The Progressive Era, as it is typically defined, lacked the chronological precision of a war. It did not begin with a fusillade upon Fort Sumter, nor did it conclude with the finality of Appomattox. It could best be described as a vague, amorphous movement that slowly emerged during the final years of the Gilded Age, waxed and waned for a couple of decades, and withered away after World War I.

Historians—dri ven by a professional compulsion to assign dates to all epochs, generations, and intervals—generally fix the Progressive Era from the 1890s to the 1920s, give or take a few years. This period was characterized by the vigorous trust-busting of Theodore Roosevelt, the cerebral reforms of Woodrow Wilson, and the fiery rhetoric of Robert La Follette. These three men, so different in style and temperament, nonetheless pursued the same goals—the streamlining of government operations, elimination of political corruption, regulation of massive corporations, and general improvement of conditions for the middle and working classes. “I’m radical, but not too darned radical,” La Follette thundered. “Just enough to make the farmers and the laborers high-paid people.” 1

Few researchers, if any, are likely to agree with the years cited in the title of this chapter. The span from 1912 to 1956 excludes Roosevelt’s presidency and extends as far as the two electoral victories of Dwight Eisenhower, who was rarely accused of progressive leanings. (The founder of the ultra-right-wing John Birch Society, Robert Welch, was one of the few who considered Ike to be a closet leftist.2 Welch insisted that Eisenhower was a communist, and he assured fellow conservative Barry Goldwater he could prove it. “The hell you can,” Goldwater shot back.)

So what’s the explanation for the disparity in dates?

Historians are concerned with the gamut of progressive reforms, some of which were indeed rooted in the 1890s. But my focus is solely on presidential politics, where the era’s three relevant actions came much later:

These progressive innovations had scant immediate impact, though they would eventually change the American political process in significant ways. The first presidential primaries allowed voters to express their preferences, yet party bosses still chose the nominees. Newly elected senators initially lacked the seniority to wield any significant clout. And women, who had been expected to liberalize the electorate, voted overwhelmingly for conservative Warren Harding in 1920.

It would take four decades for these reforms to reach maturity, which is why my version of the Progressive Era stretches into the Eisenhower years. The unlikely herald of the political system spawned by these alterations was Estes Kefauver, a senator from Tennessee who sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952 and 1956, failing both times.

What’s important about Kefauver is how he emerged, not how he was defeated. He ran for the Senate in 1948 against the handpicked candidate of Edward Crump, the boss of Tennessee’s Democratic Party. Crump insinuated that Kefauver was doing the work of “pinkos and communists” with the sneakiness of a raccoon. “I may be a pet coon, but I ain’t Mr. Crump’s pet coon,” Kefauver retorted.5 He donned a coonskin cap at campaign appearances and scored a surprising win over the Crump machine, a victory that would have been impossible without the Seventeenth Amendment.

Kefauver gained national fame three years later by undertaking an extensive probe of organized crime. The hearings conducted by his committee drew enormous audiences on television. The senator was emboldened to seek the presidency, even though Crump’s fellow bosses opposed him at every turn. “The boys in the smoke-filled rooms have never taken very well to me,” Kefauver said in classic understatement.6 He hit on the novel idea of using the primaries to demonstrate his popular appeal, piling up 21 victories in 1952 and 1956. The party’s leaders, however, retained enough power to prevent his nomination.

Yet the ingredients for future success had been demonstrated—election to the Senate, telegenic appeal, success in the primaries. John Kennedy and other young politicians grasped Kefauver’s significance, even if their elders did not.

The following chart offers a rundown of the Progressive Era’s major-party nominees, with each year’s winner listed first. (If you need an explanation of this chart or the others ahead, you’ll find it in Chapter 2.)

| Election | Candidate | PV% | EV | CS |

| 1912 | Woodrow Wilson (D) | 41.84% | 435 | 86.26 |

| William Howard Taft (R) | 23.18% | 8 | 55.09 | |

| 1916 | Woodrow Wilson (D) | 49.24% | 277 | 78.07 |

| Charles Evans Hughes (R) | 46.11% | 254 | 73.55 | |

| 1920 | Warren Harding (R) | 60.34% | 404 | 88.37 |

| James Cox (D) | 34.12% | 127 | 64.01 | |

| 1924 | Calvin Coolidge (R) | 54.04% | 382 | 85.63 |

| John Davis (D) | 28.82% | 136 | 63.46 | |

| 1928 | Herbert Hoover (R) | 58.24% | 444 | 90.41 |

| Alfred Smith (D) | 40.77% | 87 | 63.06 | |

| 1932 | Franklin Roosevelt (D) | 57.41% | 472 | 91.94 |

| Herbert Hoover (R) | 39.65% | 59 | 61.28 | |

| 1936 | Franklin Roosevelt (D) | 60.80% | 523 | 95.88 |

| Alfred Landon (R) | 36.54% | 8 | 57.76 | |

| 1940 | Franklin Roosevelt (D) | 54.69% | 449 | 89.94 |

| Wendell Willkie (R) | 44.83% | 82 | 63.60 | |

| 1944 | Franklin Roosevelt (D) | 53.39% | 432 | 88.61 |

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 45.89% | 99 | 64.76 | |

| 1948 | Harry Truman (D) | 49.51% | 303 | 79.72 |

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 45.12% | 189 | 69.67 | |

| 1952 | Dwight Eisenhower (R) | 54.88% | 442 | 89.56 |

| Adlai Stevenson (D) | 44.38% | 89 | 63.90 | |

| 1956 | Dwight Eisenhower (R) | 57.38% | 457 | 91.03 |

| Adlai Stevenson (D) | 41.95% | 73 | 62.52 | |

Franklin Roosevelt, of course, was the dominant figure of this or any other period of American political history. He set records that will never be topped, including the most general-election triumphs by a presidential candidate (four), largest number of electoral votes in a career (1,876), and highest cumulative campaign score (366.37). One of his foes, Wendell Willkie, nicknamed FDR “the Champ,” and with good reason.

Two other presidential candidates won consecutive terms during the Progressive Era—Wilson at the very beginning and Eisenhower at the very end. Democrats took seven elections in all, Republicans the other five. Three versions of the Progressive Party popped up in these years, headed by Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, La Follette in 1924, and Henry Wallace in 1948. All three—in the ultimate irony—lost badly.

ELECTION NO. 32: 1912

Theodore Roosevelt was just 50 years old—a vigorous 50—when he voluntarily left the White House in March 1909. He anticipated an easy transition to political retirement, or so he said. His friends were dubious.

“The real problem that confronts you is whether you can be a sage at 50,” the president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, told TR. “If you can, your permanent reputation seems to me certain. If you cannot, then the outlook is different.”7

But fidgeting on the sidelines was not Roosevelt’s style. He inevitably jumped into the race for the Republican nomination in 1912, challenging William Howard Taft, whom he had anointed as president four years earlier. An ugly campaign ensued. Roosevelt ridiculed Taft as a “fathead” and a “puzzlewit.” Taft, employing a broader vocabulary, characterized Roosevelt as a “dangerous egotist” and a “demagogue.”8

Roosevelt clearly was more popular with rank-and-file voters. This was the first presidential campaign to feature primary elections, and TR won 9 of 12 on the Republican side. But Taft had firm control of the party machinery. “I am in this fight,” he pledged, “to perform a great public duty, the duty of keeping Theodore Roosevelt out of the White House.”9 And he was as good as his word, winning renomination at the Republican convention.

Roosevelt shifted gears without a moment’s hesitation, slapping together a new Progressive Party and agreeing to run as its nominee. “We stand at Armageddon,” he shouted to his supporters, “and we battle for the Lord!”10 This classic bit of Rooseveltian rhetoric obscured his real (and more mundane) goal—reclaiming his old job.

He couldn’t swing it. No minor-party candidate—not even the great Theodore Roosevelt—has ever been able to win a presidential election. But TR clearly ran the best campaign of any of them. His 88 electoral votes made him the runner-up to Woodrow Wilson. Taft, with only eight EVs, was light-years behind.

Twelve minor-party candidates have managed to post campaign scores higher than 30, but only one—you know who—was able to surpass 50:

| Minor-party candidate | PV% | EV% | CS |

| Theodore Roosevelt (P-1912) | 27.39% | 16.57% | 66.37 |

| John Bell (CU-1860) | 12.61% | 12.87% | 46.37 |

| Robert La Follette (P-1924) | 16.59% | 2.45% | 46.37 |

| George Wallace (AI-1968) | 13.53% | 8.55% | 45.41 |

| Millard Fillmore (AW-1856) | 21.53% | 2.70% | 45.15 |

| Ross Perot (I-1992) | 18.91% | 0.00% | 43.78 |

| Martin Van Buren (FS-1848) | 10.12% | 0.00% | 42.02 |

| John Anderson (NU-1980) | 6.61% | 0.00% | 38.97 |

| James Weaver (POP-1892) | 8.53% | 4.96% | 38.80 |

| Ross Perot (REF-1996) | 8.40% | 0.00% | 36.87 |

| William Wirt (AM-1832) | 7.78% | 2.45% | 35.63 |

| Strom Thurmond (SRD-1948) | 2.40% | 7.35% | 34.75 |

His relative success as a third-party candidate invites a question: How might TR have fared if he had triumphed over Taft at the convention? “Had Roosevelt won the Republican nomination and not formed a third party, he would almost surely have become president of the United States,” insisted James Chace, author of a book about the 1912 election.11 Wilson conceded that Roosevelt would have had an edge with the voters in a head-to-head matchup. “He is a real, vivid person, whom they have seen and shouted themselves hoarse over and voted for, millions strong,” Wilson said. “I am a vague, conjectural personality, more made up of opinions and academic prepossessions than of human traits and red corpuscles.”12

It’ s interesting to speculate about a Roosevelt-Wilson race, yet it’s not the easiest contest to simulate, given the complete absence of polling data from 1912. The best we can do is make a few educated guesses and reallocate the votes accordingly.

Our first (albeit simplistic) scenario consolidates the support received by the two lifelong Republicans in the actual election. If Roosevelt had been nominated and all of Taft’s loyalists had gotten behind him, here’s what would have happened:

| Candidate | SC | PV | PV% | EV |

| Theodore Roosevelt (R) | 34 | 7,606,550 | 50.57% | 379 |

| Woodrow Wilson (D) | 14 | 6,294,327 | 41.84% | 152 |

This, you’ll have to admit, is an unlikely outcome. Taft’s supporters could not easily have forgiven Roosevelt’s “fathead” crack. Few would have crossed over to the Democrats—the ideological gap between Taft and Wilson was more like a chasm—but many would have remained on the sidelines. How many? Let’s reduce Taft’s state-by-state count by 20 percent before adding it to Roosevelt’s total:

| Candidate | SC | PV | PV% | EV |

| Theodore Roosevelt (R) | 31 | 6,909,264 | 48.16% | 350 |

| Woodrow Wilson (D) | 17 | 6,294,327 | 43.88% | 181 |

Wilson picks up Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri under this scenario, but the result is essentially unchanged. It’s still a landslide.

There is another possibility to consider. Roosevelt could have shifted to the right during the fall campaign to woo recalcitrant Taft supporters, but such a move probably would have triggered a revolt by the Republican Party’ s progressive wing. (There was such a thing back then.) Robert La Follette, who had run in the Republican primaries, was no fan of Roosevelt. It’s easy to envision him joining the race at the head of his own Progressive Party, a step he would actually take in 1924.

This third scenario is a bit complicated, requiring these four moves:

Here’s how everything works out:

| Candidate | SC | PV | PV% | EV |

| Theodore Roosevelt (R) | 29 | 6,356,073 | 43.26% | 324 |

| Woodrow Wilson (D) | 18 | 5,800,783 | 39.48% | 194 |

| Robert La Follette (P) | 1 | 1,415,091 | 9.63% | 13 |

There’s no need to go further. All three simulations suggest that Roosevelt would have defeated Wilson with ease, and historians tend to agree. If, on the other hand, Taft had faced Wilson in a two-man race, the election almost certainly would have been tighter, but the incumbent still would have had the nation’s dominant party behind him. The Republicans had won 11 of the previous 13 presidential contests, and there was no reason why the streak couldn’t have continued in 1912.

No reason except a feud that was one of the bitterest in the history of American politics.

ELECTION NO. 33: 1916

Woodrow Wilson appeared to be nicely positioned for reelection in 1916. Popularity ratings were unavailable—scientific public-opinion polls were two decades in the future—yet it was obvious that a majority of Americans liked Wilson. He had steered clear of World War I, a policy still applauded by most voters. His campaign slogan—“He Kept Us Out of War”—would prove to be remarkably effective.

Nor was there any doubt that the Democratic Party was solidly behind the president. Wilson received 98.78 percent of the votes cast in the 20 Democratic primaries, which remains the highest percentage of primary votes received by a candidate in a given year. The Democratic convention renominated him without opposition.

The best news of all came from the one prospective foe Wilson truly feared. Theodore Roosevelt decided not to run for president as either a Republican or a Progressive. “The people as a whole are heartily tired of me and of my views,” he said wearily.13 TR was only 58, yet he suddenly seemed old and feeble. His vitality had been sapped by a tropical fever during a jungle expedition in Brazil two years earlier. He would be dead by 1919.

Democrats were tempted to believe that the path was clear for Wilson, but the harsh truth was that America was still a Republican nation. Republican candidates had won all but three presidential elections since 1860. No Democrat had won consecutive terms in the White House since Andrew Jackson in 1832. Wilson had attained the office only because of the disastrous split in Republican ranks in 1912, a fracture that began to heal after Roosevelt’s decision not to run again.

The Republican nominee, Charles Evans Hughes, battled Wilson to a virtual draw. The New York Times declared Hughes to be the winner on election night, but the putative president-elect was cautious. “Wait till the Democrats concede my election,” he said. “The newspapers might take it back.”14 That they did after the final votes trickled in from the Midwest and West.

Wilson’s margin of victory was 23 electoral votes. A flip of any of nine states—each with at least 12 EVs—would have tipped the election to Hughes. The tightest was California, where Republicans would have succeeded if they had converted 1,711 Wilson supporters, just 0.17 percent of the 999,250 votes cast in that state. No other presidential election between 1892 and 1972 could have been reversed by the flip of a single state.

A broader hypothetical example demonstrates the tenuous nature of Wilson’s victory. A flip of 85,760 votes—a mere 0.46 percent of the national total—would have converted an extremely tight election into a 342–189 landslide for Hughes:

| State | EV | Flip from Wilson to Hughes |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 29 |

| North Dakota | 5 | 868 |

| New Mexico | 3 | 1,299 |

| California | 13 | 1,711 |

| Nevada | 3 | 2,825 |

| Wyoming | 3 | 3,340 |

| Arizona | 3 | 6,325 |

| Idaho | 4 | 7,344 |

| Washington | 7 | 8,091 |

| Maryland | 8 | 10,507 |

| Kentucky | 13 | 14,069 |

| Missouri | 18 | 14,347 |

| Utah | 4 | 15,005 |

Hughes, to be blunt, was an uncompelling candidate. His personality was so austere that Roosevelt dismissed him a “bearded iceberg.”15 His loss of California was generally attributed to his poor handling of that state’s irascible governor, Hiram Johnson. Wilson joked in the latter stages of the campaign that he saw no need to attack Hughes. “I am inclined,” the president said, “to follow the course suggested by a friend of mine who says . . . never to murder a man who is committing suicide.”16

But it was a measure of Wilson’s own weakness that he almost lost the election of 1916 to such an uninspiring opponent—and if fewer than 100,000 strategically placed votes had flipped the other way, he might have lost quite badly.

ELECTION NO. 34: 1920

The field of candidates in 1920 was among the weakest in American history.

The Democrats had long assumed that Woodrow Wilson would defy tradition and seek a third consecutive term as president, but a massive stroke in October 1919 ended his active participation in politics. Wilson spent his final 17 months in the White House as a virtual recluse, unavailable even to his own cabinet. His party had no dominant contender to replace him.

The Republicans had once been equally confident about the head of their ticket. “There is but one candidate,” declared the party boss of Pennsylvania, Boies Penrose, in 1918. “He is the only candidate. I mean Theodore Roosevelt.”17 TR was a shadow of his former vibrant self—blind in one eye, deaf in one ear, occasionally hospitalized—yet he was the undisputed Republican front-runner. His death in January 1919 left his party without a clear choice.

Would-be presidents streamed in to fill the void. Fourteen men would attain the status of qualified candidates in 1920—topped only by the 15 in 1880—yet none was truly of presidential caliber. The Republicans labored through 10 ballots before agreeing on their nominee, the largely unknown Warren Harding. The Democrats needed 44 roll calls to confirm the obscure James Cox as their standard-bearer. It was the last time that both parties would conduct multiballot conventions in the same year.

This rampant mediocrity is reflected by the potential indexes for 1920’s 14 candidates. Fifty of the nation’s 57 presidential elections—and all but three since 1840—have featured at least one contender with a PI of 7.0 or greater. The exceptions during the past 175 years were 1928 (with a maximum of 6.9), 1952 (6.7), and lowest of them all, 1920 (6.6). The latter index belonged to Edward Edwards, a New Jersey governor who launched a feeble presidential campaign before vanishing into the mists of history.

If the field seeking a party’s nomination is exceptionally weak, the result in November is almost always negative. Let’s examine the 92 battles for Democratic, Republican, and Whig nominations since the advent of conventions in 1832. Only 14 multicandidate fields lacked a contender with a PI of 7.0 or higher:

| Year and party | Highest PI | Nominee | Win |

| 1928 Democratic | Alfred Smith (6.9) | Alfred Smith (6.9) | — |

| 1908 Democratic | John Johnson (6.8) | William Jennings Bryan (5.2) | — |

| 1952 Democratic | Adlai Stevenson (6.7) | Adlai Stevenson (6.7) | — |

| 1976 Republican | Ronald Reagan (6.7) | Gerald Ford (6.6) | — |

| 1912 Democratic | Woodrow Wilson (6.6) | Woodrow Wilson (6.6) | X |

| 1920 Democratic | Edward Edwards (6.6) | James Cox (5.9) | — |

| 1948 Republican | Thomas Dewey (6.6) | Thomas Dewey (6.6) | — |

| 1920 Republican | William Sproul (6.4) | Warren Harding (6.0) | X |

| 1836 Whig | Hugh White (6.3) | Hugh White* (6.3) | — |

| 1944 Republican | Thomas Dewey (6.3) | Thomas Dewey (6.3) | — |

| 1952 Republican | Earl Warren (6.2) | Dwight Eisenhower (5.6) | X |

| 1928 Republican | Frank Lowden (5.7) | Herbert Hoover (4.0) | X |

| 1856 Republican | John Fremont (5.3) | John Fremont (5.3) | — |

| 1936 Republican | Alfred Landon (4.8) | Alfred Landon (4.8) | — |

* Two Whigs were classified as nominees in 1836. White is listed because he had the highest PI. The other was William Henry Harrison (4.9), who also lost the general election.

The record of 4 wins and 10 losses is decepti vely positive. Three of the victories occurred in years when both parties were below 7.0. Somebody had to win. The only candidate who emerged from a weak field to defeat a candidate with a superior PI was Wilson, who benefited from the Republican schism between Theodore Roosevelt (10.0) and William Howard Taft (8.2) in 1912.

Harding had similar luck in 1920. His PI of 6.0 was unimpressive, yet it was marginally better than Cox’s 5.9. Voters were greatly disillusioned by the indecisive conclusion of World War I, the acrimonious debate over American participation in the League of Nations, and the aimless drift of the Wilson administration. They were eager to vote for anybody the Republicans put forward.

Harding was well aware of his inadequacies. “My God,” he would sputter after reaching the White House, “this is a hell of a place for a man like me to be!”18 But the stars were perfectly aligned for his victory in 1920, despite his low potential index. “There ain’t any first-raters this year,” explained Frank Brandegee, a senator from Connecticut. “We’ve got a lot of second-raters, and Warren Harding is the best of the second-raters.”19

ELECTION NO. 35: 1924

Calvin Coolidge plodded through his political career. He slowly put one foot in front of the other—from city councilman of Northampton, Massachusetts, to city solicitor, clerk of courts, and mayor, up to the state legislature, then lieutenant governor, and finally governor. His simple declaration against a walkout by Boston’s police—“there is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time”—elevated him from obscurity to national prominence in 1919.20 He was elected vice president the following year, assuming the presidency upon Warren Harding’s death in 1923.

The records of Coolidge’s two opponents in 1924’s general election were considerably more distinguished.

John Davis, the Democratic nominee, was hailed as the greatest lawyer in the nation. Oliver Wendell Holmes, who served 29 years as a Supreme Court justice, said he had never encountered anyone “more elegant, more clear, more concise, or more logical.”21 Davis would end his career on the wrong side of history, arguing against racial integration in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education. Yet the winning lawyer in that 1954 confrontation remained an admirer. “He was a great advocate, the greatest,” Thurgood Marshall said of Davis.22

Robert La Follette, the firebrand from Wisconsin, also challenged Coolidge in 1924 on behalf of a reincarnated Progressive Party. La Follette had already established himself as one of the greatest politicians in American history. He would later be named among the seven best senators of all time, as well as the top 10 governors of the 20th century. Nobody else would qualify for both lists.

Coolidge could not match such accomplishments. “He possesses no outstanding ability,” conceded George Norris, a Republican senator from Nebraska.23 Yet the president easily defeated his two high-profile opponents, carrying 35 of 48 states and winning by a landslide in the Electoral College.

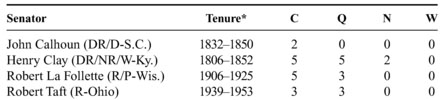

Skill doesn’t always translate to success in presidential politics. Consider the previously mentioned list of great senators. The Senate itself chose its seven “most outstanding” former members, picking five in 1959 and two more in 1999.24 The portraits of all seven hang in the Capitol’s Senate Reception Room.

These were highly ambitious men. Six ran for president. (The seventh, Robert Wagner, was ineligible because of his German birth.) They received primary, convention, and/or general-election votes in 20 different campaigns (C on the following chart), resulting in 16 qualified candidacies (Q). Yet these senatorial giants secured only two major-party nominations (N), both by Henry Clay, and were completely unable to win (W) the presidency:

There is no official roster of excellent governors. The closest thing is a list published in a 1981 newsletter of the National Governors Association, compiled by George Weeks, then the chief of staff for Michigan governor William Milliken.25

Weeks, who also served as a fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics, named the 10 outstanding governors of the 20th century. A few of his choices were debatable—Nelson Rockefeller had more style than substance, Woodrow Wilson was governor for just two years—but it’s the best list we have. Eight of these hotshot governors sought the presidency a total of 25 times. (If not for his assassination in 1935, Huey Long surely would have joined their ranks.) Only five of these campaigns resulted in nominations, and Wilson was the sole winner:

Many of these outstanding senators and governors, accustomed to success and adulation, were embittered by their inability to reach the White House. Daniel Webster spoke for the group after failing to secure the Whig nomination in 1852, his third and final strike. “How will this look in history?” he wailed.26

It did not turn out as badly as he feared. Webster’s portrait hangs today in the Senate’s hall of fame, enduring proof of his legislative and oratorical excellence. The last two presidents of his lifetime (Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore) and the man elected nine days after his death (Franklin Pierce) have dissolved into shadowy figures familiar to few Americans— and respected by even fewer.

ELECTION NO. 36: 1928

Herbert Hoover was ill-suited for the presidency, especially its most conspicuous duties. Any public appearance, no matter how minor, inevitably filled him with dread. “I have never liked the clamor of crowds,” he later admitted. “I intensely dislike superficial social contacts. I made no pretensions to oratory, and I was terrorized at the opening of every speech.”27

Part of the problem was Hoover’s lack of practical political experience. Every other president served as a vice president, governor, senator, representative, secretary of state, secretary of war, and/or army general before reaching the White House. Hoover never held any of those influential jobs. His highest government position was secretary of commerce, which put him a distant ninth among 10 cabinet officers in the presidential line of succession. Only the secretary of labor was beneath him.

Hoover’s lowly status in 1928 was reflected by his anemic potential index of 4.0. Sixty-seven qualified candidates have run with PIs of 4.0 or less, and 64 of them (95.5 percent) have failed to win major-party nominations. The exceptions were Charles Cotesworth Pinckney in 1808, DeWitt Clinton in 1812, and Hoover in 1928. Hoover, of course, was the only one who went on to win a general election.

So how did he do it? How did such an inept politician successfully defy a statistical tenet of presidential politics?

The answer can be found in Hoover’s philanthropic work during World War I. He coordinated international relief operations—transporting food to 10 million starving Europeans—and then served as an adviser to Woodrow Wilson at the Paris peace conference. He was a dazzling success in both roles. Famed economist John Maynard Keynes declared that Hoover was “the only man who emerged from the ordeal of Paris with an enhanced reputation.”28 Franklin Roosevelt would experience a change of heart in later years, but he eagerly promoted Hoover for the White House as early as 1920. “He is certainly a wonder, and I wish we could make him president,” FDR wrote. “There couldn’t be a better one.”29

Hoover’s halo retained its sheen in 1928, establishing him as the front-runner in a weak field of Republican candidates. President Calvin Coolidge mysteriously refused to seek another term, and the party’s other contenders were too old, too mossbacked, or in the case of George Norris, too progressive to win the nomination. All of their PIs were higher than Hoover’s 4.0, but none surpassed Frank Lowden’s 5.7, itself a dangerously low score.

The general election turned out to be even easier for Hoover. Democratic nominee Alfred Smith appeared to be vastly superior on paper. The four-term governor of New York boasted a potential index of 6.9, nearly three points better than Hoover. But a trio of factors set up the Democrat for defeat:

The result was yet another landslide, the third in a row. Hoover drew 444 electoral votes, surpassing his Republican predecessors, Coolidge and Warren Harding.

But danger lurked beneath Hoover’s numbers in 1928. Candidates who successfully overcome an unimpressive potential index are frequently destined for trouble. Listed next are the 10 general-election winners who were saddled with the lowest PIs. Only three were reelected four years later. Four were defeated, and the one who declined to run (James Buchanan) surely would have met the same fate:

| Winning candidate | PI | Next race |

| Herbert Hoover (R-1928) | 4.0 | Defeated for reelection in 1932 |

| Zachary Taylor (W-1848) | 4.1 | Died in office |

| James Buchanan (D-1856) | 5.1 | Declined to run in 1860 |

| George Washington (F-1789) | 5.6 | Reelected in 1792 |

| John Quincy Adams (DR-1824) | 5.6 | Defeated for reelection in 1828 |

| Dwight Eisenhower (R-1952) | 5.6 | Reelected in 1956 |

| John Adams (F-1796) | 5.7 | Defeated for reelection in 1800 |

| Ronald Reagan (R-1980) | 5.7 | Reelected in 1984 |

| William Howard Taft (R-1908) | 6.0 | Defeated for reelection in 1912 |

| Warren Harding (R-1920) | 6.0 | Died in office |

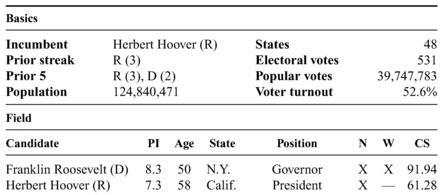

Hoover would try to buck this trend in the Depression year of 1932, but failed badly. That year’s Democratic nominee, Franklin Roosevelt, wielded a PI (8.3) that was considerably stronger than Smith’s in 1928. FDR quickly established a bond with lower- and middle-class Americans, promising to reverse the nation’s economic collapse.

Hoover knew that his run of political luck was over. He had defied the odds once, but it was a feat he could not repeat. He later described the outcome in military terms. “General Prosperity had been a great ally in the election of 1928,” he wrote. “General Depression was a major enemy in 1932.”31

ELECTION NO. 37: 1932

Unemployment stood at 7.4 percent when voters went to the polls in November 1992. It wasn’t a terribly big number in historical terms, but it was two percentage points higher than the rate four years earlier. That wasn’t good news for George H. W. Bush, the Republican president.

Bill Clinton had been hammering away on the economy since the 1992 campaign began. The challenger accused Bush of watching passively as American employers shifted operations to Latin America and Asia. “He promised us 15 million jobs,” Clinton said. “He just didn’t tell us where they were going to be created.”32 The Democrat predicted that Bush would soon learn what it meant to be out of work. “Unemployment only has to go up by one more person before a real recovery can begin,” Clinton said. “And Mr. President, you are that man.”33

Bush had enjoyed immense popularity after American troops won the Gulf War in February 1991—his approval rating soared to the unprecedented height of 89 percent—but he was unceremoniously tossed from office just 21 months later. Voters simply could not forgive him for allowing the economy to deteriorate.

Nobody was surprised, not even George Bush.

Presidents have always kept a close eye on the economy, but those serving since 1932 have been especially attentive. They all know the story of Herbert Hoover, who won the 1928 election with ease after promising a future of unparalleled prosperity, only to be unseated four years later as the Great Depression reached its depth.

“We in America today,” Hoover insisted in 1928, “are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.”34 The unemployment rate was a comfortable 4.4 percent when he was elected. But it soared to 23.6 percent by 1932, more than triple the figure that would doom Bush 60 years later. Newly impoverished Americans congregated in shantytowns known as “Hoovervilles,” the clearest possible indication that the president was headed for a landslide defeat.

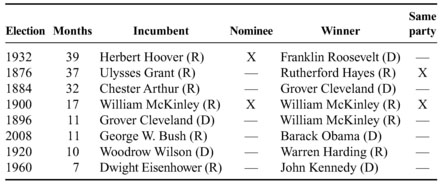

The election of 1932 is the most extreme example, but seven other presidential campaigns since 1860 were conducted in the midst of economic recessions. The results were pretty much what you, Herbert Hoover, and George Bush would have expected.

America’s business cycles are tracked by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which officially determines the point at which the economy has reached a peak or a trough. The span from the former to the latter is known as a period of contraction, or more commonly as a recession. Upward movement from a trough to a peak is a period of expansion.

If we scan NBER’s records for presidential campaigns that occurred during periods of contraction, we find eight instances in which a recession was at least half-a-year old on Election Day. The incumbent party was tossed out of the White House in six of those cases, including 1932:

Hoover obviously carried the biggest burden. The Depression officially entered its 39th month when ballots were cast in 1932, and the president was punished accordingly. Challenger Franklin Roosevelt carried all but 6 of 48 states, winning almost 89 percent of the votes in the Electoral College.

William McKinley was the only other incumbent to be nominated for a new term during a lengthy recession. He was fortunate in two ways. Voters were still excited by the nation’s recent victory in the Spanish-American War, and the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan in 1900, the same candidate McKinley had defeated handily in 1896. The president was reelected.

Incumbents were absent from the remaining elections on the recessionary list. Chester Arthur sought the Republican nomination in 1884, but was repudiated. The other five presidents, all wrapping up their second terms, did not run again. Their parties, however, were evicted from the White House in every case but one. Only in 1876 did the departing president’s party retain power, and then by the narrowest margin possible. Rutherford Hayes won by a single electoral vote under highly questionable circumstances.

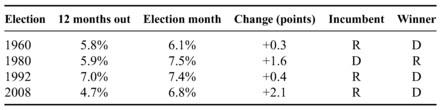

You might have noticed that George H. W. Bush is missing from the previous list. His recession officially ended in 1991, a year before he sought reelection, but that didn’t get him off the hook. A sluggish recovery provided Bill Clinton with plenty of economic ammunition. The unemployment rate actually rose during the 12 months preceding the 1992 election, something that has occurred only four times in the Modern Era. It was fatal to the incumbent party in each instance:

A great mythology has grown up around the election of 1960, suggesting that John Kennedy’s superior performance in their first televised debate clinched his victory over Richard Nixon. But the evidence doesn’t support that assertion. Kennedy led the Gallup Poll by a single percentage point prior to the telecast. He won the election by just 0.17 of a point.

Robert Finch, who served as Nixon’s campaign director, admitted that his man performed badly on TV. But he knew the real reason for the narrow Republican defeat. “Conceding the worst on everything else,” he said, “we still would have won if 400,000 people had not become unemployed during the last 30 days of the campaign.” 35 The story was the same in 1960 as in 1932, 1992, and almost every other presidential election. The economy usually comes first.

ELECTION NO. 38: 1936

Alfred Landon wouldn’t have been taken seriously as a presidential candidate under normal circumstances. But he did not run in normal times.

Landon was elected governor of Kansas by the tightest of margins in 1932, attracting only 35 percent of the votes in a three-way race. Each of his opponents topped 30 percent. Landon deserved credit for winning, but his level of support was disappointingly small for a Republican candidate in one of the nation’s most solidly Republican states. His reelection two years later came more easily, though he edged his Democratic opponent by only eight percentage points.

Yet Landon soon would be trumpeted as the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination in 1936. The party had few alternatives. Voters had purged Republicans from all levels of government in retribution for the Great Depression. Only 25 Republicans remained in the Senate, where they were vastly outnumbered by 69 Democrats. Landon was the only Republican governor— the only one— to run for reelection in 1934 and win.

Journalists were overly impressed by this feat, somehow believing that it elevated Landon to political equality with President Franklin Roosevelt. Renowned publishers William Randolph Hearst and Cissy Patterson trekked to Topeka to take the measure of the potential Republican nominee. “I think he is marvelous,” Hearst declared. Patterson went one better. “I thought of Lincoln,” she said.36

But the candidate did not share their confi dence. Landon wrote a friend that he doubted the Republican Party was “so hard up as to name a man from Kansas . . . Not that Kansas couldn’t furnish a good president, but the leaders of both parties just don’t think of us that way.”37 There was good reason for skepticism. Landon’s potential index of 4.8 would be the fourth-lowest for any major-party nominee in the 20th century. The difference between his PI and Roosevelt’s perfect 10.0—a margin of 5.2 points— would be the widest ever.

PI gaps larger than four points have occurred in 7 of the 57 presidential elections. The favorites, to nobody’s surprise, won handily all seven times:

| Year | PI gap | Winner | Loser |

| 1936 | 5.2 | Franklin Roosevelt (D, 10.0) | Alfred Landon (R, 4.8) |

| 1812 | 5.0 | James Madison (DR, 8.7) | DeWitt Clinton (F-DR, 3.7) |

| 1940 | 4.9 | Franklin Roosevelt (D, 9.6) | Wendell Willkie (R, 4.7) |

| 1924 | 4.7 | Calvin Coolidge (R, 9.1) | John Davis (D, 4.4) |

| 1864 | 4.2 | Abraham Lincoln (R, 8.9) | George McClellan (D, 4.7) |

| 1872 | 4.2 | Ulysses Grant (R, 9.0) | Horace Greeley (D-LR, 4.8) |

| 1804 | 4.1 | Thomas Jefferson (DR, 9.2) | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (F, 5.1) |

How lopsided were these races? The average campaign score for the seven winners was 89.45, absolutely dwarfing the losers’ average of 62.25. The worst thrashing occurred in 1936, when Roosevelt (CS of 95.88) buried Landon (57.66). The Republican carried only two states—Maine and Vermont—for a paltry eight electoral votes.

The defeat came as no great surprise to Landon, who had been dubious about his chances from the start. He beckoned his wife to pose with him for a photographer on election night. “Come on, Mother, and get your picture took,” he said. “It will be the last chance.”38

ELECTION NO. 39: 1940

Loyal supporters urged Franklin Roosevelt to seek a third term in 1940, yet he showed no inclination to buck tradition. FDR spoke not of another campaign, but of his impending retirement. “I want to go home to Hyde Park,” he told anybody who brought up the election. Most Democrats took him at his word.

Daniel Tobin was not among them. The head of the Teamsters Union rushed to the White House in early 1940 to plead his case one more time.

“Mr. President, you just have to run for the third term,” Tobin said.

“No, Dan, I just can’t do it,” Roosevelt replied. “I’ve been here a long time. You don’t know what it’s like.” He began talking about his estate on the Hudson River—“I want to take care of my trees”—and his need for peace and quiet.

And that was that. Or was it?

Roosevelt smiled. He had one more thing to tell Tobin. “You know,” the president said, “the people don’t like the third term either.”39

That indeed was the challenge facing FDR in 1940. He secretly might have planned to defy George Washington’s two-term limit—historians have never been able to determine his true intentions—but he had to respect the popular will. And the people were emphatic: 63 percent of Americans believed a president should retire after two terms, according to a 1939 Gallup Poll.40

So Roosevelt played it coy. He evaded reporters’ questions about the election, encouraged other Democrats to seek the presidency, and pretended to be surprised when party leaders endorsed him. Germany invaded France in May, causing millions to drop their objections to a third term. Polls detected a dramatic rise in the percentage of voters who preferred to keep Roosevelt around. Yet the president refused to rise to the bait. He told the Democratic convention that he had “no desire or purpose to continue in the office.”41

It was all for show. Roosevelt was easily renominated after a stage-managed demonstration of support that showed the fine hand of the White House. His fall campaign dusted off the age-old warning against changing horses in the midst of a rapidly flowing river, much to the annoyance of Republican nominee Wendell Willkie. “There comes a time when it is very wise to get off that horse in midstream,” Willkie retorted, “because if we don’t, both you and the horse will sink.”42 Voters didn’t buy it. They gave Roosevelt his third straight landslide victory.

Sixteen candidates other than Franklin Roosevelt won a pair of presidential elections, though half never faced the third-term temptation. Abraham Lincoln and William McKinley were assassinated after their second victories, Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace, and another five (including Barack Obama) were limited to two terms by the Twenty-second Amendment.

Most of the rest—except Ulysses Grant and Woodrow Wilson—felt that eight years in the White House were enough. Grant left office in 1877, traveled around the world for two years, then returned to seek the Republican nomination in 1880. Wilson hoped to head the Democratic ticket for a third time in 1920, even though a stroke rendered him incapable of campaigning. Both men were spurned by their parties.

But don’t get the wrong impression. Most two-term presidents would have been formidable candidates if they had run again. I’ve calculated the potential indexes and chances of victory (CV%) for all 16 in their third-term years, even those who died, resigned, or were constitutionally blocked. (This is a hypothetical exercise, after all.) If they had been able to secure renomination—admittedly a big if in some cases—all would have enjoyed better than a 50–50 chance of winning the general election:

| President (third-term year) | Age | PI | CV% | Decision |

| Thomas Jefferson (DR-1808) | 65 | 8.5 | 98% | Declined to run |

| William McKinley (R-1904) | 61 | 8.3 | 98% | Died in office |

| Woodrow Wilson (D-1920) | 63 | 8.4 | 82% | Physically unable to run |

| James Monroe (DR-1824) | 66 | 7.8 | 79% | Declined to run |

| George W. Bush (R-2008) | 62 | 9.0 | 75% | 22nd Amendment |

| George Washington (F-1796) | 64 | 9.1 | 74% | Declined to run |

| Dwight Eisenhower (R-1960) | 70 | 7.8 | 74% | 22nd Amendment |

| Ulysses Grant (R-1876) | 54 | 9.0 | 70% | Declined, but ran in 1880 |

| Barack Obama (D-2016) | 55 | 8.5 | 69% | 22nd Amendment |

| Andrew Jackson (D-1836) | 69 | 7.5 | 69% | Declined to run |

| Ronald Reagan (R-1988) | 77 | 7.8 | 66% | 22nd Amendment |

| Richard Nixon (R-1976) | 63 | 8.4 | 62% | Resigned |

| James Madison (DR-1816) | 65 | 8.0 | 62% | Declined to run |

| Abraham Lincoln (R-1868) | 59 | 8.5 | 61% | Died in office |

| Bill Clinton (D-2000) | 54 | 8.8 | 59% | 22nd Amendment |

| Grover Cleveland (D-1896) | 59 | 8.8 | 56% | Declined to run |

Each president was pitted against the actual nominee of the opposing party in the designated election. Obama's hypothetical opponent in 2016 was assigned a PI of 6.9, the average PI for all Modern Era major-party nominees who were not incumbents.

Thomas Jefferson left office willingly after two terms. He seemed so jubilant at the inauguration of his successor, James Madison, that a fellow celebrant congratulated him for having shed the burden of public office. “Yes, indeed,” the ex-president replied, “and I am much happier at this moment than my friend.”43 But there’s no doubt that Jefferson would have trounced the Federalist nominee in 1808, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, as easily as he had defeated him four years earlier.

William McKinley, had he lived, would have matched Jefferson’s 98 percent chance of winning a third term. He had been reelected by a wide margin in 1900, a year before his assassination. Who could disagree that he would have buried the hapless Democratic nominee, Alton Parker, in 1904?

But a note of caution: CV%, of course, is a general indicator based on the records of all candidates with comparable potential indexes. It is not tailored to specific circumstances. A healthy Woodrow Wilson might have been a formidable candidate in 1920—the odds that year were 82 percent for somebody with a PI of 8.4—but the nation was in no mood to reelect an invalid who had lost control of the federal government. Warren Harding, with all his faults, seemed a better choice.

ELECTION NO. 40: 1944

Allied troops be gan to make headway as World War II dragged into 1944. American, British, and Canadian infantrymen landed on the beaches of Normandy in June, and the Pacific Fleet set course toward Tokyo. But it remained difficult to detect any light at the end of the tunnel. Victory over Germany and Japan appeared to be years away.

Rumors began to circulate that Franklin Roosevelt intended to cancel the November election so that he could focus solely on the war effort. Reporters flocked to the White House to seek an explanation. “Gosh,” replied a baffled FDR, “all these people around town haven’t read the Constitution.” 44 Americans would cast their ballots on November 7, 1944, as scheduled.

This was the third (and last) presidential campaign to be conducted with the nation on a full war footing. Roosevelt’s two predecessors had been confronted with similar questions about the operation of democratic institutions in wartime, and they had answered the same way.

James Madison, heralded as the father of the Constitution, was especially careful to adhere to its strictures during the War of 1812. “Of all the enemies to public liberty,” he had once warned, “war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded.”45 He had no intention of allowing the conflict with Great Britain to disrupt that year’s election.

Abraham Lincoln demonstrated much less concern about personal liberties during the Civil War, yet he considered the political process to be sacrosanct. “We cannot have free government without elections,” he said. “If the rebellion could force us to forgo or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.”46

The three presidents also had practical reasons for wanting their elections to proceed. Americans typically rally to the flag during a war, endorsing (at least temporarily) the actions of their elected officials. And, indeed, the incumbents swept the wartime contests:

The electoral-vote percentages and campaign scores for all three men are suitably impressive, but the popular-vote column can’t help but dampen our admiration. Lincoln and Roosevelt posted comfortable majorities, yet neither came close to Lyndon Johnson’s all-time record of 61.05 percent. Lincoln’s 55.09 percent is 12th in the single-year PV% standings, and Roosevelt is 17th. (Madison predated widespread popular voting.) Nearly half of all voters ignored the national surge of martial spirit and opposed each president, showing the resilience of partisanship during wartime.

Declared wars have become a thing of the past. Congress has not approved a formal declaration of hostilities since 1942. Subsequent conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, and the Middle East were initiated by presidential directives, usually backed by congressional resolutions. The public reacted to these undeclared wars in much the same way as to the official wars noted previously. Public support was initially strong, but significant opposition always emerged.

The proof is in the popularity ratings for the presidents involved. Each is listed in the following chart, along with his affirmative score in the first Gallup Poll after the onset of military action and the comparable ratings precisely one and two years later:

Vietnam shows this trend most clearly. Johnson established his PV% record just three months after congressional passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized military action in Southeast Asia. The public was solidly behind the president in 1964, but critics would soon gain the upper hand. Millions wanted the war prosecuted with greater vigor; millions more wanted it brought to an end.

Johnson was caught in the middle, and his Gallup rating plummeted to 36 percent by March 1968, forcing his retirement. “My daddy committed political suicide for that war in Vietnam,” one of his daughters would say. “And since politics was his life, it was like committing actual suicide.”47

ELECTION NO. 41: 1948

Everybody knows about 1948. That was the year when President Harry Truman thumbed his nose at the pollsters, defied the extreme wings of the Democratic Party, and gave hell to Thomas Dewey.

That, anyway, is the standard storyline. The only problem is that it doesn’t always coincide with the facts.

It’s true that the public-opinion surveys in 1948 were inaccurate, though they weren’t as far out of line as is commonly believed today. The final Gallup Poll prior to the election yielded this prediction:48

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 49.5% |

| Harry Truman (D) | 44.5% |

| Henry Wallace (P) | 4.0% |

| Strom Thurmond (SRD) | 2.0% |

This was a substantial improvement for Truman, who had trailed Dewey by 11 percentage points two months earlier.49 But he was still five points short, apparently doomed to defeat.

Yet a tiny glimmer of hope remained for the Democrats. Polls are never precise. A small margin of error is built into each survey, roughly four percentage points for a sample the size of Gallup’s. If we stretch that margin to the limit—giving four extra points to Truman and taking them away from Dewey—here’s what we get:

| Harry Truman (D) | 48.5% |

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 45.5% |

That’s remarkably close to the actual outcome, a Truman victory by 4.4 percentage points. If polling firms had acknowledged this possibility in 1948, they would have been judged less harshly by history. But they were guilty of hubris. Elmo Roper, a prominent pollster, announced in September that he was suspending his surveys because “no amount of electioneering” could save Truman’s campaign.50 His competitors remained in the field, though they acknowledged no possibility of a Dewey defeat. The president disdained them all. “I wonder how far Moses would have gone if he had taken a poll in Egypt,” he snapped.51

Truman’s victory was remarkable because of the sharp divisions that existed within the Democratic Party. Liberals (and more than a few communists) were drawn to the Progressive Party of former vice president Henry Wallace, while conservative Southerners were attracted to the blatantly racist States’ Rights Democratic Party of South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond. Neither of these minor-party challengers had a prayer of victory, but they seemed likely to peel millions of votes from Truman in the East and South, votes he couldn’t afford to lose.

Wallace peaked at 7 percent in one of Gallup’s early polls, and Thurmond seized control of the Democratic machinery in four Southern states.52 Yet these proved to be their high-water marks. The two extremists slipped to a combined 6 percent in the final Gallup survey and 4.8 percent in the election itself. Neither was a significant factor.

But what if they had fulfilled the pundits’ initial expectations? Let’s rerun the 1948 election after making three changes:

Here’s how it all turns out:

| Candidate | SC | PV | PV% | EV |

| Thomas Dewey (R) | 19 | 21,752,475 | 44.25% | 267 |

| Harry Truman (D) | 25 | 22,955,550 | 46.70% | 225 |

| Strom Thurmond (SRD) | 4 | 1,688,294 | 3.43% | 39 |

| Henry Wallace (P) | 0 | 2,473,706 | 5.03% | 0 |

Dewey emerges as the winner by the barest of margins, a single vote above the Electoral College’s threshold of 266. One can imagine the pressure that would have been applied to his 11 electors in Delaware and Maryland to defect to Thurmond, thereby tossing the election into the House of Representatives. It’s a plausible scenario. Both of those states maintained segregated school systems in 1948 and had a certain sympathy for the white Southern cause.

The election just as easily could have yielded a massive repudiation of the president. Let’s flip 91,541 votes from Truman to Dewey in nine states—just 0.19 percent of the 48.69 million votes that were cast. The count in the Electoral College would have been 305 for Dewey, only 187 for Truman:

| State | EV | Flip from Truman to Dewey |

| Nevada | 3 | 968 |

| Wyoming | 3 | 2,204 |

| Idaho | 4 | 2,929 |

| Ohio | 25 | 3,554 |

| California | 25 | 8,933 |

| Colorado | 6 | 13,788 |

| Iowa | 10 | 14,182 |

| Illinois | 28 | 16,807 |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 28,176 |

None of this takes away from Harry Truman’s victory in 1948. Was it impressive? It most definitely was. But was it the decisive triumph portrayed in political mythology? No, it surely wasn’t. It was a good bit closer than Truman’s hagiographers would have us believe.

ELECTION NO. 42: 1952

The 1952 Democratic convention struggled through three roll calls before settling on Adlai Stevenson as its nominee.

Nobody condemned the length of the process. The previous eight presidential campaigns had featured six multiballot conventions, most notably the 1924 Democratic Party marathon that droned on for 103 roll calls. The eventual icon of that party, Franklin Roosevelt, persevered through four ballots to secure his first nomination in 1932. Two recent Republican standard-bearers, Wendell Willkie and Thomas Dewey, needed extra ballots to win their respective nominations in 1940 and 1948. Lengthy intra-party battles were accepted as a common aspect of American political life.

But not after 1952.

Never again would a major party need more than a single ballot to anoint its presidential candidate. All 30 conventions since 1956—15 Democratic, 15 Republican—have completed their business on the first roll call. Few of these contests were close. Only seven of the winners drew less than two-thirds of the delegate votes:

| Nominee | FB% | Runner-up | FB% |

| Richard Nixon (R-1968) | 51.91% | Nelson Rockefeller | 20.78% |

| Gerald Ford (R-1976) | 52.55% | Ronald Reagan | 47.37% |

| John Kennedy (D-1960) | 52.99% | Lyndon Johnson | 26.89% |

| Walter Mondale (D-1984) | 55.71% | Gary Hart | 30.52% |

| George McGovern (D-1972) | 57.31% | Henry Jackson | 17.41% |

| Jimmy Carter (D-1980) | 63.74% | Edward Kennedy | 34.54% |

| Adlai Stevenson (D-1956) | 66.00% | Averell Harriman | 15.31% |

The most recent nominee on this list, Walter Mondale, ran in the distant year of 1984, which means we haven’t seen a truly competitive convention in more than three decades.

Nor is there likely to be another. Nominees are now chosen during the primary season in late winter and early spring, months before the midsummer party meetings are called to order. “Political conventions have become the appendix of the body politic: a vestige of something that once had a function, but no longer does,” wrote David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prizewinning columnist. “And yet they endure, against all reason.”53

That they do. Conventions have degenerated into pep rallies whose sole purpose is to attract an audience on television. Network executives blithely— and inexplicably—allocate massive amounts of airtime to the party-produced films and party-approved speeches that dominate these empty pageants. If TV’s bigwigs ever come to their senses and pull the plug, the convention will quickly become an endangered species. Extinction is likely.

But the prospecti ve demise of today’s tame version cannot diminish the golden memories of its influential antecedent. H. L. Mencken covered every major-party convention between 1904 and 1948, when they were still at their zenith. He considered them “as fascinating as a revival or a hanging.” The bulk of any convention could be exasperatingly dull, Mencken conceded, but “suddenly there comes a show so gaudy and hilarious, so melodramatic and obscene, so unimaginably exhilarating and preposterous that one lives a gorgeous year in an hour.”54

Recent history would have been different if the convention had remained the dominant force in the nominating process. It might not necessarily have been better, but it undoubtedly would have been altered.

Successful candidates who relied heavily on the primaries, such as John Kennedy in 1960 and Jimmy Carter in 1976, might never have reached the White House. Democratic Party leaders would have stopped Kennedy if at all possible, and he knew it. “If it ever goes into a back room,” Kennedy said of his battle for the nomination, “my name will never emerge.”55 Nominees whose philosophies were outside the mainstream, such as Barry Goldwater in 1964 and George McGovern in 1972, almost certainly would have been vetoed by party bosses.

But all of this is speculation. The reality is that today’s conventions merely ratify the decisions already made by primary voters and caucus participants, a role that is unlikely to change. So why are they still part of the political calendar? A reporter posed that question to the Democratic Party’s chairman, Don Fowler, in 1996. “We’ll continue to have it,” Fowler responded with a smile, “as long as you keep covering it.”56

ELECTION NO. 43: 1956

A strange thing happened in 1956. Missouri voted for Adlai Stevenson.

Nobody could explain it. Dwight Eisenhower had carried 39 states— Missouri among them—when he crushed Stevenson four years earlier. Ike widened his lead in their 1956 rematch, holding onto 38 of his 1952 states and adding three more. Missouri was the only original Eisenhower state to jump ship.

It was doubly strange because Missouri was widely acclaimed as an uncanny barometer of the national mood. It had cast its electoral votes for every national winner since 1904—13 straight elections—and it would not be wrong again until 2008. The Chicago Tribune hailed Missouri in 2004 as “a bellwether state that almost exactly mirrors the demographic, economic, and political makeup of the nation,” and indeed, it voted for George W. Bush that year, its 25th correct call in 26 elections.57

Sixteen other states supported more than 80 percent of the national winners between 1904 and 2004, but none could match Missouri’s record for accuracy:

| State | Elections (1904-2004) | Right | Wrong | Accuracy rate |

| Missouri | 26 | 25 | 1 | 96.2% |

| Nevada | 26 | 24 | 2 | 92.3% |

| Ohio | 26 | 24 | 2 | 92.3% |

| New Mexico | 24 | 22 | 2 | 91.7% |

| Montana | 26 | 23 | 3 | 88.5% |

| Idaho | 26 | 22 | 4 | 84.6% |

| Illinois | 26 | 22 | 4 | 84.6% |

| Tennessee | 26 | 22 | 4 | 84.6% |

| Arizona | 24 | 20 | 4 | 83.3% |

| California | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| Delaware | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| Kentucky | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| New Hampshire | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| New Jersey | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| Utah | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| West Virginia | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

| Wyoming | 26 | 21 | 5 | 80.8% |

Missouri came remarkably close to an unblemished mark. Stevenson carried the state by 3,984 votes in 1956. A flip of 1,993 votes—just 0.11 percent of the statewide total—would have shifted Missouri to Eisenhower’s column, running its record to 26–0.

A case can be made, however, that other states were better bellwethers between 1904 and 2004. This argument hinges on average state deviation (ASD), an indicator first mentioned during our discussion of the election of 1860. ASD is the average difference between PV% at the national and state levels for a candidate or candidates—in this case, the winners of the 26 elections covered by the previous chart. The smaller its ASD, the closer a state is to mirroring the voting patterns in the country as a whole.

Thirteen states scored below 4.00 on the ASD scale for the 1904–2004 period, correlating remarkably well with the national mood. New Mexico, Ohio, and Delaware were the best of all:

| State | Elections (1904-2004) | Right | Wrong | ASD |

| New Mexico | 24 | 22 | 2 | 2.24 |

| Ohio | 26 | 24 | 2 | 2.33 |

| Delaware | 26 | 21 | 5 | 2.86 |

| Missouri | 26 | 25 | 1 | 3.04 |

| Illinois | 26 | 22 | 4 | 3.18 |

| California | 26 | 21 | 5 | 3.21 |

| New Jersey | 26 | 21 | 5 | 3.47 |

| West Virginia | 26 | 21 | 5 | 3.63 |

| Oregon | 26 | 19 | 7 | 3.66 |

| Colorado | 26 | 20 | 6 | 3.77 |

| Connecticut | 26 | 19 | 7 | 3.82 |

| Washington | 26 | 19 | 7 | 3.87 |

| Kentucky | 26 | 21 | 5 | 3.92 |

New Mexico deviated from the winner’s national PV% by an average of 2.24 percentage points in 24 elections, and it came within a single point 11 times. (New Mexico joined the Union in 1912, thereby missing the period’s first two elections.) The state posted its best performance in 2000, when George W. Bush carried 47.85 percent of New Mexico’s votes, just 0.02 points off his national figure of 47.87 percent.

Sixteen other states came within a single point of the winner’s PV% at least four times between 1904 and 2004, including Delaware (seven) and Ohio (six). But Missouri did not share their precision. It had only three close calls. The final one occurred in 1980, when it finished 0.41 points away from Ronald Reagan’s national percentage.

The whole thing began to unravel in 2008. Missouri opted for John McCain by a narrow margin over Barack Obama that year, its first incorrect call since Stevenson. Mitt Romney’s victory was much more decisive in 2012, putting Missouri on the loser’s side for the second straight election, something that hadn’t happened since 1900.

Pundits struggled to explain Missouri’s sudden change of direction. Perhaps its Southern roots were reasserting themselves. Or its rural and suburban voters might be turning out in greater numbers. Or the Democrats might not be devoting sufficient resources to the state. Who could say for sure?

But one thing is certain. The title of bellwether is no longer appropriate. “We used to look to Missouri,” said University of Virginia political analyst Larry Sabato in 2012. “We don’t anymore.”58