13

The Once and Future King

I was convinced that I had finally indentified the historical King Arthur: the British chieftain whose original name had been Owain Ddantgwyn. Not only was Owain known by the title Arth, but his father seems to have been called Uther Pendragon. Furthermore, just like Arthur, Owain was toppled by his rebellious nephew. Owain was a king of Powys, and the oldest reference to place Arthur’s origins in a geographical setting puts him in precisely that kingdom. He ruled from the most sophisticated city in the country during the specific period Arthur’s court was said to have been at just such a capital. His final battle was fought around AD 520, the very time Arthur seems to have fought his final battle, and the most likely location for this conflict was right where the oldest reference to provide an exact location for Arthur’s last battle was set. Owain was doing the same things as Arthur, at the same time, and in the same place! Who else could he be but the King Arthur of legend? Now that I had discovered where this historical King Arthur ultimately fell, I was ready to tackle the crucial question. Where was he laid to rest?

In the Arthurian tradition the battle of Camlann ended in a kind of stalemate that weakened the entire nation to the advantage of the Anglo-Saxons. Historically, exactly the same occurred following the demise of Owain Ddantgwyn at the winding River Camlad, a name that could easily have derived from Camlann, “Crooked Bank.” If his final battle had been fought in some remote location, then Owain could have been buried anywhere nearby. But it wasn’t. It occurred in his own kingdom, just a few miles from his capital. If the battle resulted in an outright victory for his enemy, and they accordingly conquered his realm, then his body might either have been left to rot or interred by survivors as quickly as possible somewhere in the immediate vicinity. But it wasn’t. The forces on both sides were critically diminished during the encounter; Maglocunus retreated to Gwynedd, while Owain’s son Cuneglasus succeeded to the throne of Powys and his kingdom remained intact. Accordingly, Owain would almost certainly have been laid to rest at the customary burial site for the Powys royal family. But where was that?

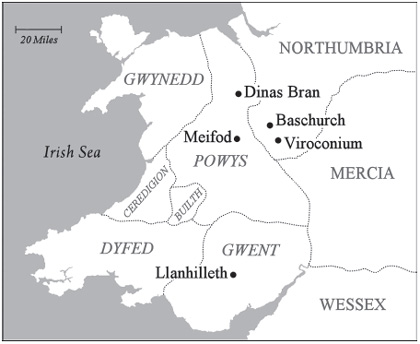

There was no doubt where the kings of Powys were interred a century and a half later. After the defeat of Powys at the hands of the Northumbrian king Oswy in the mid-600s, the Britons of the region where impelled to retreat into the western part of their kingdom, to the safety of the Welsh mountains. Their new capital was at Dinas Bran in Llangollen (see chapter 6), and the Powys kings were buried at the royal mausoleum in what is now Saint Tysilio’s Church at Meifod in the Vyrnwy Valley, twenty miles to the south. When I was researching in the 1990s, the whereabouts of their original burial site was still a mystery. Owain, I guessed, might have been buried at Viroconium, but this seemed unlikely. Following an original Roman custom, the Britons of the period considered it inappropriate to bury their honored dead within town walls. In fact, in Britain the Celtic people tended to bury the privileged classes at remote, sacred locations, some distance from major settlements. The later mausoleum at Meifod, for instance, was in an isolated vale, some twenty miles from the contemporary capital. The Powys dynasty of 150 years earlier was probably buried where the chieftains of the region had been interred for centuries. Find that, and it would be odds-on that I had found the last resting place of the man who was Arthur. However, it was not only problematic that nothing from the Roman or post-Roman era specifically recorded its location, but the grave of no British ruler from the late fifth and early sixth century had ever been discovered. So I faced yet another big challenge.

To start with I needed to determine the British funerary practices of the early 500s. By the end of the seventh century, Catholicism was reasserting its influence in Britain, but during the period around AD 500, the religion of the native Britons was a kind of hybrid pagan-Christianity. At best, there was a somewhat blurred dividing line between Christianity and paganism (see chapter 4). Although many people were nominally Christian—believing in Christ and the Bible—religious convention still involved what we might today consider pagan customs. The old sacred sites were still revered, although churches and chapels were erected over earlier shrines; funerary rites still involved such things as votive offerings; and people were buried with their belongings, known as grave goods. Astonishingly, many pagan traditions can still be found interpolated in modern Christianity: holly, ivy, and Christmas trees were all druidic adornments for the midwinter solstice, and painted eggs at Easter were sacred to the goddess Eostre—indeed the festival is actually named after her. During the post-Roman era pagan deities and demigods continued to be venerated but were usually transmogrified into biblical figures or characters from early Christian mythology. For example, Bran became Saint Bron, Jesus’s uncle; Macha became Saint Mary, Jesus’s mother; and Anann became Saint Anne, Jesus’s grandmother. As noted in chapter 5, the type of burial site from the period that I hoped to find was in all probability an island in a sacred lake—perhaps an island that had once had a Celtic church or more than one church upon it, such as the two chapels on Station Island and the Isle of Maree (see chapter 4). The problem was that there were a number of such potential lake islands in ancient Powys.

There did, however, survive a Dark Age war poem that might help narrow down the search. Remarkably, two people who had been members of the royal court at Viroconium during the mid-seventh century had endured to write about its final days. One of them was Llywarch, whom we met in chapter 11, and the other was the sister of King Cynddylan, whom we also met briefly in chapter 5. Princess Heledd (pronounced “Helleth”) fled eastern Powys when the kingdom was plundered by the Angle king Oswy in 658 and finally settled in the kingdom of Gwent, in what is now the village of Llanhilleth, named after her, four miles to the west of Pontypool in southeast Wales. Llanhilleth, meaning Saint Heledd, was so named because the princess was canonized after her death for founding a priory at the site where she was said to be buried. A church dedicated to Saint Illtyd now marks the spot (see plate 18). Not only a princess and a saint, Heledd also became a bard, and a number of poems were attributed to her. Heledd features in The Red Book of Hergest (see chapter 11) where she is referred to by the epithet hwyedic, Old Welsh for “hawk.”1 It would seem then that Hawk may have been her bardic title, as Merlin was the Eagle (see chapter 8). A particularly fascinating reference to the princess is found in the Welsh triad, the Three Unrestricted Guests of Arthur’s Court.2 Both Heledd and her contemporary bard Llywarch are named as two of these privileged guests. These historical figures lived a century and a half too late to have really been associated with King Arthur, but if Arthur was Owain Ddantgwyn, then the court at Viroconium—by Heledd’s time, the seat of her brother Cynddylan—would indeed have been what was once Arthur’s court. Perhaps this is what the triad implied.

One of the poems attributed to Heledd still survives in The Red Book of Hergest. Called the Canu Heledd (Song of Heledd) in its present form, it dates from the ninth century, but many linguists consider it to have been copied from an original dating to the mid-to-late 600s.3 Written in the first person, it concerns Heledd grieving the death of her brother the king and most of her family, the destruction of the court, and the devastation of her homeland by the Anglo-Saxons. As the Song of Heledd recounts the death of King Cynddylan and his brothers, I decided to visit the Bodleian Library and read through an English translation in the hope of finding some mention of the burial site of the Powys royal family. (At the time there were no published English versions readily available.) I was completely astonished to find that the poem not only referred to the burial site but actually named it. I realized that it was most unlikely that any scholar would have read the poem in an attempt to discover King Arthur’s grave, but was shocked that no one seemed to have appreciated that it provided the location of such an important Dark Age cemetery. If they had, then nothing was done about it.

Fig. 13.1. Western Britain around AD 660, after the Northumbrians had invaded eastern Powys.

As we saw in chapter 11, according to the Welsh Annals the Powys king Cynddylan died in 657, but it was not until the following year that “Oswy came and took plunder.”4 It was after this assault on eastern Powys that the Song of Heledd was set. Mourning the loss of Cynddylan and other members of her family, Heledd recounted how the capital and its court, the Hall of Cynddylan, were deserted, and other settlements lay in ruins. After describing the desolation, she talked about a desecrated compound called Eglwyseu Bassa,5 which seemed to have been a particularly sacred location as it was described by the Old Welsh breint,6 which in modern Welsh is fraint, meaning “a person, place, or thing of special status or privilege.” Eglwyseu Bassa, the poet explained, was where the king lay buried. In Old Welsh the poem described Eglwyseu Bassa as Cynddylan’s orffowys,7 now the modern Welsh gorffwys, meaning “resting place,” and went on to call it his diwed ymgynnwys.8 In modern Welsh diwedd means “final” and ymgynnwys means “place of containment.” In other words, Eglwyseu Bassa was the site of Cynddylan’s final resting place and his grave. I could be left with little doubt regarding this translation, as the location is also described as being tir mablan Cynddylan wyn,9 Old Welsh meaning literally “place of the little land of fair Cynddylan.” Mablan (little land) was the term used for a “grave plot.” The poem also related that the king’s siblings were buried there: Eglwysau Bassa ynt yng heno, etivedd Cyndrwyn (“Eglwysau Bassa affords space tonight to the progeny [children] of Cyndrwyn [Cynddylan’s father]”).10

It would seem, therefore, that the family burial site of the Powys dynasty was originally at Eglwysau Bassa. But where exactly was that? The word bassa, I learned, was unknown in Brythonic, Old Welsh, or modern Welsh, so the experts I spoke to at Oxford University thought that it was probably a personal name. In Old Welsh eglwyseu meant “churches”—plural—and as Bassa seemed to have been someone’s name, Eglwyseu Bassa must have meant “Bassa’s Churches” or “Churches of Bassa.” So it was evidently a place with more than one church, but exactly who was Bassa?

There are around a dozen places in Britain now bearing the prefix bas; most of them are listed by the Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names as being named after someone called Bassa.11 The authors of most books, and today’s websites, usually suppose this Bassa to have been an Anglo-Saxon chieftain. Quite where this idea originated is far from clear. Personally, I have failed to find contemporary reference to any Anglo-Saxon with that name. There are only two with some similarity. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records a priest called Bass who built a church in the village of Reculver in Kent in the year 669,12 while Bede records a soldier called Bassus in the army of King Edwin of Northumbria in 633;13 neither of them were of any great significance. The town of Basingstoke and the nearby village of Old Basing in the southern county of Hampshire go further than the other “Bas” locations in boasting their founder to have been a specific Bassa: a Saxon leader who settled the area around AD 700. In fact, it is claimed that his tribe, the Basingas, were named after him. However, both these assertions are highly suspect. Although the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does mention a battle at Basing (probably Old Basing) in 871, there is no historical reference as to how the place got its name and nothing whatsoever about a tribe called the Basingas—let alone a man called Bassa. All references I uncovered regarding this tribe and its supposed founder can be traced back to an entry in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names by the Swedish author Eilert Ekwall, published in 1940.14 My conclusion: If the bas prefix in British place names did originate with someone called Bassa, then whomever this was he was clearly not an Anglo-Saxon important enough to have been recorded. The name Bassa did exist, however. It was actually a Roman name—and a female one at that. Bassus was a relatively common man’s name, and Bassa was the feminine equivalent, like Julius and Julia. Famous Roman women bearing the name include Rubellia Bassa, a member of the imperial family in the first century; Julia Quadratilla Bassa, the daughter of Julius Quadratus Bassus, a consul in the second century; and a wealthy aristocratic lady known simply as Bassa, who became a leading Christian in Jerusalem in the mid-fifth century.

The British places bearing the prefix bas are found all over the country: for example, Baslow (Bassa’s Mound) in the county of Derbyshire, Bassingbourn (Bassa’s Stream) in Cambridgeshire, Bassingfield (Bassa’s Field) in Nottinghamshire, and Bassingham (Bassa’s Village) in Lincolnshire. These locations, which were all occupied during the Roman and post-Roman eras, are distributed right across Britain, so they were clearly not named after some local hero. More likely, they were named in honor of a woman of national importance. It seemed to me that, as no historical figures were known to have borne that name in post-Roman Britain, the character in question was probably a goddess. Interestingly, Nennius includes a location called Bassas as the site of one of Arthur’s battles. His Latin, Sextum bellum super flumen quod vocatur Bassas, translates directly as: “The sixth battle was over the river which is called Bassas.”15 Today there is no river bearing this name, and the battle site remains unidentified, but it does show that when Nennius wrote during the early 800s, there was a river that seems to have been sacred to a goddess, or a revered woman, called Bassa. (As apostrophes were not used until the sixteenth century, Bassas means Bassa’s—as in, belonging to Bassa.)

We examined in chapter 5 how the Brythonic language formed from a combination of Celtic and Latin, and that many Roman designations were adopted for native British deities, such as Minerva. Bassa, therefore, may well have been the name assumed for a goddess, later a saint, of the Britons. The place name suffixes such as ham and bourn, mentioned above, were indeed Anglo-Saxon words for “village” and “stream,” but as the Anglo-Saxons became Christians in the seventh century, and if Bassa was considered a saint, there would be no need for them to erase her name from the locations they renamed. They simply changed the Welsh words for village and stream—pentref and nant—for the Old English equivalents, but kept the name of the saint. Accordingly, Eglwyseu Bassa probably meant “Churches of the Goddess Bassa,” or by Christian times, as there were churches at the site and gods often became saints, the “Churches of Saint Bassa.”

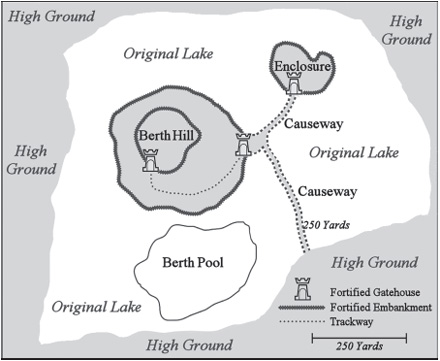

No place in Britain is still called Eglwyseu Bassa or the Churches of Bassa today, but was there anywhere in what had been the kingdom of Powys that might once have borne that name? Indeed there was: a village called Baschurch, around twelve miles northwest of Viroconium. Now in the English county of Shropshire, it stands in scenic countryside and has a population of around fifteen hundred. It has been called Baschurch as far back as surviving records go, which is almost a thousand years. When I first visited the place in the 1990s, local historians did consider it to have been the location mentioned in the Song of Heledd; specifically, that the original Eglwyseu Bassa was an ancient earthwork on the edge of the modern village. Standing on a plain of marshy land, it was comprised of a small hill covering some four and a half acres, surrounded by two artificial circular embankments, together with an oval area of raised ground, around an acre in size, 130 yards to the northeast, also surrounded by a man-made earthen rampart. The two earthworks were connected by a linear causeway, and a further 260yard causeway linked the hill to rising ground to the south. Today much of the low-lying area around the complex has been drained for farming, but in earlier times, when water levels were considerably higher, the two enclosures were islands surrounded entirely by water. The causeways therefore linked the islands together and the larger island to the surrounding land. Today the hillock is called Berth Hill, and the oval acre is known locally as the Enclosure; both features, together with the causeways, are collectively called The Berth (see plate 19). So during the Dark Ages, The Berth consisted of a pair of connected islands in the middle of a lake about half a mile long and wide. Part of this original lake, now called Berth Pool, still survives to the immediate south of the hill, much of the rest is pastureland used for the grazing of livestock. The word berth comes from the Anglo-Saxon word burh, meaning “fort,” which would appear to have been the name applied to it by the Angle Mercians who used it as a fortification in the later Dark Ages. Its original name is unrecorded, so it is reliably considered to have been the site that the Song of Heledd refers to as Eglwyseu Bassa—the Churches of Bassa. (Today Baschurch is the name for the village and its surrounding district, which includes The Berth.) Although local historians did regard The Berth as the site of Eglwyseu Bassa named in the Song of Heledd, no one I interviewed seemed to have realized the significance of the poem concerning the location’s status as the burial site of the kings of Powys.

I returned to the Rowley’s House Museum in nearby Shrewsbury to again question its curator Mike Stokes. What was known about the site? The earliest official survey of The Berth was conducted by the Shropshire Archaeological Society in 1937, which concluded that because of its low-lying position it was unlikely to have been constructed as a primary fortification, although its ramparts did suggest a limited defensive purpose. It was certainly no hill fort and was too small to have been a fortified settlement. The expert’s conclusion, Stokes explained, was that it served as some form of ceremonial compound. The only archaeological excavations of the site were carried out in 1962 to 1963 by archaeologist Peter Gelling of Birmingham University. They were, however, severely limited due to a lack of funding. Basically just a trial dig, it did unearth evidence, such as pottery fragments, to determine that the earthworks had been constructed in pre-Roman times but that the complex was still in use, or certainly being reused, during the post-Roman era. The general consensus was that the embankments circling each of the islands would have supported timber stockades, surrounding buildings constructed for religious purposes. So it did indeed seem to have been a ritual center where high-status figures might well have been buried, just as the Song of Heledd implied.

So my research had led me to the following conclusions: the historical Arthur was Owain Ddantgwyn; Owain was a king of Powys; and the kings of Powys seem to have been buried at The Berth. From the dating of occupation, this site would almost certainly have been where the kingdom’s royal family had been interred as far back as the early sixth century, if not earlier. I had found a viable last resting place for King Arthur. But this left me with a seemingly insurmountable dilemma. The Berth might contain dozens of burials! How on earth would it be possible to identify which of them was the grave of Owain Ddantgwyn?

Before continuing I needed to further collate what I had learned about early Dark Age funerary practices. Until the late twentieth century, historians tended to assume that during the post-Roman period pagan burials included grave goods, such as jewelry, weapons, and pottery, whereas Christian burials did not. These days, archaeology has proved such assumptions to be far too simplistic. There was in fact a considerable overlap from late Roman times, right through until the eighth century.16 The Christian prohibition of grave goods did not become widespread until the later Dark Ages. In fact, as we have seen in Britain of the fifth and sixth centuries, the dividing line between Christian and pagan was anything but clearly defined. High-status individuals tended to be interred, rather than cremated, and were usually buried in a circular pit, dug to a depth of around six feet. Some had personal belongings buried with them, which, in the case of warriors, would often include weapons.17 As noted in chapter 4, the warrior’s sword would often be cast into a river, lake, or pool, either as a votive tribute to a water deity if he were pagan or an offering to an equivalent saint. Consequently, another weapon might be buried with him, such as his shield. So at least I knew what to look for, but once again, this was of no help in specifically locating Owain’s grave.

I decided that the next thing was to archaeologically verify that The Berth really had been used as the burial site of the Powys kings. The land was privately owned, in fact, by three separate farms, but it was also a listed monument. That meant that for any archaeological work to be approved, I would not only need the permission from the landowners but from English Heritage. English Heritage is an executive department of the British government whose purpose is to protect and preserve structures and sites of historical interest. The Berth was known to have been an ancient site worthy of preservation. So to prevent it from being damaged by digging, building, or other invasive activity, English Heritage had instituted a preservation order. This meant that it was illegal, even for the landowners, to excavate the area without government permission. In order to secure such agreement, those involved in any such work would have to be professional archaeologists. Even then, there would need to be extensive evidence to justify an excavation. Luckily, by this time there was a way to survey The Berth without disturbing the site: a scientific procedure called geophysics that employs sophisticated electronic equipment to determine what lies beneath the earth without the need for intrusive digging. However, geophysics surveys don’t come cheap. Apart from the fact that much of Berth Hill was covered with trees, thick brambles, and undergrowth that would need to be cleared, to survey the entire complex would take weeks. Way beyond any budget that I could hope to raise. If I was to get any esteemed archaeologists involved, I would have to come up with a practicable and precise area of The Berth to be surveyed. And an idea occurred to me.

I might have no way of knowing specifically where Owain was buried, but there was evidence for the location of Cynddylan’s grave. The Song of Heledd had revealed that Cynddylan was buried at the Churches of Bassa, though not exactly where. But another poem did. This was in Llywarch’s Marwnad Cynddylan (Elegy of Cynddylan), the same work that referred to Cynddylan and his brothers as Arthur’s heirs (see chapter 11). Although the Elegy of Cynddylan is attributed to the court bard Llywarch, the poem concerns Princess Heledd mourning the death of Cynddylan as she attends his grave. In Llywarch’s transcription of what was evidently her funerary dirge, many verses begin with a line that translates as “I shall lament [the death of Cynddylan] until I lie [in my grave].”18 Heledd expects to eventually lie at peace with her brother, but, as we have seen, this never came to pass as she was forced to flee into Wales and was ultimately laid to rest in Llanhilleth. The poet describes how Heledd hopes to be buried in the same place and in the same manner as the dead king; she will lament for Cynddylan until she too is interred in a fashion Llywarch describes with the Old Welsh words derwin and fedd.19 The first word, derwin, in modern Welsh is derwen, meaning “oak,” and the second word, fedd, is rendered bedd (pronounced “beth”), in modern Welsh, which means “grave.” This, in the English version I consulted at the Bodleian Library, had been translated as “oak coffin,” but most Welsh historians I consulted disagreed. In modern Welsh the word for coffin is arch, or would have been written erch or eirch in Old Welsh. The author, they told me, is specifically saying that the term is an oaken grave, and there’s a big difference. Archaeology has revealed that during the seventh century, the dead were usually interred in a circular pit, its earthen walls lined with wooden planks; in the case of high-status figures, they would often be made of oak. Heledd is saying that, like her brother, she too expects to be buried in a timber-lined pit, befitting her status.

The poet provides a further description of the grave as being in erw trafael,20 which had been translated as a “humble grave plot.” But, once again, this seemed to be wrong. The word trafael is a mystery, leading the translator to divide it into two words approximating the modern Welsh tra gwael, meaning literally “while poor,” hence the English translation as “humble.” Trafael, however, in the original text is a single word, leading other translators, such as Williams and Morris (see chapter 11), to interpret it as a proper noun—the name of a specific place. This would tally with the other term erw. It does not mean “grave plot” at all; in both Old and contemporary Welsh, it is the word for an acre of land (in modern terms, around the size of an American football field). Accordingly, erw trafael actually translates as “Trafael’s Acre,” probably named after a real or mythical figure once associated with the site. There was only one particular location at the Berth matching the description, the oval field—approximately an acre in size—now called the Enclosure. This smaller of the two islands readily lent itself to a geophysical survey. Within its ramparts the ground was dry and flat; it was a grassy pasture, free from trees, bushes, and complicating vegetation, and it was small enough to be surveyed within a reasonable time scale. It was a practical and hopefully affordable site for a geophysics team to examine.

In 1995 I finally managed to initiate the first archeological work undertaken at The Berth in over thirty years. Permission was obtained from the relevant landowners, and a team of specialists from Geophysical Surveys of Bradford were retained to conduct the work. These geophysicists were the world’s first group to use such technology to specialize exclusively in archaeology. The project was overseen by the eminent archaeologist Dr. Roger White of Birmingham University and was financed by a British production company that wanted to film the enterprise. I must stress that these experts had no particular stance concerning my theories about King Arthur, nor did they regard him as having any association with The Berth. What interested them was that this was a site of considerable historical interest, and they were keen to learn more about it. With a limited budget the geophysics was to last for just one day, but fortunately this was enough time to fully survey the so-called Enclosure. The geophysics team used three types of equipment: first, a proton magnetometer that measured any magnetic anomalies beneath the surface, revealing the presence of objects made of iron; second, a resistivity meter—a double-pronged device that sent an electric current through the ground to measure changes in resistance—that could detect different types of materials beneath the surface, such as stones, bricks, and foundation walls; and finally, a ground-penetrating radar scanner that could produce a computer-generated image of what lay deep below the ground.

Fig. 13.2. The Berth at Baschurch in Shropshire, showing the original lake and basic fortifications of the post-Roman era.

The results were certainly fascinating. It seems that two wooden buildings had once stood on the site, plus a larger stone structure. Their precise date and purpose were impossible to determine with certainty without digging, but the wooden buildings were probably earlier constructions, while the stone structure might have been a later ecclesiastical shrine: perhaps one of the chapels implied in the name of the site, the Churches of Bassa. The most significant discovery was located right in the middle of the Enclosure. It was a single circular pit, some six feet deep, consistent with a burial ditch of the post-Roman era. Although the technical restraints of the equipment made it impossible to reveal the presence of aged and fragile bones at that depth, it was able to detect metal, and right in the center of the ditch, there was a diamond-shaped piece of metal about six inches wide, possibly the central boss of an ancient shield. This was both exhilarating and unexpected. If this was an ancient burial, then—if I had interpreted the Elegy of Cynddylan correctly—it had to be the grave of Cynddylan; it was within this Enclosure that he had evidently been laid to rest. But, surprisingly, there was no evidence of any other graves from the comprehensive survey of this entire compound. Where were the graves of the other members of the Powys royal family mentioned in the Song of Heledd? And more importantly, where was the grave of Owain Ddantgwyn?

Perhaps, because The Berth was being hastily abandoned by the Britons retreating from the Anglo-Saxons, Cynddylan, the last Powys king to rule the region, was laid to rest in a part of the site previously used for purposes other than burials. The other members of the royal family, and hopefully his ancestors, must have been buried on the larger of the two islands, now Berth Hill. Nonetheless, the survey certainly seemed to have proved the accuracy of the Song of Heledd and the Elegy of Cynddylan. Not only myself but members of the archaeological team were optimistic about a further survey being conducted on the larger of the two islands. However, the sheer amount of work that would be necessary to clear the area was financially prohibitive. It was to be sixteen years before I got another shot at finding the grave of the man I believed to have been King Arthur.

In 2011 I was approached by a production company working for the National Geographic Channel. They were interested in making a documentary involving my search for King Arthur and, astonished that no further archaeological work had been done at The Berth since the mid1990s, offered to finance another geophysics survey. If further evidence justified it, then they would consider paying for a proper excavation. It might seem strange that, despite the fact that there was already evidence for a burial in the Enclosure, and the possibility that it was the grave of a Dark Age king, no dig had been conducted. The problem was that funds for archaeological excavations are extremely limited, and there are many sites and many archaeologists competing for what little there is. Those who controlled the purse strings, for whatever reason, evidently did not consider The Berth worthy of consideration. But now there was an offer of such finance. Dr. Roger White, who had overseen the original survey, was contacted and was again keen to be involved. Regardless of his personal views concerning King Arthur or the original function of The Berth, he was enthusiastic to see a professional investigation conducted at a site of historic interest.

I wanted the survey to concentrate on the larger of the islands, on and around Berth Hill, but once again, due to limited time for the investigation to be completed, this was impractical. It was decided that there should be another geophysics survey of the Enclosure. Sixteen years had meant significant advances in technology, so although the equipment now to be used was basically the same as the first survey, it was far more sophisticated. Giant leaps had also been made in computer power, meaning that processing would produce far superior results and researchers would be able to indentify features undetectable in the mid-1990s. The results confirmed the initial scans. Near the middle of the Enclosure, there was the circular ditch, which White was certain had not been a house or any other similar structure and was likely to have been a burial. As the geophysics confirmed that there were no other similar readings on the plot, it would appear to be an isolated grave, and therefore probably someone of importance. The iron object was again detected at the center of the ditch, which White suggested might be an axe, a sword, or a shield. It was to some extent disappointing that no further graves were discovered, but on the positive side the anomaly—the geophysics term for something different from what is around it—warranted a limited archaeological dig of that specific location. If it proved to be the grave of a high-status individual dating from Cynddylan’s time, then it would justify a further geophysics survey of Berth Hill itself and hopefully a wider excavation of the ancient complex.

Sadly, at the time of writing, nothing more has been done. Another archaeologist who subsequently examined the results from the survey thought that the ditch might in fact have been a furnace, and this probably gave those with the financial clout to organize further exploration the excuse to hang on to such resources in times of severe fiscal restraint. However, as far as I was concerned, this was a pretty weak argument. Smelting iron results in a significant amount of slag—lumps of stony, waste matter separated from the ore during the smelting process. The ground-penetrating radar was sensitive enough to detect such deposits of slag in the pit or surrounding area—and evidence of none whatsoever was found. Nevertheless, a second and more ambitious project was funded by the National Geographic Channel to examine Berth Pool.

In chapter 4 we saw how prized possessions were thrown into lakes by the Britons as offerings to a water goddess and that the custom continued during the post-Roman era—even by Christians—though in their case as tributes to an equivalent female saint. The theme of Excalibur being cast to the Lady of the Lake might well have originated with this tradition, possibly as part of a funeral rite. Maybe, I suggested, the historical Arthur’s sword could have been thrown into the lake surrounding The Berth complex. As part of this lake still survived as Berth Pool, an elaborate exploration was initiated to examine the lake floor. The team, led by forensic marine archaeologist Ruth McDonald from Liverpool University, included both surface technicians with specialist equipment in a boat and underwater divers. One of the first questions McDonald asked me was what precisely she was looking for, and I was able to show her what we were hoping to find. I had asked one of Britain’s leading authorities on armaments of the early Dark Ages, British post-Roman military expert Dan Shadrake, to make an illustration of a chieftain’s sword of around AD 500. It turned out that they were not the long medieval swords as Excalibur is usually depicted but two-foot, Roman-style cavalry swords with stunted cross-guards. As The Dream of Rhonabwy had actually described Arthur’s sword as having the design of two serpents on its golden hilt (see chapter 9), Shadrake incorporated a double-serpent motif in the style of the period on the sword’s hilt in his drawing. Based on Shadrake’s artist’s impression, a replica was made by the company that still forged ceremonial swords for the British military. They crafted a stunning recreation of a historical “Excalibur” in gold and shining steel. Although perhaps in nowhere near as good condition, it was possible that the mud of the lake bed would have preserved such an artifact. McDonald began by crisscrossing the lake in a boat outfitted with an impressive array of scientific equipment. Sonar was used, so was radar, while a deep-penetrating magnetometer scanned for metal well beneath the layer of lake-bottom sediment. Although the results revealed that there were dozens of metal objects down there, many of which could have been ancient swords or other votive offerings, it was hardly helpful. Which anomalies were the underwater team to investigate? The divers were deployed and spent an entire day searching the locations where the most promising objects were located, but it all ended in frustration. Underwater archaeology is difficult in the best of conditions, but the water of Berth Pool was prohibitively murky, and a four-foot layer of glutinous sediment lay on top of the harder bed mud below. It was out of the question to even consider an excavation.

All may not be lost in a search for a historical King Arthur’s sword, however. Far from it! Berth Pool was only a fraction the size of the original lake. The sword—and many other ancient votive offerings—might lie in the excavatable, now dry land surrounding the Berth. Indeed, just such an artifact was discovered there in 1906 by a workman cutting turf at the edge of a stream close to the causeway that once joined the larger island to the mainland. It was a bronze cauldron, around eighteen inches high and twelve inches wide. Dating from the Roman period, it is now in the British Museum where it is believed to have been cast into the lake as a votive offering during the first century AD. This had been a chance discovery, but a proper geophysics survey could well reveal many such artifacts in the area of the original lake that has never been excavated.

Someone once said that extraordinary claims required extraordinary evidence, and claiming to have discovered a real King Arthur was certainly an extraordinary claim. Nevertheless, I had extensive evidence that Owain Ddantgwyn was the historical King Arthur, and I also had significant evidence for The Berth being Owain’s burial site. What I didn’t have was a precise location for his grave. Like the Avalon of legend, The Berth was an ancient island sanctuary; a sacred site used by the Celtic Britons for centuries. Isolated, silent, and eerie, often rising above early morning mist, it could hardly be a more appropriate setting for the last resting place of the man who was Arthur. But where on The Berth was he actually buried? Perhaps I could find clues as to where King Arthur was thought to have been laid to rest in the various medieval and earlier Welsh Arthurian traditions.

The initiator of the medieval Arthurian romances, Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 1130s, failed to say exactly where Arthur was buried. In his History of the Kings of Britain, he wrote that “King Arthur himself received a deadly wound, and was borne unto the island of Avalon for the healing of his injuries.”21 Geoffrey said absolutely nothing of his death or burial. In his Life of Merlin, written around the same time, he added a little more detail, saying that after the battle of Camlann, the wounded Arthur was taken to Avalon, “where Morgan received him with honor, and placed him in her chamber . . . and with her own hand she uncovered his wound. . . . At length, she said that his health might be restored by her healing art if she stayed with him a long time.”22 Once more, we are not told whether Morgan successfully healed Arthur or if he died, let alone where he was buried. The Jersey author Wace, writing about twenty years later in his Romance of Brutus, claimed, like Geoffrey, that he took his information from an earlier British chronicle. It was presumably a different chronicle, as Wace suggests that Arthur actually died on the battlefield—“wounded in his body to the death”—and was taken to Avalon in the hope of resurrection. The Britons (i.e., the Welsh), he adds, believed that he still lies there, awaiting the day of his rebirth.23 Although Geoffrey was the author to popularize the Arthurian story to a medieval readership, he was by no means the first to write about the fabled king. A decade before Geoffrey’s works, the respected historian William of Malmesbury, in his Deeds of the English Kings of 1125, stated that he believed Arthur to have been a historical figure, although the whereabouts of his tomb was unknown. He too talks about the legend that Arthur would one day live again, possibly the notion that one of his descendants would eventually retake the British throne.24 Most of the earliest surviving works that refer to Arthur’s grave either state directly or imply it to have been on the Isle of Avalon, but the location of that island seems to have been lost in the mists of time. Even as early as the ninth century, it would appear that the whereabouts of Avalon and Arthur’s last resting place had been forgotten. An Old Welsh poem, Englynion y Beddau (The Stanzas of the Graves)—now preserved in The Black Book of Carmarthen (see chapter 8) and on linguistic grounds thought to date from the 800s—said that the location of Arthur’s grave was a mystery to all.25

The oldest work I could discover to provide any specific details concerning Arthur’s last resting place was in one of the Vulgate stories (see chapter 3), titled La Mort le Roi Artu (The Death of King Arthur), dating from around 1230.26 Its anonymous author also claims to have consulted an ancient British source that maintained Arthur died in Avalon and was buried there, specifically, “within the black chapel.” If the historical Avalon was The Berth and, of course, if the Vulgate author is right, then Arthur might have been buried in a chapel that was one of the original Churches of Bassa. The work even describes the burial site as a tomb rather than a simple grave: “On the marvelous and rich tomb there was writing, saying: ‘Here lies King Arthur, who by his valor subjugated twelve kingdoms.’” Presumably the epitaph referred to the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons and might relate to the twelve decisive battles recorded by Nennius. The same theme was later taken up by Thomas Malory, writing in the mid-1400s, who also refers to Arthur’s tomb in a chapel, although, due to the popularity of Arthur’s supposed grave at Glastonbury, he suggests the site to be somewhere in that vicinity.27 Malory’s The Death of Arthur is an amalgamation of earlier Arthurian works, so the chapel reference probably came from the Vulgate tale, but he evidently employed a further, now lost source as he includes a different epitaph written in Latin:

HIC IACET ARTHURUS REX QUONDAM REX QUE FUTURES

[Here Lies King Arthur, the Once and Future King]

Just how seriously we can take the claims that Arthur was buried in a chapel on Avalon and that there was some kind of decorative sepulcher with an inscription is open to question. These are late references, but it’s all there is to go on. There almost certainly were chapels at the Churches of Bassa, or The Berth would not have been called by that name in the seventh century. What may have been the foundation stones of one of these churches seems to have been detected during the geophysics scan in 1995. As the place name included the plural “churches,” we can assume that there had to be at least one other, and as both geophysics surveys revealed no second stone structure on the smaller island at The Berth, then there was probably a further church on the larger island, now Berth Hill. As dwellings, fortifications, and other practical structures were generally built from wood during the post-Roman period, stonework was reserved almost exclusively for churches. So, if the Vulgate author really did employ some earlier, Welsh source—possibly a war poem similar to the Song of Heledd—in composing La Mort le Roi Artu, then my suggestion for a further geophysics survey would be to scan for a stone structure on Berth Hill. If one is found and there is also evidence of a burial there, then perhaps I will finally have found the historical King Arthur. Surely that would persuade English Heritage to permit an excavation! And if such a dig is initiated, then there might, just possibly (and I sincerely hope), be an inscription to fully validate my theory.

However, as I said earlier, Berth Hill would be a difficult place for geophysics. It is partly wooded and covered with undergrowth. If the opportunity does arise for a further survey, then I would have to suggest a specific part of the hill to scan. Fortunately, I discovered one possible location suggested to me by Mike Stokes of the Shrewsbury museum. He directed me to an observation made by an archaeologist in 1925, when there was far less vegetation obscuring the land. Examining the area, Lily Chitty, at the time the local secretary for the Royal Archaeological Society in Shropshire, noticed a raised plot of land on the hill that, she learned from a local schoolteacher, was said to be the burial site of a royal warrior who had been interred there after a fatal battle. This was obviously just a local legend that still existed at the time, but folklore can sometimes lead to real archaeological discoveries. For instance, on Cornwall’s Bodmin Moor there is an ancient mound called Rillaton Barrow, where local tradition long held that a druid once lived there who possessed a miraculous golden goblet that never ran dry. When the mound was excavated in the nineteenth century, a stone-lined vault was unearthed, containing a human skeleton buried with a ceremonial cup made from pure gold. Now in the British Museum, the artifact has been dated to around 1500 BC. Another example concerns folklore regarding a mound known as Bryn-yr-Ellyllon (Goblin’s Hill) near the town of Mold in North Wales. Legend told of a small figure wearing a golden coat that was said to haunt the location, hence its name. When the site was excavated in 1833, a stone burial chamber was discovered containing a skeleton buried in a solid gold half-tunic. Now known as the Mold Cape, the item is thought to have been worn around the shoulders, chest, and upper arms of someone of authority during religious rites—presumably the person who was buried there. Made from 23-carat gold, and weighing over two pounds, it is around four thousand years old and is considered one of the finest Bronze Age artifacts in the world. These are just two of many similar instances where local folklore appears to have retained the ancient memory of a real, historical burial of an important individual. Perhaps the same is true of the legend Lily Chitty recounted concerning The Berth.

From Mike Stokes, I learned the precise location of this area of land but have deliberately withheld that information to avoid any irresponsible attempts to dig there. Besides which, any burial would be far too deep for amateur equipment, such as metal detectors. Only a professional geophysics survey, conducted by experts, would have any success in discovering what lies beneath that spot. All of The Berth is on private land, so even a visit to the location requires permission from the relevant landowners. There are stringent laws about metal detecting or digging on private land in the UK. Both are illegal without prior permission from the owner. Concerning The Berth, as it is a scheduled archaeological site, metal detecting or excavation of any kind is entirely forbidden under all circumstances without consent from the Secretary of State for Culture, Media, and Sport. Under British law, illegal digging on a scheduled ancient monument carries a penalty of two years’ imprisonment or an unlimited fine.

At the start of this book, I said that I had set out to discover the whereabouts of King Arthur’s grave, and I believe I have succeeded in doing just that. In my opinion he is buried at The Berth in the country of Shropshire, in pretty much the center of Britain. I have a good idea about the precise spot and earnestly hope that a new geophysics survey will soon be conducted there; and after that, if all goes well, there will be an archaeological excavation. Perhaps then, Arthur may not return from the dead as the Dark Age Britons once believed, but he will finally be accepted by scholars throughout the world as an authentic British king.