FIVE

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MYTHS OF THE AWAKENING OF HIGHER CONSCIOUSNESS

In the Egyptian Osiris myths, the central figures, Osiris, Isis, Seth, Nephthys, and Horus are all neters—that is they are principles, or gods, that act on higher levels of existence. It is through reaching down from these higher levels to that of humankind that they order and maintain the Egyptian civilization. This approach in the Egyptian myths helps us to explore “god knowledge” and how it relates to the awakening of higher consciousness in the modern-day world—remembering the challenges presented by our sense of superiority that arises from our engineering prowess. As a specific example, by the twentieth century CE it was particularly difficult to understand what is meant by the word spiritual as opposed to the materialistic, which runs our daily lives. We are only questionably better off now in these early years of the twenty-first century. Is there truly a level of being that is beyond the purely physical existence allowed by science and by that explored in psychology? Is the spiritual not accounted for in expressions of the psyche? The Egyptian myths imply that we must confront this recurring question directly.

The Egyptian myths seem designed to evoke our most subtle levels of awareness and discrimination. Through them we may discover whether we can escape the consequences of the blindness and deafness of preconception demonstrated by Gilgamesh and repeatedly warned of in biblical texts. Loss of attention required for discrimination has been the lot of too many serious seekers of wisdom before us. We require an active attentiveness to both the observed and the observer in us so that we can be awake to the sense of distinction between them. We are not accustomed to dealing with such inner subtleties or to being attentive to a need to discriminate between levels of perception in our usual lives. It is for this reason that we began this book with a reference to the neglected sense of our own “presence.” It is not at all included in the way we meet everyday life. Internally we seem to know that only by some effort of development in this direction can we hope to verify that which lurks in inner personal experience and holds the key to our ability to connect two potentially distinct foundations of our being called the “ordinary” and the “spiritual.” The Egyptian myth of Osiris may help in this pursuit.

Our Basis for Understanding the Osiris Myth

As with the other myths we discussed previously, the myth of Osiris has a long lineage and was never written down in comprehensive form by its creators (see appendix 1). Although never written down, it was well represented in many carvings, embossings, and paintings. Segments of the myth are widely found written in hieroglyphs associated with the illustrations as well as in stand-alone literature throughout the thousands of years of ancient Egyptian culture. The many texts that refer to the life, suffering, death, and resurrection of Osiris accept the story as universally known, as indeed it must have been to the Egyptians. The material we have in written form was provided by the Greek historian and biographer Plutarch (46–120 CE).1 Similar to the other myths, we depend on an account written some three to four thousand years after the origin of the legend, appearing in a different language and a different culture than when it was first imagined!

The difficulty of appreciating the meanings of the hieroglyphs (see appendix 2) should not be used to dismiss what has been found in a careful study of Egyptian literature, art, and architecture by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz.2 He provides evidence that the Egyptians had a very advanced understanding that led to the construction of the pyramids, assemblages of statuary, and elaborate and beautiful buildings. Their geographical and geometric knowledge was extensive. In particular, he insists that understanding Egyptian symbolism requires differentiation between the logic we customarily resort to in studying and what he describes as “the intelligence of the heart.”3 This is his term for a type of understanding that is related more to our intuitive functions and sensations than to the exercise of logic. This appeal to an aspect of the finer sensations that may arise through contemplation and meditation is very compelling and seems closely linked to alternative medical practices that are becoming better known today through such disciplines as osteopathy.

As a brief introduction to the complexity and subtlety of Egyptian thought, we look to R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz’s teachings of sacred geometry.4 In his book he finds embodied in the Egyptian structures subtle effects on mind and perception that are not well understood today except among a few specialists. Egyptians perfectly understood the basic geometric and geographic relationships among the stars, planets, sun, moon, and earth. Important mathematical relationships were incorporated into the designs of even the very earliest pyramid structures, as well as the much later major temples at Luxor. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz discovered that long before the Pyramid Texts were written down, the special ratios of π (pi) and φ (phi) were built into structures. Such ratios were not understood outside of Egypt until after the time of Pythagoras (570 BCE).

Finally, Egyptian symbolism often occurs in combinations, such as the writing of Egyptian myths on various structures and mummy wrappings with the many figurations and images engraved and painted beside them on the temple and tomb walls. It seems necessary to directly experience some of the modes of presentation they used if we are to approach the meaning of higher consciousness, which the myths were clearly intended to evoke.

Myths of the Mystery of Existence in Ancient Egypt

The myth of Osiris tells of the various stages in the life and relationships of Osiris, who was created by the Great God Atum to become king of the Egyptians. He carried out his duties on earth with the support of the neter Isis. She was born as his sister and became his wife. The Egyptian creation myths tell us that it was through the separation of Nut and Geb that spirit became manifest on earth, and so these two, Osiris and Isis, with their brother and sister, Seth and Nephthys, also considered to be husband and wife, were born and became manifest as children of Nut and Geb. In this way these neters are shown as the primary principles that guide life and spirit on earth.

While the neters Seth and Nephthys do not initially seem to have been assigned particular roles, it is clear from his actions that Seth was a particularly powerful neter, appearing to our earthbound level of perception as a destructive influence. From the higher level of godlike perception, he seems to be the required opposite of Osiris and his creativity. In our modern language we can say that Seth manifested the quality of entropy. That is, he was responsible for dismantling structured manifestations, which we recognize takes place when attention is lacking—lost in the memories of yesterday and the dreams of tomorrow. In keeping with this theme, his sister and wife, Nephthys, is said to have been queen of the part of the sky that is always invisible from north of the equator. This influence is symbolically related to night, darkness, and obscurity, and is therefore an opposite of Isis.

Isis appears in the sky as the brightest star of the heavens, called Sothis by the ancient Egyptians, currently called Sirius, and she was a constant companion of her creative brother, Osiris, who is represented in the sky by the nearby constellation of Orion. These forms of the neters as constellations and stars were recognized in the Pyramid Texts as being involved in the process of akhification. That is, they are engaged in the act of becoming one of the highest beings of the spirit world. Within this metaphysical setting the mystical story of Osiris unfolds. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz points out that the only way we can understand the concept of wholeness is through our ability to appreciate the effects of a whole being divided into parts.5 This notion is explored further in appendix 3.

Symbols of Family Relationships

Osiris is referred to as the son of Ra, in the sense that the Ra who descends from his daily existence in the sky into the Duat at night is the father of the “sun” of this unmanifested world. Ra is also the father of Nut, the neter of the sky in which he appears by day, and who by union with the earth neter, Geb, gave birth to the family of gods: Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, and Seth. Thus in his lineage Osiris is also the grandson of Ra. At the same time, Nut, the daughter of Ra and mother of Osiris, is called the Mother of All the Gods and is often called the Mother of Ra. Nut is thus both daughter and mother of one and the same god!

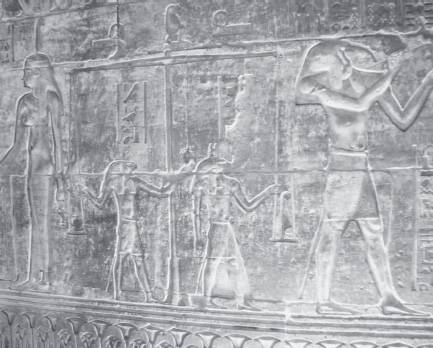

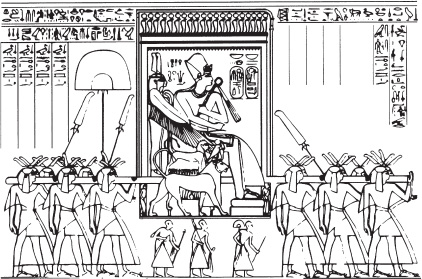

Correspondingly, consider the many faces or aspects of Horus (also known as Heru), who in the Ennead lineage seems clearly to be the son of Osiris and Isis. Horus is also known as Ra-Herakti, god of the morning sun. He is one of the chief forms of the sun as it is at midday, when he has the name Ra-Heru-khuti. Horus observes his own conception between the “dead” but resurrected Osiris and Isis in the famous carving on the walls of the Temple of Osiris at Abydos (see figure 5.1 below). In this instance, Isis appears as a falcon, a form that is often assumed by Horus in his relations with the sun and with Seth.

Isis had hidden the inert body of Osiris that she had recovered in the mythical Byblos and re-enlivened for Horus’s conception. She was then constrained by her great love to collect and “re-member” Osiris, prior to his reappearance as the ruler of the Duat. It is through this act that we see the Duat as the land of the “Everlasting.” This dark and mysterious world is contrasted with the world of the “day,” where the pharaoh reigns, as one of ordinary time, hence recognizable as a relatively ephemeral world. The Egyptians referred to this ephemeral world as “Eternity,” quite different from the night, which is “Everlasting.”6

Figure 5.1. Osiris impregnating Isis.

Temple of Osiris at Abydos, built by Seti I.

Such a complex and detailed mythology cannot be expected from the kind of simple culture purported by some Eyptologists. It is obvious from the social organization that was necessary to sustain the building of such remarkable structures as occupy the plains of Lower Egypt, as well as from the subtleties of placement and design, that the most ancient Egyptians of the early dynasties lived in a highly organized and complex culture. In the Sphinx (figure 5.2) and the pyramids (figure 5.3) we do not have examples of toy castles built by overgrown children, even if the frustration of understanding evident in the translations and interpretations of some Egyptologists might have made them sound so. Once again it becomes clear that we do ourselves a disservice by trying too hard to fit what we find in Egypt into our ready-made molds. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz in his book The Temple of Man clearly shows this disservice in regard to Egyptian mathematics and geometry that, once seen as having a different intent and underlying structure, can be appreciated as sophisticated and powerful as our own.7

Figure 5.2. The Sphinx. Giza Plateau.

Figure 5.3. The Pyramids of Giza. This view is no longer available because modern high-rise apartments have been built in the foreground.

All our powers of discrimination seem to be most usefully employed to guard against the loss of our ability to analyze our conclusions or against our tendency to substitute imagination for knowledge. When we fail to see past our own preconceptions, we neglect the possibility of detecting what is new in the truly old. If new meanings result, this alone would suggest that we have come closer to appreciating something of the wisdom of the ancients than could ever be drawn from a logical proof that our “insights” are exactly those intended by the Egyptians!

The Myth of Osiris and Isis

Osiris and his sister Isis, the two firstborn of Nut (the sky) and Geb (the earth), while born neters, become king and queen of Egypt. They are responsible for teaching the people of the lands the arts and practices of farming and cultivating the soil, harvesting and storing grain, and making wine and beer. They introduce a code of laws to guide social development and teach humans to worship the neters. In general, they inspire the rise of Egyptian civilization. When this work is accomplished, Osiris temporarily leaves the kingdom in the care of Isis and sets out to instruct other nations of the world. During this period the civilization they had established is so sound that despite the disruptive efforts of their jealous brother, Seth, the kingdom cannot be upset.

Seth, who personifies in both subtle and blatant ways the powers of degradation and destruction, is persistent, and together with his seventy-two comrades and with Aso, the queen of Ethiopia, he plots to get rid of Osiris. They secretly obtain the exact measurements of Osiris’s body and have a beautiful box constructed to these measurements. Then, at a banquet, Seth offers the box to whoever is able to fit it. Of course, after everyone has tried and failed, Osiris is persuaded to get into it. He fits! And the plotters seize the box, slam shut the airtight lid, and after sealing it to ensure his suffocation, carry it to the mouth of the Nile and throw it in. This event takes place on the seventeenth day of the month of Hathor, neter of love and motherhood, a day marked as triply unlucky in the Egyptian calendar. It also takes place in the twenty-eighth year of Osiris, which points to his status as a moon neter—a neter of the night.

This disastrous event is immediately known by Isis, who is absent from Osiris at the time, visiting in the village of Chemmis, near Thebes. This place has ever since been known as Coptos, the City of Mourning. When she learns that he has been suffocated, she cuts off a lock of her hair and dresses in deep mourning. She then sets off in search of the body of her husband and brother, accompanied by Anubis, the jackal-headed neter, who, in keeping with the nature of jackals, has a special affinity with the dead. She eventually learns that it was transported by sea to the shores of Byblos, where a great tamarisk has grown up around it. So magnificent was the tree that the local king had it cut down, and the central trunk, which conceals the dead Osiris in his casket, has been set up as the main pillar of the king’s huge new palace.

After a number of dramatic adventures, Isis gains custody of the body and transports it back to Egypt. There she opens the casket, and using the power of her attentive love, arouses the body, flies over the erect phallus in the form of a falcon, and conceives the future king, Horus. She then hides the casket containing Osiris’s inert body in a secret place and proceeds to a papyrus swamp, where she hides the infant Horus.

Seth, hunting by the light of the moon, comes upon the casket, which he instantly recognizes. He tears it open, rends the inert body of the king into fourteen pieces (twice the magical number seven!), and flings them along the length of the Nile. Isis soon learns of this additional desecration, and after an intensive search, she finds all the parts except for the phallus, which seems to have been consumed by fish. She thereupon makes a model of it from the clay of the riverbank and enlivens it by magic. She then turns the parts of the body over to Horus, Djehuti (who is better known by the Greek name Thoth and who is equated with the Greek god of wisdom, Hermes), and Anubis, who bind and embalm them into a whole body. Thus is Osiris “re-membered” as an “entire” if inert body, so that he can assume his rightful place as ruler. In this process of resurrection, however, he becomes king of the everlasting night, the Duat, and places his son, Horus, in his stead on the throne of the ephemeral daytime of living beings.

Horus, the Son Who Rules by Day, resolves to avenge the suffering and death of his father, Osiris, but is initially unable to trap Seth in direct battle. However, Ra gathers massive forces to provide opposition to Seth, who is clearly in rebellion against Ra’s rule. Horus is commander of some of these forces and becomes a principal participant in the warfare. The battles are full of trickery and bitter personal struggles between Seth and Horus, in which the two contestants take different fierce animal forms, wounding and maiming each other, including the rape of Horus by Seth and the castration of Seth by Horus. One source8 maintains that this battle continued for seventy-two years of earth time.*7

At one point in this celestial struggle, Horus captures Seth, binds him, and turns him over to Isis to guard. She, however, through Seth’s clever beguiling, a characteristic shared with Sumerian Humbaba in Gilgamesh’s Land of the Living, takes pity and releases him. When Horus hears of this, he grows so enraged that he pursues Isis and cuts off her head. Djehuti, who as neter of wisdom was sort of referee of the whole epic struggle on behalf of the court of the neters, finds this violent action unjustified and replaces Isis’s head with that of a cow, which explains the close affinity of representations of Isis and the cow-headed neter Hathor. Hathor also clearly has a double nature. At one point in her story she goes berserk and destroys vast numbers of humankind with so much bloodletting that it horrifies even Ra. This provides a second striking parallel between Egypt and Sumer, this time between Isis-Hathor and Inanna-Ishtar who brought down destruction on Uruk with the Bull of Heaven.9

In another battle sequence, Seth plucks out the eye of Horus, which, because Horus is an aspect of the sun, is also the eye of the great god Ra, and flings it to the ground, where it smashes into a million small pieces. Djehuti, who constantly observes the battle, sees this event and takes careful note of where the eye falls, collects all the pieces, makes it whole again, and returns it to Horus. This enables Horus, after the battle, to pop this eye into the mouth of his father, Osiris, thus reinforcing Osiris’s nature, despite being inert, as a god who is able to offset the mighty dismembering, or entropic, powers of Seth.

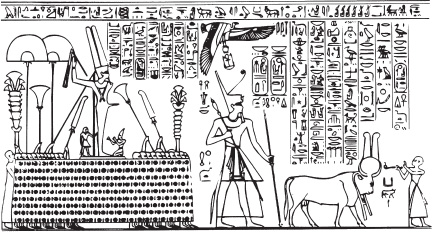

Eventually, Seth exhausts his energies and agrees to abide by the judgment of the other neters that he should leave Horus and Osiris in peace, to rule their respective kingdoms. Osiris, the re-membered and resurrected god, is thereafter constantly attended by Isis (figure 5.4). But the Egyptian imagery does not stop there. The myth points out that she is also constantly attended by her sister, Nephthys, neter of the invisible sky world below the horizon at the southern end of Egypt, where the whole drama takes place. Thus, two attentive guardians are invoked: one the neter of the world visible to us at night as the brightest star of the heavens, and a parallel neter, invisible in our visible sky.

Figure 5.4. Osiris accompanied by his two guardians, Isis and Nephthys. Nephthys stands to the left of Isis.

It seems clear that this myth illustrates two kinds of perception. Conscious perception lies in the sensitivity demonstrated by Isis, which we discussed in the introduction. This kind of perception assists us to be aware of our internal, or esoteric, nature. Nephthys, the neter of the dark, unseen world that we can scarcely comprehend, is symbolic of unconscious perception. This myth points out that we need to discriminate between two aspects of our perception, both of which Egyptians associated with the resurrected subjects that died in our ephemeral world and appeared before Osiris, Lord of Entirety and Lord of the Duat. Only Osiris, because of his own experiences, can point them, with their complete perception, to a new sense of direction. The example set by Osiris invokes the powers necessary for the passage of new candidates to resurrection: discrimination and courage. He points them toward a resurrection parallel to that which enabled him to overcome the forces of dissipation, or entropy, those insidious influences exuded by Seth.

Many subsidiary symbolic elements are contained in the, at times, virtually obscene though dramatic battle between Horus and Seth. It invited paeans of praise and hope, as well as amusement, in much of the Egyptian literature of the New Kingdom. Individual events are rich with symbolism that could occupy a much longer dissertation than we can undertake here. As might be expected, the story is also recalled in different detail, or at least with different emphasis, in various versions of the Book of Coming Forth by Day. One literal interpretation is that the “dead,” who are always given the name Osiris, travel through the Duat, and after due “rituals of judgment,” emerge to be subjected to the famous psychostasia, or “weighing of the heart” (figure 5.5). If the weight of the heart is equivalent to the weight of the Maat feather, they proceed to the Aaru or “Field of Reeds” representing a heavenly paradise in the presence of Osiris. The “dead” request him to grant the blessings of the neters upon them. They are then able to have continued life even as he did when he became the ruler of the dead. Such literal interpretations, in fact, became the model adopted by nineteenth-century CE Egyptologists, who misinterpreted what they saw in the writings and images and prejudged them to be from a simple, literal funerary culture. This intellectualized interpretation obscured the remarkable psychological and spiritual meanings imbued in the symbols of Isis, Nephthys, and Osiris.

Figure 5.5. The weighing of the heart, Ptolemaic tomb, Deir el-Medinah. On the left-hand side of the scale, Horus’s right hand steadies the container of the heart. Seth, on the right, in his left hand steadies the feather of Maat.

Our primary interest is in those dimensions of the tale that speak directly to the questions of time, death, and creation. However, it is worth reminding ourselves to take heed of the warning of the myth that the casket of preconception, which is made to exact individual measurements, was used by the forces of degradation and entropy to suffocate the great king of Egypt! It is even suggested that if Isis (with her perception) had been present when Seth held his banquet, Osiris would never have stepped into the coffin. Yet the myth shows that it is no simple matter to maintain a strong attentiveness. The person newly entered into the Duat must continually guard and protect him- or herself from the vast potential power of Osiris, which helps in overcoming the opposing spirits that dwell in this other realm.

The Roles of Osiris and Isis

Initially the Egyptians emphasized Osiris as a god of resurrection, a role he shared with Ra in his “rising every day.”11 This attribute is also referred to in chapter 17 of the Book of Coming Forth by Day, in which Osiris as Ra is identified with the bennu bird, or phoenix. This view of Osiris makes him comparable to the god of many naturalistic religions that have used the symbolism of the springtime regeneration of plants and animals to mark the rhythms of nature and the cycles of the generations (figure 5.6). In several early dynasty documents, Osiris is shown as a god of the harvest, symbolized by an ear of corn.

However, we must be attentive to the full nature of the symbolism. Do concepts of seasonal regeneration fully explain the tenor of the struggles among the neters? Renewal of a beneficent god-being in the natural course of harvesting, planting, and seed germinating, a seasonal rhythm of life and death, seems too passive an image to associate with the violent events surrounding the death of Osiris, his dismemberment, and Isis and Horus contending with Seth on his behalf. In these Egyptian myths we are dealing with a more extensive and active phenomenon: here we have strong and active positive forces competing with equally strong and active opposing forces. They continually face one another in intense, dramatic struggles.

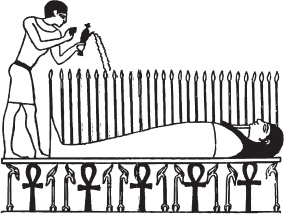

Figure 5.6. Corn grows from the body of Osiris. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 4.15.

The Osiris symbols seem deliberately intended to confront our lack of awareness and our passive illusions about what constitutes life. If we remain inattentive we may simply drift through a succession of accidents and minor events between birth and death. This tale shows us that such sleepwalking amounts to a blind and destructive disregard of the vital forces underlying being, which leads to death. In the face of this death, the ability to truly know yesterday and tomorrow needs the power of awakening represented by the immediate and alert attention of both Isis and Nephthys. They represent vital and active conscious and unconscious forces that are required to help us gather our scattered attention, much like Osiris’ scattered members, for the real struggle for transformation. Through the union of Osiris and Isis, the re-creation of Horus as king of the present day became possible. But both Isis and Nephthys are needed for the ensuing struggle for the reawakened being.

By such imagery the Egyptian myths parallel the later Christian images of the disciples who slept even in the face of Jesus’ impending death. Such images may yet urge us to a more powerful and more personal metaphor for our possibilities. Stories of wisdom are not about others, about the dead, or about events of the past. They are about us, now. The symbolism of the myth of Osiris warns that our part in understanding the difference between death and awakening to life can be played only if we maintain an active role in the continuing struggle between preconception and perception. So rapidly are our fleeting moments of clarity destroyed by our habitual, day-to-day preoccupations that we need help to even be aware of their existence. We need to be fully aware that we are participants in this myth if we are to maintain attentiveness. Only by awakening can we turn toward the possibilities for living as a re-membered being, existing in the everlasting present.

The Egyptian myths, in parallel with that of Gilgamesh, also seriously question our ability to pay attention to our failures, which is required to realize our wish for wholeness. Our appreciation of the Osiris myth depends on the depth of our openness to the human condition. We view our situation with an overly objective intellect, primarily by reference to our analytical memories of past states. But do we not exist outside or beyond such purely mental abstracts or preconceptions? If, for a moment, we attend to our internal aspiration toward wholeness, we see the powerful distractions of thoughts and sensations, nourished by desires and habits formed during a lifetime. However, a moment of actual experience of the fragmentation they generate can help us understand why in the Egyptian imagery of Osiris, his re-membering requires the power of a great god! The forces of distraction, encapsulated in the being of Seth, repeatedly overcome our deepest desire for a sense of unity. Awakening to our actual situation requires great power. Such power will be discussed in chapter 7 when we explore the magic of Heka.

When we become aware of our distracted and fractured condition, it may be possible to taste the remarkable godlike perception symbolized by Isis and Nephthys. Re-membering our entire scattered being requires the special patience, care, determination, and strength that they display. We often experience these characteristics when for a moment we are able to see their absence in us. These myths help us to see that our possibilities depend on a capacity to find and especially to experience the “here” and “now,” as opposed to the yesterday and tomorrow of our ordinary level of existence.

Moments of awakening are not ours to command. We are not even accustomed to paying attention to the subtleties of sensation and feeling that exist in us at ordinary times. We scarcely notice either their presence or their absence, unless we are by accident confronted by situations that threaten our lives, give rise to extreme emotional upset, or appear in our dreams. To recall them voluntarily might be possible, but first it is necessary to be aware that we wish to do so. The struggle between the “outside,” habitual forces that preoccupy our moment-to-moment existence and the dimly perceived wish for an inner sense of clarity and completeness may be our most serious and important effort toward a better quality of life, but we are oblivious to it. We squander the immeasurable gift of life by our inability to take responsibility for a struggle that could enable us to have at least an awareness of our presence in our life.

The external forces of life are so strong that we take the wish for a struggle against them seriously only when some influence helps us remember that there can be a struggle. This realization of the need for help to mount the struggle is behind the religious teachings of all ages. The wonder that can arise from realizations embodied in the monuments of an ancient culture seems sufficient justification for treating problems the way the Egyptians did—as concerns of the neters. The enlivening of such realizations in our own experience assures us of the existence of the wisdom that we seek.

Only ignorance of ourselves and our situation could lead us to regard these powerful symbols of the search for wholeness as entertaining stories written by a people “of a limited range of sentiment . . . a pleasure-loving people, gay, artistic, and sharp-witted, but lacking in depth of feeling and in idealism,” as they were described by Gardiner in the final phrases of his otherwise excellent, if somewhat limited, introduction to Egyptian Grammar, first published in 1927.12 What we seem to neglect in our own efforts is the simple fact that rather than immerse ourselves in anxiety and fear about the loss of our attention, we can always make a new effort to enliven it! This is the message behind these tales of continual struggle and their injunction that the real task of our life is to continually seek the inspiration of the gods to serve the real purpose of both our existence and the existence of those who are in relationship with us.

Osiris in Relation to the Egyptian Experience

Our discussion of the Osiris myth to this point has left out consideration of the attitudes engendered in the Egyptian population by their day-to-day experiences of the seasonal rhythms. They heard these myths repeated each year at the many festivals that marked the seasons of their lives. The yearly rhythms included the Nile’s seasonal flooding of almost all the agricultural land. Each year, under the close supervision of administrators and priests, the Egyptians reclaimed the land from the floodwaters. These authorities guided the remarking of the fields and led both the work and the regular celebrations for the common good, which they promoted throughout the year.

The whole population experienced firsthand or knew from family histories the times of plenitude and even more certainly the times of hardship, shortage, and even famine. The unpredictable variations in the seasonal flooding that revitalized and refertilized the fields no doubt had an effect on their lives. The significant uncertainty of outcome must surely have given rise to a sensitivity to their dependence on powers that, while natural, were beyond their understanding. The Egyptian culture attributed the conditions afforded them to the efforts and interactions of the neters. They were responsible for the phenomena of cause and effect in the human world.

We have already noted that the simple agricultural model of the Osirian resurrection relating to the awakening of life in planted seeds seems too passive to associate with the violent, destructive images surrounding Horus’s struggles against Seth on behalf of his father, Osiris. However, in the light of the uncertain nature of the yearly flooding, such an association may make more sense. Understanding may come if we study the transformation of Osiris to ruler of the Duat. Perhaps we have misjudged the roles of the neters and their effects on the living. In what follows, we enlarge the scope of appreciation of this central myth.

How the Egyptians could attribute the effectiveness of their own efforts to the attitudes of the neters is difficult to comprehend from a modern standpoint, but we must acknowledge our need for a broader understanding if we are to gain an appropriate perspective. Variations in the natural setting were the background for their experience of the myths, and we must try to place ourselves in a situation of comparable scope in our observations. In particular, we need to try to see what is missing from our conceptions by looking at the many aspects of the myths that relate to the circumstances of Osiris. What in their annual experiences might account for the state, transformation, and eventual fate of Osiris?

Let us consider the seasonal patterns that took place in their land before the dams were built at Aswan. The Egyptians recognized an annual cycle of three principal seasons. Their year began with the river flooding over the land—the season of inundation, or Akhet. This was followed by the season of planting, growth, development, and harvest of the various crops on which they depended for survival—a season of “coming forth,” emergence, or Proyet. Finally, at the end of the harvest, the heat of the sun, combined with the dryness, threatened to transform the land to a desert state. These desert conditions were pushed back and held at bay only by the rejuvenating effects of the rising river. The final season of the Egyptian year thus resulted in a period of gradual loss of life-giving powers, or “deficiency,” called Shomu. Many unknowns and uncertainties were associated with the season of dryness.

In this setting, the seasonal sequences and their consequences were clearly known to everyone. We need then to turn our attention to the extreme differences that are evident when experienced close at hand, living on the banks of the Nile. To those who depended on the land for their survival, the vicissitudes wrought by the natural world not only would seem to hold their lives for ransom, but might even be considered to be a factor in the eternal struggles of the neters, certainly of Osiris and his sometimes violent and always strong brother, Seth. The myth indicates that the god Horus, son of Osiris, represented on earth by the king, needed to mount supreme efforts to ensure that the forces of entropic decay did not prevail. At stake were the creative forces of magic, justice, and cosmic unity, engendered by Heka and Maat in their support of Isis and Nephthys, who constantly attended to their brother god, Osiris.

Returning to the seasonal imagery, let us view the fate of Osiris as an analogy for the agricultural successions throughout the year. For this it is reasonable to begin with the season of inundation, which is shown as early as the Pyramid Texts to start close to the time of the reappearance of a particular star: Sirius to us, Sothis to the Egyptians, represented by the neters Sopdet or Isis. After the star’s seasonal absence, it could be seen again in the sky just before sunrise. This was the time of the new year in Egypt, which marked the recovery of the land at the beginning of the spring flood, a time of enrichment that must have been keenly felt by all.

Teti Pyramid Text Recitation 146 welcomes the event with a tribute to Osiris:

Isis and Nephthys have seen you, having found you.

Horus has gathered you,

Horus has had Isis and Nephthys tend you,

and they have given you to Horus,

that he may be content with you.13

The text remarks on Horus reawakening the endangered Osiris at the rising of star Sothis, personifying the neter Sopdet. Up to that point, in the seasonal cycle of Shomu, Osiris existed in the world only as the inert mummiform body. He required their intervention in order to realize his fate. The rising of the river thus appears to mark a reflection on earth of the beginning of a new season in the sky, in which the rising of Sothis signifies Isis finding Osiris’s inert body and giving it to Horus. Horus turns his attention to the needs of his father, Osiris, which marks the recurrence on earth of the eternal act of his son, Horus (embodied in the pharaoh), in making things grow on the newly exposed soil.

The inert mummiform figure of Osiris, kept under close protection by Isis and Nephthys, is the actual base from which the harvest grains grow (see figure 5.6). In the story we glimpse something of the exchanges between humans and gods. As in the Sumerian creation myths, man is placed on earth to provide essential assistance to the gods; the gods in their turn serve the even higher levels of creative powers represented in the Egyptian myths by the sun, Ra. Yet it is from Ra that humankind is afforded nourishment. This circularity is essential to the continuation of their entire culture.

The rhythms of life celebrated in the annual festivals are of particular importance in understanding the Egyptian view of neters and of humans. These rhythms of life were identified by the Egyptians and recorded in the various versions of the myths. It is also to be found in the basic but important references to the “power of germination” of seeds that exposes the whole process, which offers the hope for the arising of Self and the awakening of higher consciousness.

The Egyptians recognized in the mysterious process of germination two aspects of humankind that they identified as aspects of the body. The first is familiar to us as the physical body. We know it as liable to death and decay. However, the second body, called the sahu, is today scarcely recognized by Western culture as a separate entity. The modern biological term for it is germ plasm, the conductor of the principal force for biological continuity in all living species. The Egyptians recognized it as the basis for survival of life from one generation to another, that is, as the essential physical basis for a continued influence beyond individual death. In today’s modern world, our unfamiliarity with this notion may reflect our loss of perspective about the life process; we have but a vague awareness of something we know as “genetic influence.” See appendix 3 for a more detailed exploration of numeric representations of the germinative aspect.

We can further profit by paying closer attention to some of the more abstract references to Osiris, such as his development from the inert state at the end of the creation myths to a more active participant in Egyptian affairs following the end of the battles between Seth and Horus.

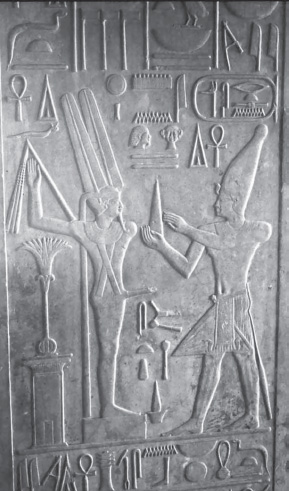

We call attention now to the djed column, a hieroglyphic symbol that represents stability. The symbol frequently appears on the walls of temples of the Eighteenth and later dynasties, but was clearly well known for a long time before that. According to some scholars, this column represents the spinal column of Osiris. Figure 5.7 shows Horus erecting the djed column in the Temple of Osiris in Abdos. This temple is one of the finest of those remaining in Egypt, although it is generally less known because it is a few hours’ drive north of the principal centers of worship in Luxor. These magnificent, slightly raised carvings in the special Seti I style are located in a room beyond the temple’s large introductory chamber. Seti I, in the form of Horus, lifts the column in this depiction.

Figure 5.7 demonstrates the subtlety of the illustrations on temple walls. In this case, the mystery of the Osiris story is not referenced directly, but once we recognize the association of the column with Osiris, we can see how very important such representations are in the story of the continued existence of Osiris, especially the help he requires to play his full, upright role (figure 5.8). In this case we also have an example of the assimilation of the god Horus into the person of the reigning pharaoh. This illuminates a further aspect of Osiris’s death at the hands of Seth. Upon Osiris’s death, Horus becomes king of the living in his place, while at the same time Osiris is resurrected as the supreme ruler and guardian of the everlasting Duat. Throughout the Osirian legend it is thus repeatedly made clear that the inert Osiris depends on assistance from the living to realize his fate. It is another example of how the Egyptians recognized the importance of exchange between the worlds to be of utmost importance. This example helps us understand the Egyptian view of the obligatory intertwining of the human world with that of the neters in order that both should fulfill their destinies.

Figure 5.7. The pharaoh Seti I, as Horus, on the right, erects the djed column with the help of Isis on the left. The small kneeling figure on the left is likely another representation of Seti I as Osiris. From the Temple of Osiris in Abydos.

Figure 5.8. Seti I makes offerings to Osiris, the erected djed column. The small kneeling figure on the left is likely another representation of Seti I as Osiris. From the Temple of Osiris in Abydos.

We need, however, to make yet another excursion into how the role of Osiris is entwined with the spiritual development of humans. The use of allegory is an important way that the makers of the myths presented their esoteric knowledge. The neter Min takes a primary role in this example. He is frequently shown on the walls of temples of the Eighteenth and subsequent dynasties as a great neter. Figure 5.9 shows a representation of Min from a wall of the small but beautiful Temple of Sesostris I of the Twelfth Dynasty. This temple is now situated among the reconstructions within the Karnak Temple Complex because it was found in pieces within that complex (figure 5.10). Min was also frequently mentioned in the Pyramid Texts and was well known from the earliest dynasties. Although he repeatedly appears as an independent and major neter, it is important to our understanding of Egypt to recognize in him a reflection of Osiris.

Figure 5.9. Min on the left with Sesostris I. From the Temple of Sesostris I on the grounds of the Karnak Temple Complex.

Figure 5.10. The Temple of Sesostris I, reconstructed within the Karnak Temple Complex.

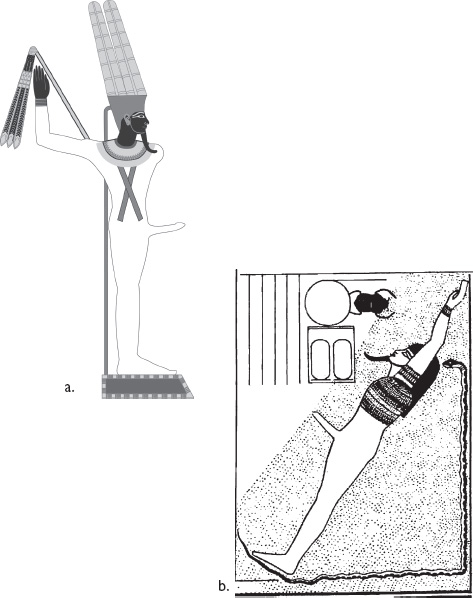

Min, or Amun-Min, in which the name Amun means “the hidden one,” was also frequently known as Kamutef, which translates literally as “Bull of His Mother.” He was almost always shown as an ithyphallic male figure that emphasized his relationship to generation, or more specifically, to the development of what has been germinated (figure 5.11a–b below). It should be noted, however, that Min more specifically refers to internal development, or self-development, which we identified earlier as the esoteric aspect of the story of creation. It is thus clear that this figure also represents that aspect of Osiris.

Figure 5.11. (a) Min as Kamutef. Illustration by Jeff Dahl.

(b) Ramses IX as Kamutef.

Min seems to represent the culmination of the Osiris myth. That is, the god Osiris, who began as an inert mummy, is represented as an ithyphallic image when seen impregnating the falcon in the Temple of Osiris in Abydos (see figure 5.1). He is expressed in our world as an upright and active being in the raising of the djed column, also represented in Abydos (figures 5.7 and 5.8). Finally he is fully represented as Min in the form of an ithyphallic figure (figure 5.9), in which promoting a new creation is his central necessity. It is not, however a “creation” related to sexuality in the sense of external sexual union between a man and a woman, resulting in progeny. Min represents, rather, the generative power, according to R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz.14

Min is the son of Isis and Osiris. Later he becomes the consort of Isis. This makes him the father of Horus. This explains the Min-like ithyphallic representation of Osiris in figure 5.1. He is, however, equally often shown as either a close associate of Horus or even identical with him. It’s clear we need to remain aware of the many symbols and images used throughout the millennia of Egyptian civilization. These representations served many purposes rather than one fixed concept or idea.

An illustration on the walls of the tomb of Ramses IX offers further information on the importance of the generative function in Ancient Egypt (figure 5.11b).*8 Here the pharaoh as Min represents the hypotenuse of a sacred right triangle. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz uses this figure as the basis of his demonstration of the ratios φ (phi) and π (pi) that form the basis of the Egyptian representation of generation in mathematics, geometry, and architecture. His interpretations enable us to see that the generative function illustrated by the neters is more related to laws of internal growth, representing the ideals of humankind. The neters do not represent the reproductive function, which is where our preconceptions might lead us.

This illustration has an additional feature that verifies this point of view. R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz was the first to point out that the phallus in this illustration originates from a position just above the middle of the abdomen rather than from the pubic region. In modern anatomical parlance this is the region of the inferior mesenteric plexus, a position that marks the hara, an abdominal center of great sensitivity, related neurologically to the solar plexus. This is the position of the “phallus” in all Min representations. This we take as confirmation of the important internal, esoteric significance of this great neter, which links him in function to Osiris.

Min’s significance is evident in a major pageant, called the Great Festival of Min, found on the walls of the Twentieth Dynasty temple of Ramses III, called the Medinet Habu, on the West Bank (figure 5.12). This temple is one of the best preserved of all the ancient temples of Egypt.

Figure 5.12. Entrance to the Medinet Habu on the West Bank, Luxor.

Figures 5.13 and 5.14 show one large scene from inside the Medinet Habu. The pharaoh appears seated on his litter, representing the god Osiris. Behind him are two closely standing females, each with a feather on her head, representing Isis and Nephthys. The feathers represent the neters’ role as protectresses that are spoken of in chapter 17 of the Book of Coming Forth by Day. He and his entourage are carried in procession behind the figure of Min, who is on an even more massive platform carried by what may be as many as 120 priests (figure 5.14). The ithyphallic Min follows another pharaoh-like figure, representing Horus as Upper and Lower Egypt marching under the winged vulture of Mut, all of whom are led by a powerful bull wearing the crown of Osiris between its horns. This crown on the bull’s head is an image of the sun, Ra.

The neter Min had, by this time, the Twentieth Dynasty, become more associated with the son Horus, a god of the living, than with Osiris, who had by now become the king of the Duat. This is supported by the appearance of Horus, who upon Osiris’s death became responsible for the fertility and prosperity of the land, shown playing such a predominant role in the procession. While Egypt’s spiritual ideas morphed and became tempered over the centuries, festivals in support of the community (and depictions of those festivals) maintained a certain continuity and assurance in the face of those changes.

It thus appears that the image of the inert Osiris, with which the year begins, progressively develops through various depictions, symbolic of the roles he is associated with in human concerns. These developed but less explicit depictions of Osiris allow for a better appreciation of the overwhelming significance of him as the eternal god. While in his major function as king of the Duat he ensures, through his son Horus, the continued well-being of the people of Egypt and of the civilization as a whole.

There can be no remaining doubt concerning Osiris’s omnipresence and concerned guardianship of the kingdom of the humans. We thus admit to the weakness of our earlier generalization about the agricultural imagery underestimating the power of his story. It does indeed show the Egyptian people’s hope for survival through the vicissitudes of life on earth.

Figure 5.13. The left-hand side of the harvest festival procession of Min with the seated Pharaoh, representing Osiris, supported by Isis and Nephthys behind the seat, each with a feather on her head. Mednet Habou, West Bank, Luxor. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 4.21.

Figure 5.14. The right-hand side of the harvest festival procession of Min, depicting Min on the platform, following Horus under a flying vulture (Mut), led by a bull with the crown of Osiris between its horns. Mednet Habou, West Bank, Luxor. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 4.22.

A Bald Generalization about the Egyptian Myths of the Mystery of Existence

Throughout this chapter we have examined the myths that represent the story of Osiris. A central concept has emerged from this detailed exploration. A repeated emphasis is placed on the interaction between the worlds of the neters and of the humans as an analogy for our internal Self. This appears in the form of an exchange, which must take place in order for our internal world to continue its existence. This cycle of interaction may thus represent the primary basis for the origin of higher consciousness, which at the same time specifies the usefulness of all our parts: body, soul, and spirit.

These remarkable insights may help explain why Egyptian civilization continued over such a long period, despite phases of fragmentation seemingly related to the invasion of “outsiders.” The final throes of ancient Egyptian civilization coincided with the rise of Christianity, followed soon afterward by the appearance of Islam.

The concept of mutuality—a state of reciprocity or sharing, as in the relationship between the Egyptian representation of our internal world as humans and neters—is not well understood in modern Western civilization. As a result, the Western world seems relatively purposeless and in what must surely appear as a serious decline to some; such factors might well lead to a general loss of both personal and collective social values.

The theory of continuous exchange between our various levels of consciousness represented by the two levels of Egyptian existence—the world of the humans and the world of the neters—is dependent on the esoteric aspects of their story of creation and the Osiris myth. Surprisingly, this understanding must have been intentionally introduced to their society by their mythmakers. Without an open acknowledgement of the esoteric sensitivity of humans to higher influences, represented by the neters, it is difficult to imagine how such a mechanism of cause and effect could have been discovered, or could continue to operate. It is only through one’s internal attention to the opportunities afforded by the higher levels of oneself that this whole system can persist.

The essential wisdom expressed in these myths is that the need for wholeness, or oneness, is the most basic, innermost longing of humans as individuals. Without any sensitivity to or awareness of our individual natures, and the consequent superseding of self-interest, we are condemned to a state of disregard and entropy, which leads to an eventual destruction of society. Our present-day lack of perception of this basic need can only lead to disaster. Without the intervention of a higher influence that can fill the place left by our current ignorance of ancient wisdom, it is difficult to see how Western civilization can survive on the basis of technical sophistication alone.