When someone who delights in annoying and vexing peace-loving folk receives at last a right good beating, it is certainly an ill, but everyone approves of it and considers it as good in itself, even if nothing further results from it.

—IMMANUEL KANT1

Every decent man will kvell when that sadist goes to jail.

—LEO ROSTEN2

Being an old farm boy myself, chickens coming home to roost never did make me sad; they always made me glad.

—MALCOLM X3

It is hard to imagine the film industry without the revenge plot. There are inexhaustible variations on the theme, but the basic pattern is simple, predictable—and preferred by viewers. The villain treats the hero badly, and the arc of the story completes itself with the hero taking satisfying revenge. No one is more pleased when justice is served than the eager audience. The villain gets no sympathy. We cheer the outcome. It is highly pleasing to see bad people get what they deserve.

The regular merging in films of justice-inspired revenge with its resulting pleasure suggests a natural link between justice and schadenfreude.4 No manner of bloody end can cause us to blanch. I make this claim confidently because of a two-year stint working as an assistant manager at a movie theater during the late 1970s. The catbird seat in the projectionist booth was a good place for observing audience behavior. We showed many films that made audiences cheer when the villain got what was coming to him, but the one I remember best was the Brian De Palma film, The Fury. The villain in this film is an intelligence operative, Ben Childress, played by John Cassavetes, who pitilessly experiments with the lives of two teenagers who happen to have telekinetic powers that could be useful for intelligence purposes. When his actions lead to the death of one of the teens, the other teen turns her telekinetic powers on Childress. Driven by her anger and hatred, she levitates him a few feet off the ground and spins him around with increasing speed until he explodes. The theater audiences were untroubled by the grotesque scene. Some whooped and hollered. They hated this man, played so effectively by Cassavetes. Not only did they want him dead, but they also wanted him minced and pulverized. He deserved it. A ghastly end—but pleasing even so.5

There seems little question that seeing a just misfortune befalling another causes us to feel pleased, with schadenfreude being part of the feeling. Philosopher John Portmann, who has written more on schadenfreude than any other scholar, argues it is an emotional corollary of justice.6 It follows seamlessly from a sense that the misfortune is deserved. And experiments by social psychologists Norman Feather, Wilco van Dijk, and others confirm what one would expect: participants in experiments report more schadenfreude over deserved than undeserved misfortunes.7

Typically, we use shared standards to resolve whether a misfortune is deserved. For example, we think people who are responsible for their misfortunes also deserve their suffering, and schadenfreude is a common response.8 Brazen swindler Bernie Madoff will go down in history for his Ponzi scheme, breathtaking in scale. Investors appeared to earn returns that were actually generated by later investors. Many high-profile individuals, charities, and nonprofit institutions lost staggering amounts of money, with the tally of the crime reaching $60 billion.9 In June 2009, when Madoff received his sentence of 150 years, cheers and applause filled the courtroom packed with many of his victims.10 Even Madoff appeared to finally grasp the enormity of his wrongdoing. After receiving this maximum sentence, he turned to address his victims: “I live in a tormented state knowing the pain and suffering I have created.”11

Another shared standard for deservingness, often related to responsibility, has to do with balance and fit. We believe that bad people deserve a bad fate, just as good people deserve a good fate. We believe that extremely bad behavior deserves extreme punishment, just as extremely good behavior deserves great reward. And so villains such as the character played by Cassavetes in The Fury deserve their demise because of their villainous natures and wicked behaviors. They receive their “just desserts.” This is pleasing to observe because it agrees with our ideas of how fate should play out. Part of this pleasure is aesthetic. The righting of the balance achieved when bad behavior leads to a bad outcome produces a kind of poetic justice.12

Reactions to Madoff’s punishment fit this standard as well. He did indeed create extreme suffering and betrayed the trust of many in the process—shamelessly, it seemed—until he was caught.13 His victims, when given the chance to describe their personal losses before the sentencing, pulled no punches. One victim, Michael Schwartz, whose family used their now lost savings to care for a mentally disabled brother, said, “I only hope that his prison sentence is long enough so that his jail cell will become his coffin.”14 The judge concurred, labeling Madoff’s crimes as “extraordinarily evil,” which is why for each of the crimes to which Madoff confessed, the maximum sentence was imposed. “It felt good,” said Dominic Ambrosino, one of Madoff’s many victims, who was outside the courthouse in the crowd when the news of the verdict spread.15

One of the most unfortunate tales from the Madoff scandal involved Nobel Peace Prize recipient and Auschwitz survivor Elie Wiesel. Because of Madoff’s scheme, Wiesel lost $15 million of funds for his Foundation for Humanity. This was virtually all of the Foundation’s endowment. Wiesel was in no forgiving mood. “Psychopath—it’s too nice a word for him,”16 Wiesel said and then went further to recommend a five-year period in a prison cell containing a screen depicting the faces of each of Madoff’s victims—presented morning, noon, and night.17

Nor was there a trace of sympathy for Madoff when he landed in prison. In fact, some even expressed disappointment that he was sentenced only to a minimum security facility populated largely by other white-collar criminals. The maximum punishment allowed by law seemed hardly enough. Most people took what pleasure they could from the event, nonetheless. This was especially evident on the internet, where most comments were exultant and often crude. A post on one site contained a photo of Madoff’s prison bed and included comments such as the following:18

Isn’t there a bed of nails we could put in there?

There’ll be a lot of outrage when people see that he gets a pillow for his head.

I hope those beds are filled with bedbugs.

Madoff’s swindle was epoch-making. He betrayed the trust of friends, charities, and, evidently, even his family. He so deserved his punishment by any standard one could point to that no one seemed sorry for him. Rather, just about everyone was openly happy to see this money man with the counterfeit Midas touch reduced to prison inmate.

Schadenfreude clearly thrives when justice is served. As a basis for schadenfreude, deservingness has the advantage of seeming to be unrelated to self-interest because the standards for determining justice appear objective rather than personal and thus potentially biased.19 It is less an “outlaw” emotion, less a shameful feeling. John Portmann describes the example of the influential Roman Catholic theologian Bernard Haring, who declared that schadenfreude is an evil, sinful emotion to feel. And yet Haring qualifies this characterization by noting,

Schadenfreude is evil, it is a terrible sin—unless you feel it when the lawful enemies of God are brought low, and then it’s a virtue. Why? Because you can then go to the lawful enemies of God and you can say “see, God is making you suffer because you’re on a bad path.”20

I am unaware of any examples in the Gospels of Christ approving of schadenfreude. However, Haring’s sentiments echo those of other religious thinkers, such as 13th-century Catholic priest St. Thomas Aquinas21 and 18th-century Christian preacher Jonathan Edwards. The title of one of Edwards’s sermons was “Why the Suffering of the Wicked will not be Cause of Grief to the Righteous, but the Contrary.”22 Evil schadenfreude may be, but not when the lawful enemies of God get what they deserve. If sanctified justice is served, then schadenfreude is—well—justified.

Some types of deservingness produce an especially satisfying schadenfreude. I suspect that few things can top the fall of the hypocrite. The archetype of this general category is Jimmy Swaggart, who stands out among a congested group of unforgettable cases. Swaggart, a talented, charismatic entertainer, helped create a particular brand of Christian proselytizing: the TV evangelist. His program, The Jimmy Swaggart Telecast, at its peak, was broadcast on hundreds of stations around the globe. Swaggart continues to this day to entertain and attract a large following. He is a remarkable person, a self-made American original. However, he got himself in trouble in the late 1980s. Swaggart not only preached about the consequences of sin, but he also went about exposing the sins of others. Most notably, he accused another well-known evangelist, Jim Bakker, of sexual misconduct. But Swaggart soon lost his high moral footing. A church member, whom Swaggart also accused of sexual misbehavior, hired a private detective to monitor Swaggart’s activities. The detective produced photographs showing Swaggart’s regular visits to a prostitute. When the leadership of his church, the Assemblies of God, learned of this behavior, they suspended him for three months. In a public confession—a now iconic event in popular culture—Swaggart came before his congregation and television audience to admit his sin and ask for forgiveness.23

For many, the image of Swaggart, his face twisted in pain and tears streaming down his cheeks was, and still is, a source of unabashed hilarity. His behavior was full-strength hypocrisy, and his humiliation seemed wholly deserved. Indeed, most media accounts and letters to major papers focused on the hypocrisy of Swaggart’s behavior and heaped on the disgust, ridicule, and glee.24 Making matters worse for Swaggart, and further preserving the likelihood that his confession would persist in cultural memory, was that he returned to the pulpit far from entirely repentant. Thus, the Assemblies of God defrocked him. A few years later, he was caught with yet another prostitute. He didn’t bother with contrition this time. He told his congregation, “The Lord told me it’s flat none of your business.”25 Confession is one thing; repentance is quite another.26

When it comes to hypocrisy and its gratifying exposure, preachers stand out. Many in this line of work seem so quick to point out others’ moral failings despite being vulnerable to moral lapses themselves.27 In the Introduction, I noted the case of George Rekers. His anti-gay initiatives were undone when he was caught hiring a young man from Rentboy.com to accompany him on a trip to Europe. What took Rekers’s hypocrisy to its spectacular level—and what made the schadenfreude seem so deserved—was that he went out of his way to further policies that harmed gay people for their homosexual behavior—for more than three decades. As much as one might feel sorry for Rekers as he combated the white-hot media attention that he received, his prior punishing ways put him at a disadvantage for deflecting schadenfreude. Syndicated columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr. wrote, “as perversely entertaining as it is to watch someone work out his private psychodrama in the public space … there is a moral crime here.”28 Rekers condemned and punished people for behaviors he evidently engaged in himself.

Another well-publicized example is Reverend Ted Haggard, who resigned from his mega-church in Colorado Springs after admitting to having homosexual relations with a professional masseur named Mike Jones.29 Haggard’s behavior was patently hypocritical because he had condemned homosexuality so frequently and vigorously. In a documentary, Jesus Camp, he proclaimed with conviction that “we don’t have to debate about what we should think about homosexual activity. It’s written in the Bible.”30 Among his authored books, one had the title From This Day Forward: Making Your Vows Last a Lifetime.31 Jones, for his part, wanted to reveal their relationship because he learned that Haggard (who went by the name of “Art” when he visited Jones) supported a Colorado ballot amendment that would ban same-sex marriage in that state. When Jones realized how much Haggard’s influence might lead to passage of the amendment, he grew increasingly angry:

I remember screaming at his picture on the computer. “You son of a bitch! How dare you!” Art and every straight-acting couple in America could get married and divorced as many times as they liked, yet two men or two women cannot get married even once, much less enjoy the legal benefit of marriage. … I was becoming angrier by the minute.32 … You goddamn hypocrite!33

Haggard at first denied the allegations of sexual contact,34 but evidence against this denial mounted quickly, as did the cascading waves of schadenfreude. His behavior was satirized in various forms from late-night comedy to a book-length treatment on sex scandals (The Brotherhood of the Disappearing Pants: A Field Guide to Conservative Sex Scandals).35 One response from a pleased blogger summed up the tenor of most reactions: “I love the smell of hypocrisy in the morning.”36

As for Mike Jones, he claimed to get no pleasure out of exposing Haggard’s hypocrisy. Friends even commented that he should have been more lively when interviewed about his relationship with Haggard. But Jones wrote that he “was not happy about anything that had happened.”37 Perhaps he worried that being “lighthearted” would make his motives suspect. In any event, he recognized the glaring inconsistency between Haggard’s public denouncements and his private behavior. Wrote Jones, “You must not speak out against something that you do in secret. You must practice what you preach. Let us not forget that the ultimate word in this story is hypocrisy.”38

Preachers are easy targets. Their job requires that they encourage moral behavior in others—even though they are surely flawed themselves, just like their congregations. And, just like the rest of us, for that matter. It is an occupational hazard made worse by a greater need to keep up appearances and maintain at least a higher standing of moral behavior than those around them. But their professional activities may expose them to many powerful temptations as they counsel their flock. Sometimes, to quote Oscar Wilde, “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”39 Swaggart and Haggard both have redeeming qualities, obscured by the exposure of their hypocrisy. I, for one, enjoy Swaggart’s preaching and his gospel singing. I am quite taken by the life story of someone who is, as one biographer of Swaggart, Ann Rowe Seaman, put it, so “full of sauce”40 and so uniquely “poor and gifted and determined.”41 I admire how Haggard and his wife have handled life since his fall from grace. Haggard has been forgiving in his comments about Rekers (e.g., “we are all sinners”),42 but even he noted that his own actions were not as hypocritical as Rekers’s.43 As I stressed in Chapters 1 and 2, the social science evidence makes clear the self-esteem benefits of seeing oneself as superior to others. When is it not open season for a downward comparison?

Take someone like Bill Bennett, the well-known and accomplished conservative thinker and author of books such as Moral Compass: Stories for a Life’s Journey and The Book of Virtues. Bennett has a reputation in some circles for wagging the moral finger at others for their misbehavior.44 In 2003, a story circulated that he had been gambling at casinos for years, losing as much as $8 million. Bennett had his defenders.45 His books on virtues are effective tools for instilling moral values in kids. But many writers seized on this story, notably Michael Kinsley of Slate Magazine, who awarded Bennett a “Pulitzer Prize for schadenfreude.” Kinsley guessed that many sinners had long fantasized that Bennett was a secret member of their club. And so he wrote that “[a]s the joyous word spread, … cynics everywhere thought, for just a moment: Maybe there is a God after all.”46

Preachers and others who make a living telling others how to live get top billing in the roll call of fallen hypocrites. But hypocrisy plays no real favorites. Politicians often feel the need to both aggrandize themselves and criticize their opponents in order to get elected. Thus, in scandals and the media attention that surrounds them, they come in at least a close second. Like preachers, who need to impress congregants, politicians have to position themselves to voters and constituents as beyond reproach.

Yes, witnessing the suffering of hypocrites is felicitous fun. What is behind this distinctive pleasure? Hypocritical behavior reveals a breakdown between words and deeds, usually having to do with moral behavior. Hypocrites claim virtue but practice sin. According to one gospel account, hypocrisy among the religious leaders even made Jesus angry:

Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye make clean the outside of the cup and of the platter, but within they are full of extortion and excess. … Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye are like unto whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men’s bones, and of all uncleanness.47

Throughout history and across cultures, people find inconsistent behavior unappealing. “The person whose beliefs, words, and deeds don’t match is seen as confused, two-faced, even mentally ill,” notes social psychologist Robert Cialdini in his book Influence: Science and Practice, also referenced in Chapter 4.48 Cialdini speculates that being inconsistent may even be worse than being wrong. It smacks of deception and is a violation of trust.

It is more than contempt from the sidelines that leads us to condemn hypocrites. Hypocrites often set themselves up as morally superior, forcing imperfect people around them to ponder their relative moral inferiority. Thus, even before their hypocritical behavior comes to light, hypocrites can be an irritating, disagreeable presence. Their “holier than thou” manner is annoying.49 For example, Stanford University social psychologist Benoit Monin has found that the presence of a vegetarian can make an omnivore self-conscious. He showed that meat-eaters can feel morally inferior around vegetarians, who they anticipate will show them moral reproach.50 Vegetarians need not say a word; their very existence, from a meat-eater’s point of view, is a moral irritant. And so imagine the pleasure felt by a meat-eater when catching an avowed vegetarian snacking on a rack of ribs. Discovery of this deceptive, hypocritical behavior is a buoyant event. We are not as inferior as we were led to believe; now, we can assume the contrasting position of moral superiority. Naturally, this turnaround feels good.

There is another reason why misfortunes befalling hypocrites should be so satisfying. Often, these misfortunes amount to their being caught doing the very thing that they point the finger at others for doing. The precise matching of their moral rebukes and the behavior that lands them in trouble heightens the suitable feel of their downfall. Such reversals have extra special aesthetic appeal.51 Justice rises up to meet poetry. This helps make the exposure of hypocrisy feel like such a satisfying tale.

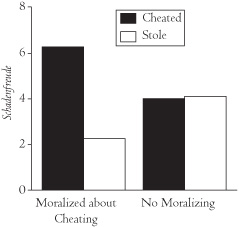

I collaborated on an experiment with social psychologist Caitlin Powell in which we showed how pleasing it is to see hypocrites get caught for the precise thing they have criticized others for doing.52 Our undergraduate participants read what appeared to be an article containing an interview with a fellow student. Half the time, the student interviewed mentioned being an avid member of a campus organization aimed at curtailing as well as punishing plagiarism. The student said in the interview, “It really gets me mad when I see people cheating or plagiarizing. That’s just lazy. Our actions have helped in the punishment of three recent cases of cheating.” For other participants, the student was simply mentioned as being a member of a university club. In a second, follow-up article, the same student was charged with one of two possible moral lapses: he had been caught and suspended either for plagiarizing or for stealing. We also gave our participants questionnaires after each article to gauge what they thought and felt about the student, his misconduct, and his subsequent punishment. As we expected, the student was seen as more hypocritical when he had been a member of the organization focused on academic misconduct and was subsequently caught plagiarizing compared to when he had just been a member of the club. In this case, our participants also thought his punishment more deserved and more pleasing.

What was more interesting was a comparison of reactions to the two kinds of misbehaviors, depending on whether the student had been a member of the organization focused on academic misconduct or the club. When the student had been a member of the club, his misfortune was viewed as equally deserved and experienced as equally pleasing, regardless of whether he was caught stealing or plagiarizing. After all, both behaviors were morally wrong. How about when the student had been a member of the organization that aimed to combat plagiarism? (See Figure 5.1.) Participants now felt much more pleased when the student got caught for the precise behavior he criticized others for doing, that is, when he was caught plagiarizing. And this is the important part: they felt this way even though the misbehaviors were equally immoral. Why? Knowledge that the student had criticized others for plagiarizing transformed how participants felt about the student getting caught. The matching of misconduct and prior statements enhanced the perception of hypocrisy and the deservingness of the misfortune.

Figure 5.1. The effect of prior moralizing about cheating on the intensity of schadenfreude. Prior moralizing about cheating resulted in markedly greater schadenfreude in response to a person caught cheating compared to stealing.

There is little doubt about it. Deserved misfortunes are a joy to witness, whether due to hypocrisy, as was the case in this experiment, or to other factors that make misfortunes seem deserved. We can understand why John Portmann, after his wide-ranging scholarly examination of the nature of schadenfreude, concluded that deservingness is the main explanation for why we can take pleasure in the misfortunes of others. Indeed, much more can be said about this frequent cause of schadenfreude, and the next chapter will take up some of these points.