This chapter is for background and general interest, and is more technical than the other chapters. If you wish to skip this chapter and just read the ‘Take-home message’ at the end and then move on to Chapter 4, that is fine.

Like any personality style or temperament, perfectionism results from both our genes and our environment. Studies of twins suggest that between 24 per cent and 49 per cent of perfectionism may be inherited, that is, passed down in the genes from earlier generations of the family. So the genes we inherit from our parents can influence the development of perfectionism; but the figures above suggest that our environment plays a greater role. Even if genes were the main contributor to the development of perfectionism, this would not mean that perfectionism could not be changed. Irrespective of your genetic inheritance, the decisions you make, and the actions that you take, can help you to change the unhelpful influence of perfectionism in your life.

Again, we know that perfectionism, like any other complex human behavior, will result from many different factors that are all interconnected, not from one single cause. There are likely to be numerous genes that have a small or moderate effect on perfectionism that involve several biological pathways in interaction with various environmental variables. In addition, other aspects of temperament are likely to moderate the impact of perfectionism in your life. For example, some people may have a strong desire to attain high standards but may also have very healthy self-esteem, and thus they do not get overly critical of themselves on the occasions when they do not attain some of the standards that they have set themselves.

It is important to understand that there are multiple causes of perfectionism. This means that there are a number of different approaches that can be effective in decreasing the harmful impact of perfectionism in your life, and that there won’t be just one way of tackling your perfectionism. This process of decreasing the harmful influence of perfectionism in your life can be likened to trying out a number of tools – some will not be useful, and can be discarded; others will be helpful and can be added to the toolbox. The type and number of tools that you use will vary depending on the situation you’re trying to tackle.

While we know that both genes and environment are involved in giving rise to perfectionism, we know very little about which specific genes or which specific environments contribute to it. Most research to date has focused on what high levels of unhelpful perfectionism can cause, and not vice versa. We know that there is an association between the levels of perfectionism that people report and their reports of perceived pressure to be perfect from other people in their lives. Basically this tells us that the more of a perfectionist a person is, the more likely they are to perceive that other people expect perfection from them, and the more likely they are to believe that other people in their lives will criticize them for not achieving perfection. What we cannot tell from these associations, however, is whether people with a high level of perfectionism believe that everyone around them has the same standards that they have, or whether being exposed to people with high standards can cause perfectionism in an individual.

Some people with perfectionism have perfectionist parents and/or come from families with excessively high standards; others do not. It may be that, whatever the reason behind the beginning of perfectionism, perfectionist behavior is rewarded by other people and may be rewarding for the person who practices it, thus strengthening such tendencies, as depicted in our example of Suzie below. Being a perfectionist can mean that a person appears to be reliable, in control, thorough and responsible, and it can give that person a sense of control and order and structure. However, as we noted in Chapter 1, over time perfectionist behavior leads to negative consequences, such as fatigue, self-doubt, procrastination, lack of concentration, lower self-esteem, depression and anxiety.

Suzie: An example of how perfectionism developed and was maintained

Suzie’s parents were both teachers and they encouraged Suzie and her elder sister to attain high standards at school. They expected nothing but the best, and were disappointed when Suzie achieved only As rather than A + s for her schoolwork. Suzie also recalls her parents requiring her and her sister to be better behaved in social situations than any other children present. Any small lapses in good behavior in public brought forth emotional reactions (tears, shouting and stony silences) after the family had reached the privacy of their own home. Suzie grew up to fear these scenes and indeed any expressed disapproval, and made it her main goal in life to achieve high standards so that she wouldn’t feel guilty about being a bad person. In secondary school Suzie received a lot of positive feedback from her teachers about her responsible behavior and academic achievements. She enjoyed this attention, as she did not feel that she was very good at making and keeping friends. Suzie is now 32 years old; she lives independently from her family, but has regular contact with them that is enjoyable and supportive. However, over time she has increased the pressure on herself to attain high standards, and feels a failure in her work as a physiotherapist if her clients are not absolutely satisfied with the service that she gives them. In order to prevent any mistakes from happening in her work with her clients, Suzie spends hours writing up the case notes for each client, and often works late in order to achieve this. As she spends more time on the notes, she is becoming increasingly anxious, in case she misses any detail that might lead her to not offer the best service to her clients.

As you can see from what has been written so far in this chapter, we do not really have any very specific idea of all the different things that can cause perfectionism and their relative importance. The bottom line, however, is this: we do know that, no matter what causes perfectionism, unhelpful perfectionism can be reduced, thereby significantly improving the quality of people’s lives. In other words, you do not have to understand how your perfectionism started in order to overcome it.

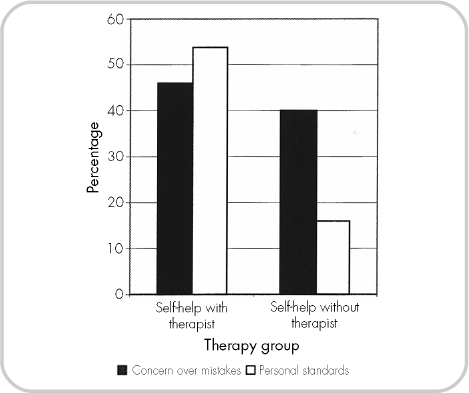

How do we know this? There have been several evaluations of therapeutic approaches designed to decrease unhelpful perfectionism that have shown certain approaches to be effective. The first was an evaluation of a self-help book, When Perfect Isn’t Good Enough.* Two treatment groups were set up. One received the book and worked through it over the course of eight 50-minute weekly meetings with a postgraduate psychology student (not a trained therapist). The second group received the book, instructions and a timetable on how to use the book, and minimal contact with the postgraduate psychology student – just two brief phone calls over the eight-week period. Each group was followed up three months after the eight-week treatment period ended. One indicator of outcome was how many people had experienced clinically significant decreases in perfectionism by the follow-up – ‘clinically significant’ meaning not just a large decrease but one likely to be reported by the person as making life better for them. As you can see from Figure 3.1, around 50 per cent of people in the group that met with the student had clinically significant reductions in both types of perfectionism that were measured: concern over mistakes and personal standards. Fewer people reported clinically significant reductions in the group that received only the book, but 40 per cent of the group did report experiencing clinically significant improvement in concern over mistakes.

In addition to decreases in perfectionism, there were improvements across a number of other areas. For example, for those people who worked through the book with the postgraduate student, clinically significant improvements were experienced in obsessionality by 29 per cent of the group, in depression by 38 per cent of the group, and in feelings of being responsible for things that go wrong by 54 per cent.

So what can we conclude from this study? The first conclusion is that relatively brief periods of treatment with non-specialist therapists can be effective for reducing perfectionism and the other types of problems that accompany it, such as depression. The second is that it is probably best to get some sort of therapeutic support as you work through this book, in order to make the most of the ideas that are contained here. This sort of support should be available via your GP, through self-referral as part of the government’s ‘Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’ service (www.iapt.nhs.uk) or privately (see www.babcp.com for a therapist who is accredited by the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy).

The second evaluation of a perfectionism treatment comes from the work of Roz Shafran and her colleagues at Oxford University. They compared people going through ten sessions of therapy for perfectionism to people who were on the waiting list for therapy, and therefore not currently receiving it. People receiving therapy experienced clinically significantly greater reductions in perfectionism than the people waiting for therapy. Of all the people who then went on to do therapy, 75 per cent experienced clinically significant decreases in perfectionism, and these treatment gains were maintained at follow-up 16 weeks after the end of treatment. As in the previous treatment study, treating perfectionism also had beneficial effects in other areas of the participants’ lives. Of those people who entered treatment, 50 per cent met criteria for an anxiety disorder or major depressive episode immediately prior to treatment; by the 16-week follow-up stage this had fallen to 20 per cent. Similar positive results with treatment resulting in decreases in perfectionism and symptoms have also been found in studies by Roz Shafran and Dominic Glover in the UK, and Sarah Egan and Paula Hine in Australia.

Figure 3.1 Clinically significant decreases in perfectionism after a brief treatment with a non-specialist therapist

This idea that treating unhelpful perfectionism has benefits for other areas of people’s lives was reinforced by the results of a treatment study by Anna Steele and Tracey Wade in Australia. They offered people who had bulimia nervosa eight brief sessions of therapy with a postgraduate psychology student (again, not a trained therapist). Three different treatments were compared: a treatment for perfectionism, a treatment for bulimia nervosa, and a mindfulness treatment. All three groups improved significantly over time with respect to their bulimia nervosa. At six-month follow-up, these improvements had been maintained, and people receiving the perfectionism treatment had also experienced significant decreases in depression and concern over mistakes, as well as a significant increase in self-esteem.

The research on treatment of perfectionism tells us that starting treatment for perfectionism can have something of an avalanche effect in a person’s life. Beginning work on reducing unhelpful perfectionism also starts to have helpful effects on related problems in a person’s life, such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, obsessionality and disordered eating. This occurs even though these other problems are not explicitly targeted. This is because perfectionism can have unhelpful effects in a person’s life, as discussed in Chapter 2, and so winding back the perfectionism reduces these as well.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

* This evaluation was carried out by Jessica Pleva and Tracey Wade in Australia in 2007. For full details of the book evaluated (Anthony and Swinson, 2009), see ‘References and further reading’.