How to Write Contemporary Art Formats

‘It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances’

OSCAR WILDE, 189074

One reason art-writers strain to find their own ‘voice’ is that the art-world today demands that we speak in tongues, adopting multiple registers—academic for an art-history journal; gossipy on a blog; ‘objective’ for a book caption; business-like for a funding application—to suit the panoply of evaluating, explaining, descriptive, journalistic, and other text-types required. This section will delineate the tone expected for each format and share tips. A big emphasis will be on structures:

+ the what is it?/what does it mean?/so what? trio of questions addressed when looking at artworks;

+ a basic essay outline for academic and multi-artist texts;

+ the inverted-triangle news format (big opener; tapering down with details of who/what/when/where/why; ending with a ‘sting’);

+ identifying a single key idea or principle to lead your writing through an artwork, project, or artist, which can even be no-frills chronological order.

As you progress, you can relax these frameworks, or mix them—or, better still, when these practised techniques have become habit, just write. But if you’re starting out, these guiding outlines are your new best friends.

Whether for class submission or publication in a specialist journal, an academic paper begins with a general area of interest. At worst, this is an anemic topic assigned by your teacher. At best, this is a gripping passion that has so ferociously seized your mind, you cannot sleep. Probably, your starting point lies somewhere in the middle. Ask your tutor for book/article recommendations. Or, begin by consulting pertinent anthologies, compendia, and series, such as:

+ Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford and Malden, M.A.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002;

+ Krauss, Foster, Bois, Buchloh, and Joselit, Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, 2nd edn, vols 1-2, London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012 (includes an exhaustive bibliography by topic);

+ ‘Themes and Movements’ series: (Art and Photography, ed. David Campany, 2003; Land and Environmental Art, ed. Jeffrey Kastner, 1998; Art and Feminism, ed. Helena Reckitt and Peggy Phelan, 2001, and more), London: Phaidon Press;

+ ‘Documents of Contemporary Art’ series: (Participation, ed. Claire Bishop, 2006; Memory, ed. Ian Farr, 2012; The Studio, ed. Jens Hoffman, 2012; Painting, ed. Terry Meyer, 2011; Utopias, ed. Richard Noble, 2009, and more), Cambridge, M.A. and London: MIT/Whitechapel;

+ Routledge’s ‘Readers’: Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, 2012 (3rd edn); Liz Wells, The Photography Reader, 2003, London and New York: Routledge.

You cannot rely solely on these overviews, and may need to seek out original full-length versions of abridged texts. All your texts cannot derive from a single anthology. Your sources must vary, and your bibliography demonstrate some effort and originality. Your institution or local library may have access to reliable, searchable online sources such as JSTOR and Questia for specialized articles.

Be smart with Google; one intelligent search leads to the next, but use only trustworthy institutional sources.

You may find an excellent online course, or an academic essay, with a thorough bibliography to begin your research. Note: You may not plagiarize existing material! Only consult the best-quality bibliographies to begin compiling your own first-draft reading list.

Read three or four essential texts on the subject; take notes. Summarize each article or chapter in a few sentences: what was the main point? Write down key information in short snippets, pertinent to your question. You need to collect evidence to substantiate your ideas later on; ‘evidence’ includes:

+ quotes from artists, critics, and key figures;

+ artworks;

+ exhibitions;

+ market data;

+ and historical facts.

Such evidence is at the service of supporting your own substantiated ideas: not just marshaled together to produce a report on the subject, like a fact-driven encyclopedia entry. Remember: a quote is evidence only of one person’s viewpoint; it may be well-informed, but is not an incontrovertible truth. (See ‘Explaining v. evaluating’ on artist’s quotes.)

Tag evidence with complete bibliography as you go along, so you’re not hunting for footnote details at the end: author, title, date, publisher/city, page number; volume and issue (for a magazine); or website address and date accessed (from a reputable Internet page). Footnotes are not just technical trivia; they show that the author takes seriously the job of substantiating ideas, and acknowledges the work of others.

Jot down any good vocabulary that you come across while reading, listing useful terms or phrases near the section where they might fit—a handy crutch when you’re at a loss for words at three o’clock in the morning, the night before submission.

After this brief but solid research, you might draw a freehand flow-chart, or timeline, or idea-map to begin making connections visually, and start clustering and prioritizing your interests in relation to your back-up evidence. You should be able to write down, in 40 words or fewer, an initial, focused area of investigation; often this is in the form of a research question. This first stab at a query may prove flawed, because it:

+ is a leading question (that suggests a predetermined answer);

+ is based on unqualified assumptions;

+ is too broad;

+ is too narrow;

+ is out-of-date;

+ cannot be researched, because no thorough and reliable information exists or can be accessed;

+ would require powers of clairvoyance.

Your research question may require rewording or refining as you progress; the longer the research time, the more modifications. A PhD inquiry might change a dozen times; a quick, three-week assignment, max once.

You should not anticipate the answer before you start, determined to ‘prove’ an idea in your essay. This is like a detective setting out to demonstrate that the butler did it instead of asking, who killed Roger Ackroyd? The job is not to find evidence to support a predetermined conclusion but to investigate an unknown. Take a look at the following examples:

Leading question: How have powerful galleries determined the course of art history?

This assumes that powerful galleries have determined art history, which may be true but needs to be adequately demonstrated. This question excludes innumerable other factors shaping ‘the course of art history’.

Unqualified assumption: How have private collectors today gained more power and influence in the art system than the commercial galleries?

This ‘question’ is an assumption in disguise, which asserts that collectors are stronger players than the private galleries today—without qualifying this. Which collectors? In relation to which galleries? How are you measuring ‘power and influence’?

Too broad: What has been the role of commerce in art history?

How many angels fit on the head of a pin?

Impossible to research: Are powerful galleries the most important factor in an artist’s success?

Too many variables prohibit answering this one plausibly. How do you define success—financial, critical, social, personal? And how do you factor in such unquantifiables as: talent; personal relationships; fashions in the art market; curators’ picks; an influential collector’s taste—or sheer luck?

Out-of-date: Do powerful galleries play a role in the validation of new art?

Absolutely, they do. This is too self-evident nowadays to constitute an actual query.

Requires a crystal ball: How will emerging art markets affect today’s contemporary art system? No prophesies, please.

Valid research question: What is the relationship today between commercial art galleries and museums in the UK? A case study on private-gallery acquisitions made by Tate Modern, 2004–14. This question focuses on a clear period and example, whose results can be determined through studying Tate acquisitions and pertinent comments from galleries, artists, and curators, among other sources.

Once you have formulated a viable question (which will form the basis of your 100–250-word abstract, if required), pursue more directed research. Be sure to elucidate—right away, in your Introduction—why you chose your principal artists, artworks, or case studies as representative, able to answer your research question meaningfully.

Make sure your question can be adequately addressed in the time allotted. Many researchers follow the rule of thirds—devote:

+ a third of your time to research;

+ a third to planning and writing your first draft;

+ a third to polishing your draft.

Quantify the time at your disposal, then divide accordingly. Notice that a good chunk is spent revising your draft; do not underestimate the time you will need to polish and finalize. This might entail some last-minute research to corroborate specific passages in your argument—as well as sharpening up language to ensure it all achieves ‘academic tone’. Do not rush that crucial third step!

Usually, students are fairly skilled at doing research and gathering pertinent material. Many struggle with the next steps, which distinguish valid academic research from just writing a report or pursuing a hunch:

+ focus on a precise, workable question, or corralled field of interest;

+ formulate your own argument(s), out of the evidence found;

+ select and structure all the material that you’ve dug up, based on your argument.

Here’s a basic outline for an academic essay at undergraduate or postgrad level. Make sure your reader is dead-sure what your essay is about by at least the end of paragraph two.

1 Introduce your question or topic (one or two paragraphs). Be specific!

(a) What is your argument or thesis, resulting from your research, through which you will approach your essay question or area of interest?

(b) Contextualize your topic. Clarity does not require a personality bypass but can be delivered with style, by opening, for example, with:

a description of an exemplary artwork or incident;

a well-chosen anecdote;

an over-arching quote.

2 Give background (2–4 paragraphs)

(a) History: Who else has thought/written about this? What were their main ideas?

(b) Define key terms: What definitions exist? Which will you be employing?

(c) Why should we care? What is at stake? Why is this topic important to think about now?

3 1st idea/section resulting from/building upon the above

(a) Example

(b) More examples

(c) 1st conclusion (very short essay: proceed to conclusion here)

4 2nd idea/section resulting from/building upon the above

(a) Example

(b) More examples

(c) 2nd conclusion (short essay: proceed to conclusion here)

5 3rd idea/section resulting from/building upon the above

(a) Example

(b) More examples

(c) 3rd conclusion (longer essay: proceed to conclusion here)

6 Final conclusion (not a reiteration of the introduction) Summarize main points and re-assert your argument in its most evolved form.

7 Bibliography and appendices: interview transcripts, charts, tables, graphs, questionnaires, maps, emails, and correspondence.

Add as many ideas as you like in the mid section. Each idea sub-section should be roughly equal in length. Most doctoral candidates repeat this pattern until they hit 80,000–100,000 words, having articulated a fairly brilliant argument which functions to hold the whole together, and constitutes the paper’s original contribution to the thinking around this topic.

Articulate an argument—or thesis, or main conclusion, or overall observation—drawn from your research, to guide you through your essay. Just piling on the broadly related information and interesting quotes you’ve come across, then dumping it all in your paper in a shapeless heap, will not make the grade. However, your thesis does not need to be a ravishing, Nobel-prize-winning theory. Just a plausible angle—like a thread running through the material, keeping your ideas together—is fine.

You must adopt your own perspective: the more original the better, it’s true, but to begin with, don’t sweat it. Keep bringing your reader back to the topic/research question and your argument or angle, perhaps at the end of every section, as a reminder of how each new reference relates to it. New points should develop your argument, adding nuances rather than just turning repetitious.

Don’t expect your reader to divine how your chosen examples fuel your idea; you must spell out the links. (See ‘How to substantiate your ideas’.) Become aware of digressive paragraphs or sections of marginal interest that are not wrapped within the main gist of your essay, and drop them. You will not use all the research you have uncovered; extract only the powerful examples which inform your exact topic and argument. Do not include all the material that you rejected in arriving at your argument, however vital that extraneous stuff was to your early thinking. Keep only what proved directly relevant—which can include a counter-argument, or examples showing that ambiguities exist, or an exception to your basic point.

New writers worry that the standard academic outline is boring or formulaic, and that it will produce an anodyne essay, but they confuse form with content. Pack the framework with compelling evidence, beguiling vocabulary, and dazzling artworks to support your staggering, jargon-free idea(s), and you will instantly triumph over its plain structure.

+ re-ordering sections somewhat;

+ offering new definitions and fascinating background throughout, not just at the start;

+ expanding upon, shifting, or even bisecting the argument;

+ introducing a counter-perspective, where the writer asks, Why might someone dispute my thesis? What might be alternative answers to my question? What are the exceptions to my general conclusion?

+ posing the central idea more as a second question than an ‘answer’, prompting new questions.

Always, each new idea is related to the previous one, and is supported by examples and evidence, building up your conclusion.

If you are struggling to organize all the material you have found (quotes, histories, examples), type a single key word, a thematic header, in front of each ‘chunk’ of information. Then hit ‘Sort’. Hey presto! All related ideas are magically clumped together, creating the informational backbone of each chapter.

Use the ‘Sort’ command to put your keyed-in research in order. For example, for a research paper on the contemporary Gothic, you might compile initial evidence into a single massive Word file, heading each piece with a one- or two-word theme (‘ruins’, ‘ghosts’, ‘haunted houses’). As research progresses, headers may grow subsections (‘ruins and 18th-century literature’; ‘ruins and modernism’); just keep track of these expanding themes to ensure consistency, then let ‘Sort’ cluster all related material together. This gives you an instant sense of which sub-topics are accruing more information, and starts the outline or flow-chart for your paper. Organize the separate sections into a sensible order, and drop any weak ones. From the pieces of evidence gathered for each sub-area, what provisional conclusion can you reach? Concentrate your energy not on mindless cutting and pasting but on analyzing your grouped information; developing brilliant ideas from the evidence; and devising intelligent transitions to join your sections coherently.

Don’t plagiarize, which means taking someone else’s work and attempting to pass it off as your own. Plagiarism is cheating; it reflects badly on the offender both ethically and intellectually, and is dealt with severely. Consequences can vary: resubmission; a failed grade or year; expulsion; even legal dispute. Never cut-and-paste off the Internet, unless it’s properly cited and verified. A ‘borrowed’ sentence or paragraph cleverly doctored with the occasional rewording is still plagiarism. Double-check your institution’s plagiarism policy (university guidelines often available online).75 You may also consult websites like www.plagiarism.org if you’re uncertain about what requires footnoting, how to cite sources properly, and more.

Don’t insert quotes to do the talking for you. The job is not to pluck out juicy quotes that reaffirm your conclusions—maybe expressing them better than you can—but to analyze what is said in relation to your thesis. Don’t overquote. Unless vital to your point, include one or two citations per page, tops: you must do most of the talking. Rarely extract more than four sentences from a single citation; unless you have good reason, keep quotes brief, usually well under 50 words.

Do cite reliable sources: such as an artist’s or other qualified figure’s quotes extracted from verifiable interviews, newspapers, books, and websites. Quotes should be drawn from an expert on the subject; for example, if your essay is about national arts-funding policies in Europe, it’s OK to ask a Madrid museum director about her publicly-funded budget, but—unless she has the proven expertise—not how this compares with, say, state monies available for the arts in Italy. If she offers information outside her expertise, double-check it.

Borrowed words substantiate only what these sources think. For example, an artist’s idea about her art might authentically express what she set out to accomplish—but this hope is not necessarily communicated for you in the artworks themselves. Always contextualize quotes by asking yourself, what larger point is this quote making within my argument? Make sure your reader knows how the citation has contributed to your thinking; don’t toss in quotes and leave your reader to forge connections.

Don’t jump from a really sketchy outline to writing full-blown text. The more organized your plan, complete with plenty of precise examples relating to each new idea, the easier the task of writing. Try outlining in reverse: with your completed (or half-completed) essay in hand, describe in a single word or line the gist of each paragraph. Does your ‘reverse outline’ stand up as a logical order? Does it build an argument? If not, reorganize your paragraphs (perhaps using the ‘Sort’ command trick to group connected material together); drop unrelated sections; and add transitions or missing information still required to build your idea.

Outlining in reverse: if you’re struggling to get the hang of outlining before you write, you can reconstruct your flow-diagram after you’ve written a first draft. Professionals often work this way: partially pre-planning; then writing ‘as it comes’; and finally revising paragraphs and re-ordering them into optimal sequence afterwards.

Eliminate any repetition, waffle, and digressions from your argument. Don’t generalize; be specific.

‘Artists in the early 1990s took “site” as central to their art-making.’

All 1990s artists, in all their art? Prefer:

‘Some artists in the early 1990s took “site” as central to certain artworks, such as Mark Dion’s On Tropical Nature (1991) and Renée Green’s World Tour (1993).’

Then go on to explain how this idea can be detected in these artworks. Do use transition words to connect one paragraph to the next, words such as

moreover, in fact, on the whole, furthermore, as a result, for this reason, similarly, likewise, it follows that, by comparison, surely, yet

Don’t enlist artworks or data as illustrations for your preconceived idea. Do not decide in advance what your sources must mean in aid of your thesis, turning research into a reversed operation of confirming preconceptions. As ever, look at artworks individually, and if pertinent explain:

Q1 What is it? Dates, location, participants; a description.

Q2 What might it mean?

Q3 What might this add to your thinking, or the world at large?

Do acknowledge contradictory information or limitations in your work. Students often ask:

+ what if I find conflicting evidence: market prices, collections, institutions, or artworks that ‘misbehave’ within my nice neat thesis?

+ do I just conceal pesky contradictions?

No; almost always there is conflicting evidence. Either acknowledge exceptions upfront

‘Not all of Thomas Hirschhorn’s monuments are dedicated to well-known political figures; for example…’

or allow the ‘contradiction’ to shape your ongoing research. Admit clearly any limitations in your work:

‘This paper will not survey the entirety of 1970s performance, but focuses on two salient examples from key figures Marina Abramovic and Vito Acconci.’

You cannot simply omit out-of-whack auction prices, or curators who behave differently from your description. Acknowledge exceptions, perhaps contextualizing their rarity:

‘Unlike many earlier Venice Biennale artistic directors, Bice Curiger of the 54th edition took an unusually cross-historical approach…’

However, if exceptions outnumber your thesis examples by a margin of 3:1, your argument is seriously flawed and requires rethinking.

If your research paper centers on one or two essential terms treat those special words as precious treasure, to be used sparingly (for example, ‘digital imagery’; ‘collaboration’; ‘interactive museum’; ‘emerging markets’). If your reader encounters them relentlessly in every sentence, those words (and your writing) will turn meaningless and tautological. (‘Tautology’ occurs when a term is defined by itself, such as ‘collaboration is collaborative’, or ‘interactive museums interact with the visitor’. Tautology is a big no-no.) Read Nicolas Bourriaud’s landmark book Relational Aesthetics (1998; English edition 2002)76 and notice how the author (even in translation) goes to great lengths to adopt multiple near-synonyms (‘conviviality’; ‘inter-human negotiation’; ‘audience participation’; ‘social exchange’; ‘micro-community’), developing nuances within his over-arching idea. Bourriaud limits the repetition of his magic words—‘relational aesthetics’—to keep them valuable.

Put effort into your bibliography. Here’s a secret: university lecturers set a lot of store by the quality of your bibliography, so build this up from the start. You may not have read every reference in depth; that’s OK. It must never be shorter than a page and must include plenty of challenging, pertinent books, not just Internet sources. Academics spot-check for ‘first-hand sources’: make sure you are familiar with Roland Barthes’s original Camera Lucida (1980) and not just The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French, however helpful that might be. If you quote from secondary sources, acknowledge the text’s nature as commentary; the original always take primacy.

Never cite a press release, wiki, or other unverifiable text unless you have a valid reason (for example, to quote an example of dubious online artspeak, see the gallery press release on Elad Lassry), and have plainly divulged the potential unreliability of this source. Triple-check any information you encounter there, and stick to reputable presses and websites.

First-hand research is a big plus: for example, your own interview with the artist, auctioneer, or curator; or an independent survey. Extract (and footnote) whatever quotes from the interview or survey that contributed to your understanding of the subject, and insert the whole transcript, questionnaire, or survey results in the Appendix. Be sure always to explain each piece of quoted evidence, and show exactly how it connects to your conclusions or pushed your thinking forward.

Footnote anything not considered ‘common knowledge’: quotes, statistics, historic events—particularly any controversial points. Follow the footnote style your institution adheres to, which in the USA and UK is most likely to be ‘Chicago’, ‘MLA’, or ‘Harvard’:

+ University of Chicago Press, The Chicago Manual of Style: The Essential Guide for Writers, Editors, and Publishers, Chicago, 1906 (16th edn, Chicago and London, 2010);

+ Modern Language Association of America, MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing, 1985 (3rd edn, New York, 2008);

+ Harvard Style can have minor variations, so check your institution’s guidelines. For a UK overview, see Colin Neville, The Complete Guide to Referencing and Avoiding Plagiarism, 2007 (Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2nd edn, 2010).

Sometimes institutions combine elements from each of these, or they follow the ‘Vancouver’ or ‘Oxford’ systems. If none is specified, pick one, and be consistent. If you’re really stuck, grab the most scholarly academic art-book at hand, and copy their system religiously. Footnotes are not a dumping ground to squeeze in extra information and get around stringent word counts. Stick mostly to the plain bibliographic reference. The little superscript footnote number always falls outside any punctuation.

Include the original publication date as well as the year of a recent edition. A citation such as ‘Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 2007’ looks as if the philosopher penned those words supernaturally some two centuries after he was buried. Prefer, for example, ‘Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Penguin Modern Classics, 2007’.

Here’s how a basic outline structure translates into an examplary academic essay, that begins:

Site-specificity used to imply something grounded, bound to the laws of physics. Often playing with gravity, site-specific works used to be obstinate about ‘presence’, even if they were materially ephemeral, and adamant about immobility, even in the face of disappearance or destruction. Whether inside the white cube or out in the Nevada desert, whether architectural or landscape-oriented, site-specific art initially took the ‘site’ as an actual location, a tangible reality [1] […] Site-specific works, as they first emerged in the wake of Minimalism in the late 1960s and early 1970s [2], forced a dramatic reversal of this modernist paradigm.

Source Text 22 MIWON KWON, ‘One Place After Another: Notes on Site Specificity’, October, 1997

Kwon’s essay charts the changes in site-specific art (the term and the works) since the 1960s. Kwon never literally states her research question; I am deducing this from the essay. It is a big question—the basis for a PhD; less advanced research would probably narrow this broad question down.

1 Introduce the question or topic: How has ‘site-specific art’ changed since the 1960s?

(a) What is the argument or thesis? From her starting point [1], Kwon will show how the idea of ‘site’, as a physical place, broadened over the decades, and how this shifting definition impacts artworks themselves.

(b) Contextualize your topic with an emblematic example: In her opening section, Kwon examines two key early artists, Robert Barry (quoted in a 1969 interview) and Richard Serra, and their initial ideas about this type of art.

2 Give background: Kwon establishes the art-historical framework of modernism.

(a) History: [2] Kwon contextualizes her starting dates.

(b) Define key terms: Tracking varying definitions of ‘site’ over the past 40 years constitutes the gist of Kwon’s paper, and this task of ‘defining terms’ recurs throughout.

(c) Why should we care?: Kwon takes the compelling case of Serra’s controversial Tilted Arc (1981) public sculpture, which was locally unpopular and proposed for relocation, and quotes a passionately defensive letter the artist wrote in 1985 explaining why relocating Tilted Art would alter, if not destroy, this artwork. (The artist lost his case.)

3 1st idea/section: For early practitioners of site-specificity, the important thing was to escape or critique the ‘stark white walls’ of the gallery.

(a) Example: Artist Daniel Buren, and his desire to ‘unveil’ museum spaces and other art institutions. (page 88 in Kwon’s published essay)

(b) Another example: Artist Hans Haacke, and his understanding of ‘site’ as shifting from ‘the physical condition of the gallery (as in the artwork Condensation Cube, 1963–65) to the system of socio economic relations’. (89)

Another example: Artist Michael Asher’s contribution to the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual exhibition in 1979, in which he set out to ‘reveal the sites of exhibition [as] not at all universal or timeless.’ (89)

(c) 1st conclusion: For this first generation of artists, ‘site’ coincided literally with the physical gallery.

4 2nd idea/section: For later practitioners, ‘site’ shifts from a location in the art system to one in the wider world.

(a) Example: Artist Mark Dion’s 1991 project On Tropical Nature, set in four different sites from the Orinoco River rainforest to gallery spaces. (92–93)

(b) More examples: ‘[I]n projects by artists such as Lothar Baumgarten, Renée Green, Jimmie Durham, and Fred Wilson, the legacies of colonialism, slavery, racism and the ethnographic tradition as they impact on identity politics has emerged as an important “site” of artistic investigation.’ (93)

Another example: Art historian James Meyer’s idea of a site as (Kwon quotes) ‘a process…a temporary thing, a movement, a chain of meanings devoid of a particular focus’. (95)

(c) 2nd conclusion: The idea of ‘site’ increasingly refers to a fluid, ungrounded ‘location’.

Kwon continues apace, with new ideas, relevant examples, and intelligent provisional conclusions, always returning to her main argument: the definition of ‘site’ changes over time, and this informs the changing nature of ‘site-specific’ art.

5 Final idea/section: The migration of the site-specific artist across international art-projects and events coincides with planetary waves of relocated peoples and refugees.

(a) Example: A quote from postmodernist theorist David Harvey, about our changing ‘world of diminishing spatial barriers to exchange, movement and communication’ (107).

(b) Another example: The idea of ‘contemporary life as a network of unanchored flows’ (108) can recall what philosopher Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari call ‘rhyzomatic nomadism’ (109).

Note: Before introducing theorists like Deleuze and Guattari, Kwon has thoroughly grounded her reader in the materiality of the artwork and the history of her subject, applying these philosophers’ ideas to an understanding of art—not forcing the artwork to ‘obey’ their concepts.

(c) Counter-example: Kwon recognizes that, although the physical ‘site’ may have become an abstraction for artists and the high-minded, it remains a material reality for the less privileged, and quotes theorist Homi Bhabha: ‘The globe shrinks for those who own it; for the displaced of the dispossessed, the migrant or refugee, no distance is more awesome than the few feet across borders or frontiers.’ (110)

6 Final conclusion: We might consider redefining ‘site’ as the differences and relations between locations, rather than reducing sites merely to an undifferentiated series, ‘one place after another’.

The purpose here is not to produce CliffsNotes-style bookends around Kwon’s important essay; moreover, another reader may interpret this essay’s meaning differently from this proposed outline. To save space I have omitted plenty more terrific examples and insights, and all Kwon’s perfect footnotes sourcing her claims. My point is to show how a good academic does not cram in every researched example, but selectively hones in on those that enrich her own powerful, guiding observation, building idea-by-idea, example-by-example, a perspective across the material. She does not ignore a counter-argument from Homi Bhabha which might disrupt her neat argument, but allows it to broaden her thinking.

Kwon’s essay represents highly accomplished, advanced academic writing; updated and expanded, this paper eventually became the basis for an important volume, One Place After Another, published by MIT (2002).77 Even the sharpest undergrad probably cannot match Kwon’s level of research and thought here; but don’t be daunted!

+ ask a workable essay question—don’t start with an assumption;

+ draw viable conclusions, deducted from the evidence you’ve gathered (see ‘How to substantiate your ideas’);

+ if possible, formulate your own consistent angle through which to organize a pertinent selection of examples.

Lastly, don’t forget to check submission requirements. Type up a cover sheet, usually with:

+ your name (or student number),

+ title of your paper,

+ date of submission,

+ name of your tutor or lecturer,

+ name/city of the institution.

Final checklist: proofread, and double-check unfamiliar spellings. Re-read the final draft at least twice. Unless otherwise directed, double-space; use point-size 12; insert page numbers; and keep minimum one-inch margins. Make sure paragraphs are indented. Read submission guidelines to ascertain where/when/how your assignment must be delivered. Submit on time!

> How to write a short news article

Brief, art-related news articles can appear today in everything from Elle Decoration to the Artillery (‘killer text on art’) website. The level of specialist information may vary, but all news items conventionally adopt the ‘inverted triangle’ structure—top-heavy, with a summary of the main facts as the opener, then working its way down in increasing detail.

1 Headline (and subheader): draw your reader’s attention with concise, up-to-date news.

2 The lead: front-load with an attention-grabber, perhaps a compelling anecdote that communicates what makes your story unique. Summarize enticingly the main events in first line or paragraph (max 50 words). This is the last place on earth for jargon, abstractions, or philosophical musings.

3 Who/what/where/when/how: in clear language, follow with contextualizing details, quantifying and backing up your claims with attributed quotes, numerical data, and other evidence. Avoid partial information.

4 Wind down and ‘end with a sting’: round off your main point(s).

In short, information is set in order of importance (see ‘Order information logically’). This format can be also applied to a short introduction for a longer article, or to non-journalistic texts such as the catchy website entry for a process-based artwork or an auction catalogue text.

Journalism builds from hard evidence drawn from first-hand data (interviews, eye-witness observation) and publicly available information (press releases, auction results). News articles are usually written in the third person, with little or no interpretative spin; for more opinionated journalism, see ‘How to write op-ed art journalism’.

> Basics

Keep your audience’s level of art-preparation in mind; most news articles should be comprehensible to non-specialists but of interest to the insider too. Straightforward, intelligently worded, solid information is readable in both camps. Avoid platitudes, or writing self-evident commentary off the top of your head: ‘The contemporary art-world is increasingly affected by market forces’—no kidding! Be specific and back up your statements with verified hard information, such as:

+ names of artists/galleries,

+ titles and dates of artworks,

+ sales figures,

+ visitor numbers,

+ prices,

+ costs,

+ exact times/dates,

+ dimensions,

+ distances,

+ and percentages.

Don’t bore your reader. Find a compelling story and write it up snappily, but don’t antagonize or overstate in order to falsely pump up interest levels. Journalism races along in the active tense, with clipped sentences that keep the subject/verb in close proximity, with few modifiers and punchy—never academic—language. Ensure accuracy. If necessary, seek out any missing data from authoritative and attributable sources.

The pages following extract the journalistic building-blocks (listed above) as found in two published news items. The first article contextualized protests in Brazil, and followed a longer piece about billions being spent on new ‘cultural districts’ in places as distant from each other as São Paulo, Kiev, Singapore, and Abu Dhabi; the second reported on the newly stabilized Hong Kong art market.

Artists take to the streets as Brazilians demand spending on services, not sport [1]

São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro. ‘Come to the streets!’ urged the banners held aloft during mass protests in Brazil last month. What started as a rally against a rise in bus fares flared into a nationwide show of discontent as more than a million people marched on 20 June [2] […] The demonstrators demanded that public services be given priority over the 2014 Fifa World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. Huge spending on the events—the cost of stadia and improvements to infrastructure ahead of the World Cup has risen to R$28bn ($12.4bn)—is taking place during an economic slowdown. Last year, the country’s growth slowed to less than 1% [3]. ‘We’re getting first-world stadiums but we don’t have first-world education and health’, says the curator Adriano Pedrosa, who took to the streets. ‘When you have a democratic country of so many sharp contrasts, the population really protests.’ [4]

Source Text 23 ‘C.B.’ (CHARLOTTE BURNS), ‘Artists take to the streets as Brazilians demand spending on services, not sport’, The Art Newspaper, Jul/Aug 2013

Hong Kong Spring Sales Reach More Solid Ground [1]

The Spring sales for Sotheby’s, in Hong Kong, which took place from 3 to 8 April, came with some reassuring news for Chinawatchers in the auction world. It exceeded expectations coming in at HK$2.18 billion against a pre-sale estimate in excess of HK$1.7 billion [2]. […] The Asian contemporary sales still seem to be struggling to match earlier higher prices, but were helped past their pre-sale estimates by You Are Not Alone by Yoshitomo Nara, which sold for over HK$41million, more than doubling its pre-sale estimate of HK$18million. Elsewhere in the contemporary Asian sales some works were left unsold (perhaps because of some ambitious estimates) [3] […] All in all, the sales sent a message of firmer ground [4].

Source Text 24 UNSIGNED, ‘Hong Kong Spring Sales Reach More Solid Ground’, Asian Art, May 2013

[1] Headline: ensure that your ‘news’ is newsworthy.

[2] The lead: a ‘hook’, which engages a reader’s interest.

[3] Who/what/where/when/how: be thorough; if pertinent, present different sides of the story. If any information is conjecture, or rumor, either drop it or make its uncertainty evident: ‘some works were left unsold (perhaps because of some ambitious estimates)’.

[4] Wind down and ‘end with a sting’: encapsulate your main point. Usually, give at least a brief introduction to named sources (‘the curator Adriano Pedrosa’), and quote their words precisely.

> How to write a short descriptive text

+ art-fair catalogue copy

+ museum labels

+ biennale guidebooks

+ art-website blurbs

+ extended captions

+ exhibition wall texts.

The proliferation of bite-size art-copy attests to what can be described as the ‘cult of brevity’ in today’s Twittering art-world whereby art must be grasped rapidly and consumed in bulk. Commissioned mini-text writers—frequently unnamed—often must:

+ balance concise, pertinent, updated facts with meaningful ideas;

+ cater to everyone from schoolchildren to seasoned experts;

+ condense a complicated multi-part artwork into just a few sentences.

Writing these short texts intelligently demands far more skill than is generally recognized, and should never be written unguided by inexperienced interns or paid by the word. Agonizing over those precise 150 words requires absolute discipline. Make no mistake: composing smart super-short texts is a disproportionately far tougher job than luxuriating in the 2,000+ words of a roomy catalogue essay.

> Basic technique

Usually, to write a very brief piece, the most common strategy is to identify one main theme or angle through which to examine the art. You cannot cover everything, so choose your focus well. It may be:

+ materials,

+ process,

+ symbolism,

+ political content,

+ biography,

+ a controversy,

+ or technique.

Research the artist, look carefully, and discern the one key thread running through the text. You can employ a comparison, which might be a smart metaphor or simile. Be specific; your focus or point can be relatively minor: not ‘this artist questions all the ideologies underpinning the spectrum of 21st-century politics’. You might borrow the news-writing inverted-triangle structure (section 3.2) to fit all your information in—especially applicable in a newsy promotional blurb. Set your purple-prose radar on high alert; blinding red lights should flash if you write, ‘this ravishing artwork laments the heartbreaking puniness of all human existence’. Stay focused. Make every word count.

Consider viewing/reading conditions: art snippets might be read peering over shoulders in noisy galleries; on a tiny mobile-phone screen; or touring an exhibition, guidebook in hand. Even an ‘unsigned’ text should display some style, but err on the side of factual rather than flamboyant. Keep sentences crisp and to the point. Your text length may end up determined by the size of a Perspex label holder, usually about 150–200 words. If you are working without the help of an experienced curator, check that your texts will fit in the plastic before writing them. For large exhibitions, consider what belongs in the introductory panel—which is read by more visitors—and what goes on the wall labels. Avoid repetition.

If you write your description before the artwork arrives, double-check whatever comes out of the crate matches your words. Reproductions can be deceptive. Very occasionally, the artwork you unpack may not even be the one you were expecting (long story). You will then need to scrap your meticulously researched text and frantically rewrite.

Accuracy: all caption details must be checked, double- and triple-checked. You are writing art history; take this seriously. Is it a film, or a video? For references, look to:

+ catalogues raisonnés;

+ first-hand, fact-checked, reliable information;

+ trusted Internet resources (major museums, the artist’s own website, Grove Art online);

not any crackpot with a web address. Be careful when translating titles; there may be an official English-language translation that you need to stick to.

When faced with a particularly arduous brief, new art-writers might instantly throw up their hands in defeat. How can we sum up a two-hour film, or a three-month multi-part performance work, even a 50-year career, in just 150 words? What about artworks that are stuffed with unrelated imagery, or open-ended, or deliberately sprawling and chaotic? Isn’t reducing these hydra-headed artworks to a tame paragraph an impossible and contradictory task?

Contradictory, perhaps; impossible, no. Of course, one hopes that these mini-texts serve only to assist—rather than replace—the time readers will spend looking at the art. Here are a few special-challenge briefs (writing about a long career; a moving-image work; a highly detailed image; an open-ended or multi-part project; digital media) and a sampling of techniques that art-writers have adopted with them.

> How to write in brief about a long career

Ideally, such a text is penned by a venerable expert, steeped in 30 years’ first-hand study and observation, whose scholarship permits them to distill the very essence of an artist’s multi-decade oeuvre. Let’s say that you, in contrast, only learned to pronounce this artist’s name correctly five minutes ago. In this case, you will have to hit the library hard. Plan to read about ten or 20 times as much copy on the artist as you are asked to produce.

Here, in an extract from the Frieze Art Fair Yearbook, Martin Herbert manages to condense some 50 years’ of sculptor Richard Serra’s career into a four-sentence paragraph.

Richard Serra, born 1939, lives New York/Nova Scotia

Richard Serra is one of the most significant figures in contemporary sculpture, pivotal enough for museums and commercial galleries to have scaled their spaces with his enormous steel plates [1] in mind. Such monumental works may seem far removed from Serra’s thrown lead pieces of the 1960s [1]: throughout his career, however, he can be seen to have conducted a pioneering investigation of the properties and poetics of industrial metals [Th], particularly their physical and visual weight and occupation of space [2]. Recent projects such as Promenade (2008) [fig. 22], his row of 17-metre-high vertical plates [1] for the Grand Palais in Paris, suggest that Serra continues to push the boundaries of this exploration. Here, massiveness combines with subtle irregularities of placement which, on this scale, have grand effects on the audience [3].

Source Text 25 MARTIN HERBERT, ‘Richard Serra’, Frieze Art Fair Yearbook, 2008–9

fig. 22 RICHARD SERRA, Promenade, 2008

Herbert informs us of the artist’s status (‘one of the most significant figures in contemporary sculpture’), which for once is justifiable, and substantiates that hefty claim: ‘museums and commercial galleries […] have scaled their spaces with [him] in mind’. He then fulfills the three-part job of communicative art-writing (see ‘The three jobs of communicative art-writing’). Do not underrate the skill required to single out the right idea, and make it stick.

Theme: ‘A pioneering investigation of the properties and poetics of industrial metals.’ [Th]

Q1 What is it?

A A concise description of the heavy late work is set in contrast with earlier, lighter examples [1].

Q2 What might it mean?

A Serra’s weighty materials draw attention to two basic attributes of sculpture. [2]

Q3 So what?

A Herbert’s reiteration of the impressive scale of Serra’s sculptures returns neatly to his opener, about museums scaling their spaces around the artist’s often gigantic art, and might connect to the viewer’s own experience of this mammoth artwork [3].

If you’re stuck finding a workable theme to guide you through a big-name long-career artist, you can always ‘cheat’: recycle a key idea summarized by the artist’s associated big-name long-career critic, as found in your initial research. Convey the artist’s stature within art history (Who is he or she?) without lapsing into hagiography. Get to the crux of what makes the artist important, then back it up with choice examples from varying stages in the career.

> How to write in brief about moving-image art

Inexperienced art-writers ponder how to squeeze a whole film into a short text, plus offer a modicum of analysis. Again, discover a guiding idea that runs through the art, then back it up with a couple of succinctly described examples: whether two separate artworks, or a pair of key moments or images extracted from a single work.

Andrew Dadson, born 1980, lives Vancouver

Andrew Dadson is a mischievous neighbor [Th]. In his series of deviant acts [Th], which he documents in photographs [1], he has literally and figuratively jumped his neighbors’ fences [2]. The two-channel looped video Roof Gap (2005, [fig. 23]) records him leaping from roof to roof [1] around his neighbors’ houses. Following a dispute, Dadson performed and documented Neighbour’s Trailer (2003), in which the artist gradually moved his neighbor’s parked trailer inch by inch closer to his house [1] every night. In a similarly anarchic ongoing series Dadson turns objects of suburban division, such as fences or lawns, into black monochrome paintings using black paint. These irreverent ‘Land art’ works attempt to reclaim the increasingly privatized suburban landscape by breaching its staid boundaries [3].

Source Text 26 CHRISTY LANGE, ‘Andrew Dadson’, Frieze Art Fair Yearbook, 2008–9

fig. 23 ANDREW DADSON, Roof Gap, 2005

Theme: The artist’s identity as a ‘mischievous neighbor’ engaged in ‘deviant acts’ [Th].

Q1 What is it?

A Photographs, as well as two moving-image works, are briefly described [1].

Q2 What might it mean?

A The artist ‘literally and figuratively jump[s] his neighbors’ fences’ [2].

Q3 So what?

A Lange sets Dadson’s work both in the context of art history (Land art) and as a social commentary about the powerful public/private boundaries that define suburbia [3].

Lange uses storytelling to encapsulate Dadson’s two time-based works, turning each performance piece into a one-line tale to get across her main theme: the artist-as-mischievous-neighbor. She employs a wealth of concrete nouns (‘fences’; ‘roof’; ‘houses’; ‘trailer’; ‘inch’) and active verbs (‘jumped’; ‘leaping’; ‘breached’) to help readers picture Dadson’s ‘deviant’ suburban mischief. Don’t attempt a blow-by-blow summary; encapsulate the thrust of the action, then explain why it might matter.

fig. 24 AYA TAKANO, On the Way to Revolution, 2007

> How to write in brief about a highly detailed artwork

Multiple unfamiliar figures and objects drift across Aya Takano’s artworks; here’s how Vivian Rehberg gets to grips with the Japanese artist’s floating comicbook fantasyland—while suggesting where it may be heading.

Aya Takano, born 1976, lives Japan

A member of the Kaikai Kiki corporation, founded by Takashi Murakami, Aya Takano is known for her liquescent drawn and painted images [1] influenced by popular culture [Th], and the post-Manga Superflat aesthetic. Built out of pale washes and colors [1], her fantasy worlds [2] are populated by lean girls with budding breasts and juice-tinted lips, who frequently cavort with animals or other lovely-looking youths in imaginary lands or cityscapes. On the Way to Revolution (2007, [fig. 24]) is typical of her approach: a massive horizontal painting [1] of bright chaos where doe-eyed figures rush and tumble toward the foreground streaming planets, stars, helium balloons, fashion accessories, and creatures both real and imaginary [2]. After all, what else should you pack for a trip to Utopia? [3]

Source Text 27 VIVIAN REHBERG, ‘Aya Takano’, Frieze Art Fair Yearbook, 2008–9

For the London art-fair crowd reading this text, Rehberg helpfully sets Takano in relation to the noted Japanese Superflat artist with whom her audience may be familiar; then she sets up her theme and addresses the three tasks of communicative art-writing.

Theme: ‘images influenced by popular culture’ [Th].

Q1 What is it?

A ‘liquescent drawn and painted images…built out of pale washes and colors’; ‘a massive horizontal painting’ [1].

Q2 What might it mean?

A Takano’s ‘fantasy worlds’ are ‘both real and imaginary’ [2].

Q3 So what?

A The writer imagines that Takano’s assortment of goodies could provide the necessities ‘for a trip to Utopia’ [3].

Notice all the concrete nouns with which Rehberg shows how stuffed Tayano’s canvases are with the flotsam and jetsam of Japanese popular culture: ‘girls’, ‘breasts’, ‘lips’, ‘animals’, ‘youths’, ‘cityscapes’, ‘planets’, ‘stars’, ‘balloons’. Concise description is further achieved through wonderfully picture-forming adjectives (‘juice-tinted’, ‘doe-eyed’) and active verbs (‘rush and tumble’). Abstract nouns are limited, and arrive mostly at the end, when we’ve got a handle on the art: ‘chaos’, ‘Utopia’.

> How to write in brief about an open-ended artwork

How can an art-writer encapsulate an artwork that sets out to be limitless, or unpredictable, without betraying the unconfined nature of the art? These writers, Mark Alice Durant and Jane D. Marsching, do not flatten out the maddening heterogeneity of this sprawling sound/Internet/installation artwork, but offer a sampling of the erratic sources one might encounter there.

fig. 25 MARIA MIRANDA AND NORIE NEUMARK (OUT-OF-SYNC), Museum of Rumour, 2003

Out-of-Sync, a collaboration between Australian artists Maria Miranda and Norie Neumark, has been producing radioworks, websites and installation for over ten years. Their fictive investigations of the murky border regions include ‘anomalies, rumor, difference, Gertrude Stein, ducks, everyday life, trees and frogs, Jules Verne, volcanoes, Jorge Luis Borges [1]—through a variety of “scientific” approaches, from rumourology to emotionography to data collecting’ [2]. Museum of Rumour [3] [fig. 25] is both an Internet work and a site-specific installation, originally installed in 2003, [in which] [p]erfectly reasonable scientific claims are set against random and marginal visions.

Source Text 28 MARK ALICE DURANT AND JANE D. MARSCHING, ‘Out-of-Sync’, in Blur of the Otherworldly, 2006

Durant and Marsching do not attempt to define all the esoteria (‘emotionography’) tossed into Out-of-Sync’s work but hint at the variety of unrelated sources [1] and methods [2] that you might encounter there. The writers borrow a list-like quote from the artists to show the unpredictability of their references, and suggest how, for Out-of-Sync, these mirror the random content of a rumor or some pseudo-sciences. The focus on one specific work, Museum of Rumour [3], and visually loaded details (‘ducks’, ‘volcanoes’) gives the reader a good general impression of this artwork as a multi-media grab-bag that combines science, literature, film, religion, and more.

> How to write in brief about a multi-part project

Increasingly, 21st-century artists are engaging in complex artworks that unfold over time, involve multiple partners and media, and extend well beyond the gallery walls. In this brief text for the dOCUMENTA (13) exhibition catalogue, which presents artist Seth Price’s year-long project spanning art and fashion, occasional art-writer Izzy Tuason wisely chose to address its two principal elements—clothing and sculpture—by presenting their uniting themes:

A piece of clothing is similar to an envelope [1]: both are cut from a flat template, folded, and secured shut. Each is an empty package, awaiting content and subsequent travel [2].

In 2011, Seth Price designed a group of clothing in collaboration with New York fashion designer Tim Hamilton. Based on military tailoring, the collection of lightweight garments includes a bomber jacket, flight suit, and trench coat, among other items. Outer shells are raw canvas, a fabric with traditional military and artistic uses. The interior lining is printed with security patterns taken from the inside of business envelopes; such patterns typically feature a repeating bank logo or abstraction […]

Meanwhile, Price prepared a second group of works for dOCUMENTA (13)’s exhibition space at Kassel Hauptbahnhof. Developed in parallel to the clothing line, these huge, wall-mounted business envelopes are fabricated from the same materials—canvas shells, logo-patterned liners, pockets, zippers, arms and legs—and within the fashion industry [3], using Hamilton’s professional network of seamstresses, pattern-makers, and factories. In the sculptures however, the ratios between the ideas are skewed differently: more ripped-open envelope than garment, they are hardly wearable. Here the human form is tacked on awkwardly, limbs dangling as from animal pelts. […]

At dOCUMENTA (13) the two groups of work are juxtaposed, one in the exhibition halls, the other available for sale to the public […] [4].

Source Text 29 IZZY TUASON, ‘Seth Price’, The Guidebook, dOCUMENTA (13), 2012

The writer explains key differences between Price’s two ‘products’, clothing and sculpture (one is wearable while the other is not, for example), but connects them for the reader in multiple ways:

[1] both are inspired by envelope design;

[2] both share a common theme: the empty package;

[3] both are made of canvas and produced by garment workers;

[4] both are ‘available’ at the exhibition, whether on sale (clothing) or on display (sculpture).

The information has been organized chronologically, working from a general theme (the ‘empty package’) to the specific details of each intervention. Solid nouns keep the description concise:

+ ‘bomber jacket, flight suit, and trench coat’

+ ‘business envelopes’

+ ‘liners, pockets, zippers, arms and legs’

+ ‘seamstresses, pattern-makers, and factories’

+ ‘animal pelts’

This writer successfully avoids a few art-writing traps. He does not attempt a potted history of the art/fashion crossover; neither does he attempt to survey this artist’s entire, varied career but follows one well-identified theme, chronology, and logical order to describe succinctly this complex artwork.

> How to write in brief about new media art

With new-media art, writing succinctly and labelling accurately have only got harder. Artist and researcher Jon Ippolito has demonstrated how, for computer-based installations and video multicasts, even compiling basic caption information—author, date, medium—can pose a minefield of uncertainty.78 Digital art is often produced by a shifting cast of collaborators, and varies in format (technologies, dimensions) when relocated from, say, the artist’s website to an online art magazine, or public display in a gallery or festival.

The following public-collection website entry regarding one version of a live web-feed work, Decorative Newsfeeds, has been modified from artists Thomson & Craighead’s own description of their project.79

Decorative Newsfeeds (2004) presents up-to-the-minute headline news from around the world as a series of pleasant animations, allowing viewers to keep informed while contemplating a kind of readymade sculpture or automatic drawing [1]. Each breaking news item is taken live from the BBC website [2] and presented on-screen according to a simple set of rules, and although the many trajectories these news headlines follow were drawn by the artists and then stored in a database, the way in which they interact with each other is determined by the execution of the computer program. Decorative Newsfeeds is an attempt to articulate the rather complex relationship we all have with rolling news and how such simultaneous reportage on world events impinges on our own lives [3].

Source Text 30 UNSIGNED, ‘Decorative Newsfeeds’, Thomson & Craighead, 2004, British Council Collection website

For this complex, constantly evolving new-media work, the short descriptive text assists visitors by explaining exactly what they are looking at. Each of the three sentences assumes one task, albeit inverting the order of what I’ve called ‘The three jobs of communicative art-writing’ (see ‘The three jobs of communicative art-writing’), and answering a question:

Q2 Why is this meaningful?

A Decorative Newsfeeds, as well as being an artwork, presents newsfeed, ‘allowing viewers to keep informed while contemplating a kind of sculpture’ [1].

Q1 What is it?

A ‘News item[s] taken live from the BBC website’ that interact with a computer program [2].

Q3 Why might this be worth thinking about?

A The work is ‘an attempt to articulate [how] world events impinge[ ] on our own lives’ [3].

Website entries for digital art often require constant updating; a new media artwork ‘must keep moving to survive’—like a shark, as Ippolito puts it.80 Dates are especially slippery; an ongoing digital work begun in 2004 but subsequently revised can be dated ‘2004’, ‘2004–ongoing’, ‘2004/2014’, or more. If possible, seek first-hand information directly from the artist or their authorized website.

> Notes on exhibition wall labels

Viewers spend an average of ten seconds reading a museum label;81 a writer will put in hours of research to extract the right ten-second text. Attentive observers like artist Meleko Mokgosi in Modern Art: The Root of African Savages (2013, a heavily annotated museum label riddled with her handwritten commentary), can expose the many assumptions therein.

Avoid the Sesame Street-level content of this label, which Burlington magazine spotted accompanying a Braque still-life in a Glasgow museum:

If Georges Braque was struggling with a complex painting, he would often paint still lifes to clear his mind. The bowl of fruit in his studio also provided a handy snack!82

You don’t want contemporary-art skeptics to declare that, not only could their three-year-old create better art, she could compose more illuminating text to go with it. Only research raises your label above such infantilizing trivia. Your label may also need to let visitors know what they can or cannot do; whether they are invited to:

+ touch the artwork,

+ operate the handle,

+ move the mouse,

+ take a sheet;

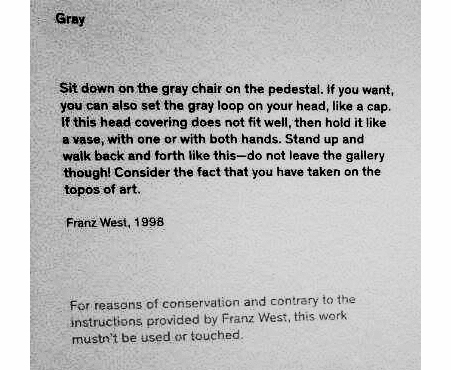

or, as in the case of this label photographed at MuMOK, Vienna in 2012, ignore the artist’s original commands (Franz West self-contradicting museum label, fig. 26).

fig. 26 Franz West self-contradicting museum label, MuMOK, Vienna. Photo Catherine Wood

> On the house: following house style

If you are asked to write for an established museum or collection (or publisher), they will have a ‘house style’ that ensures consistency across all their texts. Get a copy, and obey it to the letter. Is it circa, c. or c.? If you need a reliable example, look up a favorite professional website (say, the Art Gallery of Ontario, or San Francisco MoMA—there are hundreds) and follow their system. Check (or decide, and stick to) policy for every detail, and be consistent. For captions, often the order is: artist; title; date; medium; dimensions; collection. Additional information can include: photographer; provenance or acquisition history; collection reference numbers. Unless otherwise specified, for wall labels choose a 14-point font size or larger, always sans serif, to ensure legibility.

> How to write a press release

Truly, the saga of the contemporary art press release deserves a chapter unto itself. In most other sectors, this modest sheet of A4 serves merely to:

+ inform the industry, an editor, or a reporter of a newsworthy item, usually bearing a banner-line header for instant communication, in the hope of media coverage;

+ provide journalists with the bare-bones, plain language from which to pen a news item;

+ offer full contact info details (‘for further information, please contact’); a decent copyright-free picture, and a pertinent quote or two. Job done.

The press release is structured as a no-frills ‘inverted triangle’ (see section 3.2): an infomercial that prioritizes news in order of importance. Once upon a time, art-world exhibition press releases were likewise fairly normal, useful one-pagers where a journalist would find straightforward information.

Here are the key elements extracted from two relatively sober examples (by art-world standards): one announcing the recipient of a notable art prize, ‘Stan Douglas wins the 2013 Scotiabank Photography Award’; the second about a private gallery solo exhibition, artist Harun Farocki on view at Raven Row, London, 2009.

Scotiabank is thrilled to announce that Vancouver’s Stan Douglas has been named winner of the third annual Scotiabank Photography Award [1] […] The prestigious prize provides the winner with $50,000 in cash, a primary Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival exhibition in 2014 and book to be published worldwide by international art publisher Steidl [2].

‘Stan Douglas has helped define and enrich the Canadian art and photography landscape with his outstanding artwork,’ said Edward Burtynksy, Chair of the Scotiabank Photography Award jury and co-founder of the Award. [3] […] Based in Vancouver, Stan Douglas has created films, photographs, and installations that reexamine particular locations or past events [4]. […]

Stan Douglas was selected from a group of three finalists, which included Angela Grauerholz and Robert Walker, by a jury of some of photography’s most respected experts: William Ewing, Director of Curatorial Projects, Thames & Hudson […]; Karen Love, Independent Curator and Writer, Director of Foundation and Government Grants, Vancouver Art Gallery; Ann Thomas, Curator, Photographs Collection, National Gallery of Canada [5].

Source Text 31 UNSIGNED, ‘Stan Douglas wins the 2013 Scotiabank Photography Award’, 2013, Scotiabank website

[Raven Row announces] the first UK exhibition of the two-screen and multi-screen works of revered German filmmaker Harun Farocki [1]. […] The survey comprises nine video installations from his first two-screen project Interface in 1995 to Immersion, 2009, about the use of virtual reality in the treatment of traumatized US soldiers following the occupation of Iraq [2].

Since the sixties, Farocki (born in 1944, living in Berlin) has reinvented what can be described as the film essay. […] In the mid-nineties, Farocki began making films for two, and occasionally more, screens [4]. […]

The exhibition is curated by Alex Sainsbury. It is linked to ‘Harun Farocki. 22 Films 1968–2009’, a season of Farocki’s single-screen films and events at Tate Modern, 13 November–6 December 2009, curated by Stuart Comer, Antje Ehmann and the Otolith Group [5].

Source Text 32 UNSIGNED, ‘Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom?’, 2009, Raven Row website

[1] A one-line header, or short paragraph, with the main announcement;

[2] information about the immediate event or exhibition (up to four lines)—what is the award; which works are on view;

[3] a pertinent (jargonless) quote;

[4] essential background on the artist (up to four lines);

[5] a short final paragraph with the fine print.

In addition, include the gallery’s details: address, opening hours, website/email, phone number; name of press contact. (Separately), send a directly relevant, good-quality picture (minimum resolution 300dpi), available for usage, with all caption info: artist, title, date, medium, dimensions, venue, name of photographer.

If you follow the above basic model, first take an oath to obey the section, Do not ‘explain’ a dense, abstract idea with another dense, abstract idea. And if, despite your efforts, when you’ve finished writing the press release you are somehow too ashamed or otherwise reluctant to show the artist your text about her own show, that is a bad sign. Rewrite it, keeping the words simple but smart.

> Practical tips

Choose the right photograph. A picture is worth a thousand blurbs. You want a clean and highly legible image, usually of a recent work: the press always want super-current—or, even better, tomorrow’s—news. To judge how well a photograph will print in a newspaper, photocopy it in black-and-white: if the photo dies in a sea of gray, pick another where the image stands out, with starkly contrasting darks and lights. (This trick works even if the image will be published in color or on the web.)

Presentation and clarity are paramount. For print-outs, prefer double-if-not-triple-spaced, breathable press releases from which the journalist can extract the essential information effortlessly. An art-critic will glance over the press release and absorb the headline artist/gallery/exhibition, or scan for key facts. Be sure always to include any really basic background info: materials; process, or how the work was made; perhaps how the artist arrived at this idea—hard information, rather than conceptual jibber-jabber. A pertinent artist’s, curator’s, or critic’s statement (always missing; why?) might throw some light on what’s going on. Fabulously comprehensive gallery or artist websites, with every scrap of criticism, interviews, artist’s statements, catalogue texts, and images of artworks, provide any critic with all the research she will ever need. Facilitating tactics like these help attract coverage.

No member of the press is ever going to open your email and promptly drop everything to rush and see the ‘first-ever exhibition in Antwerp of this exciting new-media artist, born 1973 in Wysall’. For mainstream press interest, you will need a newsworthy, eye-catching, general-audience hook. Perhaps your exhibition showpieces a human skull, covered in 8,601 diamonds, with a 52.4 carat pink diamond on its forehead and carrying a £50 million price tag? Or, all proceeds go to Amnesty International; or the artist worked with disadvantaged kids—that sort of thing? At the very least, to gain broad (non-specialist) coverage your exhibition must be connected to a book-launch, new film, or major exhibition; or it must include outrageously rare or valuable work.

Having a genuine art-critic review your show is a subtler endeavor. Art-critics receive daily many dozen gallery press releases, the majority of which they delete unread and in bulk. In general, their review choices are independently made, and drawn from regular rounds of the galleries; occasional leads from trusted colleagues; artist studio visits; art-world buzz; some online research. Artists—when they’re not plugging their own shows—can be reliably counted upon for valuable go-see recommendations. If you want the critics to beat a path to your gallery, here’s my advice: make friends with as many art-critics as you can, put on the best exhibitions that you are able, then do whatever it takes to get them through the door (see FAQ, ‘How to write an exhibition review for a magazine or blog’)

There is no law stating you must produce a single, one-size-fits-all press pack. Consider tailoring the content and quantity of press materials to suit the needs of your target media.

Make your news super-easy to insert, as is. Galleries expect magazine staff writers to do all the hard work of transforming the impenetrable prose and partial information in their press release into publishable news. No hyperbolic praise seemingly written for and by the artist’s mother (‘the world’s greatest living sculptor’); no artspeak lunacy; no missing information (who-what-where-when-how-why, all present and accounted for), with a punchy headline and media-friendly quotes, plus a copyright-free, exclusive, fully captioned, high-res photograph.

> Fifty Shades of Press Release

Oddly, as contemporary art gets hotter, the gallery press release seems only to grow more daft. This curious sheet of A4 persists as our dottiest institution: a law unto itself. Ghostwritten by interns; burdened with the contradictory task of both clarifying and mythologizing the art on view; religiously ignored by the press, ‘gallery press release’ is an accepted misnomer. Yet some day, when these are all professionally compiled by PR firms staffed solely by Ivy-league communications grads, we might miss those nutty print-outs, all typos and non-sequiturs and run-on sentences. The gallery press release is art-writing’s favorite problem-child.

Perhaps the press release serves to compensate for the dearth of actual coverage, and fulfills mostly ritualistic functions (see the Introduction); at least somebody wrote something if a press release exists. Some have embraced the special weirdness of this document and invented variations based on the paradox of the ‘signed press release’, likely to leave gallery-goers visibly more—rather than less—mystified. That is their point. The press-release-as-mini-exhibition-catalogue can take the form of:

+ an extended artist’s, curator’s, or critic’s statement: such as artist Christopher Williams writing on his own show, David Zwirner Gallery, New York, Jan—Feb 2011;83 critic Mike Sperlinger writing on sculptor Michael Dean, Herald Street Gallery, London, May 2013;84

+ commentary from another artist: such as artist Francesco Pedraglio, for Marie Lund at Croy Nielsen Gallery, Berlin, Sept—Oct 2012;85

+ creative writing: such as J. Nagy, on Loretta Fahrenholz at Halle Für Kunst Lüneburg, May 2013;86

+ innovative graphics/stand-alone artwork: such as Charles Mayton at Balice Hertling, Paris, Dec 2012;87

+ a collection of ‘parables’ loosely related to the show’s theme: such as A.E. Benenson, for Torrance Shipman Gallery, Brooklyn, New York, Mar–May 2013.88

Curator Tom Morton’s revised press release/interview for his ‘Mom & Dad Show’ at Cubitt Gallery, London (February 2007; the exhibited artists are the curator’s parents) revealed all the ‘track changes’ and behind-the-scenes commentary, to help us grasp what an intensely fraught print-out this is.89

These alternatives testify to just how off-the-leash the gallery press release has become, and can be among the best things in the show. Generally speaking, these variations imply a confident and knowing author behind them, well-versed in art-world conventions and able to spin off them. If you attempt these options or invent your own, be sure that all involved—artist, gallery—are OK with your novelties. Galleries sometimes have two press releases: one playing it straight, supposedly geared at the press, and a second ‘alternative’ variation—just like the project space adjacent to the traditional museum.

> How to write a short promotional piece

A short promotional text, for a museum brochure or website for example, is a mini-press release, crossed with a mini-news item. Sometimes who/what/where/when details are piled up near the header, to free the text for a basic descriptive understanding of the exhibition or artist’s work.

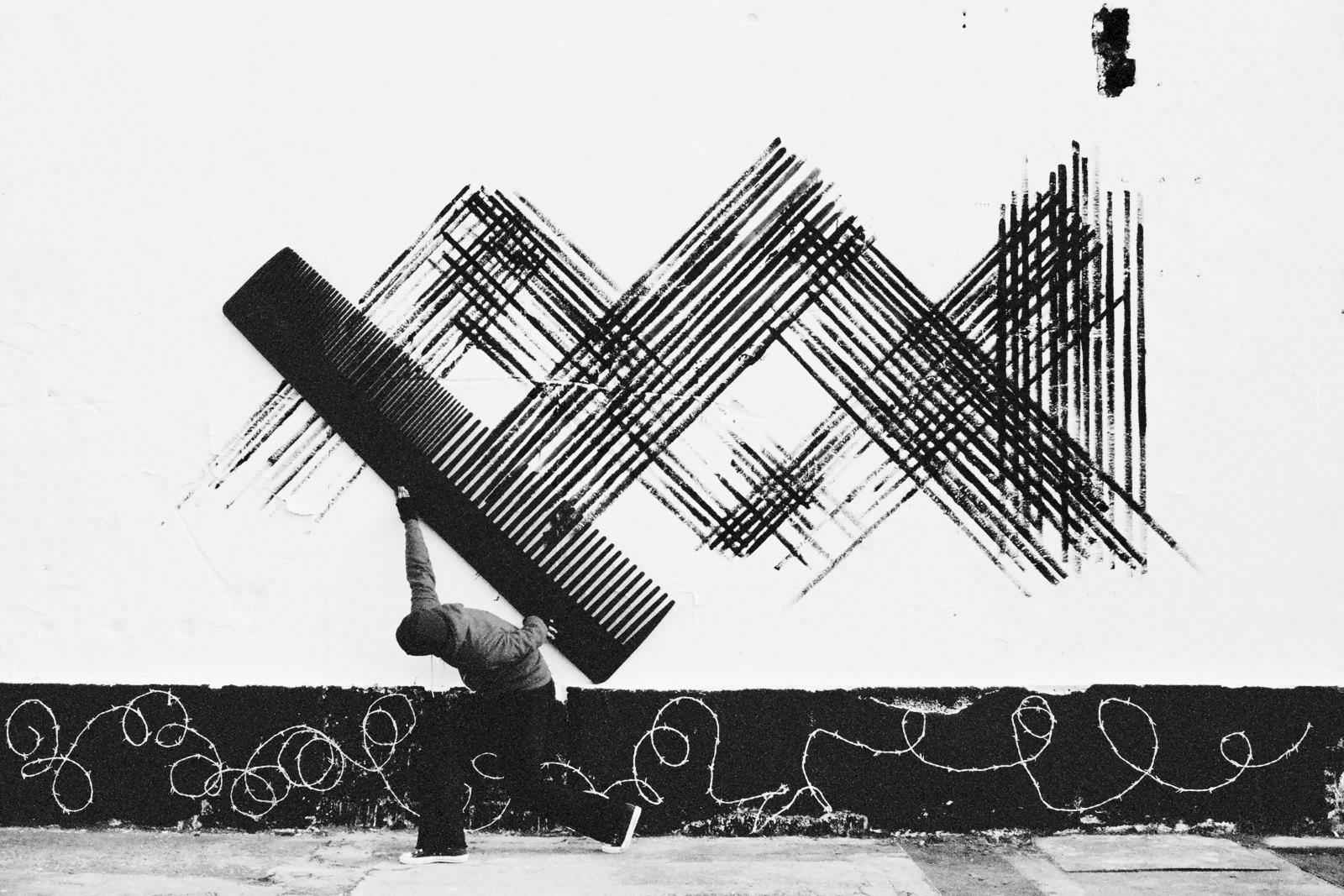

Robin Rhode: The Call of Walls, 17 May 2013—15 Sep 2013. National Gallery of Victoria International, 180 St Kilda Road [1]

Robin Rhode is a South-African artist based in Berlin who works in photography, animation, drawing and performance [2]. ‘The Call of Walls’ is an exhibition of new works [fig. 27] that derive inspiration from the streets and politics of his hometown Johannesburg [3]. Rhode’s witty, engaging and poetic works make reference to hip-hop and graffiti art; to the histories of modernism; and to the act of creative expression itself.

A special exhibition for youth and families will accompany Rhode’s photographs and animations [4]. This unique project extends the artist’s interest in wall drawing and encourages participants to come together to draw and color in an interactive installation [4] of large-scale paste-ups.

Source Text 33 UNSIGNED, ‘Robin Rhode: The Call of Walls’, 2013, National Gallery of Victoria website

fig. 27 ROBIN RHODE, Almanac, 2012–13

This modest 100-word text does not attempt, say, a full-scale analysis of post-apartheid South Africa or a debate on the status of street-art, but sticks to the simple job of explaining:

[1] Who/what/when/where: ‘Robin Rhode: The Call of Walls, 17 May 2013—15 Sep 2013, National Gallery of Victoria International’;

[2] Media (what kind of work?): ‘photography, animation, drawing and performance’;

[3] Key idea: ‘the streets and politics of his hometown Johannesburg’;

[4] What to expect on your visit: you will see ‘photographs and animations’; also, ‘participants [are encouraged] to come together to draw and color in an interactive installation’.

The idea is to entice viewers in straightforward language, hinting at what’s on show and suggesting why a visit is worth their while. You want to convince the art habitué she shouldn’t miss it, but to avoid alienating potential first-time visitors.

> How to write an auction catalogue entry

The auction catalogue blurb is, usually, a classic piece of ‘unsigned’ art-writing. It pulls together dependable technical and numerical details (dimensions; materials; provenance; and more) and authoritative art-historical information to present artworks in their most attractive light for a potential buyer. In sum, such a text aims to establish worth. In terms of this book’s division between art-writing’s two main tasks—‘explaining’ and ‘evaluating’ art—the auction entry is plainly a paradox (see ‘Explaining v. evaluating’). While clearly in the business of selling and attributing value to artworks (literally, a price), the style and content of auction-house texts revolve around ‘straight’, research-based, art-historical explanation:

+ how and when the work was made, exhibited, and received;

+ its place within art history, the broader historical context, and the artist’s own life and career.

With rare exception, the auction house participates solely in the artwork’s secondary market, i.e. the acquisition and sale of work that has been owned previously. The catalogue entries on these works are usually written in-house by trained art historians—auction staff writers, researchers, and experts, possibly with the input of others including the Head of Sales. Their length varies immensely, from

+ lengthy technical information (always impeccably compiled) with no added verbiage;

+ longish caption;

+ medium-sized article;

+ to book-length investment

in proportion to the work’s significance and expected return. Their content may further benefit from the expertise of

+ outside art-historians;

+ artist’s estates;

+ the representative gallery;

+ and, potentially, the artist herself.

The auction catalogue is rarely where new art-historical research will surface. Fanatical accuracy and transparency of sources is imperative. The auction catalogue blurb isn’t just informative art-writing; it represents due diligence, a legal term.

Due diligence: ‘appropriate, sufficient, or proper care and attention, esp. as exercised to avoid committing an offence; a comprehensive appraisal undertaken by or on behalf of a prospective buyer’—OED.

Research must be flawless, with evidence drawn from

+ first-hand expertise of knowledgeable insiders;

+ the catalogue raisonné (if one exists)—the official, comprehensive publication listing of every work (or type of work) by one artist, meticulously compiled;

+ noted publications from a museum, university press, or a recognized dealer in this artist’s career;

+ or the artist’s own verifiable words.

It might be described as a compilation of ‘unassailable’ evidence—if dripping with superlatives. The auction catalogue’s factual data (technical details such as materials and dimensions; exhibition history; literature; sourced quotes from artists or critics) qualify as the firmest historical information, even for academic work, and are carefully ascertained through uncompromising, verifiable research. Forget anything that smacks of theory, academic jargon, or free-flowing commentary that might declare your own personal, interpretative response. However, the auction blurb should not read as a dry encyclopedia listing or academic treatise, but must be fairly lively and engaging, using (attributed) quotes and anecdotes about the artwork’s making, display, or former owner.