5

Morgan and Her Sisters

Those familiar with the modern Arthurian story will recognize Morgan—or Morgana, as she is sometimes called—as being Arthur’s half-sister and chief rival, the evil sorceress who plots his demise. The original Morgan was quite different. Geoffrey of Monmouth fails to provide her with any background, and it is Chrétien de Troyes who first portrays her as Arthur’s sister. It was only in later romances that she became the “wicked witch,” a concept ultimately adapted by Thomas Malory. In the original stories she is a benign healer and prophetess and the ruler of Avalon, and many scholars propose that she was based on an ancient Celtic deity called Mórrígan (pronounced “Mor-rig-ahn”), meaning “great queen.” Nothing now survives in early Welsh texts concerning Mórrígan, but a great deal does exist in the mythology and old literature of Ireland. Wales, as we have seen, was occupied by the Romans, suffering turmoil for centuries after the end of their rule. Celtic Ireland, however, remained free from foreign occupation until 1171, when the Norman English started to invade. Consequently, far more unfettered Celtic mythology, once shared by the Irish and mainland Britons, remained in Ireland than in either England or Wales. In Irish mythology Mórrígan was a war goddess who guided the spirits of valiant warriors to the afterlife on a magical boat, similar to the Greek ferryman Charon transporting souls across the River Styx; she was also paradoxically associated with healing. Likewise, in the Arthurian stories, Morgan sails the mortally wounded Arthur to Avalon—in some tales to be healed, in others to be laid to rest.

Although Morgan, in the King Arthur saga, is not specifically a goddess, she is portrayed with supernatural powers. Rather than being a goddess, she seems to personify a deity. This is suggested by her name. Chrétien de Troyes, in 1170, is the first to refer to her as Morgan le Fey, meaning “Morgan the Fairy.” Today, the word fairy is associated with tiny, mythical creatures with gossamer wings, a theme popularized by the Victorians, but in its original medieval context, the word fairie referred to an enchanted person. Generally, in British and Irish mythology, fairies were completely human in size and appearance and were gods and goddesses in mortal guise.1 Sometimes they were men and women possessed by the spirits of deities. In ancient times, in cultures throughout the world, it was believed that divinities could temporarily occupy the bodies of gifted mortals, much like modern mediums are said to channel spirits. In Greece and Rome such people were known as oracles,2 while in Celtic society the role would be assumed by the head druids. As we saw in the last chapter, the Roman writer Pomponius Mela refers to the chief among his nine, island-dwelling Celtic priestesses as an oracle. We can assume, therefore, that this woman was one such druid. Putting all this together, it is reasonable to infer that Morgan in the original Arthurian legend, who heads Avalon’s sisterhood of nine, was considered an oracle of the goddess Mórrígan. Could it be, I wondered, that a historical King Arthur was laid to rest on an island sacred to Mórrígan or the dwelling place of her oracle? I needed to discover more about this ancient goddess.

I soon discovered that literature pertaining to Mórrígan was best preserved in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin. In its huge circular reading room, I was free to examine English translations of the definitive collection of early Irish manuscripts, books, and articles by various literary scholars and other related archaeological material in the library’s vast archives. Here my reading revealed that many of the mythological characters with whom I had become familiar in my Welsh studies also appeared in Irish mythology but with slightly different names. For example, the Arthurian hero Culhwch is attributed with similar deeds to the Irish hero Cuchulain, and the god-king Nudd Llaw Eraint, meaning “Nudd of the Silver Hand,” closely parallels his Irish equivalent Nuada Airgetlám, meaning “Nuada Silver Hand.” Such mythical figures were clearly one and the same. As the original Celtic language once shared by both Wales and Ireland had diverged into Welsh and Irish Gaelic, it was very possible that something similar had occurred with Mórrígan: a deity once known by a single name had come to be called Mórrígan in Ireland and Morgan in Wales. If so, Morgan le Fey was presumably named after the goddess she was thought to channel. But there was much more to link Mórrígan with Morgan le Fey than just their names.

I soon discovered that a number of Irish tales included the figure of Mórrígan, both as a goddess and in mortal guise. Although preserved in copies dating from medieval times, many are thought on linguistic grounds to be very much older, perhaps having been composed as early as the 700s. In some—such as Togail Bruidne Dá Derga (The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel),3Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland),4 and Cath Maige Tuired (The Battle of Magh Tuireadh)5—Mórrígan is accompanied by three sister goddesses called Badb (pronounced “Bave”), Macha (pronounced “Maxa”), and Anann (pronounced “Anarn”). Together with Mórrígan, they are said to be the children of Ernmas, the Irish mother goddess (referenced in Lebor Gabála Érenn and Cath Maige Tuired). In the medieval Arthurian romances, an unspecified number of women accompany Morgan in the barge from Avalon, but Thomas Malory expressly says that Arthur is taken to Avalon by “three queens.”6 Could these three queens have been based on Mórrígan’s three sisters? All three were Celtic water goddesses, and one of them—Macha—was specifically associated with a sacred lake island.

Remember how Geoffrey of Monmouth also calls Avalon the Isle of Apples? Well, in Middle Welsh, the language of Wales as it was spoken during Geoffrey’s time, the word for “apple” was abal, as it still is in Irish Gaelic. In Irish legend there is even a magical island called Emain Ablach (The Place of Apples) from which some scholars believe the name Avalon derived. It is the subject of a very early Irish story still preserved in Dublin’s Trinity College, just a block away from the National Library. In the Immram Brain (The Voyage of Bran), dating from around AD 700, the hero Bran (the same Bran we met in the last chapter) sails to Emain Ablach, said to be an island of immortality and healing where no one ever gets sick.7 It is also referred to as the Land of Women, as its guardians are a sisterhood of kindly sorceresses. Its name and description are so similar to Geoffrey’s Avalon that he probably, it has been argued, used it as the template for his Isle of Avalon. What I found particularly interesting is that in Irish mythology there are a number of real islands referred to as Emain Ablach. One of them, like the hillock at Llyn Cerrig Bach, remains as a hill at the heart of a dried-up lake. Today it is also called Emain Macha (The Place of Macha), named after one of Mórrígan’s three sisters who is said to have once dwelt there.

Nowadays, the site of Emain Macha is a low hill, some two miles west of the city of Armagh in Northern Ireland, surrounded by a bank and ditch around eight hundred feet in diameter. There is now a visitor center beside the hill called the Navan Centre (UK spelling), which includes a re-created Iron Age village, complete with reenactors, along with a café and museum. On the hill itself there are two mounds surrounded by circular ditches, one twenty feet and the other one hundred feet in diameter, that are the sites of what archaeologists believe were two Celtic temples built from wood. The entire complex has been dated to around 95 BC and seems to have been in use for over five hundred years until the spread of Christianity in the fifth and sixth centuries AD. Although the site is often referred to as Navan Fort, as it was later used as a fortified residence of local chieftains, archaeologists are certain that it was not originally built for defensive purposes. Rather it was some kind of religious or ceremonial compound.8 The bank surrounding the entire site was constructed on the outside of the ditch, the opposite of what would be expected if it was intended for fortification. As the Irish Celts had no form of writing until Christian times, there are no records of how the place was used or who lived there. However, as it is associated with the goddess Macha in mythology, it could well have been a sacred island run by a community of priestesses or female druids, like the contemporary Celtic islands mentioned by Strabo and Pomponius Mela (see chapter 4).

Other examples of sacred Celtic lake islands with two druid temples, such as those on Emain Macha, have been found in both Ireland and Scotland, and they too were associated with important water goddesses; for example, the islands in Lough Derg and Loch Maree discussed in the last chapter. Early monks from the monastery of Saint Patrick’s Purgatory on Station Island in Ireland’s Lough Derg record that there had been two pagan shrines on the island that they reconsecrated as places of Christian worship in the sixth century and over which they built churches. One of these had been a cave believed to have been the dwelling place of a lake goddess called Cliodna, and the other had been a stone and thatch building where the sick were tended.9 On Scotland’s Isle of Maree, archaeologists have excavated two similar sites.10 One was a circle of standing stones dated to around 100 BC (see chapter 4), and the other was a pool shrine, recorded by monks in AD 672 as being sacred to a water goddess called Slioch. At this pool, fed by a natural spring, archaeologists have uncovered votive offerings, such as jewelry and coins, dating from as late as the sixth century AD. At both sites monks erected churches, and they reconsecrated the pool as a holy well. Holy wells survive in great number throughout Western Europe, where pagan shrines, once dedicated to female water deities, were sanctified as sacred to Christian saints, such as Saint Mary, Saint Catherine, and Saint Brigit.11 (Another example of the Roman Catholic policy of “Christian Reinterpretation” we saw in the chapter 3.) Local tradition still calls the island on Loch Maree the Isle of Chapels, in reference to the two churches that once stood there. Today the ruins of only one of them, the one with the holy well, still survives to be seen. Although evidence of the early occupation of the lake island at Emain Macha in Ireland is less well preserved, as it was reconstructed and fortified in the seventh century, comparisons with these other sites led archaeologists to speculate that the original earthwork was a similar twin-temple complex sacred to a water goddess, in this case Macha. (Interestingly, Irish mythology also refers to the site as “The Twins of Macha,” possibly in reference to these two temples.) So, just as the Celtic deity Mórrígan appears to have been incorporated into the Arthurian saga as Morgan le Fey, the oracle, healer, and ruler of Avalon, it seemed to me to be a reasonable assumption that Macha, one of Mórrígan’s three sister goddesses, could have inspired the character of one of the Arthurian three queens who also dwelt on the enchanted isle. But there was more. Another of Mórrígan’s sisters appeared to have been the inspiration for none other than the Lady of the Lake.

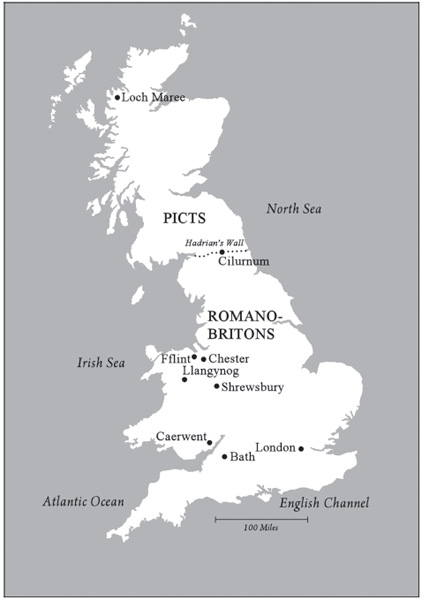

Fig. 5.1. Map of Ireland, showing locations discussed in this chapter.

We have already seen how Thomas Malory specifically states that one of the three queens was the Lady of the Lake.12 Writing in the late fifteenth century, he calls her Nynyue, usually rendered as Nimue in modern English translations. The authors of the much earlier Vulgate stories, composed over two centuries before, called her Ninianne, although in the first of them to include her (the Vulgate Merlin, ca. 1230), she is called Vivianne.13 The “Viv” element in the name probably derives from the Latin viva, meaning “living,” while the “anne” element is of Old French origin, a language spoken throughout England and Wales by the Norman rulers of Britain at the time, which in turn comes from the Breton Gaelic Ana, a Celtic water goddess recorded in Roman Gaul. (Breton Gaelic was the Celtic dialect of Brittany in northern France.) In the Irish legends one of the three goddess sisters is called the very similar Anann, so the original name of the Lady of the Lake could well mean “The Living Anann.” In other words, she is the goddess Anann incarnate. Indeed, the Anann of Irish mythology is associated both with lakes and miraculous cures; she is said to appear on sacred ponds to heal wounded warriors in the guise of a swan. In County Kerry in southwest Ireland, there are two adjoining hills called Dá Chích Anann, “The Breasts of Anann,” once considered sacred to the goddess. Below the hills, beside an ancient stone-walled enclosure called Cahercrovdarrig , “Fort of the Red Claw,” there is a pool fed by a natural spring, once sanctified to Anann but now a Catholic holy well.14 Here archaeological excavations have uncovered votive offerings, such as weapons, domestic items, and various other trinkets, dating from before the pool was consecrated as a Christian shrine. Remarkably, until as late as the 1940s, local people would still gather at the site to perform a May Day festival, including a ceremonial procession involving the throwing of coins and other personal belongings into the well, which was considered to promote good health.15 All said, Anann bore a striking resemblance to the Lady of the Lake, the water nymph to whom Arthur’s sword was thrown when he was mortally wounded. She was a goddess associated with sacred lakes and pools and with the practice of votive offerings, particularly with regard to the healing of warriors. Furthermore, she was one of Mórrígan’s three sisters, and the Lady of the Lake was one of the three queens who took Arthur to Avalon.

There could be little doubt that Morgan and the three queens in the Arthurian tale of Avalon were original Celtic concepts. This meant, at the very least, that the story elaborated by the medieval Arthurian romancers had to have been based on much earlier Dark Age legends. Moreover, in pre-Christian times there had been lake islands occupied exclusively by pagan priestesses and healing oracles, but those we know of were all in Celtic Ireland and France. What about Celtic Britain? Might a historical King Arthur—a British warrior—have been taken to a priestess, regarded as a healing oracle, living on a sacred lake island inhabited by nine holy women? Or, at least, was such a tradition included in the Arthurian legend in its original form? We have seen how there probably were such sacred lake islands in England and Wales, such as those at Lynn Cerrig Bach and Llangorse Lake, but because there are far fewer records concerning pre-Roman Britain as there are of France, and Christianity came to Britain well before Ireland, there is much less information from which to base an opinion. Nevertheless, we do have indirect evidence to suggest that such island healing sanctuaries run by women not only existed in Britain but still survived at the time Arthur is said to have lived.

As we have seen, in Britain the Romans adopted Celtic pagan customs, although they usually changed the names of the native deities to match their own. So, Celtic tradition did survive the Roman occupation in a Romanized form, specifically as Romano-British religion. When the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as the state creed in the fourth century, a hybrid faith emerged in Britain, where Celtic pagan practices, sacred sites, and deities were incorporated into Christian worship (see chapter 4). Even though the Romans had tried their best to eradicate them, we know from early Welsh writings that even the druids managed to survive in isolated locations. This pagan-influenced Christianity endured throughout Britain until well into the sixth century. Moreover, so did the druids. Astonishingly, they reemerged after the Roman withdrawal in AD 410 but known under a new name—the bards. To research the bards I needed to return to the National Library of Wales. (I wish we’d had the Internet back then.)

Although the origin of the word bard is obscure, bards are best known as Dark Age Celtic poets; many of their poems still survive, relating the exploits of Welsh warriors of the time. The works and deeds of historical bards of the sixth and seventh centuries, such as Aneirin and Taliesin, are preserved in medieval copies of early Welsh literature, such as Llyfr Coch Hergest (The Red Book of Hergest), preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch (The White Book of Rhydderch), Llyfr Aneirin (The Book of Aneirin), and Llyfr Taliesin (The Book of Taliesin), preserved in the National Library of Wales. (Incidentally, Shakespeare is known as The Bard as he is regarded as the greatest of poets.) But the original bards were not only poets, they were also considered to possess prophetic powers and were renowned as healers, even wizards. We will be examining bards in more detail later, but for now all we need to bear in mind is that what’s recorded concerning them is almost identical to what’s known of the druids. Bards featured prominently in the post-Roman Celtic Church in Britain, and some of them were even made saints, such as Saint Herve, a Welsh bard born in 521 who founded an abbey and was venerated as a healer and miracle worker. There were female bards, too, such as Heledd, a seventh-century princess from what is now central England. We have already seen how certain lake islands were still being occupied, or reoccupied, as sacred sites during the period Arthur is said to have lived around AD 500, and these places were most likely occupied by bards. Historical records are scarce from this era, and so it is hard to determine what such sites were used for, but healing sanctuaries seems a good bet. Some records do survive from more accessible locations, such as those that later became the sites of ecclesiastical buildings: for instance, Saint Melangell’s Church near the Welsh village of Llangynog in the county of Powys. The sixth-century Saint Melangell was a female Christian bard who founded a healing sanctuary run exclusively by women, which stood where the church now stands.16 (Intriguingly, Melangell is the patron saint of hares, and the hare is her symbol found carved on the church. The hare was also the symbol of the Celtic moon goddess, further implying that this Christian saint was also regarded as a pagan priestess.)

Returning to my question: Could the wounded Arthur have been taken to a healing sanctuary run by such women on a holy island? Was this the origin of the Arthurian Avalon theme? In pre-Roman Britain there had indeed been lake-island sanctuaries run by Celtic priestesses, and in some areas—the pagan, country-dwellers’ districts—they endured the Roman occupation. After the Romans left they again assumed importance as neo-Christian bardic shrines. So a wounded Celtic warrior of Arthur’s time could well have been taken to such a site. Equally, the sword of a historical Arthur might have been cast into the lake surrounding such an island as a tribute to a water goddess in the guise of a Christian saint. There is no doubt that the custom of votive offerings did continue with the early Christians. Many examples exist of post-Roman treasures dating from the fifth and sixth centuries being unearthed from now dry springs, such as near the towns of Caerwent and Flint in Wales, and Chester and Shrewsbury in England. They have included everything from dishes, bowls, brooches, rings, and other jewelry, some made from gold or silver. These were expensive and precious items and were obviously not discarded or thrown here as rubbish; rather, devotees deliberately cast these items into the water as offerings. How do we know these devotees were Christians? Easy! Many such artifacts were inscribed with the Chi-Rho symbol.17 The Chi-Rho (pronounced “kai-roe”) was a monogram formed by the Greek letters chi and rho—X and P. They are the first two letters of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ meaning “Christ.” Before the cross was adopted in the later Dark Ages, this was the most widely employed symbol of Christianity. In fact, the practice of votive offerings still continues among Christians today who throw coins into holy wells as donations to particular saints. Among the general populace, the convention of casting money into wishing wells derives from this custom.

As I wandered the aisles of the National Library of Wales, I considered what I’d learned, so as to decide my next move. It seemed a reasonable possibility that a real lake had existed into which a historical Arthur’s sword could have been cast, and in it there was an island upon which stood a sacred healing sanctuary where the fabled king might still lie buried. What I was looking for was either a surviving lake island or, as many ancient lakes had been drained for farmland, a hillock that had once been a lake island somewhere in what is now either England or Wales. But where was I to look? There might have been dozens of such sites scattered across England and Wales, most of them unrecorded and long forgotten. I could only assume that, as the Arthurian romancers asserted Morgan to be the person to whom Arthur was taken, the place I was searching for was associated with the goddess upon whom she was based—or at least someone considered to have represented the deity (as oracle). This deity, as I have argued, seems to have been Mórrígan. Mórrígan was the Irish name for the goddess—as were the names of her sisters: Badb, Macha, and Anann—but they might easily have had similar names in Celtic Britain, such as the examples cited above. Geoffrey of Monmouth, for instance, implied he took the name Morgan from an earlier British text (see chapter 4). Perhaps if I located a shrine or temple where similar names were inscribed, it would be a place to start. As the National Library of Wales had archaeological archives including information on post-Roman sites in both England and Wales of the period I was investigating, I decided to see if anything in them struck a familiar chord. Back in the early 1990s, little in these archives was computerized—there was no database as such. (Such primitive times!) However, during a long-haul search though typed and handwritten index cards, I found nothing helpful in surviving Dark Age accounts or recorded on inscriptions found by archaeologists in mainland Britain. Perhaps the British equivalents of Mórrígan and her sisters had been known by completely different names. I had already seen that at Ireland’s Lough Derg a water goddess was called Cliodna, and on Scotland’s Loch Maree she was known as Slioch. Even one of the medieval Arthurian romancers, Layamon, refers to Morgan under a separate name: Argante. All the same, I could find no further Dark Age references to any of them either. Maybe Mórrígan and her sisters had inherited Roman monikers.

I already knew that, over the years, archaeologists had discovered various springs, pools, and lakes venerated by the Romano-Britons. When the Romans came they often adopted local gods and goddesses but called them by the names of equivalent Roman deities, and Celtic water goddesses, generally associated with healing, were usually regarded as Minerva, a Roman goddess of water and good health.18 There were many examples of temples to Minerva being built over Celtic water goddess shrines, such as in the city of Bath in southwest England, where the geothermal waters were considered sacred, and at Minerva’s Shrine in Chester, close to the Welsh border in west-central England. At Bath the Roman bathhouse still exists (after which the town gets its name), where people would bathe in the hope of being cured by the goddess, and in Chester the ruins of the original Roman temple to Minerva still survive. But although water goddesses were widely venerated throughout ancient Britain, and continued to be so by the Roman and post-Roman Britons, had there been a specific quartet of female deities comparable to Mórrígan, Badb, Macha, and Anann? I could find nothing pertaining to such at the National Library of Wales, but I did find reference to one of the most thoroughly excavated sites of a water goddess shrine in Roman Britain: at the Roman fort of Cilurnum on Hadrian’s Wall in the far north of England. It seemed a good place to continue my search.

When the Romans invaded Britain in the first century AD, England fell fairly easily, but the wilder regions of Wales caused problems, which the Romans eventually overcame. Mountainous Scotland, however, proved much more difficult, and the Romans finally gave up trying to conquer it. The Celtic peoples of Scotland, whom the Romans called Picts (coming from the Latin picti meaning “painted,” referring to their heavily tattooed bodies), continued to raid Roman settlements in northern England. In response, between the years 122 and 128, the Roman emperor Hadrian ordered a massive defensive structure to be built separating occupied Britain from Scotland. Known as Hadrian’s Wall (see plate 7), it was ten feet wide and twenty feet high and stretched some seventy miles from coast to coast. (Much of it still survives, although in ruins, but some stretches have been painstakingly restored.) For the next three centuries, Hadrian’s Wall marked the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire. Along the rampart there were numerous defensive towers, and a series of forts, each occupied by between five hundred and a thousand soldiers. One of these, Fort Cilurnum, was situated halfway along the wall, near the present-day village of Walwick in the county of Northumberland, and consisted of barracks, bathhouses, and administrative structures. Just outside the fort a town soon grew up, housing those who made their living catering to the needs of the Roman army. There were never any official legions stationed on Hadrian’s Wall, which was defended by auxiliary troops, many of them recruited from among the native Britons. By the mid-second century, many Britons had become accustomed to Roman rule—Britain had benefited from the new infrastructure—and in the north of England, in particular, most saw the Romans as a vital defense from the hostile tribes of Scotland. So the “Roman” soldiers that manned forts like Cilurnum included many native Celts. It may come as something of a surprise to know that by the second century every freeborn Briton held Roman citizenship. Those who had fought the Romans had been enslaved, but those who capitulated—a significant majority—continued to live as free men and women. And it was the descendants of such people who lived in the town at Cilurnum. Accordingly, they still worshipped their own gods. So long as they obeyed Roman law and swore allegiance to the Roman Emperor, they could follow any religion they liked. It was around three miles from the town of Cilurnum that the Romano-Britons built a temple over an already existing shrine. It had originally been a pool, fed by a natural spring, considered sacred to a water goddess, into which votive offerings were cast. Originally, the shrine probably only consisted of a circle of standing stones surrounding the water, but the new structure was a grand Roman temple around forty-foot square. Archaeologists reckon that the pool itself had been turned into a square, brick-lined basin, some ten feet by ten, surrounded by a low stone wall. It was enclosed in a roofed, pillared building, at one end of which stood an altar and bas-reliefs depicting the goddess, complete with inscriptions dedicated to her.19

Fig. 5.2. Roman Britain and Pictish Scotland separated by Hadrian’s Wall.

The foundations of the Roman fort still survive, and a museum stands at the site, displaying many of the ancient artifacts uncovered here. There had been hundreds of temples in Britain in Roman times, but very few have survived—even as ruins—and only a handful are shrines to a water goddess. These, such as those in Chester and Bath, are all dedicated to the Roman goddess Minerva, and their inscriptions reflect entirely Roman mythology. The temple at Cilurnum, however, is unique. It is the only excavated shrine from the Roman period known to have been dedicated exclusively to a Celtic water deity. There are other examples of Celtic sites sacred to water goddesses, as demonstrated by the votive offerings found in lakes, pools, and springs, from the pre-Roman, Roman, and post-Roman eras, but none of these incorporated elaborate brick-built constructions, surviving inscriptions, or statues and other ornamentation. Any shrines accompanying them were built chiefly from wood, which would have rotted away centuries ago. The Cilurnum shrine is different: it was created using long-lasting Roman architecture. As the only surviving example of such a water goddess sanctuary used by the native Britons, I hoped it would provide me with vital clues in my search for Avalon.

Cilurnum, today called Chesters (not to be confused with Chester), was first excavated as long ago as 1876 by the antiquarian John Clayton from the nearby city of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and the museum at the site—now called Chesters Museum—was opened in 1903. Here I learned that the site of the shrine itself is now just a spring marked by a single standing stone in open countryside, the brickwork and artifacts discovered there having been moved into the museum. So, strictly speaking, although the shrine survives, it no longer exists in situ; rather, it is in pieces in a public gallery. Nevertheless, these artifacts revealed much. Many of the stone blocks that once formed the walls of the temple are inscribed with the goddess’s name—Coventina (see plate 5). Various officers stationed at Cilurnum and other forts along Hadrian’s Wall made these Latin inscriptions. For example, one read:

To Coventina, [I] Aelius Tertius, prefect of the First Cohort of Batavi, willingly and deservedly fulfills a vow

A prefect was a military officer, roughly equivalent to a lieutenant colonel in the United States army, and a cohort was a Roman army unit consisting of around five hundred men, what we might now call a battalion. Aelius Tertius was, it seems, the fort commander. Some of the dedications were made on behalf of the entire cohort:

To the goddess Coventina, the First Cohort of Cugerni . . . willingly placed this offering

The vow and offering referred to were clearly votive offerings, as literally thousands of such items were uncovered at the site of the pool: beads, glass and pottery utensils, pieces of jewelry, and an astonishing fourteen thousand coins. Because coins can be dated by the name of the emperor depicted on them, we know that the shrine was being used right through until the end of Roman rule. After the Romans left, the fort and town were abandoned as the Picts of Scotland surged south. Nonmilitary personnel also commissioned inscriptions:

For the goddess Coventina, Crotus and his freedmen, fulfill [their vow] for the health of the soldiers

Freedmen—libertas in Latin—were originally former slaves who had been granted their freedom, but the term was ultimately applied to a general social class, often traders descended from freed slaves. In this case they were probably the native Britons from the Roman town. From inscriptions such as this, we can determine that the offerings were being made for continuing good health, for healing, or in the hope of cures. Coventina was clearly a goddess of water and healing, very similar to the Irish Mórrígan. It was when I saw the altar stones from the temple that I had to conclude that she was almost identical. The first was about two and a half feet high, one and a half feet wide, and six inches thick. It was a beige-colored, rectangular stone with a pointed top, like the gable end of a house, the upper half carved with a shallow recess in which was a depiction of the goddess in bas-relief, showing her reclining on a water lily and holding a leafed branch, the lower half bearing a Latin inscription naming her as Coventina. But it was the second of the altar stones that was particularly fascinating. Cut from the same type of stone, around three feet wide, one and a half feet high, and some six inches thick, it was also a bas-relief carving representing three rounded arches, separated by columns. Within each arch was depicted a bare-breasted woman reclining on a couch. Each of these three women held an urn, suggesting that they were also water deities or nymphs. There was no inscription on the stone, but staff at the museum told me that they were thought to represent Coventina in triplicate: a triple goddess was worshipped widely throughout the Celtic world, they said. As far as I was concerned, they were dead wrong about that. I had already come across this triple-goddess notion in my research and had discounted it early on.

Goddesses depicted in threes have indeed been found in early Celtic art, but the idea that they were a single deity in three guises is a modern concept. Many of today’s Wiccans, pagans, and New Agers regard their chief goddess as having three forms: Maiden, Mother, and Crone, symbolizing the separate stages of the female life cycle. This, however, is a recent idea, popularized by the English writer and novelist Robert Graves in his book The White Goddess published in 1948.20 Contemporary historians regard Graves’s study of mythology as unreliable, as it was influenced heavily by the controversial early twentieth-century works on witchcraft by authors such as the English anthropologist Margret Murray21 and the occultist Aleister Crowley.22 In fact, since the 1940s, some authors have gone so far as to suggest that the Irish Mórrígan was actually a triple goddess, which they term The Mórrígan. It is maintained that “The Mórrígan” was actually one and the same as her sisters, Badb, Macha, and Anann, who were in reality her three aspects, Maiden, Mother, and Crone. Other Arthurian researchers, having equated Morgan with Mórrígan, maintain that the three queens in the Avalon story were the “three Morgans.” As far as I could tell, there was no historical base for any of this. Although in Irish mythology their exploits occasionally overlap, probably due to confusion in later translations, Mórrígan, Badb, Macha, and Anann were completely separate figures with their own independent and distinctive stories. As for the three queens being aspects of Mórrígan in the medieval King Arthur stories, it just doesn’t fit. They are all portrayed as young, not at different stages of life. One of them, the Lady of the Lake, even has her own literary résumé, which is totally different from that of Morgan le Fey.

From my perspective there had never been a triple goddess in the ancient Celtic world. But even if there had, there was no evidence whatsoever that the three goddesses depicted on the altar stone at the Chesters Museum were it (see plate 6). Based on discoveries made at the shrines to Minerva in Bath and Chester, as well as many intact examples of temples to goddesses worshipped by the Romans in Rome and elsewhere, archaeologists believe that the two altar stones were fixed to the wall above and behind the altar itself.23 Because of its pointed top—or triangular tympanum, in architectural terms—the stone with the single goddess, identified by its inscription as Coventina, was set on the wall immediately above the stone depicting the three goddesses under their rounded arches. In effect, the two stones together represented a building in which Coventina sat in a gable window, while the other three figures sat in the colonnade below. In other words the scene depicted Coventina and three attendant goddesses, just like Mórrígan and her three sisters.

So was Coventina a name the Britons used for Mórrígan? Was this a depiction of the woman upon whom Morgan, the enchantress who tended to Arthur on Avalon, was based? And were the three goddesses the three Arthurian queens, one of them the Lady of the Lake herself? The site where the temple stood, now called Coventina’s Well (although it was never actually a well), could not have been the lake in the Arthurian story; it was just a pool, around ten feet wide (see plate 4). Besides which, the area had been abandoned to the Picts when the Roman army left, almost a century before Arthur’s time. But Coventina and her attendant goddesses did suggest that something very similar to the cult of Mórrígan did exist in Britain. It was certainly not confined to the north of the country, as images of three attendant goddesses to Minerva have been found elsewhere, such as in the Roman bathhouse in the city of Bath.24 Unfortunately, Coventina has not been found on inscriptions other than those from Cilurnum, so it may have been just a local name for the deity. One of the staff I spoke to at the museum thought that Coventina might have been a Roman rendering of a Celtic water goddess called Covianna, a remarkably similar name to Vivanna, from which the name Vivianne, the Lady of the Lake, might have been derived. However, I could find no reference to an inscription bearing this name either. Nevertheless, that Coventina has not been found on any other contemporary inscriptions did not necessarily mean that the name was not used elsewhere, merely that no such inscriptions had been unearthed. There are only a handful of inscriptions bearing the name Minerva found in Britain, but we know from Roman records that she had dozens of temples and shrines in the country. It’s simply that so few such artifacts have survived the wet British climate.

Whether or not the name Coventina was applied to this water deity elsewhere in Britain was basically irrelevant. Her shrine proved, to my satisfaction at least, that goddesses very similar to Mórrígan and her sisters had been venerated in Britain, confirming my conjecture that the Arthurian Avalon theme was based on early Celtic mythology. There was a Celtic tradition involving nine priestesses skilled in the art of healing who lived in isolation on lake islands; their leader, an oracle, apparently “channeled” a goddess. Nine sisters were said to live on the Isle of Avalon, and they had healing powers, while Morgan, their leader, seemed to represent the goddess Mórrígan. Besides Morgan, the most important of the nine sisters in the Arthurian saga were the three queens; from Ireland there was Mórrígan and her three sisters, and in Britain there was Coventina and her three attendants. Avalon appeared to have been an island in the lake into which Excalibur was thrown, and personal weapons such as swords were cast into sacred lakes as votive offerings. Such offerings were to a water goddess, such as Anann, upon whom the Lady of the Lake appeared to be based. I was convinced that the Arthurian story of Avalon, Morgan, and the Lady of the Lake had indeed derived from some early Celtic source, predating Geoffrey of Monmouth and the medieval romances by centuries. But was any of it actually real? Could a historical, mortally wounded warrior, upon whom the legend of King Arthur was based, have actually been taken to a lake, where his sword was cast as an offering in the hope of healing, and then transported to an island in the lake to be cared for by an oracle (or bard) and her female entourage? Such a scenario was certainly possible around the year 500: many of the old Celtic practices had been incorporated into the kind of quasi-Christianity prevalent in Britain at the time.

It was all good stuff. My problem was—as I stood in Chesters Museum, gazing at the depictions of Coventina and the three nymphs—I had no idea where to go next in my search for a historical Avalon. That was until I examined another exhibit I’d only previously glanced at: the top half of a human skull excavated from Coventina’s Well. It was, I was told, the only human remain found there. It seemed unlikely to have been a sacrifice; if the place had been used for such rites, there would have been other human bones unearthed. It was certainly not someone who had fallen into the pool by accident, or the rest of the skeleton would have been discovered. It was probably, one of the museum staff explained, related to the Celtic practice of head worship. She was, of course, referring to the talking heads I discussed in chapter 4. It was most likely such a sacred head specifically associated with the Coventina shrine, with which the temple oracle would once have communed; perhaps the head of some ancient priestess or queen imagined to have personified the goddess. The skull dated from the period the site was abandoned, so it was thought to have been placed in the pool when the Britons fled south. Most probably it had previously been kept, possibly as a mummified head, upon the altar, but once the Picts invaded, it was considered appropriate to leave it in the goddess’s hallowed waters.

It was while I was listening to the explanation of the skull that I was struck by something I had virtually overlooked. The most famous of such talking heads was the head of Bran, and it had close links with the story of the Grail. Bran was said to have been a onetime ruler of Annwn, upon which, in part, Avalon was based. Bran, as the magic cauldron guardian, seems to have been the character upon which the Arthurian romancer Robert de Boron based his Grail guardian Bron. Robert tells us that the Grail had been hidden in Avalon, a theme also employed by later medieval authors. The Welsh hero Peredur was the blueprint for the Arthurian Sir Perceval as portrayed by Chrétien de Troyes, and Perceval is the knight who finds the Grail. In Chrétien’s account Perceval locates the Grail in the so-called Grail Castle, whereas in the earlier Welsh tale Peredur, in precisely the same circumstances, Peredur discovers what had to have been Bran’s head in a castle in Wales (see chapter 4). I now had a new line of reasoning that might pinpoint the area where the lake island I was seeking could be found. If the Grail and the head of Bran were supposedly in the same place, and that place was Avalon, my next move would be to find where the Peredur tale actually located it. I almost laughed out loud. I was now not only searching for the mystical Isle of Avalon but on a quest for the Holy Grail.