Bob Thompson is a hard one to figure out. A man of great energy and ambition, he seemed to have everything going for him, yet he died of a drug overdose at twenty-nine. He was a key figure in the late 1950s/early 1960s Greenwich Village scene, acquainted with everyone who counted, such as LeRoi Jones, Allen Ginsberg, and Ornette Coleman and his band, whom he got to know at the Five Spot jazz club, located across the street from Jones’s apartment. Yet in the last three to four years of his life, when Jones and other young black artists and intellectuals were beginning think in terms of a Black Arts Movement, Thompson turned not to African or to African American sources for his inspiration. Rather, he and his wife, Carol, left for Europe, where he was drawn to painters of the Italian Renaissance (Masaccio, Piero della Franscesca), Nicolas Poussin, the Dutch surrealist before the fact, Hieronymous Bosch, and unclas-sifiables such as El Greco and especially Goya.1 His paintings were increasingly dominated by motifs from classical mythology and the Bible. But he did not paint them in a traditional style or transfer the stories to a contemporary setting; instead, he took paintings by pre-modern European masters and recolored them. The effects were singular, to say the least. A single painting might include figures with white, brown, black, and blue skin. Along with a foreshortening of perspective and elimination of bodily features, especially facial ones, by means of the bold, bright colors, the paintings were flattened toward the surface. Hilton Kramer’s suggestion that Thompson also owed a debt to Henri Matisse is far from implausible.2

Born into a middle-class black family in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1936, Thompson was no untutored prodigy from a remote backwater, though he has been likened to a southern version of Jean-Michel Basquiat. He received a sound, if segregated, education at all-black Louisville Central High and won yearly art scholarships at the University of Louisville, whose art department was au courant with the latest artistic trends. His own training was modernist in orientation, with an emphasis upon the fauvist and expressionist traditions, while his reading ranged from T. S. Eliot and e. e. cummings to Richard Wright and Langston Hughes, Dylan Thomas, and, inevitably, Jack Kerouac. Even before he went to college, he had heard plenty of contemporary jazz and retained a passion for it throughout the rest of his life.3 Yet, as he increasingly spent time in Europe in the first half of the 1960s, his art turned away thematically from the contemporary world. Thompson’s art fed upon a wide range of sources—his personal experience, bold intellectual and cultural exploration, and the Western art tradition of his time and earlier. But it rarely, if ever, made room for historical or social themes and only infrequently did he paint contemporaries. Aside from a portrait of LeRoi Jones and family and one of Allen Ginsberg, what he produced was far from realism of any sort, though figuration was central to it.

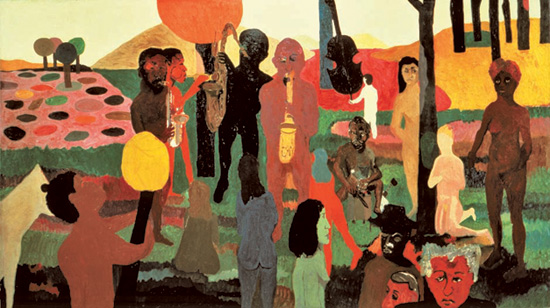

All that said, Thompson’s large (6½´ × 12´) painting Garden of Music (1960) has become iconic in its suggestiveness about the post-war confluence of African American painting and music. Indeed, it is the canvas for which Thompson is best known. In what follows, I explore the world of that painting and the aesthetic issues Thompson evoked in it, especially the overlapping and often mutual fascination between painters and jazz musicians in the post-war world. Then I discuss what Thompson’s turn away from his training and his own experience meant for his art and how we are to judge it in the context of the (African) American 1960s, a decade of important shifts in African American painting and jazz. I conclude by offering some thoughts on the crucial role played by improvisation in both jazz and African American art and contrast the path Thompson took in his last years with the quite different one taken by Romare Bearden, whose career took off in the 1960s.

Though all the figures in Garden of Music are nude, except for the figure in the foreground wearing a black hat, their faces do, unusually in Thompson’s work, have recognizable features (Figure 6.1). Most of the figures are identifiable people placed in an imaginary sylvan setting, “real toads in an imaginary garden,” as poet Marianne Moore once identified the world of poetry. Its status as a painting is signaled by the palette-like field of dappled colors, stylized lollipop-like trees, and a carpeted, many-colored woodland floor. Indeed, the painting might be read to signal Thompson’s commitment to a “colored” or a multi-colored world. The famous sextet gathered together are, from left to right, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry (with a toy trumpet), Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Ed Blackwell (who liked to whittle his own drumsticks), and, standing further back, Charlie Haden balancing his double bass on one finger. A variety of other figures, including three women, one black and two white, look on with various degrees of attention. Though the figures are nude, the erotic dimension of the painting is considerably muted. The sexual organs of the various men are covered by their instruments, by a small tree in Coleman’s case, by the positioning of the body, or they are simply left out. This is by no means always the case in Thompson’s art and suggests that though there is a certain tension in Thompson’s world between sexuality and group life, that tension is largely absent in Garden of Music.

Figure 6.1 Bob Thompson, Garden of Music. 1960. Oil on canvas, 79½ in. × 143 in. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York.

If one had to characterize the painting overall, three qualities come to mind. First, it depicts a kind of racial-cultural pastoral, as Scott Saul notes, “a jam session in the Garden of Eden.”4 Though dominated by black musicians, it depicts an integrated, multi-racial group. It is a mistake to refer to Thompson’s painting at this point as captive of a universalist or integrationist sensibility, if by that we mean the ideal of color blindness, the view that race is irrelevant to understanding individual or group activity. The painting makes no attempt to deny differences in race; it is not a colorless world but one that explicitly includes racial co-existence. Perhaps the best term would be cosmopolitan, which implies the existence side by side of various racial and cultural experiences rather than the blandness suggested by universalism. A second quality of the painting is its gentle humor arising from the unself-conscious interaction of the various figures. Third, though Thompson was nothing if not a well-trained and educated artist, there is something of a faux-visionary, naïve, even primitivist aura to the painting. It is as though in a moment of equipoise Thompson is urging the viewer to imagine a simpler place not in the past or future so much as in a timeless present.

It hardly needs saying that Bob Thompson was not the only post-war painter, particularly in New York, who was fascinated by jazz and tried to relate his own painting, as process and as finished product, to jazz. Nor was this mutual interaction confined to the ranks of African American painters and jazz men after 1945. Willem de Kooning was “mad for music of all kinds—notably jazz and Stravinsky” in the interwar years, while the film Pollock has Jackson Pollock listening to Gene Krupa, and Lee Krasner has testified to Pollock’s immersion in jazz: “He thought it was the only other really creative thing happening in this country.”5 One of Dutch émigré painter Piet Mondrian’s best-known paintings is Broadway Boogie Woogie, an explicit attempt to paint the effects of jazz. Ornette Coleman, one of Thompson’s favorites, felt that “Pollock was ‘in the same state I was in and doing what I was doing,’ ” while the sleeve of his 1961 album Free Jazz famously carried a reproduction of Pollock’s painting White Light. 6

This hardly begins to capture the widespread fascination of jazz musicians and painters for each other. In general, when painters have addressed the phenomenon of jazz, they have approached it with two different things in mind. On the one hand, a painter may represent the performance of a soloist or jazz group and thus seek to capture something about the feel of the process, especially the absorption in their playing as it alternates with their interaction with one another. This is what Garden of Music tries to capture and what so fascinated Thompson. The other, more subtle and difficult task for a painter is to try to capture the essence of jazz through, for instance, the use of color to convey something of the relationship among the parts of a composition. As Robert O’Meally has written, “The challenge has been not merely to offer documentary representations of specific jazz players but to play jazz, as it were, with their cameras, canvases, papers, hammers, chisels and paints.”7 Here Thompson’s use of bright colors and his unnuanced figuration may reflect his effort to capture by means of bold, primary colors certain aspects of jazz as a type of music. Regarding the structuring of space, the crucial thing, Romare Bearden contended, was to pay attention to the “interval” or the space between notes—and sections of a painting. What he learned, he said, from the painter Stuart Davis was to listen to the way someone like Earl Hines used the intervals between notes: “The silences were as expressive as the sounds.… The spaces between the notes.… what does that mean to me as an artist?”8 When one remembers that interval refers to both spatial and temporal gaps, we see that what is at issue is not only the difference between “here” and “there” but also between “past” and “present” and between what something “is” and what it “is” not.9

Beyond that, Bearden, Thompson, and almost everyone else who has commented on a jazz or blues aesthetic has stressed the centrality of improvisation in the immediate post-war period both to jazz playing and to abstract expressionist painting, with Pollock of course always being the prime, not to say clichéd, example of painting as improvisation.10 This was true, in particular, of the so-called action painters, such as Pollock and de Kooning, rather than of the meditative or colorist painters such as Mark Rothko or Barnett Newman among the New York School. But the emphasis upon improvisation, however misapplied and oversimplified, comported well with the idea that post-war jazz and abstract expressionism had thrown overboard received habits, customs, and traditions and set out on their own.

The other issue raised by both jazz and abstract expressionist painting has to do with the contradictory qualities they signified for critics and viewers—the pre-modern, primitive, and the authentic or their opposites: the ultra-modern, the mechanical, and the artificial. Within that the idea of the primitive is highly ambiguous and complex. It can refer both to formal techniques derived from African masks and other objects from Africa and to a cultural ethos that manifests remissive attitudes toward the body, including especially freer sexuality, and is committed to ritualized and animistic modes of thought. The primitive seemed to demand a suspension of the rational and the cognitive, while appealing to the unconscious and the childlike.11 Indeed, the primitive was sometimes, as Patricia Leighton has noted, linked with violence and savagery, but as a way of critiquing the hypocrisy and stultification of Western societies. Yet qualities attributed to black jazz, particularly by its hostile critics such as Theodor Adorno, included the febrile, the mechanistic, and the rootless. It was ultimately what the capitalist world offered as diversion from the rationalized world of mass production. On this view, the world of jazz, especially as dominated by black musicians, was anything but anti-modern, or primitive. Broadway Boogie Woogie celebrates the nervous energy of urban life, and a central characteristic of abstract expressionist painting is the absence of nature. The fascinating thing about Thompson’s paintings in this context is that they manifest connections with both the pre- and the ultra-modern. Some of his paintings contain scenes of sexual violation and violence, while others have a distinctly peaceful and pastoral quality to them. Yet perhaps what is most modernist about his painting is the way it self-consciously alludes to both the primitive and the contemporary, to the pastoral and the urban.

As already mentioned, Thompson frequented the Five Spot in the Village along with other musicians and painters. He became good friends with bassist Charlie Haden, who was also addicted to heroin in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Haden later remembered that Thompson told him that in Garden of Music, he was “painting my favorite musicians, the ones who inspired me.”

Bob felt a closeness to the way we felt about what we were expressing about life. He really painted sound.… A lot of people felt very excited about what we were playing at the Five Spot, but not to the extent that Bob did—in terms of the realization of his work. It struck something in him where he felt “Yeah, I’m not alone.”12

Haden also recalls Thompson pronouncing on painting, painters, and musicians in his loft studio. He pumped Haden with questions of apparent simplicity but of genuine depth and sophistication. “Do you see anything when you are playing?” and “Do you relate improvisation to any visual process?”13 Such questions can be turned around and posed to a painter: “Do you paint sounds?” and “Can you capture time in a way that will do justice to the way it is inflected in music?” Indeed, behind the fascination with the intersection between jazz and modern painting is the assumption that sound is to jazz as color is to painting, thus suggesting that a painter, for instance, can deploy paint to represent the way a musician creates sounds.

Yet a misunderstanding here can easily lead to facile comparisons between the abstract action painting and jazz of the post-war years. Diedra Harris-Kelley has warned against “the easy analogy between playing jazz and making visual art.”14 This is not to say that no analogies are possible or that the questions raised by Thompson and Haden, along with Bearden’s lifelong exploration of these issues, are pointless. But analogies are not identities. The interval between areas of color in a painting or the conceptual space that Bearden’s collages imply between face and mask, painted visage and photographic superimposition has a different ontology than the interval between notes or phrases or movements in music. Time is to music what space is to painting, the medium of its existence. Thus the sequential arrangement of images or events on a canvas is not experienced in the same way as the sequential arrangement of notes.

Ultimately the two realms resist translation into each other. The inability to bridge the gap between them is not a failure of artistic skill or a lack of psychological preparation. It is built into our human and natural reality. This is not to say that artists on both sides of the divide should not explore the ways that representation in space and representation in time may be thought about together. They may even suggest or gesture toward one another; that is, they can become tropes for each other. But a trope is precisely the yoking together of two different things. An exploration of this issue will be fruitful insofar as the gap remains rather than claiming that it can be, or has been, closed.

Thompson went on to create several paintings that displayed a formal similarity to Garden of Music insofar as they depicted group activities in a sylvan setting, including orgies—Bacchanal (1960) and Bacchanal II (1965)—and their interruption from the outside, such as Untitled (1960–61). But Garden of Music was one of only three paintings in Thompson’s body of work that referred explicitly to music or musicians. There was also Ornette (1960–61), a diffuse and scattered, somewhat muddy and unrealized painting,15 while one of his later paintings, Homage to Nina Simone (1965), is a recoloring of Nicolas Poussin’s Bacchanal with a Guitarist (Figure 6.2).16 This late painting well illustrated Thompson’s strategy of appropriation, according to which he took a painting from the pre-modern European tradition and recolored it. As Haden implied, however, it was not Thompson’s choice of subject matter but his way of handling color and structural-spatial arrangements that were jazz influenced. It has been suggested that this process of appropriation was the way Thompson invested the mythological and biblical themes with his own personal mythology and preoccupations. As Thelma Golden has argued, he was not merely a “copyist,” nor was this an “assimilationist tactic,” while Judith Wilson has observed that recoloring was a way of “honoring” but also “irreverently subverting, supplementing, and generally adapting it [the Western tradition] to his own purposes.”17 Thompson was doing what many past painters had done and what jazz musicians were doing in the present—not assimilating into the tradition on its terms, but assimilating the tradition to their own purposes and thereby changing it. The difference in meaning here is the difference between the intransitive (to assimilate into) and the transitive (to assimilate something) meanings of to assimilate.

Figure 6.2 Bob Thompson, Homage to Nina Simone. 1965. Oil on canvas, 48 in. × 72 in. Collection of Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, The John R. Van Derlip Fund. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

One can imagine a nationalist interpretation of Thompson as someone who failed to find his way “back” to the power of blackness because he had been brainwashed by the European art tradition in general and the inter-racial Village scene in particular. From this perspective, it was an “etiquette of ‘racelessness,’ ”18 reinforced by his formalist and intensely personal concerns, that blocked Thompson’s rediscovery of his blackness. Yet we have no evidence that Amiri Baraka (aka LeRoi Jones) ever expressed such misgivings about Thompson,19 though Hilton Kramer charged that in the 1998 Whitney retrospective of Thompson’s work, he was “resegregated, so to speak, to conform to the racial-cultural orthodoxies” of the 1990s.20 On the other hand, a universalist or integrationist portrait of Thompson would depict him as someone who heroically pursued his own vision against a constricting ideology of blackness, while black and white modernists devoted to abstraction would wonder not at his swerve away from racial themes so much as they would question his turn away from abstraction itself and the increasing emphasis upon the representational elements in his painting. To be sure, Thompson had always tended toward what Judith Wilson refers to as a “figurative” or “gestural” expressionism, but his later painting headed away from, rather than further into, that compromise position.21

But why didn’t he move in the direction taken by Bearden? One obvious answer is that he was not Romare Bearden and lacked the older man’s hard-won maturity. Bearden was not born knowing all the answers either and had undergone a crisis of artistic identity in the late 1940s and 1950s; the result was a nervous breakdown in the middle of the latter decade. Bearden’s re-emergence in the first half of the 1960s as a major artist was so successful in part because his appropriation of the modernist-derived collage technique did several things at once. It returned the figure and the face to the canvas without entailing a straightforward social realism and it engaged with African American social and cultural history without simply celebrating the “down-home” southern experience. Moreover, Bearden somehow managed to combine a deep grounding in the Old Masters’ feeling for pictorial structure with a thoroughly modernist sensibility. For instance, Bearden’s Susannah in Harlem and his frequent painterly references to Susannah at the Bath drew upon a standard theme or scene in Western painting. But in contrast with Thompson, Bearden placed this traditional motif in a contemporary setting such as Harlem or a run-down cabin in the South. One has little sense that Bearden was parodying the art tradition with his collage technique; rather, the collage evoked the rich multiplicity of traditions that Bearden tapped into.22

Thompson, however, chose whole paintings, not just motifs, by past masters, recolored them, simplified their detail, and generally retained their original titles. (His retitling of the Nina Simone painting is an exception.) But the effect was to produce a kind of parody of them, while at the same time exploiting the security their place in the Western tradition could give him. To compare and contrast the ways Bearden and Thompson recovered the artistic tradition of the West is to become aware that Bearden’s approach was more successful and productive. Where Bearden’s technique enriched the present with the past, Thompson’s threatened to drain the past of its significance and leave the present without ballast.

Clearly, Thompson’s seven years as a maturing artist (from the late 1950s when he left Louisville to his death in Rome in 1966) were an attempt to shake off modernist abstraction and to discover a new style and vision. What direction should he have taken? How can we tell when an artist becomes himself? Was Thompson’s art historical regression actually an effort to discover a stable tradition to structure and focus his great energies? The Thompsons settled in Paris for a time in 1961 and art critic Barbara Rose remembers running into Thompson in the Louvre, where he went daily to sketch.23 But why Paris and Ibiza? Why Europe, anyway? Why didn’t he return, at least on canvas, to his personal sources and resources? As mentioned, it is difficult to detect in his work any reference to the South or to the experience of African Americans in the South, except perhaps in a painting such as L’Execution (1961), which is ambiguously positioned between religious representations of the crucifixion and secular depictions of a lynching. But, as already mentioned, neither history nor social forces are represented or alluded to directly in his art. If we look at a painting such as An Allegory (1964)—a wagon moving from left to right in the foreground, a large body of water in the background with protruding, cone-shaped mountains scattered throughout, a strange large bird perched on the wagon, along with several differently colored nude figures, one of them forthrightly facing the viewer—it is as hard to tell where it is supposed to be as it is to decide what it is supposed to mean. Is Thompson allegorizing his own artistic career as a journey toward something or somewhere else? As always, Thompson’s figures are not clothed and their faces are often featureless. This suggests that his is a world elsewhere, at times a kind of pre-lapsarian place of pastoral calm and at others a dream landscape filled with swooping creatures and monsters, sex, and violence. To have clothed the figures in his paintings and to have delineated their features would have lent them social-historical specificity and psychological interest. No clothes, no realism; no facial features, no psychological exploration. Perhaps Thompson’s work should be seen as a kind of pastoral expressionism.

But forget the European art tradition or the African American experience in the South. What kept him from developing an African American art of the present? How might Thompson be retrospectively located vis-à-vis the African American 1960s? According to James Hall in Mercy, Mercy Me, a diffuse but authentic spirituality and an internationalization of African American consciousness characterized much black art and music in that decade. In protest at the shallow materialism of the white West, African American artists, says Hall, searched for a spiritual vision that would counteract the “psychology of disintegration” that marked the lives of several African American artists in the post-war period. Hall traces the addiction and then spiritual quest and recovery of John Coltrane and the breakdown, then artistic and personal rediscovery experienced by Bearden.24

It is certainly possible to find a place for Bob Thompson in Hall’s interpretation of black American modernism. His drug addiction was clearly a kind of extended process of breakdown and artificial recovery. More so even than Bearden, Thompson was obsessed with religious-mythological themes and iconography. His “wholeness hunger,” his quest for a saving style and a comprehensive mythology that would make his world cohere, is painfully obvious. In Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t, Scott Saul situates Thompson’s career most centrally in the Village, which served as “the crossroads where black and white artists could explore the vicissitudes of hip life,” a kind of false, secular start on the quest for community, while art historian Richard Powell sees Thompson as possessing an “Orpheus-like sense of fatality, mystery, and spirituality”; he was a “mid-twentieth-century black Hieronymous Bosch.”25 Vulnerable, like Orpheus, to being torn apart by the forces of the historical moment, Thompson stood, notes Saul, “at a moment before the militant racial politics of the mid-sixties” emerged.26

Obviously, the question of where Thompson’s art was heading when he died after a gallbladder operation and then a drug overdose in 1966 must be asked. Again, how did he, and do we, negotiate the move from the world of the cool and the hip to the pastoral tradition in art, from the Five Spot to the Louvre? Would he eventually have made the long trip back? Was it all coming together or was it falling apart? It is hard to see that Thompson’s appropriation by recoloring of the Old Masters was leading anywhere. It leaves too many seams and themes showing; the appropriations remain too obviously that. One answer to the question of how we know when an artist becomes himself is that it is when (in this case) his painting reminds us not of other artists but of himself, and I do not think that had happened—yet.

Thompson’s career as a painter also warns of problems with improvisation as the key to a blues-jazz aesthetic and to African American modernist painting in general.27 Comparisons between Bearden’s collage work and Thompson’s appropriations reveal that Bearden’s worked while Thompson’s finally did not. The improvisatory aesthetic advocated by Bearden and Albert Murray was no guarantee of success. Just as much as Bearden, Thompson created art from other art rather than immediately expressing himself. From a (Harold) Bloomian perspective, one might say that Thompson was never able to overcome the power of his precursors and thus remained in thrall to them, while Bearden was able to make his precursors seem sources for his art rather than masters of it.28 Thompson’s painting, as already indicated, is weighed down by artistic precursors, whose styles he was in the process of trying out and then discarding. His example also reminds us that there is nothing automatically effective about aesthetic experimentation in painting or music. As Murray states, “improvisation” may be “heroic action,” but it may also lead, as he says, to “overextension, over-elaboration, and overrefinement, and as likely as not, attenuation.”29 To posit the centrality of improvisation to creativity in jazz and in mid-century American painting is not enough, since the success or failure of that improvisation must also be assessed.30

Another aesthetic dictum proposed by Murray and Bearden helps illuminate the enigma of Bob Thompson. Part of the debate about “blackness” among African American artists concerned the relative importance of universalism and particularism, something touched on earlier. In the post-1945 period, it was often a matter of either one or the other but not both. But Murray has suggested that, paradoxically, one gets to the universal by exploring the particular: “You deal as accurately as possible with the idiomatic particulars, but you’re trying to get the universal implications.”31 From this perspective, Thompson’s predicament as an artist lay in his inability to discover the particular form and visual landscape that would enable him to develop an artistic vision with universal implications. If Thompson had lived to move back to the United States, there is no way of knowing whether he would have changed his art to conform to the idea of a black aesthetic. Though he remained friendly with Baraka, he did not join him, A. B. Spellman, and Harold Cruse in the Organization of Young Men, a “proto-black cultural nationalist group” in the early 1960s.32 Clearly, Thompson was a man in search of stabilizing forms and ideas. Having fallen out of history, rather like Ellison’s Tod Clifton in Invisible Man, he could have fallen back in as well. But Thompson’s early death means that we will never know whether this would have happened and that is our loss.

To see Bob Thompson’s 1960–61 painting Ornette, please go to the Hearing Eye Web site at www.oup.com/us/thehearingeye.

1. Basic to any understanding of Thompson is Thelma Golden, Bob Thompson (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art with University of California Press, 1998). The book was published to accompany the retrospective show for Thompson at the Whitney Museum, 25 September 1998–3 January 1999. In addition, Gylbert Coker, “Bob Thompson: Honeysuckle Rose to Scrapple from the Apple,” Black American Literature Forum 19.1 (Spring 1985): 18–21, explores Thompson’s intellectual, cultural, and art historical contexts. Besides these, Scott Saul’s Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 77–82, along with Richard J. Powell, Black Art: A Cultural History, revised and expanded ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 111–12, and Sharon F. Patton, African American Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 226–27, discuss Thompson’s cultural and artistic formation and the significance of his work.

2. Hilton Kramer, “60’s Casualty Bob Thompson, Repackaged for the 90’s,” New York Observer, 16 November 1998. Available: http:www.observer.com/ pages’story.asp?ID=44.

3. Judith Wilson, “Garden of Music: The Art and Life of Bob Thompson,” in Golden, Bob Thompson, 31–37. One of Thompson’s fellow students in Louisville was Sam Gilliam, who also went on to considerable acclaim as a painter in Washington, DC.

4. Saul, Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t, 78.

5. Peter Schjedlahl, “The Painting Life,” New Yorker, 20 and 27 December 2004; Lee Krasner, quoted in Mona Hadler, “Jazz and the New York School,” in Representing Jazz, ed. Krin Gabbard (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 248. See also Seeing Jazz: Artists and Writers on Jazz, ed. Elizabeth Goldson, exhibition catalogue (San Francisco: Chronicle Books/Smithsonian Institution, 1997).

6. Quoted in Hadler, “Jazz and the New York School,” 248.

7. Robert G. O’Meally, Introduction [to Part 3], in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 176.

8. Cited in Diedra Harris-Kelley, “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation,” in Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 251.

9. With this emphasis upon the interval, we see an interesting anticipation of one of the central concepts addressed by Derridean deconstruction—differance, a neologism that combines the spatial and temporal non-coincidence of something with itself.

10. Jonathan Jones, “Wild Ones,” Guardian Weekend, 11 December 2004: 61–65, names Marlon Brando, Charlie Parker, and Pollock as the three post-war American artists most committed to an art of improvisation and freedom. Jed Perls, New Art City (New York: Vintage, 2007) includes surprisingly little on the relationship between jazz and painting in post-war New York, except for a brief two pages (201–2). Indeed, despite Perls’s desire to expand the range of discussion of post-1945 American art beyond abstract expressionism and pop art, he has almost nothing on African American artists, except for one page on Romare Bearden’s use of collage (184).

11. For these contrasting images of jazz in modernist culture, see Hadler, “Jazz and the New School,” 252–54, while Patricia Leighton, “The White Peril and L’Art Negre: Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism,” Art Bulletin 72.4 (December 1990): 609–30, is a fascinating analysis of the early aesthetic, moral, and political meanings of primitivism in modern art. The starting point for any discussion of primitivism in the modern visual arts is Robert Goldwater, Primitivism in Modern Painting, enl. sub. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002). Theodor Adorno’s “Perennial Fashion—Jazz,” in Prisms: Cultural Criticism and Society (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981), contains his notorious negative judgment of jazz as mechanical and pseudospontaneous. For a more balanced view, see Ted Gioia’s chapter “Jazz and the Primitivist Myth” in his The Imperfect Art: Reflections on Jazz and Modern Culture (Stanford, CA: Stanford Alumni Association, 1988), 19–49.

12. Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 49.

13. Quoted in ibid., 47.

14. Harris-Kelley, “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation,” 249.

15. If this was an attempt to translate Coleman’s radical ideas about music into painting, it must surely be judged a failure. (The painting can be seen on the Hearing Eye Web site.)

16. There were also drawings of musicians, such as the 1966 sketch of soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy that can be seen on the cover of the latter’s 5 × Monk, 5 × Lacy CD (Silkheart SHCD 144, 1996).

17. Golden, Introduction, in Golden, Bob Thompson, 21; Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 64.

18. Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 57.

19. In this context, it may be worth noting, too, that tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, one of the jazz world’s most outspoken proponents of a black aesthetic, paid tribute to Thompson with an eighteen-minute “eulogy” entitled “A Portrait of Robert Thompson (as a Young Man)” on his 1967 album Mama Too Tight (reissue, Impulse! IMP 12482, 1998).

20. Kramer, “60’s Casualty Bob Thompson,” 2.

21. Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 35.

22. Since Fredric Jameson’s essay “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” (1984), it has become customary to identify pastiche with the post-modern failure to create a sense of the deep past or a past that exists in its own right. Bearden’s use of collage, however, does that very effectively. See chapter 1 of Jameson’s Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991) for the discussion of parody and pastiche.

23. Quoted in Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 60.

24. James C. Hall, Mercy, Mercy Me: African-American Culture and the American Sixties (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 21.

25. Saul, Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t, 76; Powell, Black Art, 112.

26. Saul, Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t, 81.

27. Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison generally locate the source of this idea in the work of André Malraux, but another, more contemporary source would be Harold Bloom’s idea of the “anxiety of influence.” See, for instance, Albert Murray, “Improvisation and the Creative Process,” in O’Meally, Jazz Cadence of American Culture, 111–13.

28. See, for instance, Albert Murray, “The Intent of the Artist,” in The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement (New York: Vintage, 1997), 9–17; Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

29. Murray, “Intent of the Artist,” 15.

30. Clearly there are constraints on improvisation itself. To have a chance of being effective, it must, for instance, be appropriate to the spirit and protocols of the genre at issue, whether it is painting or music. Thanks to Dave Murray for this point.

31. Albert Murray, Conversations with Albert Murray, ed. Roberta S. Maguire (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 59.

32. Wilson, “Garden of Music,” 76.

Golden, Thelma, ed. Bob Thompson. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art with University of California Press, 1998.

Goldson, Elizabeth, ed. Seeing Jazz: Artists and Writers on Jazz. San Francisco: Chronicle Books/Smithsonian Institution, 1997.

Lacy, Steve. 5 × Monk, 5 × Lacy. Silkheart SHCD 144, 1996.

Shepp, Archie. Mama Too Tight. 1967. Reissue, Impulse! 12482, 1998.

Adorno, Theodor. “Perennial Fashion—Jazz.” 1953. In Prisms: Cultural Criticism and Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981. 119–32.

Bloom, Harold. The Anxiety of Influence. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Coker, Gylbert. “Bob Thompson: Honeysuckle Rose to Scrapple from the Apple.” Black American Literature Forum 19.1 (Spring 1985): 18–21.

Gioia, Ted. The Imperfect Art: Reflections on Jazz and Modern Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford Alumni Association, 1988.

Golden, Thelma. Introduction. In Golden, Bob Thompson. Exhibition catalogue. 13–25.

Goldwater, Robert. Primitivism in Modern Painting. Enl. sub. ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002.

Hadler, Mona. “Jazz and the New York School.” In Representing Jazz. Ed. Krin Gabbard. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995. 247–59.

Hall, James. Mercy, Mercy Me: African-American Culture and the American Sixties. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Harris-Kelley, Diedra. “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation.” In O’Meally et al., Uptown Conversation, 249–55.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991.

Jones, Jonathan. “Wild Ones.” Guardian Weekend, 11 December 2004: 61–65.

Kramer, Hilton, “60’s Casualty Bob Thompson, Repackaged for the 90’s.” New York Observer, 16 November 1998. Available: http:www.observer.com/ pages’story.asp?ID=44.

Leighton, Patricia. “The White Peril and L’Art Negre: Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism.” Art Bulletin 72.4 (December 1990): 609–30.

Murray, Albert. The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

———. Conversations with Albert Murray. Ed. Roberta S. Maguire. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997.

———. “Improvisation and the Creative Process.” In O’Meally, Jazz Cadence of American Culture, 111–13.

O’Meally, Robert G. Introduction. [To Part 3.] In O’Meally, Jazz Cadence of American Culture, 175–77.

———, ed. The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

O’Meally, Robert G., Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin, eds. Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Patton, Sharon F. African American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Perls, Jed. New Art City. New York: Vintage, 2007.

Powell, Richard J. Black Art: A Cultural History. Revised and expanded ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Saul, Scott. Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Schjedlahl, Peter. “The Painting Life.” New Yorker, 20 and 27 December 2004. Available: http://www.newyorker.com/archive/.

Wilson, Judith. “Garden of Music: The Art and Life of Bob Thompson.” In Golden, Bob Thompson. Exhibition catalogue. 27–80.