You are coming to the end of what may have been a long journey. We know this is tough for any family. For children who are seizure-free, there is anxiety and fear about seizures coming back. For children who are not improved with the diet, there is sometimes a sense of depression at this having been the “last resort” (which it is not!). For those in between (50–99% improved), it’s a mix of all those emotions.

In prior editions of this book, this chapter was brief and there was little real research to guide our recommendations. That has changed. We can be more specific about the odds. Despite that, every decision is a difficult one and needs to be made as a team approach: parents, neurologists, and dietitians together. Make only one change at a time. Do not wean the diet and medications at the same time! You also do not need to add a medication if the diet is being weaned. We are also generally not in favor of weaning the diet before big life events, trips, school examinations, and so forth. Plan ahead—in most situations, weaning the diet is not an emergency. Also make sure to have your neurologists’ phone number or email readily available in case the wean does lead to worse seizures.

This question is truly up to the parents of the individual child. We will rarely “give up” on the diet in less than a month unless seizures are worsening or the child is having serious metabolic problems we can’t fix. The data would suggest the diet will start to work within 4–6 weeks in most children (if it is going to work). However, we usually tell parents to give it at least 3 months just in case their child is a “late bloomer.”

If it does work, there is no set time in which the diet must be stopped either. Even in super successful cases, most centers will start seriously considering the risks of the diet compared to benefits after 2 years. In many children, we suspect the diet has “done its job” and without it seizures will be no different than with it. The only way to find out ultimately is to wean the diet! For some children, the suspicion will be correct: Seizures will be no different. For some, it will not be: Seizures will get worse. Of course, it is important to be in close contact during the diet wean and have a plan already in mind for what to do if the seizures do worsen.

Some children who have responded exceptionally well to the diet start to come off it before the 2-year mark is reached. This decision is often suggested by the parents and agreed to in consultation with the physicians. We have done this in cases of Doose syndrome and infantile spasms especially, sometimes even after 6–12 months. For children with infantile spasms we treat before medications, if the diet works, we stop after 6 months.

Can the diet be continued longer than 2 years? Yes! The child who has had a good, but incomplete response to the diet and for whom the diet is not a burden may continue the diet on a visit-by-visit basis. We have had children who have remained on the diet as long as 26 years. A lot depends on side effects, too. But many families find the diet is easy and part of their routine … and their child needs to eat anyway! The parents are really the primary decision makers at our center in determining when to stop the diet.

BEN HAS BEEN ON THE DIET FOR 9 YEARS NOW. He is severely retarded and fed by gastrostomy. His cholesterol is 116. He has had no seizures in more than 8 years. Taper the diet? Why would we do that? The diet is no trouble for us and makes no difference to Ben.

The long-term consequences of remaining on the ketogenic diet for many years have been recently studied, and although most children do very well, there can be problems. We recently studied about 30 children who had been continually on the ketogenic diet for 6–11 years. The risk of kidney stones and fractures is about 1 in 4 with this long-term use, so this needs to be closely watched, but no child had very significantly elevated cholesterol levels (above 400 mg/dl). Studies have shown that lipids and triglycerides are elevated during the diet to levels that would normally be considered to increase the threat of stroke or heart disease after a lifetime of exposure. Bone fractures do occur more often in children on the diet for over 6 years (1 in 5). The potential threat of stroke or heart disease after a limited exposure of 2 or even 10 years of a high-fat diet does not appear to occur. Any health threat would have to be evaluated in relation to alternative health risks posed by uncontrolled epilepsy, such as increased seizures or increased long-term intake of anticonvulsant medications, but it is important for the clinician and family to weigh out the pros and cons of remaining on the diet. It may be important to test and see what the diet is still doing 5 years down the road by coming off of the diet. Many parents are scared to take their child off of the diet, but it is not a treatment without risks, and it has to be discussed yearly at each clinic visit to decide whether or not remaining on the diet for many years is beneficial to that patient.

I HAD NOT SEEN OR HEARD FROM JACK in many years when his family called to ask if they could increase his calories. We asked them to come to the clinic. Jack was now a late teenager, with cerebral palsy and moderate retardation. He had been on the diet for 15 years. He had grown and was doing well but still had one or two seizures per year. We decided to taper him off the diet, and after 6 months, he successfully came off it. Seizures did not worsen despite him being on no anticonvulsant drugs at the time of the wean.

Previous editions of this book and even the 2009 consensus statement suggested that weaning the diet over “several” months was “traditional,” but there has never been proof that slow wean was best. It is usually tapered so slowly as there is concern that a quicker discontinuation would lead to dramatic worsening (e.g., some children who may cheat with carbs and have a seizure). However, we have all seen children stop the diet abruptly during a hospitalization or emergency and do fine. In some children we would taper the diet by lowering the ratio every few days. They also would often do perfectly fine.

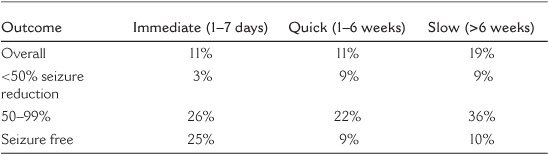

In the summer of 2010 Ms. Lila Worden, a Johns Hopkins medical student, looked at our experience in how to discontinue the diet—the first time this has ever been done. Interestingly, how it was done was different depending upon who the Hopkins neurologist was! About a third of the time it was stopped in 1–7 days. Another third was stopped over 1–6 weeks. The other third was more traditional, and the diet weaned over several months. In general, as would seem obvious, the children weaned slower tended to be those who had done better (i.e., seizure free and fewer medications at the time of the wean). If the diet didn’t work, parents were anxious to stop it—as soon as possible.

The big surprise was that it didn’t matter how quickly the wean was done. For 1 in 10 children, seizures get worse (>25% increase in seizures), no matter the speed of the wean. Details from this study are in Table 16.1.

These results have changed how we wean the diet—we are much quicker in weaning the diet than we used to be. Tapering the diet over months no longer seems necessary—we now typically will reduce the ratio every 1–2 weeks. If a child is in the hospital in a safe setting, generally for an emergency problem, we may discontinue the diet abruptly, too.

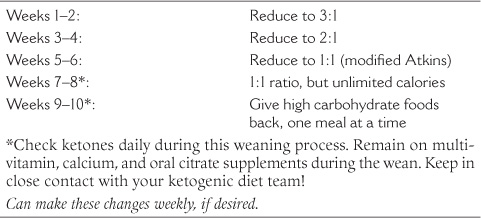

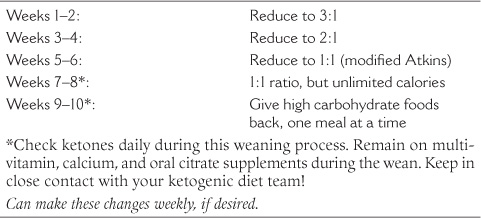

Our current recommended wean (for most children on a 4:1 ratio) is presented in the following list:

Meals with lower ketogenic ratios are increasingly similar to regular meals. A 1:1 ratio will seem almost like a normal diet compared with the 4:1. There will be room for a lot more meat and vegetables and even the possibility of some carbohydrates.

Once a child has been weaned down to a 1:1 ratio and has been on that ratio for 1–2 weeks, we recommend that calories can be given ad lib (as much as desired). Then after 1–2 weeks, formerly forbidden foods can be gradually introduced into the diet. In general, as this happens and gradually introduced high carbohydrate foods have reached a point where the child is no longer in ketosis, and if seizures are stable (or still gone)—you’re home free!

TABLE 16.1

Number Who Worsened by Discontinuation Rate

If seizures worsen with the last few steps, we generally will go back to a 1:1 ratio. This is close to the modified Atkins diet (Chapter 18). We have many children in whom this happened, and they stayed on the modified Atkins diet for an additional several months to years. They generally found it easier than the ketogenic diet and were willing to keep carbohydrates reduced.

Back in 2007, we looked at this question for children who were seizure-free and stopped the diet. Thirteen of 66 (20%) had seizures return, sometimes years later. The seizures were most likely to come back in those who had (1) an abnormal EEG around the time of the wean, (2) an abnormal MRI for any reason (e.g., stroke or brain malformation), or (3) tuberous sclerosis complex. That doesn’t mean we don’t try to wean the diet in these seizure-free children—but we do it carefully. This year, Ms. Worden looked to see if any factors led to seizures worsening in all keto children (not just those seizure free). The only factor that seemed important was having a 50–99% seizure reduction. Children who were either seizure free or <50% improved rarely got worse. When she looked at those children specifically with 50–99% improvement, the only factor that seemed more likely to lead to seizures getting worse was being on more anticonvulsant drugs (1.4 vs. 0.8).

In other words, if your child is still having seizures on the diet after a few years but is definitely better, he/she is at a bit higher risk to have seizures worsen. There is a higher risk if they are on more seizure medications. You can try to wean the diet, just do it carefully!

TOWARD THE END we started letting him smell things. The other kids would give him a sniff of what they were eating, and he would say, “I can have that when I’m off the diet, right?”

SHE WAS A JUNIOR BRIDESMAID at a wedding the day she went off the diet. That was when she was 12. We had checked with Mrs. Kelly and agreed to let her eat cake at the reception. All of us were very apprehensive. There had been a lot of anxiety each time we cut the ratio, but she kept doing well, so sweets were the last test. Nobody else at the reception really knew what we were going through—it was a private thing among us and our very close friends. When she ate the cake and had no problems, it was thrilling for us. After that we were probably cautious for another week or two. Now she won’t look at whipped cream, but she eats just like a typical teenager—pizza and candy and all the typical teenage food.

WE HAD BEEN DOWN TO A 1:1 RATIO for a few months when one day the doctor said, “Why don’t you take him out for an ice cream sundae—you’re off the diet!” Well, I couldn’t quite do that but we did take him for a steak and potato dinner. Then about an hour later I got him a little dish of mint chocolate chip ice cream. It was very dramatic for me to see him eat a real meal. And for him, too—his little eyes were watering. It was a tear-jerking experience. We had finally made it! He used to be an extremely picky eater, but now he just really enjoys eating.

AFTER HE HAD DONE PERFECTLY for a year and a half on the 4:1 diet, we had done 6 months on the 3:1, and then a couple of months on the 2:1, when his sixth birthday was coming up. We asked him what he wanted, and he said pizza. Well, you’re nervous as can be, but he was doing so well that we decided to stop the diet on his birthday, before the full 6 months of the 2:1 were up. We invited all the neighborhood kids in, and I put candles in the pizza. After he took the first bite, he looked up at me and said, “Dad, this is the best birthday present I’ve ever had.”

It is natural for a parent to feel anxious when a child is going off the diet. After all that time spent planning and measuring food to an accuracy of a gram, it’s hard to kick the habit! All we can tell nervous parents is that ending the diet is to their child’s advantage once the child is seizure free for 2 years. The ketogenic diet therapy’s goal is to treat a problem—seizures. Once the problem is gone, the therapy should also end.

GOING OFF THE DIET WAS VERY LIBERATING. At last we could go places without planning and thinking about every meal. We could spend a day at the mall. She could go to parties and eat what the other kids were having. It was great. We still see our neurologist, but it’s in regular epilepsy clinic every few months. We ran into our dietitian at the mall several years later and gave her a big hug!

We know this is a tough moment for you. The diet is not like anticonvulsants—it requires lots of time and energy from parents and children. It also requires lots of work by the neurologists and dietitians who use it. We also find it hard to take our patients off the diet, and yes, we’re nervous too! Our final advice is this: (1) one change at a time, (2) keep in close contact with your ketoteam, and (3) have a plan just in case the seizures get worse. Good luck!