined to a relatively narrow price range, usually result in better trades than breakouts from wider trading ranges.

- Wait for a short while — at least one day, possibly two or three — to confirm the trading range breakout. Waiting to see whether the stock falls back into its trading range before you take a position can save you from suffering a loss in a false breakout. It isn’t uncommon to see a wave of selling immediately after a breakout. The stock’s reaction to that selling is often just as important as the breakout itself.

Consistently catching the lowest price is nearly impossible, regardless of whether you use technical analysis, fundamental analysis, or your magic 8‐ball. Technical analysis can help you find transitions, but it can’t predict the future. No financial analysis tool can. As a technician, you rarely buy stocks at their lowest prices, and you rarely exit your positions at the highest prices. Fortunately, you don’t need to perfectly time your entry and exit points to trade profitably.

Consistently catching the lowest price is nearly impossible, regardless of whether you use technical analysis, fundamental analysis, or your magic 8‐ball. Technical analysis can help you find transitions, but it can’t predict the future. No financial analysis tool can. As a technician, you rarely buy stocks at their lowest prices, and you rarely exit your positions at the highest prices. Fortunately, you don’t need to perfectly time your entry and exit points to trade profitably.

If you wait for a solid and reliable trading signal, you can ride the middle part of the trend for a large portion of the move. Try not to be greedy. The middle part of the trend is a very profitable place to trade.

If you wait for a solid and reliable trading signal, you can ride the middle part of the trend for a large portion of the move. Try not to be greedy. The middle part of the trend is a very profitable place to trade.

Trading stocks isn’t about hitting home runs every time. Instead, the key is to design and commit to a consistent investment system based on proven methods that will allow you to repeatedly achieve positive returns. Take a long‐term view and keep the bigger picture in mind without over‐focusing on one specific trade.

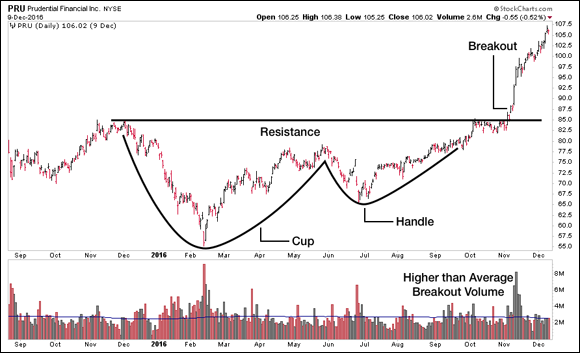

Sipping from a cup and handle

Another widely followed transitional formation is called a cup and handle. In a cup and handle formation, a stock’s price levels form a rounded curving bottom that looks a bit like a cup or a saucer, which often is followed by a modest shakeout formation that, if you use your imagination, looks a bit like the handle on a coffee cup.

Figure 9‐12 shows a chart of Prudential Financial (PRU) that illustrates the cup and handle formation.

The entry strategy for this pattern is similar to that used for the trading range breakout. The trigger occurs when the stock price breaks above the handle on high volume. In the Prudential example, it occurs in the final trading days of September. The stock makes a strong move above resistance, takes another brief pause, and then continues upwards once more through the end of the year.

The cup and handle is a reliable trading pattern, but that doesn’t mean the pattern never fails. Nothing is ever guaranteed in the stock market, and you need an exit strategy in case the pattern you’re trading fails, just like every other trade. Exit strategies are discussed in Chapter 12.

The cup and handle is a reliable trading pattern, but that doesn’t mean the pattern never fails. Nothing is ever guaranteed in the stock market, and you need an exit strategy in case the pattern you’re trading fails, just like every other trade. Exit strategies are discussed in Chapter 12.

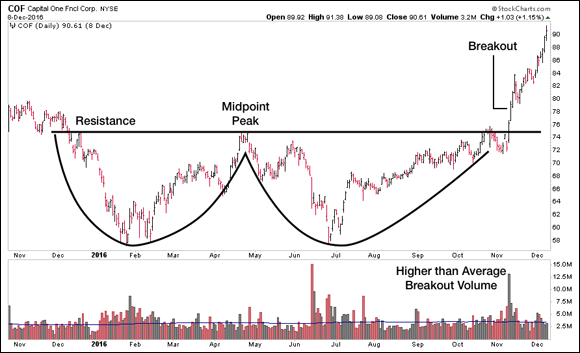

Deciding what to do with a double bottom

Another transition pattern that often leads to profitable trading opportunities is the double bottom. Visually, a double bottom looks like a W on the chart, so it’s very easy to recognize. However, a double bottom doesn’t need to form a perfect W to be valid. In fact, we actually prefer the right‐hand trough to be a little lower than the left‐hand trough. When a minor new low forms, it tends to shake out the stock’s weakest owners, thus making it much easier for bulls to drive the price higher when the stock begins to rally.

Figure 9‐13 shows a well‐formed double bottom on the chart of Capital One Financial (COF). The left‐hand trough occurred in the early months of 2016; the right‐hand trough formed shortly after in the summer months of that year.

The entry criteria for this pattern are again similar to that of the trading‐range breakout. In this case, the trigger point occurs when the stock breaks above the midpoint peak between the two troughs. This peak is sometimes called the pivot point. Ideally, higher‐than‐average volume confirms the trigger.

The trigger price on the chart is right around $75.00, which corresponds to the price levels the stock traded at during late April. The stock does stumble across its resistance level in a false breakout in late October, but after a short pullback it rockets up across the $75.00 range on November 9. Notice that the stock trades over 13 million shares that day, well above its average daily trading volume of around 3.5 million.

An alternative double‐bottom strategy

One scenario where aggressive traders may want to anticipate the formation of a double‐bottom pattern is when the W is particularly deep and the pivot is many points away from the trough. When that happens, taking a position as the stock is forming the right‐hand trough sometimes makes sense.

If the price holds near or just below the left‐hand trough and volume confirms the reversal, then aggressive traders can enter a position. You may also want to enter a position if signals from other single‐day patterns confirm the reversal. The risk is relatively small, and the potential reward is relatively large. If the stock falls below the lowest low, you’ll know your trade has failed and you must exit. Otherwise, hold the position until the stock tests the pivot point (see the preceding section).

Using the COF chart in Figure 9‐13 to illustrate this strategy, the buy trigger occurred on July 6 after COF fell, rallied upwards, pulled back again, but was then stopped at a higher low. The stock climbed from there for a nice gain into mid‐July. In this case, your entry point could be the next trading day, July 7, and your stop would be below $58.98, the low for the July 6 reversal bar.

Looking at other patterns

We believe that the reversal patterns described in the preceding few sections are the most reliable. However, many other common reversal patterns are published in technical analysis books and online educational resources, such as StockCharts.com’s ChartSchool.

Inexperienced traders always want to find the Holy Grail, that pattern or indicator that enables them to profitably trade the turn‐on‐a‐dime V‐bottom pattern. In truth, however, V‐bottoms don’t happen all that often. And when they do, many reasons express why it’s probably not the best trading opportunity available to you. If you talk shop with other traders, you’re certain to hear them discuss many esoteric patterns. We know them, but we rarely trade them. The simple techniques we’ve shown you in this chapter enable you to trade profitably. It doesn’t hurt to learn other patterns, even if only to satisfy your curiosity, but be careful. There’s no need to look for the obscure when the simple does the job just as well.

Inexperienced traders always want to find the Holy Grail, that pattern or indicator that enables them to profitably trade the turn‐on‐a‐dime V‐bottom pattern. In truth, however, V‐bottoms don’t happen all that often. And when they do, many reasons express why it’s probably not the best trading opportunity available to you. If you talk shop with other traders, you’re certain to hear them discuss many esoteric patterns. We know them, but we rarely trade them. The simple techniques we’ve shown you in this chapter enable you to trade profitably. It doesn’t hurt to learn other patterns, even if only to satisfy your curiosity, but be careful. There’s no need to look for the obscure when the simple does the job just as well.

Visualizing stock charts

Visualizing stock charts Spotting simple patterns

Spotting simple patterns Distinguishing between trends and trading ranges

Distinguishing between trends and trading ranges Recognizing transitions from trading range to trend

Recognizing transitions from trading range to trend

Volume is used as a confirming indicator. In other words, if a price bar shows bullish activity (which is discussed later in the section “

Volume is used as a confirming indicator. In other words, if a price bar shows bullish activity (which is discussed later in the section “ StockCharts.com makes it easy to start using OHLC bar charts like the one shown in

StockCharts.com makes it easy to start using OHLC bar charts like the one shown in

Although short‐term swing traders and day traders make a living basing their trading on these mini‐ and/or microtrends, doing so isn’t our cup of tea. Consistently trading range‐bound stocks profitably by focusing on much shorter time frames is very difficult to do, and even more difficult to do consistently.

Although short‐term swing traders and day traders make a living basing their trading on these mini‐ and/or microtrends, doing so isn’t our cup of tea. Consistently trading range‐bound stocks profitably by focusing on much shorter time frames is very difficult to do, and even more difficult to do consistently.