EDITORIAL PREFACE

IN JULY 1675 Oldenburg wrote nervously to Spinoza to inquire about the prospect of publication of the Ethics:

From your reply of 5 July I understand that you intend to publish that five-part Treatise of yours. Permit me, I beg you, to advise you, out of your sincere regard for me, not to include in it anything which may seem in any way whatever, to overthrow the practice of religious virtue.… I shall not decline to receive copies of this Treatise; I would only ask that when the time comes, they be sent by way of a certain Dutch merchant, resident in London, who will see that they are soon forwarded. There will be no need to mention that such books have been sent to me.… (Letter 62, IV/273)

Oldenburg need not have worried. Some time later Spinoza sent him the following reply:

When I received your letter of 22 July, I was on the point of leaving for Amsterdam, to see to the printing of the book I wrote you about. While I was occupied with this, a rumor was spread everywhere that a book of mine about God was in the press, and that in it I strove to show that there is no God. Many people believed this rumor. So certain theologians—who had, perhaps, started the rumor themselves—seized this opportunity to complain about me to the Prince and the magistrates. Moreover, the stupid Cartesians, who are thought to favor me, would not stop trying to remove this suspicion from themselves by denouncing my opinions and writings everywhere.

When I learned this from certain trustworthy men, who also told me that the theologians were everywhere plotting against me, I decided to put off the publication I was planning until I saw how the matter would turn out.… But every day it gets worse, and I am uncertain what to do. (Letter 68, IV/299)

Thus was the world deprived, within Spinoza’s lifetime, of one of the great classics of modern philosophical thought, a work, ironically, that begins by arguing at length for God’s existence, and ends with the conclusion that the knowledge and love of God are man’s greatest good.

When Spinoza died, a year and a half later, his work could be published, and the slow process of recognition could begin. But not until he had been taken up by leading figures of the German enlightenment—by Lessing, Goethe, and Herder, among others—did his work receive much sympathetic attention.1 Since then the Ethics has always had a wide audience, particularly—and in view of its technical difficulty and forbidding form, surprisingly—among people not themselves professional philosophers, but poets, dramatists, and novelists.2

Much of this interest no doubt stems from the psychology and morality of the latter parts of the Ethics, from its serene, but remorseless dissection of human nature, and its (apparent) attempt to establish an acceptable ethic on the unpromising foundation of subjectivism, egoism, and determinism.3 But in part the interest must come also from fascination with the difficult question whether we can really regard as religious a thinker who has rejected so forcefully so much of what has usually been regarded as essential to religion in the West.

This is not the place to try to solve the perennial problems of Spinoza’s philosophy. But some attempt must be made here to disarm the resistance which the axiomatic form of his masterwork seems, inevitably, to arouse. The topic is one on which quite divergent views have been expressed.4

Sometimes, for example, it is suggested that Spinoza’s philosophy required axiomatic exposition, that conceiving the world as he did, as a tightly knit deterministic system, he could not properly have expressed this conception in any other way; or that conceiving knowledge as he did, he would have regarded deduction from self-evident premises as the only suitably scientific way of presenting his philosophy. At the opposite extreme, it is sometimes held that the axiomatic exposition is merely a literary device designed to conceal the author’s personality, to capitalize on the prestige of geometry, or even to avoid the temptation to quote Scripture—but having no further significance.

The truth, I suggest, is that Spinoza’s choice of the axiomatic method represents nothing more, and nothing less, than an awesome commitment to intellectual honesty and clarity. Spinoza wishes to use no important term without explaining the sense in which it is to be understood, to make no crucial assumption without identifying it as a proposition taken to require no argument, to draw no conclusion without being very explicit about why that conclusion is thought to follow from his assumptions. This can be very tedious, as he well realizes (cf. E IVP18 S). But the serious reader who is prepared to use those terms as Spinoza does, and who shares Spinoza’s assumptions, is forced to ask himself why he should not also accept Spinoza’s conclusions. And it is only fair to point out that many of Spinoza’s contemporaries did share those assumptions and did use those terms in a way very close to the way Spinoza used them.5

Again, it is a mistake to suppose that, when Spinoza designates something as an axiom, he really thinks that no one could question it, and is not willing to listen to argument about it. The history of his experiments with axiomatic exposition shows clearly enough that he is prepared to be flexible, and that what at one stage is treated as an axiom, may at a later stage be treated as a theorem, if experience shows that his readers resist the assumption.6 He does, of course, think that some propositions are more suited to be axioms than others. But he is not extravagantly optimistic about the ability of his readers to see what they should see, and this gives him a strong incentive to reduce his assumptions to a minimum (cf. II/49/26 ff.). And any serious attempt at argument must make some assumptions which, for the time being, at least, are not questioned.

But while this line of defense may be sound enough, as far as it goes, it does not go far enough. The difficulty for the modern reader of Spinoza’s Ethics is not so much that he finds flaws in the demonstrations (though he may, of course), nor even that he rejects the axioms (though, again, he may), but that much of the language in which the axioms and demonstrations are framed has by now fallen into disuse, so that its very meaning is quite obscure to him. The clarity the axiomatization seemed to promise is not easy to find. A glossary-index may provide a partial solution to this difficulty. But unless it is very argumentative it cannot deal with the really fundamental problem.

It must be recognized that some of the terms which are central to Spinoza’s philosophy are not merely out of fashion in twentieth-century philosophy, but would be rejected by many philosophers of our time as meaningless. The term ‘substance’ is a good example. For many people these days it is axiomatic that the empiricist critique of this concept demonstrated its bankruptcy. (By “axiomatic” I understand here something we learned when we were first introduced to philosophy.)

And yet it is arguable that this rejection has been too hasty: that the traditional use of the concept of substance was too complex to have been disposed of so simply; that there are two distinguishable strains in that use—the concept of an unknowable subject of predicates, and the concept of an independent being; that the empiricist critique touches only the first of these strains; and that only the second is of much importance for the understanding of Spinoza.7 If this is correct and if other contentious concepts can be similarly rehabilitated, Spinoza’s philosophy may once again be ripe for reevaluation.

These reflections may do something to diminish the resistance many readers have to the form of the Ethics. But there remains the practical problem of how even the reader of good will is to cope with a procedure that makes great demands on his patience.

On a first reading it is probably advisable to concentrate on the propositions, corollaries, scholia, prefaces, and appendices, leaving the demonstrations till later. This will make it easier to grasp the structure of the work, and give the reader some feeling for what is central and what is subsidiary. ‘Corollaries’ are often more important than the proposition they follow, and the scholia often offer more intuitive arguments for the propositions just demonstrated, or reply to what Spinoza regards as natural and important objections. The longer scholia, prefaces, and appendices tend to punctuate major divisions within the work and to sum up key contentions.

On a second reading, of course, it is essential to study the demonstrations carefully. Seeing how a proposition is argued for is often a useful way of clarifying its sense. It is also helpful to check the steps of a demonstration against the citations. For when Spinoza cites an axiom, definition, or proposition in a subsequent demonstration, he sometimes paraphrases it in a way that illuminates what has gone before. And in any case, it is instructive to see what Spinoza takes the implications and significance of a proposition to be. But the best advice is Spinoza’s own—to proceed slowly and to abstain from judgment until everything has been read through (IIP11CS). This is not easy. Spinoza’s philosophy is not easy. But as he also says, all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare (VP42S).

I close with a few observations on the probable date of composition of the Ethics and the status of our text. As we have seen, Spinoza took steps to publish this work in 1675, though it did not appear until 1677 and may have undergone some revision even after 1675. On that ground we might regard the Ethics as a late work, or at any rate, later than the Theological-Political Treatise, published in 1670. On the other hand, we can see from the early correspondence with Oldenburg that Spinoza was circulating drafts of the material for Part I as early as 1661. So we might conclude that Spinoza was occupied with writing this work, off and on, for most of his adult life.

Nevertheless, it now seems possible to be more precise than that about the composition of our text. We know from Letter 28 that toward the middle of 1665 Spinoza was near the end of a first draft of the Ethics (i.e., near the end of the third part of what was probably, at that stage, conceived as a three-part work). Recent research on the relation between the OP and NS versions of the Ethics also suggests certain conclusions about the extent of the revision the first two parts may have undergone after 1665.

Gebhardt had noted (II/315-317, 340-345) that divergences between the OP text and NS translation were much more common in the first two parts of the Ethics than they were in the last three, and that frequently the NS seemed to have more text than the OP had. He inferred from this that the NS translation of E I-II was done from a manuscript that represented an earlier draft of the Ethics and that in revising Spinoza had deliberately omitted certain passages, sometimes to avoid giving unnecessary offense.8 He therefore incorporated many passages from the NS translation into his text. Occasionally9 he translated his additions into Latin. One might question whether the editor of a critical edition should interfere with the text in this way, but Gebhardt believed that the practice of modern editors of Kant’s first Critique provided a precedent for indicating (as he thought) the differences between earlier and later drafts.

I believe that Akkerman (2, 77-176) has definitively refuted this theory and shown the correctness of an alternative account of the variations: that the NS translation of E I-II is essentially the work of Balling,10 while the NS translation of E III-V is by Glazemaker; and that the tendency of the NS version of E I-II to show more text than the NS version of E III-V stems from Balling’s different style of translating, in particular his willingness to take greater liberties with the text than Glazemaker would take. Akkerman makes his case for this via a meticulous examination of the translating styles of the two men in other works they are known to have translated, noting differences in prose style, in the kinds of license they allow themselves, in the kinds of mistakes they are apt to make, and in the way they treat key terms. One hesitates to speak of demonstration in any matter such as this, but Akkerman’s argument is very impressive.

The principal implication of his research, as far as the establishment of the text is concerned, is that where the NS seems to have more text than the OP, this is almost invariably because the translator has amplified the text to make it clearer, or used a pair of Dutch terms to render one Latin term, in the hope of better capturing the implications of the Latin, and not because the text he was translating varied from the OP text.

But Akkerman’s research also, it seems to me, has implications for the study of the development of Spinoza’s thought. If Balling was the author of the translation of E I-II used by the editors of the NS, and if no significant changes were made in that text after Balling translated it, then Balling’s death would provide a date after which Spinoza did not significantly revise Parts I and II. We do not know precisely when Balling died. Clearly it was not before July 1664 (the date of Letter 17) and pretty certainly it was not later than 1669 (cf. AHW, 45), Akkerman (2, 152-153) thinks Balling must have died before June 1665, by which date Spinoza was writing to Bouwmeester about the possibility of his translating Part III. If this is correct, then the metaphysical and epistemological portions of the Ethics would have been in their final form some twelve years before they were published.

Gebhardt’s additions to the text from the NS create a problem for the translator. Shirley’s policy is to ignore them when they are in Dutch and to translate them when Gebhardt has translated them into Latin, but without indicating that what he is translating is an addition from the NS. But this seems to assume that Gebhardt has followed some defensible principle in deciding what to add in Dutch and what to add in Latin, an assumption I see no reason to make. In one way or another I have translated everything that Gebhardt adds from the NS (as well as some variations that Gebhardt does not seem to have noticed). Where it has seemed to me that an addition, even though it probably came originally from the NS translator, was pretty certainly correct and useful, I have generally followed Gebhardt in adding it to the text. I assume that a translator may take liberties that the editor of a critical edition may not. Where one of Gebhardt’s additions has seemed to me doubtfully correct, I have relegated it to a footnote. Wherever a bracketed addition comes from the NS, I have indicated that fact. There is some evidence that Spinoza may have had Balling’s translation of E I-II at his disposal, and indeed, that the copy of that translation used by the NS editors may have been Spinoza’s own (cf. Akkerman 2, 167-168). So additions made from the NS, even if they do originate from a translator, may have been seen and approved by Spinoza.

References to definitions, axioms, propositions, etc., that do not contain an explicit reference to an earlier part of the Ethics are to be understood as referring to the part in which they occur.

Ethics

DEMONSTRATED IN GEOMETRIC ORDER AND DIVIDED INTO FIVE PARTS, WHICH TREAT

I. Of God

II. Of the Nature and Origin of the Mind

III. Of the Origin and Nature of the Affects

IV. Of Human Bondage, or of the Powers of the Affects

V. Of the Power of the Intellect, or of Human Freedom1

[II/45] First Part Of the Ethics

On God

DEFINITIONS

[5] D1: By cause of itself I understand that whose essence involves existence, or that whose nature cannot be conceived except as existing.

D2: That thing is said to be finite in its own kind that can be limited by another of the same nature.

[10] For example, a body is called finite because we always conceive another that is greater. Thus a thought is limited by another thought. But a body is not limited by a thought nor a thought by a body.

D3: By substance I understand what is in itself and is conceived through [15] itself, i.e., that whose concept does not require the concept of another thing, from which it must be formed.

D4: By attribute I understand what the intellect perceives of a substance, as constituting its essence.2

[20] D5: By mode I understand the affections of a substance, or that which is in another through which it is also conceived.

D6: By God I understand a being absolutely infinite, i.e., a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, of which each one expresses an3 [25] eternal and infinite essence.

[II/46] Exp.: I say absolutely infinite, not infinite in its own kind; for if something is only infinite in its own kind, we can deny infinite attributes of it [NS: (i.e., we can conceive infinite attributes which do not [5] pertain to its nature)];4 but if something is absolutely infinite, whatever expresses essence and involves no negation pertains to its essence.

D7: That thing is called free which exists from the necessity of its nature alone, and is determined to act by itself alone. But a thing is [10] called necessary, or rather compelled, which is determined by another to exist and to produce an effect in a certain and determinate manner.

D8: By eternity I understand existence itself, insofar as it is conceived [15] to follow necessarily from the definition alone of the eternal thing.

Exp.: For such existence, like the essence of a thing,5 is conceived as an eternal truth, and on that account cannot be explained6 by duration or time, even if the duration is conceived to be without beginning or end.

[20] AXIOMS

A1: Whatever is, is either in itself or in another.

A2: What cannot be conceived through another, must be conceived through itself.

A3: From a given determinate cause the effect follows necessarily; and [25] conversely, if there is no determinate cause, it is impossible for an effect to follow.

A4: The knowledge of an effect depends on, and involves, the knowledge of its cause.

A5: Things that have nothing in common with one another also cannot [30] be understood through one another, or the concept of the one does not involve the concept of the other.

[II/47] A6: A true idea must agree with its object.

A7: If a thing can be conceived as not existing, its essence does not involve existence.

[5] P1: A substance7 is prior in nature to its affections.

Dem.: This is evident from D3 and D5.

P2: Two substances having different attributes have nothing in common with [10] one another.8

Dem.: This also evident from D3. For each must be in itself and be conceived through itself, or the concept of the one does not involve the concept of the other.

[15] P3: If things have nothing in common with one another, one of them cannot be the cause of the other.

Dem.: If they have nothing in common with one another, then (by [20] A5) they cannot be understood through one another, and so (by A4) one cannot be the cause of the other, q.e.d.

P4: Two or more distinct things are distinguished from one another, either by a difference in the attributes of the substances or by a difference in their affections.

[25] Dem.: Whatever is, is either in itself or in another (by A1), i.e. (by D3 and D5), outside the intellect there is nothing except substances and their affections. Therefore, there is nothing outside the intellect [30] through which a number of things can be distinguished from one another [II/48] except substances, or what is the same (by D4), their attributes, and their affections,9 q.e.d.

P5: In nature there cannot be two or more substances of the same nature or [5] attribute.

Dem.: If there were two or more distinct substances, they would have to be distinguished from one another either by a difference in their attributes, or by a difference in their affections (by P4). If only by a difference in their attributes, then it will be conceded that there [10] is only one of the same attribute. But if by a difference in their affections, then since a substance is prior in nature to its affections (by P1), if the affections are put to one side and [the substance] is considered in itself, i.e. (by D3 and A6), considered truly, one cannot be conceived to be distinguished from another, i.e. (by P4), there cannot be [15] many, but only one [of the same nature or attribute],10 q.e.d.

P6: One substance cannot be produced by another substance.

Dem.: In nature there cannot be two substances of the same attribute [20] (by P5), i.e. (by P2), which have something in common with each other. Therefore (by P3) one cannot be the cause of the other, or cannot be produced by the other, q.e.d.

Cor.: From this it follows that a substance cannot be produced by [25] anything else. For in nature there is nothing except substances and their affections, as is evident from A1, D3, and D5. But it cannot be produced by a substance (by P6). Therefore, substance absolutely cannot be produced by anything else, q.e.d.

[30] Alternatively: This11 is demonstrated even more easily from the absurdity of its contradictory. For if a substance could be produced by something else, the knowledge of it would have to depend on the knowledge of its cause (by A4). And so (by D3) it would not be a substance.

[I/49] P7: It pertains to the nature of a substance to exist.

Dem.: A substance cannot be produced by anything else (by P6C); [5] therefore it will be the cause of itself, i.e. (by D1), its essence necessarily involves existence, or it pertains to its nature to exist, q.e.d.

P8: Every substance is necessarily infinite.

[10] Dem.: A substance of one attribute12 does not exist unless it is unique (P5), and it pertains to its nature to exist (P7). Of its nature, therefore, it will exist either as finite or as infinite. But not as finite. For then (by D2) it would have to be limited by something else of the same [15] nature, which would also have to exist necessarily (by P7), and so there would be two substances of the same attribute, which is absurd (by P5). Therefore, it exists as infinite, q.e.d.

Schol. 1: Since being finite is really, in part, a negation, and being [20] infinite is an absolute affirmation of the existence of some nature, it follows from P7 alone that every substance must be infinite. [NS: For if we assumed a finite substance, we would, in part, deny existence to its nature, which (by P7) is absurd.]13

[25] Schol. 2:14 I do not doubt that the demonstration of P7 will be difficult to conceive for all who judge things confusedly, and have not been accustomed to know things through their first causes—because they do not distinguish between the modifications15 of substances and the substances themselves, nor do they know how things are produced. [30] So it happens that they fictitiously ascribe to substances the beginning which they see that natural things have; for those who do not know the true causes of things confuse everything and without any conflict of mind feign that both trees and men speak, imagine that men are formed both from stones and from seed, and that any form [35] whatever is changed into any other.16 So also, those who confuse the divine nature with the human easily ascribe human affects to God, particularly so long as they are also ignorant of how those affects are [II/50] produced in the mind.

But if men would attend to the nature of substance, they would have no doubt at all of the truth of P7. Indeed, this proposition would be an axiom for everyone, and would be numbered among the common notions. For by substance they would understand what is in itself [5] and is conceived through itself, i.e., that the knowledge of which does not require the knowledge of any other thing.17 But by modifications they would understand what is in another, those things whose concept is formed from the concept of the thing in which they are.

This is how we can have true ideas of modifications which do not exist; for though they do not actually exist outside the intellect, nevertheless [10] their essences are comprehended in another in such a way that they can be conceived through it. But the truth of substances is not outside the intellect unless it is in them themselves,18 because they are conceived through themselves.

Hence, if someone were to say that he had a clear and distinct, i.e., true, idea of a substance, and nevertheless doubted whether such a substance existed, that would indeed be the same as if he were to say [15] that he had a true idea, and nevertheless doubted whether it was false (as is evident to anyone who is sufficiently attentive). Or if someone maintains that a substance is created,19 he maintains at the same time that a false idea has become true.20 Of course nothing more absurd can be conceived. So it must be confessed that the existence of a substance, like its essence, is an eternal truth.

[20] And from this we can infer in another way that there is only one [substance] of the same nature, which I have considered it worth the trouble of showing here.21 But to do this in order, it must be noted,

I. that the true definition of each thing neither involves nor expresses anything except the nature of the thing defined.

From which it follows,

II. that no definition involves or expresses any certain number of [25] individuals,[a]

since it expresses nothing other than the nature of the thing defined. E.g., the definition of the triangle expresses nothing but the simple nature of the triangle, but not any certain number of triangles. It is to be noted,

III. that there must be, for each existing thing, a certain cause22 on account of which it exists.

[30] Finally, it is to be noted,

IV. that this cause, on account of which a thing exists, either must be contained in the very nature and definition of the existing thing (viz. that it pertains to its nature to exist) or must be outside it.

From these propositions it follows that if, in nature, a certain number [35] of individuals exists, there must be a cause why those individuals, and [II/51] why neither more nor fewer, exist.

For example, if 20 men exist in nature (to make the matter clearer, I assume that they exist at the same time, and that no others previously existed in nature), it will not be enough (i.e., to give a reason why 20 men exist) [5] to show the cause of human nature in general; but it will be necessary in addition to show the cause why not more and not fewer than 20 exist. For (by III) there must necessarily be a cause why each [NS: particular man] exists. But this cause (by II and III) cannot be contained in human nature itself, since the true definition of man does [10] not involve the number 20. So (by IV) the cause why these 20 men exist, and consequently, why each of them exists, must necessarily be outside each of them.

For that reason it is to be inferred absolutely that whatever is of such a nature that there can be many individuals [of that nature] must, to exist, have an external cause to exist. Now since it pertains to the [15] nature of a substance to exist (by what we have already shown in this Scholium),23 its definition must involve necessary existence, and consequently its existence must be inferred from its definition alone. But from its definition (as we have shown from II and III) the existence of a number of substances cannot follow. Therefore it follows necessarily [20] from this, that there exists only one of the same nature, as was proposed.

P9: The more reality or being each thing has, the more attributes belong to it.

[25] Dem.: This is evident from D4.

P10: Each attribute of a substance must be conceived through itself.

[30] Dem.: For an attribute is what the intellect perceives concerning a substance, as constituting its essence (by D4); so (by D3) it must be conceived through itself, q.e.d.

[II/52] Schol.: From these propositions it is evident that although two attributes may be conceived to be really distinct (i.e., one may be conceived without the aid of the other), we still can not infer from that that they constitute two beings, or two different substances.24 For it [5] is of the nature of a substance that each of its attributes is conceived through itself, since all the attributes it has have always been in it together, and one could not be produced by another, but each expresses the reality, or being of substance.

So it is far from absurd to attribute many attributes to one substance. [10] Indeed, nothing in nature is clearer than that each being must be conceived under some attribute, and the more reality, or being it has, the more it has attributes which express necessity, or eternity, and infinity. And consequently there is also nothing clearer than that [15] a being absolutely infinite must be defined (as we taught in D6) as a being that consists of infinite attributes, each of which expresses a certain eternal and infinite essence.25

But if someone now asks by what sign we shall be able to distinguish the diversity of substances, let him read the following propositions, which show that in Nature there exists only one substance, and [20] that it is absolutely infinite. So that sign would be sought in vain.

P11: God, or a substance consisting of infinite attributes, each of which expresses [25] eternal and infinite essence, necessarily exists.

Dem.: If you deny this, conceive, if you can, that God does not exist. Therefore (by A7) his essence does not involve existence. But this (by P7) is absurd. Therefore God necessarily exists, q.e.d.

[30] Alternatively: For each thing there must be assigned a cause, or reason, as much for its existence as for its nonexistence. For example, if a triangle exists, there must be a reason or cause why it exists; but [II/53] if it does not exist, there must also be a reason or cause which prevents it from existing, or which takes its existence away.

But this reason, or cause, must either be contained in the nature of the thing, or be outside it. E.g., the very nature of a square circle indicates the reason why it does not exist, viz. because it involves a [5] contradiction. On the other hand, the reason why a substance exists also follows from its nature alone, because it involves existence (see P7). But the reason why a circle or triangle exists, or why it does not exist, does not follow from the nature of these things, but from the order of the whole of corporeal Nature. For from this [order] it must follow either that the triangle necessarily exists now or that it is impossible [10] for it to exist now.26

These things are evident through themselves, but from them it follows that a thing necessarily exists if there is no reason or cause which prevents it from existing. Therefore, if there is no reason or cause which prevents God from existing, or which takes his existence away, it must certainly be inferred that he necessarily exists.

[15] But if there were such a reason, or cause, it would have to be either in God’s very nature or outside it, i.e., in another substance of another nature. For if it were of the same nature, that very supposition would concede that God exists. But a substance which was of another nature [NS: than the divine] would have nothing in common with God (by [20] P2), and therefore could neither give him existence nor take it away.27

Since, then, there can be, outside the divine nature, no reason, or, cause which takes away the divine existence, the reason will necessarily have to be in his nature itself, if indeed he does not exist. That is, his nature would involve a contradiction [NS: as in our second Example]. [25] But it is absurd to affirm this of a Being absolutely infinite and supremely perfect. Therefore, there is no cause, or reason, either in God or outside God, which takes his existence away. And therefore, God necessarily exists, q.e.d.

Alternatively: To be able not to exist is to lack power, and conversely, [30] to be able to exist is to have power28 (as is known through itself). So, if what now necessarily exists are only finite beings, then finite beings are more powerful than an absolutely infinite Being. But this, as is known through itself, is absurd. So, either nothing exists or an absolutely infinite Being also exists. But we exist, either in ourselves, or in something else, which necessarily exists (see A1 and P7). [35] Therefore an absolutely infinite Being—i.e. (by D6), God—necessarily exists, q.e.d.

[II/54] Schol.: In this last demonstration I wanted to show God’s existence a posteriori, so that the demonstration would be perceived more easily—but not because God’s existence does not follow a priori from the [5] same foundation. For since being able to exist is power, it follows that the more reality belongs to the nature of a thing, the more powers it has, of itself, to exist. Therefore, an absolutely infinite Being, or God, has, of himself, an absolutely infinite power of existing. For that reason, he exists absolutely.

Still, there may be many who will not easily be able to see how [10] evident this demonstration is, because they have been accustomed to contemplate only those things that flow from external causes. And of these, they see that those which quickly come to be, i.e., which easily exist,29 also easily perish. And conversely, they judge that those things to which they conceive more things to pertain are more difficult to do, [15] i.e., that they do not exist so easily.30 But to free them from these prejudices, I have no need to show here in what manner this proposition—what quickly comes to be, quickly perishes—is true, nor whether or not all things are equally easy in respect to the whole of Nature. It is sufficient to note only this, that I am not here speaking of things that come to be from external causes, but only of substances that (by P6) [20] can be produced by no external cause.

For things that come to be from external causes—whether they consist of many parts or of few—owe all the perfection or reality they have to the power of the external cause; and therefore their existence arises only from the perfection of their external cause, and not from their own perfection. On the other hand, whatever perfection substance [25] has is not owed to any external cause. So its existence must follow from its nature alone; hence its existence is nothing but its essence.

Perfection, therefore, does not take away the existence of a thing, but on the contrary asserts it. But imperfection takes it away. So there is nothing of whose existence we can be more certain than we are of [30] the existence of an absolutely infinite, or perfect, Being—i.e., God. For since his essence excludes all imperfection, and involves absolute perfection, by that very fact it takes away every cause of doubting his existence, and gives the greatest certainty concerning it. I believe this will be clear even to those who are only moderately attentive.

[II/55] P12: No attribute of a substance can be truly conceived from which it follows that the substance can be divided.

[5] Dem.: For the parts into which a substance so conceived would be divided either will retain the nature of the substance or will not. If the first [NS: viz. they retain the nature of the substance], then (by P8) each part will have to be infinite, and (by P7)31 its own cause, and (by P5) each part will have to consist of a different attribute. And so [10] many substances will be able to be formed from one, which is absurd (by P6). Furthermore, the parts (by P2) would have nothing in common with their whole, and the whole (by D4 and P10) could both be and be conceived without its parts, which is absurd, as no one will be able to doubt.

[15] But if the second is asserted, viz. that the parts will not retain the nature of substance, then since the whole substance would be divided into equal parts,32 it would lose the nature of substance, and would cease to be, which (by P7) is absurd.

[20] P13: A substance which is absolutely infinite is indivisible.

Dem.: For if it were divisible, the parts into which it would be divided will either retain the nature of an absolutely infinite substance or they will not. If the first, then there will be a number of substances [26] of the same nature, which (by P5) is absurd. But if the second is asserted, then (as above [NS: P12]), an absolutely infinite substance will be able to cease to be, which (by P11) is also absurd.

Cor.: From these [propositions] it follows that no substance, and consequently no corporeal substance, insofar as it is a substance,33 is [30] divisible.

Schol.: That substance is indivisible, is understood more simply merely from this, that the nature of substance cannot be conceived unless as infinite, and that by a part of substance nothing can be [II/56] understood except a finite substance, which (by P8) implies a plain contradiction.

P14: Except God, no substance can be or be conceived.

[5] Dem.: Since God is an absolutely infinite being, of whom no attribute which expresses an essence of substance can be denied (by D6), and he necessarily exists (by P11), if there were any substance except God, it would have to be explained through some attribute of God, [10] and so two substances of the same attribute would exist, which (by P5) is absurd. And so except God, no substance can be or, consequently, be conceived. For if it could be conceived, it would have to be conceived as existing. But this (by the first part of this demonstration) is absurd. Therefore, except for God no substance can be or be [15] conceived, q.e.d.

Cor. 1: From this it follows most clearly, first, that God is unique,34 i.e. (by D6), that in Nature there is only one substance, and that it is absolutely infinite (as we indicated in P10S).

[20] Cor. 2: It follows, second, that an extended thing and a thinking thing are either attributes of God, or (by A1) affections of God’s attributes.

[25] P15: Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can be or be conceived without God.

Dem.: Except for God, there neither is, nor can be conceived, any substance (by P14), i.e. (by D3), thing that is in itself and is conceived through itself. But modes (by D5) can neither be nor be conceived [30] without substance. So they can be in the divine nature alone, and can be conceived through it alone. But except for substances and modes [II/57] there is nothing (by A1). Therefore, [NS: everything is in God and] nothing can be or be conceived without God, q.e.d.

Schol.: [I.]35 There are those who feign a God, like man, consisting [5] of a body and a mind, and subject to passions. But how far they wander from the true knowledge of God, is sufficiently established by what has already been demonstrated. Them I dismiss. For everyone who has to any extent contemplated the divine nature denies that God is corporeal. They prove this best from the fact that by body we [10] understand any quantity, with length, breadth, and depth, limited by some certain figure. Nothing more absurd than this can be said of God, viz. of a being absolutely infinite.

But meanwhile, by the other arguments by which they strive to demonstrate this same conclusion they clearly show that they entirely remove corporeal, or extended,36 substance itself from the divine nature. And they maintain that it has been created by God. But by what [15] divine power could it be created? They are completely ignorant of that. And this shows clearly that they do not understand what they themselves say.

At any rate, I have demonstrated clearly enough—in my judgment, at least—that no substance can be produced or created by any other (see P6C and P8S2). Next, we have shown (P14) that except for God, [20] no substance can either be or be conceived, and hence [in P14C2]37 we have concluded that extended substance is one of God’s infinite attributes. But to provide a fuller explanation, I shall refute my opponents’ arguments, which all reduce to these.

[25] [II.] First, they think that corporeal substance, insofar as it is substance, consists of parts. And therefore they deny that it can be infinite, and consequently, that it can pertain to God. They explain this by many examples, of which I shall mention one or two.38

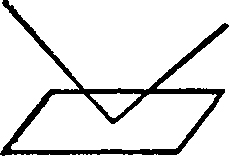

[i] If corporeal substance is infinite, they say, let us conceive it to be divided in two parts.39 Each part will be either finite or infinite. If [30] the former, then an infinite is composed of two finite parts, which is absurd. If the latter [NS: i.e., if each part is infinite], then there is one infinite twice as large as another, which is also absurd, [ii] Again, if an infinite quantity is measured by parts [each] equal to a foot, it [35] will consist of infinitely many such parts, as it will also, if it is measured by parts [each] equal to an inch. And therefore, one infinite number will be twelve times greater than another [NS: which is no less absurd], [iii] Finally, if we conceive that from one point of a certain [II/58] infinite quantity two lines, say AB and AC, are extended to infinity, it is certain that, although in the beginning they are a certain, determinate distance [5] apart, the distance between B and C is continuously increased, and at last, from being determinate, it will become indeterminable. Since these absurdities follow—so they think—from the fact that an infinite quantity is supposed, they infer that corporeal substance must be finite, and consequently cannot pertain to God’s essence.

[10] [III.] Their second argument is also drawn from God’s supreme perfection. For God, they say, since he is a supremely perfect being, cannot be acted on. But corporeal substance, since it is divisible, can be acted on. It follows, therefore, that it does not pertain to God’s essence.40

[IV.] These are the arguments which I find authors using, to try to [15] show that corporeal substance is unworthy of the divine nature, and cannot pertain to it. But anyone who is properly attentive will find that I have already replied to them, since these arguments are founded only on their supposition that corporeal substance is composed of parts, which I have already (P12 and P13C) shown to be absurd. And then [20] anyone who wishes to consider the matter rightly will see that all those absurdities (if indeed they are all absurd, which I am not now disputing), from which they wish to infer that extended substance is finite, do not follow at all from the fact that an infinite quantity is supposed, but from the fact that they suppose an infinite quantity to be measurable [25] and composed of finite parts. So from the absurdities which follow from that they can infer only that infinite quantity is not measurable, and that it is not composed of finite parts. This is the same thing we have already demonstrated above (P12, etc.). So the weapon they aim at us, they really turn against themselves.

[30] If, therefore, they still wish to infer from this absurdity of theirs that extended substance must be finite, they are indeed doing nothing more than if someone feigned that a circle has the properties of a square, and inferred from that the circle has no center, from which all lines drawn to the circumference are equal. For corporeal substance, [35] which cannot be conceived except as infinite, unique, and indivisible [II/59] (see P8, 5 and 12), they conceive to be composed of finite parts, to be many, and to be divisible, in order to infer that it is finite.

So also others, after they feign that a line is composed of points, [5] know how to invent many arguments, by which they show that a line cannot be divided to infinity. And indeed it is no less absurd to assert that corporeal substance is composed of bodies, or parts, than that a body is composed of surfaces, the surfaces of lines, and the lines, finally, of points.

[10] All those who know that clear reason is infallible must confess this—particularly those who deny that there is a vacuum. For if corporeal substance could be so divided that its parts were really distinct, why, then, could one part not be annihilated, the rest remaining connected with one another as before? And why must they all be so fitted together that there is no vacuum? Truly, of things which are really [15] distinct from one another, one can be, and remain in its condition, without the other. Since, therefore, there is no vacuum in nature (a subject I discuss elsewhere),41 but all its parts must so concur that there is no vacuum, it follows also that they cannot be really distinguished, i.e., that corporeal substance, insofar as it is a substance, cannot be divided.

[20] [V.] If someone should now ask why we are, by nature, so inclined to divide quantity, I shall answer that we conceive quantity in two ways: abstractly, or superficially,42 as we [NS: commonly] imagine it, or as substance, which is done by the intellect alone [NS: without the [25] help of the imagination]. So if we attend to quantity as it is in the imagination, which we do often and more easily, it will be found to be finite, divisible, and composed of parts; but if we attend to it as it is in the intellect, and conceive it insofar as it is a substance, which happens [NS: seldom and] with great difficulty, then (as we have already sufficiently demonstrated) it will be found to be infinite, unique, [30] and indivisible.

This will be sufficiently plain to everyone who knows how to distinguish between the intellect and the imagination—particularly if it is also noted that matter is everywhere the same, and that parts are distinguished in it only insofar as we conceive matter to be affected in different ways, so that its parts are distinguished only modally, but [35] not really.

[II/60] For example, we conceive that water is divided and its parts separated from one another—insofar as it is water, but not insofar as it is corporeal substance. For insofar as it is substance, it is neither separated nor divided. Again, water, insofar as it is water, is generated and corrupted, but insofar as it is substance, it is neither generated nor corrupted.

[5] [VI.] And with this I think I have replied to the second argument also, since it is based on the supposition that matter, insofar as it is substance, is divisible, and composed of parts. Even if this [reply] were not [sufficient], I do not know why [divisibility] would be unworthy of the divine nature. For (by P14) apart from God there can [10] be no substance by which [the divine nature] would be acted on. All things, I say, are in God, and all things that happen, happen only through the laws of God’s infinite nature and follow (as I shall show) from the necessity of his essence. So it cannot be said in any way that God is acted on by another, or that extended substance is unworthy of the divine nature, even if it is supposed to be divisible, so long as [15] it is granted to be eternal and infinite. But enough of this for the present.

P16: From the necessity of the divine nature there must follow infinitely many things in infinitely many modes,43 (i.e., everything which can fall under an infinite intellect.)44

[20] Dem.: This Proposition must be plain to anyone, provided he attends to the fact that the intellect infers from the given definition of any thing a number of properties that really do follow necessarily from it (i.e., from the very essence of the thing); and that it infers more [25] properties the more the definition of the thing expresses reality, i.e., the more reality the essence of the defined thing involves. But since the divine nature has absolutely infinite attributes (by D6), each of which also expresses an essence infinite in its own kind, from its necessity there must follow infinitely many things in infinite modes (i.e., [30] everything which can fall under an infinite intellect), q.e.d.

Cor. 1: From this it follows that God is the efficient cause of all things which can fall under an infinite intellect.

[II/61] Cor. 2: It follows, secondly, that God is a cause through himself and not an accidental cause.45

Cor. 3: It follows, thirdly, that God is absolutely the first cause.

[5] P17: God acts from the laws of his nature alone, and is compelled by no one.

Dem.: We have just shown (P16) that from the necessity of the divine nature alone, or (what is the same thing) from the laws of his [10] nature alone, absolutely infinite things follow, and in P15 we have demonstrated that nothing can be or be conceived without God, but that all things are in God. So there can be nothing outside him by which he is determined or compelled to act. Therefore, God acts from [15] the laws of his nature alone, and is compelled by no one, q.e.d.

Cor. 1: From this it follows, first, that there is no cause, either extrinsically or intrinsically, which prompts God to action, except the [20] perfection of his nature.46

Cor. 2: It follows, secondly, that God alone is a free cause. For God alone exists only from the necessity of his nature (by P11 and P14C1), and acts from the necessity of his nature (by P17). Therefore (by D7) [25] God alone is a free cause, q.e.d.

Schol.: [I.] Others47 think that God is a free cause because he can (so they think) bring it about that the things which we have said follow from his nature (i.e., which are in his power) do not happen or are not [30] produced by him. But this is the same as if they were to say that God can bring it about that it would not follow from the nature of a triangle that its three angles are equal to two right angles; or that from a given [II/62] cause the effect would not follow—which is absurd.

Further, I shall show later, without the aid of this Proposition, that neither intellect nor will pertain to God’s nature. Of course I know there are many who think they can demonstrate that a supreme intellect [5] and a free will pertain to God’s nature. For they say they know nothing they can ascribe to God more perfect than what is the highest perfection in us.

Moreover, even if they conceive God to actually understand in the highest degree, they still do not believe that he can bring it about that all the things he actually understands exist. For they think that in that [10] way they would destroy God’s power. If he had created all the things in his intellect (they say), then he would have been able to create nothing more, which they believe to be incompatible with God’s omnipotence. So they preferred to maintain that God is indifferent to all things, not creating anything except what he has decreed to create by some absolute will.

[15] But I think I have shown clearly enough (see P16) that from God’s supreme power, or infinite nature, infinitely many things in infinitely many modes, i.e., all things, have necessarily flowed, or always follow, by the same necessity and in the same way as from the nature of a triangle it follows, from eternity and to eternity, that its three angles are equal to two right angles. So God’s omnipotence48 has been actual [20] from eternity and will remain in the same actuality to eternity. And in this way, at least in my opinion, God’s omnipotence is maintained far more perfectly.

Indeed—to speak openly—my opponents seem to deny God’s omnipotence. For they are forced to confess that God understands infinitely many creatable things, which nevertheless he will never be able [25] to create. For otherwise, if he created everything he understood [NS: to be creatable] he would (according to them) exhaust his omnipotence and render himself imperfect. Therefore to maintain that God is perfect, they are driven to maintain at the same time that he cannot bring about everything to which his power extends. I do not see what could be feigned which would be more absurd than this or more contrary to [30] God’s omnipotence.

[II.] Further—to say something here also about the intellect and will which we commonly attribute to God—if will and intellect do pertain to the eternal essence of God,49 we must of course understand by each of these attributes something different from what men commonly understand. [35] For the intellect and will which would constitute God’s essence [II/63] would have to differ entirely from our intellect and will, and could not agree with them in anything except the name. They would not agree with one another any more than do the dog that is a heavenly constellation and the dog that is a barking animal. I shall demonstrate this.

If intellect pertains to the divine nature, it will not be able to be [5] (like our intellect) by nature either posterior to (as most would have it), or simultaneous with, the things understood, since God is prior in causality to all things (by P16C1). On the contrary, the truth and formal essence of things is what it is because it exists objectively in that way in God’s intellect.50 So God’s intellect, insofar as it is conceived [10] to constitute God’s essence, is really the cause both of the essence and of the existence of things. This seems also to have been noticed by those who asserted that God’s intellect, will and power are one and the same.

Therefore, since God’s intellect is the only cause of things (viz. as [15] we have shown, both of their essence and of their existence), he must necessarily differ from them both as to his essence and as to his existence. For what is caused differs from its cause precisely in what it has from the cause [NS: for that reason it is called the effect of such a cause].51 E.g., a man is the cause of the existence of another man, but not of his essence, for the latter is an eternal truth. Hence, they can [20] agree entirely according to their essence. But in existing they must differ. And for that reason, if the existence of one perishes, the other’s existence will not thereby perish. But if the essence of one could be destroyed, and become false, the other’s essence would also be destroyed [NS: and become false].

So the thing that is the cause both of the essence and of the existence [25] of some effect, must differ from such an effect, both as to its essence and as to its existence. But God’s intellect is the cause both of the essence and of the existence of our intellect. Therefore, God’s intellect, insofar as it is conceived to constitute the divine essence, differs from our intellect both as to its essence and as to its existence, [30] and cannot agree with it in anything except in name, as we supposed. The proof proceeds in the same way concerning the will, as anyone can easily see.

P18: God is the immanent, not the transitive, cause of all things.

[II/64] Dem.: Everything that is, is in God, and must be conceived through God (by P15), and so (by P16C1) God is the cause of [NS: all] things, which are in him. That is the first [thing to be proven]. And then [5] outside God there can be no substance (by P14), i.e. (by D3), thing which is in itself outside God. That was the second. God, therefore, is the immanent, not the transitive cause of all things,52 q.e.d.

P19: God is eternal, or all God’s attributes are eternal.

[10] Dem.: For God (by D6) is substance, which (by P11) necessarily exists, i.e. (by P7), to whose nature it pertains to exist, or (what is the same) from whose definition it follows that he exists; and therefore (by D8), he is eternal.

[15] Next, by God’s attributes are to be understood what (by D4) expresses an essence of the Divine substance, i.e., what pertains to substance. The attributes themselves, I say, must involve it itself. But eternity pertains to the nature of substance (as I have already demonstrated from P7). Therefore each of the attributes must involve eternity, [20] and so, they are all eternal, q.e.d.

Schol.: This Proposition is also as clear as possible from the way I have demonstrated God’s existence (P11). For from that demonstration, I say, it is established that God’s existence, like his essence, is an eternal truth. And then I have also demonstrated God’s eternity in [25] another way (Descartes’ Principles IP19), and there is no need to repeat it here.

P20: God’s existence and his essence are one and the same.

[30] Dem.: God (by P19) and all of his attributes are eternal, i.e. (by D8), each of his attributes expresses existence. Therefore, the same attributes of God which (by D4) explain God’s eternal essence at the [35] same time explain his eternal existence, i.e., that itself which constitutes [II/65] God’s essence at the same time constitutes his existence. So his existence and his essence are one and the same, q.e.d.

Cor. 1: From this it follows, first, that God’s existence, like his [5] essence, is an eternal truth.

Cor. 2: It follows, secondly, that God, or all of God’s attributes, are immutable. For if they changed as to their existence, they would also (by P20) change as to their essence, i.e. (as is known through itself), [10] from being true become false, which is absurd.

P21: All the things which follow from the absolute nature of any of God’s attributes have always53 had to exist and be infinite, or are, through the same attribute, eternal and infinite.

[15] Dem.: If you deny this, then conceive (if you can) that in some attribute of God there follows from its absolute nature something that is finite and has a determinate existence, or duration, e.g., God’s idea54 in thought. Now since thought is supposed to be an attribute of God, [20] it is necessarily (by P11) infinite by its nature. But insofar as it has God’s idea, [thought] is supposed to be finite. But (by D2) [thought] cannot be conceived to be finite unless it is determined through thought itself. But [thought can] not [be determined] through thought itself, insofar as it constitutes God’s idea, for to that extent [thought] is supposed to be finite. Therefore, [thought must be determined] through [25] thought insofar as it does not constitute God’s idea, which [thought] nevertheless (by P11) must necessarily exist. Therefore, there is thought55 which does not constitute God’s idea, and on that account God’s idea does not follow necessarily from the nature [of this thought] insofar as it is absolute thought (for [thought] is conceived both as constituting God’s idea and as not constituting it). [That God’s idea does not follow from thought, insofar as it is absolute thought] is contrary to the hypothesis. [30] So if God’s idea in thought, or anything else in any attribute of God (for it does not matter what example is taken, since the demonstration is universal), follows from the necessity of the absolute nature of the attribute itself, it must necessarily be infinite. This was the first thing to be proven.

Next, what follows in this way from the necessity of the nature of [II/66] any attribute cannot have a determinate [NS: existence, or] duration. For if you deny this, then suppose there is, in some attribute of God, a thing which follows from the necessity of the nature of that attribute—e.g., God’s idea in thought—and suppose that at some time [this [5] idea] did not exist or will not exist. But since thought is supposed to be an attribute of God, it must exist necessarily and be immutable56 (by P11 and P20C2). So beyond the limits of the duration of God’s idea (for it is supposed that at some time [this idea] did not exist or will not exist) thought will have to exist without God’s idea. But this is contrary to the hypothesis, for it is supposed that God’s idea follows [10] necessarily from the given thought. Therefore, God’s idea in thought, or anything else which follows necessarily from the absolute nature of some attribute of God, cannot have a determinate duration, but through the same attribute is eternal. This was the second thing [NS: to be proven]. Note that the same is to be affirmed of any thing which, in [15] some attribute of God, follows necessarily from God’s absolute nature.

P22: Whatever follows from some attribute of God insofar as it is modified by a modification which, through the same attribute, exists necessarily and is [20] infinite, must also exist necessarily and be infinite.57

Dem.: The demonstration of this proposition proceeds in the same way as the demonstration of the preceding one.

[25] P23: Every mode which exists necessarily and is infinite has necessarily had to follow either from the absolute nature of some attribute of God, or from some attribute, modified by a modification which exists necessarily and is infinite.

[30] Dem.: For a mode is in another, through which it must be conceived (by D5), i.e. (by P15), it is in God alone, and can be conceived [II/67] through God alone. So if a mode is conceived to exist necessarily and be infinite, [its necessary existence and infinitude] must necessarily be inferred, or perceived through some attribute of God, insofar as that attribute is conceived to express infinity and necessity of existence, or [5] (what is the same, by D8) eternity, i.e. (by D6 and P19), insofar as it is considered absolutely. Therefore, the mode, which exists necessarily and is infinite, has had to follow from the absolute nature of some attribute of God—either immediately (see P21) or by some mediating modification, which follows from its absolute nature, i.e. (by P22), [10] which exists necessarily and is infinite, q.e.d.

P24: The essence of things produced by God does not involve existence.

Dem.: This is evident from D1. For that whose nature involves [15] existence (considered in itself), is its own cause, and exists only from the necessity of its nature.

Cor.: From this it follows that God is not only the cause of things’ beginning to exist, but also of their persevering in existing, or (to use [20] a Scholastic term) God is the cause of the being of things. For—whether the things [NS: produced] exist or not—so long as we attend to their essence, we shall find that it involves neither existence nor duration. So their essence can be the cause neither of their existence nor of their duration, but only God, to whose nature alone it pertains to exist [25] [,can be the cause] (by P14C1).

P25: God is the efficient cause, not only of the existence of things, but also of their essence.

[30] Dem.: If you deny this, then God is not the cause of the essence of things; and so (by A4) the essence of things can be conceived without [II/68] God. But (by P15) this is absurd. Therefore God is also the cause of the essence of things, q.e.d.

Schol.: This Proposition follows more clearly from P16. For from [5] that it follows that from the given divine nature both the essence of things and their existence must necessarily be inferred; and in a word, God must be called the cause of all things in the same sense in which he is called the cause of himself. This will be established still more clearly from the following corollary.

[10] Cor.: Particular things are nothing but affections of God’s attributes, or modes by which God’s attributes are expressed in a certain and determinate way. The demonstration is evident from P15 and D5.

[15] P26: A thing which has been determined to produce an effect has necessarily been determined in this way by God; and one which has not been determined by God cannot determine itself to produce an effect.

Dem.: That through which things are said to be determined to produce [20] an effect must be something positive (as is known through itself). And so, God, from the necessity of his nature, is the efficient cause both of its essence and of its existence (by P25 & 16); this was the first thing. And from it the second thing asserted also follows very clearly. For if a thing which has not been determined by God could determine itself, the first part of this [NS: proposition] would be false, which is [25] absurd, as we have shown.

P27: A thing which has been determined by God to produce an effect, cannot render itself undetermined.

[30] Dem.: This proposition is evident from A3.

[II/69] P28: Every singular thing, or any thing which is finite and has a determinate existence, can neither exist nor be determined to produce an effect unless it is [5] determined to exist and produce an effect by another cause, which is also finite and has a determinate existence; and again, this cause also can neither exist nor be determined to produce an effect unless it is determined to exist and produce an effect by another, which is also finite and has a determinate existence, and so on, to infinity.58

[10] Dem.: Whatever has been determined to exist and produce an effect has been so determined by God (by P26 and P24C). But what is finite and has a determinate existence could not have been produced by the absolute nature of an attribute of God; for whatever follows from the [15] absolute nature of an attribute of God is eternal and infinite (by P21). It had, therefore, to follow either from God or from an attribute of God insofar as it is considered to be affected by some mode. For there is nothing except substance and its modes (by A1, D3, and D5) and [20] modes (by P25C) are nothing but affections of God’s attributes. But it also could not follow from God, or from an attribute of God, insofar as it is affected by a modification which is eternal and infinite (by P22). It had, therefore, to follow from, or be determined to exist and produce an effect by God or an attribute of God insofar as it is modified [25] by a modification which is finite and has a determinate existence. This was the first thing to be proven.

And in turn, this cause, or this mode (by the same reasoning by which we have already demonstrated the first part of this proposition) had also to be determined by another, which is also finite and has a determinate existence; and again, this last (by the same reasoning) by [30] another, and so always (by the same reasoning) to infinity, q.e.d.

[II/70] Schol.: Since certain things had to be produced by God immediately, viz. those which follow necessarily from his absolute nature, and others (which nevertheless can neither be nor be conceived without God) had to be produced by the mediation of these first things,59 it follows:

[5] I. That God is absolutely the proximate cause of the things produced immediately by him, and not [a proximate cause] in his own kind, as they say.60 For God’s effects can neither be nor be conceived without their cause (by P15 and P24C).

II. That God cannot properly be called the remote cause of singular [10] things, except perhaps so that we may distinguish them from those things that he has produced immediately, or rather, that follow from his absolute nature. For by a remote cause we understand one which is not conjoined in any way with its effect. But all things that are, are in God, and so depend on God that they can neither be nor be conceived [15] without him.

P29: In nature there is nothing contingent, but all things have been determined from the necessity of the divine nature to exist and produce an effect in a certain way.

[20] Dem.: Whatever is, is in God (by P15); but God cannot be called a contingent thing. For (by P11) he exists necessarily, not contingently. Next, the modes of the divine nature have also followed from it necessarily and not contingently (by P16)—either insofar as the divine [25] nature is considered absolutely (by P21) or insofar as it is considered to be determined to act in a certain way (by P28).61 Further, God is the cause of these modes not only insofar as they simply exist (by P24C), but also (by P26) insofar as they are considered to be determined [30] to produce an effect. For if they have not been determined by God, then (by P26) it is impossible, not contingent, that they should [II/71] determine themselves. Conversely (by P27) if they have been determined by God, it is not contingent, but impossible, that they should render themselves undetermined. So all things have been determined from the necessity of the divine nature, not only to exist, but to exist in a certain way, and to produce effects in a certain way. There is nothing contingent, q.e.d.

[5] Schol.: Before I proceed further, I wish to explain here—or rather to advise [the reader]—what we must understand by Natura naturans and Natura naturata. For from the preceding I think it is already established that by Natura naturans we must understand what is in itself [10] and is conceived through itself, or such attributes of substance as express an eternal and infinite essence, i.e. (by P14C1 and P17C2), God, insofar as he is considered as a free cause.

But by Natura naturata I understand whatever follows from the necessity of God’s nature, or from any of God’s attributes, i.e., all the [15] modes of God’s attributes insofar as they are considered as things which are in God, and can neither be nor be conceived without God.

P30: An actual intellect, whether finite or infinite,62 must comprehend God’s attributes and God’s affections, and nothing else.

[20] Dem.: A true idea must agree with its object (by A6), i.e. (as is known through itself), what is contained objectively in the intellect must necessarily be in nature. But in nature (by P14C1) there is only one substance, viz. God, and there are no affections other than those [25] which are in God (by P15) and which can neither be nor be conceived without God (by P15). Therefore, an actual intellect, whether finite or infinite, must comprehend God’s attributes and God’s affections, and nothing else, q.e.d.

[30] P31: The actual intellect, whether finite or infinite, like will, desire, love, etc., must be referred to Natura naturata, not to Natura naturans.63

[II/72] Dem.: By intellect (as is known through itself) we understand not absolute thought, but only a certain mode of thinking, which mode differs from the others, such as desire, love, etc., and so (by D5) must [5] be conceived through absolute thought, i.e. (by P15 and D6), it must be so conceived through an attribute of God, which expresses the eternal and infinite essence of thought, that can neither be nor be conceived without [that attribute]; and so (by P29S), like the other modes of thinking, it must be referred to Natura naturata, not to Natura [10] naturans, q.e.d.

Schol.: The reason why I speak here of actual intellect is not because I concede that there is any potential intellect, but because, wishing to avoid all confusion, I wanted to speak only of what we perceive [15] as clearly as possible, i.e., of the intellection itself. We perceive nothing more clearly than that. For we can understand nothing that does not lead to more perfect knowledge of the intellection.

[20] P32: The will cannot be called a free cause, but only a necessary one.

Dem.: The will, like the intellect,64 is only a certain mode of thinking. And so (by P28) each volition can neither exist nor be determined to produce an effect unless it is determined by another cause, and this [25] cause again by another, and so on, to infinity. Even if the will be supposed to be infinite,65 it must still be determined to exist and produce an effect by God, not insofar as he is an absolutely infinite substance, but insofar as he has an attribute that expresses the infinite and eternal essence of thought (by P23). So in whatever way it is [30] conceived, whether as finite or as infinite, it requires a cause by which it is determined to exist and produce an effect. And so (by D7) it cannot be called a free cause, but only a necessary or compelled one, q.e.d.

[II/73] Cor. 1: From this it follows, first, that God does not produce any effect by freedom of the will.

Cor. 2: It follows, secondly, that will and intellect are related to [5] God’s nature as motion and rest are, and as are absolutely all natural things, which (by P29) must be determined by God to exist and produce an effect in a certain way. For the will, like all other things, requires a cause by which it is determined to exist and produce an effect in a certain way. And although from a given will, or intellect [10] infinitely many things may follow, God still cannot be said, on that account, to act from freedom of the will, any more than he can be said to act from freedom of motion and rest on account of those things that follow from motion and rest (for infinitely many things also follow from motion and rest). So will does not pertain to God’s nature any more than do the other natural things, but is related to him in the [15] same way as motion and rest, and all the other things which, as we have shown, follow from the necessity of the divine nature and are determined by it to exist and produce an effect in a certain way.

P33: Things could have been produced by God in no other way, and in no [20] other order than they have been produced.

Dem.: For all things have necessarily followed from God’s given nature (by P16), and have been determined from the necessity of God’s nature to exist and produce an effect in a certain way (by P29). Therefore, [25] if things could have been of another nature, or could have been determined to produce an effect in another way, so that the order of Nature was different, then God’s nature could also have been other than it is now, and therefore (by P11) that [other nature] would also have had to exist, and consequently, there could have been two or more Gods, which is absurd (by P14C1). So things could have been [30] produced in no other way and no other order, etc., q.e.d.

[II/74] Schol. 1: Since by these propositions I have shown more clearly than the noon light that there is absolutely nothing in things on account of which they can be called contingent, I wish now to explain briefly what we must understand by contingent—but first, what [we [5] must understand] by necessary and impossible.

A thing is called necessary either by reason of its essence or by reason of its cause. For a thing’s existence follows necessarily either from its essence and definition or from a given efficient cause. And a thing is also called impossible from these same causes—viz. either because [10] its essence, or definition, involves a contradiction, or because there is no external cause which has been determined to produce such a thing.

But a thing is called contingent only because of a defect of our knowledge. For if we do not know that the thing’s essence involves a contradiction, or if we do know very well that its essence does not [15] involve a contradiction, and nevertheless can affirm nothing certainly about its existence, because the order of causes is hidden from us, it can never seem to us either necessary or impossible. So we call it contingent or possible.66

[20] Schol. 2: From the preceding it clearly follows that things have been produced by God with the highest perfection, since they have followed necessarily from a given most perfect nature. Nor does this convict God of any imperfection, for his perfection compels us to affirm this. Indeed, from the opposite, it would clearly follow (as I [25] have just shown), that God is not supremely perfect; because if things had been produced by God in another way, we would have to attribute to God another nature, different from that which we have been compelled to attribute to him from the consideration of the most perfect Being.

Of course, I have no doubt that many will reject this opinion as [30] absurd, without even being willing to examine it—for no other reason than because they have been accustomed to attribute another freedom to God, far different from that we have taught (D7), viz. an absolute will. But I also have no doubt that, if they are willing to reflect on the matter, and consider properly the chain of our demonstrations, in the [II/75] end they will utterly reject the freedom they now attribute to God, not only as futile, but as a great obstacle to science. Nor is it necessary for me to repeat here what I said in P17S.

Nevertheless, to please them, I shall show that even if it is conceded [5] that will pertains to God’s essence,67 it still follows from his perfection that things could have been created by God in no other way or order. It will be easy to show this if we consider, first, what they themselves concede, viz. that it depends on God’s decree and will alone that each thing is what it is. For otherwise God would not be the cause of all [10] things. Next, that all God’s decrees have been established by God himself from eternity. For otherwise he would be convicted of imperfection and inconstancy. But since, in eternity, there is neither when, nor before, nor after, it follows, from God’s perfection alone, that he can never decree anything different, and never could have, or that God [15] was not before his decrees, and cannot be without them.

But they will say that even if it were supposed that God had made another nature of things, or that from eternity he had decreed something else concerning nature and its order, no imperfection in God would follow from that.

Still, if they say this, they will concede at the same time that God [20] can change his decrees. For if God had decreed, concerning nature and its order, something other than what he did decree, i.e., had willed and conceived something else concerning nature, he would necessarily have had an intellect other than he now has, and a will other than he now has. And if it is permitted to attribute to God another intellect and another will, without any change of his essence and of [25] his perfection, why can he not now change his decrees concerning created things, and nevertheless remain equally perfect? For his intellect and will concerning created things and their order are the same in respect to his essence and his perfection, however his will and intellect may be conceived.

[30] Further, all the Philosophers I have seen concede that in God there is no potential intellect,68 but only an actual one. But since his intellect and his will are not distinguished from his essence, as they all also concede, it follows that if God had had another actual intellect, and [35] another will, his essence would also necessarily be other. And therefore [II/76] (as I inferred at the beginning) if things had been produced by God otherwise than they now are, God’s intellect and his will, i.e. (as is conceded), his essence, would have to be different [NS: from what it now is]. And this is absurd.

Therefore, since things could have been produced by God in no [5] other way, and no other order, and since it follows from God’s supreme perfection that this is true, no truly sound reason can persuade us to believe that God did not will to create all the things that are in his intellect, with that same perfection with which he understands them.