How to Write About Contemporary Art

‘Art-writing is an anthology of examples.’

MARIA FUSCO, MICHAEL NEWMAN, ADRIAN RIFKIN, AND YVE LOMAX, 201152

So claims horror novelist Stephen King, and this gothic-inflected observation may hold doubly true for bad art-writing.53 The most quixotic press releases, baffling academic essays, and punishing wall texts are often written by the art-world’s most frightened initiates: interns, sub-assistants, and college kids, cutting their art-writing teeth. They are not just inexperienced; they are terrified about:

+ sounding stupid

+ displaying ignorance

+ missing the point

+ getting it wrong

+ having an opinion

+ disappointing their supervisor

+ making choices

+ questioning the artist

+ leaving things out

+ being honest.

Fear accounts for the common sightings of what I call a ‘yeti’: the all-too-common, Janus-faced art description:

‘familiar yet subversive’

‘intriguing yet disturbing’

‘bold yet subtle’

‘comforting yet disquieting’.

These self-contradicting, hedged adjectives reflect a writer wracked with worry, unable to commit to a single descriptor, hiding behind the ambiguity of art to escape staking a position. Like the mythical big-footed beast, a ‘yeti’ is impossible to pin down, and vanishes into nothing if you attempt to observe it closely. Usually, weak art-writing does not fail because the writer boldly attempted to express their art experience, and fell short. No; fledgling art-writers are so overcome by the task—writing thoughtfully about their experience of art—that they abandon this endeavor before even trying. They take all sides, or seek refuge in ‘conceptual’ padding (‘the demands of Greenbergian dogma’) and stock concerns (‘the complexities of life in the digital age’). Be brave, look at the art, and train yourself to write simply, only about what you know. Just by trusting yourself—and becoming informed—your texts will improve dramatically.

> The first time you write about art

Like writing about sex, verbalizing an art experience always verges on the overwritten embarrassment. No one excels at art-writing from their earliest attempt. Have a read of the comments scrawled on blogs or in gallery visitors’ books to know what untutored art-writing sounds like:

‘Thank you! Wonderful  ’

’

‘A waste of taxpayers’ money’

‘What a magnificent way to work with chicken wire’54

Everyone’s first attempt at substantial art-writing is a tortuous endeavor. To cope, one might resort to echoing whatever’s on the press release or website: ‘Cindy Sherman’s photographs deconstruct notions of the male gaze’, that sort of thing. This parroted art-talk is as unsatisfying for you to write as it is for anyone to read.

Virgin art-writing usually begins with a phrase like, ‘When I first entered the gallery, I was struck by…’. Venturing further—though omitting to describe the exhibition—the novice instantly forgets the art, and lets memory take him…somewhere else. The discussion becomes all about the writer, not the art, and swamped beneath a rush of ill-formed notions, anecdotes, half-baked interpretative angles, and inexplicable associations, all plagued by the writer’s uncertainties:

+ where to start?

+ how many, and which, artworks to discuss?

+ how to balance description and factual information about the artist/exhibition?

+ where to inject my own musings?

In an attempt to ‘cover everything’ the newcomer tosses in a slew of worn, abstract notions such as:

‘subversion’

‘disruption’

‘formal concerns’

‘displacement’

‘alienation’

‘today’s digital world’.

Concepts pile up like colliding automobiles in a wreck, flying off in every direction, leaving a trail of unresolved ideas in their wake. As the last paragraph approaches, the flagging writer—aware he has little left in the tank—will tack on a panic-stricken finale involving a complete or partial reversal. Initial impressions are dramatically deepened or dimmed with the revelation that the artwork/exhibition/experience was not as initially imagined. It was deep rather than superficial, traditional rather than unfamiliar. It was flat yet round, open yet closed, painting yet photography, personal yet academic, ad infinitum, as the writer attempts a budding stab at an original idea. This incipient thought, alas, leads nowhere. The writer will omit the actual title of a single artwork, misspell the artist’s name (twice), and forget to sign his own.

Most of us have written a lame art-text like this; there is no shame in taking your first baby steps. This is probably a necessary rite-of-passage in every art-writer’s life-cycle, but reflects a tadpole phase you want rapidly to outgrow, because this type of early text

+ does not reflect or deepen the experience of art, but only solves the problem of writing about it;

+ has nothing to do with the art, but only with the writer;

+ cannot trace for the reader how conclusions were reached;

+ ignores the reality that most art experiences change in meaning the more you think about them. (Even bad art changes over time, proving more shallow and detestable when you are forced to spend time with it.)

You want to start where the beginner’s text ends. Drop the first three paragraphs and keep only the last—albeit preserving, and probably expanding, the descriptive prologue. Once your prolonged art-looking begins to mature, winnow down most of the preamble, and think through your own viable idea. Start there.

In truth, that business about the text having ‘nothing to do with the art but only with the writer’ is, actually, what art-writing is always, inevitably, about: its writer. Wicked reviews mostly reflect the reviewer’s own foul mood (although bad art can exacerbate an incipient migraine). As you continue art-writing, you will learn to obscure—or exploit—this fact. But be warned: indulging in your idiosyncratic mood swings can turn ugly. Ignoring your gut reaction, however, is to blame for much of the tiresome art-writing out there. Where your own opinion is not requested, such as wall labels or institution websites, push your ego gently aside and research hard information, specific facts. In every case, really know what you are writing about.

> ‘The baker’s family who have just won the big lottery prize’

One memorable example of first-rate art-writing was composed over 100 years ago. This gem is fewer than a dozen words in length, and attributed to 19th-century writer Lucien Solvay (among others) commenting on Francisco Goya’s The Family of Carlos IV (c. 1800; fig. 4), who are described as:

The baker’s family who have just won the big lottery prize.55

This tiny snippet synthesizes what the artwork looks like, why it’s meaningful, and the bigger implications of the painting, too. For Solvay, this royal group looked like ‘the grocer’s family…on a lucky day’, a phrase later polished to its well-known form.

Keep it simple. ‘Omit needless words.’56

Why might this razor-sharp mid 19th-century comment prove exemplary for the budding art-writer today? Because:

+ this phrase employs few, ordinary words. It does not say: ‘Collectively, we, politically savvy onlookers, are free to imagine another, perhaps more deprived, class of family—possibly engaged in some non-regal profession or pedestrian trade such as the vending of baked goods—enjoying the luxuries and splendor that good fortune might gift en masse to its unsuspecting, lucky-ticket-holding recipients.’

+ it pulls together what the picture looks like (an overbred, overdressed family) with what it may mean (these people aren’t ‘regal’, just lucky). Looking at the painting, we are not mystified as to how Solvay landed upon this idea, but instantly comprehend his words. We enjoy the art more thanks to this keen-witted observation.

+ it has been worded with care, and features concrete nouns. Solvay’s ‘grocer’ was good, but the later ‘baker’ is bang on target, resonating in the King’s doughy face, the Queen’s baguette-like arm. The wealth of visual details that Goya piled into the picture—which we can plainly see—substantiate the writer’s ideas about this art.

fig. 4 FRANCISCO GOYA, The Family of Carlos IV, c. 1800

+ it situates the art within a bigger world picture. ‘Lottery’ hits the bulls-eye. Goya’s political point might be: ‘This is no divine family! These are ordinary folk who randomly won “the lottery of life”, ruling our country generation after generation. Let’s revolt!’ 57 After-effects of the surprise windfall might explain the wide-eyed, startled look on the Queen’s multi-chinned face, and all those round, vacant eyes, as if caught by surprise. The closer we look at this painting, the more these imaginative words add to our enjoyment of the work.

+ it does not exclude other responses to the art. Like the artist, this writer was fearless and original, taking a risk. These words are so inventive, so unexpected, they encourage others to think about this painting creatively for themselves. Solvay’s interpretation may be a cracker, but it is not the final word, and it invites other onlookers to match his imaginative wit.

Certainly, the power behind this comment owes everything to the quality of Goya’s superb painting. Art-writers are perpetually at the mercy of what critic Peter Plagens has called the timeless art ratio, ‘10% good art: 90% crap’.58 It is no easy task to write a smart, supportive text about barren, uninspired work. Such writing will sound like hokum, because it is. Write first about artists whom you genuinely revere, the art you most believe in, so you don’t have to fake it. And if a work fails, say so with gusto. Faked feelings rarely produce good writing.

As a rule, dial down any bloated and grandiose statements:

‘This art overturns all definitions of visual experience’

‘This video questions all assumptions of gender identity’

‘Viewing this art, we question our very being, and ask ourselves what is real, and what is not.’

Get a grip. Very rarely, great art and poetry can aspire to feats of this magnitude; an overexposed Polaroid of the artist’s bull-terrier probably does not, and should not be burdened with such weighty expectations. You can support art without prostrating yourself before it.

Your first question when approaching any piece of art-writing might be: how much of my opinion is required here? Secondly, do I know enough to make my contribution worth reading? In all cases—whether evidence-led (explaining), opinion-led (evaluating), or mixed—your texts will only stand up if you can substantiate your claims (see section 2.2).

The three jobs of communicative art-writing

All art-writers can concoct a written response to art (the easy part). Good writers show where that response came from, and convince of its validity (the hard part; discussed in more detail in ‘How to substantiate your ideas’). Communicative writing about artworks breaks down into three tasks, each answering a question:

Q1 What is it?

(What does it look like? How is it made? What happened?)

Job 1: Keep your description of the art brief and be specific. Look closely for meaningful details or key artist decisions that created this artwork, perhaps regarding materials; size; selection of participants; placement. Be selective; avoid overindulging in minutiae, or producing list-like descriptions that are cumbersome to read and largely inconsequential to job 2.

Q2 What might this mean?

(How does the form or event carry meaning?)

Job 2: Join the dots; explain where this meaningful idea is observed in the artwork itself. Weak art-writers will claim great meanings for artworks without tracing for the reader where these might originate materially in the work (job 1) or how they might connect to the viewer’s interests (job 3).

Q3 Why does this matter to the world at large?

(What, finally, does this artwork or experience contribute—if anything—to the world? Or, to put it bluntly: so what?)

Job 3: Keep it reasonable and traceable to jobs 1 and 2. Answering this final question—‘so what?’—entails some original thought. And remember that the achievements of even good art can be relatively modest; that’s OK.

> The three jobs of communicative art-writing

Here is a short extract from a catalogue text by critic and curator Okwui Enwezor.

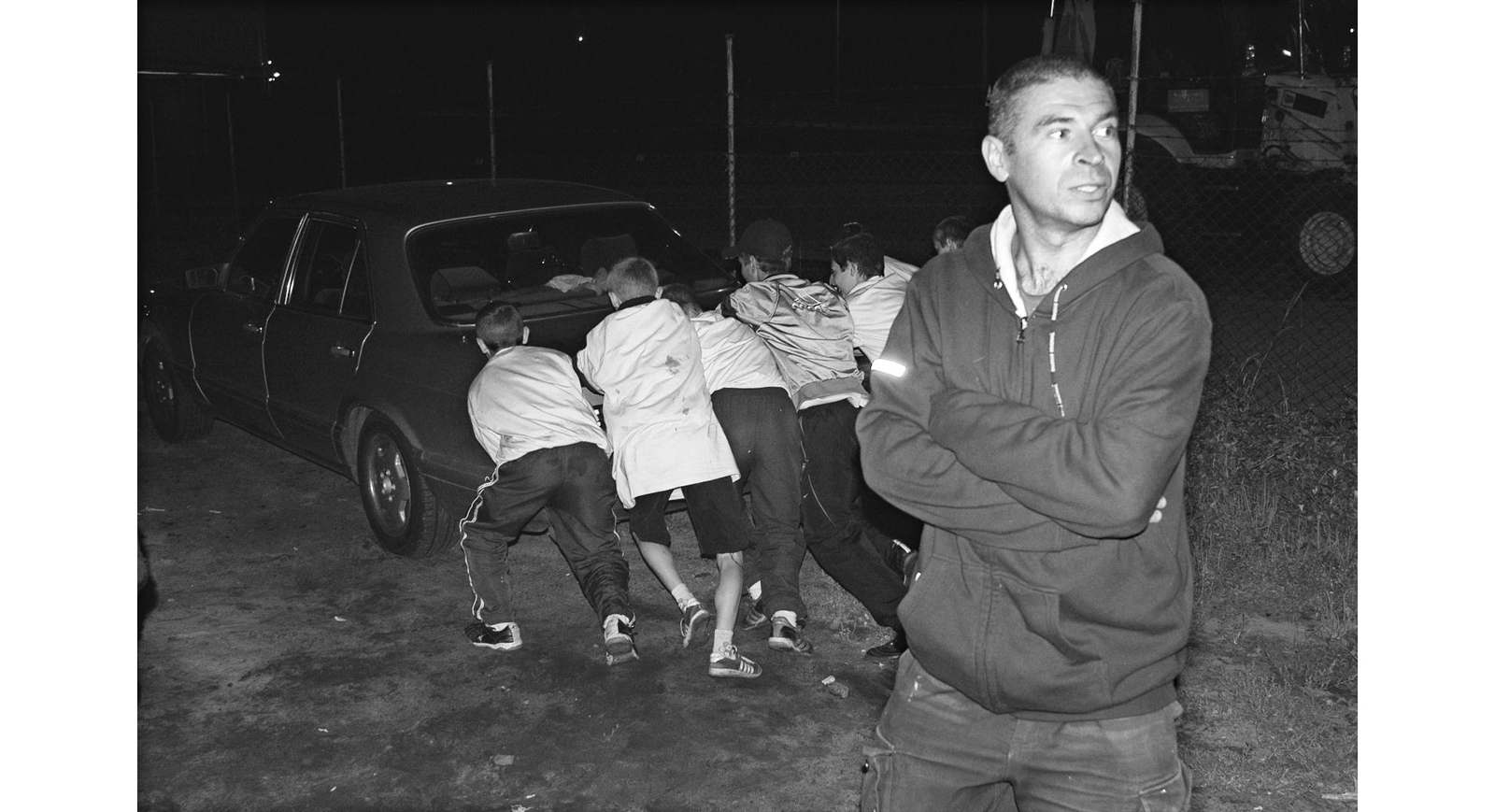

In the late 1970s, [Craigie] Horsfield commenced one of the most sustained and unique artistic investigations around the governing relationship between photography and temporality. Working with a large-format camera, he traveled to pre-Solidarity Poland, specifically to the industrial city of Krakow, then in the throes of industrial decline and labor agitation [2]. There he began shooting a series of ponderous and, in some cases, theatrically anti-heroic black-and-white photographs comprising portraits, deserted street scenes and machinery [1]. Printed in large-scale format [1], with tonal shifts between sharp but cool whites and velvety blacks, these images underline the stark fact of the subject, whether its of a lugubriously lit street corner or a solemn, empty factory floor, or portraits of young men and women, workers and lovers [1]. The artist worked as if he were bearing witness to the slow declension of an era [3], along with a whole category of people soon to be swept away by the forces of change […] With their stern, stubborn mien, they stand before us as the condemned [3].’

Source Text 2 OKWUI ENWEZOR, ‘Documents into Monuments: Archives as Meditations on Time’, in Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument, 2008

How exactly does Enwezor’s text fulfil the basic expectations of communicative art-writing? He answers three questions (see ‘The three jobs of communicative art-writing’):

Q1 What is it? What does the artwork look like?

A Enwezor describes what appears in the images, as well as the photographs’ size and technique [1].

Q2 What might the work mean?

A The writer explains in brief the artist’s project [2].

Q3 Why does this matter to the world at large?

A Enwezor’s original interpretation is that Horsfield’s ‘unique artistic investigations’ did not just document the decline of an era, but immortalized those doomed to go down with it: Horsfield’s subjects appear as if resigned to death row [3].

If you favor a clipped journalistic style, you might balk at ‘relationship between photography and temporality’ or ‘theatrically anti-heroic’, but Enwezor always returns to the actual artwork in order to move his thinking forward and prevent lapsing into meaninglessness. You may not agree with Enwezor’s conclusion, and can freely re-interpret Horsfield’s portraits (fig. 5) in your own terms; but the writer has taken the reader step-by-step through his knowledge and his thinking to substantiate his interpretation.

Even Walter Benjamin’s far-flung interpretation of Paul Klee’s drawing Angelus Novus explains how this tiny smiling angel became the linchpin in his philosophy of history, and fulfils the art-writer’s three-part job. (See Source Text 1 and fig. 3.)

fig. 5 CRAIGIE HORSFIELD, Leszek Mierwa & Magda Mierwa – ul. Nawojki, Krakow, July 1984, printed 1990

Q1 What is it? What does the artwork look like?

A ‘A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating.’

Q2 What might this mean?

A ‘This is how one pictures the angel of history.’

Q3 Why does this matter to the world at large?

A ‘[H]e sees one single catastrophe […] what we call progress’—a ‘progress’ that always smashes what was once whole, leaving behind a heap of debris that gathers lost histories.

This is heady, speculative stuff, but Benjamin traces how his immense re-conceptualization of all history was launched by the little Klee figure floating before him.

New art-writers usually find this part tricky: how do you strike the right balance between visual description, factual research, and personal input (or one’s own imaginative spin)? Other immediate questions that you might have:

+ this is art we’re talking about; can’t I just write whatever pops into my head?

+ isn’t my opinion as valid as anybody else’s?

+ why do I need to do research?

Presumably, if you are reading this book, your aim is to produce strong, persuasive art-writing rather than just scrawl ‘Thank you! Wonderful  ’ in a gallery visitor’s book. The difference between the two is: substantiation.

’ in a gallery visitor’s book. The difference between the two is: substantiation.

Substantiation explains where your ideas came from: your reader feels illuminated by your words, not frustrated. Substantiation is the difference between a gallery puff piece, gushing over how ‘wonderful’ and ‘alluring’ the art is, and a believable text that allows the reader to see the art afresh. Substantiation is what makes ‘the baker’s family who have just won the big lottery prize’ as a response to Goya’s portrait so terrific. I can see where the writer found that idea in the over-carbed appearance of those pudgy royal limbs and necks, or the assortment of badges, sashes, and medals flourishing on the King’s prodigious chest, so shiny they look purchased the day before. (Francisco Goya’s The Family of Carlos IV, c. 1800, as described by writers including Lucien Solvay, see fig. 4.) Substantiation turns watery artspeak into wine. The two main ways to substantiate art ideas are:

+ by providing factual or historical evidence: doing research, the backbone of academic writing and quality journalism;

+ on the basis of visual evidence: extracting information from the artwork itself.

Either way, the good art-writer substantiates ideas by paying close attention, and by tracing the logic of their thoughts, from artworks to art-words. These two forms of evidence—material evidence in the artwork, or in its history—can be combined and prioritized in myriad ways, but they usually uphold the most persuasive art thinking.

> Provide factual or historical evidence

This is key for academic writing. The following text by art historian Thomas Crow is steeped in valid historical evidence.

Painters and sculptors coming of age in California shared all of the marginalization [1] experienced by Johns and Rauschenberg in New York, but they lacked any stable structure of galleries, patrons, and audiences that might have given them realistic hopes for worldly success. The small audience they did possess, particularly in San Francisco, tended to overlap with the one for experimental poetry, and in both the majority was made up of fellow practitioners. One couple, composed of a poet, Robert Duncan (1919–88), and the artist Jess (b. 1923), provided a focus for this interaction from the early 1950s. Duncan had distinguished himself in 1944 by publishing an article in the New York journal Politics entitled ‘The Homosexual in Society’ [2], in which he argued that gay writers owed it to themselves and their art to be open about their sexuality […].

Jess began in the early 1950s to work toward forbidden areas of reference [3], in collages drawn from everyday vernacular sources. One of the earliest, The Mouse’s Tale of 1951/54 [fig. 6], conjures a Salvador Dalíesque nude giant from several dozen male pin-ups [3].

Source Text 3 THOMAS CROW, The Rise of the Sixties, 1996

In substantiated texts such as Crow’s, even abstract concepts such as ‘marginalization’ [1] are supported by evidence, in this case the backlash resulting from Duncan’s 1944 article in defense of openly homosexual writing [2]. Along with historical facts, ideas can be rooted in visual evidence; Crow hones in on a specific collage by Jess, The Mouse’s Tale, and pinpoints the elements that prompted an unfavorable reaction [3]. Crow’s text is top-notch art-history writing: its content is informed and specific (all dates; artwork titles, exact publications are given) and this hard information forms the basis of his interpretation. He makes every word count.

fig. 6 JESS, The Mouse’s Tale, 1951/54

> Beware of unsubstantiated waffle

Every sentence in convincing academic art-writing introduces new information and supports a meaningful point. ‘Waffle’ is overwritten and emphatic text, puffed up with—

+ platitudes and partial information;

+ unnecessary words and banal repetition;

+ common (or assumed) knowledge;

+ throwaway references and empty name-dropping;

+ conceptual padding and clumsily applied theory.

‘Waffle’ is weak text, because it raises more questions than it answers.

Waffle: |

‘Aside from the important and well-known artists in New York…’ |

|

Q |

Which important and well-known artists? |

|

A |

Substantiated text: ‘Johns and Rauschenberg in New York…’. |

|

Waffle: |

‘Californian artists achieved much less recognition than their East Coast counterparts.’ |

|

Q |

Why did the Californian artists achieve less recognition than those in New York? |

|

A |

Substantiated text: ‘Painters and sculptors coming of age in California […] lacked any stable structure of galleries, patrons, and audiences’. |

|

Waffle: |

‘In the work of unconventional couple Robert Duncan and Jess…’ |

|

Q |

Who are Robert Duncan and Jess? When were they active? Why have they been chosen here? |

|

A |

Substantiated text: ‘poet Robert Duncan (1919–88) and the artist Jess (b. 1923) provided a focus for this interaction [between art and poetry]’ from the early 1950s.’ |

Organize your text in sensible order, working from the general to the specific, introducing an idea (‘painters and sculptors coming of age in California [experienced] marginalization’) and then supporting it with evidence (a published article; an artwork; historical proof). Pick your text clean of overblown or self-evident sentences.

Rambling text is mostly skimmed off the top of the writer’s head; the simple cure is to read more, look more, collect more information—and think more.

The following example examines a text by one of contemporary art’s most influential—if divisive—critic/historians, Rosalind Krauss. Her text is about Cindy Sherman: a great artist, but sadly the target of choice for much hackneyed undergraduate ‘analysis’, all ‘male gaze’ and ‘masquerade’.

Rosalind Krauss’s contribution to art history and theory since the 1970s is formidable (see ‘Beginning a contemporary art library’). From my own informal survey, no one divides opinion more starkly: to many she represents the very pinnacle of quality art-writing; for others Krauss occupies its most turgid, least enjoyable ebb. I will not be joining the Krauss denigrators; there is much to learn from her. Rosalind Krauss must really love art, given the lengths of time she dedicates to looking and thinking about it, omitting no detail, thinking through every shred of visual evidence—and yes, demanding that her readers really sweat to keep up. You don’t need to mimic Krauss’s dense language to appreciate her close, attentive art-viewing.

Here, in a monograph essay, Krauss offers a rebuttal to the ‘male gaze’ platitude that consumes much Sherman literature, by contrasting the details found in two photographs from the Untitled Film Stills series.

Sherman, of course, has a whole repertory of women being watched and of the camera’s concomitant construction of the watcher for whom it is proxy. From the very outset of her project, in Untitled Film Still #2 (1977), she sets up the sign of the unseen intruder [1]. A young girl draped in a towel stands before her bathroom mirror, touching her shoulder and following her own gesture in its reflected image [4]. A doorjamb to the left of the frame places the ‘viewer’ outside this room. But what is far more significant is that the viewer is constructed as a hidden watcher by means of the signifier that rewards as graininess [5], a diffusion of the image […]

But in Untitled Film Still #81 (1979) there is a remarkably sharp depth of field [6], so that such /distance/ is gone, despite the fact that doorways are once again an obtrusive part of the image, implying that the viewer is gazing at the woman from outside the space she physically occupies. As in the other cases, the woman appears to be in a bathroom and once again she is scantily dressed, wearing only a thin nightgown. Yet the continuity established by the focal length of the lens creates an unimpeachable sense that her look at herself in the mirror reaches past her reflection to include the viewer as well [2]. Which is to say that as opposed to the idea of /distance/, there is here signified /connection/, and what is further cut out as the signified at the level of narrative is a woman chatting to someone (perhaps another woman) [3] in the room outside her bathroom as she is preparing for bed.

Source Text 4 ROSALIND KRAUSS, ‘Cindy Sherman: Untitled’, in Cindy Sherman 1975–1993, 1993

OK, so I too am stupefied by what ‘/distance/’ accomplishes as opposed to plain-vanilla ‘distance’. Nonetheless, Krauss examines the visual evidence closely to suggest how these two Sherman photographs function differently: one seems to imply voyeurism, the other collusion. In the first, Untitled Film Still (#2) (fig. 7), the woman is spied upon unknowingly, perhaps threateningly [1]; in Untitled Film Still (#81) (fig. 8), the woman is aware of her onlooker and casually engaging with her/him [2]. Krauss notices that in both photographs, the door partially frames the woman, hinting at a viewer outside the bathroom. She pinpoints the two kinds of implied gaze: that of an ‘unseen intruder’; and that of a friend, someone of whom the pictured woman is perfectly aware, ‘perhaps another woman’ [3].

Krauss identifies the elements in Untitled Film Still (#2) that indicate the woman might be spied upon:

+ the blonde is fully absorbed by her own movement, seemingly oblivious to anything beyond [4];

+ the hazy quality of the photograph—suggests a voyeuristic viewer, someone perhaps taking these pictures on the sly, maybe (I will add) with a high-zoom lens [5].

She describes the contrast with the woman in Untitled Film Still (#81):

+ the brunette is looking past her own reflection in the mirror; possibly chatting with the viewer [2, 3];

+ the image quality [6] reflects that no one is straining to take this picture from a distance.

figs 7 and 8 CINDY SHERMAN, Untitled Film Still, (#2) 1977, (#81) 1980

From these details in the picture and the photographic styles, Krauss is constructing a larger point: why must we assume that any image of a lone woman invariably positions her as ‘objectified’? If we look carefully, we see that not all Sherman’s women are at a disadvantage with respect to the ‘viewer’ holding the camera—a man, a woman, possibly just a tripod.

Both Crow and Krauss show how they arrived at their conclusions, whether derived from historical events (key life episodes, such as Robert Duncan’s censored article in Crow’s text) or visual evidence (homoerotic subject matter in Jess’s collage, for Crow; contrasts in the print quality and composition observed in a pair of Sherman’s photographs for Krauss). To be sure, another art-writer may re-visit these very works and reach opposing conclusions, or prefer to hone in on other salient details from the artwork or historical data to validate a different interpretation. These two excerpts are not lauded as the final word on those artworks, but as examples of well-argued art-writing, as practiced by two noted American academics.

Rosalind Krauss’s text also illustrates how, as with Cindy Sherman, not all an artist’s works function exactly the same way. Bear this in mind the next time you hear talk about ‘a Gursky photograph’, indifferent to whether the large-scale Andreas Gursky C-print shows a Midwestern cattleyard or the Tokyo stock exchange; or ‘a Peyton portrait’ as if it makes no difference whether painter Elizabeth Peyton pictures Georgia O’Keeffe or Keith Richards. With rare exception, all artworks by one artist are not perfectly interchangeable. It may be acceptable art-fair shop-talk to speak of ‘the fantasy atmosphere of a Lisa Yuskavage painting’ or ‘the surreal quality of a Do Ho Suh installation’ but beware of bulking together a lifetime of work into a convenient soundbite. A good art-writer pays singular attention to each work, noticing what each does similarly and how they differ.

Keep your eye fresh; look at artworks one by one. Specify exactly which animated film by William Kentridge or which Subodh Gupta metallic sculpture you mean. If you pen an entire exhibition review without once plucking out a precise artwork, complete with title and date, and have mentally compacted the show into a homogeneous megalith, go back and look at each in turn. If you choose to group some artworks together, do so knowingly.

Here’s a little exercise that might help you to pay close attention. Consider the following fast-action online comments by critic Jerry Saltz, who zeroes in on a few favorites seen on a whirlwind tour of three art fairs, back to back.

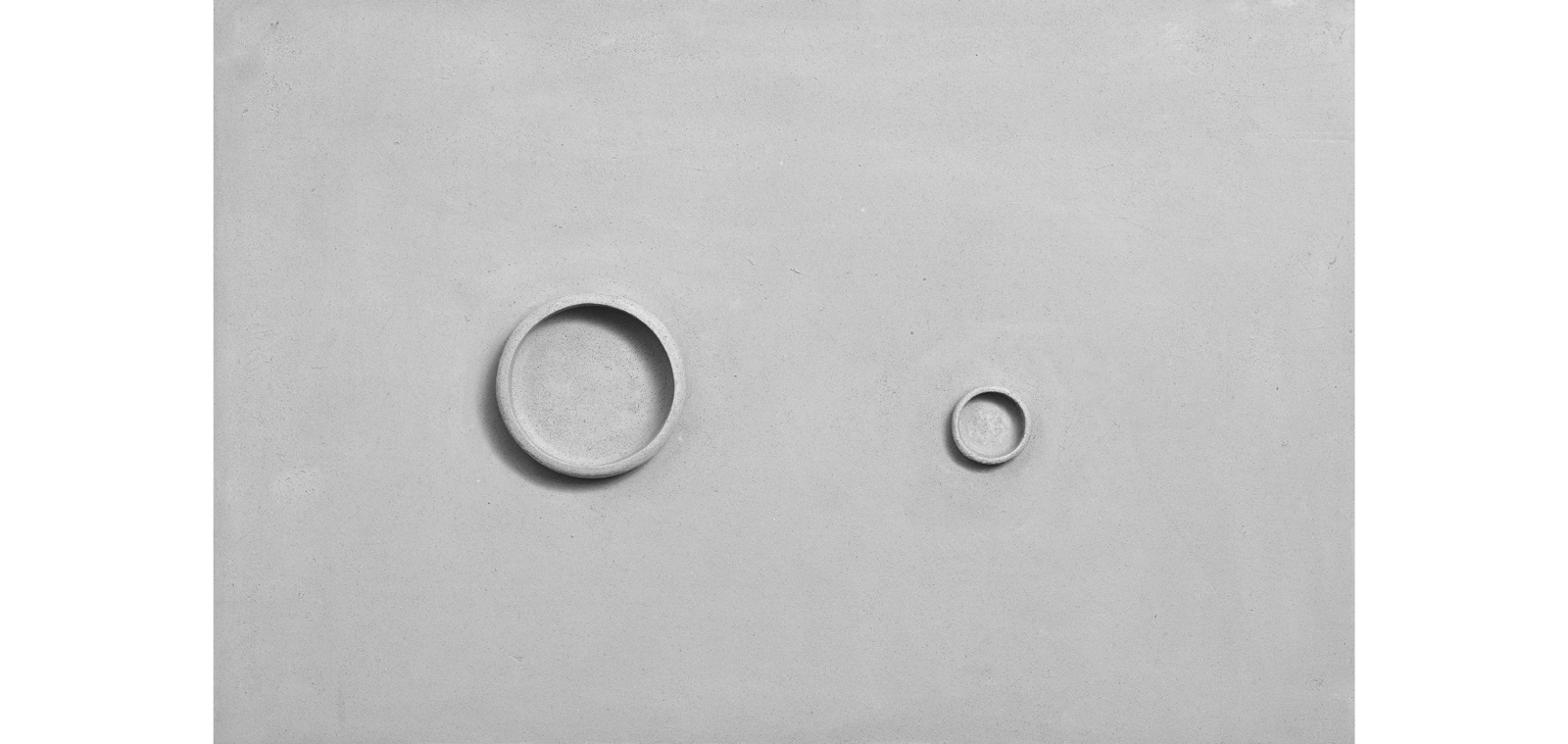

Anna-Bella Papp, For David, 2012

One of an array of sixteen little clay landscapes or paintings or metaphysical maps, all laid flat. Each reads as a world, design, or tile. Wonderful Morandi-like internal space. Want. [fig. 9]

Martin Wong, It’s Not What You Think? What Is It Then?, 1984

This artist, who died young in 1999, is way overlooked. And much better than people realize. The intricate brickwork makes the painting look like a labor of love, a piece of flat sculpture, and a wall from the artist’s memory. [fig. 10]

Source Text 5 JERRY SALTZ, ‘20 Things I Really Liked at the Art Fairs’, New York Magazine, 2013

|

|

fig. 9 ANNA-BELLA PAPP, For David, 2012 |

fig. 10 MARTIN WONG, It’s Not What You Think? What Is It Then?, 1984 |

Although such Tweet-like commentary should not pass for fully fledged art-criticism, and is symptomatic of the volume of artworks that dedicated writers must rapidly process, attempting this concentrated format can help you to focus your art-viewing attention and find ways to express your intuitive art-thinking.

+ What is it that turns you on? Be specific; be honest. Use your own words.

+ Write your thoughts down precisely in 40 words or fewer. Paste a picture at the top of your file: do your words add richness to its viewing, or contradict the picture, or make zero connection?

+ Test your demi-text out on a friend. Do your words make sense to her?

This drill can help you write succinctly, and directly from looking—not from artspeak habit.

Try this little work-out when you next see an artwork that instinctively appeals. Put into a few words—just a two-or three-line bonsai version of the what is it?/what does it mean?/so what? triumvirate—exactly why you like it.

In Okwui Enwezor’s catalogue essay on Craigie Horsfield, the art-writer shows the reader just what he is looking at in Horsfield’s photos that led to his stunning interpretation: these men and women appear as ‘the condemned’ (see Source Text 2 and fig. 5). Here’s a decades-old example (published in a Modern Painters magazine article) from legendary critic and historian the late David Sylvester, in which substantiation is not based on factual evidence but follows the logic of the writer’s thoughts.

The time when Picasso was making his first junk sculptures [1] was also the time when Duchamp made his first sculpture from readymade materials. It was a bicycle wheel placed upside down on a stool [1]. Now, the two objects assembled here are the most basic objects in man’s winning dominion over the earth and in distinguishing himself from the beasts of the field [2]: the stool, which enables him to sit down off the ground at a height and a location of his choice; the wheel, which enables him to move himself and his objects around. The stool and the wheel are the origins of civilization, and Duchamp rendered them both useless. Picasso took junk and turned it into useful objects such as musical instruments; Duchamp took a useful stool and a useful wheel and made them useless [3].

Source Text 6 DAVID SYLVESTER, ‘Picasso and Duchamp’, 1978/92

Sylvester makes some pretty hefty claims: Picasso’s junk sculpture and Duchamp’s readymade express what distinguishes a human being from all other earthly life, and do so in opposing ways. That is quite a thought, but Sylvester succeeds by taking his reader step-by-step through his thinking. He doesn’t leap from ‘Picasso was making his first junk sculptures […] Duchamp made his first sculpture from readymade materials’ to his momentous conclusion: together they represent two antithetical approaches to some big subjects, such as art, usefulness, even humankind’s relationship to the animal world. The writer unravels his thoughts one-by-one, accompanying us on a journey, answering the three questions of communicative art-writing:

Q1 What is it? [1]

Q2 What might this mean? [2]

Q3 So what? [3]

Sylvester draws a dramatic concluding distinction between these two seminal 20th-century artists. No fancy words, no jargon, just attentive reflection on what he is looking at, and the original ideas this prompted in him.

> Faulty cause and effect

In unsubstantiated, bad art-writing, the ‘meaning’ of artworks is blithely asserted without tracing its source. Consider the following example, published on (but since removed from) a museum website that should responsibly speak to a general visitor, accompanying a series of photographs showing artist Haegue Yang’s ‘assisted readymade’ sculptures of an ordinary air-drying clothes-stand, folded this way and that.

A newly commissioned piece…embraced [the artist’s] interest in emotional and sensorial translation. It required her to trespass upon nationalism, patriarchal society as well as recognized human conditions, elaborated with an artistic strategy of abstraction and affect.59

The rest of this text was no help. This writer would have benefited from a careful editor raising a few questions, unpicking the faulty cause-and-effects, and shaking some sense out of this blurb:

+ what is meant by ‘emotional and sensorial translation’ or ‘an artistic strategy of abstraction and affect’?

+ how exactly does the artist ‘trespass upon nationalism [and] patriarchal society’?

+ how are these two things—air-drying one’s laundry, and patriarchy—joined together?

+ how does laundry represent the human condition, again?

+ are people with electric clothes-dryers exempt from suffering ‘recognized human conditions’? (Which begs the question, are there unrecognized human conditions?)

Provide readers with all the steps in your thinking; this will help you disentangle ideas for yourself, too.

The quantum leap here—from laundry-drying device to a treatise on the human condition—is impossible to follow; yet such implausible gaps in logic abound in contemporary art-writing.

Have mercy on your reader. Even the most devoted cannot loop together so many missing links. And your hypothetical hyper-attentive reader, painstakingly piecing together the secret logic behind this unearthly chain of thought, could never be certain the presumed correlations between air-drying and ‘an artistic strategy of abstraction and affect’ matched those of the writer.

To paraphrase contemporary artist Tania Bruguera, ‘art’—if we dare attempt to define it—might be characterized by its basic instability.60 Or, as the artist and writer Jon Thompson puts it, for him producing an artwork is ‘a shot in the dark’.61 ‘Art’ occurs when an artist (or group) brings together a set of materials (or circumstances) and the results—somehow—add up to something greater than its constituent element(s), whether:

+ pigment on a canvas;

+ a shaped block of clay;

+ a set of light-boxes turned to the wall;

+ a group event in a retail shop;

+ a web-based newsfeed projected on a screen;

+ a photograph of a curled sheet of paper;

+ an artist walking the perimeter of his studio;

+ a giant crack down the Tate Modern Turbine Hall floor;

+ a bottle-rack on a plinth, ad infinitum.

Good art-writing tries to put into words what somehow happened—what was inexplicably extra—when the artist(s) brought together those exact

+ materials,

+ or objects,

+ or technologies,

+ or people,

+ or pictures,

+ ad infinitum.

Here’s the bad news: stabilizing art through language risks killing what makes art worth writing about in the first place. For this reason, art-writing by definition is a somewhat conflicted and flawed pursuit. Good art-writers accept the paradox of the job, tackling this conundrum head on. Bad art-writing, instead, is unaware of its own precariousness and takes art as a given, a predetermined fixity that requires the embellishment of words to gain significance, which it is not. Often, a good art-writer traces which decisions made by an artist (or artists) seem to have proven most meaningful in the resulting artwork. These decisions can be deliberate, accidental, collaborative, minor, forced, unwanted, ongoing, declared, or otherwise. A good art-writer might hazard an empathetic guess, by looking and thinking hard, as to which decision turned out crucial to the whole thing:

+ the material they decided to use;

+ how the shot was framed;

+ the technology they decided to try;

+ the image that inspired them;

+ the site they decided to discover;

+ or the people the decided to work with.

Just as art-commerce sets out to fix art’s basic instability by quantifying value in terms of hard currency—a process played out in the auction room, where art’s price floats airborne from bidder to bidder, eventually settling down with the bang of the hammer—art-writing is a similarly paradoxical business: fixing unstable art through language.

Although some art-texts may attempt to mimic art’s very precariousness, for example in the form of a poem or fiction, much everyday art-writing attempts to steady art through language. For this reason, understanding different audiences or readerships means in part gauging how much art-stabilization they require. The less art-experienced your reader, the more grounding they will need. Some readers want to absorb only quantifiable information (statistics; prices; records; dates; audience numbers); feed them these.

When writing for children, for example, quantify with precision: Jeff Koons’s Puppy (1992) contains 70,000 flowering plants and required 50 people to build.62 Define every term: ‘Pop art’, ‘abstract’, ‘portraiture’. Specify exactly what you are asking young readers to look for—how is Puppy different from other massive outdoor sculptures, such as the Statue of Liberty in New York?—but respect their ability to think for themselves.

For a general audience, pack your text with physical description, historical knowledge, and/or concise artist’s statements—anything to help anchor the viewing experience in hard information. This is not a license to be patronizing, or to insist that all viewers respond to the artwork identically. Do not pretend to know or dictate what someone else thinks about art by spelling out how ‘bewildering’ and ‘thought-provoking’ this artwork is. Readers are perfectly entitled to find the work tedious and juvenile. Conversely, your audience may be even more turned on by this art than you are, and attribute the work with crazy magical powers you could not foresee. The toughest skill lies in rendering these general-audience texts also readable for the expert; this can be achieved through careful, up-to-date research and a straightforward, intelligent writing style. Read all you can, perhaps honing in on moments in the artist’s decision-making that proved salient, and start there. A specialized art-text, such as

+ an article in an art magazine,

+ an academic assignment,

+ a museum catalogue essay,

+ or an exhibition review,

can venture into somewhat less stable territory, but this does not condone speaking in tongues. Prepared readers can appreciate genuinely adventurous art-writing which attempts to slip toward the unstable plane of art itself: not artspeak babble, but writing that attempts to match art’s own dare. Walter Benjamin’s startling ‘angel of history’ paragraph (see Source Text 1) literally knocks Klee’s wide-eyed figure off-balance, rocking the little angel with a tide of rubble, tripping him up as he attempts to stride into the future. This is breathtaking stuff, but such ambitious art-writing entails tremendous skill. Your job usually is to steady and communicate art’s basic instability using a few well-chosen ideas expressed in unclichéd and thoughtful words. If you are new at this, stick to that tough-enough job.

The following practical directives are more specific than the general guidelines presented until now. One day you might discard every handy suggestion listed here, and your writing will soar with poetry as a result. In the meantime, it is helpful to become aware of some common art-writing pitfalls, and try these small improvement techniques for yourself.

If you absorb only one recommendation in this book, let it be this: don’t dance around art by writing in broad strokes and generic art-patois. Precise, knowledgeable, unexpected use of language in response to a single, well-chosen artwork instantly elevates your writing out of the doldrums. Vague words, swirling aimlessly around an artwork, die on the page:

Combined in Haroon Mirza’s art (fig. 11) are multiple technologies. Which resulted in a kind of light show accompanied by a sort of ‘music’ which the viewer was not expecting.

As with much beginner art-writing, this passage of hypothetical unedited text raises more questions than it answers. Which technologies? Where did the light come from? What ‘sort of “music”,’ and why was this ‘unexpected’? Which artwork is the writer talking about? That second phrase is not actually a sentence. Sadly, the verdict here is to rewrite from scratch, bearing the following helpful improvements in mind:

+ be specific: add titles and dates; substantiate and visualize points;

+ combine two fragments into a single coherent sentence;

+ drop messy adverbs and adverbial phrases (‘kind of’; ‘sort of’);

+ avoid the passive and rewrite in the active tense;

+ do not presume what ‘the viewer was […] expecting’.

fig. 11 HAROON MIRZA, Preoccupied Waveforms, 2012

In Preoccupied Waveforms, 2012 (fig. 11) Haroon Mirza brought together a variety of noisy, light-emitting technologies—from flashing junk-shop television sets, to strips of colorful LED lights—and arranged their humming or buzzing white noises to create a syncopated, rhythmic music.

Solid nouns (‘junk-shop television sets’, ‘lights’, ‘white noises’) and precise verbs (here used as descriptors: ‘humming’, ‘buzzing’) set the scene. Avail yourself of visually rich language to help your reader imagine what happened in the gallery. Without that firm basis, the reader is unequipped for what might follow—like your concluding brilliant discussion about Mirza’s son et lumière. Ground your reader accurately in the experience, so that she may gain the confidence to look further for herself.

> Flesh out descriptions

Don’t limit your preamble to, for example, ‘Brazilian sculptor Ernesto Neto produces room-sized multi-media installations’. Could you give us a hint? Color? Materials? Title? Put some meat on those bare-bone descriptions! Tell us about Neto’s Camelocama (2010; fig. 12), a tree-like structure, which

fig. 12 ERNESTO NETO, Camelocama, 2010

+ erupts out of the center of an outdoor courtyard;

+ is made from multicolored crocheted rope;

+ has ‘branches’ formed from a circular canopy suspended on braided yellow ropes, and a ‘stem’ rooted in a round mattress-like net filled with colorful PVC balls;

+ invites visitors to lie back and stare at the fourteen protuberances above, heavy with orange plastic balls, drooping downwards and looking, well, like glowing alien testicles.

You might talk about the contrast with the classical architecture behind it, or how the sea of multicolored balls recalls the toddler’s playroom at IKEA. After your vibrant description, think about what all those goodies might mean. But first, ensure that your readers have grasped the art at hand.

> Keep pictures of the art right in front of you

While penning your description from home, look at the photo from:

+ top to bottom

+ right to left; left to right

+ corner to corner.

This exercise is especially important when looking at two-dimensional works, like paintings or photographs. Do not shrug off the ‘edges’ or ‘empty’ parts, but take the entire artwork into account. Working out the ‘gaps’ in the picture or the film—where ‘nothing is happening’—can sometimes be a good place to start, by asking yourself: why might the artist have included these mysterious ‘blanks’?

> Do not ‘explain’ a dense, abstract idea with another dense, abstract idea

This tops the list in art-writing malpractice: piling abstract nouns one on top of the other, turning texts into a blur of imprecise, woolly concepts. Perhaps you too have been confronted by stupefying sentences like the example below, which was published in a group-exhibition catalogue:

[Ours] is a response to an exigent disparity in critical discourse evident in the putative designation of form as subaltern to content and the posturing of the referent and iconological as the cardinal gateway for all understanding when it comes to contemporary art from the Middle East. 63

This might as well be written in Chamicuro, an endangered language spoken fluently by a total of eight earthlings. In 46 words, our minds must process at least nine abstract ideas:

+ ‘exigent disparity’

+ ‘critical discourse’

+ ‘putative designation of form’

+ ‘form as subaltern to content’

+ ‘posturing’

+ ‘referent’

+ ‘iconological’

+ ‘cardinal gateway’

+ ‘all understanding’.

That’s roughly one undeveloped concept every five words. Who can possibly keep up? What is this writer looking at? How do these words say anything about their art experience?

> Keep your abstract word count low

Employ abstract nouns only once your reader has been firmly grounded in the work’s basic description and meaning. A relentless onslaught of abstract ideas is torture; check out the lucky winners of the now-defunct ‘Philosophy and Literature Bad Writing Contest’.64 Top prizes were always reserved for those who stockpile abstractions, one after another, in a single heaving sentence. Here’s another example, from a gallery press release:

Always seeking to expand notions of what an image can be, Lassry [fig. 13] produces pictures that escape their indexical relationships by highlighting their formal properties and by opening the way for questions regarding their connection to specific cultural contexts. The pictures become sites where an image becomes a mere object, and thus places where Lassry questions the fundamental conditions of seeing.

In the current exhibition, wall-based sculptural objects that resemble cabinets call to mind several properties (size ratios, seriality, and modularity) characteristic of Lassry’s pictures. However, the apparent utility of the cabinets as vessels allows them to be read as paradoxes, photographs that have been fleshed out as objects but evacuated as representations.65

More Chamicuro. The first sentence alone is a concoction of six abstractions:

+ ‘notions of what an image can be’

+ ‘indexical relationships’

+ ‘formal properties’

+ ‘questions’

+ ‘connection’

+ ‘cultural contexts’

fig. 13 ELAD LASSRY, Untitled (Red Cabinet), 2011

Such sentences are adrift in space, unanchored by any weighty nouns to tether them to earth. When finally rewarded with a concrete noun, ‘cabinets’, we are promptly told these are not cabinets, but ‘paradoxes’, ‘evacuated as representations’, and remain stranded in abstract-noun-land. The mind boggles, and Elad Lassry—with his irresistible pictures of ordinary objects such as cabinets, cats, baguettes, and wigs, artfully photographed as if they were masterworks of sculpture—deserves better.

This book will place great emphasis on solid, precise wording. Finding the right, concrete term isn’t preferable just because it sounds nice. Employing the exact, carefully chosen word is the mark of an art-writer really attempting to understand art through language, and to communicate their findings to a reader.

> Load your text with solid nouns

Solid nouns are able to produce full mental pictures; for example in Okwui Enwezor’s text about the photographs of Craigie Horsfield, ‘industrial city’, ‘street corner’, ‘factory floor’ (see Source Text 2 and fig. 5). Remember Goya’s ‘baker’s family’? (Francisco Goya’s The Family of Carlos IV, c. 1800, fig. 4, described by writers including Lucien Solvay, see section 2.1.) With apologies to that excellent profession (and for the phrase’s deplorable 19th-century class-ridden assumptions), a concrete noun like ‘baker’ condenses a slew of adjectives for the ordinary, garish, undeserving, unfit, uninspiring, vulgar, overfed family on view. See? Save words: use concrete nouns.

‘[O]ne of my favorite definitions of the difference between architecture and sculpture is whether there is plumbing.’

In that definition, the 1970s sculptor/architect Gordon Matta-Clark—who cut giant curves through the walls of abandoned buildings—interjected the word ‘plumbing’: just the sort of well-chosen, definite noun that brings art-writing alive. Matta-Clark’s curious word-choice may seem kooky and random, but actually ‘plumbing’ communicates his workman-like attitude toward art, and the way he sliced through the walls of functioning buildings, to peer at the pipes and other innards.

> Use picture-making words when describing art

Unless discussing a certain shark floating in a tank, or that porcelain bathroom fixture signed ‘R. Mutt’, never assume your reader remembers or has seen the art. Even texts accompanied by a photograph—even if placed adjacent to the actual artwork—should usually begin with something the reader can see or quickly understand. This goes double if you’re among the first to write about an as-yet undiscovered artist, introducing readers to little-known art. Get to the point; what exactly is special about this work? Tax your mind and be specific. If your commentary would be more or less applicable to any artwork gracing the cover of Flash Art since 2003, you must think harder. Become sensitive to your abstract-noun count. Use abstractions sparingly, and insert meaty nouns instead.

Here’s the late Stuart Morgan, describing a painting by Fiona Rae (concrete, picture-making nouns in bold):

In Fiona Rae’s Untitled (purple and yellow I) [1991], an airborne coffin, an atomic cloud, a plane crash, two ink-blots, a beached whale and a tree with a breaking branch meet and mingle. That is one way of describing it. It does not account for the ownerless breasts, the Hebrew letter, the cock’s comb and badly frayed item of male underwear on a flying visit from some parallel universe.

Source Text 7 STUART MORGAN, ‘Playing for Time’, in Fiona Rae, 1991

Morgan packs his description with feisty nouns (‘coffin’, ‘cloud’, ‘whale’, ‘tree’), which economically help us visualize the details in Rae’s exuberant painting and, moreover, drive home the breadth of this artist’s imagination.

One plum adjective can brighten a whole paragraph. The best advice with adjectives is pick one, and make it a good one. Can you program your laptop to sound an alarm when you type anemic adjectives?

+ ‘challenging’

+ ‘insightful’

+ ‘exciting’

+ ‘contextual’

+ ‘interesting’

+ ‘important’

These one-size-fits-all adjectives can be loosely applied to any artwork since Tutankhamen. You might collect (in a special file on your laptop) any prize adjectives—‘bullet-proof’; ‘sunny’; ‘moist’—that you come across when reading. Dip into your collection whenever you’re tempted to resort lazily to the flatliners listed at the top. (Note: A similar collection of jazzy verbs makes the perfect gift for a writer.) Remember: usually your first job is to stabilize the art for the reader. Choose words that ignite precise mental imagery. Even the most ravishing interpretation will flounder if the reader cannot first powerfully picture what you’re talking about.

Less is more when it comes to adjectives. Undergraduates will often list three adjectives: ‘The art was challenging, insightful, and unforgettable.’ Post-grads whittle this down to two: ‘The art was challenging and insightful.’ Many pro’s will pinpoint the perfect adjective—avoiding these tiresome descriptors altogether and preferring materially evocative ones:

Concrete (picture-making) adjectives

+ ‘overgrown’

+ ‘glowing’

+ ‘slim’

Abstract adjectives

+ ‘formal’

+ ‘indexical’

+ ‘cultural’

Here is an evocative extract filled with concrete adjectives, from a magazine article by art-critic Dale McFarland (most adjectives in bold):

In [Wolfgang Tillmans’s] studies of drapery [fig. 14]—the folded and crumpled fabrics of clothes discarded on a bedroom floor, jeans, T-shirts, details of buttons, pockets and gussets—this classical formalism is highlighted through the most unexpected subject matter. The photographs capture a second of visual pleasure in the colors and textures of a pile of dirty laundry: the play of light and shade on blue satin running shorts, white cotton flecked with some unsavory stains. They have more than a hint of eroticism, clearly evoking the act of undressing, and appear to retain the warmth and scent of the wearer. They feel airless, maybe even claustrophobic—like being tangled in sticky bedclothes on a hot summer night in a windowless room. This beauty of mess and ephemerality is in part what Tillmans describes: he has a heartbreaking fondness for the moment that will inevitably vanish, and fanatically attempts to record just how lovely, how special and how unrepeatable it is.

Source Text 8 DALE MCFARLAND, ‘Beautiful Things: on Wolfgang Tillmans’, frieze, 1999

One precise adjective (‘dirty’; ‘windowless’; ‘heartbreaking’) has more descriptive power than a torrent of indecisive ones. McFarland’s doubled descriptors do not contradict each other: ‘folded and crumpled’ does not indulge in a meaningless ‘yeti’ (my term for the self-contradicting paired adjectives that fill the pages of inexperienced writers, i.e., ‘crumpled yet smooth’, see section 2.1). McFarland’s is a rather poetic example, but his airy writing is anchored not only by the precision of his adjectives, but by his constant return to concrete nouns, drawn from the artworks: ‘a pile of dirty laundry’, ‘blue satin running shorts’. McFarland also conjurs non-visual sensations which complement the mood of domestic intimacy:

+ smell: ‘the…scent of the wearer’;

+ touch: ‘sticky bedclothes’;

+ action: ‘undressing’.

Tillmans’s luscious photographs are a bit like soft-porn poetry; McFarland’s atmospheric words suit the art. This text seems to fulfil Peter Schjeldahl’s recommendation to the art-writer—‘furnish something more and better than we can expect from life without it’—in this case, creating a pitch-perfect written accompaniment to Tillmans’s quietly sensual photos.67

fig. 14 WOLFGANG TILLMANS, grey jeans over stair post, 1991

> Gorge on the wildest variety of strong, active verbs

Dynamite verbs charge your writing with energy. The quickest way to enliven a sluggish text is to comb for blah verbs (‘be’, ‘have’, ‘can’, ‘need’, ‘are’) and replace them with vigorous ones (‘collapse’; ‘whitewash’; ‘smuggle’; ‘corner’). Lace your text with unexpected actions.

Here’s an example from artist and writer Hito Steyerl, in her influential e-flux journal essay about the precarious state of digital imagery (most verbs in bold) (see fig. 15, Hito Steyerl, Abstract, 2012):

The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self. It mocks the promises of digital technology. Not only is it often degraded to the point of being just a hurried blur, one even doubts whether it could be called an image at all. Only digital technology could produce such a dilapidated image in the first place.

Poor images are the contemporary Wretched of the Screen, the debris of audiovisual production, the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores. They […] are dragged around the globe as commodities or their effigies, as gifts or as bounty. They spread pleasure or death threats, conspiracy theories or bootlegs, resistance or stultification. Poor images show the rare, the obvious, and the unbelievable—that is, if we can still manage to decipher it.

Source Text 9 HITO STEYERL, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, e-flux journal, 2009

Look closely at the choice verbs that Steyerl injects into this short passage:

+ ‘misspelled’

+ ‘degraded’

+ ‘defies’

+ ‘mocks’

+ ‘washes up’

+ ‘decipher’.

Notice also how many delicious nouns she employs to convey the variety of degraded images (‘bastard’, ‘decoy’, ‘bootlegs’). There is a judicious sprinkling of adjectives (‘dilapidated’, ‘vicious’) but notice the dearth of adverbs, which would garble Steyerl’s powerful writing.

This is not an invitation to abuse your thesaurus and compose purple prose, but to broaden your thinking by expanding your vocabulary. Steyerl’s varied nouns and verbs drive home her bigger point: digital imagery is compromised in myriad new ways—a degradation that she expands upon in the rest of her text. In this early paragraph, Steyerl sets the scene, detailing how she is defining ‘poor images’ and showing how they behave before interpreting what this might imply for 21st-century art.

fig. 15 HITO STEYERL, Abstract, 2012

Another artspeak tic is the dreaded DVS: Duplicate Verb Syndrome, as we’ll call it, which—like its monstrous cousin, the adjectival ‘yeti’ (see section 2.1)—unnecessarily shoves two terms together where one would suffice. For example, ‘This paper will critique and unpack the post-colonial legacies of Yinka Shonibare.’ Similarly we read, ‘This research/exhibition/artwork will’—

‘challenge and disrupt’

‘examine and question’

‘explore and analyze’

‘investigate and re-think’

‘excavate and expose’

‘displace and disrupt’

Usually the paired verbs accomplish virtually the same action, and are coupled just to complicate a nothing sentence. If you double up your verbs, make sure they’re doing two different things: ‘stand and deliver’, ‘cut and paste’, ‘rock and roll’, ‘shake and bake’. Otherwise, shave off that redundant verb.

> ‘The road to hell is paved with adverbs.’

This is more wisdom from Stephen King.68 Adverbs slow and dull your writing; scratch them out mercilessly. Adverbs are like weeds sprouting through the tidy lawn of your text. Few adverbs appear in the examples above (Source Texts 7, 8, and 9): Morgan’s text has two, ‘badly’ and ‘some’. McFarland includes ‘clearly’ and ‘inevitably’; Steyerl ‘deliberately’. Some modifiers are essential (‘more than’; ‘often’) but expert writers keep their adverb-count low. 69

> Avoid clutter

This means waging war on adverbs and excess adjectives, as well as the dreaded jargon. Here’s John Kelsey’s sparse, direct style, filled with image-making nouns (in bold):

[Fischli and Weiss’s] Women come in three sizes: small, medium and large (one meter tall). They come individually and in sets of four (cast in formation, along with the square of floor that supports them). The Cars are roughly one-third the actual size of a car. These off-scales give them the ‘look’ of art: Greek or Neoclassical statuettes or Minimalist blocks presented on plinths, they occupy the place of art in a casual way, simply parked or posing here. They might be aesthetic stand-ins or sculptural surrogates [1]. Even in heels, the Women manage to mimic the relaxed beauty of classical contrapposto poses, one leg supporting the body’s weight, the other slightly bent […]

They are stewardesses and cars in the form of décor and vice versa. Returning us to the safety and comfort of a world whose values are always in order, they also haunt this place with their ordinariness and ease. They remind us that this space of inventory is always already filled, like a parking lot.

Source Text 10 JOHN KELSEY, ‘Cars. Women’, in Peter Fischli & David Weiss: Flowers & Questions: A Retrospective, 2006

Kelsey’s simple and familiar words create mental pictures that match Fischli and Weiss’s brilliantly deadpan art, and form the groundwork before he ventures into his brainy observation: Cars remind us how a gallery, in practice, functions ‘like a parking lot’ for art. This writer’s abstract ideas are mostly condensed into one line [1]; by then, we are firmly versed in the art’s material description, and not thrown by Kelsey’s interpretation. Abstract nouns and abstract adjectives, like adverbs, are the dross that clog up art-writing like so much sawdust. Adopt non-picture-forming terms (‘stand-ins’, ‘surrogates’) only when you’ve ensured that your reader knows what you are looking at.

Unless you’re deliberately going for drama, logical order should be preserved at every level—a single sentence, a paragraph, a section, your whole text.

+ Keep to chronological order;

+ move from the general to the specific, often introducing an overall idea, then filling in with detail and examples;

+ prioritize information: key info goes at the end, or front—don’t bury it in the middle;

+ keep linked words, phrases, or ideas together.

> A logically ordered sentence

Here is a line by the legendary art historian Leo Steinberg, from a lecture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and later published in Artforum:

In the year following White Painting with Numbers (1949), Rauschenberg began to experiment [1] with objects placed on blueprint paper and exposed to sunlight.

Source Text 11 LEO STEINBERG, ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane’, 1968

This sentence, which discusses what we recognize as artist Robert Rauschenberg’s blueprint photograms, starts by sensibly locating the basics: when (‘in the year…1949’) and who (Rauschenberg). Steinberg proceeds logically by first announcing that Robert Rauschenberg was beginning to experiment in his art, then explaining the nature of the experiment: placing objects on blueprint paper and exposing this to sunlight. Logic moves chronologically, and from the general to the specific. To aid clarity, keep the subject right near its verb, as in ‘Rauschenberg [subject] began to experiment [predicate]’ [1]. (For general-audience or journalistic texts, keeping subject and predicate tightly together is practically mandatory.)

In the versions below, Steinberg’s sensible order has been poorly rearranged; as a result the sentence turns confusing. In the second example below, not only is the reader forced backwards in time, but the objects are now running the experiment, not the artist!

Blueprint paper exposed to sunlight, with objects placed upon it, in the year following White Painting with Numbers (1949), is how Rauschenberg began to experiment.

Rauschenberg’s objects, placed on blueprint paper and exposed to sunlight, began an experiment in the year following his White Painting with Numbers (1949).

The English language allows for substantial freedom in word-placement; learn logical sequence to help you determine optimal order. Carefully rearrange any tangled sentences. If your sentences are littered with commas like the two examples above, chances are your order is scrambled and needs tidying. Sentences whose convoluted construction requires ‘is how’, ‘is what’, or ‘is why’, like the middle version above, are usually begging for a rewrite.

> A logically ordered paragraph

In this Artforum article, the critic, filmmaker, and scholar Manthia Diawara examines the work of Seydou Keïta, a Malian studio photographer who, from the 1940s, created stunning black-and-white photos of the elegant bourgeoisie in Bamako, capital city of French Sudan (now Mali). In this close reading of a single portrait centering on a young man holding a flower, Diawara gets to grips with Keïta’s exquisite ability to capture the period’s cosmopolitan Bamakois. The author first draws our attention to the details observed in this image—the clothes, props, and gestures—and shows how these point toward the broader historical setting, to include education under French colonial rule and West African Modernism.

[Seydou Keïta’s] portraits have the uncanny sense of representing us and not-us. Take, for example, the man in white holding a flower in his left hand [fig. 16]. He is wearing glasses, a necktie, a wristwatch, and, in the embroidered handkerchief pocket of his jacket, a pen [1]—tokens of his urbanity and masculinity. He looks like a perfect Bamakois [2]. However, the way he holds the flower in front of his face constitutes a punctum in the portrait, a moment in which we recognize the not-us. The flower accentuates his femininity, drawing attention to his angelic face and long thin fingers. It also calls to mind the nineteenth-century Romantic poetry of […] Stéphane Mallarmé, which was taught at the time in the schools of Bamako [3]. In fact, the man with the flower reminds me of certain Bamako schoolteachers in the 1950s who memorized Mallarmé’s poetry, dressed in his dandied style, and even took themselves for him.

Source Text 12 MANTHIA DIAWARA, ‘Talk of the Town: Seydou Keïta’, Artforum, 1998

The limpid tone of Manthia Diawara’s text, coupled with the author’s evident appreciation for the modish details observed in this portrait, suits Keïta’s elegant photography. We can clearly distinguish between

[1] what’s in the picture;

[2] routine assumptions;

[3] and Diawara’s personal response.

The use of first-person (‘me’) is risky, but arguably in sync with the intimacy and directness of the portrait. With satisfying descriptions like this behind him, Diawara can proceed in the rest of his essay to tease apart two functions in this artist’s work: ‘a decorative one that accentuates the beauty of the Bamakoises, and a mythological one wrapped up with modernity in West Africa’. Diawara ensures he has established what the work is before exploring what it may mean, and why it may be worth thinking about.

To re-order these well-behaved sentences would diminish their clarity. To illustrate this point, let’s botch one of Diawara’s perfect sentences by re-writing it in an unruly, amateur style.

Scrambled version: ‘In fact, dressed in a dandy style, certain Bamako schoolteachers took themselves for Mallarmé, like the man with the flower, memorizing his poetry in the 1950s as I recall.’

Diawara: ‘In fact, the man with the flower reminds me of certain Bamako schoolteachers in the 1950s who memorized Mallarmé’s poetry, dressed in his dandied style, and even took themselves for him.’

In the top, bungled version, confusions arise.

+ Who was memorizing Mallarmé’s poetry, the man with the flower or the schoolteachers?

+ What exactly does the author recall: the man with the flower, the Bamako schoolteachers, the poetry they memorized, or that this occurred in the 1950s?

fig. 16 SEYDOU KEΪTA, Untitled, 1959

The badly structured version begins with details from the writer’s memories, then backtracks to their source. The subject/verb (‘I recall’) gets tagged at the end, when belatedly we discover that these associations have been drawn from personal recollection. Readers must waste their efforts untangling this jumbled sentence, and may misinterpret its meaning.

In your final edit, check that your sentences and paragraphs pursue logical order. Eventually you will develop an ear for it, but until then—and unless you want to shake things up—shift words or phrases around to ensure clarity:

+ follow chronological sequencing;

+ work from the general to the specific;

+ keep related terms or ideas close together.

> Organize your thoughts into complete paragraphs

Especially in academic or magazine writing, do not chop your text into fussy little note-like, two-line fragments. You are not composing a bullet-pointed email or Tweet (unless as an exercise, see Source Text 5) but an elegant piece of prose. Gather ideas into cogent paragraphs. Similarly, do not write in unbroken, page-long blobs. Break up indigestible text-blocks; write in bite-size paragraphs.

What is a paragraph? A paragraph addresses one principal idea, and is comprised of related, complete sentences—not bizarre half-sentences, vague run-ons, or non-sequiturs. Often, the first line introduces a key idea, and transitions smoothly from the preceding paragraph. Generally, a paragraph is composed of a minimum of three sentences, rarely more than ten or 12. Usually it does not end in a quote. The last line(s) develop(s) the first, rounds it all up nicely, and may hint at what’s arriving next.

In Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives (2009), writer and art-critic Brian Dillon presents nine real-life case studies—from Charlotte Brontë to Andy Warhol and Michael Jackson—of famous sufferers of hyponchondria: the pathological anxiety over one’s health. Here Dillon works in a sophisticated form of art-writing that straddles essay-writing, biography, research, and art-criticism. He lists the litany of health complaints that comprised Warhol’s childhood and which, as the writer surmises, might account for the artist’s lifelong obsession with death:

The origins of Warhol’s hypochondria [1], as of the prodigious value he put on physical beauty, are superficially easy to discern. In his 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), he claims to have had ‘three nervous breakdowns when I was a child, spaced a year apart. One when I was eight, one at nine, and one at ten. The attacks—St Vitus Dance—always started on the first day of summer vacation.’ [2] […] According to his brother Paul Warhola [3], Andy had already been sickly for some years before the crisis that seems to have changed him for good. At the age of two, his eyes swelled up and had to be bathed with boric acid. At four, he broke his arm […] He also had scarlet fever at six, and tonsils out at seven [4]. There is nothing singular about those episodes except the meanings he and his family attached to them in retrospect: they were part of the narrative of his physical and emotional enfeeblement.

Source Text 13 BRIAN DILLON, ‘Andy Warhol’s Magic Disease’, in Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives, 2009

This paragraph focuses on one point: Warhol’s childhood was marked by ill-health, and these repeated episodes fed his self-image as physically frail and emotionally needy. The first sentence spells out exactly what the paragraph sets out to do: explain its origins [1]. We are immediately told how this background relates to Warhol’s art-making, with its obsession over physical beauty. Dillon provides plenty of examples to substantiate his argument about Warhol’s unhealthy childhood:

[2] quotes from the artist’s book;

[3] first-hand observations from the artist’s brother;

[4] verified events in Warhol’s life: the St Vitus Dance, the swollen eyes, the broken arm, the scarlet fever.

(Source details for these are given in Dillon’s notes at the back of the book. In an academic paper, such references are footnoted.)

The writer never loses sight of his main thread—the artist’s illness-ridden early years—and the final sentence suggests why this matters: they were part of Warhol’s self-narrative about ‘physical and emotional enfeeblement’. This last idea leads to the next section, about the ongoing effects of Warhol’s sickly childhood in later life. By the essay’s end, Dillon has built enough evidence to propose a novel way of looking at Warhol’s beauty-obsessed art: its roots may lie in the contrast between his own ‘body’s frailty and of its potential for perfection’. Dillon begins to abstract meaning only once the reader is so steeped in verifiable details that she can follow the writer’s thinking—and choose for herself whether to nod along with the author’s interpretation, or not.

Dillon’s method—to scrutinize the artist’s life and the art in tandem—is disputed by some, who question the validity of extracting details from an artist’s biography as informing artworks.70 In all cases, be careful that you are not psychoanalyzing an artist based on ‘symptoms’ extracted from the artwork, a bad habit which, you might notice, Dillon avoids. His final interpretation re-thinks the art, not the man.

Unless these are knowingly implemented for dramatic effect to emphasize variety and excess, lists are deadly boring. Avoid listing more than three

+ names,

+ titles of artworks,

+ museums, galleries, or collections.

Drop partial lists, for example listing most—but not all—the artists in a group exhibition. In a journalistic or news-oriented piece particularly, if you list participants the roster must be complete. Take advantage of captions or subtitles to include all the names, dates, and venues. Adopt a system that follows a logical sequence; alphabetize indispensable lists of names unless you have reason to prioritize differently. Similarly, when listing artworks or exhibitions, arrange in chronological order (or follow another system suited to your text).

Lists can be stylish and evocative providing each element is actually of interest. Here is Dave Hickey, describing what sounds like his favorite decade:

That was the seventies—limos, homos, bimbos, resort communities and cavernous stadiums…the whole culture in a giant, Technicolor Cuisinart, whipping by, and I did love it so.

Source Text 14 DAVE HICKEY, ‘Fear and Loathing Goes to Hell’, This Long Century, 2012

Hickey’s rollercoaster rhyming list (‘limos, homos, bimbos’) has nothing to do with the detestable pile-ups of Kunsthalles and Kunstvereins some art-writers try to pass off as a legitimate paragraph. Include those awful name-dropping lists only as the bottom chunk of a press release, if you must.

Recall the ‘thick and viscous vocabulary’ that Stallabrass translated in his book review:

Exhibitions are a coproductive, spatial medium, resulting from various forms of negotiation, relationality, adaptation, and collaboration […]

This slick of buzzwords will date like fashionable baby names; old-school theory-jargon like ‘deconstructivist’ or ‘(meta)narrative’ are no less 1980s throwbacks than ‘Tiffany’ and ‘Justin’. In contrast, specialized art terminology is not jargon, and usually refers to infrequently recurring media and techniques or movements and art-forms:

+ impasto

+ trompe l’oeil

+ gouache

+ jump-cut

+ Fluxus

+ Arte Povera

+ site-specific art

+ new media art.

Numerous authoritative online resources exist for the precise definition of these.71 When writing for a general audience, only insert unfamiliar terminology if indispensable, and define in brief; sometimes it’s easier just to drop it.

Jargon is defined by the OED as ‘any mode of speech abounding in unfamiliar terms, or peculiar to a particular set of persons’. At times perfectly normal words (‘collaboration’; ‘spatial’) are so frequently injected into art-talk they turn jargony. Others are more perfidious: ‘relationality’? Find your own words; express your own ideas. Lighten up. Accept that art-writing can be a difficult job, but make the effort to write, not recombine jargon and pre-packaged issues.

This is an efficient but overlooked device in the art-writer’s toolbox: storytelling. Robert Smithson begins his illustrated essay ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’ (1967) with the story of his train-ride from Manhattan to the barren Hudson River shores, to soliloquize about the nature of industrial ruins. David Batchelor opens Chromophobia (2000), an irresistible book on the tyranny of colorlessness in contemporary ‘good taste’, with a terrifying visit to a well-heeled art collector’s oppressively all-white/gray home. Calvin Tomkins’s artist biographies—from Duchamp to Matthew Barney—whiz by as a collection of engrossing life-stories.72

Storytelling should be used judiciously for any institutional text (academic or museum texts). However, longer articles, artist’s statements, blogs, and essays can benefit from good, concise storytelling. An appropriate story makes for appetizing reading and can get plenty of pertinent information across.

The eminent Michael Fried interrupts his monumental ‘Art and Objecthood’ essay (1967) with a story—artist Tony Smith’s evocative account of a night-time car-ride along the empty American highway:

‘When I was teaching at Cooper Union in the first year or two of the fifties, someone told me how I could get onto the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike. I took three students and drove from somewhere in the Meadows to New Brunswick. It was a dark night and there were no lights or shoulder markers, lines, railings or anything at all except the dark pavement moving through the landscape of the flats, rimmed by hills in the distance, but punctuated by stacks, towers, fumes, and colored lights. This drive was a revealing experience. The road and much of the landscape was artificial, and yet it couldn’t be called a work of art. On the other hand, it did something for me that art had never done. At first I didn’t know what it was, but its effect was to liberate me from many of the views I had had about art […]. Most painting looks pretty pictorial after that.’

What seems to have been revealed to Smith that night was the pictorial nature of painting—even, one might say, the conventional nature of art.

Source Text 15 MICHAEL FRIED, citing Tony Smith, in ‘Art and Objecthood’, Artforum, 1967