IN SEARCHING FOR the first screwdriver I have become interested in screws. When Agricola compared the screw to the nail as a way of constructing bellows, he observed that “there is no doubt that it [the screw] surpasses it in excellence.”1 In fact, the wrought-iron nail is a remarkable fastener. It bears little resemblance to the modern steel nail. The modern nail is round and pointed and forces itself between the wood fibers. Such nails are reasonably effective when driven into softwood (spruce, pine, fir), but will usually split hardwood (maple, birch, oak). Moreover, even in softwood the holding power of a round nail is weak, since it is kept in place only by the pressure of the fibers along two sides. The wrought-iron nail, on the other hand, is square or rectangular in cross-section with a hand-filed chisel point. The chisel point, driven across the grain, cuts through the wood fibers rather than forcing its way between them, just like a modern railroad spike. Such nails can be driven into the hardest wood without splitting it, and they are almost impossible to remove, as I discovered when I nailed a replica wrought-iron ship’s nail into a board as an experiment.I

Wrought-iron nails have limitations, however. If they are driven into a thin piece of wood, such as a door, their holding power is greatly reduced and their protruding ends must be clenched—bent over—to keep them fast. Wrought-iron nails are most effective—and easier to fabricate—when they are relatively large (at least an inch or two long). That is why the earliest screws replaced nails in small-scale applications such as fixing leather to a bellows board, or attaching a matchlock to a gunstock. Even a short screw has great holding power. Unlike a nail or a spike, a screw is not held by friction but by a mechanical bond: the interpenetration of the sharp spiral thread and the wood fibers. This bond is so strong that a well-set screw can be removed only by destroying the surrounding wood.

The problem with screws in the sixteenth century was that, compared to nails, they were expensive. A blacksmith could turn out nails relatively quickly. Taking a red-hot rod of forged iron, he squared, drew, and tapered the rod to a point, pushed the reheated nail through a heading tool, then with a heavy hammer formed the head. The whole procedure, which had been invented by the Romans and was still used in the 1800s (Thomas Jefferson’s slaves produced nails this way at Monticello), took less than a minute, especially for an experienced “nailsmith.” Making a screw was more complicated. A blank was forged, pointed, and headed, much like a nail, but round instead of square. Then a slot was cut into the head with a hacksaw. Finally, the thread was laboriously filed by hand.

Gunsmiths manufactured their own screws, just as armorers made their own bolts and wing nuts. What about clockmakers? Turret clocks appeared in Europe as early as the fourteenth century. The oldest clock of which we have detailed knowledge was built by an Italian, Giovanni De’Dondi. It is an astronomical clock of extraordinary complexity. The seven faces show the position of the ancient planets: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn; in addition, one rotating dial indicates religious feast days, and another displays the number of daylight hours in the day. De’Dondi fashioned the bronze, brass, and copper parts by hand. It took him sixteen years to build the clock, which he finished in 1362. Although the original was destroyed by fire in the sixteenth century, the inventor left detailed instructions, and two working replicas were built in London in 1962. One of these now belongs to the National Museum of American History, and I catch up with it in Montreal, where it is part of a temporary exhibit. The exquisite seven-sided machine stands about four feet tall; the gearwheels are driven by suspended weights. I examine the mechanism. As far as I can see, all the connections are pegged mortises and tenons, a detail adapted from carpentry. The projecting tenons have slot-holes into which a wedge is driven. These wedges vary in size from tiny needlelike pins to one inch long. There must be several hundred such attachments, but I can’t see a single screw.

According to Britten’s Old Clocks and Watches and Their Makers, the standard work of horological history originally published in 1899, “screws were entirely unknown in clocks before 1550.”2 Their introduction was a result of the demand for smaller and lighter domestic clocks, especially watches. According to Britten’s, “Even the earliest watches generally possess at least one screw. These screws have dome-shaped heads and the slots are V-shaped. The thread is coarse and irregular.”3

—

By the mid-sixteenth century, applications for screws had grown to include miniature screws and bolts in watches, larger screws in guns, and heavy bolts in armor. Yet it was another two hundred years before demand grew enough that a screw industry developed. The Encyclopédie mentions that the region of Forez, near Lyon, specialized in screws, which were available in a variety of lengths—one-half inch to four or five inches. These screws were still so expensive that they were sold individually. According to the Encyclopédie, heads were either slotted or square.

In England, screw-making was concentrated in the Midlands. It was organized as a cottage industry. Forged-steel blanks with formed heads were made in large quantities by local blacksmiths and delivered to the so-called girder, who, with his family and an assistant or two, worked at home. The first step was to cut the slot, or “nick,” into the head with a hacksaw. That was the easy part. Next the thread, or “worm,” had to be filed by hand. Some girders used a spindle—a crude lathe—turning a crank with one hand and guiding a heavy cutter with the other, back and forth, back and forth. Whichever method was used, the work was slow and laborious, and since the worm was cut by eye, the result was a screw with imperfect, shallow threads. According to one contemporary observer, who had seen screw-girders at work, “The expensive and tedious character of these processes rendered it impossible for the screws to compete with nails, and consequently the sale was very small. The quality was also exceedingly bad, it being impossible to produce a well-cut thread by such means.”4

Both Moxon and the Encyclopédie mention that screws are used by locksmiths to fasten locks to doors. I also come across references to eighteenth-century carpenters using screws to attach hinges, particularly the novel garnet hinge. A garnet hinge resembles a |—, the vertical part being fastened to the doorjamb and the horizontal to the door. Garnet hinges, used with light cupboard doors and shutters, were screwed rather than nailed to the frame. Heavy doors, on the other hand, were hung on traditional strap hinges that extended the full width of the door and were nailed and clenched.

Strap and garnet hinges are still used today, but by far the most popular modern door hinge is the butt hinge, which is not mounted on the surface but mortised into the thick end—the butt—of the door. Butt hinges are aesthetically pleasing, being almost entirely hidden when the door is closed. They were used in France as early as the sixteenth century (butt hinges are illustrated by Ramelli), but were luxury objects, crafted by hand of brass or steel. In 1775, two Englishmen patented a design for mass-producing cast-iron butt hinges.5 Cast-iron butt hinges, cheaper than strap hinges, had one drawback: they could not be nailed. Nails worked themselves loose as the door was repeatedly opened and closed, and since the nails were in the butt of the door, they could not be clenched. Butt hinges had to be screwed.

By coincidence, at the very moment that butt hinges were being popularized, a technique for manufacturing good-quality, inexpensive screws was being perfected. Years earlier, Job and William Wyatt, two brothers from Staffordshire in the English Midlands, had set out to improve screw-making. In 1760, they patented a “method of cutting screws of iron commonly called wood-screws in a better manner than had been heretofore practiced.”6 Their method involved three separate operations. First, while the forged blank of wrought iron was held in a rotating spindle, the countersunk head was shaped with a file. Next, with the spindle stopped, a revolving saw-blade cut a slot into the head. Finally, the blank was placed in a second spindle and the thread was cut. This was the most original part of the process. Instead of being guided by hand, the cutter was connected to a pin that tracked a lead screw. In other words, the operation was automatic. Now, instead of taking several minutes, a girder could turn out a screw—a much better screw—in six or seven seconds.

It took the Wyatt brothers sixteen years to raise the capital required to convert a disused water corn-mill north of Birmingham into the world’s first screw factory. Then, for unexplained reasons, their enterprise failed. Maybe the brothers were poor businessmen, or maybe they were simply ahead of their time. A few years later, the factory’s new owners, capitalizing on the new demand for screws created by the popularity of butt hinges, turned screw manufacturing into a phenomenal success. Their thirty employees produced sixteen thousand screws a day.7

Machine-made screws were not simply produced more quickly, they were much better screws. Better and cheaper. In 1800, British screws cost less than tuppence a dozen. Eventually, steam power replaced waterpower in the screw factories, and a series of improvements further refined the manufacturing process. Over the next fifty years, the price dropped by almost half; in the following two decades, it dropped by half again. Inexpensive screws found a ready market. They proved useful not only for fastening butt hinges but for any application where pieces of thin wood needed to be firmly attached, which included boatbuilding, furniture-making, cabinetwork, and coachwork. Demand increased and production soared. British screw factories, which had annually produced less than one hundred thousand gross in 1800, sixty years later produced almost 7 million gross.8

—

Take a close look at a modern screw. It is a remarkable little object. The thread begins at a gimlet point, sharp as a pin. This point gently tapers into the body of the screw, whose core is cylindrical. At the top, the core tapers into a smooth shank, the thread running out to nothing. The running-out is important since an abrupt termination of the thread would weaken the screw.

The first factory-made screws were not like this at all. For one thing, although handmade screws were pointed, manufactured screws had blunt ends and were not self-starting—it was always necessary first to drill a lead hole. The problem lay in the manufacturing process. Blunt screws could not simply be filed to a point—the thread itself had to come to a point, too. But lathes were incapable of cutting a tapering thread. Screw manufacturers tried angling the cutters, which produced screws that tapered along their entire length. Such screws had poor holding power, however, and carpenters refused to use them. What was needed was a machine that could cut a continuous thread in the body of the screw (a cylinder) and also in the gimlet point (a cone).

An inventive American mechanic found the solution. The first American screw factories had been established in Rhode Island in 1810, using adapted English machines. Providence became the center of the American screw industry, which by the mid-1830s was experiencing a boom in demand for its products. Beginning in 1837, a series of patents addressed the problem of manufacturing gimlet-pointed screws, but it took more than a decade of trial and error to get it right. In 1842, Cullen Whipple, a mechanic from Providence who worked for the New England Screw Company, invented a method of manufacturing screws on a machine that was entirely automatic. Seven years later he made a breakthrough and successfully patented a method of producing pointed screws. A slightly different technique was devised by Thomas J. Sloan, whose patent became the mainstay of the giant American Screw Company. Another New Englander, Charles D. Rogers, solved the problem of tapering the threaded core into the smooth shank. Such advances put American screw manufacturers firmly in the lead, and by the turn of the century, when the screw had achieved its final form, American methods of production dominated the globe.

—

Ever since the fifteenth century, screws had had either square or octagonal heads, or slots. The former were turned by a wrench, the latter by a screwdriver. There is no mystery as to the origin of the slot. A square head had to be accurate to fit the wrench; a slot was a shape that could be roughly filed or cut by hand. Screws with slotted heads could also be countersunk so they would not protrude beyond the surface—which was necessary to attach butt hinges. Once countersunk screws came into common use in the early 1800s, slotted heads—and flat-bladed screwdrivers—became standard. So, even as screws were entirely made by machine, the traditional slot remained. Yet slotted screws have several drawbacks. It is easy to “cam out,” that is, to push the screwdriver out of the slot; the result is often damage to the material that is being fastened or injury to one’s fingers—or both. The slot offers a tenuous purchase on the screw, and it is not uncommon to strip the slot when trying to tighten a new screw or loosen an old one. Finally, there are awkward situations—balancing on a stepladder, for example, or working in confined quarters—when one has to drive the screw with one hand. This is almost impossible to do with a slotted screw. The screw wobbles, the screwdriver slips, the screw falls to the ground and rolls away, the handyman curses—not for the first time—the inventor of this maddening device.

American screw manufacturers were well aware of these shortcomings. Between 1860 and 1890, there was a flurry of patents for magnetic screwdrivers, screw-holding gadgets, slots that did not extend across the face of the screw, double slots, and a variety of square, triangular, and hexagonal sockets or recesses. The latter held the most promise. Replacing the slot by a socket held the screwdriver snugly and prevented cam-out. The difficulty—once more—lay in manufacturing. Screw heads are formed by mechanically stamping a cold steel rod; punching a socket sufficiently deep to hold the screwdriver tended to either weaken the screw or deform the head.

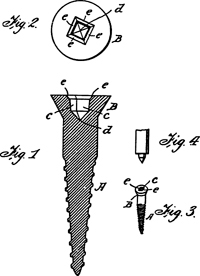

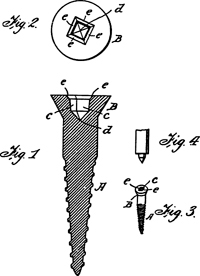

The solution was discovered by a twenty-seven-year-old Canadian, Peter L. Robertson. Robertson was a so-called high-pitch man for a Philadelphia tool company, a traveling salesman who plied his wares on street corners and at country fairs in eastern Canada. He spent his spare time in his workshop, dabbling in mechanical inventions. He invented and promoted “Robertson’s 20th Century Wrench-Brace,” a combination tool that could be used as a brace, a monkey wrench, a screwdriver, a bench vise, and a rivet maker. He vainly patented an improved corkscrew, a new type of cuff links, even a better mousetrap. Then, in 1907, he received a patent for a socket-head screw.

Peter L. Robertson’s 1907 patent for a socket-head screw.

Robertson later said that he got the idea for the socket head while demonstrating a spring-loaded screwdriver to a group of sidewalk gawkers in Montreal—the blade slipped out of the slot and injured his hand. The secret of his invention was the exact shape of the recess, which was square with chamfered edges, slightly tapering sides, and a pyramidal bottom. “It was early discovered that by the use of this form of punch, constructed with the exact angles indicated, cold metal would flow to the sides, and not be driven ahead of the tools, resulting beneficially in knitting the atoms into greater strength, and also assisting in the work of lateral extension, and without a waste or cutting away of any of the metal so treated, as is the case in the manufacture of the ordinary slotted head screw,” he rather grandly explained.9

An enthusiastic promoter, Robertson found financial backers, talked a small Ontario town, Milton, into giving him a tax-free loan and other concessions, and established his own screw factory. “The big fortunes are in the small inventions,” he trumpeted to prospective investors. “This is considered by many as the biggest little invention of the 20th century so far.”10 In truth, the square socket really was a big improvement. The special square-headed screwdriver fit snuggly—Robertson claimed an accuracy within one one-thousandth of an inch—and never cammed out. Craftsmen, especially furniture-makers and boatbuilders, appreciated the convenience of screws that were self-centering and could be driven with one hand. Industry liked socket-head screws, too, since they reduced product damage and speeded up production. The Fisher Body Company, which made wood bodies in Canada for Ford cars, became a large Robertson customer; so did the new Ford Model T plant in Windsor, Ontario, which soon accounted for a third of Robertson’s output. Within five years of starting, Robertson built his own wire-drawing plant and powerhouse and employed seventy-five workers.

In 1913, Robertson decided to expand his business outside Canada. His father had been a Scottish immigrant, so Robertson set his sights on Britain. He established an independent English company to serve as a base for exporting to Germany and Russia. The venture was not a success. He was thwarted by a combination of undercapitalization, the First World War, the defeat of Germany, and the Russian Revolution. Moreover, it proved difficult to run businesses on two continents. After seven years, unhappy English shareholders replaced Robertson as managing director. The English company struggled along until it was liquidated in 1926. Meanwhile, Robertson turned to the United States. Negotiations with a large screw manufacturer in Buffalo broke down after it became clear that Robertson was unwilling to share control over production decisions. Henry Ford was interested, since his Canadian plants were reputedly saving as much as $2.60 per car using Robertson screws. However, Ford, too, wanted a measure of control that the stubborn Robertson was unwilling to grant. They met but no deal was struck. It was Robertson’s last attempt to export his product. A lifelong bachelor, he spent the rest of his life in Milton, a big fish in a decidedly small pond.

Meanwhile, American automobile manufacturers followed Ford’s lead and stuck to slotted screws. Yet the success of the new Robertson screw did not go unnoticed. In 1936 alone, there were more than twenty American patents for improved screws and screwdrivers. Several of these were granted to Henry F. Phillips, a forty-six-year-old businessman from Portland, Oregon. Like Robertson, Phillips had been a traveling salesman. He was also a promoter of new inventions, and acquired patents from a Portland inventor, John P. Thompson, for a socket screw. Thompson’s socket was too deep to be practicable, but Phillips incorporated its distinctive shape—a cruciform—into an improved design of his own. Like Robertson, Phillips claimed that the socket was “particularly adapted for firm engagement with a correspondingly shaped driving tool or screwdriver, and in such a way that there will be no tendency of the driver to cam out of the recess.”11 Unlike Robertson, however, Phillips did not start his own company but planned to license his patent to screw manufacturers.

All the major screw companies turned him down. “The manufacture and marketing of these articles do not promise sufficient commercial success” was a typical response.12 Phillips did not give up. Several years later a newly appointed president of the giant American Screw Company, which had prospered on the basis of Sloan’s patent for manufacturing pointed screws, agreed to undertake the industrial development of the innovative socket screw. In his patents, Phillips emphasized that the screw was particularly suited to power-driven operations, which at the time chiefly meant automobile assembly lines. The American Screw Company convinced General Motors to test the new screw; it was used first in the 1936 Cadillac. The trial proved so effective that within two years all automobile companies save one had switched to socket screws, and by 1939 most screw manufacturers produced what were now called Phillips screws.

The Phillips screw has many of the same benefits as the Robertson screw (and the added advantage that it can be driven with a conventional screwdriver if necessary). “We estimate that our operators save between 30 and 60 percent of their time by using Phillips screws,” wrote a satisfied builder of boats and gliders.13 “Our men claim they can accomplish at least 75 percent more work than with the old-fashioned type,” maintained a manufacturer of garden furniture.14 Phillips screws—and the familiar cross-tipped screwdrivers—were now everywhere. The First World War had stymied Robertson; the Second World War ensured that the Phillips screw became an industry standard as it was widely adopted by wartime manufacturers. By the mid-1960s, when Phillips’s patents expired, there were more than 160 domestic, and 80 foreign licensees.15

The Phillips screw became the international socket screw; the Robertson screw is used only in Canada and by a select number of American woodworkers.II A few years ago, Consumer Reports tested Robertson and Phillips screwdrivers. “After driving hundreds of screws by hand and with a cordless drill fitted with a Robertson tip, we’re convinced. Compared with slotted and Phillips-head screwdrivers, the Robertson worked faster, with less cam-out.”16 The explanation is simple. Although Phillips designed his screw to have “firm engagement” with the screwdriver, in fact a cruciform recess is a less perfect fit than a square socket. Paradoxically, this very quality is what attracted automobile manufacturers to the Phillips screw. The point of an automated driver turning the screw with increasing force popped out of the recess when the screw was fully set, preventing overscrewing. Thus, a certain degree of cam-out was incorporated into the design from the beginning. However, what worked on the assembly line has bedeviled handymen ever since. Phillips screws are notorious for slippage, cam-out, and stripped sockets (especially if the screw or the screwdriver are improperly made). Here I must confess myself to be a confirmed Robertson user. The square-headed screwdriver sits snugly in the socket: you can shake a Robertson screwdriver, and the screw on the end will not fall off; drive a Robertson screw with a power drill, and the fully set screw simply stops the drill dead; no matter how old, rusty, or painted over, a Robertson screw can always be unscrewed. The “biggest little invention of the twentieth century”? Why not.

I. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, handmade nails were replaced by cut nails, stamped out of sheets of wrought iron (later steel), with a similar rectangular cross-section. Cut nails are sharpened by hand with a file.

II. Starting in the 1950s, Robertson screws began to be used by some American furniture manufacturers, by the mobile-home industry, and eventually by a growing number of craftsmen and hobbyists. The Robertson company itself was purchased by an American conglomerate in 1968.