12

Camlann

Although I had identified a historical King Arthur, my quest was far from over. The ultimate aim was to discover his final resting place—and that was going to be anything but easy. Almost nothing was known concerning the life of Owain Ddantgwyn, let alone where he was buried. I at least knew how he died. In his On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, Gildas reveals that Owain was slain in battle.1 We shall return to this reference shortly, but let’s take things one step at a time. During the Dark Ages when important figures died in action, unless they were relatively close to their family burial site, they would generally be buried nearby (so long as there was anyone left to bury them). If I were to discover where Owain was laid to rest, I first needed to determine where he fell. As Gildas unfortunately neglects to reveal this essential information, I returned my attention to the Arthurian legend. Where was Arthur thought to have died? The quick answer, as we saw in chapter 3, was at a place called Camlann. However, precisely where this was originally thought to have been was far more difficult to answer.

The popular story of Arthur’s death is that he was killed during a civil conflict, fighting his rebellious nephew Modred. In a single battle Modred is slain by Arthur, but not before he inflicts a fatal wound on his uncle, and the action ends in stalemate. This is the account made popular by Thomas Malory during the fifteenth century in his Le Morte d’Arthur.2 Malory did not invent the themes in his narrative, however. Although he certainly added elaborations, he transcribed and retold accounts that had already developed throughout the Middle Ages. Malory sets the ill-fated battle between Modred and Arthur near the town of Salisbury in southern England, although he apparently did this to fit with his locating Camelot at nearby Winchester—which is a purely fictional interpolation, as we determined in chapter 2. Earlier authors tended to place the Battle of Camlann in Cornwall, inspired by Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain of 1136.3 We also saw how Geoffrey’s reliability is suspect when it comes to his Cornish Arthurian connections, as he appears to have been pandering to his patron’s brother, the Earl of Cornwall. Nevertheless, neither Geoffrey nor any other medieval author invented the Battle of Camlann; it is listed in the Welsh Annals that record “the strife of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut perished.”4 So we know for certain that in the 900s, when the Welsh Annals was compiled in its present form, Arthur was believed to have died at Camlann along with someone called Medraut. Although Medraut was the Old Welsh rendering of the name Modred, the Welsh Annals fails to say who he was, or indeed whether he fought on the same or opposite side to Arthur. Nevertheless, this does additionally indicate that the notion of Arthur dying alongside his nephew Modred was not invented by Geoffrey of Monmouth or any other medieval author.

As with so many Arthurian sites, my attempt to locate Camlann was not helped by the medieval romances. Although Camlann was named as the site of Arthur’s last battle, other than the spurious locations near Salisbury and in Cornwall, none seemed to reveal where it was fought. Even the earlier Welsh Arthurian tales appeared to be of no use. Nonetheless, even if the battle was merely a legend, there had presumably been a place called Camlann where the story was set. Sadly, like Badon, Camlann no longer survives on the modern map. British place names have often changed considerably since the post-Roman era; sometimes completely—after the invading Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and Normans renamed a location—and sometimes due to the evolution of language. (We don’t speak the same today at we did in Shakespeare’s time, and Shakespeare didn’t speak much like someone from the Middle Ages.) Add to this the inconsistency of spelling in earlier times, and it is often the case that locations cited in Dark Age works can no longer be identified. Unfortunately, the name Camlann itself was of little help. In Welsh cam means “crooked,” as in bent or winding, found for example in the name of the London district of Camden, meaning “Crooked Valley.” And lan most directly translates as “shore” but can be applied to any waterside, such as the sea, a lake, or a stream. It is particularly associated with rivers, such as the town of Rhuddlan, meaning “Red Bank,” beside the River Clwyd in northwest Wales. Camlann, therefore, probably meant “Crooked Bank,” but this was of little help in locating where the battle was fought. The Crooked Bank in question could have been just about anywhere in the country.

Some scholars have speculated that the word Camlann inspired Camelot as the name for Arthur’s court. We discussed in chapter 2 how the name Camelot appears to have been the invention of the twelfth-century French poet Chrétien de Troyes. He might indeed have been so inspired. Nevertheless, there is no suggestion in any of the Arthurian romances that Arthur’s final battle was fought at his capital. There are many locations throughout the British Isles that Arthurian researchers have identified as Camelot (see chapter 2), but strangely the same is not true for Camlann. Usually, authors tend to go along with the romance writers, locating the battle either near Salisbury or in Cornwall. There is one notable exception. Those who subscribe to the theory of a northern King Arthur favor Camlann to have been the Roman fort of Camboglanna that stood toward the western end of Hadrian Wall. This fort, close to Carlisle in northwest England, is recorded in the early fifth-century Roman military document, the Notitia Dignitatum (discussed in chapter 9), its name thought to be derived from the Brythonic Cambo Glanna, meaning “Crooked Glen.” Certainly cam meant “crooked,” and glan was a Gaelic word for “glen,” so this was quite possibly the original name of the district in which the fort stood. However, unless you happened to agree with the northern King Arthur theory, which I personally doubted (see chapter 10), then there seemed no particular reason to favor it over many other places in Britain, such as Camden, Camberley, and Camelsdale, all of which meant Winding Valley (den, ley, and dale are all old words for a valley).

Having reached something of a dead end trying to identify a place once called Camlann, I turned my attention to the enigmatic Modred, Arthur’s opponent at the battle. Who exactly was he? Malory depicted him as both Arthur’s nephew and his son, conceived during an incestuous affair with his sister Morgause. In later adaptations Morgan le Fey became Modred’s mother, being portrayed as Arthur’s half-sister, who transformed into a malicious sorceress when she failed to inherit the throne. However, in the original romances Modred was the son of Arthur’s sister Anna and her husband, a man named Lot. Early Welsh literature also referred to Modred as Arthur’s nephew but without elaborating on his parentage. Significantly, though, the Welsh triads (see chapter 6) portrayed Modred in a somewhat different light to the popular Arthurian saga. The Battle of Camlann was mentioned a number of times in the triads, where, as in the medieval romances, it was said to be the result of internal British strife between Arthur and Modred. The triads differed, however, in depicting the battle as a victory for Modred. The triad, The Three Unfortunate Councils, for example, blamed Arthur for dividing his forces at Camlann, affording Modred the advantage.5 Although Arthur was said to have died at the battle, nothing was disclosed concerning Modred’s death. What was made clear, however, was that after the battle the country returned to a state of feuding between its native British kingdoms. The big problem I faced, once again, was that the triads failed to reveal where the Battle of Camlann was fought.

Something I did find particularly interesting was the parallel between the story of Arthur’s demise and the death of Owain Ddantgwyn. Like King Arthur, Owain appeared to have been killed by his nephew. Gildas tells us that Maglocunus overthrew his uncle in battle: “Did you not, in the first years of your youth, bitterly crush with sword, spear, and fire, your uncle the king and his courageous soldiers?”6 Although Gildas typically failed to name this king, there is only one person it could be: Owain Ddantgwyn, the only uncle we know of who was actually a king. Although the medieval Arthurian romances had Arthur and Modred dying together, whereas Maglocunus certainly did not die fighting his uncle, Owain’s fate did fit with the Welsh triads portraying Modred as the victor at Camlann. The triad authors seemed to have drawn upon reliable information concerning the state of Britain immediately after the time Arthur was thought to have lived. The triad The Three Frivolous Causes, for example, referred to the Battle of Camlann as a direct cause of the eventual loss of England to the Anglo-Saxons:

The third [frivolous cause of the Britons’ woes] was the battle of Camlann, between Arthur and Modred, where Arthur and 100,000 of the best British warriors were killed. Because of these three foolish battles, the Saxons took the country of Lloegria [England] from the Cymry [Britons], for there were too few left to oppose them.7

As seen in chapter 11, the Saxons did renew their advance in the early sixth century, ultimately conquering all England. As these triads, evidently summarizing earlier Dark Age war poems (see chapter 6), appeared to demonstrate an accurate grasp of post-Roman British history, it was reasonable to suppose that the original accounts the authors adapted had portrayed Modred as both the victor at Camlann and as a survivor of the conflict. There was, however, a big difference between all the accounts—medieval and Old Welsh—concerning Arthur’s death at the hands of his nephew and Owain being killed by his nephew. The usurpers have different names: Modred and Maglocunus. Was the name Modred, I wondered, a later rendition of the name Maglocunus?

Maglocunus’s name certainly did change over time. It is thought to derive from the Latin magnus (great) and the cun element (hound) that so often appears in the Cunedda lineage. Later Welsh works refer to him as Maelgwn. The first syllable, mael, in Gaelic means “chief,” while the second, gwn, is thought to have been a localized spelling of the Brythonic cun. So the Latin Maglocunus and the Old Welsh Maelgwn mean basically the same thing: “Great Hound.” It must have been rather confusing to later generations that no longer employed creature names as titles: a man born Maglocunus, the Great Hound, became known as Maelgwn, but also bore the title the dragon. No wonder there is so often ambiguity in early Welsh and medieval literature about exactly who did what and to whom. The name Modred also appears in various renderings, such as Medrawd, Medrod, and Medraut. It was only after Geoffrey of Monmouth in the twelfth century that the name Modred was settled upon, but even then the inconsistency of spelling still resulted in variations, such as Mordred, Moddred, and Medred. The origin of the name Medraut, as it is found in the earliest work to include him, the Welsh Annals, is a mystery. It doesn’t readily break down into anything in Welsh or Brythonic. However, the nearest meaningful term, mudrwg, from the Welsh mud (silent) and drwg (evil) refers to a sleeping or undetected enemy. This, therefore, could have been a name coined by the Britons for the traitor who destroyed British unity and handed the initiative to the common enemy. Perhaps confusion concerning the man’s two names, Maglocunus and Maelgwn, together with his tile, the dragon, was made all the more problematic after he was further dubbed with a term for traitor. This might well have resulted in a single person being later recorded as two separate figures.

Alternatively, it’s possible that accounts of Arthur being killed by his nephew were misconstrued by early Welsh authors. Noting references that someone called Medraut died with Arthur, they wrongly assume he was the nephew in question. Certainly by the time the Welsh Annals was compiled in the 900s, Modred and Maglocunus were regarded as different people, as Medraut is said to have died at Camlann, while Maelgwn died of plague a few decades later.8 However, this Medraut may have had nothing to do with Arthur’s death. Welsh authors might deliberately have ignored reference to Maglocunus being Arthur’s treacherous nephew, as he became something of a national hero, or “founding father,” to the Welsh when Gwynedd’s influence spread throughout much of the country in the seventh century. Once Maglocunus’s name was effectively expunged from the Arthurian saga, later writers seized upon the Medraut who fell at Camlann—someone about whom nothing else was known—as the most likely villain of the plot. Nonetheless, whether or not Modred and Maglocunus were one and the same was not the salient issue I needed to resolve. Owain Ddantgwyn was the figure I had identified as the historical Arthur, and he was killed by his nephew. The big question was still “where?”

The major problem I faced was Gildas’s failure to reveal the location of the battle where Maglocunus defeated his uncle. It certainly seemed to have taken place around the most likely period in which Arthur’s last battle was fought. The only historical source to date the Battle of Camlann is the Welsh Annals, which lists it as year 93. As we saw in chapter 9, the Welsh Annals does not use the AD system of dating. Instead it starts with the Saxon advent as its year 1, which according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle occurred in AD 449. Accordingly, year 93 would be 541. Bede, conversely, dates the Saxon advent as 447,9 which would mean that the Annals’ year 93 is 539. (Various scholars derive different dates, a couple of years either way.) However, we also saw that the Welsh Annals is sometimes out by a decade or so regarding the dating of early events. One thing that we can be sure of, though, is the number of years the Annals separates the battles of Badon and Camlann. It lists the Battle of Badon as year 72, which means that, according to the compiler, twenty-one years divided the two events. We derived a reliable dating of Badon to around AD 500, give or take a couple of years, from Gildas’s work, and this tallies with what we deduced from Nennius’s account, which, on analysis, places Arthur’s period as British leader as beginning in the 490s (see chapter 9). Nennius does not mention the Battle of Camlann, however, as his writing concerned only Arthur’s earlier victories.10 If the Welsh Annals’ separation of the two battles by twenty-one years is right, then Camlann would have occurred sometime around the year 520, which fits with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recording that in 519 the Saxons renewed their advance into British territory, defeating the Britons and establishing their kingdom of Wessex.11

The tide of warfare had clearly turned against the Britons around 520 and continued thereafter in favor of the Anglo-Saxons. This would appear to be the period Gildas laments, blaming Maglocunus for overthrowing his uncle, an act that divided the country and resulted in the onslaught of the pagan enemy. Gildas specifically relates how this occurred in the early years of Maglocunus’s reign, as he describes him as a youth at the time.12 Like his cousin Cuneglasus, Maglocunus appears to have been middle aged around 545 when Gildas wrote, which would indeed make him a young man a quarter of a century earlier. (Interestingly, this is another correlation with the Arthurian story, in which Modred is depicted as a youth when he rebels against King Arthur.) So I had a date for both Owain’s demise and for Camlann coinciding around AD 520. And this certainly did help to narrow down the location of the battle.

I had deduced that Owain Ddantgwyn was king of Powys. If he was Arthur, then this would not contradict with him also being the overall British leader. Nennius relates that Arthur had fought “with the kings of the Britons, but he himself was leader of battles,” implying that although he was supreme commander, the various British kingdoms remained intact and autonomous.13 Arthur could indeed have been king of one such kingdom. I had also reasoned that when Gildas wrote, around 545, unity had collapsed, and Owain’s son Cuneglasus retained power only in Powys, while Maglocunus ruled Gwynedd. Gildas blames Maglocunus almost entirely for destroying British unity, ranting on for three whole chapters about his wicked deeds after killing his uncle.14 As the uncle in question was Owain Ddantgwyn, a king of Powys, then this would suggest that Maglocunus attempted to take over that kingdom. However, he must ultimately have failed, as by the period Gildas wrote, Cuneglasus seems to have ruled Powys. So the most likely scenario would appear to be that, after Badon, the alliance of British kings remained intact for a couple of decades while Owain was alive, but as he grew older and his hold on power lessened, Maglocunus saw the opportunity to attack his uncle and attempt to seize his kingdom. This meant that the site of the battle between Owain and his nephew would have to be somewhere in either Gwynedd or Powys.

There is actually a valley called Camlan, spelled with one n, some five miles to the east of the Welsh town of Dolgellau, and another, ten miles farther east, near the village of Mallwyd, both being in the eastern region of Gwynedd as it existed in the early 500s. However, neither was a likely site for a major battle fought between Gwynedd and Powys at the time. The Gwynedd capital had been at Caer Ddegannwy on the north coast of Wales, around fifty miles to the north of either Camlan, while the Powys capital of Viroconium was some fifty miles to the east of even the closest of the two locations. They both seemed completely out of the way for any strategic engagement between the primary forces of the two kingdoms.

I decided to contact a group that specialized in the reenactment of Dark Age battles and ask their opinion. From Gildas’s narrative it seemed that Maglocunus was the aggressor, so it was more probable that he was marching against Viroconium rather than Owain marching on Caer Ddegannwy. What strategy, I asked, would Owain have adopted had he learned of an army advancing from Gwynedd? Would he be advised to stay put in the capital, or move his forces out to meet them? The experts unanimously agreed that it would be far better to encounter the opposition in the field, rather than risk a siege. They concurred with my assessment that the two Camlans were too distant: it would have been crazy for Owain to march out so far from Viroconium when there were far better places to make a stand against Maglocunus’s army nearer to home. He would most likely have engaged the enemy at one of the defensive sites established where the old Roman roads crossed the border between the two kingdoms.

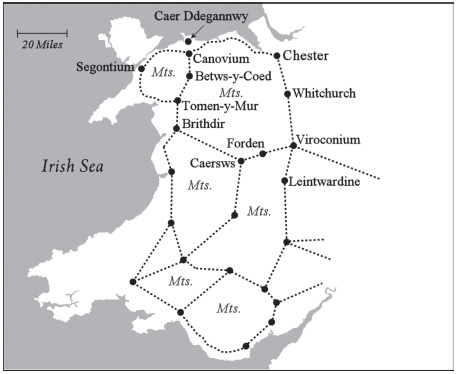

Fig. 12.1. Wales and west-central England: the principal Roman road network still in use in the early sixth century.

The Roman road network still survived pretty much intact and was by far the best, if not the only, way to maneuver armies in the early sixth century. The alternative was a long and treacherous haul over the mountainous regions circumvented by the roads. During the period there were only two logical routes to move a sizable armed force between Caer Ddegannwy and Viroconium. Two important Roman roads met at the fortification of Canovium, just to the south of Caer Ddegannwy. One followed the northern coast from Segontium to Chester, and then south to Viroconium, passing through the Roman town of Mediolanum, modern Whitchurch. The other, known as Sarn Helen, meaning Helen’s Causeway (named after a Roman empress), followed the River Conwy down to modern Betws-y-Coed, where it turned southwest through mountain passes to the old Roman fortifications at Tomen-y-Mur, and then south to Brithdir near the estuary of the River Mawddach. From here another road ran east to Caersws where it met the road to Viroconium, which passed through the Roman settlement at Forden. In the case of the first route, the experts suggested that Owain would be advised to march out to the border defenses at Whitchurch, around twenty-five miles north of Viroconium, and make his stand there; and in the case of the second route, they suggested that he should make a stand at the fortifications at Forden, some twenty miles to the southwest of his capital. It was while investigating the area around Forden that I came across a place name that seemed strangely familiar.

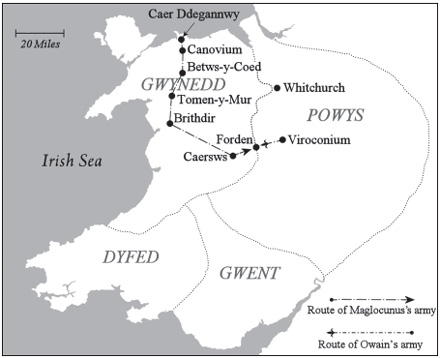

Fig. 12.2. Wales and west-central England: the likely kingdom boundaries and routes taken by Maglocunus’s and Owain’s armies to their battle at Forden.

The Roman road at Forden runs beside the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon defensive embankment of Offa’s Dyke. According to the experts’ reasoning, Owain’s forces would have established their position just beside this road, on high ground now marked by a later Norman earthwork known as a Motte and Baily, a series of defensive embankments and ditches surrounding an artificial hillock. Driving around this area, I came across a farm called Rhyd-y-Groes. I could not think where, but I was sure I had seen this name before somewhere during my investigations into the King Arthur mystery. I stopped to ask if anyone knew of any Arthurian associations with the area. No one immediately recalled anything, but I did learn that the meadow to the immediate south of the farmhouse had been called Rhyd-y-Groes for centuries. In English, the Welsh Rhyd-y-Groes meant “Ford of the Cross” and was originally the name of a ford crossing a minor river that wound through the land. A stone cross was thought to have once stood there, but now a bridge, called Shiregrove Bridge, takes the modern A490 road over the river at the location where the ford once crossed. On returning home I finally discovered where I had seen reference to Rhyd-y-Groes before. It was a passing mention in one of the Welsh Arthurian tales called The Dream of Rhonabwy, the same story that included the oldest description of Arthur’s sword (see chapter 9).

The Dream of Rhonabwy, now preserved in The Red Book of Hergest, is generally considered to have been composed in Powys around 1150 to address Madog ap Maredudd, a historical figure who ruled the kingdom in the mid-twelfth century. In 1149 Madog recaptured part of the county of Shropshire from the English, but while his army was away, the king of Gwynedd seized the opportunity to invade northern Powys. The story seems to have been written between that date and Madog’s death around 1159, as a cautionary tale likening his rash campaigning with King Arthur’s ill-fated demise at the battle of Camlann centuries before. I had virtually discarded The Dream of Rhonabwy as being of any help in my search for a historical King Arthur as it seemed to be largely allegorical in context. On reading it again I was shocked by its implications. Apart from Geoffrey of Monmouth, who unreliably places Arthur’s final battle in Cornwall, and Wace, who followed his lead (see chapter 3), it was the oldest surviving narrative to provide an actual location for the battle of Camlann—and a very precise one at that. I could not believe that I had not appreciated its relevance earlier. But then again, as far as I could tell, no other Arthurian researcher had either.

The tale concerns a dream experienced by its central character, Rhonabwy, one of Madog’s servants, in which he goes back to the time of King Arthur. At the start of the vision, Rhonabwy meets a messenger from Camlann who miraculously transports him to Arthur’s camp immediately before the battle.15 Soon after the hero meets King Arthur, the story becomes a symbolic tale concerning good and evil, right and wrong, and the power of the church versus the power of kings. Although the later part of the tale involves a mixed dreamscape concerning various episodes in Arthur’s life, such as him receiving his sword, the Battle of Badon, and the formation of his court, all jumbled with complex symbolism, the location of the battle of Camlann is quite specific. The tale ends before the commencement of the battle itself and provides no details concerning the actual engagement. However, Arthur’s encampment in the run up to the battle, where he is joined by various troops of horsemen, is said to be at a ford, specifically named as Rhyd-y-Groes, which crossed a river in the Havren Valley, a mile from his main forces.16 The area I visited around Forden exactly matched this description. The Havren, now spelled Hafren, is the Welsh name for the River Severn, and the ford of Rhyd-y-Groes that I had found was not only in the Severn Valley but exactly a mile to the southeast of the fortification at Forden where the experts on warfare of the period had suggested Owain’s main army would have been.

Astonishingly, I had been led to this area as one of the most likely locations for the battle fought between Owain and his nephew Maglocunus, quite independently of anything in any Arthurian narrative. Yet it was precisely here that The Dream of Rhonabwy author located the Battle of Camlann between Arthur and his nephew Modred. I was certain that I had identified both the site of Owain and Arthur’s final battle. Surely, it was far beyond coincidence that they were fought in the same place, especially as I had already reasoned that the two men were one and the same. We have seen how many of the early Welsh Arthurian writers had drawn upon earlier material as background to their narratives. It was therefore a reasonable assumption that either The Dream of Rhonabwy author had based his location for the battle on an earlier Dark Age war poem, or that during the twelfth century, in the kingdom of Powys where the story was composed, it was commonly believed that Rhyd-y-Groes was where Arthur’s final battle was fought. One way or the other, it seemed that this location had long been overlooked by Arthurian researchers because everyone was focusing on either the south or far north of England. Powys had been completely ignored.

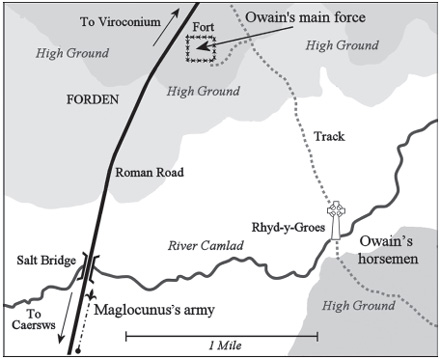

Fig. 12.3. The probable military scenario immediately before Owain’s final battle.

When I returned to survey the area in more detail, I could easily picture what may have occurred. The narrative places Arthur and his horsemen at the ford, a mile away from his main forces. Historically, the likely place for Owain’s army to have established its position was about a mile to the northwest of Shiregrove Bridge, on high ground overlooking the site. Through Forden the modern B4388 road follows the course of the old Roman road exactly, and to reach the fortification any advancing army would have to cross the river downstream from Rhyd-y-Groes where the road crosses it at a location now called Salt Bridge. Between the Shiregrove and Salt Bridges, the river winds its way across a smooth plane, but at the site of the original ford, it bends slightly around a spur of land rising sharply to the south. This meant that a considerable force of mounted warriors could remain there, hidden from anyone traveling along the Roman road from where it begins at today’s village of Caersws, fifteen miles to the southwest. It was the perfect place for an ambush by the Powys cavalry. If this was indeed where Owain fought his last battle, then I could imagine his horsemen charging across the valley to engage the enemy around Salt Bridge. The plan may have been for the troops in the Forden fort to come out to join them, catching the enemy in a pincer movement. Something, however, must have gone drastically wrong. Perhaps Gwynedd scouts had spotted Owain and his contingent at Rhyd-y-Groes, and Maglocunus attacked them instead. If so, with the element of surprise lost, the outcome would almost certainly have been Owain’s defeat. If this was how the Battle of Camlann was played out, it would certainly explain why the triads depicted it as a catastrophe caused by Arthur dividing his forces.

I was certain that somewhere along the winding river at Rhyd-y-Groes, the man behind the legend of King Arthur had finally met his fate. It was not just the fact that the tightly meandering river matched with a place called Camlann (Crooked Bank) that finally persuaded me beyond reasonable doubt that this was the site of the battle, but the name of the river itself. As far back as records went, this tributary of the nearby River Severn was—and still is—called the Camlad (see plate 17).