3

Swords of Power

According to the familiar story, Arthur became king at the age of fifteen by drawing the sword Excalibur from a block of stone. It was said that the man who could accomplish this task was destined to rule the Britons, and all before Arthur had failed. Could this seemingly fanciful yarn be based on some kind of historical event? Surprisingly, historians have suggested a potentially authentic origin for the sword-and-stone story. It concerns the way swords were made. Swords were cast in a stone mold; when the molten metal cooled and set, the finished sword blade was literally removed from a stone. Some scholars have suggested that this is the origin of the Arthurian story of a sword coming from stone. Nice idea, but personally I don’t buy it. Nearly all swords were made this way. If this was the origin of the legend, wouldn’t it make King Arthur’s purportedly unique sword as common as any other? There is, though, another theory regarding the birth of the legend that involves a real sword stuck in an actual stone.

Remember I said that by the time of the Glastonbury grave discovery, the notoriety of the Arthurian legend had spread as far south as Italy. Well, in the Italian province of Tuscany, local people are still proud to assert that the sword-and-stone story began there. In a chapel near Saint Galgano Abbey in the district of Chiusdino, there is a rock from which a sword hilt protrudes. The weapon is said to have been plunged into the rock in 1180 by an Italian knight called Galgano after he renounced warfare to become a monk. When he died the pope made him a saint, and a chapel was built around the sword in the stone, which had become regarded as a holy relic. Quite how the knight managed to secure a sword in solid rock is something of a mystery, but however he did it, it stuck fast. As it was said to possess miraculous healing powers, during the Middle Ages various pilgrims—including a couple of rival abbots—tried to steal the relic, but none could remove it from the stone. To deter such attempts the abbey monks put mummified hands on display, declaring them to have belonged to would-be thieves whom God had punished by having them devoured by wolves, evidently leaving behind the offending appendages.1 Nowadays, the relic is protected by a thick Perspex acrylic screen, so there’s no point going there to try your hand. (No pun intended.)

The sword visible today would seem to be the original item, as metal testing has dated the weapon to around AD 1200. This dating has led some researchers to agree with local opinion that Galgano’s sword inspired the Arthurian sword-and-stone idea, as the theme first appeared in the Arthurian romances at this time. Medieval authors, they suggest, interpolated the episode into the continually evolving King Arthur story. The oldest known inclusion of the sword-and-stone motif in the King Arthur saga is by the poet Robert de Boron (the same man who introduced the Holy Grail into the Arthurian romance) in a poem titled Merlin.2 Robert’s Merlin can be dated to around the year 1200, so the anecdote of the Galgano sword could well have been known to him. However, there is one vital difference between Robert’s tale and the story of Galgano. It may come as something of a surprise to those familiar with the modern version of the story: in Robert’s original tale, the sword is not embedded in a stone but in an anvil, which stands on a stone. Later writers tended to leave out the anvil in favor of the sword-in-the-stone theme we know today, and this might well have been influenced by the account of the Galgano sword. The sword-in-an-anvil motif, however, would suggest that the Arthurian episode was inspired by a separate source and merely modified after the fame of the Italian event. In fact, some scholars have advocated that the Galgano story was inspired by a preexisting Arthurian tale. Either way, it was the location of the incident in Robert’s poem that was of interest to me. Arthur does not gain his sword in some remote village in Italy but in the capital city of England.

Although other medieval authors had concentrated on the sword in the stone, rather than the anvil theme, Sir Thomas Malory in the fifteenth century returned to Robert de Boron’s original rendition. Indeed, he retells Robert’s account almost verbatim. As Robert’s poem only survives today in fragmented form, I decided to concentrate on Malory’s The Death of Arthur as my starting point, as he appears to have had a full copy of the Merlin poem in his possession. As I said, most people are familiar with the story of how Arthur, as a young man, proves himself rightful king by drawing the magical sword from a stone when no one else could. In the acclaimed movie Excalibur of 1981, and in many other Hollywood, TV, and literary portrayals of the event, Arthur pulls Excalibur from a large boulder or stone block that had stood defiantly in woodland or open countryside for many years. Besides originally being in an anvil, it may come as a further surprise to know that this modern rendering of the tale differs considerably from the original on three other accounts. First, the weapon is not Excalibur but a completely different sword. Second, the sword had not been there for years but suddenly appeared. And third, the event does not take place in some isolated setting but right in the heart of London.

Malory actually provides a specific location in London for the event. According to him, after a service on Christmas Day in what he describes as “the greatest church in London,” when the congregation are leaving, they are shocked to see something in the churchyard that had not been there before: a large square, stone block upon which stands an anvil, and embedded in the anvil is a sword, the hilt and part of the blade protruding. Around the sword—whether on the anvil or the stone is not clear—are words written in gold: “Whosoever pulls this sword from this stone and anvil is born the rightful king of England.” (At the time Malory was writing, the word England was often used to refer to Britain as a whole [see chapter 7].) The greatest nobles try and fail to remove the sword, until New Year’s Day when Arthur finally succeeds.3 Leaving aside the likely reality of the stone-pulling incident itself for a moment, does the original setting of the event where Arthur is proclaimed king imply that the origins of a historical King Arthur might be found in London?

Malory follows Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version of Arthur’s birth at Tintagel Castle, after his father King Uther sleeps with Igraine. As trouble is brewing in the nation and the baby’s life is in danger, Merlin persuades the king to allow him to bring up the child in secret. This he does by giving the infant to one Sir Ector and his wife who raise him as their own in an undisclosed location. In fact, it is they who call the child Arthur, so even Uther and Igraine are unaware of their son’s true name. When Uther Pendragon dies without an heir, the country slides into civil war, and for many years, without a king, the barons struggle for supremacy while foreigners plunder the country. Only a new, undisputed king can possibly hope to return peace and prosperity to the land. All this time Arthur remains ignorant of his lineage, believing Ector to be his father.4 One day, when Arthur is fifteen, he is out riding with his adopted father and elder brother Sir Kay, on their way to tournaments to be held beside the churchyard where the sword in the anvil stood. En route, Kay discovers that he has forgotten to bring his sword and asks Arthur to return home to fetch it. Failing to find his brother’s sword at home, on his return journey Arthur gets lost and ends up in the churchyard where he sees the sword in the anvil. Unaware of its significance, he decides to take it for his brother to use. With no one around he effortlessly pulls the sword from the anvil where all others have failed. Inadvertently, Arthur has proved himself rightful king. When news spreads and the barons gather to dispute that such a lowborn individual could possibly be their ruler, Merlin—once the revered advisor to Uther Pendragon—appears on the scene to reveal Arthur’s true identity as the dead king’s son and true heir to the throne.5

Once more the historicity of these events should not concern us at present. What’s important is that they provide a specific location for Arthur’s beginnings. Malory suggests that the place where Arthur had been living was fairly close to the London churchyard where the sword in the anvil stood. He and his adopted family had been on their way to take part in the very tournaments that were to be held on New Year’s Day beside the London churchyard, and they arrive there well within a day. In fact, we are told that Sir Ector even conducts his daily business within the town of London. Today London is a huge city covering an area of seven hundred square miles, but in the Middle Ages it measured little more than a single square mile. Accordingly, Arthur’s childhood home was evidently thought to have been in the countryside not far from the city. Although an unladed horseman might cover thirty-five miles on a good day, in midwinter on mud tracks, fifteen miles would be about the limit. As we are told that Arthur first returned home and, when he failed to find his brother’s sword, rode to the tournament site to arrive well before the event began, we can deduce that Arthur was imagined to have lived fairly close to where the sword in the anvil stood. Yes, I realize that there are some rather glaring inconsistencies in the account. How come Sir Kay forgot to take his sword to a tournament in which he was to take part? And how come Arthur managed to get there before his family, after a detour back home? However, as I have said, it was the locations Malory had in mind that specifically interested me, rather than the action. If he took the story from Robert de Boron’s twelfth-century original, which Robert in turn claimed to have taken from an earlier account, then it is possible that this medieval tale concerning Arthur becoming king originated with a much older, though now elaborated legend regarding Arthur spending his youth near London (in fact, in what is now within the boundary of London itself) and being proclaimed monarch in the city. So could such a legend genuinely relate to the time Arthur is said to have lived, around AD 500?

Malory says that the churchyard in question surrounded the “greatest church in London.” Today that would be Saint Paul’s Cathedral, as it was in Malory’s time, and indeed right through the Middle Ages. Malory even names Saint Paul’s as being the possible location for the episode, saying, “Whether this [church] was Saint Paul’s or not, the French book does not say.”6 (The French book to which he refers appears to be Robert de Boron’s Merlin.) Nonetheless, Saint Paul’s had been London’s most important church for centuries, so it’s hard to imagine what other church it could be. (Westminster Abbey—where England’s kings and queens are crowned and royal marriages are held—was indeed a great church, but until the sixteenth century, well after Malory’s time, Westminster was a different city from London, geographically separated by open countryside.) Although Saint Paul’s went through many periods of reconstruction, culminating with the building we see today erected in the late 1600s, the location is recorded as having been the seat of the bishops of London since 604. This is significant, as the seats of bishops were cathedrals, and there had been bishops of London since the Romans ruled Britain in the fourth century.7 It is possible, then, that there had been a Saint Paul’s Cathedral during the time Arthur is reckoned to have lived, around AD 500. But what could possibly be behind a story as fanciful as the sword and anvil or stone?

Even though the sword was originally depicted as being in an anvil, it is the stone upon which it rested that ultimately assumed the greater importance. Strangely, although in Robert de Boron’s account the sword is in an anvil, he makes no reference to its significance. Neither indeed does Malory. Moreover, the fact that most of the dozens of Arthurian authors between Robert and Malory omitted the anvil altogether further suggests it was the stone rather than the anvil that was considered the essential element of the anecdote. When I read Robert’s account specifically saying that the stone represented “the power of Christ,” the episode took on a completely new perspective.8 Although it is said that the sword and anvil mysteriously appeared during mass, it is not made clear by either author, Robert or Malory, whether or not the stone was already there. If it was, then, going by Robert de Boron’s words, the stone actually fitted into a historical context.

From the time the newly converted Roman Christians brought their faith to Britain, in the mid-fourth century, they adopted a policy that may seem unusual to us today. They did not immediately try to eradicate paganism, rather they replaced it gradually. Paganism was not outlawed by the Romans; it was merely discouraged. In fact, the Romans adopted this policy throughout their empire as part of a clever strategy to convert pagan peoples called Interpretatio Christiana, meaning “Christian Reinterpretation.” Rather than expect folk to immediately convert and abandon generations of deeply held beliefs, the canny Roman Church allowed the process to occur slowly. Saints progressively supplanted the old gods, pagan festivals little by little replaced days of pagan observance, and temples were gradually substituted for churches. For example, the traditional date for the birth of the sun god Sol Invictus became Christmas, the birth of Christ; temples to the moon goddess Diana became shrines to the Virgin Mary; and the regular bull-blood-drinking feasts to honor the god Mithras were replaced by the weekly Mass of the Eucharist, where consecrated wine was drunk; and most importantly for our current investigation, there are numerous examples throughout the British Isles of churches built on formally sacred pagan sites. In several such examples there still survive ancient stones, once venerated by the pagan Britons as representing their gods, which had been reconsecrated as Christian monuments. For instance, in Llanwrthwl churchyard in Wales in western Britain, there is a six-foot such stone; in Saint Clement churchyard in Cornwall in southwest England, there stands a ten-foot stone; and in the churchyard of Rudston in Yorkshire in northern England, there is a massive twenty-five-foot pagan megalith. Many churches have smaller such stones, such as Lanivet and Cuby churches, both in Cornwall. As part of their policy of Interpretatio Christiana, the Roman Christians deliberately built churches right next to these stone monoliths and blocks, which no longer represented the ancient deities, but the power of Christ. As this is exactly how Robert de Boron describes the stone in the Arthurian event, and as it is actually said to have stood in the churchyard, could it have been such a reconsecrated monument? Was there any historical evidence that such a stone had once been in the churchyard of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London?

Near Saint Paul’s there is indeed a block of limestone that still survives that local tradition holds to be the very stone from which Arthur drew the sword. Approximately seventeen inches high, twenty-one inches wide, and twelve inches thick, it is known as the London Stone (see plate 3). (Evidently it was once larger, closer to the size of the Arthurian stone described by Robert de Boron.) This ancient stone is recorded as marking the place of legal declarations; moreover, it was specifically associated with a sword of power. Surviving records dating from as early as eleven hundred years ago refer to the stone as having great ceremonial significance: it marked the traditional place where laws were passed and proclamations issued; and after 1189, when Henry Fitz-Ailwin became London’s first mayor, the inauguration ceremony expressly required the new incumbent to strike the stone with his sword to validate his entitlement to govern the city. Just how far back the tradition between the London Stone and a sword of authority actually goes is unknown, as earlier records are scanty, but it is quite possible that it had existed in some form or other for centuries. Today the stone is set into a niche in the wall of a building opposite London’s Cannon Street Station, protected by a glass case and an iron grill, some ten minutes’ walk from Saint Paul’s. It has only been there since 1962 and had previously been moved on several occasions as new buildings were erected, and there are no records earlier than the 900s to tell us where it originally stood. Nevertheless, it has always been close to Saint Paul’s, and so it might well have originally stood in the cathedral churchyard as local legend asserts. I therefore concluded that the London Stone could indeed have inspired the setting for the sword-and-stone episode as related by both Thomas Malory and originally by Robert de Boron (although they both have an anvil on the stone), particularly since Robert penned his story just a decade after Henry Fitz-Ailwin’s inauguration as mayor. A genuine stone in Saint Paul’s churchyard that was associated with civic authority and with a sword of power: an ideal theme—and one familiar to readers at the time—for Robert de Boron (or his source) to have incorporated into the ever-evolving legend of King Arthur.

All the same, although I might have found the origin of this particular Arthurian theme, it might simply have been a medieval interpolation. The stone may well have been here during the period Arthur is said to have lived—in the 1960s, Museum of London archaeologist Peter Marsden suggested the stone was of pre-Christian Roman origin—but there are no records concerning its ceremonial function or indeed anything about it earlier than around AD 900.9 So I was left with no more evidence to associate a historical King Arthur specifically with the city of London than to link him with any of the proposed Camelot sites. Nevertheless, I did formulate an idea as to how the notion of a sword imbedded in an anvil upon a stone might have originated with a historical Arthur. It was the odd combination of the two items that got me thinking.

As we have seen, like Malory, Robert fails to explain the anvil’s significance, while most medieval authors chose to leave it out altogether: so why the two items? There was, I discovered, an intriguing phonetic peculiarity concerning the words stone and anvil. Before continuing I need to explain whom King Arthur and the Britons were seeking to repel. I have mentioned that he was fighting the Anglo-Saxons, but this is a simplification. The Angles and the Saxons were originally different peoples from adjacent regions in the far north of modern Germany. The Angles invaded the northeast and east of England, while the Saxons invaded the south and southeast. So if he did unite the Britons around AD 500, Arthur would either have been fighting the Angles or the Saxons but presumably not both at the same time. Ultimately, the invaders formed an alliance, and by the 700s they where collectively referred to as the Anglo-Saxons, and ultimately just the Saxons, but during the historical Arthurian period—the post-Roman era—they were separate invaders. With this in mind, I found it fascinating that in Latin (the Roman language spoken widely throughout Britain in the early Dark Ages), the word for a large stone, such as that on which the anvil stands in the Arthurian episode, is saxum, a word that sounds very similar to Saxon. So similar, in fact, that at some point the two words could easily have been confused. Add to this that the English word anvil is similar to the name Angle, and it is possible that an original version of the story portrayed Arthur taking the sword from the Angles and Saxons—that is, the fight out of them (he seized the initiative from his enemies)—and the words ultimately became mistranslated as “anvil” and “stone.” Might this eventually have evolved into the legend of Arthur drawing a sword from an anvil and stone?

So was this the evolution of the Excalibur story? A theme incorporated through mistranslation into the Arthurian legend during the Dark Ages and popularized in the Middle Ages by the story of Galgano’s sword, while a setting for the event was based on the traditions associated with the London Stone around the year 1200? Well—yes and no. It could be the origin of the sword-and-stone motif but not of Arthur’s enchanted sword. As I mentioned earlier, in the medieval Arthurian romances, the sword in the stone (or anvil) was a completely different weapon from the famous Excalibur. So could the tale of Excalibur itself help me in my quest?

Most people’s familiarity with the King Arthur story comes from its various renditions on TV and in the movies, where the two swords are usually one and the same. But in the medieval tales, right up to Malory’s time, Excalibur was not the sword in the anvil or stone. Arthur obtains Excalibur well after he has drawn the unnamed sword that proves him king. Excalibur, as the name of Arthur’s second sword, appears to originate with the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 1130s where he calls it Caliburnus, or Caliburn for short, leading to later authors using the more lyrical name Excalibur.10 Initially, it was not endowed with magical properties; rather, as the French poet Chrétien de Troyes in his Perceval composed in the 1190s explains, it was “the finest sword ever made, which sliced through iron as if through wood.”11 In other words, it was an exceptionally well-made weapon but not enchanted. It was not until the early 1200s that it took on a mystical aspect. From then on different authors attributed various supernatural qualities to Excalibur: when drawn its blade shone so brightly that it blinded the enemy; its wielder could not be defeated if he kept faith; it could only be lifted by the true king; and it had the power to dispel witchcraft. Even its scabbard was said to possess magical properties, as anyone wearing it would not bleed from wounds.

But these were all medieval tales, written down well over half a millennium after Arthur is said to have lived. Are there any stories concerning a special sword associated with the fabled king before the Middle Ages? There are, and they survived in an area of Britain not occupied by the Anglo-Saxons: Wales in the west of Britain. Wales had and still has a separate language from the rest of Britain. In the Welsh language—derived from the tongue of the native Britons, as opposed to English, which originated with the Anglo-Saxons—there are a number of old stories featuring King Arthur that seem to date from before the medieval Arthurian romances. In some of these Welsh narratives, such as the tale of Culhwch and Olwen (Culhwch, pronounced “Cul-hoo-k” or “Ilhuk,” is a legendary hero and Olwen is his lover), which dates from the eleventh century,12 and The Spoils of Annwn,13 dated on linguistic grounds to around AD 900—over two centuries before the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth—Arthur’s sword is called Caledfwlch (pronounced “Caled-voolch”), meaning “unbreakable sword.” (Specifically, the name appears to be a combination of the Welsh words caled, meaning “hard,” and bwlch, meaning “breach,” that is, it could cut through anything.) It seems likely that this is where Geoffrey derived his name for Arthur’s sword, latinizing it as Caliburnus, or Caliburn, as it is usually abbreviated in English translations. So it seems that the tradition regarding Arthur having a unique sword, whether magical or not, did exist before Geoffrey of Monmouth and the subsequent Arthurian romances of the Middle Ages. But could the Excalibur legend help me narrow my hunt for a specific location concerning Arthur’s origins? One feature of the story, I decided, might indeed prove helpful, particularly in my search for Arthur’s grave, and that was the tale of the Lady of the Lake.

Fig. 3.1. Areas in southern Britain occupied by the Britons, Angles, and Saxons around AD 500.

The Lady of the Lake first appears in a series of Arthurian tales known as the Vulgate Cycle. (The term cycle, in this context, is used for stories or poems dealing with the same themes.) Coming from the Old French vulgāre, meaning “to popularize,” they were composed by a series of anonymous authors from around 1220 to 1240. (Strictly speaking, those that were composed after 1230 are usually referred to as Post-Vulgate by literary scholars, but for convenience I shall use the term Vulgate to cover them all.) In the Vulgate stories the Lady of the Lake is a mysterious water nymph from whom Arthur originally receives Excalibur. Eventually, it is returned to her in the now famous scene. After his final battle, when Arthur lies mortally wounded, he orders his knight Girflet to cast Excalibur into a nearby lake. After twice disobeying the king’s wishes, the knight reluctantly consents. When the sword is thrown, the arm of the Lady of the Lake rises from the surface, catches the weapon by the hilt, and takes it down into the watery depths.14 This is the incarnation of the tale later elaborated by Thomas Malory, although in his version it is Sir Bedivere and not Sir Girflet who assumes the role. While other medieval authors cast Galahad, Lancelot, or even Perceval in this part, the event itself had become firmly entrenched in the saga by the end of the Middle Ages. Although the episode would seem to be one of the more fanciful aspects of the Arthurian story, it was worth considering the possibility that the legend could lead me to a real location where Arthur was originally thought to have died. Obviously, if he historically existed, finding where he died might lead me to the general vicinity of his grave. So where, exactly, was the lake in question believed to have been?

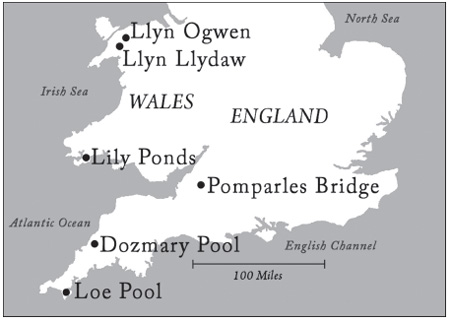

So often in the Arthurian saga, locations are hard to identify. As I had found with Camelot, none of the medieval authors tells us where the Excalibur lake actually is. Even Malory, who did identify Camelot as being Winchester Castle, is silent on the matter. And as you might expect, there are a number of lakes in the British Isles that local folklore asserts to be the resting place of Excalibur. In Wales, for instance, there is Lily Ponds near the town of Bosherston in South Wales, and Llyn Llydaw and Llyn Ogwen in Snowdonia, North Wales (llyn is Welsh for “lake”); Cornwall has Loe Pool near Porthleven and Dozmary Pool on Bodmin Moor; England boasts a stretch of the River Brue at Pomparles Bridge near Glastonbury; even Scotland has an Excalibur lake, Loch Arthur near the town of Beeswing. However, all but one of these can pretty much be discounted. Three are undoubtedly relatively recent inventions. Lily Ponds did not even exist until the 1700s, when it was created as a garden feature by the landowner; Loe Pool was only brought into the story by the poet Tennyson in the late 1800s; and there are no known Arthurian tales or poems whatsoever before modern times that mention Scotland’s Loch Arthur. Two are fairly spurious. Pomparles Bridge is not named in any early Arthurian story. It is only referenced in passing in association with Excalibur by the antiquarian John Leland in the 1500s, who says that local people believed it to be the place where Arthur’s knight threw the sword to the Lady of the Lake. I dismissed this site quite quickly. After all, if this was the location the romancers had in mind, then the mysterious water nymph would have to be the Lady of the River. Llyn Llydaw’s claim does come from a medieval tale, titled Vera Historia Morte de Arthuri (The True History of Arthur’s Death); dating from around 1300, it locates Arthur’s last battle nearby. As much concerning Arthur in the work is at odds with earlier authors, it is generally considered as an unreliable source by literary scholars. And one is based on an irrelevancy. Llyn Ogwen’s case comes from an indirect association referenced in a series of short medieval Welsh poems known as Trioedd Ynys Prydain (The Triads of Britain).15 In one of the triads (which we shall be discussing later), it is said that Arthur’s knight Sir Bedivere is buried on Mount Tryfan, which overlooks the lake. According to Thomas Malory in the mid-1400s, it was Sir Bedivere who cast Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake, and consequently local folklore assumed the lake beside his purported burial site to be the lake in question. However, Bedivere was not the knight originally associated with the Lady of the Lake episode. The oldest known rendition of the story is found in one of the Vulgate stories, known as the Vulgate Mort Artu (Death of Arthur), composed around 1230, over two centuries before Malory’s time, and here the knight who throws Excalibur into the enchanted lake is not Bedivere but Sir Griflet.16 Accordingly, whether or not Bedivere was buried near Llyn Ogwen is completely immaterial to its case for it being the Excalibur lake, and since Bedivere is irrelevant, the case collapses. This left me with Dozmary Pool, a small, remote lake with a surface area of around thirty-seven acres in the bleak, windswept uplands of Bodmin Moor in the county of Cornwall. As it was the most famous of the lakes linked to the Arthurian story, and with a stronger case than most, I felt it warranted further investigation.

Dozmary Pool’s claim to being the lake where Arthur’s sword was cast lies exclusively with its proximity to a place where Arthur is said to have fought his last battle: a field in an area called Slaughterbridge, only ten miles away. The bridge itself crosses the River Camel, which various Arthurian scholars have asserted to be the location of Arthur’s final conflict. Many of the medieval Arthurian narratives affirm that King Arthur’s last battle was fought at a place called Camlann; it is even mentioned in an older chronology known as the Welsh Annals, compiled as early as 955.17 As no place still bears that name, the location of the Battle of Camlann is open to speculation, and one of the favorite contenders has been Slaughterbridge, some Arthurian researchers suggesting that the name of the river at the site, the Camel, derived from the word Camlann. We will be returning to the Battle of Camlann itself and its various possible locations in chapter 12, but for now we need to establish the authenticity or otherwise of this particular site in order to consider the likelihood of the nearby Dozmary Pool as the Excalibur lake. Today, there is an Arthurian visitor center at Slaughterbridge, which includes an exhibition room, nature trail, scenic garden, children’s play area, and a gift shop. The area, some twenty acres in size, also includes the purported battle site where lies an inscribed horizontal stone around nine feet long and three feet wide, known locally as King Arthur’s Stone, which is said to mark the very spot where Arthur fell. The stone has been reliably dated to the early sixth century and so could well date from the period Arthur is said to have lived.

On the face of it, Slaughterbridge is a good contender for the site of Arthur’s last battle. Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing in the 1130s, says Arthur’s final battle was beside a river somewhere in Cornwall, implying that it was fought for control of a strategic river crossing or bridge, whereas the Jersey poet Wace, writing in the 1150s, specifically refers to Cornwall’s River Camel as the location of the battle. So, at the site in question, we have a bridge called Slaughterbridge—seemingly suggesting a bloody skirmish was fought here—which crosses the River Camel, specifically named by Wace. However, as I researched the local history, there emerged a number of problems. The “slaughter” element in the name of the location comes from the Old English word slohtre, meaning “marsh,” so is not in itself evidence that any battle was fought here. Most of the medieval romancers place Arthur’s last battle in southern or central England, rather than Cornwall, and the earliest reference to the conflict in the Welsh Annals suggests it was fought in Wales. Although Wace specifically places it on the River Camel in Cornwall, he uses Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of the battle as his source, which he paraphrases almost exactly, implying that this Cornish location was solely down to Geoffrey. We have already questioned Geoffrey of Monmouth’s reliability when it comes to his Cornish Arthurian connections, such as placing Arthur’s birth at Tintagel Castle in order to please his patron’s brother, the Earl of Cornwall, who owned the place. Slaughterbridge is only twelve miles from Tintagel, and it too was owned by this same Earl of Cornwall. In fact, he owned much of the county, which explains why he was earl of it. So, according to Geoffrey, Arthur was born and ultimately fell on the estate of his patron’s wealthy brother. As such, I didn’t have much confidence in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account per se when it came to locating the site of Arthur’s last battle. But there was still the inscribed stone.

Fig. 3.2. Traditional locations for the lake into which Excalibur was cast.

When I first saw the inscription on King Arthur’s Stone—upon which its dating is primarily based—I was mystified as to why anyone had ever associated it with King Arthur. In Latin the weathered inscription reads: LATINI IC IACIT FILIUS MA [ . . .] RI, meaing “Here lies Latinus, son of [probably] Macarus.” As it is clearly the grave of someone called Latinus, where does the Arthur link come in? The oldest known reference to the stone appears in The Survey of Cornwall by the antiquarian Richard Carew published in 1602.18 Here, he tells us that “the folk thereabouts will show you a stone bearing Arthur’s name.” Presumably, he never saw it himself. Interestingly, another Cornish antiquarian, William Borlase, in his The Antiquities of Cornwall (abridged title) published in 1769,19 suggests that the locals mistakenly concluded that the last letters read MAG URI, which could, with some imagination, be considered a rendering of the Latin words Magni Arthur, meaning “Great Arthur.” A lot of imagination, I would think.

As far as I was concerned, all that was really left to suggest any association between Slaughterbridge and the early King Arthur legend was the cam element in the name of the River Camel, which also appears in Camlann, the apparent name for the location of Arthur’s last battle. As we shall see when examining the battle of Camlann itself, there are many such places in Britain bearing the affix cam. At this point it could just as well have been any of them. All considered, Slaughterbridge did not impress me as having a particularly strong case for being the site of the Battle of Camlann, and as such the nearby Dozmary Pool’s claim for being the Excalibur lake seemed equally unconvincing.

For the time being my research into the mystery of Arthur’s sword, or swords, had taken me no further in my quest to identify a historical King Arthur than my search for Camelot. So where was I to turn next? I decided to concentrate specifically on where Arthur was supposedly buried. No, not Glastonbury, but the Isle of Avalon. In the Geoffrey of Monmouth account, and in many of the later Arthurian romances, after his last battle the mortally wounded Arthur sailed off to the mystical Avalon. So where exactly was the enchanted Isle of Avalon originally thought to have been?