In this book I have selected the most impressive UFO stories from the British Ministry of Defence’s files on UFOs and examined the results of the occasional government investigations during the twentieth century. After more than 60 years of sightings – more than 100 if you factor in the phantom zeppelins and foo-fighters of the First and Second World Wars – what conclusions can be reached about this puzzling and persistent mystery?

In 1968 Professor R. V. Jones concluded that, if pushed to give his opinion one way or the other on the existence of UFOs, he would have based his decision on the assumption that they were either straight fantasy or the incorrect identification of a ‘rare and unrecognised phenomenon’.1 Just over a decade later, Lord Strabolgi expressed a similar point of view during the House of Lords UFO debate, stating: ‘there really are many strange phenomena in the sky, and these are invariably reported by reliable people, [but] there is a wide range of natural explanations to account for such phenomena’.2

As the many stories collected for this book have shown, it seems likely that a rational explanation, whether mundane or extraordinary, lurks behind almost every UFO report. Although Professor Jones referred to a phenomenon, there is actually no such thing as ‘the UFO phenomenon’. Instead there are many different phenomena that are often grouped together by the media and the UFO literature under the banner of ‘UFO’. A wide variety of different things ultimately cause UFO sightings. These include bright stars and planets, advertising blimps and balloons, hoaxes, concert lights, meteors and space junk burning up in the atmosphere. These UFOs only become Identified Flying Objects after detailed investigation. It is amongst all of this background noise that any genuine UFOs, in the form of alien craft, would be found if they truly existed.

It is true that in some cases, such as the experiences reported by test pilots at Farnborough in 1950 (see Chapter 2), the mysterious phenomena seen by radars at RAF Lakenheath-Bentwaters in 1956 (see Chapter 3) and the lights seen by pilots above the English Channel in 2007 (see Chapter 7), rational explanations are hard to come by. But to say something remains unidentified does not mean the explanation must be extraterrestrial spacecraft. We lack the one thing that would settle the debate once and for all: tangible evidence, such as wreckage from a crash or an artefact of unquestionable extraterrestrial origin.

This leads me to one of the most enduring beliefs that plays a major role in the modern UFO mystery – the government cover-up. Could that be the reason why concrete proof of the existence of UFOs has proved so elusive? Addressing this subject during the 1979 House of Lords debate, Lord Strabogli expressed the view that the idea of an international conspiracy to hide evidence of alien visitations belonged to the world of James Bond. Throughout modern history, governments have failed to agree on almost every subject; it seems improbable that they could all, successfully and successively, have colluded to hide evidence of alien visitations, both from the public and the scientific community, for more than half a century.

Despite recent moves by the British and other governments to be more open about their limited interest in UFOs, official statements on this subject continue to be widely disbelieved. In July 2008, for example, just two months after The National Archives began releasing the most recent of the Ministry of Defence’s UFO files, a survey for The Sun newspaper found that 50 per cent of the respondents said they believed the government might be, or definitely was, concealing evidence from the public. A similar poll conducted in the USA by the Gallup organisation on the fiftieth anniversary of the Roswell incident found 71 per cent of respondents believed the government was hiding knowledge of UFOs.

In November 2011 this will to believe led more than 17,000 Americans to put their signatures on petitions calling for the disclosure of government information on UFOs, and an acknowledgement of contact with extraterrestrials. Responding to both petitions, a White House spokesman said there was: ‘no evidence that any life exists outside our planet, or that an extra-terrestrial presence has contacted or engaged any member of the human race.’ He added: ‘In addition, there is no credible information to suggest that any evidence is being hidden from the public’s eye.’3

The contents of the MoD’s UFO files show that in Britain every new Prime Minister receives requests and petitions from groups and individuals who demand the release of ‘the truth’ about UFOs. At a public meeting during the General Election campaign in 2009, Conservative candidate David Cameron was questioned about comments made by former astronaut Ed Mitchell, who is on record as saying he believes the US government is hiding evidence of alien visits to Earth. Cameron’s response was to crack a joke (p. 172), but he then admitted he had no idea if any UFO incidents ‘had any basis in truth’ and promised that if any evidence did exist ‘it is certainly not something that any Government should seek to hide from anyone’.4

This exchange took place just months after the Labour government released more than 6,000 pages of UFO documents into the public domain via The National Archives. Within those files was an Air Ministry briefing from 1958 in response to a petition that called upon the British government to reveal ‘the facts about flying saucers’. The very first UFO desk officer, David West, responded: ‘The authors of the campaign are firmly convinced that extraterrestrial manifestations have appeared… [but] as it is not possible to release official information about something which does not exist, it is difficult to satisfy those with preconceived ideas to the contrary.’5

Faced with such levels of public distrust, governments have come to realise that honest denials are unlikely to satisfy those convinced that evidence of alien life is being concealed. Such a conspiracy, if it existed, must involve not only all the major world powers but the scientific community too. Writing in 1990 after 50 years studying UFOs and other strange phenomena, Sir Arthur C. Clarke concluded there was no hard evidence that Earth had ever been visited from space. But he said if a visitation ever did occur, at least three independent global radar networks would be aware of it within minutes. He added: ‘… in the unlikely event that the US, [Russian] and Chinese authorities instantly cooperate to suppress the news, they’ll succeed for a maximum of forty-eight hours. How long do you imagine such a secret could be kept?’6

Faced with such a deep-rooted will to believe, attempts by both governments and scientists to demystify the subject and educate the public to identify common sources of UFOs are doomed to failure. The available evidence supports the idea that, in Britain at least, government interest in UFOs was always purely pragmatic and motivated by fears over what first Germany and later Russia might be up to. In 2009 when the MoD last published a policy statement on UFOs, it stated their sole interest in the subject was to establish whether any particular incident had any ‘defence significance’, namely whether UK airspace had been invaded by hostile or unauthorised aircraft. As for visitors from other worlds, the ministry says it has ‘no opinion on the existence or otherwise of extraterrestrial life… however, in over fifty years, no UFO report has revealed any evidence of potential threat to the United Kingdom’.7

Personally, I have no doubt this is the truth. All the MoD’s surviving UFO files are now open to the public and their contents will be interpreted differently by everyone who makes an effort to explore them. Believers in flying saucers and government conspiracies will dismiss them as a whitewash and continue to believe the real ‘top secret’ files are being hidden away somewhere else. Sceptics will see them as more evidence that those who see and believe in UFOs are either mistaken or deluded.

I hope those of you who, like me, remain open-minded will come to realise that although the files contain no evidence of alien visitations, they do tell us much about ourselves and the wonders of the planet we inhabit. They are a unique source of extraordinary testimony from ordinary people who have experienced puzzling phenomena both in the sky and on the ground. However, this testimony does not in itself prove the existence of alien craft any more than it establishes the presence of unfamiliar and exotic natural phenomena.

This conclusion is consistent with the views expressed by the author of the MoD’s Condign report, and scientists like R. V. Jones who speculated about ‘rare and unrecognised phenomenon’ as one possible source for UFOs. Even Sir Arthur C. Clarke, who rejected the ‘Extra-Terrestrial Hypothesis’, recognised there ‘may be strange and surprising meteorological, electrical, or astronomical phenomena still unknown to science that are both genuine and unexplained’.8

During my research for this book, I interviewed a retired MoD scientist who was responsible for checking sighting reports received by the Defence Intelligence Staff during the 1970s. He admitted that a number could not be explained, but said that, given Earth’s status as ‘a rather ordinary little planet’ one of the things he had found ‘strange about the whole business’ was the sheer volume of reports he received, saying: ‘I seem to remember at least half a dozen or more every day. Surely there could not have been that number of aliens?’9

In fact the MoD has received more than 12,000 UFO reports since 1959, a figure that will be only a tiny proportion of the actual total number of sightings, as very few people decide to make an official statement about their experiences. Across the world the total since 1947 must run to millions. This by itself again makes a rather strong case for a rational explanation for most UFO sightings for, put simply, there are just too many UFOs for them all to be alien visitors. What then are the chances that the Earth might be visited today, or even within the short window of time in which human civilisation has existed?

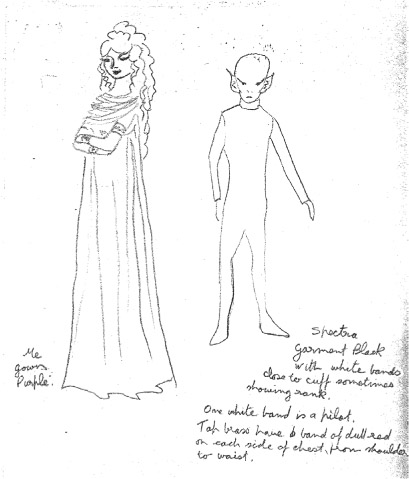

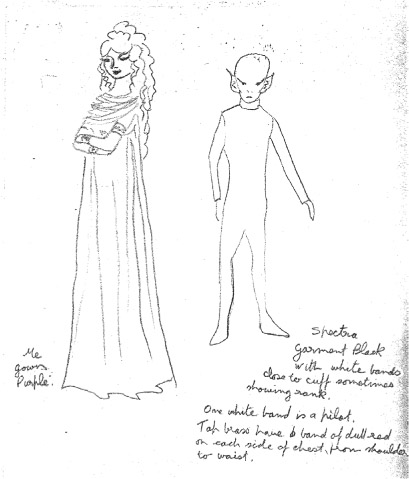

Sketches of alien creatures involved in a galactic war, from a MoD file with the title: ‘Close encounter reports, alien entities, abductions, etc’, opened in 1992. DEFE 24/1943/1

In recent years a new generation of gigantic observatories, including the Hubble Telescope that orbits the Earth, have allowed astronomers to identify thousands of ‘exoplanets’ orbiting stars in other solar systems. In 2011 the first Earth-like planets were discovered orbiting a star called Kepler-20 that lies over 900 light years away in the constellation of Lyra. But so far none of these alien worlds have been assessed as having surface conditions that would support life as we know it. Nevertheless, in the same year Andrei Finklestein, director of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Applied Astronomy Insitute, predicted that ‘life exists on other planets and we will find it within 20 years’.10 Even if we accept that life must exist elsewhere, the evolution of intelligent life requires an even greater level of chance and probabilities. What is the possibility that intelligent aliens might not only exist but have developed the technology and, more importantly, the motivation to travel millions of light years just to visit us? At present this can only be described as unlikely.

Following the opening of the second tranche of UFO files at The National Archives in 2008, Lord Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal and President of the Royal Society, pointed out that the question of extraterrestrial visits does not, as some believe, rely upon whether other planets capable of hosting life exist in other solar systems. Intelligent humans exist today as the result of a mind-boggling series of accidents and coincidences that may just be unique to our planet. In an article published by The Times, Lord Rees pointed out that we may not even recognise a truly alien intelligence if they had developed an unfamiliar technology or method of communication.11 This raises questions that are more to do with biology than astronomy. For example, what are the odds that intelligent life that we could recognise would have evolved in a similar fashion elsewhere in the universe, with a completely different throw of cosmic dice? And even if it had, what is the likelihood that two advanced civilisations could exist simultaneously in separate planetary systems close enough for communication or travel to be possible?

The astronomer Patrick Moore has illustrated this problem by comparing it to a darkened hall in which two lamps are installed. If each lamp were programmed to switch on at random for 10 seconds each day, the chances of them both being illuminated at the same time is similar to the likelihood of two civilisations existing at the same time in adjacent solar systems. When you consider the vast distances separating solar systems even within the Milky Way, those odds lengthen still further.

With our current knowledge of the universe, it is impossible at the present time to be absolutely certain. Whether we believe or not, for the time being we must be content with mystery. Indeed, at some level, perhaps that is what we all want, for mystery is a necessary ingredient in our lives. As Neil Armstrong said in his address to the US Congress following the moon landings of 1969:

‘Mystery creates wonder, and wonder is the basis for man’s desire to understand. Who knows what mysteries will be solved in our lifetime, and what new riddles will become the challenge of the new generations?’