11

The Name of the King

My research had led to Viroconium as the most likely seat for a historical King Arthur or, at the very least, whoever it had been who united the Britons at the time Arthur is said to have done just that. As far as I knew, I was the first to suggest that Arthur had been a king of Powys. However, on a visit to Oxford University to further study early British records, I was shocked to discover a passage in an old manuscript implying that someone had already identified Arthur as a Powys king—over thirteen hundred years ago. I came across this fleeting but crucial allusion in the work of a seventh-century bard called Llywarch, its significance apparently completely overlooked by historians for centuries.

In the previous chapter, I briefly discussed the Battle of Catraeth in northeast England, between the Angles and warriors from the Pict kingdom of Gododdin around the year 600. More specifically, it was a major encounter fought for control of northern England between a coalition of the Angle kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira and the British kingdom of Rheged in alliance with Gododdin. The battle was an overwhelming defeat for the Britons, leaving most of northern England under Angle control.1 Many Britons migrated south, and among them was the young Rheged prince Llywarch, who fled to Powys where he ultimately became a royal bard. As we saw in chapter 5, bards served as advisors to Dark Age kings and were also poets who composed songs, known as “war poems,” to record the exploits of their patrons. It is in such surviving works that much regarding Dark Age history has been preserved, and those composed by Llywarch concerned the kingdom of Powys.

It is not known precisely when Llywarch died, but he is commemorated in early Welsh literature as Llywarch Hen, meaning Llywarch the Old, inferring that he survived to a considerable age for someone of his time. He certainly lived for another half century after the Battle of Catraeth, as he wrote a series of poems titled Canu Llywarch Hen (Songs of Llywarch the Old) recording the struggle of Powys to maintain its eastern territories in the 650s.2 The fight was ultimately lost, the Britons of the kingdom being forced west into what is now central Wales, abandoning their royal court, referred to by Llywarch as Llys Pengwern (Court of Pengwern). Its location is not revealed, but we can hazard a guess as to where it was. In Welsh, pen means “head,” either referring to the body part, or a principal person, place, or thing (just as in modern English), while gwern is the word for the alder tree. This court of the kings of Powys could perhaps have been anywhere in the eastern part of the kingdom, but a probable location was in the city Viroconium, as archaeology has revealed that it was finally abandoned by the Britons at this time (see chapter 10). Pengwern—or the court of Alderhead in English—may have been the name of the royal residence at the heart of Viroconium, mentioned in the previous chapter.

Along with surviving members of the Powys court, Llywarch was forced to flee for a second time in his life; on this occasion into central Wales, where he settled in a small monastic community at the northern end of Lake Bala, around forty miles west of Viroconium (see plate 15). According to legend, while sitting on the lake’s northeastern shore, he composed the Marwnad Cynddylan—the “Elegy of Cynddylan.” This was a war poem concerning his patron, King Cynddylan of Powys, who died valiantly attempting to defend the eastern half of his kingdom from Anglo-Saxon invasion. The work now survives at Oxford University, in the Bodleian Library, where it is preserved, alongside other Dark Age Welsh literature, in The Red Book of Hergest. From linguistic analysis the poem seems to have been committed to writing in its present form around the year 850. However, as many of the events, people, and skirmishes portrayed in the work are attested to and confirmed in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the Welsh Annals, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and also fit with modern archaeological discoveries, historians generally consider it to have been composed much closer to the events described. In other words, the poem as it now survives is likely to be an accurate rendition of Llywarch’s original.

Before discussing Llywarch’s reference to King Arthur, I need to explain a little concerning the state of Britain in the early seventh century. By the year 600 the Angle kingdoms of Norfolk and Suffolk had united into the new kingdom of East Anglia—the East Angles—and had pushed west into central England, where the new Angle kingdom of Mercia was founded (the name coming from the Anglo-Saxon mierce, meaning “border people”), absorbing many smaller British kingdoms to ultimately share borders with Powys. After the Angle victories in the north, the kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira united as the powerful kingdom of Northumbria, which, over the following half century, expanded south through the British kingdom of Elmet, threatening not only Powys but also their fellow Angle kingdom of Mercia. For the first time in two centuries, the Britons and their Germanic enemies formed a military alliance: Powys and Mercia united in an attempt to defeat Northumbria.3 Initially, the pact between Cynddylan of Powys and the Mercian king Penda was a success. The Welsh Annals refers to the Battle of Cogwy in 644, between the Mercians and Northumbrians, where the Northumbrian king Oswald was killed.4 Bede also mentions the battle and Oswald’s death,5 as does the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,6 although they both give its date as 642. In his Elegy of Cynddylan, Llywarch refers to this battle, where the British king and his army join the Mercians to save the day: “I saw the armies at Maes Cogwy [Cogwy Field], and the cry of men hard pressed until Cynddylan brought them aid.”7

The Powys-Mercian alliance kept the enemy at bay for around a decade, achieving their last victory over the Northumbrians at a site Llywarch calls Caer Luitcoet, generally favored as being the old Roman fortification of Letocetum on Watling Street, some forty miles east of Viroconium. Shortly after, however, the tides turned, and the Britons and Mercians were in full retreat. The Welsh Annals records that Penda was killed in 657,8 while Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle give the year as 655,9 elucidating that in a decisive battle not only Mercia’s own army but also those of their allies were decimated. Bede says that the conflict occurred near a river called the Vinwed, its location now uncertain.10 Wherever the battle was fought, the Northumbrian king Oswy, Oswald’s son, continued to advance. According to the Welsh Annals, the following year “Oswy came and took plunder,”11 suggesting that this was when eastern Powys was occupied by the Northumbrians and its native Britons driven into Wales. According to Llywarch’s poem, the Powys king Cynddylan died at this time, fighting with his back against a river called the Tren, possibly the River Tern where it meets the Severn just outside Viroconium.

Fig. 11.1. The kingdoms of southern Britain around AD 650: Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in italics.

■ ■ ■

It was in Llywarch’s description of Cynddylan’s last successful battle at Caer Luitcoet that I found his reference to Arthur. In an English translation of the Elegy of Cynddylan, made in the 1970s by the respected British historian John Morris, senior lecturer in ancient history at University College London, Cynddylan and his brothers were referred to as Arthur’s heirs.12 If this was correct, then Llywarch was evidently saying that the king of Powys in the mid-600s was a direct descendant of King Arthur, implying that Arthur had been a king of Powys himself—or, at the very least, that he was believed to have once been a king of Powys at the time. If the poem dated from the mid-seventh century as experts believed, then this was the second oldest known reference to King Arthur still in existence, the only earlier one being in The Goddodin poem discussed in the previous chapter. In fact, as The Goddodin reference fails to say where Arthur was thought to have originated, the Elegy of Cynddylan would be the oldest surviving work to place Arthur in a geographical setting. Not in the south or southwest of England, or in South Wales, or even northern England, as other Arthurian researchers had suggested, but in the central kingdom of Powys, precisely where my investigation had led. I had to see the original poem for myself.

Having obtained a photocopy of the relevant page in The Red Book of Hergest from the Bodleian Library, I read the original text, which was written in Old Welsh: this was the British language into which Brythonic was developing by the seventh century; modern Welsh came about by the 1300s. In the poem, Cynddylan and his brothers were described by the words canawon artir. The first person to translate the Elegy of Cynddylan into modern Welsh was Ifor Williams—professor of Welsh language and literature at Bangor University in North Wales—in 1935.13 In his work he transcribed the word canawon as the modern Welsh cenawon, meaning “whelps.” This is a word for a puppy dog, or a young animal or cub, but Williams’s research indicated that in Old Welsh it was often used to refer to offspring generally, particularly ill-fated human descendants. John Morris had clearly followed the same reasoning, which is why he had interpreted canawon to mean “heirs” in English. The word that both Williams and Morris took to be Arthur was artir; so, if correct, this would mean that the most accurate modern English translation of canawon artir would be “the ill-fated heirs of Arthur.”

But why should Arthur have been written as artir? Arthur is the spelling of the name pronounced “Ar-ther” in modern English, but there was no consistency of spelling until the first widely accepted English dictionary published by Samuel Johnson in 1755. In the medieval romances Arthur’s name is spelled in many ways, such as Arther, Artur, Ardure, Ardur, Ardir, and Arddyr. During the Middle Ages the th sound, as in “teeth” for example, was seldom written with a combination of the letters T and H.14 The same is true for Welsh, which followed the English example and only adopted a common spelling in the eighteenth century. In modern Welsh, the th sound can be written as a TH but is more usually written as a double D, such as in the name of the kingdom of Gwynedd—pronounced “Gwyneth.”15 In Old Welsh works, and in earlier Brythonic, the th sound was spelled variously in Roman letters with a double or single D, with a T and H, or with a simple T. Likewise, the ur sound could be written with a UR, a YR, an ER, or an IR. So artir could indeed have been pronounced “Arthur,” just as Williams and Morris transcribed it.

However, since my book on King Arthur was published in 1992, which alluded to this reference, various scholars who had never questioned the translations of the Elegy of Cynddylan made by Williams and Morris began to query its mention of Arthur. Artir, they protested, had to mean something else. First, there were those who said that as the word did not begin with a capital A, then it could not have been a personal name. In fact, the capitalization of the first letter of proper nouns did not become consistent in written English or Welsh until the late Middle Ages. (None of these people seemed to have noted that Nennius also wrote Arthur with a lowercase A.) Then there were those who decided to break the word apart. The word artir does not exist in Welsh, nor is it found in any ancient Brythonic text, implying that it was in fact a personal name. So some scholars came up with the notion that it might have been two separate words, ar and tir, which would indeed mean something in Welsh: “on land.” Accordingly, they interpreted the phrase as canawon ar tir, the “ill-fated heirs on [the] land,” leading others to jump one step further and translate it as “heirs of the land.” However, the original text clearly has artir as one word. Elsewhere, the poet employs the word ar (on) and tir (land) without ever joining them with other words. It was clear to me that some historians and literary scholars would go to any lengths to prevent Arthur from becoming more acceptable as a historical figure. I wondered if these same people would have questioned Shakespeare’s historical existence because his name appears in pre-nineteenth-century documents under various spellings, such as Shackspeare, Shaxsper, Shakspere, and Shakfer.

Some academics even resorted to complete irrelevancies in an attempt to dismiss the reference to Arthur in the Elegy of Cynddylan. I remember once being on a British radio show with a literary authority, invited on to dispute my King Arthur theory, who was reduced to questioning the authorship of the poem. There is a reasonable historical issue concerning Llywarch’s existence: he may possibly have been a legendary bard whose name was only later linked with the poems. The works now collectively called the Songs of Llywarch the Old might have been written by someone else. I personally doubted this but fair enough. The expert brought this up, saying that Llywarch may not have existed. The young academic stared at me with a glint of triumph in his eyes. Apparently, he was convinced he had blown my case out of the water. All I could do was shake my head and utter the single word “And?” The man was simply being pedantic. Whatever his or her name, someone had written the poem that seems to have been composed close to the time in question. The scholar quickly changed the subject.

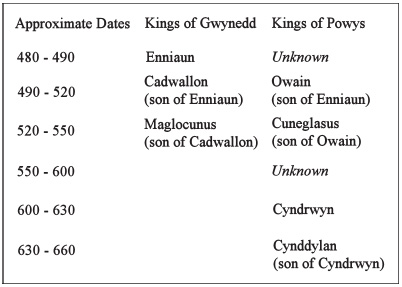

Nevertheless, the big question still remained: Who had ruled Powys at the time Arthur is said to have lived? Putting a name to that enigmatic figure, however, was easier said than done. Records concerning the kingdom of Powys during the relevant period are almost nonexistent; it was going to take some doing to identify its king around the year 500. The Pillar of Eliseg had been inscribed with a list of the kingdom’s rulers, from which we know that Vortigern was king of Powys in the mid-400s (see chapter 6). However, it was of no help at the current phase of my quest. The inscription was severely weathered, even when Edward Lhuyd copied it in 1696, and a period covering over two and a half centuries was missing. In his History of the Britons, Nennius tells us that Vortigern had three legitimate sons: Vortimer, Categrin, and Pascent, and the Pillar of Eliseg revealed that the third of these eventually secured his father’s throne, although Nennius explains that Pascent only ruled in the region of western Powys by permission of the high king Ambrosius.16 Between Pascent’s name and those of his later successors, the pillar’s surface had crumbled, leaving a gap in the list of kings from Pascent’s time, around 480, until the mid-eighth century. All that could be discerned from the inscription concerning this illusive period by Edward Lhuyd was a partial reference to the Powys king Concenn, the man who erected the stone around the year 850. The visible section recommenced with one Guoillauc, Concenn’s great-great-grandfather, in the mid-700s. Examining the Harleian genealogies in the Welsh Annals in the hope of filling the gap proved confusing to say the least.

One roll of Powys kings in the Welsh Annals chronicles Guoillauc as a distant successor to Pascent but records Pascent as the son of someone called Cattegir, not Vortigern, while a second list of Powys kings in the same manuscript makes Pascent himself Concenn’s great-greatgrandfather.17 If the latter is right, then Pascent lived around 750, meaning Vortigern must have existed three centuries after he clearly did, while the former fails to name Vortigern at all—a man whose existence is attested to by nearly all the historical sources. I realize family relationships, great-grandparents and all that, can be rather bewildering—it certainly is to me—but the bottom line is that no contemporary, or even near contemporary record, inscription, or genealogy revealed exactly who ruled Powys from around 480 to the early 600s, when one Cyndrwyn (Cynddylan’s son) came to the throne, as described in the Songs of Llywarch the Old. The Welsh Annals provides only one list of kings for the other British kingdoms included in the Harleian genealogies, but it has three for Powys, which all differ considerably in the names, number, and order of rulers. From this we can safely infer that whatever was going on in Powys during the late fifth and the sixth centuries, it had become a garbled memory by the time the king lists were committed to writing in the 900s (when the surviving Welsh Annals was transcribed); the reason most likely being that Powys was invaded and plundered by the Northumbrians in the seventh century.

I decided to concentrate further on the archaeological work at Viroconium. As none of the finds unearthed from the ruins of the ancient capital of Powys contained in the Rowley’s House Museum in Shrewsbury seemed to further my theory that it might have been the historical Camelot, its curator Mike Stokes suggested I visit the University of Birmingham, from where the excavations at Viroconium had been initiated and organized. I hoped that its archaeologists may have uncovered evidence to support my idea, its implications perhaps unwittingly disregarded. After all, no one, as far as I was aware, had previously suggested Viroconium to have associations with the Arthurian legend. I decided to keep any mention of King Arthur out of my inquiries, merely expressing an interest in Viroconium as a possible post-Roman capital of Britain. Birmingham, in the center of England, is Britain’s second largest city, and its department of Classics, Ancient History, and Archaeology is respected throughout the world. They had done exemplary work over two decades, piecing together the history of Viroconium, and one of the first things I learned about the city’s post-Roman era implied something of which I had been completely unaware. I already knew that part of western Powys had been annexed by the Cunedda family of Gwynedd by the late 400s (see chapter 10), but one particular archaeological discovery suggested that they may have taken over the kingdom entirely.

We examined in chapter 8 how important Celtic individuals often assumed animal names as epithets, sometimes passed on from generation to generation, and the Cunedda family was no exception. Cunedda and many of his successors bore the cun element in their names, which in Brythonic was pronounced “qune” and meant “hound”: such as Cunnan, Cuncar, Cunuit, Cunhil, Cunis, and many more. They are found in the Harleian genealogies and other Dark Age family trees, spread throughout the areas annexed by Gwynedd in north and central Wales during the late fifth and early sixth centuries. It is no hard and fast rule, but if you find the cun affix in the name of high-status Britons from the early Dark Ages, then it probably means that their ancestors originated in Gwynedd. And the grave of one such person was found in the ruins of Viroconium. During excavations in 1967 a tombstone was discovered just outside the city ramparts, bearing the inscription Cunorix macus Maquicoline—“Cunorix, son of Maquicoline” (now in the onsite museum at Viroconium). Archaeologists who found the stone believed that it had once stood in a more prominent position within the city, having been dragged to its eventual location by farmers at some point over the last few centuries.18 Whoever Cunorix was, he seems to have been an important individual, as the name suffix rix was a Celtic derivation of the Latin word rex, meaning “king.” The true name of the individual the tombstone was inscribed to commemorate appears therefore to have been King Cuno. The use of the word macus, a latinized version of the Gaelic mac, for “son of,” rather than the Brythonic map, additionally indicates that he was of Irish descent. This was not unusual for important figures in late fifth century Gwynedd; once they secured power in Gwynedd and drove out the Irish raiders, the Cunedda family enlisted the help of more friendly Irish settlers to bolster their numbers, partly explaining their successful military expansion. Consequently, the inscription implies that Cunorix was of mixed Irish British parentage and had become chieftain of some region occupied by the Cunedda family. From its style of writing, the stone was dated to about 480, around the time that Ambrosius seems to have relinquished power, and Enniaun was expanding the influence of Gwynedd into much of northern Wales and eastern Powys (see chapter 10). Although none of the archaeologists I spoke to appeared to have considered the idea, it occurred to me that the burial of a likely high-status member of the Cunedda line in Viroconium implied that Gwynedd’s influence had stretched much further into Powys than merely its western borders. Perhaps they had occupied the capital itself.

It’s doubtful that Cunorix would have been the actual king of Powys—his tombstone was not elaborate enough for that. Probably he was a visitor from another region who happened to die at Viroconium. But whoever he was, the trademark cun affix of the Cunedda dynasty got me thinking. It was while I was talking to the Birmingham team about the Cunorix stone that I was told something else I had previously not known. In the early post-Roman period, the Brythonic word for “hound” was, in Roman lettering, spelled cun, but from around AD 600 it began to appear on inscriptions as cyn, which is also how it was then written in various manuscripts. The reason being that in Brythonic the vowel in the word was somewhere between U and Y and, in modern Welsh, is pronounced more like the letter I, as in “chin.” (Accordingly, some genealogies also spell cun as cin.) The first king of Powys we know of with any degree of certainty after Vortigern’s son Pascent was Cyndrwyn, named in the Songs of Llywarch the Old as the ruler of Powys in the early 600s, who, the poet tells us, was succeeded by his son Cynddylan. Both of these kings bore the cyn affix in their names, which would earlier have been written as cun. So these seventh-century rulers of Powys were almost certainly descended from the Cunedda line, which, together with the presence of a King Cuno in Viroconium around 480, would suggest that from the late 400s until the final abandonment of Viroconium by Cynddylan (whose name I now knew would have been pronounced “Qune-th-lan”) in the mid-650s, Powys had probably been annexed by the kingdom of Gwynedd. Accordingly, during the period Arthur seems to have assumed his role as high king of the Britons in the 490s, whoever ruled from Viroconium—the most likely seat of Arthur, if my theory was correct—had been a prominent member of the Cunedda family.

Whoever this was, he was probably closely related to Enniaun, the Gwynedd king who expanded his influence throughout much of Wales and into Powys in the 480s. In the last chapter we discussed how Enniaun’s son Cadwallon had been the king of Gwynedd during the 490s and discounted the likelihood of him having been the person who united the Britons to successfully push back the Anglo-Saxons at the time, spending much of his reign repelling fresh Irish invasions and retaking the island of Anglesey. So who might have taken charge in Viroconium? As the Pillar of Eliseg inscription and the various Dark Age genealogies provided no answer, I decided to examine what the monk Gildas had to say about the state of Britain during the time he wrote in the mid-540s. As this was only a generation or so after the period in question, perhaps there were clues as to who had ruled Powys around the year 500 in his On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain. I had to search for clues in his work because, frustratingly, Gildas fails to name anyone who ruled anywhere at that time.

As implied by its title, Gildas’s work was basically a tirade against his fellow Britons for fighting among themselves to allow the Anglo-Saxons supremacy. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in 514 a new wave of Saxons landed on the southern shores of Britain, forcing the Britons to retreat north, and within a few years they had established the new kingdom of Wessex (West Saxons) throughout the modern counties of Hampshire and Wiltshire.19 Bede reveals the reason for the Britons’ renewed misfortunes, saying that it was due to the civil wars fought between the various British kingdoms. He even cites Gildas as reprimanding the Britons for their stupidity.20 It was not too late for the Britons, however, as there is no literary or archaeological indication that the Saxons in the southeast or the Angles in the north and east of England had recovered from their defeats around the turn of the century. In his tirade Gildas urges the British kings to forgo their “wickedness” and unite once more to repel the invaders. He personally addresses the kings of the largest and most powerful British kingdoms by name. He reproaches Constantine of Dumnonia in southwestern England,21 and a king called Vortipor,22 whom he calls the tyrant of the Demetarum—the Demetea tribe who had established the kingdom of Dyfed in southwestern Wales—both of whose names have been found inscribed on contemporary monuments. And there is Maglocunus,23 the original Latin name of the king of Gwynedd recorded in the Welsh Annals and in various Dark Age accounts under the later Welsh rendering as Maelgwn (see chapter 10). Gildas addresses two other contemporary kings, Aurelius Conanus (possibly a descendant of Ambrosius, going by the name),24 and Cuneglasus25 but fails to reveal which kingdoms they ruled. As we have already seen, the largest native British kingdoms around AD 500 where Rheged, Elmet, Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed, Gwent, and Dumnonia, which still survived intact by Gildas’s time, as the Saxons had established their new kingdom of Wessex in the area previously divided between less powerful British chieftains in the south. Gildas identifies the kings of three of these: Dyfed, Dumnonia, and Gwynedd. Aurelius could have been from any of the other four, but where Cuneglasus ruled seemed fairly obvious to me. Judging by the cun affix in his name, Cuneglasus must have come from a territory previously annexed by Gwynedd. As there is no reliable evidence that Gwynedd extended its influence into South Wales (where Gwent was situated) or northern England (the regions of Elmet and Rheged) until after Gildas’s death, then the most probable kingdom over which Cuneglasus ruled was the only one left on the list: Powys.

Fig. 11.2. The kingdoms of southern Britain around AD 545: Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in italics.

I had managed to identify a viable king of Powys who reigned at the time Gildas wrote, around the year 545. So what was known about Cuneglasus? Sadly, very little! Gildas considered him a heretic, a butcher, and an adulterer and implied that, other than Maglocunus, he was the most powerful king in the land. Gildas speaks of him as the “ruler of many” and of waging war against his fellow countrymen with “special weapons,” presumably meaning that he had a formidable army.26 If Arthur had been actively engaged fighting the Anglo-Saxons in the 490s, as the various historical sources imply, then we can guess that he would have been, say, thirty-five or forty years old at the turn of the century. He might still have been alive around 520 but probably not much later for someone of the time. It is not known exactly how old Cuneglasus was in the mid-440s, but he was no spring chicken. Gildas chastises him for wasting his youth and early years, squandering his riches, and engaging in small-minded squabbles. Presumably, we can infer that he was at least middle aged, perhaps in his forties in 445. The person who ruled Powys around the year 500 could well, therefore, have been his immediate predecessor. The $64,000 question: Who had that been?

The Welsh Annals genealogies make mention of Cuneglasus, under the later Welsh spelling as Cinglas.27 He appears in the family tree of one Iguel map Caratauc. This was the Old Welsh spelling of Hywel map Caradog, the ruler of a small kingdom called Rhos around the year 800. By this time, the Anglo-Saxons had driven the Britons pretty much out of all that is now England and into what is now Wales. Powys had been reduced to a small region in west-central Wales, while Gwynedd had broken up into a number of smaller kingdoms, one being Rhos, a tiny area on the coast of northwest Wales still ruled by Cunedda’s descendants. Because Hywel (pronounced “Hugh-el”) had been a king of Rhos around the year 800, in no way means that his remote ancestor Cuneglasus ruled in that same area two and a half centuries before. Nonetheless, even today, many authors and websites refer to Cuneglasus as the king of Rhos, based solely on the evidence that his descendants had later ruled that kingdom. Contrary to what seems to be popular opinion in some circles, the kingdom of Rhos simply did not exist at the time Gildas was writing. Gildas himself tells us that Gwynedd was the mightiest of the British kingdoms; it was not to break up until well after his time. He even says that its king Maglocunus was triumphant, defeating and plundering other kingdoms.28 This hardly sounds like a man whose kingdom was falling apart. Remember, this is one of the very few contemporary accounts to survive from post-Roman Briton: Gildas is actually writing about someone alive at the time. Gwynedd was strong and intact and showing no signs of breaking up into smaller kingdoms, such as Rhos, when Gildas wrote. It is not known precisely when the kingdom of Rhos came into existence, but it was certainly not as early as Cuneglasus’s time. I really seemed to have upset some people in that region of north Wales by questioning their supposed history. I remember once, well after my King Arthur book was published, receiving a phone call from a disgruntled local who insisted that Cuneglasus had been a king of Rhos, based on his name appearing in the genealogies of that kingdom. I made my counterargument, and the phone call finished with—what I assumed—was us agreeing to disagree. However, a few weeks later the same individual called someone who had just published a piece concerning my work, incensed that I continued to propound that Cuneglasus was a Powys king—even though he had told me I was wrong. Some people! I could only retort with what I have since had to repeat on many occasions. To say that Cuneglasus had been king of the tiny kingdom of Rhos, just because his descendant had been, would be like saying that George Washington had been president of England, not the United States, because his great-grandfather had come from here.

There could be little doubt in my mind that Cuneglasus had been a king of Powys. What further supported this conjecture was that the Harleian genealogies list Cuneglasus and Maglocunus as cousins: both were the paternal grandchildren of Enniaun, the powerful king of Gwynedd, who seems to have annexed Powys by the 480s.29 His son Cadwallon had succeeded him in the 490s (see chapter 10), followed by his son Maglocunus. Cuneglasus is listed as the son of Cadwallon’s brother. The implications are that after Enniaun’s death, his lands had been divided between his two sons, Cadwallon inheriting Gwynedd, and his brother Powys. Alternatively, Cadwallon might have been overall king of the two regions, and when he became tied up dealing with fresh invasions from Ireland, his sibling declared independence. One way or the other, their respective sons Maglocunus and Cuneglasus both ruled separate kingdoms by the time Gildas was writing a generation later. However, the Welsh Annals genealogies were not only supportive evidence that Cuneglasus was indeed a king of Powys, but they also revealed the name of the most likely person to have been ruling the kingdom at the time Arthur seems to have lived: he was Cadwallon’s brother and Cuneglasus’s father. His name was Owain Ddantgwyn (pronounced “Owen Than-gwin”), Ddantgwyn meaning “white tooth.” He presumably was so named because he had particularly good teeth for someone of his time.30 This was certainly a big kick in the teeth for me. I had finally put a name to the most likely figure to have ruled from Viroconium around AD 500. But the person who seemed closest to being the historical figure behind the King Arthur legend—having lived in the right place and at the right time—was not called Arthur. My entire investigation collapsed to nothing, just when thought I was so close to solving one of the world’s great mysteries.

Fig. 11.3. Southern Britain, showing the location of the eighth century kingdom of Rhos.

It took some time for me to recover from this revelation and to appreciate that all was not lost: far from it. His name might not have been Arthur, but I was convinced I had identified the man around whom the Arthurian legends eventually formed. An examination of the surviving historical sources, alongside the archaeological evidence, clearly revealed that, following a period of defeat in the 480s, something dramatically changed for the Britons: they went on the offensive during the 490s, ultimately achieving a decisive victory over the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Badon around AD 500. And someone—a strong and influential British leader—had to have been behind it. No contemporary or even near contemporary work, record, or inscription reveals who this person was or where he or she had come from. If it did, then there would be no mystery to solve. Nevertheless, someone had to have united the various British kingdoms into a formidable force during the 490s, just as Ambrosius had done in the 470s. The oldest surviving work to identify this leader is Nennius’s History of the Britons, dating to around 830, that records his name as Arthur. (Although the older works, The Gododdin and, seemingly, the Elegy of Cynddylan poems, make reference to Arthur, they are fleeting allusions in which he is not specifically identified as the British leader around the year 500.) After this time the various accounts, stories, and legends concerning this Arthur were committed to writing, establishing the basis for the later Arthurian romances of the Middle Ages. In all likelihood they already existed in some form or other, as Nennius seems to have considered Arthur to have been a well-known figure. If he had not been, then it’s reasonable to assume that the author would have told us more about him, such as where he came from or how he had assumed power. Instead, he merely tells us: “Then Arthur fought against them in those days with the kings of the Britons.”31 We can surely infer from this terse introduction that Nennius expected his readers to know exactly who Arthur was. Historically, the most likely kingdom from which this leader came was Powys, and its capital of Viroconium was by far the most sophisticated city in Britain during this period, a period when most Roman towns had been long abandoned and many Britons had reverted to living in elevated armed settlements or hill forts. As far as I was concerned, the person who initiated the British campaign that severely damaged the Anglo-Saxon cause for decades and led the Britons to victory at Badon had his or her seat of power in Viroconium. This surely had to have been the same person who Nennius later referred to as Arthur. I may not have found an individual called Arthur, but I had almost certainly identified the man later referred as such—namely, Owain Ddantgwyn.

How, then, did the name Arthur originate? Maybe it was a later invention, applied to the man who led the Britons around the year 500, as his true name had been forgotten. Just like his capital eventually became known by the fictitious name Camelot. Alternatively, Owain’s name may have morphed into Arthur during the period separating his life from the time Nennius wrote, similar to Ambrosius becoming Emrys in later Welsh literature (see chapter 6). Some Arthurian researchers had suggested the name evolved from the Latin Artorius. The idea was popularized when the Arthurian poem Artorius was published by the English poet John Heath-Stubbs in 1973, followed by the King Arthur novel Artorius Rex by fantasy author John Gloag in 1977. Historically, there were a couple of Roman soldiers recorded with that name in Britain: Lucius Artorius Castus during the late second century and Artorius Justus in the third. Nevertheless, I found nothing to back up the notion that Artorius was the original version of the name Arthur. Certainly, no one by the name Artorius is known to have had links with Britain anywhere around AD 500. What I did find interesting is that the name Arthur did not seem to have been used in any context until after the time King Arthur is said to have lived.

The name Arthur (in whatever spelling) does not appear on record anywhere until the late sixth century. Around this time, no less than six British genealogies include children named Arthur. All of these people were born too late to have been the fabled king around the year 500, but it does suggest that the name had suddenly become popular. The given name Gordon was in vogue in the late nineteenth and during the twentieth century, beginning with Victorian parents christening their sons with that name after the British general Charles Gordon became a national hero, dying at Khartoum in the Sudan in 1885. Before this time Gordon had only been a surname. Perhaps something similar had occurred during the sixth century: people began to name their sons after a recent national hero. It occurred to me that this not only indicated that a famous figure called Arthur might have lived in the early 500s, but that, as the name did not appear earlier, whoever this figure was he might well have been the first to have that name. Was it coined especially for him? There are plenty of examples from world history where titles first bestowed on a particular warrior later became adopted as given names, for example, the Mongolian warlord Genghis Khan, whose name was actually his personal title, meaning “Universal Ruler.” The name Genghis (Universal) was afterward given to many Mongolian children. Something similar might have happened with Arthur. So, like Genghis Khan, did his name have some original meaning?

Arth, the first syllable in the name Arthur, is the Welsh word for “bear,” just as it had been in earlier Brythonic. Could the name Arthur, I began to wonder, have derived from a title—the Bear? As we have seen, it was common practice for Britons at the time to adopt or be designated by the names of real or imagined creatures to denote their prowess or some specific trait. Maglocunus, for example, is specifically referred to by Gildas as the Dragon,32 the title he seems to have inherited from his grandfather Enniaun. The significance of this had not occurred to me before. My investigation abruptly assumed an entirely new complexion. Maybe Arthur had actually been the title of the historical figure later remembered by that name. It would not be the first time famous historical figures had gone down in history under their epithets. Other than Genghis Khan, whose real name was Temujin, there were the Roman emperors Caligula, a term meaning “little boots” (a nickname he acquired as child as he enjoyed dressing as a soldier), whose true name was Caius, and Augustus, a title meaning “majestic,” whose real name was Octavian. In these cases we happen to know their real names as records have survived. But what if our fabled king of the Britons had only been remembered under his title, his real name having been either forgotten or simply superseded by his more familiar epithet? If so, then Owain Ddantgwyn could well have been King Arthur after all.

Just as the name Ambrosius has been shortened to Ambrose and rendered in Welsh as Emrys in a very short time (see chapter 6), the title Arth could just as easily—in fact, far more readily—have become Arthur. I could envisage a number of ways it might have occurred. For example, those who spoke Latin might have called him by their word for bear, ursus. Perhaps he was known by Brythonic speakers as Arth, and Latin speakers as Ursus, the two eventually being joined to form Arthursus, later shortened to Arthur, as Marcus is shortened to Mark and Antonius to Antony. Another possibility: in Welsh “the bear” is written as yr arth (pronounced “ur arth”), which might simply have developed into the more lyrical Arthur. One way or the other, the name Arthur almost certainly originated with a title derived from the word for bear, just as many members of the Cunedda dynasty had the Brythonic word for hound in their names. Accordingly, Owain was not only an excellent candidate for a historical Arthur, he may even have been called by that appellation. Perhaps, after assuming power, his birth name was discarded; like Genghis Khan and Augustus Caesar, he was only referred to by his title, particularly since Owain was a common name at the time.

Other than his name appearing in the genealogies, nothing whatsoever was known about Owain Ddantgwyn. (At the time of writing, I see that some websites still refer to Owain Ddantgwyn as a king of Rhos. The same argument regarding Cuneglasus applies: there is no evidence whatsoever that Owain was a king of Rhos.) I decided, therefore, to return to the work of Gildas to see if I could learn more about his son Cuneglasus. Immediately, I was staggered to see something that I had previously read over without taking much notice. While chastising Cuneglasus concerning his behavior, Gildas refers to him as the Bear:

Why have you been rolling in the filth of your past wickedness since your youth, you bear, ruler of many, driver and rider of the chariot which is the bear’s receptacle?33

This is a fairly literal translation of Gildas’s original Latin, but it imparts far more than may first seem apparent. For a start Gildas is not implying that Cuneglasus is tearing along in an actual chariot, literally playing around in his own excrement. That much might be obvious, but the author is employing a further metaphor. The term he uses, receptaculi ursi (bear’s receptacle), would not mean literally the “bear’s cup” but was denoting something of importance that had once belonged to the bear. In Latin the word receptaculum does mean a vessel meant to contain something, but Roman writers often used it metaphorically to refer to a cherished object, place, or concept: something that held significance. And his words sessor auriga que currus (meaning “driver and rider of the chariot”) were also used to imply domineering control or despotism. The Latin term for charioteer was also used to refer to the leader of an army. So what Gildas is really saying is that Cuneglasus is in command of something significant that had once been the bear’s. Some academics translate this line into English as “commander of the bear’s stronghold,” inferring his kingdom, and others as “commander of the bear’s army.” But there’s a mystery. Gildas specifically refers to Cuneglasus as the bear. So how can he be the bear himself but also apparently the commander of the bear’s kingdom or army? We can only infer that he is saying that Cuneglasus, known as the Bear, was now in charge of either the forces or kingdom that had once been the powerbase of someone previously called the Bear. This passage seemed to have puzzled historians, but from what I had pieced together, it all made perfect sense. These animal name epithets were often passed on to successors, such as the dragon kings of Gwynedd. It appeared, then, that not only had Cuneglasus been given the sobriquet or title, the Bear, but had inherited it from his predecessor. As this had been his father, then it would seem that in Gildas’s On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain—written within living memory of the Battle of Badon—I had found confirmation that Owain Ddantgwyn had indeed been known as the Bear, or Arth in Brythonic. Evidently, not only was Owain the historical figure upon whom the legends of Arthur were later based, but he could indeed have been known as Arthur.

Nonetheless, some historians I spoke to suggested that Gildas’s use of the word bear, when referring to Cuneglasus, might also have been metaphorical. There is a passage in the Bible, in the Book of Revelation, where the Great Beast—the antichrist—is described:

And the beast which I saw was like unto a leopard, and his feet were as the feet of a bear, and his mouth as the mouth of a lion: and the dragon [the Devil] gave him his power, and his seat, and great authority. 34

Gildas addresses five of his contemporary British kings: Cuneglasus and Maglocunus, whom he calls respectively the Bear and the Dragon, and likens the other three to two of the other creatures mentioned in this biblical verse. Concerning Vortipor of Dyfed, he says he is dangerously cunning “like a spotted leopard,”35 while he insults Constantine and Aurelius by insinuating that they are bound to the whims of their mothers, as are “lion whelps.”36 I agreed that Gildas may indeed have been inspired by the quotation from the Book of Revelation, but he probably got the idea to associate his nation’s rulers with the antichrist as two of these figures already bore the titles of two of the creatures associated with the Great Beast. He addresses Cuneglasus and Maglocunus directly as the Bear and the Dragon,37 while clearly only comparing the other three to the animals in question. We have already seen that Maglocunus was undoubtedly known as the Dragon. This was certainly not as a term of denigration, as demonstrated by the fact that the epithet was passed on to later generations. Indeed, when Gwynedd again rose to prominence in later centuries and assumed control over much of Wales, the insignia of its leader—the dragon—was adopted as the symbol of all Wales and is still on the national flag. (Try telling the Welsh that their country’s emblem was inspired by a reference to the antichrist.) On further investigation I found that exactly the same applied to Cuneglasus’s descendants.

Fig. 11.4. Rulers of Gwynedd and Powys from the late fifth to mid-seventh centuries.

We discussed above how Penda and Cynddylan formed an alliance in the mid-600s. In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede provides evidence that this alliance was cemented by an interdynastic marriage between the ruling families of the Angle kingdom of Mercia and the British kingdom of Powys. He names Penda’s wife—Mercia’s queen—as Cynwise.38 Not only is this a British name, as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon one, but it also has bears the affix cyn, of Cynddylan’s dynasty. Bede also refers to Cynwise and Penda’s daughter as Cyneherga, a half Brythonic, half Anglo-Saxon name.39 There can be little doubt that some leading member of the Powys royal family, perhaps Cynddylan’s sister or daughter, was married to Penda in order to seal the treaty, as was common practice in the ancient, post-Roman, and medieval world. And their descendants continued the line as rulers of Mercia. Following the death of Penda around 655, the Mercians came under Northumbrian domination, but a few years later they revolted, and Penda’s son Atheldred defeated the Northumbrians at the Battle of Trent in 679. By the mid-700s Mercia had become the most powerful kingdom in England, but a century later it was superseded by the Saxon kingdom of Wessex, which eventually conquered the entire country, founding the united kingdom of England under King Athelstan in the early 900s.40 Athelstan and his successors allowed many of the former Anglo-Saxon kingdoms a certain degree of autonomy, though relegating them to what were called earldoms, and their rulers were known as earls (from the Saxon word for chieftain). There were therefore the earls of Northumbria, Kent, Sussex, and so forth, who now functioned as regional barons. The former dynasty of the kingdom of Mercia became the earls of Mercia. Over time these earldoms became further divided into what we would now call counties, which is why many modern British counties (including those in Wales, which was annexed by the English during the Middle Ages) carry the names of the old kingdoms, such as Essex, Middlesex, Gwynedd, and Powys. By the medieval period Mercia was divided into a number of such regions, one of which was the county of Warwick (see plate 16), whose earls were directly descended from the ancient kings of Mercia. (Today it is called Warwickshire, and its capital, or county town, is what had been the seat of the medieval earls, the town of Warwick). Significantly, during the Middle Ages, the heraldic crest of the Warwick earls was the image of a bear holding a staff. Just like the Welsh Dragon, the Warwick banner seems to have originated with the earls’ ancestors, the rulers of Mercia, who had used the bear as their emblem.

According to the John Rous, an English historian writing around 1450, the earls of Warwick were descended from an ancient warrior called Arthgallus, who had lived at the time of Arthur and whose emblem had been a bear. (Rous’s work, commonly known as the Rous Roll, is preserved in the British Library, London, where it is cataloged as Add. MS 48976.) Astonishingly, Rous says the reason why Arthgallus had used this image is because “the first syllable of his name, in Welsh, means bear.” Nothing else is known concerning this Arthgallus. However, John Rous only went halfway translating the name. The second syllable, gallus, is a Gaelic word of original Celtic origin meaning “bold,” still used in common speech in parts of Scotland today. So the name Arthgallus actually means “Bold Bear.” I could not help but wonder whether this Bold Bear, who was thought to have lived at the time of Arthur, was none other than Arthur himself. One way or the other, the Mercians had adopted the bear as their kingdom’s emblem, just as Gwynedd had adopted the dragon. So the notion that Gildas is calling Cuneglasus the “bear” merely to insult him is quite clearly wrong.

It was only at this point that I realized something else—something extremely significant—about Owain Ddantgwyn that fitted with the Arthurian saga. Geoffrey of Monmouth and the subsequent romancers portrayed Arthur as the son of Uther Pendragon. I had previously identified Enniaun of Gwynedd as the most likely historical figure upon whom Uther was based, the words Uthr Pen Dragon in Welsh, meaning “Terrible Head Dragon” (see chapter 8). Owain Ddantgwyn was Enniaun’s son! Remarkably, not only was Owain the most likely historical figure behind the King Arthur story—a man who seems to have borne the title Arth—his father may have been known as Uther Pendragon. I now had no doubt that I had finally identified the man at the heart of the Arthurian legend.