35

Syndication and the Power of Fandom

In the fall of 1969 Star Trek was dead.

Production of the series wrapped for good on January 9. By the time the final episode, “Turnabout Intruder,” aired on June 3, the cast and crew had moved on to new assignments. Costumes had been mothballed and sets disassembled and packed off to the scene dock. NBC used the program as summer replacement fodder, airing reruns until the network’s new shows premiered in September. But now it was over, gone, finished. Nearly everyone—even creator-producer Gene Roddenberry—assumed that, while Star Trek might be fondly remembered by its small but loyal audience, the program would quietly fade away. That’s what cancelled shows did.

Or that’s what most cancelled shows did. A few—usually the most successful series, perennial hits like I Love Lucy—continued to play in syndication, with repeats turning tidy profits thanks to their ongoing popularity. Unfortunately, Star Trek’s syndication prospects seemed dubious. Conventional wisdom dictated that a series needed to compile at least one hundred episodes to become a viable candidate for syndication; Star Trek had a meager seventy-nine. Besides, Trek was never very popular when it was new. Who would bother to watch its reruns?

But no one reckoned with the extraordinary devotion and fervor of the show’s fans, who over the course of the next decade would resurrect Star Trek, turning the “failed” series into a cultural touchstone and a revenue-generating machine. Trek’s near-miraculous return from the grave was unprecedented, and it remains one of the most amazing stories in entertainment history. That tale begins not with Roddenberry, and certainly not with the suits at Paramount, but with the fans themselves.

Rise of the “Trekkies”

DAW Books editor Arthur Sasha coined the term “Trekkie” during an interview with TV Guide’s Peter Hamill at the 1967 WorldCon in New York City. Sasha used the word to refer to the enthusiastic Star Trek fans that helped the show win Best Dramatic Presentation at that year’s Hugo Awards. Hamill repeated the term in his article, and the word stuck. Eventually devotees would disassociate themselves from the “Trekkie” label or modify it to the less juvenile-sounding “Trekker.”

By any name, however, Star Trek fans were a breed apart. Although many other movies, TV shows, and entertainers had inspired legions of energetic followers (Beatlemania springs to mind), no other fan base held such a sense of ownership for their object of adoration, or exerted such influence on its development. Thanks in no small measure to the two triumphant “Save Star Trek” letter-writing campaigns mounted following the series’ first and second seasons, fans felt an intimate connection with the program. Star Trek belonged to them because they believed their efforts had rescued it. And with the Roddenberrian optimism of the show itself, many believed that somehow, some way, they could save Star Trek yet again.

Backing this staunch faith was a depth of emotional, intellectual, and financial investment that outstripped anything previously engendered by a television show. Many fans were profoundly inspired by Star Trek’s vision of a near-utopian future for the human race and refused to surrender the dream to the whims of network programmers. Some were spurred to activism, volunteering in community programs or in support of progressive political causes, with an eye toward building the future Roddenberry had imagined. With no new episodes—and, at the very beginning, no episodes at all—to watch, fans began writing their own Star Trek stories and then publishing their own magazines to share these stories. Fans also voted with their wallets, buying Star Trek products of all sorts as they appeared, quickly turning a trickle of books, models, toys, and other memorabilia into a veritable flood of merchandise. (For more on this, see Chapters 39 and 40, “The Damn Books” and “A Piece of the Action.”) They formed clubs and held conventions. But the most important thing they did was simple: Once Star Trek made its unlikely return to television, they tuned in.

Vindication Through Syndication

In the 1970s, many stations, including WGN in Chicago, ran Star Trek reruns five nights a week.

In 1958, the Henry J. Kaiser Corporation, a U.S. conglomerate that included Kaiser Aluminum and other heavy industrial ventures, acquired independent KULA-TV in Honolulu and launched Kaiser Broadcasting. By the mid-1960s, Kaiser Broadcasting had acquired or started a chain of eight independent stations across the U.S.—including WKGB in Boston, WFLD in Chicago, and KBSC in Los Angeles—and was competing aggressively with network affiliates in major markets. Kaiser executives, who thought Star Trek might serve as effective counter-programming against network stations’ local and national newscasts, began negotiating for syndication rights while the series was still on the air. Kaiser programmers knew that Star Trek had an intensely loyal, mostly young audience and that young viewers seldom watched the news. In late 1969, WKBS in Philadelphia became the first station to air syndicated reruns of Star Trek. Running at 6 p.m., the show exceeded all expectations, earning far better ratings than it ever had for NBC.

Encouraged, Kaiser rolled out the series to the rest of its stations in 1970 and even hired former cast members to record voice-over plugs for the show. For instance, station WKBF in Cleveland ran a plug in which Leonard Nimoy intoned, “This is Mr. Spock of the starship Enterprise. Logic would dictate that if you are a fan of fast-moving adventure, you’ll stay tuned for Star Trek … coming up next on Channel 61.” Soon, Trek was trouncing local newscasts in the ratings in cities like Boston, Detroit, and, with an assist from Mr. Spock, Cleveland. Kaiser’s success vindicated Gene Roddenberry, who had argued with NBC executives throughout Star Trek’s three network seasons that all his series needed to become a hit was a more favorable time slot.

Owner-operators of independent stations in other markets noted Kaiser’s success and quickly moved to duplicate it, purchasing Star Trek and running it during the dinner hour. In cities without independent stations, many network affiliates purchased the show and ran it at other times of day. Ratings were so good that stations began editing the episodes, removing or shortening minor scenes to free up two or three additional minutes of advertising space. As a result, until the dawn of the home video era, it became difficult to see Star Trek in its original uncut form. In many markets, the show was “stripped,” running five days a week, Monday through Friday. With only seventy-nine episodes, this meant that stations cycled through the repeats quickly, but fans didn’t seem to mind. Even as episodes reran for the third and fourth time, ratings continued to climb in most locations. “Instead of getting bored, fans of Star Trek actually seemed to enjoy watching repeats of our repeats, studying every episode to the point where they not only knew each storyline but most of the dialogue as well,” William Shatner wrote in his book Star Trek Movie Memories. By 1972, Star Trek was running in more than one hundred cities across the U.S. and in fifty-five foreign countries, from Argentina to Zambia.

A Raft of Cons

Star Trek’s previously unimaginable popular resurgence attracted the attention of the mainstream media, who began referring to Trek as “the Show That Wouldn’t Die.” Reporters from the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times News Service, and the Associated Press seemed baffled by the series’ belated success. “Nothing fades faster than a canceled television series they say,” wrote AP reporter Jerry Buck in a March 1972 feature. “So how come Star Trek won’t go away?”

The answer was simple: Star Trek became the Show That Wouldn’t Die because it had the Fans Who Wouldn’t Quit. What’s more, those devotees were uncommonly well organized, thanks in part to mailing lists and other infrastructure created for the letter-writing campaigns of 1967 and ’68. As the show gained popularity in syndication, the old “Save Star Trek” rallying cry morphed into a new mantra: “Star Trek Lives!”

Despite the largely erroneous stereotype of “Trekkies” as wallflowers and misfits, the shows’ fans have always been highly social creatures, and scores of Star Trek fan clubs formed while the series remained in production. In the early 1970s, those groups found many eager new members, and many additional clubs were founded. There is no way to compile a comprehensive tally of all these small, grassroots organizations, but Gerry Turnbull’s 1979 book A Star Trek Catalog provided names and mailing addresses for 279 fan clubs across the U.S, twenty-one Canadian organizations, and twenty other groups scattered from Great Britain to Japan.

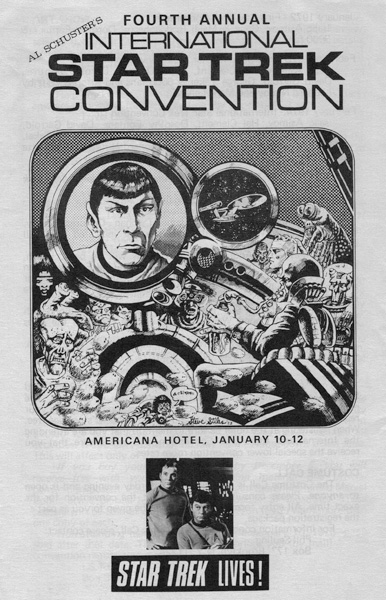

Flyer for the 1975 International Star Trek Convention in New York City.

In 1971, a small group of New York fans (including Joan Winston, who later coauthored the book Star Trek Lives and wrote The Making of the Trek Conventions) pooled their resources, rented space at the Statler Hilton Hotel in Manhattan and launched the first widely publicized Star Trek convention. Organizers lined up Gene Roddenberry, Majel Barrett, Dorothy Fontana, and science fiction author Isaac Asimov to appear at the event and assembled a display of real-life space artifacts provided by NASA. Roddenberry agreed to preside over screenings of the series’ original pilot, “The Cage,” and the soon-to-be-famous Trek blooper reel. The convention, which also featured a costume contest, a fan art show, and a room full of dealers selling Trek souvenirs, was expected to draw 500 patrons. More than 3,000 showed up, overwhelming the Statler Hilton from January 21 through 23, 1972.

Star Trek clubs across the U.S. moved quickly to pull together their own gatherings. Over the course of the next six years, conventions (or “cons,” in fan parlance) were held in Boston, Philadelphia, the District of Columbia, Huntsville, Houston, Dallas, Kansas City, and many other locations, with attendance far exceeding expectations at most events. The New York convention became an annual affair, moving to larger venues (and overfilling them) each year for the first half of the decade. It attracted 6,000 fans in 1973 and 15,000 in 1974. Sixteen thousand fans turned out when the entire cast reunited for the first time for a convention at the Hilton Hotel in Chicago, August 22–24, 1975. The following year, twenty-five Star Trek conventions were held across the U.S. and Canada. Glendale, California–based Creation Entertainment began producing Star Trek conventions at various sites in the early 1970s. (Creation is now the licensed host of the Official Star Trek Convention, held annually in Las Vegas, which attracts over 15,000 fans annually, as well as several smaller events scattered across the country.)

These events helped fans connect with one another in that bygone era prior to Facebook, Twitter, or even e-mail. They helped foster the growing market for Star Trek memorabilia and ephemera. And they provided a steady source of income for former cast members, many of whom fell on hard times in the 1970s. (For more on this, see Chapter 38, “Shore Leave.”) The cons also gave actors such as James Doohan, George Takei, Walter Koenig, and Nichelle Nichols, who earned little recognition while the show was on the air, the chance to bask in the glow of adoring fans.

The Fanzine Phenomenon

One of the hottest-selling items in the dealer’s rooms at the Star Trek cons of the early 1970s were fanzines, fan-written publications with imaginative titles such as Warped Space, Beyond Antares, and Saurian Brandy Digest. The very first Trek zine ever created, Spockanalia, was a one-shot sold at the 1967 Science Fiction WorldCon, where the word “Trekkie” was coined. Four years later, when the first Star Trek convention was held in New York, more than one hundred Trek fanzines were in operation.

These zines varied widely both in appearance—from amateurish, mimeographed booklets with crude black-and-white fan-drawn cover art to professional-looking, custom-printed efforts with full-color cover photos—and in content. Some included interviews with the cast and crew (often transcribed from convention appearances), in-depth reviews of individual episodes, analysis of the show’s philosophical and ethical themes, or explanations of various Treknological devices. However, most of the zines existed solely to publish fan-written fiction. The popularity of this peculiar literary form owed a great deal to simple need: If you were looking for original Star Trek stories in the early ’70s, the fanzines were the only game in town. Writers of fan fiction, according to the authors of Star Trek Lives! (1975), “have become so entranced with that world that they simply cannot bear to let it die and will recreate it themselves if they have to—or given half a chance.”

Like the zines themselves, these stories also varied widely in their quality and nature. A few were worthy of professional publication (and a handful eventually were published in Pocket Books’ Star Trek: The New Voyages anthologies in the late 1970s), but most were clumsy and rough-hewn. Some writers attempted to recreate the kind of idea-driven yet action-packed tales that were the hallmark of Star Trek, delving into characters and concepts introduced but not fully explored in various episodes. Most fan fiction was penned by women and often reflected the romantic fantasies of the author. So-called “Mary Sue” stories, in which the writer introduced a female character (usually a thinly veiled stand-in for the author herself) to serve as a romantic interest for one of the show’s cast members (usually Spock or Kirk) quickly became a fan fiction cliché.

The most controversial tales to emerge from the fanzines were those commonly referred to as “Kirk/Spock,” “K/S,” or simply “slash” fiction, which depicts a homosexual relationship between Captain Kirk and his first officer. Many of these stories employ the Vulcan mating cycle as a plot device, with Kirk and Spock trapped alone on a remote planet (or a similar locale) and Spock suddenly going into pon farr; to save the life of his friend, Kirk must have sex with Spock. Initially, “slash” fiction and other sexually explicit stories were relatively rare, but a hefty percentage of fan fiction written today is sexual in nature, often homo- or sado-erotic.

According to Joan Marie Verba’s self-published Boldly Writing: A Trekker Fan and Zine History, 1967–1987, a meticulously researched history of nonprofessional Trek publications, there were 176 zines in print in 1973. By 1977, the number had grown to 458 publications. Gene Roddenberry tolerated and even encouraged the fan press, despite the fact that every issue represented a blatant violation of his cherished Star Trek copyright. Surprisingly, Paramount also took (and continues to take) a laissez-faire attitude, permitting fans to publish zines, produce artwork, recordings, and even semipro movies as long as these works were produced on a not-for-profit basis. As a result, fan fiction continues to flourish. Although fanzines have faded into memory (most folded in the 1990s), numerous websites now compile and publish fan-written Trek tales free of charge.

Clubs, conventions and zines helped keep fans in contact with one another, and provided a platform for united action toward the primary goal of Trekkers everywhere: the return of Star Trek.

In 1971, the same year as the first Trek convention, the Star Trek Association for Revival (STAR) was formed. Over the course of the next four years, STAR organized various efforts aimed at pressuring Paramount and/or NBC into reviving Star Trek as a TV series or feature film. In its first newsletter, published in May 1972, STAR took a page from the old “Save Star Trek” playbook and urged true believers to write Paramount and NBC to demand the return of Trek. “How often should you write? Would it be difficult for anyone to write one letter a week?” asked the newsletter (reprinted in Boldly Writing). “Then get your friends, cousins, fellow workers, school mates, etc., to write, too. The more letters the better. Let us keep burying Paramount in an avalanche of letters.” Eventually, STAR claimed 160 local chapters and compiled a mailing list with more than 25,000 names and addresses of Star Trek fans across the U.S. But the organization grew too large for its volunteer leadership to manage and disintegrated in late 1975.

By then, however, Paramount had gotten the message, and Star Trek was on its way back. But the voyage home would prove to be long and troubled.

An amusing assortment of vintage 1970s bumper stickers.