Throughout recorded history humans have observed objects in the heavens that they have been unable to identify. Until relatively recently celestial phenomena such as comets, the aurora and eclipses of the sun and moon were regarded with superstitious awe and terror. Today most people have a basic understanding of an eclipse and the origins of comets and meteors, but there remain many less readily recognisable things in the sky. Together such phenomena fall into the category of Unidentified Flying Objects, or UFOs, a term that covers anything in the heavens which cannot be easily identified but carries the heavy implication of an extraterrestrial origin. But if you know where to look, history is full of accounts that seem spookily similar to modern UFO sightings, although contemporary explanations were often very different.

In ancient times signs and portents in the sky were attributed to the activities of the gods, but the Romans entertained the possibility of voyages to the moon and other worlds. Some modern authors point to descriptions of ‘fiery chariots’ and ‘pillars of cloud and fire’ from the Old Testament as evidence of UFO activity in ancient times. In Chariots of the Gods?, Erich von Daniken claimed that myths and legends concerning gods and angels were really descriptions of technologically advanced aliens who visited our world in the distant past. His book was first published in 1968, the same year Stanley Kubrik’s movie 2001: A Space Odyssey predicted the discovery of evidence of extraterrestrial life and suggested that intervention by alien intelligences may have occurred at an earlier stage of human evolution. In 1969 science fiction became science fact when Apollo astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk on the moon.

But the idea that explorers from other worlds visited Earth in the past and occasionally returned to keep a watchful eye on the human race was nothing new. Half a century before the moon landings, the American collector of curiosities, Charles Fort (1874–1932), speculated the human race was ‘property’. In his Book of the Damned, published in 1919, he wrote that: ‘… once upon a time, this earth was No-man’s Land, that other worlds explored and colonised here, and fought among themselves for possession, but that now it’s owned by something… all others warned off.’ Fort’s evidence was culled from accounts of unusual phenomena in the sky that he found in the archives of scientific journals and newspapers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He referred to this as ‘damned data’ because of the way the establishment attempted to explain away phenomena that could not be accounted for within the confines of existing scientific knowledge.

During the nineteenth century sightings of strange lights in the sky were occasionally recorded in the logbooks and journals of mariners and explorers. Sometimes these were reported officially to the British government. Charles Fort highlighted a sighting recorded in February 1893 by Captain Charles Norcock, commander of the corvette HMS Caroline, as evidence that Earth had been visited ‘by explorers from other worlds’. On a wintry evening, the ship was steaming from Shanghai towards the Sea of Japan when the watch officer called the captain to the deck and pointed towards the 6,000 ft height of Mount Auckland. Above the horizon, but in front of the mountain, appeared a formation of strange lights, ‘resembling Chinese lanterns festooned between the masts of a lofty vessel’. The lights first appeared as one mass, then spread out in irregular lines as they moved northwards. More curious lights were seen the following night from a different location. Capt. Norcock, using a telescope, described them as oval, red-coloured ‘globes of fire’ that hovered above the horizon in a massed group ‘with an outlying light away to the right’. Occasionally this would disappear and ‘the others would take the form of a crescent or diamond, or hang festoon-fashion in a curved line’. On arrival in the Japanese port of Kobe, the captain noticed a newspaper report which said ‘the unknown light of Japan’ had been seen by local fishermen ‘as was customary at this season when the weather is very cold, stormy and clear’. Norcock learned from the captain of another warship, HMS Leander, that his officers had also seen lights they thought were from a ship on fire in the same locality. They altered their course to assist but found the lights rose into the sky as they approached.1

Three decades earlier the British government set up the very first official inquiry into unexplained aerial phenomena. In 1865 the Board of Trade was asked to investigate the source of ‘mysterious lights’ that lured many ships to destruction on the coast of northeast England. In December of that year the losses became so great that a group of sea pilots and fishermen petitioned their MP for an inquiry. A commission led by Rear Admiral Sir Richard Collinson (1811–1883) arrived in Sunderland and took statements from coastguards, mariners and residents who had witnessed the lights. In testimony preserved at The National Archives, experienced crewmen described how they had been lured towards the shore by a revolving light or lights which they mistook for the lighthouse at the mouth of the Tyne. They did not realise they were mistaken until the ships struck treacherous rocks. Coastguards and fishermen told the inquiry similar lights had been seen over the coast near Souter Point for a period of 30 years, but never as frequently as during the winter of 1865–66. The commission was unable to find any evidence that ‘false lights’ had been deliberately lit by anyone who could profit from the wrecks. After the loss of 20 further vessels in 1869, Trinity House built a new lighthouse on Souter Point to guide ships to safety. The mysterious lights were never seen again.2

Although the phenomena seen over the Durham coastline and the Sea of Japan were just ‘lights’, there are also nineteenth century examples of circular and torpedo-shaped objects seen in the sky. For example, on 22 March 1870 the crew of the barque Lady of the Lake observed what they described as a ‘remarkable cloud’ rising into the sky during a cruise in the North Atlantic Ocean. The ‘cloud’ was circular, grey in colour and had a complex internal structure divided into four sections, the central dividing shaft beginning at the centre of the circle and extending far outwards. The mysterious ‘cloud’ was visible for half an hour and appeared to rise from the southern horizon. It disappeared in the northeast. In an entry taken from the ship’s log, Captain Frederick Banner noted the strange object appeared much lower than the other clouds and added: ‘It came up obliquely against the wind, and finally settled down right in the wind’s eye.’3

Apart from Charles Fort, few people in the ninenteenth century were prepared to speculate that Earth received regular visits from alien explorers. But journeys through the sky – and ultimately to other worlds – were now part of science fiction literature. Jules Verne’s 1865 book Round the Moon and its sequel From Earth to the Moon introduced the idea of travel by spaceship to a mass readership. Meanwhile, stories describing exotic aliens who lived on the moon and Mars were published by mass circulation newspapers. For instance, Benjamin Day caused a sensation in 1835 when his newspaper, the New York Sun, published a series on ‘Great Astronomical Discoveries’ that described plants and animals living on the lunar surface and humanoid creatures who flew with bat-like wings. Later in the century, Percival Lowell scrutinised the planet Mars from an observatory in Arizona and became convinced the Martian ‘canals’ were evidence the red planet was home to an advanced civilisation.

If intelligent aliens existed on Mars or elsewhere in the solar system, the next logical question was: were they friendly or hostile? When H. G. Wells discussed this question with his brother Frank, the two men wondered how humans would cope when confronted by a more advanced alien race. Frank drew parallels with the trauma experienced by the native people of Tasmania when they were colonised by Europeans. This remark gave Wells the inspiration for what is undoubtedly one of the finest science fiction novels ever written, The War of the Worlds.

The year before Wells’s book was published, there was a flood of sightings in North America of a ‘mysterious airship’ similar to those imagined in the books of Jules Verne. Many believed the airship was the product of an American secret inventor who was testing his flying machine in secrecy. Most of the sightings were of lights in the night sky but the ‘airship’ was also seen in daylight and was described as cigar-shaped, silver in colour and equipped with a variety of wings, sails and propellers. The airship wave began in California in November 1896 and the sightings spread eastwards. By the spring of 1897 hundreds of American citizens including police officers, judges and businessmen were quoted by newspapers as having observed the ‘mysterious airship’. These sightings, however, took place more than five years before the Wright brothers’ flimsy aeroplane took to the air at Kitty Hawk. Intriguingly, they also included many themes that would later turn up in the age of the modern UFO, including landings in remote areas, crashes that left behind strange pieces of metal inscribed with hieroglyphs and even encounters with airship crews. For example, one man in California claimed he had encountered a landed craft and its Martian crew, who tried to kidnap him and his companion.

The optimism and wonder that sustained the North American craze for seeing advanced flying machines similar to those imagined by Jules Verne was replaced in Europe by fear of invasion and attack from the air. In 1908 H. G. Wells’s novel The War in the Air predicted a future war in which German airships and aircraft would be used to bomb civilians in New York and other cities. In Britain Wells’s fiction appeared to take a step nearer to fact in the spring of 1909, when stories began to reach London of weird lights and cigar-shaped objects seen lurking in the heavens at night. Startling accounts soon appeared in the press. Among these was one volunteered by farmhand Fred Harrison from King’s Lynn, Norfolk, and published in the Daily Express on 14 May 1909. Harrison said: ‘I heard a whirring noise overhead, and when I looked up I saw that the fields round were lit up by a bright light. The light came from a long, dark object which was travelling swiftly overhead. It was low down – only a little way above the trees – so I could see it plainly… The searchlight lit up the road, the farm buildings, the trees and everything it touched, so that it was like day.’

Some reports came from respectable sources. One of the first was made by a serving officer of the Peterborough police force who was pounding the beat in the early hours of 23 March 1909. According to a story published in the Daily Mail two days later, PC Kettle heard ‘the steady buzz of a high-powered engine’ and on looking up saw a powerful light high up in the dawn sky and ‘a dark body, oblong and narrow in shape, outlined against the stars’.

It is not hard to imagine these accounts making headlines as the latest UFO or flying saucer sightings. In 1909 they were interpreted not as evidence of alien craft that had crossed vast interplanetary distances, but of enemy airships that had travelled to Britain across the North Sea. The monstrous German Zeppelin was less than a decade old but had in its various incarnations come to symbolise German technical superiority in the air. With rivalry between the two countries growing, these sightings were taken by some as incontrovertible evidence that Germany was spying on Britain from the air.

As with the late nineteenth century American sightings there were even allegations of ‘contact’, as found in the tale of the Cardiff man who encountered what he thought to be a landed airship on a remote hillside in South Wales. Mr Lethbridge, a Punch-and-Judy showman, was riding across Caerphilly Mountain late at night in May 1909 when he turned a bend and saw ‘a long-tube-shaped affair lying on the roadside’. Two men dressed in heavy fur-coats and caps were busy at work on their flying machine. As he approached they jumped up and ‘jabbered furiously to each other’ in a language he didn’t understand. Before he could say anything, the men (whom he assumed were German spies) jumped into a cabin beneath the airship, which then ‘rose into the air in a zig-zag fashion’. It disappeared towards Cardiff, showing two brilliant lights as it rose into the sky.4

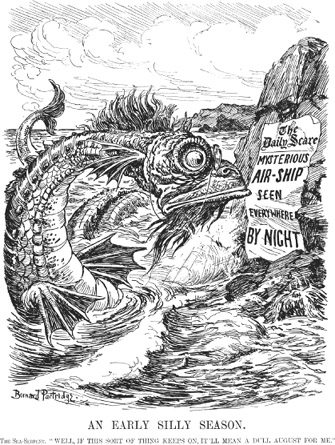

A Punch cartoon by Bernard Partridge published at the height of the ‘phantom airship’ scare in 1909

As headlines questioned ‘Whose is the airship?’, some members of the press used these alarming stories to pressurise the British government to increase spending on aircraft. Others asked ‘does it really exist or is it a figment of our imagination?’. It was, as many recognised at the time, highly unlikely that any extant German airships would have been capable of such a journey. After all, it was only in July 1909 that French aeronaut Louis Blériot completed his famous aeroplane crossing of the English Channel, a feat that led the newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe to proclaim ‘England is no longer an island’.

Sceptical journalists dubbed the nocturnal visitors ‘scareships’ and asked why they seemed to vanish at dawn. At 1,000 miles each way, the round trip from the Zeppelin hangars at Friedrichshafen in Germany to the east coast of Britain would also have been impossible to complete under cover of darkness and would have taken the giant airship over parts of Belgium and France in daylight, where it would have been seen by thousands of people.

Although the 1909 airship scare came to an end after a couple of months, more sightings would follow. In 1912 Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, presided over what could be called the first government inquiry into a UFO sighting over a sensitive military base. The future Prime Minister’s interest in this subject would resurface again when UFOs made headlines during the 1950s (see p. 43).

Winston Churchill in 1910. Two years later, as First Lord of the Admiralty, he ordered the first British government inquiry into a UFO sighting over Sheerness naval base in Essex. This UFO was suspected to be the German Zeppelin, the L-1. (COPY 1/543)

On 13 October 1912 a new naval Zeppelin, the L-1, set out on a 30-hour endurance flight from its base at Friedrichshafen in Germany. The 900-mile flight took the airship out over the North Sea; it then turned towards Berlin, where it landed at 3.45 pm on the following day. Just after sunset that afternoon, something was seen and heard flying above the port of Sheerness in Kent. The dockyards here were an important part of Britain’s defences and home to a Royal Navy torpedo school and naval flying station at nearby Eastchurch.

As the days passed, news of the Zeppelin flight over the North Sea reached the British government and the incident assumed a more sinister aspect for officials. On 25 October the director of the Admiralty Air Department, Murray F. Sueter, asked the Captain of the Royal Navy torpedo school to ‘make private enquiries’ to discover whether a Zeppelin really had visited Sheerness. Questioned in the House of Commons on 21 November, Churchill wrote: ‘I caused enquiries to be made and have ascertained that an unknown aircraft was heard over Sheerness about 7 pm… Flares were lighted at Eastchurch, but the aircraft did not make a landing.’ Questioned further as to whether he knew ‘where our own airships were on that night’, Churchill replied: ‘I know it was not one of our airships.’5

The outcry that followed publication of this story led Count Zeppelin to telegram the editor of the Daily Mail: ‘None of my airships approached the English coast on the night of October 14th.’ This was also the conclusion reached by airship historians. The Eastchurch sighting was followed by many others. During February 1913, for example, hundreds of people on England’s East Coast saw what they believed was the headlight of a ‘phantom Zeppelin’ cruising through the clear night sky. On the night of 25 February there were 37 separate sightings, including one by coastguards at Hornsea who reported their observations to the British Admiralty. Sceptics pointed out the scare coincided with a period when the planet Venus was prominent in the night sky after sunset and no evidence has been found that any of the German airship fleet actually visited the English coast during the winter of 1912–13. We are therefore left to wonder what was seen and heard above the torpedo school at Eastchurch and elsewhere as Britain found itself gripped by ‘airship mania’. Were people seeing bright celestial objects or simply imagining things?

Alarmed by reports of an airship, soldiers opened fire on the night sky on 10 August 1914. The first real Zeppelin air-raid on Britain took place five months later, in January 1915. AIR 1/561/16/15/62

In some cases it certainly seems that people might have been imagining things. One dramatic and slightly comic example, which can be found among the old Air Historical Branch files at The National Archives, happened near the Vickers shipyard at Barrow-in-Furness just days after the outbreak of the First World War. Although the first real German air raid against England by Zeppelins did not occur until January 1915, the War Office was inundated with reports before then; with widespread fear of imminent attack from the air, every light in the sky was transformed into an enemy airship.

The Vickers shipyard in Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria, like Sheerness, was of great military importance and was guarded by the only anti-aircraft gun on the west coast. Sentries were posted around the dockyard with orders to open fire on anyone who did not answer their challenge. Late on the night of 10–11 August, Major Becke, Commander of the Barrow Defences, stated that two, or possibly three, airships had been seen during the night flying over the Vickers yards and had been fired upon by the anti-aircraft gun without effect.

In a detailed description of events, Lieutenant W. Adair of the 5th Border Regiment based at nearby Sowerby Lodge tells how his men had seen two cigar-shaped craft travelling at great height in a northerly direction, their shapes lit up by the glare from the ironworks. At midnight, sentries at Sandscale spotted another light and opened fire with their machine guns. Alongside the excitable statements from those who saw something or fired into the night sky was one from the men’s commanding officer who, having heard shots found them: ‘… gazing at a bright star; small clouds were flitting over this star and darkened it to some extent. I thought myself that the men had been deceived, as I could see nothing in the shape of an aircraft.’6

Elsewhere in the same Air Historical Branch file is a more troublesome account from the end of 1914, which was recorded by the crew of a Hull trawler – the SS Ape –the night before the German High Seas fleet bombarded the east coast ports of Scarborough and Whitby. In a statement to an intelligence officer, the ship’s master described how his ship was steaming towards Yarmouth at 4.10 pm on 15 December when the crew sighted ‘a black object astern which gradually drew nearer’. They saw the airship turn and head towards the Lincolnshire coast, where it vanished in the haze and fog.

Alone among the many reports of airships from the first year of the war this was recorded in the official history as ‘proved to be founded on fact’. However, we now know that a German airship could not have been responsible for this sighting. Airship war diaries examined by historian Douglas Robinson show that weather conditions were so atrocious on 15 December 1914 that none of the German naval airships were able to leave their sheds on the Continent.7 And as with earlier sightings, any German airship making its way to these shores would surely have been seen somewhere by someone as it crossed mainland Europe.

Extract from a military intelligence file listing reports of ‘suspected aircraft’ reported to the Chief Constable of Cumberland in August 1914, on the outbreak of the First World War. AIR 1/565/16/15/18.

Whatever visited England in darkness during the first months of the war, it could not have been a Zeppelin. So what was being seen? During the 1909 wave it emerged that jokers had successfully fooled at least some witnesses with lighted box-kites and fire-balloons. Indeed, as recently as 2009, fleets of Chinese lanterns – lit by tiny candles – have tricked people into thinking they were seeing UFOs. Could the same be said in 1912 and 1914? Were these strange sightings just balloons and bright stars transformed by fear and anxiety into something more threatening? Whether or not this was the explanation, these early sightings are undoubtedly direct precursors of the UFO scares that would follow in the modern era.

The most important ‘phantom airship’ sighting recorded in the official history of German air raids stands apart from others made at this time and also counts as the first encounter with a UFO reported by a British military pilot. On the night of 31 January 1916, the crews of nine German Navy Zeppelins left their sheds on the Continent with orders to attack Liverpool, with London as a secondary target. In the event, the plan was thrown into chaos by poor weather conditions of freezing rain, snow and thick ground mist. This hid much of the countryside from the air and made accurate navigation impossible. In the confusion that followed, several towns in the Midlands were bombed leaving 71 people dead and 113 injured.

During the raid, the War Office was able to plot the course of all nine raiding airships. From the maps they produced it appears that none of the raiders reached London or the Southeast of England, but at least one of the raiders initially turned south after crossing the East Anglian coastline at 7.00 pm. The War Office calculated that if that course were held, the Zeppelin would be over London within one hour and aircraft defending the capital were ordered to intercept them.

Shortly before 8.30 pm two Royal Flying Corps pilots flying B.E.2c biplanes reported pursuing moving lights at 10,000 ft above Central London. Both lost their targets in cloud, and it seems possible they had actually spotted lights on each other’s planes. But another sighting by a Royal Navy pilot is much more difficult to explain.

At 8.45 pm Flight Sub-Lieutenant Eric Morgan took off from the Royal Naval Air Service station at Rochford in Essex and began to patrol at 6,400 ft when his engine started misfiring. At this point he saw a little above his own altitude and slightly ahead to his right, about 100 ft away from his plane, ‘a row of what appeared to be lighted windows which looked something like a railway carriage with the blinds drawn’. Assuming he had come face to face with a Zeppelin preparing an attack upon Central London, Morgan drew his Webley & Scott pistol and fired. Immediately, ‘the lights alongside rose rapidly’ and disappeared into the inky blackness, so rapidly in fact that Morgan believed his own aircraft had gone into a dive. He battled to bring his plane under control and was forced to make an emergency landing on the Thameshaven Marshes.

An account of Morgan’s sighting, described as ‘an encounter with a phantom airship’, appears in Captain Joseph Morris’s official history The German Air Raids on Great Britain 1914–18, published in 1925 and based upon then classified records. Morris refers directly to the airman’s report filed with the Admiralty, but this report is not mentioned in the official account of the 31 January 1916 raid published by the War Office which charts the flight paths of the Zeppelins and the attempts by British fighters to intercept them. As a result, historians have been left with the impression that the authorities gave no credence to it.

There was in fact a story from a fourth pilot, Flight Sub-Lieutenant H. McClelland, who reported seeing what he described as ‘a Zeppelin’ caught briefly in the glare of searchlights above London at 9.00 pm, 15 minutes after Morgan’s encounter. It disappeared as he closed the distance. His report was forwarded to the Admiralty where the Third Sea Lord, Rear-Admiral F.C.T. Tudor, dismissed it with the comment: ‘night flying must be difficult and dangerous, and require considerable nerve and pluck, but this airman seems to have been gifted with a more than usually vivid imagination.’8

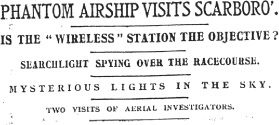

Like many others, this article from the Scarborough Daily Post, published 20 February 1913, explained the airship sightings by suggesting Britain was under ‘systematic surveillance from the skies by the aerial spies of a foreign Power.’

Phantom Zeppelins were not the only phenomena that authorities struggled to explain during the First World War. Given the widespread belief that German spies were active in Britain in large numbers, they found themselves carrying out a number of investigations into things that might have been ignored during peacetime. Most obvious of these are the stories of moving lights that began to reach the War Office and which, it was feared, could reveal attempts to communicate with German ships or aircraft from the ground via sophisticated flares.

During the period 1915–16, for example, the Royal Navy base at Devonport began to receive accounts of mysterious lights seen on Dartmoor. Among the Admiralty records at The National Archives is a statement signed by Lieutenant Montague Elliott, Commander-in-Chief, Royal Naval Reserve, Devonport, which mentions ‘countless reports’ describing a ball of light that ‘is seen to rise perpendicularly from the ground to a height of anything from 30 to 60 feet’.9 These sightings caused great concern and attempts were made by intelligence officers to capture this ‘floating light’ by staking out parts of bleak Dartmoor late at night.

An extraordinary account of one such operation is contained in the same file. Lieutenant-Colonel W.P. Drury was the garrison intelligence officer at Devonport and in late December 1915 he questioned a number of civilians living in the Ashburton area who had seen mysterious lights moving over Dartmoor in the early hours. One of these was a Mrs Cave-Penny who lived in an isolated farm that commanded an excellent view of the moors around Hexworthy Mine. She and her daughter reported seeing on several occasions ‘a bright white light rise from a point a few hundred yards to the East of the mine’, which swung across the valley and disappeared. ‘The light sometimes rose above the skyline, at others it showed against the loom of Down Ridge on which the mine is situated’, Drury’s report stated. ‘On each occasion it rose from the same spot and followed the same course.’

Alerted to this regular occurrence Drury obtained permission to stake out three locations where the lights had been sighted. After several night-time visits he saw the phenomenon himself. At 9.30 pm on 4 September 1915 Drury and another intelligence officer began watching Dartmoor from a hiding place opposite the main Totnes–Newton Abbot road. His report describes how suddenly: ‘… we observed a bright white light, considerably larger in appearance than a planet, steadily ascend from the meadow to an approximate height of 50 or 60 feet. It then swung for a hundred yards or so to the left, and suddenly vanished. Its course was clearly visible against the dark background of wood and hill, though, the night being dark it was not easy to determine whether it was a little above or beneath the skyline. We were within a mile of the light and both saw its ascension and transit distinctly.’

Unfortunately for their operation, the River Dart lay between the two men and the mysterious light and there was no bridge or ford where they could cross to reach the meadow from which it appeared to rise. Unable to solve the mystery, Drury completed his report on a note of disappointment: ‘… I have watched Down Ridge, Dartington Manor, and Barton Pines by night on several occasions before and since September 4th, but that date is the only time I personally have seen this ‘floating light’ which has so often been reported by other and reliable witnesses… ’10

Three months later GHQ Home Forces issued a 16-page confidential report on the outcome of their investigations into hundreds of similar reports of lights in the sky that had been widely attributed to German spies. This concluded there was ‘no evidence on which to base a suspicion that this class of enemy activity ever existed’ and said around 89 per cent of the reports had been explained. In this report one group of sightings is categorised as ‘moving lights in the air’ and states: ‘These lights are often difficult to explain satisfactorily. The planets and very bright stars have frequently given rise to these reports… [and] in one case there are grounds for believing that these lights have been based on the hitherto improperly observed phenomena of marsh gas or ‘ignis fatuus’.11

This conclusion is less than convincing as it invokes one unexplained phenomena to explain another. Ignis fatuus (‘foolish fire’) is also known, in English folklore, as the ‘Will-o’-the-Wisp’ or ‘Jack-o’-Lantern’. It is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘a phosphorescent light seen hovering or flitting over marshy ground’. In the past the elusive movements of these lights led observers to believe they were controlled by a mischievous spirit that led travellers astray in the dark. Although formerly a common night-time phenomenon in rural parts of the British Isles, sightings have been exceedingly rare in modern times. From at least the eighteenth century, chemists believed that methane produced by rotting organic matter could spontaneously ignite to create incandescent lights that, after dark, might appear to rise into the air. But more recent studies, such as that published in 1980 by chemist Dr Alan Mills from Leicester University, concluded that any bubbles of marsh gas that did ignite would create a dim glow at ground level and would be short-lived.12 This phenomenon could not explain sightings of brilliant lights that rise into the sky or follow a regular flight path, such as those described by the observers during the First World War. The Dartmoor sightings also resemble the stories of ‘false lights’ seen over the Durham coastline during the 1860s, which behaved in a similar elusive fashion. Again these reports triggered an official inquiry. Were both describing a similar phenomenon?

The mysterious floating lights seen over Dartmoor during the First World War were never satisfactorily explained, but official interest in reports of this kind largely came to an end after the war. One quite surprising group did, though, continue to collect accounts of unusual lights in the sky: scientists working for the Meteorological Office who were trying to understand ball lightning.

Ball lightning is often described as an incandescent sphere and is usually, but not always, seen in the sky during thunderstorms. Unlike fork or sheet lightning, which lasts for seconds only, those who have experienced ball lightning sometimes claim it is visible for minutes.

It was first recognised as a distinctive phenomenon in 1886, but stories describing lightning balls of considerable size and power can be traced back many centuries. One of the best-known historical accounts comes from Widdecombe-in-the-Moor, on Dartmoor. During a great thunderstorm there on 21 October 1638, a ‘great fiery ball’ entered the church and split into two. One fireball escaped through a window while the other vanished, leaving behind it a foul odour of sulphur and thick smoke. The building was partly destroyed by the blast; four parishioners were killed and 60 injured.13

In 1921 the Meteorological Office, at that time part of the Air Ministry, received a spectacular account of ball lightning seen over St John’s Wood, North London, during a severe storm on the evening of 26 June. A lady letter writer said she was watching the extreme weather over the capital from her window, which faced southeast. Without warning, at 2 am, she suddenly saw a fireball in the sky. Her account read: ‘It appeared as an incandescent mass floating in the atmosphere below the clouds. It was pear-shaped, the greatest width being equivalent to three moons, the height to four or five.’14 She was unable to say how far away the fireball was, but her account suggests it must have been of enormous size. This light in the sky was visible for at least two minutes, because she had time to walk to a friend’s room and rouse her before it vanished.

Her account fascinated meteorologists at the Air Ministry and they decided to launch an inquiry. Within days a press release was sent out to the national newspapers appealing to anyone who had seen ball lightning ‘and related phenomena’ to contact the Meteorological Office. The results of this inquiry survive in an extraordinary file at The National Archives containing over 100 letters and questionnaires completed by members of the public who responded to the appeal. One of those who filled in a questionnaire was Mrs Phillis Coe from Enfield, Middlesex, who appeared to have seen the same fireball. She wrote: ‘… I observed in an easterly direction a long, incandescent mass apparently floating just beneath the clouds and to all appearances stationary. This mass seemed to dilate and contract as it floated during the 10 or 15 minutes I watched it. The sight was so extraordinary that I awoke my husband and drew his attention to it, but we were both unable to account for the phenomenon and although we questioned several people afterwards we could not trace anyone who had seen it.’15

While some correspondents described seeing the fireball over London on 26 June, the Meteorological Office also received descriptions from people who had seen similar things at different times. And this is where the file becomes particularly intriguing. Annie Baker, for example, of East Southsea, Portsmouth, had read of the ‘strange ball of fire’ seen over London and wrote to tell what she had seen during another thunderstorm in the last week of July 1921. In her letter she described how: ‘… in the early hours… about 2 o’clock [I saw] a strange-looking bladder-like monster the shape of an airship only much wider. It quite startled me. I called to my husband to look at it, but knowing I am a bit nervous about thunderstorms, he did not get up. Well, it flickered very much, it was certainly [on] fire inside it, and looked as if it were going to burst. It was quite stationary for a few minutes, but thank goodness it passed away and disappeared quickly… ’16

More dramatically, a woman from Waterford in Ireland wrote to say that while she had not seen the fireball in St John’s Wood, she thought she might have seen one back in 1912. At the time she had been out on a night-time winters walk when ‘without any warning, a huge ball of light appeared through the clouds.’ According to her letter it remained stationary for about a minute before going up into the clouds again. About five minutes afterwards she heard a loud explosion out at sea. Echoing the contents of letters that would later be sent to the Ministry of Defence by many UFO witnesses, she asked: ‘This has often puzzled me and I would be glad if you could tell me what it was.’

Of the 115 letters and questionnaires received by the Air Ministry in 1921, just 65 appeared to describe the phenomenon of ball lightning. The remaining accounts included some truly bizarre examples that appeared when no thunderstorms were present. One story in this category was submitted by a man in Scotland who described something that had happened to him as a child in 1898. ‘I remember to this day,’ he wrote, ‘whilst coming home from school I saw a great ball of lightning about the size of a football, only it was flat as a coin and white. It would have put you in mind of a full moon high up in the heavens. But what made me write to tell you about this was that it was so low I could have thrown my cap and hit it. I ran after it and followed it for about 10 yards. Then, travelling very fast, it vanished.’17

The results of the inquiry were published by the geophysicist Harold Jeffreys in The Meteorological Magazine during September 1921. In his paper Jeffreys describes how he tried and failed to find a common denominator in the accounts collected by the Meteorological Office, noting ‘… the definitely unusual objects reported included a lunar halo, a miniature tornado and a very fine will-o’-the-wisp’. As we have seen, 50 of those who responded to the questionnaire had seen lights in the sky at different dates and times, which were possibly not ball lightning at all. Even among those who described seeing what the Meteorological Office did categorise as ball lightning there was little agreement on its size or the length of time that it was visible. Some said the fireball they saw was between 3 in and 1 ft in size. Others described a light high in the clouds that they compared with the disc of the full moon. Jeffreys recognised this meant the diameter of ball lightning could be as small as a few inches, or as large as 60 ft, but few observers were qualified to make such precise judgements.

Similarly diverse and contradictory were the time estimates. Some ranged from less than 10 seconds to between 1 and 5 minutes. Likewise, colours described by observers ran from bluish-white to deep red, but the great majority were reddish or yellowish. Shapes described were usually spheres, but several described pear-shaped and elongated objects resembling Zeppelins, similar to the reports of ‘phantom airships’ seen during the First World War. Most reported seeing single objects but one described ‘the appearance of three balls simultaneously, coming from a church spire at a point where it had been struck by an ordinary flash’. When it disappeared, ball lightning was usually silent. Sometimes the phenomenon faded gradually, while others burst and vanished suddenly.

A letter sent to the Air Ministry Meteorological Office in 1921 by a woman who saw ‘a strange looking bladder-like monster’ in the sky during a thunderstorm. AIR 2/205

Surveying the evidence, Jeffreys pondered ‘an extraordinarily variable phenomenon’, noting that it seemed impossible that any two correspondents had seen the same thing.18 Similar conclusions have been reached in official investigations of UFOs in later decades, which suggests that observers are actually reporting many different types of phenomena, all of which could have different origins. During the Second World War more sightings were reported, including many by pilots flying combat missions over Europe and the Pacific. UFOs and flying saucers were still unheard of, but American pilots had another phrase to describe them: foo-fighters.

On the evening of 26 April 1944 Flight Lieutenant Arthur Horton taxied his Lancaster bomber onto the runway at RAF Mildenhall, Suffolk, in preparation for a raid on Essen, deep in the steel-making German Ruhr valley. It was, he thought, just another routine, if terrifying, mission for 622 Squadron crews.

The raid went exactly as planned despite the potentially fatal distractions of Luftwaffe night-fighters and the flak that sought them out amongst the searchlight beams. Bombs dropped, Horton’s Lancaster turned for home. Then, shortly after leaving the target, his intercom crackled into life with a warning from the rear-gunner. Some odd lights had appeared out of the darkness and were following the plane. Horton asked the gunner if he was certain. Yes he replied, four orange balls of light were tailing them, two on each side of the aircraft, accelerating in short powerful spurts. According to the worried gunner they were about the size of large footballs and had a fiery glow to them. Another thought he could see small, stubby wings and possibly an exhaust glow from the rear of the objects. Now Horton was getting worried. Some 43 years after the event, Arthur Horton clearly recalled exactly what he did next: ‘… I immediately dropped the aircraft out of the sky. My gunners didn’t know what they were. Should they fire? By this time I was standing the aircraft on its tail and beginning a series of corkscrews and turns with the things following everything I did – but making no move to attack us. By this time we had the throttles “through the gate”, the gunners still asking what they should do. Apart from flying the thing I had to try and answer them. But were they some form of flying contraption that would explode at some specific distance from us, or on contact? Did they want us to fire at them to cause an explosion? Out of the kaleidoscope of thought the only answer was “If they are leaving us alone, leave them alone”.’19

An example from RAF files of ‘rocket phenomena’ reported by aircrew from RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War. These mysterious UFOs were described as ‘foo-fighters’ by US Army Air Force crews. AIR 41/2076

Horton’s term ‘through the gate’ refers to a technique by which Lancaster pilots could move the throttle sideways and forwards, breaking a wire, ‘the gate’, in the process. This would give considerable extra power, but put an immense additional strain on the engines. Horton continued evasive action for 10 minutes, during which time all the crew except him and the bomb aimer could see the pursuing balls of light. Whatever the objects were they stayed close to the Lancaster, duplicating its every move, until they reached the Dutch coast when, in the words of one of the gunners, ‘they seemed to burn themselves out’.

Exhausted but relieved, Horton flew the Lancaster safely back to England. His attempts at evasive action had caused a serious mechanical fault that forced the crew to land at a different airfield. Horton and his crew were baffled by the experience, and could only presume they had been chased by a German secret weapon, perhaps a radio-controlled anti-aircraft rocket. Upon reporting their experience to the intelligence officers at debriefing, they were met not with interest but ridicule. Nevertheless, Horton stuck to his account and would not be persuaded that he and his crew had imagined the experience.

Although Horton stated that he had never heard of any similar stories at the time, his description is entirely consistent with those of aircrews of other nationalities during the Second World War. American bomber crews coined the phrase ‘foo-fighters’ in or around 1943 to describe the strange moving balls of fire that pursued their aircraft during nighttime raids over Germany. No-one is certain where it came from but it may have originated in a popular 1940s US cartoon strip featuring a madcap fireman, Smokey Stover, whose catchphrase was ‘where there’s foo, there’s fire’. Alternatively ‘foo’ may come from the French word for fire (feu) as the phenomenon was often being described as resembling a fireball.

Whatever its origin, while ‘foo-fighter’ was a term familiar to aircrew serving with the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), it would have been unfamiliar to RAF pilots who observed similar lights during missions over Europe. Their reports were referred to by the Air Ministry as ‘night phenomena’ and ‘balls of fire’. Research by my colleague Andy Roberts has revealed that individual RAF aircrew developed their own terminology for UFOs they saw during combat missions. Based on information gleaned from interviews with surviving aircrew and accounts from personal logbooks, he discovered ‘The Light’, or ‘The Thing’ was used by RAF crews from 1942. The latter was the one Horton employed.

A number of baffled aircrew tried to rationalise their experiences as evidence of advanced Axis secret weapons or guided ‘rockets’, referring to them in those terms in flight logs and debriefings, but evidence soon emerged that the phenomenon was being observed by men on all sides. Dr R.V. Jones, director of intelligence for Britain’s Air Staff during the war, later said the Air Ministry was unable to explain the reports it received, ‘and when we asked German night-fighter crews they said they had seen them as well’.20 Similar reports were also made by aircrew in the Far East theatre of war, and one classic photograph appears to show ‘foo-fighters’ accompanying a flight of Japanese Takikawa-Kawasaki 98 fighters over the Suzuka Mountains during 1945.

A photograph said to show ‘foo-fighters’ and Japanese fighter aircraft over the Suzuka Mountains in 1945.

In the First World War, the British government was led to pour scarce resources into the investigation of phantom airships and mysterious ‘floating lights’ in case it offered evidence of enemy activity. In the Second World War, the allies investigated foo-fighters for exactly the same reason. Air Ministry and USAAF inquiries during the Second World War reached similar conclusions to the GHQ study in 1916.

Allied Air Intelligence had access to a wealth of information on all kinds of unexplained radar trackings and reports of ‘mystery’ aircraft and unusual rockets and flak. Each sighting was carefully analysed in the context of known weaponry, enemy tactics and the psychological problems of misperception. A report by the military intelligence branch MI 14, circulated in December 1942, discounted the idea that such phenomena could be remote-controlled Nazi weapons and dismissed most reports as ‘freaks’. For his part, R.V. Jones recalled that ‘we tended to interpret them as either aberrations under the stress of operation, or misinterpretations of some phenomena or other’.21

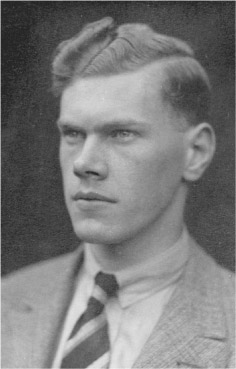

Dr (later Professor) Reginald Victor Jones was director of intelligence for the Air Ministry during the Second World War. Later, as head of scientific intelligence at the Ministry of Defence, he became involved in the investigation of the UFO mystery.

Dr Jones’s conclusions are echoed in the words of the late Goon Show star Michael Bentine, who served as an intelligence officer in RAF Bomber Command during 1943–4. In a 1992 interview he described debriefing several crews who had seen unidentified lights in the sky during raids on the Baltic coast. ‘They fired at the lights, which didn’t shoot back. These lights didn’t seem to do anything, just pulse and go round. We put it down to fatigue, but later, after I had sent the reports in, an American G2 Intelligence Officer told us that their bombers saw lights in the sky – “foo-fighters” he called them.’22

Bentine also described how he debriefed a Polish bomber unit based in England. They claimed that silver-blue balls appeared near their wing on six missions during the autumn of 1943. These tailed the planes as they raided the Nazi V-weapons base at Peenemunde. The crews told Bentine it must be a new weapon. ‘But what did it do to you?’ Bentine inquired. ‘Nothing,’ they replied. ‘Well it was not a very effective weapon, was it?’ he pointed out. Bentine’s last statement accurately sums up the conclusions reached by the Air Ministry and USAAF during their study of these phenomena. Whatever the foo-fighters were, they did not appear to pose a threat to aircraft.

‘Churchill feared panic over UFOs’ screamed newspaper headlines in August 2010 after The National Archives released 5,000 pages of information from the MoD’s UFO files. Of the hundreds of reports, letters and drawings contained in those files one was singled out for international media coverage, all because of the alleged involvement of Britain’s wartime Prime Minister.

The substance of the story was a letter from a scientist in Leicester sent to the MoD in 1999 who claimed that, in the middle of the Second World War, Churchill ordered the cover-up of an encounter between a UFO and a RAF bomber crew.1 The story told by the anonymous scientist was that sometime during the early 1940s, whilst returning from a mission over Europe, a RAF reconnaissance aircraft was ‘intercepted by an object of unknown origin.’ The metallic object appeared suddenly at the side of the aircraft as it approached the English coast, hovered noiselessly for a time whilst matching its course and speed, then accelerated away at high speed. During this close encounter, photographs were taken by at least one crew member.

The letter writer claimed he was the grandson of a RAF officer who was ‘part of the personal bodyguard’ of the PM during the Second World War. His grandfather was present during a discussion between Churchill and Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the Commander of Allied Forces and future US President, when the incident was discussed. At the meeting, a scientific adviser ‘dismissed any possibility that the object had been a missile’ and when another raised ‘the possibility of an unidentified flying object’, Churchill declared the incident ‘should be immediately classified for at least 50 years and its status reviewed by a future Prime Minister’. According to the story Churchill believed a cover-up was necessary because its release: ‘… would create mass panic amongst the general population and destroy one’s belief in the church.’

Although this story was just one of hundreds of similar rumours and legends that found their way into the correspondence files of the UFO desk, the writer pleaded ‘not to dismiss my attempts to pursue this matter as trivial or motivated by “crackpot” thinking’. In response he was told by MoD that ‘we know of no closed records from World War 2 on this subject’ and most UFO files before 1962 had been destroyed due to their mundane content.

When examined closely, the story resembles an urban legend, told by ‘a friend of a friend’, a type frequently found in UFO literature. The letter writer reveals that his grandfather died in 1973, so the information was not first hand, or even second hand. He says that, fearful of his obligations under the Official Secrets Act, his grandfather mentioned the incident only once to his daughter (the writer’s father) when she was nine years old. In 1999 she saw a TV programme on UFOs ‘which featured an interview with a former RAF airman who described a similar (or the same) event’. This prompted her to reveal the anecdote to her son. Equally questionable is the reference to ‘unidentified flying objects’ made by Churchill’s adviser in the story. As the phrase ‘UFO’ was invented by the USAF in 1950 (see Chapter 2), it would not have been used in a wartime context a decade earlier.

Although the basis for the story is hearsay, it may still contain a grain of truth. Winston Churchill’s famous 1952 memo that demanded to know ‘the truth about flying saucers’ is a matter of public record (see Chapter 2). Churchill was an old man during his final term of office as Prime Minister. His private secretary, Sir Anthony Montague-Browne, assured me that his interest in UFOs was ‘purely ephemeral… he wanted to know the facts in case he was questioned in Parliament. That was all.’ Nevertheless, his interest in the unsolved visit by a ‘phantom airship’ to Sheerness before the First World War (see p. 6) suggests that he was well aware of the potential threat posed to national security by unidentified flying objects, alien or otherwise, at periods of international tension. Files at The National Archives reveal that during the Second World War both the British Air Ministry and the US Army Air Force collected and studied unusual sightings reported by aircrew. Details of some of the more reliable sightings were passed up the chain of command and reached top brass at HQ Bomber Command. Given the concern within Churchill’s War Cabinet about Nazi secret weapons, air intelligence were alert to any evidence of new technology from the theatre of war. It is possible that a discussion about one of these wartime experiences was overheard by someone during the war and, repeated years later to a nine-year-old child, became transformed into yet another UFO legend. We will never know for sure.

A parallel mystery to UFOs encountered in the air is that of UFOs tracked on radar, something that is often a key element of modern accounts. Even before news of the first sightings of foo-fighters reached the Allies, operators had been perplexed by strange blips that appeared and disappeared on their screens as they controlled aircraft movements. Sometimes these appeared to move at incredible speeds, faster than any man-made aircraft of the day.

Radar was developed by British scientists during the 1930s as an early warning system against German bombers. Before the outbreak of war the Air Ministry secretly built a string of radar stations, known as Chain Home or CH, along the east coast of England that was to provide a crude first warning of German air raids. In 1940, during the Battle of Britain, this ‘secret weapon’ gave the RAF a crucial tactical advantage over the superior strength of the Luftwaffe. Although at this time Britain’s air defence system was the most advanced in the world, radar itself was far from foolproof, as demonstrated by a series of strange incidents the following year.

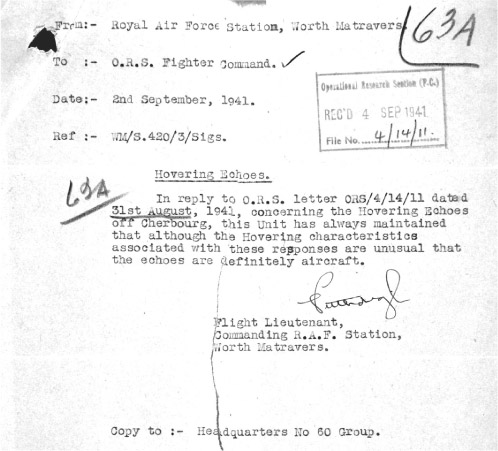

Extract from an Air Ministry file on mysterious ‘hovering echoes’ tracked over the English Channel by RAF radars during 1941. Senior officers initially believed these were part of a German invasion force, but fighters sent to investigate found nothing. AVIA 7/1070

Late on the night of 20 March 1941, with the threat of a German invasion still strong, RAF Fighter Command was placed on alert when the CH system reported an attack on Britain’s south coast. Records at The National Archives show that up to five separate stations saw what seemed to be a massive formation of blips moving slowly across the channel precisely as would be expected if a massive night raid by German bombers was under way. As tension grew, the blips approached from the direction of the Cherbourg peninsula until they reached a point 40 miles from the Dorset coast when they faded from the screen. The following night the blips returned and for a period of weeks CH stations continued to report both mass formations and individual echoes. Senior officers began to fear these could be part of a sophisticated German plot to jam British radar with false signals as aircraft or towed gliders prepared for a real invasion.23

A few years ago I had the opportunity to discuss these weird incidents with Sir Edward Fennessey CBE, who served on the RAF scientific staff responsible for the CH radars during the war. Sir Edward, who died in 2010 at the age of 97, said the radar sightings were taken seriously as the RAF was expecting a German invasion. ‘Immediate orders were given to intercept, but when fighters were in position to intercept no targets could be found. Ground radar continued to plot the targets and we urgently contacted the Radar Research Station (TRE) then based in Swanage. They suggested various adjustments to the CH to eliminate false plots, but [they] remained tracking towards England until after some time they faded.’24

After the war Sir Edward told this story at a dinner party where he entertained guests with his theory that the echoes were really guardian angels, ‘the souls of British soldiers killed in France over the centuries returning to defend their country’. Although it was intended as a joke, this idea caught the imagination of serving airmen who were regularly seeing ‘ghosts’ on their radar screens: they called them ‘radar angels’.

During the Second World War, Sir Edward recalled that no explanation was ever found for radar angels and pointed out that ‘busy fighting a war, we spent no time investigating this phenomena’. However, as in the First World War, the government sometimes did feel forced to act. By 1945 so many puzzling foo-fighter reports were reaching the Allies that scientific intelligence officers attached to Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), commanded by the US General Dwight D. Eisenhower, were asked to investigate. In February 1945 British officers attached to SHAEF told the Air Ministry: ‘… it would seem that there must be something more than imagination behind the matter, and in view of the fact that pilots and crew are becoming slightly worried by them, it is considered that everything possible should be done to get to the root of the matter.’25

Responding on 13 March, Group Captain E.D.M. Hopkins of the Air Ministry said intelligence officers in London had carefully studied the sightings. They decided, ‘a few of the alleged aircraft may have been Me 262 [Luftwaffe jet fighters] and for the rest, flak rockets are suggested as the most likely explanation’. He added: ‘The whole affair is still something of a mystery and the evidence is very sketchy and varied so that no definite and satisfactory explanation can yet be given.’26

The one consistent feature that concerned the Allies was that foo-fighters paced and followed aircraft in a controlled, seemingly intelligent manner. At the time, the Allies knew the Germans were experimenting with a host of unorthodox weapons, including jet aircraft such as the Me 262 and futuristic-looking bat-wing-shaped ‘flying wings’. When the allies overran Nazi Germany in 1945 they captured a number of designs for advanced aircraft, but they found the Axis forces did not have the capability to produce guided weapons that could twist and turn whilst following an aeroplane and certainly not for the lengths of time reported.

During this period, a scientific intelligence officer serving with SHAEF called Bob Robertson carried out a study of foo-fighter sightings reported by American aircrew. Robertson was a friend of Britain’s R.V. Jones and was an eminent physicist in his own right. After the war, in his role as a scientific adviser to the CIA, Robertson was asked to convene a secret panel to examine any potential threat posed by UFOs to national security. Although copies of his wartime foo-fighter study have not survived, Robertson summarised his findings for the panel on UFOs that he convened in 1953. In his report he described foo-fighters as: ‘… unexplained phenomena sighted by aircraft pilots during the Second World War in both European and Far East theatres of operation, wherein “balls of light” would fly near or with the aircraft and maneuver rapidly. They were believed to be electrostatic (similar to St Elmo’s Fire) or electro-magnetic phenomena or possibly light reflections from ice crystals in the air, but their exact cause or nature was never defined.’27

The Roberston panel concluded, as Michael Bentine had done in 1943, that foo-fighters were ‘unexplained but not dangerous’. Once it had been ascertained that these UFOs did not explode, open fire on Allied aircraft or display aggressive characteristics, Air Intelligence was content to let the matter drop, maintaining a watching brief. There was a war on and they could not afford to waste time and money chasing phantoms of the skies. Both Bob Robertson and Dr R.V. Jones remained interested in reports of unexplained phenomena and would eventually play significant roles in official investigations during the post-war UFO era. But Robertson clearly was not happy to dismiss the sightings just by giving them a name and he observed that: ‘if the term “flying saucers” had been popular in 1943–45, these objects [foo-fighters] would have been so labeled.’28

Witness accounts and documentary evidence indicate the majority of foo-fighter sightings were of small spherical objects. Some seem similar to the accounts of ball lightning sent to the Meteorological Office in 1921. Indeed more recently there have been accounts of ball lightning pursuing and even entering aircraft during storms. However, among the testimonies of pilots in the Second World War, there are a few stories describing large, apparently structured objects.

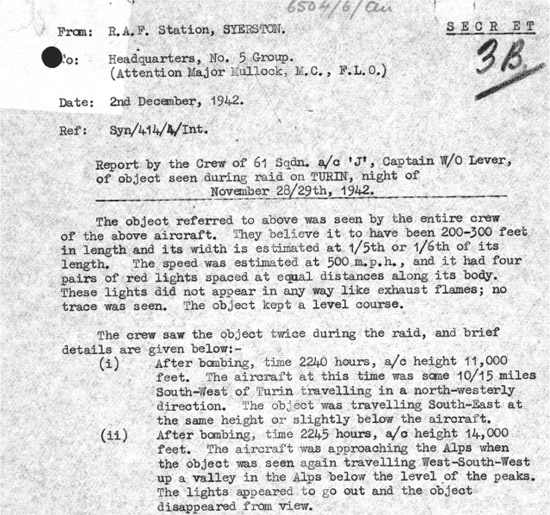

During the Second World War, the Air Ministry collected a number of reports of ‘rocket phenomena’. This extraordinary example was made by a bomber crew during a raid on Turin on the night of 28/29 November 1942. AIR 14/2076

One extraordinary example can be found in the Royal Air Force files at The National Archives with ‘Secret’ stamped on it. At the time it was judged to be of such significance that details were sent directly to the headquarters of RAF Bomber Command with a covering letter from the Air Vice Marshal of No. 5 Group, RAF, which read: ‘… Herewith a copy of a report received from a crew of a Lancaster after a raid on Turin. The crew refuses to be shaken in their story in the face of the usual banter and ridicule.’29

The report describes an aerial object seen by the entire crew of a Lancaster bomber during a bombing raid on Turin, northern Italy, during the night of 28/29 November 1942. Twice during the raid Captain Lever and the crew of the Lancaster from 61 Squadron, based at Syerston in Lincolnshire, saw an object 200–300 ft in length that travelled at a speed they estimated at 500 mph. They said it had four pairs of red lights spaced at equal distances along its body and flew on a level course. When first seen, after the bombing at 10.40 pm, it appeared to be 10 or 15 miles southwest of the city travelling at the same height as the Lancaster. Five minutes later as the Lancaster approached the Alps at 14,000 ft, the crew saw it again, travelling in a southwesterly direction up a valley but above the mountain peaks. It disappeared when the red lights it carried went out.

The report concluded by stating that ‘[Captain Lever] has seen a similar object about three months ago north of Amsterdam. In this instance it appeared to be on the ground and later travelling at high speed at a lower level than the heights given above along the coast for about two seconds; the lights then went out for the same period of time and came on again, and the object was still seen to be travelling in the same direction’.30

It is difficult to know what to make of this sighting. RAF Bomber Command was impressed by the sincerity of Lever’s report, and the fact that his crew was bold enough to repeat their fantastic story to their incredulous colleagues. Nonetheless, the object they saw resembles no known aircraft flying at that time and this case remains one of the most unusual UFO mysteries from the period.

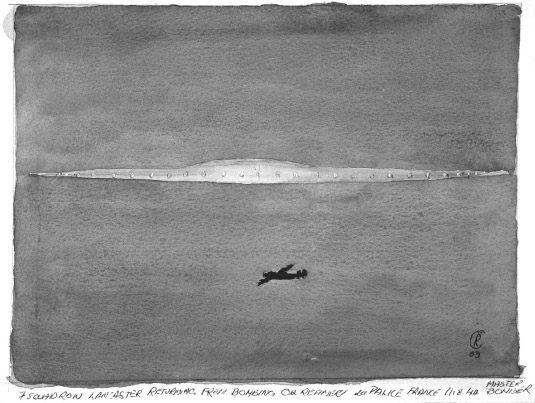

One spectacular account from the penultimate year of the Second World War, however, seems to provide a classic description of a flying saucer from the pre-flying saucer age. In 1944 Ronald Claridge was a radio operator in a Lancaster from 7 Squadron, part of the Pathfinder Force that flew from RAF Oakington in Cambridgeshire. His Lancaster was returning from a night-time raid on oil refineries at Pelice in southern France on 11 August when his close encounter began.

More than 50 years later Claridge recalled how he was hunched over the aircraft’s radar, scanning for enemy night-fighters during the anxious flight home, when the screen suddenly went blank. As he reported the malfunction to his pilot, Squadron Leader (later Air Commodore) Brian Frow, he heard him yell: ‘what the hell was that?’ Claridge moved quickly into the astrodome of the bomber and immediately saw what appeared to be ‘an enormous string of lights’ on the starboard side of the plane. He recalls, ‘the lights were circular, rather like portholes in a ship. The colour was a very bright yellow changing to intense white. My estimate was that they were about a thousand yards from our aeroplane. The ones nearest our Lancaster were the largest and brightest, they stretched fore and aft to what seemed infinity. After about thirty seconds I could see they were part of an enormous disc.’31

The watercolour painting Ronald Claridge produced illustrates just how large this UFO was, dwarfing the Lancaster in the night sky. All eight crew had been alerted by the intercom chatter and could now see the phenomenon and were left strangely transfixed by the experience. Claridge recalled: ‘we had no feelings of fear but feelings of great calm… even our gunners who would normally open fire were helpless.’ He timed the incident for his radar log at three minutes before the object ‘suddenly shot ahead and was gone. We were travelling at 240 miles per hour but there was no turbulence. There was no noise of engines or vapour of any kind’.

The Lancaster crew were left stunned and spoke very little for the rest of the journey home. On return to Oakington they were debriefed by RAF intelligence who appeared more interested in their feelings of well-being than the details of their experience. Claridge recalls being warned not to discuss the incident or make any entry about it in his logbook. Nevertheless, he told me ‘we all had sensed we were being watched by another force outside our knowledge’.

By the time Claridge made his sighting, almost 50 years passed since the airship scares that had so gripped Britain, and in that time aircraft had become a common sight in our skies. Thousands of aircraft were now daily taking part in operations. The dramatic increase in air traffic naturally meant that if UFOs existed they would be seen and reported with corresponding frequency. But as the war came to an end there was still no widely recognised category into which airmen such as Ron Claridge could place their strange experiences, until the age of the flying saucer finally arrived.

A painting by Ronald Claridge depicting the huge disc-shaped UFO he and his crew saw from their Lancaster bomber during a raid on southern France in 1944.