Operational amplifiers, usually called op amps, are important components of electronic circuits. Basically, an op amp is a very high-gain voltage amplifier, having a voltage gain of 100 000 or more. Although an op amp may consist of more than two dozen transistors, one dozen resistors, and perhaps one capacitor, it may be as small as an individual resistor. Because of its small size and relatively simple external operation, for purposes of an analysis or a design an op amp can often be considered as a single circuit element.

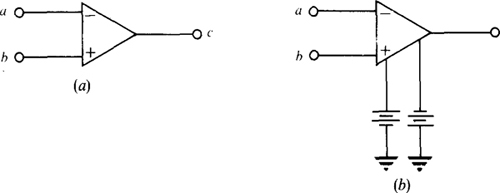

Figure 6-la shows the circuit symbol for an op amp. The three terminals are an inverting input terminal a (marked —), a noninverting input terminal b (marked +), and an output terminal c. But a physical operational amplifier has more terminals. The extra two shown in Fig. 6-1b are for dc power supply inputs, which are often +15 V and —15 V. Both positive and negative power supply voltages are required to enable the output voltage on terminal c to vary both positively and negatively with respect to ground.

Fig. 6-1

The circuit of Fig. 6-2a, which is a model for an op amp, illustrates how an op amp operates as a voltage amplifier. As indicated by the dependent voltage source, for an open-circuit load the op amp provides an output voltage of v0 = A (v+ — v–), which is A times the difference in input voltages. This A is often referred to as the open-loop voltage gain. From A (v+ — v–), observe that a positive voltage v + applied to the noninverting input terminal b tends to make the output voltage positive, and a positive voltage v– applied to the inverting input terminal a tends to make the output voltage negative.

The open-loop voltage gain A is typically so large (100 000 or more) that it can often be approximated by infinity (∞), as is shown in the simpler model of Fig. 6-2b. Note that Fig. 6-2b does not show the sources or circuits that provide the input voltage v+ and v- with respect to ground. Instead, just the voltages v+ and V- are shown. Doing this simplifies the circuit diagrams without any loss of information.

In Fig. 6-2a, the resistors shown at the input terminals have such large resistances (megohms) as compared to other resistances (usually kilohms) in a typical op-amp circuit, that they can be considered to be open circuits, as is shown in Fig. 6-2b. As a consequence, the input currents to an op amp are almost always negligibly small and assumed to be zero. This approximation is important to remember.

The output resistance R0 may be as large as 75 Ω or more, and so may not be negligibly small. When, however, an op amp is used with negative-feedback components (as will be explained), the effect of R0 is negligible, and so R0 can be replaced by a short circuit, as shown in Fig. 6-2b. Except for a few special op-amp circuits, negative feedback is always used.

Fig. 6-2

The simple model of Fig. 6-2b is adequate for many practical applications. However, although not indicated, there is a limit to the output voltage: It cannot be greater than the positive supply voltage or less than the negative supply voltage. In fact, it may be several volts less in magnitude than the magnitude of the supply voltages, with the exact magnitude depending upon the current drawn from the output terminal. When the output voltage is at either extreme, the op amp is said to be saturated or to be in saturation. An op amp that is not saturated is said to be operating linearly.

Since the open-loop voltage gain A is so large and the output voltage is limited in magnitude, the voltage v+ — v– across the input terminals has to be very small in magnitude for an op amp to operate linearly. Specifically, it must be less than 100 μV in a typical op-amp application. (This small voltage is obtained with negative feedback, as will be explained.) Because this voltage is negligible compared to the other voltages in a typical op-amp circuit, this voltage can be considered to be zero. This is a valid approximation for any op amp that is not saturated. But if an op amp is saturated, then the voltage difference v+ — v– can be significantly large, and typically is.

Of less importance is the limit on the magnitude of the current that can be drawn from the op-amp output terminal. For one popular op amp this output current cannot exceed 40 mA.

The approximations of zero input current and zero voltage across the input terminals, as shown in Fig. 6-3, are the bases for the following analyses of popular op-amp circuits. In addition, nodal analysis will be used almost exclusively.

Fig. 6-3

Figure 6-4 shows the inverting amplifier, or simply inverter. The input voltage is v0 and the output voltage is v0. As will be shown, v0 = Gvi in which G is a negative constant. So, the output voltage v0 is similar to the input voltage vi but is amplified and changed in sign (inverted).

Fig. 6-4

As has been mentioned, it is negative feedback that provides the almost zero voltage across the input terminals of an op amp. To understand this, assume that in the circuit of Fig. 6-4 vi is positive. Then a positive voltage appears at the inverting input because of the conduction path through resistor Ri. As a result, the output voltage v0 becomes negative. Because of the conduction path back through resistor Rf, this negative voltage also affects the voltage at the inverting input terminal and causes an almost complete cancellation of the positive voltage there. If the input voltage vi had been negative instead then the voltage fed back would have been positive and again would have produced almost complete cancellation of the voltage across the op-amp input terminals.

This almost complete cancellation occurs only for a nonsaturated op amp. Once an op amp becomes saturated, however, the output voltage becomes constant and so the voltage fed back cannot increase in magnitude as the input voltage does.

In every op-amp circuit in this chapter, each op amp has a feedback resistor connected between the output terminal and the inverting input terminal. Consequently, in the absence of saturation, all the op amps in these circuits can be considered to have zero volts across the input terminals. They can also be considered to have zero currents into the input terminals because of the large input resistances.

The best way to obtain the voltage gain of the inverter of Fig. 6-4 is to apply KCL at the inverting input terminal. Before doing this, though, consider the following. Since the voltage across the op-amp input terminals is zero, and since the noninverting input terminal is grounded, it follows that the inverting input terminal is also effectively at ground. This means that all the input voltage vi is across resistor Ri and that all the output voltage v0 is across resistor Rf. Consequently, the sum of the currents entering the inverting input terminal is

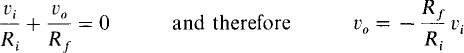

So, the voltage gain is G = –(Rf/Ri), which is the negative of the resistance of the feedback resistor divided by the resistance of the input resistor. This is an important formula to remember for analyzing an op-amp inverter circuit or for designing one. (Do not confuse this gain G of the inverter circuit with the gain A of the op amp itself.)

It should be apparent that the input resistance is just Ri. Additionally, although the load resistor RL affects the current that the op amp must provide, it has no effect on. the voltage gain.

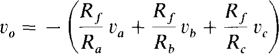

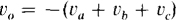

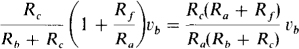

The summing amplifier, or summer, is shown in Fig. 6-5. Basically, a summer is an inverter circuit with more than one input. By convention, the sources for providing the input voltages va, vb, and vc are not shown. If this circuit is analyzed with the same approach used for the inverter, the result is

For the special case of all the resistances being the same, this formula simplifies to

There is no special significance to the inputs being three in number. There can be two, four, or more inputs.

Fig. 6-5

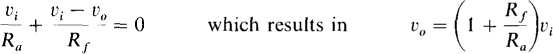

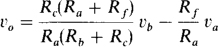

Figure 6-6 shows the noninverting voltage amplifier. Observe that the input voltage vi is applied at the noninverting input terminal. Because of the almost zero voltage across the input terminals, vi is also effectively at the inverting input terminal. Consequently, the KCL equation at the inverting input terminal is

Fig. 6-6

Since the voltage gain of 1/(1 + Rf/Ra) does not have a negative sign, there is no inversion with this type of amplifier. Also, for the same resistances, the magnitude of the voltage gain is slightly greater than that of the inverter. But the big advantage that this circuit has over the inverter is a much greater input resistance. As a result, this amplifier will readily amplify the voltage from a source that has a large output resistance. In contrast, if an inverter is used, almost all the source voltage will be lost across the large output resistance of the source, as should be apparent from voltage division.

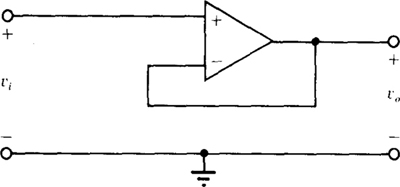

The buffer amplifier, also called the voltage follower or unity-gain amplifier, is shown in Fig. 6-7. It is basically a noninverting amplifier in which resistor Ra is replaced by an open circuit and resistor Rf by a short circuit. Because there is zero volts across the op-amp input terminals, the output voltage is equal to the input voltage: v0 = vi. Therefore, the voltage gain is 1. This amplifier is used solely because of its large input resistance, in addition to the typical op-amp low output resistance.

Fig. 6-7

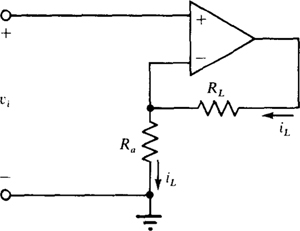

There are applications, in which a voltage signal is to be converted to a proportional output current such as, for example, in driving a deflection coil in a television set. If the load is floating (neither end grounded), then the circuit of Fig. 6-8 can be used. This is sometimes called a voltage-to-current converter. Since there is zero volts across the op-amp input terminals, the current in resistor Ra is iL = vi/Ra, and this current also flows through the load resistor RL. Clearly, the load current iL is proportional to the signal voltage vi.

Fig. 6-8

The circuit of Fig. 6-8 can also be used for applications in which the load resistance RL varies but the load current iL must be constant. vi is made a constant voltage and vi and Ra are selected such that vi/Ra is the desired current iL. Consequently, when RL varies, the load current iL does not change. Of course, the load current cannot exceed the maximum allowable op-amp output current, and the load voltage plus the source voltage cannot exceed the maximum obtainable output voltage.

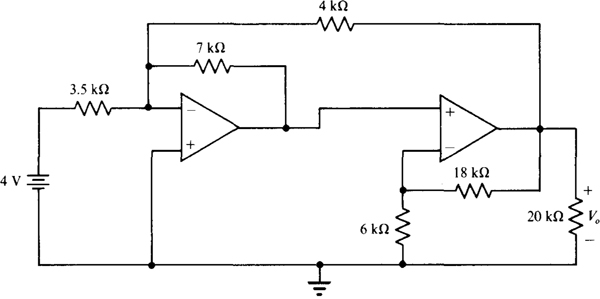

Often, op-amp circuits are cascaded, as shown, for example, in the circuit of Fig. 6-9. In a cascade arrangement, the input to each op-amp stage is the output from a preceding op-amp stage, except, of course, for the first op-amp stage. Cascading is often used to improve the frequency response, which is a subject beyond the scope of the present discussion.

Fig. 6-9

Because of the very low output resistance of an op-amp stage as compared to the input resistance of the following stage, there is no loading of the op-amp circuits. In other words, connecting the op-amp circuits together does not affect the operation of the individual op-amp circuits. This means that the overall voltage gain GT is equal to the product of the individual voltage gains G1, G2, G3, …; that is, GT = G1 G2 G3….

To verify this formula, consider the circuit of Fig. 6-9. The first stage is an inverting amplifier, the second stage is a noninverting amplifier, and the last stage is another inverting amplifier. The output voltage of the first inverter is – (6/2)vi = – 3vi, which is the input to the noninverting amplifier. The output voltage of this amplifier is (1 + 4/2)(– 3vi) = –9vi. And this is the input to the inverter of the last stage. Finally, the output of this stage is v0 = –9vi,(–10/5) = 18vi. So, the overall voltage gain is 18, which is equal to the product of the individual voltage gains: GT = (–3)(3)(–2) = 18.

If a circuit contains multiple op-amp circuits that are not connected in a cascade arrangement, then another approach must be used. Nodal analysis is standard in such cases. Voltage variables are assigned to the op-amp output terminal nodes, as well as to other nongrounded nodes, in the usual manner. Then nodal equations are written at the nongrounded op-amp input terminals to take advantage of the known zero input currents. They are also written at the nodes at which the voltage variables are assigned, except for the nodes that are at the outputs of the op amps. The reason for this exception is that the op-amp output currents are unknown and if nodal equations are written at these nodes, additional current variables must be introduced, which increases the number of unknowns. Usually, this is undesirable. This standard analysis approach applies as well to a circuit that has just a single op amp.

Even if multiple op-amp circuits are not connected in cascade, they can sometimes be treated as if they were. This should be considered especially if the output voltage is fed back to op-amp inputs. Then the output voltage can often be viewed as another input and inserted into known voltage-gain formulas.

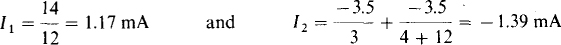

6.1 Perform the following for the circuit of Fig. 6-10. Assume no saturation for parts (a) and (b). (a) Let Rf = 12 kΩ, Va = 2 V, and Vb = 0 V. Determine V0 and I0. (b) Repeat part (a) for Rf = 9 kΩ, Va = 4 V, and Vb = 2 V. (c) Let Va = 5 V and Vb = 3V and determine the minimum value of Rf that will produce saturation if the saturation voltage levels are V0 = ± 14 V.

Fig. 6-10

(a) Since for Vb = 0 V the circuit is an inverter, the inverter voltage-gain formula can be used to obtain V0.

Then KCL applied at the output terminal gives

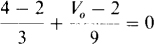

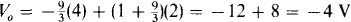

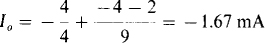

(b) Because of the zero voltage across the op-amp input terminals, V– = Vb = 2 V. Then, by KCL applied at the inverting op-amp input terminal,

The solution is V0 = – 4 V. Another approach is to use superposition. Since the circuit is an inverter as regards Va and is a noninverting amplifier as regards Vb, the output voltage is

With V0 known, KCL can be applied at the output terminal to obtain

(c) By superposition,

Since Rf must be positive, the op amp can saturate only at the specified — 14-V saturation voltage level. So,

the solution to which is Rf = 25.5 kΩ. This is the minimum value of Rf that will produce saturation. Actually the op amp will saturate for Rf ≥ 25.5 kΩ.

6.2 Assume for the summer of Fig. 6-5 that Ra = 4 kΩ. Determine the values of Rb, Rc, and Rf that will provide an output voltage of V0 = — (3va + 5vh + 2vc).

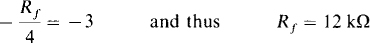

First, determine Rf. The contribution of V0 to V0 is –(Rf/Ra)va. Consequently, for a voltage gain of —3 and with Ra = 4 kΩ,

Next, determine Rh. The contribution of vb to V0 is —(Rf/Rb)vb. So, with Rf = 12kΩ and for a voltage gain of — 5,

Finally, the contribution of vc to vo is —(Rf/Rc)vc. So, with Rf = 12 kΩ and for a voltage gain of — 2,

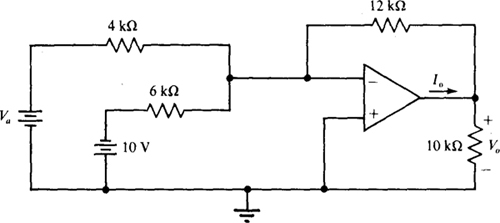

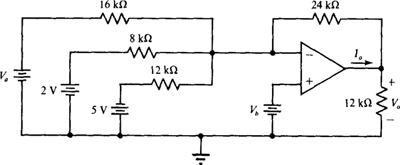

6.3 In the circuit of Fig. 6-11, first find Vo and Io for Va = 4 V. Then assume op-amp voltage saturation levels of V0 = ± 12 V and determine the range of Va for linear operation.

Fig. 6-11

Because this circuit is a summer,

and

Now, finding the range of Va for linear operation,

Therefore, Va = (20 ± 12)/3. So, for linear operation, Va must be less than (20 + 12)/3 = 10.7 V and greater than (20 – 12)/3 = 2.67 V: 2.67 V < Va < 10.7 V.

6.4 Calculate V0 and Ia in the circuit of Fig. 6-12.

Fig. 6-12

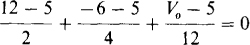

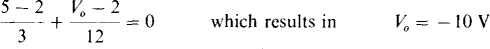

Because of the zero voltage drop across the op-amp input terminals, the voltage with respect to ground at the inverting input terminal is the same 5 V that is at the noninverting input terminal. With this voltage known, the voltage V0 can be determined from summing the currents flowing into the inverting input terminal:

Thus, V0 = –4 V. Finally, applying KCL at the output terminal gives

6.5 In the circuit of Fig. 6-13a, a 10-kΩ load resistor is energized by a source of voltage vs that has an internal resistance of 90 kΩ. Determine vL, and then repeat this for the circuit of Fig. 6-13b.

Fig. 6-13

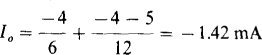

Voltage division applied to the circuit of Fig. 6-13a gives

So, only 10 percent of the source voltage reaches the load. The other 90 percent is lost across the internal resistance of the source.

For the circuit of Fig. 6-13ft, no current flows in the signal source because of the large op-amp input resistance. Consequently, there is a zero voltage drop across the source internal resistance, and the entire source voltage appears at the noninverting input terminal. Finally, since there is zero volts across the op-amp input terminals, vL = vs So, the insertion of the voltage follower results in an increase in the load voltage from 0.1 vs to vs.

Note that although no current flows in the 90-kΩ resistor in the circuit of Fig. 6-13b, there is current flow in the 10-kΩ resistor, the path for which is not evident from the circuit diagram. For a positive vL, this current flows down through the 10-kΩ resistor to ground, then through the op-amp power supplies (not shown), and finally through the op-amp internal circuitry to the op-amp output terminal.

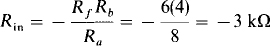

6.6 Obtain the input resistance Rin of the circuit of Fig. 6-14a.

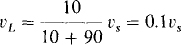

The input resistance Rin can be determined in the usual way, by applying a source and obtaining the ratio of the source voltage to the source current that flows out of the positive terminal of the source. Figure 6-14b shows a source of voltage Vs applied. Because of the zero current flow into the op-amp noninverting input terminal, all the source current Is flows through Rf, thereby producing a voltage of IsRf across it, as shown. Since the voltage across the op-amp input terminals is zero, this voltage is also across Ra and results in a current flow to the right of IsRf/Ra. Because of the zero current flow into the op-amp inverting input terminal, this current also flows up through Rb, resulting in a voltage across it of IsRfRb/Ra, positive at the bottom. Then, KVL applied to the left-hand mesh gives

Fig. 6-14

The input resistance being negative means that this op-amp circuit will cause current to flow into the positive terminal of any voltage source that is connected across the input terminals, provided that the op amp is not saturated. Consequently, the op-amp circuit supplies power to this voltage source. But, of course, this power is really supplied by the dc voltage sources that energize the op amp.

6.7 For the circuit of Fig. 6-14a, let Rf = 6 kΩ, Rb = 4 kΩ, and Ra = 8 kΩ, and determine the power that will be supplied to a 4.5-V source that is connected across the input terminals.

From the solution to Prob. 6.6,

Therefore, the current that flows into the positive terminal of the source is 4.5/3 = 1.5 mA. Consequently, the power supplied to the source is 4.5(1.5) = 6.75 mW.

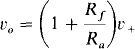

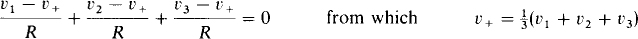

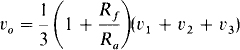

6.8 Obtain an expression for the voltage v0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-15.

Fig. 6-15

Clearly, in terms of v+, this circuit is a noninverting amplifier. So,

The voltage v+ can be found by applying nodal analysis at the noninverting input terminal.

Finally, substituting for v+ yields

From this result it is evident that the circuit of Fig. 6-15 is a noninverting summer. The number of inputs is not limited to three. In general,

in which n is the number of inputs.

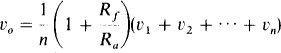

6.9 In the circuit of Fig. 6-15, assume that Rf = 6 kΩ and then determine the values of the other resistors required to obtain v0 = 2(v1 + v2 + v3).

From the solution to Prob. 6.8, the multiplier of the voltage sum is

As long as the value of R is reasonable, say in the kilohm range, it does not matter much what the specific value is. Similarly, the specific value of RL does not affect v0 provided RL is in the kilohm range or greater.

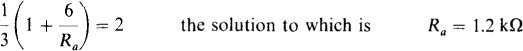

6.10 Obtain an expression for the voltage gain of the op-amp circuit of Fig. 6.16.

Fig. 6-16

Superposition is a good approach to use here. If vb = 0 V, then the voltage at the noninverting input terminal is zero, and so the amplifier becomes an inverting amplifier. Consequently, the contribution of va to the output voltage v0 is –(Rf/Ra)va. On the other hand, if va = 0 V, the circuit becomes a noninverting amplifier that amplifies the voltage at the noninverting input terminal. By voltage division, this voltage is Rcvb/(Rb + Rc). Therefore, the contribution of vb to the output voltage v0 is

Finally, by superposition the output voltage is

This voltage-gain formula can be simplified by the selection of resistances such that Ra/Rf = Rb/Rc. The result is

in which case the output voltage v0 is a constant times the difference vb – va of the two input voltages. This constant can, of course, be made 1 by the selection of Rf = Ra. For obvious reasons the circuit of Fig. 6-16 is called a difference amplifier.

6.11 For the difference amplifier of Fig. 6-16, let Rf = 8 kΩ. and then determine values of Ra, Rb, and Rc to obtain v0 = 4(vb – va).

From the solution to Prob. 6.10, the contribution of –4va to v0 requires that Rf/Ra = 8/Ra = 4, and so Ra = 2 kΩ For this value of Ra and for Rf = 8 kΩ, the multiplier of vb becomes

Therefore, Rc = 4Rb gives the desired response, and obviously there is no unique solution, as is typical of the design process. So, if Rb is selected as 1 kΩ, then Rc = 4 kΩ. And for Rb = 2 kΩ, Rc = 8 kΩ, and so on.

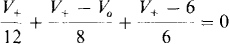

6.12 Find V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-17.

Fig. 6-17

By nodal analysis at the noninverting input terminal,

which simplifies to V0 = 3V + – 8. But by voltage division,

And so,

6.13 For the op-amp circuit of Fig. 6-18, calculate V0. Then assume op-amp saturation voltages of ± 14 V, and find the resistance of the feedback resistor Rf that will result in saturation of the op amp.

Fig. 6-18

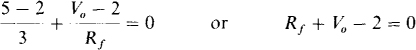

Then since V– = V+ = 2 V, the node-voltage equation at the inverting input terminal is

Now, Rf is to be changed to obtain saturation at one of the two voltage saturation levels. From KCL applied at the inverting input terminal,

So, Rf = 2 – V0. Clearly, for a positive resistance value of Rf, the saturation must be at the negative voltage level of — 14 V. Consequently, Rf = 2 — (— 14) = 16 kΩ. Actually, this is the minimum value of R; that gives saturation. There is saturation for Rf ≥ 16 kΩ.

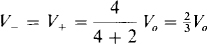

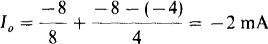

6.14 For the circuit of Fig. 6-19, calculate the voltage V0 and the current I0.

Fig. 6-19

In Fig. 6-19, observe the lack of polarity references for V– and V +. Polarity references are not essential because these voltages are always referenced positive with respect to ground. Likewise the polarity reference for V0 could have been omitted.

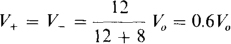

By voltage division,

With V– = 0.6 V0, the node-voltage equation at the inverting input terminal is

The current I0 can be obtained from applying KCL at the op-amp output terminal:

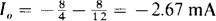

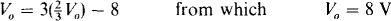

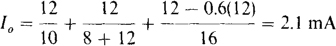

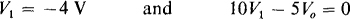

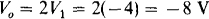

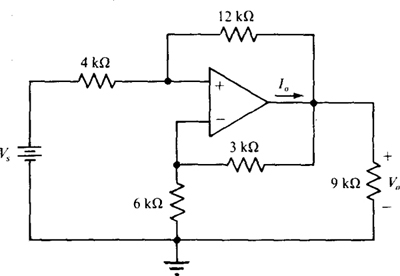

6.15 Determine V0 and I0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-20.

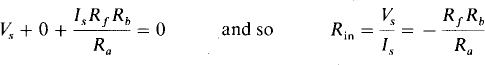

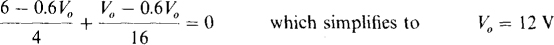

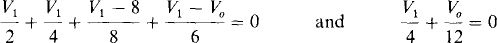

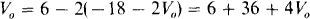

The voltage V0 can be found by writing nodal equations at the inverting input terminal and at the V1 node and using the fact that the inverting input terminal is effectively at ground. From summing currents

Fig. 6-20

into the inverting input terminal and away from the V1 node, these equations are

which simplify to

Consequently,

Finally, I0 is equal to the sum of the currents flowing away from the op-amp output terminal through the 8-kΩ and 4-kΩ resistors:

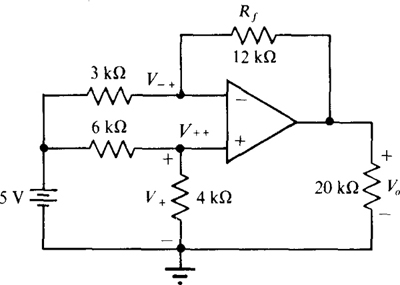

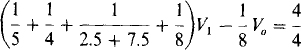

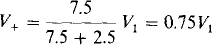

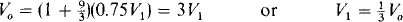

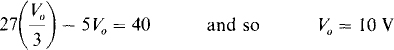

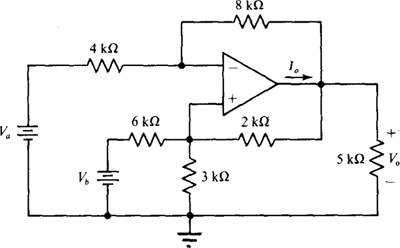

6.16 Find V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-21.

Fig. 6-21

The node-voltage equation at the V1 node is

which upon multiplication by 40 becomes 27V1 – 5V0 = 40. Also, by voltage division,

Further, since the op amp and the 9-kΩ and 3-kΩ resistors form a noninverting amplifier,

Finally, substitution for V1 in the node-voltage equation yields

6.17 Determine V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-22.

Fig. 6-22

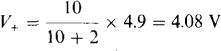

Since V– = 0 V, the node-voltage equations at the V1, and inverting-input terminal nodes are

Multiplying the first equation by 24 and the second equation by 12 gives

from which V0 can be readily obtained: V0 = –1.95 V.

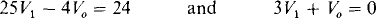

6.18 Assume for the op amp in the circuit of Fig. 6-23 that the saturation voltages are V0 = ± 14 V and that Rf = 6 kΩ. Then determine the maximum resistance of Ra that results in the saturation of the op amp.

The circuit of Fig. 6-23 is a noninverting amplifier, the voltage gain of which is G = 1 + 6/2 = 4. Consequently, V0 = 4V+, and for saturation at the positive level (the only saturation possible), V+ = 14/4 = 3.5 V. The resistance of Ra that will result in this voltage can be obtained by using voltage division:

Fig. 6-23

This is the maximum value of resistance for Ra for which there is saturation. Actually, saturation occurs for Ra ≥ 4 kΩ.

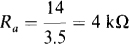

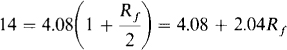

6.19 In the circuit of Fig. 6-23, assume that Ra = 2 kΩ, and then find what the resistance of Rf must be for the op amp to operate in the linear mode. Assume saturation voltages of V0 = ± 14 V.

With Ra = 2 kΩ, the voltage V+ is, by voltage division,

Then for V0 = 14 V, the output voltage equation is

Therefore,

Clearly, then, for V0 to be less than the saturation voltage of 14 V, the resistance of the feedback resistor Ri must be less than 4.86 kΩ.

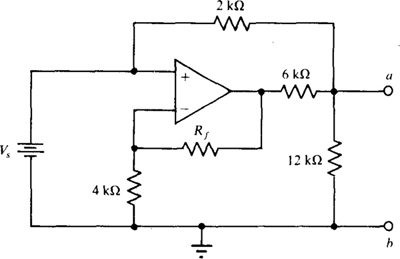

6.20 Obtain the Thévenin equivalent of the circuit of Fig. 6-24 with VTh referenced positive at terminal a.

Fig. 6-24

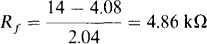

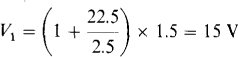

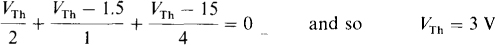

By inspection, the part of the circuit comprising the op amp and the 2.5-kΩ and 22.5-kΩ resistors is a noninverting amplifier. Consequently,

Since VTh = Vab, the node voltage equation at terminal a is

If a short circuit is placed across terminals a and b, then

Consequently,

6.21 Calculate V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-25.

Fig. 6-25

Although nodal analysis can be applied, it is simpler to view this circuit as a summer cascaded with a noninverting amplifier. The summer has two inputs, V0 and 4 V. Consequently, through use of the summer and noninverting voltage formulas,

So,

6.22 Find V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-26.

The circuit of Fig. 6-26 can be viewed as two cascaded summers, with V0 being one of the two inputs to the first summer. The other input is 3 V. Then, the output Vx of the first summer is

Fig. 6-26

The output V0 of the second summer is

Substituting for V1 gives

Finally,

6.23 Determine V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-27.

Fig. 6-27

In this cascaded arrangement, the first op-amp circuit is an inverting amplifier. Consequently, the op-amp output voltage is — (6/2)(— 3) = 9 V. For the second op amp, observe that V– = V+ = 2 V. Thus, the nodal equation at the inverting input terminal is

Perhaps a better approach for the second op-amp circuit is to apply superposition, as follows:

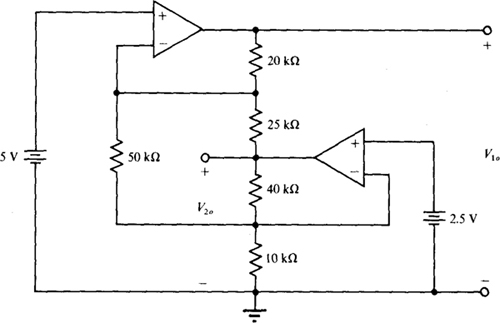

6.24 Find V10 and V20 in the circuit of Fig. 6-28.

Fig. 6-28

Before starting the analysis, observe that because of the zero voltages across the op-amp input terminals, the inverting input voltages are v1— = 8 V and V2— = 4 V. The two equations needed to relate the output voltages can be obtained by applying KCL at the two inverting input terminals. These equations are

These equations simplify to

The solutions to these equations are V10 = 12.5 V and V20 = 1 V.

6.25 For the circuit of Fig. 6-29, calculate V10, V20, I1, and I2. Assume that the op-amp saturation voltages are ± 14 V.

Fig. 6-29

Observe that op amp 1 has no negative feedback and so is probably in saturation, and it is saturated at 14 V because of the 5 V applied to the noninverting input terminal. Assume this is so. Then this 14 V is an input to the circuit portion containing op amp 2, which is an inverter. Consequently, V20 = –(3/12)(14) = –3.5 V. And, by voltage division,

Since this negative voltage is applied to the inverting input of op amp 1, both inputs to this op amp tend to make the op-amp output positive. Also, the voltage across the op-amp input terminals is not approximately zero. For both of these reasons, the assumption is confirmed that op amp 1 is saturated at the positive saturation level. Therefore, V10 = 14V and V20 = – 3.5 V. Finally, by KCL,

6.26 Obtain an expression for the load current iL in the circuit of Fig. 6-30 and show that this circuit is a voltage-to-current converter, or a constant current source, suitable for a grounded-load resistor.

Fig. 6-30

Ans. iL = –vi/R; iL is proportional to vi and is independent of RL

6.27 Find V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-31.

Fig. 6-31

Ans. –4 V

6.28 Assume for the summer of Fig. 6-5 that Rb = 12 kΩ, and obtain the values of Ra, Rc, and Rf that will result in an output voltage of v0 = – (8va + 4vh + 6vt).

Ans. Ra = 6 kΩ, Rc = 8 kΩ, Rf = 48 kΩ

6.29 In the circuit of Fig. 6-32, determine V0 and I0 for Va = 6 V and Vb = 0 V.

Ans. –5 V, –0.625 mA

6.30 Repeat Prob. 6.29 for Va = 16 V and Vb = 4 V.

Fig. 6-32

Ans. 10 V, 1.08 mA

6.31 For the circuit of Fig. 6-32, assume that the op-amp saturation voltages arc ± 14 V and that Vb = 0 V. Determine the range of Va for linear operation.

Ans. –6.67 V < Va < 12 V

6.32 For the difference amplifier of Fig. 6-16, let Rf =12kΩ, and determine the values of Ra, Rb, and Rc to obtain v0 = vb – 2v0.

Ans. Ra = 6 kΩ; Rb and Rc have resistances such that Rb = 2RC

6.33 In the circuit of Fig. 6-33, let Vs = 4 V and calculate V0 and I0.

Fig. 6-33

Ans. 7.2 V, 1.8 mA

6.34 For the op-amp circuit of Fig. 6-33, find the range of Vs for linear operation if the op-amp saturation voltages are V0 = ±14 V.

Ans. –7.78 V < Vs < 7.78 V

6.35 For the circuit of Fig. 6-34, calculate Va and Ia for Va = 0 V and Vb = 12 V.

Fig. 6-34

Ans. –12 V, –7.4 mA

6.36 Repeat Prob. 6.35 for Va = 4 V and Vb = 8 V

Ans. 8 V, 3.27 mA

6.37 Determine V0 and I0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-35 for VaFig. 6-35 for Va = 1.5 V and Vb = 0 V.

Fig. 6-35

Ans. –11 V, –6.5 mA

6.38 Repeat Prob. 6.37 for Va = 5 V and Vb = 3 V.

Ans. –5.67 sV, –3.42 mA

6.39 Obtain V0 and I0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-36 for Va = 12 V and Vb = 0 V.

Fig. 6-36

Ans. 10.8 V, 4.05 mA

6.40 Repeat Prob. 6.39 for Va = 4 V and Vb = 2 V.

Ans. –14.8 V, –7.05 mA

6.41 In the circuit of Fig. 6-37, calculate Va if Vs = 4 V.

Fig. 6-37

Ans. –3.10 V

6.42 Assume for the circuit of Fig. 6-37 that the op-amp saturation voltages are V0 = ±14V. Determine the minimum positive value of Vs that will produce saturation.

Ans. 18.1 V

6.43 Assume for the op-amp in the circuit of Fig. 6-38 that the saturation voltages are V0 = ± 14 V and that Rf = 12 kΩ. Calculate the range of values of Ra that will result in saturation of the op amp.

Fig. 6-38

Ans. Ra ≥ 7 kΩ

6.44 Assume for the op-amp circuit of Fig. 6-38 that Ra = 10 kΩ and that the op-amp saturation voltages are V0 = ± 13 V. Determine the range of resistances of Rf that will result in linear operation.

Ans. 0 Ω ≥ Rf ≥ 8.625 kΩ

6.45 Obtain the Thévenin equivalent of the circuit of Fig. 6-39 for Vs = 4 V and Rf = 8 kΩ. Reference VTh positive toward terminal a.

Fig. 6-39

Ans. 5.33 V, 1.33 kΩ

6.46 Repeat Prob. 6.45 for Vs = 5 V and Rf = 6 kΩ.

Ans. 6.11V, 1.33 kΩ

6.47 Calculate V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-40 with Rf replaced by an open circuit.

Ans. 8 V

6.48 Repeat Prob. 6.47 for Rf = 4 kΩ.

Fig. 6-40

Ans. –4.8 V

6.49 Calculate V0 in the circuit of Fig. 6-41 for Va = 2 V and Vb = 0 V.

Fig. 6-41

Ans. 1.2 V

6.50 Repeat Prob. 6.49 for Va = 3 V and Vb = 2 V.

Ans. 2.13 V

6.51 Determine V10 and V20 in the circuit of Fig 6-42.

Fig. 6-42

Ans. V10 = 1.6V, K20 = 10.5 V