The Founding Fathers left the stage as the Elite Era drew to a close. Charles Carroll, the final survivor among the 56 men who had affixed their signatures to the Declaration of Independence, died in 1832. James Madison, the last living signer of the Constitution, passed away in 1836.

It was just as well. The Founders would have been horrified by the election of 1840. The rise of the common man prompted a change in political tactics, with parades, barbecues, songs, and slogans becoming the staples of a successful campaign. The Whigs taunted the incumbent Democrat, Martin Van Buren, in rhyme—“Van, Van, is a used-up man”—while rolling 10-foot-high Whig balls in a seemingly endless series of torchlight parades. These spectacles dismayed the nation’s elites, but one observer, Michael Chevalier, considered them “the episodes of a wondrous epic which will bequeath a lasting memory to posterity, that of the coming of democracy.”1

The impact was immediate and dramatic. Voter turnout, which had not reached 58 percent in any prior election, soared to 80 percent in 1840. The ratio of popular votes to population, which had previously been less than 100,000 votes per million, shot up to 141,300 per million in the same year. General elections would never be the same.

Nor would the nomination process. The Whigs needed five ballots to settle on William Henry Harrison as Van Buren’s opponent in 1840, the first time a convention had been forced beyond a single roll call. The Democrats extended the record to nine ballots in 1844, the Whigs reclaimed it with 53 roll calls in 1852, and the Democrats upped the ante to 59 in 1860. Half of all conventions between 1840 and 1908—18 out of 36—were multiballot affairs. Party gatherings have been much calmer since 1912, with 43 nominations coming on the first roll call, only 9 requiring two ballots or more.

But high levels of voter participation and contentious battles between candidates weren’t the only defining characteristics of the 18 elections that bridged the administrations of William Henry Harrison and William Howard Taft. The Volatile Era draws its name from the frequent arrival of new tenants at the White House. The era encompassed 32 percent of all 57 presidential elections, yet it was governed by 42 percent of the 43 men who have served as commander in chief.

Each of the six elections from 1840 to 1860 produced different winners, as did all seven contests from 1872 to 1896. Presidents who won two straight terms were rarities, with only Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, and William McKinley securing consecutive reelections. Grover Cleveland also won twice, though in keeping with the Volatile Era’s theme, he sandwiched a defeat in the middle. The contrast with the other three periods is striking:

| Era | Elections | Consecutive reelections | Share |

| Elite Era (1789–1836) | 13 | 5 | 38% |

| Volatile Era (1840–1908) | 18 | 3 | 17% |

| Progressive Era (1912–1956) | 12 | 5 | 42% |

| Modern Era (1960–2012) | 14 | 5 | 36% |

The spirit of volatility also extended to political parties. The Democratic Party survived the era, but the Whigs were supplanted by the Republican Party in the 1850s. Other movements briefly bubbled to the surface, then disappeared just as quickly—the Southern Democrats, the Liberal Republicans, the Populists.

The era’s ultimate displacement, of course, was the Civil War, which would color the nation’s politics for half a century. The Republican nominee in 1876, Rutherford Hayes, was still haunted by the war. “The true issue in the minds of the masses,” he insisted, “is simply, shall the late rebels have the government?”2 McKinley, who carried the Republican standard in 1896 and 1900, always preferred to be called “Major.” That had been his brevet rank with the Ohio Volunteers more than three decades earlier.

The Republicans, the party that had opposed the rebellion, dominated the Volatile Era by winning 11 presidential elections. The Democrats took five—though only two after Appomattox—and the Whigs won the remaining two. The following is a rundown of the era’s major-party nominees. (If you’re wondering about the abbreviations here or in the charts on the pages that follow, see the explanation at the beginning of Chapter 2.)

| Election | Candidate | PV% | EV | CS |

| 1840 | William Henry Harrison (W) | 52.88% | 234 | 87.90 |

| Martin Van Buren (D) | 46.81% | 60 | 65.49 | |

| 1844 | James Polk (D) | 49.54% | 170 | 81.33 |

| Henry Clay (W) | 48.08% | 105 | 71.05 | |

| 1848 | Zachary Taylor (W) | 47.28% | 163 | 78.93 |

| Lewis Cass (D) | 42.49% | 127 | 71.66 | |

| 1852 | Franklin Pierce (D) | 50.84% | 254 | 89.52 |

| Winfield Scott (W) | 43.87% | 42 | 63.01 | |

| 1856 | James Buchanan (D) | 45.28% | 174 | 79.35 |

| John Fremont (R) | 33.11% | 114 | 68.16 | |

| 1860 | Abraham Lincoln (R) | 39.82% | 180 | 78.38 |

| John Breckinridge (SD) | 18.10% | 72 | 60.76 | |

| Stephen Douglas (D) | 29.46% | 12 | 57.06 | |

| 1864 | Abraham Lincoln (R) | 55.09% | 212 | 92.17 |

| George McClellan (D) | 44.89% | 21 | 61.66 | |

| 1868 | Ulysses Grant (R) | 52.66% | 214 | 85.63 |

| Horatio Seymour (D) | 47.34% | 80 | 67.61 | |

| 1872 | Ulysses Grant (R) | 55.61% | 286 | 89.28 |

| Horace Greeley (D-LR) | 43.82% | — | 58.76 | |

| 1876 | Rutherford Hayes (R) | 47.95% | 185 | 77.12 |

| Samuel Tilden (D) | 50.98% | 184 | 75.14 | |

| 1880 | James Garfield (R) | 48.30% | 214 | 79.77 |

| Winfield Hancock (D) | 48.21% | 155 | 72.24 | |

| 1884 | Grover Cleveland (D) | 48.87% | 219 | 78.78 |

| James Blaine (R) | 48.25% | 182 | 73.26 | |

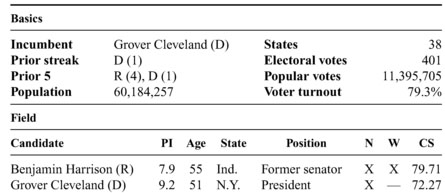

| 1888 | Benjamin Harrison (R) | 47.82% | 233 | 79.71 |

| Grover Cleveland (D) | 48.61% | 168 | 72.27 | |

| 1892 | Grover Cleveland (D) | 46.01% | 277 | 80.73 |

| Benjamin Harrison (R) | 42.97% | 145 | 68.40 | |

| 1896 | William McKinley (R) | 51.10% | 271 | 81.24 |

| William Jennings Bryan (D-POP) | 45.82% | 176 | 70.98 | |

| 1900 | William McKinley (R) | 51.67% | 292 | 82.89 |

| William Jennings Bryan (D) | 45.50% | 155 | 69.53 | |

| 1904 | Theodore Roosevelt (R) | 56.41% | 336 | 85.72 |

| Alton Parker (D) | 37.60% | 140 | 66.33 | |

| 1908 | William Howard Taft (R) | 51.58% | 321 | 83.31 |

| William Jennings Bryan (D) | 43.05% | 162 | 68.65 | |

The presidents of the Volatile Era were more youthful and geographically diverse than their Elite Era predecessors. The median age for the 18 winners from 1840 to 1908 was 52.7, precisely eight years younger than the 1789–1836 median of 60.7. Six victors in the Volatile Era had not yet reached their 50th birthdays. Ulysses Grant and Theodore Roosevelt were the babies of the group, winning their first elections at the age of 46.

Virginia served as the fount of leadership in the early years of the republic. Eight of the first nine elections in the Elite Era were carried by residents of that state. John Adams, the only non-Virginian to win during that span, groaned that his son, John Quincy, would never become president “till all Virginians shall be extinct.”3

But the Volatile Era brought a swift change of geographic fortune. Nobody from Virginia secured a major-party nomination, let alone the presidency. Thirteen of the 18 winners came from west of the Appalachians, including four from Illinois (Lincoln and Grant twice apiece) and six from Ohio. “Out of the lair of the wolf came the founders of old Rome,” the Atlantic Monthly declared in 1899, “and out of the Ohio forest came rulers for young America.”4 The Midwest had truly become the new cradle of the presidency.

You’ll encounter several references to flipping in the remaining chapters of this book. The term didn’t arise earlier because a flip is a scenario based on state-by-state popular-vote counts, and we just began dealing with popular votes a few pages back.

The goal of flipping is to alter the general-election results in key states, thereby reversing the national outcome in the Electoral College. The size of the flip in any given state is the whole number that is immediately larger than one-half of the popular-vote margin between the winner and the runner-up. If the gap is 200 votes, for instance, the flip would be 101.

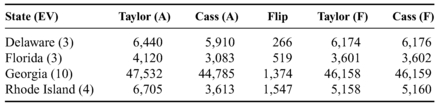

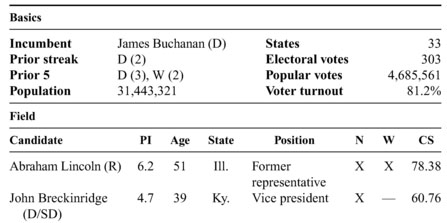

Let’s consider a concrete example, the presidential election of 1848. The Whigs nominated Zachary Taylor, a Mexican War hero who was so uninterested in politics that he had never voted for president. Congress had authorized a medal for Taylor two years earlier in gratitude for his successes against the Mexican army. The only problem was that nobody knew what he looked like. An artist was dispatched to his camp in Mexico to sketch a portrait.5

Pitted against this faceless candidate was Democratic nominee Lewis Cass, who had held several major political positions—governor of Michigan, U.S. senator, minister to France, and secretary of war. It was difficult to imagine such a seasoned professional losing to a neophyte, but Cass was not without liabilities. Many of his fellow Democrats were convinced that he lacked firm principles, especially on the touchy subject of slavery. “And he who still for Cass can be,” these disbelievers chanted, “he is a Cass without the C.”6

Taylor, of course, emerged as the winner, a triumph of obscurity over experience. The results seemed decisive in both popular votes (47.28% to 42.49%) and electoral votes (163 to 127), yet the election easily could have gone the other way. If just 6,773 votes had been flipped from Taylor to Cass in Pennsylvania, the latter candidate would have become the new president. Here’s the math, with (A) denoting the actual totals and (F) the hypothetical totals after the flip occurred:

This simple adjustment in a single state would have changed the electoral-vote count to 153 for Cass and 137 for Taylor. But there was another way, involving an even smaller number of votes, to achieve a similar outcome. A flip of just 3,706 popular votes in four states also would have tipped the election to the Democrats:

The margin in the Electoral College—Cass 147, Taylor 143—would have been tighter than with the Pennsylvania flip, but the impact would have been the same. Lewis Cass would have been elected president.

This book expresses flips in three ways: the number of states involved (four in the previous chart), the number of popular votes flipped (3,706), and the percentage of all popular votes involved. Nearly 2.9 million men voted in 1848, which means the outcome would have been altered if just 0.1287 percent of all voters had changed their minds:

3,706 / 2,879,184 = 0.1287%

Three elections in American history—1876, 1884, and 2000—were so tight that a flip of fewer than 1,000 votes would have reversed their results. The 2000 race was the closest in percentage terms, 0.0003 percent. You can find several lists of smallest and biggest flips in Chapter 6.

ELECTION NO. 14: 1840

A total of 131.3 million Americans cast ballots in 2008, the largest number of voters in any presidential election ever. The turnout rate climbed to 57.1 percent that year, the strongest mark in four decades. Political experts were greatly encouraged. “We seem to have restored the levels of civic engagement that we had in the 1950s and 1960s,” said Michael McDonald, an authority on voter participation.7

It proved to be a premature assessment. Turnout plummeted to 54.9 percent in 2012, forcing analysts to concede that 2008’s numbers had been inflated by excitement over Barack Obama’s campaign. America’s first black president was unable to weave the same magic the second time around. The percentage of adults who voted in 2012 was actually lower than the figure for 2004, George W. Bush’s reelection year.

But imagine a different scenario. What if there had been an incredible burst of passion and zeal in 2012? What if the turnout rate had soared to 80 percent, boosting the number of voters to an incomprehensibly high level? Impossible, you say. No way it could have happened.

It’s exactly what occurred in 1840.

The Whigs entered the year with the same problem that had plagued their previous campaign. They still sought a way to satisfy the various elements of their weird coalition of abolitionists, slaveholders, and other politically opposed groups. Running a team of regional candidates in 1836 had not been the answer. Different tactics would be needed against the Democratic incumbent, Martin Van Buren, in 1840.

The strategy the Whigs finally decided upon—deliberate obscurity— remains a favorite of many political consultants today. The idea was to nominate somebody whose philosophy was unknown, and then to promote him with a cosmetic campaign. William Henry Harrison seemed the ideal choice. He had been the most successful member of the Whig team in 1836—carrying seven states—yet had said virtually nothing of substance. Most Americans knew only that Harrison had led his troops to victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe almost 30 years earlier. Critics mocked him as “General Mum,” referring less to his military background than to his political reticence.

The Whigs had never shown much interest in the common man—business titans and plantation owners were more their speed—but they projected a radically different image in 1840. Harrison, who lived on an enormous estate in Ohio, was portrayed as a man of the people. Alcohol and parades became the cornerstones of the Whig campaign, while discussions of policy were steadfastly avoided. “Men whose brains are muddled at the Tippecanoe Clubs with drinking hard cider can neither reason or understand reason,” complained a Democratic newspaper. “But they can shout, and they feel a strong propensity to lift up their voices.”8

The strategy worked to perfection. Voter turnout skyrocketed from 57.8 percent in 1836 (virtually the same rate as in 2008) to 80.2 percent in 1840. The upswing was particularly strong in the 15 states that Van Buren had carried four years earlier. Farmers and workingmen who had paid no heed to the 1836 campaign were remarkably eager to vote in 1840. An additional 606,000 ballots were cast in the old Van Buren states, a massive increase of 73 percent:

| Type of state | States | 1836 PV | 1840 PV | Change |

| Carried by Van Buren in 1836 | 15 | 828,060 | 1,434,549 | 73.24% |

| Carried by Whigs in 1836 | 11 | 675,474 | 977,259 | 44.68% |

Van Buren reigned as New York’s undisputed political boss, yet he was submerged by a flood of 136,000 new voters in his home state, two-thirds of whom supported Harrison. The trend was even more lopsided in North Carolina, where three-quarters of the additional votes went Harrison’s way. Both of these states—and seven others that had backed Van Buren the first time—switched to the Whigs in the rematch. The defection of 121 electoral votes from these once-reliable strongholds sealed the president’s doom, as shown by the collective results for the 15 states that had backed him in 1836:

| Year | Van Buren PV% | Whig PV% | Van Buren EV | Whig EV |

| 1836 | 54.62% | 45.25% | 170 | 0 |

| 1840 | 49.19% | 50.53% | 49 | 121 |

Harrison was much more effective, maintaining his grip on all but one of the 11 states that the Whigs had won four years earlier. The sole exception was South Carolina, whose legislative leaders continued to cast the state’s electoral votes without interference from its pesky citizens. The other 10 states showered Harrison with more than 56 percent of their popular votes.

Van Buren was one of the master politicians of his age. His manipulative skills had earned him the nickname “Little Magician” and the admiration of Horace Greeley, the famous and opinionated editor. “I believe his strength lay in his suavity,” wrote Greeley. “He was the reconciler of the estranged, the harmonizer of those who were at feud.”9

But there were limits to Van Buren’s powers, as demonstrated by the drubbing he received from Harrison. The outgoing president bitterly attributed his defeat to “the instrumentalities and debaucheries of a political Saturnalia in which reason and justice had been derided.”10 It was a misreading of the election of 1840. The bombastic elements of the Whigs’ campaign had been highly effective—the politician’s one true test of value—and they would be employed by countless candidates for generations to come.

ELECTION NO. 15: 1844

Mar tin Van Buren recovered nicely from his devastating loss to William Henry Harrison. Critics had dubbed him “Martin Van Ruin” because of the faltering economy in 1840, but their grievances were largely forgotten by 1844. Harrison was dead by then, and his successor, John Tyler, seemed unequal to the presidency. A comeback was in the cards.

Van Buren’s path to the Democratic nomination was virtually unobstructed. A clear majority of the delegates—nearly 55 percent—voted for him on the first ballot. The party’s heart still belonged to him.

The nomination, however, did not. A majority would have sufficed to win the endorsement of the Whig Party or any other major party in American history, but not the Democratic Party prior to 1936. The Democrats required a two-thirds supermajority in those years, a threshold that Van Buren could not reach. He had spoken out against the annexation of Texas and its admission as a slave state—a stand the South would never accept. Eighty percent of the delegates from Eastern and Midwestern states voted for Van Buren on the first ballot, but fewer than 4 percent from the South followed suit.

This was the first of eight Democratic conventions in which the candidate who achieved the initial majority was unable to secure the nomination on the same ballot. Six of these front-runners were undeterred. They picked up additional support and triumphed on subsequent roll calls. The exceptions were Van Buren and Champ Clark, whose hopes were permanently dashed by the two-thirds rule:

| Year | First to a majority | Ballot | Winner | Ballot |

| 1844 | Martin Van Buren | 1 | James Polk | 9 |

| 1848 | Lewis Cass | 3 | Lewis Cass | 4 |

| 1856 | James Buchanan | 6 | James Buchanan | 17 |

| 1860 | Stephen Douglas | 23 | Stephen Douglas | 59 |

| 1876 | Samuel Tilden | 1 | Samuel Tilden | 2 |

| 1912 | Champ Clark | 10 | Woodrow Wilson | 46 |

| 1920 | James Cox | 43 | James Cox | 44 |

| 1932 | Franklin Roosevelt | 1 | Franklin Roosevelt | 4 |

Nobody had been a greater friend to Van Buren than Andrew Jackson, but the controversy over Texas strained their relationship. “The candidate for the first office should be an annexation man, and from the Southwest,” Jackson now insisted.11 He suggested a possibility that had not occurred to many: James Polk, a former speaker of the House of Representatives. Polk had left Washington in 1839 to assume the governorship of Tennessee, but was voted out of office after a single two-year term. He ran for governor again in 1843, and lost for a second time. “Henceforth, his career will be downwards,” crowed a Nashville newspaper.12 It was not a promising prelude to a presidential candidacy.

Yet the two-thirds rule was the great equalizer. Van Buren’s nomination had seemed to be preordained, but his supporters began to drift away after the first ballot. The former president could do nothing but fume about “the opposition and persecution to which I have been exposed.”13 Michigan’s Lewis Cass pushed into the lead on the fifth roll call, only to meet the same fate as Van Buren.

Polk didn’t receive a single vote until the eighth ballot, but the weary delegates quickly seized on him as a compromise candidate. He was acceptable to his fellow Southerners and especially to Jackson, a longtime friend. Northerners saw no reason to object. Polk was a quiet and well-liked man, not the type of Southern firebrand who would alienate voters who had qualms about slavery. He was backed by 87 percent of the delegates on the ninth ballot, making him the first person to be nominated by a major-party convention after being ignored on its initial roll call. It was a feat that three others would duplicate in later years, though each would require many more ballots:

| Candidate | FB% | LB% | Ballot | |

| James Polk (D-1844) | 0.0% | 86.84% | 9 | |

| Franklin Pierce (D-1852) | 0.0% | 96.88% | 49 | |

| Horatio Seymour (D-1868) | 0.0% | 100.00% | 22 | |

| James Garfield (R-1880) | 0.0% | 52.78% | 36 | |

The Democrats would retain the two-thirds rule for 92 years after Polk’s nomination. It didn’t stir any particular controversy until Clark’s defeat in 1912, followed by lengthy and divisive conventions in 1920 and 1924, the latter droning on for 103 roll calls. The final straw came in 1932, when Franklin Roosevelt easily achieved a majority on the first ballot, yet struggled to surmount the two-thirds barrier on the fourth.

Roosevelt vowed to eliminate the accursed rule at the next convention. He chose the perfect man to lead the fight, Senator Bennett Clark of Missouri, who was described by a contemporary newspaper as “a modern Hamlet . . . avenging his father’s political death.”14 Clark zealously lined up the necessary votes to scuttle the two-thirds threshold. A majority would be good enough to win the Democratic presidential nomination from that point forward.

ELECTION NO. 16: 1848

The army was Zachary Taylor’s life. He enlisted in 1808 and distinguished himself in the War of 1812 and a series of frontier assignments and Indian skirmishes. His long-awaited reward came in 1838—the single star of a brigadier general—setting the stage for a slow fade to retirement.

Or so it seemed until the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846. Taylor led his troops to victory in four separate battles, achieving fame and glory as the war’s first American hero. A few newspapers began to see the White House in his future. “The idea that I should become president seems to me too visionary to require a serious answer,” Taylor scoffed. “It has never entered my head, nor is it likely to enter the head of any sane person.”15

He was wrong about that. The Whigs—forever on the lookout for a candidate who could be all things to all people—happily envisioned Taylor as their next nominee. They thought of him as the reincarnation of William Henry Harrison, the only Whig to be elected president to that point. Everybody had known Harrison’s name in 1840, yet nobody had known where he stood on the issues. The same was true of Taylor in 1848, with one key difference. Harrison had briefly served in both houses of Congress. Taylor had never held political office of any kind.

The Whigs pursued their new hero with single-minded persistence, and he eventually agreed to run. Taylor wasn’t able to duplicate Harrison’s landslide, but he did win the general election by a comfortable margin over his Democratic opponent, Lewis Cass.

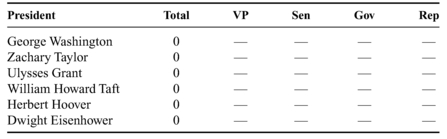

There are four way stations on the traditional path to the presidency— vice president, senator, governor, or representative. Thirty-seven of the 43 presidents held at least one of these elective positions before ascending to the nation’s highest office. Taylor was among the six exceptions:

Three of these six presidents accumulated other forms of political experience. Washington spent 15 years as a colonial legislator in Virginia, followed by a brief term in the Continental Congress. Taft was appointed as the territorial governor of the Philippines. Taft and Hoover both served in the cabinet.

Taylor, Grant, and Eisenhower, on the other hand, attained the presidency solely because of their military fame. They lacked conventional political credentials, though their exalted positions in the army had allowed them to view the inner workings of the federal government. “I have been in politics, the most active sort of politics, most of my adult life,” Eisenhower insisted. “There’s no more active political organization in the world than the armed services of the United States.”16

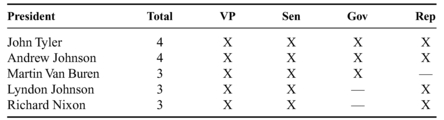

John Tyler and Andrew Johnson were the two presidents who acquired the broadest range of high-level political experience, spending time at all four way stations on their journeys to the White House. Another three presidents occupied three key positions apiece:

Not the most distinguished group, all in all. Lyndon Johnson was the only man on this list to be considered one of the nation’s 20 best presidents, according to a Siena College survey of 238 historians.17 Andrew Johnson finished dead last in the same rankings, and Tyler and Nixon were mired in the bottom 15. If we average the ranks of all five men, we come up with 29.8, essentially equaling 30th place.

The results were considerably better for the six presidents on our previous list. Two who hadn’t held any important elective offices—Washington and Eisenhower—were named among the 10 best presidents of all time. The average rank for the group was 22.2.

Here’s a breakdown for the various levels of experience:

| Key offices held | Presidents | Top 10 | Average rank |

| 0 offices | 6 | 2 | 22.2 |

| 1 office | 15 | 4 | 19.9 |

| 2 offices | 17 | 4 | 21.5 |

| 3 or 4 offices | 5 | 0 | 29.8 |

The sample sizes are small, so we can’t draw serious conclusions from these comparisons. But it’s interesting, isn’t it, that the presidents with the broadest experience in elective office have the worst collective rank. It’s just another reminder that past performance is no guarantee of future success, a point that John Kennedy stressed in one of his televised debates with Richard Nixon in 1960. “There is no certain road to the presidency,” said Kennedy, himself under fire for inexperience. “There are no guarantees that if you take one road or another that you will be a successful president.”18

Zachary Taylor would have agreed wholeheartedly.

ELECTION NO. 17: 1852

Millard Fillmore may have been an accidental president, but he was determined to win a term in his own right. The way he went about it, however, was strange at best and stunningly incompetent at worst.

Vice President Fillmore ascended to the White House in mid-1850 after the death of Zachary Taylor. He had barely settled into his new office when a controversial package of legislation landed on his desk. Congress had passed five bills known collectively as the Compromise of 1850, heralded as a solution to the growing discord between North and South. Fillmore decided to sign all five, even the Fugitive Slave Act, which obligated Northerners to capture runaway slaves and return them to their masters. He predicted that his signature would “draw down upon my head vials of wrath” from persons opposed to slavery, and he was proved correct.19

That wasn’t the strange part. The political atmosphere in the 1850s was so supercharged that no president could avoid making enemies. But Fillmore seemed to go out of his way to irritate and confuse people on both sides of the dispute. A prime example was his insistence that slavery was “an evil, but one with which the national government had nothing to do.”20 Southerners bristled at his negative characterization of slaveholding, while abolitionists decried his hands-off approach. Both groups were baffled by his refusal to take a clear stand on the ultimate issue of his time.

And yet Fillmore remained the front-runner for the Whig Party’s nomination in 1852. He drew 133 votes on the convention’s first ballot, falling just 16 short of a majority:

| Millard Fillmore | 133 |

| Winfield Scott | 131 |

| Daniel Webster | 29 |

| Others | 3 |

Webster clearly held the balance of power, much to Fillmore’s great fortune. The new president had done Webster a substantial favor two years earlier, when he chose the Massachusetts senator to be his secretary of state. The appointment had rescued Webster from a deteriorating relationship with his constituents, who were angered by his support for the Compromise of 1850. It should have been a simple thing for Fillmore to now seek a favor in return, asking Webster to release his delegates.

But the president inexplicably refused to reach out, even though he remained tantalizingly close to the nomination on ballot after ballot. Webster, in turn, declined to abandon his final campaign for the prize that had always eluded him. “My friends will stand firm,” he declared.21 The president’s passivity and his secretary of state’s egotism opened the door for Scott’s nomination on the 53rd roll call. “It all seemed so absurd,” wrote historian Robert Remini.22

If a sitting president wants a nomination, he is rarely denied. Thirty-six incumbents have launched formal campaigns for their party’s endorsement, and 32 have been successful. Fillmore’s consolation—a hollow one indeed—was that he ran the best race of the four rejected presidents:

| Candidate | FB% | CS | Nominee |

| Millard Fillmore (W-1852) | 44.93% | 45.85 | Winfield Scott |

| Franklin Pierce (D-1856) | 41.39% | 43.05 | James Buchanan |

| Chester Arthur (R-1884) | 33.90% | 37.07 | James Blaine |

| Andrew Johnson (D-1868) | 20.51% | 26.37 | Horatio Seymour |

It should be noted that three other incumbents made halfhearted efforts for another term. John Tyler toyed with an independent candidacy in 1844, and Harry Truman (1952) and Lyndon Johnson (1968) allowed their names to be floated in early primaries. But all three quickly folded their tents.

Millard Fillmore wasn’t that easily dissuaded. He would seek the presidency again in 1856 as the standard-bearer for the American-Whig ticket, but the results would be no better. His campaign score would once again hover in the vicinity of 45 points—and he would once again lose.

ELECTION NO. 18: 1856

The Democratic Party stunned the nation in 1852 when it handed its presidential nomination to an obscure ex-senator from New Hampshire— and nobody was more astounded than the new candidate and his family. Franklin Pierce stared speechlessly when notified of his selection. His wife simply fainted.

Few delegates knew much about Pierce when they tapped him on the 49th ballot at the Democratic convention. A trio of formidable politicians— James Buchanan, Lewis Cass, and Stephen Douglas—had eagerly pursued the nomination, yet each had fallen short. Delegates were forced to dig deeper for a candidate. Why not a man without enemies, a man who had served innocuously in the Senate and as a general in the Mexican War? Why not Franklin Pierce?

Closer study would have provided several reasons why not.

Two-thirds of Pierce’s votes on the final ballot in 1852 were cast by Eastern and Midwestern delegates. They later learned that the man from New Hampshire was a Southern sympathizer who disdained abolitionists as “reckless fanatics.”23 Word quickly spread that the new nominee was an alcoholic, soon to be mocked by the Whigs as “the hero of many a well-fought bottle.”24 Pierce’s worst shortcoming—a flaw that would doom his presidency—was his paucity of leadership ability. “He lacked a sustained feeling of self-confidence and was desirous of approbation,” conceded biographer Roy Nichols.25

Even a strong president would have struggled to maintain national unity in the stormy years prior to the Civil War, but Pierce had no chance whatsoever. His biggest blunder was signing the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which removed the ironclad prohibition against slavery in Midwestern territories. This stick of legislative dynamite ignited a political firestorm that destroyed any hope of reconciliation between North and South. An Illinois lawyer, “thunderstruck and stunned” by the possible extension of slavery into Kansas or Nebraska, was among the millions of Americans who suddenly felt a need to speak out.26 Abraham Lincoln emerged from political retirement to condemn the bill, and would soon become a rising star in the new Republican Party.

Franklin Pierce, on the other hand, no longer had a political future after affixing his signature to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He had become so controversial—and also seemed so overmatched by the presidency—that the Democratic Party’s power brokers wanted nothing to do with him in 1856. They preferred James Buchanan, who had spent the previous three years safely out of harm’s way as minister to Great Britain.

Yet Pierce persisted in seeking reelection. He trailed Buchanan by only 13 votes on the first ballot at the Democratic convention, but slipped farther and farther behind on subsequent roll calls. He eventually bowed to the inevitable, and withdrew from consideration.

His was an unprecedented defeat. Twenty-six elected presidents—men who attained the office through the ballot box—have run for second terms. Pierce was the only one to be denied renomination by his party. His campaign score plummeted more than 46 points between 1852 and 1856, the worst drop experienced by any president ever. Here are the seven who fell at least 10 points:

| Candidate (two races) | First CS | Second CS | Decline |

| Franklin Pierce (1852, 1856) | 89.52 | 43.05 | -46.47 |

| Herbert Hoover (1928, 1932) | 90.41 | 61.28 | -29.13 |

| William Howard Taft (1908, 1912) | 83.31 | 55.09 | -28.22 |

| George H. W. Bush (1988, 1992) | 87.86 | 66.86 | -21.00 |

| Jimmy Carter (1976, 1980) | 79.23 | 60.93 | -18.30 |

| Martin Van Buren (1836, 1840) | 80.26 | 65.49 | -14.77 |

| Benjamin Harrison (1888, 1892) | 79.71 | 68.40 | -11.31 |

Pierce’s base eroded dramatically in 1856. His incumbency and New Hampshire heritage meant little to his fellow Easterners, who tilted heavily toward Buchanan at the convention. The imbalance was even worse in the Midwest, where only 6 percent of the delegates stood by the president. If not for the loyalty of the South, which provided more than half of Pierce’s votes on the first ballot, his defeat would have been even more embarrassing than it was.

But Franklin Pierce had always been a resilient man, and he took his defeat remarkably well. The story of his immediate reaction has a whiff of the apocryphal, yet it has been recounted by several reputable historians. “There’s nothing left,” the president supposedly said, “but to get drunk.”27

ELECTION NO. 19: 1860

Abraham Lincoln won the presidency the hard way in 1860.

Nine Southern states barred the Republican nominee from their November ballots. A tenth, South Carolina, relied on its Democratic-controlled legislature to choose sides in the general election, effectively shutting out the Republicans. That meant a quarter of all votes in the Electoral College (73 of 303) were lost to Lincoln from the start.

Nor was that all. The Republican ticket appeared on the ballots of 23 states, but it was competitive in only 18. Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and Virginia were slave states that wouldn’t have supported Lincoln if he had been the sole candidate in the race. That meant another 47 electoral votes were out of reach.

The math was daunting. Lincoln would need five-sixths of the remaining 183 electoral votes, 152 in all, to eke out a victory over Stephen Douglas, John Breckinridge, and John Bell, his three high-profile opponents. If he failed to capture the biggest prize—New York and its 35 electoral votes—there was no way he could accumulate the required total. If he took New York but lost Pennsylvania, he would have to sweep the other 16 states to reach 156 in the Electoral College, just four votes above the cutoff.

It wasn’t easy, but Lincoln was able to swing it. He received the most popular votes in 17 of the 18 states, losing only New Jersey to Douglas (a half-defeat at worst, since four of the state’s seven electors subsequently supported Lincoln). He survived several close calls, taking New York by a relatively slender margin of 50,000 votes (out of 675,000 cast) and inching through in California, Illinois, and Oregon by fewer than four percentage points. Yet he managed to gather 180 electoral votes, 28 more than necessary.

Lincoln’s state-by-state results could best be described as feast or famine. He won a majority of the popular votes in 15 states, peaking at 75.73 percent in Vermont. But he finished below 25 percent in another 14 states, including the nine where he wasn’t even listed. The erratic nature of his performance is reflected by his average state deviation (ASD) of 25.44 points, the second-worst for any general-election winner.

A high ASD indicates that a candidate’s PV% varied widely from state to state, while a low figure is a sign of remarkable steadiness. We calculate ASD by comparing an individual’s PV% in each state to his national PV%, finding the absolute value of the difference. Lincoln, for example, received 39.82 percent of all popular votes nationwide. This is the resulting calculation for Vermont:

|(39.82% – 75.73%)| = 35.91 percentage points

If a candidate isn’t on the ballot in a given state, his PV% is pegged at zero. (Any state that doesn’t allow popular voting, such as South Carolina in 1860, is excluded from ASD calculations.) Here is the simple math for the nine states where Lincoln was kept away from the voters:

|(39.82% – 0.00%)| = 39.82 percentage points

The final step is to add the deviations for all eligible states, then to average them. Lincoln’s 32-state total of 814.16 percentage points yields an ASD of 25.44, which was surpassed only by John Quincy Adams’s 25.61 in the bizarre election of 1824:

| Winner | PV% | Average state deviation |

| John Quincy Adams (DR-1824) | 30.92% | 25.61 |

| Abraham Lincoln (R-1860) | 39.82% | 25.44 |

| Andrew Jackson (D-1832) | 54.24% | 18.86 |

| Andrew Jackson (DR-1828) | 55.97% | 18.01 |

| Grover Cleveland (D-1892) | 46.01% | 14.98 |

| William McKinley (R-1896) | 51.10% | 13.50 |

| Theodore Roosevelt (R-1904) | 56.41% | 13.38 |

| Calvin Coolidge (R-1924) | 54.04% | 12.46 |

| Warren Harding (R-1920) | 60.34% | 11.47 |

| Woodrow Wilson (D-1912) | 41.84% | 10.55 |

Lincoln’s high ASD, of course, reflects the extreme polarization of his times. Northern states were solidly behind the Republicans; Southerners feared and hated them. William Seward, who had pursued the Republican nomination and would become Lincoln’s secretary of state, spoke darkly of “an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces.”28 Lincoln, who inclined toward the same view, was not totally displeased when South Carolina seceded less than two months after his victory, setting the stage for the Civil War. “The tug has to come,” he said, “and better now than any time hereafter.”29

Other elections in the top 10 were similarly volatile because of controversial candidates (Andrew Jackson and Theodore Roosevelt), the rise of populism (1892 and 1896), the aftermath of World War I (1920), or the brief emergence of strong third parties (1912 and 1924).

At the opposite end of the ASD scale is the election of 1960, which featured a remarkably consistent campaign by John Kennedy. His PV% in 24 different states hovered within three percentage points of his national figure, while only six states deviated by more than 10 points. (Lincoln didn’t get within three points of his national PV% in any state in 1860, and he registered double-digit deviations in 29 of them.) Kennedy’s ASD was just a touch higher than four points:

| Winner | PV% | Average state deviation |

| John Kennedy (D-1960) | 49.72% | 4.07 |

| James Polk (D-1844) | 49.54% | 4.30 |

| William Henry Harrison (W-1840) | 52.88% | 4.55 |

| Franklin Pierce (D-1852) | 50.84% | 5.09 |

| Martin Van Buren (D-1836) | 50.83% | 5.30 |

| George H. W. Bush (R-1988) | 53.37% | 5.41 |

| Bill Clinton (D-1992) | 43.01% | 5.45 |

| Jimmy Carter (D-1976) | 50.07% | 5.45 |

| Ronald Reagan (R-1984) | 58.77% | 5.49 |

| Zachary Taylor (W-1848) | 47.28% | 5.81 |

Five of these 10 examples of stability occurred between 1960 and 1992, perhaps reflecting a subtle homogenization of national attitudes during the heyday of network television. But the trend did not endure. Cable television and the Internet greatly expanded the range of media options, and American society became increasingly fragmented and self-absorbed. Tom Wolfe first detected these tendencies in the 1970s—which he famously dubbed the “Me Decade”—and they subsequently grew in prominence.30

It has consequently become more difficult to fashion a national consensus, which is why average state deviation is on the rise again. Four of the Modern Era’s five steepest rates have been posted since 2000, with the election of 2012 at the very top of the list. Its ASD of 9.23 was the highest in more than 70 years.

ELECTION NO. 20: 1864

Abraham Lincoln’s 1864 campaign was shrouded in gloom. “This morning, as for some days past,” the president wrote in August, “it seems exceedingly probable that the administration will not be reelected.”31 The experts agreed. John Fremont, the 1856 Republican nominee, pronounced Lincoln to be “politically, militarily, and financially a failure.”32 Horace Greeley saw disaster ahead. “Mr. Lincoln is already beaten,” the editor wrote. “He cannot be elected.”33

It was all nonsense.

Millions of Northerners were unhappy about Lincoln’s inability to win the Civil War, which had dragged on for more than three years. But the numbers were always in the president’s favor. He had carried 18 states in 1860, and all 18 remained in the Union. Eleven of the 15 states that had opposed him were now part of the Confederacy. Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri were the only anti-Lincoln states from 1860 that would participate in the wartime election.

Eighty-eight votes disappeared from the Electoral College because of secession, 88 votes that the Democrats surely would have won in 1864. Most of the remaining electoral votes, on the other hand, were solidly in Lincoln’s column. The contrast is evident in this breakdown of 1860’s results, comparing the states that would subsequently decide to stay in the Union and those that would secede:

Lincoln had posted an anemic PV% of 39.82 percent in 1860, the second-lowest figure for any victorious candidate ever. But he no longer needed to worry about antagonistic Southerners diluting his national percentage. The 22 loyal states had given him almost 49 percent of their votes in 1860’s four-way race, and they were poised to deliver a majority in 1864.

The Republicans took one more step to guarantee Lincoln’s reelection, pushing the admission of three new states between 1861 and 1864: Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada. The latter, a vast desert populated by fewer than 40,000 settlers, was rushed into existence just eight days before the election. All three newcomers faithfully supported the Republican ticket.

Not that it mattered. Lincoln won easily, taking 55 percent of the nation’s popular votes. He carried 22 of the 25 states, even Maryland and Missouri, which had rejected him overwhelmingly in 1860. The result was a landslide victory over George McClellan, the Democratic nominee:

It didn’t hurt that the Union’s military fortunes took a turn for the better a few weeks prior to the election, but Lincoln was always destined to win a second term. He expressed doubt all the way to Election Day—“about this thing I am very far from being certain”—yet he carried 15 states by more than 10 percentage points and another four states by at least 5 points.34

Lincoln’s only nail-biting victories came in Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania. If he had lost all three, he still would have buried McClellan in the Electoral College by a count of 147–86. The election truly had been in the bag all along.

ELECTION NO. 21: 1868

Never has a prospective president pursued the office with less vigor than Ulysses Grant in 1868. Friends and aides swore that he never discussed the campaign. He didn’t make a single speech before the Republicans tapped him as their candidate, and he offered no response when informed of his nomination. “There was no shade of exaltation or agitation on his face, not a flush on his cheek, nor a flash in his eye,” wrote a member of his staff, Adam Badeau. “I doubt whether he felt elated, even in those recesses where he concealed his innermost thoughts.”35

The news certainly didn’t come as a shock. Leaders of both major parties had made no secret of their eagerness to nominate the hero of Appomattox. The Democrats were initially thought to have the inside track, given that Grant had supported James Buchanan in 1856 and Stephen Douglas in 1860. But the general’s disdain for Abraham Lincoln’s Democratic successor, Andrew Johnson, eventually tipped the balance to the Republicans.

Nor did victory in November come as a surprise. The Democratic convention, stripped of Grant as an option, droned through 22 ballots as it winnowed a field of nine uninspiring candidates. The eventual nominee, Horatio Seymour, hadn’t received a single vote on the first roll call. Seymour was no match for Grant—it’s difficult to think of anybody in 1868 who might have been—and the general buried him by a margin of nearly 3–1 in the Electoral College.

Grant’s win conformed with political tradition. The nation had been involved in three major conflicts prior to the Civil War, and all three propelled military leaders to the presidency. George Washington’s triumph in the Revolutionary War convinced all 69 electors to support him in 1789. Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison both served in Congress, but it’s difficult to imagine either man rising to the presidency without his battlefield victories in the War of 1812. Zachary Taylor had no possible chance of reaching the White House without his Mexican War fame.

It was inevitable that a military-political hybrid would emerge from the Civil War, and Grant was the obvious choice. Henry Adams, who turned savagely against him in later years, initially envisioned Grant as the reincarnation of General Washington. “Nothing could be more obvious,” Adams wrote. “Grant represented order. He was a great soldier, and the soldier always represented order. He might be as partisan as he pleased, but a general who had organized and commanded half a million or a million men in the field must know how to administer.”36

That has been the rationale behind every presidential campaign mounted by a military leader, and voters found it to be reasonably compelling until the late 19th century. There have been 17 instances of a general—never an admiral, always a general—becoming a qualified candidate without any intervening experience in Congress or as a governor. All but four occurred prior to 1890:

| Candidate | CS | Nominee | Winner |

| Benjamin Lincoln (F-1789) | 21.42 | — | — |

| George Washington (F-1789) | 96.18 | X | X |

| Winfield Scott (W-1840) | 27.88 | — | — |

| Winfield Scott (W-1848) | 27.96 | — | — |

| Zachary Taylor (W-1848) | 78.93 | X | X |

| Winfield Scott (W-1852) | 63.01 | X | — |

| Ulysses Grant (R-1864) | 13.35 | — | — |

| George McClellan (D-1864) | 61.66 | X | — |

| Ulysses Grant (R-1868) | 85.63 | X | X |

| Winfield Hancock (D-1868) | 18.46 | — | — |

| Winfield Hancock (D-1876) | 18.14 | — | — |

| Winfield Hancock (D-1880) | 72.24 | X | — |

| Clinton Fisk (PRO-1888) | 17.02 | — | — |

| Leonard Wood (R-1920) | 31.95 | — | — |

| Douglas MacArthur (R-1944) | 15.89 | — | — |

| Dwight Eisenhower (R-1952) | 89.56 | X | X |

| Wesley Clark (D-2004) | 12.00 | — | — |

This chart does not include the reelection campaigns of former military leaders who were elected president.

The military leaders who surfaced after Grant were rarely suited to the rough-and-tumble of national politics. Several potential candidates who seemed to have great promise either self-destructed or declined to make an effort:

It’s true that military heroism has enhanced the images of several presidents. Theodore Roosevelt is forever linked with San Juan Hill, as is John Kennedy with PT-109, and George H. W. Bush with Chichi Jima. But none was a top-level commanding officer. TR was a colonel; JFK and Bush were mere lieutenants.

Only one general since Grant has reached the White House without a partisan background. Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme commander of Allied forces in World War II, was a canny operator who had more interest in politics than commonly believed. His closest friends knew the truth. “Ike wants to be president so badly you can taste it,” said a fellow general, George Patton, as early as 1943, nine years before the desire became reality.39

There are no new Eisenhowers on the horizon, nor are there likely to be. Conscription came to an end in 1973, greatly reducing the likelihood of any budding politician having a military record. The inevitable finally occurred in 2012, when both parties nominated presidential candidates who lacked experience in the armed services. It marked the first election in 68 years without a veteran atop either ticket.40

ELECTION NO. 22: 1872

Here’s a trivia question. Only one major-party nominee has failed to win even a single vote in the Electoral College. Who was he?

If you’re like most people, your mind will flit immediately to the unfortunate candidates who were defeated by incredibly lopsided margins: Walter Mondale, George McGovern, Barry Goldwater, Alfred Landon, George McClellan, and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Yet you’d be wrong. All of those men received electoral votes. Not many votes, to be sure, but at least they weren’t shut out.

The same cannot be said for the famously headstrong and outspoken editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, who was nominated for president in 1872 by two parties, the Democrats and the Liberal Republicans.

Wielding the power of the press was never sufficient for Greeley, who lusted after public office his entire adult life. He ran for several state and federal positions, losing every race but one. It was his victory in an 1848 congressional election, ironically enough, that proved his ineptitude as a politician. “I have divided the House into two parties,” Greeley was soon able to report, “one that would like to see me extinguished, and the other is one that couldn’t be satisfied without a hand in doing it.”41

Yet he pressed on, setting his sights on the presidency in 1872. He toiled behind the scenes for more than a year to line up support. Political insiders were shocked when the new Liberal Republican Party gave him its nomination. The Democrats soon followed suit. “Six weeks ago, I did not suppose that any considerable number of men, outside of a lunatic asylum, would nominate Greeley for president,” gasped prominent Republican tactician Thurlow Weed when he heard the news.42

There were limits, however, to Greeley’s ability to surprise. He was unable to run a competitive race against incumbent Ulysses Grant in the fall. Grant trounced him by nearly 12 percentage points in the popular vote and carried all but six states. Not that it mattered to the heartbroken challenger by then. Greeley’s wife had passed away shortly before voters went to the polls, and his efforts to return to the Tribune would soon be rebuffed. He died in despair just 24 days after the election.

That left his 66 electors in a quandary. They had not yet cast their ballots in the Electoral College, and were uncertain which candidate to support. Sixty-three eventually scattered their votes among four men, with former Indiana senator Thomas Hendricks the most popular choice. But three Democratic loyalists from Georgia stuck with their party’s nominee to the bitter end. Congress debated at considerable length before deciding, not unreasonably, that Greeley “was dead at the time said electors assembled and cast their votes, and so not a person within the meaning of the Constitution.”43 His three electoral votes were disallowed.

ELECTION NO. 23: 1876

Rutherford Hayes’s first political victory set the tone for the rest of his life. The Cincinnati City Council was seeking a new city solicitor in 1858, and the 36-year-old lawyer expressed an interest in the position. Other contenders were better known, but the inexperienced Hayes got the job. He squeaked through by the margin of a single vote.

“His luck followed him to the end of his days,” one of the losing candidates for solicitor would grouse in later years, and it was true.44 Hayes soon marched off to serve in the Civil War—rising to the rank of major general—and was elected to the House of Representatives upon his return. This sudden combination of military and political success brought him to the attention of Ohio’s Republican leaders, who pushed him to run for governor. Hayes pursued the office three times in eight years, eking out a victory in each election:

| Election | Hayes | Opponent | Margin |

| 1867 | 243,605 | 240,622 | 2,983 over Allen Thurman |

| 1869 | 235,081 | 227,580 | 7,501 over George Pendleton |

| 1875 | 297,817 | 292,273 | 5,544 over William Allen |

The three Democrats he defeated were national figures—each would run for president at some point in his career—and pundits began to hint that Hayes, too, might be of national caliber. He waved off such talk, aware that his reputation hung by a thread of a few thousand votes. “Several suggest that if elected governor now, I will stand well for the presidency next year,” he wrote in his diary in 1875. “How wild! What a queer lot we are becoming!”45

The prophecy, of course, became reality. Hayes hovered on the periphery of the battle for the Republican nomination in 1876, finishing a distant fifth on the convention’s initial roll call. But other candidates began to drop by the wayside. The easygoing Ohio governor, a shadowy figure to most of the delegates, found himself locked in a duel with charismatic James Blaine, the former speaker of the House.

Blaine’s supporters, mesmerized by their hero’s electric personality, were rabidly loyal. But his many enemies hated him with a passion. The latter coalesced behind the obscure Hayes, boosting him to a majority on the seventh ballot. The final tally showed the two men less than four-and-a-half percentage points apart, which to this day remains the smallest margin of victory at any major-party convention.

It was at this point that Hayes’s luck finally seemed to have run out. He was the little-known nominee of a bitterly divided party. Critics mocked him as an uninspiring man with no real qualifications for the presidency. They conceded him a single virtue, honesty, a thin reed on which to base a campaign. “Hayes has never stolen,” moaned the New York World. “Good God, has it come to this?”46 His opponent, Samuel Tilden, was a celebrated reformer and the governor of vote-rich New York. A Democratic victory appeared a certainty.

Election night played out as expected. Tilden quickly bolted ahead, eventually widening his lead to nearly 255,000 votes. The New York Tribune headlined his victory. Hayes dashed off a note to his son, conceding that he had lost the election “and I bow cheerfully to the result.”47

His fellow Republicans were not as gracious. They noted that Tilden remained one vote shy of a majority in the Electoral College, and they set out to prevent him from attaining it. Lengthy books have been written about the political maneuvers, backroom deals, blatant fraud, and shameless vote-buying that occurred in subsequent months. I see no reason to dig through the details here.

What matters is the final count in the Electoral College: Hayes 185, Tilden 184. The new president reached the White House by the same margin that had secured his very first victory in Cincinnati—one vote.

The Democrats should have won easily, but they blundered away several opportunities to clinch the election. A flip of less than 4 percent of Hayes’s votes would have shifted any of 10 different states to Tilden. The New York governor needed to win one of them—only one— to be elected president. But all 10 slipped away:

| State | Hayes PV | Flip for Tilden win | Flip as % of Hayes PV |

| South Carolina | 91,786 | 445 | 0.48% |

| Ohio | 330,698 | 3,759 | 1.14% |

| California | 79,258 | 1,400 | 1.77% |

| Florida | 23,849 | 462 | 1.94% |

| Pennsylvania | 384,157 | 8,977 | 2.34% |

| Wisconsin | 130,668 | 3,371 | 2.58% |

| Louisiana | 75,315 | 2,404 | 3.19% |

| Oregon | 15,207 | 526 | 3.46% |

| Illinois | 278,232 | 9,811 | 3.53% |

| New Hampshire | 41,540 | 1,516 | 3.65% |

Frustrated Democrats threatened to reignite the Civil War to prevent Hayes’s inauguration. “Tilden or blood!” became their battle cry. But their candidate accepted the results with grace. Tilden was the only presidential candidate to lose a general election despite securing a popular-vote majority, yet he willingly left the stage. “I think I can retire to private life,” he said, “with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.”48

Rutherford Hayes, for his part, knew better than to press his luck. He immediately confirmed his “inflexible purpose” to leave Washington after serving his four-year term. He would not seek reelection.49

ELECTION NO. 24: 1880

Many Democrats were eager to renominate Samuel Tilden in 1880. They firmly believed the Republicans had stolen the previous election. Outrage ran so deep that the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives passed a nonbinding resolution declaring Tilden to be the real president. Here, at long last, was an opportunity to avenge his loss to Rutherford Hayes.

There was only one problem. Tilden didn’t seem particularly eager to enter the race. His health had deteriorated and indeed would remain unstable until his death six years hence. A reporter mentioned that the 1876 Democratic vice presidential candidate, Thomas Hendricks, was willing to take the same spot on the ticket if his ex-partner ran again. “I do not wonder,” Tilden joked, “considering my weakness.”50

Not everybody was dissuaded by the former nominee’s decision not to run. Thirty-eight delegates supported Tilden on the first ballot at the Democratic convention—sufficient to elevate him to the status of qualified candidate, though not enough to propel him into serious contention. Winfield Hancock, a Civil War general who had sought the presidency twice before, captured the nomination easily on the second roll call.

Tilden would seem to be an anomaly—a candidate who came within a hair’s breadth of the White House, yet declined to run the next time around. Most politicians, you might assume, would be eager to launch a second campaign after a flirtation with success.

The surprising truth is that many candidates in a similar position have opted to fold their tents. The following chart shows the 10 general-election losers who amassed the highest campaign scores. Seven refused to join the field of presidential candidates four years later, including Tilden and Al Gore, the two men who came closest to the ultimate prize:

| Candidate | CS | Next race | |

| 1. | Samuel Tilden (D-1876) | 75.14 | Declined to run |

| 2. | Al Gore (D-2000) | 74.51 | Declined to run |

| 3. | Thomas Jefferson (DR-1796) | 74.00 | Elected president over John Adams |

| 4. | John Kerry (D-2004) | 73.65 | Declined to run |

| 5. | Charles Evans Hughes (R-1916) | 73.55 | Declined to run |

| 6. | James Blaine (R-1884) | 73.26 | Ran again, but failed to win nomination |

| 7. | John Adams (F-1800) | 73.21 | Declined to run |

| 8. | Gerald Ford (R-1976) | 72.98 | Declined to run |

| 9. | Grover Cleveland (D-1888) | 72.27 | Elected president over Benjamin Harrison |

| 10. | Winfield Hancock (D-1880) | 72.24 | Declined to run |

Most of these men insisted they had no regrets about abandoning their presidential ambitions. Tilden fell back on his joke about the joys of being elected in 1876 without having to serve. Gore was predictably solemn. “I made the decision in the full awareness that it probably means that I will never again have an opportunity to run for president,” he said in December 2002, “and I’m at peace with that decision.”51 John Kerry, fourth on the list, announced in 2007 that his priorities had changed. Working in the Senate to end the war in Iraq, he said, had become more important than reaching the White House.52

There was truth behind these disavowals, yet none told the whole story. Other factors helped convince each man to forgo his pursuit of the presidency:

New enemies or rhetorical missteps can shut the window of opportunity with chilling quickness. Voters are mercurial, and the competition for their attention and affection is never-ending. “With luck,” concluded historian H. W. Brands, “a man might have one chance at the presidency.”54

The numbers bear him out. A total of 289 persons became qualified presidential candidates between 1789 and 2012. Two-thirds of them—194— ran only once. If we eliminate the 38 men who won general elections, the proportion rises to three-quarters, with 186 of the 251 unsuccessful contenders fading away after a single race.

There are few second chances in presidential politics.

ELECTION NO. 25: 1884

Democrats entered 1884 on an extensive losing streak. Their party hadn’t won a presidential election in 28 long years, not since James Buchanan’s ill-fated victory in 1856 set the stage for the Civil War.

Millions of Northern voters would forever blame the Democrats for instigating the bloodiest conflict in American history. This was an admittedly simplistic view, yet it contained an indisputable kernel of truth. Most secessionists had belonged to the Democratic Party until the very moment their states departed the Union. “All Democrats may not be rascals,” Horace Greeley had famously concluded, “but all rascals are Democrats.”55

The electorate had been punishing the party’s candidates ever since, including Greeley himself, who defied his own Republican rhetoric when he accepted the Democratic nomination in 1872. The six Republican nominees between 1860 and 1880 carried two-and-a-half times as many states as their Democratic opponents and won two-thirds of all electoral votes:

The two-stage Democratic strategy for reversing this trend in 1884 was both cynically pragmatic and dreamily sanguine:

The first part was easy. The Democratic Party was not as liberal in 1884 as it would later become, but its nominee, Grover Cleveland, was unusually conservative even for that era. He tirelessly supported the interests of big businesses, advocated extensive cuts in the federal budget, and showed no interest in social-welfare legislation. “Though the people support the government,” he declared, “the government should not support the people.”56 The New Republic concluded in 2012 that Cleveland would have been a Republican in the 21st century, calling him “the White House occupant who best represented the views that now dominate the American right.”57

The second prong of the Democratic plan, however, seemed unlikely. The Republicans had shown a deft touch in choosing their recent nominees, notably Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Grant. Cleveland expected his opponent in the general election to be George Edmunds, a Vermont senator of unquestioned skill and rectitude.

But the Republican convention opted for James Blaine, who was making his third try for the nomination. Blaine was perhaps the most controversial politician in America, a magnetic orator who inspired great loyalty or hatred. Roscoe Conkling, a former senator from New York, was among the many Republicans who refused to support the party’s nominee. “No, thank you,” he thundered. “I don’t engage in criminal practice.”58

What followed was perhaps the most vicious campaign in American history. “Party contests have never before reached so low a depth of degradation,” the Nation complained with considerable justification that fall.59 The details are not our concern here. What is of interest is the fact that the Democratic strategy worked, though by the barest of margins.

The election pivoted on Cleveland’s home state. The governor might have been expected to win New York easily, but he wasn’t as popular as the Democrats had assumed. Cleveland carried the state’s 36 electoral votes by just 0.09 percentage points, the tightest margin in New York’s history:

| Year | Winner in New York | Loser in New York | Margin (points) | Flip |

| 1884 | Grover Cleveland (D) | James Blaine (R) | 0.09 | 524 |

| 1864 | Abraham Lincoln (R) | George McClellan (D) | 0.92 | 3,375 |

| 1948 | Thomas Dewey (R) | Harry Truman (D) | 0.99 | 30,480 |

| 1844 | James Polk (D) | Henry Clay (W) | 1.05 | 2,554 |

| 1888 | Benjamin Harrison (R) | Grover Cleveland (D) | 1.09 | 7,187 |

Blaine was victimized in New York by Republican defections, unexpectedly low turnout, and the controversial remarks of the Reverend Samuel Burchard. The Presbyterian minister blasted the Democrats as the party of “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion” in a heavily publicized speech in late October, undoubtedly inspiring thousands of Catholic laborers to support Cleveland. And yet a flip of just 524 votes still would have given the state—and the presidency—to Blaine.

The Republican candidate knew where to place the blame. “I should have carried New York by 10,000,” Blaine later wrote, “if the weather had been clear on Election Day and Dr. Burchard had been doing missionary work in Asia Minor or Cochin China.”60

ELECTION NO. 26: 1888

The Democrats had five good reasons to anticipate victory in 1888:

And yet it was the Republicans who emerged victorious in 1888. Cleveland clung to a narrow lead of 89,300 popular votes, but Harrison carried 20 of the 38 states and rang up a decisive majority in the Electoral College.

Twelve presidents with a PI of at least 9.0 have been nominated for new terms. Nine were reelected, most of them by impressively large margins. Two of the defeated incumbents (Martin Van Buren and Jimmy Carter) lost to charismatic challengers in the midst of economic downturns. Cleveland did not share these burdens—the aloof Harrison was nicknamed the “Human Iceberg,” and the economy was on the upswing in late 1888—yet he suffered the same fate:

| Candidate | PI | EV% | CS | Winner |

| George Washington (F-1792) | 9.7 | 100.00% | 96.18 | X |

| Franklin Roosevelt (D-1936) | 10.0 | 98.49% | 95.88 | X |

| Lyndon Johnson (D-1964) | 9.3 | 90.34% | 93.24 | X |

| Thomas Jefferson (DR-1804) | 9.2 | 92.05% | 93.05 | X |

| Franklin Roosevelt (D-1940) | 9.6 | 84.56% | 89.94 | X |

| Ulysses Grant (R-1872) | 9.0 | 81.95% | 89.28 | X |

| Franklin Roosevelt (D-1944) | 9.4 | 81.36% | 88.61 | X |

| Calvin Coolidge (R-1924) | 9.1 | 71.94% | 85.63 | X |

| George W. Bush (R-2004) | 9.3 | 53.16% | 78.71 | X |

| Grover Cleveland (D-1888) | 9.2 | 41.90% | 72.27 | — |

| Martin Van Buren (D-1840) | 9.1 | 20.41% | 65.49 | — |

| Jimmy Carter (D-1980) | 9.0 | 9.11% | 60.93 | — |

The Republicans’ formula for victory in 1888 required two key ingredients—a prodigious amount of money and an army of dedicated volunteers. The chairman of the Republican National Committee, Matthew Quay, raised the unheard-of sum of $3 million, the equivalent of $80 million in 2015.62 He deployed platoons of public speakers across the country. Harrison himself delivered more than 80 speeches from his front porch in Indianapolis, this in an era when presidential candidates rarely said anything at all.

The Democratic campaign, on the other hand, was underfunded and sluggish. Cleveland promised upon accepting the party’s nomination that he would “not dwell upon the acts and the policy of the administration [since] its record is open to every citizen of the land.”63 He was as good as his word. He refused to give another speech, nor did he allow his cabinet members to appear in public.

The Republican victory probably shouldn’t have been a surprise, given the massive disparities between the financial resources and energy of the two parties, but even the president-elect was shocked. “Providence has given us the victory,” Harrison exclaimed.

Quay scoffed at his candidate’s naivete. The party chairman privately admitted that several of his minions had been “compelled to approach the gates of the penitentiary” in order to lock up key states. “Think of the man,” Quay said of Harrison. “He ought to know that Providence hadn’t a damn thing to do with it.”64

ELECTION NO. 27: 1892

Few presidents willingly abandon the pomp and circumstance of the White House. Nearly two-thirds of the elections between 1792 and 2012—36 of 56—featured incumbents who were actively seeking an additional term. Twelve presidents stepped aside in other races because they had already scored a pair of national victories. The first eight members of this latter group bowed out in deference to the two-term tradition. The remaining four, beginning with Dwight Eisenhower, were pushed out by the Twenty-second Amendment. (Barack Obama will become the fifth forced retiree after the election of 2016.)

That leaves eight incumbent presidents who decided not to pursue reelection, despite being eligible to run. Three initially showed signs of ambition, briefly launching halfhearted campaigns before deciding to pull the plug. The other five never deviated publicly from their plans to leave the White House:

| Election | Incumbent | Decision |

| 1844 | John Tyler (I) | Dropped out in August |

| 1848 | James Polk (D) | Never entered the race |

| 1860 | James Buchanan (D) | Never entered the race |

| 1880 | Rutherford Hayes (R) | Never entered the race |

| 1908 | Theodore Roosevelt (R) | Never entered the race |

| 1928 | Calvin Coolidge (R) | Never entered the race |

| 1952 | Harry Truman (D) | Dropped out after New Hampshire primary |

| 1968 | Lyndon Johnson (D) | Dropped out after New Hampshire primary |

The five who abstained were motivated by a mixture of personal honor, exhaustion, and political precedent:

These men were atypical in their willingness to depart quietly. Bill Clinton spoke for most presidents when he confessed his reluctance to leave his post. If the Constitution had allowed a third term, Clinton would have been game. “Oh, I probably would have run again,” he conceded a few weeks before moving out of the White House in 2001.67

Theodore Roosevelt originally denied such feelings. He shocked reporters by truncating his career on the very night in 1904 that he won a full term in his own right. “Under no circumstances,” he announced, “will I be a candidate for or accept another nomination.”68 But Roosevelt came to regret this declaration even before leaving office. He admitted to a visitor in 1908 that he enjoyed his job too much to give it up.

It seemed inevitable that Roosevelt would succumb to presidential fever again. He mounted an unsuccessful challenge to William Howard Taft for the 1912 Republican nomination, then created the Progressive Party as his vehicle for the fall campaign. He was badly defeated, the same fate that befell another three ex-presidents who sought to reclaim the job. None was more determined than Martin Van Buren, the only former commander in chief to run twice (and lose twice) after being voted out of office.

Grover Cleveland was the sole exception to this dreary record. He set out to avenge his 1888 loss to Benjamin Harrison, proceeding to do precisely that in 1892. His campaign score of 80.73 was easily the best for any former president:

| Former president | PI | CS | ROP |

| Grover Cleveland (D-1892) | 9.1 | 80.73 | 89 |

| Theodore Roosevelt (R/P-1912) | 10.0 | 66.37 | 66 |

| Martin Van Buren (D-1844) | 8.7 | 50.00 | 57 |

| Millard Fillmore (AW-1856) | 7.4 | 45.15 | 61 |

| Ulysses Grant (R-1880) | 8.5 | 42.34 | 50 |

| Martin Van Buren (FS-1848) | 7.1 | 42.02 | 59 |

Cleveland, as most schoolchildren know, was the only president to win two nonconsecutive terms, a distinction that has earned him a special place in the American pantheon. But let’s not get carried away. Harrison was a remarkably easy target. The incumbent grew to be so unpopular that one of his own Republican appointees—a young civil-service commissioner named Theodore Roosevelt—felt free to blast him as a “cold-blooded, narrow-minded, prejudiced, obstinate, timid old psalm-singing Indianapolis politician.”69

Yet Cleveland fell considerably short of a majority of popular votes, squeaking past Harrison by only three percentage points. His ROP of 89 was the worst for any general-election winner up to that time—the true sign of an underperforming candidate—and it would remain the worst until George W. Bush bottomed out at 85 in 2004.

ELECTION NO. 28: 1896

William Jennings Bryan was convinced of his ability to win the Democratic presidential nomination in 1896, a belief that moved party professionals to laughter. The former two-term congressman was just 36—a single year above the minimum age for the presidency—and he had recently lost a Senate race in Nebraska. It was hard to imagine a candidate who faced longer odds.

But the chuckling ceased when Bryan began to speak at the Democratic convention. His voice boomed into every corner of the Chicago Coliseum as he advocated the free coinage of silver, an ostensible remedy for the tight money supply fostered by the gold standard. “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns,” he shouted. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”70 The roar from the delegates was deafening. Bryan was nominated the next day on the fifth ballot.

Democratic leaders were impressed by the way he had stampeded the convention, but they feared there was little substance behind Bryan’s soaring rhetoric. Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld turned to a fellow delegate. “I’ve been thinking over Bryan’s speech,” Altgeld muttered. “What did he say, anyhow?”71

Thus the lasting image of William Jennings Bryan was fixed—a galvanizing speaker and charismatic candidate, yet an intellectual lightweight who lacked the gravity that Americans prefer in their presidents. “Bryan, at his best, was simply a magnificent job-seeker,” H. L. Mencken sneered.72 And it was true that he made his mark by pursuing—not winning—the presidency. Bryan lost to William McKinley in 1896, dusted himself off for their rematch in 1900 (only to lose again), and launched a third presidential candidacy in 1908, still only 48 years old. He lost once more.

It was Bryan’s youth, of course, that made possible his multiple campaigns. If he had been 55, the average age of the other six Democratic contenders in 1896, he might have been nominated only once, certainly no more than twice. The party would have shuffled him off as a senior statesman by 1908, when he would have been 67 years old.

Events unfolded in similar ways for the other men who became qualified candidates before their 40th birthdays. There were seven of them in all, and most remained politically active for decades. Five mounted three presidential campaigns apiece. The group accounted for 17 qualified candidacies and eight major-party nominations. Yet none of its members ever won a general election:

All seven of these youthful contenders were nakedly ambitious, though some would later regret their rapid ascensions. George McClellan’s political career stemmed from his elevation to the position of general in chief of the Union Army at the precocious age of 34. “It probably would have been better for me personally,” he later wrote, “had my promotion been delayed a year or more.”73 Thomas Dewey felt the same way about his meteoric rise from local prosecutor to presidential nominee. “Everything came too early for me,” he admitted near the end of his life.74

If William Jennings Bryan had a similar moment of introspection, it was never recorded. Thomas Gore, then an elderly ex-senator from Oklahoma, once told his grandson about a carriage ride he had shared with Bryan immediately after the latter secured his third Democratic nomination in 1908. “You know,” Bryan said to Gore, “I base my political success on just three things.”

The old man paused. His grandson, Gore Vidal, who would grow up to be a famous novelist, impatiently asked about Bryan’s three secrets. What were they?

“I’ve completely forgotten,” replied Thomas Gore. “But I do remember wondering why he thought he was a success.”75

ELECTION NO. 29: 1900

The election of 1900 was predestined to be McKinley vs. Bryan II, a sequel to the 1896 race. The other prospective contenders backed away, allowing the starring characters to be nominated unanimously by their respective parties. The field—just two qualified candidates—was the smallest since 1828.

Not everybody was pleased about the rematch. Many Republicans were privately critical of their standard-bearer. Even the party’s vice presidential nominee, Theodore Roosevelt, had once groused that William McKinley possessed “the backbone of a chocolate eclair.”76 Conservative Democrats were openly contemptuous of the flamboyant William Jennings Bryan. “Hundreds of thousands of our prominent Democrats are convinced that Bryan’s nomination means defeat, and yet they are silent,” moaned Grover Cleveland. “What a sad condition!”77

The outcome was easily predicted, given that the key issues were running McKinley’s way in 1900. The economy had rebounded a bit since the previous election, removing the pressure for free coinage of silver, which had been Bryan’s pet issue. And a quick victory in 1898’s Spanish-American War had bathed the administration in military glory. The slogan for the president’s reelection campaign—“Let Well Enough Alone”—nicely captured the nation’s mood of self-satisfaction.78

McKinley won by a sizable margin, becoming the first presidential candidate to defeat the same opponent in consecutive general elections. He bumped up his campaign score the second time around (from 81.24 in 1896 to 82.89 in 1900). He boosted his EV% by nearly five points (from 60.63% to 65.32%). And he carried 28 states, 5 more than in 1896.

Four rematches had occurred prior to 1900, all resulting in splits. The candidate who lost the first election bounced back in each case to win the second. McKinley broke that pattern in 1900, and Dwight Eisenhower followed suit in the 1950s, trouncing Adlai Stevenson in back-to-back races.