As the world emerged from the Second World War, the idea that Earth could be under observation or visited by aliens from another world remained largely confined to the realms of science fiction and fantasy. As the Cold War began, people in the West were initially preoccupied not with the idea of life on other worlds, but with the possibility of a future nuclear war with the Soviet Union. As a result, the military authorities continued to seek terrestrial explanations for reports of strange flying objects in the sky.

The first appearance of flying saucers was preceded by reports of strange rocket-shaped flying objects from parts of Scandinavia during the summer of 1946. According to a British intelligence report in the Ministry of Defence’s files at The National Archives, news of these sightings was seized on by the press who began using words such as ‘ghost rockets’ and ‘spook bombs’. The report says the first sightings were made in Sweden: ‘… and for some months there was a considerable number of sightings, mostly in Sweden, but a few also in Norway, Finland and Germany. The descriptions given were usually of some sort of wingless missile travelling at a very high speed, cigar-shaped or circular, sometimes emitting bright lights, and occasionally sound.’1

Scientist and wartime genius Dr. R. V. Jones, who was then the Air Ministry’s director of intelligence, recalled that some of his colleagues believed these flying bombs could be modified V-2 rockets captured by the Russians at the end of the war. Western intelligence agencies, though, wanted to know for sure who had designed these ‘ghost rockets’ and what their purpose might be. Documents at The National Archives show how both the War Office and the Air Ministry quickly became involved in secret negotiations with the Swedish government in an attempt to solve the mystery.2 Secret agents were sent to Scandinavia and advanced radar equipment was offered to the Swedes to assist in tracing the flight path taken by the rockets.

Air intelligence produced two detailed papers summarising their investigations. The contents of these reveal a simmering internal debate between those in the intelligence community who believed the rockets were Russian, and those who believed they were a case of post-war nerves. For example one official ‘… felt this demonstration, if of Russian origin, would be intended to counteract the effect of American atom bomb experiments, by implying the Russians also possess a high performance weapon’.3

The first of these reports, circulated widely within Western intelligence during September 1946, was written by Dr R. V. Jones.4 He was sceptical about the Russian theory and compared the rocket scare with other pre-war social panics, such as rumours the Nazis had developed a death ray. He concluded that something unusual had been seen, but felt most of the ‘rockets’ were actually descriptions of spectacular daylight meteors. Why, he asked his colleagues, would the Russians risk alerting the West to the existence of advanced rockets by firing them over neutral Sweden? From his point of view, only the discovery of physical evidence could establish the truth. During the war the Nazis only achieved 90 per cent reliability in their trials of V-weapons and Jones argued that even if the Soviets could achieve 99 per cent reliability, wreckage of at least one rocket should have been found somewhere in Scandinavia.

By November 1946 the sceptics had gained the upper hand. The numbers of sightings decreased and a second air intelligence report concluded there was very little evidence that any missiles had flown or been fired over Scandinavia. In his memoirs Jones described the 1946 panic as: ‘a diversion… which no doubt arose from the general atmosphere of apprehension that existed in 1945 regarding the motives of the Russians, and which anticipated the flying saucer.’5

The ghost rocket scare was followed just nine months later by the first sightings of ‘flying saucers’ over North America. During this intermediate period radar operators in England continued to be plagued by unexplained blips on their screens similar to those tracked during the Second World War (see p. 22).

A fascinating example of one incident survives in the official Air Force records at The National Archives. According to these, RAF stations were placed on alert early in January 1947 after unidentified aircraft were tracked by Britain’s wartime Chain Home radars. The most alarming incident occurred on the night of 16 January when a ground radar at Trimley Heath, near Felixstowe, tracked what was described as a ‘strange plot’ at 38,000 ft, 50 miles from the Dutch coast during a Bomber Command exercise over the North Sea. The unidentified blip appeared to be descending erratically and was calculated to be moving at a speed faster than sound. It is worth noting here that history records Chuck Yeager’s flight in the experimental Bell XS-I rocket plane, some nine months later, as being the first time the sound barrier was broken.

A concerned HQ Fighter Command immediately ordered a Mosquito to divert from the Bomber Command exercise to intercept the mystery aircraft. A cat-and-mouse chase then ensued for roughly 40 minutes as the Mosquito pursued the unidentified target towards the Norfolk coastline. The blip had descended to 17,000 ft when the Mosquito crew began their interception. However, although the aircraft’s own radar appeared to detect the presence of something on at least two occasions, the pilot was unable to see it in the dark skies. Whatever was out there on that night appeared to take what was described as ‘efficient controlled evasive action’. Soon afterwards the Mosquito crew lost their quarry and the interception was abandoned.6

This startling incident was just the first of a series that continued for a number of weeks. An investigation, code-named ‘Operation Charlie’, was launched, which led to some (though not all) of the blips detected on radar being identified to the Air Ministry’s satisfaction as friendly aircraft and meteorological balloons. In April details were leaked to the Daily Mail which splashed the story across its front page under the headline: ‘Ghost Plane over Coast: RAF spot it – can’t catch it’.7 Newspaper stories dubbed these unexplained radar blips as ‘ghost planes’ and speculation about their origin ranged from smugglers to Russian spy planes developed from captured Nazi technology.

Documents from the US National Archives show that in August 1947 the American Army Air Force were sent a secret summary of the Operation Charlie incidents by the Air Ministry. Their conclusion read: ‘No explanation of this incident has been forthcoming nor has it been repeated.’8 By this time, however, the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) had begun to be inundated with strange sightings of their own.

The flying saucer age can be said to have truly begun shortly after 3.00 pm on 24 June 1947 as Kenneth Arnold, a private pilot, cruised above the Cascade Mountains of Washington State in his light aircraft. He was searching for the wreckage of a transport plane when his attention was suddenly attracted by ‘a tremendous bright flash’ towards Mount Rainier. As he scanned the sky he spotted a group of ‘nine peculiar looking aircraft’ directly in front of him, 25–30 miles away at around 10,000 ft. The aircraft were flying in echelon formation but were, he realised, of a most unusual shape, ‘flat like a pie pan and somewhat bat-shaped’, with the lead craft flying slightly higher than the rest. As he watched, this strange formation shined as it reflected the sun and appeared to be following the mountain ridges below in a peculiar undulating motion.

Initially Arnold had thought the objects were snow geese, but he quickly realised they were flying too high and at incredible speed. Timing them as they moved between distant mountain peaks, Arnold was amazed to find they were travelling at speeds unheard of at that date. Eventually they disappeared towards Mount Adams in the south.

On landing at Yakima Airfield, Arnold told his story and by the time he reached Pendleton in Utah the next day, news had reached the press and he was asked to describe what he had seen. Arnold was later emphatic that he did not call them flying saucers, but that was to be the phrase that caught the world’s imagination. Interviewed for the ITV programme Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World in 1980, four years before his death, Arnold said: ‘When I was asked how the objects flew I said “they flew like a saucer would if you skipped it across water”… and then of course all of a sudden the terms flying disc, crescent-shaped and what-not was completely dropped and everyone started seeing flying saucers. And they’ve been seeing them ever since!’

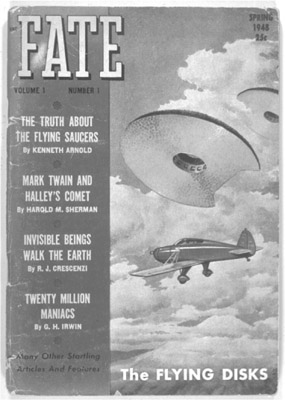

Kenneth Arnold’s seminal sighting of ‘flying saucers’ in June 1947 featured in the first edition of the American magazine Fate.

This was a gift for headline writers and before June was out flying saucers had become a household phrase around the globe. In Britain, for example, a trawl through the Mass Observation Project Archive records reveals the following charming diary entry by a Sheffield woman who wrote on Sunday 6 July 1947: ‘Husband much keyed up about the flying saucers over American skies. One of his pet subjects. Papers can’t report enough about them to satisfy him. Just like a small boy about it.’9 As the historian Hilary Evans noted, ‘looking back to that day… when flying saucers arrived, we can see that they were unquestionably an idea whose time had come.’10

Newspapers were quickly inundated with stories of further sightings, some made months or even years before Arnold’s report. Many of these described ‘flying discs’ but there were also wingless torpedo- and cigar-shaped objects that recalled the ‘ghost rockets’; others were spherical or oval in shape, or simply luminous shapes seen in the night sky. At the time, Arnold has said he assumed the strange aircraft he saw were guided missiles or secret prototype aircraft – a possibility that was pounced on by the media but quickly denied by the US authorities.

This preoccupation with secret weapons was represented in the responses to the first opinion poll on the subject of flying saucers. Conducted by the Gallup organisation and published less than two months after Arnold’s sighting, the poll found an incredible nine out of ten Americans had already heard of flying saucers. Gallup found that 15 per cent of Americans believed that the saucers could be some new form of American military hardware, while, in a nod to Cold War tensions, another one per cent thought they could be Russian in origin.11 But while a significant proportion of respondents believed that the saucers could be the result of misperception or an outright hoax, one possible explanation is at this stage conspicuous by its absence: the belief, later to become widespread, that flying saucers could be of extraterrestrial origin.

One final piece of the jigsaw had to fall into place before the genesis of the flying saucer legend could be complete. On 8 July 1947, whilst the news media was still buzzing with saucer stories, a press release arrived from Roswell Army Air Force base in New Mexico. This part of the US southwest was (and still is) home to some of America’s most secretive defence establishments. It was here that the atomic bomb was developed and tested in great secrecy during the Second World War. After the war, secret research continued on German V-2 rockets and aircraft captured from the Axis forces. Roswell itself was home to the US Army Air Force’s 509th Bomber Wing, at that time the only nuclear-equipped air force in the world.

The announcement from Roswell’s press officer, Lieutenant Walter Haut, read as follows: ‘The many rumours regarding the flying disc became a reality yesterday when the intelligence office of the 509th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force, Roswell Army Air Field, was fortunate enough to gain possession of a disc through the cooperation of one of the local ranchers and the sheriff’s office of Chaves county.’

The statement said the flying object appeared to have landed, not crashed, on a ranch near Roswell a week earlier. It continued: ‘Not having phone facilities, the rancher stored the disc until such time as he was able to contact the Sheriff’s office, who in turn notified Major Jesse A. Marcel of the 509th Bomb Group Intelligence Office. Action was immediately taken and the disc was picked up at the rancher’s home. It was inspected at the Roswell Army Air Field and subsequently loaned by Major Marcel to higher headquarters… ’12

News that a ‘flying saucer’ had been captured by the US military spread like wildfire. Coming so soon after Kenneth Arnold’s report it suggested the mystery could be solved very quickly. The initial excitement was then dampened almost immediately when the 8th Army headquarters at Fort Worth announced that the ‘flying disc’ had in fact been identified as a weather balloon and therefore had nothing to do with flying saucers. According to the commanding officer, Brigadier Roger Ramey, when the remains were examined by meteorologists the ‘disc’ was found to be of ‘flimsy construction, like a box-kite’.

The ‘Roswell incident’ was widely reported by newspapers and radio bulletins across the world, including this example from the Sheffield Telegraph.

This announcement killed the story and Roswell disappeared into obscurity for a further three decades. It did not make headlines again until 1980 when a book, The Roswell Incident, by Charles Berlitz and William Moore, resurrected the story. The authors interviewed Major Jesse Marcel, named in the original press release and now retired from the United States Air Force. Accompanied by two other USAAF officers, Marcel had personally examined fragments of the wreckage found at the Roswell ranch in 1947.

Some 30 years afterwards, he said this consisted of small beams containing writing like hieroglyphics and metal like tinfoil that was extremely tough. He said: ‘It was something I had never seen before, or since, for that matter… I didn’t know what it was but it certainly wasn’t anything built by us and it most certainly wasn’t any weather balloon.’13

The book also featured rumours that bodies of small creatures had been recovered from the wreckage of this and other saucer crashes in remote desert regions of the US southwest, all of which had been removed by the military under great secrecy. The authors claimed the truth – that the US government had captured alien technology – had been concealed ever since. This account gave birth to one of the most enduring conspiracy theories of modern times, the UFO cover-up.

That something happened at Roswell is not in doubt. What is less certain is what that something might have been. The official explanation of what took place has changed several times since 1947 and this ambiguity has been seen by some as proof of Berlitz and Moore’s claims. In 1993 a US congressman for New Mexico, Steven Schiff, asked the General Accounting Office (GAO), the investigative arm of the American Congress, to search the official files for evidence. His intervention led to the production of a USAF report titled The Roswell Files: Fact Versus Fiction in the New Mexico Desert. Published in 1995, this concluded that there was after all a balloon connection. The ‘disc’ had been part of a classified Cold War project, code-named Mogul, which used elaborate balloon trains to carry scientific instruments to the upper atmosphere. However, rather than monitoring the weather, these balloons were used to monitor Soviet nuclear experiments. A balloon train from the Mogul project, launched from Alamogordo, New Mexico, on 4 June, was recorded as being lost in the Roswell area and the original descriptions of scattered debris and a ‘box-kite structure’ do appear to be consistent with the official explanation.

US army meteorologist Irving Newton poses with wreckage of the ‘flying disc’ recovered from the desert near the Roswell Army Air Force base in New Mexico, July 1947. Newton identified the wreckage as fragments from a radar target and the balloon that lifted it.

The report also included a statement by Captain Sheridan Cavitt who was one of the two men who helped Major Marcel collect the debris from the ranch in 1947. Interviewed in 1994, Cavitt’s evidence flatly contradicted Marcel’s story. He said the debris he handled resembled ‘bamboo type square sticks… that were very light, as well as some sort of metallic reflecting material’, but he insisted that it did not possess any unusual properties. Captain Cavitt recalled: ‘the material was spread out on the ground, but there was no gouge or crater or other obvious sign of impact. I remember recognising the material as being consistent with a weather balloon.’ Cavitt added there was no ‘secretive effort or heightened security’ surrounding the incident and he ‘never even thought about it again until well after I retired from the military when I began to be contacted by UFO researchers.’

The 1995 USAF report said the main focus of military concern at the time ‘was not on aliens, hostile or otherwise, but on the Soviet Union’ and concluded: ‘[the results of our] research indicated absolutely no evidence of any kind that a spaceship crashed near Roswell or that any alien occupants were recovered therefrom, in some secret military operation.’14

Wherever the truth may lie, the Roswell incident demonstrated that flying saucers would remain inextricably bound up with military secrets. In the paranoid Cold War context of that time, intense official interest in the subject was inevitable.

The United States Air Force (USAF) only became a separate branch of the military on 18 September 1947, but within 5 days of its formation Lieutenant General Nathan F. Twining of Air Materiel Command had sent a secret ‘opinion on flying discs’ to Brigadier General George Schulgen of the Army Air Force. His view was clear: ‘The reported operating characteristics such as extreme rates of climb, manoeuvrability… and motion which must be considered evasive when sighted or contacted by friendly aircraft and radar, lend belief to the possibility that some of the objects are controlled either manually, automatically or remotely.’15

Significantly, there is no mention of the Roswell incident in Twining’s summary, which was declassified in 1969. Indeed, he specifically refers to ‘the lack of physical evidence in the shape of crash-recovered exhibits which would undeniably prove the existence of these objects’. If the wreckage of a spacecraft had been recovered at Roswell just two months earlier, Twining would surely have known about it. Nevertheless, he took the subject seriously, concluding ‘The phenomenon reported is something real and not visionary or fictitious’ and recommended that a detailed study be undertaken.

As a direct result of the Air Force’s concerns on 30 December 1947, Project Sign was born, with a remit to collect and analyse reports of flying saucers. Within weeks the new project had to deal with the tragic case of a young Air National Guard pilot who died whilst pursuing a strange circular object over Kentucky. Captain Thomas Mantell was the leader of a flight of United States Air Force F-51s sent to investigate the UFO, who flew too high without oxygen, lost consciousness and crashed to his death. Flying saucers were now serious business and could no longer be dismissed as a joke. Following an investigation it was announced that Mantell – an experienced pilot – had actually pursued the planet Venus, which would have been dimly visible in the afternoon sky.

The unconvincing way in which this incident was dealt with provided ammunition to those who smelt a cover-up. The truth would emerge decades later, when it was revealed the object pursued by Mantell was a giant Skyhook balloon released by the US Navy from a base in Minnesota earlier that day. The Skyhook project, like Mogul, was classified secret in 1948 when these events occurred, and the US authorities were prepared to go to great lengths to hide its existence and purpose.

As fears of communist expansion increased, it was logical for the military authorities to concentrate their attention upon the possibility that some of the unexplained saucer sightings could be of Soviet origin. It was known that the Russians had captured German scientists and blueprints of V-weapons and prototype aircraft at the close of the war. For a short time, one faction of the intelligence community believed it was possible these had been developed to produce a disc-shaped aircraft that could reach the US mainland. When it became clear that no terrestrial aircraft could account for the incredible speeds and manoeuvres reported, other explanations had to be considered – and the ‘secret weapon’ hypothesis was replaced by the idea that saucers could be extraterrestrial in origin.

Captain Edward Ruppelt, who worked for Project Sign and has incidentally been credited as the man who coined the acronym UFO, claimed to have seen a top secret dossier prepared by Project Sign staff in 1948 that concluded flying saucers were probably interplanetary spacecraft. Among the unexplained sightings listed in the dossier, according to Ruppelt, were the Operation Charlie incidents, investigated by the RAF. The ‘Estimate of the Situation’, as it was named, was circulated as far as the Chief of the Air Force, General Hoyt Vandenberg, who was unconvinced and ordered all copies to be destroyed.16

This development marked a major change in the United States Air Force policy, perhaps a direct result of the CIA’s growing interest and concern. On 16 December 1948 Project Sign was reborn as Project Grudge, a re-branding that reflected a U-turn from belief to disbelief. The Grudge project’s final report, completed in December 1949, was able to explain all but a small residue of UFO reports and concluded: ‘when psychological and physiological factors are taken into consideration [we believe] that all these incidents can also be rationally explained.’Captain Ruppelt summed up Grudge’s philosophy as being based upon ‘the premise that UFOs couldn’t exist. No matter what you see or hear, don’t believe it.’

Flying saucers were regarded as largely an American phenomenon until 1950, when British newspapers began to take an interest in the growing mystery. During the spring and summer of that year a large number of sightings of mysterious fast-moving lights and objects in the sky were made by ordinary members of the public. Most of these observations were made after dark, but a few occurred during daylight. In April a woman from Chester reported seeing ‘a round object, like a child’s balloon magnified a hundred times, and very bright silver’ flying against the wind.17 Later in the year, disc- and globe-shaped objects were seen by many people in the West Country. In December a rugby match in Rhyl was halted as hundreds of spectators watched a ‘flying tadpole’ zoom across the sky trailing sparks.

Public fascination continued to grow and in the autumn of 1950 two Sunday newspapers serialised the first books on the subject of ‘flying saucers’. The most influential of these was the bluntly titled The Flying Saucers Are Real, by a retired US Marine Corps Major, Donald Keyhoe, who appeared to have highly-placed sources in the American government. Keyhoe claimed the United States Air Force had privately concluded UFOs were of interplanetary origin but feared if this was admitted a mass panic, similar to that which followed the Orson Wells radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds in 1938, would result.

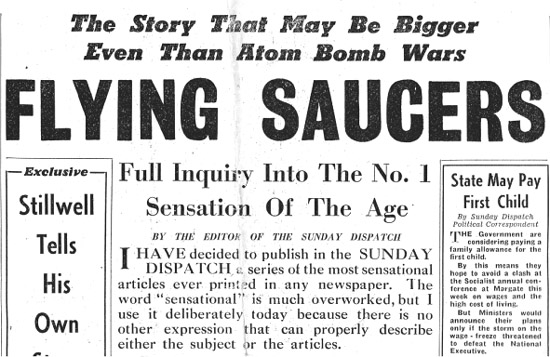

Although Keyhoe’s claims were never officially confirmed, his writings were popular and had a wide impact on the media and public opinion. His books and those of others who followed led a number of senior figures in the British military establishment to treat the subject seriously for the first time. At the forefront of these was Admiral of the Fleet, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, who began collecting accounts of sightings in 1950. Mountbatten was one of a small group of influential military officials who believed the saucers were real and of interplanetary origin. He encouraged his friend Charles Eade, editor of the Sunday Dispatch, to publish them without naming him as his source. In a letter to Eade of 26 March 1950 Mountbatten rejected the idea that flying saucers were secret weapons, boldly stating: ‘The available evidence will show that they are not of human agency, that is to say they do not come from our Earth. If that is so then presumably they must come from some heavenly body, probably a planet… Maybe it is the Shackletons or Scotts of Venus or Mars who are making their first exploration of our Earth.’18 Later that year, in a front-page story, Eade described flying saucers as ‘the story that may be bigger than atom bomb wars’ and referred to his source as ‘one of the most famous men alive today… who commands universal respect and admiration’.19

Another influential establishment figure who took reports of UFOs seriously was the scientist Sir Henry Tizard. Best known for his work on the development of radar before the Second World War, his interest in flying saucers remained a secret until recently. Post-war, Tizard became Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence and, following a number of sightings in the summer of 1950, argued that ‘reports of flying saucers should not be dismissed without some investigation’. It was as a direct result of his influence that the British government was persuaded to set up a small working party to investigate the mystery, reporting to the Directorate of Scientific Intelligence/Joint Technical Intelligence Committee (DSI/JTIC), part of the Ministry of Defence.

Page one headline from The Sunday Dispatch newspaper that launched a ‘flying saucer’series in October 1950. Editor Charles Eade was encouraged to publish stories about saucer sightings by his friend, Admiral of the Fleet, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, who was Chief of Defence Staff from 1959. Initially a believer in UFOs, Mountbatten lost interest in 1962 when Lord Zuckerman, the MoD’s Chief Scientist, assured him the evidence for UFOs was no more convincing than that for ghosts or the Loch Ness Monster.

The working party was created in August 1950. Chaired by G. L. Turney, head of scientific intelligence at the Admiralty, it included five intelligence officers, two of whom were scientists, the other three representing the intelligence branches of the Army, Navy and RAF. The aims and objectives of the team included a review of what was known about the subject, to liaise with the USAF Project Grudge and ‘to examine from now on the evidence on which future reports of British origin of phenomena attributed to ‘Flying Saucers’ are based’.20

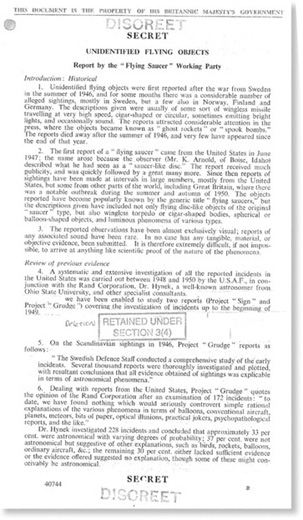

In June 1951, after 11 months of investigations, the working party produced its final report, DSI/JTIC Report No 7 Unidentified Flying Objects. The contents followed the lead taken by Project Grudge to debunk UFO sightings and concluded that flying saucers did not exist. Classified as ‘Secret/Discreet’, the team’s brief six-page report poured cold water on the subject, maintaining that all UFO sightings could be explained as misidentifications of ordinary objects or natural phenomena, optical illusions, psychological delusions and hoaxes.

Of the possibilities reviewed by the Flying Saucer Working Party, the idea that UFOs were spacecraft piloted by interplanetary visitors was given short shrift: ‘When the only material available is a mass of purely subjective evidence it is impossible to give anything like scientific proof that the phenomena observed are, or are not, caused by something entirely novel, such as aircraft of extraterrestrial origin, developed by beings unknown to us on lines more advanced than anything we have thought of.’21

The British team satisfied themselves that most of the sightings did not require such an elaborate hypothesis to explain them and ‘could be accounted for much more simply’. In adopting this approach the team turned to what they described as ‘a very old scientific principle usually attributed to William of Occam’. Occam’s Razor states that the most probable hypothesis is the simplest necessary to explain a scientific problem such as that presented by the UFO mystery. In conclusion the report stated: ‘We accordingly recommend very strongly that no further investigation of reported mysterious aerial phenomena be undertaken, unless and until some material evidence becomes available.’

A senior official from the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence, Dr Harris Marshall Chadwell, was present at the meeting in June 1951 when the report was delivered to the Ministry of Defence. The CIA had closely monitored the United States Air Force investigations since 1948 and was concerned by the growing public fascination in the subject. As a result there was a level of official paranoia concerning news of intelligence interest in UFOs leaking to the media. The British team were informed by the CIA that ‘in order to avoid undue stimulation of a subject that has already received too much public and professional interest’, circulation of the British report should be restricted within the MoD and CIA.

The very existence of the MoD report remained a closely guarded secret for 50 years until I discovered a reference to the existence of the Working Party in the minutes of a meeting that were tucked away among the documents released by The National Archives in 1998. One (now declassified) surviving copy was then discovered in the MoD archives in 2001 and released by The National Archives in the following year. Attached was a covering letter from Directorate of Scientific Intelligence head Bertie Blount to Sir Henry Tizard, that read: ‘This is the report on “Flying Saucers” for which you asked. I hope that it will serve its purpose.’22

The cover and first page of the MoD’s report by the DSI/JTIC Flying Saucer Working Party, completed during the summer of 1951. The working party decided that UFOs did not exist and their conclusions were used to brief Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1952. DEFE 44/119.

This cryptic remark, and the CIA’s influence upon the report’s conclusions, could be taken to imply that a hidden agenda lurked behind the Flying Saucer Working Party’s conclusions – and this is the opinion of one of the UFO witnesses whose incredible story features in the report. In 1950 Stan Hubbard was an experienced test pilot based at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, site of one of the aeronautical industry’s most important annual events, the September air show. On the morning of 15 August 1950, a dry, clear summer’s day, Flight Lieutenant Hubbard was walking along the airfield runway towards his quarters. He later recalled his attention was attracted by what he described as ‘a strange distant humming sound’. I had the chance to interview him in 2002 and he remembered then how, turning to investigate, he saw in the direction of Basingstoke an object that looked ‘for all the world like the edge-on view of a discus, the sort of discus we used to throw at sports day in school… and it was rocking from side to side very slightly… but maintaining a very straight approach. That was something that has stuck in my mind very clearly, vividly, to this day.’23

As it approached the airfield, the sound emanating from the object increased in intensity to become ‘a heavy, dominant humming with an associated subdued crackling-hissing… which reminded me strongly of the noise inside a large active electrical power station.’ He continued: ‘It was light grey in colour a bit like mother of pearl, but blurred. It was obviously reflecting light because as it rocked it looked like a pan lid as you rotate it, with segments of light rotating around. And I could see that around the edge as it went overhead, it was a different colour, it had a definite edge to it. And the whole of the edge was a mass of tiny crackling, sparkling lights. And associated with that, there was a real impact of a very strong ozone smell.

RAF test pilot Stan Hubbard, whose 1950 sighting triggered a secret investigation by the MoD.

‘There were no windows or portholes or any other characteristics at all. It was featureless, and the remarkable thing about it was there was no sound of air movement… as the object was coming closer and then went overhead I tried to estimate its size, altitude and speed, but with the absence of any readily identifiable feature it was difficult to gauge these factors with any confidence… I guessed that its height above ground when first seen was probably between 700 and 1000 [ft] and since it certainly seemed to maintain altitude throughout the period of my observation, I guessed that it would have to be about 100 ft in diameter. It must have been travelling very fast, perhaps as high as 500 to 900 mph.’

Hubbard immediately reported this sighting to his commanding officer and soon afterwards was quizzed by members of the Flying Saucer Working Party. He recalled the questions included: ‘“How high was it?” “How big was it?” “How fast was it?” “What was it?” And one question which I think reflects the tenor of the interview was: ‘“What do you suppose the object was, and where would it have come from?” I replied simply that in my opinion it was not something that had been designed and built on this Earth. Clearly, from the effect it had on the team, it was the wrong answer.’

The working party’s visit to Farnborough would not be the last. On the afternoon of 5 September 1950, just two weeks after Hubbard’s first observation, he saw what he believes was the same object again. On this occasion he was standing with five other serving RAF airmen on the watch-tower waiting for a display by the Hawker P.1081 when he spotted the object in the sky to the south of the airfield, towards Guildford. ‘I grabbed hold of the chap next to me,’ he recalled, ‘and said: “Hey, what do you think that is?” Pointing… and he shouted “My God! Go get a camera quick!, Go get some binoculars!”.’

Hubbard and his colleagues then watched an incredible performance of aerobatics by what the official report describes as ‘a flat disc, light pearl in colour [and] about the size of a shirt button’. Hubbard described it as: ‘fluttering, as though bordering on instability, in a hovering mode, the object would swoop off in a slight dive at incredibly high speed and in quite stable flight, then stop abruptly and go into another fluttering hover mode. This performance was repeated many times… and it appeared that all this was taking place some eight to ten miles south of us over the Farnham area.’

The UFO was under observation for around 10 minutes during which the little crowd had swelled to more than a dozen RAF personnel. ‘They were awestruck,’ Hubbard recalls, ‘but not one of them had a camera! I remember one of them saying “Sorry Stan, I didn’t believe those first stories.” It made my day.’ Within 24 hours they were all questioned by the Flying Saucer Working Party. ‘We were not given their names and we were strictly warned not to ask questions of them, nor make enquiries elsewhere in the Ministry’, Hubbard said. ‘We were also warned not to discuss the subject later, even amongst ourselves in private.’

Despite his misgivings Hubbard believed the assurance given by the Air Ministry member of the team that he ‘had never had a more reliable and authentic sighting than ours’. He was unaware of the outcome of this investigation until I sent him a copy of the working party’s final report after its release in 2001. In its summary of Hubbard’s initial sighting the report said there was no doubt the experienced test pilot had honestly described what he had seen: ‘but we find it impossible to believe that a most unconventional aircraft, of exceptional speed, could have travelled at no great altitude, in the middle of a fine summer morning, over a populous and air-minded district like Farnborough, without attracting the attention of more than one observer.’24

Accordingly, they concluded he was ‘the victim of an optical illusion, or that he observed some quite normal type of aircraft and deceived himself about its shape and speed’. The report then turned its attention to the second incident, which they described as ‘an interesting example of one report influencing another.’ Although Hubbard believed the objects he saw on both occasions were identical, the authors felt this opinion was of little value. While they had no doubt a flying object of some sort had been seen: ‘we again find it impossible to believe that an unconventional aircraft, manoeuvring for some time over a populous area, could have failed to attract the attention of other observers. We conclude that the officers in fact saw some quite normal aircraft, manoeuvring at extreme visual range, and were led by the previous report to believe it to be something abnormal.’25

The working party were satisfied this solution was correct because of another example of misperception reported to them by the Air Ministry member of their team, Wing Commander Myles Formby. Whilst on a rifle range near Portsmouth he spotted what he at first thought was a ‘flying saucer’ in the distance. ‘Visibility was good, there being a cloudless sky and bright sunshine. The object was located and held by a telescope and gave the appearance of being a circular shining disc moving on a regular flight path. It was only after observation had been kept for several minutes, and the altitude of the object changed so that it did not reflect the sunlight to the observer’s eye, that it was identified as being a perfectly normal aircraft.’26

The conclusions of the Flying Saucer Working Party set the pattern for all future British government policy on UFOs. After the report was delivered, the team was dissolved and official investigations ended. However, during the summer of 1952 there was a new wave of sightings across the world. In the United States more than 500 sightings were reported to the US Air Force in July alone, leading future CIA deputy director Major General Charles P. Cabell to launch a new UFO project, Blue Book, under the control of the Air Technical Intelligence Center with Captain Ruppelt as its director.

For the Americans, the most alarming of these sightings occurred in the US capital, Washington DC. On 19 and 20 July 1952, strange moving blips appeared on radars at Washington’s National Airport and at Andrews Air Force Base. The phenomena reappeared the following weekend, sometimes moving slowly, then reversing and moving off at incredible speed. Aircraft were scrambled but the crews saw nothing, despite being vectored towards targets that were visible on ground radar. At the same time, civilian aircrew and ground controllers reported seeing strange lights whilst the phenomena were visible on radar. These events alarmed the Truman administration and led the New York Times to demand why ‘a jet fighter of Air Defence Command, capable of a speed of 600 miles an hour, failed to catch one of the “objects”’.27

A huge press conference was called at the Pentagon as officials moved to calm public fears. High-ranking figures, including the director of United States Air Force intelligence, Major General John Samford, reassured the assembled media the radar blips were probably the result of temperature inversions created by the hot summer weather. These types of unusual conditions, he said, could produce false echoes on radar screens.

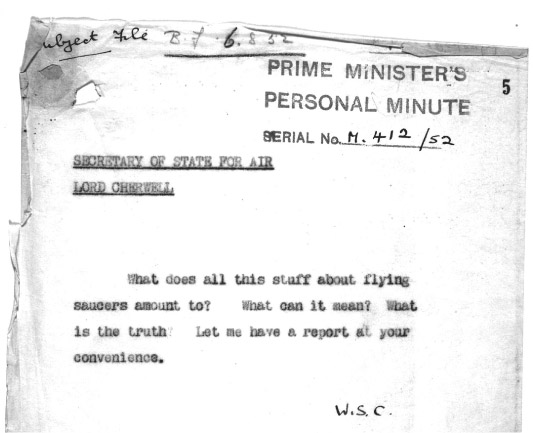

Samford’s public reassurances followed those given to authority figures in private: President Harry Truman himself had been sufficiently concerned to phone Captain Ruppelt asking for an explanation. And Truman was not the only national leader who read the newspaper headlines. On 28 July, the day before the Washington press conference, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had sent a memo to his Secretary of State for Air and copied it to Lord Cherwell, one of his most trusted scientific advisers. This demanded: ‘What does all this stuff about flying saucers amount to? What can it mean? What is the truth? Let me have a report at your convenience.’28

Following a ‘flap’ of UFO sightings over Washington DC, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked the Secretary of State for Air: ‘What does all this stuff about flying saucers amount to?’ PREM 11/855

The Prime Minister received a reassuring response from the Air Ministry on 9 August 1952. Preserved alongside Churchill’s memo at The National Archives, it said UFOs were the subject of ‘a full intelligence study in 1951’ that had concluded all incidents reported could be explained by natural phenomena, misperceptions of aircraft, balloons and birds, optical illusions, psychological delusions and deliberate hoaxes. Churchill was told that an earlier investigation, carried out by the USAF’s Project Grudge in 1948–9 had reached a similar conclusion and that ‘nothing has happened since 1951 to make the Air Staff change their opinion, and, to judge from recent Press statements, the same is true in America.’

The government’s Chief Scientist, Lord Cherwell (Frederick Lindemann) said he ‘agreed entirely’ with the Air Ministry and, in a minute circulated to Cabinet members, dismissed the American saucer scare as ‘a product of mass psychology’. But not everyone was so convinced. On 12 August Churchill’s son-in-law, Duncan Sandys, then Minister of Supply, said he was unable to accept the Chief Scientist’s view without further investigation of the reports. He added: ‘There may, as you say, be no real evidence of the existence of flying saucer aircraft, but there is in my view ample evidence of some unfamiliar and unexplained phenomenon.’29

The division in the establishment between those who ‘believed’ that reports of flying saucers should be taken seriously, such as Duncan Sandys and Lord Mountbatten, and those who dismissed the whole subject as ‘mass hysteria’ was growing (see below). The sceptics tended to be scientists, who applied cold logic to the UFO question and demanded solid evidence, and their opinion was ultimately the most influential.

During the 1950s the debate between believers and sceptics over the existence of flying saucers raged in the highest levels of the military, the government and even the Royal Family. Among the key ‘believers’ were Louis Mountbatten and his cousin Prince Philip, whose equerry, Sir Peter Horsley, was given carte blanche to collect accounts of sightings by RAF aircrew for royal scrutiny. But whilst Mountbatten preferred to keep his personal interest secret, in 1954 the spiritualist Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, of Battle of Britain fame, publicly proclaimed his faith in the existence of flying saucers in the pages of a Sunday newspaper. Within government, Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s son-in-law and future Minister of Defence, Duncan Sandys, said he believed some of the ‘evidence’. Sandys took a pragmatic view, insisting the evidence for flying saucers was no different to the first reports of the German V-2 rockets during 1943, which ‘all our leading scientists declared to be technically impossible’. In 1952 he clashed with the British government’s Chief Scientist, Lord Cherwell, who believed all UFO sightings could be explained.’ (see p. 42). The exchange followed Sandys’ tour of the 2nd Tactical Air Force in Germany where he heard a RAF pilot had reported seeing a UFO whilst on a training exercise.

On 30 July 1952, just two days after Churchill drafted his famous minute on ‘flying saucers’(see p. 43), a RAF Vampire flown by 22-year-old Sgt Roland Hughes was intercepted by a mysterious flying object high above Germany. Hughes was looking upwards through his canopy as the formation of four aircraft from 20 Squadron turned to return to base when he caught sight of a ‘flash of silver light’ high above them. Within seconds the light appeared to race downwards towards him until it resolved into a ‘flying disc’ hanging stationary in the sky. It appeared to be at least 100 ft in diameter – about the wingspan of a wartime Lancaster bomber. Decades later he told his son Brian how, ‘looking at it in sheer amazement from below he could clearly make out, with astonishing clarity, the disc’s highly reflective and absolutely seamless metallic-looking surface.’ Then, as quickly as it appeared, it accelerated upwards and vanished. The young pilot was so dumbfounded he did not make a report about his sighting until the formation landed at RAF Oldenburg. Then he discovered none of the other three pilots had seen anything unusual. But his sighting was taken so seriously that on 5 August he was ordered to fly to RAF Fassberg where he was to report to a senior officer. On arrival in the officer’s mess he was amazed to find a visiting government minister, Duncan Sandys, was waiting to hear his story. After hearing Sgt Hughes’s account, Sandys asked: ‘How many beers had you had the night before?’. At which point the Air Officer Commanding interjected: ‘No, they picked it up on radar – travelling at speeds far in excess of any known aircraft.’ This was the first Sgt Hughes knew about the flying saucer being observed by ground radar. It was immediately obvious that some form of investigation had been carried out behind the scenes that had uncovered supporting evidence. After the incident a member of the ground crew obtained permission to paint a picture of a ‘flying saucer’ on the fuselage of the Vampire flown by Sgt Hughes on that fateful day (see p. 46). As his nickname in the RAF was ‘Sam’ the words ‘Saucer Sam’ were painted in inverted commas underneath a sketch of a tea saucer sporting two little wings. The UFO experience stayed with Sgt Hughes for the rest of his life, but he could never understand why his three colleagues failed to see the flying saucer. Before he died in 2009, at the age of 79, he confided in his son that he wondered ‘if it had some means of stopping the others from seeing it and only allowed me to see it’.1

In official papers Duncan Sandys implied that his interview with Sgt Hughes turned him from a sceptic into a believer in flying saucers. Responding to the sceptical Lord Cherwell, he said he had no doubt Sgt Hughes ‘saw a phenomenon similar to that described by numerous observers in the United States’.2

A page from the flying logbook of RAF Vampire pilot Sgt Roland Hughes recording his sighting of a ‘flying saucer’ over Germany in 1952 and his subsequent meeting with a government minister, Duncan Sandys.

A photograph showing Sgt Hughes – whose RAF nickname was Sam – beside the RAF Vampire that was painted with a cartoon showing a UFO and the words ‘Saucer Sam’.

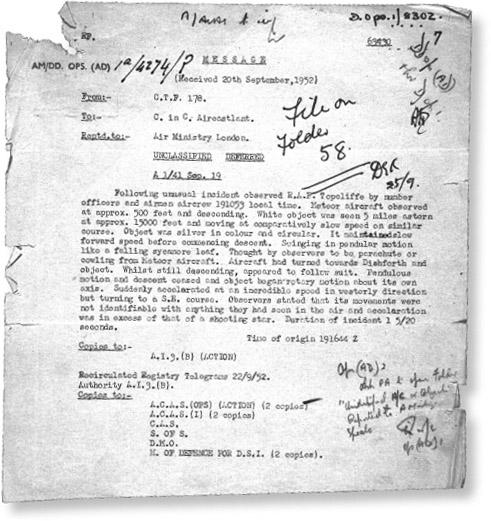

With the debate ongoing, events were to take another unexpected turn when a fresh series of sightings occurred during a major NATO exercise in Europe, Operation Mainbrace. The most dramatic was reported by a group of Shackleton aircrew who saw a circular silver object above the airfield at RAF Topcliffe, North Yorkshire, on the afternoon of 19 September 1952. A report made to Topcliffe’s commanding officer by one of the men, Flight Lieutenant John Kilburn of 269 Squadron, can be found among the Fighter Command papers preserved at The National Archives. In this, Kilburn said he was standing on the airfield with four other Shackleton aircrew watching a Meteor fighter descending: ‘The Meteor was at approximately 5,000 feet and approaching from the east. Flt Lt Paris suddenly noticed a white object in the sky at a height between ten and twenty thousand feet some five miles astern of the Meteor. The object was silver in colour and circular in shape, it appeared to be travelling at a much slower speed than the Meteor but was on a similar course. It maintained the slow forward speed for a few seconds before commencing to descend, swinging in a pendular motion during descent similar to a falling sycamore leaf. This was at first thought to be a parachute or engine cowling. The Meteor, meanwhile, turned towards Dishforth and the object, while continuing its descent, appeared to follow suit. After a further few seconds, the object stopped its pendulous motion and its descent, and began to rotate on its own axis. Suddenly it accelerated at an incredible speed towards the west turning onto a south easterly heading before disappearing. All this occurred in a matter of fifteen to twenty seconds. The acceleration was in excess of that of a shooting star. I have never seen such a phenomenon before. The movements of the object were not identifiable with anything I have seen in the air and the rate of acceleration was unbelievable.’30

As in America, the year 1952 was to be a busy one for UFOs and the Topcliffe incident was just the first in a series of reports made by military personnel that reached the Air Ministry. There were also a growing number of incidents involving the tracking of fast-moving unidentified objects on RAF radars. For example, on 21 October 1952 a flying instructor and his Royal Navy student were in a Meteor jet on exercise from the RAF’s central flying school at Little Rissington, Gloucestershire, when they saw three saucer-shaped UFOs. Flight Lieutenant Michael Swiney, who later served in air intelligence and retired at the rank of Air Commodore, vividly remembers this encounter. The circular plate-like objects were also clearly observed by his student, Lieutenant David Crofts. They became visible when the Meteor punched through a layer of cloud at around 12,000 ft. Initially Swiney thought they were three parachutes descending towards them. Crofts described them as elliptical in shape and iridescent, like circular pieces of glass reflecting the sun.

Shaken, Swiney abandoned the training flight and reported the sighting to ground control. The objects, stationary at first, appeared to change position and then vanished. Subsequently he learned that aircraft were scrambled by Fighter Command to intercept these UFOs. When I interviewed Michael Swiney in 2004 he recalled his reaction: ‘I was frightened, I make no bones about it. It was something supernatural, perhaps, and when I landed someone told me I looked as if I had seen a ghost. I immediately thought of saucers, because that was actually what they looked like… I even put an entry in my logbook, which reads: “saucers!… 3 ‘flying saucers’ sighted at height, confirmed by GCI [radar]”.31

A sighting of a ‘flying saucer’ by RAF Shackleton aircrew in Yorkshire during a NATO exercise made news headlines in September 1952.

Details of the Topcliffe incident were circulated to Air Ministry intelligence in this message dated 20 September 1952. AIR 20 /7390

On landing at Little Rissington, the two men were ordered to remain in their quarters until the following day, when an Air Ministry team arrived to interview them. The team took statements and asked the men to draw what they had seen. Lieutenant Crofts recalls he was told ‘they [Air Intelligence] had been in communication with every country in the world that was likely to have that sort of aircraft in the vicinity and drew a blank’. When I interviewed David Crofts in 2004 he remembered: ‘They also said they [the UFOs] had been picked up on radar; fighters had been scrambled and the target had a ground speed of 600 knots, heading east but the fighters saw nothing, didn’t make a contact and returned to base.’32

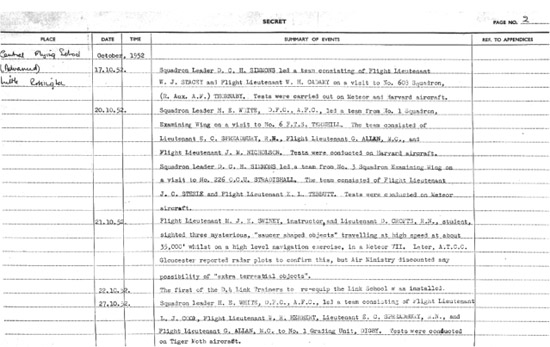

Despite this clear testimony it appears the men’s statements describing this dramatic incident were subsequently destroyed. On his retirement, Air Commodore Swiney made inquiries with the MoD hoping to locate a copy of his original report on the incident. He was amazed to learn that most records of UFOs before 1962 had been routinely shredded. Today all that remains in the files at The National Archives is a single surviving reference in the flying school’s operations record book which simply records how the two men ‘sighted three mysterious “saucer-shaped objects” travelling at high speed at about 35,000 feet whilst on a high level navigation exercise’. The document adds that air traffic control later reported radar plots that appeared to confirm their report ‘but Air Ministry discounted any possibility of “extraterrestrial objects”.’33

An extract from the Operations Record Book of RAF Little Rissington that includes a sighting of ‘three mysterious saucer shaped objects’ by the crew of a RAF Meteor jet on 21 October 1952. AIR 29/2310

Writing in 1988 Ralph Noyes, who was private secretary to the Vice Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Ralph Cochrane, at the time recalled their ‘own embarrassed unease, widely shared by the [RAF] operations staff, that “our own people” had begun to fall for “that saucer nonsense”’.34 Indeed, as a direct result of these incidents a decision was taken in 1953 that the Air Ministry should investigate UFO reports on a permanent basis and responsibility for this was delegated by the Chief of the Air Staff to a section of the air technical intelligence branch, DDI (Tech). The memoirs of Captain Edward Ruppelt refer to an exchange visit to Project Blue Book’s base at Wright-Patterson airfield, Ohio, by two RAF officers shortly afterwards. In his Report on Unidentified Flying Objects, published in 1956, Ruppelt revealed the officers were in the US ‘on a classified mission’ during which one admitted the sightings during Operation Mainbrace had ‘caused the RAF to officially recognise the UFO’.

One of the features of the UFO phenomenon that most concerned the Air Ministry was visual sightings that appeared to be corroborated by radar operators, as featured in the report by Michael Swiney and David Crofts. Unexplained phenomena had been tracked on RAF radars early in the Second World War (see p. 23) and again during the ‘ghost plane’ flap of 1947 (see p. 30), but until 1952 none of these had involved visual sightings.

In his history of UK air defence radar systems, Watching the Skies, Jack Gough says that ‘angel’ and ‘ghost’ echoes continued to plague RAF radars during the early 1950s. These sometimes appeared on ground radar ‘as a cloud of responses very similar to the echoes obtained by small aircraft’. When tracked as individual echoes, they could easily be mistaken for military aircraft as they followed a steady course and were plotted at heights from 2 ft to 10,000 ft.35

The Air Ministry turned to their scientists to provide a solution to this problem. Initially there were two competing theories to explain ‘angels’. The first was they were caused by unusual conditions in the atmosphere that created pockets of air that bent and reflected radar beams to produce false targets. This appeared likely, but could not explain how some ‘angels’ moved against the prevailing winds or travelled faster than measured wind speeds.

The second improbable-seeming theory was that angels were really formations of birds flying to and from their breeding grounds as part of their annual migrations. At the time, the few ornithologists who were using radar to study bird movements had problems persuading the RAF to take this theory seriously. However, during the war, staff at coastal radar stations had linked ‘angels’ on their screens with flights of seabirds tracked with the naked eye. On rare occasions large individual birds had been known to cause chaos. Barry Huddart, who served with Fighter Command HQ in 1957, recalled one incident ‘when fighters were scrambled to intercept an echo on a radar screen which turned out to be a Golden Eagle at 25,000 ft in a jet stream, very unusual but nonetheless true’.36

By 1957 Fighter Command HQ was so concerned by the ‘angel’ problem that it ordered a secret investigation by its Research Branch. The two-year study was to combine the skills of its radar technicians with the expertise of British ornithologists. Selected RAF radar stations around the east coast were asked to send film from their radar cameras for analysis. Meanwhile, morbid experiments were carried out to measure the echoing area of various types of birds. Dead animals were obtained from bird sanctuaries, their bodies were wrapped in cellophane and then spun whilst radar was bounced off them to measure their ‘echoing area’.

The investigation was concentrated around one key radar station where ‘angels’ had been frequently reported. RAF Trimingham, on the north Norfolk coast, was one of the first to be equipped with a new powerful radar, the Type 80. Ornithologist David Lack used this to track ‘angel’ echoes for a year. His study revealed the heaviest ‘angel’ activity occurred during the spring and autumn months, usually at night in calm weather when birds were migrating over the sea at heights from 2,000 ft to 4,000 ft. Lack and his colleagues were able to demonstrate that what the radar operators were actually seeing were flocks of small birds migrating to and from East Anglia and Continental Europe. These observations led the RAF inquiry to conclude in 1958 that most ‘angel’ echoes on radar were caused by birds after all.37

Nevertheless, a big problem remained. How could ‘angels’ be eliminated from radar without playing havoc with the tracking and control of military aircraft? The answer was a gadget that simply tuned out the ‘noise’ created by the presence of smaller birds and other clutter from radar screens whilst at the same increasing the strength and visibility of echoes created by aircraft. This system was simplified further when all ‘friendly’ aircraft were fitted with transponders that transmit a coded identification signal to ground stations.

Advances in radar technology may explain why the majority of accounts describing UFOs on radar were made during the 1940s and 1950s, before technological innovations removed the noise that plagued older systems. The older post-war radars appear to have been more effective detectors of a range of natural and unusual phenomena including ‘angels’ and some UFOs. Once computers were used to remove anything that did not behave like an aircraft from screens, reports of UFOs on radar became rarer. This was brought home to me during a visit to a busy RAF radar control centre in 2005. When I asked one of the operators if they ever detected UFOs she replied, with a smile: ‘Sometimes, but when we spot one we just send for the technicians who come along and tune them out.’

Nonetheless, the main purpose of air defence radars is to detect unidentified aircraft that might pose a threat to the security of the UK. On rare occasions, some radar UFOs defied all attempts to explain them as ‘angels’ or other naturally occurring phenomena. One of the best examples took place on 4 April 1957 when a formation of UFOs was tracked over the Irish Sea. Unlike other similar incidents that were kept secret, the radar operators in this case were civilians and the story appeared in the national media. Newspapers discovered the objects had been seen on radar at a record-breaking 70,000 ft, far beyond the capability of most aircraft of the day. This led to speculation these UFOs could have been long-range Russian or American spy planes. The incident caused a major panic within the Air Ministry and led to questions in Parliament and at the Joint Intelligence Committee.

Wing Commander Peter Whitworth, who was commanding officer of RAF West Freugh in 1957, sent the following detailed account of this incident to the MoD in 1971 after he was approached by a UFO researcher. He asked the MoD for permission to release details, which even then were protected by the Official Secrets Act, writing: ‘The radars used at West Freugh were extremely accurate and reliable. They were used for “blind-bombing” if weather conditions were too bad for the bomb-aimer to see the target in Luce Bay. The plotting of the UFO was thus a true and accurate plot, confirmed by two radar operators, 14 miles apart. At the time of the sighting, there was unbroken cloud at approximately 1,000 ft over the whole area. The UFO was not seen or heard… [it] was first seen when the radar at Balscalloch, near Corsewall Point, north of Stranraer, “locked on” to the object. This showed the UFO to be over the sea, about 20–25 miles N-West of Stranraer; it was at approx 51,000 ft and absolutely stationary in space. This so surprised the radar operator, he called up the other operator at Ardwell (14 miles away) and asked if he had anything on his screen. The Ardwell operator switched-on his set and at once the radar picked up the UFO. Both operators then tracked the UFO until it disappeared from their screens, approx four minutes later.

‘After remaining stationary for a short time, the UFO began to rise vertically, with no forward movement, rising rapidly to approx 60,000 ft in much less than a minute. The UFO then began to move in an Easterly direction, slowly at first but later accelerating very fast and travelling towards Newton Stewart, losing height on the way. Near Newton Stewart the UFO made a very sharp turn to the South-West, still at very high speed and losing height approx 15,000 ft, it continued on the S-West course towards the Isle of Man, when radar contact was lost… the sharp turn made near Newton Stewart would be impossible for any aircraft travelling at similar speed, according to one of the radar operators.’38

This letter survives at The National Archives alongside a detailed air intelligence report covering the investigation of this incident. The report confirms most of the details in Whitworth’s account written 15 years after the event. It says that five objects were detected by three radars at least one of which rose to an altitude of 70,000 ft where it remained, while at other times the formation moved as speeds of around 240 mph. Shortly before the objects disappeared, the operators saw up to four smaller objects moving in line astern about 4,000 yds from each other.

The report notes how ‘the radar operators [said] the sizes of the echoes were considerably larger than would be expected from normal aircraft. In fact they considered that the size was nearer that of a ship’s echo’. It adds that nothing could be said of physical construction of these UFOs ‘except they were very effective reflectors of radar signals, and that they must have been either of considerable size or else constructed to be especially good reflectors’. Inquiries ruled out aircraft, meteorological balloons and thunderclouds as explanations and the report concluded with a startling statement that is the closest the Air Ministry ever came to an admission that UFOs did exist: ‘It is concluded that the incident was due to the presence of five reflecting objects of unidentified type and origin.’39

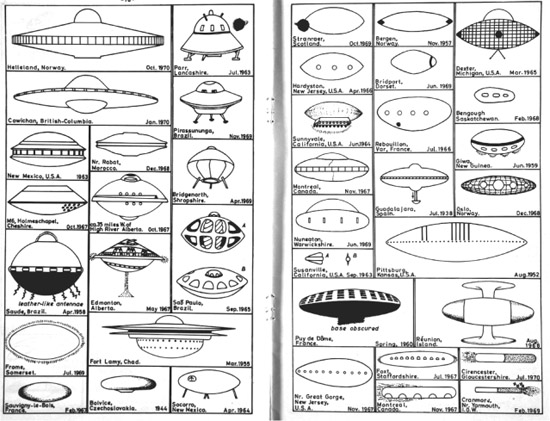

No two UFOs are identical. In the years that followed the first flying saucer sightings, reports of many different sized and shaped UFOs were made, as demonstrated by this 1971 spread from The UFO Register, a magazine produced by Contact UK. 77 different types of UFO were depicted. AIR 20/19086

After the story appeared in the press, the Air Ministry were questioned about UFOs at a meeting of the Joint Intelligence Committee at the Cabinet Office. In response to their concerns, Air Vice Marshal Bill McDonald reassured the committee that ‘all of these phenomena have… been satisfactorily explained through mistakes in radar interpretation, maladjustment of sets, as balloons or even as aircraft’.40 Plainly this was not the case as the West Freugh incident was one of a number that remained listed as ‘unexplained’ in air intelligence files.

The Cold War was now at its height and UFOs remained a persistent and troubling problem for the air forces of the world. Ralph Noyes, who served as private secretary to the Vice Chief of Air Staff and later rose to the rank of Assistant Under Secretary of State for Defence, admitted to me in a 1989 interview that West Freugh and other incidents left the Air Staff in ‘little doubt something had taken place for which we had no explanation’.41 He added: ‘Not once, however, was there the faintest suggestion that extraterrestrials might be in question. We suspected the Russians. We suspected faulty radar. We wondered whether RAF personnel might be succumbing to hallucinogens. But we found no evidence of any such things and in the end, and fairly swiftly, we simply forgot these uncomfortable “intrusions”.’