Chapter 17

The Basics of Swing Trading

IN THIS CHAPTER

Picking the right stocks for swing trading

Picking the right stocks for swing trading

Using specific strategies in swing trading

Using specific strategies in swing trading

Substituting options for stocks

Substituting options for stocks

Identifying tax issues and account restrictions for swing traders

Identifying tax issues and account restrictions for swing traders

Swing trading is a trading strategy that tries to take advantage of short‐term opportunities in the market. It occupies the middle ground between position trading and day trading. Swing traders use trend‐following and countertrend strategies to participate in trading‐range and trending stocks. This turbo‐charged trading style requires an exceptional understanding of the inner workings of the markets and excellent analysis capabilities.

In this chapter, we discuss a few of the basic techniques used by swing traders along with the risks that are unique to the discipline. We also talk about tax issues and account restrictions unique to swing trading.

Selecting Stocks Carefully

Swing trading is a technical discipline. Although no hard‐and‐fast rule defines it, swing traders often trade in 100‐share increments and usually limit the number of simultaneous positions to ten or fewer. A swing trade can last as little as a few hours to as long as a few weeks, but typical swing trades span no more than a few days. On this kind of timescale, fundamental analysis has little impact on a stock’s price movement; therefore, swing traders make stock selections using technical‐analysis tools. Careful trade management is crucial to swing‐trading success.

Swing trading is a technical discipline. Although no hard‐and‐fast rule defines it, swing traders often trade in 100‐share increments and usually limit the number of simultaneous positions to ten or fewer. A swing trade can last as little as a few hours to as long as a few weeks, but typical swing trades span no more than a few days. On this kind of timescale, fundamental analysis has little impact on a stock’s price movement; therefore, swing traders make stock selections using technical‐analysis tools. Careful trade management is crucial to swing‐trading success.

Stock selection is even more important for swing trading than it is for position trading. When you’re looking for a stock to move right away, you base your decisions on selection criteria that are different from when you’re positioning for a move that may last several weeks to several months. Following are a few of the important selection criteria that swing traders use:

- Volume and liquidity: Swing traders typically focus on actively traded and relatively large stocks. The goal is finding stocks that are easy to buy, sell, and sell short. When trading time frames are short, you need to be able to execute your orders quickly. Unfortunately, stocks with the greatest liquidity and trading volumes are closely followed by the largest number of professional traders, which usually constrains the number of profitable swing‐trading opportunities, so swing traders often scout opportunities outside of the 25 or so stocks that have the highest trading volume and greatest liquidity.

- Trending: Trending stocks provide the best opportunity for swing‐trading profits. You may use either the methods described in Chapter 9 for identifying trending stocks or the average directional index (ADX) indicator. This indicator has three components: the ADX reading and two directional movement indicators — the +DMI and the –DMI. An ADX reading of more than 30 or so indicates a trending stock. A comparison of the two DMIs shows you whether the ADX is trending up or down. If the value of +DMI is larger than the value of –DMI, then the stock is trending higher. If the value of –DMI is larger than the value of +DMI, the stock is trending lower. The ADX indicator is included in most charting applications.

- Volatility: Swing traders depend on larger, or more volatile, short‐term moves for profits. As a result, they want to trade stocks that have histories of making large moves in short periods of time. One popular approach to finding them is keeping an eye on the average daily ranges (ADRs), which are simple moving averages that track the day‐to‐day differences between an individual stock’s daily high and low prices. If you’re swing trading, you want stocks that show high ADRs. Volatility also can be measured using historic volatility, which we discuss in the later “Trading volatility” section.

- Sector selection: Just like position trading, swing traders try to trade stocks in the strongest sectors, and the weakest sectors are candidates for short sales. Use the techniques described in Chapter 13 to identify strong and weak sectors.

- Tight spreads: As a means of controlling slippage (see Chapter 16), you need to pay close attention to the difference between the bid and ask prices of the stocks you’re considering as swing‐trading prospects. Stocks with wide spreads make profitable swing trading difficult. Low‐priced stocks rarely are good candidates for swing trading because the spread, as a percentage of the stock price, is usually too wide.

Looking at Swing‐Trading Strategies

Swing trading fluctuates between the use of trend‐following and countertrend strategies:

- When a stock is trending strongly, swing traders primarily employ trend‐following techniques but may use countertrend techniques to fine‐tune exit points.

- When a stock is range bound, swing traders use countertrend methods to identify entry and exit points.

Trading trending stocks

Technical‐analysis patterns that we cover in Chapters 9 through 13 are all applicable to swing trading. Patterns repeat in all time frames; the difference is in how swing traders use and interpret these common patterns. Trend‐following strategies are more aggressive for swing trading than they are for position trading. Although swing traders use some of the same indicators and patterns used by position traders, they often use them in different ways. We explain a few examples in the sections that follow.

Technical‐analysis patterns that we cover in Chapters 9 through 13 are all applicable to swing trading. Patterns repeat in all time frames; the difference is in how swing traders use and interpret these common patterns. Trend‐following strategies are more aggressive for swing trading than they are for position trading. Although swing traders use some of the same indicators and patterns used by position traders, they often use them in different ways. We explain a few examples in the sections that follow.

Trading pullbacks

A pullback is another name for a consolidation within a trend. Consolidation patterns include the flags and pennants discussed in Chapter 10. Swing traders use daily charts and intraday charts — ranging from 1‐minute bars to 60‐minute bar charts — to identify the dominant short‐term trend and any pullback patterns within the trend. They try to enter a position when the price of a targeted stock stops declining or pulling back so they can capture the next move higher in the trend. Conceptually, pullback trading is simple, but in practice, it’s trickier than it sounds.

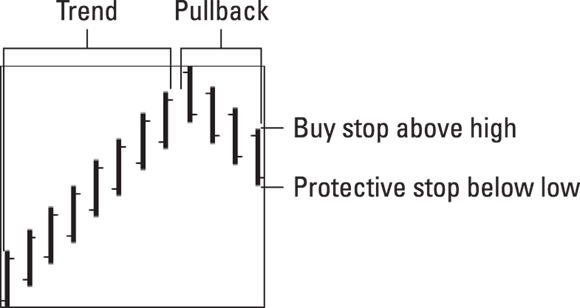

After you identify a trending stock and find a flag or pennant pullback pattern by visually examining the daily charts, you must try to enter a position just as the pullback is ending. The classic setup is finding an orderly pullback in which the high of each bar on a chart of the pullback is lower than the previous one. Figure 17‐1 shows an idealized example of the type of pattern you’re trying to find.

Entering a position is done by placing a buy stop order with your broker. A buy stop is like any stop order; when the price is hit, the order is executed. (See Chapter 12 for details.) Entering a position to trade pullbacks is an iterative process, so we recommend using a day order instead of a good‐’til‐canceled order (see Chapter 15). Here are the steps:

- Select your buy stop price so it’s just above the intraday high price shown in the last bar of the chart.

If the stock price trades above your buy stop price, your order is executed.

Otherwise, the order is canceled at the end of the day.

- As long as you’re still interested in this trade, adjust your buy stop price to just above the intraday high of the most recent bar on the chart and reenter your order.

- After your order is filled, place a stop‐loss order (see Chapter 12) using a stop price just below the intraday low of the lowest bar in the pullback on the chart.

- As long as the trade is active, continue adjusting the stop price to be just below the intraday low of the most recent bar on the chart.

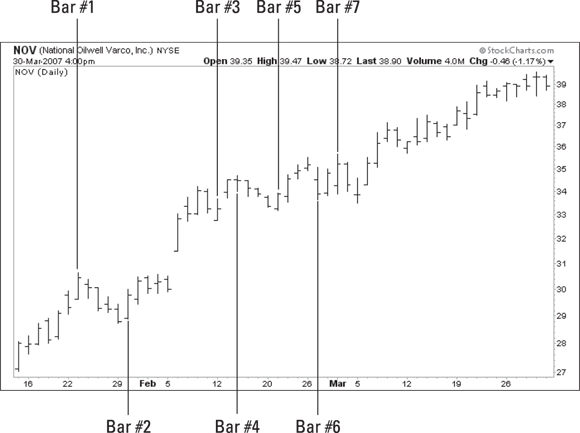

Figure 17‐2 is a price chart of the stock of National Oilwell Varco, Inc. (NOV), that’s showing a strong uptrend. Several opportunities for trading pullbacks are also shown on this chart.

The first pullback occurred after NOV traded to a new high of $30.44 on January 23, 2007. That new high is labeled Bar #1 on the chart. After identifying the pullback, you begin the iterative process of setting the buy stop price just above the high of the last bar on the chart. At the end of each day, you reset the buy stop price, again setting it just above the high of the last bar, and reenter the order.

In this example, the trade is triggered on Bar #2, which occurred January 30. You had set the buy price just above the January 29 high, which was $29.44. NOV opened January 30 at $28.90. The trade was triggered when the stock climbed above $29.45, rising as high as $30.01 before backing off to close at $29.80. You could expect your order to fill very near your $29.45 buy stop price. For the sake of our example, we assume a fill price of $29.50.

Immediately following the trade execution, you set a stop‐loss order below the low of the previous bar, $28.74 in this case. Or you may set the low at $28.90, the trade day’s low. Either approach makes sense, so it’s your call. Each day that the trade remains active, reset the stop order just below the low of the previous bar on the chart.

The thrust of this trend lasted through February 12, 2007, a duration of ten trading days. This position hit the stop price on February 12, labeled Bar #3 on the chart in Figure 17‐2, when the stock traded below the February 9 low of $33.03.

The next opportunity to trade a pullback occurred during the pullback that began after NOV traded at a new high on February 13, labeled Bar #4. The trade was triggered on February 21, shown as Bar #5, when NOV traded above the February 20 high of $33.85. The position hit its stop price on February 27, shown as Bar #6, when the stock traded below the February 26 low of $34.91. Given slippage and transaction costs, this trade was no better than a break‐even trade.

The next opportunity came following the poorly formed pullback that began with Bar #6. You entered the trade on Bar #7 when NOV traded above the February 28 intraday high of $35.00. The trade would stop out two bars later for a loss.

NOV traded at $66.32 on April 26, 2012. There were many trading opportunities for a swing trader using this stock between 2009 and 2013. Practice finding good swing trades by working with historical charts and look for trends similar to the ones noted earlier.

Swing trades don’t always work out, of course. Complications and frequent losing trades always are possible.

Surfing channels

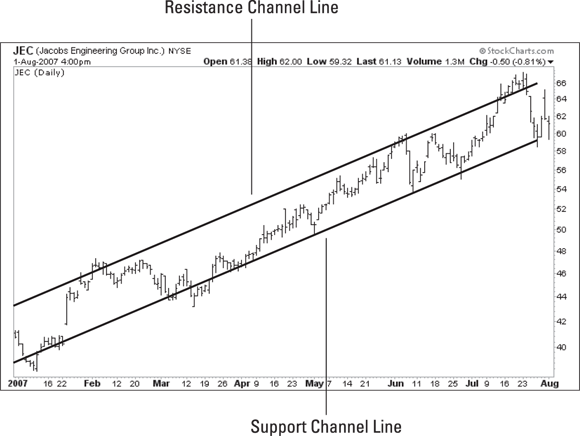

Another trend‐following approach to swing trading uses a channeling strategy to identify entry and exit points. Chapter 10 explains the channeling strategy and how to construct the channel lines. After you identify a channel on the daily charts, you treat channel lines as lines of support and resistance. Figure 17‐3 shows an example.

After identifying support and resistance levels for a channeling stock, you can monitor its chart for reversals near the channel lines. As the stock price approaches the lower or support channel line, you have an opportunity to take a position in the direction of the trend. After entering a position, your stop‐loss order is entered just below the support channel line. As the stock price approaches the upper or resistance channel line, it signals when to exit your position.

You can use intraday charts to fine‐tune this strategy. As a stock price falls toward its lower channel or support level, begin watching intraday charts for indications that the stock is changing direction and heading higher. If you see an intraday low near the location of the support channel line, followed by a higher high and a higher low, you can use that situation as an entry signal. After entering a long position, you place a stop‐loss order just below the support channel line.

You can use intraday charts to fine‐tune this strategy. As a stock price falls toward its lower channel or support level, begin watching intraday charts for indications that the stock is changing direction and heading higher. If you see an intraday low near the location of the support channel line, followed by a higher high and a higher low, you can use that situation as an entry signal. After entering a long position, you place a stop‐loss order just below the support channel line.

You hold this long position until either it stops out or the stock approaches its upper channel‐resistance level. Again, you need to monitor the intraday charts for hints of a change in direction and exit the trade whenever you see the reversal. After that, you wait for the stock to head back toward the lower channel line to initiate a new long trade.

Trading range‐bound stocks

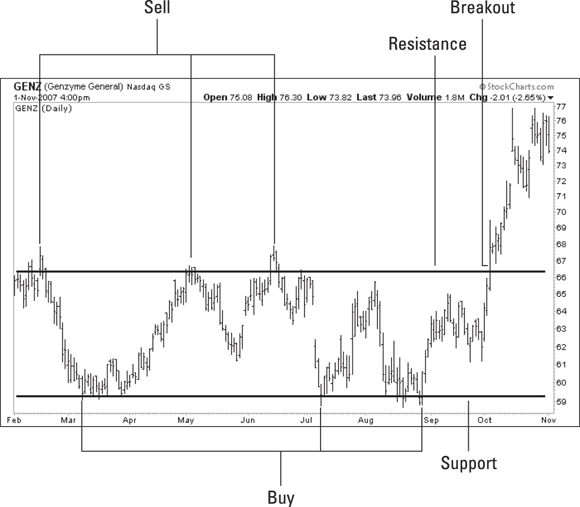

Unlike the typical position trader, a swing trader is more likely to use countertrend strategies (see Chapter 16) and actively participate when a stock is range bound. The swing trader tries to make trades based on price movements from the bottom to the top of the range and back down again. You can use either daily or weekly charts to identify the trading range. An example using a daily chart is shown in Figure 17‐4.

Your trading approach to range‐bound stocks is similar to the one for trading a channeling stock that we describe in the previous section, “Surfing channels.” As the stock price approaches the support level, which is just above $59.00 in Figure 17‐4, you have an opportunity to take a position. You can use a few approaches to enter a position.

You can, for example, simply choose to place a buy order using a limit price just above the support line. Another approach that may give you a little more control and provide better entry and exit points is to monitor the stock to find pivot points as it trades near the support line. A pivot point is a three‐bar pattern in which the low price of the middle bar is lower than the lows of the bars on either side of it. The entry and exit points for this kind of trading are similar to the ones used for trading based on a pullback pattern. After identifying a pivot point, you enter an order on the next bar. You place the protective stop either immediately below the low of the pivot bar or just below the support channel line.

Using intraday charts is another way to fine‐tune your entry point. As the stock approaches the support line, you enter a position as soon as you see a reversal pattern on the intraday charts — for example, a higher high and a higher low, or a gap higher (see Chapter 10).

Using intraday charts is another way to fine‐tune your entry point. As the stock approaches the support line, you enter a position as soon as you see a reversal pattern on the intraday charts — for example, a higher high and a higher low, or a gap higher (see Chapter 10).

You exit these kinds of positions when the stock reverses near its resistance line. You can then take a short position in the stock — using any of the entry techniques described earlier — or wait for the stock to return to the support line to initiate another long position.

If the stock breaks through its upper resistance level, you interpret that condition exactly the way a position trader does — a very bullish indication that the stock is likely beginning a new trend, immediately closing any open short positions and converting to a trend‐following strategy (see the earlier section “Trading trending stocks”).

Trading volatility

Swing traders try to trade stocks that move up and down more than average. To find these stocks, swing traders spend a great deal of effort measuring and analyzing volatility, usually in the form of historic volatility. Although the math required to calculate historic volatility is complex, the concept is simple. Historic volatility measures a stock’s price movement. The faster it moves, the higher the historic volatility. Fortunately, many charting and analysis programs include a method for calculating historic volatility, so you don’t have to program in the formula.

Historic volatility isn’t concerned with the direction of a stock’s price movement. A high historic volatility value doesn’t reveal whether a stock’s price is rising or falling. Although swing traders want to know that a stock trends in one direction or the other, they don’t really care which direction. Downside movement is just as attractive as upside movement to the swing trader.

Historic volatility isn’t concerned with the direction of a stock’s price movement. A high historic volatility value doesn’t reveal whether a stock’s price is rising or falling. Although swing traders want to know that a stock trends in one direction or the other, they don’t really care which direction. Downside movement is just as attractive as upside movement to the swing trader.

You can use historic volatility for swing trading in several different ways. One popular approach uses historic volatility for finding stocks that have been very volatile but currently are experiencing quiet periods. These temporarily quiet stocks often return to previous levels of historic volatility, and that presents a swing‐trading opportunity. Swing traders identify these stocks by comparing measurements of historic volatility across longer and much shorter periods of time and expressing that comparison as a ratio. The ratio looks like this:

You can use historic volatility for swing trading in several different ways. One popular approach uses historic volatility for finding stocks that have been very volatile but currently are experiencing quiet periods. These temporarily quiet stocks often return to previous levels of historic volatility, and that presents a swing‐trading opportunity. Swing traders identify these stocks by comparing measurements of historic volatility across longer and much shorter periods of time and expressing that comparison as a ratio. The ratio looks like this:

One common ratio compares a 6‐day historic volatility with a 100‐day historic volatility. Whenever the value of that ratio is less than 50 percent, the stock is a candidate for a swing‐trading position.

After this stock takes a short low‐volatility rest, it is likely to return to its historic level of volatility with a fast move. Remember that volatility tells you nothing about the direction of price movements, so to get around this limitation, be sure to place buy and sell‐short stop orders, respectively, above the high and below the low of the current bar. When the stock decides which way it will go, one of your stop orders will be filled, and that should get you pointed in the right direction. Using more traditional technical‐analysis tools is another approach to evaluating a stock’s current trend so you can then trade in the direction of that trend.

Risks accompany both approaches. Using the first approach, the stock may take off in one direction and quickly reverse course, and you may end up holding a position with a highly volatile stock heading the wrong way. This same scenario also can happen with the second approach. Another potential problem occurs when the stock price gaps through your entry order because your order may end up getting filled at a price that’s significantly different from what you expected.

Risks accompany both approaches. Using the first approach, the stock may take off in one direction and quickly reverse course, and you may end up holding a position with a highly volatile stock heading the wrong way. This same scenario also can happen with the second approach. Another potential problem occurs when the stock price gaps through your entry order because your order may end up getting filled at a price that’s significantly different from what you expected.

Money management issues

Because of the short duration of each trade, swing trading generates a large volume of trades. Execution and slippage costs (see Chapter 12) can be very high. Profits are relatively small when measured on each trade, so losses must be carefully controlled.

You need to adhere closely to the money management rules we discuss in Chapter 12. In addition, each swing trade must represent only a small percentage of your trading capital. Ten percent of your capital per trade is too much. Risking less than 5 percent — and perhaps as little as 2 percent — of your trading capital on any one swing trade is a more conservative approach. This approach is similar to the one used by professional traders. When profit potential is small, don’t take big risks, or you won’t be a swing trader for long.

You need to adhere closely to the money management rules we discuss in Chapter 12. In addition, each swing trade must represent only a small percentage of your trading capital. Ten percent of your capital per trade is too much. Risking less than 5 percent — and perhaps as little as 2 percent — of your trading capital on any one swing trade is a more conservative approach. This approach is similar to the one used by professional traders. When profit potential is small, don’t take big risks, or you won’t be a swing trader for long.

Using Options for Swing Trading

Stock options can be used as substitutes for the underlying stocks when swing trading. A stock option is a limited‐duration contract that grants the option buyer the right to either buy or sell a stock for a fixed price. The option seller, usually called the option writer or the option grantor, is granting the right to the option buyer to either buy or sell a specific stock for a fixed price.

Each option represents 100 shares of stock. A call is an option to buy 100 shares of a specified stock. The call buyer is acquiring a limited‐duration right to buy 100 shares of a stock from the option grantor at a fixed price, called the strike price. A put is an option to sell 100 shares of a specified stock. The put buyer is acquiring a limited‐duration right to sell 100 shares of a stock to the option grantor at the specified strike price. (Options are discussed in more detail in Chapter 19.)

You can, for example, substitute a call option for a long stock position or a put option for a short stock position. You realize any profits by selling the options outright, or you can exercise an option and take possession of the shares of stock. Swing traders, however, are more likely to sell the option than exercise it.

Although using options as stock substitutes has several advantages, doing so also has risks of its own. The primary advantage: An option costs far less than the underlying stock, which enables you to limit your risk to the price of the option.

Each option is a substitute for 100 shares of stock or 100 shares of an exchange‐traded fund (ETF). One call option, for example, gives you the ability to buy 100 shares of a stock at a fixed price for a certain length of time. As an example, assume that the QQQQ exchange‐traded fund is trading at $27.10 per share. At the time of the example, you can buy one call option with a $27 strike price for $2.26 per share, or a total of $226, before transaction costs. That one option enables you to buy 100 shares of QQQQ for $27 before the option expires.

Say that the option in this example has approximately six weeks before expiration. Your option position is therefore profitable as long as the QQQQ exchange‐traded fund trades above $29.26 (excluding transaction costs) before the expiration date. (We determined the break‐even price by adding the $27 strike price to the $2.26 cost of the option, which totals $29.26.) Your risk is the price of the option. In other words, you can’t lose any more than $2.26 per share, or $226, on this trade.

Unfortunately, option pricing isn’t as straightforward as stock pricing. The preceding pricing example is merely a snapshot that varies with changes in the price of the QQQQ exchange‐traded fund. The following factors affect option prices:

- Options expire and their prices decay as the expiration date draws closer. This price decay is caused by the option’s falling time value.

- The prices of current‐month options decay at faster rates than longer‐dated options.

In percentage terms, out‐of‐the‐money options often move at a faster rate than in‐the‐money options. (An option is said to be in the money if it has intrinsic value, and it’s out of the money if it has no intrinsic value. For a call option, that means the price for the underlying stock is greater than the specified strike price. For a put, that means the price for the underlying stock is less than the strike price. See Chapter 19 for additional details.)

Trading options that are far out of the money is rarely a good strategy.

Trading options that are far out of the money is rarely a good strategy.

- Volatility is a component of option pricing. Option prices rise and fall as the volatility of the stock rises and falls.

- Except in a few unusual circumstances, an option’s price doesn’t move in lockstep with the underlying stock’s price. If a stock moves $1, the option, in general, moves some amount less than $1. The more an option is in the money, the closer the change in an option’s price will be to the change in the underlying stock’s price.

Another factor to consider when substituting options for stocks is that the option’s spread, or the difference between the bid price and the ask price, is extremely wide when considered as a percentage of the option price.

Before you decide to substitute options for your stock trades, make sure that you understand the option‐pricing model; we discuss it in Chapter 19. And be careful that you don’t overtrade with options. If you normally buy 100 shares of a stock, then you need to buy only one option contract. Although the price of ten option contracts may be attractive when compared with the price of the stock, ten option contracts nevertheless represent 1,000 shares of stock. When buying options for ten times the number of shares that you normally trade, you’re increasing your exposure to risk by a factor of ten.

When trading options, you can’t make money in as many ways as you can lose it. Being right on the stock’s direction but still losing money on an option trade is possible because of pricing issues. That’s why gaining an understanding of the option‐pricing model is so important before you try to substitute an option for a stock. We discuss options more fully in Chapter 19.

When trading options, you can’t make money in as many ways as you can lose it. Being right on the stock’s direction but still losing money on an option trade is possible because of pricing issues. That’s why gaining an understanding of the option‐pricing model is so important before you try to substitute an option for a stock. We discuss options more fully in Chapter 19.

Getting a Grip on Swing‐Trading Risks

Swing trading is risky and demands a great deal of time. As a swing trader, you must monitor the market during every trading hour. You also must be able to control your emotions so you stay focused and trade within your plan.

Ask any swing trader; you’re likely to hear that strict adherence to money management reduces risk. The counterargument is that swing trading exposes a great deal of capital to risk but makes only small profits. Some traders are able to swing trade profitably, but you need to realize that the odds are stacked against you. Only you can decide whether it’s worth the effort.

Some argue that swing trading combines the worst aspects of position trading with the worst aspects of day trading. Like in day trading, swing‐trading profits are small, and slippage costs are high. Swing‐trading positions are held overnight, so swing traders can’t take advantage of the special margin provisions that are available to day traders, who close all positions by the end of the trading day. And swing traders are subject to the same account restrictions as day traders are, but they may not qualify for the special tax advantages afforded to full‐time day traders.

Taxes (of course)

Special tax treatment is available from the IRS for full‐time traders. The benefits enable full‐time traders to be taxed as a business rather than as an investor, and that means you can deduct the cost of the computer hardware and software used for trading, and you can treat your home‐office expenses, including the costs for data acquisition, as ordinary business expenses. Furthermore, you can convert capital gains and losses to ordinary gains and losses under the Mark‐to‐Market accounting rules in the IRS Code Section 475. Mark‐to‐Market rules enable you to avoid wash‐sale regulations and deduct all losses against other income without hitting the $3,000 cap imposed on other investors.

Unfortunately, swing traders do not necessarily trade every day, so some swing traders have a difficult time qualifying for these special tax provisions. If you are unable to qualify as a full‐time trader, then your swing trades will be taxed in the same way as every other investor. You must report gains and losses on IRS Schedule D, and you must adhere to wash‐sale regulations. You may also run into difficulty if you try to report your trading expenses as a business deduction.

The rules are complex. You need to consult with your tax advisor to determine your eligibility. Information about the rules is in IRS Publication 550, in the last section of Chapter 4, “Special Rules for Traders in Securities.” We provide more information in Chapter 18.

Pattern‐day‐trading rules apply

Swing traders are subject to the same rules as day traders. If a swing trader opens and closes a position in a single stock during one day and does this more than four times in a five‐day period, the swing trader is categorized as a pattern day trader. If this occurs, the swing trader must maintain an equity balance of $25,000 in his account or his broker will prohibit him from making any day trades. Additional information about the pattern‐day‐trading rules is provided in Chapter 18.

This scenario actually is quite likely for the swing trader because of the number of stops that are hit. As a swing trader, you may as well plan to maintain a minimum equity balance in your trading account in excess of $25,000.

Picking the right stocks for swing trading

Picking the right stocks for swing trading Using specific strategies in swing trading

Using specific strategies in swing trading Substituting options for stocks

Substituting options for stocks Identifying tax issues and account restrictions for swing traders

Identifying tax issues and account restrictions for swing traders Swing trading is a technical discipline. Although no hard‐and‐fast rule defines it, swing traders often trade in 100‐share increments and usually limit the number of simultaneous positions to ten or fewer. A swing trade can last as little as a few hours to as long as a few weeks, but typical swing trades span no more than a few days. On this kind of timescale, fundamental analysis has little impact on a stock’s price movement; therefore, swing traders make stock selections using technical‐analysis tools. Careful trade management is crucial to swing‐trading success.

Swing trading is a technical discipline. Although no hard‐and‐fast rule defines it, swing traders often trade in 100‐share increments and usually limit the number of simultaneous positions to ten or fewer. A swing trade can last as little as a few hours to as long as a few weeks, but typical swing trades span no more than a few days. On this kind of timescale, fundamental analysis has little impact on a stock’s price movement; therefore, swing traders make stock selections using technical‐analysis tools. Careful trade management is crucial to swing‐trading success. Technical‐analysis patterns that we cover in

Technical‐analysis patterns that we cover in

Risks accompany both approaches. Using the first approach, the stock may take off in one direction and quickly reverse course, and you may end up holding a position with a highly volatile stock heading the wrong way. This same scenario also can happen with the second approach. Another potential problem occurs when the stock price gaps through your entry order because your order may end up getting filled at a price that’s significantly different from what you expected.

Risks accompany both approaches. Using the first approach, the stock may take off in one direction and quickly reverse course, and you may end up holding a position with a highly volatile stock heading the wrong way. This same scenario also can happen with the second approach. Another potential problem occurs when the stock price gaps through your entry order because your order may end up getting filled at a price that’s significantly different from what you expected.