The Founding Fathers are American deities, revered for their perceived benevolence, sagacity, and lower-case-D democratic spirit. Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, George Washington, and other stalwarts of that golden generation are fondly remembered as “philosopher-kings [who] strode the public stage, dispensing wisdom with gentle civility,” as historian Ron Chernow so nicely puts it.1

And why not? Didn’t the Founders believe in the inherent goodness and intelligence of the common man? Didn’t they bestow the blessings of liberty upon an entire continent? Didn’t they spurn the rabid partisanship that fouls our political discourse today?

Well, no.

We’ve already seen that the Electoral College sprang from the Founders’ distrust of everyday Americans. John Adams contended that only the upper crust could guide the new country’s development. “The people of all nations,” he insisted, “are naturally divided into two starts, the gentleman and the simple men.”2 Gouverneur Morris expressed his disdain more colorfully, dismissing the masses as “poor reptiles.”3

It was natural that men who held such opinions would dispense liberty in miserly portions. White males who owned property were allowed to participate in elections for the House of Representatives, but not the Senate, whose members were chosen by state legislatures. All others—women, minorities, white men without property—were consigned to political impotence. Enslaved blacks were even denied demographic equality. The Constitution mandated that each slave be counted as three-fifths of a person when House seats were apportioned by population.

It’s true that the Founders condemned partisanship. A party system, said Washington, “agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms.”4 Thomas Jefferson agreed. “If I could not go to heaven but with a party,” he famously said, “I would not go there at all.”5 But this rhetoric obscured a generational zest for political battle. “Despite their erudition, integrity, and philosophical genius,” says Chernow, “the Founders were fiery men who expressed their beliefs with unusual vehemence.”6 Underlying this feistiness was the strictest of codes. All combatants, whatever their party affiliation, agreed that the wealthy and the well-educated should remain firmly in charge.

The Elite Era spanned 13 presidential elections from 1789 to 1836. Gentlemen, as defined by John Adams, retained ironclad control of the political process until the tail end of that period. Popular voting did not become widespread until 1824, and conventions did not appear until 1832. Neither innovation seemed immediately dangerous. Popular-vote totals were insignificant in those early elections, with fewer than 100,000 votes being cast by every 1 million Americans. (The ratio would finally climb into six figures in 1840.) And the conventions of 1832 and 1836 were harmonious affairs, resulting in nominations that were unanimous or nearly so. (The Whig Party’s 1840 convention—actually held in December 1839—was the first to require more than a single ballot to select a nominee.)

Yet change was coming, personified by Andrew Jackson, the final two-term president of the Elite Era. Jackson was lionized as a valiant Tennessee backwoodsman who scorned politicians and battled the privileged classes, even though he had served in both houses of Congress and was a wealthy land speculator himself. He earned public acclaim as a general during the War of 1812, a conflict that produced few American heroes. Competing candidates were mystified by his enduring public appeal. “I cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult, and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy,” grumped Henry Clay.7 But Jackson blazed a new trail to the White House, one that bypassed the turnpike painstakingly constructed by the Founders.

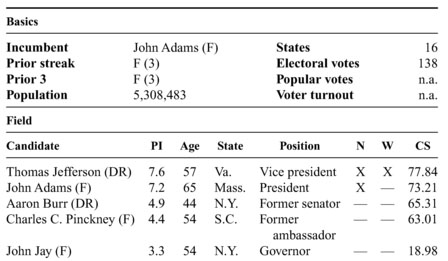

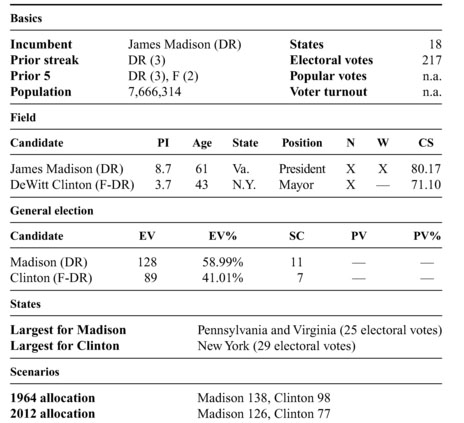

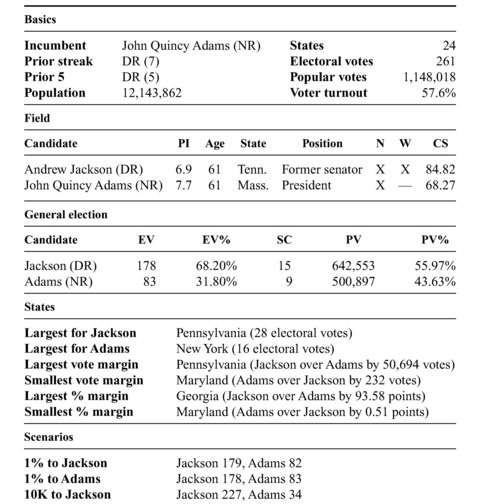

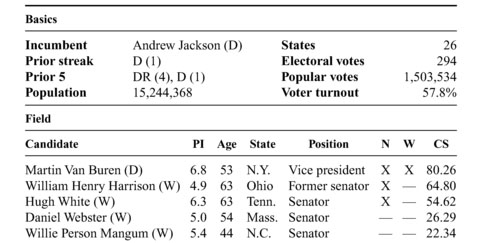

The following chart offers a quick review of the Elite Era’s presidential elections. All major-party nominees are shown for any given year, with the winner listed first. Each candidate is followed by his popular-vote percentage, electoral-vote total, and campaign score:

The nominees on this list were starkly different from their counterparts in the Modern Era. Older men who held unelected or relatively insignificant positions fared well in the nation’s first elections, no real surprise given the closed nature of the political system. Longevity and entrée to elite circles were powerful attributes for candidates in the period from 1789 to 1836. Popularity with everyday Americans mattered little, at least until Jackson arrived on the political scene. Seven winners of elections in this period were in their 60s. The median age for all 13 victors was 60.7. Three cabinet members won the presidency, as did three vice presidents.

Today’s nomination process—dominated by primary elections and driven by television advertising—naturally favors vigorous candidates who have political experience. Only 3 of the 14 general-election winners since 1960 were older than 59. Their median age of 55.1 was 5.5 years younger than the corresponding figure for 1789–1836. Governors and senators are the most successful presidential candidates these days. Just two sitting cabinet members have been elected to the White House since the Elite Era drew to a close, with Herbert Hoover being the last in 1928. And George H. W. Bush is the only vice president to ascend directly to the top job since Martin Van Buren.

The story is told in different ways by different people. John Kennedy assembled an impressive team after winning the 1960 presidential election, drawing effusive praise from columnists and correspondents. One of his new aides—either Richard Donahue or Arthur Schlesinger Jr.—was even acclaimed as “coruscatingly brilliant” by Theodore White or Time magazine or Newsweek or somebody. No one agrees on the source.

But there is no doubt about the reaction. Kennedy dismissed the praise, scorning it as excessive for a new administration that had barely squeaked into office. “Sometimes these guys forget that 50,000 votes the other way, and they’d all be coruscatingly stupid,” he muttered.8

It was actually a smaller number than that. If as few as 18,269 votes had been shifted from Kennedy to Richard Nixon in Illinois, Missouri, and five smaller states, the outcome in the Electoral College would have been reversed. If Nixon’s share of the popular vote had been bumped up by a mere percentage point in each state, he would have buried Kennedy by 70 electoral votes.

It’s fascinating to play the “what if” game, to imagine the twists and turns that could have changed the course of American politics. What if Nixon had squeaked through to win the presidency in 1960? What would have happened to Kennedy? And what about Lyndon Johnson, Gerald Ford, and other future presidents whose careers would have been significantly altered? “History is as much a product of chance as of the broader forces at play,” writes Jeff Greenfield, a journalist who was once a speechwriter and political aide. “A missed meeting, a shift in the weather, a slightly different choice of words open up a literally limitless series of possibilities.”9

I’ll offer my own version of alternate history in this chapter and the three that follow. Two “what if ” scenarios are presented for each election through 1820, and six for every election after that. They fall into these general categories:

The principle is the same in every case. We alter the course of an election—either its distribution of popular votes or its alignment of electoral votes—and then determine the impact on the Electoral College. There are two versions of each scenario. The two popular-vote leaders in any given election are beneficiaries of 1% and 10K adjustments, while separate allocations are based on the electoral-vote numbers for 1964 and 2012.

A pair of examples should suffice. Kennedy defeated Nixon by 303–219 in the real-life Electoral College. If Kennedy’s PV% had been increased by one percentage point in each state, he would have picked up Alaska and California, widening his margin to 338–184. But if Nixon had gained one point across the board, he would have carried an additional seven states, notably Illinois and New Jersey. The resulting count: Nixon 296, Kennedy 226.

Allocations don’t change the popular-vote outcome, just the number of electoral votes cast by each state. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, carried 18 states for a total of 180 electoral votes in 1860. But if the Electoral College had been aligned the same way back then as in 1964, he would have received 282 votes. Why the big difference? California, Illinois, and Michigan wielded a modest amount of power in 1860, depositing 21 electoral votes in Lincoln’s column. The subsequent growth of all three states quadrupled their total to 87 a century later.

Two final points. You might reasonably ask how the base years for allocations were chosen. The answer is simple enough: 1964 was the first year that all 51 states (including D.C.) participated in a presidential election, while 2012, of course, was the most recent election.

I should also acknowledge the occasional intrusion of subjectivity. Scenarios are typically straightforward. You make a specific adjustment, then you recalculate the electoral-vote count. But a few cases require some sleight of hand. The best example is 1872. The Democratic nominee, Horace Greeley, died after voters went to the polls, but before the Electoral College met. His electors subsequently divided their votes among four candidates. I assumed that most Democrats would have coalesced behind their top vote-getter, Thomas Hendricks, in my hypothetical elections, so I made my calculations accordingly.

Can I prove that my assumption was correct? Of course not. But that’s the beauty of alternate history. There are no demonstrably wrong answers.

Chapters 2–5 contain chronological discussions of all 57 presidential elections. At the very top of each entry is a detailed box score that offers a wide array of facts and figures. Here’s a guide:

| Basics |

| Incumbent: Sitting president as of Election Day, followed by his party affiliation at the time. |

| Prior streak: Party that won the most recent presidential election or string of elections, with the streak’s length in parentheses. |

| Prior 5: Parties that won any of the five previous presidential elections. |

| Population: Official census population for any year ending in 0. Estimate by the author (through 1896) or the U.S. Census Bureau (since 1904) for any other year. |

| States: Number of states that cast votes in the Electoral College. (The District of Columbia is counted as a state.) |

| Electoral votes: Number of electoral votes cast. (If one or more electors did not vote, this figure will not equal the total membership of the Electoral College.) The number for each double-ballot election (1789-1800) is the number of electors, not the number of electoral votes cast. |

| Popular votes: Number of popular votes cast. |

| Voter turnout: Percentage of eligible persons of voting age who participated in the election. |

| Field |

| Candidate: Any candidate who posted a campaign score of 10.00 or higher, followed by his party abbreviation. Candidates are ranked in order of CS. |

| PI: Potential index. |

| Age: Age as of November 1 of the given year. |

| State: State in which the candidate maintained a voting address. |

| Position: Position by which the candidate was best known, usually his current or most recent position. |

| N: Major-party nominees are designated by an X. |

| Field |

| W: General-election winner is designated by an X. |

| CS: Campaign score. |

| Nomination |

| Candidate: Any candidate in the field who received support for a given party’s nomination. Candidates are ranked in order of ConLB, then ConFB, then PriV |

| ConFB: Votes received on the first ballot at a convention. Fractional totals have been rounded to the nearest whole number. |

| FB%: Percentage of all votes cast on the first ballot. |

| ConLB: Votes received on the last ballot at a multiballot convention. (The number of the last ballot is indicated in brackets.) Fractional votes have been rounded to the nearest whole number. |

| LB%: Percentage of all votes cast on the last ballot. |

| PriW: Number of primary elections won by a candidate. |

| PriV: Votes received in a party’s primary elections. |

| PriV%: Percentage of all votes cast in a party’s primary elections. |

| General election |

| Candidate: Any candidate in the field who received support in the general election. Party abbreviations are given for major-party nominees, as well as qualified candidates who were nominees of minor parties. Candidates are ranked in order of EV then PV |

| EV: Electoral votes. |

| EV%: Percentage of all electoral votes cast. Percentages for each double-ballot election (1789-1800) are based on the number of electors, not the number of electoral votes. |

| SC: States carried. (If two or more candidates tied for the electoral-vote lead in a given state, each is credited with a state carried.) |

| PV: Popular votes. |

| PV%: Percentage of all popular votes cast. |

| States |

| Largest for a candidate: Largest state (in terms of electoral votes) carried by a given candidate. All candidates who carried at least two states are listed. |

| Largest vote margin: State with the largest gap in popular votes between the top two candidates. |

| Smallest vote margin: State with the smallest gap in popular votes. |

| Largest % margin: State with the largest gap in percentage points. |

| Smallest % margin: State with the smallest gap in percentage points. |

| Scenarios |

| 1% to a candidate: Electoral-vote count that would occur if a candidate’s share of each state’s popular votes were increased by one percentage point, while his chief opponent’s share were decreased by one percentage point in each state. (This scenario is shown for the top two candidates in the national PV count.) |

| 10K to a candidate: Electoral-vote count that would occur if a candidate were given an additional 10,000 popular votes in each state, while his chief opponent had 10,000 votes taken away in each state. (This scenario is shown for the top two candidates in the national PV count.) |

| 1964 allocation: Electoral-vote count that would occur if each state were allocated the same number of electoral votes as in 1964. |

| 2012 allocation: Electoral-vote count that would occur if each state were allocated the same number of electoral votes as in 2012. |

| Past and future nominees |

| List: All past or future major-party nominees who were alive on Election Day, with ages in parentheses, A child who had not yet reached his first birthday is designated by <1. |

ELECTION NO. 1: 1789

The Electoral College gave George Washington its unanimous stamp of approval, but he wasn’t particularly happy about winning the first presidential election.

“My movements to the chair of government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution,” Washington moaned.10 Cheering throngs lined the road as he slowly made his way from Mount Vernon to New York City, the nation’s temporary capital, yet he went with great reluctance.

What else could he have done? All 69 electors had picked him. It’s possible, given the quirks of the double-ballot system, that a handful of voters might have acted upon a mischievous desire to bury the famous general in the vice presidency. (Even Washington had enemies.) But most of the nation’s prominent citizens were effusive in their enthusiasm. “We cannot, sir, do without you,” an ex-governor of Maryland wrote him, “and I and thousands more can explain to anyone but yourself why.”11

Washington’s most devoted supporters hoped that he might be crowned king of the United States, or at the very least, named president for life. These were logical concepts at a time when most nations were ruled by monarchs, yet Washington resisted them. He had written as early as 1782 that the creation of a royal class would be “big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country.”12

But what if he had deigned to wear the crown? Who would rule the United States today?

Washington left no direct descendants, so there is no simple answer. Ancestry.com, a genealogical website, sent its researchers shinnying up and down the tangled branches of the Washington family tree in 2008. The site wasn’t 100 percent positive, but it eventually concluded that the most likely present-day monarch would have been Paul Emery Washington, a retired regional manager of a building supply company in San Antonio.13 “I doubt if I’d be a very good king,” he said with unroyal modesty. “We’ve done so well as a country without a king, so I think George made the best decision.”14

What, then, if Washington had been named president for life? The only thing we can say for certain is that he would have served—unhappily, to be sure—until his death on December 14, 1799, which occurred two years and nine months after he actually left office.

His successors, of course, are a matter of pure speculation. Let’s assume—just for fun—that the nation’s voters would have been asked to anoint a new leader each time a president died. That means we can use actual election results to simulate a line of succession. If a death occurred during the first half of a real-life president’s term, we’ll insert him into our hypothetical list. If it happened during the second half, we’ll opt for the winner of the following election. (Washington, for example, died less than a year before Thomas Jefferson’s victory in the election of 1800, which makes Jefferson his successor in this exercise.)

This simple procedure yields a line of 12 presidents for life:

| George Washington (1789–1799) |

| Thomas Jefferson (1799–1826) |

| John Quincy Adams (1826–1848) |

| Zachary Taylor (1848–1850) |

| Franklin Pierce (1850–1869) |

| Ulysses Grant (1869–1885) |

| Grover Cleveland (1885–1908) |

| William Howard Taft (1908–1930) |

| Herbert Hoover (1930–1964) |

| Lyndon Johnson (1964–1973) |

| Richard Nixon (1973–1994) |

| Bill Clinton (1994–present) |

I’m not going to defend all of these as plausible choices. If James Polk hadn’t served in the White House, there might not have been a Mexican War. And there’s no way that Zachary Taylor would have become president without the Mexican War. The same for Franklin Pierce. Similar historical objections can be raised to almost everybody on the list.

But this hypothetical exercise still raises an interesting point. The president-for-life system might have cost us the services of 12 of the 15 best presidents of all time, based on the ratings of 238 historians in a 2010 Siena College survey.15 You won’t find Abraham Lincoln listed in the previous chart, or Theodore Roosevelt or Franklin Roosevelt or several other highly regarded commanders in chief. But you do see 4 of the 15 whose ratings were the worst: Taylor, Pierce, Hoover, and Nixon. They would have entrenched themselves for 76 years as presidents for life, instead of the 15 years they actually spent in charge.

It seems that Paul Emery Washington had a good point. His illustrious ancestor did make the best decision.

ELECTION NO. 2: 1792

George Washington inadvertently established another political tradition in 1792. He sought reelection.

Not that he wanted to. Washington confided to a friend his dream of “leaving to other hands the helm of the state, as soon as my services could possibly with propriety be dispensed with.”16 Four years as president seemed sufficient to him.

Yet his retirement plans were dashed by the most prominent members of his cabinet. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson were constantly at each other’s throats. Hamilton desired a strong federal government and an economy powered by industry and international trade. Jefferson preferred a decentralized government and an economy based on agriculture. They agreed on only one point: Washington should remain in charge. “The confidence of the whole union is centered in you,” Jefferson flattered the president. “North and South will hang together, if they have you to hang on.”17

And so it came to pass. Washington easily won a second and final term in 1792, establishing a precedent that would endure for a century and a half. Presidents voluntarily restricted themselves to two consecutive terms until 1940, when Franklin Roosevelt successfully defied the tradition. His heresy so angered Republicans and Southern Democrats that they ratified the Twenty-second Amendment in 1951, embedding the two-term limit in the Constitution.

But a case could be made that they didn’t go far enough. Incumbent presidents often stumble badly after being reelected. Consider the litany of second-term disasters in the past 50 years alone: Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam; Richard Nixon and Watergate; Ronald Reagan and the Iran-Contra scandal; Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky; George W. Bush and the onset of the Great Recession; Barack Obama and the flawed rollout of HealthCare.gov.

Washington himself could not escape the second-term jinx. Hamilton and Jefferson escalated their political warfare after 1792, frequently trapping the president in the crossfire. Washington complained of being attacked “in such exaggerated and indecent terms as could scarcely be applied to a Nero, a notorious defaulter, or a common pickpocket.”18 The final years of his presidency were long and frustrating.

Perhaps Washington’s initial impulse in 1792 was the correct one. If he had set a one-term precedent, he would have enjoyed a longer, healthier retirement, and the nation’s political history would have been markedly different. Just imagine what the Modern Era might have been like under a policy of four years and out:

The first three elections unfold here as they did in real life. Johnson, who assumed the presidency after John Kennedy’s death, would have been allowed to run in 1964 because he had filled less than half of his predecessor’s term. The first deviation occurs in 1972, when Spiro Agnew ascends to the hypothetical presidency. His legal problems, which didn’t surface until the following year, would have quickly driven him from the White House. Vice President Gerald Ford would have stepped in for the final three years of Agnew’s term.

The gap between reality and make-believe grows wider as the list progresses. A few long-forgotten politicians are resurrected, notably Richard Schweiker (tapped to be Reagan’s running mate if the latter had actually been nominated in 1976) and James Thompson (governor of Illinois from 1977 to 1991). Bob Dole loses the 1984 election, mounts a comeback 12 years later, and loses again. And both George Bushes vanish from the scene. The elder Bush never would have made it to the White House without Reagan’s help, and the son wouldn’t have succeeded if his father hadn’t been president.

My selection of winners was based on the temper of the times. The economic boom in the 1980s would have benefited two Democrats in the alternate universe (Edward Kennedy and Gary Hart), as opposed to Reagan’s Republicans in real life. The bust in 2008 would have occurred under President John Kerry, destroying the chances of fellow Democrat Hillary Clinton instead of the actual victim, Republican John McCain. (You think the nation’s economic history would have been greatly different under a new set of leaders? Think again. Presidents don’t influence the economy nearly as much as you think they do.)

We could argue these points all day. There are, after all, no correct answers. But it’s interesting to speculate on the ramifications of a seemingly inconsequential election that took place more than two centuries ago. If George Washington had gotten his way in 1792, Mike Huckabee could very well be sitting in the Oval Office today.

ELECTION NO. 3: 1796

The presidential election of 1796 was the first to be fiercely contested. It was also the first to reveal the flaws inherent in the double-ballot system.

John Adams assumed that his two terms as vice president had earned him the status of front-runner. “I am heir apparent, you know, and a succession is soon to take place,” he confidently wrote to his wife as the year began.19 But the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, vowed to prevent his elevation, as did one of the leaders of Adams’s own Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton.

The vice president and the former secretary of the treasury possessed similar political beliefs, yet had never been friends. Both men could be prickly, and both had a talent for the stinging phrase. Adams privately scorned Hamilton’s “vice, folly, and villany,”20 while Hamilton groused about the “great intrinsic defects” in Adams’s character.21 It seemed inevitable that they would clash during the campaign.

Hamilton made the first move. He encouraged several electors to cast ballots for the Federalist vice presidential candidate, Thomas Pinckney, but not for Adams. The Constitution stipulated that the individual who received the greatest number of votes in the Electoral College would be sworn in as the next president. It did not require the winner to be actively seeking the office. Hamilton hoped to consign Adams to a third term as vice president or perhaps even to an early retirement, while his ostensible running mate, Pinckney, slipped away with the top job.

Word leaked out about these political machinations, as it usually does. Adams’s supporters struck back. They urged other Federalist electors to support Adams, but not Pinckney. They sought not only to foil Hamilton’s plans but also to demonstrate his weakness within the Federalist Party.

These plots and counterplots were based on the faulty assumption that the Federalists had the election in the bag. But Jefferson ran a surprisingly strong race—finishing only three votes behind Adams—and the margin of error for both factions was smaller than expected. The resulting victim was Pinckney. He should have won the vice presidency with ease, but the counterstrike by Adams’s supporters dropped him into third place. The post went instead to Jefferson. It was the only time in American history that members of opposing tickets were elected to the nation’s two highest offices.

Party loyalties were often fuzzy during these early presidential campaigns. A Maryland elector, for instance, straddled the fence in 1796 by casting his two ballots for Adams and Jefferson, the equivalent of simultaneously supporting Barack Obama and Mitt Romney in 2012. But as many as 80 of the 138 electors appeared to have Federalist leanings, which should have allowed the Adams-Pinckney team to coast to victory— except, of course, for all of the backstabbing within the party:

| State (EV) | Federalists | Adams | Pinckney | Reductions |

| Connecticut (9) | 9 | 9 | 4 | Pinckney by 5 |

| Delaware (3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | — |

| Maryland (10) | 7 | 7 | 4 | Pinckney by 3 |

| Massachusetts (16) | 16 | 16 | 13 | Pinckney by 3 |

| New Hampshire (6) | 6 | 6 | 0 | Pinckney by 6 |

| New Jersey (7) | 7 | 7 | 7 | — |

| New York (12) | 12 | 12 | 12 | — |

| North Carolina (12) | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| Pennsylvania (15) | 2 | 1 | 2 | Adams by 1 |

| Rhode Island (4) | 4 | 4 | 0 | Pinckney by 4 |

| South Carolina (8) | 8 | 0 | 8 | Adams by 8 |

| Vermont (4) | 4 | 4 | 4 | — |

| Virginia (21) | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| Total | 80 | 71 | 59 | Adams by 9 and Pinckney by 21 |

Thomas Pinckney faded into the mists of history after his defeat in 1796. The former governor of South Carolina and ambassador to Great Britain would serve two terms as a backbencher in the House of Representatives from 1797 to 1801, but otherwise would never hold public office again.

Vice President Jefferson, on the other hand, now found himself on the fast track. Friends had expected him to be frustrated by his close defeat, yet he was remarkably calm. He knew it would have been a thankless task to follow a living legend, George Washington, as president. Patience was in order. “This is certainly not a moment to covet the helm,” Jefferson advised his allies.22 He was confident that his time would come.

ELECTION NO. 4: 1800

The election of 1800 was one of the messiest of all time, a case history of managerial incompetence and political intrigue.

The leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party deserve much of the blame. They failed to designate an elector to vote for somebody other than vice presidential nominee Aaron Burr—a costly lapse under the double-ballot system. Burr and the party’s presidential candidate, Thomas Jefferson, tied for first place in the Electoral College with 73 votes apiece. It took 36 roll calls before the House of Representatives untied the knot and declared Jefferson the winner.

But, hey, it could have been worse.

What’s usually forgotten is that the Democratic-Republicans barely squeaked past the Federalists in 1800. President John Adams ran just eight votes behind Jefferson and Burr. Adams’s partner, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (elder brother of the unfortunate Thomas Pinckney), was only one vote farther back.

Two simple changes could have obliterated the Democratic-Republicans’ tiny margin, tossing the election into chaos:

Here’s how things would have turned out in the Electoral College:

| John Adams | 69 |

| Aaron Burr | 69 |

| Thomas Jefferson | 69 |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | 69 |

The responsibility for breaking this four-way deadlock would have rested with the House. Each of its 16 state delegations would have cast a single vote. The first candidate to achieve a simple majority—nine votes—would have been elected president.

Simple enough, right? Of course not. Neither party controlled more than half of the House’s delegations. The Federalists had the edge in eight states, the Democratic-Republicans in seven. Vermont was evenly divided, with a single representative from each party.

I’m not going to pretend that I have any idea who would have won. Nobody could possibly know. But we can certainly all agree that the debate in the House would have been acrimonious, the roll calls would have been numerous, and the threat of violence would have hung in the air.

The real-life tie between Jefferson and Burr was bad enough. Six Federalist delegations, unable to stomach any association with the hated Jefferson, stood with Burr for a week. Their obstruction, coupled with ties in two delegations, limited Jefferson to eight votes, one short of the magic nine. Some of his supporters began to speak ominously about resorting to arms, and their hero wasn’t necessarily opposed. “In the event of a usurpation,” Jefferson later wrote, “I was decidedly with those who were determined not to permit it.”23

Civil war was avoided when the opposition surrendered on the 36th ballot, handing Jefferson a 10–4 victory. It was bound to happen eventually, since the Federalists had no real stake in this particular game. (Jefferson and Burr, after all, were both Democratic-Republicans.) But it’s highly doubtful that the Federalists would have capitulated if their own candidates had still been in the hunt. If our four-way hypothetical deadlock had occurred, voting might have dragged on for months, or at least until the first shots were fired.

Bloodshed, however, was narrowly avoided. The only fatality of the election of 1800 was the double-ballot system, which was buried by the Twelfth Amendment a few months before the Electoral College convened in 1804. The Federalists vainly sought to block the amendment, which mandated separate votes for the nation’s two highest offices. “They know that if it prevails,” Jefferson wrote, “neither a president or vice president can ever be made but by the fair vote of the majority of the nation, of which they are not.”24

It was a reasonable assessment. America would experience tight (and sometimes questionable) elections in the centuries to come, but would never again see a tie. And the Federalists would field candidates in the next four campaigns, but would never again elect a president of their own.

ELECTION NO. 5: 1804

Thomas Jefferson rose dramatically in his countrymen’s esteem between 1800 and 1804. He barely eked out a victory in the former year, yet he won the latter election by a landslide. His CS soared more than 15 points from a pedestrian 77.84 in 1800 to a formidable 93.05 four years later. Richard Nixon was the only president to register a bigger increase in CS (17-plus points) between his first and second victories.

Such double-digit gains are highly unusual. Consider the reelection efforts of 26 presidents who originally attained the office through the ballot box, not because of a predecessor’s death or resignation. Thirteen boosted their campaign scores the second time around, 12 suffered declines, and George Washington remained the same. Not much better, all in all, than a 50–50 split. Only seven presidents were able to increase their CS by more than three points between initial victory and reelection:

| Candidate (two wins) | First CS | Second CS | Gain |

| Richard Nixon (1968, 1972) | 78.01 | 95.25 | 17.24 |

| Thomas Jefferson (1800, 1804) | 77.84 | 93.05 | 15.21 |

| Abraham Lincoln (1860, 1864) | 78.38 | 92.17 | 13.79 |

| James Monroe (1816, 1820) | 90.10 | 96.04 | 5.94 |

| Ronald Reagan (1980, 1984) | 91.16 | 95.13 | 3.97 |

| Franklin Roosevelt (1932, 1936) | 91.94 | 95.88 | 3.94 |

| Ulysses Grant (1868, 1872) | 85.63 | 89.28 | 3.65 |

The impressive upswings shown in this chart can be attributed to a trio of factors:

A substantial improvement in CS, of course, is very good news for a presidential candidate. It’s also an excellent portent for the candidate’s party. Let’s examine the four contests that followed the reelection of each of the seven presidents, such as the 1808–1820 skein after Jefferson’s 1804 triumph and the 1976–1988 run after Nixon’s 1972 victory. If all things were equal, we might expect each side—the parties of the Magnificent Seven and their opponents—to win 14 of the 28 elections. But the former actually scored 21 victories. That’s a nifty success rate of 75 percent.

Jefferson could sense this trend in his win over Pinckney. He bragged to a French friend that he had delivered a crushing, perhaps fatal, blow to the Federalists. “The two parties which prevailed with so much violence when you were here,” Jefferson wrote, “are almost wholly melted into one.”26 It wasn’t quite true—not yet—but it soon would be.

ELECTION NO. 6: 1808

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney ran a terrible campaign against Thomas Jefferson in 1804. He carried just 2 of the 17 states, and received only 7.96 percent of the 176 votes cast in the Electoral College. The latter was the worst performance by any major-party nominee in the first 18 presidential elections, and it remains the sixth-worst to this day.

So what did the Federalist Party do in 1808? It once again chose Pinckney to be its standard-bearer.

He talk ed a good game, you have to give him that. Pinckney vowed “to show that Federalism is not extinct, and that there is in the Union a formidable party of the old Washingtonian school.”27 But he failed to deliver. He carried five states in 1808—an undeniable improvement over his previous effort—but was flattened nonetheless by another Democratic-Republican avalanche. James Madison was elected president, drawing two-and-a-half times as many electoral votes as Pinckney.

It’ s rare for any political party to grant a second chance to a defeated nominee. There have been just nine cases of a candidate securing his first major-party nomination, losing the general election, and subsequently being renominated. Four of these men won the presidency the second time around. Pinckney was among the five who lost again:

| Candidate | First nomination | CS | Second nomination | CS |

| Thomas Jefferson (DR) | 1796 (loss) | 74.00 | 1800 (win) | 77.84 |

| Charles C. Pinckney (F) | 1804 (loss) | 59.38 | 1808 (loss) | 66.03 |

| Andrew Jackson (DR) | 1824 (loss) | 69.65 | 1828 (win) | 84.82 |

| Henry Clay (NR/W) | 1832 (loss) | 62.61 | 1844 (loss) | 71.05 |

| William Henry Harrison (W) | 1836 (loss) | 64.80 | 1840 (win) | 87.90 |

| William Jennings Bryan (D)* | 1896 (loss) | 70.98 | 1900 (loss) | 69.53 |

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 1944 (loss) | 64.76 | 1948 (loss) | 69.67 |

| Adlai Stevenson (D) | 1952 (loss) | 63.90 | 1956 (loss) | 62.52 |

| Richard Nixon (R) | 1960 (loss) | 72.12 | 1968 (win) | 78.01 |

* Bryan was nominated for a third time in 1908. He lost again with a CS of68.65.

Pinckney stands out in this group in two unfortunate ways. He was the only member who also lost a general election as a vice presidential candidate (running with John Adams in 1800), and his combined CS for both races as a presidential nominee was the worst among all nine men (125.41, falling slightly behind Stevenson’s 126.42).

But what could the Federalists possibly have expected? Pinckney had served honorably as an officer in the Revolutionary War, yet he lacked experience in upper-level politics. He had never been elected to a position higher than state legislator in South Carolina. His fame stemmed from a single utterance during treaty negotiations with France in 1797. The French ruling body, the Directory, demanded a $250,000 bribe as a precondition. “No, no, not a sixpence,” Pinckney shot back.28 Those five words made him a national hero, but they were hardly sufficient to transform him into a credible candidate.

Pinckney’s potential index in 1808 was a pitiful 3.9, the second-lowest figure for any presidential nominee ever. And the average PI for both of his races (4.5) was easily the worst for any candidate who received multiple nominations. The Federalist Party’s base was shrinking rapidly during the first decade of the 19th century—largely because the rural states of the South and Midwest found its aristocratic image repulsive—and its pool of available talent was drying up. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney’s presence at the head of the Federalist ticket was proof enough of that.

ELECTION NO. 7: 1812

Present-day politicians can only dream of campaigning the way that DeWitt Clinton did in 1812.

Clinton, who was just 43 years old, had already served nearly a decade as mayor of New York City. He was a high-profile member of the Democratic-Republican Party, and could have been expected to support the reelection of President James Madison. But 1812 was a volatile year—the United States had declared war against Great Britain in June—and the ambitious Clinton had grown weary of Virginia’s stranglehold on the presidency. New York’s Democratic-Republican caucus urged him to challenge Madison in the general election, and he readily agreed.

The odds were solidly against Clinton—his potential index of 3.7 was the worst for any major-party nominee ever—but he deftly finessed his shortcomings. He simultaneously positioned himself as a peace-loving Federalist in the East (where public sentiment ran strongly against the War of 1812) and as a militant Democratic-Republican in the South and Midwest (where desire was intense for a military victory).

This two-pronged strategy required semantic flexibility. Clinton played upon New England’s discontent with a blunt slogan: “Madison and War! Or Clinton and Peace!”29 Yet he adopted a belligerent tone below the Mason-Dixon Line and beyond the Appalachians. Pamphlets distributed in those areas promised that the war “shall be prosecuted till every object shall be attained for which we fight.”30

If a candidate dared to be so wildly inconsistent in today’s mediasaturated society, his campaign would quickly disintegrate. Clinton might have met a similar fate in 1812 if Madison had called his bluff. But the president stayed above the fray. “No one, however intimate, ever heard him open his lips or say one word on the subject,” noted Charles Ingersoll, a prominent Pennsylvania lawyer and politician.31

Madison’s passivity allowed Clinton to make considerable headway in the East, where he delivered the Federalist Party’s strongest performance in a dozen years. The challenger carried seven Eastern states and won more than two-thirds of the region’s electoral votes:

| Year | Federalist nominee | East SC | East EV | East EV% |

| 8100 | John Adams | 8 | 61 | 70.93% |

| 1804 | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | 2 | 14 | 13.21% |

| 1808 | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | 5 | 44 | 41.51% |

| 1812 | DeWitt Clinton | 7 | 89 | 69.53% |

Victory in Virginia or any two of the South’s other major states—Kentucky, North Carolina, and South Carolina—would have vaulted Clinton past the threshold of 109 electoral votes, making him the fifth president of the United States. But the second half of his strategy was massively ineffective. Clinton lost every single Southern state, as well as the sole Midwestern state of Ohio. Bellicose electors saw no reason to replace a wartime president with a me-too opponent. The Electoral College reelected Madison by a margin of 39 votes.

Yet Clinton had reason to be optimistic. He had been proven to be a shrewd campaigner. His return on potential—192 points—remains the highest ROP for any major-party nominee who lost a general election. And, of course, he was young. Who could doubt that he would run for president again?

But he never did. Clinton stepped up to the governorship of New York in 1817, holding the job for all but two years until his death in 1828. The energy he once channeled into national politics was now directed toward construction of the Erie Canal. Critics derided the massive project as “Clinton’s Ditch,” but its overwhelming success would cement New York’s commercial supremacy in the decades to come.

ELECTION NO. 8: 1816

It took slightly more than a generation for the Federalist Party to plummet from omnipotence to impotence.

The party seemed invincible in its early years. George Washington may have pretended to be nonpartisan, but his Federalist leanings were obvious to everybody. He served as the father figure of the movement—wise, powerful, and almost godlike—while the cunning Alexander Hamilton functioned as its master strategist. They made a potent team.

The Federalists won the first three presidential elections, and came close to taking the fourth. There was no reason to anticipate the party’s demise, yet it unraveled with amazing speed after John Adams’s defeat in 1800:

| Federalist nominees | Average PI | SC% | EV% | Average CS |

| Washington-Adams (1789–1800) | 7.1 | 74% | 71% | 85.71 |

| Pinckney-Clinton-King (1804–1816) | 5.0 | 24% | 23% | 64.65 |

What happened? Washington died in 1799, and Hamilton was killed five years later in an infamous duel with Aaron Burr. The men who picked up the Federalist standard were not equal to the task, as indicated by the absurdly low PIs for the party’s last four nominees. Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican heirs lashed the Federalist Party as a tool of the rich and privileged, a politically effective accusation that was not without merit. Federalist candidates never came up with a compelling retort.

The War of 1812 accelerated the party’s decline. Hard-line Federalists in New England were violently opposed to taking up arms against Great Britain. Some began to advocate secession, signaling an amazing reversal of political philosophies. The Democratic-Republicans now emerged as the party of strong nationalist spirit, while the Federalists degenerated into a weak organization with little appeal outside the East. “Our two great parties have crossed over the valley and taken possession of each other’s mountain,” John Adams wrote unhappily.32

It fell to Rufus King, a senator from New York, to lay the Federalist Party to rest. He undertook the 1816 campaign against James Monroe with no hope of success. “Federalists of our age,” he told a friend, “must be content with the past.”33 Monroe easily won the presidency, the fifth straight victory for the Democratic-Republicans.

King carried only three states, compared to Monroe’s 16, and the longterm trends were equally divergent. Federalist nominees had won just 17 states and 184 electoral votes since 1804. The corresponding figures for the Democratic-Republicans were 54 states and 595 electoral votes. Monroe fervently hoped the Federalists would bow to reality and fade away. “Existence of parties is not necessary to free government,” the new president sniffed.34 The Federalists obliged, never again mounting a national campaign.

ELECTION NO. 9: 1820

The strange thing about the election of 1820 is that nobody opposed James Monroe’s pursuit of a second term.

The economy was in disastrous shape. The nation’s first depression, the Panic of 1819, had struck the previous year and would linger into 1823. A member of Monroe’s cabinet, Secretary of War John Calhoun, acknowledged in 1820 that there had been “an immense revolution of fortunes in every part of the Union, enormous numbers of persons utterly ruined, multitudes in deep distress.”35

Political discord had intensified. The potential admission of Missouri as a slave state had turned North against South. “It is a most unhappy question awakening sectional feelings, and exasperating them to the highest degree,” said Henry Clay, the speaker of the House. “The words civil war and disunion are uttered almost without emotion.”36 Clay helped steer the Missouri Compromise through Congress in 1820, temporarily defusing the controversy. Yet it was clear that slavery was far from a settled issue.

Monroe’s method of dealing with these serious problems was to ignore them. His annual message at the end of 1819 grudgingly acknowledged that “a derangement has been felt in some of our moneyed institutions.” His report a year later—a time of maximum suffering across the country—was relentlessly upbeat. “I see much cause,” Monroe wrote, “to rejoice in the felicity of our situation.”37 The deep divisions revealed by the Missouri dispute were brushed aside with equal ease. The president predicted in his 1821 inaugural address that “our system will soon attain the highest degree of perfection of which human institutions are capable.”38

Monroe was able to ignore reality because the Federalist Party had vanished, other potential challengers had already set their sights on 1824, and his warm personality had won friends in every political faction. The complete lack of opposition in 1820 inspired historians to label the middle years of the Monroe administration “the Era of Good Feelings.”

A better name might have been “the Era of Apathy.” The Democratic-Republican Party scheduled a caucus in April 1820 to formally renominate Monroe, but so few members of Congress attended that the vote was delayed and later canceled. The party never tendered the president its official endorsement, not that it mattered. Nobody else entered the race, and Monroe received all but one of the Electoral College’s 232 votes.

The lone holdout, William Plumer of New Hampshire, supposedly wished to reserve the honor of unanimity for George Washington. That, at least, is the legend. The truth is that Plumer, a former Federalist, believed Monroe had done a miserable job, especially with the economy. The president, Plumer insisted, “had not that weight of character which his office requires.”39 It was a rare discordant note in an unusually lifeless election.

ELECTION NO. 10: 1824

Athletes have a special term for any victory that can be attributed to sloppy play by opponents, bad calls by officials, and/or outright luck. They talk about “winning ugly.”

John Quincy Adams won ugly in 1824. His performance was undeniably the worst by any victorious candidate in the history of presidential politics. Consider these four indicators:

So how did Adams manage to win the presidency? He played the game according to the rules of the Elite Era—a strategy that would have doomed him to failure in 1828 or anytime thereafter, but proved to be sufficient (just barely) in 1824.

Friends and foes agreed that Adams lacked the common touch, and he willingly conceded the point. “I am a man of reserved, cold, austere, and forbidding manners,” he wrote in his diary.40 But the absence of popular appeal had not been a significant factor prior to 1824. There was no need to curry the favor of everyday Americans, since they had little or no say in the election of the president. It was more important to secure the support of the upper crust, and that was something Adams had always been able to do.

Positioning was the key. The first three presidents elected in the 19th century—Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—had previously served as secretary of state, using that job as a stepping stone to the White House. President Monroe had bestowed the coveted post upon Adams in 1817 in recognition of his diligence and intelligence. The new secretary was aware—everybody was aware—that he now stood next in line for the presidency. “He wanted it to come to him in good time, unsolicited, a reward for distinguished and patriotic public service,” wrote historian Samuel Flagg Bemis.41

It would not be that easy. The rough-hewn Jackson never had any hope of gaining the support of the rich and powerful in 1824. His presidential candidacy initially seemed so innocuous that Adams joked about choosing Jackson as a running mate. “It will afford an easy and dignified retirement to his old age,” the secretary of state chuckled.42 But the rise of popular voting presaged the end of the Elite Era. Farmers and workingmen found Jackson to be an unusually attractive candidate, giving him a strong lead in the PV column. He was something new in American politics, a candidate who drew his strength directly from the people, not from the aristocracy.

Yet Adams still held the advantage. Leaders, not common men, would once again pick the president. Persuasion and deal-making were the necessary elements for victory in the House of Representatives. Adams was a seasoned diplomat, a man who knew how to manipulate the levers of power. The situation was tailor-made for somebody with his abilities.

The Twelfth Amendment stipulated that the House must choose one of the Electoral College’s top three vote-getters: Jackson, Adams, or William Crawford. The roll call was conducted by the influential speaker of the House, Henry Clay, who had finished fourth in the presidential race. He sealed the verdict by throwing his support to Adams—one elite politician determining the fate of another. It may not have been an ideal example of democracy in action, but the Founders definitely would have approved.

The president-elect understood what was expected in return. Adams named Clay his secretary of state, elevating his benefactor to first place in the informal line of succession. “That there was an implicit, unspoken bargain is quite obvious,” Bemis conceded.43 But Jackson took a much darker view. “So you see,” he sputtered, “the Judas of the West has closed the contract and will receive the 30 pieces of silver.”44 Jackson’s supporters would sing their refrain of “corrupt bargain” for the next four years, as their hero plotted his revenge.

ELECTION NO. 11: 1828

John Quincy Adams possessed the advantage of incumbency, yet his rematch with Andrew Jackson was doomed from the very start. Four key factors were at play in 1828, and all four favored the challenger.

The first (and most important) was the growing acceptance of popular voting. Eighteen of the 24 states had allowed white males to cast presidential ballots in 1824, and Georgia, Louisiana, New York, and Vermont now joined them. (The holdouts were Delaware and South Carolina. The latter refused to let its residents vote in national elections until 1868, relenting only under the compulsion of federal troops.)

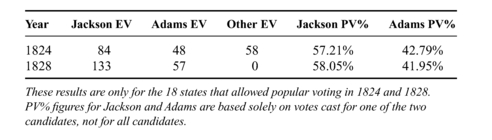

The four newcomers had given Adams a sizable majority of their electoral votes in 1824, when the ruling class had still called the shots. Jackson’s poor performance in those states—especially New York—had left him 32 votes short of victory in the Electoral College. But the switch to popular voting turned the tide in 1828. Jackson picked up an additional 30 electors from the four states, nearly wiping out his deficit from the previous election:

Let’s turn now to the 18 states that had previous experience with popular voting. A first glance suggests that they were remarkably stable. Fifty-eight percent of their voters opted for Jackson in 1828, essentially mirroring the split between Jackson and Adams four years earlier.

But the absence of other competitors—the second key factor in 1828— made all the difference. William Crawford and Henry Clay had siphoned a total of 58 electoral votes from the 18 states in 1824. Virtually all of those votes migrated to Jackson in the second race, paving the way for a landslide victory in the Electoral College:

Contemporary politicians could sense these trends, and they wasted no time in choosing sides for the rematch, a third factor that worked against the president. Jackson had run as the antiestablishment candidate in 1824, but he now welcomed influential supporters. Adams’s vice president, John Calhoun, sensed that his path to the White House was blocked by Secretary of State Henry Clay, the beneficiary of the infamous “corrupt bargain.” So Calhoun threw in with Jackson, agreeing to remain as his vice president. New York’s powerful Democratic-Republican leader, Senator Martin Van Buren, also climbed aboard the Jackson bandwagon. He was destined to replace Clay as secretary of state.

Adams might have overcome these defections if he had been willing to fight back. Presidents have potent tools at their command, such as patronage, prestige, and publicity. Adams’s refusal to use them was the final factor that sealed his defeat. “I write no letters upon what is called politics—that is electioneering,” he sniffed.45 Jackson and the Democratic-Republicans were staging parades and barbecues to recruit voters. But Adams (whose supporters now called themselves National Republicans) declined to follow suit. The president liked to quote Macbeth: “If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me, without my stir.”46

Presidential politics hasn’t worked that way since the days of George Washington, and the advent of popular voting guaranteed that it never would. Jackson, an energetic man of the people, easily defeated Adams, a placid descendant of the nation’s founding aristocracy. Such an outcome would have been unthinkable a decade earlier. No other result could be imagined from that point forward.

ELECTION NO. 12: 1832

America reached a milestone in 1832. Both major-party nominees hailed from west of the Appalachians—Andrew Jackson from Tennessee and Henry Clay from Kentucky—making this the first campaign without a significant contender from the Atlantic Seaboard.

Every nominee from 1789 through 1820 lived in one of the 13 original states. Jackson broke this monopoly in 1824, narrowly losing the presidency to John Quincy Adams before winning their 1828 rematch with ease. He now faced Clay, a fellow politician from the nation’s interior. (It was a sweet prospect for Jackson. He had already defeated Adams, a participant in the infamous “corrupt bargain” that decided the 1824 election, and would soon do the same to Clay, the other party to the deal.)

Both candidates spent their adolescence in original states, leaving at age 20 to join the growing migration across the mountains. Jackson was born in North or South Carolina—nobody knows which—and moved to the territory that would become Tennessee. Clay grew up near Richmond, Virginia, and relocated to Kentucky.

Their joint ascension brought an end to the seaboard’ s dominance of presidential politics. Twenty years would pass before another pair of nominees emerged from the first 13 states in the same election (Franklin Pierce and Winfield Scott in 1852), and it would happen just five times after that:

| Year | Major-party nominees and election result |

| 1852 | Franklin Pierce (D-New Hampshire) over Winfield Scott (W-New Jersey) |

| 1884 | Grover Cleveland (D-New York) over James Blaine (R-Maine) |

| 1904 | Theodore Roosevelt (R-New York) over Alton Parker (D-New York) |

| 1916 | Woodrow Wilson (D-New Jersey) over Charles Evans Hughes (R-New York) |

| 1940 | Franklin Roosevelt (D-New York) over Wendell Willkie (R-New York) |

| 1944 | Franklin Roosevelt (D-New York) over Thomas Dewey (R-New York) |

Three of these races in volved men who reversed the traditional American pattern by trekking east, not west. Blaine spent his early years in Pennsylvania and Kentucky before moving to Maine. (Yes, I know Maine was not an original state. It was, however, part of Massachusetts when the Declaration of Independence was signed, so I’m including it here.) Indianaborn Willkie and Michigan native Dewey were both attracted by the bright lights and big opportunities in New York City.

The list of trans-Appalachian presidential candidates was also augmented by migration, albeit the traditional east-to-west kind. The first eight men who were nominated from the interior had all been born in original states:

| Candidate | Years nominated | State represented (state of birth) |

| Andrew Jackson | 1824, 1828, 1832 | Tennessee (North or South Carolina) |

| Henry Clay | 1832, 1844 | Kentucky (Virginia) |

| Hugh White | 1836 | Tennessee (North Carolina) |

| William Henry Harrison | 1836, 1840 | Ohio (Virginia) |

| James Polk | 1844 | Tennessee (North Carolina) |

| Lewis Cass | 1848 | Michigan (New Hampshire) |

| Zachary Taylor | 1848 | Louisiana (Virginia) |

| John Fremont | 1856 | California (Georgia) |

This pattern was finally broken in 1860. All three major-party nominees in that violent year not only represented states beyond the Appalachians but also had been born outside the original 13.

John Breckinridge still lived in the state of his birth, Kentucky, a rare distinction in that transient age. Stephen Douglas had departed his native Vermont at age 20 to “become a Western man,” as he told the family he left behind in New England.47 Douglas found a congenial home in Illinois, as did Abraham Lincoln, whose journey from his Kentucky birthplace is known to all.

The nation’s center of political gravity inevitably moved westward as settlers pushed beyond the Mississippi River, but the rulers of coastal states did not adjust easily. They vented their displeasure whenever a presidential candidate rose from the Midwest or interior South.

John Quincy Adams spoke for his fellow elites in dismissing Jackson as “a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his own name.”48 The same attitude prevailed as late as 1860, when the New York Herald expressed shock at the Republican Party’s nomination of Lincoln, “a fourth-rate lecturer who cannot speak good grammar.” Everything about the candidate fell short of the paper’s refined Eastern standards, even his renowned wit. The Herald’s editorial groused about Lincoln’s “coarse and clumsy jokes.”49

Complaining could not change reality. Andrew Jackson’s victories in 1828 and 1832 signaled a permanent change in the nation’s political geography. Candidates from the original 13 states swept the first 10 presidential elections, but they would win only 3 of the 14 races from 1828 to 1880. Power most definitely had shifted inland.

ELECTION NO. 13: 1836

Regional parties are political fixtures in several countries. Prominent examples include the Bloc Quebecois in Canada, the Basque Nationalist Party in Spain, the New Flemish Alliance in Belgium, and Great Britain’s Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru. Each of these parties speaks nationally on behalf of an isolated section of its country.

Plaid Cymru, for example, seeks the economic revitalization of Wales, followed by its eventual independence from Britain. “Wales has its own history, its own unique language, and is a distinct geographic entity,” says Leanne Wood, the party’s leader. “To me, it makes sense for it to be a political unit.”50

Success doesn’t come easily—if at all—for most regional parties, so persistence is a necessary quality. Plaid Cymru was founded in 1925, but didn’t win its first seat in the House of Commons until 1966.51 Its influence has barely increased since then, as shown by its unimpressive haul of three seats in Great Britain’s 2015 election. Yet Wood remains publicly optimistic that the party will attain its ultimate goal. “I think, to be honest, eventually it’s inevitable,” she says of Welsh independence. “People will arrive at the conclusion that we can only really prosper if we do things for ourselves.”52

The United States is a vast nation of conflicting geographic sections and demographic groups, yet regional parties have never made headway here. The few attempts have lacked the resilience and optimism of Plaid Cymru and its European and Canadian counterparts. White Southerners cobbled together a pair of makeshift organizations—the Southern Democratic Party in 1860 and the States’ Rights Democratic Party in 1948— but neither survived its first defeat. The Populist Party was created in the 1890s to defend the interests of rural America, yet it was quickly absorbed by the Democrats. Other minor parties—even white supremacist George Wallace’s American Independent Party in 1968—aspired to national, not regional, success.

But things might have been different if the Whigs, the successors to the National Republicans, had won the presidency in 1836.

The Whig Party was a strange stew of disparate political ingredients— foes of Andrew Jackson, supporters of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, ex-Federalists, businessmen, refugees from the Anti-Masonic Party, abolitionists, and defenders of slavery. “We must run but one candidate lest we break up and divide,” said John Crittenden, a senator from Kentucky.53 But it was not easily done. The National Intelligencer, a Washington newspaper friendly to the Whigs, could see no way to fuse the various elements of the party. “We desire a candidate who will concentrate all our suffrage,” wrote the paper, “and we desire what is impossible.”54

The solution was to field a team of candidates against Vice President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s personal choice as the Democratic nominee in 1836. The Whigs essentially divided themselves into three regional parties. A pair of senators, Hugh White of Tennessee and Webster of Massachusetts, would run campaigns in the South and New England, respectively. A former general and senator, William Henry Harrison, would cover the rest of the North. If each could somehow manage to carry his designated territory, Van Buren might be blocked in the Electoral College. The next president would be chosen by the House of Representatives.

It was a harebrained scheme, a tacit admission by the Whigs of their lack of cohesion. Jackson’s allies controlled 14 of the 26 delegations in the House, virtually assuring Van Buren of victory there. The Whigs could succeed only if White, Webster, and Harrison all drew more electoral votes than Van Buren, thereby becoming the three candidates in the House’s pool. The odds against that eventuality were astronomical. “No opposition man can be elected president,” grumbled Willie Person Mangum, a Whig senator from North Carolina.55 He wasn’t alone in his disillusionment.

Van Buren short-circuited the Whigs’ elaborate plans by winning a comfortable majority in the Electoral College, sparing the House from any involvement. The vice president had expected White to be his toughest opponent, but Harrison emerged as the star of the Whigs’ team. He carried seven states, compared to only two for White and one apiece for Webster and noncandidate Mangum. It was clear in retrospect that the party should have run Harrison as its sole candidate. The Whigs would never adopt a regional strategy again—nor would any other major party.

Yet it’s true that politicians imitate success. If the Whigs had somehow made their scheme work in 1836, regional teams might have become common in presidential politics.

Imagine if the Republicans had confronted Barack Obama with four opponents in 2012—Mitt Romney in the East and Mormon-dominated states of the West, Newt Gingrich in the South, Rick Santorum in the Midwest and interior West, and Jon Huntsman in the Pacific states. If this foursome had managed to deadlock the Electoral College, the final choice would have fallen to the House, where the Republicans controlled 31 of the 50 delegations. An orgy of speculation and deal-making would have ensued, with Democrats desperately trying to peel away the votes of moderate Republicans, and various factions bitterly struggling for supremacy within the Republican Party. Roll calls might have dragged on for weeks. The Florida controversy of 2000 would have seemed tame by comparison.

How would this dark scenario have ended? Who possibly could have won the presidency? How much damage would have been done to our political system? Martin Van Buren’s decisive victory in 1836 spared us the agony of finding out.