Chapter 25

From Groan to Glee: Passover

In This Chapter

Understanding why Passover is the most celebrated Jewish holiday

Understanding why Passover is the most celebrated Jewish holiday

Creating and personalizing your Passover seder

Creating and personalizing your Passover seder

Experiencing the story of Exodus

Experiencing the story of Exodus

Sampling matzah and gefilte fish

Sampling matzah and gefilte fish

We’ve always found it ironic that Passover is both the most-celebrated Jewish holiday of the year and the holiday voted most likely to elicit a groan. People groan when they consider the dietary requirements. They groan when they think of all the preparations. They even groan when they remember how much they overate during Passover last year.

But the real irony behind the moaning, groaning, and kvetching is that in some ways this is exactly how you’re supposed to feel at this time of year. Don’t get us wrong: Passover isn’t the holiday of complaining, even if that’s the way some Jews tend to celebrate it. Passover is a celebration of spring, of birth and rebirth, of a journey from slavery to freedom, and of taking responsibility for yourself, the community, and the world. However, strangely enough, none of this taking of responsibility gets done without groaning. It was with groaning that the Hebrews expressed the pain of their ancient enslavement in Egypt more than 3,300 years ago. It was with groaning that they called attention to their plight. So groan, already!

Looking at the Reasons behind Passover

On the surface, people celebrate Passover because the Hebrews were redeemed from slavery in Egypt (see Chapter 11). But just as the surface of the ocean belies the deep mysteries beneath the waves, the basic story only hints at the depth of the Passover season.

The Torah states that Jews are to observe Passover for seven days, beginning on the 15th of the Jewish month Nisan (usually in April). You can think of Passover as honoring the renewal of the sun (the first night is always on the first full moon after the Spring Equinox), or a time to step firmly into springtime. You can also think of Passover as celebrating the Jewish people’s “birth certificate” and “Declaration of Independence.” Or you can think of it as memorializing something that God did for the Jews 3,300 years ago.

However, to make any celebration or ritual truly meaningful, you must find a way to make it personal. Even Moses — and later the rabbis of the Talmud — recognized this when they instructed the Jewish people how to celebrate Passover. The key isn’t only to tell the story of the Exodus, or even to compare your life to the story of the Exodus, but to actually personalize the history: feel the feelings and experience the sensations of this journey. In this way, the Jewish people as individuals and as a people move forward. Everything a person does during Passover aids this process.

Edible Do’s and Don’ts

Jews do a lot of thinking about food. And perhaps more than at any other time, Jews think about food during Passover. The first night of Passover always includes a special seder (ritual dinner; see The Seder: As Easy As 1, 2, 3 . . . later in this chapter). Outside of Israel, Jews celebrate a second seder on the second night of Passover. Besides the fact that the Passover seder ritually focuses on food, two commandments during Passover have to do with eating:

You must eat matzah (unleavened bread) as part of the Passover seder.

You must eat matzah (unleavened bread) as part of the Passover seder.

You should eat no leavened foods during the entire week of Passover.

You should eat no leavened foods during the entire week of Passover.

What exactly is unleavened bread? The Talmud (see Chapter 3) says not to eat any wheat, barley, rye, spelt, or oats if they have leavening—and tradition states that these grains leaven if they’re not cooked within 18 minutes of being exposed to water. These five grains (if leavened) are called khametz. Traditional Jews, in order to avoid leaven, use other sets of dishes during Passover, and they ritually cleanse their kitchens.

As if this Torah injunction wasn’t strict enough, Ashkenazi rabbis ruled that kitniot — rice, millet, corn, and legumes such as lentils and beans — were also not to be eaten because of the principle of ma’arat ayin (avoiding even the appearance of violating a commandment). The thinking is that ground rice or corn may be mistaken for flour, or that if you mix kitniot with water and cook it, it may rise like leavened bread.

Note that avoiding kitniot is a custom, not a commandment. Sephardic Jews, for example, eat corn, rice, and legumes during Passover without even a tiny pang of guilt. While we’re both of Ashkenazic descent (see Chapter 1), we follow the Sephardic tradition in this respect. (Vegetarians especially may find it useful to know about this Sephardic tradition.)

Kosher for Passover

Keeping kosher (eating in compliance with Jewish dietary law; see Chapter 4) takes on a whole new level of awareness during Passover, especially if you follow the Ashkenazi tradition. For example, you may notice a “Kosher for Passover” version of Pepsi. What’s the difference? Real sugar is expensive, so almost all sodas are made with corn syrup — in other words, kitniot! Kosher for Passover Pepsi uses real sugar, just like soda was made in the good ol’ days.

If you look hard enough, each spring you can find many kinds of “Kosher for Passover” products, such as:

Coffee (which may ordinarily contain grain additives or have come in contact with khametz-derived ethyl acetate as part of a decaffeination process)

Coffee (which may ordinarily contain grain additives or have come in contact with khametz-derived ethyl acetate as part of a decaffeination process)

Orange juice (which otherwise may have been filtered with bran)

Orange juice (which otherwise may have been filtered with bran)

Butter (which may contain cultures or color agents derived from khametz)

Butter (which may contain cultures or color agents derived from khametz)

Toothpaste (which commonly contains cornstarch)

Toothpaste (which commonly contains cornstarch)

Similarly, most alcoholic beverages (except wine and brandy) are made with grains that are khametz. Vinegar (except for pure apple cider vinegar) is often made from khametz. Orthodox Jews simply won’t eat any packaged foods during this week unless they are labeled Kosher for Passover.

The symbolism of Passover restrictions

In the Bible, God doesn’t just say “Hey, try some matzah this week.” No, God makes a really big deal about not eating leavened bread. Why? What’s so dang important about avoiding leavened bread?

The Bible says “So you shall tell your children on that day, saying: We eat unleavened bread because of what the Eternal One did for me when I came out from Egypt.” In our opinion, this is a perfectly reasonable explanation to tell children. But if you’re like us, this answer may not satisfy your own questions regarding this relatively weird practice.

As far as food goes, both matzah and khametz ain’t nothin’ special. However, as symbols, they both take on great meaning. And, as you can see elsewhere in this chapter, Passover is all about using symbols as catalysts for change.

Khametz is a symbol of the ego. Unlike some forms of Buddhism, Judaism takes no issue with you having an ego — it even encourages a strong sense of individual identity. However, the tradition clearly states that the ego, if allowed to grow and swell for too long, makes you arrogant, sinful, and just plain icky to be around. So Judaism has developed a remedy: matzah (bread that has not leavened or swelled).

Once a year, Jews take a week to deflate themselves, to rid the body and soul of ego puffery, and to remember that none of us is better than the lowest slave. Also, eating only unleavened bread really gets you in touch with what’s important. Remember, Judaism can be a practice like meditation or working out at the gym. If every time you drive by a sandwich or burger shop during Passover you think to yourself, “I have a choice between giving in to my desire or eating more simply this week,” you soon find yourself becoming more aware of who you are, who you aren’t, and who you truly want to be. In fact, the Zohar (one of the key books of Jewish mysticism; see Chapter 5) actually calls matzah a medicine when eaten during Passover.

If you do find yourself chomping on the sandwich or with the spoonful of cereal in your mouth, don’t kick yourself too hard — it’s called a “practice” because almost no one gets it right the first time around!

First Things First: Preparing for Passover

Passover requires more preparation than any other Jewish celebration — not just because of the ritual foods, but because Jews need to clean their houses carefully.

Cleaning out the khametz

Judaism has made many contributions to Western society: monotheism, written law, a system of social morality . . . and spring cleaning. We don’t know if giving your house a thorough cleaning is really a Jewish thing or not, but that’s exactly what traditionally happens during the two weeks before Passover begins.

Not only are Jews not supposed to eat any khametz during Passover, they’re not even supposed to come in contact with any, own any, or benefit from the sale of any khametz during the holiday. So beginning on the first of Nisan (the Rosh Chodesh or new moon of that month), traditional Jews begin to collect and clean away anything in their house that may be considered khametz.

The Ashkenazi tradition of avoiding kitniot says you shouldn’t eat those foods (corn, rice, legumes, and so on), but unlike khametz, Jews can still benefit from and possess kitniot during Passover.

You find khametz in products other than food, too, so some traditional Jews often take the injunction further and remove all cosmetics, inks, glues, and medicines that may contain khametz or chemicals derived from khametz.

In Jewish households around the world during the week before Passover, family members scrub floors and sinks, purify pots and flatware by putting them in boiling water, and attempt to vacuum up every last speck of dust, just in case it’s khametz. Traditional Jews put away their regular dishes and replace them with special dishes that they only used at Passover time.

Many Jews stage an elaborate, last-minute hunt for khametz the night before Passover begins. Best when shared as a family event, the hunt generally takes place with a candle (or flashlight), a feather (or a small palm branch), and a paper bag. Use the feather to sweep every speck of potential khametz you find into a paper bag. (Many parents strategically place little piles of cereal around the house so that their children can find them and brush them up.) The next morning, the whole family ritually burns the paper bag and all the offending particles.

Like many symbols of Passover, this entire process is meant to start people (especially the children) asking questions, such as “Why are we cleaning?” “Why are we using a candle and feather?”

Giving to charity at Passover time

You may have noticed that every Jewish holiday is a time for tzedakah, for giving to charity, which is a key aspect of Judaism. In the weeks before Passover, Jews customarily give ma’ot khittim (wheat money) to the less fortunate members of the community so they can afford to buy matzah, which is usually much more expensive than khametz. At Ted’s congregational seder, people bring the foods that they’re not eating during Passover week, to provide needed sustenance for those non-Jews who are in need.

The Seder: As Easy as 1, 2, 3 . . .

The Passover seder is the heart of the holiday. Seder is Hebrew for “order” and refers to the 15-step ritual known as the Passover dinner.

Although some Jews have just a single seder dinner each year (on the first night of Passover), many others have two sedarim (the plural of seder) — often the first night with family and the second night with their congregation or some other group. We have also heard of Jews celebrating the first night indoors and the second night outdoors, perhaps after a hike with friends.

Clearly, many Jews now celebrate the Passover seder as simply a big dinner party with a few fun (or annoying) prayers and songs added on. But you can make the seder much more spiritually fulfilling than that, depending on how much awareness you bring to the table. The entire seder is designed to use food to symbolize ideas.

The haggadah: Seder’s little instruction booklet

The seder is based on the haggadah, a book of instructions, prayers, blessings, and stories that lays out the proper order for the ritual. Haggadah means “the telling,” referring to one of the most important aspects of the seder: the recitation of the Exodus story. The basic text of the traditional haggadah (the one used by most Orthodox families) is almost identical to that used in the eleventh century (though some songs and commentary have been added). However, in the 1960s and 1970s, many different versions began to appear, and now there are literally hundreds of haggadot (the plural of haggadah) available, each laying out the same basic ritual, but each with a slightly different spin.

Some haggadot provide special material geared toward children, women’s issues, the holocaust, vegetarian’s needs, and those in recovery programs. Picking a haggadah that speaks to you and the people at your seder is one key to a successful seder.

Look who’s coming to dinner

Perhaps even more important than choosing which haggadah to use is deciding who to invite to the seder. Everyone who attends a seder must be willing to participate in the prayers, songs, and readings. If you’re performing a family seder, you obviously can’t pick and choose the guests, but you can help prepare each family member for what you expect them to do. If you’re inviting friends over, make sure they’re friends who like participating (and it wouldn’t hurt to show them this chapter, too). Some of the saddest seders are those where a few people end up “performing” for the rest of the crowd.

The prepared table

Before we get to the steps of the seder itself, we want to explain the various ritual foods and other items that you see on almost every seder table. Nothing on the table is selected randomly; each item has its purpose and, often, its specific place on the table or seder plate.

At a Passover seder, you’ll find the following traditional items on the table:

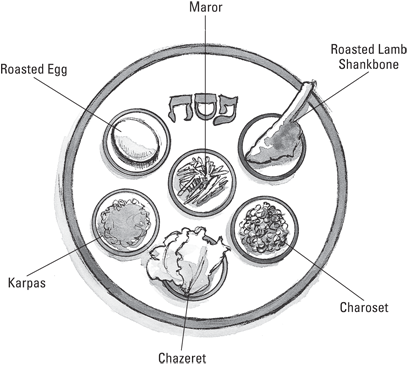

Seder plate: The seder plate (usually one per table) holds at least six of the ritual items that are talked about during the seder: the shankbone, karpas, chazeret, charoset, maror, and egg (see Figure 25-1). While the booming seder plate industry would like you to buy a beautiful plate made of ceramic, glass, or silver (and honestly, some really amazing plates are available), you can also use any plate. If you have kids, get them involved by decorating a paper plate with pictures of the events or things that the seder foods symbolize.

Seder plate: The seder plate (usually one per table) holds at least six of the ritual items that are talked about during the seder: the shankbone, karpas, chazeret, charoset, maror, and egg (see Figure 25-1). While the booming seder plate industry would like you to buy a beautiful plate made of ceramic, glass, or silver (and honestly, some really amazing plates are available), you can also use any plate. If you have kids, get them involved by decorating a paper plate with pictures of the events or things that the seder foods symbolize.

Roasted egg: The roasted egg (baytsah) is a symbol in many different cultures, usually signifying springtime and renewal. Here it stands in place of one of the sacrificial offerings that was performed in the days of the Second Temple (see Chapter 13). Another popular interpretation is that the egg is like the Jewish people: the hotter you make it for them, the tougher they get. Don’t worry: you don’t eat the egg during the meal; the shell just needs to look really roasted.

Roasted egg: The roasted egg (baytsah) is a symbol in many different cultures, usually signifying springtime and renewal. Here it stands in place of one of the sacrificial offerings that was performed in the days of the Second Temple (see Chapter 13). Another popular interpretation is that the egg is like the Jewish people: the hotter you make it for them, the tougher they get. Don’t worry: you don’t eat the egg during the meal; the shell just needs to look really roasted.

If you’re going to put an egg in the broiler, hardboil it first. Some people swear that using a blowtorch on the shell provides the best “roasted” look.

If you’re going to put an egg in the broiler, hardboil it first. Some people swear that using a blowtorch on the shell provides the best “roasted” look.

Figure 25-1: The ritual seder plate.

Roasted lamb shankbone: One of the most striking symbols of Passover is the roasted lamb shankbone (called zeroah), which commemorates the paschal (lamb) sacrifice made the night the ancient Hebrews fled Egypt. Some people say that it symbolizes the outstretched arm of God (the Hebrew word zeroah can mean “arm”). You can usually get a shankbone (you can also use a chicken neck) from any butcher; roast it in the oven with the egg until they both appear somewhat burnt-looking.

Roasted lamb shankbone: One of the most striking symbols of Passover is the roasted lamb shankbone (called zeroah), which commemorates the paschal (lamb) sacrifice made the night the ancient Hebrews fled Egypt. Some people say that it symbolizes the outstretched arm of God (the Hebrew word zeroah can mean “arm”). You can usually get a shankbone (you can also use a chicken neck) from any butcher; roast it in the oven with the egg until they both appear somewhat burnt-looking.

If you don’t like the idea of a bone sitting on your table, you may consider using a roasted beet instead. (That’s what vegetarians usually do.) This isn’t a new idea; the great Biblical and Talmudic commentator Rashi suggested using a beet back in the eleventh century.

If you don’t like the idea of a bone sitting on your table, you may consider using a roasted beet instead. (That’s what vegetarians usually do.) This isn’t a new idea; the great Biblical and Talmudic commentator Rashi suggested using a beet back in the eleventh century.

Maror (“bitter herb”): When we think “Passover,” we think “horseradish,” the bitter herb most commonly used in the seder. Any bitter herb will work, though. Bitter herbs bring tears to the eyes and recall the bitterness of slavery. The seder refers to the slavery in Egypt, but people are called to look at their own bitter enslavements — whether addictions or habits. If you can get your hands on a real horseradish root (make sure it’s at least as firm as a parsnip or fresh carrot), cut it in thin slices or grate it up. Horseradish in a jar is okay, too, although it lacks the bite of the freshly grated root.

Maror (“bitter herb”): When we think “Passover,” we think “horseradish,” the bitter herb most commonly used in the seder. Any bitter herb will work, though. Bitter herbs bring tears to the eyes and recall the bitterness of slavery. The seder refers to the slavery in Egypt, but people are called to look at their own bitter enslavements — whether addictions or habits. If you can get your hands on a real horseradish root (make sure it’s at least as firm as a parsnip or fresh carrot), cut it in thin slices or grate it up. Horseradish in a jar is okay, too, although it lacks the bite of the freshly grated root.

Charoset: Nothing is farther from maror than charoset (pronounced “kha-roh-set”), that sweet salad of apples, nuts, wine, and cinnamon that represents the mortar used by the Hebrew slaves to make bricks. Why would a reminder of slavery be so sweet? Because as much as people like to deny it, there is a sweetness to the security and dependability of any slavery, perhaps especially those enslavements that people create for themselves. Jewish cookbooks offer many recipes for charoset (see the recipes for Ashkenazi and Sephardi charoset later in this chapter); we particularly like Sephardic recipes, which are like a chutney of dates, raisins, almonds, and oranges.

Charoset: Nothing is farther from maror than charoset (pronounced “kha-roh-set”), that sweet salad of apples, nuts, wine, and cinnamon that represents the mortar used by the Hebrew slaves to make bricks. Why would a reminder of slavery be so sweet? Because as much as people like to deny it, there is a sweetness to the security and dependability of any slavery, perhaps especially those enslavements that people create for themselves. Jewish cookbooks offer many recipes for charoset (see the recipes for Ashkenazi and Sephardi charoset later in this chapter); we particularly like Sephardic recipes, which are like a chutney of dates, raisins, almonds, and oranges.

Karpas: Karpas is a green vegetable, usually parsley (though any spring green will do; some folks use celery sticks). For some people karpas symbolizes the freshness of spring; others say that eating it makes them feel like nobility or aristocracy. Some families still use boiled potatoes for karpas, continuing a tradition from Eastern Europe, where it was difficult to obtain fresh green vegetables.

Karpas: Karpas is a green vegetable, usually parsley (though any spring green will do; some folks use celery sticks). For some people karpas symbolizes the freshness of spring; others say that eating it makes them feel like nobility or aristocracy. Some families still use boiled potatoes for karpas, continuing a tradition from Eastern Europe, where it was difficult to obtain fresh green vegetables.

Chazeret: The chazeret (literally, “lettuce,” pronounced “khah-zer-et”) is a second bitter herb, most often romaine lettuce, but people also use the leafy greens of a horseradish or carrot plant. Chazeret has the same symbolism as maror.

Chazeret: The chazeret (literally, “lettuce,” pronounced “khah-zer-et”) is a second bitter herb, most often romaine lettuce, but people also use the leafy greens of a horseradish or carrot plant. Chazeret has the same symbolism as maror.

Salt water: Salt water symbolizes the tears and sweat of enslavement, though paradoxically, it’s also a symbol for purity, springtime, and the sea, the mother of all life. Often a single bowl of salt water sits on the table, and people dip their karpas into the water during the seder. Some traditions begin the actual seder meal with each person eating a hardboiled egg (not the roasted egg!) dipped in the bowl of salt water.

Salt water: Salt water symbolizes the tears and sweat of enslavement, though paradoxically, it’s also a symbol for purity, springtime, and the sea, the mother of all life. Often a single bowl of salt water sits on the table, and people dip their karpas into the water during the seder. Some traditions begin the actual seder meal with each person eating a hardboiled egg (not the roasted egg!) dipped in the bowl of salt water.

Matzah: Perhaps the most important symbol on the seder table is a plate that has a stack of three pieces of matzah (unleavened bread) on it. The matzot (that’s plural for matzah) are typically covered with a cloth. (Since three matzot probably won’t feed the table, make sure you have extra elsewhere on the table.) Tradition offers all kinds of interpretations for the three matzot. Some say they represent the Kohen class (the Jewish priests in ancient times), the Levis (who supported the priests), and the Israelites (the rest of the Jews). We actually don’t care what symbolism you attribute to this trinity, as long as you’re thinking about it. During the struggles of Soviet Jewry, Jews added a fourth piece of matzah to the seder plate to symbolize the struggles of Jews who were not yet free enough to celebrate the Passover. Today, some families still use that fourth matzah as a way of remembering all people who are not yet free to celebrate as they may wish.

Matzah: Perhaps the most important symbol on the seder table is a plate that has a stack of three pieces of matzah (unleavened bread) on it. The matzot (that’s plural for matzah) are typically covered with a cloth. (Since three matzot probably won’t feed the table, make sure you have extra elsewhere on the table.) Tradition offers all kinds of interpretations for the three matzot. Some say they represent the Kohen class (the Jewish priests in ancient times), the Levis (who supported the priests), and the Israelites (the rest of the Jews). We actually don’t care what symbolism you attribute to this trinity, as long as you’re thinking about it. During the struggles of Soviet Jewry, Jews added a fourth piece of matzah to the seder plate to symbolize the struggles of Jews who were not yet free enough to celebrate the Passover. Today, some families still use that fourth matzah as a way of remembering all people who are not yet free to celebrate as they may wish.

Wine cups and wine (or grape juice): Everyone at the seder has a cup or glass from which they drink four cups of wine. Now, before you get any wild ideas about getting trashed, remember that these are usually very small cups of wine. And if you prefer not to drink wine, you can drink grape juice instead. Traditionally, the four cups represent the four biblical promises of redemption: “I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians, and I will rid you from their slavery, and I will redeem you with an outstretched arm, and with great judgments. And I will take you to me for a people . . .” Others say the four cups represent the four letters in the unspeakable Name of God (see Chapter 2). Besides the wine cups at each place setting, you need one additional cup, called the Cup of Elijah, which we discuss later in this chapter.

Wine cups and wine (or grape juice): Everyone at the seder has a cup or glass from which they drink four cups of wine. Now, before you get any wild ideas about getting trashed, remember that these are usually very small cups of wine. And if you prefer not to drink wine, you can drink grape juice instead. Traditionally, the four cups represent the four biblical promises of redemption: “I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians, and I will rid you from their slavery, and I will redeem you with an outstretched arm, and with great judgments. And I will take you to me for a people . . .” Others say the four cups represent the four letters in the unspeakable Name of God (see Chapter 2). Besides the wine cups at each place setting, you need one additional cup, called the Cup of Elijah, which we discuss later in this chapter.

Participants don’t eat all of the symbols, such as the roasted lamb shankbone and the roasted egg. However, when it comes time to eat the karpas, the charoset, and the other symbols, different families have different traditions. Some eat the symbols from the seder plate; others give each person their own mini-seder plate to eat from; at larger events, hosts may serve the items family style, passing large bowls around so that people can serve themselves.

Ashkenazi Charoset

Prep time: 15 minutes • Yield: 3 to 4 cups

Ingredients

3 large, firm apples (sweet, tart, or both)

Juice of 1 fresh lemon or 1 teaspoon of reconstituted lemon juice

1⁄2 pound coarsely-chopped nuts (walnuts, almonds, pecans, or mix-and-match)

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

Sweet red wine or grape juice to desired consistency

1 teaspoon sugar or 2 to 3 teaspoons honey (optional)

Directions

1. Core and dice the apples. (Some people peel the apples first, but we don’t think that’s necessary.) If you use a food processor, use the pulse feature to coarsely chop the apples.

2. Mix the apples well with the lemon juice, and then fold in the nuts and cinnamon. Add enough wine or grape juice to achieve the desired consistency, usually about 1⁄3 cup. Taste to see if you want to add some sugar or honey for extra sweetness.

Per serving: Calories 322 (From Fat 225); Fat 25g (Saturated 2g); Cholesterol 0mg; Sodium 2mg; Carbohydrate 23g (Dietary Fiber 6g); Protein 6g.

Tip: You can make the charoset up to three days in advance and keep it in the refrigerator.

Note: Charoset is a mortar-like mixture that needs be able to sit on a piece of matzah and not fall off before making it to your mouth. So as you add the liquid, don’t add too much.

Sephardi Charoset

Prep time: 10 minutes • Yield: 3 to 4 cups

Ingredients

1 cup pitted dates (1⁄4 pound)

1 cup raisins

1 apple, cored and cut into chunks

1⁄2 cup walnuts

1 tablespoon grated orange peel

1⁄4 cup orange juice

1⁄4 teaspoon cinnamon

Dash nutmeg or cloves

Directions

1. Combine dates, raisins, apple, and walnuts in a food processor and chop them until the mixture is in small pieces but not minced. Transfer the mixture to a medium bowl.

2. To the fruit mix add the orange peel, orange juice, cinnamon, and nutmeg/cloves. Cover the bowl and chill overnight (it will get a little thicker as it chills). Yields about 3 cups.

Per serving: Calories 249 (From Fat 62); Fat 7g (Saturated 1g); Cholesterol 0mg; Sodium 5mg; Carbohydrate 50g (Dietary Fiber 5g); Protein 3g.

Tip: Try serving this Sephardi version of charoset at your next seder (or even earlier). It helps those of us who have an Eastern European heritage to more fully appreciate some of the tastes contributed by other segments of the greater Jewish cultural experience.

Anecdote: This is the basic recipe that Ruth Neuwald Falcon (Ted’s wife) got from her mother, who loved recipes from exotic places. In the Falcon household, Ruth prepares both Sephardi and Ashkenazi charosets each year for all the sedarim they attend.

Steps of the seder

You’ve set the table, prepared the foods, distributed the haggadot . . . it’s finally time for the seder to begin. Each seder needs a leader, someone to orchestrate the proceedings and read key parts of the haggadah. In traditional homes, the leader may wear a white kittel (robe), which the individual wears only at special times in his or her life, such as during the seder, Yom Kippur, his (or her) wedding, and burial; wearing the kittel helps create the sense that this is a sacred time.

The 15 steps of the seder (remember that seder means “order”) can be broken down into four sections:

A series of preparatory prayers and rituals, often beginning with a special song listing the 15 steps

A series of preparatory prayers and rituals, often beginning with a special song listing the 15 steps

The telling of the story

The telling of the story

The dinner

The dinner

The post-meal prayers and songs

The post-meal prayers and songs

The first activity of the seder — lighting candles — isn’t included in the 15 steps because this ritual always precedes the evening celebration of any Jewish festival. After you light the candles, the seder proceeds as follows. (Please note that this book is in no way a replacement for a real haggadah, which would go into greater detail and provide the appropriate prayers.)

Step 1: Kadesh (sanctification of the day)

Fill your cup with the first glass of wine or grape juice, lift the cup, say the Kiddush (sanctification over the fruit of the vine and over the special energies of the holiday), and drink, leaning to the left. Tradition says to fill the cup to the brim, but it also says that you shouldn’t get drunk, so you don’t have to drink the whole glass (and the cup may be small). At Purim (see Chapter 24), people drink until they get blurry; but at the seder, people drink to sharpen, to remember, and to transcend.

Step 2: Urkhatz (handwashing with no blessing)

The second step is a ritual ablution — a spiritual cleansing by pouring water over the hands. The water should be warm enough to make the washing pleasant. Traditionally, you pour water from a pitcher over your right and then over your left hand. You can then dry your hands on a towel. In some homes, and in a large congregation, the leader often acts as proxy, performing the urkhatz for everyone in attendance.

Step 3: Karpas (eating the green vegetable)

The first bite of food people get is the karpas, the green vegetable, symbol of spring and renewal, which they dip in salt water (purifying tears) before eating. Anyone who forgot to eat a snack before arriving at the seder will be sorely tempted to continue eating the karpas (and any other vegetables lying around) as hors d’oeuvres before the meal. The wise arrangers make sure there is plenty available. Go for it!

Step 4: Yakhatz (breaking the matzah)

Now the seder leader picks up the middle matzah from the matzah plate and breaks it in half. The leader puts the smaller half of matzah back in between the other two pieces of matzah, but the larger half is reserved as the afikomen (“dessert”), which is eaten at the end of the meal. In some families, the afikomen is taken away and hidden somewhere in the house, and near the end of the seder the kids are allowed to go looking for it (see Step 12). Another common practice is to place the afikomen near the leader, from whom the kids must steal it during the seder without the leader noticing. In some Sephardic families, each person places a broken afikomen matzah on their shoulder, symbolizing the quick exodus from Egypt.

Step 5: Maggid (telling the story)

Usually the longest of the 15 seder steps, the Maggid is the telling of the Exodus narrative. At this point the youngest child at the table asks the four questions (every haggadah lists them). Actually, any person can read the questions, or everyone can read them together. The four questions all revolve around the basic question, “Why is this night different than all other nights?” (Mah nishtanah halailah hazeh mikol haleilot?)

The rest of the Maggid answers this question with the story of the Hebrews’ exodus from Egypt, some Torah study, and a discussion of the description of the four types of children: the wise child, the wicked child, the simple child, and the child who doesn’t know enough to ask a question (see the Introduction). Many people look around the table to find a good example of each child, but we find it more appropriate to look inside, to find the parts of ourselves that fit each of these descriptions.

Finally, the second cup of wine is poured, but don’t drink it yet! Traditionally, participants dip a finger into the wine to transfer ten drops of wine to their plate, one drop for each of the ten plagues in Egypt. After singing songs praising God, pointing out the various items on the seder table yet again, and reciting the blessing over the wine, you can drink the second cup. By this time, you usually need it!

Step 6: Rakhtzah (handwashing with a blessing)

It’s time to wash your hands again, but this time you do say the blessing (see Appendix B). Note that it’s customary not to speak at all between washing your hands and saying the blessings over the matzah. You can use this time for reflection on the sanctification and purification that you’re undergoing.

Step 7: Motzi (blessing before eating matzah)

Raise the matzah (unleavened bread) and recite two blessings over the bread: the regular motzi blessing (see Appendix B) and one specifically mentioning the mitzvah (Jewish commandment) of eating matzah at Passover.

Step 8: Matzah (eating the matzah)

Blessings said, everyone breaks off a piece of matzah and eats it.

Step 9: Maror (eating the bitter herb)

Ironically, just as your stomach is starting to growl, you get to eat maror, the bitter herbs. Whether you eat a fresh slice of horseradish (which promises to bring tears to your eyes) or a leaf of romaine lettuce (which is pretty wimpy, in our humble opinion), you should be thinking of the bitterness of slavery. Traditionally, you should dip the maror in the charoset (the apple-nut-wine-cinnamon salad) to taste a small amount of sweetness along with the pain.

Step 10: Korekh (the Hillel sandwich)

While the English Earl of Sandwich is generally credited for inventing the snack of his namesake, Hillel (see Chapter 28) may have originated it two thousand years ago by combining matzah, a slice of paschal lamb, and a bitter herb. Jews no longer sacrifice and eat the lamb, so the Passover sandwich is only matzah, charoset, and a bitter herb now (many people use the chazeret [lettuce] instead of horseradish).

Step 11: Shulkhan Orekh (eating the meal)

After the korekh, the real meal commences, usually beginning with a hard-boiled egg dipped in salt water and quickly progressing to gefilte fish with beet-infused or regular horseradish, matzah ball soup, chopped liver, and as much other food as you can stuff down your gullet. Some of this food may be new to you; for example, gefilte fish is sort of a fish cake that looks scary if you didn’t grow up with it — but try it anyway (it’s usually a little sweet and goes great with the horseradish). Even though you drink four ceremonial glasses of wine during Passover, you can have some more during dinner, too.

Step 12: Tzafun (eating the afikomen)

Whether or not your host serves dessert after dinner, the last food that is officially eaten at the seder is a piece of the afikomen matzah (see Step 4), which symbolizes the Pesach sacrifice. If children have hidden or stolen the afikomen, they must return it to the leader by the end of the seder. Some families reward the children who find the afikomen, others reward all the children, and some actually bargain with the children to get the afikomen back. You can’t conclude the seder without the afikomen (and tradition says that the seder must end before midnight), but the children are usually pretty tired at this point, so both sides have good bargaining positions. Many folks don’t actually eat the afikomen itself; any taste of matzah will do once the afikomen has been returned.

The afikomen also represents the part of the self or soul that is lost or given up in enslavement. The seder represents the journey from enslavement to freedom, and at Tzafun, people reclaim the pieces of self that were missing.

Step 13: Barekh (blessing after eating)

Jewish meals traditionally conclude with a blessing, and this meal is no different. At this point, however, the meal may be over, but the seder is not. The third cup of wine celebrating the meal is poured and, after a blessing is recited, everyone drinks it. Now, a curious tradition occurs: A cup of wine is poured in honor of the prophet Elijah, and a door is opened to allow Elijah in. Many folks think the cup is for Elijah. Actually, the extra cup stems from a rabbinic debate over whether we should drink four or five cups of wine during the seder; the compromise was to drink four (the fourth is drunk in Step 14), pour a fifth, and wait until Elijah comes to tell us which is correct.

An alternative custom invites each person to pour a little of their own wine to fill Elijah’s cup, symbolizing each person’s own responsibility for bringing about redemption.

Step 14: Hallel (songs of praise)

After closing the door, the final seder ritual includes singing special songs of praise to God, and then filling, blessing, and drinking the fourth cup of wine.

Step 15: Nirtzah (conclusion)

The prescribed rituals and actions end at the 14th step, but like the Havdalah ceremony after Shabbat (see Chapter 18), Nirtzah celebrates a conclusion. The most common prayer at the end is simply L’shana haba-a bi-Y’rushalayim, meaning “Next year in Jerusalem!” Then, depending on the hour and the energy level of the participants, you may find yourself singing more songs and possibly even dancing! Some families make a tradition of reading aloud the Song of Songs from the Bible at the end of the seder, though be prepared for sleepy groans if you suggest it.

The haggadah is not simply a script to follow, but rather a foundation on which you can build a wonderfully creative seder. It’s worth repeating: We believe that if you’re not having fun, you’re just not doing it right.

New traditions: Miriam’s Cup

One of the most popular new additions to the Passover seder is Kos Miryam (Miriam’s Cup), which sits on the seder table next to Elijah’s Cup. This cup is filled with water rather than wine, honoring the Talmudic story of Miriam’s Well, which brought life-giving water as the Israelite tribes traveled through the desert, just as the prophetess Miriam (Moses’ sister) soothed and nurtured the Children of Israel during the journey. Miriam’s Cup honors the motherly spirit of God that works through us all, and it honors all the women in our history who have nurtured and healed our people and us personally.

Like many aspects of the seder, Jews play out Miriam’s Cup in a wide variety of ways. Often, after drinking the second glass of wine, the leader invites each person (or sometimes only the women) at the table to pour a little water from his or her cup into the empty goblet. Then, the leader may raise a tambourine and lead the participants in a joyous song. (Any excuse for another joyous song!) This is also a good time to share stories of women who have been important in history and in our own lives.

A Time to Think about Freedom

Every year, it seems, we hear at least one person ask the same question: “Why did God let the Jews be enslaved in the first place?” Although this is a great question, it sort of misses the point. Instead of framing the issue as God letting people do things or not; Judaism teaches that people always have free will (see Chapter 2). In this case, Jacob’s family chose to enter Egypt because it seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

Ironically, people’s problems almost always begin as a solution to an earlier problem, and what at one time seems like the path to freedom often ends up becoming the next “stuck” place. (Remember that the Hebrew word for Egypt is Mitzrayim, which means “from [out of] narrow places.”) Think about the really important growth opportunities you’ve had. Haven’t they all come by overcoming a challenge?

Because we learn and evolve best when we’re stuck and have to choose to move forward, our enslavements — however minor or overwhelming — offer us precious opportunities for awakening and growing beyond old patterns and beliefs.

Let Passover be a time to think about freedom and independence. If you do nothing else for Passover this year, at least find a friend and discuss these ideas.

We who lived in the concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They might have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

We who lived in the concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They might have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

— Victor Frankl

It’s all about choice

Everyone loves the freedom to do stuff. We want the freedom to go places, to see and do what we want, and the freedom to say or believe what we want. The “freedom to” is obviously extremely important, but some say the “freedom from” is even more precious. As Dr. Avram Davis writes, “To be free from anger, free from hatred, free from the chains that bind the heart . . . This is what it means to be free ‘from’ mitzrayim, from the narrow places.”

“Freedom from” is fundamentally about the ability to make choices. If every time you visit your parents you turn into a 14-year-old kid inside, you’re not free. If you just “have” to have that newest, hottest gadget as soon as it hits the market, you’re not free. You may be free to do anything you want, but if you’re a slave to the television, or the weather, or the stock market, or getting your way, you’re not free.

Unfortunately, it’s really hard to get out of our enslavements. Jewish tradition notes that fewer than half of the Hebrews left Egypt after the Pharoah released them. The rest of them stayed because they preferred the familiar routine of slavery to the unknown challenges of the desert. In fact, sometimes we wonder if the ten plagues wrought on Egypt were actually meant as a way to get the remaining Jews to leave, to give them the courage and the trust they so sorely lacked in the state of enslavement.

So, perhaps another interpretation of Passover is celebrating the ability to “pass over,” to skip one thing and choose another. After all, that people were made in the image of God doesn’t mean that they look like God — it means that they’re part of a Greater Awareness, from which they derive their free will. Humans have the freedom to discriminate between right and wrong, and to learn the difference between the spiritual and the mundane. We have the freedom to discover and to choose our paths.

Dayenu: So much gratitude

David’s favorite part of the Passover seder is singing the song called Dayenu, which means “it is enough” (this usually happens during the telling of the Passover story). Besides the catchy tune and raucous beat, this song captures two other deeply important aspects of this holiday: humility and gratitude.

In short, the song says, “If God just took us out of Egypt, that would have been enough. If God had just given us Shabbat, that would have been enough. If God had just given us Torah, that would have been enough,” and so on. The Jews see Dayenu as a call to be grateful for where you are — wherever you are — knowing that it’s where you’re supposed to be. The song is also a call for humility, balance, and moderation, for not overdoing, overworking, overeating, or even over-celebrating.

Dayenu doesn’t mean you should rest on your laurels. Far from it! Dayenu means you must appreciate where you are and what you’ve accomplished. It also means you need to appreciate others. Each time the Bible repeats the refrain, “Remember that you were a slave in Egypt,” think of it as a call to remember humility, to be generous to strangers, and to treat all others as you would wish to be treated.

It’s Not Over till It’s Omer

The seder is over and you’re ready for life to get back to normal, right? Well, don’t get too excited yet, because it’s time for the 49-day period called the Counting of the Omer (or just the Omer). Many nontraditional Jews tend to ignore the Omer entirely, but it can be a fascinating time for self-reflection and spiritual self-improvement. This period also includes several other specific holidays that we touch on later in this section.

Agricultural roots

The Counting of the Omer, like many holidays, harkens back to the agricultural cycle. In biblical times, the Israelites honored the spring harvest by waving a sheaf of barley (called an omer) on what Jews today consider the second night of Passover. Then they counted the next 49 days, until the wheat harvest on the fiftieth day (called Shavuot, see Chapter 26).

Over the centuries, as the agricultural calendar became less relevant to the Jews, the Omer took on more spiritual significance. Although no one knows exactly how long it took the newly freed Israelites to hike from Egypt to Mount Sinai (where they received the Torah; see Chapter 3), tradition dictates that the revelation occurred on the fiftieth day. With this in mind, the omer period reflects the nature of the journey from enslavement (symbolized by Mitzrayim) to freedom and revelation.

(Curiously, the Christian tradition mirrors this seven-week journey: Pentecost — the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles — occurs seven weeks, or 49 days, after Easter. Some say Jesus’ “last supper” was actually a Passover seder, so it’s not surprising that Pentecost occurs at almost exactly the same time as Shavuot.)

Usually, the first 33 days of the Omer period are a time of semi-mourning, meaning that traditionally no weddings or joyous celebrations take place during this time. Traditional Jews also stop playing musical instruments or even getting their hair cut during this period. Generally, the only exceptions are the two new moons that occur during the Omer and Lag B’Omer (the 33rd day of the Omer, described later in this section).

Because the Bible specifically says to count the days of the Omer, each evening, beginning on the second night of Passover, Jews are urged to say the following blessing:

Barukh Atah Adonai, Elohenu Melekh ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitz’votav v’tzivanu ahl s’firat ha-Omer.

Blessed are You, Holy One our God, Universal Ruling Presence, Who sanctifies us with mitzvot [paths of holiness] and gives us this mitzvah of counting the days of Omer.

. . . and then read the following line, filling in the blanks with the appropriate numbers (you can leave out the part in brackets during the first week):

Today is the ___ day [comprising ___ weeks and ___ days] of the Omer.

The magical, mystical seven

The heart of Jewish mystical teaching is called kabbalah, which literally means “that which is received.” By the sixteenth century, the mystics began associating the kabbalistic Tree of Life (see Chapter 5) with the seven weeks of the Omer-counting, so that they could more profoundly honor the specific spiritual energies of each step of the journey.

Rabbis associated the 49-day period with the seven lower sefirot, or levels, on the Tree of Life — one for each week. They also associated each day of the week with one of those seven.

Many traditional prayer books include the sefirot of the day along with the order of the counting. More recently, prayer books offer specific meditations and intentions for each of the weeks and even each of the days.

Here, again, is a clear example of how Jewish holidays (with few major exceptions like Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur) began as responses to the agricultural cycles, then were associated with historical events, and, finally, received specifically spiritual meaning. Perhaps this reflects the essential nature of Judaism’s evolution, moving from a focus on the order of the natural world to the rhythms of the historical world and finally to the spiritual dimension — a Oneness shared by all.

Yom Ha-Shoah

In 1951, the Israeli Knesset (Parliament) set aside the 27th of Nisan (which is the twelfth day of the Omer) as Yom Ha-Shoah v’Hagevurah (“Day of the Destruction and Heroism”), usually simply called Yom Ha-Shoah. Memorializing the holocaust and the six million Jews killed, Yom Ha-Shoah is clearly a day of mourning and remembrance, and Jews hold events in most cities with large Jewish populations. Often, people publicly read the names of those killed in the Holocaust and recite the kaddish, the Jewish memorial prayer (see Chapter 4).

Israeli Independence Day

Jews celebrate Israeli Independence Day on the 20th day of the Omer, which is the fifth day of the Hebrew month of Iyar (although the days of the Omer occur on different days of the English calendar each year, they always are consistent on the Hebrew calendar).

The day preceding Independence Day is called Yom Ha-Zikaron, a “Day of Remembrance” of those who lost their lives both in the establishment and the later defense of Israel. However, at sundown (Jewish “days” begin at sundown) that spirit of mourning gives way to celebrations that turn raucous, including the rather unique proliferation of little plastic hammers that children — and adults acting like children — use to bop each other over the head. Emitting a squeak with each harmless blow, the hammers have become as much a part of the Israeli Independence Day celebration as fireworks are in the United States.

Lag B’Omer

The “official” day of respite from the semi-mourning during the Omer period arrives on 18 Iyar, at Lag B’Omer (literally, the 33rd day of Omer). Everyone seems to have their favorite reason for why the mourning should stop on this day. Some say you mourn during the Omer because a plague ran rampant among the students of Rabbi Akiba during the early years of the third century of this era, but that the plague let up during the 33rd day. Others say this was the day that manna began falling from heaven during the biblical trek to Sinai.

The Universal Themes in Passover

“Forgetfulness leads to exile, while remembrance is the secret of redemption.”

“Forgetfulness leads to exile, while remembrance is the secret of redemption.”

— Ba’al Shem Tov

The month of Nisan, whose full moon illuminates the celebration of Passover, is the first month of the Jewish year. (This gets confusing, because Rosh Hashanah is actually called the Jewish New Year; see Chapter 19.) Nisan is the beginning of spring, and it signals the reawakening of the natural world that speaks to the human spirit of renewed hope and possibility. The natural world is freed from the constraints of winter and leaps at the opportunity for new expression.

This process of reawakening is universal; this particular celebration of that reawakening is Jewish. We allow the past to be real again so that we can avoid repeating it. We broadcast the enduring messages of that past to create a vision greater than we as yet can see.

Grain flour that you buy at the store is considered khametz, even though it hasn’t been mixed with water, because it’s typically produced from grains that were washed or soaked before grinding. Kosher for Passover matzah (called

Grain flour that you buy at the store is considered khametz, even though it hasn’t been mixed with water, because it’s typically produced from grains that were washed or soaked before grinding. Kosher for Passover matzah (called  David has an Orthodox friend who, when remodeling his kitchen, ordered two countertops — one that he installed as usual, and an extra one that he tapes down with duct tape each Passover so that no food touches the unclean khametz-bearing surface.

David has an Orthodox friend who, when remodeling his kitchen, ordered two countertops — one that he installed as usual, and an extra one that he tapes down with duct tape each Passover so that no food touches the unclean khametz-bearing surface. If you choose to embark on a massive house cleaning, please be careful! Professor Yona Amitai, a senior toxicologist at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, notes that studies show that “accidental poisonings of children from cleaning fluid triples during the two or three weeks before Passover [in Jewish households], and poisonings from all other causes doubles, compared to the rest of the year.”

If you choose to embark on a massive house cleaning, please be careful! Professor Yona Amitai, a senior toxicologist at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, notes that studies show that “accidental poisonings of children from cleaning fluid triples during the two or three weeks before Passover [in Jewish households], and poisonings from all other causes doubles, compared to the rest of the year.” You can’t have beer, though; beer is made from fermented grain, so it’s

You can’t have beer, though; beer is made from fermented grain, so it’s