The era from 1300 until the later seventeenth century saw the remarkable expansion of the Ottoman state from a tiny, scarcely visible, chiefdom to an empire with vast territories. These dominions stretched from the Arabian peninsula and the cataracts of the Nile in the south, to Basra near the Persian Gulf and the Iranian plateau in the east, along the North African coast nearly to Gibraltar in the west, and to the Ukranian steppe and the walls of Vienna in the north. The period begins with an Ottoman dot on the map and ends with a world empire and its dominions along the Black, Aegean, Mediterranean, Caspian, and Red Seas.

Great events demand explanations: how are we to understand the rise of great empires such as those of Rome, the Inca, the Ming, Alexander, the British, or the Ottomans? How can these world shaking events be explained?

In brief, the Ottomans arose in the context of: Turkish nomadic invasions that shattered central Byzantine state domination in Asia Minor; a Mongol invasion of the Middle East that brought chaos and increased population pressure on the frontiers; Ottoman policies of pragmatism and flexibility that attracted a host of supporters regardless of religion and social rank; and luck, that placed the Ottomans in the geographic spot that controlled nomadic access to the Balkans, thus rallying additional supporters. In this section follows the more detailed story of the origins of the Ottoman state.

The Ottoman Empire was born around the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in the northwestern corner of the Anatolian peninsula, also called Asia Minor (map 1). Extreme confusion – political, cultural, religious, economic, and social – marked the era and the region. For more than a millennium, this area had been part of the Roman Empire and its successor state in the Eastern Mediterranean world, the Byzantine Empire, ruled from Constantinople. Byzantium had once ruled over virtually all of today’s Middle East (except Iran) – the region of modern-day Egypt, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Turkey, and parts of Iraq, as well as parts of southeast Europe, north Africa, and Italy. In the seventh century CE, however, it had lost many of those areas, mostly to the expanding new states based in Mecca, Damascus, and Baghdad. With some difficulty, the Byzantine state then reinvented itself and managed to retain its Anatolian provinces. In its reduced form, the Byzantine Empire faced three sets of enemies. From the Mediterranean, the Venetian and Genoese merchant states fought between themselves and (usually separately) against the Byzantines to gain strongholds and economic concessions on the rich Aegean, Black Sea, and eastern Mediterranean trade routes. To their north and west, the Byzantines faced expansive and powerful land-based states, especially the Bulgarian and Serbian kingdoms. And, beginning at the turn of the first millennium, the Turkish nomads (called Turcoman) appeared on their eastern frontiers. Turkish peoples with their origins in central Asia, in the area around Lake Baikal, began migrating out of these ancestral homes and, c. 1000 CE, started pouring into the Middle East. In their Central Asiatic homes, the Turcoman way of life was marked by shamanist beliefs in religion and economic dependence on animal raising and social values that celebrated personal bravery and considerable freedom and mobility for noble women. The Homeric-style epic, named The Book of Dede Korkut, recounts the stories of heroic men and women, and was written just before the Turcoman expansion into the Middle East. This epic also shows that the Turcoman polity was highly fragmented, with leadership by consensus rather than command. This set of migrations – a major event in world history – created a Turkic speaking belt of men, women, and children from the western borders of China to Asia Minor and led to the formation of the Ottoman state. The nomadic, politically fragmented Turcoman way of life began causing major disturbances in the lives of the settled populations of the Iranian plateau, who bore the brunt of the initial migrations/invasions. As the nomads moved towards and then into the sedentarized Middle East, they converted to Islam but retained many of their shamanist rituals and practices. Hence, Turkish Islam as it became practiced later on varied considerably in form from Iranian or Arab Islam. As they migrated, the Turcomans and their animals disrupted the economy of the settled regions and the flow of tax revenues which agriculturalists paid to their rulers. Among the Turkish nomadic invaders was the Seljuk family. One of many leaders in charge of smaller or larger nomadic groups drifting westward, the Seljuk family seized control of Iran and its agricultural populations, quickly assimilated into its prevailing Perso-Islamic civilization, and then confronted the problem of what to do with their nomadic followers who were disrupting the settled agricultural life of their new kingdom. A solution to the Seljuks’ problem was to be found in Byzantine Anatolia.

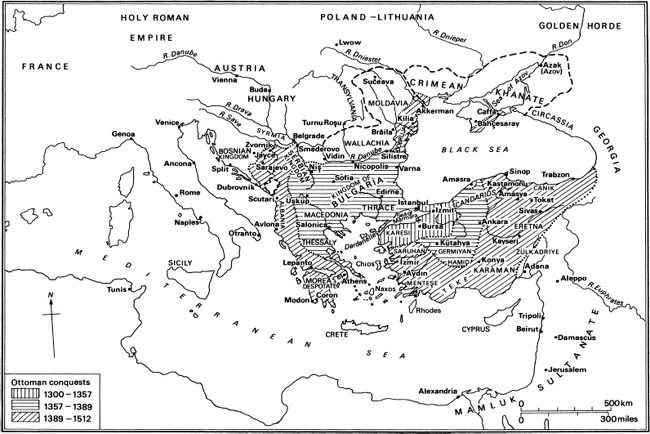

Map 1 The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1512

Adapted from Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), xxxiii.

The provinces of Byzantine Anatolia had two sets of features that seem important here. First, they were productive, heavily populated agrarian settlements and thus for the nomads appeared as very attractive targets of plunder. In a word, the Anatolian provinces were rich. They also were Christian. Therefore they offered doubly justified targets of warfare for these Turkish nomads recently converted to Islam and under the influence of popular preachers who had fused shamanist beliefs with Islam. Was Anatolia attractive to the nomads mainly because it was rich or because it was Christian? Like their crusading Christian contemporaries, the nomads’ motives were a mixture of economic, political, and religious factors. The lands of Anatolia were rich and they were inhabited by (mainly) farmers of another, Christian, faith. For the vast numbers of nomads already in the Middle East, pressured by waves of nomads behind them in central Asia, these were powerful incentives. And so, not long after their entry into Iran, the Turcoman nomads began plundering and raiding the eastern provinces of Byzantium, pulled there by economics, politics, and faith, and pushed there by the centralizing Seljuk rulers of Iran. After enduring the raids for several decades, the central Byzantine state moved to crush the new threat. In 1071, however, the imperial army under the Emperor Romanus Diogenus decisively was crushed at the epochal battle of Manzikert, not far from Lake Van, by the combined military forces of the Turkish nomads temporarily allied with the army of the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan. This spelled the ruin of the imperial border defense system in the east, and Turkish nomads, now nearly unchecked, flooded into Byzantium.

For the next several centuries, until the mid-fifteenth century, the history of Anatolia, east and west, can be understood through the metaphor of islands of sedentarized life under Byzantine imperial and feudal lords struggling to exist in a flood tide of Turkish nomads whose leaders, in turn, came to form their own small states. In the short run, Turcoman principalities rose and fell and Byzantine control ebbed and flowed. Anatolia became a patchwork quilt of tiny Turcoman and Byzantine principalities and statelets, expanding and contracting. At times, Byzantine leaders, imperial and feudal, resisted more or less successfully. But inexorably, in the long run, Byzantine Christian, predominantly Greek-speaking, Anatolia underwent a profound transformation and over time became Turkish speaking and Muslim. This general atmosphere of confusion, indeed chaos, played a crucial role in the emergence of the Ottoman state. In the midst of the Turcoman invasions, the beleaguered Byzantines also were fighting against the Italian merchant states, losing to them chunks of land and other economic assets such as trade monopolies. Between 1204 and 1261, moreover, Constantinople became the capital of the erstwhile Crusaders, who instead of marching to Palestine, seized and sacked the riches of the imperial city and established their short-lived Latin Christian empire. Historians agree that the 1204 sack of the city struck a blow from which Constantinople never recovered.

The specific context in which the Ottoman state emerged also is linked to the rise of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan, its rapid expansion east and west, and its push into the Middle East during the thirteenth century. As the Mongol state expanded, it often accelerated the movement of Turkish nomads, who fled before it into areas that could support their numbers and their livestock. In the middle of the thirteenth century a Mongol general warred on a Seljuk state which had been established at Konya in central Anatolia. This Mongol victory wrecked the relatively large Seljuk sultanate there, which, before the Ottomans, had been the most successful state founded in post-Byzantine Anatolia, and triggered the rise of a number of small Turcoman principalities in its stead. The Mongol presence also prompted the flight of Turcoman nomads who sought pasture lands in the west. These were the border regions of the collapsing Seljuk state on the one hand and the crumbling Byzantine world on the other. This was a changing world, full of Serb and Bulgarian, Genoese and Venetian invaders and of Turkish Muslim nomads and Byzantine Greek Christian peasants. In these Anatolian highlands to the south and east of Byzantine Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire was born.

Historians who are Ottoman specialists like to argue about which was the most important single variable explaining the rise of this extraordinary empire. The question is a fair one since the founder of the dynasty after whom it was named, Osman, was just one of many leaders and not the most powerful, among the various and sundry Turcoman groups on the frontier. Looking down on this world in the year 1300, it would have been impossible to predict that his would be among the most successful states in history. At the time, Osman was in charge of some 40,000 tents of Turcoman nomads. Some of his Turkish-speaking rivals in other parts of the frontier were vastly more successful and commanded 70,000 and 100,000 tents (with two to five persons per tent). There were scores of other Turcoman principalities. All were part of a larger process in which Turcoman nomads of the Anatolian highlands pressed upon and finally occupied the valleys and the coastal plains. Alone among these, the dynasty of Osman triumphed while the others soon disappeared.

Osman and his followers, along with the other Turcoman leaders and groups, surely benefited from the confusion throughout Anatolia, especially in the borderland (as later Ottoman rulers would profit from political disintegration in the Balkans). Turkish nomadic incursions, commonly spontaneous and undirected, toppled local administrations and threw the prevailing political and economic order of Anatolia into confusion. The Mongol thrusts accelerated these movements which, altogether, seem to have built up considerable population pressures in the frontier zones. Warrior bands like Osman’s flourished both because they could prey on settled populations and because their strength offered adherents a safety that governments seemed unable to provide. Such warrior encampments became an important form of political organization in thirteenth-century Anatolia.

Ottoman success in forming a state certainly was due to an exceptional flexibility, a readiness and ability to pragmatically adapt to changing conditions. The emerging Ottoman dynasty, that traced descent through the male line, was Turkish in origins, emerging in a highly heterogeneous zone populated by Christians and Muslims, Turkish and Greek speakers. Muslims and Christians alike from Anatolia and beyond flocked to the Ottoman standard for the economic benefits to be won. The Ottoman rulers also attracted some followers because of their self-appointed role as gazis, warriors for the faith fighting against the Christians. But the power of this appeal to religion must be questioned since, at the very same moment, the Ottomans were recruiting large numbers of Greek Christian military commanders and rank-and-file soldiery into their growing military force. Thus, many Christians as well as Muslims followed the Ottomans not for God but for gold and glory – for the riches to be gained, the positions and power to be won.

Another argument against identifying the Ottoman state primarily as a religious one rests in the reality that Ottoman energies focused not only on fighting neighboring Byzantine feudal lords but also, from earliest times, other Turcoman leaders. Indeed, the Ottomans regularly warred against Turcoman principalities in Anatolia during the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. Despite their severity and frequency, the Ottoman wars with Turcomans often have been overlooked because historians’ attention has been on the Ottoman attacks on Europe and on inappropriately casting the Ottomans’ role primarily as warriors for the faith (gazi) rather than as state builders. Rival Turcoman dynasties – such as the Karaman and the Germiyan in Anatolia or the Timurids in central Asia – were formidable enemies and grave threats to the Ottoman state. From the beginning, Ottoman expansion was multi-directional – aimed not only west and northwest against Christian Byzantine and Balkan lands and rulers but always east and south as well, against rival Muslim Turcoman political systems. Thus, what seems crucial about the Ottomans was not their gazi or religious nature, although they sometimes had this appeal. Rather, what seems most striking about the Ottoman enterprise was its character as a state in the process of formation, of becoming, and of doing what was necessary to attract and retain followers. To put it more explicitly, this Ottoman enterprise was not a religious state in the making but rather a pragmatic, dynastic one. In this respect, it was no different from other contemporary states, such as those in England, Hungary, France, or China.

Geography played an important role in the rise of the Ottomans. Other leaders on the frontiers perhaps were similar to the Ottomans in their adaptiveness to conditions, in their willingness to utilize talent, to accept allegiance from many sources, and to make multi-sided appeals for support. At this distance in time it is difficult to judge how exceptional the Ottomans may have been in this regard. But when considering the reasons for Ottoman success we can point with more certainty to an event that occurred in 1354 – the Ottoman occupation of a town (Tzympe), on the European side of the Dardanelles, one of the three waterways that divide Europe and Asia (the others being the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara). Possession of the town gave the Ottomans a secure bridgehead in the Balkans, a territorial launching pad that instantly propelled the Ottomans ahead of their frontier rivals in Anatolia. With this possession, the Ottomans offered potential supporters vast new fields of enrichment – the Balkan lands – that simply were unavailable to the followers of other dynasts or chieftains on the other, Asiatic, side of the narrow waters. These lands were rich and at that time were empty of Turcomans. Appeals to action also could be made in the name of ideology – of war for the faith.

Thus, the earlier riches and political turmoil of Byzantine Anatolia were paralleled by the riches and turmoil of the fourteenth-century Balkans. Forces similar to those that earlier had brought the Turcomans into Byzantine Anatolia now brought the Ottomans and the nomads into the Balkans. The Balkans offered a relief valve for the population pressures building in western Asia Minor, and the Ottomans alone offered access to it. Ironically, the Ottoman crossover into Europe happened because of the ambitions of a Byzantine pretender to the Constantinople throne. Caught in a civil war, he granted the Ottomans this foothold in a new continent as a means of cementing their support. Irony compounded irony since the Ottomans then used their alliance with Genoa, a sometime enemy of the Byzantines, to expand their newly gained but precarious European holdings.

Like Anatolia in c. 1000 CE, the Balkans in the fourteenth century offered rich and vulnerable prizes ready for the taking. State building efforts in both the Bulgarian and Serbian areas had collapsed; the Byzantines were in a civil war as rival claimants fought one another for the imperial crown; and Venice and Genoa each moved to take advantage of the confusion. And so, a combination of flexibility, skilled policies, good luck, and good geography contributed to the Ottomans’ ability to break out onto the path of world empire and gain supremacy over their rivals. Already successful, their crossing into the Balkans vaulted them into a new position with unparalleled advantages.

From their beginnings in western Anatolia, the Ottoman state in the following centuries expanded steadily in a nearly unceasing series of successful wars that brought it vast territories at the junction of the European, Asian, and African continents. Before turning to the factors which explain the Ottomans’ expansion from their initial west Anatolian–Balkan base, we need to briefly enumerate these victories (map 2).

Usually, historians like to point to the reigns of two sultans – Mehmet II (1451–1481) and Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566) – as particularly impressive. Each built on the extraordinary achievements of his predecessors. In the 100 plus years before Sultan Mehmet II assumed the throne, the Ottomans expanded deep into the Balkan and Anatolian lands. By the time of their crossover from west Anatolia into the Balkans, the Ottomans already had seized the important Byzantine city of Bursa and made it the capital of their expanding state. In 1361 they captured Adrianople (Edirne) in Europe, a major Byzantine city that became the new Ottoman capital, and used it as a major staging area for offensives into the Balkans. Less than half a lifetime later, in 1389, Ottoman forces annihilated their Serbian foes at Kossovo, in the western Balkans. After 1989, the reinvented memory of Kossovo became a powerful catalyst to the formation of modern Serbian identity. This great victory was followed by others, for example, the capture of Salonica from the Venetians in 1430. At Nicopolis in 1396 and Varna in 1444, the Ottomans defeated wide-ranging coalitions of west and central European states that were becoming painfully aware of the expanding Ottoman state and the increasing danger it posed to them. The international aspect of these battles was marked by the presence of forces from not only Serbia, Wallachia, Bosnia, Hungary, and Poland, but also, for example, France, the German states, Scotland, Burgundy, Flanders, Lombardy, and Savoy. Scholars have considered Nicopolis and Varna as latter day Crusades, the continuation of eleventh-century European efforts to destroy local states in Palestine. And yet, at both battles (see below), Balkan princes were present who fought on the Ottoman side while Venice, at Nicopolis, negotiated with each side to gain commercial and political advantage.

So, when Mehmet the Conqueror took power, he had a strong foundation on which to build. Just two years later, in 1453, he fulfilled the long-standing Ottoman and Muslim dream of seizing thousand-year-old Constantinople, city of the Caesars. Mehmet immediately began restoring the city to its former glories; by 1478, the population had doubled from 30,000 living in villages scattered inside of the massive fortifications to 70,000 inhabitants. A century later, this great capital would boast over 400,000 residents. Mehmet’s conquests continued and, between 1459 and 1461, he brought under Ottoman domination the last fragments of Byzantium in the Morea (southern Greece) and at Trabzon on the Black Sea; he also annexed the southern Crimea and established a long-standing set of ties with the Crimean khans, successors of the Mongols who earlier had conquered the region. For a time, perhaps as part of a plan to conquer Rome, his armies occupied Otranto on the heel of the Italian peninsula. But the effort failed, as did his siege of Rhodes, an island bastion of a crusading order of knights.

Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent had the good fortune of succeeding Selim I (1512–1520). In his short reign, Selim had thoroughly beaten a newly emergent foe, the Safevid state on the battlefield of Çaldıran in 1514. (The Safevids, a Turkish-speaking dynasty who had acquired an Islamic and Persian identity, became the major opponent on the Ottoman eastern frontiers during the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries.) Selim then (1516–1517) conquered the Arab lands of the Mamluk sultanate based in Cairo, filling the treasury and bringing the Muslim Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina under the Ottoman rulers’ dominion. During the long reign of Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566) the Ottomans enjoyed considerable power and wealth. Under Süleyman’s leadership, the Ottomans fought a sixteenth-century world war. Sultan Süleyman supported Dutch rebels against their Spanish overlords while his navy battled in the western Mediterranean against the Spanish Habsburgs. At one point, Ottoman troops wintered on the modern-day Riviera at Toulon, by courtesy of King Francis I of France who also was fighting against the Habsburgs (see chapter 5). On the other side of their world, Ottoman navies warred in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, as far east as modern-day Indonesia. There they fought because the global balance of power and wealth had been overturned by the Portuguese voyages of discovery around Africa, that opened all-water routes between India and south and southeast Asia. These new passages threatened to destroy a transit trade that Middle Eastern regimes for many centuries had dominated and profited from. To loosen the mounting Portuguese (and later Dutch and English) chokehold on this trade and break its growing dominance of the all-water routes, the Ottomans launched a series of offensives in the eastern seas. For example, they aided local rulers on the India coast who were fighting the Portuguese and sent fleets to aid the Moluccans (near modern Singapore) who were struggling to break mounting European maritime domination. On the Balkan fronts, Sultan Süleyman’s forces similarly moved to impose Ottoman domination over trade routes, rich mines and other economic resources. In an important series of victories, the Ottomans seized Belgrade in 1521, crushed the Hungarian state at the battle of Mohács in 1526 and later (in 1544) annexed part of it. In 1529, Ottoman troops stood outside the walls of Habsburg Vienna, which neither they nor their successors in 1683 were able effectively to breach. By this date the Istanbul-based state stood astride the rich trade routes linking the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to east and central Europe. Thus both Venice and Genoa suffered grievous blows, losing the wealth and power that the trade routes and colonies of these regions had brought them.

Map 2 The Ottoman Empire, c. 1550

Adapted from Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), xxxiv.

If the phrase “expansion” aptly depicts the overall Ottoman military and political experiences until the later sixteenth century, then “consolidation” likely best summarizes the situation during the subsequent century or so. Following Süleyman’s death, Ottoman victories continued but less frequently than before. The great island of Cyprus with its fertile lands became an Ottoman possession in 1571, bolstering Istanbul’s dominance over the sea routes of the eastern Mediterranean. The Europeans’ naval victory at Lepanto in 1571 and utter destruction of the Ottoman navy, one of the greatest in the Mediterranean at the time, proved ephemeral. The next year a new fleet re-established Ottoman dominion in the eastern Mediterranean, the locale of their recent defeat. On land, Ottoman armies captured Azerbaijan between 1578 and 1590 and regained Baghdad in 1638. Crete, the largest of the eastern Mediterranean islands after Cyprus, was incorporated into the state in 1669, followed by Podolia in 1676.

Not every battle was a victory but the overall record until the later seventeenth century was a successful one, bringing more extensive frontiers containing new treasures, taxes and populations. By the later seventeenth century, Ottoman garrisons overlooked the Russian steppe, the Hungarian plain, the Saharan and Syrian deserts, and the mountain fastness of the Caucasus. Ottoman military forces had achieved virtually full dominion over the entire Black Sea, Aegean, and eastern Mediterranean basins, including most or all of the drainages of the Danube, Dniester, Dnieper, and Bug rivers, as well as the Tigris–Euphrates and the Nile. Thus, the trade routes and resources that had supported Rome and Byzantium, but then had been divided among the warring states of Venice, Genoa, Serbia, Bulgaria, and others, now belonged to a single imperial system.

Describing victories is much easier than explaining why they happened. The Ottomans certainly profited from the weaknesses and confusion of their enemies. For example, their ability to expand against the Byzantines in part must be credited to the enduring harm done to Byzantium by the terrible events in 1204. At that time, Venetians and other Crusaders occupied Constantinople and plundered it so ruthlessly that Byzantium never regained its former strength. Also, consider the bitter rivalries among and warring between the most powerful states in the eastern Mediterranean – Venice, Byzantium, and Genoa. In addition, the decline of the feudal order, c. 1350–1450, left many states in shambles both militarily and politically. Thus, the collapse of the once-powerful Serbian and Bulgarian kingdoms at the very moment of Ottoman expansion into the Balkans left the road open to the invaders. Then there is the matter of the eruption of the Black Death in 1348. Here, historians like to argue that the plague most heavily affected urban populations, relatively sparing the Ottomans and softening their mainly urban enemies. To counter this point, it must be said that we have no evidence on how horribly the plague struck the populous Ottoman encampments or the towns and cities (such as Bursa, Iznik, and Izmit) already under their control. Moreover, such arguments ignore the repeated and terrible plague outbreaks that later wracked Ottoman cities and, notably, undermined Mehmet the Conqueror’s efforts to repopulate Ottoman Constantinople. Such emphases on the divisions and weaknesses of enemies and the impact of the plague underscore good fortune and downplay Ottoman achievements by attributing success to factors outside of their control.

It seems more useful to examine Ottoman policies and achievements – emphasizing what they achieved by their own efforts – rather than the mere luck they enjoyed because of their enemies’ problems. In this analysis, stress is upon the character of the Ottoman enterprise as a dynastic state, not dissimilar from European or Asian contemporaries such as the Ming in China or England and France during the time of the Wars of the Roses. Like most other dynasties in recorded history, the Ottomans relied exclusively on male heirs to perpetuate their rule (see chapter 6). In the formal political structure of the emerging state, women nonetheless sometimes are visible. For example, Nilufer, wife of the second Ottoman ruler, Sultan Orhan (1324–1362), served as governor of a newly conquered city. Such formal roles for women, however, seem uncommon. More usually, later Ottoman history makes it clear that the wives, mothers, and daughters of the dynasty and other leading families wielded power, influencing and making policy through informal channels. For the early period, c. 1300–1683, we do know that, in common with many other dynasties, the Ottomans frequently used marriage to consolidate or extend power. For example, Sultan Orhan married the daughter of a pretender to the Byzantine throne, John Cantacuzene, and received the strategically vital Gallipoli peninsula to boot. Sultan Murat I married the daughter of the Bulgarian king Sisman in 1376, while Bayezit I married the daughter of Lazar (son of the Serbian monarch Stephen Duşan) after the battle of Kossovo. Such marriages hardly were confined to the Christian neighbors of the Ottomans but often were with other Muslim dynasties as well. For example, Prince Bayezit, on the arrangement of his father Murat I, married the daughter of the Turcoman ruler of Germiyan in Anatolia and obtained one-half of his lands as dowry. Bayezit II (1481–1512) married into the family of Dulkadirid rulers of east Anatolia, in the last known case of marriage between the Ottomans and another dynasty.

Another important key to understanding Ottoman success is to look at the methods of conquest. Here, as in the realm of marriage politics, we encounter a flexible, pragmatic group of state makers. The Ottoman rulers at first often allied with neighbors on the basis of equality, sometimes cementing a relationship with marriage. Then, frequently, as the Ottomans became more powerful, they established a loose overlordship, often involving a type of vassalage over the former ally. Thus, local rulers – whether Byzantine princes, Bulgarian and Serbian kings, or tribal chieftains – accepted the status of vassals to the Ottoman sultan, acknowledging him as a superior to whom loyalty was due. In such cases, the newly subordinated vassals often continued with their previous titles and positions but nevertheless owed allegiance to another monarch. These patterns of changing relations with neighbors are evident from the earliest days and continued for centuries. Thus, for example, the founder Osman first allied with neighboring rulers, then made them his vassals, bound to him by ties of loyalty and obedience. During the latter part of the fourteenth century the Byzantine emperor himself was an Ottoman vassal, as were Bulgarian and Serbian princes, as well as the Karaman ruler from Anatolia. At Kossovo in 1389, Ottoman supporters on the battlefield included a Bulgarian prince, lesser Serb princes, and some Turcoman rulers from Anatolia. In many cases, patterns of equality between rulers gave way to vassalage and finally direct annexation. A sharp example of this final phase is 1453, when the relationship between the Ottoman and Byzantine empires completed its evolution from equality to vassalage to subordination and destruction. As Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror defeated the Byzantine emperor he not only destroyed the Byzantine Empire but also the vassal relationship which had existed, now bringing the dead emperor’s state under direct Ottoman administration. Similarly, Sultan Mehmet ended the alliance and vassal relationships with the Turcoman rulers of Anatolia and brought them under direct Ottoman control. In the early sixteenth century, to give another example, the Ottomans first ruled Hungary as a vassal state but then annexed it to more effectively govern the frontier.

There was not, however, always a linear progression from alliance to vassalage to incorporation. Sultan Bayezit II (1481–1512), for example, reversed his father’s policies and restored Turcoman autonomy (but it is true that his turnabout in turn was reversed). After c. 1550, local dynasties (elected or approved in some fashion by their nobles) retained their power in several areas north of the Danube, notably, Moldavia, Wallachia as well as Transylvania. In all three regions, these rulers professed allegiance to the sultan and paid tribute while, in the first two areas but not the third, Ottoman garrisons were present. Otherwise, there were few other traces of Ottoman rule; significantly, for example, no mosques were built. But these tribute payers served at the pleasure of the sultan and were obliged to provide troops on his demand. In a different form, native rule also held at Dubrovnik (Ragusa) on the Adriatic. The tradition of local rule in Moldavia and Wallachia, endured until just after the 1710–11 Ottoman campaign against Russia, ending because of the alleged “treachery” of the princes. The Ottomans’ relationship with the Crimean khans is still more fascinating. These descendants of the Golden Horde (the Mongols of the Russian regions) became vassals of the Ottoman sultans in 1475 and remained so until 1774, when that tie was severed as a prelude to their annexation by the Czarist state in 1783 (see chapter 3). Throughout, they also were considered as heirs to the Istanbul throne in the event the Ottoman dynasty became extinct.

These examples from Transylvania, Moldavia, Wallachia, Dubrovnik and the Crimea thus show alliance or vassalage relationships rather than annexation continuing for centuries after the main thrust of the Ottoman conquests was over. The main trend between 1300 and 1550 nonetheless is of growing direct Ottoman control over neighboring lands. Thereafter, until the end of the empire, Ottoman methods of rule continued to evolve, into new and fascinating forms (see chapter 6).

As the Ottoman state imposed its direct control over an area – whether Anatolia, the Arab provinces or the southern or the northern Balkans – its rule usually worked to the economic advantage of the newly conquered or subordinated populations. The weakening or end of Byzantine central control in Anatolia and the Balkans often had meant the rise of Byzantine feudal or feudal-like lords who imposed brutally heavy tax burdens. Under the Ottomans, these trends were reversed; Ottoman officials took back under central state control many of the lands and revenues which had slipped into the hands of local lords and monasteries. Overall, the new Ottoman subjects found themselves rendering fewer taxes than they had to the officials of rulers preceding the Ottomans.

From not later than the end of the fourteenth century and into the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, officials carried out careful surveys that enumerated all of the taxable resources of an area, immediately after the imposition of direct Ottoman control (but not in tributary areas such as Moldavia and Wallachia). An appointed official (a Christian one did the counting in an early fifteenth-century Albanian case) went from village to village: he enumerated the households and livestock, measured the land, its fertility, productivity and use – the kinds of crops, vineyards, and orchards – and recorded the information in account books (tahrir defterleri). He also counted the population – not every man, woman, and child but the people that mattered to the state, thus the tax-paying head of the household and males old enough to serve in the military.

Having inventoried its landed resources, the state apportioned their tax revenues out to Ottoman military and administrators in the form of timars – fiscal administrative units producing a certain level of tax revenue (originally, the timar was 20,000 guruş in value). Recipients of timar revenue sources were allowed to collect the tax revenues of the timar. The more crucial the service rendered by the timar holder, the greater the amount of the tax revenues he received the right to collect. The basic timar tax revenue was the amount of money considered necessary to maintain a cavalryman and his horse for a year. These cavalrymen fought during the war season (spring and summer), and then returned from campaigning to administer the holdings. Sections of the empire in the Balkans and Anatolia thus were divided into basic timar units. The physical size of the land set aside as a timar varied – in a more fertile area, the timar would be smaller in size since it was more productive; but in less fertile areas a larger amount of land was needed to provide the necessary amount of money. More valuable revenue units (in effect multiple timars each with a different Ottoman name) supported military commanders and higher-ranking government officials.

Such fiscal practices were common among so-called “pre-modern” states, which granted the use of revenue sources in exchange for services rendered (unlike contemporary states today which pay their officials in cash). Only the tax revenues from the land or resource were granted, not the land or resource itself. The whole timar concept was based on the practices of ancient Near Eastern priest kings who administered the lands in the name of the gods. All the land thus belonged to the (priest) king, who allowed others to use its revenues in exchange for services to the king. In Ottoman times the timar method granted tax revenues to the (sipahi) cavalry who were the backbone of the early Ottoman military forces, a large proportion of the warriors fighting on the battlefield. (There were Christian timar holders in Sultan Bayezit II’s time (1481–1512) and they sometimes formed more than one-half of all “timariots”; but over time Christian timar holders gradually disappeared.) Sipahi soldiers had reason to favor conquests since the revenues of the new lands would become timars which they would gain. Similarly, such soldiers profited as the Ottoman dynasty’s relations with neighbors moved from alliance to vassalage to direct administration. For example, the revenues of the lands of the Bulgarian king ultimately were taken over, carved up, and turned over to the Ottoman military. Originally, moreover, the state sought to keep better control by promoting the frequent turnover of timar holders, thus reducing the chance these individuals would develop local roots.

Efforts to block the emergence of such local power nodes notwithstanding, timars in the Balkan lands sometimes nevertheless went to the lords and monasteries which once had owned them. In Anatolia, similarly, many tribal leaders obtained the taxes of their tribes as timars. These examples reveal a state unable to fully impose control, one compelled to negotiate and not simply command the loyalty of the local elites.

Until the early sixteenth century most newly won revenue sources, especially lands in the Balkans and Anatolia, became timar holdings. But, when the Arab regions fell to the Ottomans in 1516–1517, the central state organized their revenues as tax farms (iltizam), a fiscal device which already existed on a small scale elsewhere in the empire. Chronically short of cash because of the difficulty of collecting cash taxes directly, pre-modern states across the globe routinely used tax farms. In tax farming, the state held auctions at specific times and places for the right to collect the taxes of a district, the annual value of which officials already had determined. The highest bidder paid the state in cash at the auction or soon thereafter. Armed with state authorization, the tax farmer went to the assigned area and, accompanied by state military personnel, collected the taxes. After deducting expenses, the tax farmer retained the difference between the tax farm bid and the sums actually collected.

From the sixteenth century, timars over time gave way increasingly to tax farms because the cash needs of the state were mounting. The state bureaucracy was becoming steadily larger, in part because the empire itself was bigger and also because of changes in the nature of the state (chapter 6). Increasingly complex warfare for its part demanded more cash. Until the sixteenth century, the sipahi cavalry armed with bows and lances had formed the core of the military, being tactically and numerically its most vital component, and supported by timars. In a development with fourteenth- and fifteenth-century roots, a standing fire-armed infantry replaced cavalry as the crucial battlefield element. Vastly more expensive to maintain, this infantry required large cash infusions that tax farms but not timars provided.

The rising importance of firearms – the product of a remarkable openness to technological innovation – also helps to explain Ottoman successes in the centuries after 1300. For several hundred years Ottoman armies used firearms on a vaster scale, more effectively, and earlier than competing dynasties. In the great Ottoman victories of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and early sixteenth centuries, technological superiority often played a key role. Cannon and fire-armed infantry were developed at very early dates and used to massive technological advantage in the Balkan as well as the Safevid wars. These firearms required a long training and discipline that often were incompatible with nomadic life. In many cultures, including the Ottoman, cavalry prevented or retarded the use of guns that took a long time to reload and grated on the warrior ethic of bravery and courage demonstrated through hand-to-hand combat. Further, sultans used newly created fire-armed troops in domestic power struggles against timar forces that were insufficiently docile. As firearms became more important, the cavalry and its timar financial base became decreasingly relevant.

The rising importance of firearms is linked to another factor in the Ottoman success story, the devşirme, or the so-called child levy system. This system had its origins in the era of Sultans Bayezit I, Murat I, and Mehmet II. Until the early seventeenth century, recruiting officials went to Christian villages in Anatolia and the Balkans as well as to Muslim communities in Bosnia on a regular basis. They assembled all the male children and selected the best and the brightest. These recruits then were taken from their village homes to the Ottoman capital or other administrative centers. There, in the so-called palace school system, they received the best years-long mental and physical education that the state could provide, including religious training and, as a matter of course, conversion to Islam. The crème de la crème of this group entered the state elites, becoming officers and administrators. Many rose to become commanders and grand viziers and played a distinguished role in Ottoman history. The others became members of the famed Janissary corps, an extraordinarily well-trained, fire-armed, infantry center of armies that won many victories in the early Ottoman centuries. The Janissaries for centuries technologically were the best-trained, best-armed fighting force in the Mediterranean world.

The devşirme system offered extreme social mobility for males, allowing peasant boys to rise to the highest military and administrative positions in the empire, except for the dynasty itself. Significantly, it served as a means for the empire to tap into the manpower resources of its numerous Christian subject populations. As the Ottoman state had matured during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and placed greater emphasis on its Islamic character, the military and bureaucratic service of unconverted Christians became more problematic. And so the earlier use of Christians to make the land usage surveys faded away as did the appointment of Christian timar holders. However, while such formal appointments of Ottoman Christians faded, imperial conquests in the Balkans mounted and Christians came to form a more important proportion of the total Ottoman subject populations than before. According to Islamic law, which the Ottoman administration claimed to uphold, the state could not compel the conversion of its own Christian subjects to Islam. The state’s primary concerns, however, were not religious but rather political: to maintain and extend its power by whatever means necessary. Such considerations, so-called “reasons of state” (see chapter 6), therefore prevailed and, through an interpretive nicety, the devşirme system was retained as a legitimate state institution.

Although striking in our eyes, the devşirme system of reaching across religious boundaries had precedents in the Judaic and Christian experiences. In western Europe, as Christianity had solidified its hold on the later Roman period, it had become unacceptable for Christians to enslave other Christians. Hence, when the Slavs became Christian, west Europe turned to Africa and the Black Sea regions for slaves. Jewish merchants, because of the principle of not charging interest to coreligionists, preferred to lend money to non-Jews. Similarly, the Ottomans found trained soldiers and administrators in the same manner as had the Christian slavers and Jewish merchants, by reaching outside their own religious constituencies.

Between c. 1300 and the end of the seventeenth century, the state underwent a quite radical evolution both in its form and in the concentration of power within the administrative apparatus. In the earlier part of the period, 1300–1453, the elites were frontier lords (beys), Turcoman leaders, and princes; and these leaders considered the Ottoman monarch as first among equals (primus inter pares). Entering Ottoman service with retinues, troops, and adherents independent of the sultans’, these elites followed the Ottomans because such allegiance brought them still more power and wealth. The sultan, for his part, negotiated with these nearly equal elites rather than commanding them. At the same time, however, a powerful countervailing trend was developing, one that placed the sultan far above all others in rank and prestige. Some individuals who promoted sultanic superiority were creatures of the monarchs on whom they depended for position and power. But others were religious and legal scholars who invoked Islamic precedents. Already in the early fourteenth century, legal scholars were advocating that bureaucratic leaders and military commanders, despite their vast power, were in fact mere slaves of the sultan. They were not slaves in the American sense since they possessed and bequeathed property, married at will, and moved about freely. In a particularly Ottoman sense, however, being a servant/slave of the sultan meant enjoying privilege and power but without the protection of the law that all Ottoman subjects in principle possessed. From the early fourteenth century, the theory already was evolving – hotly contested by the old elites – that the sultan was no mere Turcoman ruler surrounded by near equals but rather a theoretically absolute monarch. The struggle went back and forth but Sultan Mehmet II, armed with vast prestige after his conquest of Constantinople in 1453, stripped away wealth and power from many of the great Turcoman leaders who often had been independent of him. Now enacting the theory of absolute power, Sultan Mehmet installed his own men, often recruited from the devşirme, persons who in theory were totally indebted to him and over whom he exercised full control. Thus 1453 marked a visible power shift to the person of the ruler. Thereafter, until the nineteenth century, the sultan possessed theoretically absolute power, with life and death control over his military and bureaucratic elites.

In reality, however, the sultan’s power varied greatly over time. For a century following the capture of Constantinople, the sultan exercised a fairly full measure of personal rule. Thus, during the 1453–1550 era, the notion of the exalted, secluded, monarch superior to all took hold while the sultan exercised a very personal kind of control over the military and bureaucratic system. Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (like Philip II of Spain) spent his reign assiduously poring over the record books of his empire and personally leading armies to war.

During the century spanning the reigns of Sultans Mehmet and Süleyman, some sense of an “Ottoman Empire” perhaps began to emerge among administrators and subjects. Although the frontiers were still expanding, a general sense was developing of living in the sultan’s world, of being in the sultan’s lands as opposed to those, for example, of the Habsburg king or the Safevid shah. At its most fundamental, those within received the sultan’s protection from enemies and those outside were attacked by him. But more was involved. The sense of being inside of an Ottoman commonwealth in part also derived from the innumerable actions of the sultan to cement subjects’ loyalties (chapter 6). On another level, the regularization of taxes and the repeated appearances of Ottoman officials on the local scene similarly reinforced subjects’ sense of belonging to the same universe. Moreover, both Mehmet and Süleyman promulgated codes of law which set the sultanic standards, the norms, for behavior. Thus, the presence of a common system of justice, taxes, and a shared ruler who offered protection to every subject served to foster the wider sense of participating in a common “Ottoman” project. This was no small achievement and helps to explain the longevity of the Ottoman Empire.

Let us return now to the narrative of evolving political power within the state. The evolution that exalted the power of the sultan, described above, continued. Thus, later in the reign of Sultan Süleyman, power began passing from the person of the monarch to others in his household. Generally, this sultan’s reign ended a nearly unbroken line of warrior kings going back to the founder of the Ottoman Empire. In this maturing empire, statecraft was changing as the wars of conquest slowed and then halted. As expansion faltered, administrative skills of both men and women became more important than those of the warrior: not fighting sultans but legitimizing sultans were needed. Hence, between the later sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries, the mothers and wives of sultans came more visibly to the fore in decision-making, wielding considerable if still informal political power. In the seventeenth century actual control rested only rarely in the hands of the monarch who, overall, reigned but did not rule. Sultan Murat IV, unusually for a seventeenth-century ruler, personally commanded during the latter part of his 1623–1640 reign. But during the earlier years his mother, Kösem, ably restored the state’s finances after a period of severe inflation. Overall, sultans who actually ran the military and the state faded from Ottoman history until the nineteenth century and the reigns of Sultan Mahmut II and Abdülhamit II. Sultan Mehmet IV (1648–1687) could be sultan although a child because he was not needed to actually rule. Instead, he served as a symbol of a system that functioned in his name. Power rested with his mother (the same Kösem) and other members of his household and, by that date, with members of important Istanbul households outside of the palace. Thus, between c. 1550 and 1650, policy-making and implementation shifted away from the sultanic person; but the central state in its Istanbul capital still directed affairs.

The state apparatus continued its intensive transformation during the seventeenth century. First of all, as seen, sultans became reigning not ruling monarchs who legitimized bureaucratic commands but themselves usually did not initiate policy. For example, during the second half of the seventeenth century (1656–1691), the remarkable Köprülü family truly directed state affairs, often serving as chief ministers (grand viziers). Second, by 1650, new elite groups in Istanbul outside the military (sipahi and askeri) classes, called vizier and pasha households, began making sultans and running affairs. A new collective leadership – a civilian oligarchy – had emerged and the sultans provided the facade of continuity as new practices in fact were replacing old ones. The central state, it is true, still commanded but others besides the ruler were in charge. This was the opposite of events in western and central Europe where monarchs were consolidating power.

These vizier and pasha households had new fiscal underpinnings, sources of wealth autonomous of the state that included, after 1695, lifetime tax farms as well as illegal seizures of state lands. Also important were the revenues based on the so-called pious foundations. These foundations (vakif or waqf) played a vital role in the economic life of Ottoman and other Islamic societies. These were sources of revenues set aside by male and female donors for pious purposes, such as the maintenance of a mosque, school (medrese), students, soup kitchen, library or orphanage. The revenue source might be cultivable lands or, perhaps, shops and stores. The donor prepared a document that turned over the land or shop to the foundation. Properly speaking, immediately upon formation of the foundation or on the death of the donor, the revenues would begin flowing to the intended purpose. But another form of foundation emerged, in which the revenues nominally were set aside for the pious purpose but in reality continued to go to the donors and their heirs under various and dubiously legal pretexts. Pious foundations (even such shady ones) could not be confiscated because of the provisions of Islamic law, jealously guarded by the religious scholars, the ulema. Thus, they offered a revenue source that was secure in a way that wealth from timars or tax farms could never be. Tax farms and timars derived directly from state action and therefore could be taken back from the holder in a moment. Pious foundation revenues, however, did not and were safe from confiscation. Setting up such a pious foundation meant that the possessions of a person – who as a member of the bureaucratic or military elite theoretically was the slave of the sultan – could not be seized, a remarkable turn of events in Ottoman history. During the sixteenth century, pious foundations had been the preserve of the state and the prerogative of those under sultanic control. But, by the eighteenth century, this monopoly of access had faded and the formation of pious foundations had spread to newly emergent groups. This was part of the process that weakened the power of the sultans. The financial security which these foundations offered likely stabilized the respective positions of the vizier and pasha households and of the ulema as the new economic and political power forces of the late seventeenth century.

Entries marked with a * designate recommended readings for new students of the subject.

*Abou-El-Haj, Rifaat. The 1703 rebellion and the structure of Ottoman politics (Istanbul, 1984).

*The formation of the modern state (Albany, 1991).

Barnes, John Robert. An introduction to religious foundations in the Ottoman Empire (Leiden, 1986).

Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom. The art and architecture of Islam, 1250–1800 (New Haven, corrected edn, 1995).

Brummet, Palmira. Ottoman seapower and Levantine diplomacy in the age of discovery (Albany, 1994).

*Busbecq, O. G. de. The Turkish letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq: Imperial Ambassador at Constantinople (Oxford, 1968).

*Darling, Linda. “Another look at periodization in Ottoman history,” Turkish Studies Association Journal 26, 2 (Fall, 2002), 19–28.

Faroqhi, Suraiya. Towns and townsmen in Ottoman Anatolia: Trade, crafts and food production in an urban setting (Cambridge, 1984).

Men of modest substance. House owners and house property in seventeenth-century Ankara and Kayseri (Cambridge, 1987).

*“Crisis and change, 1590–1699,” in Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), 411–636.

Fleischer, Cornell. Bureaucrat and intellectual in the Ottoman Empire: The historian Mustafa Ali (Princeton, 1986).

*Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and early modern Europe (Cambridge, 2002).

Goodwin, Godfrey. A history of Ottoman architecture (London, 1971).

Hess, Andrew. The forgotten frontier: A history of the sixteenth century Ibero-African frontier (Chicago, 1978).

Hourani, Albert. A history of the Arab peoples (Cambridge, MA, 1991).

Howard, Douglas. “Ottoman historiography and the literature of ‘decline’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,” Journal of Asian History, 22, 1 (1988), 52–77.

*Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650 (London, 2002).

İnalcık, Halil. “The Ottoman state: economy and society, 1300–1600,” in Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), 9–409.

İnalcık, Halil and Rhoads Murphey, eds. The history of Mehmet the Conqueror (Chicago and Minneapolis, 1978).

*Kafadar, Cemal. Between two worlds: The construction of the Ottoman state (Berkeley, 1995).

Karamustafa, Ahmet. God’s unruly friends: dervish groups in the Islamic later middle period, 1200–1550 (Salt Lake City, 1994).

*Keddie, Nikki, ed. Women and gender in Middle Eastern history (New Haven, 1991).

Köprülü, M. Fuad. The origins of the Ottoman Empire, trans. and ed. by Gary Leiser (Albany, 1992).

Lindner, Rudi Paul. Nomads and Ottomans in medieval Anatolia (Bloomington, 1983).

*Lowry, Heath W. The nature of the early Ottoman state (Albany, 2003).

“Pushing the stone uphill: the impact of bubonic plague on Ottoman urban society in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Ottoman studies, 23 (2003), 93–132.

*Mansel, Philip. Constantinople: City of the world’s desire, 1453–1924 (New York, 1995).

*McNeill, William. Europe’s steppe frontier 1500–1800 (Chicago and London, 1964).

*Mihailovic, Konstantin. Memoirs of a Janissary (Ann Arbor, 1975).

*Necipo lu, Gülru. Architecture, ceremonial and power: The Topkapı palace in the fifteênth and sixteenth centuries (Cambridge, MA, 1991).

lu, Gülru. Architecture, ceremonial and power: The Topkapı palace in the fifteênth and sixteenth centuries (Cambridge, MA, 1991).

Panaite, Viorel. “Power relationships in the Ottoman Empire. The sultans and the tribute-paying princes of Wallachia and Moldavia from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century,” International Journal of Turkish Studies, 7, 1 & 2 (2001), 26–53.

“The status of the Kharâj-güzarlar. A case study: Wallachians, Moldavians and Transylvanians in the 15th to 17th centuries.” The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation, I, (Ankara, 2000), 227–238.

*Peirce, Leslie. The imperial harem. Women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire (Oxford, 1993).

Tietze, Andreas. Mustafa Ali’s counsel for sultans of 1581, 2 vols. (Vienna, 1979–1982).

*Tucker, Judith. Gender and Islamic history (Washington, DC, reprint of 1993 edition).

Wittek, Paul. The rise of the Ottoman Empire (London, 1938).

*Zilfi, Madeline. Women in the Ottoman Empire. Middle Eastern women in the early modern era (Leiden, 1997).