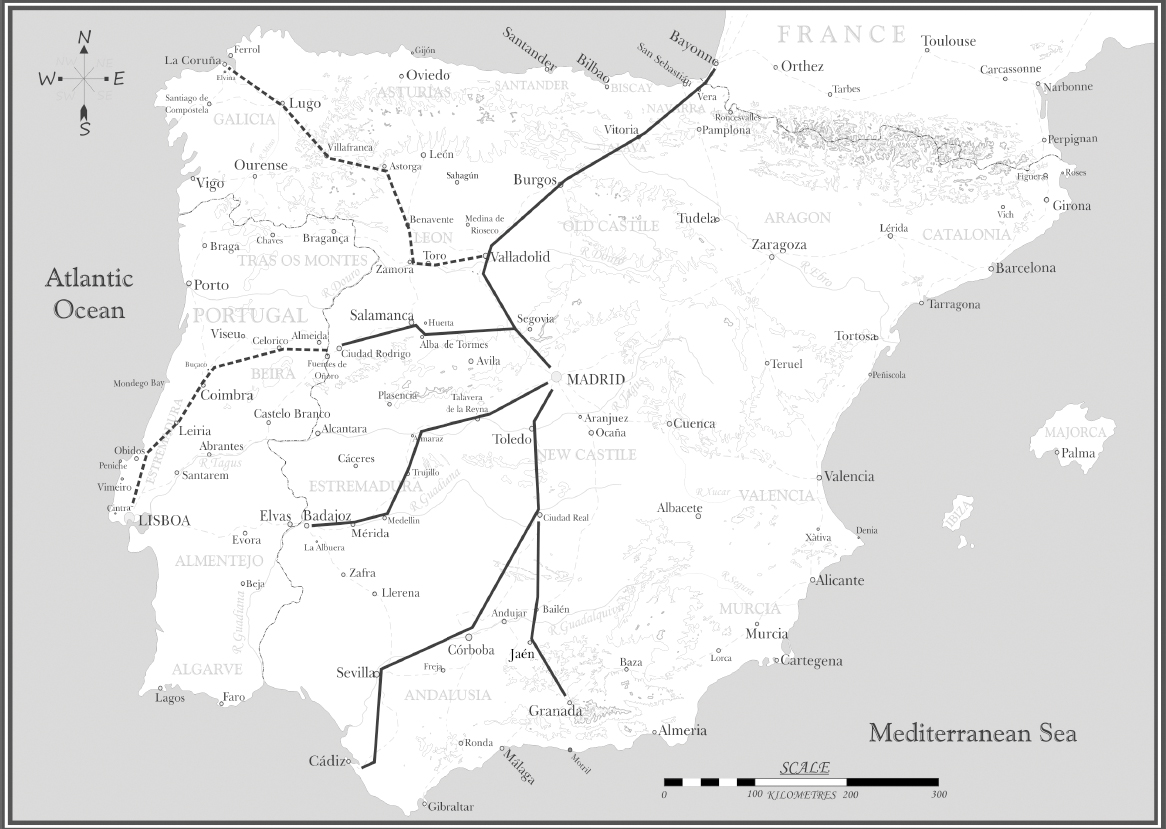

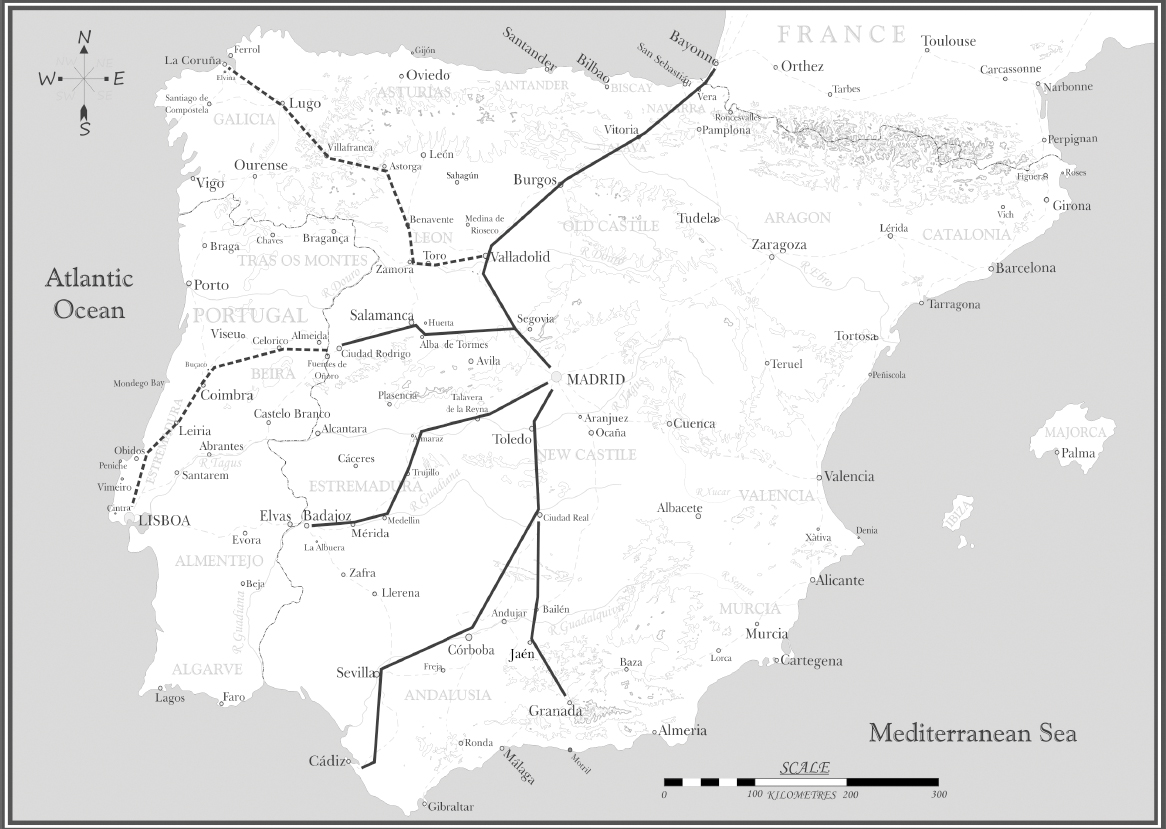

The Iberian Peninsula – French Axes of Advance 1810

By July 1807 Napoleon was master of Continental Europe and in an incontestably commanding position. The Austrians had been defeated at Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805 and effectively neutralised; the Prussians had been defeated at Jena and Auerstadt in 1806 and dispersed; and the Russians, after a bloody draw at Eylau, were defeated at Friedland in 1807 and humbled. The Fourth Coalition lay in tatters and Napoleon was at the acme of his providence and yet, despite his triumphs, his obsession with the great invasion, and consequent subjugation, of Britain still evaded him. His plans had suffered an irreparable setback as a consequence of the naval battle off Cape Trafalgar in October 1805. The range and reach of Britain’s amphibious power and her emergent commerce infuriated Napoleon and thwarted his plans both in Europe and beyond. The elimination of the Danish Fleet in 1807 rendered any aspiration to engage the British at sea untenable and left an attack on her trade the best alternative to petition for peace. Napoleon’s Continental System would lead to a boycott of British trade and, he hoped, bring the nation to its knees, and the negotiating table, through economic means. Conceivably it might also bring about revolutionary change through the bellies of the poor.

Napoleonic diktats, known as the Berlin Decrees, had already been issued in 1806 and the French wasted little time in reinforcing their intentions upon the compliant crowned heads of Europe. By 1808 all of Europe, except Sweden and Portugal, was in a state of enforced hostility towards Britain and while the latter made an attempt to counter the blockade, the fact remained that Britain’s trade fell off at an alarming rate. Corrupt French officials were, however, able to issue trading licences and this loophole was capitalised upon by, in particular, the Iberian nations. It was not long, therefore, following the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807, that Napoleon’s gaze fell upon his southern neighbours. Spanish duplicity had begun to manifest itself as early as 1806 when the Spanish First Minister, Manuel Godoy, had issued an ill-judged proclamation clearly aimed against France. Nevertheless, Napoleon continued to maintain friendly relations with Spain ostensibly because he needed Spanish compliance in order to instigate the first part of his plan – the invasion and subjugation of Portugal.

This was not the first time that France had allied with Spain to invade Portugal. As recently as 1801 during the so called War of the Oranges, Spanish forces, supported by the French military under General Charles Leclerc, had attacked their neighbour in an attempt to coerce the Portuguese into breaking their alliance with Britain. It was an act of aggression instigated wholly by the government of France and, ipso facto, Napoleon as First Consul. Carlos IV, the Bourbon king of Spain, felt compelled to support the French despite the fact that his eldest daughter, Carlota Joaquina, was Queen Consort of Portugal. It was a short-lived campaign, over in two months and concluded at the Treaty of Badajoz on 6 June 1801. The Spanish king intervened by hurrying the peace negotiations in a thinly disguised stratagem to protect the realm for her the husband of his daughter, the regent and future king João. Napoleon was furious at this manipulation, more especially because the treaty had been signed by his own brother, Lucien, having been handsomely bribed by Spanish interlocutors. In 1806 Napoleon would handle things very differently. On 25 September he summoned the Spanish prime minister’s personal representative in Paris (Eugenio Izquierdo) and had the Treaty of Fontainebleau signed. Under the terms of this accord, French troops were to be allowed to transit Spain in order to invade and subjugate Portugal. As in 1801, the invasion would be supported by Spanish troops and once the nation had been occupied it would be partitioned (three-ways) and the spoils distributed. The quid pro quo was that the King of Etruria would be granted, in exchange for Tuscany, Portuguese territories between the Minho River and the Douro River (i.e. the Kingdom of Northern Lusitania) and, as the Queen of Etruria was another daughter of the Spanish king, Carlos IV, this was calculated to be both stick and carrot to the Spanish monarch.

Before the ink was dry on the Fontainebleau treaty, and certainly before its full ratification, the first elements of the First Corps of Observation of the Gironde, under the command of General Jean-Andoche Junot, had crossed the Pyrenees and headed west. Within six weeks Portugal had capitulated and, in the nick of time, the Portuguese regency and royal court had executed a well prepared contingency plan and fled to Brazil. The apparent ease with which this national conquest had been achieved prompted Napoleon to consider that the conquest of Spain would be a similarly straightforward affair. In so doing he underestimated the tenacity of the Spanish people, the power of the Catholic Church and the military and geographical challenges of subjugation, while overestimating the wealth and global influence of Spain’s empirical roots. Within months many more French troops had crossed into Spain. Some, under the command of General Guillaume Philibert Duhesme, had crossed the eastern Pyrenees into Catalonia and were clearly not destined for Portugal. The pretence was over. It was to be a few more months before the war officially commenced but Napoleon was now locked in a struggle that was to ebb and flow for the next six years.

Ironically, Napoleon’s long-term strategy in the peninsula would almost certainly have succeeded had he chosen to manipulate the Spanish Bourbon monarchy rather than replace it with his older brother Joseph Bonaparte. There were many in Spain who had tired of the ancien régime and desired change, as they had in France less than 20 years previously, but not under the jackboot of foreign subjugation. The backlash, when it finally came in Madrid on 2 May 1808, was more rebellion than revolution but it was enough to create the catalyst for a slow burning national revolt which triggered the Spanish War of Independence (La Guerra de la Independencia). The repercussions of Spanish rebellion and ensuing conflict were felt across the border in Portugal but with its military largely dismantled, following Junot’s invasion, their options were limited. Nevertheless, with Junot’s 26,000 men tied down in a nation of 90,000 square kilometres and with a 1,000 kilometre long coastline, the opportunities for foreign military intervention in Portugal were ripe. Britain, with its (by now) unchallengeable naval strength and unquestionable thirst for a military success on the European mainland, found the proposition of involvement in the peninsula an ideal platform from which to open an allied second front, tie down large numbers of French troops, deny Spanish naval resources (ships and ports), discredit French claims and aspirations to and in that country’s New World colonies and, perhaps most importantly, provide the nation an opportunity of taking the fight to Napoleon on a scale that, at the time, was not feasible elsewhere.

British intervention in Portugal in August 1808 led to a quick and decisive victory and the liberation of the nation. A month earlier a French corps under General Pierre Dupont had been beaten by a Spanish army at Bailén and with the French naval squadron captured in the Bay of Cádiz, the siege of Saragossa not progressing according to plan and the failed attempts to capture Valencia, Gerona and Rosas the French commanders had much to lament. Within months, however, Napoleon arrived in the Iberian theatre at the head of an additional 130,000 reinforcements and quickly turned the tide. The combined Spanish armies were comprehensively beaten at Espinosa de Los Monteros, Burgos (or Gamonal) and Tudela, Madrid was recaptured and the British army, under the command of Sir John Moore, was driven to the Galician coast and onto the waiting naval transports. Napoleon considered his demonstration complete and having left clear instructions to his subordinates about how to bring the Spanish nation to heel, he departed the theatre never to return.

At the point of Napoleon’s departure there were over a quarter of a million French troops in Spain. By 1810 that figure had risen to 360,000 and it was not until 1812, when Napoleon began preparations for his Russian campaign, that the number fell back to the levels of 1809.1 After Russia had swallowed up his Grande Armée Napoleon was forced to drain Spain and Italy for the defence of France and in order to conduct his 1813 campaign in central Europe. Despite this, Napoleon left over 200,000 men in Spain and on the Franco-Spanish border; this figure remained constant until his abdication in April 1814. Little wonder, therefore, that he dubbed his Iberian adventure the ‘Spanish Ulcer’. The Spanish numbers and contribution, often played down in British histories, was nevertheless significant. At the start of the war the Spanish army, despite being entirely unprepared for conflict, numbered about 140,000. Within months that figure had risen to 225,000 with the ‘regiments of new creation’ as they were dubbed.2 Their strength remained fairly constant throughout the war, despite a number of significant defeats, and by March 1814 the six Spanish armies numbered just short of 200,000 men. The figures and contribution of the Spanish guerrillas are more difficult to tie-down. As the war progressed, the guerrilla movement grew and so did the number of guerrilla bands. According to René Chartrand, a British report in 1811 listed 28,000 but as this information in many cases only denoted the guerrilla leader’s name and not the strength of his force, he estimates that the overall figure might be nearer 35,000. 3 In the latter stages of the war many of the larger guerrilla groups were militarised and absorbed into the wider Spanish army.

The British army in Iberia under John Moore numbered about 30,000 and the same number of troops were provided to Sir Arthur Wellesley (soon to be Viscount Wellington, and before long the Duke of Wellington) when he returned in 1809 – see below. This number remained fairly consistent until 1812 when Wellington received considerable reinforcement (about 15,000) to his main army and with the arrival of the forces on the east coast from Sicily. It is important to note that from the end of 1809 until the end of the war the British army no longer operated independently; it had become an Anglo-Portuguese army with a combined strength of about 60,000. In 1808 the Portuguese army had to be completely reconstructed and reorganized and the Portuguese turned to Britain for help. The task fell to General William Carr Beresford, the illegitimate son of an Irish peer and former commanding officer of the infamous Connaught Rangers (88th Foot). He was completely successful and by the end of 1809 the Portuguese regular army numbered 30,000 and rose, by the end of the war, to just over 50,000 men (although the component with Wellington’s main army remained at, give or take, 30,000 men). In sum, therefore, when combined with the Spanish army and guerrilla numbers the total allied force in Iberia was about 300,000 men; a figure not that dissimilar to the French total. Generally less well recognised is the fact that a quarter of these overall numbers, nearly 150,000 men, were locked in the struggle for the east coast of Spain.

In the immediate aftermath of Moore’s harrowing retreat and his death on the field of battle at Coruña, the likelihood of a British ‘return’ was doubtful. Wellesley, the commander and architect of Britain’s military success in defeating Junot in Portugal the year before, maintained that Portugal could continue to be defended by a force of 30,000 men and would, in the process, tie-down at least three times that number of French soldiers. His proposals, supported by Lord Castlereagh the Secretary for War, were endorsed by Prime Minister Portland’s Cabinet and within weeks another British force had been despatched. For a second time Portugal was liberated and the subsequent link-up with the Spanish army of Estremadura resulted in a hard fought victory at Talavera in July 1809. Any optimism was, however, quickly dispelled as three French corps moved in support of Marshal Claude Victor’s and General Horace Sebastiani’s defeated corps and the defence of King Joseph (the elder brother of Napoleon whom he had made King of Spain) in Madrid. Wellington, as Wellesley became following the allied victory at Talavera, withdrew with his small British force to the Portuguese border. News began to filter through of a catastrophic defeat of the Austrian army at Wagram in early July and that the British expedition to Walcheren, an attempt to open a second (British) front in Europe, was faltering badly. The Fifth Coalition against France had, to all intents and purposes collapsed. Within weeks, the catastrophic defeats suffered by the Spanish during their autumn campaign, drove Wellington deep into Portugal and suggested a rethink of Anglo-Spanish combined operations. It was to be a long winter but Wellington used the time to train and re-equip the Portuguese army and from 1810 onwards it was an Anglo-Portuguese force until the end of the war.

By early 1810 Napoleon’s objectives in Iberia had carved two strategic axes of advance and corresponding lines of communication, the first from Bayonne to Madrid and on to Lisbon, the second from Bayonne to Madrid and south to Cádiz and Gibraltar. The former axis placed the Grande Armée on a collision course with the newly fashioned Anglo-Portuguese army under Wellington, while the latter axis resulted in more of an allied collaborative defence; protecting Spain’s executive stranded at Cádiz and Britain’s maritime and trading interests at Gibraltar. Two additional struggles were playing out on either side of these axes: the first was in the north of the country and along the Cantabrian coast, the second was in Catalonia and along the Mediterranean east coast. Britain’s involvement in these two regional struggles was, in the main, restricted to Royal Navy support and seadenial patrolling. However, it was that very sea supremacy, coupled with the extant road network and the absence of any French troops in the east coast region that enabled Spain to utilise, unhindered, the Mediterranean ports of Tarragona, Valencia, Alicante and Cartagena as logistic hubs supplying the Spanish armies and her people. Napoleon cited this as one of the principal reasons for French failure to subdue the population, decisively defeat the Spanish armies and to drive the troublesome British from Iberia. Accordingly, in late 1810, he issued orders to General Suchet to commence operations and capture the key cities and ports. The battle for the east coast had begun.

The Iberian Peninsula – French Axes of Advance 1810