Just as the post-Second World War surfeit of resources in affluent nations was initially directed at targets such as eliminating ignorance, but came through time to be focused more on education spending in support of elitism, so the old social evil of want, of poverty, of having too little, was initially the direct target of spending in many postwar states. Additional resources for extra personal expenditure, social security benefits, were initially aimed at the elimination of want, but then, when the worst of want was seen to have been eliminated, public monies, redistribution and state attention moved elsewhere in a way that supported growing exclusion. Tax rates were reduced for the rich, benefit levels tagged to inflation (or less) for the poorest. The income of the rich moved away from that of average earners, who in turn saw their incomes increase faster than those on welfare benefits. The initial compressing (reducing the spread) of income distributions that came with the introduction of social security in many affluent nations, and the taxation needed to fund it, was removed most quickly in those countries which began to choose to become most unequal. High social security spending was not essential for high levels of social inclusion, but low levels of income inequality were. Thus relatively few people would describe themselves as poor and needing to take out loans just to get by in countries as diverse as Japan and the Netherlands, whereas in Britain and the US relative rates of poverty have grown greatly in recent decades, simply because inequality has grown.1

Poverty that mostly results from inequality comes in the form of a new kind of exclusion: exclusion from the lives, the understanding and the caring of others. This is now not through having to live in abject poverty, but through social norms becoming stretched out along such a wide continuum, as most additional income becomes awarded to the most affluent, more of that left to the next most affluent and so on. The elimination of the worst of early 20th-century poverty, coupled with the tales of elitists who believed that those who were poorer were inferior, reduced the power of argument of groups that had previously succeeded in bringing down inequalities in resources between families and classes within many affluent societies. It is slowly becoming clear that growing financial inequality results in large and slowly growing numbers of people being excluded from the norms of society, and creates an expanding and increasingly differentiated social class suffering a new kind of poverty: the new poor, the indebted, the excluded.

The new poor (by various means of counting) now constitute at least a sixth of households in countries like Britain. However, these are very different kinds of households from those who lived through immediate postwar poverty. What the poor mostly had in common by the end of the 20th century were debts they could not easily handle, debts that they could not avoid acquiring and debts that were almost impossible to escape from. Just a short step above the poor in the status hierarchy, fewer and fewer were living average ‘normal’ lives. The numbers of those who had a little wealth had also increased. Above the just-wealthy the numbers who were so well off they could afford to exclude themselves from social norms were hardly growing, although their wealth was growing greatly. This wealth was ultimately derived from such practices as indirectly lending money to the poor at rates of interest many of the poor could never afford to fully repay.

There are many ways of defining a person or household as poor in a rich society. All sensible ways relate to social norms and expectations, but because the expectations as to what it is reasonable to possess have diverged under rising inequality, poverty definitions have become increasingly contentious over time. In the most unequal of large affluent nations, the US, it is very hard to define people as poor as so many have been taught to define ‘the poor’ as those who do not try hard enough not to be poor.2 Similarly, growing elitism has increased support for arguments that blame the poor for their poverty due to their apparent inadequacies, and there has been growing support for turning the definition of the poor into being ‘that group which is unable or unwilling to try hard enough’.

The suggestion that at least a sixth of people live in poverty in some affluent nations results from arguments made in cross-country comparisons which suggest that a robust way of defining people as poor is to say that they are poor if they appear poor on at least two out of three different measures.3 These three measures are: first, do the people concerned (subjectively) describe themselves as poor? Second, do they lack what is needed (necessities) to be included in society as generally understood by people in their country? Third, are they income-poor as commonly understood (low income)? It is currently solely through low income that poverty is officially defined, in Europe in relative terms and within the US in absolute terms. A household can have a low income but not be otherwise poor, as in the case of pensioners who have accrued savings that they can draw on. Similarly a household can have an income over the poverty threshold but be unable to afford to pay for the things seen as essential by most people, such as a holiday for themselves and their children once a year, or Christmas presents or a birthday party, the kind of presents and party that will not show them up. A family that cannot afford such things is likely to be expenditure- (or necessities-)poor and very likely to feel subjectively poor even if just above the official income poverty line.

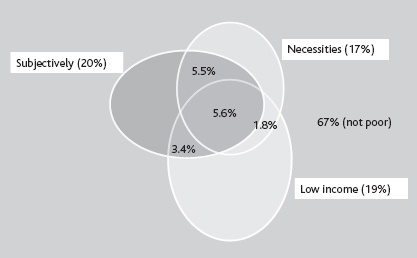

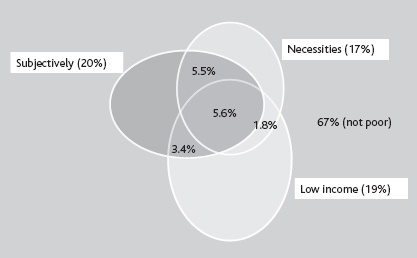

In Britain around 5.6% of households appear poor on all three measures (subjectively, by expenditure and by income), some 16.3% on all three or any two (see Figure 6). It should be clear that any household, person or family which is poor on at least two of these criteria is likely to be excluded from the norms of society in some significant way, hence a sixth is a safe lower band to quote when asked how many people are truly poor. Figure 6 shows how that sixth was constituted in Britain at the turn of the millennium.

In other similarly unequal affluent countries that proportion would be higher or lower and made up of differing combinations of the three constituent groups, but it would not be dissimilar. It changes year on year in all countries and varies for different groups in the population, reducing a little for families with children in Britain in the early years of the 21st century through tax credits, but then increasing greatly for all groups as the economic crash is met with policies resulting in widening differentials, felt (subjectively) in what people can get (necessities becoming harder to acquire), and in what they are given (lower real income).

Note: The sixth who are poor on at least two criteria are shown in the areas with percentages labelled in them (5.5%+3.4%+1.8%+5.6%=16.3%, and 67%=100%–16%–6%–4%–7%).

Source: Drawn from figures given in table 6 of the original study: Bradshaw, J. and Finch, N. (2003) ‘Overlaps in dimensions of poverty’, Journal of Social Policy, vol 32, no 4, pp 513-25.

In Britain, by the start of the 21st century almost as many households were poor because they lacked the necessities required to be socially included and because their constituent members knew they were poor (5.5%), as were poor because they fell into all three poverty categories (5.6%). When the population was surveyed as to what items were necessities and what were luxuries, the two key essential expenditures that the current poverty line pivoted on were, first, an ability to make small savings each month (£10 in the case of Britain); and, second, to be able have an annual holiday away from home and the wider family. These were the two items that a majority of people in Britain thought others should, as a minimum, be able to afford and which the largest numbers could not afford.4

The injustice of social exclusion had, by the 21st century, debt at its heart in place of the joblessness, destitution and old age that were the key drivers of ‘want’ when today’s pensioners were born. It is now debt that prevents most poor people from being able to afford necessities – you cannot save each month if you have debts to pay off and holidays are affordable to almost anyone except those with too much unsecured debt. As debt grew in importance over time, the link between low income and low expenditure on necessities weakened slightly, with the smallest overlap in Figure 6 being between those two poverty measures. This is because low income does not initially prevent the purchase of necessities if there is access to debt.

In countries where inequality is higher, debts are accrued to pay for holidays, and to allow the newly income-poor, those who lose their jobs, divorce or see their spouse die, to be (for a little while at least) less expenditure-poor. The effect in Britain of the increased necessity of falling back on debt and of keeping up appearances, in what has become one of the most unequal countries in Western Europe, was that half of the mountain of all credit card debt in all of Western Europe was held solely by British citizens by 2006.5 A not insignificant proportion of that debt had been amassed to finance going on holiday. People were taking holidays more than ever before, because in Britain being able to take a holiday had become the marker of social acceptability, just as being able to wear a suit to church had been in a previous era, and just as being able to afford to run a car if you had children became a social norm not long after that. In the US another significant purchase, a second car for a family of four or more, serves the same purpose of establishing yourself as someone currently coping rather than not. It is not the object itself, but what it signifies and makes possible that matters. The US built suburbs without pavements. The UK built up the idea that those who worked hard would be rewarded with holidays. Tony Blair used to take his very publicly, alongside (Sir) Cliff Richard, the man who made millions singing about holidays in 1963 at a time when most people could neither afford an annual holiday nor choose to borrow to take one.6

Holidays matter now in most rich countries because they have become such a clear marker separating those who are just getting by from those who are doing all right from those who are doing well or very well. ‘Where did you go on holiday?’ is now an extremely intimate question to ask of another adult; the answers divide parents picking up children from school into groups; they divide work colleagues into camps; they divide pensioners by their employment history as it is that history that determines their pensions and hence their holidays.

Rest days and Sabbath days, festive seasons and taboos on working at certain times have all been built into human cultures to ensure that we take holidays. Relaxation is vital, but today’s holidays are often not greatly satisfying, family holidays having the most minor of net effects on reported subjective happiness compared with almost anything else that occurs of significance in people’s lives.7 Perhaps it was always thus, but it is hard to believe that those who first won the right to an annual holiday did not usually greatly enjoy that time off.

In an age where holidays are common people mostly take holidays because other people take holidays. It has become an expectation, and as a result holiday making in affluent countries is remarkably similar within each country as compared to between countries. Most people in Japan take only a few days’ holiday a year, but household working weeks and working lives are not excessively long. In contrast, the two-week ‘summer holiday’ and one-week ‘winter break’ have become standard in parts of Europe. In contrast again, only minimal holidays are common in the US where holiday pay is still rare. Everyone needs a rest, but whether that rest comes in the form of an annual holiday depends on when and where you are. Holidays became the marker of social inclusion in affluent European societies by the start of the current century because they were the marginal item in virtual shopping baskets, that commodity which could be afforded if there was money to spare, but which had to be forgone in hard times.

In any society with even the slightest surplus there is always a marginal commodity. It has been through observing behaviour historically in relation to those marginal commodities that the unwritten rules of societies were initially unravelled. The necessity of having furniture, televisions, cars and holidays came long after it was observed that workers needed good quality shirts and shoes (recognised in 1759), that in order to have self-respect they should not to have to live in a ‘hovel’ (observed by 1847), and that it was not unreasonable to ask to be able to afford a postage stamp (at least by 1901).8 Mill-loom woven shirts, brick-built terraced houses, postage stamps, all became necessities less than a lifetime after the mass production of looms and large-scale brick making and the introduction of the Penny Post in Britain and equivalents in many similar countries. Within just one more lifetime, the mechanisation of looms, automation of brick making and (partly) of letter sorting had made shirts, brick-built homes and postage stamps parts of life that all could enjoy, no longer marginal items that the poor had to go without. Slowly a pattern was emerging.

Towards the end of the Second World War it was becoming clear to those studying (male-dominated) society that the ‘… outstanding discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships. He does not act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the possession of material goods; he acts so as to safeguard his social standing, his social claims, his social assets’.9 However, what was far from clear in 1944 was in what ways, as men’s (and then women’s) individual interests in material goods, their basic needs, were better met, would people need to act differently to maintain their social standing. Pecking orders and rank do not simply disappear in an abundance of goods. For men, social standing had largely been secured through earning enough to safeguard their family, enough to be able to afford to put a good shirt on their own back, enough to feel they were not living in a hovel. Occasionally a man might have spent the excess on trinkets such as a postage stamp for a letter to a lover, and much more often beer, the poorest of men and women drinking themselves to death on gin. However, from the 1960s onwards those times began to fade in memory, as mass consumption followed mass production.

Mass consumption often consists of what appear to be trinkets and trivia, of more clothes than people possibly need, no longer one good linen shirt, or of more shoes than can easily be stored, no longer just one good pair, of houses with more rooms than can easily be kept clean, and in place of that postage stamp, junk mail. However, trinkets, trivia and fecklessness only appear as such to those not over-purchasing or over-consuming. From the trading of shells in ancient Polynesian societies, to curvier cars in 1950s America, we have long purchased with our social status foremost in mind.

Trinkets have always held great social importance and mechanisation did not decrease this. Mass-produced trinkets, such as jewellery in place of shells, and production-line cars, and their purchasing, wearing and driving, soon came to no longer signify high standing; that requires scarcity. Mass-produced goods soon become necessities, and after that are simply taken for granted. In Europe in 1950 to be without a car was normal; 50 years later it is a marker of poverty. In Europe in 1950 most people did not take a holiday; 50 years later not taking a holiday has become a marker of poverty (and holidays can now easily cost more than second-hand cars).

Most of the increase in debt that has occurred since the 1950s has been accrued by people in work. Of those debts not secured on property (mortgages), most have been accrued by people in low-paid work. Work alone no longer confers enough status and respect, not if it is poorly paid. People working on poverty wages (in Europe three fifths of national median wages) tend to be most commonly employed in the private sector, then in the voluntary sector, and most rarely in the state sector.10 The private sector pays higher (on arithmetical but not median average) because those in charge of themselves with little accountability to others tend to pay themselves very well, and by doing so reinforce the idea that the more valuable a person you are the more money you should have. The state sector pays its managers less because there is a little more self-control levied when accountability is greater. In the absence of accountability people in the state sector are just as capable of transgressing, as state-employed members of the UK Parliament illustrated when many of their actions were revealed in the expenses scandal of 2008/09. What they bought with those expenses illustrated what they had come to see as acceptable purchases in an age of high and rising inequality. The voluntary sector is a mix of these two extremes. God or the charity commissioners might be omnipresent in theory, but in practice he/she/they are not spending government money. In all sectors if you find yourself at the bottom of each pyramid, and the pyramids are being elongated upwards (to slowly look more like upside-down parsnips than ancient tombs), to then value your intrinsic self when others are so materialistic requires either great and unusual tenacity, or borrowing just a little extra money to supplement your pay. You borrow it to buy things which others like you have because ‘you’re worth it’, and you want to believe you are like them, not inferior to them.

If you have been led to believe that a valuable person is a well-paid person then it becomes especially important to accrue debt when your income is falling in order to maintain your self-esteem, to avert what even hard-nosed economists from Adam Smith onwards have identified as the mortifying effect of social downgrading.11 People spend and get into debt to maintain their social position, not out of envy of the rich, but out of the necessity to maintain self-respect.12 Social downgrading has a physical effect on human bodies, akin to the feeling of being sick to the depths of your stomach as you make a fool of yourself in public. Humans are conditioned, and have almost certainly evolved, to fit in, to be social animals, to feel pain, concern and anxiety which prevents them from acting in ways likely to lead to their being ostracised by their small social group. We have recently come to realise that it is not just our own social pain that we feel, but through possessing ‘mirror neurons’ we physically feel the pain of others as our empathetic brain appears to be ‘… automatic and embedded’.13

We now know some of the physical reasons why most of us react instantly to others’ hurt, social hurt as well as physical. If you see someone hit on the head you wince. If you see someone shamed, you too feel their shame physically. If social standing is linked to financial reward it becomes necessary to accrue and to spend more and more in order to stay still. The alternative, of not seeing financial reward as reflecting social standing, is a modern-day heresy. It is possible to be a heretic, to not play the game, to not consume so much, to not be so concerned with material goods, but it is not easy. If it were easy to be a heretic there would be far more heretics; they would form a new religion and we would no longer recognise them as heretics. To reject contemporary materialism you would have to give others (including children) presents only in the quantities that your grandparents were given, own as many clothes as they did, quantities which were adequate when two could share one wardrobe; you are no heretic if you simply consume a little less than others currently around you and recycle a little more. It is partly because we consume so much more than our grandparents that we get in such debt.

For some, the alternative to getting into debt is not to take a holiday. At the height of the worldwide economic boom in 2001, in one of the richest cities on the planet, one child in every five in London had no annual holiday because their parents could not afford one.14 Very few of the parents of those children will have chosen for their child not to have had a holiday that year because they saw package holidays as a con, or hiring a caravan for a week as an unnecessary luxury. Of the children being looked after by a single parent in London the same survey of recreational norms showed that most had no annual holiday, and that 44% of those single parent-headed families could not afford other things commonly assumed to be essentials, such as household insurance. If holidays are now seen as essential, household insurance is hardly an extravagance. Nationally only 8% of households are uninsured.15 Insurance makes it possible to replace the material goods amassed over a lifetime, goods you could mostly live without physically, but not socially. It is the families of the poorest of children who are most likely to suffer from theft and the aftermath of theft, or fire or flooding because they more often live where burglary is more common, where house fires are more likely, and where homes are cheaper because they are built lower down the hill where they are at greater risk of flooding. So, for them, avoiding paying insurance is not a sensible saving.

While a few people get very rich running the firms that sell insurance, that does not mean it is sensible to avoid insurance altogether. The less you have to start with the more you may need what you do have. If you are not insured then the only way to cope with insurable events may be to get further into debt. It is often shocks such as these that plunge families into long-lasting debt, but rising debt is a product of rising lending. And all this is as true internationally as it is in the homes of the London poor.

Just as there is money to be made out of the poor who live in the shadows of Canary Wharf and Manhattan by those working in finance, as long as many are ripped off just a little, so too, but on a far greater scale, is there money to be made from the poor abroad. Commentators from rich countries, especially national leaders, often boast about various aspects of the roughly US$100 billion a year which their countries donate as aid (or spend on debt write-offs) for people in poor countries. They rarely comment on how, for every one of those dollars another 10 flow in the opposite direction, siphoned out of poor countries, mainly by traders who buy cheap and sell dear. The estimates that have been made16 suggest that major corporations are responsible for the majority of the trillion-dollar-a-year flow of illicit funds to rich nations using webs of financial trusts, nominee bank accounts, numerous methods to avoid tax and simple mispricing. The firms most prominently featuring in many accounts are oil, commodity and mining firms. Traditional bribery and corruption within poor countries accounts for only 3% of this sum. Despite this, when corruption is considered it is almost always that kind of corruption and not the other 97%, the corruption of very rich Western bankers and businessmen (and a handful of businesswomen) that is being thought of. This corruption is orchestrated from places such as those gleaming financial towers of London’s banking centre, from New York, and from a plethora of well-connected tax havens.

Between 1981 and 2001 only 1.3% of worldwide growth in income was in some way directed towards reducing the dollar-a-day poverty that the poorest billion live with. In contrast, a majority of all the global growth in income during the 1990s was secured by the richest 10% of the planet’s population.17 Most of that growth in income was growth in the value of the stocks and shares which were traded by people like those immoral bankers. However, for the richest in the world the returns from these were not enough, and they invested millions at a time in hedge funds run by yet more private bankers who worked in less obvious edifices than skyscrapers. It is the monies that these people hold which have come to give them a right, they say, to ‘earn’ more money. Ultimately those extra monies have to come from somewhere and so are conjured up from others as debt ‘interest’ (as more is lent). The richer the rich become, the greater the debt of others, both worldwide and in the shadows of the bankers’ own homes. In Chapter 6, Table 6 (page 231) documents the many trillions of dollars of debt amassed in the US from 1977 to 2008, but to concentrate on it here takes this story on a little too far.

Before looking at where we are now, and to try to find a way out, it is always helpful to look at how we got here. To be rich is to be able to call on the labour and goods of others, and to be able to pass on those rights to your children, in theory in perpetuity. The justification of such a bizarre arrangement requires equally bizarre theories. Traditionally, rich monarchs, abbots of monasteries and Medici-type bankers (and merchants) believed it was God’s will that they should have wealth and others be poor. As monarchies crumbled and monasteries were razed, it became clear that many more families could become mini Medicis. That they all did so as the will of God became a less convincing theory, although we did create Protestantism, partly to justify the making of riches on earth. More effectively, instead of transforming religions that preached piety in order to celebrate greed, those who felt the need to justify inequality turned to science (once seen as heresy, science is often now described as the new religion of our times). More specifically, those searching to find new stories to justify inequality turned to the new political and economic science of the Enlightenment,18 then to emerging natural sciences, in particular to biology, and finally to new forms of mathematics itself.

If most people in affluent nations believed that all human beings were alike, then it would not be possible under affluent conditions to justify the exclusion of so many from so many social norms. The majority would find it abhorrent that a large minority should be allowed to live in poverty if they saw that minority as the same sort of people as themselves. And the majority would be appalled that above them a much smaller minority should be allowed to exclude themselves through their wealth. It is only because the majority of people in many affluent societies have come to be taught (and to believe) that a few are especially able, and others particularly undeserving, that current inequalities can be maintained. Inequalities cannot be reduced while enough people (falsely) believe that inequalities are natural, and a few even that inequalities are beneficial.

It was only in the course of the last century that theories of inherent differences among the whole population became widespread. Before then it was largely believed that the gods ordained only the chosen few to be inherently different, those who should be favoured, the monarchs and the priests. In those times there were simply not enough resources for the vast majority to live anything other than a life of frequent want. It was only when more widespread inequalities in income and wealth began to grow under 19th-century industrialisation that theories (stories) attempting to justify these new inequalities as natural were widely propagated. Out of evolutionary theory came the idea that there were a few great families which passed on superior abilities to their offspring and, in contrast, a residuum of inferior but similarly interbreeding humans who were much greater in number.19 Often these people, the residuum, came to rely on various poor laws for their survival and were labelled ‘paupers’. Between these two extremes was the mass of humanity in the newly industrialising countries, people labelled as capable of hard working but incapable of great thinking.

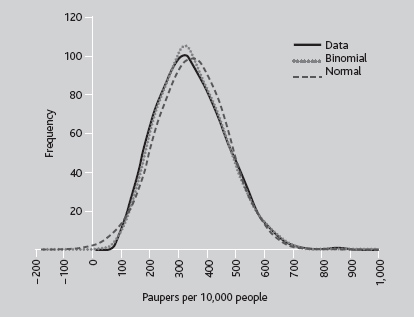

Scientific diagrams were produced to support these early geneticist beliefs. One, redrawn here as Figure 7, purports to show that the 1891 geographical distribution of recorded paupers in England and Wales followed a natural pattern, a result, it was presumed, of breeding. These paupers were people recorded as receiving what was called ‘outdoor relief’, the most basic of poverty relief which did not force the recipient to enter a workhouse. Such relief ranged in prevalence between geographical areas from about 0.5% of the population, to highs of around 8.5% (not at all unlike the variation in the rates of people claiming unemployment benefits in those two countries a century later). The figure also shows two statistical curves plotted on the original diagram by its original author, Karl Pearson, to try to fit the data best. These were the point binomial and normal (bell curve) distributions. The reason the curves were fitted was to further the attempt to imply that variation in numbers of paupers between areas followed some kind of ‘natural’ distribution. The normal distribution was around this time first being assumed to describe the distribution of intelligence. Hereditary thinking would have it that some areas had more paupers because more genetically inferior people had come to cluster there and had interbred; other areas were spared such pauperisation presumably due to the inherent superiority of the local populace, through the driving away of paupers or through their ‘extinction’ via the workhouse or starvation. The close fit of the two curves to the actual data was implicitly being put forward as proof that there was an underlying natural process determining the numbers identified as being in this separate (implicitly sub-human) group. This was apparently revealed to be so when all the subjects were separated into some 632 poor law union areas and the paupers’ proportions calculated. The graph was published in 1895.

Figure 7 is important because it is a reproduction of one of the first attempts to use a graph to apply a statistical description to groups of people and to demonstrate to others that the outcome, what is observed, reflects a process that cannot be seen without that graph but which must be happening to result in such a distribution. Millions of similar bell curves have been drawn since of supposed human variation in ability. The apparent smoothness of the data curve and closeness of the fit is the key to the implication and strength of the claim that some natural law is being uncovered. At the time the distribution in Figure 7 was drawn, the Gaussian (or Laplacian) statistical distribution being applied to a probability was well known among scientists, but the idea of it being seen as biologically normal was less than a couple of decades old.20 It was very shortly after this that the Gaussian/Laplacian (bell-shaped) distribution came to be described as somehow ‘natural’, as ‘normal’. Just at the time, in fact, that it came to be used to describe people.

Note: Y-axis: frequency of unions reporting each rate, or modelled rates predicted under the binomial or normal distributions.

Source: Data reproduced in Table 4, page 108 below. Figure redrawn from the original (Pearson, K (1895) ‘Contributions to the mathematical theory of evolution – II. Skew variation in homogeneous material’, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical, vol 186, pp 343-414, Figure 17, plate 13)

When it comes to categorising human ability, the process by which a distribution comes to take on the appearance of a bell-shaped curve is far more likely to reflect the forces acting on those who count than those who are counted. Nowadays people who enjoy setting tests are taught to set them in such a way that the distribution of marks that students receive tends to form just such a shape.21 It is always possible to set tests that form very different shapes, such as for quiz shows where the prize money doubles with each correct answer and the questions become progressively much harder, but if you want to suggest that your students are distributed by ability along a normal curve then you can easily set a test that shows this curve, or any other curve you fancy. For instance, if you want to suggest that almost none of your students are lazy, almost all are especially able, then you do not subdivide second degree classes in your university. It is also important to remember that random social processes, such as noting in which areas more winning lottery tickets are sold, having taken into account the numbers sold, will reflect a normal distribution if there are enough winners. Thus, if the marking of university degrees was largely a random process, we would expect a normal distribution to emerge. What is interesting is the occasion when the data fit so closely to such a distribution that it is unlikely that such a good fit would have happened by chance. This is what Figure 7 suggests.

In 1891 there was great pressure on poor law unions not to give too much ‘relief’. Unemployment, a new term of the time, had hit different areas with different effects. Different places had had bad harvests; different industries had been differently hurt by the recession of the late 1880s; poor law union officials did not want to look out of line and tried to curtail their spending, so no surprising outliers were found; almost every district had a workhouse and some monies for outdoor relief (not requiring institutionalisation) so that a small number would always be provided for. Almost the very last people to have an individual impact on the shape of the distribution were the paupers themselves, but just as it is not the unemployed today who choose to be unemployed, or who carry some inherited propensity to unemployment, the paupers of yesterday had little say over what was said about them or whether they became paupers.

Today we largely recognise that in rich countries unemployment is mostly the product of being born at the wrong time in the wrong place and can strike us all, although with greatly varying probabilities depending on our precise circumstances,22 but we live in danger of forgetting this and of reverting to the late 19th-century thinking of eugenics, the ‘science’ of drawing (what are either explicitly or implicitly claimed as) ability distributions from outcome events, of which Figure 7 is the world’s first ever geographical example.

Like today’s unemployed, the paupers of 1891 did have a small role to play in their distribution as many moved around the country. With little support people tend not to stay for long in a place with no work if they can help it, and so move towards jobs. Outdoor relief was supposed to be available only to local people, in order to reduce such migrations, but if there was a single process whereby the actions of individuals were helping to form the shape of the curve it was through their get-up-and-go, not their recidivism. However, it was recidivism for which the drawer of the curves was looking.

It would prove very little were the statistical curves in Figure 7 found to be good fits to the data. But it is an interesting exercise to test the degree to which the data and the two statistical curves are similar. There are many ways of testing the likelihood of data following a particular statistical distribution. One of the oldest is called Pearson’s goodness-of-fit test.23 It is named after the same man, Karl Pearson, who drew the graph and so it is appropriate to use his own test in order to test the assertion he was implicitly making in drawing these curves. The data behind the curves and the details of the working out of the probabilities are all given in Table 4. What is revealed is intriguing.

The normal curve as drawn by Karl Pearson appears to fit the data very closely. It departs from the data most obviously as it suggests that a few areas should have pauperisation rates of less than 0% and consequently its peak is a little lower than that of the other fitted distribution, or of the data. Normal curves stretch from minus infinity to infinity, suggesting (if intelligence really was distributed according to such curves) that among us all is both one supremely intelligent being and once supremely stupid individual with a negative IQ. Negative intelligence is as silly an idea as a negative pauper rate so it is odd that Pearson drew that line on his graph. However, it is not the slight practical problems of fitting the data to that supposedly normal distribution that is intriguing. What is intriguing is just how well the binomial distribution fits the data. The fit is not just close; it is almost unbelievably close. In the language of probabilities it is sensible to never say never, but the chances that the pauper data distribution as drawn in Figure 7 did derive from a process that follows a binomial distribution is quite unlikely. Why? Because the fit is too close, too good, far too good to be true.

Pearson’s goodness-of-fit test is usually used to test whether a set of data points are distributed closely enough to an expected distribution, a statistical distribution, for it to be plausible to be able to claim that they were drawn from just such a distribution. An early example of its use was in the discovery of genetics in determining the outcome of crossing different strains of peas. It was posited that the interbreeding of certain peas would produce a certain ratio of peas resulting in one example of one strain to every three of another strain, this just resulting from the crossing of two strains. Eachpairing produced a strain by chance, but over time those particular pairings asymptotically resulted in that 1:3 ratio of outcome. It took a long time to arrange for pairs of peas to pair correctly (about the same time as with rabbits), and so a test was needed to be able to say with some confidence that, having recorded several dozen or hundred pairings, the pea offspring were following that 1:3 outcome distribution. This is a ‘goodness-of-fit’ test.

| Paupers (P) | Normal (N) | Binomial (B) | Data (D) | B–D | (B–D)² | (B–D)²/B |

| –200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| –150 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| –100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| –50 | 2 | 0 | 0 |  |

||

| 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 50 | 10 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 100 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 1 | 0.043 | |

| 150 | 37 | 44 | 47 | 9 | 0.205 | |

| 200 | 63 | 73 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 250 | 83 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 300 | 97 | 105 | 100 | 5 | 25 | 0.238 |

| 350 | 97 | 92 | 90 | 2 | 4 | 0.043 |

| 400 | 83 | 75 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 450 | 63 | 55 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 500 | 37 | 36 | 40 | –4 | 16 | 0.444 |

| 550 | 21 | 20 | 21 | –1 | 1 | 0.050 |

| 600 | 10 | 12 | 11 |  |

1 | 0.083 |

| 650 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0.143 | |

| 700 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 750 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 850 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 900 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 950 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 632 | 632 | 632 | 1.25 |

Notes: For source of data see Figure 7. Both data and fitted curves were read off the original graph.

Columns: D is the number of poor law union areas recording a given number of paupers per 10,000 people (P). The Normal (N) and Binomial (B) are the two possible expected distributions as drawn on Karl Pearson’s original diagram along with the data. Cells are amalgamated (*) with expected values of 5 or less (marked by two curly brackets) resulting in 12 categories. The difference between expected and observed (B–D) is calculated, squared, divided by expected (B) and summed. The sum (1.25) is less than the 0.995 probability value (1.735) on a chi-squared distribution with 9 degrees of freedom (12–2 estimated parameters and less another 1 degree given a fixed n of 632 union areas). The probability that the data were drawn at random from the binomial distribution is less than 0.5%; the fit using Pearson’s own test is probably (with a more than 99.5% probability) too good to be true.

The goodness-of-fit test provides an estimate of the chances that a particular outcome could result if the underlying distribution were, say, 1:3, but as it can be (what is called) a two-tailed test, it can thus also provide an estimate that the fit is too good to be true. If a geneticist told you that they had crossed 1,000 pairs of peas, and those crosses had resulted in exactly 750 peas of one strain and 250 peas of another strain, the chances are more likely that they are lying about their data than that they actually conducted such an experiment and this was the result. To determine the probability that they were lying, the Pearson goodness-of-fit test, when two-tailed, in effect provides a test of that honesty.

The binomial distribution fits the data shown in Figure 7 so well that the probability that a fit at random would be this good if another set of data were derived from the distribution is less than 0.5%. The usual cut-off used to begin to doubt the plausibility of a fit is 2.5%. This is because, in a two-tailed test, a 95% chance that the data could have arisen from the distribution has been deemed a good level to use, again since around the time of Karl Pearson. In the notes to Table 4 (above) more details are given of applying Pearson’s test to his data, and it is of course entirely possible (although unlikely) that results as close fitting as this could have been drawn from the binomial distribution.24

Am I boring you? It may well be good news if I am. A propensity to find statistics and mathematical probabilities fascinating is not necessarily a sign of a well-rounded individual (see Section 3.2 above), although it is possible to be a well-rounded individual and have a fascination with numbers and sequences that goes beyond normal bounds. It is possible, but an unusually high number of those who find pattern spotting in abstract spaces not to be very difficult have generally found understanding people to be extremely tricky. When reading others’ accounts of him it does cross your mind that one of these people might have been Karl Pearson.25 It is possible that Pearson’s thoughts about people led him, perhaps unconsciously, to draw those two curves, the data to the distribution, so closely together on that graph paper so many years ago. It is possible that the fit is true and the commissioners of the poor law unions arranged for the relief to be distributed geographically according to the binomial distribution. But even if most poor law authorities were following the herd in the amount of relief they offered, a few were more generous than most and a few more constrained; the fit should not, if there is also an element of random variation, be that close to the binomial curve. Either they, or Pearson, or both, could have been labouring under the belief popular at the time: that the poor were a curse and were in danger of over-breeding. It is when such beliefs become articles of faith that graphs are drawn with curves that fit as closely and as improbably as Figure 7 suggests. It is when people become convinced that they know a great truth, the underpinnings of what might soon almost become a new religion, that the normal questioning and conventions are abandoned.

Just seven years after drawing his curves of the geography of paupers, Karl Pearson, who came to be seen as one of the founders of the science of eugenics, proclaimed (in 1902) that his belief would prevail and become widespread ‘twenty years hence’.26 He was right in that at least. Eugenics had become almost a religion by the 1920s, it being an article of faith that some were more able than others and that those differences were strongly influenced by some form of inherited acumen. It was not just among the earlier lovers of the new science of statistics that this religion took hold. These ideas were particularly attractive to male mathematicians, natural scientists and, among social scientists, to economists27 (see Section 6.2 for how orthodox economics and eugenics are so closely related). It really was almost as if there was an innate predisposition to be attracted to eugenists’ ideas among those men who found numbers easy but empathising with others a little more difficult. The chance of men being likely to find such communication difficult is four to five times higher than that of women,28 although there were several key women in the early eugenics movement, when it was still not clear what folly it was. However, the dominance of men among those few who still argue for eugenics today is intriguing. Is it their nature, or their nurture, that leads men more often to such folly?

Women who knew him wrote that Pearson found women tricky. He was far from alone among Victorian men in either this or in believing in eugenics, but there were a few prominent people who offered different views who were not so much products of their time. For instance, although not all early feminists spoke with one voice, the fledging women’s movement did argue against eugenicist ideas and specifically Karl Pearson’s suggestion that women’s primary function was reproduction of the ‘race’, and that women who resisted his arguments were asexual, in search of an equality with men that was not possible, and that such women were ‘… a temporary aberration in the race’.29

In the years prior to the First World War the myth was first spread that progress for the specific ‘races’ (mythical races such as the British race, the Aryan or the Nordic race) relied on the identification and empowering of men ‘… of exceptional talent from the mass … the mass is, almost invariably, feminized’.30 If geneticist thinking saw races as fundamentally different, sexes were even more riven apart by biological determinist theories of gender difference.31

It was partly the immediate reaction of horror to the genocide of the Second World War, but also the experience of working together as a nation in that war, and the later realisation that generation and environment mattered so much more than all else over how well children performed in tests that led to eugenics later being shunned. Hitler’s preference for eugenics helped in this. Ideas such as universal health services being made available on an equal basis to all arose as practical possibilities because of this32 and arose out of that wartime experience which had the unforeseen result of a much wider acceptance of the idea that all people in one country at least were of equal value. It would appear that even mild eugenicists, such as William Beveridge in Britain, exorcised their policy recommendations of eugenicist thinking as they became aware of the genocide being perpetrated early on during the war. And so, in the aftermath of genocide, at the heights of postwar anti-communism, eugenics floundered. Its means and ends were too illiberal. As a result, eugenics as denial of freedom became linked then with fascism and that kept its popularity down.

By the time of the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, eugenics had to be practised in secret as it had become associated with the totalitarianism of communists as well as fascists. At that time the idea’s dwindling supporters used the term ‘crypto-eugenics’33 among themselves largely in secret. By the mid-1970s it was acknowledged that not a single reputable scientific study had been undertaken that suggested with any authority that inheritable intelligence existed.34 By the early 1980s those few eugenists still out in the open were easy targets for ridicule.35 And, while taught how to use his tests, university undergraduates studying statistics were taught nothing of Pearson’s past and the murky origins of his subject of study. That eugenic past was being forgotten.

In the latter half of the 20th century, partly in reaction to the achievement of greater equalities, and as the passing of time resulted in forgetting the social miseries of 1920s inequality, the economic despair of 1930s depression, the moral outrage of 1940s atrocity and 1950s social contracts to counter communism, growing inequalities were again foisted on populations, and attempts at trying to justify social inequalities crept out of the shadows. At the forefront of the resurgence of the ‘eugenic-like’ argument was the oft-criticised, simultaneously both dreary and revolting literature on supposedly innate racial differences, literature which so clearly ‘… compound[s] folly with malice’.36 But in the background was more subtle writing, driven by a little less overt malice, by men put in positions of power trying to justify the pedestals they stood on. A few examples follow. In those justifications they reached back to that early mixing of genetic theory and human social distribution. And so the too-goodto-be-true fit of two curves drawn by hand and reproduced in the few surviving copies of a dusty old journal of 1895 still matter. The first curves matter because the documents they appear in betray the follies in the founding tenets of geneticism. They matter because the greatest danger is to forget.

Contemporary work on epigenetics explicitly steers away from saying genetic make-up determines the social destiny of humans along an ability continuum.37 In contrast, geneticism is the current version of the belief that not only do people differ in their inherent abilities, but that our ‘ability’ (and other psychological differences) is to a large part inherited from our parents. This belief is now again widely held among many of those who advise some of the most powerful governments of the world in the early years of the current century. Eugenism has arisen again 110 years after Figure 7 was drawn, but now goes by a different name and appears in a new form. It is now hiding behind a vastly more complex biological cloak. For example, David Miller, one University of Oxford-based educator among the advisers of the notionally left-wing New Labour government in Britain, suggested (in a book supposed to be concerned with ‘fairness’) that ‘… there is a significant correlation between the measured intelligence of parents and their children.… Equality of opportunity does not aim to defeat biology, but to ensure equal chances for those with similar ability and motivation’.38

Intelligence is not like wealth. Wealth is mostly passed on rather than amassed. Wealth is inherited. Intelligence, in contrast, is held in common. Intelligence, the capacity to acquire and apply knowledge, is not an individual attribute that people are born with, but rather it is built through learning. No single individual has the capacity to read more than a miniscule fraction of the books in a modern library, and no single individual has the capacity to acquire and apply much more than a tiny fraction of what humans have collectively come to understand. We act and behave as if there are a few great men with encyclopaedic minds able to comprehend the cosmos; we assume that most of us are of lower intelligence and we presume that many humans are of much lower ability than us.

In truth the great men are just as fallible as the lower orders; there are no discernible innate differences in people’s capacity to learn. Learning for all is far from easy, which is why it is so easy for some educators to confuse a high correlation between test results of parents and their offspring with evidence of inherited biological limits. It is as wrong to confuse that as it was wrong to believe that there was some special meaning to the fact that the geographical pattern in pauper statistics of 1891 appeared to form a curve when computed in a particular way, ignoring the probable enthusiasm that resulted in a too-good-to-be-true depiction. Human beings cannot be divided into groups with similar inherent abilities and motivations; there is no biological distinction between those destined to be paupers and those set to rule them.39

There is a correlation between the geography of those today who make hereditarian claims and their propensity to reveal their beliefs. Today’s hereditarians appear to come disproportionately from elite institutions. In Britain the elite university for the humanities is located in Oxford. To give a second example, a former head of Britain’s Economic and Social Research Council, Gordon Marshall, and his colleagues suggested that there was the possibility ‘… that children born to working-class parents simply have less natural ability than those born to higher-class parents’.40 In saying that the possibility of an inherited ‘natural ability’ process was at work these academics were only parroting what is commonly believed in such places, oft repeated by colleagues from the same college as the lead author. For instance, here is a third example, from yet another University of Oxford professor, John Goldthorpe, who claims that: ‘children of different class backgrounds tend to do better or worse in school – on account, one may suppose, of a complex interplay of sociocultural and genetic factors’.41 It would be a dreary exercise to trawl through the works of many more contemporary academics at the very pinnacles of the career ladders in countries like Britain and in places like Oxford to draw yet more examples of what ‘one may suppose’. While these are only examples drawn from a small group, all three of the professors quoted had access to the ears of government ministers and even prime ministers. Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister during the time they were writing, had clearly come to believe in a geneticism of the kind they promoted, as revealed in his speeches.42 He is unlikely to have formed such beliefs as a child. Whether he came to his views while he was studying at university as an undergraduate, or later through the influence of advisers, who were in turn influenced by academics (similar to these three), is unclear. What is clear is that by the 1990s geneticism was being widely discussed in circles of power. Should you wish to search for further examples there is now a literature that suggests we should link theories on behavioural genetics with public policy.43 Rather than search further, however, it is often better to try to understand how particular groups and clusters of people came to hold such views.

We should recognise the disadvantages of working in a place like the University of Oxford when it comes to studying human societies. It is there and in similar places (Harvard and Heidelberg are usually cited) that misconceptions about the nature of society and of other humans can so easily form. This is due to the staggering and strange social, geographical and economic separation of the supposed crème de la crème of society into such enclaves. The elite universities in Paris could be added to a roll call of centres of delusion. They were not in the original listing of a few towns because it was in Paris that the man making that initial list, Pierre Bourdieu, ended up working.44 And there is much more to Paris than its universities, but that is also true of Oxford, Boston and Heidelberg.

It is easier to grow up in Boston or Oxford and know nothing of life on the other side of your city than is the case in Paris or Heidelberg. This is because social inequality in the US and the UK is greater than in France or Germany. Maintaining high levels of inequality within a country results in rising social exclusion. This occurs even without increases in income inequality. Simply by holding inequalities at a sufficiently high level the sense of failure of most is maintained long enough to force people to spend highly and get into further debt just to maintain their social position. And one effect of living in an affluent society under conditions of high inequality is that social polarisation increases between areas. Geographically, with each year that passes, where you live becomes more important than it was last year. As the repercussions of rising social exclusion grow, the differences between the educational outcomes of children going to different schools become ever more apparent; buying property with mortgage debt in more expensive areas appears to become a better long-term ‘investment’ opportunity, and thus in so many ways, as the difficulties of living in poverty under inequality increase, living away from the poorer people becomes ever more attractive, and for most people, ever more unobtainable.

When social inequalities become extremely high the poor are no longer considered similar people to the rich (and even to the average person), and issues such as poverty can become little investigated because they are seen not to matter. Because of this, and because it is hard to ask general questions about poverty and living standards in the most unequal of rich countries (that is, the US, based on income inequalities) it is necessary to look at slightly more equitable places, such as Britain, to understand how poverty can rise even when (unlike in the US) the real incomes of the poor are rising slightly. Britain is among those nations in which rates of poverty resulting from inequalities have been very carefully monitored, and so it is worth considering as a general example of (and a warning about) the way poverty can grow under conditions of affluence, even of economic boom, given enough inequality. In the decade before the 2008 economic crash hit and poverty by any definition increased sharply once again, Britain provided an abject lesson in how social exclusion could grow sharply. It grew simply because the rich took so much more of what growth there had been than the poor.

The social experiment of holding inequality levels in Britain high during the economic boom, which coincided with Tony Blair’s 1997–2007 premiership, has allowed the effects of such policies to be monitored by comparing surveys of poverty undertaken at around the start of the period with those undertaken towards the end.45 Among British adults during the Blair years the proportion unable to make regular savings rose from 25% to 27%; the number unable to afford an annual holiday away from home rose from 18% to 24%; and the national proportion who could not afford to insure the contents of their home climbed a percentage point, from 8% to 9%. However, these national proportions conceal the way in which the rising exclusion has hit particular groups especially hard, not least a group that the Blair government had said it would help above all others: children living in poverty.

The comparison of poverty surveys taken towards the start and end of Tony Blair’s time in office found that, of all children, the proportion living in a family that could not afford to take a holiday away from home and family relations rose between 1999 and 2005, from 25% to 32%. This occurred even as the real incomes of most of the poorest rose; they just rose more for the affluent. In consequence, as housing became more unequally distributed, the number of children of school age who had to share their bedroom with an adult or sibling over the age of 10 and of the opposite sex rose from 8% to 15% nationally. It was in London that such overcrowding became most acute and where sharing rooms rose most quickly. Keeping up appearances for the poor in London was much harder than in Britain as a whole,46 not simply because London had less space, but because within London other children were so often very wealthy. Even among children going to the same school the incomes of their parents had diverged and consequently standards of living and expectations of the norm did too. Who do you have round for tea from school when you are ashamed of your home because (as a teenage girl) you do not want to admit to sharing a bedroom with your older brother? Nationally, the proportion who said their parent(s) could not afford to let them have friends round for tea doubled, from 4% to 8%. The proportion of children who could not afford to pursue a hobby or other leisure activity also rose, from 5% to 7%, and the proportion who could not afford to go on a school trip at least once a term doubled, from 3% to 6%. For children aged below five, the proportion whose parents could not afford to take them to playgroup each week also doubled under the Blair government, from 3% to 6%.

For those who do not have to cope with debts it becomes easier to imagine why you might go further into debt when that debt allows you, for example, to have the money to pay a pound to attend a playgroup rather than sit another day at home with your toddler. Taking out a little more debt helps pay another couple of pounds so that your school-age child can go on a school trip and not have to pretend to be ill that day. Concealing poverty becomes ever more difficult in an age of consumption. When you are asked at school where you went on holiday, or what you got for Christmas, a very active imagination helps in making up a plausible lie. Living in a consumerist society means living with the underlying message that you do not get to go on holiday or get presents like other children because you have not been good enough, because your family are not good enough. The second most expensive of all consumption items are housing costs – the rent or mortgage – and these have also diverged as income inequalities have increased. Having to move to a poorer area, or being unable to move out of one, is the geographical reality of social exclusion. People get into further debt to avoid this. But usually debt simply delays the day you have to move and makes even deeper the depth of the hole you move into. The most expensive consumer item is a car (cars have been more costly than home buying in aggregate). This is why so many people buy cars through hire purchase, or ‘on tick’ as it used to be called in Britain, or ‘with finance’ as the euphemism now is. The combined expense and necessity of car ownership is the reason why not having a car is for many a contemporary mark of social failure. It is also closely connected to why so many car firms were badly hit so early on in the crash of 2008, as they were selling debt as much as selling cars (see Section 6.1).

Snap-shots of figures from comparative social surveys reveal the direction of social change, but underplay the extent to which poverty is experienced over time because many more families and individuals experience poverty than are poor at any one time. The figures on the growth of social exclusion under the New Labour government often surprise people in Britain because they are told repeatedly how much that government was doing to try to help the poor, and there were a lot of policies.47 What these policies did achieve was to put a floor under how bad things could get for most, but not all, people, by introducing a low minimum wage, and a higher minimum income for families with children through complex tax credits plus a huge range of benefits-in-kind ‘delivered’ through various programmes. However, the minimums were not enough to enable many families to live in a ‘respectable’ way. They were not designed to do this, but to act as a launching pad from which people tried to work harder and onto which they fell during the bad times. Like a trampoline at the bottom of a vertical obstacle course where different parts of the climbing wall are labelled exclusion and inclusion, New Labour policy helped cycle people around various ‘opportunities’ in life, including bouncing a few very high, given the government’s parallel policies up until 2008 of being seriously relaxed about financial regulation, and also about the wealth of the super-rich.48 More benevolent social policies might have put a slightly higher limit on how far down it was possible to fall if you had children, but they did nothing to narrow the range of inequalities in incomes and wealth overall, nothing to reduce the number of people who ended up falling down into a cycle of deprivation or the amount of money which ended up trickling into the pockets of a few.

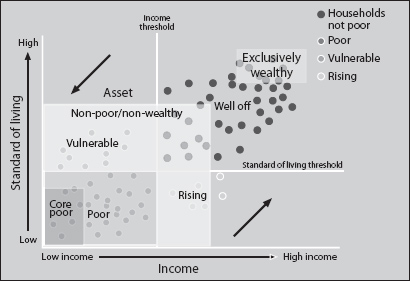

Figure 8 illustrates the cycle of exclusion and inclusion in societies like Britain. Each circle in the figure represents the economic position of a household at one fixed instance; the arrows show the prevailing direction in which most households move socially, and the boxes show how these households can be categorised at any point in time.49 Starting bottom right, as a household’s income rises when a job is gained or a partnership is formed, expenditure and standard of living also rise, but a little later. It is that expenditure that allows the household to become better socially included, to afford a little saving, to have an annual holiday. A few households, usually dual earner, see their incomes rise even further, experience no financial knocks, no redundancies, little illness, no divorce, and begin to be able to save more, take a few more holidays a year, move to a ‘better’ area, send their children to a private school. If all still goes well they typically take out private health insurance and move into the top right box where they are excluded from the norms of society by being above them. This group grew slightly in size under Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s and again since 1997 as the incomes of those already paid most were allowed to rise most quickly. However, most people whose incomes rose in countries such as the US and Britain did not receive enough extra to be able to enter this box, and many who did fell out, again through divorce, downgrading at work or simply through falling ill.

Source: Adapted from David Gordon’s original and much replicated drawing.50 See publication details of various of the works (where earlier versions appear) at the Townsend Centre for International Poverty Research, University of Bristol (www.bris.ac.uk/poverty/).

When a financial knock comes households are hardly ever in a position to immediately decrease their outgoings in line with their decreased income. Instead they move across the diagram in Figure 8, from right to left, from being exclusively wealthy to being normal; from being normal to being vulnerable, exhausting savings and getting into debt to avoid having to reduce expenditure as rapidly as their incomings are falling. They do this to avoid having to take no holidays at all, after they have become used to having several a year. They think they are being frugal, but they are spending more than is coming in because, as the width and the height of the cycle becomes larger with growing inequality, it becomes harder to learn how to live like others live. Households cut back, but rarely in direct proportion to the cuts in their income, largely because they feel they have to maintain their dignity and social standing. In the same way, they rarely increase expenditure directly in line with any windfall; given a lot of money, most people do not know what to do with it at first. It is because of our commitments and burdens that socially we spiral anti-clockwise around Figure 8, often in small circles in just part of the realm of possibilities, not too near the bottom if we are lucky, spinning round over larger cycles, or trapped in the bottom left-hand corner if less fortunate. After misfortune, those lucky enough to find another partner with a good income quickly following divorce, lucky enough to quickly get another job or to quickly recover from the illness that had led to their troubles, can cycle round again, but many are not so lucky and drop down the left-hand side of the cycle, down to poverty and social exclusion of various degrees of acuteness, and most stay there for considerable lengths of time.

As expenditure is (over the long term) clearly constrained by income, the higher the income inequalities a society tolerates, the greater inequalities in standards of living and expenditure its people will experience, and the wider and higher will be both axes of possibility shown in Figure 8. Very few households cycle from the extremes of top right to bottom left. Instead there are many separate eddies and currents within those extremes. The rich live in fear of being ‘normal’ and in hope of being ever more rich, but have little concept of what poverty really is. The richer they get the more they rely on interest ‘earned’ from their savings to fund their expenditure. Much of that income is derived from their banks lending those savings to the poor. Sub-prime mortgages were especially fashionable because they were aimed at the poor from whom greatest profit is usually made by lenders through the highest interest rates being charged. Without the poor paying interest on debt, and the average paying instalments on mortgages, the rich could not have so many holidays, could not spiral around in their own worlds as easily. Each rich saver requires the additional charges on debt payment of many dozens of average and poor people to generate the interest payments that their much larger savings accrue (or did before interest rates were slashed worldwide over the course of 2008). Thus there are only a few households that can ever get to the top right-hand corner of Figure 8; the rich can only ever be a small and very expensive minority.

For each affluent country in the world, in each different decade, a different version of Figure 8 can be drawn. In some countries the range along the bottom is much shorter than in others and as a consequence the range of expenditures along the side is shorter; far fewer families fall down into poverty, and slightly fewer families (but with much less money) move up into the box marked ‘exclusively wealthy’. This was true of Britain and the US half a century ago; it is true of Japan and France today. We choose the shape that Figure 8 takes, or we allow others to choose to shape it, to stretch it, to make the eddies small and smooth or larger and more violent. Insecurity rises when it becomes easier to spin around, or reduces when we reduce inequalities or when we stultify the mixing such as when rank and race are made more permanent attributes and the cycle is a picture of many small eddies. In different countries different social battles have different outcomes; different decisions have been taken by, or were taken for, the people there.

Those countries on the losing side of the Second World War, including Germany, Japan and Italy, had in some cases great equality thrust on them through the eradication of the remaining wealth of their old aristocracies by occupying forces, and by the introduction of land reform resulting in wealth becoming much more equally spread out by the 1950s and 1960s. That land reform occurred under postwar military occupation. American military intervention in Korea and also the establishing of a presence (at one time) in Iceland, ironically also partly contributed to the rise of equality in those countries. The redistribution of land was seen as one way to avert the rise of communism by US planners working overseas after the war.

Figure 8 is drawn to represent the extent of inequalities and the exclusion that results, as experienced in Britain by the early years of the current century. The simplest and most telling way in which that inequality can best be described is to understand that, by 2005, the poorest fifth of households in Britain had each to rely on just a seventh of the income of the best-off fifth of households. A fifth of people had to work for seven days, to receive what another fifth earned in one day. Imagine working Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Monday and Tuesday again, to get what another receives for just one day of work, that single day’s work almost always being less arduous, more fulfilling, more enjoyable, and of higher status, than your seven. Well-paid work is almost certainly a far more luxurious pastime than seven days spent surviving on the dole, or on a state pension. Well-paid work is almost always non-manual, undertaken in well-heated or air-conditioned premises, sitting in comfortable chairs, doing interesting things, meeting people, travelling. People gaining well-paid work acclimatise extremely quickly to their lot and rarely count their blessings. The affluent are not paid more because their work is more arduous, but because of the kind of society they live in. They are paid similarly to other affluent people living in the same country.

International comparisons of the quintile range of income inequality are some of the most telling comparisons that can be made between countries. The best current estimate of UK income inequality on this measure is that the best-off fifth received 7.2 times more income on average than the worst-off fifth each year by 2005.51 According to the tables in the UN Development Programme’s Annual Report, the most widely used source, that ratio has most recently been 6.1 to 1 in Ireland, in France it is 5.6 to 1, in Sweden it is 4.0 to 1 and in Japan it is 3.4 to 1. By contrast, in the US that same ratio of inequality is 8.5 to 1.

To reiterate, in a country like Japan where, if you are at the bottom of the heap, you need ‘only’ work Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday morning, to gain what those at the top are awarded for working just on Monday, low-paid work is not so bad; although the figures are disputed, and although all is far from utopia in Japan, that extent of equality has actually been achieved. Want to find a country where people of different social strata live more often in similar neighbourhoods than they do in Europe? Visit Japan. In contrast, in the US you need to labour for the number of days the worst-off (day labourers) work in Japan and a whole additional five-day working week to achieve the same reward, the same money as the best-off fifth earn in a single day. If you want to find a country with far less mixed neighbourhoods than in Europe, visit the US.

The human failing most closely associated with exclusion is a particular kind of bigotry, an intolerance of those seen as beneath you, and the extent of such bigotry varies greatly between places. The structure of human relationships varies between different affluent countries most clearly according to how unequal each is. In affluent countries with great inequalities it is possible to hire armies of cleaners and to set them to work each night making office blocks appear immaculate in the morning. And it is not just the cleaners, but many more people who need to wake up in the early hours to undertake the long commute to work in those countries as compared with more equitable ones (commuting times are shorter, there is better public transport and even the trains run to time more often in more equal affluent countries). Many more try to hold down several jobs at once in unequal countries because they need the extra money. More are day labourers, regularly looking for new piecework, often spending many days without paid work hanging around where they might be picked up to do a cash-in-hand labouring job. Of those with a work contract in unequal countries, many more have to work long hours in paid employment; holiday, maternity and sickness pay is often worse than in most OECD countries, or non-existent.52

Children are far more often put into day care in countries where wages and benefits are more unequal. More inequality also results in more nannies, day care for the children of the affluent. With greater inequality the cost of day care in general is less for the affluent as the wages of the carers are relatively lower and more ‘affordable’, but the need for two adults to earn in affluent families is greater in unequal countries as even affluent couples tend not to think they have enough coming in when wide inequalities are normal. Those who are affluent do not compare themselves and their lives with the lives of those who care for their children or who clean their workplaces. They compare themselves with other couples they see as like themselves, in particular other couples with just a little bit more. In more unequal affluent countries when couples split up, which they do more frequently, they become new smaller households with lower incomes and so often drop down the sharply differentiated social scale. It is not just because of the awkwardness of the split that they lose so many of their ‘friends’. It is because friendship in more unequal countries is more often about mixing with the smaller group of people who are like you.

People live far more similar (and often simpler) lives in affluent countries where incomes, expenditures and expectations are more equal. For instance, what they eat at breakfast will be similar to what others eat, and they are all more likely to be eating breakfast, not having to skip that meal for the commute, or sending their children to school hungry to save a little money. In more equal countries children are much more likely to travel to the nearest school to learn; so the lengths of journeys to school are shorter and far fewer children need to be driven. They are more likely to eat with their parents before school and they are more likely to still have two parents at home. Their friends will more often be drawn from nearby, and from much more of a cross-section of society than in more unequal countries. And that wider cross-section will not vary as much by income, standard of living and expectations. In more unequal countries parents feel the need to be more careful in monitoring who their child’s friends are (and even who their own friends are). If they are rich then more often they drive their children to visit friends past the homes of nearby children considered less suitable to be their offsprings’ friends, driving from affluent enclave to affluent enclave. If very rich they even have another adult do that driving. But the most effective way for parents in an affluent unequal country to monitor who their offspring mixes with is through segregating them from others by where they choose to live. Parents do this not because they are callous, but because they are insecure, more afraid, more ignorant of others, less trustful, in more unequal countries. The evidence that levels of trust are higher in more equal countries was made widely available in 2009 by the Equality Trust (www.equalitytrust.org.uk/why/evidence).