Jean-Pierre Laffargue and Eden S. H. Yu

The Chinese savings puzzle is defined by its increasing national savings rate since the early 1990s and reaching an unusually high level in recent years. There are two main causes for this puzzle. The first one is the high and increasing share of Chinese firms and financial institutions in the national disposable income (these agents have no final consumption and so save their whole disposable income). This can be partly explained by an uneven sharing of value added, which favors profits to the detriment of wages, due to the high and increasing supply of labor in urban areas. The high corporate saving also results from the low distribution of firms’ income. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) generally have little incentive to distribute dividends, and those that are distributed, are usually reinvested; private firms face rationing in the credit market and need to finance a bulk of investments with their own retained earnings.

The second cause of China’s savings puzzle relates to the increasing and high household savings rate. This can be explained by the life-cycle hypothesis while taking into account of a set of pertinent Chinese factors, such as the one-child policy, which induces parents to save more in the absence of sufficient children to support their post-retirement life, and the necessity for households to accumulate enough savings in order to buy a house when the mortgage market is still quite limited. A complementary explanation is the higher precautionary savings accumulated by households to prepare for contingencies, e.g. unemployment and health risks.

In this chapter, we delineate several puzzles in the Chinese saving behaviors. China’s national savings rate, that is the ratio of its savings to its national disposable income, has increased from 36.3 percent in 1992 to 50.6 percent in 2009. For the same year, the savings rate of Korea, Japan and France were respectively equal to 30.2 percent, 21.6 percent and 17.2 percent. China’s exceptional saving behavior is usually called the Chinese savings puzzle.

If we break down China’s savings rate among the contributions of its households, business, and government sectors, we can see that households in China save much more than the counterparts in other countries, although their share in China’s national disposable income is low and has steadily decreased from 1997 to 2008. This results from their high and increasing savings rate – the ratio between their savings and their disposable income – that is called the household saving puzzle. The savings of China’s firms and financial institutions have shown an increasing share of the national disposable income from 1997 to 2008 – a share that was higher than in any other country in 2009. This is usually called the corporate savings puzzle. Finally, the Chinese government saves a share of its disposable income, which was high in the early 1990s and the late 2000s.

Section 1 presents the two savings puzzles. Section 2 investigates the corporate savings puzzle. It is found that the increasing and high savings of firms results from the low and decreasing share in the national disposable income of their distributed properties income (dividends and interest). The puzzle is also related to a low and decreasing share of firms’ value-added going to wages for the firms’ workers while the share of profits (and other returns to capital) is high and rising. This section also proposes several detailed explanations of these empirical results.

Section 3 reviews the explanations for the puzzle concerning household savings. There are basically two kinds of explanations. The first explanation is based on the life-cycle hypothesis by focusing on the dynamics of household savings. Namely, how do households allocate their savings over their lifetime, and how does the national savings rate increase with the relative number and income of people in the high savings period of their life? This approach allows a partial but correct understanding of the puzzle, if some specific and important features of the Chinese economy and society are taken into account. For instance, the opening up of the housing market and/or the reforms of the public pension system in the second half of the 1990s are pertinent.

The second kind of explanation of the household savings puzzle focuses on the level and changes in the following types of uncertainty: the risk of having to pay large medical bills or of losing one’s job, in the face of poor publicly provided insurance and safety nets. This uncertainty induces households to accumulate significant savings for precautionary purpose. Section 4 offers some concluding remarks.

The best statistical source available for analyzing the macroeconomic trends of China is the flow-of-funds tables, which show a matrix of institutional sectors by transaction items. We use them to compute the ratios of the national savings as well as sectoral savings of China to the country’s national disposable income.2 We plot the ratios covering the period of the early 1990s to 2009 in Figure 8.1.

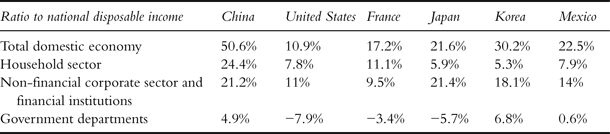

The national accounts of the OECD use a nomenclature similar to that of the flow-of-funds tables of China. We use the data to compute the ratios of the national gross savings as well as sector-based savings to the gross disposable income for the United States, France, Japan, Korea, and Mexico in 2009. The results are presented in Table 8.1.

We observe from the graph in Figure 8.1 that China’s national savings rate fluctuated around 38 percent from 1992 to 2000, and then steadily increased to the value of 50.6 percent in 2009. Table 8.1 shows that these values are unusually high. The second and third highest savings ratios in 2009 occurred in Korea and Japan, respectively equal to 30.2 percent and 21.6 percent.

Many countries have gone through long periods of high levels of savings, investment, and economic growth, accompanied by rapid industrialization. During the developmental process, labor was induced to migrate from rural areas and/or foreign countries to the industrial urban sector. This happened in both continental Western Europe and Japan after the Second World War and South Korea two decades later. The increasing labor supply in the urban areas led to somewhat moderate labor wages and thus high business profits and corporate savings. As banks were compelled by governments to favor producers over consumers in their allocation of credits, households had to save a great deal in order to buy a real estate unit or durable goods.

The high levels of household and business-sector savings provided financing to support a high level of investment sustaining and spurring economic growth – depicted by the standard economic development model. However, what has been happening in China in the recent decades is far more than what this standard model can capture. Kuijs (2006) estimates a savings equation, based partly on the theoretical insight of this development model, on a panel of 134 countries over the period of 1960–2004. He obtains a good fit for most countries, but China is an outlier. The equation predicts a savings ratio of only 32 percent of GDP for China for the final period of the estimation. In contrast, the observed value actually was 44 percent. Kraay (2000) and Hung and Qian (2010) conduct similar estimations using different data sets, and reach the same conclusion.

China’s savings puzzles have also been investigated by using dynamic general equilibrium models. Such general equilibrium frameworks are useful for studying a variety of economic issues while taking into account the interactions among several markets or sectors in an economy. Simple static general equilibrium models have been deployed to examine the various effects during a single period, whereas dynamic general equilibrium models capture the effects over multiple periods. Generally, the latter starts with some objective functions, such as social welfare, which are maximized by agents subject to a set of pertinent constraints over a finite, or infinite span of time.

The optimizing conditions and results are often revealing and shed light on understanding the behavior of economic agents. The main results obtained using the dynamic general equilibrium frameworks are either that Chinese households exhibit a very high preference for the future (Fehr, Jokisch, and Kotlikoff, 2005), or that they face a very high level of uncertainty, inducing them to build up a significant amount of precautionary savings (Yu and Ng 2010), or that China simply saves too much (Lu and McDonald, 2006).

Table 8. 1 Gross saving: comparison between China and five OECD countries (2009)

We plot on Figure 8.1 the ratios of the savings of China’s household sector, its non-financial corporate sector and financial institutions, and its sector of government departments to China’s national disposable income. For the household sector, the savings ratio has been fluctuating a bit above 20 percent and increasing since 2002. However, the saving ratio has been increasing for the business sector since 1997 and for the government sector since 2000. It is noteworthy that the savings rates of the household sector and of the business sector have been about the same since 2001 at about 21 percent of the national disposable income, whereas savings of government sector were much lower (peaked at 5.9 percent of the national disposable income in 2008).

For purpose of comparison, we use the National Accounts of the OECD countries to compute the savings ratios of the same three sectors in 2009 for five OECD countries and the results are presented in Table 8.1. We observe that regarding the savings ratio of households, the outlier is China, which has the highest ratio among the six nations. France comes next with a household savings ratio of only 11.1 percent, against 24.4 percent in China. On the other hand, the savings ratio of 21.2 percent scored by the Chinese business sector in 2009 is not so different from the ratio of 21.4 percent in Japan and 18.1 percent in Korea. However, it is notable that the Chinese government sector has a relatively high savings ratio of 4.9 percent, higher than the other countries in the sample, except Korea (with 6.8 percent).

The ratio of the savings of each of the three sectors (household, business, and government) to national disposable income is the product of its savings rate – the ratio of its savings to its disposable income – by the share of its income in national income. Thus, the savings ratio of a sector can increase either because of a rise in its savings rate or because its disposable income increases faster than national income.

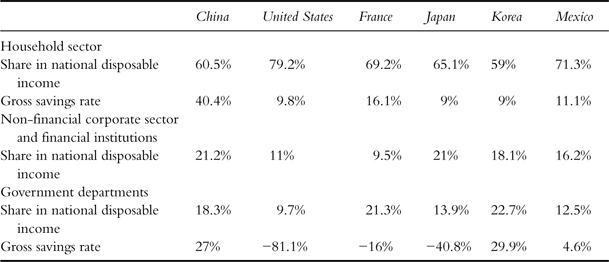

Figure 8.2 shows that the savings rate of the household sector increased sharply since 1999 while the rate of the government departments dropped significantly from 1997 to 2000 and bounced back dramatically since then. Both types of savings rates reached very high values (respectively 40.4 percent and 27 percent) in 2009. As there is no final consumption by the business sector, its savings rate is always equal to 100 percent.

Turning to Figure 8.3, in which we plot the shares in the national disposable income of the three sectors, a notable feature is the sharp increase in the share of the business sector beginning 1997, while the share of government departments has been on the rise since 2000. On the other hand, the share of the household sector has steadily decreased since 1997. The respective shares of the household sector, the business sector, and government sector in 2009 were 60.5 percent, 21.2 percent and 18.3 percent respectively.

Table 8.2 presents the shares in the national disposable income and gross savings rates of the three sectors in China as compared to the same selected five OECD nations. The data are derived from the National Accounts of the OECD countries. We observe from Table 8.2 that the household savings rate in China is extremely high in comparison to other nations. The savings rate of the government sector is also high, but about the same as in Korea. The share of the household sector in the national disposable income is low (and about the same as in Korea), whereas the share of the business sector is high (but only slightly higher than that in Japan). Furthermore, the share of the Chinese government sector is also high (but less than the counterparts in Korea and France).

In short, the high and increasing Chinese national savings rate since 2000 mainly results from the following two savings puzzles (see He and Cao, 2007, for similar conclusions):

• The increasingly high share of the business sector savings – which is the same as its disposable income – in the national disposable income since 1997. This is the corporate savings puzzle.

• The high and increasing household sector savings rate since 1999, referred to as the household savings puzzle.

Moreover, we note that the savings rate of the Chinese government departments has sharply increased since 2000 and its value peaked at the end of the decade. Several studies on the economic conditions in China attempted to explain this observation (see for instance the publications of OECD, 2010 and 2012). The flow-of-funds tables reveal that the government savings have been utilized in the 2000s to finance either capital transfers or capital formation, especially in building up infrastructure and financial investment. It was concluded by the OECD studies that the policies of the Chinese government have differed from those of most other countries in the recent decade of 2000s in that China stresses on social capital accumulation rather than public consumption.

Table 8.2 Shares in national disposable income and gross saving rates of the three sectors: comparison between China and five OECD countries (2009)

We will examine further in the following sections the corporate savings puzzle and the household savings puzzle.

We have just observed that the share of the business sector in national disposable income has been on the rise since 1997 and it reached the high rate of 21.2 percent in 2009. We use the flow-of-funds tables to decompose the trend into three parts: the contributions of the current transfers paid by the business sector; second, of the income from properties distributed by the sector; and third, of the sharing of its value added. We will also provide some explanations for the changes in the levels of each of the three contributions.

We state the following accounting identity:

Disposable income = income from primary distribution + current transfers

Here, current transfers include income taxes, payments to social securities, social allowances, and other current transfers.

Figure 8.4 depicts the share in national disposable income of the net current transfers paid by the business sector. The share values decreased from 1992 to 2000, and then climbed up again. The share in national disposable income of the business sector income from primary distribution is almost parallel to the share of business disposable income. Hence, current transfers do not explain much of the corporate savings puzzle.

We state the following accounting identity:

Income from primary distribution = gross operating surplus + income from properties

Income from properties includes interest payments, dividends and land rent. We divide the two sides of this identity by the national disposable income and plot its components in Figure 8.5. We note that the income of properties distributed by the business sector is low and that its share in the national disposable income has been decreasing from 1996 to 2005 before increasing again by a small amount.

Some explanations for the above observations are proposed by Ferri and Liu (2010) and Yang, Zhang and Zhou (2011) in terms of policy reforms, which had been implemented since the early 1990s. It is pointed out that the government delayed requiring SOEs to pay dividends until 2008,3 even though they had enjoyed handsome profits since the state-sector restructuring in the late 1990s. Furthermore, SOEs generally paid low interest, whereas private firms had encountered difficulty in borrowing from banks. As a result, private firms need to resort to informal and private financing channels or relying on their own funds – i.e. their retained earnings or savings – to finance investment. Bayoumi, Tong, and Wei (2010) examine the micro data of a large sample of listed firms over the period of 2002 to 2007. In contrast to the previous studies, they find that Chinese corporate savings rates and dividends distribution are not that different from other economies. Further, there is within China no significant difference between the majority SOEs and majority privately owned firms so far as savings rates and dividends distribution are concerned.

Finally, we state the following accounting identity:

Value-added = gross operating surplus + remuneration of employees + net taxes on production

Dividing the two sides of this identity by the national disposable income, we plot its components in Figure 8.6. We observe from the graph that the share of the gross operating surplus of this sector has increased since 1998, while the share of the remuneration of employees has decreased since 1997. It is somewhat surprising that these two components are of the same order of magnitude, in contrast to most countries where the remuneration of employees is twice as large as the operating surplus. Furthermore, the ratio of net taxes on production to the national disposable income has slightly increased since 2000.

Aziz and Cui (2007) develop a model to explain the low and decreasing share of labor income in China’s national disposable income, based on the observation that it is easier for Chinese firms to finance fixed than it is for them to finance working capital. This imperfection of the capital market has the effect of suppressing the demand for labor, hence lowering wages and urban employment. More generally, the low share of labor income is probably related to abundant young workers and a large surplus of rural labor (Ma and Yi, 2010).

Recently, questions have been raised as to how long this situation will last (for instance Miles, 2011, OECD, 2010 and 2012, Yang, Zhang, and Zhou, 2010). It is notable that there are strong indications of an increase in labor wages, which could lead to a redistribution of income from profit seekers to wage earners. Moreover, this could lead to an increase in consumption and a decrease in savings. There are also reports of increasing labor unrest in China and sentiments favoring the protection of the rights of workers. By July 2010, eighteen provinces had announced increases in minimum wages by an average of 20 percent. In 2011 labor incomes rose strongly, especially for rural migrant workers. Furthermore, one may also wonder whether China has reached the point at which industrial wages will start to rise rapidly as a consequence of the disappearance of the rural labor surplus. Is China’s large supply of labor beginning to vanish as a consequence of the one-child policy?

There is still a large surplus of labor in rural areas at this point, and policies are being introduced or are being discussed by Chinese officials and scholars to help release rural labor to support urban manufacturing, as follows: liberalizing the household registration – hukou – system, reforming rural land ownership, or development of mechanization and consolidation of land plots.4 The demographic consequences of the one-child policy will not be fully manifested perhaps until 2020 or even later, if the retirement age (presently very low in China) were to be raised. Thus, there are good reasons for us to expect that it will take years for income distribution to evolve and become more favorable to labor.

The ratio of household savings to the national disposable income has fluctuated around 20 percent since 1992 for about a decade and then steadily increased from 2002 to 2008. This upward movement results from the combination of a decreasing share of household income in the national disposable income, by 10 percentage points from 1992 to 2008, and concomitantly an increasing and high savings rate.

The reasons for the decreasing share of households in the national disposable income are symmetric to the causes underlying the increasing share of the business sector. The shares of both the net current transfers and the income from properties received by the household sector have steadily decreased. This is a consequence of the rise in the social welfare contributions of the sector and of the fall in bank deposit interest rates (see Yang, Zhang, and You, 2010). The ratio of the net remuneration of employees to the national disposable income has also decreased.

We begin our investigation of the household savings puzzle, in subsection 3.1, by presenting another data source in which urban households are separated from rural households. The data allows us to compute the Chinese household savings rates over a longer span of time. We also use the computed rates to trace the path and compare it to the paths in Japan and Korea obtained for the periods of fast growth of these two countries, i.e. after the Second World War and the Korean War, respectively.

There are two complementary strands of the literature in explaining the puzzle. The first set of explanations, presented in subsection 3.2, focuses on the dynamics of household behavior by attempting to answer the following: how do households allocate their savings over their lifetime and how does the national savings rate rise when the relative number and income of the people in the high saving period of their life increases? The second set of explanations rests on the level and changes in uncertainty (for instance the probability of becoming unemployed, or having to face expensive medical bills). This will be presented in subsection 3.3.5

Using the surveys on urban households and rural households, provided by the Office of Household Survey of the National Bureau of Statistics,6 we compute another set of the savings rates of urban and rural households for each year from 1993 to 2011, and for a few years before 1993. These savings rates are shown in Figure 8.7.

We recall that according to the flow-of-funds tables, the household savings rate fluctuated around 30 percent from 1992 to 1999, and sharply increased from 1999 to 2009 reaching the high rate of 40.4 percent. The household surveys, however, show lower savings rates. Specifically, the urban household savings rate steadily increased from 8.9 percent in 1985 to 30.5 percent in 2011, whereas the rural household savings rate fluctuated quite a bit, but along an upward trend. The observed divergence of the rates estimated using the surveys versus the flow-of-funds tables can be explained by the fact that the surveys tend to underestimate income, while they provide a more accurate estimate of consumption figures. Thus, the surveys underestimate savings and the savings rate.

Eastern Asia provides a series of cases of countries that were severely war-torn or very poor in the 1950s, but recovered and bounced back three decades later; some even reached a record-high income level and caught up with the world’s most advanced industrialized nations. We observe in Figures 8.8 and 8.9 that two such Asian countries achieved high levels and growth of household savings during the process of rapid development. The household savings rate in Japan and Korea7 started at low values, and then steadily increased. After reaching the high values of 21.8 percent and 25.9 percent for Japan and Korea, respectively, the savings rates steadily decreased. The rates decrease became significant in Japan after 1978 and also in Korea but 20 years later.

According to the Penn World Table, 7.1 (see Heston, Summers, and Aten, 2012) the per capita GDP of Japan in 1978 and Korea in 1998, converted by purchasing power parity (PPP) at 2005 constant prices, was US$17,600 and US$15,500 respectively. In comparison, the per capita GDP of China was US$7,400 in 2010 (an average of the two measures given by PWT 7.1), when its urban and rural savings rates stood respectively at 29.5 percent and 26 percent. It is notable that this per capita GDP level was achieved by Japan in 1962, when its household savings rate was equal only to 13.9 percent and by Korea in 1985 with a savings rate of 15.4 percent.

Figures 8.8 and 8.9 seem to suggest the existence of a savings cycle as follows: the household savings rate would initially increase, when per capita GDP rises, and then the rate decreases, when per capita GDP passes over a threshold amount of about US$16,000–US$18,000 (at 2005 US$). Assuming that this cycle exists, China at its current stage of development would support a much higher rate of household savings than expected, and this higher savings rate would continue to increase for many years to come. In any event, we argue that the savings behavior of Chinese households is exceptional.

The life-cycle hypothesis is related to explaining consumer behavior in a model developed in the 1950s by Franco Modigliani and his collaborators, Albert Ando and Richard Brumberg. The basic idea of the hypothesis is that income varies over a person’s life span and saving allows moving income from the times in one’s life when income is high to those times when it is low. More specifically, to smooth out consumption over one’s life time, a typical person saves little in early adult life when income is still low. This person saves a great deal in the middle and toward the end of his or her work life. After retirement, when income is low again because pensions are in general lower than wages, the person dis-saves to maintain his or her living standard.

The total savings of an economy in a given year is the difference between the savings of the active households and the dis-savings of the retired people. If the economy grows fast, the savings of active households generally draw from a higher income pool than the income of retired people, saved earlier during their active years. This inter-temporal gap in earned income increases the savings rate computed based on the whole set of households. Similarly, the household savings rate rises if the proportion of “big savers,” that is, people in their forties or fifties, in the population increases.

Modigliani and Cao (2004) offer an explanation of China’s high household savings rate based on the life-cycle hypothesis (see also Horioka and Wan, 2007). They come up with a more complete story by noting that the one-child policy has lowered the cost of rearing children for the young active adults, resulting in an increased net income available for saving. They add that this policy also has the effect of reducing financial support for retired parents from their children; a working couple after marriage may need to support four parents, and this is quite a heavy burden on their grown-up children. To alleviate this burden, there is a strong inducement for some active households to save more especially in a country where the public pension system is still weak.

Modigliani and Cao run a series of econometric regressions to explain the aggregate household savings rate in China over the 1953–2000 period. They find that the long-term growth rate, computed as an average on the past 14 years, and the inverse of the young dependency ratio, defined as the number of persons employed divided by the number of persons 14 years or younger, are the two most important explanatory variables; both show strong positive effects on the savings rate.

The econometric results of Modigliani and Cao are supportive of the life-cycle hypothesis. However, other studies on testing the hypothesis have yielded different findings. For instance, Chamon and Prasad (2010) investigate the saving behavior of Chinese households by using household data from 16 consecutive Urban Household Surveys from 1990 to 2005. This pseudo panel data allows the use of a method developed by Deaton and Paxson (1993) so as to separate the effects of changes in the income and the savings of a household based on age, or life cycle, from the effect of increasing wages over time, a result from the development of the Chinese economy. The authors obtain an unusual age profile of savings covering the period of mid-1990s through the 2000s, in which the younger and older households exhibit relatively high savings rates. This is contrary to the “hump shaped” profile of savings assumed by the life cycle hypothesis. The age cohorts most affected by the one-child policy are not among the highest savers. Moreover, the overall savings rates have increased across all demographic groups.

Chamon and Prasad argue that their results can be better explained by the rising burden of private spending on housing and education for the young cohort and on health care for the elderly. It is notable that only 17 percent of urban households owned their home in 1990; however, a new policy of massive sale of public housing to their tenants occurred around 1998 and this continued afterward. The new owners purchased their housing at good bargain prices that were well below the market rates. Since then, the private housing market became active in China. By 2005, 86 percent of urban households owned their home. In that year, only 5 percent of households used mortgage financing and repaid a home loan, implying that access of Chinese households in the credit markets was much constrained. Young adults need to save a lot to buy a housing unit before they get married, and this alone, according to the authors, could explain a 3 percentage points increase in the urban savings rate from the early 1990s to 2005.

Wei and Zhang (2011) observe that parents in China typically pay for the housing for adult sons to facilitate their marriage. To help their sons to get married in a country where the girl–boy ratio has been decreasing quickly and where the competition for finding a spouse has become tougher, parents want to be able to provide their sons with a better home. This leads to a greater demand for housing and hence higher housing prices, which in turn induces even the households without a son to save more in order to afford decent housing. This chain, spiral effect on housing demand and prices, coupled with the increasing disequilibrium of the marriage market between men and women provide a good explanation for the rise of household savings in China, about half of the actual increase in the household savings rate during 1990–2007.8

A lack of availability of credit leads to a higher household savings rate. In China, credit to households has been strictly rationed in the past. A recent study of the Chinese economy (OECD, 2010) notes that China’s consumer credit market is still relatively small compared to the credit market for enterprises. But the former is developing quickly; banks have rapidly expanded mortgage lending with an increase of over 20 percent annually since 2006, though mortgage lending represented only 10 percent of total bank lending in mid-2009. However, farmers are still not allowed to use their land as collateral to borrow. Furthermore, the assets which can be used by small and medium private firms as collateral are still limited, thereby inducing higher savings of the self-employed and small businesses, shown in the Household Surveys of the National Bureau of Statistics.

Modigliani and Cao’s analysis is based on the econometric estimation of a reduced form equation consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis. Chao, Laffargue and Yu (2011) opt to estimate a structural model, which includes all the ingredients of the life-cycle hypothesis, and to check if this model can reproduce the rise of the urban Chinese household savings rate for the period of 1975 to 2005 (see also Chamon and Prasad, 2008, and Curtis, Lugauer, and Mark, 2011). They find that wage growth and demographic changes can explain no more than one third of the surge in the household savings rate. However, when housing investment is incorporated into the model, similar to the results of Chamon and Prasad, and Wei and Zhang, the model can reproduce the increase in the household savings rate, from the mid-1990s to 2005.

Several micro-econometric studies have attempted to explain why after 1995 there was a large increase in the savings rates among the youngest households living in urban areas. Feng, He, and Sato (2011) base their explanation on the public pension reforms of 1995–97. The reforms significantly reduced the amount of pensions for public workers, when they retire. However, the eldest workers were wholly or partly exempted from this effect. According to the life-cycle hypothesis, the younger workers should react to these reforms by saving more in order to compensate for their lowered pensions and accumulating more wealth for their retirement. Meanwhile, the eldest workers with pensions minimally affected by the reforms should also raise their savings, but by a smaller amount. The empirical results of Feng, He, and Sato are consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis. Their estimations show that due to the pension reforms, the household savings rate increased by 2–3 percentage points for the cohort aged 50–59 and by 6–9 percentage points for the cohort aged 25–29 in 1999.

Song and Yang (2010) find that much of annual wage growth is realized as upward shifts in the level of life-cycle earnings profiles for successive cohorts of young workers. On the other hand, earnings profiles have actually become flattened cohort by cohort. These results are confirmed by estimating the Mincer’s equations9 for each of the successive years of their sample, suggesting a drop in the rate of return to workers’ experience, but an increase in the return to education. The flattening of the earnings profile together with the assumption of an interest rate larger than the household discount rate, lead to a positive and increasing savings rate of young households.

Other micro-econometric studies focus on specific aspects of the household savings behavior. For example, Banerjee, Meng, and Qian (2010) verify the conjecture that parents save more when they have fewer children. Cai, Giles, and Meng (2006) find that children transfer money to support their retired and poor parents. These transfers rise along with the decrease in the income of the parents, but are insufficient to fully compensate for the loss in parents’ income. The amount of transfer to parents also increases with the number and educational attainment of their children. Ding and Zhang (2011) conclude that the arrival of a son in a rural family induces the family to increase its investment, in order to raise their son’s life-long earning so as to enhance his ability to take care of his aging parents in the future.

There is a very different set of explanations for the Chinese household savings puzzle, which rests on the effects of increasing uncertainty. Uncertainty, which characterizes all the economies in transition, especially China, has induced households to build up high precautionary savings (Blanchard and Giavazzi, 2006). To test the validity of this explanation, it is essential to develop good indicators of risk. Wei and Zhang (2011) perform a panel regression using data from 31 provinces in China for the period of 1980 to 2007. In the analysis, the proportion of the local labor force that works for state-owned firms or government agencies is used as a proxy for the degree of job security. The share of local labor force enrolled in social security is included as a proxy for the extent of the local social safety net. Coefficients for both variables are negative and statistically significant, lending support to the precautionary savings motive.

China has implemented a household registration system, known as hukou, which acts as a kind of domestic passport for Chinese and limits the access of rural migrants to public services in the cities where they work and live. Moreover, the migrants are discriminated against within the urban labor market. How would hukou affect the saving rates? Chen, Lu, and Zhong (2012) run a series of regressions on a sample of urban and migrant households and find that migrants without an urban hukou spend 31 percent less than otherwise similar urban residents. These differential consumption gaps suggest that rural migrants save more for precautionary purposes due to higher income risks and the lack of social security coverage. Further, the authors estimate that removal of the hukou system would lead to a rise of 4.2 percent in aggregate household consumption and 1.8 percent in GDP.

Empirical analyses of various types of risks also point to the strong precautionary motive for savings by Chinese households (for example, see Chamon and Prasad, 2010, on health risk; Meng, 2003, on unemployment risk; Chamon, Liu, and Prasad, 2010, on income risk; Giles and Yoo, 2007, on agricultural activities risk measured by rainfall variability – see also Jalan and Ravaillon, 2001).

The national savings of China has been increasing at faster rates than its national disposable income, especially since the early 1990s, and the savings rate has reached an extremely high level in recent years. We have shown that this puzzle of China’s remarkable savings growth can be attributable to two main causes: An increasing and high share of firms’ and financial institutions’ disposable income in the national disposable income and a rising and high household savings rate.

The corporate savings puzzle can be explained by the low and decreasing share in the national disposable income of firms’ distributed properties income (dividends and interest), and a distribution of value-added, increasingly in favor of the firm owners possibly at the expense of workers. The household savings puzzle can be partly resolved by the life-cycle hypothesis. People generally save a great deal in the second half of their working life, when their income is the highest, and they dis-save to support their living standard after retirement. In the event that wages increase at high rate as a result of rapid economic growth, or there is a high proportion of middle-age workers in the population, the income of middle-age workers is higher than the income retired people earned when they were themselves active. Thus, savings by the former workers are higher than dis-saving by retired people and high national savings rate ensues. However, the life-cycle hypothesis needs to be extended in several directions to better explain the savings puzzle for China. Household savings have been encouraged by a mix of social and financial developments in China: reductions in pension benefits due to economic reform, decreased support for retired parents by their children because of the one-child policy, and limited access of households to credit forcing them to save more to buy a home. The level and changes in uncertainty can also play a role in the saving behavior of households. The risks of incurring large medical costs, or of losing one’s job in the presence of insufficient coverage of public insurance, induce households to accumulate savings for precautionary purpose.

1 We owe special thanks to Gregory Chow and Dwight Perkins for their very useful criticisms and advice. We are indebted to Mi Lin for excellent research assistance. This research was done when Jean-Pierre Laffargue was visiting City University of Hong Kong in July and August 2012. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Research Center for International Economics of City University of Hong Kong.

2 The China Statistical database, available on the website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (www.stats.gov.cn/english), includes the most recent version of the flow-of-funds accounts from 1992 to 2009 (the latter year being the most recent one available in January 2013 when we finished writing this chapter). The definitions of the indicators used in this chapter can be found on the website: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2012/indexeh.htm, in ‘National accounts’, at ‘Brief introduction’ and, ‘Explanatory notes on main statistical indicators’. The national disposable income is equal to GDP plus the net factor income from abroad and the net current transfers from the rest of the world. We can deduce from the flow-of-funds tables that the national disposable income was less than GDP until 2002, and has increased faster than GDP since 1995. This evolution resulted from favorable trends in the net current transfers (for instance higher tourism receipts) and the net factor incomes of China from abroad (for instance the higher interest income of the large official reserves).

3 Cox (2012) notes that since the 2007 reform, SOEs’ dividends have increased to the modest value of 5–15 percent of profits, depending on the industry. However, these dividends are not handed over to the finance ministry to spend as it sees fit but paid into a special budget reserved for financing state enterprises. SOEs dividends, in other words, are divided among SOEs.

4 The current system of collective property of land, with its periodical reallocation to farmers who can work it, induces many young men to stay in rural areas to prevent their families from losing their land rights. However, much of the surplus labor in the countryside is over the age of 40 and people of this age seldom migrate to urban areas. It is noteworthy that migration from agriculture was important and had a significant positive effect on the growth of Germany, Italy, and Spain over the 1950–90 period, even though the share of employment in agriculture in these three countries in 1950 was less than in China nowadays (see van Ark, 1996).

5 There exist a few other explanations for the household savings puzzle. For instance, Lin (2012) and Li (2013) assume that the marginal propensity to consume decreases with income. Then, if we consider two households earning each the household average income, and if we transfer 1,000 yuans from the first to the second household, income inequality increases and total household consumption decreases. Then, the two authors conclude that the rising income disparity that we observe in China has contributed to the rise in the household savings rate. Nabar (2011) develops a model where a household targets a level of wealth, for instance the down payment necessary to obtain a mortgage and buy a home. When the real interest rate decreases, a fortiori if it becomes negative, the building of this wealth requires a higher level of savings. Nabar concludes that, over the period 1996–2009, the decrease in the real interest rate in China can explain a part of the rise in the urban household savings rate (see also Wang and Wen, 2012). Mankiw (2012) has an excellent chapter surveying the different theories of consumption and savings, including those used here.

6 These data are available in the National accounts of 2012 and before, under the denomination People’s living conditions. Table 10.2 gives the per capita annual disposable income of urban households and the per capita annual net income of rural households. Table 10.5 gives the per capita annual consumption expenditure of urban households. Table 10.18 gives the per capita expenses on household consumption of rural households.

7 Each graph plots the household and non-profit institutions serving households net savings ratio and was built out of the OECD Economic Outlook No. 91.

8 The sex ratio at birth in China was close to being normal in 1980 with 106 boys per 100 girls, but climbed steadily since the mid-1980s to over 120 boys for each 100 girls in 2005 and is estimated to be 123 boys per 100 girls in 2008 and 119 boys per 100 girls in 2011.

9 The Mincer’s equation explains the wage rate by several factors, the most important of which are the number of years of education and the number of years of work. Thus, this equation, which is estimated on a sample of workers, gives an estimate of the returns on education and on experience.

Aziz, J. and Cui, L. (2007) ‘Explaining China’s low consumption: The neglected role of household income’, IMF Working Paper WP/07/181, December.

Banerjee, A., Meng, X., and Qian, N. (2010) ‘The life cycle model and household saving: Micro evidence from urban China’, <http://afd.pku.edu.cn/files/09.pdf>.

Bayoumi, T., Tong, H., and Wei, S.J. (2010) ‘The Chinese corporate saving puzzle: A firm-level cross-country perspective’, NBER Working Paper 16432.

Blanchard, O.J. and Giavazzi, F. (2006) ‘Rebalancing growth in China: A three-handed approach’, China and World Economy, 14(4): 1–20.

Cai, F., Giles, J., and Meng, X. (2006) ‘How well do children insure parents against low retirement income? An analysis using survey data from urban China’, Journal of Public Economics, 90: 2229–55.

Chamon, M. and Prasad, E. (2008) ‘Why are saving rates of urban households in China rising?’, IMF Working Paper WP/08/145.

Chamon, M. and Prasad, E. (2010) ‘Why are saving rates of urban households in China rising?’, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(1): 93–130.

Chamon, M., Liu, K., and Prasad, E. (2010) ‘Income uncertainty and household savings in China’, NBER Working Paper 16565.

Chao, C.C., Laffargue, J.P., and Yu, E. (2011) ‘The Chinese saving puzzle and the life-cycle hypothesis: A revaluation’, China Economic Review, 22: 108–20.

Chen, B., Lu, M., and Zhong, N. (2012) ‘Hukou and consumption heterogeneity: Migrants’ expenditure is depressed by institutional constraints in urban China’, Global COE Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series 221, Hitotsubashi University.

Cox, S. (2012) ‘Peddling prosperity. Special report. China’s economy’, The Economist, May 26.

Curtis, C.C., Lugauer, S., and Mark, N.C. (2011) ‘Demographic patterns and household saving in China’, NBER Working Paper 16828.

Deaton, A.S. and Paxson, C.H. (1993) ‘Saving, growth, and aging in Taiwan’, NBER Working Paper 4330.

Ding, W. and Zhang, Y. (2011) ‘When a son is born: The impact of fertility patterns in family finance in rural China’, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, <http://post.queensu.ca/~dingw/sons_and_loans.pdf>.

Fehr, H., Jokisch, S., and Kotlikoff, L.J. (2005) ‘Will China eat our lunch or take us out to dinner? Simulating the transition paths for the US, EU, Japan and China’, NBER Working Paper 11688.

Feng, J., He, L., and Sato, H. (2011) ‘Public pension and household saving: Evidence from urban China’, Journal of Comparative Economics, 39: 470–85.

Ferri, G. and Liu, L.G. (2010) ‘Honor thy creditors before thy shareholders: Are the profits of Chinese state-owned enterprises real?’, Asian Economic Papers, 9(3): 50–71.

Giles, J. and Yoo, K. (2007) ‘Precautionary behavior, migrant networks, and household consumption decisions: an empirical analysis using household panel data from rural China’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3): 534–51.

He, X. and Cao, Y. (2007) ‘Understanding high saving rate in China’, China & World Economy, 15(1): 1–13.

Heston, A., Summers, R., and Aten, B. (2012) ‘Penn World Table Version 7.1’, Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania, November <http://pwt.econ.upenn.edu/php_site/pwt_index.php>.

Horioka, C.Y. and Wan, J. (2007) ‘The determinants of household saving in China: A dynamic panel analysis of provincial data’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39(8): 2077–96.

Hung, J. and Qian, R. (2010) ‘Why is China’s saving rate so high? A comparative study of cross-country panel data’, paper presented at Cesifo Venice Summer institute, The Evolving Role of China in the Global Economy, 23–24 July.

Jalan, J. and Ravaillon, M. (2001) ‘Behavioral responses to risk in rural China’, Journal of Development Economics, 66(1): 23–49.

Kraay, A. (2000) ‘Household saving in China’, World Bank Economic Review, 14(3): 545–70.

Kuijs, L. (2006) ‘How will China’s saving-investment balance evolve?’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3958.

Li, G. (2013) ‘Charting China’s family value’, Wall Street Journal, <http://blogs.wsj.com/chinareal-time/2012/12/10/perception-vs-reality-charting-chinas-family-value/> January 8.

Lin, J.Y. (2012) Demystifying the Chinese Economy, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lu, L. and McDonald, I. (2006) ‘Does China save too much?’, Singapore Economic Review, 51(3): 283–301.

Ma, G. and Yi, W. (2010) ‘China’s high saving rate: Myth and reality’, BIS Working Papers 312.

Mankiw, N.G. (2012) Macroeconomics, New York: Worth Publishers.

Meng, X. (2003) ‘Unemployment, consumption smoothing, and precautionary saving in urban China’, Journal of Comparative Economics, 31: 465–85.

Miles, J. (2011) ‘Rising power, anxious state. Special report. China’, The Economist, June 25.

Modigliani, F. and Cao, S.L. (2004) ‘The Chinese saving puzzle and the life-cycle hypothesis’, Journal of Economic Literature, 42(1): 145–70.

Nabar, M. (2011) ‘Targets, interest rates, and household saving in urban China’, IMF Working Paper WP/11/223, September.

Naughton, B. (2007) The Chinese Economy. Transition and Growth, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

OECD (2010) OECD Economic Surveys: China 2010, Paris: OECD.

OECD (2012) China in Focus: Lessons and Challenges, Paris: OECD, <http://www.oecd.org/China/50011051.pdf>.

Song, Z.M. and Yang, D. T. (2010) ‘Life-cycle earnings and saving in a fast-growing economy’, Working Paper, University of Hong Kong.

van Ark, B. (1996) ‘Sectoral growth accounting and structural change in post-war Europe’, in B. van Ark and N. Crafts (eds.), Quantitative Aspects of Post-war European Economic Growth, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wang, X. and Wen, Y. (2012) ‘Housing prices and the high saving rate puzzle’, China Economic Review, 23: 265–83.

Wei, S.J. and Zhang, X. (2011) ‘The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratio and saving rate in China’, Journal of Political Economy, 119(3): 511–64.

Yang, D. T., Zhang, J., and Zhou, S. (2011) ‘Why are saving rates so high in China?’, IZA Working Paper 5465.

Yu, E.S. H. and Ng, S. (2010) ‘Balance or imbalance of China’s economy versus the world’, in D. Greenaway C. Milner and S. Yao (eds.) China and the World Economy, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.