11

Contingency and Markets

ACCORDING TO OUR IKE model, prices and risk tend to undergo swings when trends in fundamentals persist for some time, which they do quite often, and market participants have no specific reasons to expect a change, and thus they are likely to revise their forecasting strategies in guardedly moderate ways. We would expect, therefore, that fundamental factors play an important role in driving asset-price swings and risk. We would also expect the set of fundamental factors and their influences to change over time.

Yet nearly all of the literally thousands of empirical studies make no allowance for any change in the way that fundamentals might matter for monthly or quarterly movements in asset prices. Instead, these studies estimate statistical models with fixed parameters over long stretches of time (in many cases, decades). Unsurprisingly, these empirical studies fail to find evidence that fundamentals matter.

The only sensible conclusion to draw from such fixed-parameter studies is that looking for overarching relationships in asset markets is futile. Instead, economists have largely concluded that factors other than fundamentals must move markets. Those who argue that bubbles and irrationality drive asset prices routinely appeal to these results to support their position.

Economists who continue to embrace the Efficient Market Hypothesis largely recognize that “we don't have…[a Rational Expectations] model yet” (Cassidy, 2010b, p. 3) that can account for asset-price swings and risk. But they point to an enormous amount of statistical research that they believe provides strong empirical support for the claim of the Efficient Market Hypothesis that available information cannot be used to earn above-average returns consistently (for review articles, see Fama, 1970, 1991). Researchers in the 1960s and 1970s examined short-term (daily, weekly, and monthly) asset returns and generally reported no discernable correlations in the data that could be used to beat the market. Researchers also found that mechanical trading rules based on past price trends were generally unable to produce profits on average and that mutual fund managers, as a group, were unable to generate average returns higher than those of passive funds based on a broad index. Economists concluded from this early evidence that “there is no other proposition in economics which has more solid empirical evidence supporting it than the Efficient Markets Hypothesis” (Jensen, 1978, p. 95).

More recent studies, which use more powerful statistical procedures and longer samples, have produced results that contradict the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Researchers have found what appear to be strong correlations in stock returns over the short term and long term (three to five years).1 They have also found that when stock prices relative to earnings or dividends are high compared to historical averages, returns tend to be below average over the subsequent three to ten years, which is just a reflection of the tendency of asset prices to undergo wide swings around benchmark levels (see Campbell and Shiller, 1988; Fama and French, 1988). In currency markets, studies report that future currency returns are correlated with available information on the forward premium (which we will define shortly) and suggest that a simple rule of betting against the prediction implied by the forward rate would deliver above-average returns.

Financial economists have engaged in an intensive search for an REH-based risk-premium model that could rationalize the more recent empirical results. They have failed so far, but they continue to hold out the possibility of eventual success. As the University of Chicago's John Cochrane put it, “That's the challenge. That's what we all work on” (Cassidy, 2010b, p. 3).

But that is not the challenge (and it is not what we all work on). Indeed, beyond its inability to account for asset-price swings and risk, there is something fundamentally absurd about the Efficient Market Hypothesis. It is based on the idea that individuals are profit-seeking, but it supposes that the masses of market participants who do use available information in an effort to earn above-average returns are merely wasting their time.

In contrast, behavioral economists point to the supposedly systematic patterns in returns, and the failure of standard risk-premium models to explain them, as additional evidence that asset markets are grossly irrational. But there is a fundamental absurdity here, too. Behavioral economists would not deny that professional participants in asset markets are not only profit-seeking but also extremely clever and highly compensated to find ways to outperform the market. Yet their theories suppose that markets offer profit opportunities—as simple to exploit as betting against the forward rate—which these masters of the universe somehow overlook.

As with the bizarre conclusion that fundamentals are unimportant for asset prices, the absurdities of both the Efficient Market Hypothesis and behavioral views stem from searching for fully predetermined models of asset returns. Almost all empirical evidence that both camps invoke to buttress their positions is based on seeking fixed patterns in the data. However, new technologies, institutional and policy developments, fresh ways of thinking about markets and the economy, and myriad other possible nonroutine changes lead to temporary but significant correlations in the data.

The temporary above-average returns that come from anticipating these correlations or spotting them early enough provide huge incentives for individuals to use available information to do so. To assume away these temporary returns, as proponents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis do, is to disregard the very basis for making profits in financial markets. Moreover, the importance of nonroutine change implies that there are no stable patterns in returns, and the claims of behavioral economists that they have discovered mechanical rules that deliver easy profits, yet participants leave them unexploited, are simply bogus.

CONTINGENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS

Markets play an essential role in modern economies precisely because change is “contingent”—it is “affected by unforeseen causes or conditions” (Webster's Unabridged Dictionary)—and knowledge is imperfect. This leads us to propose the Contingent Market Hypothesis as an alternative to the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Like the latter hypothesis, the Contingent Market Hypothesis supposes that

• The causal process underpinning price movements depends on available information, which includes observations concerning fundamental factors specific to each market.

However, in sharp contrast to the Efficient Market Hypothesis,

• This process cannot be adequately characterized by an overarching model, defined as a rule that exactly relates market outcomes to available information up to a fully predetermined random error at all time periods, past, present, and future.

Chapters 8, 9, and 10 showed how, with contingent change, asset-price swings are inherent to the process by which financial markets allocate capital and yet they sometimes become excessive. The Contingent Market Hypothesis has three additional implications. In presenting each, we discuss more fully how this alternative hypothesis accounts for the empirical evidence that has confounded the standard theory and how it leads to an intermediate view of the role of asset-price swings.

CONTINGENCY AND INSTABILITY

OF ECONOMIC STRUCTURES

Significant changes in the process driving asset prices occur at moments and in ways that cannot be fully foreseen. Such contingent change implies that the statistical estimates of fully predetermined models of asset prices vary in significant ways as the time period examined is changed. Correlations between price changes and informational variables that might be found in the data over some stretch of time eventually change or disappear and are replaced with new relationships.

Temporal instability is not difficult to find in asset markets. For example, Fama and MacBeth (1973) and others report favorable estimates of the Capital Asset Pricing Model, which is widely used in academia and industry, over a sample that runs until 1965. However, when the sample was updated to include the 1970s and 1980s, and additional variables were added to the analysis, the results led Fama to refer to the Capital Asset Pricing Model in a New York Times interview as an “atrocious…empirical model” (Berg, 1992, p. D1). Commenting in an interview with Institutional Investor on the temporal instability of correlations in asset-price data, Nobel laureate William Sharpe quipped that “[i]t's almost true that if you don't like an empirical result, if you can wait until somebody uses a different [time] period…you'll get a different answer” (Wallace, 1980, p. 24).

Given such temporal instability, looking for stable correlations between asset prices and variables in any information set, as most empirical researchers do, merely draws data from different sub-samples, each involving distinct correlations. Doing so is likely to conceal the nature of the correlations that might exist in the data during stretches of time between significant shifts in the causal process.

The Exchange-Rate Disconnect Puzzle

Nowhere is the futility of searching for the role of fundamentals with fully predetermined models more apparent than in currency markets. International macroeconomists routinely estimate fixed exchange-rate relationships in samples that run longer than two or three decades. Such empirical analysis presumes that market participants never revise their forecasting strategies, and that the policy and institutional framework remains unchanged. The results of this research are dismal, leading most researchers in the field to conclude that “exchange rates are moved largely by factors other than the obvious, observable, macroeconomic fundamentals” (Dornbusch and Frankel, 1988, p. 16).2

Meese and Rogoff's (1983) study is perhaps the most often cited as showing the supposed disconnection between exchange rates and fundamentals. They examined the performance of the most popular models, which relate the exchange rate to interest rates, national income, trade balances, and other fundamentals that are widely believed to underpin currency fluctuations. The authors estimated each model over an initial sample that ran from March 1973 through November 1976. They were interested in how well a model that was estimated on the basis of data during the initial period captured the influences of fundamentals outside of that period.

To answer this question, they used their initial parameter estimates to forecast the exchange rate over short horizons of one, six, and twelve months. A real forecasting exercise would, of course, also need to project the values of the fundamentals for the future dates of the forecasts. But to keep the focus of the exercise on whether the in-sample estimates could account for the influence of fundamentals out of sample, they used the actual future values of the fundamentals to obtain exchange-rate predictions. To produce a series of short-term exchange-rate forecasts from the models, Meese and Rogoff added to their initial sample observations beyond November 1976, one month at a time until June 1981, and at each step, they combined their in-sample parameter estimates with the actual future values of the fundamentals.

Meese and Rogoff's results had a profound impact on the literature. They found that none of the models examined produced exchange-rate predictions that would enable a forecaster to do any better than merely flipping a fair coin. This was the case even though the predictions of these models were based on the actual future values of the fundamentals. The results thus suggested that possession of such information provided absolutely no benefit to a forecaster. The implication drawn by most researchers in the field seemed obvious: fundamentals play absolutely no role in currency fluctuations.

There are literally hundreds of studies that have extended Meese and Rogoff's (1983) analysis to include newer exchange-rate models, more powerful statistical techniques, longer sample periods, and additional exchange rates. The results are largely the same as those of the original study (for a review, see Cheung et al., 2005). Appealing to such evidence, many international macro-economists continue to argue that short-term fluctuations in currency markets do not depend on macroeconomic fundamentals.

The Contingent Market Hypothesis implies a more plausible interpretation of the empirical record. Time-invariant and other fully predetermined probabilistic models simply provide an inadequate lens for examining the importance of fundamental factors for price fluctuations in financial markets. In these markets—where the imperfection of knowledge and psychological considerations underpin participants' trading decisions, and the policy and institutional framework undergoes nonroutine change—fundamentals matter, but in different ways during different stretches of time.

Contingent Change in Currency Markets

Although the causal process driving outcomes in currency markets changes at times and in ways that no one can fully pre-specify, there may be extended periods during which the non-routine change that does occur is sufficiently moderate that a relatively stable relationship between the exchange rate and a set of fundamental variables results. No one can foresee when such distinct periods might occur or how long they might last, let alone the precise nature of the fundamental relationships during those periods.

In fact, there are no strictly objective criteria, statistical or otherwise, to determine the precise nature of the fundamental relationship and points of change—breaks in the data when a new relationship arises—in the historical record. Different models and testing procedures will lead to different break points and estimated relationships. As with estimates of the Capital Asset Pricing Model in the stock market, empirical estimates of economists' exchange-rate models depend on the sample period used.

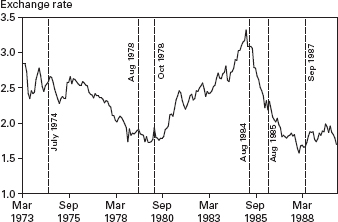

For example, in Frydman and Goldberg (2007, chapter 15) we suppose that the fundamental relationship driving the German mark-U.S. dollar exchange rate in any given period entails one or more of the fundamental variables implied by the exchange-rate models examined in Meese and Rogoff (1983). We use statistical procedures that enable us to approximate when this relationship may have changed over our sample without prespecifying the timing or nature of this change. Figure 11.1 plots the exchange rate and reports results of change tests; dotted vertical lines indicate break points.3

In all, we find six break points in our sample, which includes the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.4 Some of the breaks are proximate to major shifts in economic policy. For example, in October 1979, the U.S. Federal Reserve deemphasized the federal funds rate in favor of monetary aggregates as its primary operating target, and October 1985 was the month following the Plaza accord, which aimed at lowering the dollar's value. But other break points are not. No one can fully foresee shifts in monetary or fiscal policies, let alone the factors underpinning the other break points.

Fig. 11.1. Structural change results: German mark-U.S. dollar exchange rate relationship

The Disconnect Puzzle as an Artifact of the

Contemporary Approach

The results of the structural change tests suggest that there are distinct subperiods in the data or regimes during which the exchange-rate process is approximately stable. It thus makes little sense to estimate any fixed exchange-rate model over our entire sample. Indeed, doing so produces the same dismal results found by earlier researchers, suggesting that fundamentals do not matter at all.

However, a very different picture emerges when we examine separately the distinct fundamental relationships in the two extended regimes of the 1970s and 1980s. In each regime, we find that many of the fundamentals implied by economists' exchange-rate models matter in ways that are consistent with the qualitative predictions of these models.5 We also find that different fundamentals with different influences drive the exchange rate across the two regimes.6

The structural change results in Figure 11.1 show that three break points occur during the sample period underlying Meese and Rogoff's (1983) forecasting exercise. Their results, therefore, have little significance for understanding exchange-rate fluctuations. Indeed, our estimated fundamental relationship for the 1970s regime (which runs from July 1974 through September 1978) outperformed the coin-flipping strategy for forecasting by considerable margins, but only if we restrict the analysis to the 1970s regime. For example, the fundamental model was able to predict correctly the direction of change of the exchange rate 100% of the time at the six-month, nine-month, and 12-month forecasting horizons.7

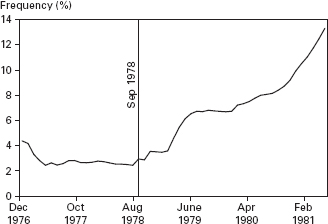

Figure 11.2 shows the basic problem posed by instability for the Meese and Rogoff (1983) analysis. The figure plots a measure of the forecasting error at the three-month horizon of the fundamental model estimated for 1970s regime.8 Prior to the regime change in October 1978, the model's forecasting error is consistently less than 2.5%, which is less than half the 6% forecasting error produced by flipping a coin. However, after the point of change, another set of fundamentals with different influences drives the exchange rate. Unsurprisingly, the forecasting error of the estimated model prior to the break point deteriorates markedly once change occurs, far surpassing the error from coin flipping.

Fig. 11.2. Pre-and post-break performance of the fundamental model

Meese and Rogoff (1983) report only the average of the forecasting errors generated by exchange-rate models over the entire sample, which combines the stellar forecasting performance prior to the point of change with the dismal errors that followed it. This practice merely conceals the significance of fundamentals in driving currencies in nonroutine ways both before and after the point of change.

THE FLEETING PROFITABILITY OF

MECHANICAL TRADING RULES

As with estimated relationships between asset prices and fundamentals, contingent change implies that any fully prespecified trading rule that generates above-average returns over some past stretch of time, after accounting for risk, will eventually cease to do so. This implication goes a long way toward resolving one of the core “puzzles” in financial economics.

Early studies of the performance of trading rules that extrapolate past price trends found little evidence that they delivered any profits at all (for a review, see Fama, 1970). However, more recent studies, which have looked at a much wider array of technical rules and trading horizons, claim that rules based on intraday horizons do generate above-average returns after accounting for risk.9Economists have also estimated fixed-parameter models of asset returns and report apparently stable patterns in the data that could be used to earn above-average returns after accounting for risk.

According to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, all such trading-rule profits and patterns should be quickly arbitraged away. Economists' apparent discovery of them suggests that they are not. Conventional economists have been searching for decades for an REH-based risk-premium model that could rationalize the supposed profitability of their rules and stable patterns in returns. Having accepted the Rational Expectations Hypothesis as the standard of rationality, behavioral economists have interpreted the failure of this effort as another indication of the irrationality of asset markets. They have also been at work over the past two decades developing an array of fully predetermined accounts of such behavior.

Of course, one can search for fixed trading rules that are profitable and for correlations between asset returns and available information during some past stretch of time, and find what looks like profitability and stable patterns. But the contingent change that characterizes markets (and capitalist economies more broadly) implies that fixed trading rules will eventually lose their profitability, and past correlations will eventually change at times and in ways that no one can fully foresee.

To be sure, many participants in financial markets use technical trading rules. However, there is much evidence that these rules are used in nonmechanical ways. Even dealers in currency markets, who trade over very short horizons, combine them with considerations based on fundamental and psychological factors in ways that change over time.10 Using technical rules requires intuition and the skill to know which rules to use and when to use them: as Menkhoff and Taylor (2007, p. 947) conclude in their review article, “the performance of technical trading rules is highly unstable over time.”

This result is not surprising, given that economists' fixed-parameter models of returns are also temporally unstable. Fama and French (1988), for example, report that stock portfolios with positive returns over the preceding three to five years tend to produce negative returns over the subsequent three to five years, and vice versa.11 However, when they deleted the first part of their sample, the negative relationship largely vanished.

Campbell and Shiller (1988) report that when stock prices relative to earnings or dividends are high compared to historical averages, real returns tend to be below average over the subsequent three to ten years.12 But these results do not provide a mechanical way to beat the market. For example, the price-earnings ratio on the S&P 500 basket of stocks in January 1997 stood at a record-high 28. Campbell and Shiller (1998) report that at this level, their analysis implied a prediction of a negative 40% real return on holding the S&P 500 stocks over the next ten years. Although stock prices fell considerably from 2000 to 2003, they were back up by January 2007: over the ten-year period, an investor would have earned a respectable real annual return of 4.6%. Timing when to buy and sell is essential, and one would not want to rely solely on a mechanical relationship between price-earnings ratios and returns based on historical data.

What appear to economists to be easy ways to make money are nothing more than temporary mirages. That participants in financial markets do not avail themselves of these supposed opportunities is a testament not to their irrationality, but to common sense: they simply cannot afford to stick to one fixed rule endlessly. The enormous amount of time, energy, money, and other resources that economists have devoted to explaining their findings on returns is a prime example of how economists' insistence on searching for fully predetermined models has impeded progress in economics.

The Forward-Discount Anomaly

Perhaps the best illustration of the fleeting nature of the profitability of fixed trading rules—and of how insisting on fully predetermined models leads to an intellectual cul de sac—is found in the literature on modeling returns in currency markets.

In hundreds of studies, international macroeconomists have looked for a fixed correlation in monthly data between the value of the forward premium at the beginning of the month and the future return on holding foreign exchange over the month.13Almost all these studies report a significantly negative correlation between these variables. As two of the leading researchers in the field put it, “What is surprising is the widespread finding that realized [currency returns]…tend to be, if anything, in the opposite direction to that predicted by the forward premium” (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1996, p. 589; for reviews, see Lewis, 1995; Engel, 1996).

To see what this result would mean if it were consistently true, consider a typical forward contract for a currency. This contract enables its holder to lock in today the price at which she buys or sells a certain dollar value of foreign exchange in the future, for example, in one month. This price, say, $1.20 per euro, is called the forward rate. If today's forward rate is higher than today's spot rate, then foreign exchange (the euro in our example) is said to be trading today at a forward premium. For example, if one could enter into a spot contract today to buy the euro for $1.00—the spot rate—then the euro would be trading at a forward premium of 20%. If this premium were negative instead of positive, the euro would be said to be trading at a forward discount.

Whether one could make profits on average by using forward contracts depends on how the forward premium covaries over time with the future one-month return on holding foreign exchange. If a rise in the forward premium tends to be associated with a negative return, and if this correlation is stable, as economists claim it to be, then “one can make predictable profits by betting against the forward rate” (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1996, p. 589). The trading strategy is particularly simple: if the forward premium is positive, one should bet on a fall in the spot rate over the coming month, whereas if the opposite is the case, bet on a rise in the spot rate. This rule involves no sophisticated statistical analysis and the collection of only one piece of information, the forward premium.

International economists have undertaken an enormous effort to rationalize the supposedly negative correlation between returns and the forward premium with an REH-based risk-premium model. However,

there is no positive evidence that the forward discount's [correlation] is due to risk Survey data on exchange rate expectations suggest that the bias is entirely due to expectational errors….Taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that explanations which allow for the possibility of market inefficiency should be seriously investigated. [Froot and Thaler, 1990, p. 190]

As a result, economists have developed several fully predetermined accounts of the supposed irrationality of currency markets (for example, see Mark and Wu, 1998; Gourinchas and Tornell, 2004).

But it is such efforts, not the profit-seeking motive in currency markets, that should be questioned. Consider that the foreign-exchange market is the largest financial market in the world, with a daily volume now estimated to be more than $3 trillion. The stakes in this market, as in any other large asset market, are extremely high. Financial institutions, which hire many of the participants who move the markets, pay large sums of money to attract the best and the brightest. Is it really possible that these individuals can make money by following a rule as simple as betting against the forward rate, and that they are either unaware of this opportunity or fail to exploit it?

In fact, currency returns do not unfold in conformity with an overarching rule. Instead, revisions of participants' forecasting strategies or shifts in the process driving the forward premium lead to nonroutine changes in the correlation between returns and the forward premium (and any other informational variable, for that matter).14 Unsurprisingly, the data bear this out: the correlation is largely negative during some stretches of time and largely positive during others, implying that always betting against the forward rate will sometimes deliver profits and at other times losses.15 No one can precisely specify ahead of time when the correlation might be negative and for how long, so no one can foresee when it might be profitable to bet against or with the forward rate.

As we would expect with such contingent change, successful speculation in currency markets is not as simple as suggested by the voluminous academic literature on international finance. Indeed, we report in Frydman and Goldberg (2007, chapter 13) that “predictable profits” cannot be made by simply betting against the forward rate. Although this rule delivers profits in some sub-periods for some currencies, it stops being profitable at moments of time that cannot be foreseen by anyone. And we find that any profits delivered by the rule are not large enough to provide reasonable compensation for uncertainty.

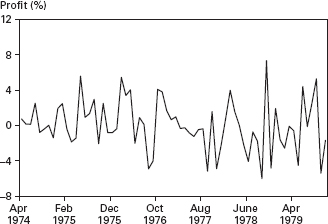

Fig. 11.3. Profits in the British pound market, 1970s

Source: Frydman and Goldberg (2007).

Figure 11.3 illustrates the fleeting nature of the profitability of economists' forward-rate rule. It plots the monthly profits that one would have earned by betting against the forward rate in the British pound market during the 1970s. There are periods of profitability, but they are fleeting. Over the entire period, the average return is zero.

Of the hundreds of studies that have reported a supposedly negative correlation between currency returns and the forward premium, very few examine the behavior of this correlation over separate subperiods of the data sample, let alone formally test whether it is stable over the entire sample. Of course, those that do so find evidence of instability.16 But as with the evidence of unstable exchange-rate relationships, the insistence on considering only fully predetermined, mostly invariant relationships has led economists to ignore their own findings.

TEMPORARY PROFIT OPPORTUNITIES

Although contingent change implies that mechanical trading rules will eventually cease to be profitable, such change alters the correlations in the data, which for a time opens up temporary profit opportunities. Those who gather information and have the skill and flexibility to revise their thinking in ways that enable them to spot or anticipate these opportunities are able to earn above-average returns after adjusting for risk.

When modeling asset price swings in Chapters 9 and 10, we made use of Keynes's (1936, p. 152) insight that when forecasting future prices and risk, participants rely on “a convention…[of] assuming that the existing state of affairs will continue indefinitely, except in so far as we have specific reasons to expect a change.” But because the process driving market outcomes undergoes contingent change, it is unclear how much past data a participant should use to understand the existing state of affairs, let alone forecast how long it might continue. As we saw, even the most sophisticated statistical techniques do not automatically pinpoint when the current state of affairs began. Of course, the choice among various alternative models also requires subjective judgments. Even when describing the past, interpretations vary among individuals, depending on their personal knowledge, experience, and intuitions.

Participants understand that “the existing state of affairs” will eventually change. In stock markets, for example, a company's prospects evolve over time in nonroutine ways that become more difficult to assess as one looks farther into the future. Movements of fundamentals—such as earnings, interest rates, and overall economic activity—provide clues to potential changes in these prospects. As investors alter their understandings and assessments about the future, they influence the process driving prices. Such contingent change leads to new states of affairs: new correlations between fundamentals and future outcomes emerge, and old ways of thinking lose their forecasting power.

Spotting such new correlations even after they have occurred is no easy task. A participant might rely on statistical techniques, but it is unclear which ones to use and how to apply them. Moreover, some amount of time must elapse after a change has occurred for these techniques to have a chance of picking it up. Participants, therefore, may want to rely more on their intuition about recent news in discerning whether significant change has occurred.

Anticipating change is even more difficult. As Keynes (1936, p. 163) so clearly understood, we “[calculate] where we can,” in making decisions, but participants fall back on other considerations, including intuition, “confidence with which we…forecast,” and optimism.

New correlations imply above-average returns for those who can discern them quickly using available information, and even higher returns for those who can anticipate them to some extent. The promise of above-average returns provides the incentive to comb over company data, study industry trends, and purchase the services of Bloomberg LP and other companies devoted to providing news and market analysis. Participants often combine quantitative models with their own insights concerning other traders' behavior, the historical record on price fluctuations, and their evaluations of the impact of past and future decisions by policy officials. And because they act on the basis of different experiences, interpretations of the past, and intuitions about the future, they adopt different strategies to spot and anticipate contingent change. Doing so consistently is extremely difficult, but not impossible. Warren Buffett and George Soros immediately come to mind as two investors who have shown such skills.

For proponents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, such informational gathering and fundamental analysis is a waste of time and resources; individuals should instead invest in a well-diversified portfolio. They readily admit that many participants do engage in fundamental analysis, and that some have been able to earn above-average returns consistently. As Michael Jensen, a leading proponent of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, argued in a debate with Warren Buffett, “if I survey a field of untalented analysts all of whom are…flipping coins, I expect to see some…who have tossed ten heads in a row” (Lowenstein, 1995, p. 317).

Warren Buffett rejected the coin-flipping story as an explanation of his success. As he put it, “if 225 million orangutans had engaged in [stock picking]…the results would be much the same [as flipping a coin],” but too many of the successful orangutans, “came from the ‘same zoo'” (Lowenstein, 1995, p. 317).

To be sure, Buffett would not claim that the mere fact of using fundamental analysis necessarily implies an ability to beat the market. Ultimately, good forecasting is much like good entre-preneurship: it involves one's own knowledge, intuition, and hard work to spot and anticipate the profit opportunities that come from contingent change. The insight that such endeavors cannot be preprogrammed lay behind Hayek's argument that central planning is impossible in principle.

Thus, we would not expect that all or even most mutual fund managers could anticipate correctly future changes in the market or the economy consistently over time, which is exactly what the literature has found. But the fact that it is possible, and that some individuals do succeed, provides powerful incentives to look for signs of change and attempt to speculate on them.

AN INTERMEDIATE VIEW OF MARKETS AND A

NEW FRAMEWORK FOR PRUDENTIAL POLICY

Once we recognize that fundamentals matter, but in non-routine ways, markets are seen as neither near-perfectly rational and efficient, as supposed by the Efficient Market Hypothesis, nor grossly irrational and inefficient, as implied by the behavioral finance models.

Our intermediate position has allowed us to uncover the key importance of nonroutine movements of fundamentals and the mediating role of psychology for understanding price swings and risk in financial markets. In addition, it enables us to show that many empirical puzzles that have been identified by researchers are not anomalies—they are merely artifacts of the disconnect between fully predetermined models and what markets in the real world do.

Our intermediate view of markets not only sheds new light on the supposed empirical puzzles implied by fully predetermined models, but it also leads to a new way of thinking about the relationship between the market and the state. The nonroutine role of fundamentals in driving swings and financial risk and our analysis of its implications for the instability, excessiveness, and allocative function of financial markets lead to a new rationale for state intervention. Our view also opens up new channels for policymakers to limit the magnitude of long swings in asset markets and leads to a new way for regulators to assess systemic and other risks in the financial system.

1For short-term correlations, see Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) and Lo and MacKinlay (1999). For long-term correlations, see De Bondt and Thaler (1985) and Fama and French (1988).

2See Frankel and Rose (1995) and Frydman and Goldberg (2007, chapter 7) for overviews of this literature.

3The analysis makes use of the CUSUM test of Brown et al. (1975). For more details, see Frydman and Goldberg (2007, Chapters 12 and 13).

4Many other studies also find temporal instability in currency markets. See Boughton (1987), Meese and Rogoff (1988), Goldberg and Frydman (1996a,b, 2001), Rogoff and Stavrakeva (2008), and Beckman et al. (2010).

5To specify these qualitative predictions, we make use of the Theories-Consistent Expectations Hypothesis proposed by Frydman and Phelps (1990). This hypothesis is based on the idea that economists' models summarize their qualitative insights concerning the causal mechanism underpinning market outcomes and that, presumably, these insights are shared by market participants. Economists usually have several models of an aggregate outcome. Thus, representations of forecasting behavior based on this hypothesis make use of several economic models rather than relying on just one. In Frydman and Goldberg (2007, chapter 10) we show how this can be done, even if the qualitative features of a set of extant models conflict with one another.

6For a recent study that also finds that different fundamentals matter during different periods, see Beckman et al. (2010).

7For a recent study that also finds forecasting performance to depend on the period studied, see Rogoff and Stavrakeva (2008).

8The figure is based on root mean square error. See Meese and Rogoff (1983) for details.

9See Schulmeister (2006). For a review, see Menkhoff and Taylor (2007).

10See the survey studies of Cheung et al. (1999), Cheung and Chinn (2001), and Menkhoff and Taylor (2007).

11De Bondt and Thaler (1985) showed much the same result.

12Fama and French (1988) find similar results.

13Most studies in the literature examine the correlation between the forward premium and the future change in the spot exchange rate. However, the correlation with returns, which depend on changes in the spot rate, provides an exactly equivalent way to present the forward-discount anomaly while simplifying our discussion.

14We show this result formally in Frydman and Goldberg (2007, chapter 13).

15We find such instability in the British pound, German mark, and Japanese yen markets over a sample period that includes the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Other studies that also find results that depend on the subperiod examined include Bekaert and Hodrick (1993), Lewis (1995), Engel (1996), and Mark and Wu (1998).

16Studies that split their samples include Bekaert and Hodrick (1993), Lewis (1995), Engel (1996), and Mark and Wu (1998). Only Bekaert and Hodrick (1993) formally test for stability.