Rock and Wall, Silver Falls Canyon

The relationship between the water streaks on the boulder and those on the huge sandstone canyon wall was inescapable

Rock and Wall, Silver Falls Canyon

The relationship between the water streaks on the boulder and those on the huge sandstone canyon wall was inescapable

The Heart of Intuition and Creativity

INTUITION IS SOMETHING WE ALL HAVE to one degree or another. It doesn’t seem to be something that can be learned or taught, but it can be discussed, and it can be recognized as a valuable asset that can be utilized when appropriate. Most importantly, intuition can be developed, because it is basically a product of long-term observation and understanding. It should certainly not be dismissed as meaningless.

I feel that intuition and imagination go hand in hand, and both are prerequisites for creativity. But they don’t come out of thin air. Behind them is a vast amount of deep interest, observation, knowledge, and involvement with the subject. Nobody can be intuitive or imaginative in a realm in which they have no knowledge, interest, or involvement.

Beethoven learned musical composition from the best composers of his day, with the likes of Haydn and Mozart as his prime models. Then he went beyond them, far beyond. Beethoven changed the way music was understood, composing pieces unlike anything that had ever been written as he probed further into the emotional depths and content of the medium. He could not have accomplished all that he did without a solid grounding in the field of music, an overwhelming passion for music, and direct involvement in composing music.

A century ago, an obscure man with a strong background in physics asked what the universe would look like to a particle traveling at the speed of light. The question itself was a leap of imagination. It was pure intuition and a remarkably brilliant mind that then led Albert Einstein to the special theory of relativity, and 10 years later to the general theory of relativity, which answered some anomalies in the orbit of Mercury around the sun that even Newton’s theories failed to explain. It also lead to the famous equation E=mc2, which showed that matter and energy were two sides of the same coin, an astonishing transformation in scientific understanding. This all started with insight, intuition, and imagination, all based on a deep understanding of and involvement in the field of endeavor.

Mark Twain, a great writer for at least half a century, ended his career with Letters from the Earth—in my opinion, the best book ever written—which showed Twain’s full grasp of human characteristics and foibles, proving that Twain was easily a hundred years ahead of his time, and always will be. It was withheld from publication for over 20 years by his daughter, who thought it would harm his reputation. But this extraordinary, short book is a tour de force of insight, imagination, and creativity, not to mention sarcasm and humor.

Other geniuses, too numerous to mention and in so many diverse fields, have changed the direction of our thinking—from Rembrandt to Dali in painting, Newton to Feynman in physics, Bill Gates to Steve Jobs in personal computing, and Jeff Bezos in marketing. All of these people have had dramatic impacts on our lives, even if we are not aware of it. They exhibited remarkable insight, intuition, and creativity. None of these qualities are exhibited by inactive minds. These people were all well versed in their fields and were looking to go beyond anyone who preceded them, and they succeeded in doing so.

Paul McCartney, perhaps the most storied of the storied Beatles, told of how he sat in his room one day trying hard to come up with a new song. He was devoid of ideas and was about to slump into bed tired and defeated when suddenly the song “Nowhere Man” jumped into his head in its entirety—words and music. It was there, complete, start to finish.

Most of us hear a story like that and say, “I want to do exactly that in my field.” Of course we want to do that. So what’s the key? How do we do that? Needless to say, there is no formula for doing that. There’s no key. When we hear that dispiriting news, most of us say, “So that proves you can’t teach creativity.” That’s probably correct. I’ve already said that you can prepare for creativity, but you probably can’t teach it in the sense of making it happen. The key to creativity is preparation.

The six prerequisites listed in the following section are the basis for creative thinking in any field. Total involvement is a great part of that preparation. That doesn’t mean you have to be engaged in your pursuit 24 hours a day, but you do have to think about it often and deeply, you have to love doing it, and you have to want to get back to it even during those times when you’re obligated to do other things. Does this mean you have to be obsessive? Maybe, but not necessarily. It simply means that you have to be deeply involved in the issue.

McCartney was deeply involved in music. Not just the type of music that he produced with the Beatles when they were working together as a group, but also on his own after they split up. He was open to all forms of music, from classical Western music to sitar music from India. He knew a lot about music. It was running through his mind at all times. Maybe he was obsessed, maybe not; we can only speculate about that. But it is certainly true that he was deeply immersed in music.

I have been involved in photography for more than 40 years. I think about it all the time, not continuously to the exclusion of other thoughts, but throughout the day as I go through life. I see lots of things in terms of “pictures,” as if I had my camera in hand at every moment. I think of possibilities of doing new and different things in the field, in the darkroom, or on the computer. In short, I’m involved even when I’m not actively engaged.

You can do the same thing, but you have to start with a solid basis of knowledge in the field. That’s where most people fall short: they want to be creative, but they don’t want to put in the time for proper preparation. McCartney put in huge amounts of time understanding music, so thoughts that he wasn’t even consciously aware of were regularly stirring around in his head. Looking back at the list of formidable people at the beginning of this chapter tells you the same story: they were all deeply knowledgeable in their respective fields, and were prepared to work their way into new realms of creativity.

There is no substitute for adequate preparation. But if you work your way to the highest realms of knowledge in your field, if you earn a Ph. D. and go on to the most esteemed post-doctoral program, it still doesn’t guarantee that you’ll make startling breakthroughs in your chosen field. It means that you are at the top of your field, and you’re probably as smart as any of the other folks around you within that field, but it doesn’t assure that you’ll achieve the key breakthrough in thinking that turns you into the next Einstein, Monet, or McCartney.

What does? You, and you alone. There can be no guarantee. But if you have the background and are willing to try some new things, some new ideas, some new combinations—with the recognition that failure is possible—you may be ready for something truly creative. Nobody can give you the “aha! moment.” Nobody can define how it happens. Often it requires the ability to ask the right question, to make the right adjustment to an unexpected finding or situation, to put several things together in a way that nobody has ever put them together in the past. That’s the key to creativity.

What are the differences in forces behind one person who is highly creative and the next person who simply “goes along to get along,” just completing the day-to-day tasks without any true creative drive? Why does one photographer strive to create new, different, deeper imagery, while another photographer is content with producing good, solid imagery, but imagery that fails to set itself apart as creative and insightful?

In The Art of Photography I discuss creativity and intuition in the latter chapters of the book. I list five requirements for creativity: desire, thought, experience, experimentation, and inner conviction. I have no reason to change my mind about what I said in that book, and in fact, some of it bears repeating or further discussion here because I believe it is the core of creative thinking. In this book, I want to add another requirement: enjoyment. Go through the following six requisites, applying them to the innovators cited at the beginning of this chapter, and it’s easy to see how they all fit together. When you consider these people and others discussed between the covers of this book, it’s clear that creativity is not the realm of dullards. Only people who are bright and deeply engaged in their field, people with deep knowledge of their field, and people with a deep passion for their field will prove to be creative in that field.

Let’s look at these requisites for creativity, with special emphasis on photographic creativity, for these are the driving forces behind it.

DESIRE: It’s hard to imagine anyone being creative in any field—science, business, art—without a desire to go further than anyone else has gone, to dig deeper, and to come up with new insights. Creativity implies doing something new that has never been done before, and doing anything new is difficult. Are you willing to do the hard work, and do you desire to do the hard work that can lead to new or deeper ways of seeing?

Where does the passion to do something, new, different, better, deeper than anything done before come from? I am quite convinced this comes from within. It is unlikely to be forced upon you from the outside. You can be influenced, stimulated, and inspired by others, but it’s unlikely you’ll be pushed or forced into truly creative ventures by anyone other than yourself.

I often wonder if the most creative people are reclusive to one degree or another. In order to accomplish their cherished goals, do they have to go it alone? Perhaps studies have been done about this, but I don’t know of any, and I doubt that any such study would be conclusive. But it does seem to me that creative efforts are usually accomplished alone, or within a very small circle of collaborators. (This, to my mind, is something different from, say, thousands of experimental physicists and engineers searching for—and finding—a previously undetected particle that theoretically gives mass to many other particles. This finding has already led to a Nobel Prize for physicist Peter Higgs, who predicted its existence decades ago. The search for Higgs’s particle was a massive collaborative scientific effort, quite different from Higgs’s or Einstein’s individual insights and revelations.)

THOUGHT: Are you willing to put thought into your photographs before you start on any new project, or even before you release the shutter for each new image? Are you thinking of all the controls that you have at your disposal, each of which has a large effect on the outcome of the image? How much have you considered camera position, the exact location in space of your camera lens that will maximize the interesting compositional elements? Have you thought about the exposure of the image and the development of the negative if you’re shooting film, or the exposure and potential need for HDR if you’re shooting digitally? Have you considered the final image as you look at the scene; not just the scene in front of you and your camera, but the final photographic image you want to present to the viewer? This is akin to asking yourself how you want the photograph to look, which is the same as asking yourself what you want to say about the scene. How you transform the scene in front of your eyes to the photograph you place in front of the viewer’s eyes is your interpretation of the scene.

Are you aware of problems or distractions within the scene that can destroy your photograph? Have you thought of ways to eliminate those problems prior to snapping the shutter? You probably haven’t created the scene—whether its a landscape, portrait, architectural study, macro detail, or whatever—but you will create the final image. You have immense artistic leeway, but only if you choose to exercise it. And that begins before you snap the shutter.

Just prior to publication of this book, my close friend and longtime workshop colleague Ray McSavaney succumbed to lymphona cancer. In response to a letter I sent out to friends, another friend and former student recalled a session with Ray in the ghost town of Bodie during one of our workshops. After carefully setting up his 4×5 film camera on an interior room, Ray spent an extended period of time adjusting the setup—moving a chair slightly, adjusting his camera position slightly, and lowering or raising the camera on the tripod, each time inspecting the image carefully from behind the camera. After watching this slow dance for some time the student got bored and left the scene.

When he returned some time later, he found Ray taking down the camera, and asked, “Did you like what you got?” A smile slowly came across Ray’s lips and he said, “I didn’t make an exposure.”

The thinking process can be a double-edged sword. Along one edge there is the careful observation that Ray put into the potential setup, undoubtedly accompanied by his mental review of images he already had. Even after much alteration and preparation, the image fell short of Ray’s desire, so he walked away. This type of deep thought and reflection—followed by a rejection of the image entirely—is almost unheard of in today’s digital world, where it is more likely that each of the arrangements would have been another digital capture, with the best to be determined by comparison and editing later.

The other edge of this sword is the possibility that Ray was wrong. Maybe the image was a strong one, but he just didn’t see it at the time. Perhaps he should have made the exposure and decided later if it was worthy or one for the unprinted archives.

I feel that too little initial thought is involved in today’s digital world. On the other hand, I can see the potential benefit of making an exposure and deciding later if it is worth anything. I have noted in this book how I have discovered old, overlooked negatives years after I made them, and found some to be among my best.

In this case, however, my guess is that with Ray’s careful, analytic, and supremely artistic mind, he made the right choice.

EXPERIENCE: Experience can give you ideas and insights that you surely don’t have as a beginner. You can reach back into this trove of knowledge to help you with different or even similar situations, and acheive new and richer outcomes. On the other hand, experience can make you lazy, and you may end up doing the same things over and over because they’ve worked well in the past. If that’s what experience does to you, then you’ve used your experience to put yourself in a rut. Experience used well can be a great benefit; experience used improperly can be a great impediment.

EXPERIMENTATION: Any time you’re trying something new and different, you’re experimenting. Any time you’re not experimenting, you’re probably doing the same thing repetitively. Creativity requires some experimentation. You’ve got to get out of the rut of engaging in a routine simply because it has worked in the past. So ask yourself, how often do you try something new or different in a situation in which you’re already comfortable? If you don’t experiment with some new approach, some new way of seeing, some new way of thinking (even about old, well-explored subject matter), or some new way of digging deeper, you’re probably not creating any new imagery. Yes, it may be a new picture, but it may not be a new idea. You’ve got to explore new ways of thinking, new techniques, or new materials or equipment (see chapter 7). If you don’t, you are simply reinventing the wheel and will get nowhere on the road toward creativity.

I am always questioning my own level of creativity, or lack thereof. It’s easy to lay back and work the same way you’ve worked in the past in situations that are similar to those you’ve previously encountered, knowing that the result will be successful. Sometimes that’s the way to go, and trying something new and different will end in disaster, but once in a while you have to go out on a limb and try a different, experimental approach. If nothing else, this keeps your juices flowing, and it also keeps your interest level high.

Experimentation often ends up in failure. That’s to be expected. The famous lubricant WD-40 failed 39 times before its chief researcher came up with the successful formula on his 40th try. Are you willing to fail 39 times before finding success? Probably not. But it’s worth trying and failing at least a few times before you hit something successful. The problem is that most people hate failure so much that they’ll do anything to avoid it, including staying in the same rut that they consider success, but that soon becomes boring repetition. They won’t experiment. They’re afraid of experimentation because they’re afraid of failure. But just consider this: when you fail at a photograph, you’re probably the only person who will know it. So you may be disappointed, but at least you won’t be embarrassed.

INNER CONVICTION: You may be hesitant to go where you haven’t gone before. I surely was when I cautiously put my toe in the water of abstraction. This can only be overcome with an inner conviction that going there is simply okay. As I have noted, I received a critically needed push from Brett Weston that resulted from just seeing his abstract images. Maybe I would have gone there myself; I was close enough. But Brett’s images pushed me into the pool, where I’ve remained happily.

You may need encouragement from others. You may be able to do it yourself. But one way or another you must have the inner conviction to move forward, even in the face of disapproval from others. You have to believe in yourself and in what you’re doing.

You shouldn’t be a knucklehead about it, doing utterly stupid or useless things that everyone tells you are patently foolish. It’s worth listening to others. But you have to make the final decision. And if you feel that the unusual work you’re doing has some value to it, you must pursue it. Don’t be bull-headed about it, but on the other hand, don’t be a wimp when it comes to creativity. You have to have the inner conviction to go with your passion.

ENJOYMENT: Perhaps more than any of the five requisites listed above, enjoyment has to be part of the mixture. You can call it enjoyment, fun, enthusiasm, or any other appropriate word, but it all comes down to the same thing: you’ve got to love doing whatever it is you’re doing. You can’t force yourself to love doing photography; you simply have to realize that you love doing it. It’s fun. It’s rewarding. It’s fulfilling.

I’m sure that the great innovators I named at the beginning of this chapter loved doing the work they were doing above all else. They were engulfed in it, and couldn’t (or can’t) wait to get to it each day. It’s their passion. You don’t have to be as brilliant as Einstein to be innovative and creative in photography, but you do have to love doing it, and you have to be open to the other requisites listed above.

So let’s see how this can be applied to your photography. If you’re a good observer, a careful observer in the fields that interest you most, you’ll begin to recognize where and when the opportunities are, and where they’re far less likely to be. A street photographer quickly knows where the action is likely to be, and where there’s likely to be little or none. A fine portraitist will be someone who understands people, their thoughts, their characteristics, their body language, and the best way to interact with each person to a far greater degree than that of the average person. If you’re one who is drawn to people in that way, and likes to interact with people, it’s quite likely that you can make fine portraits, either in a studio setting or out on the urban streets, or in the lonesome roads and farmlands of rural America, or in foreign countries.

Perhaps you are not drawn to all people, but to specific types of people. Cowboys, for example, carry a romance for many people who are drawn to them not only for the work they do, but for the wide open spaces in which they do it and the total lifestyle that it represents. It’s a whole package. Above all, cowboys tend to draw photographers who want to depict the individuals who have dedicated their life to that type of work, individuals who are simply different from, let’s say, your typical office worker on the 35th floor of a building in New York, Chicago, London, or Buenos Aires. If you’re drawn to people working out in cattle country rather than those folks on the 35th floor, you would do well to get into the ranches where they reside, away from the big cities.

While this is obvious, it seems that a lot of photographers who dream of photographing cowboys don’t connect the dots. They live in cities themselves, and view the wide open spaces with a degree of interest, but also with fear and anxiety. They think they want to go to the country to photograph the cowboys but they’re scared to do it.

This is just one example of people who want to photograph a specific type of subject matter—any subject matter you can conceive of—but are restrained by unknown forces that they apply to themselves, preventing them from doing what they think, or claim, they want to do. I think it’s all phony. People who deeply want to do something do it! Those who claim they want to do something, but really lack the enthusiasm and inner fire, don’t do it. It’s really that simple. They’re fooling themselves about claims of real interest where none exists. You have to level with yourself about what really turns you on and what doesn’t; what you’ll push for to the exclusion of other important things, and what you’ll idly dream about if you had the time or money to do it.

I’m not a portraitist. I’ve made a few portraits over time, and even a few that I like, but it’s not my forte. Years ago at one of my workshops, an older gentlemen introduced himself by name and occupation during our opening introductions, and then added, “...and I like people in particular, but I don’t like people in general.” When he said that I nearly leapt out of my chair as if my team had just scored a touchdown. He had perfectly expressed my own thoughts, and I’ve stolen his words many times since then.

If you’re going to do portraits or street photography well, you have to be drawn to people. Maybe to specific types of people. I’m not. I don’t try to fool myself about that. I’m drawn to the land. I’m drawn to abstracts. I’m drawn to architectural subjects. I’m drawn to creating new, imaginary worlds through my composite images. I’m not drawn to people as photographic subject matter.

Creative, expressive photography is not simply the act of pointing a camera at something and clicking the shutter. Anyone can do that. It’s the act of truly saying something visually that makes others take notice. In order to do this, you have to discover what it is you’re interested in and what you want to say. And conversely, you have to recognize what doesn’t interest you, and identify the subjects about which you have little or nothing to say.

In the mid-1900s, the great street photographer Arthur Fellig, known as “Weegee,” developed a camera with an extended lens, which was actually a tube with a mirror in it set at a 45-degree angle. This allowed him to photograph a scene that was 90 degrees to his right, even though he was pointing his lens straight ahead. He would show up at crime scenes or auto accidents, and while it looked as though he was aiming his camera at the carnage in front of him, he was actually photographing the onlookers viewing the scene, who often revealed a variety of reactions from revulsion to outright glee. Fellig showed that such incidents were almost carnival-like in many ways, providing real entertainment for the gawkers. It was tremendously insightful, creative work. But it could only have been done by someone who first noticed the various reactions from onlookers at such events. Once again, keen observation and deep insight were key to his imagery.

Landscape photographers tend to “sniff out” weather and lighting conditions that are likely to produce good images. Ansel Adams lived half the year in Yosemite Valley for decades, but he didn’t photograph there on a daily basis. Although the cliffs were just as impressively high every day, the weather and lighting conditions varied greatly, and he recognized that. He photographed when ephemeral lighting and weather conditions were likely to yield a better image.

I had never been to Peru or Machu Picchu when I was first invited to teach a workshop there in 2009. So I initially asked, “When is the wet season, and when is the dry season?” Then I said, “I want to time the workshop for the transition period between the two.” I knew in advance that I didn’t want to be there when it was pouring rain all the time (making it tough to even take my camera out), nor did I want to be there when there wasn’t a cloud in the sky (when all the postcard pictures are made). I wanted to be there when conditions were in flux. I felt that would be the perfect time for some good photographic opportunities (figures 5–1 and 5–2). Observation and experience give you insights, and then you can let your intuition and creativity take over.

Figure 5–1: Rooftops in Fog, Machu Picchu

Atmospheric conditions, specifically clouds and fog, turn the remarkable Inca ruins of Machu Picchu into a dreamlike experience. On a clear day, perhaps in bright sunlight, the structures would still be quite striking and wonderful; seen through the mist and fog the scene takes on a thoroughly different character.

Figure 5–2: Sunlight Through the Mists, Machu Picchu

Even on a morning with no clouds, there was so much humidity in the air that a magical quality of light hung over the region like a gauze veil. The brief, unexpected period in which there were no clouds came to a quick end, as fog and clouds soon boiled up from the canyons and down from the high mountain ridges all around. That, too, was an ephemeral, dreamlike experience.

Like so many of us, I had seen many photographs of Machu Picchu before I went there. So I knew what I was about to see; that is, until I walked through the entry gate. The scene in front of me was so utterly different from any photographs I had ever seen that I was astounded. I felt like I had never seen a photograph of the place. It was magical. The mountainous, tropical-jungle setting overwhelmed the extensive Inca ruins set atop a nearly knife-edge ridge. The surrounding mountains would disappear before my eyes and then become visible again as clouds and fog moved through the area, sometimes sweeping upward from the deep canyon below, and other times cascading downward from the higher mountains that seemed to go on forever. It took several years of photographing there, for just a few days each year, for me to be able to fully take advantage of the rapidly changing atmospheric conditions. Eventually I put together a small set of images that most closely parallels my basic thoughts about Machu Picchu: that Machu Picchu doesn’t actually exist; it’s but an evanescent dream.

My initial questions about the timing of the wet and dry seasons, and my desire to work in the transition period between the two, were based on my experience with weather conditions that could be beneficial for good outdoor photography. Over time, such experience becomes so deeply entrenched in you that you really don’t even think about it. You just go for it. It didn’t take me a nanosecond to think of asking those questions; they were simply there. The transition period was the obvious time to go. Observation and experience over time led to intuition.

Similarly, although I have written about looking at lines, shapes, contrasts, and all the other compositional elements of a photograph, it turns out that when I’m setting up the camera, some of those concerns may be on my mind, but it’s more likely that none of them are. Most of the time a composition simply “feels right.” It can’t be any other way. My guess is that I’ve internalized my reactions so completely that little of it is conscious thought; it has become part of my subconscious procedure. It’s basically intuitive, not cerebral.

Perhaps later I can explain why I did what I did—why I set up the camera in exactly that location, why I chose a specific focal length, why I framed the image exactly the way I did, and all the other things that went into the exposure. But I know with certainty that I was actively thinking about and was aware of the light on the scene. I was aware of how light affected the scene, and if there was anything that needed to be (or could be) altered to improve the light.

I suspect that Ansel Adams didn’t give much compositional thought to Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico while setting it up. In fact, he wrote that he was working as fast as he could before the sun set, and after making the exposure, he went to turn his negative carrier around for a second exposure, but the sun set before he could do so. For Ansel, the composition simply felt right and he rushed to capture it. I doubt that Beethoven spent much time thinking “what comes after Da Da Da Dummm?” It was perfectly obvious, and was the only way to go. I doubt that Picasso spent a whole lot of time thinking about the compositional elements of his monumental, deeply haunting painting Guernica. All of these things were internal and unavoidable.

But let’s face it, nobody starts out like that. Einstein, Bach, Rembrandt, Jobs, and all the other greats of their respective fields achieved their status by knowing a great deal, observing a great deal, and putting a great deal of their insights into their work. Insight and intuition aren’t just there; they are products of observation, knowledge, and experience. You can’t be intuitive or insightful about anything you don’t know. You have to work to get yourself there.

I chose the several examples that start out this chapter because people like Einstein, Beethoven, and Jobs represent great insight, intuition, and creativity in science, art, and business. I do not believe the basic approach to intense creativity is different in any of those seemingly diverse fields. It always starts with a great deal of interest, a great deal of knowledge, and a few insights that others who were equally brilliant never saw. You don’t have to be as brilliant as any of them to connect a few dots in ways that nobody ever has before. And that’s often what creativity is: the simple act of putting together two or more well-known ideas in a way that nobody has ever put them together. The ideas were there, but nobody ever looked at them in relation to one another in that way. That’s creativity. But I doubt that it happens without a deep understanding and knowledge of the field.

Just as most people place obstacles in front of themselves that prevent them from doing things they want to do, or claim they want to do, I have found people who have a great deal of knowledge and insight into things, but they never move forward because they’re afraid to apply their own well-founded intuition to the task at hand. They feel that intuition is silly and often wrong. It is unscientific. It is something to be overcome with any number of carefully considered measurements before proceeding.

Insight and intuition are attributes to be relied upon, not avoided. Small insights can lead to small breakthroughs, and sometimes even large breakthroughs. If or when you have a “feel” for something, it’s worth going for it.

Have you ever met people who display uncanny intuition about other people? They seem to know who is good, who is honest, who can be trusted, and who cannot be trusted. These are people who have simply observed and experienced human behavior for so long that they can see through the many veils we all hide behind. These intuitive folks are not considered geniuses like those listed at the beginning of the chapter, but they are as keenly observant as those listed above, and have parlayed those years of experience into valuable insights into other folks’ characteristics. But even this doesn’t come without work, even for those intuitive folks who never thought they put any work into it; they just internalized it all along the way.

If you are already doing photography and reading this book, chances are you have already invested a good deal of time in your photography. Photography is important to you. You love doing it, and you are constantly striving for better results, not just to impress your friends or family, but primarily to satisfy yourself. I’d recommend that you start to use more of your intuition wherever you can, even where you have generally thought you couldn’t or shouldn’t.

Let me give you a couple of small examples from my workflow that may help free you up in terms of trusting your intuition. In the darkroom, when I am printing, I use a much more dilute developer than Kodak recommends. Kodak recommends Dektol diluted 2:1 with water. I dilute it 5:1, but I also develop for an extended time. Kodak recommends 1 1/2 to 2 minutes as standard developing time, and I develop for about 5 minutes. I never time it, I just do it. Students at workshops over the years simply don’t believe that I can tell when five minutes are up, so they first assume that I must be counting out the time. I point out that during my printing demonstrations, while I’m agitating the print in the developer, I talk to the students about what to look for in the developing image, what I’m doing, what I plan to do next if the image still isn’t satisfactory, or any of a number of other things. I can’t be counting out the time while I’m talking about other things.

So they turn to the next means of sleuthing out what I’m up to: they surreptitiously time the full development, obviously skeptical that I’m really developing for five minutes. Amazingly, they find that I’m within seconds of the stated five minutes. I know that I have a feel for that time, so I just do it. It’s intuitive. I tell students to loosen up and try it themselves rather than start a timer as the print goes into the developer. If it’s not intuitive at first, it probably will be in a short time. The benefit of my procedure is that I get repeatable results, so it’s not just a silly thing; it’s essential for the quality of the prints I produce. But I do it intuitively.

Another quick example: I don’t use a typical 1-degree spot meter to measure light levels in the field. I use a broader 7.5-degree semi-spot meter because it has greater sensitivity in lower light levels. I can intuitively see the range of brightness in a scene, so I don’t need to point the meter to the extreme shadows and highlights. I need the meter to determine the basic brightness level, but not the brightness range. I rely on that intuition, and I’m accurate.

Too many photographers feel they have to measure everything. They are scared to rely on even the smallest bits of intuition like these two examples. If you are too afraid to use your intuition for small things like this, you’ll never use it for anything bigger. In short, you won’t use it at all. That’s a loss that you’ve imposed on yourself. Therefore, only you can power past these impediments to using your intuition. Loosen up. Use your intuition wherever and whenever possible. It’s an extremely important tool.

Upon reading the material presented so far, some readers may feel that unless you’re spending your entire life doing photography you may as well forget about doing any creative work in photography. That’s certainly not the case. You don’t have to spend all of your waking hours thinking about or doing photography to be creative or to apply insights to your work. What counts is not the time you spend with photography, but the thought you put into it. In chapter 3 I discuss the differences between the options of a photographic hobbyist versus a professional. Let me return to those ideas and expand upon them, because it’s important to recognize that you don’t have to be a professional photographer working at it for a living to be creative; in many ways the hobbyist could be in a better position than the pro.

A hobbyist can give some thought to his latest projects at any time. He does not need to think about generating income with his photography, so he’s free from worrying about making images that will sell well. The pro is often too occupied with the current job and the next job to give personal work much thought. Of course, professionals can, and often do, bring real creativity into their work, but so can amateurs. I know of sports photographers who have put some wonderful creativity into their work. Maybe the time lapses between sports events give them more time to seriously think about doing a better job professionally, and maybe they have more time to do some of their own work between the sports events they’re covering. From what I’ve observed, professionals with studios—specifically storefront portrait studios—appear to have the least amount of time to devote to thinking about creative ideas.

As I explained earlier, the professional architectural photography I did for about 14 years was quite lucrative, but it was also very sporadic. Due to the fact that I had significant breaks between assignments, I was able to devote a lot of time and thought to my own photography. An amateur may be in the same position while earning his keep in an entirely different field. You could be like the American composer Charles Ives, who became quite wealthy as an insurance man and devoted time to writing his music on the side. He did not need to earn money from the music itself, which freed him up to pursue his own creativity as he pleased. While critics have praised his music, the public has been somewhat less enthusiastic. But regardless of the response he received, he did what he wanted to do as a pure amateur. There are some good lessons to be learned from his example.

I frequently have short stretches of time to do some photographic work and planning, but not enough time to get into the darkroom for a full session of black-and-white printing. Instead, I spend time poring over contact proofs—the direct, straight prints from the negative—to see which ones are worthy of printing. I use cropping Ls to see if cropping one or two edges or a larger portion of the full negative improves the image. Sometimes I rotate the negative to look at it from an angle that is different from the original orientation of the camera, often finding a different and stronger dynamic when the image allows such rotation. I consider the benefits of raising or lowering contrast, overall or section by section, perhaps making the entire image lighter or darker than the contact proof. I contemplate any other alteration that could produce a fine image. Basically, I lay down plans for how to work on each specific negative when I have the time for darkroom work. This turns out to be very valuable time that puts me on track to produce the print I want, and saves enormous amounts of time and money in the darkroom.

For my digital photographs, I work through my most recently downloaded RAW files, searching for those that show real possibilities. Then I work on them in both Lightroom and Photoshop, moving toward a final image. If the progress I see using Lightroom doesn’t put me on a high enough plateau, I drop the image. I continue with those that show promise, and usually end up doing some amount of finishing work in Photoshop.

Similarly, you can devote some of your idle time to thinking about what you’ve produced photographically, what you may want to do in the future, and how you can improve on the things you’ve done in the past. That’s not wasted time. To the contrary, it’s extremely useful, productive time that will prove its value the more you engage in it.

Beware, however, that digital imagery may possess within it a problem not present in film photography. As memory storage changes and improves, today’s memory systems may grow outdated, just as floppy disks, zip drives, and, more recently, CDs have been cast into the dung-heap of history. So older imagery may have to be updated to stay accessible. But this raises the question of whether you update all of your past imagery or just your most important imagery. How can you determine which is the most important imagery? As I’ve already noted, my experience has been that some old, overlooked negatives are among the best I’ve produced, but I failed to recognize it for years. With film, I can access everything I’ve ever done at any time. That luxury may not be readily available as digital processes evolve.

As I pore over new or old contact proofs that could possibly turn into really wonderful images, I look beyond the image seen in the proof print to the possibilities inherent in the final image. Sometimes the two are vastly different. In the final image, I may have cropped out meaningless areas that seemed worthy when I framed the image at the scene, but no longer strike me as being needed. Perhaps I’ve dramatically raised the contrast of the remaining portions, or made other alterations that transform the bland contact proof into an exciting final image. Keep in mind that the contact proof is simply a straight record of what is on the negative, nothing more. This is the final stage of transformation from the original scene that caught my attention, to the negative (or RAW file) that starts the photographic process, and then to the final image.

The question of where creativity comes from is probably impossible to answer in a precise manner. Nobody could determine how Einstein came up with the thought of how things could look to a photon traveling through space at the speed of light (which is what photons do), perhaps not even Einstein himself. The same imponderable would apply to how Beethoven went so far beyond the music of his day.

I’ve experienced moments of inexplicable photographic creativity a number of times over the years. Following are stories of four different experiences resulting in photography projects that were different from anything I had done before.

On January 20, 1993, a fierce windstorm blew along the Pacific Coast from Oregon through Washington, uprooting tens of thousands of trees. It hit our 20-acre forested property in the North Cascade Mountains north of Seattle, with a microburst uprooting so many trees that we were forced into a tree removal operation that took out 17 truckloads of uprooted trees. In the clean-up that followed, I found a small log that was no more than 6 feet long with a string of tightly wound burls along one edge, and I set it next to the trail I was rebuilding to photograph later. Strangely, although I passed that small log nearly every day on my dog walks, I failed to pull out my camera to photograph it. I basically ignored that small log for years, not even studying it for photographic potential.

During those years I was deeply engaged in a major local environmental battle, leading a group of local residents and other concerned citizens fighting a proposed sand-and-gravel mine and hard-rock quarry down the road from my home. We won every major environmental legal battle in front of the county hearing examiner, a pseudo-judicial position created by the county to decide land-use conflicts. Ultimately, he denied a permit for the project. But the county council illegally overturned the hearing examiner’s decision, and granted the company its permit. We won every legal battle, but we lost politically.

I initially photographed this as a horizontal image, but I realized that if I turned it 90 degrees, it looked like a head cut in half, with the brain removed from the skull. It helped make the statement I wanted to convey stronger.

I was teaching a workshop in Norway just prior to the county council’s decision to grant the permit, knowing that we were about to be trampled by the politics and enormous amounts of money behind the project. One night, while reading in my room prior to going to bed, I looked up at the wall behind the desk and said almost out loud, “I’ve got to photograph that log!”

At that moment, I knew with 100-percent certainty that photographs of the burls on that log would express my anger, frustration, and rage about being bulldozed in this long-running environmental battle. I cannot explain how I suddenly focussed on that log while sitting 5,000 miles away from it, nor can I explain my absolute certainty that it would supply the required imagery to express my feelings. I simply knew I had to photograph that log, and that it would give me the expression I so desperately needed. It turns out, it worked perfectly (figures 5–3, 5–4, 5–5, and 2–6). I call the series “Darkness and Despair.”

Generally I look to landscapes, abstracts, and most other potential imagery for their beauty and general uplifting qualities. Here I was seeking imagery that would express the darkest and most negative of emotions. In essence, it went against anything I had ever done. But deep negative feelings can be as valid as deep positive feelings, and these images had to be made.

So I photographed that log in 1999, more than six years after finding it, and just after the Snohomish County Council permitted the project. I photographed for about two hours on each of three days; under soft, cloudy lighting conditions; using my Mamiya 645 medium-format camera with extension tubes for close focus. No image covered an area of the log more than five inches on a side. Due to the macro focussing, much of the area within each image was out of focus. In the printing, I blacked out most of the out-of-focus areas, printed much of the imagery to very dark tones, and bleached back the highlights to whites and near-whites. All of the images are printed at 16×20 inches.

The thought in my mind behind this image was the downward turn that I was experiencing as political forces first tried to alter the legal hearing over the gravel pit project, and in the end, overturned the legal decision against the project, granting the company its permit.

Many viewers see a badly distorted, partially squashed face in this image, which was precisely my intent in creating it. In the end, we were crushed by the politicians who seemed to have patronage, not the law, in mind. But, of course, they are politicians.

In one sense, the images are impressionistic, with little in sharp focus. But while most impressionistic painting gently pushes you back from the image in order to see it as a unit rather than just the seemingly arbitrary brushstrokes, the “Darkness and Despair” images tend to push you back violently with their deep blacks, shrill highlights, and tightly wound forms.

The images gave me the expression I wanted, yet the series is a creative departure from much of my photography.

Titus Canyon is on the east side of Death Valley, and it is drivable via a 26-mile one-way road that narrows to a single car width toward its lower end. Within the deepest, narrowest stretch the towering walls are studded with small outcroppings of smooth translucent rock, which upon close inspection, looks like the inside of a geode. The smooth rock, however, is weathered, and while it remains quite smooth to the touch, its transparency is marred by the hazy patina that weathering has given it.

It would not be easy (and it would certainly be illegal even if it were easy) to go in and polish those outcroppings to achieve the transparency necessary to see the brilliantly colored, agate-like forms clearly beneath the exterior fuzziness. But upon seeing those forms and colors for the first time through the hazy surface rock, I quickly realized that all I had to do was wet the surface to give it a wondrous transparency.

Fortunately, I had a full canteen of water with me, so I took a full swig of water and sprayed it out onto the smooth rock surface. Voila! Suddenly the haze disappeared and the surface became transparent, allowing the forms within the rock to be seen with brilliance and clarity (figure 5–6).

I now take students into Titus Canyon with me on my Death Valley workshop, telling them to be sure to bring at least one full canteen of water with them. They think I’m warning them about staying hydrated in a very hot location, but it’s really to give them the means to better photograph these remarkable outcroppings in their most brilliant state.

Here, once again, is a creative way of putting two disparate things together: photography and rock polishing. “Spit photography” isn’t exactly the same as rock polishing, but it served the purpose just as well. Within minutes—sometimes within seconds—the water evaporates, and with it so does the transparency it imparts. You have to work fast under the circumstances. And best of all, there is no temporary or permanent harm done to anything in the process.

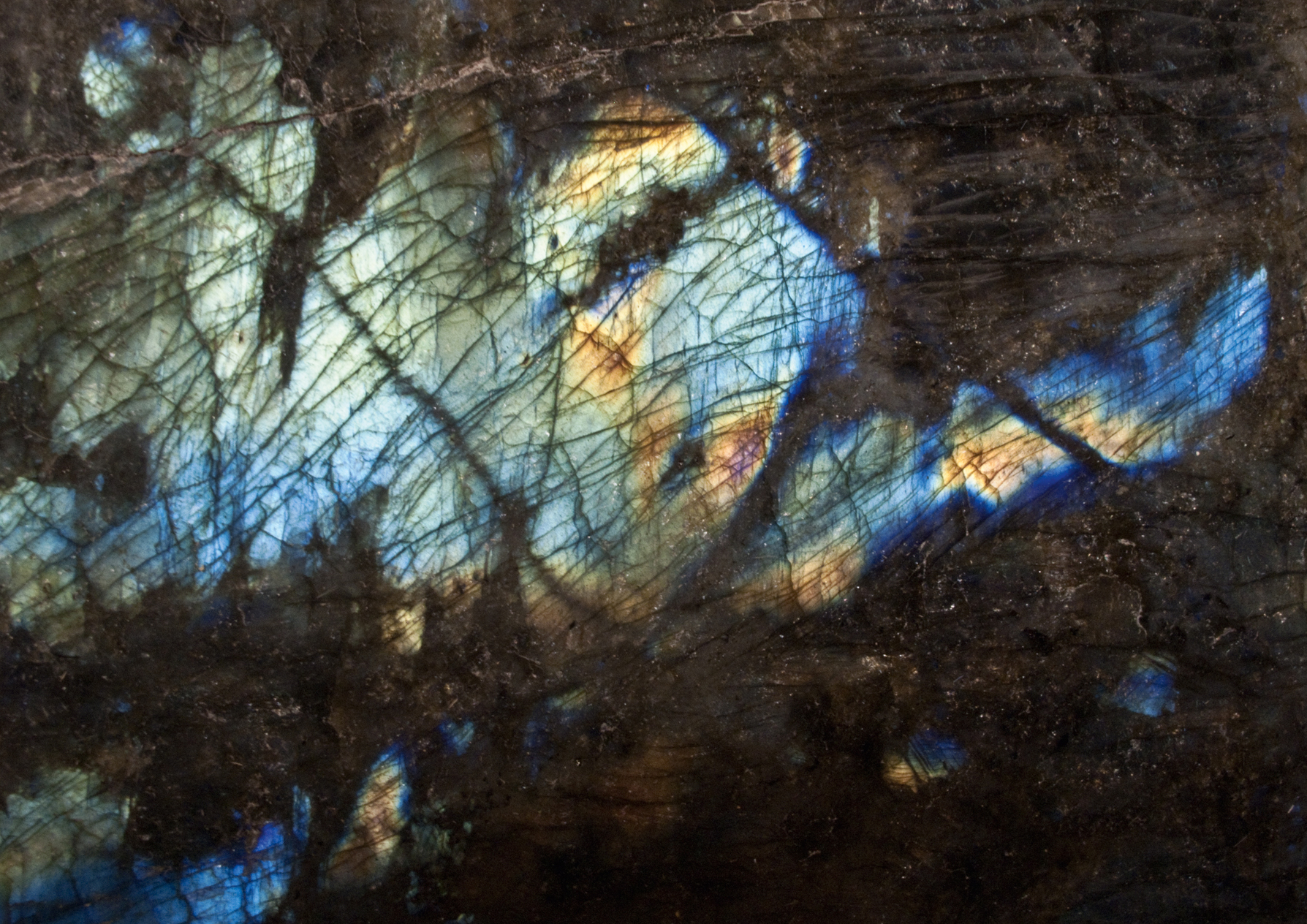

Figure 5–6: Nebula, Titus Canyon, Death Valley

Pouring some water on the nearly horizontal surface of this smooth rock made it almost transparent, allowing the underlying crystalline structure to be seen in its full glory with all the vivid colors and flow of form unobstructed. It reminded me of the fabulous astronomical photographs we’ve all seen from the Hubble observatory of nebulae within our own Milky Way galaxy.

Now, I have to admit that spit photography in Titus Canyon will never be recognized on the same level as Einstein’s Theories of Relativity for creative genius. But I’m not trying to compete with Einstein. Nobody can. I’m seeking small bits of creativity wherever I can, and I think that could and should be the goal of every serious photographer.

As I am writing this book, a whole new set of creative photographic imagery is unfolding to me. Again, it’s strange and unexpected, but hey, who cares where it comes from? If it’s there, take advantage of it.

If you look at the images first, you will probably be utterly confused by what you’re looking at (figures 5–7, 5–8, and 5–9). Good! That’s my hope. But it is also my hope that the imagery is interesting enough that you either try to guess what you’re looking at, or you simply enjoy the imagery as something of mystery and beauty. If that is your reaction, then I have succeeded. If you turned the page, wondering what’s next, then I failed.

Within the glistening spectrolite of this remarkable stone, any number of colors and forms can be discovered. If you move, some colors and forms may disappear while others emerge. It’s like an interactive art project, so that as you move, it changes. And as the light source moves, it changes. In this image I saw the edge of a gloved hand, with the thumb slightly below the index finger and the rest of the glove behind it.

Just as the wetted rock outcropping in Death Valley reminded me of a nebula, this elegant blue form stretched across the image reminded me of an image I saw of the aftermath of colliding galaxies, where one had been pulled apart by the gravitational tidal effects of the other.

Now for the explanation. About six months ago my wife and I went through a partial remodel of the three bathrooms in our home, tearing out old cabinets and formica counter-tops, and putting in new cabinets and polished stone counter-tops. One of the stone pieces we purchased possesses brilliant fluorescent crystals within it, which are visible only when the direction of the light hitting it and the direction of the line of sight from where you are looking at it (always two different directions) align properly. Then, and only then, do the crystals shine forth in brilliant blues, golds, coppers, greens, and an array of other efflorescing hues.

I was so taken with the qualities of this particular counter-top stone that I asked the workers what they did with the oval stone pieces cut out for the bathroom sinks and the rough scraps from around the edges. I was told that they throw them away. I replied, “No, not these scraps. I want them all.” I paid for it, so they gave them to me. I had no idea what I would do with them, but I was entranced by the sheer beauty and surprise of it all.

After having our new countertops installed, and now possessing some of the quite brilliant scraps, I returned to the showroom asking if I could have scraps of the same stone cut from other such projects, assuming that they would throw those away as well. They readily agreed to hold those aside for me, rather than just tossing them out. So I started collecting more, still not knowing what I would do with them. I considered making a tabletop, but at 3 centimeters thick and 40 pounds per square foot, a small 3×3-foot tabletop would weigh 360 pounds, making it almost immovable. So that idea was discarded.

One section of labradorite was especially unusual with its intersecting lines of spectrolite crossing one another at nearly 90-degree angles, another fascinating aspect of the internal structure of this rock.

With the weight as a severe restriction, I finally settled on the idea of making a mosaic on a walkway around one side of our home. It would be much like an interactive art installation, in which the so-called spectrolite would show up or disappear as you moved around the mosaic and as the direction of light changed during the day.

I bought grinding tools to smooth and polish the rough edges for the mosaic pieces, partially to prevent cutting myself on the sharp edges, but also recognizing that the front edges of the mosaic pieces would be visible, and so would some edges within the body of the mosaic. While grinding just days before writing these words, it suddenly and perhaps belatedly occurred to me to photograph the brilliant spectrolite within the stone.

I’ve just begun, and I’ve discovered that it’s difficult to place my digital camera at the proper reflective angle to photograph the spectrolite at its most brilliant without capturing my shadow or the shadow of the camera in the image, or catching the reflection of some distracting object in it’s mirror-like, polished surface. I may have to look into lighting I’ve never used in the past, and do not own (like softboxes, for example), in order to fully bring out the forms and brilliant colors I wish to show. But in this preliminary state of unfolding photographic ideas, I’m also thinking of making very large prints, which may be highly pixelated. Normally I would avoid that like the plague, but in this case, it may work spectacularly—a form of pointillism where you have to step back to see the image, while up close it may break up into a mosaic of tiny colorful squares.

Because the imagery is so thoroughly abstract, I have remarkable leeway. Are the colors accurate? So far, they seem to be quite accurate to me. But what if they aren’t? Who cares? It means little to have accurate colors when the imagery is so utterly impossible to grasp without an explanation of what you’re looking at. Some viewers may initially think these are photographs of stained glass with light coming through it. Some may see them as Hubble Space Telescope views of a nebula. Of course they aren’t; instead they are reflected light off of some extraordinary polished stone. But without an explanation, viewers may have all sorts of ideas about what these images are. That’s really wonderful to my way of thinking, and hopefully to yours as well.

I’m experimenting as I’m going. This is all new to me; I’m just at the beginning. What you see here in this book is little more than the start of a new project. At this point, as I write these words, I have no clear idea of where this will end up, but I’m wildly excited about the journey I’m just embarking on. I’m having a great time with this unfolding project that began as a partial bathroom remodel with no thoughts of anything remotely photographic.

On October 23, 1978, I was exiting the 101 Freeway two blocks from my home in Agoura, California, when I looked across the road and saw the start of a fire in an empty lot covered with dried grass. It was a day of hot, dry, 70–100 mph Santa Ana winds from the deserts that rake Southern California in the autumn, turning it into a tinderbox. What I saw was the start of the Agoura-Malibu fire that burned 25,000 acres in 24 hours. I lived just north of the freeway, but the fire started south of the freeway and winds were pushing it southwesterly, so fortunately, I knew my home was in no danger.

Following the fire, I would take my dog for a walk each morning in the burnt area, carrying my camera equipment with me and photographing an eerie, charred, black-and-white landscape. I would expose just one or two negatives during each outing, often taking only one or two sheets of film with me. I was having fun walking my dog; the photography was an extra highlight.

Somewhere along the way, perhaps by the time I had exposed 80 or 90 negatives, the thought occurred to me that I had a distinct set of images that were completely different from my other landscapes. Furthermore, I had a story. It was a story of death, but one that would be followed by rebirth, for the plants of the region make it a “fire ecology,” which actually depends on fire for seeds to sprout. Suddenly, the random photographs made on the dog walks became a project, a story, one that now needed an ending.

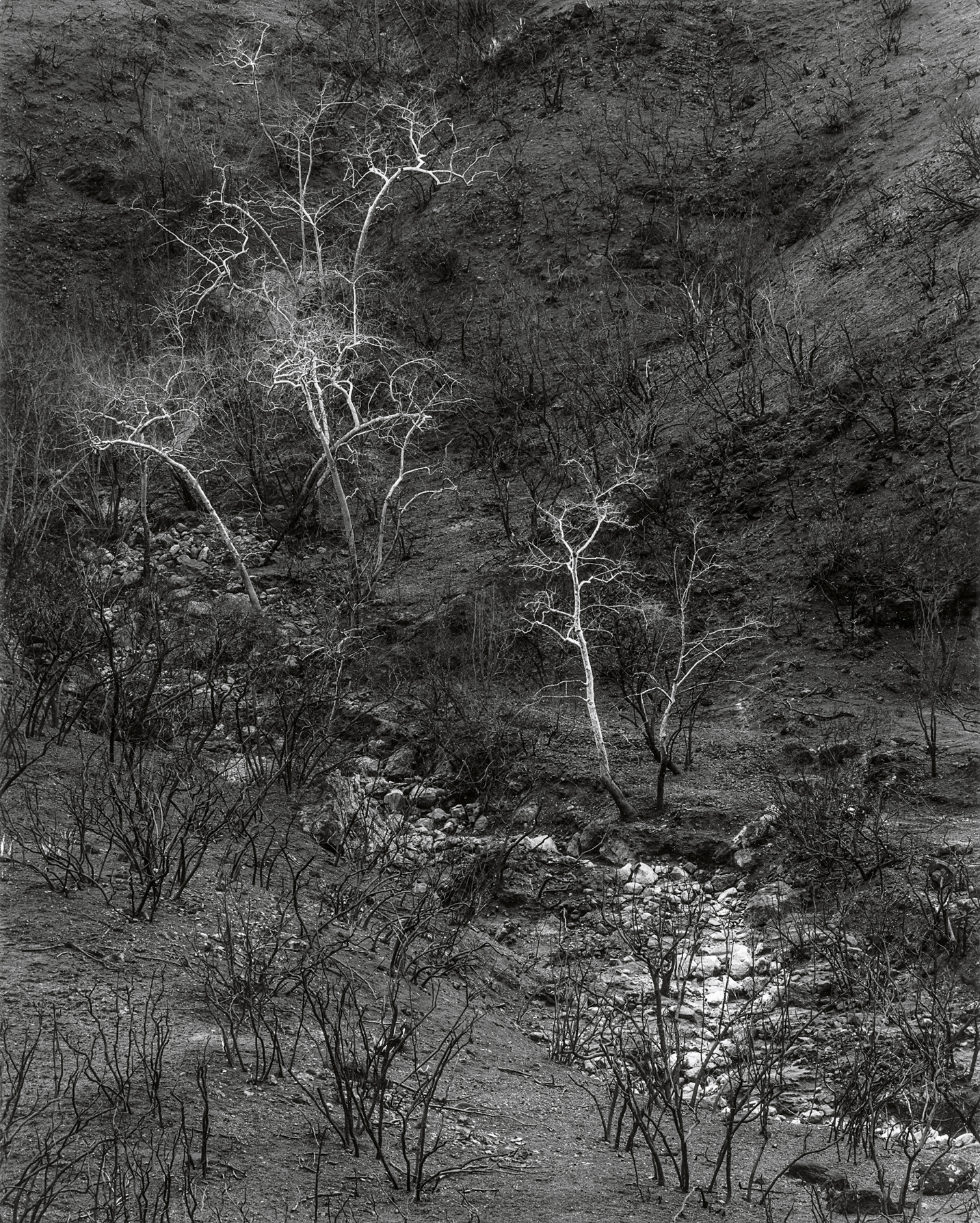

Weeks later I found the ending I needed in a cluster of mullein plants growing out of the charred soil. Ten of the images became my limited edition “Aftermath” portfolio, showing the aftermath of the fire—first the death of the land, then the ensuing rebirth (figures 5–10 and 5–11).

Once again, this is different from anything I had done before that time, or anything I’ve done since. At first, it was simply a different landscape that was also convenient to where I lived. It was a good area to let my dog run around at will, while I played with him and looked for a photograph here and there. Only toward the end did it become a serious photographic project.

In addition to these instances in which I’ve explored new subject matter or techniques, I’ve experienced other unexpected moments of creativity that I’ve discussed elsewhere in this book. I used the very dilute developer (which I learned from Ray McSavaney) and a totally new approach to exposing negatives to achieve my initial slit canyon images. The images and the technical methods I used to create them were completely new. I used the same technical methods to then open up another new body of work, the English Cathedrals. I later created a combination of negative developing techniques—my so-called two-solution developing technique—to yield even more from a negative exposed in an exceptionally high-contrast situation. Other major and minor creative acts have come along during my years in photography.

Who knows where creativity comes from? But you can’t get there if you close your mind off from it. You have to have an open mind and let things as seemingly unrelated as a bathroom remodel inspire a photographic project, or turn a walk through a burnt landscape into a photographic project, or photograph tiny wood burls on a log as a source of emotional expression. If you’re open to it, almost anything can turn into a worthy photographic project. Free up your mind to the unexpected, and you’ll find creative ideas where so many people have looked, but none have seen what you’re seeing. As I have already said, some creative leaps come from little more than putting together two or more well known ideas in a manner that has never been explored previously.

Creativity abounds everywhere, but always comes from deep knowledge and involvement. My wife, Karen, is a really fine cook (she’d never admit it, but she is). Often when we have guests over for dinner, one of them will ask, “What did you do to make this?” It’s delicious, and they want to do it themselves. All too often Karen replies, “I don’t know.” She’s not trying to avoid answering; she simply doesn’t remember.

She has such a storehouse of knowledge and experience in mixing spices and other ingredients together that she simply knows that a little of this and little of that will end up as a really delicious combination. Her cooking creativity flows out of her so intuitively that she does it without making the mental notes of what she’s done. Unless she were to consciously write down each step, listing each new ingredient and the amount of each, she probably couldn’t produce the same meal twice. Each one is a creative endeavor. And I have no objection to that!

Figure 5–10: Silver Sycamore Trees in a Canyon

As twilight settled in, a line of sycamore trees standing beside a seasonal stream stood out like little fluorescent tubes against the charred ground surrounding it. None of the trees were killed in the fire, which swept through so quickly that it merely blackened the lower portion of the white bark without harming it.

This photograph of lush new growth just starting to spring out of the ashes represented the end to my story of the death and rebirth of the land. Like most of the others, this image is simple and sparse, perhaps even a bit like a visual Haiku.

Figure 5–12: The Sunlit Bridal Veil (courtesy of Clay Blackmore)

A spontaneous moment, when a gust of wind blew the bridal veil above the couple. Blackmore instinctively clicked the shutter to quickly record the unexpected.

A wedding photographer is generally one who photographs one wedding after another, catching the obligatory images of the bride, the groom, the bride and her family, the bride with her bridesmaids, the groom with his family, the groom with his best man, the moment the vows are made in front of the officiant, and the other expected wedding shots. But, like any other field of photography, there is room for real creativity here as well. Much the same can be said for portraits, which are usually done in a studio following well-known guidelines.

Clay Blackmore is a Washington DC-based wedding and portrait photographer who has gone against the grain, putting real creativity into his work in the process of building a national and international clientele. He does most weddings in color, with some black-and-white infrared for extra punch. Beyond that, he has fun with photography, engaging in things that most commercial photographers would rarely think of doing, even after an exhausting day of commercial work. His success is based on loving the work he does and loving the people he works with. With an approach that revolves around “pose, light, refine, and then shoot,” he says he can begin to work from the heart. “I simply don’t think; I feel.”

One of Blackmore’s favorite photos is an infrared image of a bride and groom walking on the beach in Laguna, California, the day after their wedding (figure 5–12). “You need to feel relaxed to create magic, so that’s why we photographed the couple the day after their wedding,” Blackmore says.

Figure 5–13: Faces and Flowers (courtesy of Clay Blackmore)

Contrasting the beauty and soft skin tones of the models with the saturated colors of the flowers, Blackmore created an image that is design-oriented, eye-catching, and almost abstract all in one.

Using a Canon 1DS Mark II adapted to take infrared images, and a 14mm wide-angle lens, Blackmore worked at high noon, with direct sun presenting a major challenge. “Instead of competing with the bright sun, we joined in,” Blackmore says. A strong Q flash off-camera, dialed up to full power, was the answer. He set the camera to 125 at f/16, and placed the flash six feet away.

“We started with a few posed images around the water’s edge, then we encouraged the couple to walk, laugh, and love. We began capturing the spontaneity between them,” he says. “We went low to shoot up toward the sky, creating dramatic backlighting. Just at that moment, the wind picked up the veil and WOW! A few seconds later, it was all over. The moment was there; we captured it. And then it was gone. That’s the beauty of photography.”

Blackmore was prepared. He knows that the veil of the bridal gown is one of the iconic symbols of a wedding. When the wind blew it into the air, he acted. He reacted instinctively; he didn’t think about it. In a way, it’s much like a basketball player working with teammates on a fast break—it’s fast, it’s in real time, and it’s utterly instinctive. At the same time it’s totally creative. Blackmore saw the moment and reacted.

The sunlit veil is the obvious attention-getter in the image. But the kissing couple ties it all together in the most perfect manner. It makes a wonderful statement, and it does it with extraordinary pizzazz.

As Louis Pasteur noted, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” This quote applies perfectly to Blackmore’s image, and in so many ways to any fine image, from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s many celebrated Decisive Moment images to Edward Weston’s Pepper #30 to any other great image in the history of photography. It comes from a person looking, seeing, and instantly recognizing a superb situation. It’s not just being in the right place at the right time; it’s being in the right place at the right time, recognizing it, and responding quickly.

Another one of Blackmore’s favorite images was taken during a photography course he was co-teaching with his former mentor, Monte Zucker (figure 5–13). At the end of the course, Blackmore wanted to create a finale image to dazzle the crowd. He saw a bag of papier maché flowers nearby and had the spontaneous idea to lay two faces side by side, in opposite directions, surrounded by the flowers. Blackmore shouted, “Monte, come up here and join me, I have an idea.” They began arranging the models and carrying out Blackmore’s vision.

Blackmore had the idea, and together they were playing around with it. “We were really hamming it up to the audience,” Blackmore says. The two of them were on stage, so the large audience could not see exactly what they were doing. “It was a show. However, once the image flashed on the screen, I think we were as surprised as the 400 people watching the screens. It was exactly what we wanted: faces, and yes, feelings.” Sometimes the best photos can come from unexpected moments when you’re just having fun, Blackmore says.

This image is a perfect example in which intense coloration works perfectly because of what the image is. This is not a case of supersaturated colors being inappropriately employed. Rather, intense colors are used appropriately for an image that straddles the border between pure design and abstraction, yet is held together by the realism of two young, beautiful women. (It’s unlikely to have worked well with a couple of grumpy-looking old men. So the entire concept had to be carefully thought through for it to be successful.) The choice of colors enhances the image, putting a smile on the viewer’s face. Furthermore, you can trade virtually any color with any other, and the image would still be successful, and would still attract your eye. But also be aware that in the area of pure realism—the models’ skin tones—the colors are subdued and realistic.

Another example of creativity in an unexpected moment comes from Pei-Te Kao (pronounced Pay’-tah Cow), a student and friend of mine. Not long ago she boarded one of the ferry boats traveling across the Puget Sound in the Seattle area. It was dawn, and still quite dark. As the ferry left the dock, she wondered what would happen if she aimed her traditional film camera at the lights surrounding the dock and in the nearby area. Of course, it would require a somewhat extended exposure, more than a second long. With the ferry boat engines pumping to the maximum extent, it would matter little if she placed her camera on a tripod or held it in her hand because the ferry boat was shaking quite perceptibly.

Under such circumstances, there are likely two thoughts that could go through your mind. The first is that there’s no point making an exposure because it will be out of focus. After all, Pei-Te had learned the importance of sharpness in photography, so making a hand-held photograph from a moving (and shaking) boat would be senseless.

The second thought is simply to try and see what happens. Most people stop at the first thought. Not Pei-Te. She considered both options, and decided to see what would happen. (Of course, today most photographers use digital cameras, so they can get instant feedback, but Pei-Te uses film, so there was no instant feedback. The results would have to wait for a later time.) The resulting image is a very fascinating set of squiggles and lines, which would be totally confusing and completely abstract if you had not already been told what you’re looking at, but it makes sense once you learn what it is (figure 5–14).

How often have you thought about making a photograph, but talked yourself out of it simply because you thought it wouldn’t work? I’m embarrassed to say that I’ve probably done it too many times, but I can also say that I’ve pressed ahead a few times as well. This is the essence of experimentation that can lead to lots of disasters, but also to a few surprising triumphs.

Figure 5–14: From the Ferry Boat (courtesy of Pei-Te Kao)

Taking a gamble to see what would come of photographing lights on the receding dock from the deck of a boat as it left the dock, Pei-Te Kao was rewarded with a fascinating abstract image of moving lights in an extended exposure. Too few photographers are willing to take the chance at something new, something different, and perhaps something of interest to an unknown audience.

The photographs from Clay Blackmore and Pei-Te Kao are examples of creativity in areas of photography where few people expect or strive for creativity. This should be proof that creativity is hidden within any field of photography, and probably within any field in life, artistic or otherwise. It’s up to the creative mind to unlock it and set things off on a new road, one never previously traveled. Creativity stems from you, the creator, not from the subject matter at hand. That’s why some photographers are more creative than others, some artists are more creative than others, some scientists are more creative than others, some businessmen are more creative than others, some salesmen are more creative than others, and some teachers are more creative than others. The list goes on because creativity can be pulled from any field whatsoever. It’s up to you to do the job as told and expected, or to invent new and innovative ways of doing it that may be far better, far more appealing, far more productive, and far more interesting to you.

In order to do insightful, creative work in any field you have to be thoroughly grounded in the field of endeavor, and you have to have put a lot of thought into where you want to go beyond the norm. All the iconic people who are highlighted in the beginning of this chapter had a great deal of knowledge in their respective fields. But don’t get discouraged if you think that you have to be a Beethoven or Einstein or Steve Jobs to do outstanding work. You surely have to be at the very top of your game to do work as innovative as those folks, but you don’t have to be a genius to do extremely good work. You can accomplish virtually anything you can think of doing, if you:

can think of doing it;

learn what is needed to do it;

enjoy doing it;

do it with enthusiasm; and

put time, thought, and effort into doing it.

Notice that being a genius is not one of the requirements. I fully subscribe to the concept I once heard from a high school teacher who said, “There are three components to success: talent, hard work, and enthusiasm...and you can make it on just two of those attributes as long as enthusiasm is one of the two.”

That may be the most profound insight I’ve ever heard about success. I can’t see how anyone can achieve success at anything without having unbounded enthusiasm for doing it.

Learning the ins and outs of exposing and developing film and making prints in the traditional darkroom, or learning the ins and outs of digital capture and Lightroom and Photoshop (or its various equivalents), is not a terribly difficult task. Lots of people understand those things. As you’re learning the basic skills of photography you have to monitor your level of enthusiasm. If you’re learning those things and wanting to learn more, play with them, experiment with them, and think more about them, and you’re enjoying the entire process, you’ll do well. It’s inevitable.

When you go out with your camera in hand do you set a goal for the number of photographs you want to make? Do you have a minimum number of “good images” you want to nab in a day’s outing, or in a week, or however long your trip may be? Or let me ask these same questions another way: How important is it to you to expose images during your outing?

That last question may seem absurd because of course you want to expose images when you go out shooting. But what I’m getting at is this: Are you pressuring yourself to make exposures even when nothing really excites you? Almost all of us do this because we want to produce new images.

But there’s a huge difference between “pressuring” yourself and “pushing” yourself. If you’re pressuring yourself, you’re often forcing bad imagery just for the sake of producing something. Some people feel that if they’ve been out for 20 minutes, or an hour, or maybe three hours without making a single exposure, there’s a problem that demands a solution. They’ve got to do something.

That’s the wrong approach. You simply can’t do any creative work when you’re under pressure, even if you’re the one ratcheting up the pressure. It’s certainly worthwhile to try to push yourself to look for things that are really different from your usual subjects. This is a way of pushing yourself into new realms. But don’t pressure yourself to do something just for the sake of doing something...anything. Some people will knowingly make a useless photograph just to “get things going.” But pressing the shutter release or squeezing a cable release is not an athletic event; you don’t have to warm up to make a good photograph. Instead, you have to find something that excites you. You have to engage your seeing and your thinking, perhaps in new and different ways.

The great bulk of my photography can be called landscape work. For me, the reward is simply being out in the woods or the mountains or the canyons. If I expose some photographs, that’s good. If I make a truly exciting photograph along the way, that’s even better. I’m always looking for potential photographs, and I tend to look carefully for both overall general landscape images and details within the landscape, but the greatest reward is simply being in the landscapes that I love, surrounded by nature. I push myself to look for photographic possibilities, but I never pressure myself by making useless photographs simply to break through some imaginary impasse.

I recommend you do the same. Find subject matter that is so compelling to you that just being in its presence provides a huge reward. Otherwise, you’re “stalking” photographs, you’re not seeking them. If you become frustrated with the lack of exposures you’re making during an outing, stop to assess what’s really wrong. Perhaps the light is wrong. Perhaps the location is wrong. Perhaps the subject matter just isn’t working for you that day. Try to shift your thinking to more properly encompass the conditions in which you find yourself. Perhaps you have other things on your mind, and you’re just not involved in photographic seeing. If so, it may be best to quit for the day.

The same holds true for darkroom printing or digital finishing work. Sometimes the images I’ve chosen for final printing or final digital processing don’t pan out as well as I thought they could. That, too, can be frustrating, but I try to adopt the attitude of “you win a few; you lose a few.” That’s the attitude you need to take, even while you’re trying to produce really good work. Sometimes I’ll come back to the losers and find that my approach had been wrong, and surprisingly there was a fine image in there after all. I may have simply needed some time to roll my approach around in my mind—perhaps subconsciously—before the right printing or processing procedure came to me. I allow those possibilities to occur. I recommend you do the same.

I tend to approach darkroom or computer work with a combination of a studied and an intuitive manner. I always have a backlog of negatives waiting to be printed. Some are recent exposures; some are old negatives that I initially overlooked but now strike me as having good, expressive possibilities; and some are ones that I previously printed and discarded, and now I’m seeing them differently. First I study them carefully to put them in an order of preference for printing them: this one excites me the most, that one second, that other one third, etc. I also study each one to map out a basic strategy for printing it: exactly how I want to crop it (if I crop it at all), the overall contrast I’ll use, the level of lightness or darkness, and where I’ll have to dodge (lighten) or burn (darken) and at what contrast level, area by area.

Then, based on a knowledge of the speed of the enlarging paper I’m using, I guess at the basic exposure, and do all the burning and dodging I’ve already decided upon, with the goal of making my first print a “perfect print.” Usually, I’m fairly close. Once in a while I’m dead on, but that’s rare. Sometimes I’m far off the mark, but a careful evaluation generally puts me quite close by my second effort. But it’s all based on a combination of planning, intuition (which is born of experience), and careful evaluation. From that starting point, I work toward improving the image until I get what I want. Sometimes, along the way, I see new things that I had missed before, and those new finds or problems have to be incorporated into the printing strategy.

I never make test strips; I go for it. I’m convinced that I get to the final image far faster this way, and I’m much looser about the process along the way. So it’s really a very intuitive approach.