Prior to 1950 flying saucers were widely seen as an American phenomenon, but within just four years people across Britain were seeing them – and believing in them. At this early stage British sightings lacked a little drama in comparison with those that were being reported in America. Even so there were some fascinating accounts from eye-witnesses, such as this incident reported by Flight Lieutenant James Salandin, who was a pilot flying with the RAF’s auxiliary air force:

‘On 10 October 1954 I took off from North Weald on a normal routine flight in a Meteor 8 aircraft. Whilst climbing I noticed a number of trails in the Chatham/Gillingham area at 12 o’clock… When at 15,000 feet I saw what I presumed at the time to be two aeroplanes flying on a reciprocal course to myself but out to my port side… I could not identify these two objects as aeroplanes and I could not follow them due to the fantastic speed at which they were travelling. The first one appeared to be a goldy colour and the second silvery, flying in what appeared to be a loose battle formation. Upon looking ahead again, I saw coming straight towards me at the same height a silvery spherical object with a bun on top and below. When at what I should imagine was only a few hundreds yards distance it went over to my port side… also travelling at some terrific rate of knots. I was completely shaken by the incident and it took me five or ten minutes to pull myself together. Had I not been so shaken I could probably have taken a head-on cine film of the third object… ’1

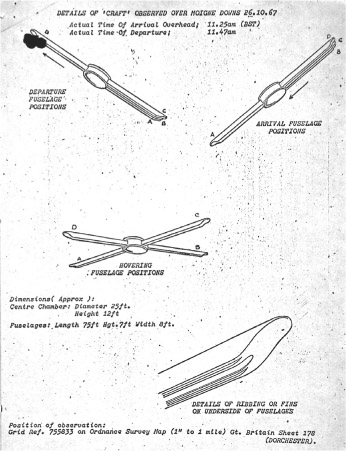

Pilots were not the only people to see flying saucers. On 15 February the same year, a 13-year-old schoolboy took a photograph of a UFO he saw swooping over the Old Men of Coniston mountain in Cumbria. Early that morning Stephen Darbishire was walking on the lower fells with his 8-year-old cousin, Adrian Meyer, ‘when Adrian suddenly shouted “Look! What on Earth’s that?” and pointed to the sky over Dow Crag’. The two boys then saw an object ‘glistening like aluminium in the sunlight’ coming towards them. Stephen said: ‘You could tell the outline of it very plainly indeed and see port-holes along the upper part, and a thing which looked like a hatch on top… I took the first picture when it was moving very slowly about three or four hundred yards away and then it disappeared from my view… When it came into sight again I took another picture but then it suddenly went up into the sky in a great swish.’2

Meanwhile in the USA, the CIA began to take a close interest in Project Blue Book’s investigations. The agency was told by the United States Air Force that around 90 per cent of the sightings reported to them could be explained. However, the CIA’s Dr Harris Marshal Chadwell remained concerned that a small residue of sightings, those he described as ‘incredible reports from credible observers’, could not be ignored. They feared that a UFO panic engineered by the Russians could overload the US air defence system with so many spurious reports that it would not be able to distinguish real aircraft from what he called ‘phantoms’.

A flying saucer photographed by 14-year-old Stephen Darbishire on the slopes of the Old Man of Coniston, Cumbria, in February 1954.

CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith felt that: even if ‘there was only one chance in 10,000 that the phenomenon posed a threat to the security of the country… even that chance could not be taken.’3 Accordingly, in January 1953 the CIA convened a panel of non-military scientists in Washington, chaired by the physicist Dr Bob Robertson, to study the most impressive cases reported to date. Dr Robertson, of the California Institute of Technology, was an interesting choice as chair. Eight years earlier he had taken part in an inquiry into the foo-fighter mystery whilst serving as a scientific intelligence officer in Europe during the Second World War (see p. 24).

Other members of the panel included Nobel Prize winner and radar specialist Dr Luis Alvarez, nuclear physicist Dr Samuel Goudsmit and Dr Lloyd Berkner of Brookhaven National Laboratories. During a period of four days, this team scrutinised two films showing UFOs and reviewed a number of case histories presented by Project Blue Book personnel.

They emerged unconvinced that any of the incidents discussed could not be explained through the application of existing scientific knowledge. The panel could find no evidence that any sightings were observations of extraterrestrial spaceships, or posed any threat to national defence. Their findings underlined the CIA’s desire to control the release of information on unexplained incidents. They also recognised the danger posed by UFO ‘false alarms’ clogging military communication channels at tense periods that might lead the authorities ‘to ignore real indications of hostile action… and the cultivation of a morbid national psychology in which skilful hostile propaganda could induce hysterical behaviour and harmful distrust of duly constituted authority’.4

This paranoid language was typical of the McCarthy era, which was reflected in the panel’s recommendation that federal agencies ‘take immediate steps to strip the Unidentified Flying Objects of the special status they have been given and the aura of mystery they have unfortunately acquired’.

The panel toyed with ideas of elaborate public education campaigns to debunk UFOs, even to the extent of enlisting the resources of the Walt Disney Company to put out an anti-UFO message to the public. None of these suggestions appears to have been implemented, but attempts were made both in the United States and in Britain to restrict the release of information about sightings reported by military personnel unless they could be adequately explained.

Later in 1953 attempts by the British Air Ministry to control the spread of information about UFO sightings reported by RAF personnel were dealt a major blow. On the morning of 3 November, a Vampire night-fighter from RAF West Malling in Kent was on a routine exercise at 20,000 ft over the Thames Estuary when the crew spotted a very bright object straight ahead at a much higher altitude. The UFO was stationary when first seen and shaped like a doughnut with ‘a bright light around the periphery’. As they watched, it disappeared in a south-easterly direction. Their story leaked to the Daily Express who discovered that later that same day a Territorial Army unit had tracked ‘a very large echo’ on their radar moving at 60,000 ft over London. Through a telescope, a sergeant reported seeing ‘a circular or spherical object’ high in the sky.

This story caused a sensation when it appeared on the front page of the Daily Express under the headline ‘Mystery at 60,000 feet’. Questions were tabled in the Commons and on 24 November the Secretary of State for Air, Nigel Birch, moved to reassure MPs there was ‘nothing peculiar about either of the occurrences’. The object seen on radar over London, Birch explained, had been traced to balloons released by the Meteorological Office station at Crawley. They were fitted with ‘a special device to produce as large an echo on a radar screen as an aircraft’. Laughter erupted when an MP asked if the Minister agreed that ‘this story of flying saucers is all balloony’.

Air Ministry files show that orders were sent to all RAF stations in the wake of the unwelcome publicity that followed the West Malling incident, warning that in future all

A restricted Air Ministry letter dated 16 December 1953 that established the first official reporting procedure for UFOs observed by members of the Royal Air Force. The order was sent out after a a sighting by aircrew from RAF West Malling was splashed across page one of the Daily Express. From 1954, all RAF personnel were instructed to report observations to Air Ministry and not to speak to the press. AIR 20/9994

The confidential report of the same incident submitted to Air Ministry by Pilot Officer R.F. Coles. The Air Ministry admitted that Javelin fighters were diverted from an exercise to intercept this UFO but saw nothing. Questioned in Parliament the Secretary of State for Air, George Ward, said this was a ‘false alarm’ created by a flight of RAF Hunter aircraft. AIR 20/9994

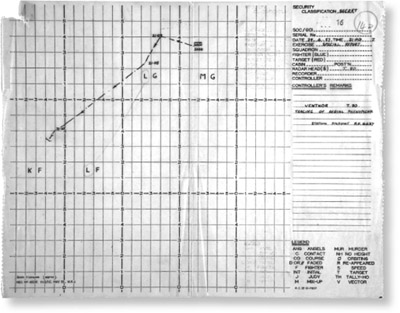

A diagram produced by radar operators at RAF Ventor to depict the movements of ‘aerial phenomena’ over southern England on 29 April 1957. AIR 20/9994

UFO reports ‘are to be classified “Restricted” and personnel are warned not to communicate to anyone other than official persons any information about phenomena they have observed, unless officially authorised to do so.’ The RAF order dated 16 December 1953 said reports should be sent to the air intelligence branch DDI (Tech) who were now responsible for the investigation of all UFO reports. It said because ‘the public attach more credence to reports by RAF personnel than to those from members of the public… it is essential that the information should be examined at Air Ministry and that its release should be controlled officially.’5

This decision marked the first coordinated attempt to define and codify sightings reported to the Air Ministry. In January 1953, shortly after the Robertson panel met (see p. 24), RAF Fighter Command issued the first reporting guidelines for ‘unusual targets’ detected by radar stations. These required that special reports should be made about any targets ‘moving at a ground speed exceeding 700 knots at any height and at any speed above 60,000 feet… When an unusual response is seen, the supervisor… should be informed and he should then check that the echo is not spurious, and arrange for the necessary records to be made.’6 These instructions were updated following the West Freugh incident (see Chapter 2) when RAF personnel were warned: ‘the press are never to be given information about unusual radar sightings… unauthorised disclosures of this type will be viewed as offences under the Official Secrets Act.’7

Later the same year the first Air Ministry UFO report form was drawn up, based upon a template of questions used by Project Blue Book staff. The form listed key facts in 10 categories that included date/time and location, name and address of the witness, the height, speed, shape, size and colour of the phenomena observed and classification of sighting as explained or unexplained. Modified versions of this form, with categories of information listed under alphabetical numerals, were still in use by the MoD until quite recently (see p. 158 for an example from 1996).

From 1954 the new Air Ministry UFO unit produced a yearly report ‘summarising all UFO sightings by types’. An analysis of 80 reports received to end of 1954 formed the basis of an article in a classified publication known as the Air Ministry Secret Intelligence Summary (AMSIS) during March 1955. This summary, based upon a longer air intelligence report now lost, was classified ‘Secret – UK Eyes Only’. Its existence was revealed in May 1955 when the Conservative MP Major Patrick Wall asked the Secretary of State for Air, in a Parliamentary Question, if he would publish the ‘report on flying saucers recently completed by the Air Ministry’. Wall had learned about the report from an informant within the Ministry who told him, via a third party: ‘there are in fact two reports; the first is a full length report going into some 10,000 words. It does include a number of things which the authorities would certainly consider as secret.’8

In his Commons reply, the Air Minister George Ward avoided answering Wall’s question directly. Instead he gave a formal statement that said: ‘reports of “flying saucers” as well as any other abnormal objects in the sky, are investigated as they come in, but there has been no formal inquiry. About 90 per cent of the reports have been found to relate to meteors, balloons, flares and many other objects. The fact that the other 10 per cent are unexplained need be attributed to nothing more sinister than lack of data.’9 A more detailed study of 3,200 sightings reported between 1952-54, conducted by the Battelle Memorial Institute on behalf of the USAF, found that 69% could be identified and 9% had ‘insufficient information’ to reach a conclusion. This left 22% in the category ‘unidentified’, more than double the number the British Air Ministry were unable to explain.

Although Major Wall was unaware of it at the time, George Ward’s statement was evidence of a major change of mind on the part of the British Government. The Flying Saucer Working Party report of 1951 had concluded, in secret, that all UFO reports could be explained (see p. 36). After four years of further investigations, the Air Ministry had admitted that 10 per cent of UFO reports could not after all be explained, even after investigation. The reason given for their continued interest in UFOs was also revealed by the AMSIS report which said ‘there is always the chance of observing foreign aircraft of revolutionary design’ but ‘… as for controlled manifestations from outer space, there is no tangible evidence of their existence’.10

As chilly East–West relations cooled even further during the 1950s, both sides poured money into military technology. The British and Canadian governments flirted with a number of designs for unorthodox aircraft that were inspired by the flying saucer craze. The most famous of these was a saucer-shaped aircraft, code-named Project Y, that was designed by British engineer John Frost for A. V. Roe in Canada.

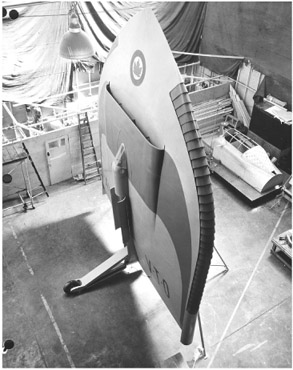

Extravagant claims were made by the company to attract government investment in the project, such as vertical take-off and a high supersonic speed. Photographs taken in a hangar near Toronto in 1953 show a sleek, delta-shaped aircraft that sat on its tail like a rocket.11 A prototype was built but the British government were unimpressed and the project was taken over by the United States Air Force the following year. The American version reverted to the classic saucer-shape but the two prototype ‘Avro-cars’ produced performed poorly in tests and the project was cancelled in 1961.

At the same time, both the United States and the Soviet Union became increasingly drawn into a tit-for-tat game of espionage with the ever-present danger of a nuclear confrontation. From the mid-1950s the CIA began to invest in hi-tech aircraft capable of making covert, long-range missions to spy on military and nuclear installations deep within enemy territory. One result of this was the top-secret Skyhook programme. Skyhooks were balloons constructed from special plastics with diameters of more than 200 ft and a gas capacity double that of the Hindenburg airship. From the late 1940s thousands were launched from Alamogordo Air Force Base, now Holloman AFB, near the White Sands missile range in New Mexico. This was the base whose Mogul balloon trains had been linked to the crash of a ‘flying saucer’ near Roswell in 1947 (see p. 32).

AVIA 65/33 A photograph showing a futuristic ‘flying saucer’ prototype – Project Y – designed by British engineer John Frost and developed by Avro-Canada in 1953. The British government were unimpressed by the performance of the prototype and allowed the project to pass to the US Air Force in 1954. In June that year Dr Harris Marshall Chadwell, deputy head of the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence, asked for reports on ‘the use by any foreign power or nation of non-conventional types of air vehicles, such as or similar to the “saucer-like” planes presently under development by the Anglo/ Canadian efforts.’ AVIA 65/33

As with Mogul, these were no ordinary weather balloons. Their actual purpose was to ride the jet stream to the Soviet Union where sophisticated payloads of cameras suspended in a gondola below the balloons took photographs of sensitive military facilities on the ground. After over-flying Soviet territory, their payload dropped into the ocean where radio beacons guided US planes to collect them.

One of the most dramatic American UFO incidents, when United States Air Force pilot Captain Thomas Mantell crashed to his death whilst chasing a ‘flying saucer’, was later revealed to be linked to a Skyhook launched by the US Navy in 1948 (see p. 35). Skyhooks may also lie behind a number of British sightings, including the RAF West Malling incident of 1953. A declassified history of balloon operations produced by the USAF Missile Development Center in 1958 reveals that balloon number 175, launched from Holloman, New Mexico, on 27 October 1953, failed to drop into the Atlantic at the end of a scheduled 12-hour flight. Six days later it was this, cruising at high altitude over Kent, that was spotted by the RAF crew and which prompted ‘flying saucer’ questions in Parliament (see p. 57).

A former member of the Skyhook project staff, Duke Gildenberg, revealed in 2004 that British intelligence concluded this UFO was the Skyhook balloon, but could not reveal the truth because the project was classified top secret at the time. When the Secretary of State for Air, Nigel Birch, was quizzed in Parliament his explanation simply reflected the official weather balloon line that did not reveal any military secrets.12

The fact that Skyhook flights occasionally triggered UFO panics as they cruised the stratosphere was an unexpected, though not unwelcome by-product (see panel below). At sunset and dawn the huge balloons reflected sunlight to appear as classic silvery ‘flying saucers’ to observers below. Gildenberg said Skyhook staff often monitored long-distance Skyhook flights by following ‘flying saucer’ reports published in newspapers across the world. From 1951 new bases were opened in Scotland, from where the United States Air Force planned to release up to 3,500 of the giant balloons. The project was eventually scrapped in 1956 after achieving only limited success. In total 461 balloons were launched, just half of which penetrated Russian airspace, and of these just 42 gondolas were recovered intact.13

From the 1950s a large number of giant plastic balloons were released by a team led by Professor Frank Powell as part of Bristol University’s research into cosmic rays. Some of the balloons were 300–400 ft in diameter. They were inflated with hydrogen and released from RAF Cardington in Bedfordshire, the home of the airship, to take advantage of light summer winds. The balloons would rise into the upper atmosphere carrying payloads of photographic plates that could weigh as much as a tonne. The polythene from which the balloons were made was translucent and although nearly spherical on release they resembled an ‘inverted pear’ as they rose into the sky. On reaching 100,000 ft, they reflected sunlight and could be seen for hundreds of miles. Balloons released from Cardington would usually follow the prevailing winds and a team from the university were on alert to recover payloads from Ireland, France and other distant locations.

On occasions these cosmic-ray balloons were responsible for ‘flying saucer’ scares. When ‘a shining object’ appeared over Central London in July 1954, newspapers and the Air Ministry were inundated with phone calls from people reporting they had seen a flying saucer. A press photographer chased the object in an aircraft and reported it was ‘as big as a house’. The ‘saucer’ eventually landed in a field near Reading where it was recovered by Professor Powell’s team.

Project files show how throughout the post-war years the Air Ministry liaised closely with Powell’s team in its investigations of UFO sightings.1 Professor Powell told a reporter: ‘every day we send one of these balloons up there will be a least a dozen reports. This is the real secret of the flying saucers if only people would believe it.’ At the same time the US Air Force and RAF were also secretly releasing hundreds of Skyhook spy balloons equipped with cameras to obtain images of Soviet nuclear facilities (see p. 62). One of these giant balloons might account for a UFO pursued by one of Britain’s most experienced test pilots.

Captain Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown is the Fleet Air Arm’s most decorated pilot and holds the world record for aircraft carrier landings. He saw extensive action in the Second World War and, post 1945, he joined an elite group of Allied pilots who test-flew captured German aircraft. In 1956 whilst Commander of the Royal Naval Air Service station at Brawdy, in West Wales, he found himself chasing a ‘flying saucer’. The drama began at dusk on Monday 6 February, when the station received a call from a schoolteacher who said she could see ‘a flying saucer’ cruising over the West Wales coastline. In his memoir, Wings on My Sleeve (1961), Brown says his first reaction was to laugh, but on checking with a pilot returning from an exercise he was surprised to be told: ‘Yes, and I can damn well see it too.’ When one of the air traffic controllers called down to say the object was visible from Brawdy’s control tower, Brown’s scepticism was sorely tested.

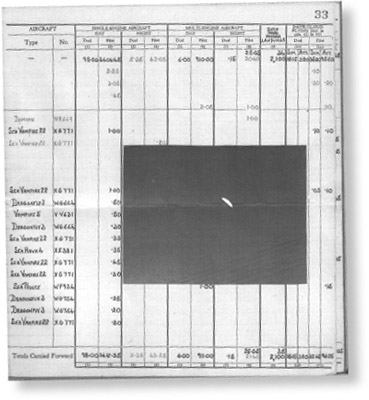

Two pages from the personal flying logbook of Fleet Air Arm test pilot Captain Eric Brown. The entry records the occasion when he pursued a ‘flying saucer’ in the skies above West Wales, one night in February 1956.

‘I decided it was interesting enough to go and have a look at it and leapt off in a Vampire,’ Brown wrote in his memoirs.2 He climbed to 35,000 ft in the gathering gloom, all the while keeping an eye on the object which was ‘still above me and unidentifiable in the fading light’. Although visibility was good, Brown eventually gave up the pursuit and returned to Brawdy. Later that night further reports flooded into newspaper offices from puzzled observers across South Wales and the Bristol Channel region. One phone call received by Brown came from an amateur astronomer who took a photograph of the UFO and was adamant it was not a balloon.

In 2011 Captain Brown told me this conversation led him to reject the cosmic research balloon theory ‘which was the only tangible thing I thought it might be’. In his book he wrote that ‘where I once scoffed, I now have an open mind.’ Today, Brown remains open-minded but is less certain of his conclusion published in Wings on My Sleeve. He said the truth can be found in his flying logbook entry, completed on landing at RNAS Brawdy, which reads:

‘Flying Saucer Chase! Unidentified metallic object in sky, sighted from ground. Scrambled in perplexing chase after some iridescent shape at very high altitude, which was probably a cosmic research balloon. What else?’3

When the Skyhook balloon programme failed to produce satisfactory results, the CIA began testing their high-altitude U-2 spy plane, developed from 1955 at Lockheed’s ‘Skunk Works’ in Burbank, California. The plane could fly at an altitude of 60,000 ft to avoid Soviet radars, way beyond the capabilities of most civil aircraft of the time. The early U-2s were silver, tended to reflect sunlight and often appeared as ‘fiery objects’ to the crews of airliners and military aircraft sent to intercept them. According to the CIA, their staff were able to attribute more than half of all UFO reports made to Project Blue Book from the late 1950s through the 1960s to flights by advanced reconnaissance aircraft such as the U-2 and the SR-71 Blackbird over the US mainland.

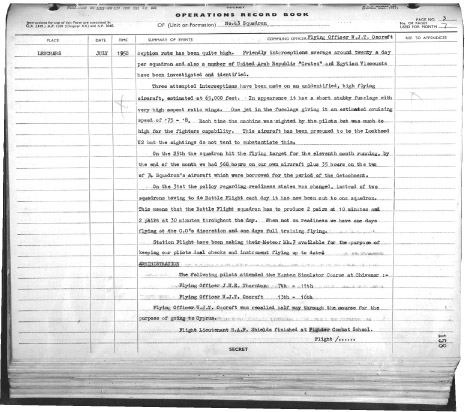

As the United States Air Force received thousands of UFO reports during this period, many of which had other explanations, this estimate seems excessive. However, the operations record book of 43 Squadron based at RAF Nicosia in Cyprus records three occasions in July 1958 when fighter crews tried to intercept ‘an unidentified, high-flying aircraft, [at an estimated height] of 65,000 feet’ over the Mediterranean and above the RAF’s own capability. Crews assumed this aircraft, which had ‘a short stubby fuselage with very high aspect ratio wings’ was the U-2, but the RAF could not confirm this identification as the project was highly classified at the time.14

Spy plane missions were made in radio silence without notification even to friendly countries on their flight path or indeed the United States Air Force’s own air defences. As a result U-2 and SR-71 flights often triggered early-warning systems in the UK and along the Soviet border with Germany. Some researchers believe a number of unexplained UFO reports, such as that from RAF West Freugh in 1957 (see p. 57), where objects were plotted on radar at 70,000 ft, may have been triggered by secret U-2 missions.

An extract from the Operations Record Book of No 43 Squadron, RAF, describing attempted interceptions of ‘an unidentified high-flying aircraft’ over the Mediterranean in 1958. The aircraft was most likely to have been the CIA’s U-2 spyplane. AIR 27/2775

On the other side of the Iron Curtain, the Soviet Union officially denounced UFOs via a 1961 article published in Pravda as ‘fantastic fairytales’ spread by the Americans. Here too, however, they occasionally provided a useful cover for military activities the Soviet military wished to conceal from the West. For example, in September 1977 residents of the city of Petrozavodsk were terrified by the appearance of a glowing object like a ‘giant jellyfish’ that lit up the skies as far west as Leningrad and Helsinki. This UFO was quickly identified by astronomers as the burning tail of a rocket used to launch a spy satellite into orbit from the space centre at Plesetsk. But the Soviet press continued to publish statements from official spokesmen who claimed the spectacular sighting remained unexplained.15

Although a number of Cold War UFO reports could be put down to spy planes, balloons and rocket tests, there were many others made by military pilots from both sides of the Iron Curtain that intelligence agencies have struggled to explain. One of the best-known unexplained incidents occurred at the nuclear-armed United States Air Force airfield at RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk, where the U-2 had been based in April 1956 shortly before the Suez crisis.

On the evening of 13 August 1956, airfield radars at RAF Bentwaters in Suffolk detected a number of unexplained blips, including one travelling at hypersonic speed. Airmen on the ground, and flying in a C-47 transport above the base, reported seeing bright lights, but aircraft sent to investigate could find nothing unusual. Later that night more UFOs were seen on radar by United States Air Force personnel at RAF Lakenheath, 40 miles (65 km) to the northeast; these moved erratically at speeds of between 400 and 600 mph. Lakenheath then alerted RAF Neatishead, a radar station on the Norfolk Broads that defended England’s east coast.

The RAF chief controller at Neatishead, Flight Lieutenant Freddie Wimbledon, came forward in 1978 to describe publicly what happened next. He admitted to being initially sceptical, but on checking his radars he was amazed to see an unidentified target at a height of between 10,000 ft and 20,000 ft. The target moved at tremendous speeds and then stopped suddenly, behaviour that was totally unlike any aircraft he had seen on radar before.

Immediately he gave orders to scramble RAF Venom interceptors. When I spoke to him in 2001 he remembered what happened next: ‘After being vectored onto the tail of the object by the interception controller the pilot called “contact” then a short time later “Judy” which meant the navigator had it fairly and squarely on his own radar screen and needed no further help from my controller. After a few seconds, in the space of one sweep of our screens, the object appeared behind our own fighter and our pilot called out: “Lost contact, more help.” He was told the target was now behind him and I scrambled a second Venom which was vectored towards the area.’16 This drama was overheard by RAF and USAF personnel on the ground. Airman Graham Schofield listened to the radio chatter from the crew room at RAF Waterbeach in Cambridgeshire, where Venom interceptor crews were at readiness. He recalled hearing ‘a shout of confusion from the pilot who had seen nothing. We then heard “I think they are now on our tail!”.’17

One of these aircraft appears to have been flown by Squadron Leader Anthony Davis, a veteran of the Second World War, who was Commanding Officer of 23 Squadron in 1956. In a brief account of his experience written 20 years later, Davis says his Venom night-fighter was vectored by RAF ground control towards a suspected UFO, but his radar operator could not make contact with it and he found himself ‘chasing a star’.18

For his part, Wimbledon remembered the blip on his radar vanishing before the second aircraft approached, almost as if it had given up the chase. He maintained the target was strong and clear, of similar size to a fighter aircraft, but capable of ‘terrific acceleration’ from a standing start.

More UFOs were spotted on Lakenheath radars in the early hours of 14 August, and again Venoms were scrambled to intercept them. The crews of two Venoms came forward with their accounts in 1995 for a BBC programme on Cold War UFOs. The radar operator on the first aircraft, Squadron Leader John Brady, kept a note in his flying logbook that shows his Venom was scrambled at 2.00 am to investigate something seen by United States Air Force radars at low altitude near RAF Lakenheath. He later recalled:

‘The USAF were directing us towards this thing at around 7,000 feet. The first run we had at it I saw nothing. The next time we turned onto a reciprocal heading and I then obtained a contact which I held 10–15 degrees off dead ahead and noticed that it raced down the tube at high speed. We were flying at around 350–400 mph. I remember saying [to the pilot]: “CONTACT … there it’s out 45 starboard now at one mile”… and he kept saying to me: “Where is it? Where is it? I can’t see it!” as we rushed past. And it would go down the right hand side or the left hand side [of the Venom]. Two further runs were made with the same result and it was fairly obvious that whatever it was, it was stationary. [The pilot] looked out on each run but could see nothing. My radar contact was firm but messy, but there was something there!’19

An article summarising the findings of the Air Ministry report on ‘flying saucers’, published as part of their ‘Secret Intelligence Summary’ in 1955, concluded that 90% of UFO sightings could be explained. The original report has not been found in the MoD archives and may have been destroyed. AIR 27/2769

A second Venom sent to assist had no more success and both aircraft returned to base, low on fuel, without identifying their target. Shortly afterwards the UFO disappeared from the United States Air Force’s radar and did not return. Ralph Noyes, working at the Air Ministry at the time, recalled the panic this incident created. Interviewed in 1989 he said: ‘Here we had a number of objects seen coming in across the North Sea on coastal radar. It looked like a Russian mistake. Jet aircraft were scrambled. The objects were travelling at quite impossible speeds and simply made rings round our fastest aircraft. Inevitably this led to the sort of inquiry that you would put in hand if you had any military responsibilities, but we did not particularly want to make public statements about that. Not for something that we had no explanation for.’20

Although details of the Lakenheath incident were recorded by Project Blue Book, the file remained classified for 12 years. In 1956 Blue Book investigators concluded the blips seen on radar were probably spurious echoes caused by ‘unusual weather conditions’ as the events happened on a humid August evening. But when scientists from the University of Colorado UFO project reviewed the file in 1968, their radar expert Gordon Thayer decided it was ‘the most puzzling and unusual case in the radar-visual files’, adding: ‘The apparently rational, intelligence behaviour of the UFO suggests a mechanical device of unknown origin as the most likely explanation for this sighting.’21

A very different conclusion appears in the diary of the RAF’s 23 Squadron covering events in 1956. The diary refers to ‘several attempts’ that were made by its pilots to intercept a ‘strange object’ picked up by radar over Lakenheath, but says nothing was seen by the crews. The diary adds that ‘it was later decided that the object must have been a balloon’. Squadron historian Chris Hann says he believes the diary ‘provides contemporaneous evidence that the incident was not considered of any importance… rather it was an interesting diversion from an otherwise mundane period’.22

This evidence may explain why the Air Ministry destroyed its own records of this remarkable incident. In 1972 one of the key witnesses, now Air Commodore Tony Davis, became head of the MoD branch responsible for UFOs on his retirement from the RAF. During his tenure on the ‘UFO desk’ Davis confirmed, in response to a question from a UFOlogist, that RAF papers covering the incident had been destroyed but added ‘if there had been any evidence to indicate the existence of an unidentified but real flying object (and not just an anomalous radar echo) they would of course have been retained and investigated in great depth’.23

Today the single surviving official reference to the Bentwaters-Lakenheath flap occurs in an intelligence briefing to the Under Secretary of State for Air, George Ward MP, in May 1957. Under the category of ‘unexplained radar incidents’ the note plays down its significance, referring to: ‘a report of an unusual object on Lakenheath Radar which at first moved at a speed of between two and four thousand knots [2,300–4,600 mph] and then remained stationary at a high altitude. No visual contact was made with this object by the Venom sent to intercept it and other radars failed to pick it up.’24

Even the dramatic Lakenheath incident pales in significance compared to the story told by a retired United States Air Force pilot who claims he was ordered to shoot down a UFO over East Anglia. Lieutenant Milton Torres first spoke publicly about his experience at a squadron reunion in 1988 and his written account was sent to the Ministry of Defence shortly afterwards. When the file containing the letter was opened by The National Archives in 2008, it threw new light upon yet another dramatic UFO incident reported by front-line fighter pilots at the height of the Cold War. This story has been pieced together from a number of different sources, including my own correspondence with Milton Torres.

In 1956 Lieutenant Torres flew F-86 sabre dogs with the 406th Fighter Bomber Wing based at RAF Manston in Kent. It was from the runway at Manston that Torres, then a 25-year-old pilot, was waiting in his aircraft when the order came to scramble near midnight one ‘typical English night’ late that year. Whereas other fighter aircraft of the period carried a pilot and navigator, with the F-86D the pilot had to both fly the aircraft and operate the airborne radar. This was used to ‘lock onto’ to the target once it was within a range of 15 miles.

On this particular night Torres received his orders from a RAF controller who was tracking a UFO from an underground radar station at Kelvedon Hatch in Essex. Torres recalls being vectored to a point at 32,000 ft over East Anglia before the action began. Ground control briefed him that the RAF were tracking an unidentified target that had been orbiting the area for some time, displaying ‘very unusual flight patterns’, for example remaining motionless for long periods.

Then orders came to fire afterburners and Torres, with his wingman following slightly behind him and below, turned towards the target. Over the radio the controller asked both pilots to report any visual contact but they could not see anything. Torres then received a startling order to fire a full salvo of rockets at the UFO. The order was so unusual that it remains vivid in his memory today; so unusual that he stalled, demanding authentication before he opened fire. The F-86D had a formidable armoury of 24 unguided rockets – dubbed ‘Mighty Mouse’ – carried in a missile tray beneath the fuselage. Each weighed 18 lbs and had the explosive power of a 75-mm artillery shell.

As seconds passed, authentication was confirmed and in the darkness of his cramped cockpit Torres struggled to select his weapons. His account sent to the MoD in 1988 says: ‘I used my flashlight, still trying to fly and watch my radar… The final turn was given, and the instructions were given to look 30 degrees to port for my bogey… there it was exactly where I was told it would be… burning a hole in the radar with its incredible intensity.’25

In this account Torres describes the size of the blip visible on his radar scope as similar to that produced by a giant B-52 bomber. He remains convinced that it was the best target he could remember having locked onto during his entire flying career. Torres told me what happened next when I interviewed him in 2003: ‘After we were on our final vector I called “Judy” at 15 miles… The F-86D was flat out and at about .92 Mach and we were closing very fast.’ With just 10 seconds to go, Torres saw the target begin to move away from him and was asked again if he could see anything. On his radar screen the blip had broken lock and was now leaving his 30-mile range. He reported the UFO had gone, only to be told the blip had also left the ground scope, in two sweeps of the radar, which he later realised indicated ‘a speed in excess of 1,000 knots (more like double or triple Mach numbers)’.

With the UFO gone, the two pilots returned to RAF Manston with orders to contact the RAF by landline. They were told little other than the mission was considered classified, but the following day he was debriefed by a civilian who arrived from London. In his statement sent to the MoD and released by The National Archives in 2008 he wrote: ‘This gentleman was definitely an American and I think that the ID he had was a National Security Agency – but that is only a perception.… He advised me after listening to my story [that] it was top secret and he forbade me to tell anyone about the incident; he then scared the hell out of me by saying any breach in security would result in my being grounded permanently.’26

Some 30 years passed and it was only after retirement that Torres felt confident to talk publicly about his experience. Compounding the mystery is the almost complete lack of contemporary records relating to the incident. In the files released during 2008, the MoD admit that all Air Ministry UFO records from this period have been destroyed and there is no mention of the incident in the USAF Project Blue Book archives. Only intelligence briefings prepared by the Air Ministry for the Secretary of State George Ward in 1957 have survived at The National Archives. Ward was told there had been three ‘unexplained radar incidents’ during 1956, one of these being the report from RAF Lakenheath. Another involved an object seen on radar by a United States Air Force base in Essex and adds: ‘one of the two aircraft sent to intercept made a momentary contact the other made no contact at all’.27

The documents briefly mention four other radar incidents from 1957 that remained ‘unexplained’, including one when ‘unusual responses which did not resemble aircraft’ were detected by RAF radars on the east coast. Again, fighter aircraft were scrambled but failed to make contact with anything.

Ralph Noyes said he was shown gun-camera film taken by RAF aircrew during this period at a secret screening attended by officials in a sub-ground cinema at the MoD Main Building during 1970. Years later, in a letter sent to the MoD, he says a dozen senior RAF officials were present along with a representative from the Meteorological Office. Noyes said: ‘we were shown some slides, purportedly from aerial photographs taken by [RAF] air crew. The highlight was a couple of brief clips of what I understand to be gun-camera material obtained as far back as 1956. The Bentwaters-Lakenheath events were mentioned. The material was, on the whole, unimpressive: fuzzy greyish blobs in the daylight shots; small glowing globular objects in the night films.’

Noyes said he felt the ‘small informal gathering in the cinema was an opportunity to test the reactions of a few of us to the unusual objects caught on film’. But apart from a suggestion they were witnessing ‘unusual meteorological events’ no conclusions were reached and Noyes heard nothing more about the fate of the films. Files released by The National Archives reveal that following his retirement, Noyes wrote to the MoD twice asking if these films had survived. On both occasions he was told no trace of them could be found. He believed ‘the material was simply scrapped, or “pinched” for someone’s private collection of curiosa, or conceivably passed to the Meteorological Office’.28

From 1953 onwards, the air intelligence branch DDI (Tech) was responsible for the investigation of UFO reports deemed to be possible defence threats. As an intelligence organisation operating in secrecy during a period of great international tension, they were naturally anxious to avoid any security risk that could arise from direct contact with the public, particularly the growing number of UFO enthusiasts. As public fascination with UFOs increased, the Air Ministry decided to offload responsibility for dealing with the public and the press onto a more suitable department. This was S6 (Air), an Air Staff secretariat that routinely dealt with questions relating to RAF activities such as low flying complaints. Civil servants, rather than military officers, were seen as the best choice for those occasions when questions about UFOs required a careful response. A civil servant with S6, David West, set the tone for future UFO policy by noting in 1958 that when dealing with the public he would consult intelligence branches only when it was necessary, ‘but for the most part we expect to be politely unhelpful’.29

A black and white photograph showing a UFO fleet over Sheffield in 1962, taken by 14-year-old Alex Birch on a Box Brownie camera. After the photograph was published in the News of the World, Alex’s father wrote to the Air Ministry offering the print for analysis. He and his son were invited to visit the Air Ministry in London where officials examined the camera and photo. They concluded the photograph was produced by sunlight reflecting from ‘ice crystals’ in the smoky atmosphere. This conclusion satisfied no one and led some UFOlogists and members of the public to suspect the government were determined to ‘cover up’ evidence of alien activity. AIR 2/16918

From that point onwards, S6 and its successors became known publicly as ‘the UFO desk’, the central – and only officially acknowledged – focus for public correspondence on the subject. Although the name of the department dealing with UFOs changed periodically, from S6 to S4 in 1964 and then to DS8 and Sec(AS) during the 1980s, the civil servants responsible for answering letters and Parliamentary questions maintained, in public at least, the same level of official disinterest displayed by David West.

During the course of the next 50 years, even at the busiest times, responding to letters and UFO reports and drafting responses to MPs occupied only a tiny fraction of a desk officer’s duties. As a small part of the department’s wider responsibilities, UFOs were largely looked upon as at best an interesting distraction and at worst a nuisance. As David West explained in 2006: ‘Our policy was largely reactive. When questions were asked by MPs or stories were published in the newspapers we responded. But we were not really focussed on UFOs. At that time we were far more concerned with the Suez crisis.’30

Despite its nickname, it was never the responsibility of those who manned ‘the UFO desk’ to investigate those reports that could not be easily explained. Following the abolition of the Air Ministry and the creation of the unified Ministry of Defence in 1964, this duty was passed to branches of the Defence Intelligence Staff (DIS). Publicly, the MoD said their ‘UFO desk’ dealt with all UFO matters and its staff took advice from other branches only when it was necessary. However, files at The National Archives make it clear that in the few cases ‘where no immediate satisfactory explanation can be determined – i.e. they are truly UFOs’, these were passed to the Defence Intelligence Staff for further investigation. As DI Squadron Leader Cliff Watson put it: ‘S4 (Air) [the UFO desk] was responsible for reports in the public domain, whereas I was responsible for military investigations.’31

Initially, a number of Defence Intelligence Staff branches were secretly involved in UFO investigations, but from 1967 all unexplained incidents were reported to DI55. Their primary role was to collect intelligence on Soviet guided missiles and satellite launches that were occasionally reported as UFOs. Despite the risk involved in making inquiries into UFO sightings, on occasions intelligence officers felt they had no option but to follow up incidents that received national publicity.

One example followed a sighting in January 1966 made by a Cheshire police constable, Colin Perks. The constable, then 28, reported seeing a glowing green object hovering behind a row of houses in Wilmslow whilst on early morning patrol. A copy of his report was sent to the Ministry of Defence. In his police statement Perks reported how:

‘… about 4 am on [7 January 1966] I was checking property at the rear of a large block of shops which are situated off the main A34 Road (Alderley Road) Wilmslow. At 4.10 am I was… facing the back of the shops when I heard a high pitched whine… for a moment I couldn’t place the noise as it was most unfamiliar to the normal surroundings. I turned around and saw a greenish/grey glow in the sky about 100 yards from me and about 35 feet up in the air… I stopped in my tracks and was unable to believe what I could see. However, I gathered myself together after a couple of seconds and made the following observations.

‘The object was about the length of a bus (30 feet) and estimated at being 20 feet wide. It was [elliptical] in shape and emanated a green grey glow which I can only describe as an eerie greeny colour. It appeared to be motionless in itself, that is there is no impression of rotation. The object was about 15 feet in height [with] a flat bottom.

‘At this time it was very bright and there was an east wind. Although it was cold there was no frost… The object remained stationary for about five seconds then without any change in the whine it started moving at a very fast rate in an East-South-East direction. It disappeared from view very quickly. When it started moving it did not appear to rotate but move off sideways with the 30 foot length to the front and rear.’32

PC Perks ended his report: ‘There is no doubt that the object I saw was of a sharp distinctive, definite shape and of a solid substance. However I did not notice any vents, portholes or other place of access. The glow was coming from the exterior of the object and this was the only light which was visible. I checked with Jodrell Bank and Manchester Airport control shortly after the incident but they could not help or in any way account for what I had seen.’

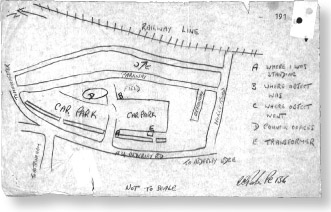

A map drawn by PC Perks showing the position of the UFO he encountered in January 1966 in a car park behind a row of shops in Wilmslow, Cheshire in 1966. AIR 2/17983

A drawing of the same UFO. PC Perks estimated it to have been 30ft in length. AIR 2/17983

Afterwards Perks drew a sketch that shows an elliptical object similar to an upturned jelly mould. The police constable’s account was deemed to be so reliable and detailed that the MoD sent a defence intelligence officer, Flight Lieutenant M. J. P. Mercer, to interview Perks. Details of this visit were kept secret until 1997 when the MoD file containing his report was opened at The National Archives. In Mercer’s report to DIS, he said that PC Perks: ‘had not read any books on the subject [of UFOs] nor had he seen anything similar before. There is no reason to doubt the fact that this constable saw something completely foreign to his previous experience.’33

Mercer visited the scene of the encounter and checked radar records but found nothing unusual had been detected. He concluded his report with the following: ‘On the evidence available… it is not possible to arrive at any concrete conclusion. This is always likely to be the case with such ‘one man’ sightings… On the information available it would be unwise if [we] speculated on possible explanations… [but] it is perhaps pertinent to quote from an article by Dr Allen Hynek, an American astronomer who advises the USAF on the subject of UFOs: “… so far I have come across no convincing evidence that any of these mysterious objects come from outer space or from other worlds.” We would agree with this conclusion.’34

During the summer and autumn of 1967, Britain experienced one of its most intense UFO flaps. The MoD received a sighting virtually every day of that year from a variety of sources including large numbers from police officers. The greatest number of sightings occurred during October 1967 when a spectacular report triggered off a surge of new incidents. In the early hours of 24 October, PCs Roger Willey and Clifford Waycott were on patrol in their police car near Holsworthy in North Devon when they saw a strange light in the sky that appeared to be at treetop height. PC Willey described the UFO as ‘a star-spangled cross radiating points of light from all angles’. The pair drove immediately towards the light, which appeared to move away from them. Giving chase, at one stage their patrol car reached speeds of up to 90 mph as it pursued the UFO along narrow and twisting country lanes on the edge of Dartmoor. PC Roger Willey, speaking at a televised news conference afterwards, said: ‘At first it appeared to the left of us, then went in an arc, and dipped down and we thought it had landed. It seemed to be watching us and wouldn’t let us catch up… It had terrific acceleration and seemed to know we were chasing it.’35

Eventually they gave up the chase and pulled up behind a parked Land Rover to wake the sleeping occupant, 29-year-old Richard Garner. He said one of the policeman pointed to the horizon, where a bright light was hovering in the sky. ‘I thought I was having a nightmare when they woke me up… They said they wanted confirmation of what they had seen. I don’t know what it was, but this object was much too bright for a star.’36

The policeman’s story was featured on TV news and the press dubbed the UFO ‘the flying cross’. For a full week UFOs dominated the headlines and dozens of new reports of the ‘flying cross’ were reported in the early hours by police officers in Hampshire, Sussex and Derbyshire. The MoD file on the events of 1967 at The National Archives contains 79 reports from the month of October alone. One came from retired RAF Wing Commander Eric Cox who spotted a UFO shortly after watching a television news report on the Devon police officer’s experience. Cox was driving with his wife near Fordingbridge in the New Forest the following night when they saw ‘seven lights in the sky at low altitude, very bright but not dazzling’. He said: ‘They appeared to be in a “V” formation and stayed absolutely still, for about three minutes after which time the three on the right-hand side appeared to recede or fade. The remaining four lights then formed into a perfect formation of a cross or plus sign. These remained for about three minutes when they too faded or receded rapidly.’

Cox ended his account: ‘I do not believe in “little green men” nor in flying saucers but I am certain they cannot be dismissed as easily as authority would deem. I have never before seen anything like them and incidentally I am a tee-totaller.’37

The UFO panic led to a series of questions in Parliament and demands for an official study similar to that underway in America, where the University of Colorado had received a contract to produce a scientific report based upon the sightings recorded in Project Blue Book’s files. The MoD resisted pressure for a similar inquiry in Britain but considered calling upon Professor R. V. Jones, now in retirement, to act as a consultant if the sightings continued. Towards the end of the year, a briefing prepared for the Secretary of State for the RAF, Merlyn Rees MP, revealed almost half of the 362 sightings had been identified as aircraft. Satellites and space debris accounted for 57 reports, balloons 42 and bright stars and planets a further 26.

A residue of 46 reports remained ‘unexplained’ but as UFO desk head Jim Carruthers told Mr Rees, these simply lacked ‘information vital to their explanation’. He said there was ‘nothing in any of them to suggest that the incidents to which they relate are any different in nature to those mentioned in the reports that have been explained’. Most were generated not by an increase in UFO activity, he continued, but as a result of an increase in public awareness of the subject. People were looking at the sky, ‘impelled either by the good weather or by Press aroused curiosity… [and] the increased number of reports show that it is becoming fashionable to see UFOs’.38

Meanwhile DI55 sent a scientific officer, Dr John Dickison, to interview the two Devon police constables. His brief report concluded the most likely explanation was they had seen and pursued a bright star or planet, possibly Venus: ‘when questioned… one of the police constables indicated that… he had decided that the light [they saw] came from a spaceship. They did not see a spaceship but only a light and his conclusion appears to have no factual basis.’39

Many of the ‘flying cross’ incidents reported during October 1967 described bright lights seen in the early hours on the eastern horizon, where Venus remained a bright, conspicuous celestial object. In fact, Venus is so often mistaken for a UFO that she has been called ‘the Queen of UFOs’. Two years later Jimmy Carter, who later became President of the United States, was with a group of 10 people who watched a brilliant light low on the horizon that appeared to move towards them and then away whilst changing in brightness, size and colour. They estimated the distance as between 300 ft and 100 ft and said the UFO was at times as big and bright as a full moon. Carter reported the sighting to Project Blue Book in 1973, but when details were checked by an astronomer it was found he was looking directly at the brilliant planet Venus.40

The 1967 UFO flap made the MoD look again at how they dealt with UFOs. Forced into action by pressure from MPs and the media, they assembled a small team of experts drawn from the RAF and the Defence Intelligence Staff, who were placed on stand-by to make field investigations of credible reports. The team included Dr Dickison, Leslie Ackhurst from the ‘UFO desk’ and a RAF psychologist, Alex Cassie. One report scrutinised by this three-man team was one of the strangest ever to reach the MoD.

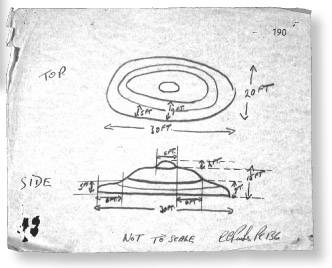

A report and drawing by Angus Brookes describing the transparent ‘flying cross’ he saw hovering above the Moigne Downs, Dorset, in broad daylight on 26 October 1967. AIR 20/11890

A file at The National Archives contains details of the sighting by Angus Brooks, a retired BOAC Comet Flight administration officer. Brooks claimed he had a ‘close encounter’ on the Dorset coast in daylight on 26 October 1967, at the height of the ‘flying cross’ flap. Brooks said he had taken his two dogs for a walk on the Moigne Downs during a fierce gale and found shelter by lying flat on his back in a hollow. In his report to the MoD, he said the UFO suddenly appeared ‘descending at lightning speed’ towards him. It then ‘decelerated with what appeared to be immensely powerful reverse thrust to level out at approximately a quarter of a mile to the south of my position at 200–300 foot height’.

Brooks described this object as 150 ft long with a central circular chamber from the front of which extended a long ‘fuselage’. Three more long fuselages extended from the rear and these moved to positions equidistant around the centre of the craft, so that it took the shape of a giant cross. Brooks said he remained frozen to the spot for the 20 minutes the UFO remained visible fearing that he might be ‘captured’ if he moved. He noticed that the silent object was constructed from some translucent material as ‘[it] took on the colour of the sky above it and changed with clouds passing over it.’ Then the two central fuselages folded back to their original position and the UFO disappeared in the direction of the Winfrith Atomic Research Station. Brooks’ pet Alsatian returned to his side at this point and appeared distraught. He believed that she might have been distressed by a VHF sound emitted by the UFO although he heard nothing during the experience.

Suspecting the object may have been interested in the power station or a nearby US naval base, Brooks reported his sighting to the police and the MoD. When the MoD team, whom Brooks referred to as ‘the James Bond department’, arrived at his home, they were taken to the spot where the UFO hovered and Brooks relived his experience in detail. In their report ‘the James Bond department’ described how they were immediately suspicious that such a large object could have hovered for the length of time claimed without anyone else having spotted it. They decided it was more likely Brooks had seen something ordinary, such as a kite or a hawk, and this had become transformed into a UFO ‘whilst he was in a dream or a near sleep state’. The psychologist member of the MoD team, Alex Cassie, believed that Brooks may have experienced ‘a vivid daydream’ when he lay down to shelter from the wind. He suggested the dream could have been influenced by the news reports of the ‘flying cross’ or triggered off by a piece of dead skin, moving in the fluid of his eyeball.41

Cassie discovered that Brooks had lost the sight in his right eye in an accident, but this had been restored by a corneal graft. He speculated this operation might have made Brooks more prone to seeing elaborate ‘floaters’. But he admitted these would not have remained visible for 20 minutes and he could only account for the whole experience by turning to the ‘daydream’ theory. In his opinion: ‘[Brooks’] instant knowledge and certainty of the size and distance of the UFO and its intent, are all suggestive of the immediate and inexplicable awareness which are characteristic of many dreams.’

Although he could not prove his theory was correct, Cassie concluded ‘it just seems possible, even likely’. But he could not resist adding a caveat, albeit tongue-in-cheek, to his report: ‘if his experience can’t be explained in some such way, then maybe he saw an Extra Terrestrial Object!’ DI55 agreed, but added that ‘[we] think that the probability of there being an E.T.O. is of a very low order’.

Brooks circulated his report to UFO magazines and newspapers before the MoD team produced their conclusion. The Ministry was acutely aware from past experience that any statements they made in writing would receive maximum publicity. In the letter sent to Brooks, Ackhurst carefully explained their theory and said the team did not doubt that he had an experience ‘for which no proven explanation can be given’ but added: ‘we have concluded that you did not see a “craft” either man-made or from outer space.’42

As Daily Express science writer Robert Chapman noted at the time, the MoD’s attempts to explain away Angus Brooks’ experience were doomed to failure because ‘the explanations themselves are as far fetched as, if not more so than, the actual sightings.’ Privately MoD officials felt that all rational explanations should be explored first before turning to fantastic explanations such as extraterrestrial visitors. A secret DI55 briefing from 1968 notes that: ‘we have always said that it would be conceited not to admit that there might be intelligent life in some part of the galaxy; however, we have no scientific evidence that this is so or that there have been penetrations of our environment by any manifestation of such life. There is no scientific evidence that UFOs exist, but there are, of course, plenty of balloons, space junk and hallucinations.’43

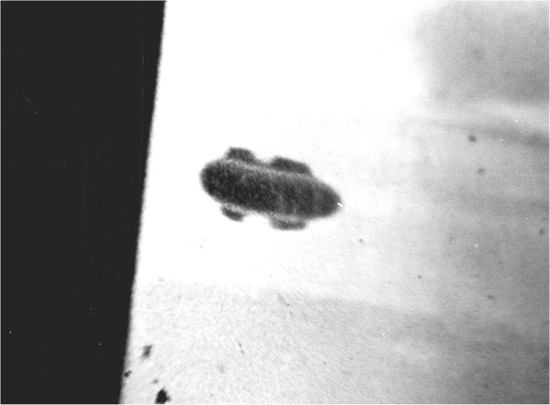

For these reasons doubt would always continue to surround those UFO experiences where the only evidence was the testimony of a single witness. In a few rare cases, however, an explanation came to light that left no shadow of doubt. One of these happened in March 1966 when Joan Oldfield and her husband Tom, from Helmshore, Lancashire, were passengers on an airliner flying from Manchester to London. The couple were on their way to say goodbye to relatives who were emigrating to Australia and carried a cine camera with them.

As the aircraft cruised at 9,000 ft over Staffordshire at 8.00 am on a bright sunny morning, Mrs Oldfield, glancing out of a window, spotted what she first thought was a small plane tracking them. She immediately picked up her cine camera and filmed the object, which was totally unlike any other aircraft she had ever seen. As the film rolled, the flat, cigar-shaped UFO appeared to pull away and retract four fin-like objects into its body before disappearing. When the couple replayed their cine film they discovered they had captured 160 colour frames featuring the UFO, running to seven seconds of viewing time.

The story was flashed around the world and stills from the film were proclaimed by the News of the World as proof that ‘craft from outer space’ had visited Britain. The film was sent to the MoD for study, but it was the BBC who solved the mystery. On 21 April the popular BBC1 evening science programme Tomorrow’s World sent a reporter, Francis Greene, to reconstruct the Oldfield’s exact flight, using the same plane and taking pictures from the same seat the couple used. His film conclusively proved the ‘craft from outer space’ was actually a distorted reflection of the airliner’s tailplane, visible only from one specific spot inside the cabin. As a MoD official noted, the tailplane had been ‘distorted by the optical effects of the curvature of the “porthole glass” [and] the images all appear towards the rear of the porthole, where the glass is curved in towards its mounting’.44

This example illustrates the difficulties faced by official investigations of UFOs where time and resources are always in short supply. The author of the Air Ministry’s Secret Intelligence Summary appreciated this problem when he wrote: ‘the investigation of [UFOs] presents very apparent difficulties, the major one of which is that, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the scent is completely cold. It is only fair to point out that in every other case, i.e. when reports are telephoned and promptly checked on the spot, the sighted object has been identified as a balloon or a conventional aircraft.’45

The UFO that wasn’t. An optical illusion produced by the curvature of the glass in an aeroplane’s window seemed to show a shape-changing UFO over Staffordshire. AIR 2/17983