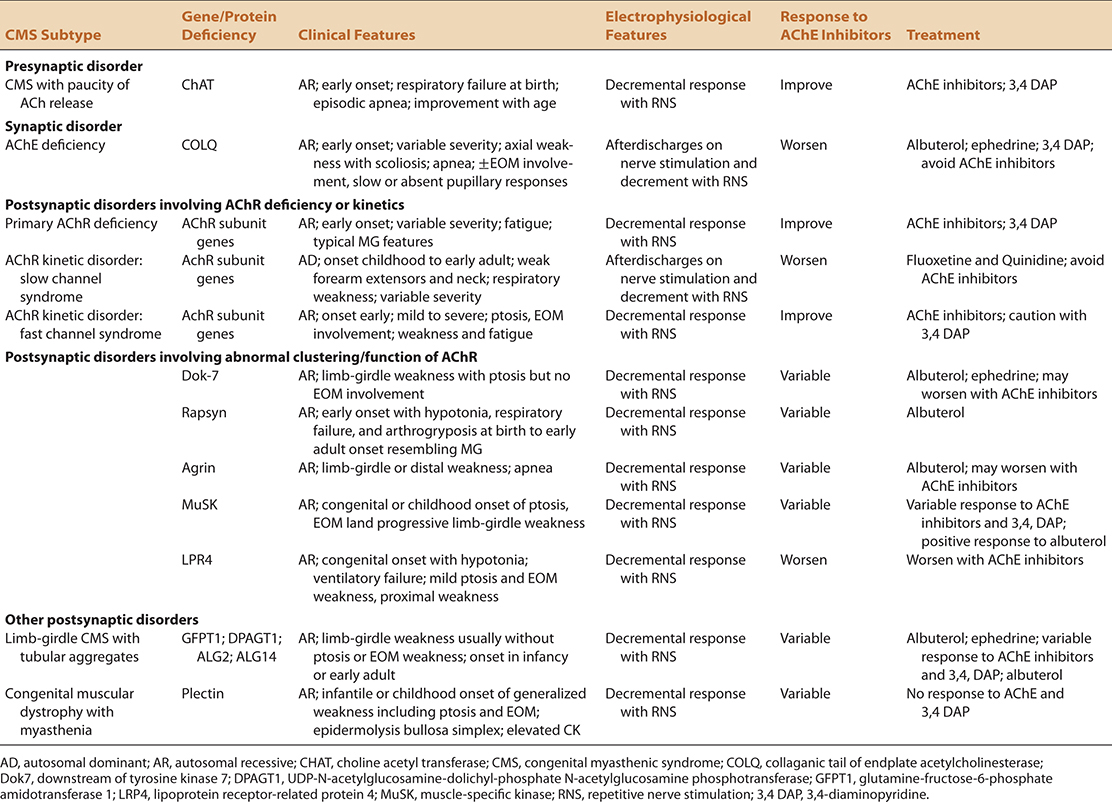

TABLE 26-1. DISORDERS OF NEUROMUSCULAR TRANSMISSION OTHER THAN AUTOIMMUNE MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

TABLE 26-1. DISORDERS OF NEUROMUSCULAR TRANSMISSION OTHER THAN AUTOIMMUNE MYASTHENIA GRAVISThis chapter describes the disorders of neuromuscular transmission (DNMT) other than myasthenia gravis (MG) (Table 26-1). The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is a physiologically complex structure. Its ability to function optimally requires the integration of a large number of proteins including ion channels that are correctly configured and distributed. As a result of numerous potential sites of vulnerability, DNMTs may occur as a consequence of multiple, albeit infrequent disorders. Autoimmune, genetic, or toxic mechanisms may disrupt the ultrastructure or physiology of the NMJ, thus interfering with effective NMT.

TABLE 26-1. DISORDERS OF NEUROMUSCULAR TRANSMISSION OTHER THAN AUTOIMMUNE MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

TABLE 26-1. DISORDERS OF NEUROMUSCULAR TRANSMISSION OTHER THAN AUTOIMMUNE MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Presynaptic

Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS)

Botulism and botulinum toxin

Tick paralysis (Australian)

Congenital myasthenia gravis

Choline acetyltransferase deficiency (ChAT)

Paucity of synaptic vesicles

Congenital LEMS

Toxins

Envenomation

Elapid snake species (kraits, mambas, coral snakes)

Arthropods (black and brown widow spiders, scorpions)

Marine species (cone snails, sea snakes)

Drugs

Aminoglycosides and other antibiotics

Calcium channel blocking agents (minor)

Aminopyridines

Corticosteroids

Hemicholinium-3

Synaptic/basal lamina

Congenital myasthenic syndromes

Acetylcholine esterase deficiency (COLQ)

Laminin β2 (LAMB2)

Drugs and toxins

Reversible cholinesterase inhibitors—edrophonium, pyridostigmine, and neostigmine

Irreversible—organophosphates and carbamates

Postsynaptic

Drug-induced myasthenia gravis

Penicillamine

Alpha-interferon

Congenital myasthenic syndromes

Agrin deficiency (AGRN)

AChR (subunit) deficiency with or without kinetic defect [slow (opening) or fast (opening) channel syndromes]

εAChR subunit (CHRNE)

αAChR subunit (CHRNA1)

βAChR subunit (CHRNB1)

δAChR subunit (CHRND)

γAChR subunit (Escobar syndrome)

AChR—structural or organizational defects

Dok-7 deficiency (DOK7)

MuSK deficiency (MuSK)

Rapsyn deficiency (RAPSN)

Sodium channel myasthenia (SCN4A)

Plectin deficiency (PLEC)

Glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase 1 MG (GFPT1)

Dolichyl-phosphate N-acetylglucosamine-phosphotransferase 1 MG (DPAGT1)

Drugs and toxins

d-Tubocurarine, vecuronium, and other nondepolarizing blocking agents

Succinylcholine, decamethonium, and other depolarizing blocking agents

Tetracyclines, lincomycin, and other antibiotics

LAMBERT–EATON MYASTHENIC SYNDROME

LAMBERT–EATON MYASTHENIC SYNDROMEThe Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) can be conceptualized as an acquired presynaptic DNMT typically presenting with symptoms of proximal lower extremity weakness and fatigue. The first single case description of LEMS was provided by Anderson in 1953. Its eponym however is credited to Edward Lambert and Lee Eaton who along with Edward Rooke described in 1956 the electrophysiological as well as clinical characteristics of the disorder in six cases.1,2 LEMS is a rare disorder with an estimated incidence of 1 and prevalence of 3.5 per million people.1–10 LEMS is largely a disease of adults although rare pediatric cases have been described [both acquired autoimmune condition and as a congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS)].11 LEMS is paraneoplastic disorder in many cases, but can be seen as a primary autoimmune disorder without an underlying cancer. The epidemiology between those cases of LEMS associated with a malignancy differs from those cases without an underlying neoplasm. Nonneoplastic LEMS appears to have two peaks, 35 and 60 years of age, occurring far frequently in women in the younger group. Paraneoplastic LEMS peaks in incidence at age 60 with two-thirds of this group being men.2

In adult LEMS, there is a strong support for a causative relationship for autoantibodies directed against voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) which are detectable in the majority of afflicted individuals, regardless of the presence of an underlying malignancy.12 Paraneoplastic LEMS comprises approximately two-thirds of cases. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung (SCLC) is the underlying malignancy in approximately 90% of these cases and 50–60% of all cases.13–15 Thymic tumors, non-SCLC lung cancers, lymphoproliferative disorders, and prostate cancer are the next most common associations.2,16–19 Pancreatic, breast and ovarian carcinomas, and Wilms’ tumor may represent chance associations.12,20,21 Conversely, it is estimated that between 0.5 and 4% of all SCLC patients will develop the clinical features of LEMS and approximately 8% will develop VGCC autoantibodies.22,23 The LEMS symptoms usually precede tumor recognition. Historically, this latency has been typically estimated to be less than 1 year, but may extend beyond 5 years in rare cases. These figures may however, represent a bias generated by surveillance techniques less sensitive than those currently available. In a more recent study of 100 LEMS patients followed for a minimum of 3 and a median of 8 years, 91% of those with malignancy were identified by 3 months of symptom onset and 96% by the end of the first year.15

The phenotypic and electrophysiological characteristics of paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic LEMS for all intents and purposes are indistinguishable in individual cases.24 Suspicion for an underlying malignancy should increase however, if the patient is over 50 years, has a history of tobacco use, progresses rapidly, or develops weight loss, erectile dysfunction, or bulbar symptoms within 3 months of symptom onset.2 A person with all six of these characteristics has a greater than 90% chance of harboring an underlying malignancy.2 Presumably, symptoms suggestive of other paraneoplastic disorders would increase the probability of an underlying malignancy as well. In general, paraneoplastic LEMS progresses more rapidly than its nonparaneoplastic counterpart.25 Other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, vitiligo, celiac disease, or even MG occur in approximately 25% of cases and their presence favors a nonneoplastic form of the disease.14,26,27Although the phenotype of LEMS appears homogeneous, independent of underlying cause or serology, the natural history of LEMS however, may be influenced by serotype. On average, seronegative LEMS patients appear to have a shorter life expectancy. An explanatory hypothesis for this observation is a potential therapeutic role for autoantibodies (see below).

Lack of stamina and fatigue are the most common presenting symptoms of LEMS.1,3,5,7–10,28,29 In our experience, the described morbidity often seems disproportionate to the degree of objective weakness. It has been our perspective as well that this discordance may contribute to the suspicion of a psychogenic disorder, particularly in young women. Symptomatic weakness in LEMS typically relates to functions requiring proximal, particularly lower extremity muscles and is noted in approximately 80% of patients during the course of the illness. A third of patients complain of muscle aching and stiffness during or following physical exertion. Approximately 20% of patients note that their weakness and fatigue are exacerbated by hot weather or baths. Ocular and bulbar symptoms are not as common or as severe as seen in MG but do occur.15,30,31 They typically develop later in the disease and are rarely the sole or initial manifestation.2,31,32 Symptomatic diplopia without overt ophthalmoparesis is typically transient and mild when it occurs. Ptosis is more common in our experience and is estimated to occur in a third to a half of cases. In those with cranial muscle involvement, neck flexor, extensor, and facial muscles are among the most commonly affected. Head drop has been reported as a presenting manifestation.33 Some patients develop dysarthria or dysphagia. Ventilatory muscle involvement is rare although breathing issues related to smoking, chronic lung disease, and lung cancer are not. Ventilatory failure as a rare presenting manifestation of LEMS has been described.34–36

As a presynaptic DNMT, in contrast to MG, LEMS frequently affects both nicotinic and muscarinic function with resultant cholinergic dysautonomia. This may manifest as blurred vision (impaired accommodation), xerostomia, xerophthalmia, constipation, hypohydrosis, and/or impotence.12 Xerostomia may contribute to dysphagia and dysarthria. Complaints of numbness and paresthesias in the distal extremities occur less frequently. They are not related to disordered NMT but more likely result from any of the mechanisms relevant to cancer patients. Patients with LEMS may have coexistent paraneoplastic syndromes such as sensory neuronopathy, cerebellar ataxia, and/or limbic encephalitis with frequently coexistent Hu autoantibodies.37

One potential explanation for the apparent discordance between the severity of patient symptoms and their actual strength logically extrapolates from disease pathophysiology. As brief exercise can transiently enhance neuromuscular transmission in presynaptic disorders, the patient’s strength should be ideally assessed at the initiation of contraction, not several seconds later. This transient improvement in strength usually dissipates with sustained muscle contraction. It is most readily identified in hip and shoulder girdle muscles. Repetitive squatting may be one means to demonstrate this phenomenon. Exercise may also be used to evaluate ptosis, which may be temporarily improved with sustained voluntary lid elevation in a manner opposite to MG.38

There are other potential, noteworthy observations to be made in an LEMS patient. Typical of DNMTs, muscle bulk in LEMS tends to be preserved. In advanced stages of the disease however, muscle atrophy can be observed. Sluggish pupillary reaction in response to a light stimulus or diminished sweating in response to a provocative challenge are means by which to identify cholinergic dysautonomia. Deep tendon reflexes are typically diminished or absent in LEMS. Like assessments of strength, this phenomenon may be obscured if manual muscle testing is done prior to deep tendon reflex assessment.

A small number of patients will present with what seems to be an MG/LEMS overlap syndrome.39–41 Most MG cases overlapping with LEMS are based on the presence of acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies in patients who otherwise appear to have LEMS on a clinical and electrophysiological basis. As many as 13% of patients with LEMS have AChR-binding autoantibodies.42 The AChR autoantibodies may be epiphenomenal rather than pathogenic in at least some LEMS patients.42,43 Nonetheless, rare patients may exhibit clinical features of both LEMS and MG.39,42,44,46

As a disorder characterized by a subacute limb-girdle weakness and fatigue, the primary differential diagnostic considerations for LEMS are limb-girdle myopathies and MG. MG may readily be confused with LEMS, particularly if signs and symptoms of oculobulbar weakness are readily evident with LEMS or if they are inapparent in MG. As a general rule, oculobulbar signs occur early and are prominent in MG and tend to be less frequent, less severe, and occur later in the disease course in LEMS.2,31 Exceptions do exist.15,30 Botulism has similar clinical features to LEMS including the pattern of weakness and the presence of cholinergic dysautonomia. Both its typically acute onset and the clinical context in which it occurs are the usual discriminating factors. LEMS can present in childhood and CMS may first manifest itself in adulthood. Consequently, CMS deserve consideration in any LEMS suspect as well. Motor neuron diseases that produce a limb-girdle pattern of weakness such as Kennedy disease are distinguished by their chronicity, and the presence of atrophy and fasciculations. The pattern and evolution of the weakness produced by multifocal motor neuropathy are, as the name implies, usually distinctive from LEMS. Motor predominant forms of CIDP may represent a very relevant diagnostic consideration in an LEMS suspect, particularly as both abolish deep tendon reflexes and affect the autonomic nervous system. The majority of these disorders can be readily distinguished from LEMS by electrodiagnostic (EDX) testing.

Diagnostic confirmation of LEMS is obtained by electrophysiological and/or autoantibody testing. As with all DNMTs, sensory conductions are normal unless paraneoplastic sensory neuropathy, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, or other confounding disorders coexist. H reflexes may be absent upon initial attempts at elicitation but may appear following muscle contraction, an observation more likely to be of academic interest rather than pragmatic benefit.46

In LEMS and other presynaptic DNMTs, the baseline compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes are significantly reduced in contrast to typical MG. Reduced CMAP amplitudes are in many cases widespread in the distribution. In a large study of 73 patients with LEMS (42% with lung cancer), the CMAP amplitude was reduced in the abductor digiti quinti (ADQ) in 95%, abductor pollicis in 85%, extensor digitorum brevis in 80%, and in the trapezius in only 55% of cases.47 This diffuse pattern of reduced CMAP amplitudes in the presence of normal sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) may provide the initial suspicion for LEMS. The CMAP response to exercise and/or repetitive stimulation along with serological testing provide confirmation.5,6,8,48–55

On occasion, the EDX pattern in LEMS may be confused with MG. LEMS patients will typically demonstrate both an incremental pattern to fast repetitive stimulation (10–50 Hz) or brief exercise as well as a decremental response to slow (2–5 Hz) repetitive stimulation (Fig. 26-1A and B).47,53–57 If a patient with LEMS is seen early enough in their illness however, their baseline CMAP amplitudes may fall within population norms. In this situation, the incremental response characteristic of a presynaptic deficit may not be either evident or sought for. The demonstration of a decrement in response to slow (2–5 Hz) repetitive stimulation, characteristic of both LEMS and MG, without demonstration of an increment may lead to misdiagnosis. If LEMS is suspected but cannot be confirmed either electrodiagnostically or serologically, the evolution into the typical presynaptic DNMT pattern may be disclosed with repeated nerve conduction studies.58,59

Figure 26-1. Incremental response to brief (10 seconds) exercise in a patient with LEMS (A) (trace 1 ulnar CMAP at baseline, trace 2 ulnar CMAP immediately after 10 seconds of isometrically resisted finger abduction, trace 3 ulnar CMAP 1 minute later). Incremental response to 20-Hz fast repetitive stimulation (B).

This decremental pattern in LEMS is similar although not necessarily identical to that described in MG. In MG, following the initial decrement between the first and fifth stimuli, there is an increase in CMAP amplitude between the fifth and tenth stimuli. The CMAP amplitudes in LEMS plateau continue to decline between the fifth and tenth responses in LEMS.60,61 In LEMS, decrement in response to 3-Hz stimulation has been demonstrated in the ADQ in 98%, APB in 98%, EDB in 84%, and trapezius in 89% of cases.47

In a cooperative patient, incremental testing can be rapidly and easily performed. A supramaximal baseline CMAP is obtained after suitable hand warming. The muscle tested is then subjected to 10–15 seconds of isometric resistance. Immediately thereafter, a second, supramaximal electrical stimulus is applied. In normal individuals, there may be a mild increase in CMAP amplitude (<40%) associated with a shorter duration and similar area under the curve (pseudofacilitation). The actual basis of this phenomenon is poorly understood. It has been postulated to represent improved motor unit synchronization due to a disproportionate increase in the conduction velocity of the slowest conducting muscle fibers.62,63 In the majority of patients with LEMS, brief exercise will produce a 100–400% increase in CMAP amplitude. It is important to recognize that patients with end-stage LEMS may fail to mount this dramatic of an incremental response.64 In individuals who cannot cooperate with isometric exercise for whatever reason, “fast” repetitive stimulation of 20 Hz or higher represents a more uncomfortable means by which to demonstrate the characteristic increment.

Abnormal insertional and spontaneous activity on needle examination such as fibrillation potentials are typically absent in LEMS.5,6,28,50,51,58,65 Abnormalities of motor unit action potential (MUAP) morphology are apparent in weak muscles if carefully assessed. Neuromuscular blockade at individual myoneural junctions effectively reduces the number of single fiber action potentials contributing to the MUAP, resulting in shorter duration and lower amplitude waveforms. Consequently, the twitch tension of motor units decline and compensatory early (increased) recruitment results. In addition, the random blockade of single myofiber action potentials desynchronizes the MUAP leading to an increased percentage of polyphasic MUAPs. Motor unit variability (instability) is readily evident in LEMS if sought for but will be less apparent with the facilitation promoted by increased MUAP firing frequencies.

Predictably, both volitional and stimulated single fiber electromyography (SFEMG) evaluations of patients with LEMS yield abnormal results.8,48,50,51,53,56,66–77 Jitter values in patients with LEMS are significantly elevated and statistically exceed that observed in MG. In essentially all NMJs examined, irrespective of muscle chosen, markedly abnormal jitter values are evident. This is disparate from MG where a spectrum of jitter values from normal to highly abnormal exists within and between individual muscles. Unlike MG, the jitter in patients with LEMS is not dependent on the degree of weakness in a particular muscle. Blocking is often more prevalent and severe in LEMS in comparison to MG. Some of the highest percentages of blocked potentials occur in LEMS.

Frequency-dependent alterations in jitter and blocking are also observed in LEMS if sought for as implied in the previous statements regarding frequency-dependent MUAP variability (instability). Specifically, at low rates of voluntary firing, jitter and blocking can be quite impressive. Further increase in the duration of muscle activation or rate of individual MUAP firing will result in reduced jitter and blocking. These observations can be quantitated by using stimulated SFEMG.72,73,76,78,79 Stimulating an intramuscular neural branch and recording a single muscle fiber potential allow jitter measurement with quantifiable stimulus rates. One study of patients with LEMS demonstrated that the jitter decreased from a mean of 150 μs at a stimulation rate of 2 Hz to about 90 μs at a firing rate of 15 Hz.70,72 Similarly, when changing the stimulus frequency from 2 to 15 Hz, the percent of blockings decreased from 70% to fewer than 10%. Distinguishing MG from LEMS by contrasting stimulated SFEMG responses is theoretically possible but impractical in most circumstances. Muscle temperature affects EDX responses in LEMS as well.79–82 Decreasing muscle temperature results in an improvement in the CMAP amplitude at rest, reduces the magnitude of decrement at low rates of stimulation, and prolongs the duration of postactivation facilitation. Like MG, the yield of EDX testing will be increased not only by ensuring that limbs are adequately warm but also by discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitors 24 hours before testing.83

As dysautonomia in LEMS is commonplace, abnormal autonomic nervous system testing is anticipated. In a series of 30 patients with LEMS, autonomic testing revealed abnormalities of sudomotor function in 83% of patients, abnormal cardiovagal reflexes in 75%, decreased salivation in 44%, and abnormal adrenergic function in 37% of tested individuals in keeping with the predominantly cholinergic dysautonomia of the disease.10,12

Antibodies directed against the P/Q-type VGCC of the motor nerve terminals are believed to be pathogenic and are highly sensitive and specific for LEMS. They are detected by immunoprecipitation of VGCC from human brain, labeled with ω-conotoxin derived from the fish-eating Conus species of snails, incubated with serum from LEMS patients.2,84 These antibodies are detectable in the serum in 98% or more of paraneoplastic and >80% of nonparaneoplastic LEMS patients.12,24,42 Conversely, as previously mentioned, it is estimated that 4% of patients with SCLC will develop VGCC autoantibodies.25 In addition, antibodies directed against the N-type VGCCs, which are located on autonomic and peripheral nerves as well as cerebellar, cortical, and spinal neurons, are present in 74% of patients with paraneoplastic LEMS and 40% of nonparaneoplastic LEMS patients.12,42

LEMS patients may harbor other autoantibodies. The SOX1 antigen was originally found as a result of antiglial nuclear antibodies cross reacting with Bergmann glia of the Purkinje cell layer of rat cerebellum. The SOX1 antigen also plays a role in the development of airway epithelia and is found in SCLC. SOX autoantibodies are of potential clinical value as they are highly specific for LEMS and SCLC. They are found in two-thirds of LEMS patients with SCLC, 12% of SCLC without LEMS, and <5% of LEMS without cancer.85,86 Despite the cerebellar location of the antigen, there is no consistent association with paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration or other paraneoplastic disorders. These antibodies are commercially available as antiglial nuclear antibodies as part of the Mayo Clinic paraneoplastic antibody panel. As previously mentioned, some patients with paraneoplastic LEMS will also harbor Hu autoantibodies associated with a sensory ganglionopathy, cerebellar degeneration, and/or limbic encephalopathy.12,37,42 Autoantibodies against the presynaptic protein synaptotagmin have also been described in LEMS patients but have no current clinical application.2

Serological testing for VGCC and AChR autoantibodies usually accurately discriminate between LEMS and MG when there is phenotypic overlap. Nonetheless, as previously mentioned, AChR-binding antibodies are found in as many as 13% of patients with LEMS.42 Conversely, as previously mentioned, autoantibodies against the P/Q VGCCs are found in <5% of patients who have the phenotypic and electrophysiological characteristics of MG.42,43 The concurrence of both antibodies is thought to be epiphenomenal in most cases.42

Edrophonium testing in LEMS produces variable results and is not normally employed.

Surveillance for a potential underlying neoplasm should be undertaken to some extent in any patient with LEMS. There is published guidance as to how extensive the initial evaluation should be, and how frequently it should be repeated if the initial evaluation is negative.15 Although paraneoplastic LEMS is largely a disorder of older people who have smoked, we are of the opinion that every LEMS patient should have a careful physical examination, and some form of imaging. Chest x-ray is considered an insufficiently sensitive imaging procedure in this context.15 In a younger individual without a smoking history, we lobby for a total body positron emission tomographic scan (FDG-PET) while remaining aware that problems with both availability and reimbursement may be encountered. FDG-PET is likely the most sensitive means by which to detect an underlying malignancy.15 In an older patient with a smoking history, CT of the thorax will detect the majority of tumors that are initially detectable.15 If CT of the thorax is normal, FDG-PET is also suggested.15 Regarding subsequent surveillance in individuals in whom no tumor is initially detected, evaluation has been suggested at 6-month intervals for 2 years.15 Our personal preference is to apply this strategy only to those individuals with a smoking history. As contemporary data indicates that a very high percentage of individuals with initially occult neoplasms will be detected within the first year of LEMS onset, we would limit rescreening to 1 year. Once again, we prefer FDG-PET rather than CT in consideration with radiation exposure as well as the probable greater sensitivity of the former for malignancy detection outside of the central nervous system (CNS).

One reason to perform EDX in patients with limb-girdle patterns of weakness is to distinguish LEMS from myopathy and avoid muscle biopsy in these patients. If performed, muscle biopsy reveals only nonspecific type II fiber atrophy.8 On quantitative electron microscopic analysis, nerve terminals appear normal in both their size and the number of synaptic vesicles they contain.87 Similarly, the postsynaptic membrane is intact but with an increase in the postsynaptic fold area and number of secondary synaptic clefts, presumably as a compensatory mechanism in response to reduced quantal release. The total number and activation properties of individual AChRs appear normal. Freeze-fracture analysis of the presynaptic membrane demonstrates a marked decrease in the number of intramembranous proteinaceous particles, which are assumed to be P/Q VGCC. These presumptive channels are disorganized and aggregated in clumps.88–90

In summary, the preponderance of evidence suggests that LEMS is a disorder of impaired presynaptic ACh release resulting from autoantibody mediated–VGCC dysfunction. The mechanism appears to be downregulation of channels and endocytosis rather than mechanical blockade.27 As a consequence of this autoimmune assault, reduced presynaptic calcium ion concentrations occur in response to a motor nerve action potential.12,42 Quantal ACh content, that is, the number of active vesicles released in response to a nerve action potential is reduced and neuromuscular transmission compromised.12,14,27,90,92

Presynaptic function includes concentrating and storing ACh within vesicles, facilitating their movement to active release zones where they dock and fuse, thus setting the stage for ACh release into the synaptic cleft in response to a motor nerve action potential. The migration, docking, and fusion with the presynaptic plasma membrane and subsequent exocytosis into the synaptic cleft are all dependent on the complex interaction of an extensive number of proteins. Some of the more notable constituents of this complex neuromuscular transmission process include synaptobrevin and synaptotagmin (associated with the synaptic vesicles), NSF (N-ethylamide sensitive ATPase) and α-SNAP (both found in the cytosol), syntaxin and SNAP-25 (synaptic vesicle–associated 25-kDa protein), and membrane-bound VGCCs.93 Synaptobrevin, syntaxin, and SNAP-25 are collectively known as SNARE (SNAP receptor) proteins. The known specificity of tetanus and botulism toxins for SNARE proteins and the impaired ACh release that results from their exposure to the NMJ illustrate the essential function of SNARE proteins in presynaptic vesicular exocytosis.

In normal individuals, a motor nerve action potential transiently opens presynaptic VGCCs resulting in an increased motor nerve terminal intracellular calcium concentration. The effect does not achieve the magnitude that it potentially could as the duration of the nerve action potential of <1.0 ms undershoots the activation time constant of the VGCC of 1.3 ms.91 The intracellular calcium concentration peaks by 200 μs and persists for approximately 800 μs following the nerve action potential, numbers critical to the understanding of repetitive stimulation responses in DNMT.

An intracellular calcium concentration of 200–300 μM is achieved under normal circumstances. It is estimated that 60 VGCCs need to open to allow the ingress of the approximately 13,000 calcium ions to promote required for exocytosis of a solitary vesicle. In mammalian systems, the response to a motor nerve action potential is a quantal content of 50–300 whereas in LEMS, the mean is roughly 8 (3.3–15).91 Similar effects on quantal content are achieved by reducing the calcium concentration or increasing the magnesium concentration in the extracellular fluid bathing the nerve terminal.93

The facilitatory effect of intracellular calcium on ACh release initiates with its binding to synaptotagmin, subsequently with syntaxin and SNAP-25, and eventually with synaptobrevin to complete the vesicular, exocytotic cascade. Calcium is believed to be essential in cleaving the bonds holding ACh vesicles to the intraneural cytoskeletal framework which is largely composed of actin and microtubules, thus hindering the vesicle’s ability to fuse or dock with recognition proteins at the active zones.93,94

There are six types of VGCCs in mammalian systems (L, N, P, Q, R, T) distinguished by their pharmacological and biophysical properties. The predominant channel in mammalian NMJs is the P/Q channel. The P/Q channel is composed of a pore-forming α1a subunit as well as α2δ, γ, and β4a subunits. The VGCCs are normally closed by neural repolarization promoted by the opening of presynaptic voltage–gated potassium channels. Failure of these channels to close promptly results in prolonged depolarization, and certain disorders of neuromuscular hyperactivity described in Chapter 10.

In normal individuals, these P/Q-type VGCCs are present on both the granule and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum and in presynaptic motor nerve terminals. They exist as well on small-cell carcinoma cells, providing a logical substrate for an autoimmune, paraneoplastic mechanism. In support of this, autoantibodies reacting with the P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 90% of patients with LEMS.

Autoantibody binding appears to specify the α1a subunit. As a consequence, there appears to be a downregulation in the number of calcium channels, resulting in a decrease in total current flow without a reduction of current flow in individual channels.96 Complement does not appear to be involved in this process. The nerve terminal maintains a grossly normal appearance without evidence of lytic destruction.88 A causative role for these autoantibodies is supported by the induction of all of the electrophysiological, morphological, and clinical manifestation of LEMS by passive transfer of IgG from patients with paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic LEMS to animals, or from mother to fetus.24,96,97 In addition, similar results utilizing the serum of seronegative patients supports an autoimmune mechanism in this group as well. The trigger for this autoimmune response is unknown. In patients with cancer, it is speculated that molecular mimicry results in the presynaptic motor nerve terminal becoming the innocent bystander in an immune response initially directed at the neoplasm.90,91,98 As LEMS occurs in only a small proportion of patients harboring SCLC, a genetic predisposition is hypothesized.99 Sixty-five percent of LEMS patients have the HLA haplotype HLA-B8-DR3, lending some support for this hypothesis although its prevalence appears greatest in the younger, nonneoplastic cohort.2

Identification and treatment of an underlying neoplasm, if present, is the foundation of LEMS treatment. If the tumor can be successfully treated, the morbidity of LEMS can be substantially reduced in a number of patients with concomitant improvement in their electrophysiological studies.48,98–102 If the patient remains symptomatic, with or without successful tumor treatment, adjuvant treatment with drugs that either enhance neuromuscular transmission or address autoimmunity can be utilized.2,9,29,103–105 Like myasthenia, the treatment regimen should be individually tailored in consideration with disease severity and the degree to which it affects a patient’s lifestyle, as well as numerous other contextual features including cost, availability, and relevant comorbidities. Like MG, avoidance of drugs with known neuromuscular blocking properties is recommended.

Pharmacological treatment for LEMS is largely based on clinical experience.103 As of this writing, only 3,4 diaminopyridine (3,4 DAP) and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) have been systematically studied.107

Anticholinesterase medications can be used in a manner identical to patients with MG.6,48,49,57,106 Analogous to MG, pyridostigmine provides symptomatic treatment without addressing the root cause of the disease. Electrophysiologically, its application may result in a 50–100% increase in the baseline CMAP amplitude. In our experience, the drug is effective although the response is often modest, and probably insufficient by itself in controlling the morbidity of the disease.

Guanidine, a drug that is believed to prolong the motor nerve action potential and augment quantal content, was used historically in LEMS treatment.48,52,59,107,108 A small open-label trial demonstrated that both strength and CMAP amplitude are improved in all patients tested. Unfortunately, gastrointestinal side effects and the serious risk of renal failure and bone marrow suppression have made it largely a drug of historical interest.

The aminopyridines are a class of drugs that block voltage-dependent potassium channel conductance. 3,4 DAP is the drug of choice, when available, for the symptomatic treatment of LEMS.2,48,103,106,109–112 It may be used in addition to pyridostigmine. Four prospective, randomized placebo-controlled trial of 3,4 DAP in LEMS patients (paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic) have identified improvements in multiple outcome measures including strength, quantitative myasthenic scales, and CMAP amplitudes.106,110,113 Our practice is to start cautiously with a dose of 10 mg t.i.d. The medication is generally well tolerated, with a few patients experiencing perioral and acral paresthesias. It is recommended that doses should not exceed 100 mg/day, as higher doses may result in seizures although its blood–brain barrier penetration is less than other aminopyridines.2,110 Cardiac conduction defects, particularly prolonged QT intervals are an additional concern and warrant EKG screening both before and during treatment. Like others, we have had no adverse cardiac experiences.2 In our experience, although beneficial, 3,4 DAP rarely restores either strength or stamina fully. It is not FDA approved and its availability is limited in the United States. It is available on a compassionate use basis through Jacobus Pharmaceuticals. Clinical trials for LEMS patients with both 3,4 DAP and an alternative formulation amifampridine are available (www.clinicaltrials.gov). The drug may also be acquired through compounding pharmacists.

An alternative pharmacological approach is attempted immunomodulation with drug treatment, plasma exchange, or intravenous immunoglobulin.2,29,48,103,109,114–119 A single crossover trial of IVIg demonstrated a benefit in strength and a decline in VGCC autoantibody titres but failed to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in CMAP amplitudes.116 Plasma exchange has been reported to have a clinical and electrical benefit in LEMS but has never been subjected to a prospective clinical trial.117–119 Improvements in CMAP amplitudes at rest, following exercise, or in response to high rates of repetitive stimulation following plasmapheresis may be seen.117–119 The peak response is observed by about 2 weeks after the treatment, with a diminution in effectiveness by the end of 3–4 weeks. There are no controlled trials in LEMS of any of the commonly used immunomodulating agents. The most common regimen used in LEMS is probably a combination of prednisone and azathioprine which has been shown to induce clinical remission in some patients.104,116 It may improve CMAP amplitudes as well as patient strength and stamina. Case reports have suggested a benefit from rituximab.120,121

One theoretical concern with LEMS or any other paraneoplastic neuromuscular disorder is the potential risk that suppressing the patient’s immune system will have adverse effects on tumor control. One hypothesis as to why LEMS often precedes tumor detection is that the same immune response that produces LEMS simultaneously limits tumor growth. Limited data suggests that immunomodulation can be utilized in LEMS without an adverse effect on tumor control.98

CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMES

CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMESThe CMS may be conceptualized as inherited DNMT that typically, but not universally, become evident at birth, in infancy, or in childhood. Juvenile and adult-onset cases do occur and are characteristic of specific genotypes (Tables 26-2 and 26-3).122–128 It is not uncommon for early-onset cases to go undiagnosed until later life, often misdiagnosed as seronegative myasthenia, myopathy, or spinal muscular atrophy. CMS are rare or at least uncommonly recognized conditions that are caused by specific protein deficiencies whose normal functions are requisite to successful neuromuscular transmission at presynaptic, synaptic, and/or postsynaptic locations. The majority of CMS are related to proteins unique to the NMJ resulting in a purely neuromuscular syndrome. A few of the CMS are related to proteins affecting other organ systems including cardiac and smooth muscle, skin, and kidney.128,129 Rarely, there may be CNS involvement with microcephaly, seizures ocular, and auditory abnormalities.128 Connective tissue involvement with skeletal deformities or contractures occur in some cases most notably in rapsyn deficiency, AChR γ deficiency (Escobar syndrome) and some of the more recently described, later-onset, limb-girdle syndromes associated with abnormal glycosylation.125,130–138

TABLE 26-2. CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMES

TABLE 26-2. CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMES

TABLE 26-3. DIAGNOSTIC CLUES USED TO IDENTIFY AND CLASSIFY CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMES

TABLE 26-3. DIAGNOSTIC CLUES USED TO IDENTIFY AND CLASSIFY CONGENITAL MYASTHENIC SYNDROMES

General clues (relative, not absolute)

• Early onset (inutero, neonatal, or infantile)

• Consanguinity, affected relatives suggesting an AR pedigree

• Seronegativity for autoimmune MG

• Refractoriness to cholinesterase inhibitors

• Failure to respond to immunomodulating agents

• Nonspecific light microscopic changes in muscle (if performed)

Epidemiology

• Ethnicity

German, Western/Central Europe

Dok-7, Rapsyn deficiencies

Brazil, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia, Algeria

AChR ε deficiency—CHRNE

Near-Eastern Jewish

Rapsyn deficiency

• Age of onset

Severe, lethal, akinetic syndrome

AChR γ deficiency

AChR α, β, δ subunit deficiencies

Rapsyn deficiency

Dok-7 deficiency

Typical onset—birth or infancy

ChAT deficiency

AChE deficiency

AChR subunit deficiencies

AChR deficiency with kinetic defect—fast channel syndrome

Rapsyn deficiency

LRP4

Variable including potential late-onset

Rapsyn deficiency (some cases)

Dok-7 deficiency

GFPT1 myasthenia (some cases)

DPAGT1 myasthenia

AChR (subunit) deficiency with kinetic defect—slow channel syndrome

MuSK deficiency

ALG2 and ALG14

• Symptoms worsened by cold

AChE deficiency

• Periodic exacerbations

Intercurrent infection

Rapsyn deficiency

ChAT deficiency

AChR (subunit) deficiency and fast channel syndrome

Pregnancy and menstruation

Dok-7

MuSK deficiency

Indeterminate reasons

DPAGT1 MG

• Dominant inheritance

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel

Electrophysiology

• Afterdischarges

AChE deficiency (not universal)

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel

Agrin deficiency

• CMAP incremental response

Congenital LEMS

• Decremental response to repetitive stimulation at 2–5 Hz

AChR (subunit) deficiency

Dok-7

ChAT deficiency (some cases)

AChE deficiency

Congenital LEMS

DPAGT1 CMS

GFPT1 CMS

ALG2/ALG14 CMS

LRP4 CMS

• CMAP decremental response to variable rates

ChAT deficiency (10 Hz RS for 5 min)

Muscle histology

• End plate myopathy

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel

AChE deficiency

• Tubular aggregates

GFPT1 CMS

DPAGT1 CMS

ALG2/ALG14 CMS

Response to treatment

• Refractory to or exacerbated by cholinesterase inhibitors

AChE deficiency (COLQ) (relative contraindication)

Laminin β2 myasthenia (relative contraindication)

AChR (subunit)—kinetic disorder—slow channel syndrome

Dok-7 deficiency

Agrin deficiency

Rapsyn deficiency

Plectin

LRP4 CMS

• Responsive to cholinesterase inhibitors

Laminin β2 myasthenia

GFPT1 myasthenia

DPAGT1 myasthenia

ChAT deficiency (variable)

AChR (subunit) deficiency or fast channel syndrome (partial)

CMS with a paucity of synaptic vesicles

MuSK deficiency (partial)

Congenital LEMS

• Refractory to 3,4 DAP

AChE deficiency

Congenital LEMS

Agrin defect

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—fast channel syndrome (relatively contraindicated)

Dok-7 deficiency

• Responsive to 3,4 DAP

ChAT deficiency (variable)

AChR (subunit) deficiency

Rapsyn deficiency

Agrin deficiency

MuSK deficiency (limited)

Congenital LEMS

GFPT1 myasthenia

• Responsive to sympathomimetic amines (albuterol, ephedrine, salbutamol)

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel

AChE deficiency (some cases)

Agrin deficiency

MuSK deficiency

Dok-7 deficiency (some cases)

Laminin β2 myasthenia

DPAGT1 MG

• Responsive to open channel blockers (quinidine, quinine, fluoxetine)

Slow channel syndrome

• Responsive to guanidine

Congenital LEMS

Phenotype

• Pattern of weakness

Typical oculobulbar pattern

CMS with a paucity of synaptic vesicles

ACh receptor deficiency

MuSK deficiency

Ophthalmoparesis limited or absent

AChR deficiency with kinetic defect—slow channel syndrome

Dok-7 myasthenia

GFPT1 deficiency

Rapsyn deficiency

ChAT deficiency

Congenital LEMS

Agrin deficiency

ALG2/ALG14 CMS

Significant involvement of limb and axial muscles

ACh receptor deficiency

Dok-7 deficiency

GFPT1 MG

DPAGT1 MG

Rapsyn (some cases)

Agrin deficiency (some cases)

MuSK deficiency

ALG2/ALG14

Preferential involvement of distal muscles or distinctive muscle groups

Rapsyn (late-onset) (foot drop)

AChR deficiency—kinetic disorder—slow channel (cervical muscles, wrist/finger drop)

Agrin deficiency

GFPT1 myasthenia (scapular winging, foot drop, wrist/finger drop)

DPAGT1 MG (foot drop, wrist/finger drop)

Stridor/vocal cord paralysis

Dok-7 deficiency

Infantile hypotonia

ChAT deficiency

AChR deficiency

LRP4

Episodic apnea

ChAT deficiency

Na—channel myasthenia

Rapsyn deficiency

AChE deficiency

Dok-7 deficiency

MuSK deficiency

GFPT1

• Contractures or dysmorphic features

Rapsyn deficiency (facial deformities)

ACh receptor deficiency (particularly the gamma and fetal γ subunit)

GFPT1 myasthenia

ALG2/ALG14 CMS

• Delayed pupillary light reflex

Acetylcholinesterase deficiency

Laminin β2 myasthenia

• Systemic features

Nephrotic syndrome, ocular abnormalities Laminin β2 myasthenia

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex Plectin deficiency

The prevalence of genetically identifiable CMS is estimated at 3.8 × 106.131 Currently there are at least 18 recognized CMS and 17 recognized genotypes that are characteristically categorized by the primary anatomic region of the NMJ that is adversely affected and the identity of the mutated protein (Table 26-1).139 Of these genotypes, the most commonly occurring are postsynaptic with deficiencies of the ε subunit of the AChR, downstream of tyrosine kinase (Dok-7), and rapsyn deficiency constituting up to 75% of identifiable cases.126

CMS are phenotypically heterogeneous, even within the limited manifestations of the neonate and child. This heterogeneity exists both within and between different CMS genotypes.122,128,130,140 It is attractive to suggest that the more consistent phenotype of autoimmune MG and LEMS is a consequence of what is essentially a singular target in both conditions, the AChR and VGCC, respectively. Conversely, the CMS result from the disordered structure of nerve terminals, individual AChRs, abnormal AChR distribution, or abnormal NMT physiology at either the presynaptic, synaptic, or postsynaptic level.

There are phenotypic manifestations of CMS that serve both to suggest not only a CMS, but also in some cases implicating one or more specific CMS genotypes. These features are outlined in Tables 26-2 and 26-3. As is the case in all DNMT, the CMS phenotype is typically dominated by symptoms attributable to skeletal muscle weakness. Like autoimmune MG, oculobulbar muscles are commonly involved but sparing or limited involvement of oculobulbar musculature may occur. This pattern has been most commonly associated with choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), acetylcholinesterase (AChE, COLQ) rapsyn, agrin, Dok-7, glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase 1 (GFPT1), dolichyl-phosphate N-acetylglucosamine-phosphotransferase 1 (DPAGT1), ALG2, and ALG deficiencies.125,128–130,132,133,135–138,140,141

CMS may become evident in utero with maternal recognition of reduced fetal movement. This phenotype is most commonly associated with AChR γ subunit gene mutations and to a lesser extent with mutations of the α, β, and δ subunits, Dok-7, and rapsyn genes.125 More commonly, CMS present at birth or at infancy as a “floppy infant” with neonatal hypotonia in combination with a poor suck and weak cry, or with apneic episodes. Stridor, choking spells, and/or ventilatory difficulties are less-specific manifestations that are not uncommon particularly in this period. Contractures are another potential neonatal manifestation and have been reported in rapsyn deficiency (associated with facial deformities), ACh receptor deficiency (particularly the γ and fetal γ subunit), GFPT1, ALG2, and ALG14 deficiencies.130–133

When present, ptosis, is typically but not universally symmetric and diurnally variable. Ptosis and opthalmoparesis when present, are helpful clues in distinguishing CMS from other causes of weakness in all age groups (Fig. 26-2).123 In some patients, particularly in later onset cases, limb-girdle weakness may predominate with relative sparing of oculobulbar musculature. Historically, this was referred to as limb-girdle MG.142–145 This nomenclature has been supplanted by classification based on genotype as mutations correlating with this phenotype continue to be uncovered. Currently Dok-7, GFPT1, DPAGT1, ALG2, and ALG14 deficiencies are the most frequent causes of this syndrome.131–138,146

Figure 26-2. Ptosis, compensatory frontalis contraction, and partial ophthalmoparesis in a 15-year-old female with epsilon subunit deficiency. (Used with permission from Prof. Feza Deymeer, University of Istanbul, Istanbul, Turkey.)

Prominent scapular winging may be seen in some subtypes. CMS may affect not only proximal upper and lower extremity muscles but also can be associated with foot and finger drop. The latter may affect some digits more than others and suggest an increased likelihood of specific CMS genotypes in the appropriate context (Tables 26-2 and 26-3; Figs. 26-3 and 26-4). Despite NMJ localization, muscle atrophy is not rare in older individuals. In older individuals, limited stamina and prominent fatigue may be the predominant morbidity.

Figure 26-3. Weakness of wrist and finger extension in slow channel syndrome. (Used with permission from Prof. Feza Deymeer, University of Istanbul, Istanbul, Turkey.)

Figure 26-4. Weakness of finger extension in adult female with neonatal dysphagia and apneic episodes attributed to nonspecific myopathy. Became ventilator dependent following scoliosis surgery at age 11, and walked unassisted until age 15. Developed unilateral ptosis in adulthood. Diagnosed with CMS secondary to agrin deficiency at age 43.

Both diurnal variation and periodic exacerbation of CMS may occur, the latter commonly resulting from fever or intercurrent illness, pregnancy, menstruation, or even stress.125,126,128 Involvement of other end organs with certain CMS genotypes may produce recognizable syndromes providing an additional source of diagnostic information. Cardiac and smooth muscles are however, uncommonly involved in the majority of syndromes (Tables 26-2 and 26-3).147 We are unaware of significant dysautonomia occurring in these disorders.

The natural history of CMS is quite variable. Delayed motor milestones are the norm in those affected in infancy. Some individuals have a seemingly static course whereas insidious disease progression is anticipated in two of the syndromes. Only one of the currently recognized syndromes (slow channel syndrome) is typically inherited in a dominant fashion, the remaining disorders being autosomal recessive.148,149 Recognition of recessive inheritance pattern or parenteral consanguinity are supportive diagnostic clues for CMS although in small or fragmented families, cases may appear to be sporadic.

Because of its infrequency, CMS may not be considered in the differential diagnosis of a weak patient. Predictably this pitfall is more likely to be encountered in older individuals, particularly in those with a predominantly limb-girdle patterns of weakness. Even in an older individual with a typical MG phenotype, CMS should be given at least brief consideration in any patient with suspected seronegative myasthenia, myopathy of indeterminate cause, or spinal muscular atrophy.150

The following summarizes the notable clinical features of specific CMS. Associated genes are listed in parentheses after each disorder heading (Tables 26-2 and 26-3).

This disorder characteristically manifests as a distinctive phenotype of episodic bulbar weakness with a weak cry and poor sucking capability, and ventilatory distress with potential apnea. Ptosis is common, ophthalmoparesis is rare. The natural history is variable. Apneic episodes may begin in the neonatal period, infancy, or childhood and may be lethal. They may resolve or recur episodically even into adult life. Exacerbations may be triggered by intercurrent infection or other stress.

The single reported case of this phenotype described ptosis, ophthalmoparesis, facial weakness, and generalized fatigable weakness of the extremities that began in infancy. The molecular basis of this disorder is unknown.

Rare cases of this disorder have been described, predominantly recognized by the characteristic presynaptic EDX pattern described in the diagnostic section. The two described cases involved a severely affected neonate with hypotonia, bulbar weakness, and ventilator dependency and a young child with less-severe manifestations including delayed motor milestones without eye movement or other distinctive abnormalities.

This the most common cause of synaptic CMS, inherited in a recessive fashion. The natural history is again variable ranging from a typical neonatal disorder with severe morbidity to later-onset, more indolent cases. Early-onset cases tend to be dominated by hypotonia and delayed motor milestones, ventilatory and bulbar difficulties, associated with ptosis and ophthalmoparesis in some but not all cases. Slow pupillary responses to light are reported as a distinctive although not necessarily unique feature of this genotype. In later life, limb weakness, muscle atrophy, and skeletal deformities particularly involving the spine may become apparent. Survival into adulthood is the norm.

This is a rare, severe form of CMS. As the β2 chain of laminin is found in other tissues, mutations of the LAMB2 gene may result in Pierson syndrome as well as CMS with associated congenital nephrotic syndrome and ocular defects. The described phenotype includes delayed motor milestones with facial and limb-girdle weakness, with or without ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, pupillary and macular abnormalities, and the potential for ventilatory muscle weakness.

Despite the presynaptic site of its synthesis, the major role of agrin is to initiate AChR clustering by binding to lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) resulting in phosphorylation of muscle-specific kinase (MuSK). Activated MuSK interacts in turn with Dok-7 and rapsyn to promote AChR aggregation. Agrin CMS is a rarely reported, with a mild phenotype characterized by ptosis, delayed motor milestones and mild proximal weakness. We have seen prominent wrist and finger drop when the diagnosis was delayed until adulthood (Fig. 26-5). Ophthalmoparesis is an inconsistent feature. Facial and ventilatory muscle weakness occur in some cases.

Figure 26-5. Decremental response to repetitive stimulation from extensor indicis proprius leading to diagnosis of CMS.

Subunit mutations are the most common forms of the postsynaptic CMS. The ACh channel typically consists of two α subunits, one β, one δ, and one ε, the latter which normally supplants the fetal γ subunit late in gestation. Adult subunits are encoded by the individual genes listed above. The ε subunit gene (CHRNE) is the most common subunit deficiency and the most common CMS in most series.126 This mutation tends to be more benign than other CMS as the ε subunit deficiency may be buffered to some extent by persistent fetal γ subunit function. This compensatory mechanism is not an option for other subunit mutations. Subunit mutations may adversely affect neuromuscular transmission by at least two mechanisms which may occur individually or concurrently. They may either reduce subunit expression and consequently receptor function and/or alter ACh channel kinetic properties. Kinetic alterations may produce either a slow channel (i.e., slow to close resulting in increased ionic passage) or fast channel (i.e., fast to close resulting in truncation of normal ionic passage from extracellular to intracellular compartments) syndrome. As previously implied, impaired NMT may result from either subunit deficiency and/or abnormal kinetic function and are not mutually exclusive.

The phenotype of AChR subunit mutations is again variable although more likely static than progressive. As described, mutations in the AChR ε subunit gene with reduced subunit expression typically correlates with a mild phenotype. Affected patients tend to have a nonprogressive phenotype typically manifesting as feeding problems and ptosis at birth or in infancy. Ophthalmoparesis is common although may not be present at birth (Fig. 26-2). Limb weakness occurs but ventilatory muscle involvement is rare. In contrast, non-ε AChR subunit gene mutations typically correlate with a more severe phenotype with ventilatory crises precipitated by choking and consequential shortening of life expectancy.

With a kinetic defect producing a slow channel syndrome, the clinical course is typically indolent, often sparing cranial musculature, and frequently affecting cervical muscles as well as wrist/finger extensors (Figs. 26-3 and 26-4). Spinal deformities may develop later in life. The fast channel syndrome tends to arise from the mutations in the α, δ, and ε subunit genes.166 Neonatal onset is the norm with a severe phenotype incorporating ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, bulbar and ventilatory weakness.

The Escobar syndrome results from mutations in the fetal γ subunit. As the contributions of the fetal subunit are largely dissipated by 33 weeks of gestation, neonates born with γ subunit mutations are typically born with arthrogryposis and ventilatory difficulties and do not develop a typical CMS phenotype.

This disorder most frequently presents with delayed onset in childhood but may present as late as the third decade. Although infantile onset may occur, normal motor milestones are commonly achieved before deterioration begins. Disease severity is variable, ranging from the mildly to severely symptomatic individuals. A progressive course is the most common. The typical phenotype is a limb-girdle pattern of weakness with the development of ambulatory difficulties during childhood. Ptosis may occur in later life. Ophthalmoparesis is infrequent and typically mild. Facial weakness is common. Significant bulbar symptoms including vocal cord paralysis, stridor, and poor feeding may occur in infancy. Severe disability including ventilatory failure may occur by the third decade in some cases. Worsening during pregnancy has been described.

The few reported cases of this disorder describe onset variability ranging from the neonatal period to later life. There is variability in disease severity as well. Ptosis, partial ophthalmoparesis, and mild facial weakness are commonplace. Weakness affecting proximal limbs, particularly shoulder abductors and ventilatory muscles occur in some but not all individuals.

This is one of the more common CMS, constituting approximately 15–20% of cases. The phenotype including age of onset is variable. Most cases present at birth or at infancy although cases presenting as late as the 20s occur. Neonatal arthrogryposis is common and prognathism and high-arched palate may occur. Crises may be precipitated by intercurrent infection. Ptosis, facial, jaw, and neck weakness are common whereas ophthalmoparesis is rare. Limb weakness is more common in later-onset cases. Although often proximal and symmetric, foot drop in late-onset cases is well recognized. If children survive the neonatal period, improvement with aging is not uncommon.

Predictably, a CMS patient with an LPR4 gene mutation has been recently described. The phenotype included hypotonia at birth with ventilatory and feeding difficulties. Motor milestones were delayed. As the child aged, prominent fatigue with proximal greater than distal extremity weakness became evident along with mild ptosis and ophthalmoparesis. A decremental response to repetitive stimulation was identified that responded favorably to edrophonium. Treatment with pyridostigmine however, aggravated weakness.

This disorder has been described in a single individual with recurrent apneic episodes and learning difficulties, perhaps related to hypoxic-ischemic injury.

Plectin is a protein that links different cytoskeletal elements to target organelles in different body tissues. It provides crucial support for the junctional folds of the NMJ. As a result, the phenotype includes the potential for multiorgan involvement including skin [epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS)], skeletal muscle (muscular dystrophy), smooth muscle (esophageal atresia), and cardiac muscle (cardiomyopathy). The phenotype typically begins in infancy as EBS and evolves into a disorder producing ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, dysphagia, facial and limb weakness associated with a decremental response to slow repetitive stimulation. Modest CK elevations may occur.

Like many of the CMS, this genotype has phenotypic heterogeneity. Onset of reported cases range from in utero recognition to 19 years of age. The course is typically slowly progressive. Neonatal cases may be arthrogrypotic, with poor bulbar function and apneic episodes. The most common phenotype is a later-onset syndrome dominated by a proximal > distal pattern of weakness. The distal muscles most commonly involved include forearm extensors, intrinsic hand muscles, and the anterior compartment of the leg. Serum CK values are elevated in 50% of cases.

Like GFPT1, DPAGT1 is an enzyme thought to be necessary for the glycosylation of the nicotinic AChR and integral to the assembly and insertion of the channel into the postsynaptic membrane. It shares other features with GFPT1 CMS including a propensity to begin beyond the neonatal period and to produce a limb-girdle pattern of weakness. It does not seem to significantly affect life expectancy and individuals in their sixth decade have been reported. Other features common to GFPT1 and DPAGT1 CMS are tubular aggregates on muscle biopsy, decremental responses to slow repetitive stimulation and responsiveness to cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,4 DAP. Unlike GFPT1 CMS, CK values are reported to be normal. Consistent with DPAGT1’s role in glycosylation in locations other than the NMJ, mutations of this gene may also produce a severe, neonatal multisystem disorder referred to as type 2 that may include seizures, microcephaly, ventilatory distress, hypotonia, and behavioral abnormalities. The determination of phenotype appears to be based on mutation location.

Asparagine-related glycosylation plays a critical role in protein folding, transport, localization, and folding. Recessively inherited mutations in these two genes that contribute to this process have been recently reported to result in CMS that bear many similarities to DPAGT1 and GFPT1 CMS. Most affected individuals reported to date have had a limb-girdle phenotype affecting limb muscles preferentially, typically symmetrically with proximal predominance. Scapular winging may occur, contractures are commonplace and a high-arched palate has been described. Facial weakness may occur but extraocular muscle involvement is not a typical feature of the disease. Learning disability may occur. Onset age may range from infancy with hypotonia to adulthood although initial symptoms in the late first decade would seem to be the norm. Wheelchair dependency may or may not occur. A decremental response to slow repetitive stimulation and responsiveness to cholinesterase inhibitors are the norm. Tubular aggregates may be found on muscle biopsy. CK is usually normal but may be minimally elevated.

The differential diagnosis of CMS in the neonatal period is largely that of the floppy infant (Table 1-1). In the presence of ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, particular consideration should be given to transient neonatal autoimmune MG, certain congenital myopathies, mitochondrial myopathy, and myotonic muscular dystrophy (Table 1-8). Later in infancy, infantile botulism should be considered, particularly with an acute to subacute onset, and symptoms of cholinergic dysautonomia such as sluggish pupils and constipation. In childhood, autoimmune MG and rarely autoimmune LEMS require consideration. When the phenotype is dominated by a limb-girdle pattern of weakness, numerous myopathies and spinal muscular atrophy are the primary considerations. The latter may be suspected by the presence of fasciculations, tremor, or a neurogenic pattern with EDX, or if necessary, muscle biopsy.

Routine laboratory testing is of limited value in CMS. Serum CK levels are of little value in that they are characteristically normal or modestly elevated similar to other neuromuscular disorders with which CMS might be confused.124 CK testing may be helpful in distinguishing two similar phenotypes DPAGT1 and GFPT1 CMS as it is elevated in approximately half of the latter patients but is normal in all reported cases of the former to date.134 These two disorders as well as deficiencies in ALG2 and ALG14 may also be distinguished from all other CMS as they are the only CMS reported to demonstrate tubular aggregates with light microscopy and oxidative staining of a muscle biopsy specimen.132,133,138

The diagnosis of CMS, if clinically suspected, is further supported by the combination of abnormal EDX testing results and edrophonium testing when present, coupled with the absence of serological markers of autoimmune MG and LEMS. Edrophonium testing is positive in most CMS including the presynaptic disorders, AChR deficiency, and the fast-channel syndromes. End plate AChE deficiency, occasional cases of the slow-channel syndrome, and Dok-7 syndromes are notable exceptions.

At times, identification of motor unit variability, after discharges with routine motor conductions, or a decremental response to slow repetitive stimulation may lead to an unanticipated discovery of a CMS. None of these EDX findings are however, adequately sensitive or specific to allow for a definitive CMS diagnosis in many cases. Afterdischarges are typically identified in only three forms of CMS: AChE, agrin, and AChR receptor (associated with the slow-channel syndrome) deficiency. In all three, the afterdischarges represent prolonged postsynaptic depolarization. Afterdischarges may also occur with neuromyotonia, envenomation with K+ channel poisons, intoxication with organophosphate or other anticholinesterase agents, and certain muscle channelopathies.

As described below and summarized in Tables 26-2 and 26-3, not all CMS may be identified by abnormal EDX testing. Repetitive stimulation at various frequencies and stimulated SFEMG are the most frequently used techniques in the pediatric age group. Caution in interpretation is required however, as there is limited normative data in infancy.175 It would appear that in a full-term normal newborn, no decremental response to slow repetitive stimulation is demonstrable in spite of what may be an immature NMJ. A decrement in response to frequencies of 5 Hz or more has been reported in normal newborns so that techniques that utilize higher stimulation frequencies including stimulated SFEMG must be interpreted with caution.175

Decremental responses to repetitive stimulation have been described in all forms of CMS although certain forms (ChAT deficiency) require prolonged stimulation at higher rates (10 Hz) in order to provoke the decrement (Fig. 26-5).126,128,131,133,138,139 As with autoimmune MG, a decremental response in these syndromes is expected in any clinically weak muscle and in some but not necessarily all clinically unaffected muscles. Standard repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) protocols may have to be modified in order to identify abnormal NMT in some syndromes. The decrement in AChE deficiency and the slow-channel syndrome typically becomes greater with faster rates of stimulation.126 In ChAT deficiency, 10-Hz RNS for 5 minutes may be required to identify a decremental response.125,127,152 A small increment in response to fast repetitive stimulation has been reported in ChAT deficiency as well.127 Like acquired, autoimmune LEMS, the Lambert–Eaton form of CMS is characterized by a low baseline CMAP and an incremental response of up to 2000% with 20–50-Hz repetitive stimulation.156

MUAPs that are polyphasic and smaller in both amplitude and duration may occur in CMS as a result of at least two mechanisms. Neuromuscular blockade at individual NMJs may reduce the number of single fiber action potentials that contribute to the normal MUAP size and configuration. In addition, in AChE deficiency and the slow-channel syndrome, an end plate myopathy may develop as a result of excessive end plate stimulation resulting in smaller MUAPs as well.127

A definitive diagnosis of CMS remains challenging in most cases. Historically, a CMS diagnosis was arrived at with the confluence of a characteristic phenotype in a young person with negative serological testing for autoimmune MG, EDX evidence of a DNMT, with or without a positive response to cholinesterase inhibitors and when present, a compatible family history. Confirmation was achievable only by a selected group of laboratories capable of ultrastructural analysis of NMJs and in vitro physiological testing of NMT.

Genetic testing now provides at least in principle, a more direct and efficient manner in which to not only confirm a CMS diagnosis but also to identify the genotype as well. To date, 18 CMS genotypes have been identified.139 Genetic testing in CMS however, is fraught with a number of limitations including availability and cost considerations.125 Identification of pathogenic mutations from benign polymorphisms is not always easy. Mutational analysis is also incapable of defining a kinetic defect in association with an identified subunit mutation. Kinetic defects, important in therapeutic decision making, are identified only with the use of in vitro microelectrode or single-channel patch clamp recordings.166 It is estimated that successful genotyping can occur in half to as many as 90% of CMS cases.126,127,176 If genotyping is an available option, test selection should be judicious. Considerations should be directed by the phenotypic and epidemiological clues provided in Tables 26-2 and 26-3 as well as by genotype frequency.

Light microscopic examination of muscle biopsy is of limited value in CMS but is often performed in consideration of the more likely possibility of myopathy, particularly in older individuals. Perhaps the most specific potential finding would be the presence of tubular aggregates. Although neither sensitive nor specific for CMS, they are a potential finding in limb-girdle phenotypes of CMS including GFPT1, DPAGT1, and ALG2/ALG14.124,131–133,135–138 Otherwise, light microscopic findings are of limited benefit. In the majority of cases, they neither distinguish CMS from other neuromuscular diseases nor do they aid in the definition of a specific CMS genotype.

A number of nonspecific, largely myopathic findings have been described in muscle biopsy specimens from CMS patients. Type 1 fiber predominance is perhaps the most common of these and has been described in rapsyn, Dok-7, GFPT1, and MuSK CMS.124,130,141,146,171 Other features described in other CMS including Dok-7, GFPT1, plectin, and MuSK include type 2 fiber atrophy/hypotrophy, isolated myofiber necrosis and regeneration, diminished oxidative stain uptake, ragged red fibers, increased frequency of internal nuclei, fiber splitting, and subsarcolemmal nuclear chains.124,140,141,146,171 Autophagic vacuoles that may stain with acid phosphatase and may contain glycogen have been described in DPAGT1 and GFPT1 CMS.131,132 Neurogenic features of small grouped atrophy and target formations have been described.131,132,146,156

Ultrastructural abnormalities of the NMJ occur in most CMS.125 They are not syndrome specific. Simplified junctional folds appear to be the most common abnormality in some but not all end plates in many of the disorders and are frequently associated with reduction in the number of AChRs.131,140 This finding has been reported in a number of syndromes including the slow-channel AChR kinetic disorder, and the AChE, LAMB2, rapsyn, plectin, MuSK, LRP4, GFPT1, and Dok-7 forms of CMS.125,130,131,139,140,171 The pattern of simplification of the junctional folds varies however, being focal in synaptic disorders and diffuse in many postsynaptic disorders such as AChR ε subunit or rapsyn deficiency.129 In the synaptic CMS, that is, LAMB2, agrin, and AChE deficiency, as well as in MuSK CMS, the ultrastructural findings may include reduction of the axon terminal size, partial encasement of the nerve endings by Schwann cells, widening of the primary synaptic cleft, and invasion of the synaptic cleft by the processes of Schwann cells in addition to focal simplification of postsynaptic folds.129 This observation of abnormal presynaptic morphology in a synaptic disorder reflects that the pathophysiology of individual CMS may extend beyond the primary site of involvement. In Dok-7 myasthenia, myeloid structures may populate the junctional cytoplasm. Nerve terminals ending as growth cones without AChR contact has been described in MuSK CMS.173

In AChE deficiency and the slow-channel syndrome, prolonged end plate current produces postsynaptic cationic overloading resulting in an end plate myopathy.129 The histological features of this are characterized by subsynaptic degenerative abnormalities, autophagic vacuoles, dilated sarcotubular elements, increased lipid droplets, and apoptosis of junctional nuclei occurring as a consequence of postsynaptic cationic overloading. In the presynaptic disorder, CMS with a paucity of synaptic vesicles, electron microscopy demonstrates the feature that defines the condition.127 Ultrastructural abnormalities do not occur routinely however, in all CMS. In agrin deficiency, congenital LEMS, and the fast-channel kinetic syndrome of AChR deficiency, the postsynaptic regions are reported to be ultrastructurally normal.152

The efficiency of NMT is dependent on numerous interrelated components. Optimal NMT requires adequate synthesis of ACh and its packaging and positioning of the resultant synaptic vesicles at the active zones of the presynaptic terminal. Equally important is adequate quantal content or the number of vesicles released as a result of a nerve action potential and the resultant amplitude and duration of the end plate current that the vesicular–end plate interaction produces. This is in turn dependent on synaptic metabolism of ACh that is neither inadequate nor excessive, as well as the normal positioning, clustering, positioning and kinetics of both the ACh and Na+ channels on the peaks and troughs of the end plate folds, respectively.

CMS result from single-gene mutations resulting in abnormal structure or function in one or more of these components of NMT. In each instance, there is a resulting alteration in end plate current, impaired generation of myofiber action potentials, and as a consequence, reduced strength and stamina of voluntary muscles. With the majority of genotypes, a reduction in end plate current occurs. In two of these disorders however, AChE deficiency and the slow-channel kinetic disorder of the AChR, the current is excessively prolonged.165 Although adverse pathophysiological events are typically characterized as occurring at a singular presynaptic, synaptic, or postsynaptic region, many of the CMS will have secondary consequences that affect additional NMJ loci.

In ChAT deficiency, impaired resynthesis of ACh compromises NMT by progressively depleting quantal content. This along with miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) and EPP amplitude are normal at rest but decline with repetitive stimulation at 10 Hz for 5 minutes with subsequent gradual recovery.152 CMS with a paucity of synaptic vesicles is associated with a reduced density of synaptic vesicles at the active zones. The probability of quantal release, that is, proportion of vesicles released/nerve action potential, is normal.125 Conversely, the LEMS variant of CMS is associated with reduced quantal content with a reduced probability of quantal release.125 Like its autoimmune counterpart, it is defined by the characteristic EDX pattern of a reduced CMAP amplitude at rest, a decremental response to 2–5 Hz repetitive stimulation and an incremental response to faster rates of repetitive stimulation or exercise. The exact mechanism by which this occurs is not fully understood.125 No mutations of VGCC-related proteins have been identified to date.127 A failure to respond to 3,4 DAP suggests that congenital LEMS is not a consequence of disordered calcium channels.152

With AChE deficiency, the most common of the synaptic disorders, the absence of AChE prolongs the lifetime of ACh in the synaptic space and as a consequence, the duration of the MEPP and EPP. The duration of the synaptic current outlasts the refractory period of the muscle fiber which overstimulates the postsynaptic region. Neuromuscular transmission is impaired by multiple mechanisms including loss of AChR from the degenerating junctional folds and desensitization from ACh overexposure. In addition, there are presynaptic effects with the small and often Schwann cell–encased nerve terminals associated with reduced quantal release. In addition, the excessive stimulation promotes cationic overloading resulting in an end plate myopathy.

In view of the integral role of laminin as a component of the basal lamina, and the critical role of the basal lamina in the creation and configuration of the motor end plates, LAMB2 deficiency is hypothesized to adversely affect the development of the complex end plate anatomy.127 LAMB2 deficiency also associates with abnormal nerve terminals that are both small and encased by Schwann cells. Widening of the synaptic space and junctional fold are additional consequences as is the demonstration of decreased MEPP amplitude.125,152 Agrin is bound to laminin on the synaptic basement membrane with the possibility that agrin deficiency (described below) has a synaptic as well as postsynaptic pathogenesis.151

The most common postsynaptic disorders involve mutations of AChR subunits, most commonly ε. Again, mutations may produce a deficiency and/or a kinetic disorder. With receptor deficiency, as the name implies, the AChRs at the NMJ are patchy in distribution and reduced in number with a proportionate reduction in end plate current.125,165 The pathophysiology of the AChR mutations resulting in kinetic disorders differs dependent on whether the problem is one of delayed (slow channel) or premature (fast channel) AChR closure subsequent to the generation of an initial muscle fiber action potential. The pathophysiology of the slow-channel syndrome is similar to AChE deficiency including depolarization block and the development of an end plate myopathy from excessive stimulation.125 The pathophysiology of the fast-channel syndrome includes reduced ACh affinity for the AChR, shortened duration of the EPP and as a consequence, diminished Na+ activation.165 AChR density on the postsynaptic fold is normal.177

Many of the CMS relate to mutations of genes that produce proteins integral to the proper placement and aggregation of AChRs on which optimal NMT is dependent. Agrin is secreted by the distal motor nerve terminal and binds to LRP4. The LRP4-agrin complex activates MuSK which in turn with Dok-7 stimulates rapsyn to concentrate and anchor AChR at the NMJ.93,151