7

Last of the Romans

My search for the origins of the Arthurian legend had led me to the British kingdom of Powys. Its exact size in the late fifth and early sixth centuries is unknown, but it seems to have covered approximately what are now the West Midlands of England, together with central and north-central Wales. From the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s writings in the 1130s, Arthur is referred to as King Arthur and is usually depicted as king of all Britain, or in some cases as king of England. Much to the annoyance of the Welsh, “England” was often used to refer to both England and Wales from the time the English began invading their country in the twelfth century. It can be a bit confusing, even for us British, so I should probably pause and explain a bit more concerning the geopolitical setup of the British Isles. Strictly speaking, the term Britain refers to just England and Wales; it derives from Britannia, the Latin name for the province established by the Romans, which covered the parts of the British Isles they occupied. Wales became a separate country inhabited by the Britons after the Anglo-Saxons fully invaded the north, east, and south of Britain, establishing a unified kingdom of England by the mid-950s. Ultimately, Wales came under English rule after 1282 and today retains its semiautonomy as a British principality. “Great Britain,” which includes Scotland, did not exist as a single nation until 1707, while the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland” came into existence in 1801, after the British annexed Ireland. From the time Southern Ireland gained its independence in 1922 and formed the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom—or UK for short—now consists of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. (United Kingdom is actually the shortened form of “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.”) Oh, and by the way, the term Brits can refer to a citizen from any part of the UK, or just a part or parts of it, depending on your political point of view. Anyway, enough said! The point is that during the Middle Ages, when Arthur was perceived as having once been king, Britain referred to what had been Roman Britain: England and Wales. But as we have seen, around the year 500 when Arthur is said to have lived, Britain had fragmented into many separate kingdoms. So if he existed, what would Arthur really have been king of? Presumably, just one of these kingdoms—at least, initially! Had that been the kingdom of Powys?

Before I could begin to answer this question, I needed to examine in more detail the history of post-Roman Britain. As my research during this next phase consisted principally of reading, interviewing historians and archaeologists, and seeking out ancient manuscripts, I will keep things easy. I shall explain simply—hopefully—what is known concerning this period. When I say “known,” I should probably say “generally thought,” as much of post-Roman history is derived from fitting together diverse pieces of evidence, both historical and archaeological, and a certain amount of guesswork. Besides which, scholars often disagree on various matters concerning the era. The events throughout mainland Europe are pretty well understood, as they can be reconstructed from various Roman sources. Exactly what occurred in Britain, isolated from continental Europe, however, is much less certain. I’ll begin by explaining the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West.

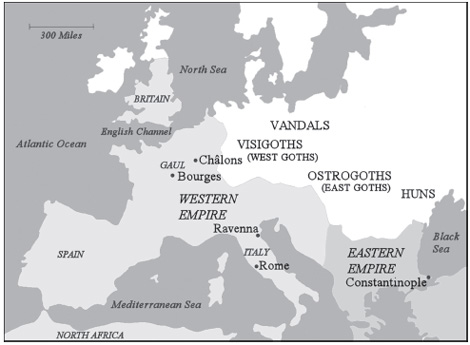

The city-state of Rome in Italy began its expansion to become a Roman domain during the fifth century BC, which continued to grow over the next few hundred years. Until 27 BC it had been a republic, governed by a senate, but in that year Augustus became the first Roman emperor. (It’s a common misconception that Julius Caesar, who died in 44 BC, had been an emperor. He wasn’t. He was a general whom the senate installed with what, for all intents and purposes, were absolute powers.) From that time the territories ruled by Rome became known as the Roman Empire, which reached its greatest extent in the second century AD and included territories all around the Mediterranean Sea, as well as Western Europe and parts of the Middle East. In 395 the Roman Empire split in two, when the Emperor Theodosius I divided it between his two sons upon his death. The Western Empire, still ruled from Rome, included much of Western Europe and a part of northwest Africa, while the Eastern Empire, ultimately ruled from Constantinople (modern Istanbul), came to be known as the Byzantine Empire. Remarkably, although it was much reduced in size after the Muslim conquests of the seventh century, the Byzantine Empire survived until Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. The Western Empire fared far worse. Significantly weakened by the split, it endured for less than a century. And endured is just the right word. From the start it was harassed by what the Romans called barbarians.

Barbarian was a term for any people the Romans perceived to be uncivilized—in this case those from the immediate east of the empire. The long northeastern frontier of the Western Empire was marked by the Rhine and Danube Rivers, which became increasingly indefensible, and the huge barbarian tribes from the east of this geographical boundary are collectively known as the Goths. (The word Gothic, as in a style of architecture during the Middle Ages, has no connection with these tribes. Neither does the term Goth for the contemporary subculture: the so-called Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century, named after a reintroduction of a Gothic style of architecture, also saw the popularity of the horror and “dark” genres in literature, from where the modern Goths get their name.) What began as incursions of plunder by the Goths soon turned into full-scale invasions, and it was all caused by the weather. In what is now the Ukraine, a particularly fertile area, lived a massive ethnic group called the Huns, descendants of the Mongols from central Asia. (These people had no connection to the Germans as they were called by the British during the First World War. The term Hun, in this context, derived from the spiked helmets worn by the German forces, similar to those depicted in contemporary illustrations of the ancient Huns.) Ironically, around the same time that the Roman Empire split in two, the Ukraine suffered years of low rainfall, leading to a series of disastrous crop failures. Impelled to migrate westward in search of food, the Huns surged toward the lands occupied by the less powerful Goths, who were in turn driven further west. Consequently, the vanquished Goths crossed the Danube and Rhine. But it didn’t stop there. With Rome on the defensive, its armies tied up fighting the Goths, other peoples broke through the frontiers of the Western Empire, and the North African provinces were lost. Eventually, the situation in Europe became so bad that the Western emperor, Honorius, moved his capital to the city of Ravenna in northeast Italy, and in AD 410 the Visigoths—the West Goths—seized Rome itself; the first time in eight centuries that the so-called Eternal City had fallen to foreign invasion. It was to bolster his forces to retake Rome that Honorius withdrew the troops from Britain.

Britain had been part of the empire for three and a half centuries, the fabric of its government reliant on Rome’s military support. This had provided stability for longer than anyone could remember. Now, suddenly, it was gone, and anarchy threatened the land. Every freeborn Briton had long been a Roman citizen, and few would have danced in jubilation on the beaches as the last boatload of soldiers disappeared over the horizon. You can imagine the turmoil: How many countries, even today, would remain intact and peaceful if all the police and armed forces suddenly disappeared? Precise records during this period of British history are few and far between, but an overall picture can be gleaned from Germanus, the bishop of Auxerre in Burgundy, who visited Britain in 429 as an envoy of the Catholic Church. According to his biographer, Constantius from Auvergne in modern-day France, writing around 480, “although there were serious troubles in the north, an organized Roman way of life persisted in the numerous British towns.”1 Even so, matters grew progressively worse, and over the following decade, central administration seems to have collapsed. In many parts of the country, the Britons reverted to tribal allegiances, and local warlords soon established themselves as regional monarchs, setting up a number of separate kingdoms. With continual territorial squabbles, the island slid inexorably into chaos and the Dark Ages.

Fig. 7.1. The Western and Eastern Roman Empires around AD 400.

In these troubled times few records were kept, and almost none have survived for us to examine today. The principal reason that so little is known of this period of British history is that the break from Rome removed Britain from the field of Mediterranean writers from whom we acquire much of our earlier information. It is therefore far from certain exactly what took place during the mid-fifth century. There is, therefore, considerable academic disagreement about post-Roman British history. For the rest of this chapter, we will often find ourselves in the realm of historical detective work. So, to be accurate, I will be describing the events as I personally came to interpret them from my research. Accordingly, rather than merely outline what seems to have occurred, it is important to say how I—or anyone else for that matter—reconstructed mid-fifth-century British history. Principally there are the historical sources, which are records, writings, and other documentation composed closest to the time being investigated, as opposed to primary sources, which are works contemporary with the events described. Unfortunately, no written works survive from mid-to-late fifth-century Britain, so the historical sources in this case were compiled sometime later. They do, though, appear to be based on earlier material committed to writing closer to or during the period in question. Other than Welsh tales and poems and fragments of other British war sagas—a number of which we have already examined—the key historical sources are limited to the works of the British monks Gildas and Nennius, the Saxon historian Bede, together with the Welsh Annals and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. As these Dark Age writings will play a crucial part in our examination of the case for Arthur’s historical existence, it is well worth providing a brief summary of them here.

- Gildas, who lived from around 500 to 570, was a British monk from a monastery in Glamorgan in South Wales. He wrote a Latin work around the year 545 that concerned the late fifth and early sixth centuries titled De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain). (The oldest complete copy of Gildas’s work is kept in Cambridge University Library in England, where it is cataloged as MS Dd. I.17.)2

- Nennius, as we have seen, was a monk from Radnor, in what had been the kingdom of Powys, now in west-central Wales. His dates of birth and death are unknown, but he is attributed with having written a Latin work titled the Historia Brittonum (The History of the Britons), compiled from both legendary and earlier historical sources around AD 830. (The Historia Brittonum is preserved in the British Library, London, in a manuscript cataloged as Harleian MS 3859.)3

- Bede, or the Venerable Bede as he is often called, was yet another author monk. Unlike Gildas and Nennius, he was Anglo-Saxon, coming from a monastery at Jarrow in northeast England. He lived from 673 to 735, and in 731 finished his Latin Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People). This work transformed the rough framework of existing material from ecclesiastical documents into an actual history book. (The earliest copy of the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum is in the National Library of Russia, in St. Petersburg, cataloged as lat. Q. v. I. 18.)4

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in Old English (the Anglo-Saxon language), was not composed by a sole author but was a collection of Anglo-Saxon monastic records brought together into a single manuscript between the years 871 and 899 under the supervision of the English king Alfred the Great. It lists events in Britain from 449 to Alfred’s time in chronological order, prefixed with the relevant year AD. Later copies of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle included further events up until the time of their writing. (The oldest copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is in London’s British Library, where it is cataloged as Cotton MS Tiberius B.i, f. 128.)5

- The Welsh Annals—or Annales Cambriae in the original Latin—is a register of events from 447 to 954 compiled from records kept at Saint David’s Cathedral in southwest Wales. It is not a detailed record by any means but rather a chronological list of dates coupled with brief notations of significant events that occurred in each year, accompanied by an appendix of genealogies of certain Dark Age royal families. Despite its name the document not only concerns events in Wales but throughout the British Isles. It is thought to have been committed to writing in its present form around 954, as this is the last year recorded. (The Welsh Annals is preserved in the same manuscripts as Nennius’s Historia Brittonum in Harleian MS 3859 in the British Library, London.)6

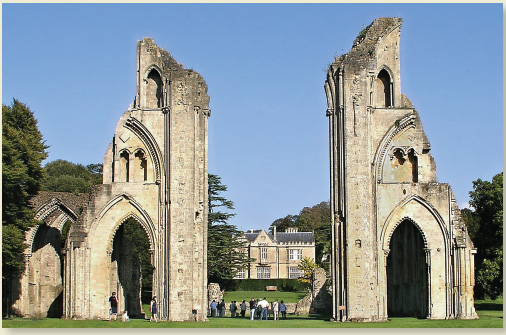

Plate 1. Glastonbury Abbey in southwest England, where twelfth-century monks claimed to have discovered King Arthur’s grave. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 2. The ancient ruins of Tintagel Castle in the English county of Cornwall, the traditional birthplace of King Arthur. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 3. The London Stone, said to have been the very stone from which the young Arthur pulled his sword of power. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 4. The isolated pool known as Coventina’s Well near Newcastle. Its once revered waters preserved vital secrets concerning the Lady of the Lake. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 5. Roman altar stone in Chesters Museum, near Newcastle, showing the water goddess Coventina, the original Lady of the Lake in British mythology. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

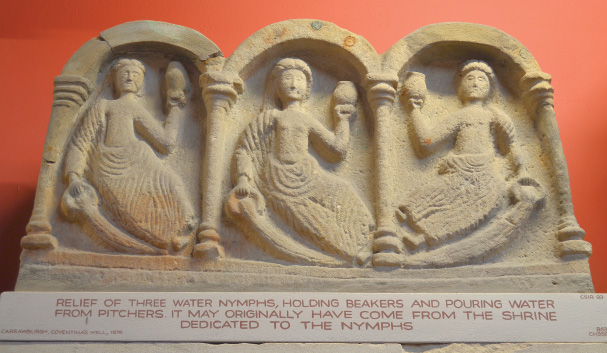

Plate 6. Inscribed relief from Chesters Museum, depicting the three Celtic water nymphs that may have inspired the Arthurian theme of the queens of Avalon. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 7. The remains of Hadrian’s Wall in the far north of England. This astonishing seventy-mile-long Roman structure was the northern border of Arthur’s Britain. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 8. Reconstructed Roman fort of The Lunt, near Coventry. This was the typical style of fortification used at the time Arthur is said to have lived, around AD 500. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 9. The Dark Age hill fort of Dinas Bran in central Wales, the resting place of the Grail in the Welsh Arthurian tradition. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 10. Valle Crucis Abbey, where the 1500-year-old story of King Arthur was preserved by monks to survive to this day. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 11. Whittington Castle in the English county of Shropshire, the Grail Castle depicted in the Arthurian romances of the Middle Ages. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 12. The Pillar of Eliseg near Llangollen in north-central Wales. Its Dark Age inscription revealed the bloodline of the historical King Arthur. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 13. Caer Ddegannwy towers above the coast of North Wales. On this impregnable rocky outcrop stood the fort of the historical Uther Pendragon, King Arthur’s father. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 14. The ruins of Viroconium in central England, the capital of early Dark Age Britain. The last functioning Roman city in the country, it may have been the inspiration for the legendary Camelot. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 15. View from the northern end of Lake Bala in central Wales. It was here, in a seventh-century monastic community, that the manuscript was composed to reveal the true identity of the historical King Arthur. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 16. Warwick Castle, one of the locations believed during medieval times to have been the magnificent citadel of Camelot. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 17. The winding River Camlad in Shropshire, as seen from Shiregrove Bridge. According to ancient Welsh tradition, this was the scene of Arthur’s last battle and his death. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 18. St. Illtyd’s Church at Llanhilleth in southern Wales, the burial site of the seventh-century poet Heledd, the British princess whose writings finally revealed the whereabouts of King Arthur’s lost tomb. Photo by Deborah Cartwright

Plate 19. The ancient earthwork known as The Berth in Shropshire, central England. Could this be the true final resting place of the historical King Arthur? Photo by Deborah Cartwright

From these historical sources we can reconstruct a general outline of mid-fifth-century Britain. Although specific details are often lacking, the basic picture appears to be that the north was suffering repeated incursions from the Picts of Scotland, while the West was being partially invaded by the Irish, but the greatest problems for the majority of the Britons were due to the struggle for regional supremacy between their own native chieftains. And it was into this beleaguered and fragmented country that the Anglo-Saxons came.

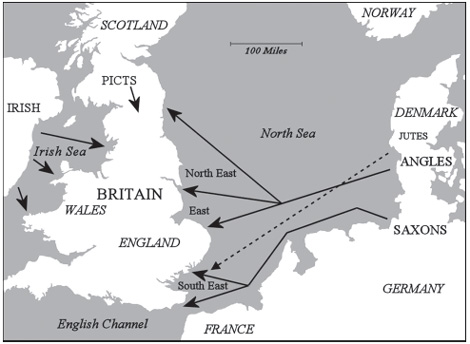

Because of the attack by the Huns on the Goths, there were mass migrations westward right across Europe—an unprecedented domino effect that ultimately destroyed the Western Empire. As a result of this general move westward, coastal dwellers from what is now North Germany began to cross the North Sea to settle in eastern Britain. These people were the Angles from what is now Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of modern Germany, and the Saxons to the immediate south of them, from what today would be the coastal north of the German state of Niedersachsen. Initially, these migrants settled just the coastal areas: the Angles in the east and northeast, and the Saxons in the southeast. There may have been local skirmishes with these newcomers, but rather than attempt to repel them, the British chieftains began to enlist their services as mercenaries to fight not only the Irish and Picts but also each other. Payment included land on which they could settle. (Ironically, this is exactly the kind of deal the Anglo-Saxons themselves later made—with disastrous consequences—with the Vikings who began to arrive in Britain in the late eighth century. But that’s another story.)

From what can be gathered from the historical sources, by the mid-fifth century one British chieftain organized a massive new influx of Angles and Saxons, additionally recruiting a people known as the Jutes from modern Denmark, settling entire tribes in parts of the east and southeast of what is now England. Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle give the year of this considerable Germanic immigration as 449, an event that early historians refer to as the Saxon Advent. (By the late Dark Ages, Saxons was the term applied to the Anglo-Saxons as a whole [see chapter 3]. Strange really, as Angles would seem to be more appropriate: ultimately, the united Anglo-Saxons referred to their country as Engla Land, “Land of the Angles,” from where the modern name England comes.) Archaeology supports the Dark Age sources regarding these migrations. For example, distinctive Angle-style pottery, unearthed during excavations in the northeast and east of England, reveals that the Angles began settling in what are now the counties of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk around the year 450. The same applies to the Saxon settlements in what is now the county of Essex, and the Jute settlements in the county of Kent, both in the southeast, where characteristic styles of their pottery have been found.7 During the 1990s, when I was first investigating the Arthurian tradition, the primary method of dating pottery was by ceramic sequencing. Ceramic sequences are chronological lists of ethnic earthenware styles: their fashion and techniques of manufacture change over the years, and the dating of a particular trend is made possible by datable items found alongside such objects unearthed at other sites. These days, a scientific method called rehydroxylation dating is also used, which can chemically estimate how long ago a ceramic artifact was fired (hardened in the kiln). It is accurate to within around thirty-five years either way, and by testing a number of samples of pottery, tiles, or bricks, a more precise date can be determined. Using such a technique, modern estimates agree with the dating of the Saxon Advent made by ceramic sequencing of the early Angle, Saxon, and Jute pottery finds.

As a consequence of the ambitious British chieftain employing huge numbers of foreign mercenaries, a large part of Britain came under his control. Gildas calls him simply tyrannus, Latin for “absolute ruler,” Bede uses the Latin name Vetigernus, while the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Nennius call him Vortigern. Yes, the same man who was allegedly helped by the young Merlin. We know from references such as the inscription on the Pillar of Eliseg (see chapter 6) that Vortigern was king of Powys, but with the help of his overseas allies, he seems to have become pretty much the king of all Britain for a while.

Fig. 7.2. The invasions of Britain in the mid-fifth century.

In many ways the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes were closely related, the area from which they originated being no larger than modern Wales. For most purposes, therefore, the term Anglo-Saxon can safely be applied to the entire culture, including the Jutes, who soon after their arrival lost their individual identity and merged with the Saxons in Kent.8 Indeed, the differences between them were tiny compared to the massive cultural gulf separating them from the Romanized British, many of whom were practicing Christians (albeit in a peculiarly Celtic way, see chapter 5). The pagan newcomers had their own religious customs, which the majority of the Britons would probably have found abhorrent. In Roman terms the Britons were civilized, the Anglo-Saxons were barbarians. With such a culture gap, problems were bound to arise. And they did.9

Trouble began around 455, when the Saxon colonies in the southeast revolted against their British overlords. There were doubtlessmany reasons for the rebellion, although Gildas informs us it arose over a question of payment for the mercenaries. He provides no details but does explain the severity of the insurgence, saying that cities were destroyed and their British inhabitants killed, enslaved, or forced to flee.10 Bede gives the same account, although he adds the names of the revolutionary leaders: two brothers called Hengist and Horsa. The Angles in the north also joined the rebellion. Bede writes that they swapped sides, formed an alliance with the Picts, and attacked the Britons.11 The extent of any overall organization of the Anglo-Saxon revolt is difficult to ascertain; what is certain is that the Britons were completely unprepared. The rebellion appears to have begun with the Saxon overthrow of a British contingent in the extreme southeast of England, which the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records for the year 455. It was a crucial turning point in the history of post-Roman Britain, as the successful revolt saw the establishment of the first Saxon kingdom in the country: the kingdom of Kent, after which the modern county is named. The Chronicle also tells us that Horsa died in the conflict, leaving his brother Hengist as king, and that Vortigern’s general, his son Cateyrn, also died in the conflict. The Saxon victory and the disarray of the British forces in the area immediately prompted a wider revolt throughout the southeast. The Britons were routed, and the Saxons set up other kingdoms: Essex (meaning “East Saxons”), to the north of the River Thames, and Middlesex (Middle Saxons), around London. Southeast England was firmly under Saxon control. To the immediate north the Angles quickly followed suit, seized even more land, established their own kingdoms—Suffolk (South Folk, from the Germanic fulka meaning “tribe”), and Norfolk (North Folk), both still lending their names to the modern counties of those districts—and pushed west into what is now the county of Cambridgeshire. In the northeast, with the help of their Pict allies, the Angles also seized a huge area, reaching as far south as the modern county of Lincolnshire.12 By 460 virtually the entire eastern part of Britain was in Anglo-Saxon hands. The fate of the British leader Vortigern is something of a mystery, but he seems to have been overthrown by his own people. Nennius, who is the only source to provide any details of Vortigern’s demise, tells us that he was so hated by the Britons for inviting in the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries that he was deposed, forced to flee, and “wandered from place to place until . . . he died without honor.”13

Gildas and Bede both relate how something of a stalemate then transpired for about a decade. It is reasonable to assume that this occurred sometime from around 465, as the Chronicle (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) lists no battles between 465 and 473. The two monks explain how this relatively peaceful period gave the Britons time to gather strength, also that they found a new and altogether different kind of leader: a smart, military strategist called Ambrosius. This is the same man who as a boy found favor with Vortigern and, going by what Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth reveal, seems to have been the man behind the legend of Merlin. If this is right, then the wise old Merlin had once been a mighty warrior.

The eight-year period between 465 and 473 seems to have allowed the native British to reorganize their forces. Of this time, Bede says that “the Britons began by degrees to take heart, and gather strength.” He attributes this to Ambrosius’s leadership: “They had at that time for their leader, Ambrosius Aurelius, a modest man, who alone among the Romans had survived the storm.”14 (The “storm” referred to the Anglo-Saxon rebellion.) Gildas also explains that Ambrosius was the man responsible for strengthening the Britons, and like Bede, he describes him as a Roman, “a gentleman who perhaps alone of the Romans had survived.”15 We shall examine the Merlin connection shortly, but for now we need to establish exactly who this Ambrosius Aurelius was.

Well, for a start, he seems to have been a Roman. However, that Gildas and Bede both refer to Ambrosius as the last of the Romans is somewhat confusing. By the time the Roman legions departed Britain in 410, every freeborn Briton was a Roman citizen. It had been centuries since only inhabitants of Rome or even Italy had been exclusively referred to as Romans; even many of the later Roman emperors had originated from places outside Italy, such as Spain, Africa, Syria, France, and even Britain, to name just a few. The Roman Empire had been an ethnic melting pot. Although by the 460s Britain had not been a part of the Roman Empire for half a century, the Western Empire still existed, and there were probably many people in Britain, especially among the more privileged classes, who continued to regard themselves as Romans, particularly the Christians. So why refer to Ambrosius as the last of the Romans? The answer seems to be that the authors regarded him as the last of the Roman elite. Gildas tells us that Ambrosius’s “parents had worn purple,” which was the color special to the Roman emperors.16 Something Bede also makes clear when saying that Ambrosius’s parents “were of the royal race.”17 So Gildas and Bede seem to be telling us that Ambrosius was a distinctly high-status Roman, descended from an emperor. Nennius provides us with additional information. When the young Ambrosius first meets Vortigern, the king questions him concerning his background, and the boy answers: “A Roman consul was my father.”18 Nennius offers no date for the episode, but by cross-referencing the events he describes with the other sources, it would seem to have been set somewhere around the year 450, and just four years earlier there had indeed been a Roman consul with the same family name: one Quintus Aurelius.

During the time of the Roman Republic, a consul was the highest elected political office (Julius Caesar had been one), but by the fifth century it was merely an honorary position by appointment of the emperor. There were usually two consuls who served for just one year, but though officially something akin to modern vice presidents, in reality they had no actual power. Very few consuls inherited imperial office upon the death of their emperor. Well, not for long—particularly as there were two of them, plus a number of far more powerful generals who wanted the job. Quintus Aurelius is recorded as having been consul in Rome in 446, and since there hadn’t been an Aurelius as consul for over half a century, Quintus was presumably Ambrosius’s father that Nennius had in mind.19 This would also fit with what Gildas and Bede say about his ancestor seemingly being an emperor, as the powerful Aurelius family was descended from Marcus Aurelius, who reigned from 161 to 180. He was an especially respected ruler, who was also a scholar, writer, and philosopher: the “good emperor” portrayed by actor Richard Harris at the start of Ridley Scott’s blockbusting movie Gladiator.

When I first proposed that Ambrosius was a member of this imperial line, some scholars questioned my theory, saying that there was no archaeological evidence that members of the Aurelius family had ever settled in Britain. But in 1992, later in the very same year that my book King Arthur: The True Story was published, they were proved wrong. On November 16 the biggest single collection of Roman gold and silver artifacts ever discovered in Britain was unearthed in a field near the village of Hoxne in the county of Suffolk in eastern England. Known as the Hoxne Hoard, it consisted of almost fifteen thousand coins, and around two hundred items of exotic tableware and jewelry, which are now on display in London’s British Museum. Archaeologists established that these valuable treasures had been buried in a box sometime during the early fifth century—probably by the fleeing Romans, in the hope of later recovery, when the Angles raided the area—and many of them were inscribed with the family name Aurelius.20

So there was a consul named Aurelius who was alive at just the right time to have been Ambrosius’s father, and members of the Aurelius family had been in Britain by the early 400s—shortly before Ambrosius appears on the scene. Who Ambrosius was and that he historically existed can be in little doubt. The first encounter between Ambrosius and Vortigern is, it seems, partially legend, but that the two met and that Ambrosius succeeded Vortigern as king, or at least some kind of overlord of the tribal chieftains of Britain, is also fairly certain. Not only does Nennius say that after Vortigern’s death Ambrosius became “the Great King among the kings of Britain,” but he also had the authority to appoint Vortigern’s surviving son Pascent as ruler of provinces in the west.21 Moreover, his leadership of the Britons is confirmed by both Gildas and Bede (see chapter 7).

Other than this we know very little about Ambrosius’s period of leadership. Gildas says simply that under him the British regained strength and “battled their cruel conquerors,”22 while Bede says virtually the same: “the Britons revived and offered battle to the victors.”23 (Note that Gildas, a Briton, refers to the Anglo-Saxons as “cruel conquerors,” whereas Bede, an Anglo-Saxon, calls them the “victors.”) Ambrosius’s forces seemed to have first advanced deep into the occupied southeast: as the Chronicle says they fought against Hengist, the Saxon king of Kent. However, the Britons were beaten back, as an entry in the Chronicle for the year 473 states that “Hengist and his son Oisc fought against the Britons and captured innumerable spoils, the enemy fleeing from them as they would from fire.” From the archaeological evidence, it seems that the Saxons pushed along the Thames Valley, as far west as the modern county of Berkshire. The Britons seem to have held the advance at this stage, demonstrated by the defensive earthworks they built, and there appears to have been an uneasy standoff in the southeast for the next decade.24 The war then shifted to another front, in both the north and east, against the Angles. (The campaigns against the Saxons and Angles might actually have been fought simultaneously, as we shall examine in the next chapter.) Here the fighting appears to have gone very much in favor of the Britons. Archaeology indicates a renewed British presence throughout the entire northern part of England and in the east, in the modern counties of Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire. The evidence, for example, are distinctive British ceramics and modes of burial recurring here from this time.25 So how exactly did Ambrosius manage so successfully against the Angles? Where, for instance, did he get such well-trained warriors to do the job, when just a few years earlier the Britons had been an incompetent rabble? His advance seems to have occurred in the mid-470s, and this coincides precisely with the end of the Western Roman Empire. Was there a connection? Let’s see how the Western Empire finally collapsed.

From now on, for convenience sake, I will refer to the Western Empire as the Roman Empire, as Rome had been its capital; it was also where the Roman Catholic Church was administrated and the pope was based. For all intents and purposes, it is the only one of the two empires that has any direct bearing on our investigation into King Arthur. Similarly, I shall refer to the Eastern Empire as the Byzantine Empire. This was actually the term applied to it many years later—named after its capital, Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul in Turkey), which was originally known as Byzantium—but it makes things much easier. (Incidentally, although the Byzantine Church was originally Catholic, it became what we now call the Eastern [or Greek] Orthodox Church.)

This, then, is how the “Roman Empire” finally ended. By the mid440s the Huns, who started the barbarian invasions by moving west from the Ukraine, had pushed through the Goth regions of Germany and crossed the Rhine into Roman Gaul (which included modern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, as well as parts of the Netherlands and Switzerland). Led by their infamous, fearsome leader Attila, the Huns devastated everything in their path. Ultimately, the Romans formed an alliance with the Visigoths and eventually defeated Attila at the Battle of Châlons in northeast France in 451. The man who led the joint army to victory was the Roman general Flavius Aetius, who became so popular that the emperor Valentinian III saw him as a threat to his power and murdered him in a fit of jealousy three years later. On March 16, 455, Valentinian was himself assassinated by two of Aetius’s officers to avenge their general’s murder. If one single act could be said to have been the death knell for the Roman Empire, it was this. Valentinian had been emperor for thirty years and was just about the only thing holding the empire together. Within days of his death, civil war erupted between various claimants to the imperial throne, leaving the empire totally exposed. Just eleven weeks later Rome itself fell to a Germanic tribe called the Vandals (originally from what is now Poland), who pillaged and sacked the city so brutally that their name has become synonymous with acts of mindless carnage. The emperor’s widow, the empress Licinia, and her daughters were raped and dragged away into slavery, and those who failed to flee the city were butchered in the streets. The Roman Catholic hierarchy, however, managed to survive. The resourceful pope, Leo I, managed to negotiate a safe passage for the Church leaders from the city, and the papal administration returned to Rome once the Vandals had moved on.26

Extraordinarily, even the sacking of the ancient capital failed to bring the warring Roman factions together. Throughout Europe various commanders assumed the title of emperor and fought each other to a standstill while the Goths, Vandals, and other Germanic tribes surged between the last of the Roman legions, plundering towns and cities as they went. The Roman civilization that had dominated Western Europe for centuries crumbled to ruins in a matter of months. Roman Italy held together for a few years, while a general named Ricimer tried to save the empire by installing a series of puppet emperors at the new capital of Ravenna on the Adriatic coast, 170 miles northeast of Rome. Ricimer, who was actually half Visigoth, effectively ruled what remained of the empire from 456 until his death from natural causes in 472. However, his authority did not extend much outside Italy; northwestern Europe beyond the Alps had collapsed into chaos, though scattered Roman forces continued a valiant but futile struggle. With the powerful Ricimer gone, a succession of weak emperors came and went over the next three years, until 475 when a general named Flavius Orestes assumed control of the empire—now pretty much just Italy—and appointed his twelve-year-old son Romulus as a puppet emperor. Orestes spent the next ten months fighting the Goth king Odovacer, who eventually defeated him at Piacenza in northern Italy. With the campaign lost Orestes was swiftly executed. A few weeks later, in the fall of 476, Ravenna was captured, Romulus was deposed, and Odovacer appointed himself king of Italy. Odovacer was in no way what the Romans called a barbarian, and he was nothing like the brutish Vandals. Being a Christian, he allowed the Roman Catholic Church to survive, and he spared the life of the boy emperor. Romulus, or Romulus Augustulus (Little Majesty) as he is sometimes known, was sent to live comfortably in a villa in southern Italy. All the same, the Roman Empire—the Western Empire that is—was complexly finished.27

It was at this very time that Ambrosius appears to have gone on the offensive against the Angles. The mounting of his victorious campaign into Angle-held territory, and the muscle to hold the gains and construct huge defenses (see here), implies that he commanded the kind of professional force that had previously not existed in post-Roman Britain—a properly trained and equipped army. Where did it come from? Because of the final collapse of the Roman Empire at this time, the troops may well have come from across the English Channel. During the last few years of the empire, although Gaul was in a state of chaos, various contingents of the Roman army scattered across the province attempted to hold their ground against the various Germanic tribes. By the end of 476, once there was no longer an empire to fight for, what happened to these forces? They may simply have dispersed or changed sides, but it seems likely that some, at least, made for the north coast of France and escaped to Britain.

In his De Origine Actibusque Getarum (The Origin and Deeds of the Goths), the Byzantine historian Jordanis, writing in Constantinople during the mid-sixth century, records that a sizable Roman force led by a general named Riotimus had a direct link with Britain in the 470s. He tells us that “Riotimus came with twelve thousand men to the land of the Bituriges.” This was an area around modern Bourges in central France. All did not go well, however, because “Euric, king of the Visigoths, attacked them with a vast army and after a prolonged struggle routed Riotimus.” Riotimus managed to retreat to the area occupied by an adjacent Germanic tribe allied to the Romans. This seems to have occurred in 472, as Jordanis refers to the death of the emperor Anthemius who died in that year. What happened to Riotimus after this is unrecorded, but Jordanis tells us that he had retreated with “all the men he could gather,” so he may still have had a sizable army. What’s interesting is that Jordanis refers to Riotimus as Rex Britannorum—King of the Britons.28 Clearly Riotimus could not have been the overall king of the Britons; all the British sources suggest that Ambrosius was the overlord or principal king of Britain at this time. But, as we have seen, Britain was divided into many regional kingdoms by the 470s, so Riotimus could have been king of one of these. Jordanis, however, was writing almost a century later and close to fifteen hundred miles away. He, or his source, can be forgiven for some minor confusion. In fact, although Jordanis suggests that Riotimus was a British king when he led the Roman forces, he may not actually have become such until later.

It’s only speculation, but it is possible that by the time the Roman Empire finally collapsed in 476, Riotimus and his surviving army made their way north and crossed the English Channel into the less hostile Britain—at least the parts of it controlled by Ambrosius. Jordanis also implies that the twelve thousand men originally under Riotimus’s command had themselves come from Britain to aid the struggle in Gaul. This is certainly most unlikely. Twelve thousand men would be more than two entire legions! A legion consisted of approximately five thousand soldiers. If there had still been two functioning Roman legions in Britain in the 470s, then the Anglo-Saxons would probably have been kicked out of the country altogether. It had only taken four legions for the Romans to conquer and occupy the whole of Britain in the first place. It is a far more reasonable assumption that these twelve thousand troops were what survived of the bulk of the Roman army in Gaul. A possible scenario is that the remnants of this army arrived in Britain to aid Ambrosius, and that Riotimus himself was established as a king in a particular region, perhaps the retaken areas of eastern England.

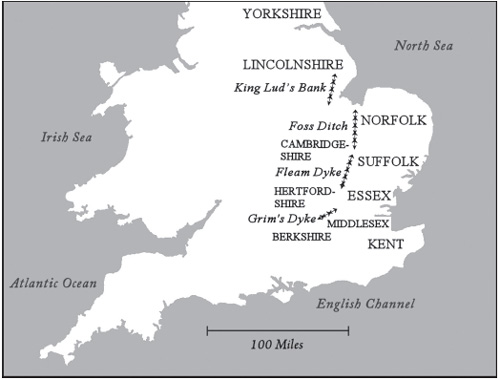

Whoever they were, archaeology certainly supports the fact that a functioning Roman army was present in Britain during the mid470s. Distinctive Roman military items have been found at British defenses from this period. Long stretches of earthen bank and ditch fortifications were constructed in the mid-to-late fifth century by the Britons in the eastern and southern parts of England. The Britons were known to have dug ditches, called linear defenses, along embankments facing Anglo-Saxon occupied regions, to impede attack from that side. (These embankments were often pre-Roman earthworks, modified at this time.) An interlinked series of such linear defenses include: Foss Ditch and Fleam Dyke, which respectively cut off much of Angle-occupied Norfolk and Suffolk from the British west; King Lud’s Bank, in the modern county of Lincolnshire, that prevented fresh incursions inland; and Grim’s Dyke to the northeast of London, which separated Saxon Middlesex from British-held Hertfordshire. In effect, these earthworks confined the Anglo-Saxons to the central east and southeast of England. Such defenses would, of course, be useless unless they were patrolled, and from the 470s those guarding them appear to have been Roman soldiers. Evidence of Roman armor being worn by these defenders are such items as military buckles, clasps, and hobnails from Roman boots, unearthed at archaeological excavations at these sites and dated (by ceramics found alongside them) to the mid-to-late fifth century.29 This was over half a century sincethe Roman army officially left Britain, and after the Roman Empire in the west had totally collapsed. Accordingly, a considerable Roman force of some kind must surely have come from continental Europe to join Ambrosius when the empire ceased to exist.

Fig. 7.3. British linear defenses of the 470s.

So, by around 480 the Anglo-Saxons were confined to the southeast and east, and the Britons were firmly in control of the rest of the country. And the man in overall control of the Britons was Ambrosius, the historical figure who appears to have been behind the Merlin legend. We are now very close to the period that Arthur appears on the scene, with Merlin—in the medieval romances, at least—as his trusty advisor. Before finally coming to examine the historical evidence for King Arthur’s existence, we need to know how Ambrosius, the “last of the Romans,” British high king, and mighty general, became the fabled wizard of legend.