EDITORIAL PREFACE

THE WORKS presented in this section have suffered unwarranted neglect at the hands of some Spinoza scholars. Wolfson, for example, dismisses them by saying that “If these two works are not to be altogether disregarded by the student of the Ethics, they may be considered only as introductory to it.” (1, 1:32) The first he characterizes as a summary of the first two parts of Descartes’ Principles, together with a fragment of the third; the second, as a “summary of certain philosophic views of scholastic origin.” But this is most misleading. Though there is much in both works that Spinoza would not accept, in neither work is Spinoza merely summarizing anyone’s views.

In Descartes’ Principles, as Meyer remarks in his preface, Spinoza frequently offers proofs different from Descartes’—or offers proofs where Descartes had indulged in mere assertion. He makes use of other Cartesian works—notably the Correspondence, the Dioptrique, and the Meditations (including the Replies to objections)—to help interpret Descartes where Descartes is obscure or too brief. And sometimes he criticizes Descartes, though rarely does he do so openly.

The most important acknowledged points of difference are probably those Meyer notes (at Spinoza’s request) at the end of his preface (I/132): Spinoza does not think the will is distinct from the intellect, or endowed with the liberty Descartes ascribes to it; he does not think that the mind is a substance; and he does not think there is anything that surpasses our understanding, provided that we seek the truth in a way different from Descartes’. (See also the interesting Scholium to IP7.)

But there is a good deal of thinly veiled criticism in Spinoza’s exposition of the Principles. In the Introduction, for example, Spinoza comments that Descartes’ reply (or what he takes to be Descartes’ reply) to the charge of reasoning in a circle “will not satisfy some people.” He does not say who will be dissatisfied, or why, but immediately goes on to offer an answer of his own. In so doing, he subtly invites the reader to put his own critical faculties to work. Similar instances occur at IP8D, IP9S, IP15S, IP21Note, IIP2CS, and in the Metaphysical Thoughts at I/239, 255, 274, 276, and 277-281.

And quite apart from exposition, interpretation, and criticism of Descartes, there is much, particularly in the Metaphysical Thoughts, which is simply independent of Descartes. According to Meyer’s Preface (I/131) it was Spinoza’s intention—both in his exposition of the Principles and in the Appendix—to set out Descartes’ opinions, and their demonstrations, as they would be found in his writings or as they ought to be deduced validly from the fundamental principles of Descartes’ philosophy. But it would take a very generous interpretation of this last clause to justify everything that appears here. Spinoza’s discussions of Zeno’s paradoxes (IIP6S), or of truth (I/246-247), or of good and evil (I/247-248), go well beyond Descartes’ sketchy reflections on those topics. The reader who is familiar with Spinoza’s mature philosophy will find many passages which foreshadow the Ethics or the Theological-Political Treatise (e.g., at I/240-243, 250-252, 264-265, 266). And it is all the more interesting to see these anticipations developed as deductions from Cartesian principles.

The frequency with which Spinoza’s own opinions emerge in the Metaphysical Thoughts gave rise, at the turn of the century, to an interesting debate among German scholars about the relation of that work to Descartes’ Principles. Kuno Fischer (I:285) saw the Metaphysical Thoughts as having been written against Descartes, for the purpose of clarifying and emphasizing the disagreements which Meyer had alluded to in his Preface.1 Freudenthal, however, showed (i) that this work was certainly written before the first part of the Principles, and quite probably before any of the Principles (though, of course, it would have been revised somewhat before being printed), and (ii) that it was directed more against the scholastics than against Descartes.

And indeed, if Spinoza did write these works in the order suggested, there would be a certain logic to the presentation. The Metaphysical Thoughts begin with the definition of being and its division into those beings whose essence does, and those whose essence does not, involve existence, the latter being subdivided into substances and modes. There follows a discussion of various putative beings, which do not in fact qualify as beings (time, truth, etc.). The second part deals principally with the nature of the one infinite substance, God, and his relation to the world, but closes with a brief discussion of the nature of finite thinking substances. And the second part of the Principles completes the discussion by describing the most general features of finite corporeal substances. The work would thus be an introduction to modern philosophy, written from a broadly Cartesian point of view, for someone who already had some familiarity with the scholastic philosophy still dominant in Dutch universities.2 It would then be the first part of the Principles, not the “appendix,” which would be the afterthought.

Freudenthal (in Freudenthal 3) provided a great service to students of Spinoza by identifying some of the medieval and late scholastic authors who formed the background for the Metaphysical Thoughts: Aquinas and Maimonides, of course, were part of that background, but of the better-known scholastics Suarez was probably the most important. Also important were two now obscure Dutch writers, Burgersdijk and Heereboord.

Burgersdijk was a professor of philosophy at the University of Leiden from 1620 to 1635, and the author of a number of manuals which had a considerable influence on the teaching of philosophy in Holland. Dibon (277) comments that while, for Burgersdijk, Aristotle remained the master, “true fidelity to the spirit of Aristotle required each philosopher to adapt the traditional philosophy to the requirements of his own reflection, taking account of what preceding thinkers had contributed.” Burgersdijk’s openness to change clearly inspired his pupil Heereboord to be receptive to the new philosophy.

Heereboord was a professor of logic and ethics at Leiden from 1641 until his death in 1661. Like many Dutch philosophers of his time, he hoped to achieve a synthesis of the new philosophy and the old. By comparison with a Descartes or a Spinoza, he appears a reactionary figure. But he was, in fact, one of the reasons why the University of Leiden became known as a center of Dutch Cartesianism (see Bouillier, I, 270-271). Thijssen-Schoute (2, 96-105) reports that he embarrassed Descartes by his excessive praise of him.

Since there is some reason to think that Spinoza may have studied at the University of Leiden after his excommunication (see Revah 1, 32, 36), and since Heereboord may have been one of his teachers, the man and his work deserve to be less obscure. Spinoza frequently seems to have Heereboord in mind when he criticizes unnamed opponents, and Heereboord shares with Aristotle the distinction of being one of only two opponents to be both named and quoted. Nor does Spinoza refer to Heereboord only to disagree with him. Sometimes he adopts from Heereboord doctrines and distinctions which are of great importance in his mature philosophy (at I/240-241, for example). Whether or not Heereboord was formally his teacher, Spinoza learned from him.

So there is far more in these works than mere summary of Cartesian and scholastic doctrine. They are of the greatest importance for the study of Spinoza’s development. But they also hold much that is of interest to the student of Descartes. No less a scholar than Gilson has commended Spinoza as “an incomparable commentator” (Gilson 2, 68ff.) To say that Spinoza is always faithful to Descartes’ thought would be to claim too much, even if we considered only those passages where Spinoza intends merely to expound Descartes’ view.3 But even the errors of a Spinoza are interesting.

Finally, a word about Balling’s Dutch translation of this work. This appeared in 1664, the year after the first Latin edition. It is more than a translation, though something rather less than the second edition Meyer hoped for (cf. his Preface I/131). A number of new passages have been added, which were not consistently taken into account by any of Spinoza’s editors before Gebhardt. There seems to be no reasonable ground for doubting that these additions were made by Spinoza.

“EP” designates the reading of the first edition, “B” a reading taken from Balling’s translation.

PARTS I AND II OF DESCARTES’ PRINCIPLES OF PHILOSOPHY

Demonstrated in the geometric manner,

By Benedictus de Spinoza, of Amsterdam.

To which are added his

Metaphysical Thoughts

In which are briefly explained the more difficult problems which arise both in the general and in the special part of Metaphysics.

Amsterdam,

Johannes Riewerts,

1663

To the Honest Reader Lodewijk Meyer Presents His Greetings

[I/127] Everyone who wishes to be wiser than is common among men agrees that the best and surest Method of seeking and teaching the truth in the Sciences is that of the Mathematicians, who demonstrate their Conclusions from Definitions, Postulates, and Axioms. Indeed, this [10] opinion is rightly held. For since a certain and firm knowledge of anything unknown can only be derived from things known certainly beforehand, these things must be laid down at the start, as a stable foundation on which to build the whole edifice of human knowledge; otherwise it will soon collapse of its own accord, or be destroyed by the slightest blow.

No one who has even the most cursory acquaintance with the noble [15] discipline of Mathematics will be able to doubt that the things which are there called Definitions, Postulates, and Axioms, are of that kind. For Definitions are nothing but the clearest explanations of the words and terms by which the things to be discussed are designated; and Postulates and Axioms, or common Notions of the mind, are Propositions [20] so clear and evident that no one can deny his assent to them, provided only that he has rightly understood the terms themselves.

But in spite of this you will find hardly any sciences, other than Mathematics, treated by this Method. Instead the whole matter is arranged and executed by another, almost totally different, Method, [25] in which Definitions and Divisions are constantly linked with one another, [I/128] and problems and explanations are mixed in here and there. For almost everyone has been convinced, and many who have applied themselves to founding and writing about the sciences still are convinced, that the Mathematical Method is peculiar to the Mathematical disciplines, and does not apply to any of the rest.

[5] The result is that none of the things they produce are demonstrated by conclusive reasonings, but that they try to construct only probable arguments, foisting on the public a huge heap of huge books, in which you will find nothing that is firm and certain. All of their works are full of strife and disagreement, and whatever is corroborated by some [10] slight, insufficient reasoning is soon rebutted by another, and destroyed and torn apart by the same weapons. So the mind, which has longed for an unshakable truth, and thought to find a quiet harbor, where, after a safe and happy journey, it could at last reach the desired haven of knowledge, finds itself tossed about on a violent sea of opinions, surrounded everywhere by storms of dispute, hurled up and [15] dragged down again endlessly by waves of uncertainty, without any hope of ever emerging from them.

Nevertheless, there have been some who have thought differently, and, taking pity on the wretched plight of Philosophy, have departed from the common way of treating the sciences, and entered on an [20] arduous new path, one beset indeed with many difficulties, that they might leave to posterity the other parts of Philosophy, beyond Mathematics, demonstrated by the mathematical Method and with mathematical certainty. Some of these have put into mathematical order and communicated to the world of letters the Philosophy already received and customarily taught in the school; others have done this with a new philosophy, discovered through their own struggle.

And though many undertook that task for a long time without success, [25] at last there appeared that brightest star of our age, René Descartes. By this new Method he first brought out of darkness and into the light, whatever in Mathematics had been inaccessible to the ancients, and whatever could be desired in addition to that by his own Contemporaries. Then he uncovered firm foundations for Philosophy, foundations on which a great many truths can be built, with Mathematical [30] order and certainty, as he himself really demonstrated, and as manifests itself more clearly than the Noon light to anyone who diligently studies those writings of his, which can never sufficiently be praised.

Although the Philosophical writings of this most Noble and Incomparable Man contain a Mathematical manner and order of demonstration, [I/129] nevertheless they are not written in the style commonly used in Euclid’s Elements and in the works of other Geometricians, the style in which the Definitions, Postulates, and Axioms are set out first, followed by the Propositions and their Demonstrations. Instead they are written in a very different manner, which he calls the true and [5] best way of teaching, the Analytic. For at the end of his Reply to the Second Objections, he recognizes two ways of demonstrating things conclusively, by Analysis, “which shows the true way by which the thing was discovered, methodically, and as it were a priori,”1 and by Synthesis, “which uses a long series of definitions, postulates, axioms, [10] theorems, and problems, so that if a reader denies one of the consequences, the presentation shows him that it is contained immediately in the antecedents, and so forces his assent from him, no matter how stubborn and contrary he may be.”

But though a certainty which is placed beyond any risk of doubt is found in each way of demonstrating, they are not equally useful and [15] convenient for everyone. For since most men are completely unskilled in the Mathematical sciences, and quite ignorant, both of the Synthetic Method, in which they have been written, and of the Analytic, by which they have been discovered, they can neither follow for themselves, nor present to others, the things which are treated, and demonstrated conclusively, in these books. That is why many who have been led, either by a blind impulse, or by the authority of someone [20] else, to enlist as followers of Descartes, have only impressed his opinions and doctrines on their memory; when the subject comes up, they know only how to chatter and babble, but not how to demonstrate anything, as was, and still is, the custom among those who are attached to Aristotle’s philosophy.

To bring these people some assistance, I have often wished that someone who was skilled both in the Analytic and the Synthetic order, [25] and possessed a thorough knowledge of Descartes’ writings and Philosophy, would be willing to take on this work, to render in the Synthetic order what Descartes wrote in the Analytic, and to demonstrate it in the manner familiar to the geometricians. Indeed, I myself, though quite unequal to so great a task, and fully conscious of my weakness, frequently thought of doing this, and even began it. [30] But other occupations distracted me so often that I was prevented from completing it.

Therefore I was very pleased to learn from our Author that he had dictated, to a certain pupil of his, whom he was teaching the Cartesian [I/130] Philosophy, the whole Second Part of the Principles, and part of the Third, demonstrated in that Geometric manner, along with some of the principal and more difficult questions which are disputed in Metaphysics, and had not yet been resolved by Descartes,2 and that in response to the entreaties and demands of his friends, he had agreed [5] that, once he corrected and added to them, these writings might be published. So I too commended this project to him, and at the same time gladly offered my help in publishing, if he should require it.

Moreover, I advised him—indeed entreated him—to render also the first part of the Principles in a like order, and set it before what he had already written, so that by having been arranged in this manner from the beginning, the matter could be better understood and more pleasing. [10] When he saw the soundness of this argument, he did not wish to deny both the requests of a friend and the utility of the reader. And he entrusted to my care the whole business of printing and publishing, since he lives in the country, far from the city, and so could not be present.3

This, then, honest Reader, is what we give you in this little book: [15] the first and second parts of Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy, together with a fragment of the third, to which we have attached, as an Appendix, our Author’s Metaphysical Thoughts. But when we say, and when the title of the book promises, the first part of the Principles, we do not mean that everything Descartes says there is demonstrated here [20] in Geometric order, but only that the main matters which concern Metaphysics, and were treated by Descartes in his Meditations, have been taken from there (leaving aside whatever is a matter of Logic, or is recounted only historically).4

To do this more easily, our Author has carried over, word for word, [25] almost all the things which Descartes put in Geometrical order at the end of his Reply to the Second Objections—beginning with all of Descartes’ Definitions and inserting Descartes’ Propositions among his own, but not annexing the Axioms to the Definitions without interruption. He has placed the Axioms taken from Descartes after the fourth Proposition and altered their order, so they could be demonstrated more [30] easily. He has also omitted certain things which he did not require.

Our Author realizes that these Axioms could be demonstrated as Theorems (as Descartes himself says in the 7th postulate), and that they would be more elegantly treated as Propositions. And though we [I/131] asked him to do this, more important business in which he was involved allowed him only two weeks in which to complete this work. So he was unable to satisfy his desire and ours. Annexing at least a brief explanation, which can take the place of a proof, he has put off [5] a fuller explanation, complete in every respect, till another time. Perhaps, after this printing is exhausted, a new one will be prepared. If so, we shall also try to get him to enrich it by completing the Third Part, On the visible World (we have added here only a fragment of that Part, since our Author ended the instruction of his pupil at that point, and we did not wish to deprive the reader of it, however little [10] it was). For this to be done properly, it will be necessary to introduce certain Propositions concerning the nature and properties of Fluids in the Second Part. I shall do my best to see that our Author accomplishes this at that time.

Our Author quite frequently departs from Descartes, not only in [15] the arrangement and explanation of the Axioms, but also in the demonstration of the Propositions themselves, and the rest of the Conclusions; he often uses a Proof very different from Descartes’. Let no one take this to mean that he wished to correct that most distinguished Man in these matters; it was done only so as to better retain the order he had already taken up, and not to increase unduly the number of [20] Axioms. For the same reason he has also been forced to demonstrate quite a number of things which Descartes asserted without any demonstration, and to add others which he completely omitted.

Nevertheless, I should like it to be particularly noted that in all these writings—not only in the first and second parts of the Principles, and in the fragment of the third part, but also in his Metaphysical [25] Thoughts—our Author has only set out the opinions of Descartes and their demonstrations, insofar as these are found in his writings, or are such as ought to be deduced validly from the foundations he laid. For since he had promised to teach his pupil Descartes’ philosophy, he considered himself obliged not to depart a hair’s breadth from Descartes’ opinion,5 nor to dictate to him anything that either would not [30] correspond to his doctrines or would be contrary to them. So let no one think that he is teaching here either his own opinions, or only those which he approves of. Though he judges that some of the doctrines are true, and admits that he has added some of his own, nevertheless there are many that he rejects as false, and concerning which he holds a quite different opinion.

[I/132] An example of this—to mention only one of many—is what is said concerning the will in the Principles IP15S and in the Appendix, II, 12, although it seems to be proved with sufficient diligence and preparation. For he does not think that the will is distinct from the Intellect, [5] much less endowed with such freedom. Indeed in asserting these things—as is evident from the Discourse on Method, Part IV, the Second Meditation, and other places—Descartes only assumes, but does not prove that the human mind is a substance thinking absolutely. Though our Author admits, of course, that there is a thinking substance in nature, he nevertheless denies that it constitutes the essence of the [10] human Mind; instead he believes that just as Extension is determined by no limits, so also Thought is determined by no limits. Therefore, just as the human Body is not extension absolutely, but only an extension determined in a certain way according to the laws of extended nature by motion and rest, so also the human Mind, or Soul, is not [15] thought absolutely, but only a thought determined in a certain way according to the laws of thinking nature by ideas, a thought which, one infers, must exist when the human body begins to exist. From this definition, he thinks, it is not difficult to demonstrate that the Will is not distinct from the intellect, much less endowed with that liberty which Descartes ascribes to it; that that faculty of affirming [20] and denying is a mere fiction; that affirming and denying are nothing but ideas; and that the rest of the faculties, like Intellect, Desire, etc., must be numbered among the fictions, or at least among those notions which men have formed because they conceive things abstractly, like humanity, stone-hood, and other things of that kind.

[25] Again we must not fail to note that what is found in some places—viz. that this or that surpasses the human understanding—must be taken in the same sense, i.e., as said only on behalf of Descartes. For it must not be thought that our Author offers this as his own opinion. He judges that all those things, and even many others more sublime and [30] subtle, can not only be conceived clearly and distinctly, but also explained very satisfactorily—provided only that the human Intellect is guided in the search for truth and knowledge of things along a different path from that which Descartes opened up and made smooth. The foundations of the sciences brought to light by Descartes, and the [I/133] things he built on them, do not suffice to disentangle and solve all the very difficult problems that occur in Metaphysics. Different foundations are required, if we wish our intellect to rise to that pinnacle of knowledge.

[5] Finally—to put an end to prefacing—we wish our Readers to know that all the things treated here are published with no purpose except that of searching out and propagating the truth, and rousing men to strive for a true and genuine Philosophy; so in order that men may be able to harvest that rich fruit which we sincerely desire each of them to have, we warn them, before they set themselves to read this book, [10] to insert in their place certain things which have been omitted, and to correct accurately the Typographical errors which have crept in. For some of them could be an obstacle to a correct perception of the Author’s intention, and the force of the Demonstration, as anyone who inspects them will easily see.

[I/141] The Principles of Philosophy Demonstrated In the Geometric Manner

[5] Part I

PROLEGOMENON

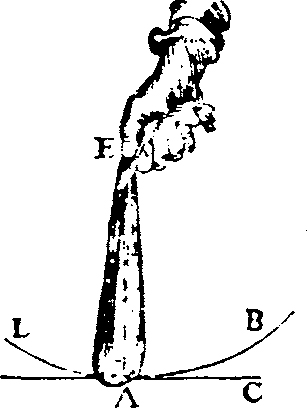

Before we come to the Propositions themselves and their Demonstrations, it seems desirable to explain concisely why Descartes doubted [10] everything, how he brought to light solid foundations for the sciences, and finally, by what means he freed himself from all doubts. We would have reduced even all these things to Mathematical order, if we had not judged that the prolixity required by such a presentation would [15] prevent them from being understood as they ought to be. For they should all be seen in a single act of contemplation, as in a picture.

Descartes, then, in order to proceed as cautiously as possible in the investigation of things, attempted

(1) to lay aside all prejudices,

[20] (2) to discover the foundations on which all things ought to be built,

(3) to uncover the cause of error,

(4) to understand all things clearly and distinctly.

That he might be able to attain the first, second and third of these, he [25] sought to call all things into doubt, not as a Skeptic would, who has no other end than doubting, but to free his mind from all prejudices, so that in the end he might discover firm and unshakable foundations of the sciences. In this way, if there were any such foundations, they [30] could not escape him. For the true principles of the sciences must be [I/142] so clear and certain that they need no proof, that they are beyond all risk of doubt, and that nothing can be demonstrated without them. These he found, after a long period of doubting. And after he had discovered these principles, it was not difficult for him to distinguish [5] the true from the false, to uncover the cause of error, and so to put himself on guard against assuming something false and doubtful as true and certain.1

To obtain the fourth and last, i.e., that he might understand all things clearly and distinctly, his chief rule was to enumerate and examine [10] separately all the simple ideas of which all the rest of his ideas were compounded. For when he could perceive the simple ideas clearly and distinctly, he would undoubtedly understand, with the same clarity and distinctness, all the rest, which have been constructed from those simple ideas.

[15] With this as preface, we shall explain briefly how he called all things into doubt, discovered the true principles of the Sciences, and extricated himself from the difficulties of his doubts.

Doubt concerning all things

First, then, he considered all those things which he had received from the senses, viz. the heavens, the earth, and the like, and even his [20] own body. All these he had till then thought to exist in nature. And he came to doubt their certainty because he had realized that the senses sometimes deceived him, because in dreams he had often persuaded himself of the existence outside himself of many things, concerning which he afterwards discovered himself to have been deluded, and [25] finally, because he had heard others claim, even while awake, that they felt pain in limbs which they had long lacked.2 So it was not without reason that he was able to doubt the existence of his own body.

From all this he was able to conclude truly that the senses are not that most firm foundation on which every science should be built (for [30] they can be called into doubt), but that certainty depends on other principles, of which we are more certain.

To investigate such principles then, he considered second all universals, such as corporeal nature in general, and its extension, figure, [I/143] quantity, and also all Mathematical truths. And though these seemed more certain to him than all those he had derived from the senses, nevertheless he discovered a reason for doubting them: for others had erred even about these matters, and most important, deeply rooted in [5] his mind was an old opinion, according to which there is a God who can do all things and by whom he was created such as he was. Perhaps this God had made him so that he would be deceived even about those things that seemed clearest to him. And this is the way he called all things in doubt.

The discovery of the foundation of the whole science

To discover the true principles of the sciences, he asked next whether [10] he had called into doubt everything which could fall under his thought. His purpose was to examine whether, perhaps, there was not something remaining which he had not yet doubted. And if he did, by doubting in this way, discover something which could be called into doubt by none of the preceding reasons, nor by any other, he rightly [15] judged that he should set it up as the foundation on which he might build all his knowledge.

And though it seemed that he had already doubted everything—for he had doubted both the things he had derived from the senses and those he had perceived by the intellect alone—nevertheless, there was [20] something remaining which should be examined, viz. he himself who was doubting in this way. Not himself insofar as he consisted of a head, hands, and the other members of the body, since he had doubted these things, but only himself insofar as he was doubting, thinking, etc.

And when he considered it accurately, he discovered that he could not doubt it for any of the previously mentioned reasons. For whether [25] he thinks waking or sleeping, he still thinks and is. And though others, and even he himself had erred concerning other things, since they were erring, they were. Nor could he feign any author of his nature so cunning3 as to deceive him about this. For it will have to be conceded that he exists, so long as it is supposed that he is deceived. [30] Finally, whatever other reason for doubting might be thought up, none could be mentioned that did not at the same time make him most certain of his existence. Indeed, the more reasons for doubting are brought up, the more arguments are brought up that convince him of [I/144] his existence. So in whatever direction he turns in order to doubt, he is forced to break out with these words: I doubt, I think, therefore I am.

Hence, because he had laid bare this truth, he had at the same time also discovered the foundation of all the sciences, and also the measure [5] and rule of all other truths: Whatever is perceived as clearly and distinctly as that is true.4

That there can be no other foundation of the sciences than this, is more than sufficiently evident from the preceding. For we can call all the rest in doubt with no difficulty, but we can not doubt this in any [10] way.

But what we must note here, above all else concerning this foundation, is that this formula, I doubt, I think, therefore I am, is not a syllogism in which the major premise is omitted. For if it were a syllogism, the premises would have to be clearer and better known [15] than the conclusion itself, therefore I am. And so, I am would not be the first foundation of all knowledge. Moreover, it would not be a certain conclusion. For its truth would depend on universal premises which the Author had previously put in doubt. So I think, therefore I am is a single proposition which is equivalent to this, I am thinking.5

[20] Next, to avoid confusion in what follows, we need to know what we are (for this is a matter that ought to be perceived clearly and distinctly). Once we do understand it clearly and distinctly, we shall not confuse our essence with others. To deduce it from the above, our Author proceeded as follows.

[25] He recalled all the thoughts which he had formerly had of himself, e.g., that his soul was something tenuous, like wind, or fire, or air, infused throughout the grosser parts of his body, that the body was better known to him than the soul, and that he perceived it more [30] clearly and distinctly. And he observed that all these thoughts are clearly incompatible with those which up to this point he had understood. For he was able to doubt his own body, but not his own essence, insofar as he was thinking. Moreover, he perceived these thoughts neither clearly nor distinctly, and consequently, according to the rule of his method, he was obliged to reject them as false.

[I/145] Since he could not understand such things to pertain to himself, insofar as he was known to himself up to this point, he proceeded to inquire further what did properly pertain to his essence, which he could not put in doubt, and on account of which he was forced to infer his existence. But these were such things as: that he wished to take [5] care lest he be deceived; that he desired to know many things; that he doubted all things which he could not understand; that so far he affirmed only one thing; that he denied all the rest and rejected them as false; that he imagined many things, even though unwilling to; and finally that he perceived many things as if coming from the senses. Since he could infer his existence from [10] each of these things equally clearly, and could count none of them among those which he had called in doubt, and finally, since they can all be conceived under the same attribute, it followed that all these things were true and pertained to his nature. So when he said, I think, [15] all these modes of thinking were understood, viz. doubting, understanding, affirming, denying, willing, not willing, imagining, and sensing.6

But here the chief things to be noted—because they will be very useful later, when we deal with the distinction between mind and body—are (i) that these modes of thinking are understood clearly and [20] distinctly without the rest, concerning which there is still doubt, and (ii) that the clear and distinct concept we have of them is made obscure and confused, if we wish to ascribe to them any things concerning which we still doubt.

Liberation from all doubts

Finally, in order to become certain of the things he had called in [25] doubt and to remove all doubt, Descartes proceeded to inquire into the nature of the most perfect Being, and whether such a Being existed. For when he discovers that there is a most perfect being, by whose power all things are produced and conserved, and with whose nature being a deceiver is incompatible, then that reason for doubting which he had because he was ignorant of his cause will be removed. [30] He will know that a God who is supremely good and veracious did not give him the faculty of distinguishing the true from the false so that he might be deceived. Hence neither Mathematical truths nor any of those that seem most evident to him can be at all suspected.

Next, to remove the remaining causes of doubt, he went on to ask [I/146] how it happens that we sometimes err. When he discovered that this occurs because we use our free will to assent even to things we have perceived only confusedly, he was able to conclude immediately that he could guard against error in the future, provided he gave his assent [5] only to things perceived clearly and distinctly. Each of us can easily accomplish this by himself, since each has the power of restraining the will, and so of bringing it about that it is contained within the limits of the intellect.

But because we have absorbed at an early age many prejudices from [10] which we are not easily freed, he went on next to enumerate and examine separately all the simple notions and ideas of which all our thoughts are composed, so that we might be freed from our prejudices, and accept nothing but what we perceive clearly and distinctly. For if he could take note of what was clear and what obscure in each, [15] he would easily be able to distinguish the clear from the obscure and to form clear and distinct thoughts. In this way he would discover easily the real distinction between the soul and the body, what was clear and what obscure in the things we have derived from the senses, and finally, how a dream differs from waking states. Once this was [20] done, he could no longer doubt his waking states nor be deceived by the senses. So he freed himself from all the doubts recounted above.

But before we finish, it seems we must satisfy those who make the following objection. Since God’s existence does not become known to [25] us through itself, we seem unable to be ever certain of anything; nor will we ever be able to come to know God’s existence. For we have said that everything is uncertain so long as we are ignorant of our origin, and from uncertain premises, nothing certain can be inferred.

To remove this difficulty, Descartes makes the following reply.7 [30] From the fact that we do not yet know whether the author of our origin has perhaps created us so that we are deceived even in those things that appear most evident to us, we cannot in any way doubt the things that we understand clearly and distinctly either through themselves or through reasoning (so long, at any rate, as we attend to [II/147] that reasoning). We can doubt only those things that we have previously demonstrated to be true, and whose memory can recur when we no longer attend to the reasons from which we deduced them and, indeed, have forgotten the reasons. So although God’s existence cannot [5] come to be known through itself, but only through something else, we will be able to attain a certain knowledge of his existence so long as we attend very accurately to all the premises from which we have inferred it. See Principles I, 13; Reply to Second Objections, 3, and Meditation 5, at the end.

[10] But since this answer does not satisfy some people, I shall give another.8 When we previously discussed the certainty and evidence of our existence, we saw that we inferred it from the fact that, wherever we turned our attention—whether we were considering our own nature, [15] or feigning some cunning deceiver as the author of our nature, or summoning up, outside us, any other reason for doubting whatever—we came upon no reason for doubting that did not by itself convince us of our existence.

So far we have not observed this to happen regarding any other [20] matter. For though, when we attend to the nature of a Triangle, we are compelled to infer that its three angles are equal to two right angles, nevertheless we cannot infer the same thing from [the supposition] that perhaps we are deceived by the author of our nature. But from [this supposition] we did most certainly infer our existence. So [25] here we are not compelled, wherever we direct our attention, to infer that the three angles of a Triangle are equal to two right angles. On the contrary, we discover a ground for doubting, viz. because we have no idea of God which so affects us that it is impossible for us to think [30] that God is a deceiver. For to someone who does not have a true idea of God (which we now suppose ourselves not to have) it is just as easy to think that his author is a deceiver as to think that he is not a deceiver. Similarly for one who has no idea9 of a Triangle, it is just as easy to think that its three angles are equal to two right angles, as to think that they are not.

[I/148] So we concede that we can not be absolutely certain of anything, except our own existence, even though we attend properly to its demonstration, so long as we have no clear and distinct concept of God [5] that makes us affirm that he is supremely veracious, just as the idea we have of a Triangle compels us to infer that its three angles are equal to two right angles. But we deny that we cannot, therefore, arrive at knowledge of anything.

For as is evident from everything we have said just now, the crux [10] of the whole matter is that we can form a concept of God which so disposes us that it is not as easy for us to think that he is a deceiver as to think that he is not, but which now compels us to affirm that he is supremely veracious. When we have formed such an idea, that reason for doubting Mathematical truths will be removed. Wherever we [15] then direct our attention in order to doubt some one of them, we shall come upon nothing from which we must not instead infer that it is most certain—as happened concerning our existence.

E.g., if, after we have discovered the idea of God, we attend to the nature of a Triangle, the idea of this will compel us to affirm that its [20] three angles are equal to two right angles; but if we attend to the idea of God, this too will compel us to affirm that he is supremely veracious, and the author and continual conserver of our nature, and therefore that he does not deceive us concerning that truth. Nor will it be less impossible for us to think that he is a deceiver, when we attend [25] to the idea of God (which we now suppose ourselves to have discovered), than it is for us to think that the three angles of a Triangle do not equal two right angles, when we attend to the idea of a Triangle. And just as we can form such an idea of a Triangle, even though we do not know whether the author of our nature deceives us, so also we [30] can make the idea of God clear to ourselves and put it before our eyes, even though we still doubt whether the author of our nature deceives us in all things. And provided we have it, however we have acquired it, it will suffice to remove all doubt, as has just now been shown.

Therefore, from these premises we reply as follows to the difficulty [I/149] raised. We can be certain of nothing—not, indeed, so long as we are ignorant of God’s existence (for I have not spoken of this)—but as long as we do not have a clear and distinct idea of him.

So if anyone wishes to argue against me, his objection will have to [5] be this: we can be certain of nothing before we have a clear and distinct idea of God; but we cannot have a clear and distinct idea of God so long as we do not know whether the author of our nature deceives us; therefore, we can be certain of nothing so long as we do not know whether the author of our nature deceives us, etc.

[10] To this I reply by conceding the major and denying the minor. For we have a clear and distinct idea of a Triangle, although we do not know whether the author of our nature deceives us; and provided we have such an idea (as I have just shown abundantly), we will be able [15] to doubt neither his existence, nor any Mathematical truth.

With this as preface, let us now come to the matter itself.

DEFINITIONS10

D1: Under the word thought I include everything which is in us and of which we are immediately conscious.

[20] So all operations of the will, the intellect, the imagination and the senses are thoughts. But I have added immediately to exclude those things that follow from thoughts, e.g., voluntary motion does have thought as its principle, but it is still not itself a thought.

D2: By the term idea I understand that form of each thought through [25] the immediate perception of which I am conscious of the thought itself.

So if I understand what I say, I cannot express anything in words, without its being certain from this that there is in me an idea of what is signified by those words.11 And so I do not call only images depicted in the fantasy ideas. [30] Indeed I do not here call them ideas at all, insofar as they are depicted in the corporeal fantasy, i.e., in some part of the brain, but only insofar as they give form to the mind itself which is directed toward that part of the brain.

[I/150] D3: By the objective reality of an idea I understand the being of the thing represented by the idea, insofar as it is in the idea.

In the same way, one can speak of objective perfection, or objective artifice, etc. For whatever we perceive as in the objects of the ideas is in the ideas [5] themselves objectively.

D4: The same things are said to be formally in the objects of the ideas when they are in the objects as we perceive them, and eminently when they are in the objects, not indeed as we perceive them, but to such an extent as to be able to take the place of such things.

[10] Note that when I say the cause contains the perfections of its effect eminently, I mean that the cause contains the perfections of the effect more excellently than the effect itself does. See also A8.

D5: Everything in which there is immediately, as in a subject, or through which there exists, something we perceive, i.e., some property, [15] or quality, or attribute, of which there is a real idea in us, is called Substance.12

For of substance itself, taken precisely, we have no idea, other than that it is a thing in which exists formally or eminently that something which we [20] perceive, or, which is objectively in one of our ideas.13

D6: A substance in which thought is immediately is called a Mind.

I speak here of mind [mens] rather than soul [anima], because the word soul is equivocal and is often taken for a corporeal thing.14

D7: A substance which is the immediate subject of extension15 and of [30] accidents which presuppose extension, like figure, position, local motion, etc., is called a body.

But whether the substance called mind is one and the same as that called body, or whether they are two different substances, will need to be asked later.

D8: The substance which we understand to be through itself16 supremely perfect, and in which we conceive nothing which involves any defect or limitation of perfection, is called God.

D9: When we say that something is contained in the nature or concept [I/151] of something, that is the same as saying that it is true of that thing, i.e., can be truly affirmed of it.17

D10: Two substances are said to be really distinct when each of them can exist without the other.

[5] We have omitted Descartes’ postulates here, because we infer nothing from them in what follows. Still we earnestly ask the reader to read through them, to consider them, and to meditate on them carefully.

AXIOMS18

A1: We do not arrive at knowledge and certainty of an unknown thing [10] except by the knowledge and certainty of another thing which is prior19 to it in certainty and knowledge.

A2: There are reasons which make us doubt the existence of our body.

[15] This has been shown in the Prolegomenon, and so it is made an axiom here.

A3: If we have anything beyond a mind and a body, it is less known to us than the mind and the body.

It should be noted that these axioms make affirmations concerning no things outside us, but only concerning those things which we find in us, insofar as we are thinking things.20

[20] PROPOSITIONS

P1: We cannot be absolutely certain of anything, so long as we do not know that we exist.

Dem.: This proposition is evident through itself. For whoever absolutely [25] does not know that he is, equally does not know that he is affirming or denying, i.e., that he certainly affirms or denies.21

But it should be noted here that although we affirm and deny many things with great certainty without attending to the fact that we exist, nevertheless, unless this is presupposed as indubitable it is possible for everything to be called [30] in doubt.

[I/152] P2: I am must be known through itself.

Dem.: If you deny this, then it will not become known except through [5] something else, the knowledge and certainty of which (by A1) will be prior in us to this proposition, I am. But this is absurd (by P1). Therefore, it must be known through itself, q.e.d.

P3: I, insofar as I am a thing consisting of a body, am, is not the first thing [10] known, nor is it known through itself.

Dem.: There are certain things which make us doubt the existence of our body (by A2); therefore (by A1), we shall not arrive at certainty of [the existence of our body] except through the knowledge and certainty [15] of another thing, which is prior to it in knowledge and certainty. Therefore, the proposition that I, insofar as I am a thing consisting of a body, am, is not the first thing known, nor is it known through itself, q.e.d.

[20] P4: I am cannot be the first thing known except insofar as we think.

Dem.: The proposition I am a corporeal thing or one consisting of a body is not the first thing known (P3). Nor am I certain of my existence [I/153] insofar as I consist of anything else besides a mind and a body. For if we consist of anything else different from the mind and the body, this is less known to us than the body (A3). So I am can not be the first thing known except insofar as we think, q.e.d.

[5] Cor.: Hence it is evident that the mind, or thinking thing, is better known than the body. For a fuller explanation, see Principles I, 11 and 12.

[10] Schol.: Everyone perceives most certainly that he affirms, denies, doubts, understands, imagines, etc., or that he exists doubting, understanding, affirming, etc., or in a word, thinking. Nor can this be [15] called in doubt. So the proposition I think, or I am Thinking is the unique (P1) and most certain foundation of the whole of Philosophy.

Now to be completely certain of matters in the sciences nothing more can be sought or desired than to deduce all things from the firmest principles and to render them as clear and distinct as the principles [20] from which they are deduced. So clearly whatever is equally evident to us, whatever we perceive as clearly and distinctly as the principle we have already discovered, and whatever so agrees with this principle, and so depends on it that if we should wish to doubt it we would have to doubt this principle as well, must be held most true.22

[25] But to proceed as cautiously as possible in examining these matters, I shall admit in the beginning, as equally evident and as perceived by us with equal clarity and distinctness, only those things that each of us observes in himself, insofar as he is thinking. E.g., that he wills [30] this and that, that he has ideas of a certain sort, that one idea contains in itself more reality and perfection than another, that the idea which contains objectively the being and perfection of substance is far more [I/154] perfect than the one which contains only the objective perfection of some accident, and finally that the idea of a supremely perfect being is the most perfect of all. These, I say, we perceive not only with equal evidence and clarity, but even, perhaps, more distinctly. For [5] they affirm not only that we think, but also how we think.

Next we shall also say that those [propositions] agree with this principle which cannot be called into doubt unless at the same time this unshakable foundation of ours should be put in doubt. E.g., if someone should wish to doubt whether something comes from nothing, he [10] will at the same time be able to doubt whether we exist when we think. For if I can affirm something of nothing—viz. that it can be the cause of something—I shall be able at the same time, with the same right, to affirm thought of nothing, and to say that I am nothing when I think. But since I cannot do that, it will also be impossible for me [15] to think that something may come from nothing.

Having considered these matters, I decided to set out here, in order, the things which at present seem necessary to enable us to go further, and to add to the number of Axioms. They are put forward as axioms by Descartes, at the end of the Replies to the Second Objections, and [20] I do not wish to be more accurate than he is.23 Nevertheless, so as not to depart from the order already begun, I shall try to make them somewhat clearer and to show how one depends on the other and how they all depend on this principle—I am thinking—or agree with it in evidence and reason.

[25] AXIOMS TAKEN FROM DESCARTES

A4: There are different degrees of reality, or being: for a substance has more reality than an accident or mode, and the infinite substance more than a finite; accordingly there is more objective reality in the [30] idea of a substance than in that of an accident, and in the idea of the infinite substance than in that of a finite [substance].

This axiom comes to be known just from the contemplation of our ideas, of [I/155] whose existence we are certain, because they are modes of thinking. For we know how much reality or perfection the idea of substance affirms of a substance, and how much the idea of mode affirms of a mode.24 Hence we necessarily find that the idea of substance contains more objective reality than that [5] of some accident. See P4S.

A5: If a thinking thing knows any perfections which it lacks, it will immediately give them to itself, if they are in its power.

Everyone observes this in himself, insofar as he is a thinking thing. Consequently [10] (by P4S) we are most certain of it. And for the same reason we are no less certain of the following, viz.,

A6: Existence—either possible or necessary—is contained in the idea, or concept, of every thing (see Descartes, A10). Necessary existence, in the concept of God, or of a supremely perfect being (for otherwise he would be [15] conceived as imperfect, contrary to what is supposed to be conceived); but contingent, or possible, in the concept of a limited thing.

A7: No actually existing thing and no actually existing perfection of a thing can have nothing, or a thing not existing, as the cause of its existence.

[20] In P4S I have demonstrated that this axiom is as evident to us as I am thinking.

A8: Whatever reality, or perfection, there is in any thing, exists formally or eminently in its first and adequate cause.

[25] I understand that the reality is in the cause eminently when the cause contains the whole reality of the effect more perfectly than the effect itself, but formally when it contains it as perfectly.

This axiom depends on the preceding one. For if it were supposed that there was either nothing in the cause, or less in the cause than in the effect, then the [30] nothing in the cause would be the cause of the effect. But this (by A7) is absurd. So not anything can be cause of an effect, but only that in which there is every perfection which is in the effect either eminently or at least formally.

A9: The objective reality of our ideas requires a cause in which the [I/156] same reality itself is contained, not only objectively, but formally or eminently.

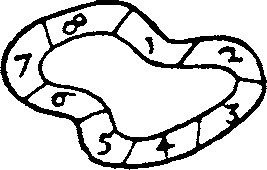

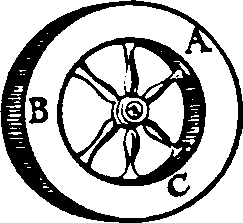

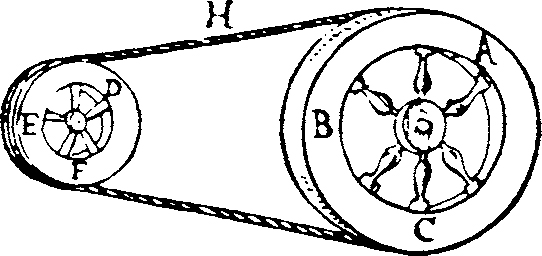

Though many people misapply this axiom, it is acknowledged by everyone. For whenever anyone has conceived something new, there is no one who does [5] not look for the cause of that concept, or idea. When they can assign one which contains formally or eminently as much reality as that concept contains objectively, they are satisfied. This is explained adequately by the example of the machine which Descartes uses in the Principles (I, 17).

Again, if anyone should ask from what source a man has the ideas of his [10] thought and of his body, no one fails to see that he has them from himself, as containing formally all that the ideas contain objectively. So, if a man were to have some idea which contained more objective reality than he contained formally, we would be driven by the natural light to look for another cause, outside the man himself, which contained all that perfection formally or eminently. [15] Nor has anyone ever assigned any other cause, except this one, which he conceived as clearly and distinctly.

As for the truth of this axiom, it depends on the preceding one. For (by A4) there are different degrees of reality or being in ideas, and therefore by (A8) [20] the more perfect they are, the more perfect the cause they require. But the degrees of reality which we perceive in our ideas are not in the ideas insofar as they are considered as modes of thinking, but rather insofar as one represents a substance and another represents only a mode of substance—or, in a word, insofar as they are considered as images of things.a So clearly, there can be no [25] other first cause of ideas except that which (as we have just shown) everyone understands clearly and distinctly by the natural light: viz., one in which there is contained either formally or eminently the same reality which the ideas have objectively.

That this conclusion may be more clearly understood, I shall explain it with one or two examples. Suppose someone sees two books—one the work of a distinguished [30] philosopher, the other that of some trifler, but both written in the same hand. If he attends to the meaning of the words (that is, does not attend to them insofar as they are like images), but only to the handwriting and to the order of the letters, he will recognize no inequality between them which [I/157] compels him to look for different causes. They will seem to him to have proceeded from the same cause in the same way. But if he attends to the meaning of the words and the discourses,25 he will find a great inequality between them. And so he will conclude that the first cause of the one book was very different from the first cause of the other, and really more perfect than it in proportion to the [5] differences he finds between the meaning of the discourses of each book, or between the words considered as images. I speak of the first cause of the books; there must be a first cause, though I concede—indeed I assume—that one book can be copied from another, as is obvious in itself.

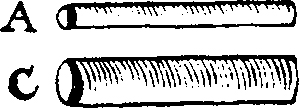

The same [axiom] can also be explained clearly by the example of a portrait—say [10] of some Prince. For if we attend only to its materials, we shall find between it and other portraits no inequality which would force us to look for different causes. On the contrary, nothing will prevent us from being able to think that it has been painted from another picture, and that one again from [15] another, and so on to infinity. For we shall discern [clearly] enough that no other cause is required for drawing it. But if we attend to the image insofar as it is an image we shall immediately be forced to look for a first cause which contains, formally or eminently, what the image contains by representation. I do not see what more could be desired for the confirmation and clarification of this axiom.

[20] A10: No less a cause is required for preserving a thing than for first producing it.

From the fact that we are thinking now, it does not necessarily follow that we shall be thinking afterwards. For the concept which we have of our thought does not involve, or contain, the necessary existence of the thought. I can [25] conceive the thought clearly and distinctly even though I suppose that it does not exist.b

But the nature of every cause must contain or involve in itself the perfection of its effect (by A8). From this it follows clearly that there must be something, either in us or outside us, which we have not yet understood, whose concept, [30] or nature, involves existence and which is the cause of our thought’s having begun to exist, and also of its continuing to exist. For though our thought has begun to exist, its nature and essence does not on that account involve necessary existence any more than before it existed. So it needs the same power to persevere [I/158] in existing as it needed to begin existing. And what we say here about thought, must also be said about anything whose essence does not involve necessary existence.

A11: Nothing exists of which it cannot be asked, what is the cause, or reason, why it exists. See Descartes’ A1.

[5] Since existing is something positive, we cannot say that it has nothing as its cause (by A7). Therefore we must assign some positive cause, or reason, why [a thing] exists—either an external one, i.e., one outside the thing itself, or an internal one, i.e., one comprehended in the nature and definition of the existing thing itself.

The following four propositions are taken from Descartes.

P5: God’s existence is known from the consideration of his nature alone.

[15] Dem.: To say that something is contained in the nature, or concept, of something is the same as saying that it is true of that thing (by D9). But necessary existence is contained in the concept of God (by A6). So, it is true to say of God that necessary existence is in him, or that he exists.

[20] Schol.: Many excellent things follow from this proposition. Indeed, almost all that knowledge of God’s attributes through which we are led to the love of him, or the highest blessedness, depends on this alone: that existence pertains to the nature of God, or that the concept of God involves necessary existence, as the concept of a triangle involves [25] that its three angles are equal to two right angles, or that his existence, no less than his essence, is an eternal truth. So it would be [I/159] very desirable for the human race at last to embrace these things with us.

I confess, of course, that there are certain prejudices that stand in the way of everyone’s understanding this so easily.c But if anyone [5] moved by a good intention and by the simple love of the truth and of his own true advantage, should wish to examine the matter and to weigh carefully the things considered in the Fifth Meditation and at the end of the Replies to the First Objections, as well as what we say about eternity in our Appendix (II, 1), he will doubtless understand [10] it as clearly as possible, and no one will be able to doubt whether he has an idea of God, which, of course, is the first foundation of human blessedness. For he will see that the idea of God is very different from the ideas of other things as soon as he understands that God differs in every way from other things, with respect both to his essence and to [15] his existence. So there is no need to detain the Reader longer about these matters.

P6: God’s existence is demonstrated a posteriori from the mere fact that there is an idea of him in us.

[20] Dem.: The objective reality of any of our ideas requires a cause in which the very same reality is contained, not only objectively, but formally or eminently (by A9). But we have an idea of God (by D2 and D8), [25] and the objective reality of this idea is not contained either formally or eminently in us (by A4); nor can it be contained in any other thing except God himself (by D8). So this idea of God which is in us requires God as its cause, God, therefore, exists (by A7).

[I/160] Schol.: There are some who deny that they have any idea of God, and who nevertheless (so they say) worship and love him. And though you may put before them a definition of God, and God’s attributes, [5] you will still gain nothing by it, no more than if you labored to teach a man blind from birth the differences between the colors, just as we see them. But unless we should wish to regard them as a new kind of animal, between men and the lower animals, we must not bother too [10] much about their words. How, I ask, can we make the idea of any thing known except by propounding its definition and explaining its attributes? Since we offer this concerning the idea of God, there is no reason for us to be delayed by the words of men who deny that they have an idea of God merely because they can form no image of him in their brain.

[15] Next we should note that when Descartes cites A4 to show that the objective reality of our idea of God is not contained in us, either formally or eminently, he supposes that everyone knows that he is not an infinite substance—i.e., supremely intelligent, powerful, etc. He is [20] entitled to suppose this because he who knows that he thinks, knows also that he has doubts about many things and does not understand everything clearly and distinctly.

Finally, we must note that it also follows clearly from D8 that there can not be more than one God, as we clearly demonstrate in P11 and in our Appendix, II, ii.

[25] P7: The existence of God is also demonstrated from the fact that we ourselves who have an idea of him exist.

Schol.: To demonstrate this proposition Descartes assumes these [I/161] two axioms: (1) What can bring about the greater, or more difficult, can also bring about the lesser; (2) It is greater to create, or (by A10) to preserve, a substance than the attributes, or properties, of a substance. But what he means by this I do not know. What does he call easy, and what difficult? [5] Nothing is said to be easy or difficult absolutely, but only in relation to a cause. So one and the same thing can at the same time be called both easy and difficult in relation to different causes.d

But if he calls difficult those things that can be accomplished [by a cause] with great labor, and easy, those that can be accomplished by [10] the same cause with less labor—as a force which can lift 50 pounds will be able to lift [25] pounds twice as easily—then of course, the axiom will not be absolutely true, nor will he be able to demonstrate from it what he wants to. For when he says [AT VII, 168], if I had the power of preserving myself, I would also have the power of giving myself all the perfections I lack (because they do not require such a great power), [15] I would concede this to him. The powers I expend in preserving myself could bring about many other things far more easily, if I did not require them for preserving myself. But so long as I use them for preserving myself, I deny that I can expend them to bring about other things, even though they are easier, as is clear in our example.

[20] It does not remove the difficulty if it is said that since I am a thinking thing I would necessarily have to know whether I spend all my powers in preserving myself, and also whether this is the cause of my [25] not giving myself the remaining perfections. The dispute now does not concern this, but only how the necessity of this proposition follows from this axiom. Moreover, if I knew it, I would be greater, and perhaps would require greater powers to preserve myself in that greater perfection than those I have.26

And then I do not know whether it is a greater work to create (or preserve) a substance than to create (or preserve) attributes. To speak [30] more clearly and Philosophically, I do not know whether a substance does not require its whole power and essence, by which it perhaps preserves itself, for preserving its attributes.27

But let us leave these things to examine further what our most noble Author means here, i.e., what he understands by easy and difficult. I [I/162] do not think, nor can I in any way persuade myself, that by difficult he understands what is impossible (so that it cannot in any way be conceived how it happens), and by easy, what implies no contradiction (so that it can easily be conceived how it happens). It is true that he [5] seems at first glance to mean this, when he says in the Third Meditation [AT VII, 48]: I must not think that perhaps the things I lack are more difficult to acquire than those now in me. On the contrary, it is evident that it was far more difficult for me—i.e., a thing, or substance, which thinks—to emerge from nothing than, etc. But that would not be consistent with [10] the author’s words and would not be worthy of his genius.

For, to pass over the first consideration, there is nothing in common between the possible and the impossible, or between the intelligible and the unintelligible, just as there is nothing in common between something and nothing; and power does not agree with impossibilities [15] any more than creation and generation do with nonexistent things, so they ought not to be compared in any way. Moreover, I can compare things with one another and know the relation between them only if I have a clear and distinct concept of each of them. Hence I deny that it follows that if someone can do the impossible, he should also be [20] able to do what is possible.

What sort of conclusion is this? If someone can make a square circle, he will also be able to make a circle all of whose radii are equal, or, if someone can bring it about that nothing28 is acted on, and can use it [25] as a material from which to produce something, he will also have the power to make something from some [B: other] thing. As I have said, between these and similar things there is neither agreement, nor proportion, nor comparison, nor anything whatsoever in common. Anyone can see this, if he gives the matter any attention at all. I think [30] Descartes was too intelligent to have meant that.

But when I consider the second axiom of the two just cited, it seems that by greater and more difficult he means more perfect, and by less and easier, more imperfect. But this is also very obscure. There is the [I/163] same difficulty here as before. I deny, as before, that he who can do the greater, should be able at the same time and by the same work (as must be supposed in the Proposition) to do the lesser.

Again, when he says: it is greater to create or preserve a substance than to create or preserve its attributes, he can surely not understand by attributes [5] what is contained formally in substance and is distinguished from substance itself only by reason.29 For then creating a substance is the same as creating its attributes. For the same reason he also cannot understand [by attributes] the properties of a substance which follow necessarily from its essence and definition.

[10] Much less can he understand what he nevertheless seems to mean, viz. the properties and attributes of another substance. So, for example, if I say that I have the power of preserving myself, a finite thinking substance, I cannot on that account say that I also have the power [15] of giving myself the perfections of the infinite substance which differs in its whole essence from my essence. For the power, or essence,e by which I preserve myself in my being differs entirely from the power, or essence, by which the absolutely infinite substance preserves itself, from which its powers and properties are only distinguished by reason. [20] Hence, even though I were to suppose that I preserve myself, if I should wish to conceive that I could give myself the perfections of the absolutely infinite substance, I would be supposing nothing but this—that I can reduce my whole essence to nothing and create afresh an infinite substance. This, of course, would be much greater than [25] only supposing that I can preserve myself, a finite substance.

Since, then, he can understand none of these things by attributes or properties, nothing else remains, except the qualities that the substance [30] itself contains eminently (as, this or that thought in the mind, which I clearly perceive to be lacking in me), but not those another substance contains eminently (as, this or that motion in extension; for such perfections are not perfections for me, a thinking thing, and so are not lacking to me). But then Descartes cannot in any way infer from this axiom the conclusion he wants to demonstrate; i.e., that if I [I/164] preserve myself, I also have the power of giving myself all the perfections that I clearly find to pertain to a supremely perfect being.

This is quite evident from what has just been said. But not to leave the matter undemonstrated, and to avoid all confusion, it seemed best [5] to demonstrate the following lemmas first, and afterwards to construct a demonstration of P7 on that basis.

Lemma 1: The more perfect a thing is by its own nature, the greater and more necessary is the existence it involves; conversely, the more necessary the [10] existence it involves by its own nature, the more perfect it is.

Dem.: Existence is contained in the idea, or concept, of everything (by A6). Let A be a thing that has ten degrees of perfection. I say that [15] its concept involves more existence than it would if it were supposed to contain only five degrees of perfection. For since we can affirm no existence of nothing (see P4S), then the more we take away its perfection [20] in thought, and so the more we conceive it as participating in nothing,30 the more possibility of existence we also deny it. Hence, if we should conceive its degrees of perfection to be diminished infinitely to zero, it will contain no existence, or absolutely impossible existence. On the other hand, if we increase its degree [of perfection] infinitely, [25] we shall conceive it as involving existence in the highest degree, and therefore as involving supremely necessary existence. This was the first thing to be proven.

And the second thing proposed for demonstration follows clearly from the fact that these two things [necessary existence and perfection] cannot be separated in any way (as is sufficiently established by A6, and by this whole first part).

[30] Note 1. Although many things are said to exist necessarily from the mere fact that there is a determinate cause to produce them, we are not speaking about these things here, but only about that necessity and possibility which [I/165] follow solely from the consideration of the nature, or essence, of the thing, without regard to any cause.

Note 2. We are not speaking here about beauty and the other ‘perfections’ which men have wished, in their superstition and ignorance, to call perfections. [5] By perfection I understand only reality, or being. E.g., I perceive that more reality is contained in substance than in modes, or accidents. Hence I understand clearly that it contains a more necessary and perfect existence than accidents do, as is plain enough from A4 and A6.

[10] Cor.: Hence it follows that whatever involves necessary existence is a supremely perfect being, or God.

Lemma 2: The nature of him who has the power of conserving himself involves [15] necessary existence.

Dem.: Whoever has the power to preserve himself also has the power to create himself (by A10), i.e. (as everyone will readily concede), he requires no external cause in order to exist; rather, his own nature [20] alone will be a sufficient cause of his existing, either possibly (see A10) or necessarily. But he does not exist possibly. For then (by what we have demonstrated concerning A10), from the fact that he existed now, it would not follow that he would exist afterwards (which is contrary to the hypothesis). So he exists necessarily, i.e., his nature involves [25] necessary existence, q.e.d.

Demonstration of P7: If I had the power to preserve myself, I would [I/166] be of such a nature that I would involve necessary existence (by L2). So (by L1C) my nature would contain all perfections. But I find in myself, insofar as I am a thinking thing, many imperfections—that I [5] doubt, desire, etc.—of which I am certain (P4S). Therefore, I have no power to preserve myself. I cannot say that the reason I now lack those perfections is that I wish to deny them to myself, for that would clearly be incompatible with L1 and with what I clearly find in myself (by A5).

Next, I cannot now exist without being preserved as long as I exist, [10] either by myself, if in fact I have that power, or by another who has it (by A10 and All). But I exist (by P4S) and nevertheless I do not have the power to preserve myself, as was just now proved. Therefore, I am preserved by another. But not by another who does not have the power to preserve himself (by the same reasoning by which [15] I just demonstrated that I cannot preserve myself). So I am preserved by another who has the power of preserving himself, i.e. (by L2), whose nature involves necessary existence, i.e. (by L1C), who contains all the perfections which I understand to pertain clearly to a supremely [20] perfect being. And therefore a supremely perfect being, i.e. (by D8), God, exists, as was to be demonstrated.

Cor.: God can bring about whatever we clearly perceive, as we perceive it.

[25] Dem.: All these things clearly follow from the preceding Proposition. For it is proved there that God exists from the fact that there must exist someone who has all the perfections of which there is some idea in us. But there is in us the idea of a power so great that the [30] heaven, and the earth, and all the other things which I understand to be possible, can be made, unaided, by him in whom the power exists. [I/167] So all these things have been proved about God together with his existence.

P8: Mind and body are really distinct.

[5] Dem.: Whatever we perceive clearly can be made by God as we perceive it (P7C). But (by P3 and P4) we clearly perceive the mind, i.e. (by D6), a thinking substance, without the body, i.e. (by D7), [10] without any extended substance. Conversely, we perceive the body clearly without mind (as everyone will readily concede). So the mind can exist without the body and the body can exist without the mind—at least by divine power.

Now substances which can exist without one another are really distinct [15] (by D10). But the mind and the body are substances (by D5, 6, and 7), which can each exist without the other (as we have just proven). So the mind and the body are really distinct.

See Descartes’ P4 (at the end of the Replies to the Second Objections) [20] and the Principles I, 22-29. For I do not judge it worthwhile to transcribe here the things said there.31

P9: In the highest degree, God understands.

[25] Dem.: If you deny this, then God will understand either nothing, or not everything, or only certain things.

But to understand only certain things and be ignorant of others supposes a limited and imperfect intellect, which it is absurd to ascribe to God (by D8).

[I/168] But that God should understand nothing would indicate either that he lacks any intellection, as men do when they understand nothing, and so would involve imperfection, which cannot be in God (by D8), or that his understanding something would be incompatible with his perfection.

[5] Since intellection would thus be denied to him altogether, he would not be able to create any intellect (by A8). But since we perceive intellect clearly and distinctly, God can be its cause (P7C). Hence it is not at all true that it is incompatible with God’s perfection for him to understand something.

[10] Consequently, he will, in the highest degree, understand, q.e.d.

Schol.: Although it must be conceded that God is incorporeal, as is demonstrated in P16, still this must not be taken to mean that all the [15] perfections of Extension are to be denied him. Extension is to be rejected only insofar as its nature and properties involve some imperfection. The same thing must also be said about God’s intellection, as everyone who wants to be wiser than the ordinary run of Philosophers [20] confesses. This will be explained fully in our Appendix (II, vii).32

P10: Whatever perfection is found in God, is from God.