Chapter 16

Developing Your Own Powerful Trading System

IN THIS CHAPTER

Distinguishing different trading systems

Distinguishing different trading systems

Identifying the tools and data required for system development and testing

Identifying the tools and data required for system development and testing

Maintaining a trading journal

Maintaining a trading journal

Assessing trading systems that you can buy

Assessing trading systems that you can buy

A trading system is a collection of technical and fundamental analyses tools woven together to generate buy and sell signals. Trading systems often are built using common indicators, oscillators, and moving averages (see Chapter 11). You can combine these various technical analysis tools to create a virtually unlimited number of trading systems. For the novice trader, the advantage to this approach is that you don’t need to invent something new to create and personalize an effective system.

The downside, however, is equally obvious. Many traders use these common tools and end up with a system that offers little competitive advantage and only modest (if any) profits. In addition, these systems can be difficult to use because the signals of one trading system mirror the signals of many others, which makes entering and exiting positions troublesome.

Ultimately, you want to develop or adapt a trading system that closely fits your personality, trading time frame, schedule, and trading objectives. This chapter helps you methodically develop and add to a trading approach that uses your own personalized repertoire of trading systems. It also helps you recognize and avoid destructive and costly habits that can sabotage your trading efforts. In addition, we discuss ways for you to evaluate some of the claims made about trading systems that are for sale and whether buying someone else’s trading system makes sense.

Understanding Trading Systems

Although individual trading systems differ in many ways, you can think about them on the basis of a couple of broad characteristics to get a good overview. The first characteristic has to do with the two ways a trader interacts with the system. In this case, trading systems are either

- Discretionary trading systems: A system that presents trading candidates for your consideration but leaves the final trade execution decision to you.

- Mechanical trading systems: A computer‐based system that automatically generates buy and sell signals that will always be traded.

The other way to categorize a trading system is by how it treats trends in the markets. In this case, trading systems are either

- Trend‐following trading systems: A system that tries to identify trade entry and exit points for new or existing trends.

- Countertrend trading systems: A system that tries to identify trade entry and exit points by finding tops and bottoms.

Although these categorizations are not mutually exclusive of each other (mechanical and discretionary systems, for example, can both be trend‐following systems), each approach has its fair share of both champions and detractors, so we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each type of system in the sections that follow.

As you read through our descriptions of the trading systems, understand that no system generates profits without any losing trades. Put another way, no system works in every situation. Keep that fact firmly in mind when you’re developing and designing your own personal trading system. Your goal is to design a trading system that is useful to you across a large number of stocks and a large number of situations. Believe us when we say that you will run into trouble whenever you try to tailor a trading system to a specific stock. Additionally, try to ensure that your system works across long periods of time and throughout many different market conditions.

As you read through our descriptions of the trading systems, understand that no system generates profits without any losing trades. Put another way, no system works in every situation. Keep that fact firmly in mind when you’re developing and designing your own personal trading system. Your goal is to design a trading system that is useful to you across a large number of stocks and a large number of situations. Believe us when we say that you will run into trouble whenever you try to tailor a trading system to a specific stock. Additionally, try to ensure that your system works across long periods of time and throughout many different market conditions.

Discretionary systems

A discretionary trading system makes you an active participant in all phases of the trades you make and provides you with a great deal of leeway when making trading decisions. With this approach, evaluating the economic data, analyzing the broad‐market indexes, determining which sectors are showing strength, and identifying high‐relative‐strength stocks that are breaking out of long trading ranges and hoping to catch a new trend all are up to you. You make decisions based on what you see in the charts and in the fundamental economic data, and you enter and exit (buy and sell) positions based on that information. When you’re relying on a discretionary trading system, your judgment is a key factor.

A discretionary system requires a great deal of discipline, which can cause problems for some traders. This type of system works well for traders who are capable of making good decisions quickly under pressure. But discretionary systems may prove troublesome if you allow your emotions to wreak havoc with your ability to think clearly, act rationally, and make thoughtful trading decisions.

A discretionary system requires a great deal of discipline, which can cause problems for some traders. This type of system works well for traders who are capable of making good decisions quickly under pressure. But discretionary systems may prove troublesome if you allow your emotions to wreak havoc with your ability to think clearly, act rationally, and make thoughtful trading decisions.

When emotions cloud your trading decisions, you may end up

- Overtrading

- Prematurely liquidating your positions

- Holding positions too long

- Anticipating trading signals in attempts to get better entry and exit prices

Another problem with discretionary systems is that they’re difficult to test. This is possibly their greatest drawback. System testing is useful because it helps you understand situations in which an indicator works well and those in which it fails. With a discretionary system, you can test the indicators, but you can’t reliably test your discretion. We talk about testing trading systems in more detail later in this chapter.

Another problem with discretionary systems is that they’re difficult to test. This is possibly their greatest drawback. System testing is useful because it helps you understand situations in which an indicator works well and those in which it fails. With a discretionary system, you can test the indicators, but you can’t reliably test your discretion. We talk about testing trading systems in more detail later in this chapter.

Mechanical systems

A mechanical system addresses some of the problems that arise when using discretionary systems. Mechanical systems usually are computer‐based programs that automatically generate buy and sell signals based on technical and/or fundamental data. You’re expected to blindly follow the resulting trading signals. Put another way, mechanical trading systems take your judgment out of the equation. In fact, some mechanical systems even enter buy and sell orders directly with your broker without your intervention.

If your greedy impulses or your fear of losing routinely cause you to make poor trading decisions, a mechanical system may be a better choice for you. An automated approach tends to reduce the stress and anxiety that arise when you have to make difficult decisions quickly. As such, you can make and execute trading decisions in a consistent, methodical way. A mechanical trading system also enables you to automatically include rigorous money management protocols in your trading methodology.

If your greedy impulses or your fear of losing routinely cause you to make poor trading decisions, a mechanical system may be a better choice for you. An automated approach tends to reduce the stress and anxiety that arise when you have to make difficult decisions quickly. As such, you can make and execute trading decisions in a consistent, methodical way. A mechanical trading system also enables you to automatically include rigorous money management protocols in your trading methodology.

Another benefit of the mechanical approach is having the ability to thoroughly test the system. Through testing you can confirm whether your trading system performs the way you expect it to and explore ways to improve your system before actually committing your trading capital. You can adjust and fine‐tune your system after seeing the test results. Unfortunately, fine‐tuning your system may lead to other problems. We discuss ways to avoid them in the later section “Identifying system‐optimization pitfalls.”

Trend‐following systems

Trend following is favored by many technicians for one simple reason: Trends offer excellent opportunities for profit. Unfortunately, the popularity of the trend‐following approach is one of its greatest weaknesses. Too many of these systems generate very similar buy and sell signals, which, in turn, makes outperforming the average trader difficult for any individual trend‐following trader.

Even the best trend‐following systems have a relatively large percentage of failed trades, primarily because they depend on several extremely profitable trades to make up for the large percentage of losing trades. If your trend‐following system is also a discretionary system, your discretion (or lack of it) can cause you to miss a few of these profitable trades. In this case, your overall results will suffer.

Trend‐following systems are typically based on either moving averages or breakout patterns (see Chapters 9 and 11). Moving average–based trading systems are the most popular and can be quite profitable; however, they work only when a stock is trending. These trading systems depend on long‐lasting trends to generate enough profit to outweigh a relatively large number of losing trades. In fact, the number of losing trades can easily outnumber the winning trades with this type of trading system. When a stock is range bound (stuck moving sideways within a specific price range), a moving average–based system generates a large number of losing trades. Because of the high overall number of trades, this system is often accompanied by relatively high transaction and slippage costs (see the later section “Accounting for slippage”). Smart money management protocols are critical when using a trend‐following trading system.

Trend‐following systems are typically based on either moving averages or breakout patterns (see Chapters 9 and 11). Moving average–based trading systems are the most popular and can be quite profitable; however, they work only when a stock is trending. These trading systems depend on long‐lasting trends to generate enough profit to outweigh a relatively large number of losing trades. In fact, the number of losing trades can easily outnumber the winning trades with this type of trading system. When a stock is range bound (stuck moving sideways within a specific price range), a moving average–based system generates a large number of losing trades. Because of the high overall number of trades, this system is often accompanied by relatively high transaction and slippage costs (see the later section “Accounting for slippage”). Smart money management protocols are critical when using a trend‐following trading system.

You can make some adjustments to a trend‐following system that may improve its performance. For example, you can insist that its trading signals be confirmed by another condition before actually entering any positions. If your system triggers a buy signal, for example, you may want to see whether the signal remains in effect for at least a day or two before entering a position. We show some examples of moving‐average and breakout systems, along with some ideas to improve the performance of these systems, in the section “Developing and Testing Trading Systems,” later in this chapter.

You can make some adjustments to a trend‐following system that may improve its performance. For example, you can insist that its trading signals be confirmed by another condition before actually entering any positions. If your system triggers a buy signal, for example, you may want to see whether the signal remains in effect for at least a day or two before entering a position. We show some examples of moving‐average and breakout systems, along with some ideas to improve the performance of these systems, in the section “Developing and Testing Trading Systems,” later in this chapter.

Countertrend systems

For many traders, the quest to find a profitable countertrend trading system is all consuming. Countertrend systems appear desirable because their goal is to buy low and sell high. These systems try to identify inflection points, or the moments when stocks change direction, so traders can take positions close to when they occur. This approach may work in a few narrowly defined situations, such as in a trading range (Chapter 9) or a trend channel (Chapter 10), but it’s likely to fail in a spectacular and expensive way if attempted on a broader scale.

The vast majority of trading systems follow market trends. This is simply a higher‐probability practice. Trend‐following systems tend to outperform countertrend systems, especially for position traders. Swing traders and some day traders sometimes use a countertrend approach, but even then, they usually do so in conjunction with a trend‐following component. (Flip to Chapters 17 and 18 for more about swing trading and day trading.)

Countertrend systems usually depend on oscillating indicators, reversal patterns, and channeling strategies to find turning points. Some countertrend systems also are based on cycle theory, and others are based on volatility, expansion, and contraction.

We discourage you from spending too much time evaluating countertrend systems, at least until you’re confident in your ability to use trend‐following systems to successfully make your trades. Countertrend systems generate a large volume of trades, and the more you trade, the more you spend on transaction and slippage costs. These costs alone often swamp potentially profitable systems. Although a countertrend strategy can sometimes work profitably in a trading range or trend channel (see Chapters 9 and 10), it’s still risky, especially for a new trader. Until you can confidently (and honestly) consider yourself a thoroughly experienced trader, stick with the proven techniques that are more likely to lead to profitable results over the long term.

We discourage you from spending too much time evaluating countertrend systems, at least until you’re confident in your ability to use trend‐following systems to successfully make your trades. Countertrend systems generate a large volume of trades, and the more you trade, the more you spend on transaction and slippage costs. These costs alone often swamp potentially profitable systems. Although a countertrend strategy can sometimes work profitably in a trading range or trend channel (see Chapters 9 and 10), it’s still risky, especially for a new trader. Until you can confidently (and honestly) consider yourself a thoroughly experienced trader, stick with the proven techniques that are more likely to lead to profitable results over the long term.

Selecting System‐Development Tools

As a trader, it’s natural to want some way of confirming that your newly designed system can perform profitably before you commit real trading capital. That means you need a way to test your system, which, in turn, means using computer software to precisely define the system and evaluate its performance. Typically, this requires simulating trades by using historical data.

Regardless of whether you decide on a mechanical or a discretionary approach to trading, testing your system brings with it a long list of benefits. Although thoroughly testing a discretionary system is difficult, you can still test the component indicators to learn when they do and don’t provide effective trading signals. To begin, you need a computer, development and testing software, and historical data.

Regardless of whether you decide on a mechanical or a discretionary approach to trading, testing your system brings with it a long list of benefits. Although thoroughly testing a discretionary system is difficult, you can still test the component indicators to learn when they do and don’t provide effective trading signals. To begin, you need a computer, development and testing software, and historical data.

Choosing system‐development hardware

Doing the math that’s required when testing your system can really slow down your computer, and it can generate a lot of data. Almost any computer will do the job when you’re getting started, but if you end up testing many system ideas, you definitely need a large amount of disk storage and a fast computer. The computer equipment required to run a proprietary trading platform, including products such as TradeStation, is usually enough for system development and testing. (See Chapter 4 for more information about the hardware requirements for a typical proprietary trading platform.)

Deciding on system‐development software

You’ll come across a wide array of trading system–development and testing products on the market. Some proprietary trading platforms, such as TradeStation, include system‐testing capabilities. Spreadsheet software, like Microsoft Excel, also is useful for analyzing simple trading systems and the results generated by specialized development and testing software.

Some system‐development programs provide a great deal of statistical analysis, so choosing between spreadsheet tools and system‐development tools is a trade‐off between thoroughness and expediency. After you’ve been through the testing exercises a few times, you get a feel for the strength of each approach. So it’s likely that you’ll decide to use both a system‐development program and a spreadsheet program when creating and testing your new trading systems.

Some system‐development programs provide a great deal of statistical analysis, so choosing between spreadsheet tools and system‐development tools is a trade‐off between thoroughness and expediency. After you’ve been through the testing exercises a few times, you get a feel for the strength of each approach. So it’s likely that you’ll decide to use both a system‐development program and a spreadsheet program when creating and testing your new trading systems.

Trading system–development and testing software

You need to consider several of the following criteria when evaluating your trading system–development and testing software:

- All trading system–development and testing programs use some type of computer language to describe and test your system. Some are terse and difficult to use; others are more intuitive. Traders with strong computer or programming skills have little problem mastering any of these languages, but others may struggle. Pay careful attention to this development language before selecting a system. Be certain that you’re actually able to use the system you choose.

- You need to integrate your trading system with your stock charts. Some system‐development software requires you to actually write computer code that enables you to display your trading system and stock charts simultaneously. Avoid these systems if you’re uncomfortable writing computer code.

- The manner and effectiveness by which your system‐development and testing software reports on how your trading system is performing is critical. Some systems provide extremely detailed statistics about the performance of your trading systems. Others, however, list little more than the buy or sell signals. In general, more information is better.

- Make sure your system‐development and testing programs are capable of exporting the data they generate, historical price data included, into a spreadsheet program for further analysis.

TradeStation (

TradeStation (www.tradestation.com) is the gold‐plated system‐development platform. It has many built‐in tools that make your development and testing job relatively easy. For those of you on tight budgets, one of the less‐expensive alternatives you may want to consider is the charting and system‐development program AmiBroker (www.amibroker.com). Although flexible and powerful, AmiBroker isn’t as feature‐rich or polished as TradeStation, and it requires significantly more effort on your part. For example, AmiBroker includes well‐known technical‐analysis indicators like moving averages and MACD (see Chapter 11), but the number of indicators included is a tiny subset compared with what TradeStation offers. Similarly, you have to use AmiBroker’s formula language to create and enter any other indicators that you may be using.

Spreadsheet software

A spreadsheet program is another invaluable testing and analysis tool. Although a spreadsheet program can’t do everything that a specialized system‐development and testing program can do, it can add quite a bit of analysis horsepower to your system‐development tool kit. You can actually code and test simple trading systems directly into the spreadsheet. You can also evaluate the results of your system tests more thoroughly using the spreadsheet’s built‐in statistical and analysis functions.

You can, for example, copy the price data for a stock into your spreadsheet, calculate moving averages and other indicators, and then configure buy, sell, or sell‐short signals. You can also export trading signals from your system‐development program and import the results into your spreadsheet for further analysis.

One of our favorite spreadsheet projects is calculating the maximum favorable and unfavorable moves after our system has triggered a buy or sell signal. Simple to do, it helps you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your trading system in great detail. You can see whether problems with your trading system may be solved by using different exit procedures or tighter (or looser) stop‐loss points.

One of our favorite spreadsheet projects is calculating the maximum favorable and unfavorable moves after our system has triggered a buy or sell signal. Simple to do, it helps you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your trading system in great detail. You can see whether problems with your trading system may be solved by using different exit procedures or tighter (or looser) stop‐loss points.

For example, although your entry signals may show promise, your exit signals may be causing you to leave a lot of money on the table. These situations are hard to see when you’re working only with charts; however, they sometimes jump out when you’re working with raw data during your spreadsheet analysis. You can find an example using this testing technique in the later section “Using breakout trading systems.”

Finding historical data for system testing

When you need to test your system, you can, of course, test it in real time, with real money, out in the real markets. But getting some idea of how your system will perform before risking your hard‐earned capital is usually a smarter choice. Typically, that means testing your system by evaluating how it performs when simulating trading using historical price data. Ten to twenty years of historical end‐of‐day data for the indexes and stocks you plan to trade is usually more than enough to properly simulate trades for testing your system.

Many sources can provide the data you need to do this. You can download historical data from the Internet, and some online data is available free of charge. Some proprietary trading platforms likewise include access to historical data. You may want to get data from more than one source to confirm its accuracy.

Yahoo Finance provides free historical data and permits you to download the data into a spreadsheet. To access the Yahoo data feed, get a quote for the stock and select “Historical Data.” Then click “Download Data.”

Yahoo Finance provides free historical data and permits you to download the data into a spreadsheet. To access the Yahoo data feed, get a quote for the stock and select “Historical Data.” Then click “Download Data.”

Many online services offer data in a more convenient format but for a price. Some sell historical data recorded on CDs. Sources for intraday price data also are available. Here are the URLs for a few of the many sites offering various forms of historical data:

- Historical data:

- Intraday data:

- Historical data on CD:

Developing and Testing Trading Systems

The ideas that you may want to include in your system development and testing are virtually limitless. Many new traders begin system testing by combining a few off‐the‐shelf indicators in an effort to obtain better trading results. Doing so is as good a place as any to begin.

However, we want to caution you to keep your systems simple enough that you can understand not only the system but also the result. Simplicity usually is better when trading, especially when you’re first becoming familiar with the processes of system development and testing. We describe the process by looking at a couple of examples in the sections that follow.

Working with trend‐following systems

Many trend‐following systems use a moving average for their starting points. In this trend‐following example, the system is designed for position trading, which means we use a relatively long moving average. Short selling isn’t permitted with this simple system.

The first step is to define buy and sell rules for your initial testing. The actual code for defining these rules depends on your specific system‐development package. Therefore, trading rules are described as generally as possible. The rules for an initial test may look like this:

- Buy at tomorrow’s opening price when today’s price crosses and closes above the 50‐day exponential moving average (EMA).

- Sell at tomorrow’s opening price when today’s price crosses and closes below the 50‐day EMA.

To test whether using a moving average as a starting point is a good idea in a trend‐following system, apply these two rules to ten years of historical data for the stocks of your choice. After testing this idea, you find that this simple system works fairly well when stock prices are trending, but it’s likely to trigger many losing trades when the prices of stocks are range bound. You can try to avoid these losing trades, and possibly improve your overall trading results, by filtering out trading‐range situations. One way to accomplish that goal is by changing the buy rule to read as follows: Buy at tomorrow’s open when the following conditions are true:

- Today’s closing price is above the 50‐day EMA.

- The stock crossed above the 50‐day EMA sometime during the last 5 days.

- Today’s 50‐day EMA is greater than the 50‐day EMA from 5 days ago.

These added conditions serve as signal confirmation. When you test these rules, you find they reduce the number of whipsaw trades for most stocks, but they’re also likely to delay buy and sell signals on profitable trades and thus usually result in smaller profits on those trades. However, this adjustment makes the overall system more profitable because the number of losses is reduced.

You can find out whether other changes that you can make in your simple system can actually improve profitability. You may, for example, test different types of moving averages. Try, for example, a simple moving average (SMA) instead of an exponential moving average (EMA). Or you may want to try using different time frames for your moving average, such as 9‐day, 25‐day, or 100‐day moving averages. See Chapter 11 for more details about the multiple types of moving averages.

Identifying system‐optimization pitfalls

Most system‐development and testing software comes equipped with a provision for system optimization, which allows you to fine‐tune the technical analysis tools used in your trading system. You can, for example, tell the system to find the time frame of the moving average that produces the highest profit for one stock and then ask it to do the same thing for a different stock. Some systems enable you to test this factor simultaneously for many stocks.

Although this approach is alluring, using it is likely to cause you trouble. If you find, for example, that a 22‐day moving average works best for one stock, a 37‐day moving average works best for the next stock, and another stock performs best using a 74‐day moving average, you’re going to run into problems. The set of circumstances leading to these optimized results won’t likely repeat in precisely the same way again in the future. We can almost guarantee that whatever optimized parameters you may find for these moving averages won’t be the optimal choices when trading real capital.

Although this approach is alluring, using it is likely to cause you trouble. If you find, for example, that a 22‐day moving average works best for one stock, a 37‐day moving average works best for the next stock, and another stock performs best using a 74‐day moving average, you’re going to run into problems. The set of circumstances leading to these optimized results won’t likely repeat in precisely the same way again in the future. We can almost guarantee that whatever optimized parameters you may find for these moving averages won’t be the optimal choices when trading real capital.

This is a simple example of a problem that’s well known to scientists and economists who build mathematic models to forecast future events. It’s called curve fitting because you’re molding your model to fit the historical data. You can expend quite a bit of effort fine‐tuning a system to identify all the major trends and turning points in historical data for a particular stock, but that effort isn’t likely to result in future trading profits. In that case, your optimized system is more likely to cause a long string of losses rather than profits.

Testing a long moving average and comparing the results to a short moving average is fine, and so is testing a few points in between a long moving average and a short moving average. As long as you use this exercise to understand why short moving averages work best for short‐term trades and why longer moving averages work better for traders with longer trading horizons, you’ll be fine. Otherwise, you’re probably moving into the realm of curve fitting and becoming frustrated with your actual trading results.

Testing a long moving average and comparing the results to a short moving average is fine, and so is testing a few points in between a long moving average and a short moving average. As long as you use this exercise to understand why short moving averages work best for short‐term trades and why longer moving averages work better for traders with longer trading horizons, you’ll be fine. Otherwise, you’re probably moving into the realm of curve fitting and becoming frustrated with your actual trading results.

Testing with blind simulation

Blind simulation is a method for setting aside enough historical data so you can test your system‐optimization results and avoid the problem of curve fitting. For example, you may test data from 1990 through 1999 and thus exclude data from 2000 through the present. After you’ve developed a system that looks good enough for you to base your trades on, you can then test your system against the data that was excluded. If the system performs as well with the excluded data as it did with the original test data, you may have a system worth trading. If it fails, you obviously need to rethink your system.

Blind simulation is a method for setting aside enough historical data so you can test your system‐optimization results and avoid the problem of curve fitting. For example, you may test data from 1990 through 1999 and thus exclude data from 2000 through the present. After you’ve developed a system that looks good enough for you to base your trades on, you can then test your system against the data that was excluded. If the system performs as well with the excluded data as it did with the original test data, you may have a system worth trading. If it fails, you obviously need to rethink your system.

Another approach is choosing your historical data with extreme care. You can expect trend‐following systems like a moving‐average system to perform well during long, powerful trends. If your stock had a strong run up during the long‐lasting 1990s bull market, that kind of price data can skew your results, magically making any trend‐following system appear profitable. Whether that success actually can be duplicated during a subsequent bull market, however, must first be thoroughly tested.

If the majority of your profits come from a single trade or only a small number of trades, the system probably won’t perform well when you begin trading real money. You may want to address this problem by excluding periods from your test data when your stock was doing exceptionally well or when the results of any trades were significantly more profitable than the average trade. This technique is a valid approach to eliminating the extraordinary results arising from extraordinary situations in your historical data. Using it should give you a better idea of your system’s potential for generating real profits in the future.

If the majority of your profits come from a single trade or only a small number of trades, the system probably won’t perform well when you begin trading real money. You may want to address this problem by excluding periods from your test data when your stock was doing exceptionally well or when the results of any trades were significantly more profitable than the average trade. This technique is a valid approach to eliminating the extraordinary results arising from extraordinary situations in your historical data. Using it should give you a better idea of your system’s potential for generating real profits in the future.

Using breakout trading systems

Similar to moving average–based systems, a breakout system can take many forms. You may already be familiar with the trading‐range breakout system we describe in Chapter 9. To test a different approach, you can define a breakout system as follows:

- Buying at tomorrow’s opening price when today’s closing price is above the highest high price that occurred during the last 20 days

- Selling at tomorrow’s opening price when today’s closing price is below the lowest low that occurred over the last 20 days

These trading rules are loosely based on the rules for Donchian channels (sometimes called price channels), which comprise a breakout system developed by Richard Donchian in the 1950s. Donchian was one of the early developers of trend‐following trading systems.

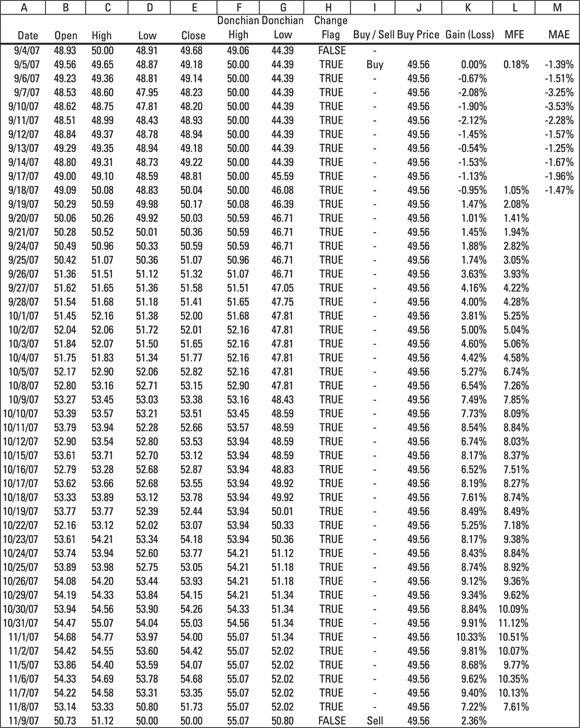

A spreadsheet may be helpful for evaluating this system. You can, in fact, configure this system into a spreadsheet, include buy and sell signals, and perform analyses to determine how well the system performs. You also can use the spreadsheet to dig into the system’s results to find out what works and what doesn’t. Figure 16‐1 shows an example.

Re‐creating the spreadsheet in Figure 16‐1 is straightforward. After downloading the historical price data into a spreadsheet format, all you have to do is encode the formulas into the correct columns. The formulas are described in the nearby sidebar “Creating the Donchian channel spreadsheet.”

If you’re like most traders, the first thing you’ll do is calculate some statistics about the system. For example, you can use spreadsheet functions to calculate the following:

- Total gain or loss for the system

- Average gain (the numerical average)

- Median gain (the middle result)

- Maximum gain for any single trade

- Maximum loss for any single trade

- Standard deviation

You can then look at aggregate results to find out whether the system actually made money. In the case of the Donchian channel breakout system, initial results don’t look promising. The system lost money during the entire test period.

If you’re like most traders, your impulse is to discard the idea and move on to another. But with the Donchian channel breakout system, you need to dig a little further before you do. During the time frame of this test, the system triggered 30 trades, 18 of which were losing trades. However, 13 of those losing trades were profitable at some point during the process, and all the winning trades gave back a large part of the profits before the sell signal was triggered. In fact, many of the profitable trades gave back significantly more than half of the profits before the sell signal.

Figure 16‐1 shows how a single position from the spreadsheet progressed. The entry trade was triggered when the price of QQQQ closed above the September 4 Donchian high. In this simulated trade, the stock was purchased at the September 5 opening price of $49.56 and then sold on November 9, the day after the price of QQQQ closed below the November 8 Donchian low.

If you look through the last three columns, you’ll notice that this simulated trade was profitable but closed well below its most profitable price. If that happens once during simulated trading, you may not need to worry much about it, but if it occurs frequently, you need to think of ways to remedy the problem.

In the Donchian channels system, buy signals apparently work better than sell signals. Therefore, you need to consider different types of stops and sell signals. One simple idea that’s worth testing is stopping out (selling at a predetermined price) of a position if the stock’s low (instead of its close) falls below the Donchian low. Another is to shorten the time frame for the exit signal by using a five‐ or ten‐day Donchian channel. Or you can, for example, use a trailing stop or some completely different criteria to exit these positions.

In the Donchian channels system, buy signals apparently work better than sell signals. Therefore, you need to consider different types of stops and sell signals. One simple idea that’s worth testing is stopping out (selling at a predetermined price) of a position if the stock’s low (instead of its close) falls below the Donchian low. Another is to shorten the time frame for the exit signal by using a five‐ or ten‐day Donchian channel. Or you can, for example, use a trailing stop or some completely different criteria to exit these positions.

In any case, this example gives you ideas about how you can use a spreadsheet to test and analyze any trading system. It also provides you with some suggestions about how you can use this kind of analysis to improve your system’s results.

Accounting for slippage

Slippage is the term traders use to describe the costs of trading, which is made up of two components. The first is the actual transaction or commission cost for executing your trade. The second is more difficult to measure because it’s the sum of the costs of unfavorable fills. If, for example, you’re planning to buy at tomorrow’s opening price based on today’s closing price, those two prices can be much different. An unfavorable fill is a cost of trading and accounted for as slippage.

Most trading system–development packages have a provision for estimating slippage costs when testing your trading ideas using historical data. If you know your transaction costs, enter the exact amounts. Otherwise, estimate the transaction cost. You probably need to overestimate the cost of unfavorable fills because it always seems to end up being worse in actual trading than most traders ever imagine. You may want to start with an estimate of 25 cents per share and adjust it as you gather data on your actual slippage costs.

Most trading system–development packages have a provision for estimating slippage costs when testing your trading ideas using historical data. If you know your transaction costs, enter the exact amounts. Otherwise, estimate the transaction cost. You probably need to overestimate the cost of unfavorable fills because it always seems to end up being worse in actual trading than most traders ever imagine. You may want to start with an estimate of 25 cents per share and adjust it as you gather data on your actual slippage costs.

Keeping a Trading Journal

One of the most impactful, high‐leveraged activities you can adopt is to keep track of all your trading activities in a trading journal. Doing so tracks your experiences in the market, helps you process and carefully analyze them while also keeping them in a permanent place, and then allows you to return to those journal entries at a later time to learn from your past experiences. When kept right, your trading journal becomes an invaluable reference manual that can help you recall both what you’ve done right and what you’ve done wrong in the past, thus keeping you on the right track moving forward and preventing the same mistakes again in the future. A trading journal can help you analyze your trades and trading systems to determine which aspects of trading you do well and which ones you need to work on.

When you develop a trading system, save ideas and test results in your journal. When you enter a position, record everything about the trade. Include your thoughts as you contemplate making the trade. When you have a what‐was‐I‐thinking moment later on, you can find the answer in your journal.

Using a loose‐leaf binder to hold your trading journal is probably best. Print before and after charts for each trade and include them in the journal. Keep detailed notes about each trade and about the system you used to trigger the trade. At a minimum, your notes need to include the following:

Using a loose‐leaf binder to hold your trading journal is probably best. Print before and after charts for each trade and include them in the journal. Keep detailed notes about each trade and about the system you used to trigger the trade. At a minimum, your notes need to include the following:

- Trade date

- Stock symbol

- Number of shares and why you chose that number

- Whether you bought long or sold short

- Which system triggered the entry signal

- Which system triggered the exit signal

- Where you placed your initial stops

- If and why you moved your stops

- What caused you to exit the position and why

- The percentage gain or loss from the trade

- Whether any economic reports or announcements were made around or during the time of the trade

- Your thoughts, hopes, and fears that you had before opening the position and while the position was open

You can also use your journal to keep track of more than just your trading history. Save Internet articles or blogs that influenced your thinking. Cut out and archive the new high and new low lists from the newspaper. Keep a record showing leading and lagging industries. Save sector charts along with your trade records. Whatever information you use to make trading decisions needs to be in your trading journal.

You can improve only the things that you measure. Record statistics about your trades. Include the duration of each trade, the MFE, and the MAE. After you close a trade, write down what you could have done differently. Find out whether you can identify signals that can help you recognize similar situations in future trades.

You can improve only the things that you measure. Record statistics about your trades. Include the duration of each trade, the MFE, and the MAE. After you close a trade, write down what you could have done differently. Find out whether you can identify signals that can help you recognize similar situations in future trades.

Although keeping the journal is important, it’s useful only when you review it regularly. Spend a little time every week or month reviewing all your trades so you can pinpoint consistent mistakes or missed opportunities. Be brutally honest with yourself and use your journal as an opportunity to step back, take a cold, hard look at your trading decisions, and evaluate how you can improve moving forward. Every trader, no matter how experienced, always has room to grow. Your trading journal should become the soil that nurtures that growth.

Although keeping the journal is important, it’s useful only when you review it regularly. Spend a little time every week or month reviewing all your trades so you can pinpoint consistent mistakes or missed opportunities. Be brutally honest with yourself and use your journal as an opportunity to step back, take a cold, hard look at your trading decisions, and evaluate how you can improve moving forward. Every trader, no matter how experienced, always has room to grow. Your trading journal should become the soil that nurtures that growth.

Evaluating Trading Systems for Hire

You’ll see advertisements on the Internet, in trade magazines, and in newspapers for foolproof systems that promise amazing returns. Sometimes you’ll even see claims for systems that regularly return hundreds of percent with little or no risk.

Although some stocks do actually achieve astronomical returns of hundreds and sometimes thousands of percent, those cases are rare. Consider this: A system that offers profits of 100 percent per year supposedly grows $10,000 into $10 million dollars in only ten years. Be skeptical. Experienced traders know that no system consistently returns 100 percent per year.

Consider this: If you created such a system, would you sell it?

When evaluating these systems, the devil is in the details. Advertisements often are unclear about how a system actually works in real‐world trading, and some vendors make claims based on nothing more than the results of system testing based only on simulated trades and historical data. In fact, the system’s author may never have traded the system using real capital.

Constructing a system that shows great profits when simulating trades with historical data is easy. If you designed a trend‐following system and tested it against data during the period 1997–2000, or 2003–2007, you can be fairly certain that the system is going to perform well in simulated testing. But that doesn’t mean you should use it to trade real money.

If a system sounds too good to be true, it probably is. So do your own homework. Find out what works and what doesn’t, and save your hard‐earned trading capital for trading.

If a system sounds too good to be true, it probably is. So do your own homework. Find out what works and what doesn’t, and save your hard‐earned trading capital for trading.

Distinguishing different trading systems

Distinguishing different trading systems Identifying the tools and data required for system development and testing

Identifying the tools and data required for system development and testing Maintaining a trading journal

Maintaining a trading journal Assessing trading systems that you can buy

Assessing trading systems that you can buy As you read through our descriptions of the trading systems, understand that no system generates profits without any losing trades. Put another way, no system works in every situation. Keep that fact firmly in mind when you’re developing and designing your own personal trading system. Your goal is to design a trading system that is useful to you across a large number of stocks and a large number of situations. Believe us when we say that you will run into trouble whenever you try to tailor a trading system to a specific stock. Additionally, try to ensure that your system works across long periods of time and throughout many different market conditions.

As you read through our descriptions of the trading systems, understand that no system generates profits without any losing trades. Put another way, no system works in every situation. Keep that fact firmly in mind when you’re developing and designing your own personal trading system. Your goal is to design a trading system that is useful to you across a large number of stocks and a large number of situations. Believe us when we say that you will run into trouble whenever you try to tailor a trading system to a specific stock. Additionally, try to ensure that your system works across long periods of time and throughout many different market conditions. A discretionary system requires a great deal of discipline, which can cause problems for some traders. This type of system works well for traders who are capable of making good decisions quickly under pressure. But discretionary systems may prove troublesome if you allow your emotions to wreak havoc with your ability to think clearly, act rationally, and make thoughtful trading decisions.

A discretionary system requires a great deal of discipline, which can cause problems for some traders. This type of system works well for traders who are capable of making good decisions quickly under pressure. But discretionary systems may prove troublesome if you allow your emotions to wreak havoc with your ability to think clearly, act rationally, and make thoughtful trading decisions. Another problem with discretionary systems is that they’re difficult to test. This is possibly their greatest drawback. System testing is useful because it helps you understand situations in which an indicator works well and those in which it fails. With a discretionary system, you can test the indicators, but you can’t reliably test your discretion. We talk about testing trading systems in more detail later in this chapter.

Another problem with discretionary systems is that they’re difficult to test. This is possibly their greatest drawback. System testing is useful because it helps you understand situations in which an indicator works well and those in which it fails. With a discretionary system, you can test the indicators, but you can’t reliably test your discretion. We talk about testing trading systems in more detail later in this chapter.