General Fleet Action

The action between the battle fleets commenced immediately the signal for deployment had been hauled down, but firing was not general, mainly owing to the mist and smoke and partly owing to the masking of the enemy by our own ships. The reports from Flag and Commanding Officers, in several cases, make mention of the difficulty in obtaining a clear range, and a close study of these reports shows a considerable amount of masking occurred. This would appear to have been unavoidable, considering that all our detached and outlying squadrons were at this time converging on the battle fleet; and that the battle-cruisers were passing between our fleet and the enemy as they strained to get to the head of the line.

The Sixth Division – the rear division of the battle line – was the first to come into action. As the battleship Hercules started to turn into line of battle she was straddled, that is to say, shots of a salvo from the enemy fell, some short of, and some over, her; but she was not hit. Splashes from salvoes like these reached as high as the foretop. The enemy’s shells were also falling close to the battleships Vanguard and Revenge.

At this time the German light cruiser Wiesbaden, which had been severely damaged when in action with the battle-cruiser Invincible, was lying, apparently stopped, and on fire, in a favourable position as a target for any of our battleships which could not, at the moment, see any enemy capital ship to open fire on. She was engaged, and hit, by several of our ships, and, as the reports mention that shots which apparently came from the enemy ships were also falling close to the Wiesbaden, it is probable that this unfortunate ship was being fired on by her friends as well as her foes. She was also hit by a torpedo fired by the destroyer Onslow, and finally sank.

As our battle fleet started to deploy, the Defence and Warrior, which had been engaging enemy light cruisers, crossed so close ahead of the Lion that the battle-cruisers’ course had to be altered to clear them. These two armoured cruisers then found themselves within comparatively close range of the heavy ships of the enemy. They were immediately subjected to a very heavy concentrated fire, which in a minute or two was the cause of the Defence being blown up and sunk. The Warrior also received severe damage, but was able to withdraw from the battle. She would probably have suffered the same fate as the Defence but for the battleship Warspite, which, owing to her helm having jammed, described an involuntary circle between the Warrior and the enemy, thereby receiving many of the hits which were intended for the other ship. The Warrior was subsequently taken in tow by the seaplane carrier Engadine, but sank before reaching home, while the Warspite took no further part in the battle and was eventually ordered back to harbour.

The Marlborough, flying the flag of Admiral Burney, second-in-command of the Grand Fleet, leading the Sixth Division of Battleships, opened fire at 6.17 p.m., followed after a few minutes by the Revenge, and as the range cleared the ships ahead were able to come into action. The enemy battle fleet was at this time steering to the north-eastward.

BATTLE FLEETS IN ACTION

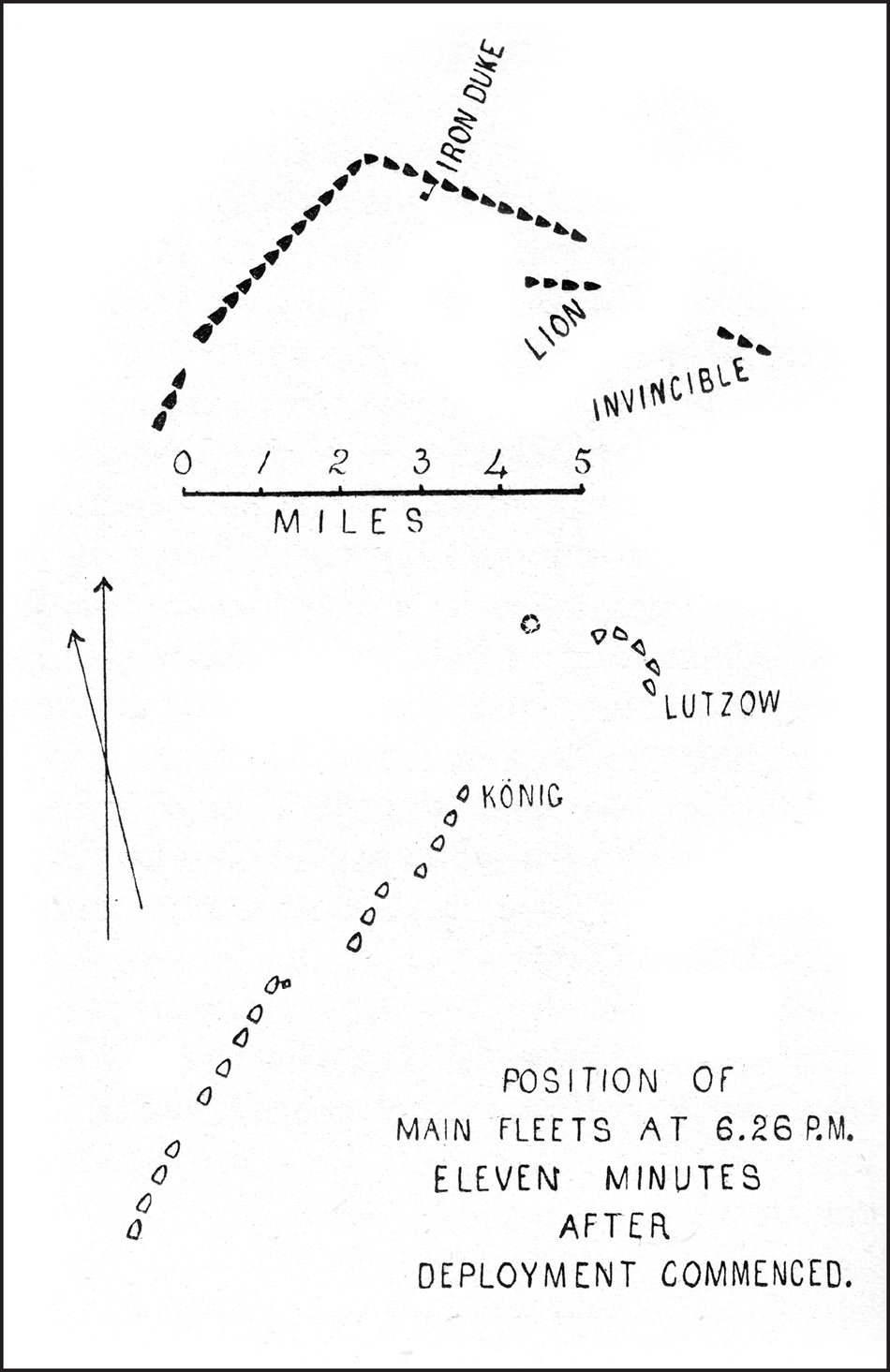

The situation at 6.26 p.m., a few minutes after the deployment commenced, is seen in Diagram No.7. This shows our battle fleet, in one line, leading round to the south-eastward. Our battle-cruisers are trying to get to the head of the line and the Third Battle-Cruiser Squadron is in action with the enemy battle-cruisers. It became necessary to reduce the speed of the battle fleet in order to allow the battle-cruisers to get clear, and thus give a better chance to the battleships to obtain a clear range.

As the battle-cruisers drew ahead the general situation became somewhat plainer to Jellicoe, although it was yet far from clear. He realized, however, that the moment had come when he could probably inflict severe damage on the enemy, and, at 6.29 p.m., he signalled for the course to be altered, by sub-divisions, to S.S.E., to bear down on the enemy. But this signal had to be cancelled for two reasons.

Firstly, there was some bunching up of our ships in the rear divisions, caused by the enforced reduction of speed to allow the battle-cruisers to draw ahead, and consequently the rearmost ships had not yet turned to the new course. Secondly, because the battle-cruisers were rapidly converging on the head of our line, which would have prevented the King George V, the leading battleship, from closing the enemy. This passage across the front of the battle fleet, to which Beatty was unavoidably committed, marred to some extent a very promising opening of the general action, and prevented full advantage being taken by Jellicoe of his position. At the moment of deployment, when the rear divisions were nearest the enemy, they were being masked by the battle-cruisers, and later on, as the head of our line came into a suitable position to inflict damage, it was prevented from doing so.

By 6.30 p.m. all the divisions of the battle fleet, except the First Division, had come into action. The view from the First Division was still obscure.

DIAGRAM 7: MAY 31

At the head of the line the Invincible, leading the Third Battle-Cruiser Squadron, had just turned to take station ahead of the First Battle Cruiser Squadron, and was heavily engaged with the enemy, when, at 6.34 p.m., she was badly hit, blew up and sank.18

Owing to the concentrated fire of many of our battleships, assisted by that of the battle-cruisers, the enemy suffered appreciable damage at this time. The enemy battle-cruisers suffered most, in fact, the Lutzow was so badly damaged that von Hipper was compelled to shift his flag. His first attempt was to board the Seydlitz, but as this ship was also badly damaged he went to the Moltke. The major portion of the damage incurred by them was, undoubtedly, inflicted after our battle fleet came into action. The fact that little damage was done to these ships before this explains, to a certain extent, the severe losses incurred in the sinking of the Indefatigable and the Queen Mary, and the considerable damage done to the Lion, which nearly resulted in her loss. The shooting of the enemy during this early stage was good, but it fell off later, and it was an established fact that the German gunnery efficiency showed a rapid decline as soon as our ships established hitting.

Several of the enemy battleships also suffered damage at this time. The Konig, at the head of the line, probably received greater damage from gunfire than any other enemy battleship.

THE FIRST GERMAN RETREAT

Scheer, to whom the situation was still obscure, now found himself becoming enveloped by our fleet. The British battle-cruisers, having reached the head of the line, were fine on his starboard bow and a great line of ships stretched across his track.

Owing to Jellicoe’s well-directed deployment, his “T” was practically crossed and his position was a desperate one. To escape from this predicament he made the famous “Battle turn away”, of the Germans, with his whole fleet. This manoeuvre was designed to enable his weaker fleet to get out of a tight corner. To gain time, and to enable the “turn away” to be made without considerable risk, a smoke-screen was put up by the enemy destroyers and, it is stated, a torpedo attack was also launched against our battle line. It seems more probable that the enemy destroyer flotilla was making an endeavour to reach the damaged Wiesbaden to rescue her crew, but on encountering the heavy fire directed on them by our battleships they were forced to retire. Six torpedoes were discharged at the rear of our battle line, but none hit, nor did this attack cause Jellicoe to deflect from his course.

Although the smoke-screen had prevented Jellicoe from seeing the enemy’s movements, it very soon became apparent to him that they must have turned away. There is no direct answer to the “Battle turn away” except a stern chase on the part of the stronger fleet, and a stern chase under such conditions would have been accompanied by risks which no prudent admiral could accept.

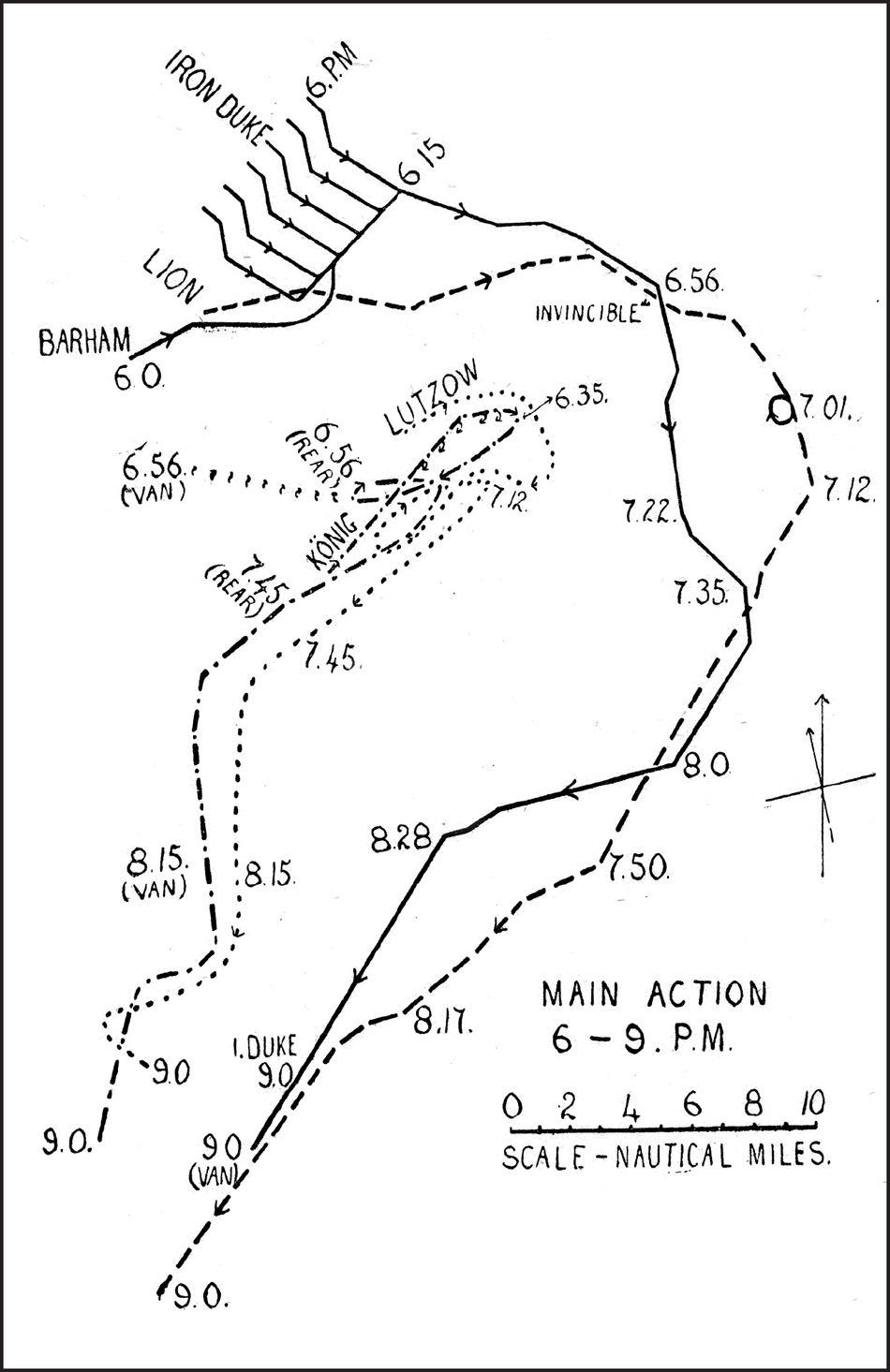

DIAGRAM 8: MAY 31

As we saw in Chapter II, a turn to follow the enemy directly would have placed our battle fleet in a position of great tactical disadvantage. It would have laid our ships open to attacks by torpedo from the German battleships, and also their destroyers, both of which would have been in the best possible position for this purpose. The menace of floating mines, dropped from the German battleships, would also have had to be accepted, as also would the possible danger from submarines. Our battle fleet had very slight superiority in speed over the enemy. A chase, therefore, would have been a long chase, with little hope of overtaking the enemy before dark, and some probability of losing the advantage, already gained, of being between the enemy and his base.

In clear weather the difficulty might have been met by dividing our fleet and despatching fast squadrons to harass his flanks; but, even so, the day was somewhat too far advanced to render this desirable. In the misty weather prevailing, and with so few hours of daylight remaining, such tactics had little to commend them owing to the difficulty of co-ordination between squadrons separated from one another.

BEATTY FAILS TO REGAIN TOUCH

Since there was nothing to indicate to Jellicoe, within a wide arc, the direction in which the enemy had retired, he took the only action possible which, at this time, might lead to ultimate victory. At 6.44 he turned the battle fleet to south-east, this being the best course to ensure getting fair between the enemy and his base, and at the same time to close the enemy obliquely for the purpose of renewing the action. Our battle-cruisers, whose main duty now was reconnaissance, also altered course to south-east and later to S.S.E. These alterations did not again bring the German ships into view, but Beatty did not turn farther in their direction.

In his despatch he states: “Caution forbade me to close the range too much with my inferior force.” This statement does not refer definitely to any particular time, so may be assumed to be his general policy. Beatty’s “reconnaissance force” was now six battle-cruisers against the enemy’s four; in this respect, therefore, Beatty had superior force. He also had ample superiority in speed to regain touch with the enemy and to ensure a safe retreat on our battle fleet without undue risk to his command.

Owing to the turn away of the enemy battle fleet, fire between the opposing capital ships ceased for a while. Ten minutes after altering course to the South-east the course of our battle fleet was again altered to starboard, to South, to close the supposed position of the enemy more directly.

At 6.54 p.m. the Marlborough was struck by a torpedo, which was probably fired by the damaged Weisbaden. She was able, however, to keep her place in the line for several hours, although her maximum speed was considerably reduced. At about this time our battle fleet passed the wreck of the Invincible, the Third and Fourth Divisions passing her one on either hand, the wreck being clearly visible with the bow and stern standing up out of the water, showing that the ship had been broken in two by the explosion, the midship parts resting on the bottom.19

SCHEER BLUNDERS INTO OUR BATTLE FLEET

Scheer, having extricated himself from his perilous position by his precipitate retreat and by standing to the westward for some minutes, turned again to the eastward. For all his protestations, it is unbelievable that he did this for the purpose of renewing the action. What is probable is that he had been misled, owing to the mist and smoke, as to the actual position of our battle fleet at about 6.35 p.m., and thought they were farther to the southward than was the case.

It seems probable, too, that he was of opinion that if he now turned back to the eastward he might succeed in crossing astern of our fleet, thereby not only getting into a more favourable position as regards his own base, but, in the event of a renewal of the action, getting the advantage of light towards sunset. No other explanation of Scheer’s tactics, at this time, appears reasonable. A capable leader and skilled tactician, as Scheer undoubtedly was, would not purposely have headed his fleet directly towards the centre of the arc formed by our battle fleet, thus bringing his leading squadrons under the concentrated fire of practically all our battleships, which is what happened.

At 6.54 p.m. Jellicoe, having had no report of the position of the enemy from his van ships, realized that the enemy battle fleet could not yet be heading for home, so he turned his fleet to south.

Commodore Goodenough, in the Southampton, who had previously sent so many reports of the position of the enemy battle fleet, made yet another effort to locate it. At about 7 p.m. he turned his squadron to the southward from his position near the rear of our battle line, and again located and reported the enemy, coming under heavy fire as he did so.

No firing was now taking place between the main fleets, the enemy being out of sight of all our battleships, and also of our battle-cruisers, which were at this time some 6 miles on the port bow of the Iron Duke, and farther from the enemy than the Fleet Flagship. Beatty had gone on at high speed and lost touch with what was happening.

Owing to the decreasing visibility, he would not have seen the battle fleet hauling round towards the enemy, but all signals for alteration of course, made from the Iron Duke, were sent out by wireless, so would have reached the battle-cruisers. He now reduced speed to 18 knots and began to circle to starboard to close the battle fleet. A complete circle was made by the Lion, the Princess Royal, Tiger and New Zealand following her round. Immediately after the completion of this turn the battle-cruisers Inflexible and Indomitable, which had been keeping ahead of the Lion, took station in line astern.20

THE SECOND GERMAN RETREAT

At 7.10 p.m. the head of the enemy fleet again came into sight from some of our battleships, and fire was immediately opened on the head of his battleship line by the Marlborough and her division, and on the enemy battle-cruisers by the Fifth Division. At this time the range was as low as 9,000 yards in some cases.

In a very short time practically the whole of our battle fleet was engaged, at ranges varying from 11,000 to 14,000 yards; but owing to the poor visibility organized concentration of fire was impossible. The enemy, especially his battle-cruisers, again received severe damage from our battleships. Some of our battle-cruisers also came into action again for a few minutes, but at a somewhat greater range.

Jellicoe had again secured a position of immense tactical advantage, having fairly crossed the enemy’s “T”, and only the poor visibility saved the German fleet from suffering an overwhelming defeat there and then.

As soon as the action was resumed Scheer realized that his position was an impossible one, and that his passage to the eastward was barred. Only one chance was his, and he took it. His flotillas were ordered to attack and put up smoke-screens. His battle-cruisers were ordered to, “Charge the enemy. Ram. Without regard to consequences”, and his battle fleet was again ordered to make the “Battle turn away”. The manoeuvre was successfully accomplished and the whole enemy fleet once more retired from the scene of action. This move on the part of the enemy was, again, not clear to Jellicoe, owing to the smoke screen.

ENEMY TORPEDOES ELUDED

At 7.22 p.m. the Eleventh Half-Flotilla of German Destroyers was observed to fire torpedoes and three minutes later the Seventeenth Half-Flotilla – twenty-one enemy torpedoes were fired in all. Immediately after launching this attack the enemy destroyers turned away and disappeared in a smokescreen. Ten minutes later a further attack was made by the Third and Fifth Flotillas of the enemy. This attack, however, was largely frustrated by a counter-attack on the part of our Fourth Light Cruiser Squadron.

When the torpedoes were fired, Jellicoe, at 7.22 p.m., in accordance with established custom, turned the battle fleet away 2 points, by sub-divisions; and after an interval of three minutes, when calculations showed that this turn would not be sufficient to avoid the torpedoes, he ordered a further turn of 2 points. The result of this manoeuvre was that, although several torpedoes were seen by our battleships, not one hit.

In his despatch Jellicoe states: “The torpedo attacks launched by the enemy were countered in the manner previously intended and practised during exercises.”

The torpedo attack, as an attack, failed; but the smoke-screen developed by the enemy destroyers was so far effective that it prevented Jellicoe from knowing the extent of the turn away of the enemy battle fleet.

Having avoided the torpedoes, he therefore turned our battle fleet to S. by W., 5 points towards the enemy. Without knowing the position of the enemy it would have been unwise to turn more than this, as he might have lost his position between the enemy and his base.

At 7.45 p.m. our battle fleet was again turned, to south-west towards the enemy, and at 8 p.m. to west. During this time, while course was being gradually altered to the westward, the enemy battle fleet was out of sight of our battle fleet. The signals received by Jellicoe during this time are not easy to understand.

THE “FOLLOW ME” INCIDENT

At 7.40 p.m. our battle-cruisers, having drawn ahead, had again lost touch with our battle fleet. The Lion was actually only 5¼ miles distant from the leading battleship, but, owing to poor visibility, was not in sight of her. Beatty, however, at this time remarks that the visibility had improved to the westward, and he signalled by wireless to Jellicoe to say: “Enemy bears from me N.W. by W. distant 10 to 11 miles.” The visibility must, therefore, have been very variable.

Again, at 7.45 p.m. Beatty signalled: “Leading enemy battleship bears N.W. by W. Course about S.W.” This makes it appear that the visibility to the north-westward was sufficiently good to judge the approximate course of a ship at a distance of about 11 miles.

Owing, however, to the Lion not being in sight of our battle fleet, which was now only 6 miles to the northward, this visual signal had to be passed through an intermediate ship, the armoured cruiser Minotaur. No mention is found in the reports from the other battle-cruisers that the enemy was in sight at this time, and in the report from the Captain of the Lion we find, under 7.32 p.m.: “The enemy was still not sufficiently visible to open fire, and this continued until 8.21 p.m.”

At 7.50 p.m. Beatty made the following signal by wireless to the Commander-in-Chief: “Submit van of battleships follow battle-cruisers. We can then cut off whole of enemy’s battle fleet.”

Considerable prominence has been given to this signal in the Press; more especially was this the case immediately after the publication of the official despatches. It may, therefore, be equitable to refer to it in some detail.

As our battle fleet was not in sight from the Lion, it is not clear how Beatty could know in what direction it was then steering. This could have been quickly ascertained by a visual signal to one of the ships bridging the gap.

Such a signal was made by Beatty at 8.15 p.m., so why not at 7.50 p.m. also? Again, it is not clear what “cutting off” is referred to. There is no suggestion that part of the enemy could be cut off from the main force, but that the whole battle fleet could be cut off. Presumably, therefore, it refers to cutting the enemy off from his base. The position, course and speed of our battle fleet could not have been improved upon for this purpose. As a fact, at the time the signal originated the van of the battle fleet was steering the same course as the Lion; was practically following the battle-cruisers – if anything, the van was a little on the Lion’s starboard quarter – and it was also nearer the enemy than was the Lion. An alteration in the course, to follow the battle-cruisers, at the moment the signal was made would, therefore, have caused the van to converge less on the enemy’s course than it was actually doing.

The message sent was, therefore, quite unnecessary, and likely to mislead the Commander-in-Chief.

This cipher message, which was timed 7.50 p.m., was received in the Iron Duke at 7.54 p.m., and must have led Jellicoe, who would not have seen it until it had been deciphered some minutes later, to conclude that the battle-cruisers, which he could not see, were steering a very different course to that of the battle fleet. Jellicoe at once signalled to the King George V, the van ship, to follow the battle-cruisers, and this order was received by Admiral Jerram at 8.7 p.m.

Meanwhile, at 8 p.m., the battle fleet had altered course to west, 4 more points towards the enemy. The signal for this alteration was made by flags, and also by wireless, so it would be received without delay by all ships. The battle-cruisers did not, however, turn at once but, for the next quarter of an hour, continued on a south-west course. They then altered course to west, towards the enemy, conforming to the movement of the battle fleet. The receipt of the signal to follow the battle-cruisers must have puzzled Jerram, because they were not in sight from the King George V. They could not be on his starboard side, because our battle fleet was in that direction, and any alteration to port would have led the First Division of the battle fleet farther from the enemy. Jerram, therefore, did the best thing possible and continued on his course.

CONTACT REGAINED, BUT THE ENEMY RETREATS AT ONCE

At 8 p.m. Beatty ordered the First and Third Light Cruiser Squadrons to sweep to the westward and locate the head of the enemy’s line before dark. The Third Light Cruiser Squadron, after being in action with some enemy cruisers, located the enemy battle-cruisers and, at 8.46 p.m., reported their position. Before, however, this report was made, our battle-cruisers had, almost immediately after turning to west, sighted what appeared to be two battle-cruisers and some battleships, and at 8.23 p.m. fire was opened on them. At this time the enemy’s main battle fleet, led by the battleship Westfalen, was steering a southerly course, with their battle-cruisers on the port bow and the Second Squadron of pre-Dreadnought battleships on the starboard bow.

Immediately our battle-cruisers opened fire the enemy battle-cruisers turned away to the westward; but the Second Squadron of old battleships, which now came into action for the first time, held on their course. The action lasted only for a few minutes before this squadron also turned away.

At 8.28 p.m. the course of our battle fleet was altered to south-west. The enemy at this time was bearing about west from the Iron Duke, and it was necessary for our battle fleet to alter course to port to prevent the enemy from passing ahead, and thus attaining an improved strategical position. By 8.40 p.m. the enemy had completely disappeared from sight from our battle-cruisers and was not seen again by them.

It is of interest that, at 8.40 p.m., all our battle-cruisers and some of the ships of the First and Third Light Cruiser Squadrons report feeling a shock, as if struck by a mine or torpedo. The reports are so definite that it is undeniable that some severe explosion occurred at this time. No satisfactory explanation of the cause of a shock of such magnitude can be given. The only explosion reported as having been seen at this time was seen from the light cruiser Calliope. It is possible that this was the enemy battleship Markgraf being hit by a torpedo, but Markgraf was some 8 miles from our battle-cruisers. It is practically certain that no submarine was in the vicinity.

Jellicoe received information of the whereabouts of the enemy, at about 8.40 p.m., from the light cruiser Comus, and shortly after this from the Falmouth and also from the Southampton.

This information, confirmed by a message sent from the Lion at 8.40 p.m. and received in the Iron Duke at 8.59 p.m., made the situation plain enough for Jellicoe to decide on his movements during the night. It was now getting dark, as sunset was at 8.7 p.m. and there was no moonlight during the dark hours.

THE PROBLEM OF THE NIGHT

Although darkness was now approaching, the problem of Jutland was by no means completed. It was, in fact, only beginning. With no more than three hours of daylight remaining after the main fleets met, it would have required more than a genius to ensure a decisive victory, against an enemy who was persistently endeavouring to avoid action, in the conditions of visibility then prevailing.

The actions before dark on 31st May must be considered, therefore, to be in the nature of preliminary skirmishes, of necessity curtailed owing to the late hour in the day at which the fleets met.

The real problem which then faced Jellicoe was, how to make as certain as human brain could make it that the enemy main fleet would be brought to action as early as possible after daylight the following morning.

The proceedings, and incidents, during the night cannot, therefore, be dismissed as subsidiary to the main problem, but should be as carefully and fully studied as any of the actions during daylight on 31st May.