If this work presents a coherent world view, it is in large part because I was fortunate enough to hear Colonel John Boyd deliver a brilliant series of lectures, “A Discourse on Winning and Losing.” In a world of analysts, he is that rare breed—a synthesist. I had long hoped to write a book explaining the power of a “systems” approach to solving America’s problems, and Colonel Boyd gave me an orientation, a paradigm for integrating information from several fields.

Joseph J. Romm, The Once and Future Superpower:

How to Restore America’s Economic, Energy, and Environmental Security

Boyd began work on two new briefings after finishing the last version of “Patterns of Conflict” in December 1986. “A Discourse on Winning and Losing” was created with the addition of two new briefings, entitled “An Organic Design for Command and Control,” completed in May 1987, and “The Strategic Game of ? and ?,” completed in June of the same year. He developed the thoughts on the command and control system in concert with the strategic insights and vice versa. Boyd’s desire for connections and harmony were at work again. The version of “A Discourse” that has been most widely disseminated is dated August 1987. The final major part of “A Discourse” was “The Conceptual Spiral,” added in July and August 1992. Boyd presented the whole thing as one briefing, but it is really a collection of these different briefings.

One of the most fundamental of Boyd’s briefings, “The Strategic Game” was not developed until almost a decade after the first version of “Patterns of Conflict.” Both an explanation and demonstration of how one goes through the OODA loop process, it serves as the link between “Destruction and Creation” (1976) and “The Conceptual Spiral” (1992) in Boyd’s intellectual odyssey. It is the best example of how Boyd’s mind wrestled with abstract concepts and their concrete implications.

“The Strategic Game of ? and ?” begins by asking a series of questions: What lies under the question marks? What is strategy? What is the aim or purpose of strategy? What is the central theme and what are the key ideas that underlie strategy? How do we play this theme and activate these ideas?1 His approach was somewhat oblique, however, for he began in a rather unorthodox but very effective manner with what he called a thought experiment.

Imagine that you are on a ski slope skiing down a mountain. Retain that image. Now imagine that you are in sunny Florida riding in an outboard motor boat. Retain that image. How else might you move about on a nice spring day? On land, riding a bicycle would be nice. Retain that image too. Now imagine that you are a parent taking your son to a department store and you notice that the toy tractors with rubber caterpillar treads fascinate him. Retain this image too. What could you fashion from these disparate images? Selecting parts of these items and images, what can we create from them? Pull the skis off the ski slope, the outboard motor from the motorboat, the handlebars off the bicycle, and the rubber treads off the toy tractor. Discard the rest of the images. What do you have? A snowmobile!

Boyd presented his allusion to the components for building snowmobiles as an illustration of synthesis. “Snowmobile” was one of Boyd’s favorite shorthand terms. He classified people into two types, those who could build snowmobiles and those who couldn’t. The former would be winners in this complex, unknown world in which we had to exist. The latter would fail to adapt and would inevitably lose. Boyd then surveyed a variety of disciplines, repeating his views on how we set about to survive and prosper and what that requires. How do we do this? Boyd answers with an array of quotations from newspapers, books, and speeches. Only a few are reproduced here to reveal the eclectic nature of his mind at work and the snowmobiles he built routinely in his thought.2

Boyce Rensberger, “Nerve Cells Redo Wiring …,” Washington Post

Dale Purvis and Robert D. Hadley … have discovered that a neuron’s fibers can change significantly in a few days or weeks, presumably in response to changing demands on the nervous system.… research has shown neurons continuously rewire their own circuitry, sprouting new fibers that reach out to make contact with new groups of other neurons and withdrawing old fibers from previous contacts.… This rewiring process may account for how the brain improves one’s abilities such as becoming proficient in a sport or learning to play a musical instrument. Some scientists have suggested that the brain may use this method to store facts.… The research was on adult mice, but since all mammalian nervous systems appear to behave in similar ways, the researchers assume that the findings also apply to human beings.

Richard M. Restak, “The Soul of the Machine” (review of Neuronal Man, by Jean-Pierre Changeux), Washington Post Book World

Changeux suggests that the complexity of the human brain is dependent on the vast number of synapses (connection) between brain cells.… these synaptic connections are established or fall by the wayside according to how frequently they’re used. Those synapses which are in frequent use tend to endure (“are stabilized”) while others are eliminated.… In other words, … interactions with the environment [exert] tremendous influence on the way the human brain works and how it has evolved.

Ilya Prigogene and Isabelle Stenger, Order Out of Chaos3

Equilibrium thermodynamics provides a satisfactory explanation for a vast number of physicochemical phenomena. Yet it may be asked whether the concept of equilibrium structures encompasses the different structures we encounter in nature. Obviously the answer is no.

Equilibrium structures can be seen as the results of statistical compensation for the activity of microscopic elements (molecules, atoms). By definition they are inert at the global level.… Once they have been formed they may be isolated and maintained indefinitely without further interaction with their environment. When we examine a biological cell or a city, however, the situation is quite different: not only are these systems open, but also they exist only because they are open. They feed on the flux of matter and energy coming to them from the outside world. We can isolate a crystal, but cities and cells die when cut off from their environment. They form an integral part of the world from which they can draw sustenance, and they cannot be separated from the fluxes that they incessantly transform.

Alexander Atkinson, Social Order and the General Theory of Strategy4

Moral fibre is “the great dam that denies the flood of social relations their natural route of decline towards violence and anarchy.” … In this sense, “a moral order at the center of social life literally saves society from itself.”

Strategists must grasp this fact that social order is, at once, a moral order.… If the moral order on which rests a fabric of social and power relations is compromised, then the fabric (of social order) it upholds goes with it.

In other words, “the one great hurdle in the strategic combination (moral and social order) is the moral order. If this remains untouched the formation of new social relations and social ranking in status and power either never gets off the ground or faces the perennial spectre of backsliding towards the moral attraction of established social and power relations.”

The strategic imperative, then, becomes one of trying “to achieve relative security of social resources by subverting and reweaving those of the opponent into the fabric of one’s own order.”

Boyd, “Destruction and Creation”

According to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics one cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself. Moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder.

Dimitry Mikheyev, “A Model of Soviet Mentality” (a speech)

Interaction between the individual and his environment starts with his perception of himself as a separate entity and the environment as everything outside of self. He learns his physical limits and desires, and how to fulfill them through interaction with the physical and social environment.… I maintain that the way the individual perceives the environment is crucial for his orientation and interaction with it.

Man’s orientation will involve perceptions of self as both a physical and a psychological entity, as well as an understanding of the environment and of the possibilities for achieving his goals. (Fromm, 1947) Society, meanwhile, has goals of its own—preservation of its physical integrity and spiritual identity. Pursuing these goals involves mobilizing and organizing its inner resources and interaction with the outside environment of other societies and nations.… An individual becomes a member of the society when he learns to act within its limits in a way that is beneficial to it.

Boyd then added a few more items before asking what this mélange of insights and ingredients means.

Old Fable: But sir, the emperor is naked, he has no clothes.

Sun Tzu: Know your enemy and know yourself; in one hundred battles you will never be in peril.

Seize that which your adversary holds dear or values most highly; then he will conform to your desires.

Jomini: The great art, then, of properly directing lines of operations, is so to establish them in reference to the bases and to the marches of the army as to seize the communications of the enemy without imperiling one’s own, and is the most important and most difficult problem in strategy.

Leadership: The art of inspiring people to cooperate and to take action enthusiastically toward the achievement of uncommon goals.

So what are we to make of all of these seemingly random insights? How do they help us to understand strategy? To Boyd, it was quite clear and relatively simple.

Physical as well as electrical and chemical connections in the brain are shaped by interacting with the environment. Point: Without these interactions we do not have the mental wherewithal to deal or cope with that environment.

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics, all taken together, show that we cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself. Moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder—mental as well as physical. Point: We need an external environment, or outside world, to define ourselves and maintain organic integrity, otherwise we experience dissolution and disintegration—i.e., we come unglued.

Moral fiber or moral order is the glue that holds society together and makes social direction and interaction possible. Point: Without this glue social order pulls apart toward anarchy and chaos, leaving no possibility for social direction and interaction.

Living systems are open systems; closed systems are nonliving systems. Point: If we don’t communicate with the outside world—to gain information for knowledge and understanding as well as matter and energy for sustenance—we die out to become a nondiscerning and uninteresting part of that world.

Interaction permits vitality and growth; isolation leads to decay and disintegration. Thus, the theme that is associated with all the pieces of “A Discourse on Winning and Losing” to date is one of interaction and isolation. “An Organic Design for Command and Control” emphasizes interaction, “Patterns of Conflict” emphasizes isolation, and “Destruction and Creation” is balanced between interaction and isolation. Ultimately one is involved in a game in which one must be able to diminish an adversary’s ability to communicate or interact with his environment while sustaining or improving one’s own ability to do so.

Just how does one go about doing this? Boyd focused on three planes: moral, mental, and physical. The physical one represents the world of matter, energy, and information we are all a part of, the world we live in and feed on. The mental plane represents the emotional, intellectual activity generated to adjust to, or cope with, that physical world. The moral represents the cultural codes of conduct or standards of behavior that constrain, as well as sustain and focus, one’s emotional and intellectual responses.

Physical isolation occurs when one fails to gain support in the form of matter, energy, or information from others outside oneself. Mental isolation occurs when one fails to discern, perceive, or make sense out of what is happening. Moral isolation occurs when one fails to abide by codes of conduct or standards of behavior in a manner deemed acceptable or essential by others. Looked at from the opposite perspective, physical interaction occurs when one freely exchanges matter, energy, or information with others. Mental interaction occurs when one generates images or impressions that match the events or happenings that unfold. Moral interaction occurs when one lives by the codes of conduct or standards of behavior that one professes and others expect us to uphold.

So what? How does one link these seemingly unrelated insights? Linking Gödel, Heisenberg, and the second law of thermodynamics, Boyd reminded us that “one cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself; moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder.” Jumping radically, he asked, “What do the tests of the YF-16 and YF-17 say? … The ability to shift or transition from one maneuver to another more rapidly than an adversary enables one to win in air-to-air combat.” The implication of the overall message, as Boyd called it, is this:

The ability to operate at a faster tempo or rhythm than an adversary enables one to fold the adversary back inside himself so that he can neither appreciate nor keep up with what is going on. He will become disoriented and confused; which suggests that

Unless such menacing pressure is relieved, the adversary will experience various combinations of uncertainty, doubt, confusion, self-deception, indecision, fear, panic, discouragement, despair, etc., which will further

Disorient or twist his mental images and impressions of what is happening; thereby

Disrupt his mental and physical maneuvers for dealing with such a menace; thereby

Overload his mental and physical capacity to adapt or endure; thereby

Collapse his ability to carry on.

By combining insights and experiences, by looking at other disciplines and activities and connecting them, one can create new strategies for coping with the world and one’s adversaries. Doing so allows one to develop repertoires of competition, ways to contend with multiple adversaries in different contexts. In doing so, one develops a fingerspitzengefühl (“finger-tip feel”) for folding adversaries back inside themselves, morally, mentally, and physically, so that they can neither appreciate nor cope with what is happening. Thus, the artful manipulation of isolation and interaction is the key to successful strategy.

Boyd paid particular attention to the moral dimension and the effort to attack an adversary morally by showing the disjuncture between professed beliefs and deeds. The name of the game for a moral design for grand strategy is to use moral leverage to amplify one’s spirit and strength while exposing the flaws of competing adversary systems. In the process, one should influence the uncommitted, potential adversaries and current adversaries so that they are drawn toward one’s philosophy and are empathetic toward one’s success.

Boyd then set out to answer the questions he asked at the beginning. He defined strategy as “a mental tapestry of changing intentions for harmonizing and focusing our efforts as a basis for realizing some aim or purpose in an unfolding and often unforeseen world of many bewildering events and many contending interests.” Its aim was “to improve our ability to shape and adapt to unfolding circumstances, so that we (as individuals or as groups or as a culture or as a nation-state) can survive on our own terms.” Interaction and isolation were the key themes. Analysis and synthesis activate these across a variety of domains and spontaneously generate new mental images that match up with an unfolding world of uncertainty and change. Then, seemingly as an afterthought, the last slide presents two definitions: “Evil occurs when individuals or groups embrace codes of conduct or standards of behavior for their own personal well-being and social approval, yet violate those very same codes or standards to undermine the personal well-being and social approval of others” and “Corruption occurs when individuals or groups, for their own benefit, violate codes of conduct or standards of behavior that they profess, or are expected, to uphold.” The briefing ends abruptly on this note.

It should be noted that this was written just after his protégé Col. Jim Burton had fought his battles with the Department of Defense over the testing and evaluation of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, when the momentum of the military reform movement started to flag. It is symptomatic of Boyd’s assessment of those with whom he was contending. Boyd, like Spinney, came to believe that many in the government were evil and corrupt, and Boyd and his closest associates were mired in that corruption.

This combination was new: alternating cycles of interaction and isolation as the essence of strategy with the concept of moral leverage as an essential part of military strategy and the nature of war as a moral and mental as well as physical struggle. Others had spoken of the moral and mental aspects of war, even hinted at the moral leverage necessary to win, but few had spoken of the strategic process as alternating cycles of isolation and interaction. None had combined all three. For Boyd, they were implicit in his notions of strategy and war. One went to war for moral purpose. Using moral leverage was of tremendous advantage, and the pattern of isolation and interaction was critical to success. This was just as true of personal contests or bureaucratic struggles in the Pentagon over defense policy issues as it was on the battlefield against conventionally arrayed forces or guerrillas in the jungles of Vietnam. Understanding the essence of conflict across the human spectrum gave one a better understanding of how to survive and prosper.

The world is full of what Kevin Kelly has called “the rise of the neobiological civilization.” That’s the subtitle of his book Out of Control. His main point is a simple one of immense ramifications: “The realm of the born—all that is nature—and the realm of the made—all that is humanly constructed—are becoming one. Machines are becoming biological and the biological is becoming engineered.”5 They are not quite fused, but they become closer all the time. Both are becoming distorted in the process, as is the role of humans in an increasingly technologically complex and interdependent world. That world is moving at faster tempos of cost and consequence, some of which are known but most of which remain mysterious until after the fact. Is the Internet alive or engineered? Could we have predicted its consequences?

Boyd was particularly concerned with command and control issues, which he called C&C in his briefings and the military refers to generally as C2. Command and control issues are concerned with communication and the implementation of tactics and strategy so that military operations can be carried out as they are supposed to unfold. The problem, of course, is that they rarely do. Denied perfect foreknowledge, one always has to make adjustments. Hence, the flow of information from commander to subordinate units and back is critical to the success of any military engagement. C2 for most military officers suggests hardware and wiring diagrams, the array of communications systems, the radio frequencies to be used, and so forth. Boyd used organic metaphors to emphasize an organic, biological approach to understanding what we are about as counterpoint to the tremendous reliance on technology that we have developed.

Among the basic C&C imperatives for Boyd are the need to understand how well people trust each other, the need to understand the commander’s intent, and the purpose for which one needs authority, responsibility, and communication in the first place. He approached the problem not as one of electronic communication from superior to subordinate but of observation relayed from subordinate to superior. This created an outside-in, bottom-up approach dependent first on gathering information about the environment before beginning the OODA loop. First and foremost, one needs to apprehend and comprehend the strategic environment. The critical information flows are thus not down the chain of command but up, for it is only by processing this information that we can adapt successfully as events unfold.

Boyd began his “Organic Design for Command and Control” by asking, “Why the focus on C&C? What do we mean by an organic design?” He then enumerated some failed C2 exercises and the debacles of the evacuation of Saigon and the Desert One incident.

The institutional response for overcoming these fiascoes is: more and better sensors, more communications, more and better computers, more and better display devices, more satellites, more and better fusion centers, etc.—all tied into one giant fully informed, fully capable C&C system. This way of thinking emphasizes hardware as the solution.… I think there is a different way—a way that emphasizes the implicit nature of human beings. In this sense, the following discussion will uncover what we mean by both implicit nature and organic design.6

What is important for Boyd here is the insight and vision to unveil adversary plans and actions as well as to foresee our own goals and appropriate plans and actions. Without insight and vision there can be no orientation to deal with both present and future. Second, one needs focus and direction to achieve some goal or aim. Without focus and direction, implied or explicit, there can be neither harmony of effort nor initiative for vigorous effort. Third, one must be adaptable to cope with uncertain and ever-changing circumstances. Adaptability implies variety and rapidity. Without variety and rapidity one can neither be unpredictable nor cope with the changing and unforeseen circumstances. Last, we need security, to remain unpredictable. Without security one becomes predictable, hence one loses the benefits of the other elements.

Boyd then reviewed some military history beginning with Sun Tzu and progressing through Bourcet, Napoleon, Clausewitz, Jomini, Forrest, Blumentritt, and Balck, ending with his own take on war. The key points he took from this review are that war involved friction, as Clausewitz showed. Friction is amplified by such factors as menace, ambiguity, deception, rapidity, uncertainty, and mistrust, among others. Implicit understanding, trust, cooperation, and simplicity can diminish friction. For Boyd, the key point was that variety and rapidity tend to magnify friction, while harmony and initiative tend to diminish friction. More particularly, variety and rapidity without harmony and initiative lead to confusion, disorder, and finally chaos. On the other hand, harmony and initiative without variety and rapidity lead to rigid uniformity, predictability, and finally nonadaptability. What fosters harmony and initiative and destroys variety and rapidity? Activities that promote correlation, commonality, and accurate information flows are beneficial. Compartmentalization, disconnected data flows, and plans laid out as recipes to be followed are not. For Boyd, the interactions represented a many-sided implicit cross-referenced process of projection, empathy, correlation, and rejection. In short, one’s orientation to the world is one’s understanding of reality.

Orientation is a complex amalgam of images, views, or impressions of the world shaped by an interactive process. This process consists of these interactions and shapes and is shaped by the interplay of genetic heritage, cultural traditions, previous experiences, and unfolding circumstances. Orientation, the big O in the OODA loop, is the schwerpunkt. It shapes the way we observe, decide, and act. To be successful one needs to create mental images, views, or impressions (patterns) that match with the activity of the world. Moreover, one needs to deny the adversary the possibility of uncovering or discerning patterns that match one’s activity. The essential idea, as Boyd called it, is that patterns (hence, orientation), right or wrong, suggest ability or inability to conduct many-sided implicit cross-references. “How do we set up and take advantage of the many-sided implicit cross-referencing process of projection, empathy, correlation, rejection that makes appropriate orientation possible?” The message for Boyd is to “expose individuals, with different skills and abilities, against a variety of situations—whereby each individual can observe and orient himself simultaneously to the others and to the variety of changing situations.”

In such an environment, the bonds of implicit communication and trust that evolve as a consequence of the similar mental images create a harmony, focus, and direction in operations. A strong set of shared impressions is created by each individual. This is committed to memory by repeatedly sharing the same variety of experience in the same ways. What has all this to do with C&C? The secret of a superior command and control system lies in what is unstated or not communicated explicitly to one another. One thereby diminishes friction and compresses time, gaining both quickness and security. Similarly, an inability to operationalize shared impressions may increase friction, reduce adaptability, and make one unable to cope with events. The Marine Corps is working on an extension of this concept called intuitive decision making.

According to Boyd’s trinity of Gödel, Heisenberg, and the second law of thermodynamics, “One cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself. Moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder.” Applying these ideas, one can see that “He who can generate many noncooperative centers of gravity magnifies friction. Why? Many noncooperative centers of gravity within a system restrict interaction and adaptability of [the] system with its surroundings, thereby leading to a focus inward (i.e., within itself), which in turn generates confusion and disorder, which impedes vigorous or directed activity, hence, by definition, magnifies friction or entropy.” Any command and control system that forces adherents to look inward leads to dissolution and disintegration. In other words, as Boyd said, “they become unglued.” There is both a positive and a negative aspect to this. If you have these implicit bonds and understandings, you have harmony and initiative within the group. Without them, they are impossible. There is no way that such an organic whole can stay together and cope with a many-sided, uncertain, and ever-changing environment. Without this internal consistency, friction becomes magnified, paralysis sets in, and the system collapses.

One must emphasize the implicit over the explicit to gain a favorable mismatch in friction and time. To do this, one must suppress the tendency to build up explicit internal arrangements that hinder interaction with the external world. Instead, one must arrange a setting among leaders and subordinates alike that gives them the opportunity to interact continuously with the external world and with each other. Doing so allows them to make many-sided implicit cross-referencing projections, empathies, correlations, and rejections more quickly. Simultaneously, they create the similar images or impressions, hence a similar implicit orientation, needed to form an organic whole.

For those that are so organized, the payoff comes as they diminish their friction and reduce time, thereby permitting them

to exploit variety/rapidity while maintaining harmony/initiative, thereby

to get inside the adversary’s OODA loops, thereby

to magnify the adversary’s friction and stretch out his time (for a favorable mismatch in friction and time), thereby

to deny the adversary the opportunity to cope with events/efforts as they unfold.

Done correctly, it is a relatively easy and low-cost way to achieve a sizable advantage over a foe, and it does not necessarily involve the use of weaponry. What is at stake is one’s orientation to the world and the actions of those in it. Since a first-rate command and control system should possess the above qualities, any design or related operational methods should increase implicit orientation. This really means that the OODA loop can be thought of as the C&C loop. Once again, it is the second O, orientation (the repository of genetic heritage, cultural traditions, and previous experiences) that is the most important part of the OODA loop, since it shapes the way one observes, decides, and acts. Therefore, operating inside an adversary’s OODA loop is the same as operating inside the adversary’s C&C loop.

Boyd turned next to some “historical snapshots,” referring to Napoleon’s use of staff officers for personal reconnaissance, Moltke’s message directives of few words, British tight control at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the British GHQ phantom recce regiment in World War II, Patton’s household cavalry, and Israeli views on getting accurate assessments of battle. These examples reinforce the notion that command and control must permit one to direct and shape what is to be done as well as permit one to modify that direction and shape by assessing what is being done. “Command must give direction in terms of what is to be done in a clear, unambiguous way. In this sense, command must interact with system to shape the character or nature of that system in order to realize what is to be done. Control,” on the other hand, “must provide assessment of what is being done, also in a clear, unambiguous way. In this sense, control must not interact or interfere with system but must ascertain (not shape) the character/nature of what is being done.”

Boyd cut to the heart of the matter:

Reflection upon the statements associated with the Epitome of Command and Control leave us unsettled as to the accuracy of these statements. Why? Command, by definition, means to direct, order, or compel, while control means to regulate, restrain, or hold to a certain standard as well as to direct or command. Against these standards it seems that the command and control (C&C) we are speaking of is different than the kind that is being applied. In this sense, the C&C we are speaking of seems more closely aligned to leadership (rather than command) and to some kind of monitoring ability (rather than control) that permits leadership to be effective. In other words, leadership with monitoring, rather than C&C, seems to be a better way to cope with the multifaceted aspects of uncertainty, change, and stress. On the other hand, monitoring, per se, does not appear to be an adequate substitute for control. Instead, after some sorting and reflection, the idea of appreciation seems better. Why? First of all, appreciation includes the recognition of the worth or value and the idea of clear perception as well as the ability to monitor. Moreover, next, it is difficult to believe that leadership can even exist without appreciation.

As Boyd saw it, appreciation and leadership permit one to discern, direct, and shape what is to be done, and they permit one to modify that direction and shape by assessing what is being done or about to be done.

Appreciation, as a part of leadership, must provide assessment of what is being done in a clear and unambiguous way. In this sense, appreciation must not interact or interfere with system but must discern (not shape) the character/nature of what is being done or about to be done; whereas leadership must give direction in terms of what is to be done also in a clear, unambiguous way. In this sense, leadership must interact with system to shape the character or nature of that system in order to realize what is to be done. Assessment and discernment should be invisible and should not interfere with operations, while direction and shaping should be evident to system—otherwise appreciation and leadership do not exist as an effective means to improve our fitness to shape and cope with unfolding circumstances.

To Boyd, C&C represented a top-down and inside-out mentality applied in a rigid, mechanical (or electrical) way that ignores as well as stifles the implicit nature of human beings to deal with uncertainty, change, and stress. He decided, therefore, that the briefing he had just given had been mistitled. “Pulling these threads together suggests that appreciation and leadership offer a more appropriate and richer means than C&C for shaping and adapting to circumstances” (emphasis is Boyd’s). It should correctly be called “appreciation and leadership.”

He left us with a set of definitions to ponder.

Understanding means to comprehend or apprehend the import or meaning of something.

Command refers to the ability to direct, order, compel, with or without authority or power.

Control means to have power or authority to regulate, restrain, verify (usually against some standard), direct, or command. Comes from medieval Latin contrarotulus, a counter roll or checklist (contra, against, plus rotulus, to list).

Monitoring refers to the process that permits one to oversee, listen, observe, or keep track of as well as to advise, warn, or admonish.

Appreciation refers to the recognition of worth or value, clear perception, understanding, comprehension, discernment.

Leadership implies the art of inspiring people to cooperate and enthusiastically take action toward the achievement of uncommon goals.

Trust, appreciation, and leadership are keys to success for any family, church, school, business, political system, or military. They are the real family values, the basic core values, and cultural bedrock that undergird truly successful societies and organizations. The urge to command and control is part of the problem, not part of the solution. It is an impediment to creative adaptation, to true insight, imagination, and innovation. Creating a system that seems to respond intuitively to the challenges and opportunities it encounters is a far more effective way to proceed. Such a system emphasizes the organic, natural aspects of human relationships and interactions rather than the technology, which both connects and separates us from each other.

The result of seven years of additional reading and distillation, “The Conceptual Spiral” sought “to make evident how science, engineering, and technology influence our ability to interact and cope with an unfolding reality that we are a part of, live in, and feed upon.”7 The basic question was: How do we go about adapting successfully in the modern world? Boyd’s answer was contained in 30 slides of carefully crafted analysis and synthesis. He began every “Conceptual Spiral” briefing by asking the audience how many had heard of half a dozen important scientists, mathematicians, and inventors or their discoveries. He then asked why they were significant. Though the results varied from audience to audience, they were invariably disappointing. Few were aware of some of the more important contributions to modern science. What follows is a prose version of his thoughts in that briefing and commentary on it. It is written as a discussion similar to one Boyd would have held with his audience. The ideas and most of the words are his. They have been rearranged for clarity.

For openers, Boyd suggested a reexamination of the larger briefing, “A Discourse on Winning and Losing.” The theme that weaves its way through “A Discourse” is thinking that consists of pulling ideas apart (analyses) while intuitively looking for connections that form a more general elaboration (synthesis) of what is taking place. The process not only creates the discourse but also represents the key to evolve the tactics, strategies, goals, and unifying themes that permit us to shape and adapt to the world around us.

By examining the practice of science and engineering and the pursuit of technology, one can evolve a conceptual spiral for comprehending, shaping, and adapting to that world. Boyd defined science as a self-correcting process of observation, hypothesis, and test—the essence of the scientific method. Engineering can be viewed as a self-correcting process of observation, design, and test. Technology can be viewed as the wherewithal or state of the art produced by the practice of science and engineering. This in turn raises the question, What has the practice of science and engineering and the pursuit of technology done for us? Boyd then proceeded to list what he considered some of the key advances in scientific knowledge (table 7). His selections were conceptual breakthroughs, leaps in the process of invention and discovery, the macrodiscoveries that enabled others to follow with important inventions that would have been impossible without these mental breakthroughs. The list suggests wide reading and intimate understanding of a wide array of scientific accomplishments.

Boyd’s briefings were essentially a dialogue with the audience. A natural teacher, he understood that if he told you something, he robbed you of the opportunity to ever truly know it for yourself. He was skilled at asking a series of leading questions to guide the group’s thinking about relationships so that they would figure the lesson out just before he had to tell them. In so doing, he demonstrated the kind of thinking that he sought to demand from others, a set of implicit and explicit many-sided cross-references to expand people’s horizons. He then urged them to continue the process, make their own connections, and continue the spiral of conceptual insights.

Table 7. Examples from Science

| Outstanding Contributors | Outstanding Contributions |

| Isaac Newton (1687) | Exactness-predictability via laws of motion-gravitation |

| Adam Smith (1776) | Foundation for modern capitalism |

| A. M. Ampere, C. F. Gauss | Exactness-predictability via electronic-magnetic laws |

| (1820s, 1830s) | |

| Carnot, Kelvin, Clausius, Boltzman | Decay-disintegration via second law of thermodynamics |

| (1824, 1852, 1865, 1870s) | |

| Faraday, Maxwell, Hertz | Union of electricity and magnetism via field theory |

| (1831, 1865, 1888) | |

| Darwin, Wallace (1838, 1858) | Evolution via theory of natural selection |

| Marx, Engels (1848–1895) | Basis for modern scientific socialism |

| Gregory Mendel (1866) | Inherited traits via laws of genetics |

| Henri Poincare (1890s) | Inexactness-unpredictability via gravitational influence of |

| three bodies | |

| Max Planck (1900) | Discreteness-discontinuity via his quantum theory |

| Albert Einstein (1905–1915) | Exactness-predictability via his special and general |

| relativity theories | |

| Bohr, de Broglie, Heisenberg, | Uncertainty-indeterminism in quantum physics |

| Shrodinger, Dirac et al. (1913, | |

| 1920s and beyond) | |

| L. Lowenheim, T. Skolem | Unconfinement (noncategoricalness) in mathematics and logic |

| (1915–1933) Gödel, Tarski, Church, Turing et al. | Incompleteness-undecidability in mathematics and logic |

| (1930s and beyond) | |

| Claude Shannon (1948) | Information theory as a basis for communication |

| Crick & Watson (1953) | DNA spiral helix as genetically coded information for life |

| Lorenz, Prigogene, Mandelbrot, | Irregular-unpredictability in nonlinear dynamics |

| Feigenbaum et al. (1963, | |

| 1970s and beyond) | |

| G. Chaitin, C. Bennett (1965, 1985) | Incompleteness-incomprehensibility in information theory |

Source: John R. Boyd, “The Conceptual Spiral,” unpublished briefing, August 1992, pp. 9-10.

Boyd then gave an even more detailed set of examples from engineering that scientific discoveries helped to make possible, mainly during the last 200 years (table 8). He focused on inventions familiar to the audience, easily identified as milestones with connections to technological advancement and social transformations. Boyd commented on his favorites and then pushed on to why they were important and their implications.

Looking at the past via the contributions these people had provided the world, what can one say about our efforts for now and in the future? In a mathematical-logical sense one can say that taken together, the theorems associated with Gödel, Lowenheim and Skolem, Tarski, Church, Turing, Chaitin, and others reveal a consistent theme and reinforce each other. Not only do the statements representing a theoretical system for explaining some aspect of reality explain that reality inadequately or incompletely, but they also spill out beyond any one system and do so in unpredictable ways. Conversely, these theorems reveal that one cannot predict the future migration and evolution of these statements or just confine them to any one system or suggest that they fully embrace any such system.

Table 8. Examples from Engineering

| Outstanding Contributors | Outstanding Contributions |

| Savery, Newcomen, Watt (1698, 1705, 1769) | Steam engine |

| George Stephenson (1825) | Steam railway |

| H. Pixil, M. H. von Jacobi (1823, 1838) | AC generator, AC motor |

| Samuel F. B. Morse (1837) | Telegraph |

| J. Nieqce, J. Daguerre, Fox Talbot (1839) | Photography |

| Gaston Plante (1859) | Rechargeable battery |

| Z. Gramme, H. Fontaine (1869, 1873) | DC generator, DC motor |

| Nicholas Otto (1876) | 4-cycle gasoline engine |

| Alexander G. Bell (1876) | Telephone |

| Thomas A. Edison (1877) | Phonograph |

| Thomas A. Edison (1879) | Electric lightbulb |

| Werner von Siemans (1879) | Electric locomotive |

| Germany (1881) | Electric metropolitan railway |

| Charles Parsons (1884) | Steam turbine |

| Benz, Daimler (1885, 1886) | Gasoline automobile |

| T. A. Edison, J. LeRoy, T. Armat et al. (1890-1896) | Motion picture camera, projector |

| Rudolf Diesel (1897) | Diesel locomotive |

| Italy (1902) | Electric railway |

| Wright Brothers (1903) | Airplane |

| Christian Hulmeyer (1904) | Radar |

| V. Paulsen, R. A. Fessenden (1904, 1906) | Wireless telephone |

| John A. Fleming, Lee De Forest (1904, 1907) | Vacuum tube |

| Tri Ergon, Lee De Forest (1919, 1923) | Sound motion picture |

| USA, Pittsburgh (1920) | Public radio broadcasting |

| American Car Locomotive (1925) | Diesel-electric locomotive |

| J. L. Baird (1926) | Television |

| Warner Brothers (1927) | Jazz Singer, sound motion picture |

| Germany, USA (1932, 1934) | Diesel-electric railway |

| Britain, USA, Germany (1935-1939) | Operational radar |

| Germany, Britain, USA (1935, 1936, 1939) | Television broadcasting |

| Hans von Ohain, Germany (1939) | Jet engine, jet airplane |

| Eckert & Mauchly (1946) | Electronic computer |

| Bardeen, Brattain, Shockley (1947) | Transistor |

| Ampex (1955) | Video recorder |

| J. Kilby, R. Noyce (1958, 1959) | Integrated electric circuit |

| T. H. Maiman (1960) | Laser |

| Philips (1970) | Videocassette recorder |

| Sony (1980) | Video camcorder |

Source: John R. Boyd, “The Conceptual Spiral,” unpublished briefing, August 1992, pp. 11–12.

Boyd continued by stating that any coherent intellectual or physical system one evolves to represent or deal with large portions of reality will at best represent or deal with that reality incompletely or imperfectly. Moreover, it is impossible to have or create beforehand a supersystem that can forecast or predict the kind of systems that will evolve in the future to represent or deal with that reality more completely or more accurately. Furthermore, such a supersystem can neither forecast nor predict the consequences that flow from those systems that are created later on. Going even farther, one cannot determine or discern the character or nature of such systems (super or otherwise) within themselves.

What Boyd called “the Grand Message” is this: People using theories or subsystems evolved from a variety of information will find it increasingly difficult and ultimately impossible to interact with and comprehend phenomena or systems that move beyond and away from that variety. That is, they will become more and more isolated from that which they are trying to observe or deal with, unless they exploit the new variety to modify their theories and systems or create new ones.

The record reveals that science, engineering, and technology produce change via novelty. To comprehend this process of novelty, one reduces it to patterns and features that make up the pattern. In studying the patterns and features, one can combine and cluster them according to different types of similarities (different advances related to chemistry or electricity, for example). Finding some common features that are shared and connected across disciplines or fields of scientific endeavor helps create a new pattern, new insights. This process of connections is called synthesis. Testing these relationships creates an analytical-synthetic feedback loop for comprehending, shaping, and adapting to the world. Novelty is created through a combination of analysis and synthesis of our environment and our interactions with it.

Now, if our ideas and thoughts matched perfectly with what goes on in the world, and if the systems or processes as designed performed perfectly and matched with whatever one wanted them to do, there would be no basis for evolving or creating new ideas, systems, processes, or materials. There would be no novelty. In other words, it is the presence and production of mismatches that sustain and nourish the enterprise of science, engineering, and technology. Without the intuitive interplay of analyses and syntheses, one has no basic process for generating novelty. There is no basic process for addressing mismatches between one’s mental image or impressions and the reality it is supposed to represent and no basic process for reshaping one’s orientation toward that reality as it undergoes change. Novelty, mismatches, and reorientation are the stuff of life itself.

This leads to amended definitions of science and engineering. Science can be viewed as a self-correcting process of observations, analyses-syntheses, hypothesis and test. Engineering can be viewed as a self-correcting process of observations, analyses-syntheses, design and test. Why? Without the interplay of analyses and syntheses, one cannot develop the hypothesis, design, or follow-on test. This is all very nice, but, asks Boyd, what does it have to do with winning and losing? The very practice of science and engineering and the pursuit of technology produce novelty. Novelty occurs in nature as well. If there are mismatches, there is a chance for adaptation, and this begets more novelty. The entire course of evolution is a confirmation of this reality. One’s own thinking and doing also produces novelty. Indeed, the identification of mismatches (or explanations that are not born out by observations) is responsible for much of the world’s progress. It is how we learn. When a mismatch occurs, one must struggle to square the explanation with the facts. Furthermore, novelty is produced continuously, if somewhat erratically and haphazardly. It is the randomness of it all that makes the process so fascinating.

Now, to thrive and grow in such a world, one must match one’s thinking and one’s actions, hence one’s orientation, with that emerging novelty. Yet any orientation constrained by experiences before that novelty emerges will introduce mismatches that confuse and disorient. However, the analytical-synthetic process permits one to address mismatches so that one can reorient one’s thinking and action with that novelty. Over and over the continuing whirl of reorientation, mismatches, analyses, syntheses, enables one to comprehend, cope with, and shape as well as be shaped by novelty that flows around and over one continuously.

Why does the world continue to unfold in an irregular, disorderly, unpredictable manner, even though some of the best minds try to represent it as being more regular, orderly, and predictable? More pointedly, with so much effort over so long a period by so many people trying to comprehend, shape, and adapt to a world that one depends on for vitality and growth, why does such a world, although richer and more robust, continue to remain uncertain, ever-changing, and unpredictable? The answer is that the various theories, systems, and processes that one employs to make sense of that world contain features that generate mismatches. These keep the world uncertain, ever-changing, and unpredictable. These features include, but are not limited to:

Uncertainty associated with the nonconfinement, undecidability, incompleteness theorems of mathematics and logic

Numerical imprecision associated with using rational and irrational numbers in the calculation and measurement processes

Quantum uncertainty associated with Planck’s constant and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle

Entropy increase associated with the second law of thermodynamics

Irregular or erratic behavior associated with far-from-equilibrium, open, nonlinear processes or systems with feedback

Incomprehensibility associated with inability to screen, filter, or otherwise consider spaghettilike influences from a plethora of ever-changing, erratic, or unknown outside events

Mutations associated with environmental pressure, replication errors, or unknown influences in molecular and evolutionary biology

Ambiguity associated with natural languages as they are used and interact with one another

Novelty generated by the thinking and actions of unique individuals and their many-sided interactions with each other.

The bottom line, given all of this, is simple. If one cannot eliminate these, one must continue the whirl of reorientation, mismatches, analyses, and syntheses to comprehend, shape, and adapt to an unfolding, evolving reality that remains uncertain, ever-changing, and unpredictable. Uncertainty is a basic human condition. It is what we do with it that counts.

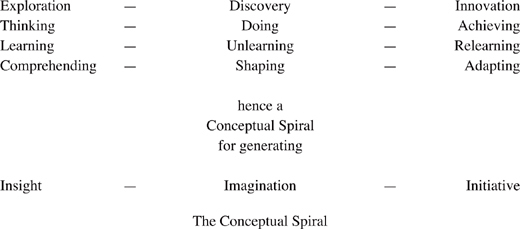

Where does this lead us? We have the basis for a conceptual spiral (see this page). In short, we have a conceptual spiral for generating insight, imagination, initiative. One simply cannot survive without these abilities, says Boyd. The conceptual spiral really is a paradigm for survival and growth. Survival and growth are directly connected with the uncertain, ever-changing, unpredictable world of winning and losing. Therefore, one must exploit this whirling conceptual spiral of orientation, mismatches, analyses-syntheses, so that we can comprehend, cope with, shape, and be shaped by the world and the novelty that arises out of it.

In such a universe and with such a worldview, change is not something to be feared but the very essence of life itself. Life becomes defined as a process of adaptation. Some adaptation is successful. Some is not. The key is the capacity for the combination of analyses and syntheses that enables us to exploit mismatches. This in turn leads to successful adaptation and the repetition of the cycle all over again as more mismatches are encountered that necessitate creative adaptation and change. The explanation can be seen as a scientific and theoretical explication of the OODA loop. In an astonishing progression, Boyd’s inductive method flowed from air-to-air combat to a general theory of change and life itself. The conceptual spiral is the central insight around which “A Discourse on Winning and Losing” itself revolves.

The test of success and the real advantage in the method comes not in reading about it but rather in employing it. Like both muscles and neural networks, Boyd’s Way must be exercised, or it will shrivel and atrophy. Hence, you have a responsibility to play with it, to work out with it, to examine it, to reflect on it, to improve it, to amend it, to grow with it, if you will make full use of the opportunity presented. But a discourse, a conversation, is a two-way street. You are invited to continue this important dialogue with yourself and others about Boyd’s Way and its meaning for you. Remember, the conceptual spiral is insight, imagination, and initiative. Good luck, and happy idea hunting.