1r.3 que

1r.3 que  1r.2 qual

1r.2 qual  1r.12 quales

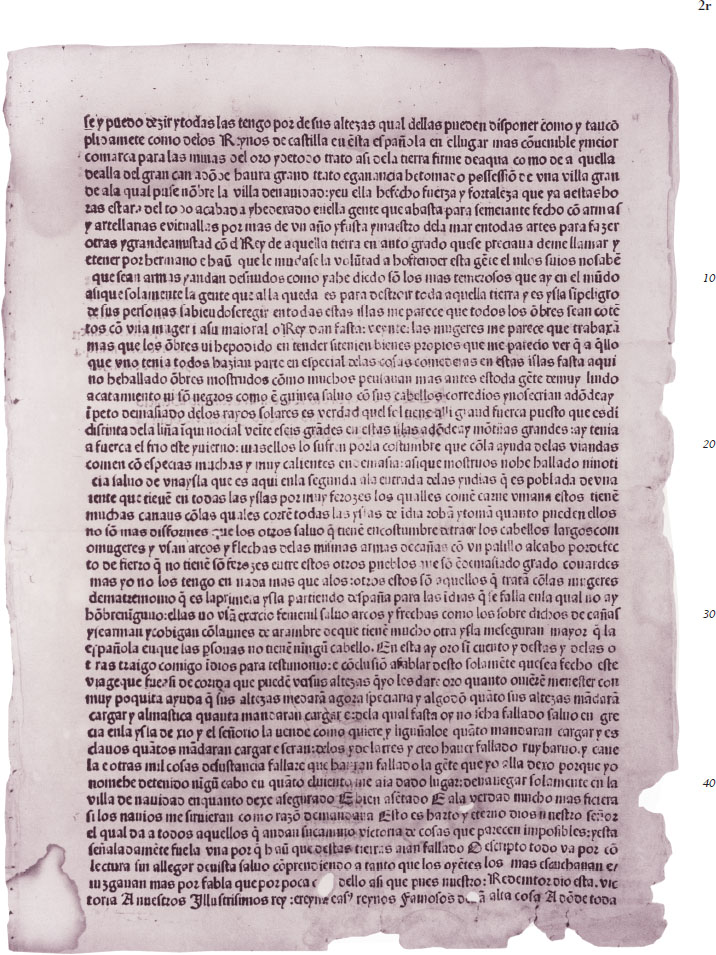

1r.12 qualesThe physical evidence of the Folio impression speaks to practices in early print period culture and presents interesting problems in bibliography.1 The men who created the fifteenth-century texts of Columbus’s Letter gave no particular value to consistent punctuation or spelling or to the placement of capital letters (initials, upper-case letters). They might write or set as one word what today are two or more words; or words might be set down in a casual and convenient form of scriptio continua, without space between; or what today is considered one word might be given as separate (or separate-looking) words — and the items may appear inconsistently from instance to instance.

For example, the Folio compositor tends to set what are now considered separate words as one: in ala (1r.8); enla and dela (1r.11); and deno (1r.16), for example. In other instances, his setting without word boundaries observed by spacing might have the practical rationale of fitting characters into the line, as in sabersihauia (1r.17) and pierdenlafoia (1r.28).2 The Folio and Quarto compositors’ results suggest that some word boundaries were a moveable feast: where the Folio reads andadolos (1r.7), the Quarto reads andado los (1r.11); where the Folio compositor sets marauillosamente (1r.7) and solamente (2r.11, 33), the Quarto’s compositor sets marauillosa mente (1r.10) and sola mente (3v.7; 4r.11–12); where the Folio compositor sets pidiendogela (1v.6), the Quarto’s compositor sets pidiendo gela (2r.20).3 Reading the text aloud, especially where a puzzling setting appears, will help to make sense of the words.

These and other kinds of orthographic variants may bear on ideas of a manuscript’s author or scribe or on a compositor’s identity in a printed piece. Though the edition’s notes intend to be silent on purely orthographic variants among the Spanish texts, some of these variants suggest insights that will be useful in further research, and a familiarity with them will facilitate a smoother reading of what may appear to be quirky texts.

Certain variations are fairly regular in these texts while others appear to be less predictable:

Additional spelling distinctions involving consonants may indicate phonological uncertainty or difference. The manuscript gives plaser (1r.1) and dezir (1v.91) while the Folio and Quarto give plazer (1r.1 in both) and the Folio gives desir (1v.40) but the Quarto gives dezir (3r.23). The Folio (2r.41, 42) and Quarto (4r.24–25) give ficiera and razon where the manuscript gives fiziera and razon (both at 2v.144).10 Both the Folio and the manuscript give fazen, azero, and vezes (1r.43 and 1r.46 in both texts). The Folio reads segun (1v.39) where the manuscript reads segund (1v.91, 94; 2v.154), and the Folio has ningun (2r.32, 40) where the manuscript has ningund (2r.133, 142). The Quarto gives mill (1v.10, 4v.9) for the Folio’s mil (1r.27, 2v.5), and where the Folio has vitoria (1r.1), the Quarto (1r.2) reads victoria, restoring the Latinate consonant cluster.

Another set of orthographic variants reflecting consonant variation or vacillation is what is known as f/h/ø (efe, hache o nada). The texts reflect the orthographic freedom — and probably the oral/aural uncertainty — of the period and perhaps the absence of hierarchical value placed on certain choices; nevertheless, there is some tendency toward the suppression of /h-/ in the manuscript writer’s approach.11 Where the Folio gives h- in words such as haura (2r.4), horas (2r.5–6), and harto (2r.42), the Simancas manuscript gives abra (2r.103), oras (2r.105), and arto (2v.144); oras may be considered a hypercorrection, suppressing h- even though the Latin hora has it. Where the Folio gives haunque and hoffender (both, 2r.9), along with hun and huna (both, 1v.33), perhaps indicating a speaker who occasionally places an exhalation (a breath, a “rough breathing”) at the opening of certain words beginning with vowels, the Simancas scribe writes aun que (2r.108–109), ofender (2r.109), and vna (frequently), respectively.12 The Folio, Quarto, and the manuscript concur, however, in giving he (F. 2r.6; Q. 3r.31; and MS 2r.105, for example) and he fallado (F. 1r.41; Q.1v.32– 2r.1; MS 1r.40), along with fecho (F. 2r.6; Q. 3r.32 ; MS 2r.106).13

The Quarto, too, shows the tendency to suppress the Folio’s h- (ø), but it may become f- in the Quarto. Some of the previous examples will illustrate: the Folio’s hun and huna (1v.33) are vn and vna at Quarto 2v.31; the Folio’s haunque and hoffender (2r.9) are avn que and offender, respectively, in the Quarto (3v.4, 5); and where the Folio gives haura (2r.4), the Quarto produces aura (3r.28). An instance of hecho in the Folio (1v.2) is given as fecho in the Quarto (2r.13). Their compositors concur, however, in giving hallado (Folio 2v.10–11; Quarto: 4v.17), fasta (Folio 1r.16, 20; Quarto 1r.25, 32), and fuyan (Folio 1v.1; Quarto 2r.12), and in recording alike fecho and fecha (Folio 2r.5, 6, 33; 2v.4, 5; Quarto 3r.30, 32; 4r.12; 4v.8 [fecho and fecha], 14, and 22). While these orthographic comparisons are not exhaustive, and other researchers may find more meaningful patterns with close study, they serve to raise the reader’s consciousness about the nature of certain kinds of variants and to indicate some of the more obvious distinctions and likenesses between and among texts that have been presented as “servile” copies of one another. They also indicate how “copying” may affect a text.

Word abbreviations in the Folio, Quarto, and Simancas manuscript are of two kinds. Some are word suspensions, where the word is shortened by the omission of final letters that are signaled by a graph (in the sense of a “visual symbol”). Others are word compressions where one or more internal letters are suppressed and signaled by a graph.14 Extensions of word suspensions and compressions in this chapter and in the edition are shown in italics except where the word is already given in italics as a part of a quotation, and in these instances, underscoring indicates the extension.

Among the devices signaling extensions in the Folio is the signaling que (1r.3, for example) and in ñro signaling nuestro.15 A stylized, biting abbreviatura based on scribal styles for Latin quem [which] signals qual and quales (1r.2, 1r.12).16

1r.3 que

1r.3 que  1r.2 qual

1r.2 qual  1r.12 quales

1r.12 quales

An omitted nasal consonant, m or n, as in ombre or onbre (both for Mod. Sp., hombre), may be indicated with the bar or tilde over the preceding letter in words such as cõ = con, dõde = donde, señor = sennor, and the examples shown below.17

1r.41 hombres

1r.41 hombres  1r.38 traen oro en

1r.38 traen oro en

1r.13 pensando

1r.13 pensando

The tilde set over c (shown in creh- from 1r.37) and p with a horizontal bar through the descender may indicate additional extensions (such as er, re, ar, ro) in the Folio, leaving the reader to determine the correct one by context, as in the examples below.18 At Folio 1r.2, por is set using this method, but the compositor has set –or with it, and he repeats this setting with por at 1v.44.

1r.2 por

1r.2 por  1r.37 creh-

1r.37 creh-  1r.47 para

1r.47 para

1r.36 paracriar (para criar)

1r.36 paracriar (para criar)  1v.6 la persona

1v.6 la persona

1v.20 perdido

1v.20 perdido

The compositor avails himself of several shortcuts in setting comprehender que (1r.29), shown below.

1r.29 comprehender que

1r.29 comprehender que

Critical scrutiny of certain lower-case types used to set the Folio contributes another layer of understanding to the study of the Letter’s history and to an informed reading of the printed text. The apparent mixing of fonts, or “sorts,” in the Folio represents what was probably a universal printing practice at the time,19 but as mentioned in chapter 2, damage and conditions of printing can produce distinctions among impressions of types from the same font.20

Among the lower-case types, the rotunda d, sometimes called “round” or “uncial” and set in type approximately as ∂, offers a productive context for close observation of types and for reading practice. This type, mentioned in chapter 3 for its variations in the Folio, has a rounded or oval bow with lines connecting at angles around the perimeter. The examples below suggest at least three designs of ∂. At 1r.4, straight-line segments on either side of the base meet, standing the letter on point at the baseline, an element that is especially clear in the first example but somewhat obscured in the second. The feathered impression at 1r.1 may cloud that feature, but the letter seems to be essentially round in the bow and thicker around the perimeter than the previous examples.

At 1v.1, ∂ in padre has a tiny ascender flourish similar to that in grand at 1r.1, but padre’s example is different in other respects: the thin, barely curved ascender attaches to a bold, curvilinear head stroke that quickly turns downward, becoming narrow and flat, reaches its thinnest point, and angles into a straight-line segment whose point touches the baseline and turns up as a single, broad curvilinear segment that stops just short of the cusp, leaving a slight opening where a hairline-thin ligature may be visible. This latter trait appears in the ∂ of delo (1v.5), too, but the two designs are otherwise distinct. The hairline and opening are the kinds of features that ink and paper interactions, damage, or debris might obscure.21 The ∂ of segunda (1r.7) may be a damaged and more worn fellow of the example that begins dellas (1r.4).

1r.1 ∂ (grand)

1r.1 ∂ (grand)  1r.2 dado

1r.2 dado

1r.4 dellas todas

1r.4 dellas todas

1r.5 –dida

1r.5 –dida  1r.7 segunda

1r.7 segunda

1v.1 aguardar

1v.1 aguardar  1v.1 padre

1v.1 padre  1v.5 delo

1v.5 delo

The impressions of “straight” or “upright” d in the Folio have typographical interest as well. The suffix –dida (1r.5, above) shows d with its right finial thorn apparently worn or chipped away, as is that of d in dias (1r.2, shown below with other examples). At 1r.19, the ascender of d in indios shows a forked (textura) finial with distinct thorns and an angled foot stroke, the latter like those of the upright d of –dida and dias. The upright d of delos at 1v.14 (below) is akin to other examples in its thorn, but the type makes a slightly narrower impression around the bow, and its foot looks filled and flat, possibly rounded. Examples from 1v.36 (dela) and 1v.32 (dediez) cloud the matter of difference further. Those of dediez appear to have more open bows (white space, counters) than do other examples, but the imprints of both ascenders suggest that they are — or were — like those in other examples, perhaps with more damage, and the feet are indeterminate, either damaged or so designed. Apparent hairlines at the lower cusp between the bow and ascender suggest differences between the examples of dediez and others shown here. Two styles of d, with the second represented in dediez, may be represented in the Folio, or all these may come from the same font. Also note in these examples that some impressions of i show a serif (í) while others do not, probably indicating distinct fonts or loss of the serif.

1r.2 dias

1r.2 dias  1r.19 indios

1r.19 indios

1v.14 delos

1v.14 delos  1v.36 dela

1v.36 dela  1v.32 dediez

1v.32 dediez

In addition to its two styles of d, upright and rotunda, the Folio gives two styles of r and two of s, all common in gothic fonts of the period and all derived from manuscript culture. The round-s (rotunda, curly-s) and upright-r are those of today’s printed materials, but the long-s and rotunda-r may be new to readers unfamiliar with older printings.

The element distinguishing f from long-s, is the smooth ascender of long-s. Long-S is smooth or has a slight bump on the upper left (back) side while f has the customary horizontal bar through the ascender, as the examples in falle asi (1r.11) and fasta (1r.16) show.

1r.11 falle asi

1r.11 falle asi  fasta (1r.16)

fasta (1r.16)

Both long-s and round-r appear in sabersi (1r.17), and a slightly different long-s appears in asi at 1r.23 compared with that of falle asi at 1r.11. The flattened base and hairline curve toward the terminal of the first long-s in sabersi and that of asi (1r.23) differentiate them from the second example in sabersi.

1r.17 saber si

1r.17 saber si  1r.23 asi

1r.23 asi

The first example in sabersi and the sole example in asi (1r.23), then, are from different fonts. Compare the higher-angled, shorter upper section of long-s in asi (1r.23) and the thickness and shape of the straight-line section of its ascender with those features in the first long-s of sabersi.

The long-s types in sant saluador (1r.6), shown below, are distinct, and the second example comes from a slightly larger font.

The rounded foot of the example in sant is more like that of the second example in sabersi (above). The quality of the imprint of the upper curve in the long-s of sant and its rounded upper terminal may be due to wear, so the second example in sabersi and that of sant may come from the same font.

The rotunda r in saluador and sabersi (above) bears notice because in saluador, it is set as it should be, but in sabersi, r has been turned; the turning does not disrupt the line of type vertically, however, because the grapheme sits at the center of the body.22 Additional examples of round-r appear at 1r.1 (below), and they may come from the same font.

por 1r.1

por 1r.1  nuestro sennor 1r.1

nuestro sennor 1r.1

Both long-s and rotunda-r have the advantage of being economical graphemes, compressing writing space in print as they do in pen and ink.

The foregoing examples present several o types with differences and matches among them. The o types of nuestro sennor (above), for example, represent one — perhaps two — of at least three different o types in the Folio. Below, compare the tiny, oval o with a decorative center at 1v.1 (in los) with that at 2r.27, where o has a slightly different shape and embellishment. They are suggestive of one another, and their seeming distinctions are probably unsubstantial.

A third, larger o with a decorative center appears in enotrotermino (1r.30) with two other sorts of o, and its middle example may be a turned and soiled version of that seen in ferozes at 2r.27. At 1v.3, como has two sizes of o that reappear nearby in 1v.5, in the words no, lo, sino, and quelo. Like examples of round d (∂), the o type stands on point.

1v.1 (los)

1v.1 (los)  1r.30 enotrotermino

1r.30 enotrotermino

2r.27 (ferozes)23

2r.27 (ferozes)23  1v.3 como

1v.3 como

1v.5:  no lo

no lo  sino

sino  quelo

quelo

While Spanish no longer uses rr- (erre perruna) at the beginning of a word, it is commonly used in 1493, as it had been for centuries. The manuscript gives rr- dependably, but the Folio gives rr- only in uanderarreal (1r.5), shown below, and rrios (1r.25, not shown).

1r.5 uanderarreal (bandera real [royal banner])

1r.5 uanderarreal (bandera real [royal banner])

Reading capital R as geminate (as RRey for example) is arguable because of the shadow staff, but such a resolution appears to be unjustified by the evidence of the Folio.

A related problem in editing the Folio appears at the end of 1r.1 where a light impression of a tidy, superscript, upright r follows sennor, well within the printing space of the line. A superscript character usually signals a word compression to be recognized and extended by the reader, and here, the result would then be sennorr. The figure may be pen work, however — perhaps the notation of a nineteenth-century reader who had figured out the rotunda r and made an interpretative note — rather than a stray impression. The grapheme does not comport with the r types used in the Folio, as shown by a comparison with examples of the Folio’s upright r, and the strange grapheme is pale by comparison to impressions in this area of the recto.

1r.1 sennor

1r.1 sennor  1r.1

1r.1  1r.3

1r.3  1r.12

1r.12

Minim types (i, m, n, and u) may present certain reading problems, especially where they coincide within words, because inking, damage to types, and depth of impression may affect the distinctions among them.24 Some ambiguous imprints of n and u in the Folio may owe to these factors, too, but n and u types may be set upside down, as the Folio examples (below) suggest.

1r.6 no[n]bre (for Mod. Sp. nombre)

1r.6 no[n]bre (for Mod. Sp. nombre)

1r.13 de[n]o

1r.13 de[n]o

Regular setting of inverted types suggests a foul case, and the lack of correction, an indifferent or impaired compositor (or no corrector), along with a foul case.25

The Folio’s n types are distinguished from u types by having a steeply angled hair-line ligature connecting the two minims at the upper end, a flat foot on the straight minim, and an angled (lifted) foot on the curved minim, as shown definitively in Iuana (1r.9), shown below.

A well-formed u type, like those in leguas (1r.23), above, and the u of hauria (1r.37, below) are distinguished by arrow points or half-arrow points at the heads of the minims. The straight (right) minim of u, like the curved (right) minim of n, finishes with an outward angle at the base, like a foot flexed upward at the ankle. The u of muchas (1r.39) is less clearly impressed, but the flexed foot on the straight leg, the open area between the heads of the minims, and their slight angles clarify the reading. Note the series of u and n types in aqui no hauria crehencia sin, shown below.

aqui no hauria … 1r.37

aqui no hauria … 1r.37

1r.39 muchas

1r.39 muchas  1r.39

1r.39

The edition indicates Folio types perceived as turned by setting the supposedly correct type in brackets, as at 1r.44, where I read the graphemes as dispnesta and edit as disp[u]esta, showing the supposed intention (u) rather than my perception (n) within brackets.

The small m, like that in muchas, above, seldom gets a full impression, and its connections may be barely visible. The m type may be easily misconstrued at first glance, as may n and u even when they are not turned, as in numero (1v.1), below, whose r is also misleading.

1v.1 numero

1v.1 numero

Impressions of b and h are scantily distinguished by a tiny opening between the feet (of the ascender and limb) of h that may be obscured by inking, as in the example of hauia at 1r.17, where h- may be taken for b. Note below the examples of h that preserve the opening and the suggestion of a supporting bit of metal between the bow and the base of the ascender, as in hauia (1r.17). See further examples below.

1r.19 harto

1r.19 harto  1r.17 hauia

1r.17 hauia

1r.14 hauia

1r.14 hauia  1r.16 bolui

1r.16 bolui

Though they are unproblematic for reading, the Folio’s g and y types are interesting for their contrasting styles and purposes. The g consists of a series of filled straight lines, hairlines, connecting angles, and spacious, balanced bows. The loop or descender, held by a barely visible hairline ligature to the left corner of the head stroke, sweeps down the back of the bow (or counter), thickening at the turn and moving down and up in approximately equal lines to mimic the shape of the upper space. The shape of the bow and inner loop and detail of the serif in each example may suggest distinctions between and among examples.

g 1r.1

g 1r.1  g 1r.7

g 1r.7  g 1r.9

g 1r.9  g 1r.38

g 1r.38  1r.43 g (algodon)

1r.43 g (algodon)

The narrower, predominantly straight-line style of the y distinguishes its design principles from those that inform the d and g types, and its restrained features produce a highly economic result. The y’s upper arms sit close together, the right finial reaching toward the left arm and nearly closing the space between them. The descender runs down from the right arm at a steep angle and ends in a curled finial that counterbalances the descender’s trajectory. The apparently broken arm at 1r.5, the lack of the lower finial at 1r.4, and the light impression of the descender at 1r.3, along with other examples of y, suggest much use.

1r.3

1r.3  1r.4

1r.4  1r.5

1r.5

The spirit of printshop economy, embodied literally in rotunda r, long-s, and y types, is augmented by the use of graphemes cast together on one body as ligatures. Ligatures conserve space on the line — and therefore, paper — and the compositor’s movements in setting and in distribution. The economic long-s doubles its economy in ligature types -ss- and -st, both represented in the Folio.

Below, see esta (1r.2), costa (1r.14), fasta (1r.16), and esta (1r.21) for st ligatures. The angled, heavy bar seen in esta at 1r.2 recalls that of nuestro’s ligature at 1r.1, shown above. The st of costa (1r.14) shows the curve set high on a thin ascender, similar to those of esta (1r.21) and fasta (1r.16), where ink and paper factors may account for minor distinctions.

1r.2 esta

1r.2 esta  1r.16 fasta

1r.16 fasta  1r.14 costa

1r.14 costa  1r.21 esta

1r.21 esta

A geminate long-s ligature, pointed out to me by Peter Stinely, Printshop Master at Colonial Williamsburg, is used to set illustrissimos (1r.3), where three ligatures (ll, st, and ss) are in evidence.26 The pair of -ss- ligatures used in possession (1v.47) are unlike those of fortissimas (1r.24) and illustrissimos, whose -ss- ligatures may have distinctive features between them — though some of these perceived differences may be due to press work and type wear.

1r.3 illustrissimos

1r.3 illustrissimos

1r.24 fortissimas

1r.24 fortissimas

1v.47 possession

1v.47 possession

A second example of possession (2r.4) shows two ss ligatures that appear to be from the same font as those used at 1v.47 but with distinctive wear to the types.

2r.4 possession

2r.4 possession

The geminate ll of Spanish is also likely to be a single type in words like illustrissimos (1r.3, above) and falle (1r.11), where the space set around ll, compared with the tidy space between the graphemes, suggests them as ligatures. In some — perhaps many — examples, no physical ligature is visible, for which note palillo (printed pa lillo) and aquellas at 1r.46, where ligatures seem likely. Possibly in della (1r.10) and certainly in ello (1r.43), a physical support prints between the two graphemes.

1r.46 pa lillo

1r.46 pa lillo  1r.46 aquellas

1r.46 aquellas

1r.11 falle

1r.11 falle  1r.10 della

1r.10 della

1r.43 ello

1r.43 ello  1r.31 alli

1r.31 alli  1v.3 de

1v.3 de

The Folio gives a few examples of less frequent ligatures like the “biting” ligature at 1v.3 in de. This biting ligature appears outside de, too, but most encounters between d and e in the Folio are separate types.27 The reading of a and l in algodon (1r.43, below) may be set from a ligature, and the impression of calidad (1r.30) suggests it for an al ligature as well, but the tightness of these settings may have other rationales.28

Small initials stored in the compositor’s uppercase are used in early printing to set titles and section headings, to signal text divisions, and to begin some proper nouns, and they are the most frequently encountered initials in incunabula texts. Hairlines or shadow lines enhance the essential contours of small gothic initials like those used to set the last four letters of SENOR (1r.1), and their serifs and finials are likely to be more prominent than those of other types. Initials, like minuscule types, may have their features obscured or made more prominent by factors of ink, paper, and moisture, and their embellishments are prone to wear, damage, and loss. On examples of A that are shown below, the details of the feet, bar, and serifs show close resemblances, despite the absence of a left-foot extension on A at 2v.14 and the distance between the feet of the example at 1r.6.

Among initial types used in the Folio, A appears to represent a design style characterized by the thickness, curvilinear details, and rounded feet and finials common to E, F, I, L, S, and T. It is also notable that A and S types show a tiny rhombus at the bar of A and at the meeting of the curves of S. A second grouping based on design includes D, H, M, N, O, and Q. These are distinguished by parallel hairlines supporting negative space and generous bows (except in H).

R, somewhat in a class by itself, is compatible with the first group for its rounded serif or terminal, like that off the shadow ascender of L; because of its conservative bow and curvilinear leg, its design works with the D group as well. The Q type is another interesting mediator between these designs with its rhombus-shaped foot suggesting its relationship to A and S.29

Impressions of initials E, F, I, L, and O present variations like those shown for A, but they probably come from the same font. The first L (2v.1) shown may have damage or loss on both ascenders, a supposition on condition supported by the lack of the hairline attaching the rounded finial at the head. Belonging to neither or to either group, the two C examples shown present distinctions in the curves of the spines and heads and in the cusps where the heads and spines join. These differences and a possible difference in body size — very slight — suggest these two examples of C as coming from two fonts.

A 1r.6

A 1r.6  A 2v.7

A 2v.7  A 2v.14

A 2v.14  A 2v.16

A 2v.16

C 2v.7

C 2v.7  C 2v.8

C 2v.8

D 2v.15

D 2v.15  D 2v.16

D 2v.16

F 2r.47

F 2r.47  F 2v.6

F 2v.6

H 2v.15

H 2v.15  I 2v.15

I 2v.15  I 1r.9

I 1r.9

L 2v.1

L 2v.1  L 1r.35

L 1r.35

M 2v.5

M 2v.5  N 1r.1

N 1r.1

O 1r.1

O 1r.1  O 2v.16

O 2v.16  O 2r.44

O 2r.44

Q 1r.9

Q 1r.9

R 1r.3 (Rey e Reyna)

R 1r.3 (Rey e Reyna)  R (or RR) 1r.1

R (or RR) 1r.1

S 2v.14

S 2v.14  S 2v.16

S 2v.16  T 2v.14

T 2v.14

At a level above the small initials are large, framed, and embellished initials produced as woodcuts. In chapter 3, the framed S that opens the Folio was treated from a comparative and historical perspective in the context of is its ownership and control on a particular day in 1493. This discussion, on the other hand, considers the framed S as a piece of early print culture material, scrutinizing its visual effects and physical properties and comparing it in these contexts to its counterpart in the Quarto.

The initial’s maker achieved its printed effect by the principle of reverse printing, where “white” space (surrounded by ink) holds the reading message of the grapheme — here, the Folio’s S. This technique also creates the foliate design around the S, along with the interior layer of the frame. The design elements lie below the inked printing surface and come from the press in the color of the paper. The designer’s handling of the foliation shows his characteristic style: the vining never crosses over the grapheme, but the artist achieves organicity by using the concave, bracketed serifs at both ends of the initial as the source of the vining that shadows the interior curves of the initial and fills the frame. The tendency to curvilinear design, the separation of the grapheme from the vining, and the open, slightly drooping acanthus facing the front of the design in the lower space are distinguishing features of this engraver’s work.

Folio 1r. framed S

Folio 1r. framed S

Something is amiss in two places along the upper ridge where the impression has laid down ink along the white space of the interior frame. If the lacunae in the impression are due to loss and breakage, perhaps they indicate that the printer found a favored and useful go-to piece in this initial despite its imperfections.

A brief consideration of the two framed S initials that open the Spanish printings suggests convergences and differences in conception and influence reflected in the designs of early printing materials. The Quarto’s stylized S is enclosed by four levels of framing and shaped by thorny stems sprouting leaves and vines along the curves and ending in open flowers at the initial’s four terminals. At the center of the S, two open flowers suggesting the lily almost meet around a tiny, crooked rhombus with a dark, irregular center. The Quarto’s frame is ornamented by floral stems of various shapes emerging from each corner toward the initial. The design is reinvented at each space, with no effort at side-to-side, top-to-bottom, or corner-to-corner symmetry. A background filler consisting of various shapes adds interest to enclosed areas. The impression suggests that areas of loss may exist around the frame.

Quarto 1r. framed S

Quarto 1r. framed S

Capitals, punctuation, and spacing are probably more likely than other features of medieval manuscripts and printed texts to try the reader’s patience, and this discussion will both describe some of these and indicate how medieval punctuation (pointing) is represented in the edition in chapter 8. Little correlation exists between the usage applied in these texts and today’s practice. The reader of the Folio immediately notices that the first word of the Folio is set in initials (“all caps”) and on the next line, a small initial A (1r.2) appears in mid-sentence, followed quickly by the place name indias [Indies] (1r.3), set with lower-case i. In subsequent lines, Isla, not part of a proper name (1r.4, 20, 21), gets an initial, but place names like san salvador and santa maria open with lower-case types. As today’s reader might expect, initial-A opens what may plausibly be construed as sentence openings at 1r.6 and 1r.7, and at 1r.8, Q (Quando) begins a sentence.

In what appears to the modern eye as an irregular practice, a punctus is set at the close of what might be construed as a periodus, but no capital letter follows it at 2v.10.30 A punctus that has no discernable reading or grammatical application appears at 2v.8 where it stands between de and Castilla: estando en mar de. Castilla salio [while sailing in the Sea of Castilla, there arose …]. At 1r.7, a break in sense and grammar falls in the midst of three words set in lower-case types and printed as one word: andadolos (Mod. han dado. Los).31

A punctus may also be used to set off Roman numerals from text, disambiguating the minims and alphabet characters of the numeral from those of the text. This disambiguating use of the punctus may be the reading at line-end on 1r.22 following oriente [east] and just before a numeral at the head of the next line, yet no punctus follows the numeral.32 At 2v.5, the Letter proper closes with a double-duty punctus; it is the second of the pair used to set off the Roman numeral characters that make up 1493 (Mil. cccclxxxxiii.). The punct s of the Quarto, unlike those of the Folio, are rhombus-shaped, and the Quarto uses them with consistency to set off numerals. In the notes to the edition, a punctus that falls at the close of the variant is followed by the explicit “[punctus].”

s of the Quarto, unlike those of the Folio, are rhombus-shaped, and the Quarto uses them with consistency to set off numerals. In the notes to the edition, a punctus that falls at the close of the variant is followed by the explicit “[punctus].”

2v.5 1493

2v.5 1493

Above and to the right of the punctus, a vague mark makes an impression following oriente at 1r.22. Though this bit of ink may be unintentional, taken together with the punctus, it suggests the punctus elevatus, a mark of punctuation that took the force of the modern colon, signaling a significant pause before an explanation or direct speech that was to follow.

1r.22 oriente[.]

1r.22 oriente[.]

One form of the punctus elevatus is something like a superscript comma, rotated just short of 180 degrees and set above a mid-line punctus. This description does not exactly fit the graph following oriente — but the use of the punctus elevatus accords with the syntax at 1r.22–23, where Columbus tells how far he has sailed eastward around the north coast of La Española: just the number of leagues he had earlier sailed east along the coast of Juana. Interestingly, the last marks of punctuation in the Folio at 2v are two points set one above the other like the modern colon, an alternative sign for the punctus elevatus. In each case on 2v, this mark suggests a pause before a clarifying declaration. In the notes to the edition, where I read the punctus elevatus in the Simancas manuscript, it is represented with a modern colon (in italics) and is explicitly noted as “[punctus elevatus].”

Though none appears in the Folio, the Quarto uses the virgula suspensiva (/) and the manuscript may do so, too. In the Quarto, the virgula suspensiva is a short, vertical bar, its upper end tipped to the right; it signals a grammatical and/or reading pause in the text. The Quarto’s virgula suspensiva does double duty by modern standards, indicating in some instances a brief, medial pause like that signaled by the modern comma, and elsewhere, a full stop, like that called for today by a period or semicolon. In the notes to the edition, where a variant closes with a virgula suspensiva, the symbol is shown as / and is followed by the explicit notation [virgula suspensiva].

Along with its handling of punctuation and capital letters, the Folio’s setting and spacing of words and graphemes and its justification of margins seem lawless by today’s standards. Lines frequently show inconsistent internal spacing and a good number of lines extend beyond the ostensible print area. What are perceived today as two or more words may be set as single words joined together (agglutinated), written as one might speak them; what one expects to see today as single words may be printed as if they were several words; and words may be divided without regard to syllables. These settings depend on the necessities of the line in composing rather than on syllabic division or word boundaries, and reading aloud will usually resolve a difficulty. An interesting example of spelling and word division occurs at the head of 2r.33, where t ras, shown below, continues otras [others] from the previous line (2r.32), where o is orphaned at line-end without a hyphen.

2r.33 [o]tras

2r.33 [o]tras

Another striking example of crowded words and ambiguous line-end division occurs at 2v.12 where the reading is marqia, with an extremely faint horizontal bar over q. The reading is mar que ia(mas) [sea that never], with the second syllable, -mas of iamas (Mod. jamás), set on the following line.

2v.12 marqueia

2v.12 marqueia

The lack of the hyphen at line-end is usual in vernacular texts of the Middle Ages, and word divisions may go unmarked in Latin printings, too. In Plannck’s “F” edition, hyphens indicate some divided words, and other words are broken without hyphens: Raphaelem, simul, and iuxta are broken without hyphens while most word divisions at 1r give hyphens. At 1v, operiri, habitationes, orientem, prospexi, and hispanam lack hyphens. In the Latin quartos, word divisions are generally well-defined, but in Plannck F at 1v.11, the final words of the line are virtually scripta continua, a setting that fits the words into the line.

Hyphens may be represented as “double-stroke” hyphens, two parallel lines tipped upward at their right ends, like those of the Quarto, or by a single stroke at a steep angle, like those of Plannck’s F Quarto.33The hyphen’s angle conserves space on the line.

Like the Folio’s wayward spacing and word divisions, its uneven justification and “falling” and “jumping” types catch the reader’s attention. Theodore De Vinne notes that when early pressmen locked up the formes, a task “roughly done,” the result frequently made the types “crooked, springing them off their feet and making the spaces [blank pieces of metal set in below the print area] work up” (527). The word indios (1r.19, shown at p.134) has its last two types print slightly awry, and the setting of marquia (2v.12), described and shown above, gives more extreme results. At 1r.27, various letters have fallen too low to print more than shadows of themselves, and the baseline is erratic.

1r.27 frei todas fermosissmas

1r.27 frei todas fermosissmas

Another example occurs at 2r.42, where the first two letters of nuestro are some distance apart and on different planes.

2r.42 nuestro

2r.42 nuestro

At 2v.11, the second x type (xxviii), widely spaced from the following numeral, prints but appears to have loss to the face. A similar result is achieved in the shadow imprint of the second x at 2v.12 (xxiii).

2v.11 xxviii

2v.11 xxviii  2v.12 xxiii

2v.12 xxiii

The Folio’s most egregious instance of types moving out of expected configurations and a significantly marred right justification converge in this area of the last verso. At 2v.11, two types (e and n) extend beyond the supposed justification line, and the n has made a serious slide. One line down (2v.12), two types, i and a, as described above, exceed the vertical margin and are evidently forced downward as the formes are locked up.

2v.10–13

2v.10–13

While reading the Quarto is relatively straightforward, its compositor uses several abbreviatura that merit mention. One of these is the Tironian et (a sort of stylized 7 that may have a stroke through the leg or limb) for the copulative y [and], seen at Quarto 1r.5 in Rey & reyna.34 Another appears in the Quarto’s setting of comprehender (1v.13), which opens with an abbreviatura that consists of an open bow facing left with a right-curved hook at the lower terminal, signaling cum (Latin), but here, com- or con- (Spanish).35The Quarto compresses grandes at 3r.19 and gracias at 4v.3 as shown below.36 The Quarto’s types for signaling extensions opening with p, such as per and pro, are somewhat distinct from those used in the Folio, as the following images suggest.

The Quarto’s Tironian et

The Quarto’s Tironian et

Quarto 1v.13 comprehender

Quarto 1v.13 comprehender

Quarto 2v.11 perdido

Quarto 2v.11 perdido

Quarto 2v.11 procede

Quarto 2v.11 procede  Quarto 3r.19 grandes

Quarto 3r.19 grandes

Quarto 2v.20 proposito

Quarto 2v.20 proposito  Quarto 4v.3 gracias

Quarto 4v.3 gracias

Transcriptions of the Simancas manuscript created by Tomás González and Martín Fernández de Navarrete amount to editions of it because both men freely exercise editorial function in their work, and their results possess value for interpreting the manuscript. Where their work may clarify or oppose a reading of the manuscript or Folio or contribute to the discussion on a difficult or damaged reading, it is noted. Their editing of pauses, sentencing, and paragraphing may assist readers in making sense of the text, sometimes in alternative ways. There is one caveat: Fernández de Navarrete’s note that the manuscript at 1r.2 gives Roman numerals that are difficult to read aright for the number veinte (twenty) — “En el original [el número veinte] está en números romanos muy confusos” [In the original, the number twenty appears in very confusing Roman numbers] (167 n. 2) — is a puzzle.37 The notes to the edition also suggest that Fernández de Navarrete did not merely have González’s transcript printed, as Jane and Ramos have suggested, and as far as I know, there is no compelling cause to think that Fernández de Navarrete was unable to read fifteenth-century script. It is, nevertheless, likely that Fernández de Navarrete was instructed by González in some readings and/or that he had access to González’s transcript. For example, both men arrived at the same understanding on at least one feature of the manuscript, interpreting (in some instances of its appearance) a large sweeping stroke with a curve at either end as the grapheme c. This reading occurs at MS 1v.93 where the probable reading is avan and both men record Cibau, and at MS 2r.123 where both record cala for ala.38

Fernández de Navarrete’s text modernizes some spelling and capitalization to those of his time or taste and adds punctuation, accents, italics (for names of islands), and capitalization (with names of months and islands) that González does not, and González places accents sporadically on third-person singular preterits and prepositions (á, ó) but adds comparatively little punctuation and uses few abbreviations.39 Except where their placement of punctuation and capital letters suggest an organization of a reading, these matters go unremarked, and where their differences are merely orthographic, the notes equate them. Where I read a virgula suspensiva in the manuscript, and González and Fernández de Navarrete place a comma in their texts, their transcriptions are considered essentially representative of the manuscript reading and are not noted.

Because of what appears to be a ready interpretation of areas of indeterminate script and abbreviations, along with the scribal corrections, and an addition to González’s transcript that reflects nothing present on the Simancas manuscript, it seems likely that both men had resort to another manuscript or edition of the Letter with which to compare their readings. Fernández de Navarrete refers in Viages (1825) to his having owned a copy of a Latin edition since 1791 (I 177), and González’s mediation of the manuscript’s omitted line (between 2v.156 and 157) into Spanish implies his use of a supporting version of the Letter, probably one in a language other than Spanish.40 Fernández de Navarrete records González’s certification, as mentioned in chapter six, but, clearly, Fernández de Navarrete consulted the manuscript and exercised editorial license, as is indicated by the results shown in the variorum.

Notes to the text use an explicit format that offers access to experts and non-experts alike. The variorum aims for authentic and transparent editorial work based on the three contemporary Spanish texts, interpreting as accurately as possible the compositors’ intention in setting types and the writer’s intention in shaping graphemes and words. The Latin text of Plannck F and the work of several previous editors and translators provide selective notes where they differ from the Folio reading or clarify it.

Sources used in the variorum should be understood as follows:

Other editorial matters that inform the edition include these:

Notes

1 As is noted in the Preface, this chapter is primarily directed to those new to early print and manuscript materials and unfamiliar with the written vacillations of medieval Romance languages. The need for such an orientation will be apparent to those who present these kinds of materials to students. While critics in these studies experience epiphanies about the material throughout our careers, some mistaken perspectives persist. A recent editorial statement showing one critic’s disconnect with the print culture that formed the Letter describes a printing as “riddled with typographical errors, compounded by senseless letter- and word-spacing and by the lack of punctuation and paragraphing” (citation data suppressed).

2 Read: saber si hauia (Mod. Sp., saber si había) and pierden la foia (Mod. Sp., pierden la hoja). For foia, whose consonantal i is pronounced like the second sound in English azure, see n. 9, below.

3 The Quarto compositor splits mente at line-end without a hyphen in the second instance. The Simancas manuscript scribe tends to split these adverb conversions as well. In Columbus’s time, the grammarian Nebrija, for example, writes tan poco (Mod. Sp. tampoco) and nos otros (Mod. Sp. nosotros), and Nebrija’s works may also give the adjective-to-adverb conversion in two words, as in nueva mente and primera mente. Agglutinations (and separations of syllables and morphemes) and words spelled in variant ways continue to appear through succeeding centuries.

4 The initial x (grapheme) of xalçalamiento reflects phonology in which the Folio, manuscript, and Quarto agree in items such as paxaricos (Folio 1r.30–31; Quarto 1v.16; MS 1r.30), dixe (Folio 1v.38; Quarto 3r.8; MS 1v.89), dexar (Folio 1v.46; Quarto 3r.21; MS 1v.98), and Xio (Folio 2r.37; Quarto 4r.17; MS 2r.139). The grapheme signals the so-called “shushing” (or “hushing”) sibilant. The “shushing” sibilant (akin to the English vocalization that urges quiet) is represented as /š/, /ʃ/, and /S/, a voiceless palatal alveolar fricative. Unlike the durative (lengthened) English vocalization to shush, /š/ is short and tense.

5 The ç is pronounced something like English /t/ + /s/. The result is a voiceless affricate, composed of both a stop /t/ and stage of friction /s/, with the passing of air forcibly through a small aperture. The sound may be represented by /ŝ/, /ts/, or /ts/. The grapheme continued to be used into the seventeenth century in words like alboroço, braço, cabeça, fuerça, and Çaragoça (Zaragoza, Saragossa), examples found in the front material of Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola’s Anales de Aragón (see n.8 below).

The lack of the ç in the Folio is a distinction between the phonological and/or written indications of Columbus autographs and those of the Letter, but the absence may be owing to the simple explanation that no ç types were a part of the case used to set the Letter.

6 The sound is a trilled lateral, then as now.

7 This variation (y/i) for the vowel sound continues over the following centuries. It is attested, for example, in the front material of Argensola’s Anales in words such as cuydados, traygo, seyscientos, and treynta, but with i/I in Ignorancia. Cf. ygnorantes (MS 1v.69) and maravylla (MS 1v.70).

8 The rather free variation (or vacillation) of these graphemes in succeeding centuries suggests that native speakers since the Middle Ages have viewed the phonology associated with these graphemes as virtually identical. In Argensola’s Anales, examples like estava, govierno, and embidia appear. In Spanish today these graphemes signal like phonology — bilabial and occlusive or fricative (“approximate”).

9 This sound is a sibilant consonant in Old Spanish, alveolar and palatal (post-alveolar and pre-palatal, more specifically) in its points of articulation, and voiced and fricative in its manner and effects. This phonology is realized in gente (iente) and cobigan (cobiian) with graphemes g or i, and in fiio, foia, and oio, by i. The sound may be represented phonologically in various sources by symbols /ž/, /Ʒ/, /Z/, or /ż/. The manuscript’s i is written sometimes like a vertical slash with a descender of various extensions, something like the long-i type in printing. This result would eventually become the modern consonant j, differentiating it from the vowel. See n.4, above, for x in trabaxan and axa (alla). The Quarto compositor sets a long-i in initial position for inposibles (4r.27–28) where it is certainly a vowel.

The long-i is also used to close the minims of a Roman numeral, where it is certainly intended as the grapheme i and is used to disambiguate the number from the wording of the text.

10 The letter z in these words is a sibilant consonant beginning with an alveolar voiced stop consonant like English /d/ and finishing with the voiced sibilant /z/ for a voiced affricate that is represented by /ẑ/, /dz/, or /dz/. Argensola’s Anales contains examples such as hazer, haze, and Deziembre. Note that where the letter s is given, as in desir (Folio 2v.40), it probably represents the simple voiced (apico-alveolar fricative) sibilant /z/, like that heard in English “buzz.” The -c- of ficiera is probably understood as the unvoiced version /ts/.

11 See Robert J. Blake’s study of these variants as recorded in Nebrija in 1492 and from other data, including the use of scribal graphemes to represent contrast and printed orthographic variations. Also see Menéndez Pidal’s discussion of the southern tendencies at the period in Orígenes (esp. 231– 232).

12 The first word at 1r.19 of the manuscript may provide an example of the scribal ff that Blake writes is meant to emphasize the labial component of the initial phonology of the word as [f], as opposed to an aspiration, [h], or [ø]. See Blake’s discussion and conclusions (56–59).

13 In the seventeenth century, Argensola uses avre (Ø) along with ha (/h-/) (Mod. Sp., haber) in the dedication to the Diputados de Aragón of his Anales (1630).

14 These graphs are derived from the abbreviatura of Latin scribal culture, from which they came into vernacular scribal cultures and early printing.

15 Plural and/or feminine forms of nuestro are signaled on the same basis. See also the Quarto (1r.2) and MS (1r.1) for nuestro Sennor. The “tilde” used as an abbreviation graph looks like the macron used by pronunciation guides to signal a long vowel, a horizontal bar approximately as long as the letter is wide.

16 See Cappelli (303).

17 The geminate “nn” reflects spelling of the period in which words now written with ñ and pronounced as two sounds (/n/ + /j/) were then spelled with nn, like anno, sennalado, and sennor where those words were written without compression.

18 The ch (with a tilde or horizontal bar over c) may be set here as a ligature type.

19 De Vinne observes in his historical treatment of printing that early printers were blithe about mixing fonts in a single text. He writes that Gutenberg combined rotunda and textura fonts in a single job and that the “types of many printers at Paris and Venice show irregularities of body which seem remarkable to the modern printer” (518) — even in the late 1870s.

20 The paper laid on the press is more or less rough; theoretically, the less valuable the printing, the rougher the paper that might be chosen to do the job. The fibers of the paper and its degree of dampness affect how the paper takes the ink. How a type impresses is also affected by the paper’s raw condition in the area of the impression, by the mix of the ink, and by the job of inking. As paper and ink dry, the effects continue to develop as everything that was wet or damp contracts until the work is dry.

21 Types with an effaced or broken ascender would give a distinct impression from that made by an intact example even though they were cast from the same matrix. This contingency probably does not misdirect identification in this instance.

22 Turns of p, q, d, and b are also theoretically possible (q for b, d for p, and vice versa). It would be relatively easy in distributing types to mis-distribute p and q or d and b, especially if one were inexperienced or impaired or the light were dim.

23 Two additional examples with a decorative center are a p at 1v.39 (porla) and a v at 1v.1 (veyan).

24 Graphemes formed by minims in gothic manuscripts present the same reading problems. A serif off the i minim and the “arrow points” at the top of u, as in the print period, aid in distinguishing those scribal graphemes — where those details are present.

25 Having many turned types in a print run argues against a corrector, but turned types are a common enough occurrence in early printing. See John Johnson’s 1824 caveats to the proofreader (228–229).

26 The spooning of the -ss- indicates a single type since types on separate bodies could not fit together in this way. These ligatures make practical sense for composing in Latin, Catalán, or Spanish.

27 See many examples at 1r: for instance, de at 1r.1, 6, 8, 10, 13, 15, and 22 as ligatures; de appears to be set with two types at 1r.4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

28 In both impressions, the literal ligature may be the source of a lightly inked line between the graphemes; if this is the case, note that the joining is located differently between these examples. A a+l ligature makes sense in Spanish where the combination is frequent as a single word (a + el = al) and in word-initial position, where it often reflects the remains of the Arabic article (al) or opens frequent words like algo and alguno and related forms. Al is also frequent in word-internal and word-final positions, as in qual, mal, saluo, and ualor. See liberales 1v.5, for an example of a probable al ligature (with no physical link visible) based on the proximity of the two types in the setting. See also allend at 1v.16 where the ligature is probably ll and the a-type is separate.

Note also that Gaskell describes “tied letters” composed of “several” letters being cast together as a single type having been produced in the fifteenth century; he distinguishes these from true ligatures (made from a single matrix) though they may be hard to “distinguish” visually (33). Further scrutiny of the Folio and Quarto for “tied letters” may be productive.

29 Haebler mixes these initials in the fonts he assigns to Posa.

30 While a dot or point printed on the base line may look like a modern period, that is not its grammatical or reading role in the Folio. In 1493, periodus referred to a grammatical structure, and the punctus, represented by the familiar point (.) or by a tiny plus (+) or rhombus, was the basic naming and graphic unit of punctuation and the most common component of punctuation signs. It might be used to point to grammatical boundaries or to signal reading pauses.

31 This may be an instance where the compositor tries to correct a verb (ha > han), perceiving that its subject is los indios. I take the subject to be San Salvador.

32 The function is observed erratically elsewhere as well. See 1v.43, 1v.45, for example, where editorially imposed punct s appear bracketed around Roman numerals.

s appear bracketed around Roman numerals.

33 An early Catalán-language example showing end-line hyphens is a Regiment dels princeps attributed to Spindeler in Barcelona in 1480 (Haebler BI No. 154; Odriozola 128 No. 31, pl. XII); this Regiment’s gothic type is very similar to that of the Folio, both in its lower-case types and initials. See several examples of post-1501 printings by Cromberger in Norton (Printing) where divisions are sometimes marked by hyphens and sometimes not (Pl. I, II); the gothic types in these plates are strikingly similar to those of the Folio.

34 The edition does not show the Tironian et as a variant, and the notes to the edition render it as & where it appears in text recorded from the Quarto showing other variants.

35 See Cappelli for variants of this figure (39).

36 This abbreviatura may not be clear on some reproductions. The type may be a ligature as gr (with tilde).

37 The comment suggests that Fernández de Navarrete was not looking at González’s transcript nor at the manuscript reflected here in facsimile because in both texts, “twenty” is expressed verbally and easily read. See MS 1v.85 with n. 160 and MS 2v.161 with n. 321 in the following chapter. At 1v.85, for example, a superscript stroke, similar to a u or a c opening upward set above the second figure might be taken as representing c (cien [100]) but does not seem logical; as cum (con [with]), this stroke would make more sense set above the first figure. González writes visto 60 y Ochenta (Sanz 513 ¶ 3). Fernández d--e Navarrete gives visto sesenta y ochenta (171). At 2v.161, following his recording setenta y ocho, Fernández de Navarrete sets a footnote: “en el original […] está escrito en números romanos y enmendados” and gives the basis of his calculations (I 174–175 n. 3). MS 2v.162 is much effaced. See also the stricken text in the year given at MS 2v.156 (shown as 2v.116 in error, following 155). These readings might be described as “números romanos muy confusos,” and Fernández de Navarrete may have conflated the instance at 1r.2 with another instance of numbers on the manuscript as he was writing notes to his text — easily done. This “problem” remains a doubt, but for the rationales given, it does not appear to be a fatal disconnect in a comparative reading using Fernández de Navarrete’s transcript. It is also interesting, but perhaps merely a slip, that Fernández de Navarrete refers to the manuscript he is editing as “el original de Colon [sic]” (175 n. 1).

38 This stroke may be a reading signal or a mark of punctuation — or it may be, occasionally or in every instance, merely a scribal tic. The matter could use a systematic study.

Ramos’s readings of the Simancas manuscript (1986 Primera), performed by an able assistant, are not useful in this context because they are apparently founded on the “facsimile” featured in his edition, apparently a tracing of the original. The manuscript is presented here in facsimile with the kind permission of the Spanish Ministro de Educación, Cultura y Deporte and the generous assistance of the librarians at the Archivo General de Simancas.

39 Another distinction is that González imposes paragraph divisions, but Fernández de Navarrete blocks the whole text, essentially as it appears in the manuscript. Where González makes a new paragraph, Fernández de Navarrete makes only a new sentence. Both men modernize I to J, or else they read the long-i as J (or j), and both leave some agglutinations (ala, della, ques) intact, common practice at the time of their work.

40 MS 2v.156 is numbered “116” — a slip of the pen.

41 If Fernández de Navarrete had available to him the original of the document reproduced in Sanz, he does not appear merely to follow it without demur. He does not, for example, adopt the missing line that González supplies, an editorial emendation that strongly suggests that González must have been relying on some non-Spanish edition, for in no other way could he have supplied his mediated version of the line that appears in somewhat different wording in the Folio (2v.6) and Quarto (4v.11).

42 The notes are busy with parenthetical citations of prioritized texts. While both transcripts are published, they are considerably less accessible than others cited. Readers who wish to compare the Simancas manuscript to one of its transcripts can do so by following the MS lines as given through the transcription and/or by setting some signal phrases as benchmarks for cross-referencing.

43 An example of a modernization is Fernández de Navarrete’s transcription of habréis from the Simancas manuscript’s avreys (1r.1). Modernizing spellings and adding diacriticals like the accent in habréis were standard practices in text editing from the nineteenth century into the last quarter of the twentieth century and do not reflect Fernández de Navarrete’s readings of the manuscript in the 1820s per se.

Varela’s edition divides the Letter into paragraphs and adds or standardizes punctuation, accents, apostrophes, and capitalization, modernizes spelling according to accepted standards, and uses modern conventions of word separation in the text. The result is that Varela’s text modernizes quando to cuando and qual to cual; revises spellings with u to v or with v to u (vmana > umana, Mod. Sp. humana) as necessary according to whether a vowel or consonant is represented, maintaining v, therefore, in imperfect forms (demandava); modernizes the copulative i to y; mediates i to j to conform with modern spellings; leaves consonantal i in words that now use g as in iente (gente [people]); and records the Letter’s ñ as modern ñ. For these reasons, her text sustains many older spellings in addition to those already cited (nonbre, fartos, io), alters a few (conversasion > conversación), expands compressions according to modern spellings, usually adds accents (fazía), and capitalizes or suppresses capitals according to present-day sensibilities (magestat > Magestat; Isla > isla). Note Varela’s apparatus (86).